Abstract

Background:

Phthalates are endocrine-disrupting chemicals linked to a higher risk of numerous chronic health outcomes. Diet is a primary source of exposure, but prior studies exploring associations between dietary patterns and phthalate exposure are limited.

Objectives:

We evaluated the associations between dietary patterns and urinary phthalate biomarkers among a subset of postmenopausal women participating in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).

Methods:

We included WHI participants selected for a nested case-control study of phthalates and breast cancer (N=1240). Dietary intake was measured via self-administered food frequency questionnaires at baseline and year-3. We used these data to calculate scores for alignment with the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH), alternative Mediterranean (aMed), and Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) diets. We measured 13 phthalate metabolites and creatinine in 2 to 3 urine samples per participant collected over 3-years when all participants were cancer-free. We fit multivariable generalized estimating equation models to estimate the cross-sectional associations.

Results:

DASH and aMed dietary scores were inversely associated with the sum of di(2-Ethylhexyl) phthalate (−6.48%, 95% CI −9.84, −3.00; −5.23%, 95% CI −8.73, −1.60) and DII score was positively associated (9.00%, 95% CI 5.04, 13.11). DASH and aMed scores were also inversely associated with mono benzyl phthalate and mono-3-carboxypropyl phthalate. DII scores were positively associated with mono benzyl phthalate and the sum of di-n-butyl phthalate.

Discussion:

Higher dietary alignment with DASH and aMed dietary patterns were significantly associated with lower concentrations of certain phthalate biomarkers, while an inflammatory diet pattern was associated with higher phthalate biomarker concentrations. These findings suggest that dietary patterns high in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat foods and low in processed foods may be useful in avoiding exposure to phthalates.

Keywords: phthalate, DASH, aMed, DII, biomarkers, diet

Introduction

Phthalates are increasingly linked to a higher risk of numerous chronic health outcomes, including obesity and diabetes (1). These synthetic chemicals are well-established as endocrine disruptors, and human exposure is ubiquitous due to their wide use in consumer products (e.g., cosmetics, perfumes, toys, shampoos, dentures, adhesives, cleaning materials, nutritional supplements, and food packaging) (2–4).

In adults, dietary intake is a primary source of phthalate exposure, as phthalates are a common component of food packaging materials (4–7). Food products become contaminated with phthalates as a result of phthalates leaching from that packaging. Moreover, the lipophilic characteristics of some phthalates make the chemicals more likely to “stick” to foods high in fat, and these foods expose consumers to higher phthalate levels. Two recent studies measuring the concentration of phthalate biomarkers in commonly consumed foods and beverages found higher concentrations of DBP, DEHP, and di-isobutyl phthalate (DiBP) in high-fat foods and sugary beverages (e.g., meat products, bread, margarine, canned dinners, deli meats, cheese, sweetened teas, and sodas) compared to whole fruits and vegetables (6,8,9).

Prior human studies have identified individual food groups (e.g., meat and meat products, bread, milk and milk products, cheese, and fish and fish products) that are associated with higher urinary phthalate biomarker concentrations (10–13). Additionally, consumption of fast food, food not prepared at home, and processed foods, all of which tend to be highly packaged, were associated with higher urinary concentrations of DEHP and diisononyl phthalate (DiNP) metabolites (14). Consumption of a western diet, as compared to a vegetarian diet, was also associated with higher urinary DEHP biomarker concentrations (15). Recently, Buckley et al. (16) and Martinez Steele et al. (17) observed that ultra-processed foods (e.g., sandwiches, hamburgers, french-fries, other potato products, ice cream, and sodas) were associated with higher urinary concentrations of DiNP metabolites, mono (3-carboxypropyl) phthalate (MCPP), monocarboxy-isononyl phthalate (MCNP), and mono-carboxy octyl phthalate (MCOP) among individuals six years and older.

While exploring exposure from specific food groups is of interest, dietary patterns may be more predictive of overall health status and future chronic disease risk than single food groups and nutrients (18,19). Dietary patterns consider the quantity, variety, and combination of different foods, drinks, and nutrients consumed. Challenges of evaluating individual foods or food groups include high correlations between individual nutrients, associations with an individual food group or nutrient that may be too small to detect, and statistically significant associations that may result simply by chance or from overuse of analytical tests (18,20).

Several dietary patterns are associated with future chronic disease risk. The Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet is designed to treat and prevent hypertension without medication (21). The DASH diet focuses on reduced sodium intake and increased consumption of foods rich in potassium, calcium, and magnesium (e.g., vegetables, fruits, and low-fat dairy foods, whole grains, fish, poultry, and nuts). Similarly, the Mediterranean diet emphasizes consuming fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and legumes (22). Additional recommendations include olive oil as the primary form of fat, low to moderate consumption of cheese, yogurt, fish, poultry, a week, and rare consumption of red meat. The dietary inflammation index (DII) is a quantitative means of assessing the inflammatory potential of diets, based on work identifying dietary exposure associated with blood concentrations of inflammatory cytokines (23–25). DII has been identified as a key tool in characterizing the inflammatory potential of diets and predicting chronic disease incidence and mortality (26,27).

Few prior studies have explored the associations between these dietary patterns and urinary phthalate biomarker concentrations. Therefore, we evaluated the associations between the DASH, aMed, and DII dietary indices and urinary phthalate biomarker concentrations among a subset of postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).

