Abstract

Background

Leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B member 4 (LILRB4/ILT3) is an up‐and‐coming molecule that promotes immune evasion. We have previously reported that LILRB4 facilitates myeloid‐derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)‐mediated tumor metastasis in mice. This study aimed to investigate the impact of the LILRB4 expression levels on tumor‐infiltrating cells on the prognosis of non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients.

Methods

We immunohistochemically evaluated the LILRB4 expression levels of completely resected 239 NSCLC specimens. Whether the blocking of LILRB4 on human PBMC‐derived CD33+ MDSCs inhibited the migration ability of lung cancer cells was also examined using transwell migration assay.

Results

The LILRB4 high group, in which patients with a high LILRB4 expression level on tumor‐infiltrating cells, showed a shorter overall survival (OS) (p = 0.013) and relapse‐free survival (RFS) (p = 0.0017) compared to the LILRB4 low group. Multivariate analyses revealed that a high LILRB4 expression was an independent factor for postoperative recurrence, poor OS and RFS. Even in the cohort background aligned by propensity score matching, OS (p = 0.023) and RFS (p = 0.0046) in the LILRB4 high group were shorter than in the LILRB4 low group. Some of the LILRB4 positive cells were positive for MDSC markers, CD33 and CD14. Transwell migration assay demonstrated that blocking LILRB4 significantly inhibited the migration of human lung cancer cells cocultured with CD33+ MDSCs.

Conclusion

Together, signals through LILRB4 on tumor‐infiltrating cells, including MDSCs, play an essential role in promoting tumor evasion and cancer progression, impacting the recurrence and poor prognosis of patients with resected NSCLC.

Keywords: ILT3, immune checkpoint inhibitors, LILRB4, non‐small cell lung carcinoma, translational research

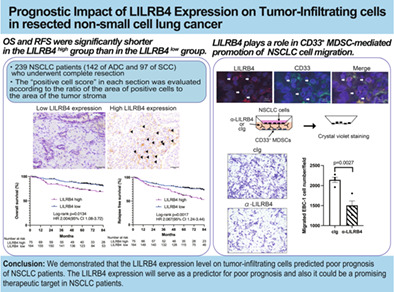

Despite the accumulating knowledge of leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B member 4 (LILRB4) in promoting immune evasion of cancers, the impact of LILRB4 expression in human cancer tissues on prognosis has been poorly investigated. We demonstrated that the LILRB4 expression level on tumor‐infiltrating cells predicted poor prognosis of NSCLC patients. The LILRB4 expression will serve as a predictor for poor prognosis and it could also be a promising therapeutic target in NSCLC patients.

INTRODUCTION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), including antibodies against programmed death‐1 (PD‐1)/programmed death ligand‐1 (PD‐L1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte‐associated protein‐4 (CTLA‐4), emerged in the 2010s, and have revolutionized the treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with a significant improvement in the prognosis of the patients. 1 , 2 , 3 With the expansion of the use of ICIs, however, it became evident that the overall efficacy of the ICIs remains unsatisfactory with a response rate of less than 50%. 4 It is also true that patients receiving ICIs face unique inflammatory toxicities known as immune‐related adverse events with a frequency ranging from 20% to 50%. 5 NSCLC still remains one of the most intractable cancers 6 and developing new therapies for NSCLC, especially exploring novel, more effective and less toxic ICIs, is a current important challenge.

Leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B/immunoglobulin‐like transcript (LILRB/ILT) is a group of inhibitory receptors expressed primarily on immune cells of myeloid and lymphoid lineages. 7 LILR subfamily B4 (LILRB4/ILT3) and gp49B, the murine ortholog for LILRB4, are expressed on a variety of cells, including myeloid cells and a subset of B cells. 8 , 9 Upon ligand engagement, LILRB4 transduces inhibitory signals into cells through immunoreceptor tyrosine‐based inhibition motifs that recruit tyrosine phosphatases SHP‐1, SHP‐2 to inhibit the activation of immune cells. 10 To date, several ligands for LILRB4 have been reported: fibronectin1 (FN1) as a common ligand for LILRB4 and gp49B, 11 , 12 , 13 apolipoprotein E and CD166 for LILRB4, and integrin αvβ3 for gp49B. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17

Recently, an important role of LILRB4 in the immune evasion of several types of cancers has been highlighted. Deng et al. reported that LILRB4 expressed on human acute myeloid leukemia cells promotes tissue invasion of cancer cells and suppresses CD8+ T cells. 14 Sharma et al. showed that blocking LILRB4 prolongs the survival of mice that were subcutaneously transplanted with murine melanoma cells as well as pancreatic cancer cell lines. 18 We have previously demonstrated that knockout of gp49B suppressed the metastasis of intravenously injected Lewis lung cancer cells and B16F10 melanoma cells in a murine model. 19 We also examined the cytokine gene expression in splenic myeloid‐derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) from tumor‐bearing mice, and found that the expression of tumor‐promoting TGF‐β, IL‐10, and ARG‐1 was downregulated, while the expression of TNF‐α and iNOS was upregulated in gp49B−/− mice compared with wild‐type mice. This suggests that signaling through LILRB4 on MDSCs plays a role in the polarization of the MDSCs to exhibit protumor phenotypes. Despite the accumulating knowledge concerning the ability of LILRB4 to promote immune evasion of cancers, little is known about the expression of LILRB4 on tumor‐infiltrating cells in human cancer specimens and its role in tumor progression and patient survival.

This study aimed to investigate the impact of LILRB4 expression on tumor‐infiltrating cells, including MDSCs, on the prognosis of NSCLC patients. We found that the level of LILRB4 expression on tumor‐infiltrating cells was a predictor for postoperative recurrence and survival in NSCLC patients who underwent complete resection. Our in vitro study also demonstrated that the ability of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)‐derived CD33+ MDSCs to promote the migration of human lung cancer cells was inhibited by the blocking of LILRB4.

