Abstract

We compared emotional valence scores as determined via machine learning approaches to human-coded scores of direct messages on Twitter from our 2,301 followers during a Twitter-based clinical trial screening for Hispanic and African American family caregivers of persons with dementia. We manually assigned emotional valence scores to 249 randomly selected direct Twitter messages from our followers (N=2,301), then we applied three machine learning sentiment analysis algorithms to extract emotional valence scores for each message and compared their mean scores to the human coding results. The aggregated mean emotional scores from the natural language processing were slightly positive, while the mean score from human coding as a gold standard was negative. Clusters of strongly negative sentiments were observed in followers’ responses to being found non-eligible for the study, indicating a significant need for alternative strategies to provide similar research opportunities to non-eligible family caregivers.

Keywords: machine learning, dementia caregiving, health disparity

1. Introduction

The prevalence of dementia is higher for African Americans than White Americans [1]. Emotional valence represents one’s subjective and affective reaction to a positive or negative situation. While pleasure, gladness or being content map to a positive emotional valence score, anger and frustration map to a negative emotional valence score [2].

In our previous study, we found that lexicon-based machine learning algorithms for text sentiment analysis detected fewer negative-valence observations compared to those from human coding (Afinn, Bing) and miscategorized neutral emotional status as positive status (Syuzhet) or negative status as neutral status (Bing) in the context of discussions of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease [3]. Unfortunately, the prior work was limited to using a corpus of Korean-language Tweets translated to English. Although sentiment analysis has been adopted to assess emotional valence from social media data, this method has only recently been adopted in health research [3]. Thus, diligent efforts to validate and refine the use of such algorithms in various health domains are needed.

The purpose of this study was to compare emotional valence scores of direct messages on Twitter from our 2,301 followers during the screening process of a Twitter-based clinical trial for Hispanic and African American dementia family caregivers as determined via machine learning approaches (Afinn, Bing, Syuzhet [2]) to human-coded scores. This study will inform which machine learning approaches will be used in dementia caregiving research and our future recruitment strategies.

2. Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). We applied manual scoring and machine learning-based sentiment analysis to calculate emotional valence scores from 249 randomly selected direct Twitter messages from our followers (N=2,301) during the screening period for the clinical trial NCT03865498 (01/12/2022 – 12/10/2022). This study was to answer the question: “What are the differences in sentiment scores detected by algorithms and human coding?” We hypothesized no difference in emotional valence calculated by algorithms and humans. First, three independent researchers with dementia caregiving or data science expertise manually assigned an emotional valence score to the 249 randomly selected direct Twitter messages from our followers on a scale from −10 [worst] to +10 [best], with 0 being neutral emotional valence. Inter-rater reliability after two rounds of the consensus process were calculated on all messages (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient: 0.673, 95% CI [0.615, 0.725]) using the irr package in R. Second, we used natural language processing (NLP) to clean (e.g., remove symbols) and preprocess (e.g., remove stop words, apply stemming) the text of the Twitter direct messages and ran machine learning sentiment analysis (Afinn, Syuzhet, Bing) to extract an emotional valence score for each of the Twitter direct messages using the R programming language [2]. Third, we compared the aggregated mean emotional valence scores from human coding to those produced by the three machine learning sentiment analysis packages, using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by visual checking of the four distributions. We conducted a post hoc Tukey test to find the differences between specific groups’ means, considering all possible pairs of means. Resources and analytic codes are available on GitHub and OSF.io (https://osf.io/qruf3).