Materials and Methods

Study Population

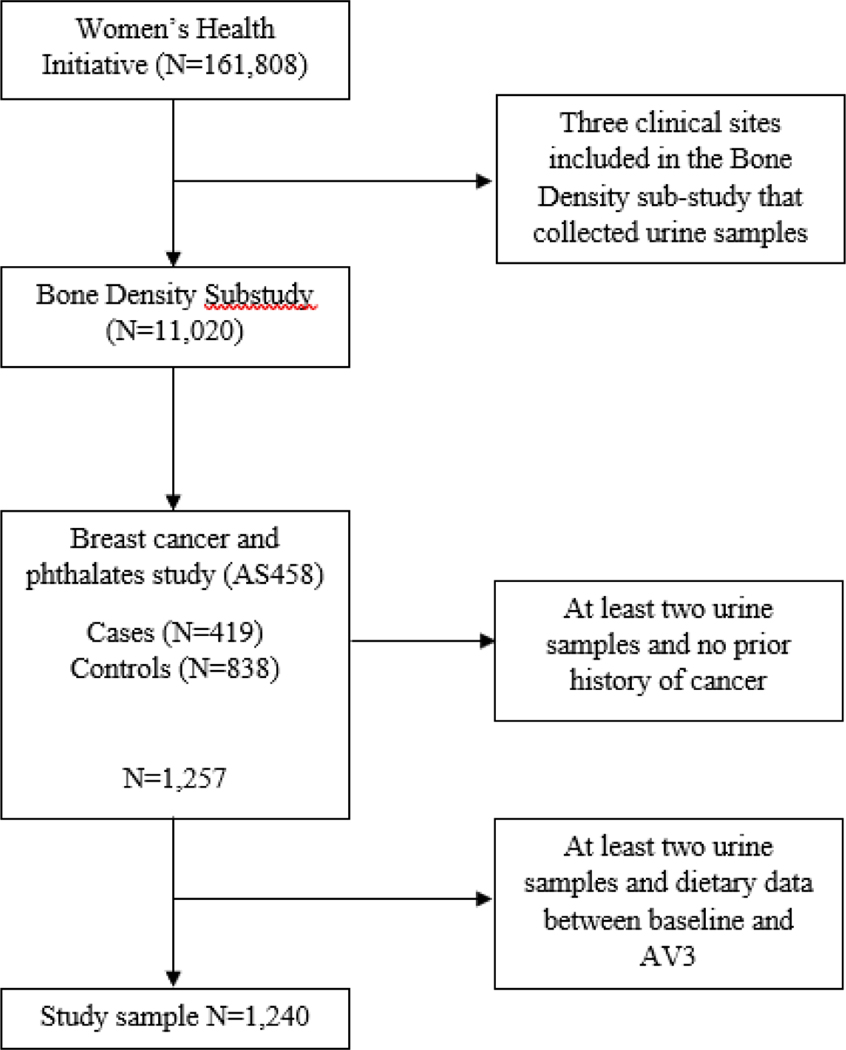

As previously described, the WHI recruited 161,808 postmenopausal women from 40 clinical centers nationwide between October 1, 1993, and December 21, 1998 (28) All participants were between the ages of 50 to 79 years at enrollment and participated in one or more of four clinical trials (CT; N=68,132) or an observational study (OS; N=93,676). Participants of a bone density substudy at three WHI sites (Birmingham, AL; Pittsburgh, PA; Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) provided first-morning void urine samples at baseline, annual visit (AV) 1, and AV3 (N=11,020) and were eligible for inclusion in a previously conducted prospective nested case-control study of phthalate biomarkers and breast cancer (N=1,257) (29). A total of 419 invasive breast cancer cases and 838 controls, 1:2 matched on enrollment date, length of follow-up, age at enrollment, and study arm, were selected (Figure 1). Only invasive breast cancer cases diagnosed after AV3 were included, to ensure that urinary phthalate biomarkers were measured before diagnosis. Participants eligible for the present analysis met the following criteria: 1) at least two urine samples between baseline and AV3 and 2) dietary exposure data at baseline and AV3 (N=1,240).

Figure 1.

Population selection flow chart of the study population.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants upon their enrollment into WHI, and approval was received from institutional review boards (IRB) at each WHI clinical center. The University of Massachusetts Amherst IRB additionally approved the present research. The involvement of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) laboratory in the analysis of samples did not constitute an engagement in human subjects research.

Dietary Pattern Measurement

Dietary intake was assessed at both baseline and AV3 by self-administered food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) reflective of the participant’s average diet intake over the previous three months. The WHI FFQ included 122 line-items, 19 adjustment questions and 4 summary questions. Line-items often included more than one food, such that data on more than 350 foods were collected. We used these data to calculate scores for adherence to the DASH and aMed diets and to calculate scores for the DII, as previously described (22,30–33).

Briefly, the DASH diet contains eight dietary components, measuring total cups or ounce equivalents of each listed food group: fruits, vegetables, nuts/legumes, whole grains, low-fat dairy, sodium, red/processed meat, and sweetened beverages. The DASH diet components were integer ranked (1 to 5), with cut-points based on corresponding quintiles, and then summed. DASH scores ranged from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating closer conformance to the modern interpretation of the diet.

