Abstract

Background

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) has major benefits for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). An enhanced PR program was developed with a self-management education intervention. The objective of our study was to evaluate the implementation of the enhanced PR program into a single centre.

Methods

Pre-post implementation study consisted of two evaluation periods: immediately after implementation and 18 months later. Guided by the RE-AIM framework, outcomes included: Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance.

Results

Reach: 70–75% of referred patients agreed to a PR program (n = 26). Effectiveness: Clinically important improvements occurred in some patients in functional exercise capacity (64% of the patients achieved clinical important difference in 6-min walk test in the first evaluation period and 44% in the second evaluation period), knowledge, functional status, and self-efficacy in both evaluation periods. Adoption: All healthcare professionals (HCPs) involved in PR (n = 8) participated. Implementation: Fidelity for the group education sessions ranged from 76 to 95% (first evaluation) and from 82 to 88% (second evaluation). Maintenance: The program was sustained over 18 months with minor changes. Patients and HCPs were highly satisfied with the program.

Conclusions

The enhanced PR program was accepted by patients and HCPs and was implemented and maintained at a single expert center with good implementation fidelity.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary rehabilitation, implementation, maintenance, RE-AIM framework

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by symptoms such as coughing, dyspnea and exercise limitations. 1 Individuals with COPD experience frequent exacerbations leading to an increase in symptoms and frequent hospitalizations which causes a significant impact on their quality of life and on the healthcare system.2–4

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is defined as “a comprehensive intervention based on a thorough patient assessment followed by patient-tailored therapies that include, but are not limited to, exercise training, education, and behaviour change, designed to improve the physical and psychological condition of people with chronic respiratory disease and to promote the long-term adherence to health-enhancing behaviours” 5 and is an essential component of COPD management. It is the most effective management strategy to improve shortness of breath, exercise tolerance and health related quality of life6,7 while also having the potential to reduce exacerbations requiring hospital admissions. 8

Despite the major benefits for people with COPD,1,5,9 the availability of PR programs in Canada is low.6,10,11 In addition, in Canada, there is currently a lack of agreed upon evidence-based standards for PR and a high degree of heterogeneity between programs.10,12 A survey of PR programs in Canada published in 2015 identified substantial variation between the 129 existing programs. 11 Duration ranged from 1 week to >12 weeks and exercise type and intensity, as well as educational topics covered varied widely across programs. 10 Self-management focused education is superior to didactic education in promoting adherence and behaviour change. 13 Current PR guidelines recommend that education in PR should use the principles of collaborative self-management to support behaviour change,5,14 however the education in PR programs still most often takes the form of providers giving information in a didactic format. 10 This represents a significant gap between the current best evidence and guideline recommendations and the care currently provided to patients with COPD in Canada.6,12 Low program availability and quality have also been identified in other countries. 15 In fact, the American Thoracic and European Respiratory Societies (ATS/ERS) made recommendations to increase implementation and delivery of PR worldwide which included improving quality of PR programs and increasing awareness and knowledge of PR amongst healthcare professionals (HCPs), taxpayers and patients.11,16

To ensure the quality of care in PR programs in Canada and facilitate implementation, in 2016 a group of clinicians and researchers from across Canada developed a standardized, enhanced PR program which incorporates proven self-management and behaviour change strategies adapted from the Living Well with COPD (LWWCOPD) curriculum. 17 This program has recently been endorsed by the Canadian Thoracic Society and includes guidelines and tools for patients’ referral and assessments, exercise type, duration and intensity, educational topics, and delivery as well as long-term follow-up. It provides HCPs with a clearly defined plan from the initial evaluation of patients with COPD to the maintenance phase of disease management.

A randomized controlled trial conducted by our research team 17 compared the enhanced PR program with a traditional PR program and showed that the enhanced PR program had similar improvements in physical activity, self-efficacy, and health outcomes as the traditional PR programs. 17 However, the enhanced program had the added benefit of reducing healthcare utilization. 17 The enhanced PR program has also been shown to be suitable to telehealth settings to increase availability of PR in rural areas, and confer improvements in health outcomes. 18 Yet, the process of implementing this program to clinical sites and the factors affecting implementation have not been studied to date. The findings of implementation research can help clinicians, researchers, administrators, and policy makers find potential solutions to promote the large-scale use and sustainability of a new treatment or program. 19

Our first aim was to evaluate the implementation of an enhanced PR program at a single site at two time points. For this, we used the RE-AIM framework 20 (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance). A second aim of this study is to identify the facilitators and barriers to the implementation and maintenance of the program as perceived by patients with COPD and HCPs administering PR as well as their satisfaction with the overall program.

