Abstract

Introduction:

Patients with stage II germ-cell tumours (GCT) usually undergo radiotherapy (seminoma only) or chemotherapy. Both strategies display a recognised risk of long-term side effects. We evaluated retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) as exclusive treatment in stage II GCT.

Methods:

Between 2008 and 2019 included, 66 selected stage II GCT patients underwent primary open (O-) or laparoscopic (L-)RPLND. Type of procedure and extent of dissection, operative time, node rescue, hospital stay, complications (according to Clavien-Dindo), administration of chemotherapy, relapse and site of relapse were evaluated.

Results:

Five patients had pure testicular seminoma. Nineteen (28.8%) had raised markers prior to RPLND; 48 (72.7%), 16 (24.2%) and two (3.0%) were stage IIA, IIB and IIC, respectively. O-RPLND and unilateral L-RPLND were 36 and 30 respectively. Six stage II A patients (12.5%) had negative nodes. Four patients underwent immediate adjuvant chemotherapy. One patient was lost at follow-up. After a median follow-up of 29 months, 48 (77.4%) of the 62 patients undergoing RPLND alone remained recurrence-free; one patient had an in-field recurrence following a bilateral dissection. According to procedure, number of rescued nodes (O-RPLND: 25. IQR 21-31; L-RPLND: 20, IQR 15-26; p: 0.001), hospital stay (L-RPLND: 3 days, IQR 3-4; O-RPLND: 6 days, IQR 5-8; p: .001) and grade ≥2 complications (L-RPLND 7%, O-RPLND 22%; p: 0.1) were the only significant differences.

Conclusion:

Primary RPLND is safe in stage II GCT, including seminoma, and may warrant a cure rate greater than 70%. When feasible, L-RPLND may be as effective as O-RPLND with better tolerability.

Keywords: Germ-cell tumours, retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection, laparoscopy, chemotherapy, stage II

Introduction

In recent years, clinical and population data has focused on the long-term side effects of treatment. In stage I germ-cell tumours these efforts led to a modification of therapeutic strategies, aiming at avoiding or at least limiting these consequences in patients with a very favourable prognosis.1,2

Patients with only retroperitoneal metastases maintain a very favourable prognosis, and the vast majority of these men have a long survival.3,4 The long-term side effects of therapies expected in these patients are not fewer or less severe than in clinical stage I, but a balance between these risks and the probability of cure usually favoured the latter in the common practice. 5 Nonetheless, efforts in reducing burden of therapy in early clinical stage GCT are still limited.

In this matter the reduction of radiation therapy and chemotherapy may represent an endpoint only if the prognosis remains very good.

Retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection (RPLND) was largely in use for the treatment of stage II non seminomatous GCT (NSGCT) up to the beginning of the 2000s, and overall disease-specific survival did not differ according to the order of administration (RPLND followed by possible chemotherapy versus chemotherapy followed by possible RPLND). 6 The need for high surgical experience and a recommendation to referral centres, however, led to lower popularity of upfront RPLND. 7 On the other hand, indication of primary RPLND in stage II seminoma was discouraged due to a study reporting frequent abdominal recurrences and high morbidity. 8

Nowadays, both the awareness of long-term toxicity of chemotherapy and radiation therapy and the evolution of surgery, including the implementation of advanced laparoscopic and robotic platforms, renewed the interest in evaluating RPLND as primary treatment in early metastatic stage GCT.

In the present work, we analysed the most recent cases of stage II GCT patients who underwent upfront RPLND following a personalised pathway of care, in order to substantially evaluate efficacy of this strategy in a referral centre.

Patients and methods

From 2008 to 2019 included, 66 patients with stage II GCT underwent primary RPLND. All patients were staged with chest and abdominal CT scans with contrast medium and determination of alpha-fetoprotein, beta-unit of human chorionic gonadotropin and lactate dehydrogenase. The treatment was decided with each patient following thorough illustration of standard alternatives. Patients who opted for primary surgery expressed the desire to avoid primary chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

The choice concerning approach (open versus L-RPLND) depended on period, surgeon choice and, more importantly, on the presence of bilateral retroperitoneal disease. Extent of dissection has been previously described. 9

Complications were graded according to Clavien-Dindo classification. 10 Follow-up provided three-month checks for the first two years, checks with six–month intervals between the 3rd and 5th year and then yearly. Univariate statistics and Kaplan Meier survivals curves were performed using the R software environment for statistical computing and graphics (version 3.4.1).