The aMed diet has nine components, similarly measuring total cups or ounce equivalents of each listed food group: vegetables, fruits, nuts, whole grains, legumes, fish, monounsaturated and saturated fat, processed meats, and alcohol. The aMed diet components were scored dichotomously, with cut-points based on corresponding medians, and then summed. aMed scores ranged from 0 to 9, with a higher score indicating closer conformance to a Mediterranean diet pattern.

The dietary inflammation index (DII) was developed to assess the quality of diet with respect to its inflammation potential, based on prior literature evaluating foods and nutrients for their pro- and anti-inflammatory potential (33,34). DII scores are calculated from FFQ data. The DII incorporates consumption of foods known to increase inflammation (e.g., red meat, processed meat, organ meat, refined carbohydrates, and sweetened beverages) as well as those known to be anti-inflammatory (e.g., fruits and vegetables, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, fiber). Prior work has established the validity of the DII based on its association with inflammatory biomarkers among a sample of postmenopausal women (23). DII scores range from maximally anti-inflammatory to maximally pro-inflammatory (i.e., −7.25 to 6.03).

Each dietary scores was z-score standardized (i.e., total dietary score was subtracted from the mean dietary score and divided by respective standard deviation).

Quantification of Urinary Phthalate Metabolites

WHI followed a standard urine collection, processing, and storage protocol. First morning void urine samples were collected at home and processed <30 minutes upon clinic arrival. Urine samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1330 × g; 1.8mL aliquots were frozen and shipped to McKesson Bioservices packed in dry ice via overnight FedEx then stored at −70°C.

Urinary phthalate metabolites are used as biomarkers to ensure that measured concentrations relate to endogenous exposures. The Personal Care Products Laboratory at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quantified thirteen phthalate metabolites in urine samples provided at baseline and AV3 (mono-n-butyl phthalate [MBP], monobenzyl phthalate [MBzP], MCNP, mono-carboxyoctyl phthalate [MCOP], MCPP, mono(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate [MECPP], mono-(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate [MEHHP], mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate [MEHP], mono(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate [MEOHP], monoethyl phthalate [MEP], mono-hydroxybutyl phthalate [MHBP], mono-hydroxyisobutyl phthalate [MHiBP], and monoisobutyl phthalate [MiBP]), with limits of detection (LOD) ≤0.5 mg/mL. The glucuronidated phthalate metabolites undergo enzymatic deconjugation followed by on-line solid phase extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Samples were randomly distributed through the batches, with all replicates from cases and matched controls analyzed together. A blinded 10% quality control sample was included and used to estimate CVs: MBP 5.4%, MBzP 6.1%, MCNP 4.7%, MCOP 6.3%, MCPP 5.8%, MECPP 4.3%, MEHHP 5.4%, MEHP 19.5%, MEOHP 6.0%, MEP 3.1%, MHBP 9.0%, MHiBP 21.9%, MiBP 10.3%. Laboratory staff were masked to the identity, disease status, and demographic and risk factor characteristics of the samples. Creatinine was measured using a Roche Modular P Chemistry Analyzer (Indianapolis, IN) and an enzymatic assay. The limit of detection (LOD) for creatinine was 1 mg/dL and the CV was 2.5%.

Covariate Data

Participants provided extensive data via self-reported questionnaires and at annual clinic visits. We considered the following potential covariates assessed at baseline, with updates at subsequent clinic visits for time-varying covariates: creatinine (continuous), age (continuous), region (Northeast, South, West), education (less than high school, high school/some college, college graduate, graduate degree), income (<$35,000, ≥$35,000), current alcohol intake (non-drinker, past drinker, <1 drink per month, <1 drink per week, 1-<7 drinks per week, 7+ drinks per week), smoking status (never, past, current), body mass index (BMI) (continuous, kg/m2), measured during annual clinic visits, total physical activity METs/week (quartiles), dietary animal protein (continuous), dietary vegetable protein (continuous), and dietary energy (continuous, kcal). The dietary animal and vegetable protein variables are independent variables and were not utilized in calculating the dietary pattern scores.

Statistical Analysis

We imputed phthalate metabolite concentrations reported <LOD (<1% of observations) as the LOD/√2. Phthalate biomarker concentrations were natural log-transformed to improve normality. Phthalate biomarkers, measured between baseline and AV3, were analyzed as continuous variables. Sum of metabolites of di-n-butyl phthalate (ΣDBP), di-isobutyl phthalate (ΣDiBP), and di(2-Ethylhexyl) phthalate (ΣDEHP) were calculated as the molar sum of ΣDBP from MBP and MHBP; ΣDiBP from MiBP and MHiBP; ΣDEHP from MEHP, MEHHP, MEOHP, and MECPP. Dietary exposure data, DASH and aMed diet, and DII scores, measured at baseline and AV3, were analyzed continuously.

Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) models were fit using the identity link and Gaussian (normal) distribution to estimate cross-sectional associations between each dietary pattern and the phthalate biomarkers. This approach has the advantage of accommodating repeated measures, including updated covariate information at each time point. Initially, we fit a single GEE model for each phthalate biomarker, creatinine, age, and a single covariate.