3. Results

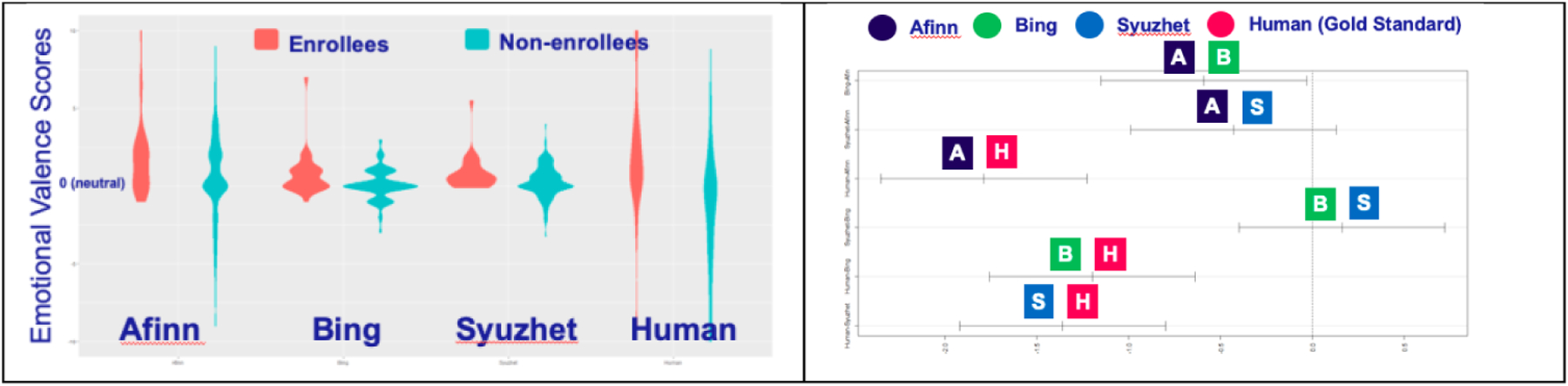

The aggregated mean emotional scores from the machine learning tools were slightly positive, while the mean score from human coding as a gold standard was negative among the total of 249 randomly selected direct Twitter messages. Visual examination of the emotional valence distribution graphs showed distinct results from each algorithm (Figure 1). While the center of the distribution from human coding (ground truth) was slightly negative (−1), the centers of the results from the machine-learning algorithms were above 0 (positive). A substantial amount of the direct messages from non-enrollees expressed extremely negative emotions, primarily in reaction to being excluded from the study. These exhibited longer tails towards negative valences in the human coding (gold standard), while the machine learning algorithms rarely assigned such messages negative scores (i.e., [notes sender’s parents have dementia and asks why anyone who needs help would be excluded] EVAfinn = 1 [positive], EVBing = 0 [neutral], EVhuman = −4.2 [negative]) (Figure 1). The 10 messages with the largest discrepancies in emotional valence scores between machine learning and human coding (|EVmachine - EVhuman|) include: [a retort with the abbreviation “WTAF”] discrepancy = 10.85; [claims the screening invaded the sender’s privacy; uses vulgarity and insults] 10.40; [refers to researchers as “liars”] 9.00; [notes that the sender’s relative has dementia; describes the dismissal from the study as “extraordinarily offensive”] 8.43; [valediction using the phrase “get stuffed”] 8.40; [strongly disparaging the intelligence of the sender of the dismissal message] 8.40; [alleges the study is a “scam”] 8.20; [expresses strong bitterness with vulgarity] 8.0; “F*** you” 8.00; [disparaging comment using vulgarity] 8.00.

Figure 1.

Sentiments computed between enrollees and non-enrollees (left); the mean differences between sentiment scores calculated by different algorithms and human coding with 95% confidence intervals (right)

ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference among the four means of emotional valence scores after normalizing the scales of the distributions (Afinn 0.763, 95% CI [0.428, 1.098]; Bing 0.173, [0.041, 0.305]; Syuzhet 0.334, [0.210, 0.458]; Human coding as a gold standard −1.025, [−1.497, −0.553], p=0.001). All three machine learning algorithms showed similar performance, with none specifically distinguished by being closer to the ground truth human coding (Figure 1).

4. Discussion and Conclusion

This study explored the differences in emotional valence scores assigned to Twitter direct messages during the screening period for a Twitter-based social support clinical trial for family caregivers of persons with dementia using manual human coding versus machine learning. We found clusters of extremely negative sentiments from messages among non-eligible followers expressing disappointment and frustration at their exclusion from the study. The criteria for qualifying participants of this study (NCT03865498) required applicants’ ethno-racial identity to be either African American or Hispanic, a requirement which was based on accumulated evidence on health disparity in dementia [1]. These emotional valence scores highlight an overwhelming reverberation of negative backlash from non-eligible applicants who did not meet this precondition. The observed negative sentiment may be explained by theories of how social exclusion triggers emotions of rejection. Our findings of this visceral emotional response to rejection are consistent with similar studies. Connections between online social exclusion stimuli and feelings of loneliness versus belongingness should be further explored [4]. This occurrence also highlights the demand for programs serving dementia caregivers. Considering the emotional burdens of family caregivers of persons with dementia, similar clinical studies or evidence-based programs are urgently needed for all racial and ethnic groups.

Regarding the adoption of machine learning sentiment analysis in the health domain, the Afinn, Bing and Syuzhet algorithms were able to detect overall positive sentiments fairly well, even within a rather complicated context (a demographic-based screening process for a clinical trial involving family members of a person with memory issues or dementia). Our finding in this study using English corpora of direct Tweet messages is consistently similar to our previous work analyzing the Korean language Twitter messages translated to English [3]. Meanwhile, the greatest discrepancies between machine learning and human coding were due to the machine learning approaches not recognizing the negative sentiments in some expressions. It was surprising that the software packages were not able to recognize dictionary-listed slang or abbreviations (e.g., “Get stuffed then,” “WTAF”) or scored very negative terms (by human coding) as mildly negative (e.g., “F*** you”) [3]. Further studies of alternative algorithms or tuning methods are required to improve negative sentiment detection [3, 5]. A small sample size in a specific domain limits the generalizability of our findings. Future studies in other chronic diseases with a larger sample size are needed [3].

In conclusion, the three analysis algorithms (Afinn, Bing, Syuzhet) produced generally similar results relative to human coding but struggled to identify strongly negative emotional valences when used to detect sentiment in dementia caregiving-related Twitter direct messages. Given the strenuous responses of followers to being found non-eligible for the study, alternative strategies to provide similar research opportunities to non-eligible family caregivers should be provided in the future. Our findings add to the knowledge that unfiltered and honest sentiments expressed by dementia caregivers were successfully captured in direct messages in a social media-based clinical trial, and shed light on productive techniques for analyzing social media to aid dementia caregivers [6].

Acknowledgments

U.S. federal grants R01AG060929 (PI: Yoon) and UL1TR001873.

References

- [1].Alzheimer’s Association. Race, ethnicity and Alzheimer’s in America, 2021.

- [2].Package Jockers M. “syuzhet.” Available at https://cran.R-project.org/web/packages/syuzhet. 2020.

- [3].Yoon S, Broadwell P, Sun FF, Jang SJ, Lee H. Comparing emotional valence scores of Twitter posts from manual coding and machine learning algorithms to gain insights for interventions for family caregivers of persons with dementia. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2022. Jun;295:253–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Covert JM, Stefanone MA. Does rejection still hurt? Examining the effects of network attention and exposure to online social exclusion. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev 2020. Apr;38(2):170–86. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Melton CA, White BM, Davis RL, Bednarczyk RA, Shaban-Nejad A. Fine-tuned sentiment analysis of covid-19 vaccine–related social media data: Comparative study. J. Med. Internet Res 2022. Oct ;24(10):e40408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bailey ER, Matz SC, Youyou W, Iyengar SS. Authentic self-expression on social media is associated with greater subjective well-being. Nat. Commun 2020. Oct ;11(1):4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]