Methods

Design and participants

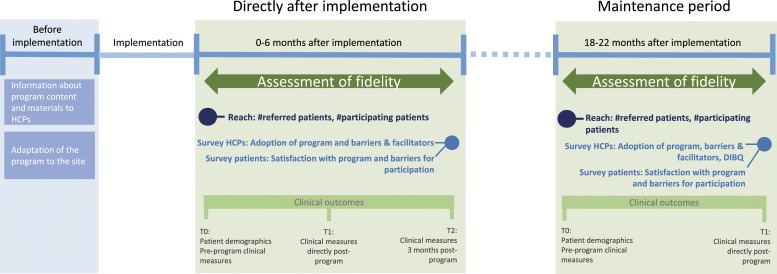

This single-site study implementation study has a prospective pre-post design using the RE-AIM framework 20 to evaluate the enhanced PR program on reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (Table 1). As the enhanced PR program has already been tested in an RCT, effectiveness was not a primary focus for this study. The study consisted of two evaluation periods (two different cohorts): 1) first 6 months directly after implementation and 2) 18 months after implementation (Figure 1). Outcomes were assessed on an individual level (patients) and organization levels (PR program/HCPs). Participants included for this study were:

• Patients enrolled in the enhanced PR program, with a diagnosis of COPD confirmed by post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 0.7 1 .

• HCPs involved in the PR program including individuals licensed in nursing, respiratory therapy, physiotherapy, occupation therapy, social work, and nutrition.

Table 1.

Domains of the RE-AIM framework.

| Domain | Definition | Assessment level | Operationalization within study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | The absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of individuals who are willing to participate in a given initiative | Individual level | •Number of patients referred to program •Number of patients accepting to participate in the program •Characteristics of participating patients |

| Effectiveness | The impact of an intervention on important outcomes, including potential negative effects, quality of life, and economic outcomes | Individual level | Percentage of patients with positive clinical outcomes pre and post program |

| Adoption | The absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of settings and intervention agents who are willing to initiate a program | Organization level | •The proportion of HCPs following the enhanced PR program out of the total HCPs involved in PR at the study site •Characteristics of HCPs involved in PR at study site |

| Implementation | At the setting level, implementation refers to the intervention agents’ fidelity to the various elements of an intervention’s protocol. This includes consistency of delivery as intended and the time and cost of the intervention | Organization level | •Fidelity on content and delivery of the group education sessions by the HCPs involved •Changes to the program and reasons |

| Maintenance | At the individual level, maintenance has been defined as the long-term effects of a program on outcomes after 6 or more months after the most recent intervention contact | Individual level | Percentage of patients with positive clinical outcomes at 3-month follow-up |

| The extent to which a program or policy becomes institutionalized or part of the routine organizational practices and policies | Organization level | •Reach as described above within new PR cycles 18 months after initial implementation of the program •Effectiveness as described above within new PR cycles 18 months after initial implementation of the program •Adoption: changes to PR staff •Implementation as described above within new PR cycles 18 months after initial implementation of the program + fidelity to exercise recommendations |

Available from www.re-aim.org.

Figure 1.

Study design.

Patients with a diagnosis other than COPD, with cognitive impairments who were unable to accurately complete questionnaires, and who could not understand either English or French were excluded. The Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) was used to report this study. 21

Study site and recruitment

The study took place at the PR outpatient program of the Montreal Chest Institute which is located at the McGill University Health Centre, in Montreal, Canada. The Montreal Chest Institute is a public centre of clinical, research and teaching expertise in respiratory diseases. It provides specialized ambulatory as well as inpatient programs for a variety of respiratory diseases. The first evaluation period occurred in August 2017-February 2018; the second between March 2019-June 2019. All HCPs were invited to participate and were included when they provided informed consent.

Previous existing program of the Montreal Chest Institute and the enhanced PR program

The previous existing outpatient PR program included both weekly group education sessions (10 in total) and supervised exercise three times per week for 6 weeks. The education sessions contained a mixture of didactic and self-management focused education style. The sources and topics were not standardized, and their quality and content were dependent on the professionals’ expertise.