In the multivariable GEE model development, all variables from the single predictor models, significant at the p<0.25 level, were included in our initial multiple predictors model. In subsequent model selection, age and creatinine were retained in all models, regardless of statistical significance. In selecting our final multivariable model, we utilized multiple criteria, including the significance of the partial F-tests (p<0.05) and changes in the magnitudes in the estimated regression coefficients (≥10%), this yielded the following covariates for inclusion in our final multivariable models: age, region, education level, alcohol consumption, dietary energy intake, and dietary animal protein. Note, given the high collinearity of race and region, we only adjusted for region in our analyses. Moreover, we adjusted models for BMI as a comparison analysis, given the association that exists with the dietary patterns. We report percent change in phthalate biomarkers per one standard deviation increase in total dietary score, calculated as the exponentiated beta subtracted from one and multiplied by 100 and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

All analyses were performed using Stata version 16.0 (Stata Corporation LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of the study population at baseline stratified by tertiles of the dietary pattern scores are presented in Table 1. Briefly, we observed that, compared to those in the third tertile, women in the first tertile of the DASH and aMed diet scores were younger (61 years, SD 6.6; 61 years, SD 6.8), more likely to be from the Northeast (193,40.4%; 206, 41.7%), and had a higher BMI (29.05 kg/m2, SD 6.1; 28.22 kg/m2, SD5.7). Conversely, compared to those in the third tertile, women in the first tertile of the DII score were older (63 years, SD 6.7), more likely to be from the West (178, 44.6%), and had a lower BMI (26.85 kg/m2, SD 5.0).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics, at baseline, of study group, stratified by tertiles of dietary pattern scores, N=1,240

| Characteristics1 | DASH Diet Score | aMed Diet Score | DII Diet Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| T:<=22 | T3:>=28 | P value | T1:<=3 | T3:>=9 | P value | T1:<=−3.49 | T3:>=4.54 | P value | |

|

| |||||||||

| Age; Mean (SD) | 61.17 (6.66) | 63.97 (6.92) | <0.001 | 61.81 (6.83) | 63.41 (6.95) | 0.007 | 63.89 (6.73) | 60.74 (6.78) | <0.001 |

| Region; N (%) | <0.001 | 0.141 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Northeast | 193 (40.4) | 125 (39.6) | 206 (41.7) | 94 (36.0) | 138 (34.6) | 181 (41.6) | |||

| South | 151 (31.6) | 59 (18.7) | 132 (26.7) | 60 (23.0) | 83 (20.8) | 132 (30.3) | |||

| West | 134 (28.0) | 132 (41.8) | 156 (31.6) | 107 (41.0) | 178 (44.6) | 122 (28.0) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2); Mean (SD) | 29.05 (6.11) | 27.34 (5.42) | <0.001 | 28.22 (5.70) | 27.74 (5.90) | 0.540 | 26.85 (5.05) | 29.55 (6.34) | <0.001 |

| Education status; N (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Less than high school degree | 178 (37.2) | 51 (16.1) | 175 (35.4) | 33 (12.6) | 80 (20.1) | 145 (33.3) | |||

| Post high school/some college | 185 (38.7) | 105 (33.2) | 188 (38.1) | 85 (32.6) | 140 (35.1) | 168 (38.6) | |||

| College degree or higher | 115 (24.1) | 160 (50.6) | 131 (26.5) | 143 (54.8) | 179 (44.9) | 122 (28.0) | |||

| Income; N (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Less than $34,999 | 257 (56.7) | 125 (41.7) | 260 (55.1) | 98 (40.2) | 149 (39.3) | 235 (56.5) | |||

| Greater than $35,000 | 196 (43.3) | 175 (58.3) | 212 (44.9) | 146 (59.8) | 230 (60.7) | 181 (43.5) | |||

| Alcohol intake, drinks/wk; N (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||||||

| 0 drinks/week | 184 (38.5) | 89 (28.2) | 179 (36.2) | 63 (24.1) | 111 (27.8) | 153 (35.2) | |||

| <1 drink/week | 176 (36.8) | 110 (34.8) | 195 (39.5) | 72 (27.6) | 132 (33.1) | 164 (37.7) | |||

| 1–6 drinks/week | 83 (17.4) | 90 (28.5) | 75 (15.2) | 101 (38.7) | 119 (29.8) | 77 (17.7) | |||

| 7+ drinks/week | 35 (7.3) | 27 (8.5) | 45 (9.1) | 25 (9.6) | 37 (9.3) | 41 (9.4) | |||

| Smoking status; N (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never Smoked | 271 (57.7) | 178 (56.7) | 278 (57.0) | 135 (52.5) | 225 (57.0) | 231 (53.8) | |||

| Past Smoker | 150 (31.9) | 131 (41.7) | 163 (33.4) | 116 (45.1) | 160 (40.5) | 154 (35.9) | |||

| Current Smoker | 49 (10.4) | 5 (1.6) | 47 (9.6) | 6 (2.3) | 10 (2.5) | 44 (10.3) | |||

| Total physical activity, MET-hr/wk, quartiles; N (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| <1.87 | 146 (35.9) | 48 (16.6) | 146 (34.2) | 38 (16.2) | 61 (16.4) | 135 (37.1) | |||

| >1.92–7.5 | 112 (27.5) | 62 (21.5) | 111 (26.0) | 60 (25.5) | 91 (24.4) | 101 (27.7) | |||

