Abstract

Background

The recovery-oriented service concept has been recognized for its impact on mental health practices and services. As the largest group of mental healthcare providers, mental health nurses are well-positioned to deliver recovery-oriented services but face challenges due to role ambiguity and identity issues. Therefore, clarifying the role and principles of mental health nursing is essential.

Objective

This study aimed to identify essential nursing practices for individuals with schizophrenia in recovery-oriented mental health services.

Design

The study utilized a five-step integrative review approach, including problem identification, literature search definition, critical analysis of methodological quality, data analysis, and data presentation.

Data Sources

Multiple databases, such as ScienceDirect and Scopus, as well as online libraries and journals/publishers, including Sage journals, APA PsyNet, SpringerLink, PsychiatryOnline, Taylor & Francis Online, and Wiley Online Library, were searched. The search spanned from the inception of the recovery-oriented services concept in 1993 to 2022.

Review Methods

Content and thematic analysis were employed to analyze and synthesize the findings from the included studies.

Results

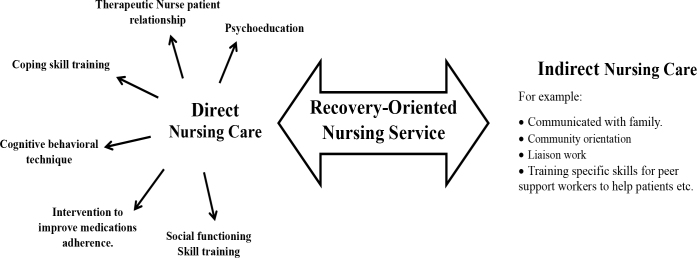

Twenty-four articles met the inclusion criteria. Two themes were identified: 1) Direct nursing care, consisting of six sub-themes: therapeutic nurse-patient relationship (TNPR), psychoeducation (PE), coping skill training (CST), cognitive behavioral techniques (CBT), interventions to improve medication adherence (IMA), and social functioning (SF); and 2) Indirect nursing care.

Conclusion

This study highlights the crucial role of nursing and nursing practices in recovery-oriented services. Mental health nurses prioritize person-centered care, therapeutic relationships, and collaboration with peer support workers to enhance treatment effectiveness. In addition, they focus on improving medication adherence, providing coping support, and promoting social capabilities, ultimately improving individuals’ quality of life. Aligning actions with recovery-oriented principles, mental health nurses emphasize empowerment and holistic care. Further research in this area will enhance the healthcare system and better support individuals on their recovery journey.

Keywords: schizophrenia, mental health services, mental disorders, recovery, quality of life, nurses

Background

Schizophrenia poses a significant global health concern and ranks among the world’s top ten diseases (Ayano, 2016). This condition profoundly impacts individuals’ physical, psychological, and social well-being, affecting the affected individuals and their families (Tasijawa et al., 2021). To provide mental health services for individuals with schizophrenia, recovery-oriented services have emerged as the most widely accepted framework (Slade, 2010). These services are founded on the principles of the personal recovery paradigm, which emphasizes the perspectives of individuals with mental illness and their active involvement in reclaiming a meaningful life and valued roles (Slade et al., 2014). Key elements of this paradigm include fostering hope, empowerment, choice, and self-determination. Recovery-oriented service approaches, therefore, prioritize mental health practices and services that center around the aspirations and needs of individuals with mental illness. Furthermore, they adopt a holistic approach and leverage individual strengths rather than solely focusing on managing psychotic symptoms and adhering to a biomedical view of mental illness (Frost et al., 2017).

The concept of recovery-oriented service has gained recognition for its development, delivery, and evaluation of mental health practices and services (Tondora et al., 2014). The principles and values underlying recovery-oriented service have predominantly been developed within outpatient and community mental health service settings (Compton et al., 2014). In this context, mental health nurses (MHNs) play a crucial role and are well-suited to provide recovery-oriented services due to their status as the largest group of mental healthcare providers globally. However, the implementation of recovery-oriented nursing services has encountered challenges, primarily due to the unclear autonomous role of MHNs. This lack of clarity impacts the identification of the mental health nursing role and service principles, leading to role overlap and diversification, making it difficult to establish a distinct MHNs identity (Hercelinskyj et al., 2014).

Empirical studies have focused on promoting the personal recovery journey of individuals with schizophrenia through the implementation of recovery-oriented services (Chester et al., 2016; Jackson-Blott et al., 2019) and primarily address the integration of recovery services within the mental health professional’s team, which includes mental health nurses (MHNs) (Badu et al., 2021). However, there is a lack of comprehensive review studies that synthesize qualitative and quantitative research specifically pertaining to recovery-oriented nursing services. The existing evidence aligns with the assertion that the autonomous role and services of MHNs remain unclear, and this lack of clarity in recovery-oriented nursing practice contributes to a gap between the ideal and actual implementation of nursing care (Le Boutillier et al., 2015). This situation has potential implications for individuals with schizophrenia, who require high-quality recovery-oriented nursing care for their long-term mental health needs. Consequently, it is essential to shed light on the nursing practices that promote the recovery of individuals with schizophrenia within the context of recovery-oriented services. Therefore, this review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of nursing practices within recovery-oriented mental health services for individuals with schizophrenia in the community. By examining and synthesizing the available literature, this review intends to contribute to the knowledge and promotion of effective nursing interventions that support the recovery process for individuals with schizophrenia.

Methods

In this study, the five-step integrative review methodology was employed due to its capacity to encompass diverse research approaches and perspectives, allowing for a comprehensive synthesis of knowledge and application of results relevant to the phenomenon under investigation. The five steps involved include 1) problem identification, 2) literature search definition, 3) critical analysis of the methodological quality of the included literature, 4) data analysis, and 5) data presentation (Hopia et al., 2016; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

Problem Identification

There is a lack of synthesized research on the current state of nursing practices implemented in recovery-oriented services for individuals with schizophrenia in community settings.

Literature Search Definition

A comprehensive integrative literature search was conducted across multiple databases, including ScienceDirect and Scopus, as well as online libraries and journals/publishers such as Sage journals, APA PsyNet, SpringerLink, PsychiatryOnline, Taylor & Francis Online, and Wiley Online Library. The search was conducted from the inception of the recovery-oriented services concept in 1993 until 2022.

