Abstract

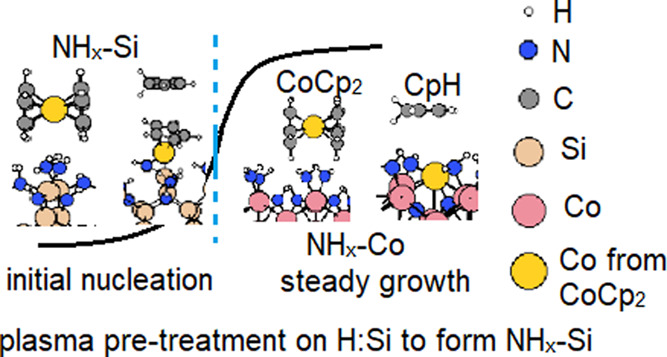

Early transition metals ruthenium (Ru) and cobalt (Co) are of high interest as replacements for Cu in next-generation interconnects. Plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition (PE-ALD) is used to deposit metal thin films in high-aspect-ratio structures of vias and trenches in nanoelectronic devices. At the initial stage of deposition, the surface reactions between the precursors and the starting substrate are vital to understand the nucleation of the film and optimize the deposition process by minimizing the so-called nucleation delay in which film growth is only observed after tens to hundreds of ALD cycles. The reported nucleation delay of Ru ranges from 10 ALD cycles to 500 ALD cycles, and the growth-per-cycle (GPC) varies from report to report. No systematic studies on nucleation delay of Co PE-ALD are found in the literature. In this study, we use first principles density functional theory (DFT) simulations to investigate the reactions between precursors RuCp2 and CoCp2 with Si substrates that have different surface terminations to reveal the atomic-scale reaction mechanism at the initial stages of metal nucleation. The substrates include (1) H:Si(100), (2) NHx-terminated Si(100), and (3) H:SiNx/Si(100). The ligand exchange reaction via H transfer to form CpH on H:Si(100), NHx-terminated Si(100), and H:SiNx/Si(100) surfaces is simulated and shows that pretreatment with N2/H2 plasma to yield an NHx-terminated Si surface from H:Si(100) can promote the ligand exchange reaction to eliminate the Cp ligand for CoCp2. Our DFT results show that the surface reactivity of CoCp2 is highly dependent on substrate surface terminations, which explains why the reported nucleation delay and GPC vary from report to report. This difference in reactivity at different surface terminations may be useful for selective deposition. For Ru deposition, RuCp2 is not a useful precursor, showing highly endothermic ligand elimination reactions on all studied terminations.

1. Introduction

Cu is used as the interconnect metal in CMOS devices, but it faces significant challenges in its continued use in high-speed ultralarge-scale integrated circuits. A diffusion barrier and a liner layer are needed for Cu deposition to ensure that it remains conducting, but there are significant challenges in Cu deposition in high-aspect-ratio structures of vias and trenches.1−4 As device dimensions shrink and more complex structures emerge, the volume available for the copper interconnect at the transistor levels becomes correspondingly smaller and must still accommodate the barrier, the liner, and copper. One solution to these critical issues is to replace copper with alternative metals with low resistivity at the nanoscale that suffer less from these challenges. In this regard, early transition metals ruthenium5−7 (Ru) and cobalt8−11 (Co) are of high interest as alternative materials for replacing Cu in next-generation interconnects. While these metals are potentially facing supply issues, the amount of metal needed for interconnects at the transistor level, so-called level 1 and level 2 interconnects, will be very small, necessitating only limited quantities of both metals so that they are viable candidates for low-level interconnects.

To deposit metals onto these complex three-dimensional structures, atomic layer deposition (ALD) is the leading technique that allows for conformal and uniform deposition of atomic-scale metal thin films with precise thickness control.12−14 ALD of a metal consists of two self-limiting half-cycles, namely, a metal precursor reaction, followed by a purge to remove undesired precursors, and a reduction pulse, where the metal center is reduced, followed by another pulse. The advantage of ALD is its self-limiting nature, where reactions will, in principle, stop after all available surface sites are consumed, thus allowing fine control over thickness, high uniformity, and high conformality. ALD of metal thin films can be conducted at low temperatures, typically 300–600 K, when applying plasma-enhanced ALD (PE-ALD).15 For example, Ag thin films were deposited at 393.15 K using Ag(fod)(PEt3) together with plasma-activated hydrogen.16 Ru thin films were deposited at 543.15 K using Ru(EtCp)2 and NH3 plasma.5 Previous studies have reported the use of H2O or O3 to deposit metal oxides such as Al2O3, SiO2, and HfO2.17−20 However, when depositing metals, an O source will promote oxidation of the metal via the formation of surface metal–oxygen bonds and therefore cause contamination and modify the properties of the metal.21 Thus, a nonoxidizing reactant is preferred for PE-ALD of metals, where N plasma is used with typical plasma sources being NH3 or a mixture of N2 and H2.8,22−24