| >7.75–16.6 | 82 (20.1) | 74 (25.6) | 91 (21.3) | 51 (21.7) | 107 (28.7) | 62 (17.0) | |||

| >16.75 | 67 (16.5) | 105 (36.3) | 79 (18.5) | 86 (36.6) | 114 (30.6) | 66 (18.1) | |||

| Dietary Energy (kcal); Mean (SD) | 1656.58 (751.47) | 1687.12 (634.35) | 0.812 | 1434.34 (622.95) | 2018.49 (747.01) | <0.001 | 1419.60 (493.92) | 1910.78 (819.38) | <0.001 |

| Dietary Animal Protein (g); Mean (SD) | 49.04 (25.15) | 49.39 (26.31) | 0.975 | 42.25 (20.21) | 58.11 (28.35) | <0.001 | 41.61 (18.71) | 55.77 (29.02) | <0.001 |

| Dietary Vegetable Protein (g); Mean (SD) | 17.59 (7.92) | 24.87 (9.09) | <0.001 | 15.71 (7.04) | 28.13 (9.04) | <0.001 | 20.56 (8.54) | 20.43 (8.86) | 0.344 |

Abbreviations: MET, metabolic equivalent; DASH, Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension; aMed, Alternative Mediterranean Diet; DII, Dietary Inflammation Index; BMI, Body Mass Index

Missing data are as follows: BMI, n=8; income, n=65; smoking, n=15; physical activity n=145; dietary energy, n=1; dietary animal protein, n=1; dietary vegetable protein, n=1

Geometric mean concentrations of urinary phthalate biomarkers, adjusted for age, creatinine, and region, are presented in Table 2. In general, urinary phthalate biomarker concentrations were higher among women in the first tertile of the DASH and aMed diet scores and lower for women in the first tertile of the DII score and were statistically significant for MBzP, MCNP, MCOP, MCPP, MEP, and ΣDEHP.

Table 2.

Adjusted means of phthalate biomarkers, stratified by tertiles of dietary pattern scores, N=1,2401

| Phthalate Biomarker | DASH Diet Score | aMed Diet Score | DII Diet Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| 1st Tertile <=22 | 3rd Tertile >=28 | 1st Tertile <=3 | 3rd Tertile >=9 | 1st Tertile <=−3.49 | 3rd Tertile >=4.54 | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Geometric Mean (SD) | P-value | Geometric Mean (SD) | P-value | Geometric Mean (SD) | P-value | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| MBZP, ng/mL | 13.41 (2.93) | 8.83 (3.03) | 0.001 | 12.85 (2.98) | 9.49 (3.10) | <0.001 | 8.95 (2.89) | 14.61 (2.87) | <0.001 |

| MCNP, ng/mL | 2.96 (2.34) | 2.59 (2.79) | 0.56 | 2.91 (2.38) | 2.97 (2.87) | 0.02 | 2.67 (2.73) | 3.23 (2.33) | 0.93 |

| MCOP, ng/mL | 4.21 (2.45) | 3.28 (2.77) | 0.20 | 4.10 (2.52) | 3.52 (2.73) | 0.33 | 3.31 (2.58) | 4.58 (2.42) | 0.01 |

| MCPP, ng/mL | 3.42 (2.45) | 2.63 (2.55) | 0.16 | 3.40 (2.48) | 2.83 (2.56) | 0.05 | 2.73 (2.47) | 3.73 (2.40) | 0.17 |

| MEP, ng/mL | 97.00 (3.54) | 56.81 (3.35) | <0.001 | 86.71 (3.39) | 66.63 (3.43) | 0.05 | 71.48 (3.57) | 94.63 (3.55) | 0.86 |

| ΣDEHP, µmol/L | 0.21 (2.58) | 0.15 (2.61) | <0.001 | 0.20 (2.63) | 0.16 (2.69) | 0.004 | 0.15 (2.66) | 0.23 (2.52) | <0.001 |

| ΣDBP, µmol/L | 0.13 (3.00) | 0.09 (3.23) | 0.54 | 0.13 (2.96) | 0.11 (3.23) | 0.25 | 0.10 (3.02) | 0.15 (2.99) | 0.08 |

| ΣDiBP, µmol/L | 0.01 (2.83) | 0.01 (2.76) | 0.47 | 0.01 (2.75) | 0.01 (2.85) | 0.88 | 0.01 (2.84) | 0.02 (2.77) | 0.13 |

Abbreviations: DASH, Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension; aMed, Mediterranean Diet; DII, Dietary Inflammatory Index; MBzP, monobenzyl phthalate; MCNP, mono carboxyisononyl phthalate; MCOP, mono carboxyisooctyl phthalate; MCPP, mono-3-carboxypropyl phthalate; MEP, monoethyl phthalate; DEHP, di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate; DBP, di-n-butyl phthalate; DiBP, di-isobutyl phthalate

Geometric means estimated from regression models adjusted for age, creatinine, and region