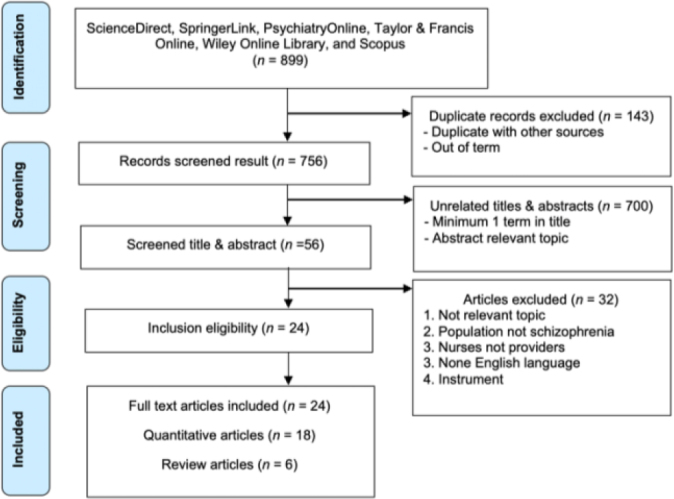

Initially, the search focused on the phenomenon of interest using terms such as “recovery-oriented,” “interventions,” and “Schizophrenia.” Subsequently, the search was refined to include title, abstract, and keywords to narrow down the results. Furthermore, the reference lists of all identified articles were reviewed for additional relevant studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The search process and outcomes are depicted in Figure 1, revealing that a total of twenty-four articles were selected. Further details of the search strategy can be found in the supplementary file.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selection of studies

The inclusion criteria for the retrieved articles were as follows: (1) focusing on schizophrenia, (2) involving nurses as care providers, (3) encompassing both quantitative and qualitative research articles, (4) involving adult and elderly populations, (5) examining practices and/or activities aimed at promoting personal recovery, (6) related to outpatient community services or rehabilitation services, and (7) written in English. Conversely, the exclusion criteria encompassed studies that (1) primarily focused on instruments related to psychotic properties, (2) pertained to forensic psychiatric areas, (3) focused on inpatient or sub-acute services, (4) addressed serious mental illnesses other than schizophrenia, and (5) did not involve nurses as mental healthcare providers implementing the services.

Critical Analysis of the Methodological Quality

The 16-item Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD) was selected to assess study quality. This tool is specifically designed to evaluate research across various methodologies (Sirriyeh et al., 2012). The scale utilizes a range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (complete), with two items specifically designated for qualitative research and two for quantitative studies. These criteria encompass considerations such as the theoretical framework, research question, and data collection methods. To ensure consistency, the two researchers involved in the study discussed and reached a consensus on the item scores. This iterative process resulted in each article being assigned a score across 14 items, facilitating the evaluation of individual articles and the integrated literature review.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using both content analysis (Grove et al., 2012; Vaismoradi et al., 2013) and thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The content analysis involved a thorough reading and familiarization with the recruited studies, followed by marking and labeling relevant content, analyzing the data, mapping all the identified content, and organizing it to describe the characteristics of the included articles. Thematic analysis was done by coding data from both quantitative and qualitative research, focusing on identifying themes related to nursing practices within each program outlined in each study. The identified themes were then used to create a thematic chart.

Data display matrices were also created to facilitate the documentation and synthesis of the coded data linked to recovery-oriented services and nursing practices. In addition, the research team thoroughly discussed and examined all codes. Notably, since each program did not explicitly specify which activities were performed by nurses, the researchers extracted nursing practices and activities by comparing and matching them with the expected roles and competencies of mental health nurses while considering activities carried out by other healthcare professionals.

Results

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The twenty-four selected studies included in this review were conducted in a total of eight countries: the USA (Canacott et al., 2019; Cook et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2012; Davidson & Guy, 2012; Fukui et al., 2011; Grant et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2012; Levitt et al., 2009; Macias et al., 1994; Mueser et al., 2002; Petros & Solomon, 2021; Repper & Carter, 2011; Salyers et al., 2014; Stanard, 1999), New Zealand (Canacott et al., 2019; Doughty et al., 2008; Repper & Carter, 2011), Ireland (Canacott et al., 2019; Higgins et al., 2012), United Kingdom (Bond & Drake, 2015; Canacott et al., 2019; Petros & Solomon, 2021; Slade et al., 2015; Slade et al., 2011), the Netherlands (van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012), Sweden (Färdig et al., 2011), Hong Kong (Lee et al., 2015; Mak et al., 2016) and Japan (Fujita et al., 2010).

Out of the twenty-four selected studies, nineteen were quantitative articles (Cook et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2012; Doughty et al., 2008; Färdig et al., 2011; Fujita et al., 2010; Fukui et al., 2011; Grant et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2012; Higgins et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2015; Levitt et al., 2009; Mak et al., 2016; Petros & Solomon, 2021; Salyers et al., 2014; Slade et al., 2015; Slade et al., 2011; Stanard, 1999; van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012), providing empirical data for analysis. Six studies were review articles (Bond & Drake, 2015; Canacott et al., 2019; Davidson & Guy, 2012; Macias et al., 1994; Mueser et al., 2002; Repper & Carter, 2011), offering a synthesis of existing research in the field.

Quality Assessment Results of the Included Articles

The quantitative articles received high scores with a QATADD percentage ranging from 83% to 97%, indicating alignment with the study’s goals regarding a research question, methodology, theoretical framework, reported standards, strengths, and limitations. The review articles had scores between 69% and 71%, indicating acceptable but insufficient proof of sample size and explanations for data selection. Overall, the included publications were of moderate to high quality and relevant to the research objectives (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quality assessment of each article using QATSDD

| Author(s) | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Score | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Grant et al., 2012) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | 40/42 | 95 |

| (Grant et al., 2017) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | 38/42 | 90 |

| (Färdig et al., 2011) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 35/42 | 83 |

| (Fujita et al., 2010) | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | 37/42 | 88 |

| (Levitt et al., 2009) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 1 | 35/42 | 83 |

| (Mueser et al., 2002) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | N/A | N/A | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 30/42 | 71 |

| (Salyers et al., 2014) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | 36/42 | 85 |

| (Lee et al., 2015) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | 39/42 | 92 |

| (Bond & Drake, 2015) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 29/42 | 69 |

| (Slade et al., 2011) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 1 | 36/42 | 85 |

| (Slade et al., 2015) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 1 | 35/42 | 83 |

| (Macias et al., 1994) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 1 | 36/42 | 85 |

| (Stanard, 1999) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 1 | 35/42 | 83 |

| (Doughty et al., 2008) | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | 37/42 | 88 |

| (Cook et al., 2009) | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | 37/42 | 88 |

| (Fukui et al., 2011) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 1 | 35/42 | 83 |

| (Higgins et al., 2012) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 43/48 | 89 |

| (Mak et al., 2016) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 1 | 36/42 | 85 |

| (Canacott et al., 2019) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 2 | 41/42 | 97 |

| (Petros & Solomon, 2021) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 29/42 | 69 |

| (Repper & Carter, 2011) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 29/42 | 69 |

| (Davidson & Guy, 2012) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 29/42 | 69 |

| (Cook et al., 2012) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 1 | 36/42 | 85 |

| (van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | N/A | 3 | 3 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 35/42 | 83 |