The enhanced PR program contains all essential components that have been recommended by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 14 in addition to proven self-management and behaviour change strategies (adapted from the LWWCOPD) which was listed as desirable component of PR by ATS. 14 The enhanced PR program is a comprehensive program package that provides recommendations, tools, and materials for PR on screening & referral, education, exercise program, evaluation & outcome assessment, and healthy lifestyle. It is accessible through www.livingwellwithcopd.com, under the section “Rehabilitation” when signing up as a professional.

Implementation strategies

Before the evaluation started, all HCPs involved received an initial 1-day group training where the program content, goals, and motivational communication techniques were presented and discussed. Feedback from HCP’s involved in the program was incorporated into the final implementation plan.

Outcome measures

Outcomes are guided by the domains of the RE-AIM framework 20 (Table 1).

Reach: the number of individuals referred for PR, number of patients with COPD participating in the enhanced PR program, reasons for not participating and characteristics of the included individuals.

Effectiveness: the number and percentage of patients that improved more or equal to the minimal clinical important difference (MCID) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Measures and instruments used to assess effectiveness at the patient level.

| Outcome measure | Measurement instrument | Clinical important difference | How data was collected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional exercise capacity | 6MWT | ≥33m ↑ | Part of program, obtained by HCP’s |

| Health status | CAT | ≥2 points ↓ | |

| Patient report of difficulty or ease in daily activities | FPI-SF+ | ≥0.5 points ↑ | Additional questionnaires, obtained by researcher |

| Knowledge | LINQ | ≥1 point ↓ | |

| BCKQ | ≥3% ↑ | ||

| Self-efficacy | SEAMS+, SEWS+ and MSEES+* | ≥10% ↑ |

↑ an increase of clinical important difference is a positive outcome. ↓ a decrease of clinical important difference is a positive outcome. + No MCID was found in the literature for the Functional Performance Inventory Short Form (FPI-SF) and the self-efficacy questionnaires. Based on clinical expertise we used an increase of 0.5 points as minimal change for the FPI-SF and an increase of 10% as minimal change for the self-efficacy questionnaires. *score from the MSEES is split into four subscores following the example of Selzler et al. 2019. Abbreviations: 6MWT = Six Minute Walk Test, CAT = COPD Assessment Test, HCP = Health care professionals, FPI-SF = Functional Performance Inventory Short Form, LINQ = Lung Information Needs Questionnaire, BCKQ = Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire, SEAMS = Self-Efficacy for Appropriate Medication use Scale, SEWS = Self-Efficacy for Walking Scale, MSEES = Multidimensional Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale.

Adoption: the proportion of HCPs that follow the enhanced PR program out of the total HCPs involved in PR; characteristics of the HCPs.

Implementation: Key components on content and delivery for each education session were identified to create fidelity checklists. 22 Both were scored on a 7-point Likert scale (Supplemental Table 1). Two investigators attended the first two sessions and results were discussed to adjust future assessments and minimize bias.

Maintenance at individual level: clinical outcomes at 3-month follow-up (knowledge, self-efficacy, and the patient report of ease or difficulty in daily activities)

Maintenance at program level: all outcome measures on reach, effectiveness, adoption, and implementation repeated at 18 months. As the evaluation of the implementation was a learning process, some outcomes were changed or added. For the domain Adoption, changes in staff were tracked. For the Implementation domain, the exercise sessions were assessed for fidelity. The duration, number of sessions, home exercise, types of exercise, monitoring and the use of strategies to determine exercise intensity were compared to the programs’ recommendations.

Program satisfaction, facilitators and barriers to implementation and maintenance

Patients and HCPs were asked to fill out surveys during both evaluation periods. The surveys consisted of closed- and open-ended questions (Supplemental File 1). Patients were asked about their satisfaction with the program components and potential barriers for participation. HCPs were asked about their satisfaction with the content. The Determinants of Implementation Behaviour Questionnaire (DIBQ) 23 was used to determine HCPs’ attitudes about the program and its implementation.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Montreal University Health Centre Research Ethics Board (2018-3734 and 2019-5344). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before participation in the study.