This study was included and approved by Internal Review Board (INT 60/16)

Result

Table 1 reports the general characteristics of the patients. Briefly, five had primary seminoma (7.6%); 48 had stage IIA (72.7%) and six (16.7%) had bilateral disease in the retroperitoneum at pre-operative imaging; two patients had disease exceeding 5 cm; 36 underwent open dissection (33 bilateral) and 30 underwent laparoscopic (L-) ipsilateral RPLND; 19 (28.8%) patients had raised markers prior to RPLND. Table 2 reports the postoperative characteristics according to approach. Operative time was not statistically different between open- (median: 175 min; IQR 144.5-200) and L-RPLND (median: 185 min; IQR 153-218), while number of removed lymph-nodes was 25 (IQR 21-31) for open bilateral RPLND and 20 (IQR 15-26) for ipsilateral laparoscopic RPLND (p = 0.001). Hospital stay was shorter following L-RPLND (three days; IQR 3-4) than following open RPLND (six days; IQR 5-8) (p = 0.01). Complications included six Clavien-Dindo grade 2 and 4 grade 3A events, with a lower rate of grade ≥ 2 (7% vs 22.2%, p= 0.1) in L-RPLND cases. Overall, five lymph leaks (7.6%) were recorded with a median lymph leak time of seven days. Post-operative retrograde ejaculation occurred in seven patients (10.6%). According to unilateral or bilateral dissection, ante-grade ejaculation was maintained in 94% and 88% of patients, respectively. No lymphoedema was observed.

Table 1.

Preoperative descriptive characteristics.

| Laparoscopic (N=30) | Open (N=36) | Total (N=66) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.751 a | |||

| - Median (IQR) | 31.00 (26.00-36.00) | 29.00 (25.75- 40.25) | 30.00 (26.00- 38.00) | |

| ASA Score | 0.284 b | |||

| - I | 11 (42.3%) | 17 (56.7%) | 28 (50.0%) | |

| - II | 15 (57.7%) | 13 (43.3%) | 28 (50.0%) | |

| - Missing | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Clinical Stage | 0.148 b | |||

| - IIA | 25 (83.3%) | 23 (63.9%) | 48 (72.7%) | |

| - IIB | 5 (16.7%) | 11 (30.6%) | 16 (24.2%) | |

| - IIC | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.6%) | 2 (3.0%) | |

| Orchiectomy Histology | 0.405 b | |||

| - Teratoma | 2 (6.7%) | 7 (19.4%) | 9 (13.6%) | |

| - Non Seminoma/Mixed | 25 (83.3%) | 27 (75.0%) | 52 (78.8%) | |

| - Seminoma | 3 (10.0%) | 2 (5.6%) | 5 (7.6%) | |

| Preoperative markers | 0.047 a | |||

| - Negative | 25 (83.3%) | 22 (61.1%) | 47 (71.2%) | |

| - Positive | 5 (16.7%) | 14 (38.9%) | 19 (28.8%) |

N: number; IQR: interquartile range; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists classification.

Linear Model ANOVA (ANalysis Of VAriance).

Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

Table 2.

Postoperative characteristics.

| Laparoscopic (N=30) | Open (N=36) | Total (N=66) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up (months) | 0.300 a | |||

| - Median (IQR) | 15.50 (8.25-45.00) | 30.50 (16.50-44.00) | 29.00 (11.25-44.00) | |

| Surgery time (minutes) | 0.309 a | |||

| - Median (IQR) | 185.00 (153.00, 218.00) | 175.00 (144.50, 200.00) | 178.50 (147.75, 210.25) | |