Note: A: Explicit theoretical framework; B: Aims of the study; C: Research setting description; D: Sample size considered in terms of analysis; E: Representative sample of the target group of a reasonable size; F: Data collection procedure description; G: Rationale for choosing data collection tool(s); H: Detailed recruitment data; I: Reliability and validity of measurement tool(s) (Quantitative study only); J: Fit between research question and data collection method (Quantitative study only); K: Fit between research question and format and content of data collection tool, e.g., interview schedule (Qualitative study only); L: Fit between research question and analysis method; M: Good justification for analytic method; N: Assessment of reliability of analytical process (Qualitative study only); O: Evidence of user involvement in design; P: Strengths and limitations critically discussed.

Content Analysis Results

Programs presented practices that promote personal recovery among people with schizophrenia

A comprehensive summary of the content analysis was conducted, highlighting the significance of the predominant content in each program regarding practices promoting personal recovery among individuals with schizophrenia in the community (see supplementary file). As a result, nine recovery-oriented programs were identified through both quantitative and review articles:

Recovery-oriented Cognitive Therapy (CT-R): Described in two articles (Grant et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2012), this program focuses on cognitive therapy techniques to facilitate recovery.

Illness Management and Recovery (IMR): Examined in five articles (Färdig et al., 2011; Fujita et al., 2010; Levitt et al., 2009; Mueser et al., 2002; Salyers et al., 2014), this program emphasizes the management of symptoms and the development of personal recovery strategies.

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT): Explored in two articles (Bond & Drake, 2015; Lee et al., 2015), ACT involves comprehensive and intensive community-based support to promote recovery.

REFOCUS intervention: Discussed in two articles (Slade et al., 2015; Slade et al., 2011), this intervention aims to enhance recovery through personalized care planning and goal setting.

The Strengths Model of Team Case Management (SMOTCM): Explored in two articles (Macias et al., 1994; Stanard, 1999), this model emphasizes the identification and utilization of an individual’s strengths to support recovery.

The Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP): Described in seven articles (Canacott et al., 2019; Cook et al., 2009; Doughty et al., 2008; Fukui et al., 2011; Higgins et al., 2012; Mak et al., 2016; Petros & Solomon, 2021), WRAP is a widely implemented program in Western countries, including the USA, Canada, the UK, Ireland, New Zealand, and Hong Kong. It involves individuals developing personalized plans for self-management and recovery.

Peer Support Workers service (PSW): Investigated in two articles (Davidson & Guy, 2012; Repper & Carter, 2011), this program involves peer support workers collaborating with mental health professionals to provide support, share coping strategies, and promote social functioning and community integration.

Building Recovery of Individual Dreams and Goals through Education and Support (BRIDGES): Cook et al. (2012) explore this program, which focuses on helping individuals identify and pursue their personal recovery goals.

Recovery is Up to You (peer-run course): As described in van Gestel-Timmermans et al. (2012), this program involves a peer-run approach where individuals actively participate in their recovery process.

These programs highlight various approaches and interventions to promote personal recovery in individuals with schizophrenia within community settings. In addition, it is evident that mental health nurses play a crucial role as part of the mental health professional teams in all recovery-oriented programs. Four of the programs, namely WRAP, PSW, BRIDGES, and the Recovery is Up to You (peer-run course) (Canacott et al., 2019; Cook et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2012; Davidson & Guy, 2012; Doughty et al., 2008; Fukui et al., 2011; Higgins et al., 2012; Mak et al., 2016; Petros & Solomon, 2021; Repper & Carter, 2011; van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012), involve collaboration between MHPs and peer support workers. Peer support workers are individuals who have personal experiences with mental illness and provide support to individuals with mental health problems. They undergo training or certification to perform their role effectively.

Furthermore, each program is implemented within the framework of community service models for mental health, which vary across different organizations and nations. These models encompass outpatient community mental health services, outpatient rehabilitation services, and residential and vocational rehabilitation services. Each program follows unique and specific procedures tailored to their respective program goals and settings.

Patient outcomes from recovery-oriented practices

Table 2 provides an analysis and summary of two significant types of patient outcomes observed in the included studies: 1) Objective Outcomes: These outcomes encompass improvements in functioning, reduction of psychiatric symptoms, and increased community connection (Bond & Drake, 2015; Färdig et al., 2011; Fujita et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2015; Levitt et al., 2009; Macias et al., 1994; Mueser et al., 2002; Salyers et al., 2014; Slade et al., 2015; Slade et al., 2011; Stanard, 1999); 2) Subjective Outcomes: These outcomes include enhancements in quality of life, self-efficacy, recovery, hope, self-advocacy, and empowerment (Canacott et al., 2019; Cook et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2012; Davidson & Guy, 2012; Doughty et al., 2008; Fukui et al., 2011; Higgins et al., 2012; Mak et al., 2016; Petros & Solomon, 2021; Repper & Carter, 2011; van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012).

Table 2.

Patient outcomes from recruited recovery-oriented practices

| Recovery-Oriented Program | Objective outcomes |

Subjective outcomes |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functioning | Psychiatric symptoms | Community connection | Quality of life | Self-efficacy | Recovery | Hope | Self-advocacy | Empowerment | ||

| By only mental health professionals | CT-R | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| IMR | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | - | |

| ACT | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | - | - | - | |

| REFOCUS | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | ↑ | ↑ | - | ↑ | |

| SMOTCM | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | - | - | - | |

| By mental health professional & peers | WRAP | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| PSW | - | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | ↑ | |

| BRIDGES | - | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | ↑ | - | - | - | |

| Recovery is up to you (peer-run course) | - | - | ↑ | - | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | ↑ | |

Note: CT-R: Recovery-oriented Cognitive Therapy; IMR: Illness Management and Recovery; ACT: Assertive Community Treatment; SMOTCM: Strengths Model of Team Case Management; WRAP: Wellness Recovery Action Plan; PSW: Peer Support Workers service; BRIDGES: Building Recovery of Individual Dreams and Goals through Education and Support

Notably, the analysis revealed a noteworthy finding: the subjective outcomes related to recovery-oriented practice were prominently associated with mental health professionals (MHPs) working in collaboration with peer support workers. This highlights the importance of the involvement of peer support workers in promoting subjective outcomes of recovery-oriented care rather than relying solely on the services provided by MHPs.