Analysis

Since this was an implementation study and thus effectiveness was not a primary focus of the study, we did not calculate sample size a priori. The number of individuals who participated in the two evaluation periods were the number of individuals referred for PR during the two study periods and who accepted to participate in the enhanced PR program. Outcomes on reach, adoption and implementation were analyzed descriptively. T-tests for patient characteristics were performed to compare participants that completed and participants who did not complete the program during the first evaluation period. For each of the education sessions, items with good fidelity were identified when they had a score of ≥5 (Mostly complete with minor omissions). Changes in patient outcomes pre- and post-program and for the 3-month follow-up were calculated. The percentage of participants who improved more or equal to the minimal clinical important difference (MCID) was calculated.

Facilitators and barriers were summarized from the open-ended questions of the patients’ and HCPs’ surveys. Due to the small number of participants, all responses were considered. When two or more responses were similar, they were merged into the same facilitator or barrier descriptor. Domain-scores were calculated for the Determinants of Implementation Behaviour Questionnaire (DIBQ), categorized, and frequencies were calculated. SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used for the descriptive analysis.

Results

Reach

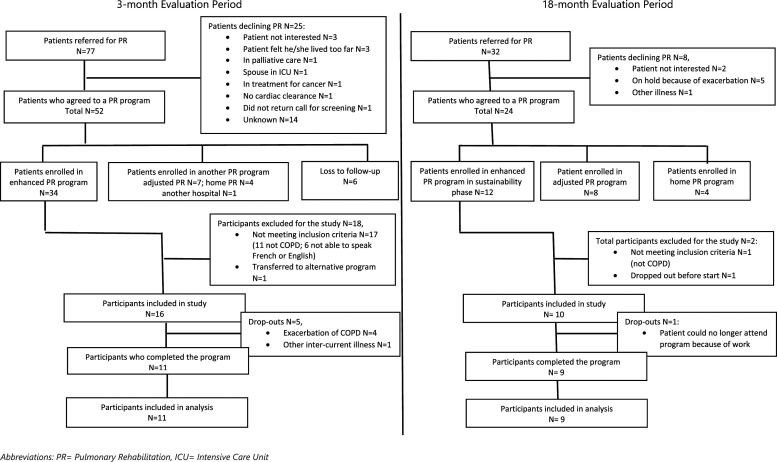

Figure 2 presents the patient referral and participant inclusion information from both evaluation periods. 16 patients in the first evaluation period and 10 patients in the second evaluation period were included (Table 3). In the first evaluation period, five (31%) patients dropped out, because of exacerbation (n = 4) or another illness (n = 1). These patients had a higher CAT-score (mean difference 10.6 ± 2.4, p = 0.001) and a higher BODE-index (mean difference 2.7 ± 1.1, p = 0.04) than the patients who completed the PR program. During the maintenance evaluation period only one participant dropped out.

Figure 2.

Domain Reach: Flowchart patient referral and study inclusion.

Table 3.

Domain reach: participant characteristics.

| Characteristic | First evaluation period | Second evaluation period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (range)N = 16 | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD (range)N = 10 | |||

| Completed the studyN = 11 | Did not complete the studyN = 5 | ||||

| Age | 69.6 ± 7.5 (57–87) | 69.5 ± 7.5 | 70 ± 8.4 | 67.4 ± 6.8 (53–76) | |

| Sex, Female, n (%) | 9 (56) | 6 (54.5) | 3 (60) | 7 (70) | |

| BMI | 26.7 ± 9.7 (15–59) | 25.2 ± 4.4 | 30 ± 16.9 | 29.2 ± 8.0 (17–41) | |

| Smoking status, ex-smoker, n (%) | 16 (100) | 11 (100) | 5 (100) | 10 (100) | |

| Pack-years | 46.6 ± 23.8 (25–120) | 38.75 ± 8.8 | 59.2 ± 35.3 | 41.1 ± 8.7 (30–52) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| CVD, n (%) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | |

| Asthma, n (%) | 4 (25) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (60) | 2 (20) | |

| Other lung disease, n (%) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (20) | 3 (30) | |

| Other, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (30) | |

| FEV1 % predicted | 47.5 ± 17.1 (20–76) | 49.9 ± 17.2 | 42.2 ± 17.7 | 56.4 ± 11.9 (36–79) | |