METHODS

Patients

Surgical tissue specimens were collected from 239 consecutive NSCLC patients who underwent complete resection at Tohoku University Hospital. Our cohort included 142 cases of adenocarcinoma (ADC) and 97 cases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that underwent surgery from 2011 to 2013, and 2011 to 2017, respectively. The Ethics Committee Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine approved this retrospective study (no. 2017‐1‐359) and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Pathological diagnosis, adjuvant chemotherapy, and postoperative surveillance

All the specimens were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. The most representative sections with the largest diameters for each tumor were selected for analysis. Pathological diagnosis was established by board‐certified pathologists according to the World Health Organization classification. Pathological stage was determined according to the TNM classification of malignant tumors of the Union for International Cancer Control (eighth edition). Adjuvant chemotherapy was given when indicated following the clinical guidelines of the Japan Lung Cancer Society. All patients were followed up for at least 5 years and postoperative recurrence was evaluated by clinical examination, computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography/CT, or magnetic resonance imaging; histological confirmation of the recurrence was not mandatory. The date of diagnosis by imaging or histological confirmation of recurrence was defined as the date of recurrence.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections (4‐μm thick) were dewaxed with xylene and ethanol. The characteristics of the antibodies and antigen retrieval methods used in this study are described in Table S1a. A Histofine kit (Nichirei Biosciences Inc.) using the streptavidin‐biotin amplification method was used for LILRB4, FN1 and CD14, and the EnVision kit (Dako) was used for CD33. The antigen–antibody complex was visualized using the 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (1 mM DAB, 50 mM Tris–HCL buffer, pH 7.6, and 0.006% H2O2) and counterstained with hematoxylin. The sections were evaluated using an Olympus microscope BX53 (Olympus).

Definition of “positive cell score” for LILRB4, CD33 and CD14 expression on tumor‐infiltrating cells

We focused on the intensity of LILRB4, CD33 and CD14 positive cells infiltrating into the tumor stroma, and the “positive cell score” in each section was evaluated according to the ratio of the area of positive cells to the area of the tumor stroma based on a previous report, 20 and graded as follows with a modified grading system: 21 0 = <1%, 1 = 1–5%; 2 = 6%–10% 3 = 11%–20%; 4 = 21%–50%, 5 = >50%. The staining levels of FN1 in the tumor stroma were semi‐quantified using H‐score analysis as previously reported. 22 All samples were reviewed by two experienced investigators, including at least one pathologist, under double‐blind settings.

Double immunofluorescent staining

Paraffin sections (4‐μm thick) were dewaxed with xylene and ethanol. Antigen retrieval methods are described in Table S1b. Sections were washed with 1× phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with blocking solution. These sections were incubated overnight in a moist chamber at 4°C with primary antibodies. The sections were subsequently incubated with fluorescence‐labeled secondary antibodies as described in Table S1c. The slides were stained with 4', 6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) for 30 min and mounted. Confocal laser microscopy (Olympus) was used to detect positive images.

Analysis of publicly available genomic data

Genomic data obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)‐lung adenosarcoma (LUAD) and TCGA‐lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) database were utilized in the UCSC Xena Browser (http://xena.ucsc.edu/).

Cell lines

Human lung ADC cell lines A549 (RRID: CVCL_0023) and PC‐9 (RRID: CVCL_B260) were obtained from the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research of Tohoku University (Sendai, Japan). Human lung SCC cell lines EBC‐1 (RRID: CVCL_2891) and LK‐2 (RRID: CVCL_1377) were obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (Osaka, Japan). A549, PC‐9 and LK‐2 cells were maintained in RPMI‐1640 medium (Sigma‐Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biowest) and 1× antibiotic‐antimycotic (ThermoFisher Scientific). EBC‐1 was maintained in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM, #M2279, Sigma‐Aldrich) supplemented with 2 mM L‐glutamine (Wako Pure Chemicals), 10% FBS (Biowest) and 1× antibiotic‐antimycotic (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 95% air atmosphere containing 5% CO2 with a change of medium every 2 or 3 days. All cell lines had been authenticated using short tandem repeat profiling within the last 3 years, and all experiments were performed with mycoplasma‐free cells.

CD33+ MDSC isolation

Human PBMCs were purchased from Cellular Technology Ltd (CTL). For CD33+ PBMC isolation, cells were labeled with biotinylated anti‐CD33 antibody (Biolegend), incubated with streptavidin‐coated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and separated on an MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec). CD33+ PBMCs were differentiated into MDSCs in the lower chambers of a 24‐well transwell plate (Corning) in complete RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with IL‐6 (10 ng/mL, Sigma‐Aldrich) and GM‐CSF (10 ng/mL, PeproTech) for 7 days as previously described. 23

Migration assay

To generate tumor‐associated MDSCs, 5 × 104 of CD33+ PBMC‐derived MDSCs were seeded in a 24‐well culture plate and cocultured with cancer cells placed in a 24‐well 0.4 μm‐pore transwell insert. After 2 days, tumor‐associated CD33+ PBMC‐derived MDSCs were then incubated with 1 × 104 of 24 h serum‐starved cancer cells placed in a 24‐well 8 μm‐pore transwell insert (Corning) for 36 h. Nonmigratory cancer cells inside the transwell insert were removed using a cotton swab, while migrated cells on the outside surface of the transwell insert were fixed with 100% methanol for 10 min at 4°C and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min at room temperature. Finally, the number of migrated cells was observed and counted using a BZ‐9000 fluorescence microscope (magnification x20, Keyence). Five random fields per well were counted using ImageJ software. 24

Statistical analysis

A student's t‐test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the mean or median difference between the two groups depending on the nature of the data. Spearman correlation analysis was used to measure the relationship between the two variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify risk factors for postoperative recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval from the surgery date to the date of death or last follow‐up. Relapse‐free survival (RFS) was defined as the interval from the surgery date to the date of first recurrence, death, or last follow‐up. The OS and RFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. When there was a significant difference in survival between groups, prognostic factors were examined using a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. Because of the small number of cases and events in this study, we employed a limited number of variables, age, gender, pathological stage, histology, and LILRB4 expression level for the multivariate analyses to see the significance of LILRB4 expression level on recurrence and survival. In order to account for potential confounders and address the imbalance between the two groups, a propensity score matching (PSM) technique was employed. The nearest‐neighbor method was used with a 1:1 ratio to match patients in the LILRB4 high group with those in the LILRB4 low group. The propensity score was calculated using a multivariable logistic regression model, incorporating 10 variables: age, gender, smoking status, histology, TNM stage, SUV max value on positron emission tomography/CT, lymph node metastasis, as well as pathological factors including vascular invasion, lymphatic invasion, and pleural invasion. The 1:1 PSM resulted in 60 matched pairs within the LILRB4 high group and LILRB4 low group, ensuring no differences across the 10 covariates. Lastly, the standardized differences in confounding factors were estimated before and after PSM. A p‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism software version 9.0 (GraphPad Software), and PSM, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were performed using JMP Pro 16 software (version 16, SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Association of LILRB4 positive cell scores with clinicopathological characteristics of NSCLC patients