Results of Thematic Analysis

Direct and Indirect Nursing Care

Table 3 represents the findings of the thematic analysis conducted by the researchers. The analysis followed an inductive coding process, wherein each article was carefully examined line by line to identify practices relating to the role of mental health nursing in recovery-oriented services. The Psychiatric-Mental Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, established by the American Nurses Association (ANA) (2007), recognizes the principle of recovery, defined and experienced uniquely by each individual. Consequently, mental health nurses (MHNs) are required to engage with individuals with schizophrenia across different stages of recovery (Camann, 2010).

Table 3.

Themes and sub-themes identified from included articles

| Themes | Sub-themes | Example statements in line with mental health nursing practices and/or activities |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Nursing Care | 1) Therapeutic nurse-patient relationship-TNPR (All included articles) | “Making therapeutic relationship…” (Grant et al., 2012) “Encouraging to use self-help strategies to take responsibility take care of themselves…” (Canacott et al., 2019) |

| 2) Psychoeducation-PE (All included articles) | “Giving information…” (All included articles) “Psychoeducation involves recovery concept” (Doughty et al., 2008) |

|

| 3) Coping skill training-CST (Bond & Drake, 2015; Cook et al., 2012; Färdig et al., 2011; Fujita et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2015; Levitt et al., 2009; Mueser et al., 2002; Salyers et al., 2014; Slade et al., 2015; Slade et al., 2011; van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012) |

“Coping with stress, symptoms, problems…” (van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012) “Psychotic symptom management…” (Levitt et al., 2009) |

|

| 4) Cognitive-behavioral technique-CBT (Färdig et al., 2011; Fujita et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2012; Levitt et al., 2009; Mueser et al., 2002; Salyers et al., 2014) |

“Use Cognitive behavioral technique to reframe distorted belief by using several activities with…” (Färdig et al., 2011; Grant et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2012) “Cognitive behavioral adapting for treatment adherence” (Färdig et al., 2011) |

|

| 5) Intervention to improve medication adherence-IMA (All included studies) | “Coaching clients to create individual plans related to medication…) (Higgins et al., 2012) “Providing traditional treatments (medication)…” (Cook et al., 2012) |

|

| 6) Social functioning-SF (Bond & Drake, 2015; Cook et al., 2012; Färdig et al., 2011; Fujita et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2015; Levitt et al., 2009; Macias et al., 1994; Mueser et al., 2002; Salyers et al., 2014; Stanard, 1999; van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012) |

“Training social and functioning skills…” (Macias et al., 1994; Stanard, 1999; van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012) | |

| Indirect Nursing Care (Bond & Drake, 2015; Canacott et al., 2019; Cook et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2012; Davidson & Guy, 2012; Doughty et al., 2008; Fukui et al., 2011; Higgins et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2015; Mak et al., 2016; Petros & Solomon, 2021; Repper & Carter, 2011; van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012) |

“Training peer staff…” (Cook et al., 2012; Davidson & Guy, 2012; Repper & Carter, 2011; van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2012) “Cooperation work with community rehabilitation service” (Lee et al., 2015) |

|

Based on these principles, MHNs are involved in a range of activities, including assessing an individual’s position on the recovery continuum, providing psychotherapy, prescribing medication, offering clinical supervision and preventive care, and making referrals for health issues beyond the scope of nursing practice (American Nurses Association (ANA), 2007). These principles served as the basis for identifying and synthesizing nursing activities and practices within each program, distinguishing them from the activities performed by other healthcare professionals. The aim was to align these activities with the role and guiding principles of mental health nursing.

Through the thematic analysis, six regular practices/activities and other themes related to nursing care were identified: 1) therapeutic nurse-patient relationship (TNPR), 2) psychoeducation (PE), 3) coping skill training (CST), 4) cognitive behavioral techniques (CBT), 5) interventions to improve medication adherence (IMA), and 6) social functioning (SF). Additionally, some practices did not involve direct interaction with the patient, such as community orientation, liaison work, integration with community services, family communication for psychoeducation, budgeting assistance, training, and coordination of peer support workers.

These practices and activities were grouped and assigned codes under two overarching themes: “direct nursing care” and “indirect nursing care.” The extracted and synthesized data, along with the corresponding codes and their linkages to recovery-oriented services and nursing practices, were documented in Table 4 and Figure 2. It is worth noting that the identification of specific activities as nurses’ actions was not explicitly stated within each program. Hence, the researchers had to compare and match the activities with the role and responsibilities of nurses in mental health care to attribute them to nursing practices.

Table 4.

Mental health nursing practice derived from recovery-oriented programs in selected studies

| Recovery-Oriented Program | Nursing Practice in Line with The Mental Health Nursing Role and Competency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Nursing Care | Indirect Nursing Care | |||||||

| TNPR | PE | CST | CBT | IMA | SF | |||

| By only MHPs | CT-R | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| IMR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | |

| ACT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ Community orientation, liaison work, communication with family |

|

| REFOCUS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | |

| SMOTCM | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | |

| By MHPs & Peers | WRAP | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ Training specific skills for peer support workers and working with patients |

| PSW | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ||

| BRIDGES | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Recovery is up to you (peer-run course) | ✓ | ✓ Self-help educational approaches |

✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ||

Note: TNPR: Therapeutic Nurse-Patient Relationship; PE: Psychoeducation; CST: Coping Skill Training; IMA: Improve Medication Adherence; SF: Social Functioning

Figure 2.

Recovery-oriented nursing service model

Discussion

This integrative review aimed to analyze and synthesize the available evidence regarding nursing practices/services within recovery-oriented programs for individuals with schizophrenia. The findings of this review are organized and discussed based on two overarching themes: 1) Direct nursing care, which encompasses six sub-themes: therapeutic nurse-patient relationship (TNPR), psychoeducation (PE), coping skill training (CST), cognitive behavioral techniques (CBT), interventions to improve medication adherence (IMA), and social functioning (SF); and 2) Indirect nursing care.