| Surgical Template | < 0.001 b | |||

| - Bilateral | 0 (0.0%) | 33 (91.7%) | 33 (50.0%) | |

| - Unilateral | 30 (100.0%) | 3 (8.3%) | 33 (50.0%) | |

| Length of stay (days) | < 0.001 a | |||

| - Median (IQR) | 3.00 (3.00-4.00) | 6.00 (5.00-8.00) | 5.00 (4.00-7.00) | |

| Postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo classification) | 0.070 b | |||

| - 0 | 27 (93.1%) | 28 (77.8%) | 55 (84.6%) | |

| - II | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (16.7%) | 6 (9.2%) | |

| - IIIa | 2 (6.9%) | 2 (5.6%) | 4 (6.2%) | |

| Pathological stage | 0.109 b | |||

| - I | 5 (16.7%) | 1 (2.8%) | 6 (9.1%) | |

| - IIA | 16 (53.3%) | 17 (47.2%) | 33 (50.0%) | |

| - IIB | 8 (26.7%) | 13 (36.1%) | 21 (31.8%) | |

| - IIC | 1 (3.3%) | 5 (13.9%) | 6 (9.1%) | |

| Histology RPLND | 0.142 b | |||

| - Negative | 5 (16.7%) | 1 (2.8%) | 6 (9.1%) | |

| - Non Seminoma | 20 (66.7%) | 24 (66.7%) | 44 (66.7%) | |

| - Seminoma | 3 (10.0%) | 4 (11.1%) | 7 (10.6%) | |

| - Post-pubertal teratoma | 2 (6.7%) | 7 (19.4%) | 9 (13.6%) | |

| Number of nodes removed | 0.013 a | |||

| - Median (IQR) | 20.00 (15.00-26.00) | 24.50 (19.50-30.25) | 22.00 (17.00-28.00) | |

| Number of positive nodes | 0.156 a | |||

| - Median (IQR) | 2.00 (1.00-3.00) | 2.00 (1.00-4.00) | 2.00 (1.00-3.75) | |

| Lymph-node density | 0.5491 | |||

| - Median (IQR) | 7.42 (4.60-14.87) | 8.17 (6.25-13.93) | 7.85 (5.10-14.52) |

N: number; IQR: interquartile range; RPLND: Retroperitoneal Lymph-Node Dissection

Linear Model ANOVA (ANalysis Of VAriance).

Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

At definitive pathology, six (12.5%) clinical stage IIA patients had negative nodes (9.1% of the total), seven (10.6%) patients had pure seminoma and nine (13.6%) had post-pubertal teratoma only. Four (6.1%) patients underwent adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of two courses of Bleomycin, Etoposide and Cisplatin (BEP). Follow-up duration was of 30.5 months (IQR 16.5-44) after O-RPLND and 15.5 months (IQR 8.25-45) months after L-RPLND. One patient was lost to follow-up soon after intervention. After a median follow-up of 29 months (IQR 11.25-44), 14 of 61 (22.95%) recurrences occurred among patients who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy (14 of 55 or 25.5 % considering patients with actual metastatic nodes at RPLND). None of those undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy relapsed.