We evaluated the LILRB4 positive cell scores in 239 patients (142 of ADC and 97 of SCC). Representative photographs of immunohistochemical staining for LILRB4 are shown in Figure 1a. The median LILRB4 positive cell score in all specimens was 2 (interquartile range [IQR] 2–4) and thus, the cases with LILRB4 positive cell scores of 3 or higher were defined as the LILRB4 high group and the others as the LILRB4 low group. Seventy‐five cases (31.4%) belonged to the LILRB4 high group, including 26 ADC and 49 SCC, and 164 cases (68.6%) were in the LILRB4 low group, with 116 of ADC and 48 of SCC. Clinicopathological characteristics in both groups are shown in Table 1. Before PSM, the LILRB4 high group included significantly more men (p = 0.029), more smokers (p < 0.001), and more SCC patients (p < 0.001) than the LILRB4 low group. The LILRB4 high group also showed a higher SUV max value on positron emission tomography/CT (p = 0.003) and a higher incidence of pathologically evaluated vascular invasion (p = 0.048) compared with the LILRB4 low group.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Representative photographs of immunohistochemical staining for LILRB4 on tumor‐infiltrating cells of non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissue (bar: 50 μm). Left: low expression (positive cell score of 0, cytoplasmic), Right: high expression (positive cell score of 4, cytoplasmic). (b, c) Overall survival (b) and relapse‐free survival (c) of completely resected NSCLC patients according to LILRB4 expression levels on tumor‐infiltrating cells. LILRB4, leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B4.

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the NSCLC patients according to LILRB4 positive cell score before propensity score matching.

| Variables | Unmatched comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LILRB4 high | LILRB4 low | p‐value | SMD | |

| Number of patients (n) | 75 (31.4%) | 164 (68.6%) | ||

| Age (years; median [IQR]) | 70 (65–76) | 70.5 (64–75) | 0.514 | 0.139 |

| Sex (female) | 19 (25.3%) | 66 (40.2%) | 0.029* | 0.322 |

| Smoking (ex or current) | 65 (86.7%) | 106 (64.6%) | <0.001* | 0.531 |

| Histology | ||||

| ADC | 26 (34.7%) | 116 (70.7%) | ||

| SCC | 49 (65.3%) | 48 (29.3%) | <0.0001* | 0.775 |

| pTNM | ||||

| Stage I | 52 (69.3%) | 116 (70.7%) | ||

| Stage II | 10 (13.3%) | 31 (18.9%) | ||

| Stage III | 12 (16.0%) | 16 (9.8%) | ||

| Stage IV | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.373 | 0.121 |

| Suv max (median [IQR]) | 6.8 (3.4–9.6) | 4.3 (1.8–7.6) | 0.003* , a | 0.410 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| (+) | 17 (22.7%) | 27 (16.5%) | ||

| (−) | 58 (77.3%) | 137 (83.5%) | 0.282 | 0.316 |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| (+) | 39 (52.0%) | 62 (37.8%) | ||

| (−) | 36 (48.0%) | 102 (62.2%) | 0.048* | 0.288 |

| Lymphatic invasion | ||||

| (+) | 21 (28.0%) | 52 (31.7%) | ||

| (−) | 54 (72.0%) | 112 (68.3%) | 0.650 | 0.081 |

| Pleural invasion | ||||

| (+) | 23 (30.7%) | 43 (26.2%) | ||

| (−) | 52 (69.3%) | 121 (73.8%) | 0.533 | 0.430 |

Abbreviations: ADC, adenocarcinoma; IQR, interquartile range; LILRB4, leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B4; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SMD, standard mean differences.

Missing the SUV max in seven patients (n = 232).

P < 0.05.

Impact of LILRB4 positive cell scores on recurrence, OS and RFS in patients with NSCLC

There were 26 (34.7%) and 32 (19.5%) recurrences in patients of the LILRB4 high and LILRB4 low groups, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis with covariates of age, sex, stage (I vs. II–IV), histological type and LILRB4 positive cell scores (high vs. low) was performed, which identified a high LILRB4 positive cell score as an independent factor for postoperative recurrence (p < 0.001, OR: 3.016, 95% CI: 1.55–5.96) (Table 2a).

TABLE 2.

Multivariate analysis to identify predictors for postoperative recurrence (a), overall survival and relapse‐free survival (b) of non‐small cell lung cancer patients.

| (a) Recurrence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p‐value |

| Age (≥70) | 1.158 | 0.63–2.13 | 0.635 |

| Sex (male) | 2.887 | 1.39–6.25 | 0.004* |

| pStage I vs. II–IV | 4.088 | 2.17–7.86 | <0.001* |

| SCC | 0.556 | 0.27–1.13 | 0.104 |

| LILRB4 high | 3.016 | 1.55–5.96 | 0.001* |

| (b) Overall survival and relapse‐free survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Multivariable | |||||

| OS | RFS | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | p‐value | HR | 95% CI | p‐value | |

| Age (≥70) | 1.547 | 0.86–2.77 | 0.138 | 1.416 | 0.88–2.27 | 0.149 |

| Sex (male) | 6.025 | 2.30–15.80 | <0.001* | 2.481 | 1.36–4.53 | 0.002* |

| pStage I vs. II–IV | 3.267 | 1.83–5.83 | <0.001* | 3.652 | 2.23–5.97 | <0.001* |

| SCC | 1.544 | 0.81–2.93 | 0.185 | 1.902 | 1.08–3.34 | 0.026* |

| LILRB4 high | 1.900 | 1.03–3.51 | 0.042* | 2.179 | 1.32–3.60 | 0.003* |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LILRB4, leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B4; OR, odds ratio; OS, overall survival; pStage, pathological stage; RFS, relapse‐free survival; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

P < 0.05.

Overall survival and RFS were compared between the two groups. The median length of follow‐up for censored cases was 79.7 months (range: 4.4–115.5 months) in the LILRB4 high group and 79.3 months (range: 1.0–119.6 months) in the LILRB4 low group. Of note, OS was significantly shorter in the LILRB4 high group than in the LILRB4 low group (p = 0.013, 5‐year OS rate: 73.2% vs. 85.7%, Figure 1b). Relapse‐free survival was also significantly shorter in the LILRB4 high group than in the LILRB4 low group (p = 0.0017, 5‐year RFS rate: 61.7% vs. 78.5%, Figure 1c). Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed to identify independent prognostic factors for OS and RFS with covariates of age, sex, pathological stage (I vs. II–IV), histological type and LILRB4 positive cell scores (high vs. low). The result showed that high LILRB4 positive cell scores were an independent factor for a poor prognosis for OS (p = 0.042, HR: 1.900, 95% CI: 1.03–3.51) and RFS (p = 0.003, HR: 2.179, 95% CI: 1.32–3.60) (Table 2b).