Direct Nursing Care

Direct nursing care encompasses the direct provision of active care to patients, involving interactions, counseling, and socialization, which are considered direct roles in nursing (Kakushi & Évora, 2014). In essence, direct care roles refer to nursing practices that involve personal contact with patients (Abt et al., 2022; Butcher et al., 2018). As such, nurses in direct care practice play a crucial role in influencing the quality of care provided. They have numerous opportunities to implement various nursing practices aimed at promoting personal recovery within recovery-oriented services. In this review, we have identified six essential nursing practices within direct nursing care.

First, establishing therapeutic relationships is the cornerstone of nursing therapy for individuals with schizophrenia (Hewitt & Coffey, 2005). These relationships are crucial in supporting the recovery process, as any barriers to the therapeutic relationship can hinder recovery initiation (Harris & Panozzo, 2019). Difficulties in establishing trust or resistance to receiving therapy can impede progress. Therefore, the therapeutic relationship holds significant importance in terms of therapeutic techniques and in influencing the overall recovery of individuals with schizophrenia (Kvrgic et al., 2013). Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive impact of therapeutic relationships on personal recovery, further emphasizing their critical role (Cavelti et al., 2016; Kvrgic et al., 2013).

Second, psychoeducation plays a significant role in various therapeutic programs as it involves providing patients with essential information about their illness and treatment options and addressing relevant topics (Bäuml et al., 2006). This nursing practice is crucial for promoting recovery as it empowers patients with a fundamental understanding of mental illness and its necessary treatment. When individuals possess this knowledge, they are more likely to commit to their treatment plan and engage more effectively with specific therapeutic interventions. Psychoeducation enhances patients’ ability to actively participate in their own recovery journey, leading to improved outcomes and increased treatment adherence.

Third, coping skills training is rooted in Bandura’s social cognitive theory, which emphasizes the practice of new behaviors to enhance self-efficacy and promote positive outcomes (Heffernan, 1988). In the context of schizophrenia, developing effective coping skills is crucial for individuals’ recovery process. Research has consistently demonstrated that inadequate coping skills are associated with poorer recovery outcomes (Rossi et al., 2018). Individuals with schizophrenia who rely on maladaptive coping strategies often experience personal setbacks and increased distress (Xu et al., 2013). Therefore, providing appropriate coping skills training is essential to help individuals with schizophrenia develop adaptive strategies to navigate stressful situations and enhance their overall well-being. By equipping them with effective coping mechanisms, individuals can improve their ability to manage challenges, foster resilience, and promote their recovery journey.

Fourth, schizophrenia is frequently accompanied by significant cognitive impairments (O'Carroll, 2000). To address these impairments, various programs, such as cognitive remediation and brain stimulation techniques, have been developed (Vita et al., 2022). In this study, our focus was on cognitive and behavioral strategies, as they were consistently mentioned in the selected articles, and mental health nurses can play a practical role in implementing these strategies. Cognitive behavioral techniques have gained recognition and effectiveness in promoting personal recovery, as supported by systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Nowak et al., 2016). These techniques have positively affected functional outcomes, including improved quality of life, work, and social functioning. By incorporating cognitive and behavioral strategies into their practice, mental health nurses can contribute to enhancing the overall well-being and functional outcomes of individuals with schizophrenia.

Fifth, ensuring medication adherence in individuals with schizophrenia is of utmost importance due to the crucial role antipsychotic medication plays in treatment and symptom management. Nonadherence to medication can have adverse consequences, including an elevated risk of psychotic relapse, leading to decreased quality of life and increased hospitalization rates. These negative outcomes can impede recovery, causing delays or incomplete recovery (Kukla et al., 2013; Walby, 2007). Therefore, interventions to improve medication adherence are essential in promoting successful treatment outcomes and supporting the recovery of individuals with schizophrenia.

Sixth, social functioning skill training is an integral component of interventions for individuals with schizophrenia, aiming to enhance their ability to interact with others and live independently, thereby improving their community functioning (Kopelowicz et al., 2006). Social impairment is commonly experienced by individuals with schizophrenia, significantly affecting their quality of life and overall recovery process. Enhancing social functioning is closely associated with functional recovery. Various Cochrane reviews and studies have consistently demonstrated the effectiveness of social skills training in improving social skills and psychosocial functioning and reducing negative symptoms (Lyman et al., 2014). Therefore, incorporating social functioning skill training into recovery-oriented services can positively impact individuals with schizophrenia, promoting their social integration and overall well-being.

Indirect Nursing Care

Indirect nursing care plays a supportive role in enhancing the effectiveness of direct care treatments. These roles involve activities performed for the patients’ treatments without direct interaction or hands-on care (Kakushi & Évora, 2014). They are carried out when nurses provide assistance in settings other than directly with the patients or when patients are not actively involved (Abt et al., 2022; Butcher et al., 2018). For instance, within the ACT program, activities such as communicating with family members, facilitating community orientation, and liaising with community rehabilitation services are included (Bond & Drake, 2015; Lee et al., 2015). However, these activities cannot be grouped as they do not involve direct interaction with the client. Instead, they involve manipulating the environment or influencing factors surrounding the client to promote their personal recovery.

Existing evidence suggests that various factors contribute to promoting personal recovery among individuals with mental illness. For example, strong family support has been associated with a sense of being on the path to recovery, as it influences feelings of happiness and fulfillment in life (Chan et al., 2023; Kaewprom et al., 2011). Additionally, community attitudes toward mental health are crucial in helping individuals overcome stigma and regain control over their lives (Chan et al., 2018). Furthermore, employment is a key factor in promoting social inclusion, fostering a sense of identity and self-esteem, managing symptoms, reducing rehospitalization rates, and improving the overall quality of life (Luciano et al., 2014; Pai et al., 2021).

In the context of nursing practices, MHNs involved in programs such as ACT play a significant role in indirect care. They engage in activities like community orientation, collaboration with community rehabilitation services, and integrating services to support clients instead of referring them to other providers. It is worth noting that other practices within programs like WRAP, PSW, BRIDGES, and Recovery is Up to You (peer-run course) align with indirect care. In these cases, MHNs act as coaches, training individuals with lived experiences of mental illness to become peer support workers who can share their experiences and provide assistance to clients.