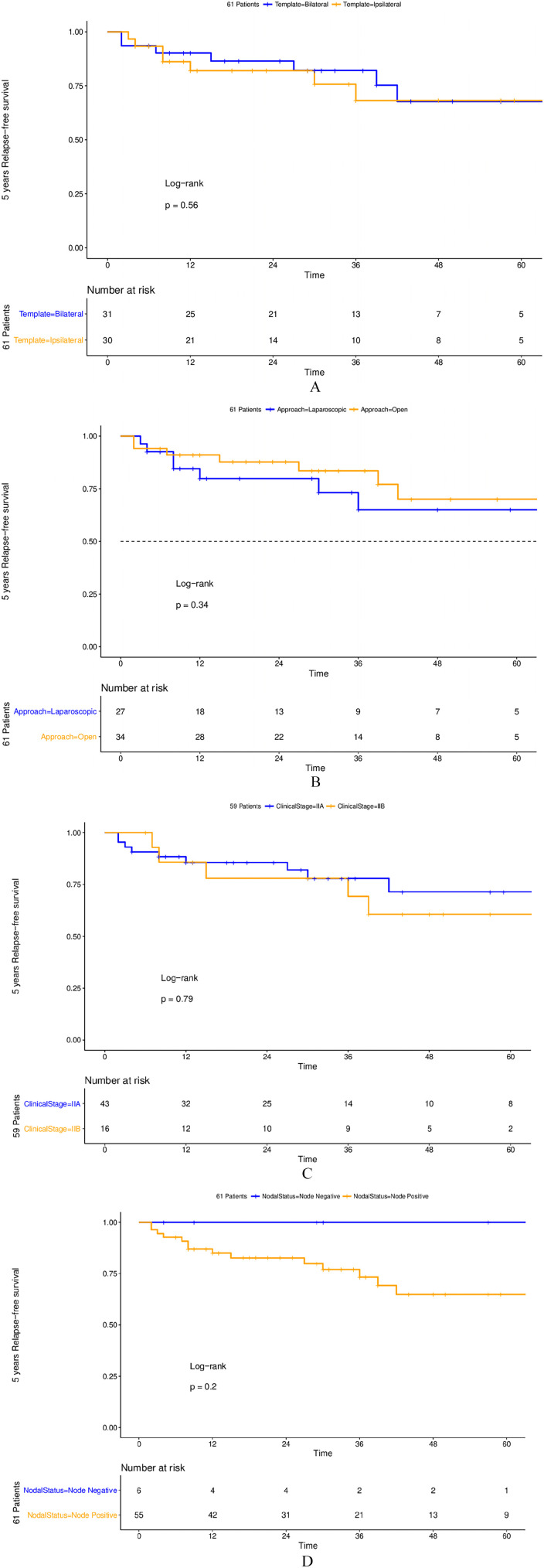

One patient developed contra-lateral stage I testicular germ-cell tumour after 18 months and underwent surveillance only with no recurrence. The online Supplementary Table 1 reports the sites of recurrence according to histology. Only one patient had an infield recurrence following bilateral dissection; other five patients had intra-abdominal recurrence with (2) or without (3) other non-abdominal metastases. Of note, none of those with pure seminoma or post-pubertal teratoma histology relapsed. After stratification according to surgical technique, no difference in relapse-rate was evident neither according to bilateral or unilateral dissection (22% [CI 10-41%] versus 27% [CI 12-46%], p=0.56) nor to open or laparoscopic dissection (29% [CI 12-50%] versus 20% [CI 9-38%] p=0.34). Also, no statistically significant difference was found among stage IIB (5/16 or 31.3%) and stage IIA (9/42 or 21.4%) (p=0.8) (Figure 1). Three of the five recurrences occurring after the second year consisted of post-pubertal teratoma only: all these late relapses were managed with surgery only. The two-year disease-free survival was 84.2%. In node positive patients, lower lymph node density was associated with higher relapse rates (Figure 2). Finally, of those with preoperative elevated tumour markers (19 patients) only one had adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of two courses of BEP and relapse occurred in five of 18 (27.7%). All relapsed patients were rescued with primary chemotherapy (three courses of BEP except one patient who had four courses) ± surgery (eight cases) or with surgery alone (six cases). All patients are currently alive and disease-free.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots depicting 5-year recurrence-free survival in 61 surgically-treated clinical stage II testicular cancer patients according to retroperitoneal lymph node dissection template (1A), technique (1B), nodal status (1C) and clinical stage (1D).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots depicting 5-year recurrence-free survival in 55 pathological stage II testicular cancer patients according to different cut-offs.

Discussion

The present series concerns patients undergoing primary RPLND following a selection process evaluated by experienced clinicians in this field. So far, our experience cannot represent a standardised reference for a large-scale indiscriminate adoption of primary RPLND in patients with stage II GCT of the testis. Nonetheless, this stands as a real-life report for a wider framework where non-chemo- and non-radiation therapy could be considered in early stage II GCTT, in order to limit the use of therapies with long-term toxicity. Both radiation and chemotherapy have documented raised risk of second cancer, which actually condition life expectancy.1,2 Chemotherapy is also associated with other side effects, including a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, and a relationship between cumulative cisplatin dose and overall morbidity has been documented. 11 Specifically, platinum-related hearing loss as to be considered because up to 18% of patients may experience severe to profound hearing loss.