The relationship between the LILRB4 positive cell score, postoperative recurrence, OS and RFS was further examined in subgroups stratified by histological type and stages. As the number of stage II–IV patients in this cohort was small, the subgroup analysis was conducted with two subgroups, stage I patients with ADC and those with SCC. In stage I ADC patients, there were six (31.6%) and 11 (12.2%) recurrences in the LILRB4 high and LILRB4 low groups, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis with covariates of age, sex, pathological stage (IA vs. IB) and LILRB4 positive cell scores (high vs. low) demonstrated that the high LILRB4 positive cell score was an independent predictor for postoperative recurrence (p = 0.031, OR: 3.795, 95% CI: 1.13–12.77) (Table S2a). In the stage I SCC patients, there were 17 (51.5%) and three (11.5%) recurrences in the LILRB4 high and LILRB4 low groups, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis also identified a high LILRB4 positive cell score as an independent predictor for postoperative recurrence in this subgroup (p = 0.006, OR: 7.451, 95% CI: 1.79–30.93) (Table S2b).

In stage I ADC patients, OS was not significantly difference between the two groups (p = 0.563, 5‐year OS: 78.9% vs. 88.9%). Relapse‐free survival was significantly shorter in the LILRB4 high group compared with LILRB4 low group (p = 0.038, 5‐year RFS: 63.2% vs. 86.7%). (Figure S1a,b). In patients with stage I SCC, the LILRB4 high group showed significantly shorter OS and RFS compared with the LILRB4 low group (OS: p = 0.007, 5‐year OS: 48.5% vs. 76.9%, RFS: p = 0.005, 5‐year RFS: 48.5% vs. 73.1%) (Figure S1c,d). Cox proportional hazards analysis with covariates of age, sex, pathological stage (IA vs. IB) and LILRB4 positive cell scores (high vs. low) showed that LILRB4 positive cell score was an independent factor for poor RFS in stage I ADC (p = 0.031, HR: 3.06, 95% CI: 1.11–8.48) (Table S3a), and OS (p = 0.021, HR: 5.850, 95% CI: 1.30–26.30) and RFS (p = 0.017, HR: 4.568, 95% CI: 1.31–15.88) in stage I SCC patients (Table S3b,c).

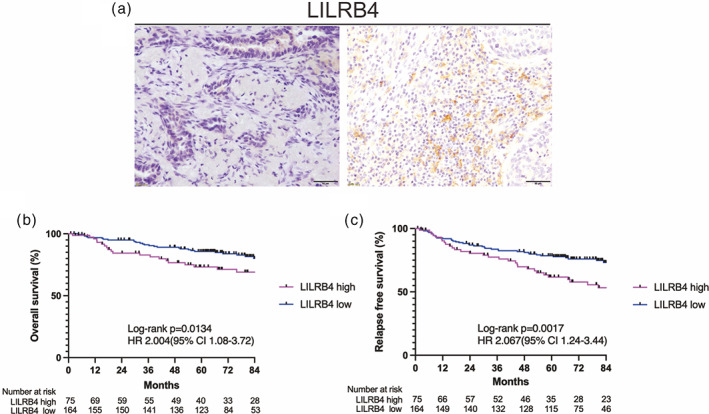

Impact of LILRB4 positive cell scores on OS and RFS after PSM

For a survival comparison, we adopted PSM which identified 60 patients in each group. After PSM, the variables (gender, smoking status, histology, SUV max value on positron emission tomography/CT, and vascular invasion) were between the two groups as described in Table 3. After matching, OS was significantly shorter in the LILRB4 high group than in the LILRB4 low group (p = 0.023, 5‐year OS rate: 76.6% vs. 87.7%, Figure 2a). Relapse‐free survival was also significantly shorter in the LILRB4 high group than in the LILRB4 low group (p = 0.0046, 5‐year RFS rate: 64.2% vs. 81.1%, Figure 2b).

TABLE 3.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the NSCLC patients according to LILRB4 positive cell score, after propensity score matching.

| Variables | Matched comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LILRB4 high | LILRB4 low | p‐value | SMD | |

| Number of patients (n) | 60 (50.0%) | 60 (50.0%) | ||

| Age (years; median [IQR]) | 71 (65.3–76.8) | 71 (65.3–74) | 0.701 | 0.097 |

| Sex (female) | 17 (28.3%) | 19 (31.7%) | 0.690 | 0.073 |

| Smoking (ex or current) | 50 (83.3%) | 48 (80.0%) | 0.637 | 0.086 |

| Histology | ||||

| ADC | 24 (40.0%) | 24 (40.0%) | ||

| SCC | 36 (60.0%) | 36 (60.0%) | 1.000 | 0 |

| pTNM | ||||

| Stage I | 44 (73.3%) | 42 (70.0%) | ||

| Stage II | 9 (15.0%) | 11 (18.3%) | ||

| Stage III | 7 (11.7%) | 7 (11.7%) | ||

| Stage IV | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.884 | 0.048 |

| Suv max (median [IQR]) | 5.25 (2.75–9.16) | 6.5 (3.08–11.23) | 0.846 | 0.059 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| (+) | 11 (18.3%) | 12 (20.0%) | ||

| (−) | 49 (81.7%) | 48 (80.0%) | >0.999 | 0.064 |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| (+) | 30 (50.0%) | 30 (50.0%) | ||

| (−) | 30 (50.0%) | 30 (50.0%) | 1.000 | 0 |

| Lymphatic invasion | ||||

| (+) | 16 (26.7%) | 20 (33.3%) | ||

| (−) | 44 (73.3%) | 40 (66.7%) | 0.425 | 0.146 |

| Pleural invasion | ||||

| (+) | 17 (28.3%) | 13 (21.7%) | ||

| (−) | 43 (71.7%) | 47 (78.3%) | 0.528 | 0.226 |

Abbreviations: ADC, adenocarcinoma; IQR, interquartile range; LILRB4, leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B4; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SMD, standard mean differences.

FIGURE 2.

(a, b) Overall survival (a) and relapse‐free survival (b) of completely resected non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients according to LILRB4 expression levels on tumor‐infiltrating cells in the unmatched cohort. LILRB4, leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B4.