Cyclopentadienyl (Cp, C5H5)-based metal precursors, such as bis(cyclopentadienyl)cobalt(II) (CoCp2) and Bis(ethylcyclopentadienyl)ruthenium(II) (Ru(EtCp)2), are the most commonly used precursors for ALD of Ru and Co.25−27 The structure of Cp-based metal precursors is that the Cp ligands coordinate to the metal center and each Cp ligand has five metal-C bonds, which yields monomeric thermally stable precursors. The precursor properties can be modified by functionalizing the Cp ligand with different substituents, which can result in enhanced volatility, increased thermal stability, and decreased melting point.28 The reported growth-per-cycle (GPC) for PE-ALD of Ru29 using Ru(EtCp)2 and N plasma varies from 0.2 Å/cycle30 (NH3 plasma, PE-ALD temperature at 373 to 543 K) to 0.38 Å/cycle7 (N2/H2 plasma, PE-ALD temperature at 473 K). The PE-ALD of Co thin films using CoCp2 is highly dependent on the plasma source, where NH3 plasma or a mixture of N2 and H2 can result in high quality and low impurity Co thin films, but separated N2 and H2 plasma pulses yield low quality and high impurity Co thin films.8,24,31 The significance of active NxHy (x = 0 or 1, y = 0, 1 or 2) radicals in plasma ALD of Co together with surface NHx (x = 1 or 2) terminations were described in our previous studies in eliminating Cp ligands in the metal precursor pulse32,33 and in the plasma pulse34 in addition to removing from the growing film and regenerating the surface NHx terminations at the post-plasma stage to be ready for the next deposition cycle.

In addition to metal precursors and ALD operating temperature, the nature of the initial substrate plays an important role in the growth of metal films, especially at the initial stages, or nucleation, of thin film growth. The investigation of the initial stages of metal ALD growth is necessary for the complete understanding of the reaction mechanisms between the metal precursor and substrates. Silicon (Si)- and SiO2-covered wafers are commonly used as substrates for metal deposition in the semiconductor industry.23 Usually, a Si substrate is cleaned by dipping in diluted HF solution, followed by rinsing with deionized water and blowing with dry N2, and the wafer is immediately loaded into the ALD chamber to prevent the formation of native oxide. A SiO2 substrate goes through a similar process that includes dipping in acetone and isopropyl alcohol, rinsing with deionized water, and blowing with dry N2. In this way, the relevant substrate terminations are H:Si(100)/H:Si(001) and OH:SiO2(001). In addition to Si and SiO2 wafers, previous studies have deposited Ru thin films on TaN/SiO2/Si or TiN/SiO2/Si substrates,6,29 which is used for the conformal Cu seed layers on high aspect ratios via holes and trenches.

Among the experimental studies for PE-ALD of Ru on these substrates, the observed nucleation delay (the number of cycles before growth is observed) varies from report to report, as listed in Table 1. For Ru(EtCp)2, a nucleation delay of more than 500 ALD cycles on TiN substrate is observed when using N2/NH3 plasma at 323 K, while the nucleation delay is reduced to 120 ALD cycles when switching to N2/H2 plasma at 323 K.29 This is different from other literature reports in which NH3-based plasmas are used to deposit Ru on TiN substrate without long nucleation delay time.5,36 In the same study, when a different metal precursor, methylcyclopentadienylpyrrolyl ruthenium ((MeCpPy)Ru), is applied, the reported nucleation delay on TiN substrate is less than 10 ALD cycles for both N2/NH3 and N2/H2 plasmas at 323 K. When the substrate is changed to SiO2 substrate, a longer nucleation delay is observed with N2/H2 plasma and Ru(EtCp)2.