| FEV/FVC ratio | 0.45 ± 0.11 (0.19–0.66) | 0.45 ± 0.12 | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 0.52 ± 0.11 (0.32–0.71) | |

| 6MWT (m) | 339 ± 102 (100–460) | 381 ± 48 | 245 ± 130 | 369 ± 107 (140–485) | |

| MRC-score category, n (%) | |||||

| 2 | 5 (31.3) | 4 (36) | 1 (20) | 1 (10) | |

| 3 | 6 (37.5) | 5 (46) | 1 (20) | 4 (40) | |

| 4 | 3 (18.8) | 1 (9) | 2 (40) | 4 (40) | |

| 5 | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 1 (20) | 1 (10) | |

| CAT-score | 16.7 ± 6.3 (8–28) | 13.9 ± 4.4 | 24.5 ± 3.1 | 21.0 ± 6.9 (12–33) | |

| HADS anxiety | 6.8 ± 3.1 (2–13) | 6.7 ± 3.5 | 7.0 ± 2.6 | 8.1 ± 4.6 (3–15) | |

| HADS depression | 5.6 ± 3.8 (1–12) | 5.0 ± 3.9 | 6.8 ± 4.0 | 6.5 ± 3.3 (2–11) | |

| HADS total | 12.5 ± 6.0 (6–12) | 11.7 ± 6.0 | 13.8 ± 6.6 | 14.6 ± 7.1 (6–25) | |

| BODE index | 3.6 ± 2.5 (0–10) | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 5.4 ± 3.0 | 3.3 ± 1.9 (1–7) | |

| Attendance group education sessions a | 11/11 (100%) | 11/11 (100%) | 5/10 (50%) | 6/12 (50%) | |

| Attendance exercise sessions a | 17/17 (100%) | 17/17 (100%) | 9/15 (60%) | 14/15 (100%) | |

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation, N = number of patients, BMI = Body Mass Index, CVD = Cardiovascular disease, FEV1 = Forced Expiration Volume in one second, 6MWT = 6 Minute Walk Test, MRC-score = Medical Research Council score, CAT-score = COPD Assessment Test score, HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, BODE = Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea and Exercise capacity.

aMedian number of education/exercise sessions attended/median number of education/exercise sessions scheduled.

Effectiveness

The outcomes for effectiveness are depicted in Supplemental Table 2. Clinically important improvements for patients directly post-program in both evaluation periods were shown for functional exercise capacity, knowledge, functional status, and self-efficacy for walking. Missing data ranged from 9% to 78%.

Adoption: All HCPs (N = 8, 100%) working in PR program at the Montreal Chest Institute adopted the enhanced PR program. (Supplemental Table 3)

Implementation

At the start of each cycle, patients were given a schedule of group education and exercise sessions. Some flexibility was required, e.g., some patients did an adjusted program, or a home program and some changes were made in the order of group education sessions and slides. For implementation fidelity, 14 group education sessions were scored (Table 4). From these sessions, 76% of the items for content and 95% of the items for delivery received a good fidelity score (≥5/7) in the first evaluation and 82% of the items for content and 88% of the items for delivery received a good fidelity score in the second evaluation.

Table 4.

Domain Implementation: Fidelity scores for the group education sessions.

| Session number | Session name | Given by | Mean ratio of good fidelity a (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First evaluation | Second evaluation | |||||

| Content | Delivery | Content | Delivery | |||

| #1 b | Living well and breathing easy | Nurse | 4/5 (80) | 3/3 (100) | 4/5 (80) | 2.3/3 (77) |

| #4 b | Breathing management | Physiotherapist | 5/5 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 3.7/5 (74) | 2.3/3 (77) |

| #5 | Conserving energy | Occupational therapist | 2.5/4 (62.5) | 3/3 (100) | 3.5/4 (87.5) | 2.75/3 (92) |

| #6 | Medications for chronic lung disease | Nurse | 4.5/5 (90) | 3/3 (100) | 4.5/5 (90) | 3/3 (100) |

| #7 | Inhaler devices | Respiratory therapist | 4/4 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 3.3/4 (82.5) | 3/3 (100) |

| #8 | Integrating an exercise program into your life | Physiotherapist | Not scored | Not scored | 3/5 (60) | 3/3 (100) |

| #9 | Management of respiratory infections | Nurse | 4/5 (80) | 3/3 (100) | 4.5/5 (90) | 3/3 (100) |