Relationship between LILRB4 expression and MDSC markers

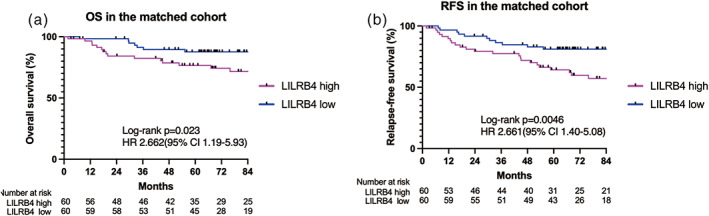

To determine whether LILRB4 positive cells included MDSCs, double immunofluorescent staining was performed using antibodies against LILRB4, CD33, and CD14. CD33 and CD14 are representative markers to identify MDSCs with a modest specificity in which CD33 is also expressed on monocytes and myeloid cells, 25 , 26 and CD14 on monocytes and macrophages. 27 , 28 , 29 The results of double immunofluorescent staining showed that LILRB4 was expressed on CD33‐positive and CD14‐positive cells (Figure 3a,b). We also evaluated the correlation between the positive cell scores for LILRB4 and those for CD33 and CD14. Representative photographs of immunohistochemical staining for CD33 and CD14 are shown in Figure 3c,d. LILRB4 positive cell score showed a statistically significant positive correlation with both CD33 and CD14 positive cell scores (Spearman's rank method, rs = 0.354, p < 0.001 for CD33, and rs = 0.596, p < 0.001 for CD14) (Figure 3e,f), suggesting that at least some of the LILRB4 positive cells infiltrating into the tumor stroma of NSCLC were MDSCs. An analysis of mRNA expression data from the TCGA database via the Xena platform 30 also revealed a strong correlation between LILRB4, CD33, and CD14 mRNA expression in ADC and SCC samples (r = 0.6763, p < 0.0001 for CD33, and r = 0.7980, p < 0.0001 for CD14) (Figure 3g,h).

FIGURE 3.

(a, b) Double immunofluorescence staining of LILRB4 and CD33 (LILRB4, red, cytoplasmic; CD33, green, cytoplasmic) (a), and CD14 (LILRB4, red, cytoplasmic; CD14, green, cytoplasmic) (b) on tumor‐infiltrating cells of non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissue. Double‐positive cells are shown in yellow (white arrow). Bar: 10 μm. (c) Representative photographs of immunohistochemical staining for CD33 of NSCLC tissue. Left: low expression (positive cell score of 0, cytoplasmic); Right: high expression (positive cell score of 2, cytoplasmic) of CD33 in tumor‐infiltrating cells (bar: 50 μm). (d) Representative photographs of immunohistochemical staining for CD14 of NSCLC tissue. Left: low expression (positive cell score of 0, cytoplasmic); Right: high expression (positive cell score of 4, cytoplasmic) of CD14 in tumor‐infiltrating cells (bar: 50 μm). (e, f) Correlation between the positive cell scores for LILRB4 and those for CD33 (e) and CD14 (f). LILRB4 positive cell score showed a statistically significant positive correlation with both CD33 and CD14 positive cell scores (Spearman's rank method, rs = 0.354, p < 0.001 for CD33, and rs = 0.596, p < 0.001 for CD14). (g, h) mRNA expression from the TCGA database via the Xena platform. 29 LILRB4 mRNA expression is positively correlated with CD33 and CD14 molecules, respectively, in the TCGA data set. LILRB4, leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B4.

FN1 expression in NSCLC

We reported FN1 as a ligand for LILRB4 in 2021, 11 and the FN1 expression levels in the tumor stroma were evaluated using H‐score based on the staining intensity and area. 22 Representative photographs of immunohistochemical staining for FN1 are shown in Figures S2a,b. FN1 expression levels were generally high, with an H‐score > 60 in all NSCLC specimens. The median expression score of FN1 in LILRB4 high group was 150, and 140 in LILRB4 low group, showing no relationship between the FN1 expression levels and the LILRB4 positive cell scores (p = 0.169, Figure S2c). This result indicated that LILRB4‐FN1 interaction in the NSCLC stroma is mainly regulated by the LILRB4 expression levels on tumor‐infiltrating cells.