Table 1. Summary of Reported Nucleation Delay for Ru PE-ALD in the Literaturea.

| references | substrates | metal precursor | plasma type | temperature K | nucleation delay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swerts et al.29 | TiN/Si wafer | (MeCpPy)Ru | N2/H2 or N2/NH3 | 323 | <10 ALD cycles |

| TiN/Si wafer | Ru(EtCp)2 | N2/H2 | 323 | ∼120 ALD cycles | |

| TiN/Si wafer | Ru(EtCp)2 | N2/NH3 | 323 | >500 ALD cycles | |

| Swerts et al.35 | SiO2 | (MeCpPy)Ru | N2/NH3 | 603 | ∼120 ALD cycles |

| TiN/Si wafer | (MeCpPy)Ru | N2/NH3 | 603 | ∼50 ALD cycles | |

| Xie et al.30 | TaN/Si wafer | Ru(EtCp)2 | NH3 | 543 | ∼50 ALD cycles |

| Kwon et al.36 | TiN/Si wafer | Ru(EtCp)2 | NH3 | 543 | <10 ALD cycles |

No data of nucleation delay for Co PE-ALD in the literation was found.

Experimental data for nucleation delay in PE-ALD of Co is not discussed in the literature.

Therefore, at the initial stages of film growth, the surface reactions between metal precursors and the starting substrate and the corresponding chemistries are vital to understand the reaction mechanism behind the deposition process and any nucleation delay. In studying the nucleation of a film in an ALD process, we consider that the first step of precursor adsorption, followed by ligand elimination, is crucial. Providing the atomic-level details of the Co and Ru precursor chemistry at a series of differently terminated silicon surfaces is the key advance of the current paper.

Density functional theory calculations are widely applied to study the ALD of metals and metal oxides.37−40 Outstanding questions, such as precursor design, precursor reactivity with surfaces, and their reactions with different coreactants, can be explored by DFT calculations. In our previous work, we have investigated the coverage and stability of NHx-terminated Ru and Co surfaces,41 the reaction mechanism in the first half-cycle after introducing metal precursors RuCp2 or CoCp2,32,33 and the reactions between plasma-generated radicals and metal precursor-treated NHx-terminated Ru and Co surfaces.34

In this paper, we consider the initial nucleation of the metal film and investigate the reactions between the precursors RuCp2/CoCp2 and a series of Si-based substrates, namely, (1) H:Si(100), (2) NHx-terminated Si(100), (3) H:SiNx/Si(100), and (4) bare Si(100), to reveal the atomic-scale reaction mechanism at the first stages of metal deposition. On the bare Si(100) surface, which we use as a reference (see the Supporting Information), the mechanism involves metal–carbon bond breaking, yielding an adsorbed metal atom and two adsorbed Cp rings; this reaction is exothermic with computed energy changes of −7.39 eV for RuCp2 and −6.80 eV for CoCp2. However, the difficulty here is twofold: first, obtaining a bare Si surface is not likely at typical ALD operating conditions and, second, the removal of the adsorbed Cp rings will be limited and they will persist on the surface, blocking reactive sites. On H:Si(100), RuCp2 and CoCp2 have endothermic reactions for the elimination of Cp ligands via CpH formation and desorption. After N2/H2 plasma treatment, yielding NHx–Si(100), the resulting NHx terminations can promote the first Cp ligand elimination for CoCp2, which is overall exothermic and has a moderate activation barrier for the H transfer step. However, RuCp2 has an endothermic reaction for the elimination of Cp ligands on both H:Si(100) and NHx–Si(100). The H:SiNx/Si(100) substrate is built by allowing N migration into the underlying Si substrate and is H-terminated. Ligand elimination on this substrate via H transfer is not favored. Our results show that the reactivity of Cp ligand elimination on a series of Si surfaces is highly dependent on substrate terminations, which explains why the reported nucleation delay and GPC vary from report to report. We propose that pretreatment with N2/H2 plasma to yield an NHx-terminated Si surface can reduce the nucleation delay and promote faster deposition of metal films. This termination-dependent reaction may also be used for selective deposition or inhibition of film deposition.