| #10 | Management of aggravating environmental factors | Nurse | 4/4 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 3.5/4 (87.5) | 3/3 (100) |

| #11 | Management of anxiety and stress | Social worker | 2.5/5 (50) | 3/3 (100) | 4/5 (80) | 3/3 (100) |

| #12 | Nutrition and lung health | Nutritionist | 2.7/4 (68) | 1.7/3 (57) | 3/4 (75) | 1.7/3 (57) |

| Ratio of good fidelity total c (mean percentage) | 48/63 (76) | 38/40 (95) | 93/113 (82) | 66/75 (88) | ||

aGood fidelity is defined as a score ≥5 (Mostly complete with minor omissions) on a 7-point scale.

bSession #1 (Living well and breathing easy) & #3 (Living well with chronic lung disease) and sessions #2 (Exercise) & #4 (Breathing management) were merged. The score forms for session #1 and for session #4 were used.

cNumber of items with good fidelity/total number of items that are scored.

Maintenance at patient level

At the 3-month follow-up, the percentage of patients who showed clinically important improvements in knowledge, self-efficacy for exercise and self-reported functional performance compared to baseline was 73%, 55% and 9% respectively. The percentage of patients that showed clinically important improvements in knowledge, self-efficacy for exercise and self-reported functional performance compared to post-program was 55%, 9% and 0% respectively (Supplemental Table 4).

Maintenance at program level

The enhanced PR program was still being delivered at the Montreal Chest Institute 18 months after initial implementation. The same HCPs were involved in the program and participated in the study. No further changes had been made. During the second evaluation period, 32 group education sessions were scored for implementation fidelity (Table 4). A good fidelity score (≥5/7) was achieved for 82% of the items for content and 88% of the items for delivery. Data on exercise sessions were extracted for nine patients from their medical records. The duration of the program was 6 or 7 weeks with 15 exercise sessions planned but varied from 5 to 12 weeks, with an average of 7 weeks which is between the recommended duration of 6–12 weeks. The recommendations of the enhanced PR program regarding home exercise, types of exercise, monitoring and the use of strategies to determine exercise intensity were followed.

Satisfaction, facilitators and barriers to implementation and maintenance

Patient satisfaction was very high in both evaluation periods (overall average score 9.5 ± 0.9/10 in the first evaluation; 83% of patients very satisfied in the second evaluation (Supplemental Tables 5A and 5B). HCPs were also very satisfied with the enhanced PR program with an overall average score of 8.1 ± 1.4/10 in the first evaluation, (Supplemental Table 5C). They were less satisfied with the introduction of the program (mean score 6.7 ± 2.8) and the facilitator notes and resources for the education sessions (mean score 6.4 ± 3.4). HCPs commented that they needed French materials, and this was provided prior to the second evaluation. DIBQ scores are shown in Supplemental Table 6.

Barriers that patients mentioned in the surveys were: 1) bilingual group education sessions, 2) weather conditions and 3) long travel distance. Facilitators were: 1) participating in a group, 2) patient-specific adjustments of the program, 3) exercise and education sessions scheduled right after each other (reducing travel), and 4) being accompanied by someone.

From the open-ended survey for HCPs during the second evaluation period, the barriers mentioned for implementation and maintenance were: 1) lack of time, 2) having other priorities, and 3) changes needed in slides. Facilitators were: 1) longstanding procedure for assessments, 2) having a large team with many disciplines, and 3) being familiar with LWWCOPD self-management program.

Discussion

This study provides, for the first time, a multilevel evaluation of the enhanced PR program including implementation and maintenance of the program. We found that the enhanced PR program was successfully implemented to the Montreal Chest Institute and accepted by both patients and HCPs. Adoption was maximal for this study as all HCPs were willing to adopt the enhanced PR program. The program was maintained over 18 months with high fidelity scores. Moreover, the HCPs were committed to further sustainment of the enhanced PR program. Our evaluation showed clinically important improvements for functional exercise capacity, knowledge, functional status, and self-efficacy for walking in the majority of the participants post-program and at 3-month follow-up.