Table 3 reports estimated multivariable-adjusted associations of DASH, aMed, and DII standardized scores with phthalate biomarkers. The DASH dietary score was significantly inversely associated with MBzP (−6.89%, 95% CI −10.59, −3.03), MCPP (−3.45%, 95% CI −6.60, −0.20), MEP (−7.56%, 95% CI −12.14, −2.73), and ΣDEHP (−6.48%, 95% CI −9.84, −3.00) concentrations. DASH dietary score was not significantly associated with MCOP, MCPP, ΣDBP, or ΣDiBP concentrations. Similarly, the aMed dietary score was inversely associated with MBzP (−8.71%, 95% CI −12.40, −4.87), MCPP (−3.99%, 95% CI −7.19, −0.67), ΣDEHP (−5.23%, 95% CI −8.73, −1.60), and ΣDBP (−4.16%, 95% CI −8.11, −0.03) concentrations. aMed dietary score was not associated with MCOP, MCPP, MEP, or ΣDiBP concentrations. DII scores were significantly positively associated with concentrations of MBzP (8.03%, 95% CI 3.77, 12.48), MCOP (3.77%, 95% CI 0.13, 7.56) ΣDEHP (8.83%, 95% CI 4.91, 12.89), ΣDBP (6.47%, 95% CI 2.18, 10.94) and ΣDiBP (4.46%, 95% CI 0.56, 8.52); no statistically significant associations were observed between DII score and MCNP, MCOP, MCPP, or MEP concentrations. Lastly, for comparison, we adjusted models for BMI, presented in supplemental Table, and saw a slight attenuation of the measure of association in all dietary patterns. However, the attenuation was minimal, and there was no change to the statistical significance.

Table 3.

Multivariable adjusted associations between standardized dietary scores and percent change in phthalate biomarkers, N=1,2401

| Phthalate Biomarker | DASH Diet Score2 | aMed Diet Score2 | Energy-adjusted DII Score2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % Change (95% CI) | P-value | % Change (95% CI) | P-value | % Change (95% CI) | P-value | |

|

| ||||||

| MBZP | −6.89 (−10.59, −3.03) | <0.001 | −8.71 (−12.40, −4.87) | <0.001 | 8.03 (3.77, 12.48) | <0.001 |

| MCPP | −3.45 (−6.60, −0.20) | 0.04 | −3.99 (−7.19, −0.67) | 0.02 | 2.40 (−0.95, 5.86) | 0.16 |

| MCNP | 0.66 (−2.90, 4.34) | 0.72 | 2.80 (−0.96, 6.70) | 0.15 | 1.21 (−2.42, 4.97) | 0.52 |

| MCOP | −2.13 (−5.53, 1.40) | 0.23 | −1.34 (−4.89, 2.33) | 0.47 | 3.77 (0.13, 7.56) | 0.04 |

| MEP | −7.56 (−12.14, −2.73) | <0.001 | −1.72 (−6.65, 3.47) | 0.51 | 1.56 (−3.43, 6.81) | 0.55 |

| ΣDEHP | −6.48 (−9.84, −3.00) | <0.001 | −5.23 (−8.73, −1.60) | 0.01 | 8.83 (4.91, 12.89) | <0.001 |

| ΣDBP | −3.75 (−7.64, 0.31) | 0.07 | −4.16 (−8.11, −0.03) | 0.05 | 6.47 (2.18, 10.94) | <0.001 |

| ΣDiBP | −2.29 (−6.00, 1.57) | 0.24 | −1.54 (−5.30, 2.37) | 0.43 | 4.46 (0.56, 8.52) | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: DASH, Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension; aMed, Alternate Mediterranean; DII, Dietary Inflammatory Index; MBzP, monobenzyl phthalate; MCNP, mono carboxyisononyl phthalate; MCOP, mono carboxyisooctyl phthalate; MCPP, mono-3-carboxypropyl phthalate; MEP, monoethyl phthalate; DEHP, di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate; DBP, di-n-butyl phthalate; DiBP, di-isobutyl phthalate

Adjusted for creatinine, age, region, education level, alcohol consumption, dietary energy, dietary animal protein

Total dietary scores were z-score standardized

Discussion

Among a large sample of postmenopausal women, we observed significantly lower urinary concentrations of MBzP, MCPP, MEP, ΣDBP, and ΣDEHP associated with higher alignment with the DASH and Mediterranean diets. Additionally, we also observed significantly higher concentrations of MBzP, ΣDEHP, ΣDBP, and ΣDiBP associated with higher DII scores, which are indicative of pro-inflammatory potential from dietary intake. No associations were observed between MCNP, MCOP, and the dietary pattern scores. Overall, consumption of better-quality diets was related to statistically significantly lower concentrations of phthalates, specifically those commonly used in food packaging material (e.g., DEHP and DBP).

Notably, higher consumption of whole fruits and vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and unsaturated fats, which result in higher aMed and DASH scores and lower DII scores, are also foods that are less likely to be processed or packaged in plastic. While foods that align with the modern interpretations of the DASH and Mediterranean diets may still be prepacked, phthalate contamination of those foods may be lower, given that the lipophilic characteristics of phthalates make the chemicals more likely to “stick” to foods high in fat (9,35). Recent studies reported that high-fat/processed foods, plastic-bottled beverages, and foods in plastic packaging contained the highest levels of DBP and DEHP (7,13,15). Prior studies have also reported greater phthalate exposure associated with higher intake of meat and meat products, milk and milk products, cheese, sweetened beverages, and refined carbohydrates (12,14,36–39). Urinary concentrations of DEHP metabolites and MCPP have been positively associated with consumption of fast food, food not prepared at home, processed and ultra-processed foods (14,16,38). These findings are consistent with our observed negative associations between higher alignment with the DASH and Mediterranean diets and urinary concentrations of ΣDBP and ΣDEHP, and positive associations between higher DII scores and urinary concentrations of ΣDBP and ΣDEHP.