2. Methods and Computational Details

All of the calculations are performed on the basis of periodic spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) within a plane wave basis set and projector augmented wave (PAW) formalism,42 as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP 5.4) code. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) parameterization is used for the exchange–correlation functional.43,44 We use nine valence electrons for Co, eight for Ru, five for N, four for C, and one for H. The plane wave energy cutoff is set to 400 eV. The convergences of energy and force are set to be 1 × 10–4 eV and 0.01 eV/Å, respectively.

The Si(100) surface is modeled with slab models with both (2 × 2) and (3 × 3) surface supercells, consisting of ten layers of Si, where the bottom four layers are fixed during the calculations. A vacuum region of 15 Å is applied, and a 3 × 3 × 1 k-points mesh45 is used throughout the calculations for all slab models. The (2 × 2) supercell is applied to determine the saturation coverages of different surface terminations. The (3 × 3) supercell is applied for precursor adsorption and ligand exchange reaction simulations. The computed surface areas for Si(100) substrates are 0.59 nm2 for the (2 × 2) supercell and 1.33 nm2 for the (3 × 3) supercell. At these computed surface termination coverages, the computed numbers of nucleation sites are 6.78 per nm2 for H with H terminations and 13.56 per nm2 for surface NH2 (preferred H transfer source) with NHx terminations. The details of H and NHx terminations are summarized in Section 3.

For the reactions involving metal precursors RuCp2 and CoCp2, the van der Waals correction39 was applied with the PBE-D3 method to ensure an accurate description of adsorption energy and reaction energy. When single-metal precursors are placed on the surface, the coverage of metal precursors is 0.75 precursor/nm2 for our (3 × 3) surface supercell model. Charge transfers were analyzed with the Bader charge analysis procedure. This was computed by q(Bader) – q(valence).

Molecular dynamics (MD) calculations are performed at 600 K with a time step at 1.5fs and a total running time of 2.25 ps within the NVT (canonical) ensemble. The activation barriers reported in this paper are computed using the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method46 with six images, including the starting and ending geometries, and with the forces converged to 0.05 eV/Å.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Metal Precursors RuCp2 and CoCp2 Adsorbed on H-Terminated and NHx-Terminated Si(100) Surfaces

We first address the chemistry of the metal precursors interacting on H-terminated and NHx-terminated metal surfaces. To study H terminations, a full monolayer (ML) coverage of hydrogen, i.e., nine H atoms for the (2 × 2) supercell, is placed on top of surface Si atoms. After hydrogen passivation, the surface Si atoms have formed the well-known Si–Si dimer with a bond length of 2.42 Å, while for bare Si(100), the Si–Si distances of surface Si atoms are 3.84 Å. The atomic structure of this model is shown in Figure S2 of the SI.

For Co deposition, experimental evidence has confirmed that the existence of N and H is essential to deposit metallic Co films with high purity and low resistance.24 To explore NHx terminations, we terminate the Si (100) surface with Si–NHx (x = 1 or 2) terminations. The adsorption sites and reactions from standard 0 K DFT calculations of eliminating surface H terminations, generation of NH/NH2 terminations, and changes in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of NH/NH2 terminations on the Si(100) surface are given in the Supporting Information. The most favorable NHx terminations are 1 ML NH and 1 ML NH2, which yield 4NH + 4NH2 on the (2 × 2) supercell (Figure S9, SI) and 9NH + 9NH2 on the (3 × 3) supercell (Figure 1). NH occupies the surface bridge sites and NH2 occupies the surface top sites, which is similar to our previous reports on favorable NHx-terminated Ru and Co surfaces.41 H atoms from surface top NH2 and surface bridge NH are referred to as surface H and bridge H when we describe the ligand exchange reactions.

Figure 1.

Adsorption structures of RuCp2 and CoCp2 precursors on the H-terminated Si(100) surface in the more favorable horizontal mode [(a) RuCp2 and (b) CoCp2] and on the NHx-terminated Si(100) surface [(c) RuCp2 and (d) CoCp2]. Si, C, and H are represented by dark yellow, black, and white spheres, respectively. Ru and Co are represented by green and orange spheres, respectively.