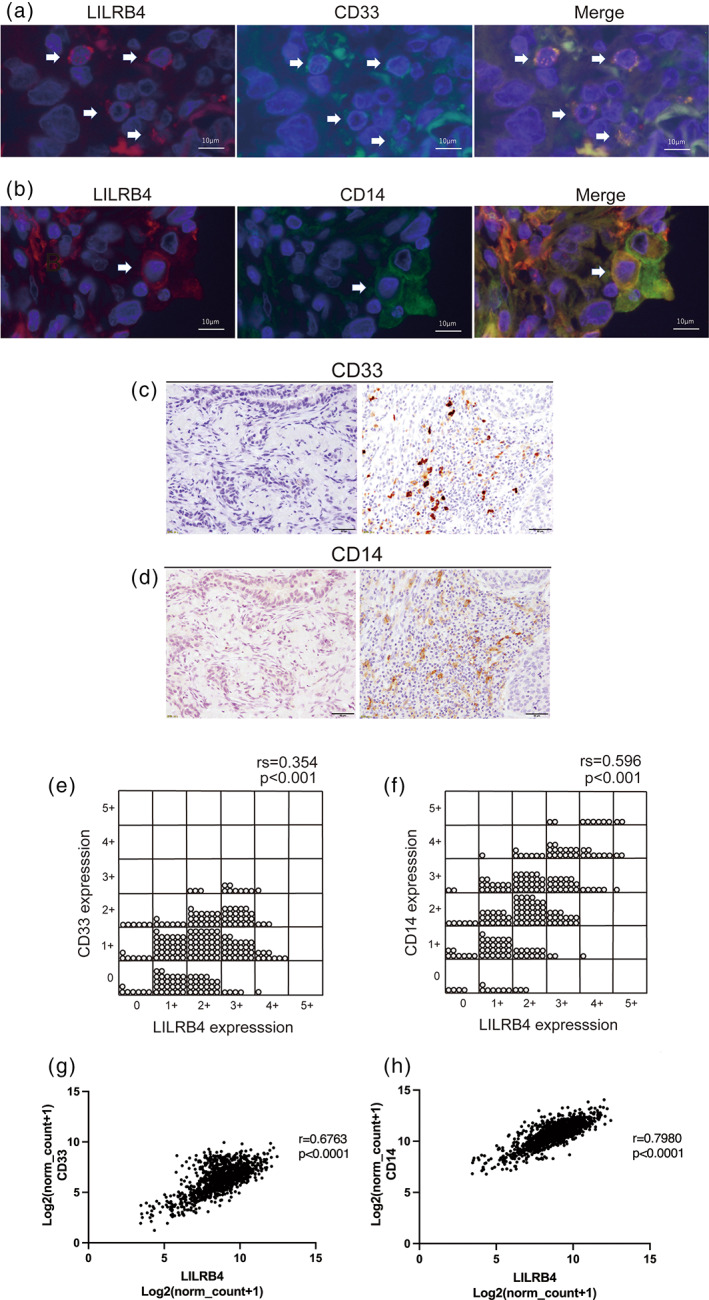

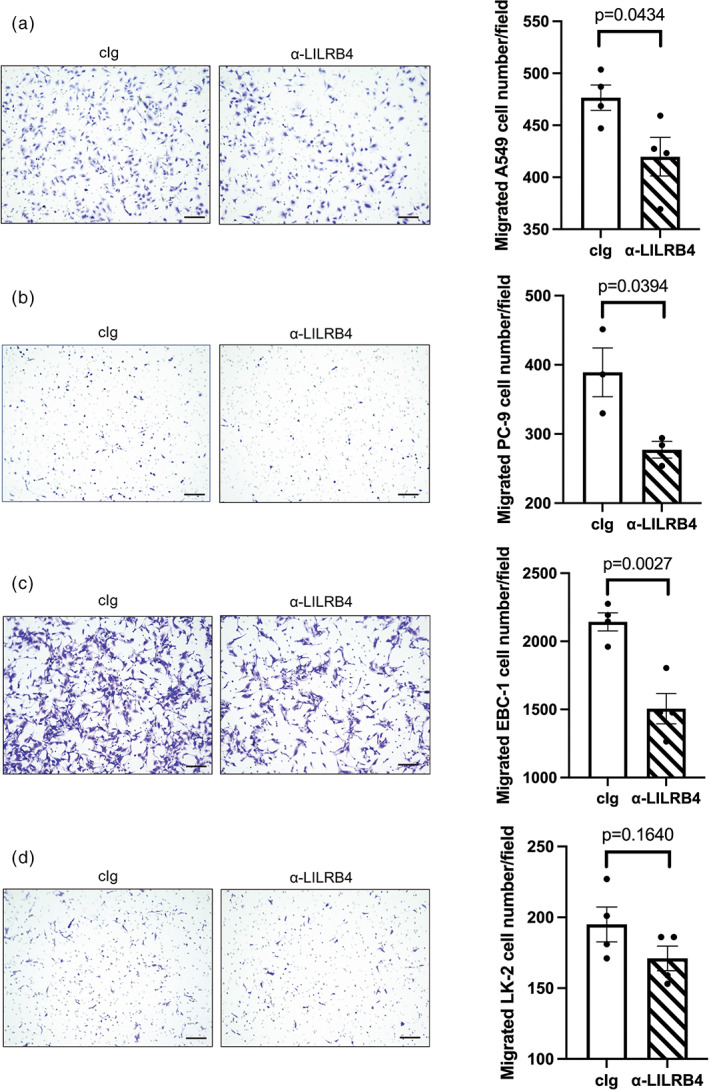

Effect of LILRB4 blocking on CD33+ MDSC‐mediated lung cancer cell migration

Previously, we demonstrated that gp49B, the murine homolog of LILRB4, regulates the MDSC‐mediated promotion of murine lung cancer cell migration. 19 However, the role of LILRB4 signaling on MDSC‐mediated migration of human lung cancer cell lines is not known. To investigate whether the blocking of LILRB4 on CD33+ MDSCs inhibits the migration of human lung cancer cells, the CD33+ monocytes from PBMCs were isolated for in vitro MDSC differentiation. The expression of LILRB4 on PBMC‐derived CD33+ MDSCs was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis (Figure S3a). In transwell experiments, two ADC cell lines (A549 and PC‐9) and two SCC cell lines (EBC‐1 and LK‐2) that have negative expression of LILRB4 (Figure S3b–e) were seeded in transwell inserts and cocultured with PBMC‐derived CD33+ MDSCs pretreated with or without the LILRB4 blocking antibody. The transwell migration assay revealed that the number of migrated A549, PC‐9, and EBC‐1 cells cocultured with CD33+ MDSCs was significantly reduced by the anti‐LILRB4 antibody treatment compared with the control Ig treatment (Figure 4a–c). The number of migrated LK‐2 cells cocultured with LILRB4‐blocked CD33+ MDSCs was reduced compared to that cocultured with control CD33+ MDSCs but with no statistically significant difference (Figure 4d). The above results suggested that LILRB4 plays a role in CD33+ MDSC‐mediated promotion of ADC and SCC cell migration.

FIGURE 4.

The suppression effect of LILRB4 blockade on CD33+ myeloid‐derived suppressor cell (MDSC)‐mediated migration ability of lung cancer cells. The migration ability of lung cancer cells, including (a) A549, (b) PC‐9, (c) EBC‐1, and (d) LK‐2 cells, was determined by transwell migration assay. Lung cancer cells were seeded in transwell inserts and cocultured with CD33+ MDSC treated control Ig or LILRB4 blocking antibody in a 24‐well culture plate for 36 h. The number of migrated cells was calculated using ImageJ (bar: 100 μm). The graphs show four independent repeats and the statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two‐tailed t‐test (error bars; SEM). cIg, control Ig G; LILRB4, leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor subfamily B4.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to evaluate the expression of LILRB4 on tumor‐infiltrating cells of human NSCLC specimens. Most notably, we demonstrated that the LILRB4 expression level on tumor‐infiltrating cells in the stroma, as defined by the LILRB4 positive cell score in this study, was a predictor for postoperative recurrence and poor prognosis in NSCLC patients who underwent complete resection. A part of LILRB4 positive tumor‐infiltrating cells was shown positive for CD33/14. Our in vitro transwell migration assay also revealed that blocking LILRB4 significantly inhibited the migration of human lung cancer cells cocultured with human CD33+ MDSCs, as we have previously shown in the settings of murine MDSCs and cancer cells. 19 These results suggest that signals through LILRB4 on tumor‐infiltrating cells, including MDSCs, play an important role in promoting tumor evasion and cancer progression, influencing the recurrence and poor prognosis of patients with surgically resected NSCLC.