With 70–75% of the patients agreeing to do a rehabilitation program, the reach of the overall enhanced PR program was high compared to other studies reporting uptake of PR ranging from 8.3 to 49.2%.24,25 There were many patients that were not enrolled in the enhanced PR program due to barriers which prevented them from attending a regular outpatient program. For example, patients who were too frail to participate in the outpatient program received a prescription of a home exercise program. This finding highlights the need to improve access to a variety of PR programs that can be delivered in different contexts such as tele-medicine PR and home PR programs26,27 where the resources of the enhanced program can be used as a standard.

Factors that contributed to the successful implementation to the Montreal Chest Institute were that the HCPs had been working together for many years in an existing PR program and they were familiar with the LWWCOPD program prior to implementation. In addition, the Montreal Chest Institute has a very high number of professionals dedicated to the PR program (N = 8) compared to data from a Canadian survey in 2015 10 (median 4, interquartile range 3–6). It is expected that the implementation of the enhanced PR program into sites that have fewer and/or less experienced HCPs available will be more challenging. In these settings, new barriers for implementation and maintenance of the program may be encountered. Finally, this project had strong support from the director of the PR program (JB) who was also an investigator in this study which likely influenced the participation of all HCPs in the study and willingness to adopt the enhanced program.

The main strength of our study is the use of the RE-AIM framework, which ensured a rich program evaluation on multiple levels and on multiple domains in a real-life setting. Implementing evidence-based knowledge into practice is a complex process28–31 but can improve the quality of health care and patient outcomes. 32 To our knowledge, there are no studies that have assessed the implementation of an evidence-based and comprehensive PR program in a hospital setting using an implementation framework. Some studies have used behaviour change frameworks to investigate implementation barriers, 33 but none evaluated the process of implementing evidence-based PR into clinical sites.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, only one site was included and thereby the generalizability to other potential sites is limited. Secondly, as there was a small sample, no formal statistical testing in clinical outcome measures and no conclusions for effectiveness were made. In addition, we found low percentage of patients that improved more or equal to the MCID for several outcome measures. However, the effectiveness of the enhanced PR program has been tested in two previous studies.17,18 In a prior RCT, we showed that the enhanced PR program had the added benefit of reducing health care utilization, as well as similar improvements in physical activity, self-efficacy and health outcomes compared to a traditional PR program. 17 In a pre-post study, Etruw et al. 18 showed that the enhanced PR program offered in Canadian rural settings led to improvements in functional exercise capacity measure by the 6MWT and disease burden measured by the COPD Assessment Test. Thirdly, only one researcher performed the fidelity assessments, which may have affected the fidelity results. To minimize bias, a second researcher attended the first two sessions and results were discussed to adjust future assessments. Lastly, our study does not include all elements of scalability, such as costs of this intervention. As this is a crucial element of scalability of the program, it is recommended to assess this in further research.

With the experienced HCPs, the likelihood of a successful implementation was high for this site. Still, this study provides some lessons learned for future implementation of the enhanced PR program, which are: 1) A clearer introduction of the program based on the knowledge and experience of the HCPs on PR was needed, 2) The HCPs wanted to be better informed about the programs’ resources (e.g. facilitator notes, presentation slides and reference guides for the group education sessions) and 3) HCPs should be allowed to adapt some of the programs’ components for feasibility, such as the order of group education sessions and the slides used for these sessions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the enhanced PR program was accepted by patients and HCPs and was implemented and maintained at a single expert center with good implementation fidelity. The enhanced PR program can be used by HCPs or healthcare managers to start a new program or increase the quality of an existing program. All resources and recommendations are available without cost on www.livingwellwithcopd.com (sign-up as a professional under the tab Canadian PR program).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Implementation and maintenance of an enhanced pulmonary rehabilitation program in a single centre: An implementation study by Kim van der Braak, Joshua Wald, Catherine M Tansey, Thais Paes, Maria Sedeno, Anne-Marie Selzler, Michael K Stickland, Jean Bourbeau and Tania Janaudis-Ferreira in Chronic Respiratory Disease

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sébastien Gagnon for his help with the collection of the data. Our special thanks are extended to the staff of the PR program at the Montreal Chest Institute.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Edith Strauss Foundation.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Anne-Marie Selzler https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4178-2905

Jean Bourbeau https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7649-038X

Tania Janaudis-Ferreira https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0944-3791