Metal precursors RuCp2 and CoCp2 are then adsorbed at the two terminations of Si(100), and the more favorable adsorption energies are found for the horizontal interaction mode, consistent with our earlier studies.32,33 The computed adsorption energies on H-terminated and NHx-terminated Si(100) substrates are summarized in Table 2, and the configurations are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2. Computed Adsorption Energies of Metal Precursors RuCp2 and CoCp2 with Horizontal Binding Mode on H-Terminated and NHx-terminated Si(100) Surfacesa.

| RuCp2Ead/eV |

CoCp2Ead/eV |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (3 × 3) | horizontal | upright | horizontal | upright |

| H–Si(100) | –0.30 | –0.13 | –0.98 | –0.84 |

| NHx–Si(100) | –0.67 | –0.59 | –0.87 | –0.64 |

The (3 × 3) supercell is applied.

CoCp2 has stronger adsorption strength than RuCp2 on both substrates, which is −0.98 eV on H–Si(100) and −0.87 eV on NHx–Si(100) for CoCp2 and −0.37 eV on H–Si(100) and −0.67 eV on NHx–Si(100) for RuCp2. This difference is analogous to the results on NHx-terminated Ru(100) and Co(100) surfaces in our previous studies,32,33 where the computed adsorption energies for CoCp2 and RuCp2 are −1.67 and −0.79 eV, respectively. Upon adsorption on both H:Si(100) and NHx–Si(100) surfaces, the Co–C distances are in the range of 2.05–2.08 Å, while the Ru–C distances are in the range of 2.18–2.19 Å. In the gas-phase metal precursors, CoCp2 has a Co–C distance ranging from 2.08 to 2.10 Å and RuCp2 has a Ru–C distance of 2.18 Å. There are no significant distortions to the structure of the metal precursors upon interaction at this H-terminated Si (100) surface.

3.2. Ligand Exchange Reactions on the H-Terminated Si(100) Surface

After adsorption of metal precursors, we explore the ligand exchange reaction to eliminate the Cp ligand through H transfer, CpH formation, and CpH desorption, which is the same as the NHx-terminated Co and Ru surfaces.32,33 The computed reaction energies along the pathway for Cp ligand elimination on the H-terminated Si(100) surface for RuCp2 and CoCp2 are shown in Figure 2. We see that one Cp ligand could be eliminated for both precursors, with the computed reaction energies for the elimination of the first CpH being 0.05 eV for RuCp2 and 0.12 eV for CoCp2. The overall reaction energy for elimination of two Cp ligands is endothermic for both precursors. The computed energy cost for elimination of two Cp ligands is 2.83 eV for CoCp2 and 2.09 eV for RuCp2.

Figure 2.

Reaction pathway for Cp ligand elimination via H transfer on the H-terminated Si(100) surface for metal precursors RuCp2 and CoCp2.

Therefore, elimination of both Cp ligands for RuCp2 and CoCp2 is unlikely on H-terminated Si(100), although elimination of one Cp ligand may be possible at typical ALD operating conditions at around 400–650 K.

At ALD conditions for PE-ALD of Ru and Co, it is reasonable to consider that the surface termination can change from H termination to NHx termination via the reaction with plasma-generated •N, •H, •NH, and •NH2 radicals, and we consider the chemistry on this surface next.

3.3. Ligand Exchange Reactions on the NHx-Terminated Si(100) Surface

After adsorption of metal precursors on the NHx-terminated Si(100) surface (Figure 1, Table 2), we examine the ligand exchange reaction for Cp ligand elimination via the surface H transfer, CpH formation, and CpH desorption pathways. As explained earlier, we have considered transfer of the bridge hydrogens from NH terminations and surface hydrogen from NH2. The resulting reaction energies for the Cp ligand elimination reaction are computed and shown separately for each precursor in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Plotted reaction pathways for Cp ligand elimination via H transfer on the NHx-terminated Si(100) surface for metal precursors (a) RuCp2 and (b) CoCp2.

In Figure 3a, for RuCp2, the overall reaction energy is positive for the transfer of surface and bridging hydrogen on the NHx-terminated Si(100) surface, making CpH elimination clearly unfavorable. After the first CpH formation and desorption, the computed reaction energy is 0.83 eV for H transfer from surface NH2 and 1.53 eV for H transfer from bridge NH. The computed reaction energies for the second H transfer continue to be positive for both types of H transfer: after formation of the second CpH, the computed reaction energy is as high as 3.62 eV for H transfer from surface NH2 and 1.79 eV for H transfer from bridge NH.