Survival analysis of 239 patients who underwent complete resection for NSCLC showed that OS and RFS were worse in the LILRB4 high group compared with the LILRB4 low group. Multivariate analyses further revealed that a high LILRB4 positive cell score was an independent factor for postoperative recurrence and a prognostic factor for poor OS and RFS. Subgroup analyses restricted to stage I ADC and stage I SCC also showed a similar result. High LILRB4 expression predicts recurrence and poor RFS in stage I ADC, and recurrence, poor OS and RFS in stage I SCC. Our PSM analysis further confirmed lower OS and RFS in the LILRB4 high group than in the LILRB4 low group. Goeje et al. reported that high LILRB4 expression on granulocytic MDSCs in peripheral blood was a poor prognostic factor in NSCLC patients. 31 Li et al. evaluated the LILRB4 expression on cancer cells immunohistochemically in surgically resected samples from 113 NSCLC cases. 32 They showed that a high immunoreactive score of LILRB4 predicts advanced disease and poor OS. The results of these studies are consistent with ours in that the prognosis of NSCLC patients was affected by LILRB4 expression, although the LILRB4 positive cells examined were all different among the studies. Our immunohistochemical study also demonstrated that the intensity of LILRB4 expression on tumor‐infiltrating cells in the stroma was higher in SCC than that in ADC. We also found that the expression of FN1, a ligand for LILRB4, in tumor stroma was generally high in all NSCLC specimens, suggesting that LILRB4‐FN1 interaction in the NSCLC stroma may be mainly regulated by the LILRB4 expression levels on tumor‐infiltrating cells.

The present study also revealed that at least a part of LILRB4 positive tumor‐infiltrating cells in the stroma of NSCLC was MDSCs, as shown by the results of double staining of LILRB4 and CD33/CD14, and there was a significantly positive correlation between the positive cell scores for LILRB4 and CD33/CD14. Taken together with the in vitro transwell migration assay, which showed that the human lung cancer cell migration was inhibited by blocking LILRB4 on MDSCs, a worse prognosis of LILRB4 high NSCLC patients may be associated with the immune evasion of cancer cells mediated by LILRB4 on MDSCs, which are known as one of the major cell types that promote cancer progression in the tumor microenvironment. 33 , 34 , 35 Usually, immature myeloid cells in the bone marrow quickly differentiate into mature granulocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. However, in the cancer‐bearing state, there is a heterogeneous increase in immature myeloid cells, including MDSCs, that suppress cancer immunity. 36 Interestingly, a high level of circulating CD33+ MDSCs is reported to predict a poor prognosis in patients with stage IV melanoma treated with anti‐CTLA‐4 therapy. 37 Thus, MDSCs are expected to be a promising target for treating cancers resistant to ICI therapies. In this regard, blocking LILRB4 on MDSCs could be a therapeutic strategy to restore the immune function and increase the efficacy of ICI therapy in NSCLC patients. Indeed, our previous study showed a synergistic effect of a combination treatment with an anti‐PD‐1 antibody and an anti‐gp49 antibody on inhibiting tumor metastasis in mice. 19 Clinically, a phase 1 first‐in‐human study of anti‐LILRB4 (ILT3) monoclonal Ab MK‐0482 as a monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab in advanced solid tumors (NCT03918278) is in progress. The evaluation of LILRB4 expression on tumor‐infiltrating cells may also serve as a biomarker to predict the efficacy of anti‐LILRB4 antibody therapy in the future.

This study had several limitations. We evaluated LILRB4 expression in samples of NSCLC patients who underwent complete resection. Therefore, our cohort included only a small number of cases with stage III–IV. The clinical impact of LILRB4 expression in patients with advanced stages of NSCLC should be further investigated. We paid particular attention to LILRB4‐mediated immune evasion through the function of MDSCs in this study, but LILRB4 is expressed not only on the myeloid cell lineage but also on B cells and T cells, including regulatory T cells representing PD‐1 high LAG3 high and Tim‐3 high. 18 Thus the LILRB4‐mediated immune evasion system must be comprehensively understood by taking the functions of other immune cells into account, and this will require further fundamental and clinical investigations.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that high LILRB4 expression on tumor‐infiltrating cells in the stroma is associated with postoperative recurrence and a poor prognosis in NSCLC patients who underwent complete resection. Taken together with the results of our in vitro study, which showed a role of LILRB4 in the CD33+ MDSC‐mediated promotion of cancer cell migration, we propose that LILRB4 on tumor‐infiltrating MDSCs could be a promising therapeutic target in NSCLC patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sakiko Kumata: Conceptualization, investigation, validation, formal analysis, writing – original draft preparation, visualization, funding acquisition. Hirotsugu Notsuda: Conceptualization, writing – original draft preparation, project administration. Mei‐Tzu Su: Methodology, investigation, validation, writing – review and editing. Ryoko Saito‐Koyama: Methodology, investigation, validation, writing – review and editing. Ryota Tanaka: Investigation, funding acquisition, writing – review and editing. Yuyo Suzuki: Investigation, writing – review and editing. Junichi Funahashi: Investigation, writing – review and editing. Shota Endo: Resources, writing – review and editing. Isao Yokota: Formal analysis, writing – review and editing. Toshiyuki Takai: Conceptualization, resources, writing – review and editing. Yoshinori Okada: Conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, writing – original draft preparation, supervision.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (20K17737); FY2019 IDAC Young Investigator Grant; and a Grant‐in‐Aid from Kurokawa Cancer Research Foundation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

A patent has been applied for by Tohoku University with S.K., H.N., M.‐T.S., R.S.‐K., R.T., S.E., T.T., and Y.O. as named inventors to Japan Patent Office at the application number PCT/JP2022/027853. I.Y. reports grants from KAKENHI, AMED, and Health, Labour and Welfare Policy Research Grants, research fund by Nihon Medi‐Physics, and speaker fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mr Katsuhiko Ono, laboratory technician of Department of Pathology, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, for his guidance and cooperation in immunohistochemistry. We would also like to thank the staff of the Common Equipment Management Office, Institute of Development, Aging, and Cancer, Tohoku University.

Kumata S, Notsuda H, Su M‐T, Saito‐Koyama R, Tanaka R, Suzuki Y, et al. Prognostic impact of LILRB4 expression on tumor‐infiltrating cells in resected non‐small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14(21):2057–2068. 10.1111/1759-7714.14991