Numerous randomized control trials have provided evidence of the effectiveness of peer support workers in facilitating positive patient outcomes (Chinman et al., 2006; Shalaby & Agyapong, 2020). In addition, the utilization of peer support workers has demonstrated their effectiveness in promoting personal recovery (Gates & Akabas, 2007; Moran et al., 2013). While this practice falls under the realm of indirect care, it is crucial for nurses to recognize its significance. Peer support workers bring added value to the process of sustainable recovery. Therefore, MHNs should actively engage in proper nursing practices that consider effectively collaborating with peer workers to uphold and promote personal recovery among individuals with schizophrenia in the community. By embracing and leveraging the contribution of peer support workers, MHNs can enhance the overall recovery journey for their patients.

Limitations

Although a comprehensive and systematic search was conducted, there is always a risk of overlooking relevant items due to the diversity of search phrases and keywords. Additionally, limiting the inclusion of studies to only English articles may result in excluding relevant non-English publications. Finally, it is essential to note that no articles were found that explicitly outlined the specific procedures or programs in which MHNs are involved within recovery-oriented service programs in community organizations, despite each program acknowledging the role of nurses in providing treatment. Therefore, in order to explore the activities and practices that MHNs can undertake within these programs, it is necessary to broaden the scope of extraction and synthesis through content and thematic analysis methods. This approach will help uncover the specific roles and responsibilities of MHNs in supporting recovery-oriented services.

Implications to Nursing Practice

Based on the findings, it is crucial for mental health nursing policy initiatives to prioritize the acquisition of knowledge and advocate for the implementation of recovery-oriented nursing services through comprehensive training programs. In order to support the recovery process of individuals, mental health nurses should prioritize the integration of recovery-oriented nursing services within the mental health policy and the healthcare system. In clinical practice, there should be a focus on conducting interventional studies that aim to provide sustainable and practical solutions for the recovery journey and outcomes, with a particular emphasis on collaborating with peer support workers. It is recommended that future research on recovery should increasingly adopt mixed methods approaches to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. By doing so, a more holistic and well-rounded approach can be taken toward promoting and supporting recovery in individuals with mental health issues.

Conclusion

Despite the efforts of mental health nurses (MHNs) in supporting personal recovery, it is evident that their roles often overlap with those of other mental health nursing professionals (MNPs). Nevertheless, this discovery emphasizes the significant role of nursing and nursing practices in recovery-oriented services. Nursing practice in this context revolves around the MHNs’ understanding of person-centered care and active involvement in direct and indirect nursing care. MHNs play a crucial role in establishing therapeutic relationships with individuals, which is essential for effective treatment. They also contribute to improving medication adherence, providing coaching and support for coping skills, enhancing social capabilities, and coordinating with various support sources such as peer support workers. In addition, these nursing practices are instrumental in fostering hope, promoting community connections, and improving individuals’ overall quality of life. As the profession moves towards recovery-oriented principles, it is the responsibility of MHNs to ensure that their actions exemplify these principles. This entails aligning their practice with the core values of recovery, such as empowerment, self-determination, and holistic care. Further research and understanding of the implementation of recovery-oriented practices will contribute to continuous improvement in the healthcare system and the promotion of recovery for individuals with mental health issues.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, for the support.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest in this study.

Funding

None.

Authors’ Contributions

JT conceived the presented idea, conducted the literature search, and modified and designed the figures and table. JY helped shape the research and was in charge of overall direction and planning, verified the content analytical methods, encouraged JT to extract the data, contributed to interpreting the results, and supervised the findings of this work. PU encouraged JT and verified the analytical methods. JT wrote the manuscript with support and reviewed it from JY and PU. All authors provided critical feedback, discussed the results, and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors agreed with the article’s final version and were accountable for each part of this study.

Authors’ Biographies

Jutharat Thongsalab, Dip. APPMHN is a PhD student at the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Jintana Yunibhand, PhD, Dip. APPMHN is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Penpaktr Uthis, PhD, RN is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Data Availability

Data for content and thematic analysis can be seen in the supplementary file.

Ethical Consideration

This paper is part of the dissertation of Miss Jutharat Thongsalab, a PhD student in the Faculty of Nursing at Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, entitled “Factors predicting personal recovery among persons with schizophrenia living in community, Thailand.”

Declaration of Use of AI in Scientific Writing

Nothing to disclose.

References

- Abt, M., Lequin, P., Bobo, M. L., Vispo Cid Perrottet, T., Pasquier, J., & Ortoleva Bucher, C. (2022). The scope of nursing practice in a psychiatric unit: A time and motion study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 29(2), 297-306. 10.1111/jpm.12790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association (ANA) . (2007). Psychiatric-mental health nursing: Scope and standards of practice. Silver Spring, Maryland: American Nurses Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ayano, G. (2016). Schizophrenia: a concise overview of etiology, epidemiology diagnosis and management: Review of literatures. Journal of Schizophrenia Research, 3(2), 2-7. [Google Scholar]