In Figure 3b, for CoCp2, the overall reaction energy is negative for the first Cp ligand elimination with H transfer from surface NH2. A moderate energy barrier of 0.73 eV is computed for the surface H transfer step. The configuration of the transition state is shown in the Supporting Information. After CpH formation and elimination, the computed energy gain is −0.21 eV. For the second surface H transfer, the computed reaction energy is positive. After the second CpH desorption, the computed reaction energy is positive at 1.86 eV. By contrast, for H transfer from bridge NH, the overall reaction energy is positive for the first and second Cp elimination. The computed reaction energies are 0.68 eV for the first CpH desorption and 0.49 for the second CpH desorption. Since the Cp ligand elimination process for this pathway is endothermic, no barrier calculations are performed for H transfer from bridge NH.

Transfer of surface H is preferred since it leaves an NH surface termination, while a bridging H will leave a bare, undercoordinated N atom, which we would expect to be unstable and hence unfavorable.

In our previous study of depositing Ru on NHx-terminated metal surfaces,33 we discussed that the energy cost to break the Ru–C bond is higher due to the stronger Ru–C bond strength. The bond energies between the metal and the Cp rings in RuCp2 and CoCp2 were calculated as 3.05 eV per Ru–C bond and 2.96 eV per Co–C bond.47 For depositing Ru thin films, Ru compounds with more complex Cp-based ligands are used experimentally rather than RuCp2; these ligands appear to offer higher reactivity. For Co thin films, CoCp2- and N-plasma-based PE-ALD processes have been demonstrated in the literature.8−11,24 Our DFT results indicate that RuCp2 is not a favorable candidate for depositing Ru thin films. This is also consistent with the experimental work in which we found only one paper48 in the literature that has used RuCp2 and N plasma for PE-ALD of Ru thin-film deposition, while other reports have used ruthenium compounds with more complex Cp-based ligands such as Ru(EtCp)2 and (MeCpPy)Ru.29,30,35

For CoCp2, when comparing H terminations and NHx terminations, the energy gain on the NHx-terminated Si(100) surface, −0.21 eV, is more favorable than that on H-terminated Si, 0.12 eV. This provides further evidence that the plasma-generated NxHy radicals are essential to promote Co metal deposition in addition to preventing metal oxidation. From our results, we suggest that if we apply the N plasma (NH3 or mixture of N2 and H2) treatment on the H:Si(100) substrate as the first step in Co ALD with CoCp2, the nucleation delay can be reduced. In addition, the differences we see for surface reactivity also suggest the possibility of area-selective ALD mediated by these NHx terminations and H terminations.

3.4. Ligand Exchange Reactions on H:SiNx–Si(100) Terminations

In terms of growth behavior, the PE-ALD of metal thin films has two regions: an initial nucleation region and a steady growth region. In the steady growth region, the surface terminations are NHx-terminated Ru or Co surfaces (x = 1 or 2).41 Our previous studies have investigated the reaction mechanisms of eliminating the Cp ligand on these NHx-terminated Ru or Co surfaces in the metal precursor half-cycle and found that the Cp ligand is eliminated via H transfer, CpH formation, and CpH desorption.32,33 The remaining Cp rings after the metal precursor cycle are eliminated at the plasma cycle by reacting with plasma-generated •H radicals. This explains the low C impurity in the deposited Co thin films, where most of the Cp ligand is removed via CpH, and the decomposition of Cp is not preferred.

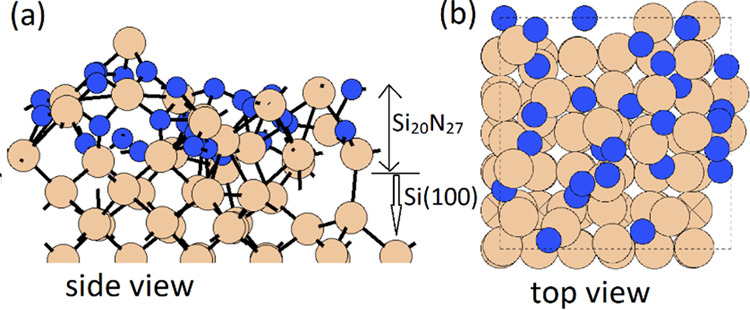

In addition to the two surface terminations of Si(100) described above, we further investigate the possible formation of SiNx/Si(100) and H:SiNx/Si(100) substrates. These can form via surface Si atoms reacting with plasma-generated •N and •H radicals, which can migrate through the Si surface. These surfaces were generated with ab initio MD calculations, and full details are given in the Supporting Information. The resulting SiNx/Si(100) and H;SiNx/Si(100) are shown in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4.