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non–small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Paulsen EE, Kilvaer TK, Rakaee M, Richardsen E, Hald SM, Andersen S, et al. CTLA‐4 expression in the non‐small cell lung cancer patient tumor microenvironment: diverging prognostic impact in primary tumors and lymph node metastases. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1449–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abdel‐Rahman O. Correlation between PD‐L1 expression and outcome of NSCLC patients treated with anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1 agents: a meta‐analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;101:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kok PS, Cho D, Yoon WH, Ritchie G, Marschner I, Lord S, et al. Validation of progression‐free survival rate at 6 months and objective response for estimating overall survival in immune checkpoint inhibitor trials: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kang JH, Bluestone JA, Young A. Predicting and preventing immune checkpoint inhibitor toxicity: targeting cytokines. Trends Immunol. 2021;42:293–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deng Y, Zhao P, Zhou L, Xiang D, Hu J, Liu Y, et al. Epidemiological trends of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer at the global, regional, and national levels: a population‐based study. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown D, Trowsdale J, Allen R. The LILR family: modulators of innate and adaptive immune pathways in health and disease. Tissue Antigens. 2004;64:215–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Katz HR. Inhibition of pathologic inflammation by leukocyte Ig‐like receptor B4 and related inhibitory receptors. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:222–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vlad G, Chang CC, Colovai AI, Berloco P, Cortesini R, Suciu‐Foca N. Immunoglobulin‐like transcript 3: a crucial regulator of dendritic cell function. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:340–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Touw W, Chen HM, Pan PY, Chen SH. LILRB receptor‐mediated regulation of myeloid cell maturation and function. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1079–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Su M‐T, Inui M, Wong YL, Takahashi M, Sugihara‐Tobinai A, Ono K, et al. Blockade of checkpoint ILT3/LILRB4/gp49B binding to fibronectin ameliorates autoimmune disease in BXSB/Yaa mice. Int Immunol. 2021;33:447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takahashi N, Itoi S, Su M‐T, Endo S, Takai T. Co‐localization of fibronectin receptors LILRB4/gp49B and integrin on dendritic cell surface. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2022;257:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paavola KJ, Roda JM, Lin VY, Chen P, O'Hollaren KP, Ventura R, et al. The fibronectin–ILT3 interaction functions as a stromal checkpoint that suppresses myeloid cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9:1283–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deng M, Gui X, Kim J, Xie L, Chen W, Li Z, et al. LILRB4 signaling in leukemia cells mediates T cell suppression and tumor infiltration. Nature. 2018;562:605–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu Z, Chang C‐C, Li M, Zhang Q‐Y, Vasilescu E‐RM, D'Agati V, et al. ILT3.Fc–CD166 interaction induces inactivation of p70 S6 kinase and inhibits tumor cell growth. J Immunol. 2018;200:1207–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang JP, Hielscher A. Fibronectin: how its aberrant expression in tumors may improve therapeutic targeting. J Cancer. 2017;8:674–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Itoi S, Takahashi N, Saito H, Miyata Y, Su M‐T, Kezuka D, et al. Myeloid immune checkpoint ILT3/LILRB4/gp49B can co‐tether fibronectin with integrin on macrophages. Int Immunol. 2022;34:435–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sharma N, Atolagbe OT, Ge Z, Allison JP. LILRB4 suppresses immunity in solid tumors and is a potential target for immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2021;218:e20201811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Su M‐T, Kumata S, Endo S, Okada Y, Takai T. LILRB4 promotes tumor metastasis by regulating MDSCs and inhibiting miR‐1 family miRNAs. Onco Targets Ther. 2022;11:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, Sirtaine N, Klauschen F, Pruneri G, et al. The evaluation of tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TILS) in breast cancer: recommendations by an international TILS working group 2014. Ann Oncol. 2014;2015(26):259–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rakaee M, Kilvaer TK, Dalen SM, Richardsen E, Paulsen E‐E, Hald SM, et al. Evaluation of tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes using routine H&E slides predicts patient survival in resected non–small cell lung cancer. Hum Pathol. 2018;79:188–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pierceall WE, Wolfe M, Suschak J, Chang H, Chen Y, Sprott KM, et al. Strategies for H‐score normalization of preanalytical technical variables with potential utility to immunohistochemical‐based biomarker quantitation in therapeutic reponse diagnostics. Anal Cell Pathol. 2011;34:159–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lechner MG, Liebertz DJ, Epstein AL. Characterization of cytokine‐induced myeloid‐derived suppressor cells from Normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:2273–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Venter C, Niesler CU. Rapid quantification of cellular proliferation and migration using ImageJ. Biotechniques. 2019;66:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi JW, Kim YJ, Yun KA, Won CH, Lee MW, Choi JH, et al. The prognostic significance of VISTA and CD33‐positive myeloid cells in cutaneous melanoma and their relationship with PD‐1 expression. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. He NH, Zhang L, Huang H, Qin DS, Li J. Connecting METTL3 and intratumoural CD33+ MDSCs in predicting clinical outcome in cervical cancer. J Transl Med. 2020;18:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feng PH, Lee KY, Chang YL, Chan YF, Kuo LW, Lin TY, et al. CD14+S100A9+ monocytic myeloid‐derived suppressor cells and their clinical relevance in non‐small cell lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1025–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heiskala M, Leidenius M, Joensuu K, Heikkilä P. High expression of CCL2 in tumor cells and abundant infiltration with CD14 positive macrophages predict early relapse in breast cancer. Virchows Arch. 2019;474:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen MF, Kuan FC, Yen TC, Lu MS, Lin PY, Chung YH, et al. IL‐6‐stimulated CD11b+CD14+HLA‐DR‐ myeloid‐derived suppressor cells, are associated with progression and poor prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Oncotarget. 2014;5:8716–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goldman MJ, Craft B, Hastie M, Repečka K, McDade F, Kamath A, et al. Visualizing and interpreting cancer genomics data via the Xena platform. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:675–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Goeje PL, Bezemer K, Heuvers ME, Dingemans AMC, Groen HJ, Smit EF, et al. Immunoglobulin‐like transcript 3 is expressed by myeloid‐derived suppressor cells and correlates with survival in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;4:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Q, Wei G, Tao T. Leukocyte immunoglobulin‐like receptor B4 (LILRB4) negatively mediates the pathological cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing fibrosis, inflammation and apoptosis via the activation of NF‐κB signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;509:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cicco PD, Ercolano G, Ianaro A. The new era of cancer immunotherapy: targeting myeloid‐derived suppressor cells to overcome immune evasion. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fleming V, Hu X, Weber R, Nagibin V, Groth C, Altevogt P, et al. Targeting myeloid‐derived suppressor cells to bypass tumor‐induced immunosuppression. Front Immunol. 2018;9:398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sato Y, Shimizu K, Shinga J, Hidaka M, Kawano F, Kakimi K, et al. Characterization of the myeloid‐derived suppressor cell subset regulated by NK cells in malignant lymphoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;4:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Draghiciu O, Lubbers J, Nijman HW, Daemen T. Myeloid derived suppressor cells—an overview of combat strategies to increase immunotherapy efficacy. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;4:954829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sade‐Feldman M, Kanterman J, Klieger Y, Ish‐Shalom E, Olga M, Saragovi A, et al. Clinical significance of circulating CD33+ CD11bHLA‐DR myeloid cells in patients with stage IV melanoma treated with ipilimumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5661–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.