- Badu, E., O’brien, A. P., & Mitchell, R. (2021). An integrative review of recovery services to improve the lives of adults living with severe mental illness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8873. 10.3390/ijerph18168873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäuml, J., Froböse, T., Kraemer, S., Rentrop, M., & Pitschel-Walz, G. (2006). Psychoeducation: A basic psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with schizophrenia and their families. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(suppl_1), S1-S9. 10.1093/schbul/sbl017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond, G. R., & Drake, R. E. (2015). The critical ingredients of assertive community treatment. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 240-242. 10.1002/wps.20234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, H. K., Bulechek, G. M., Dochterman, J. M., & Wagner, C. M. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC)-E-Book (7th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Camann, M. A. (2010). The psychiatric nurse's role in application of recovery and decision-making models to integrate health behaviors in the recovery process. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(8), 532-536. 10.3109/01612841003687316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canacott, L., Moghaddam, N., & Tickle, A. (2019). Is the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) efficacious for improving personal and clinical recovery outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42(4), 372-381. 10.1037/prj0000368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavelti, M., Homan, P., & Vauth, R. (2016). The impact of thought disorder on therapeutic alliance and personal recovery in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: An exploratory study. Psychiatry Research, 239, 92-98. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. K. S., Yip, C. C. H., & Tsui, J. K. C. (2023). Self-compassion mediates the impact of family support on clinical and personal recovery among people with mental illness. Mindfulness, 14(3), 720-731. 10.1007/s12671-023-02088-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, R. C. H., Mak, W. W. S., & Lam, M. Y. Y. (2018). Self-stigma and empowerment as mediating mechanisms between ingroup perceptions and recovery among people with mental illness. Stigma and Health, 3(3), 283-293. 10.1037/sah0000100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chester, P., Ehrlich, C., Warburton, L., Baker, D., Kendall, E., & Crompton, D. (2016). What is the work of recovery oriented practice? A systematic literature review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(4), 270-285. 10.1111/inm.12241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinman, M., Young, A. S., Hassell, J., & Davidson, L. (2006). Toward the implementation of mental health consumer provider services. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 33(2), 176-195. 10.1007/s11414-006-9009-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton, M. T., Reed, T., Broussard, B., Powell, I., Thomas, G. V., Moore, A., Cito, K., & Haynes, N. (2014). Development, implementation, and preliminary evaluation of a recovery-based curriculum for community navigation specialists working with individuals with serious mental illnesses and repeated hospitalizations. Community Mental Health Journal, 50, 383-387. 10.1007/s10597-013-9598-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J. A., Copeland, M. E., Hamilton, M. M., Jonikas, J. A., Razzano, L. A., Floyd, C. B., Hudson, W. B., Macfarlane, R. T., & Grey, D. D. (2009). Initial outcomes of a mental illness self-management program based on wellness recovery action planning. Psychiatric Services, 60(2), 246-249. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.2.246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J. A., Steigman, P., Pickett, S., Diehl, S., Fox, A., Shipley, P., MacFarlane, R., Grey, D. D., & Burke-Miller, J. K. (2012). Randomized controlled trial of peer-led recovery education using Building Recovery of Individual Dreams and Goals through Education and Support (BRIDGES). Schizophrenia Research, 136(1), 36-42. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, L., & Guy, K. (2012). Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: A review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry, 11(2), 123-128. 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty, C., Tse, S., Duncan, N., & McIntyre, L. (2008). The wellness recovery action plan (WRAP): Workshop evaluation. Australasian Psychiatry, 16(6), 450-456. 10.1080/10398560802043705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Färdig, R., Lewander, T., Melin, L., Folke, F., & Fredriksson, A. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of the illness management and recovery program for persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 62(6), 606-612. 10.1176/ps.62.6.pss6206_0606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost, B. G., Tirupati, S., Johnston, S., Turrell, M., Lewin, T. J., Sly, K. A., & Conrad, A. M. (2017). An Integrated Recovery-oriented Model (IRM) for mental health services: Evolution and challenges. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 1-17. 10.1186/s12888-016-1164-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, E., Kato, D., Kuno, E., Suzuki, Y., Uchiyama, S., Watanabe, A., Uehara, K., Yoshimi, A., & Hirayasu, Y. (2010). Implementing the illness management and recovery program in Japan. Psychiatric Services, 61(11), 1157-1161. 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, S., Starnino, V. R., Susana, M., Davidson, L. J., Cook, K., Rapp, C. A., & Gowdy, E. A. (2011). Effect of Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) participation on psychiatric symptoms, sense of hope, and recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 34(3), 214-222. 10.2975/34.3.2011.214.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates, L. B., & Akabas, S. H. (2007). Developing strategies to integrate peer providers into the staff of mental health agencies. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34, 293-306. 10.1007/s10488-006-0109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, P. M., Bredemeier, K., & Beck, A. T. (2017). Six-month follow-up of recovery-oriented cognitive therapy for low-functioning individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 68(10), 997-1002. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, P. M., Huh, G. A., Perivoliotis, D., Stolar, N. M., & Beck, A. T. (2012). Randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of cognitive therapy for low-functioning patients with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(2), 121-127. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove, S. K., Burns, N., & Gray, J. (2012). The practice of nursing research: Appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence (7th ed.). St.Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, B., & Panozzo, G. (2019). Barriers to recovery‐focused care within therapeutic relationships in nursing: Attitudes and perceptions. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(5), 1220-1227. 10.1111/inm.12611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, C. J. (1988). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory, Albert Bandura Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1986, xiii+ 617 pp. Hardback. US $39.50. Behaviour Change, 5(1), 37-38. 10.1017/S0813483900008238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hercelinskyj, G., Cruickshank, M., Brown, P., & Phillips, B. (2014). Perceptions from the front line: Professional identity in mental health nursing. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(1), 24-32. 10.1111/inm.12001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, J., & Coffey, M. (2005). Therapeutic working relationships with people with schizophrenia: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 561-570. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03623.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, A., Callaghan, P., DeVries, J., Keogh, B., Morrissey, J., Nash, M., Ryan, D., Gijbels, H., & Carter, T. (2012). Evaluation of mental health recovery and Wellness Recovery Action Planning education in Ireland: A mixed methods pre–postevaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(11), 2418-2428. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05937.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopia, H., Latvala, E., & Liimatainen, L. (2016). Reviewing the methodology of an integrative review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30(4), 662-669. 10.1111/scs.12327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Blott, K., Hare, D., Davies, B., & Morgan, S. (2019). Recovery-oriented training programmes for mental health professionals: A narrative literature review. Mental Health & Prevention, 13, 113-127. 10.1016/j.mhp.2019.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaewprom, C., Curtis, J., & Deane, F. P. (2011). Factors involved in recovery from schizophrenia: A qualitative study of Thai mental health nurses. Nursing & Health Sciences, 13(3), 323-327. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakushi, L. E., & Évora, Y. D. M. (2014). Direct and indirect nursing care time in an intensive care unit. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 22, 150-157. 