Eventually, further benefits may be derived from primary surgery.

Surgery stands as the most accurate staging technique for small retroperitoneal nodes. Definitive pathology reported up to 40% of negative nodes among clinical stage IIA patients.12,13 A proportion of our patients with clinical stage II A (12.5%) do not actually have nodal metastases. These patients could be spared useless radio- or chemotherapy.

The majority of patients (77.4%) not undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy remained disease-free following a median follow-up of 29 months, corresponding to a 2-year disease-free survival of 84.2%. The proportion of those not receiving any form of chemotherapy reduces to 72.7% when we include those who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy.

The greatest benefit is evident in clinical stage IIA patients, where the proportion of relapses was the lower (see Figure 1), and where the role of primary RPLND could be maximised. 14

In previous experience, about 50% of stage II NSGCT patients received chemotherapy. 14 The greater proportion of patients who remain disease-free following RPLND only in our series may be a consequence of the limited use (6.1%) of immediate adjuvant chemotherapy, while Stephenson et al. reported a 32% rate of adjuvant chemotherapy. 14 The mid-term follow-up duration (29 months) in our series, leads us to suppose that further relapses could still occur. However, 60% of relapses occurring after the second year consisted of pure post-pubertal teratoma, the occurrence of which may be independent of chemotherapy administration and may require surgery.

The potential role of surgery in early metastatic seminoma is an emerging interest.

None of the seven patients with pure seminoma at definitive pathology relapsed after surgery.

Three trials are exploring the use of primary surgery in stage II seminoma.15-17 The German (PRIMETEST) 15 and the American (SEMS) 16 studies are evaluating the use of primary RPLND with different inclusion criteria and aim at reducing the use of chemotherapy. An English study evaluates mini-invasive RPLND plus one course of adjuvant carboplatin in all patients with proven metastases. 17 Preliminary results seem to support the hypothesis that surgery can be used with little risk and high efficacy in a disease context that has been subjected to ideological ostracism for many years, in order to prevent long-term side effects of full dose chemotherapy or radiation in patients who have a very favourable prognosis. Ideal definitive data should assess a very low rate of intra-abdominal recurrences.

Of growing interest is the role of limited template and mini-invasive RPLND in the management of metastatic GCT. Open dissections rescued more lymph-nodes than laparoscopic ones, but all open dissections, except three, were bilateral, while all L-RPLND were unilateral, thus with a smaller tissue removal. Nonetheless, recurrence rate did not differ between unilateral versus bilateral dissections or between open or laparoscopic dissections, while some benefits, such as reduced hospital-stay and a lower rate of complications were associated following L-RPLND. Small numbers and the selection process prevent us from considering the apparent equivalence in efficacy as conclusive. Nonetheless, such a finding compares with recent experiences supporting the adoption of limited template of dissection18,19 and the use of mini-invasive RPLND in the management of GCTT.9,20

Conclusions

The current study represents a “real life” contribution from a referral centre about the potential role of RPLND, even as MI-RPLND in select stage II non-seminomatous and seminomatous GCT. Upfront RPLND may be an alternative to radiation and chemotherapy, due to the growing interest in preventing long-term side effects of radiation therapy and chemotherapy in both histological GCT sub-types. More solid and long-term data are needed, which may derive from other and prospective experiences.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-tmj-10.1177_03008916221112697 for Retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection (RPLND) as upfront management in stage II germ-cell tumours: Evaluation of safety and efficacy by Nicola Nicolai, Sebastiano Nazzani, Antonio Tesone, Alberto Macchi, Luigi Piva, Roberto Salvioni, Silvia Stagni, Tullio Torelli, Edoardo Agostini, Francesco Celso, Patrizia Giannatempo, Giuseppe Procopio, Barbara Avuzzi, Rodolfo Lanocita, Laura Cattaneo, Mario Catanzaro and Davide Biasoni in Tumori Journal

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Sebastiano Nazzani  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5945-3248