References

- 1.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2017; 195: 557–582. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TA. COPD exacerbations: defining their cause and prevention. The Lancet 2007; 370: 786–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, et al. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1998; 157: 1418–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CIfH Information . Inpatient hospitalizations, surgery and newborn Statistics, 2019-2020. Ottawa, ON: CIHI, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2013; 188: e13–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marciniuk DD, Brooks D, Butcher S, et al. Optimizing pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease–practical issues: a Canadian Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Canadian Respiratory Journal 2010; 17: 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nici L, Donner C, Wouters E, et al. American thoracic society/European respiratory society statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2006; 173: 1390–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD: American college of chest physicians and Canadian thoracic society guideline. Chest 2015; 147: 894–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puhan MA, Lareau SC. Evidence-based outcomes from pulmonary rehabilitation in the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patient. Clinics in Chest Medicine 2014; 35: 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camp PG, Hernandez P, Bourbeau J, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation in Canada: a report from the Canadian thoracic society COPD clinical assembly. Canadian Respiratory Journal 2015; 22: 147–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rochester CL, Vogiatzis I, Holland AE, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society policy statement: enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2015; 192: 1373–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dechman G, Cheung W, Ryerson CJ, et al. Quality indicators for pulmonary rehabilitation programs in Canada: A Canadian Thoracic Society expert working group report. Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine 2019; 3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Effing TW, Vercoulen JH, Bourbeau J, et al. Definition of a COPD self-management intervention: International Expert Group consensus. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 46–54. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.00025-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland AE, Cox NS, Houchen-Wolloff L, et al. Defining modern pulmonary rehabilitation. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18: e12–e29. DOI: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202102-146ST.. 2021/05/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desveaux L, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Goldstein R, et al. An international comparison of pulmonary rehabilitation: a systematic review. COPD 2015; 12: 144–153. DOI: 10.3109/15412555.2014.922066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogiatzis I, Rochester CL, Spruit MA, et al. Increasing implementation and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation: key messages from the new ATS/ERS policy statement. Eur Respiratory Journal, 2016; 47: 1336–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selzler A-M, Jourdain T, Wald J, et al. Evaluation of an enhanced pulmonary rehabilitation program: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 2021; 18: 1650–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etruw E, Fuhr D, Huynh V, et al. Short-term health outcomes of a structured pulmonary rehabilitation program implemented within rural canadian sites compared with an established urban site: a pre-post intervention observational study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2022; 104: 753–760. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2022.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer MS, Kirchner J. Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res 2020; 283: 112376. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health 1999; 89: 1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ 2017; 356: i6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourbeau J, Lavoie KL, Sedeno M, et al. Behaviour-change intervention in a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled COPD study: methodological considerations and implementation. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e010109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunstler BE, Cook JL, Kemp JL, et al. The self-reported factors that influence Australian physiotherapists’ choice to promote non-treatment physical activity to patients with musculoskeletal conditions. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2019; 22: 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keating A, Lee A, Holland AE. What prevents people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from attending pulmonary rehabilitation? A systematic review. Chron Respir Dis 2011; 8: 89–99. DOI: 10.1177/1479972310393756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National COPD Audit Programme . Pulmonary rehabilitation workstream. Pulmonary rehabilitation: steps to breathe better. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selzler A, Wald J, Sedeno M, et al. Telehealth pulmonary rehabilitation: a review of the literature and an example of a nationwide initiative to improve the accessibility of pulmonary rehabilitation. Chronic Respiratory Disease 2018; 15: 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vieira DS, Maltais F, Bourbeau J. Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine 2010; 16: 134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrison MB, Légaré F, Graham ID, et al. Adapting clinical practice guidelines to local context and assessing barriers to their use. Cmaj 2010; 182: E78–E84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, et al. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. Bmj 2013; 347: f6753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, et al. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implementation Science 2008; 3: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 2006; 26: 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. The Lancet 2003; 362: 1225–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox NS, Scrivener K, Holland AE, et al. A brief intervention to support implementation of telerehabilitation by community rehabilitation services during COVID-19: A feasibility study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2021; 102: 789–795. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Implementation and maintenance of an enhanced pulmonary rehabilitation program in a single centre: An implementation study by Kim van der Braak, Joshua Wald, Catherine M Tansey, Thais Paes, Maria Sedeno, Anne-Marie Selzler, Michael K Stickland, Jean Bourbeau and Tania Janaudis-Ferreira in Chronic Respiratory Disease