Our findings must be interpreted within the context of the study’s limitations. Because dietary consumption was self-reported using FFQs, our study has the potential for non-differential exposure misclassification. However, prior work has established the validity of the FFQ in this population, which was highly correlated (r=0.89) with the gold standard (24-h recalls and food diaries) (40). Additionally, because phthalates have a short half-life, there is variability in the metabolites, which increases within-person variability of phthalate biomarker concentrations and would attenuate the results. Thus, the associations we observed could be underestimates. Additionally, there is a potential for type I error, given the large number of statistical comparisons performed. However, the general consistency of our findings across dietary indices and with prior literature supports the validity of our findings. Finally, we acknowledge that food packaging materials have changed over recent decades, due at least in part to consumer concerns over the dangers of the chemicals used to make them (e.g. bisphenol-A, phthalates). Thus, our results may be less relevant to current dietary exposures given that our data were collected up to 30 years ago and population exposure to the phthalates from which our measured metabolites were derived has decreased over time (41). Although our findings are compelling and suggest lower urinary phthalate concentrations with higher alignment to healthy dietary patterns (i.e., DASH and Mediterranean diet), our study is a cross-sectional study. Therefore, temporality and causality cannot be established, and results should be interpreted cautiously.

Our study is strengthened by the availability of a large, well-characterized sample of women. Also, we quantified a broad panel of phthalate metabolites in first-morning void urine samples using an established analytic method with proven reliability and validity. The repeated measures of phthalate biomarkers and evaluation of dietary patterns versus individual food groups are notable and a unique aspect of our study.

We observed that closer alignment with dietary patterns characterized by the consumption of whole vegetables and fruits, namely the DASH and Mediterranean diets, were associated with lower urinary concentrations of phthalate biomarkers. These findings highlight the need for careful consideration of the role of dietary patterns when examining potential associations between phthalate exposure and health outcomes. These findings suggest that dietary patterns high in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat foods and low in processed foods may be useful in avoiding exposure to phthalates. Consumers who are interested in avoiding exposure to phthalates may benefit from eating patterns that align with high DASH and Mediterranean diet scores and low DII scores.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Closer conformance with dietary patterns rich in whole fruits and vegetables, decrease concentrations of various phthalate biomarkers

Diets with high pro-inflammatory potential are associated with higher urinary phthalate biomarker concentrations

Dietary patterns may be more predictive of overall health status and future chronic disease risk than single food groups

Acknowledgements

Program Office:

(National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller

Clinical Coordinating Center:

(Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Garnet Anderson, Ross Prentice, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles Kooperberg

Investigators and Academic Centers:

(Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn E. Manson; (MedStar Health Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Cynthia A. Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Jennifer Robinson; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV) Robert Brunner

Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study:

(Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Mark Espeland

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES024731). The Women’s Health Initiative program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts 75N92021D00001, 75N92021D00002, 75N92021D00003, 75N92021D00004, 75N92021D00005.

Footnotes

Research Approval

Written informed consent was provided by participants upon WHI enrollment. Institutional review boards at each clinical site approved the WHI, and this particular analysis was approved by the University of Massachusetts Amherst IRB. The involvement of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) laboratory in the analysis of samples did not constitute engagement in human subjects research.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC, the Public Health Service, or the US Department of Health and Human Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Katherine Reeves & Gabriela Vieyra: Conceptualization and methodology

Gabriela Vieyra: Formal analysis, original draft preparation, and revisions

Katherine Reeves: Primary review and editing

Katherine Reeves: Supervision

Susan E. Hankinson, Youssef Oulhote, Laura Vandenberg, Lesley Tinker, JoAnn Mason, Aladdin H. Shadyab, Robert Wallace, Chrisa Arcan, JC Chen: Secondary reviewing and suggested editing