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5945-3248

Giuseppe Procopio  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2498-402X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2498-402X

Barbara Avuzzi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7135-4506

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7135-4506

Davide Biasoni  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6552-2895

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6552-2895

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Fung C, Fossa SD, Milano MT, et al. Solid tumors after chemotherapy or surgery for testicular nonseminoma: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abouassaly R, Fossa SD, Giwercman A, et al. Sequelae of treatment in long-term survivors of testis cancer. Eur Urol 2011; 60: 516–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, et al. Guidelines on testicular cancer: 2015 update. European Association of Urology. Eur Urol 2015; 68: 1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCCN Clinical Practice Guideline in Oncology. Testicular Cancer, version 2019, https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/testicular.pdf. (accessed 20 December 2019).

- 5.Ghandour R, Ashbrook C, Freifeld Y, et al. Nationwide patterns of care for stage II nonseminomatous germ cell tumor of the testicle. Eur Urol Oncol 2020; 3(2): 198–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissbach L, Bussar-Maatz R, Flechtner H, et al. RPLND or primary chemotherapy in clinical stage IIA/B nonseminomatous germ cell tumors? Results of a prospective multicenter trial including quality of life assessment. Eur Urol 2000; 37: 582–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabakin AL, Shinder BM, Kim S, et al. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection as primary treatment for men with testicular seminoma: utilization and survival analysis using the national cancer data base, 2004-2014. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2020; 18(2): e194–e201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warszawski N, Schmücking M. Relapses in early-stage testicular seminoma: radiation therapy versus retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1997; 31: 355–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicolai N, Tarabelloni N, Gasperoni F, et al. Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis: safety and efficacy analyses at a high volume center. J Urol 2018; 199: 741–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerns SL, Fung C, Monahan PO, et al. Cumulative burden of morbidity among testicular cancer survivors after standard cisplatin-based chemotherapy: a multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 1505–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephenson AJ, Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ, et al. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer: impact of patient selection factors on outcome. J Clin Oncol 2005; 20: 2781–2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pizzocaro G, Nicolai N, Salvioni R, et al. Comparison between clinical and pathological staging in low stage nonseminomatous germ cell testicular tumors. J Urol 1992; 148: 76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephenson AJ, Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ, et al. Nonrandomized comparison of primary chemotherapy and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage IIA and IIB nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007; 10; 25(35): 5597–5602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lusch A, Gerbaulet L, Winter C, et al. Primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) in stage IIA/B seminoma patients without adjuvant treatment: a phase II trial (PRIMETEST). J Urol 2017; 197: e1044–e1045. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ClinicalTrials.gov. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in treating patients with testicular seminoma, national library of medicine. Bethesda, MD, USA. 2017. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCTNCT02537548 (accessed 20 December 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicol D, Huddart R, Reid A, et al. Minimally invasive retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (MI-RPLND) and single dose adjuvant carboplatin for low volume stage 2 seminoma – 3 year outcomes. 2020. Amsterdam: EAU Congress Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heidenreich A, Pfister D, Witthuhn R, et al. Post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in advanced testicular cancer: radical or modified template resection. Eur Urol 2009; 55: 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck SD, Foster RS, Bihrle R, et al. Is full bilateral retroperitoneal lymph node dissection always necessary for postchemotherapy residual tumor? Cancer 2007; 110: 1235–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolai N, Cattaneo F, Biasoni D, et al. Laparoscopic postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection can be a standard option in defined nonseminomatous germ cell tumor patients. J Endourol 2016; 30: 1112–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-tmj-10.1177_03008916221112697 for Retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection (RPLND) as upfront management in stage II germ-cell tumours: Evaluation of safety and efficacy by Nicola Nicolai, Sebastiano Nazzani, Antonio Tesone, Alberto Macchi, Luigi Piva, Roberto Salvioni, Silvia Stagni, Tullio Torelli, Edoardo Agostini, Francesco Celso, Patrizia Giannatempo, Giuseppe Procopio, Barbara Avuzzi, Rodolfo Lanocita, Laura Cattaneo, Mario Catanzaro and Davide Biasoni in Tumori Journal