10.1590/0104-1169.3032.2381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowicz, A., Liberman, R. P., & Zarate, R. (2006). Recent advances in social skills training for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(suppl_1), S12-S23. 10.1093/schbul/sbl023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukla, M., Salyers, M. P., & Lysaker, P. H. (2013). Levels of patient activation among adults with schizophrenia: Associations with hope, symptoms, medication adherence, and recovery attitudes. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(4), 339-344. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318288e253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvrgic, S., Cavelti, M., Beck, E.-M., Rüsch, N., & Vauth, R. (2013). Therapeutic alliance in schizophrenia: The role of recovery orientation, self-stigma, and insight. Psychiatry Research, 209(1), 15-20. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Boutillier, C., Chevalier, A., Lawrence, V., Leamy, M., Bird, V. J., Macpherson, R., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2015). Staff understanding of recovery-orientated mental health practice: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Implementation Science, 10, 1-14. 10.1186/s13012-015-0275-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. C., Liem, S. K., Leung, J., Young, V., Wu, K., Kenny, K. K. W., Yuen, S. K., Lee, W. F., Leung, T., & Shum, M. (2015). From deinstitutionalization to recovery-oriented assertive community treatment in Hong Kong: What we have achieved. Psychiatry Research, 228(3), 243-250. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, A. J., Mueser, K. T., DeGenova, J., Lorenzo, J., Bradford-Watt, D., Barbosa, A., Karlin, M., & Chernick, M. (2009). Randomized controlled trial of illness management and recovery in multiple-unit supportive housing. Psychiatric Services, 60(12), 1629-1636. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.12.1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, A., Bond, G. R., & Drake, R. E. (2014). Does employment alter the course and outcome of schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses? A systematic review of longitudinal research. Schizophrenia Research, 159(2-3), 312-321. 10.1016/j.schres.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman, D. R., Kurtz, M. M., Farkas, M., George, P., Dougherty, R. H., Daniels, A. S., Ghose, S. S., & Delphin-Rittmon, M. E. (2014). Skill building: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 65(6), 727-738. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias, C., Kinney, R., Farley, O. W., Jackson, R., & Vos, B. (1994). The role of case management within a community support system: partnership with psychosocial rehabilitation. Community Mental Health Journal, 30, 323-339. 10.1007/BF02207486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak, W. W. S., Chan, R. C. H., Pang, I. H. Y., Chung, N. Y. L., Yau, S. S. W., & Tang, J. P. S. (2016). Effectiveness of wellness recovery action planning (WRAP) for Chinese in Hong Kong. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 19(3), 235-251. 10.1080/15487768.2016.1197859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, G. S., Russinova, Z., Gidugu, V., & Gagne, C. (2013). Challenges experienced by paid peer providers in mental health recovery: A qualitative study. Community Mental Health Journal, 49, 281-291. 10.1007/s10597-012-9541-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser, K. T., Corrigan, P. W., Hilton, D. W., Tanzman, B., Schaub, A., Gingerich, S., Essock, S. M., Tarrier, N., Morey, B., & Vogel-Scibilia, S. (2002). Illness management and recovery: A review of the research. Psychiatric Services, 53(10), 1272-1284. 10.1176/appi.ps.53.10.1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, I., Sabariego, C., Świtaj, P., & Anczewska, M. (2016). Disability and recovery in schizophrenia: A systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy interventions. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 1-15. 10.1186/s12888-016-0912-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Carroll, R. (2000). Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 6(3), 161-168. 10.1192/apt.6.3.161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pai, N., Dark, F., & Castle, D. (2021). The importance of employment for recovery in people with severe mental illness. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 8, 217–219. 10.1007/s40737-021-00245-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros, R., & Solomon, P. (2021). How adults with serious mental illness learn and use wellness recovery action plan’s recovery framework. Qualitative Health Research, 31(4), 631-642. 10.1177/1049732320975729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repper, J., & Carter, T. (2011). A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 20(4), 392-411. 10.3109/09638237.2011.583947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A., Amore, M., Galderisi, S., Rocca, P., Bertolino, A., Aguglia, E., Amodeo, G., Bellomo, A., Bucci, P., & Buzzanca, A. (2018). The complex relationship between self-reported ‘personal recovery’and clinical recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 192, 108-112. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyers, M. P., McGuire, A. B., Kukla, M., Fukui, S., Lysaker, P. H., & Mueser, K. T. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of illness management and recovery with an active control group. Psychiatric Services, 65(8), 1005-1011. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby, R. A. H., & Agyapong, V. I. O. (2020). Peer support in mental health: Literature review. JMIR Mental Health, 7(6), e15572. 10.2196/15572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirriyeh, R., Lawton, R., Gardner, P., & Armitage, G. (2012). Reviewing studies with diverse designs: The development and evaluation of a new tool. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(4), 746-752. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M. (2010). Mental illness and well-being: The central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Services Research, 10(1), 1-14. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M., Amering, M., Farkas, M., Hamilton, B., O'Hagan, M., Panther, G., Perkins, R., Shepherd, G., Tse, S., & Whitley, R. (2014). Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery‐oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 12-20. 10.1002/wps.20084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M., Bird, V., Clarke, E., Le Boutillier, C., McCrone, P., Macpherson, R., Pesola, F., Wallace, G., Williams, J., & Leamy, M. (2015). Supporting recovery in patients with psychosis through care by community-based adult mental health teams (REFOCUS): A multisite, cluster, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(6), 503-514. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00086-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., McCrone, P., & Leamy, M. (2011). REFOCUS Trial: protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial of a pro-recovery intervention within community based mental health teams. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), 1-13. 10.1186/1471-244X-11-185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanard, R. P. (1999). The effect of training in a strengths model of case management on client outcomes in a community mental health center. Community Mental Health Journal, 35, 169-179. 10.1023/A:1018724831815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasijawa, F. A., Suryani, S., Sutini, T., & Maelissa, S. R. (2021). Recovery from ‘schizophrenia’: Perspectives of mental health nurses in the Eastern island of Indonesia. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(4), 336-345. 10.33546/bnj.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tondora, J., Miller, R., Slade, M., & Davidson, L. (2014). Partnering for recovery in mental health: A practical guide to person-centered planning. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gestel-Timmermans, H., Brouwers, E. P. M., van Assen, M. A. L. M., & van Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2012). Effects of a peer-run course on recovery from serious mental illness: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatric Services, 63(1), 54-60. 10.1176/appi.ps.201000450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vita, A., Gaebel, W., Mucci, A., Sachs, G., Barlati, S., Giordano, G. M., Nibbio, G., Nordentoft, M., Wykes, T., & Galderisi, S. (2022). European Psychiatric Association guidance on treatment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. European Psychiatry, 65(1), e57. 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.2315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walby, G. W. (2007). Associations between individual, social, and service factors, recovery expectations and recovery strategies for individuals with mental illness [Dissertation, University of South Florida; ]. Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546-553. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.-Y., Zu, S., Xiang, Y.-T., Wang, N., Guo, Z.-H., Kilbourne, A. M., Brabban, A., Kingdon, D., & Li, Z.-J. (2013). Associations of self-esteem, dysfunctional beliefs and coping style with depression in patients with schizophrenia: A preliminary survey. Psychiatry Research, 209(3), 340-345. 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data for content and thematic analysis can be seen in the supplementary file.