WHI Editors: Tertiary reviewing and suggested editing

Declaration of interests

☒ The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declaration of Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Song Y, Chou EL, Baecker A, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals, risk of type 2 diabetes, and diabetes-related metabolic traits: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes. 2016;8(4):516–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Zhu H, Kannan K. A Review of Biomonitoring of Phthalate Exposures. Toxics. 2019;7(2):E21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittassek M, Koch HM, Angerer J, et al. Assessing exposure to phthalates - the human biomonitoring approach. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55(1):7–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giuliani A, Zuccarini M, Cichelli A, et al. Critical Review on the Presence of Phthalates in Food and Evidence of Their Biological Impact. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):E5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fierens T, Servaes K, Van Holderbeke M, et al. Analysis of phthalates in food products and packaging materials sold on the Belgian market. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2012;50(7):2575–2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sioen I, Fierens T, Van Holderbeke M, et al. Phthalates dietary exposure and food sources for Belgian preschool children and adults. Environ Int. 2012;48:102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang J-F, Yang L-M, Zheng L-Y, et al. Phthalates in plastic bottled non-alcoholic beverages from China and estimated dietary exposure in adults. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B. 2017;10(1):44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakhi AK, Lillegaard ITL, Voorspoels S, et al. Concentrations of phthalates and bisphenol A in Norwegian foods and beverages and estimated dietary exposure in adults. Environ Int. 2014;73:259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fierens T, Servaes K, Van Holderbeke M, et al. Analysis of phthalates in food products and packaging materials sold on the Belgian market. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50(7):2575–2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carwile JL, Seshasayee SM, Ahrens KA, et al. Dietary correlates of urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations in 6–19 Year old children and adolescents. Environ Res. 2022;204(Pt B):112083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melough MM, Maffini MV, Otten JJ, et al. Diet quality and exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals among US adults. Environ Res. 2022;211:113049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serrano SE, Braun J, Trasande L, et al. Phthalates and diet: a review of the food monitoring and epidemiology data. Environ Health. 2014;13(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakhi AK, Lillegaard ITL, Voorspoels S, et al. Concentrations of phthalates and bisphenol A in Norwegian foods and beverages and estimated dietary exposure in adults. Environment International. 2014;73:259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zota AR, Phillips CA, Mitro SD. Recent Fast Food Consumption and Bisphenol A and Phthalates Exposures among the U.S. Population in NHANES, 2003–2010. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2016;124(10):1521–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudel Ruthann A, Gray Janet M, Engel Connie L, et al. Food Packaging and Bisphenol A and Bis(2-Ethyhexyl) Phthalate Exposure: Findings from a Dietary Intervention. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119(7):914–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckley JP, Kim H, Wong E, et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and exposure to phthalates and bisphenols in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2013–2014. Environment International. 2019;131:105057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez Steele E, Khandpur N, da Costa Louzada ML, et al. Association between dietary contribution of ultra-processed foods and urinary concentrations of phthalates and bisphenol in a nationally representative sample of the US population aged 6 years and older. PLoS One [electronic article]. 2020;15(7). (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7394369/). (Accessed March 3, 2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuhouser ML. The importance of healthy dietary patterns in chronic disease prevention. Nutrition Research. 2019;70:3–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moeller SM, Reedy J, Millen AE, et al. Dietary Patterns: Challenges and Opportunities in Dietary Patterns Research: An Experimental Biology Workshop, April 1, 2006. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107(7):1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ocké MC. Evaluation of methodologies for assessing the overall diet: dietary quality scores and dietary pattern analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2013;72(2):191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinberg D, Bennett GG, Svetkey L. The DASH Diet, 20 Years Later. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1529–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2599–2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabung FK, Steck SE, Zhang J, et al. Construct validation of the dietary inflammatory index among postmenopausal women. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(6):398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, et al. A population-based dietary inflammatory index predicts levels of C-reactive protein in the Seasonal Variation of Blood Cholesterol Study (SEASONS). Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(8):1825–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hébert JR, Shivappa N, Wirth MD, et al. Perspective: The Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII)-Lessons Learned, Improvements Made, and Future Directions. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(2):185–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shivappa N, Godos J, Hébert JR, et al. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Cardiovascular Risk and Mortality—A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2018;10(2):200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Lee DH, Hu J, et al. Dietary Inflammatory Potential and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among Men and Women in the U.S. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020;76(19):2181–2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Design of the Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trial and Observational Study. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1998;19(1):61–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reeves KW, Díaz Santana M, Manson JE, et al. Urinary Phthalate Biomarker Concentrations and Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(10):1059–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levitan EB, Lewis CE, Tinker LF, et al. Mediterranean and DASH diet scores and mortality in women with heart failure: The Women’s Health Initiative. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(6):1116–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fung TT, Rexrode KM, Mantzoros CS, et al. Mediterranean diet and incidence of and mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Circulation. 2009;119(8):1093–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabung FK, Steck SE, Zhang J, et al. Construct validation of the dietary inflammatory index among postmenopausal women. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(6):398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, et al. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(8):1689–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hébert JR, Shivappa N, Wirth MD, et al. Perspective: The Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII)—Lessons Learned, Improvements Made, and Future Directions. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(2):185–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giuliani A, Zuccarini M, Cichelli A, et al. Critical Review on the Presence of Phthalates in Food and Evidence of Their Biological Impact. Int J Environ Res Public Health [electronic article]. 2020;17(16). (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7460375/). (Accessed March 6, 2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong R, Zhou T, Zhao S, et al. Food consumption survey of Shanghai adults in 2012 and its associations with phthalate metabolites in urine. Environ Int. 2017;101:80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mervish N, McGovern KJ, Teitelbaum SL, et al. Dietary predictors of urinary environmental biomarkers in young girls, BCERP, 2004–7. Environ Res. 2014;133:12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varshavsky JR, Morello-Frosch R, Woodruff TJ, et al. Dietary sources of cumulative phthalates exposure among the U.S. general population in NHANES 2005–2014. Environ Int. 2018;115:417–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sathyanarayana S, Alcedo G, Saelens BE, et al. Unexpected results in a randomized dietary trial to reduce phthalate and bisphenol A exposures. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013;23(4):378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, et al. Measurement Characteristics of the Women’s Health Initiative Food Frequency Questionnaire. Annals of Epidemiology. 1999;9(3):178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fourth Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, Updated Tables, Jan 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/. 2019; [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.