Configurations of the stable structure of the SiNx/Si(100) substrate in (a) side view and (b) top view. Si and N atoms are represented by dark yellow and blue spheres, respectively.

Figure 5.

Configurations of the stable structure of the H:SiNx/Si(100) substrate in (a) side view and (b) top view. Si, N, and H atoms are represented by dark yellow, blue, and white spheres, respectively.

Precursors RuCp2 and CoCp2 adsorb at the SiNx/Si(100) and H:SiNx/Si(100) surfaces with computed adsorption energies summarized in Table 3. The preferred binding mode is the horizontal mode, the same as on the other substrates, and this adsorption mode shows computed adsorption energies of −0.47 eV for RuCp2 and −0.76 eV for CoCp2 on the H:SiNx/Si(100) substrate and −0.53 eV for RuCp2 and −1.74 eV for CoCp2 on the SiNx/Si(100) substrate. Again, CoCp2 shows stronger interaction on the surface compared to RuCp2. The larger adsorption energy on SiNx termination compared to that on H:SiNx termination may reflect undercoordinated atoms on the surface terminating layer.

Table 3. Computed Adsorption Energies of Metal Precursors RuCp2 and CoCp2 with Horizontal and Upright Binding Modes on SiNx/Si(100), H:SiNx/Si(100), and Bare Si(100) Surfaces.

| RuCp2 Ead/eV | CoCp2 Ead/eV | |

|---|---|---|

| (3 × 3) | horizontal | horizontal |

| H:SiNx/Si(100) | –0.47 | –0.76 |

| SiNx/Si(100) | –0.53 | –1.74 |

| bare Si(100) | –5.87 | –6.07 |

On the H:SiNx/Si(100) surface, we consider the elimination of Cp via the H transfer, CpH formation, and CpH desorption pathway. RuCp2 has a computed high energy cost at 2.37 eV for the H transfer step, regardless of which H is involved, that is, from H–Si, NH, or NH2. Thus, no further calculations are performed to generate the full reaction pathway for RuCp2. For CoCp2, the computed reaction energy is exothermic for H transfer from NH to Cp, with a computed value of −0.81 eV, whereas H transfer from NH2 or H–Si has endothermic reaction energy. Despite this exothermic H transfer step for CoCp2, the overall reaction energy for first Cp ligand elimination is actually positive at 0.60 eV. Thus, the elimination of the Cp ligand via H transfer, CpH formation, and CpH desorption pathways on the H:SiNx/Si(100) surface is thermodynamically not favored. No full reaction pathway is plotted for H:SiNx/Si(100) due to unfavorable reactions. Compared to NHx terminations of 1 ML NH + 1 ML NH2 discussed in Section 3.3, this H:SiNx termination has a thicker layer and lower activity toward Cp ligand elimination.

In addition to SiNx/Si(100) and H:SiNx(100), a bare Si(100) surface is applied to explore a case where surface NHx terminations may have desorbed due to high operating temperatures. However, the bare Si(100) surface does not exist at typical ALD conditions; the Si surface is covered with NHx terminations after reacting with plasma-generated NxHy radicals, but we include this surface for completeness. Both precursors have significantly more exothermic adsorption energies on bare Si(100). These more exothermic adsorption energies are due to the surface dangling Si atoms, indicating that hydrogen and NHx terminations passivate Si. This is also observed by Phung49 et al., where adsorption of RuCp2 was proposed to be less favorable on the H-terminated Ru(001) surface in comparison to that on the bare Ru(001) surface. The precursors dissociate into a bare metal atom and two adsorbed Cp species, and the adsorption energies suggest these will persist on the surface; this is reasonable since the adsorbed Cp will passivate the dangling Si bonds.

4. Conclusions

We studied the first reactions in PE-ALD of Ru and Co using cyclopentadienyl-based metal precursors RuCp2 and CoCp2 on various silicon substrates, including (1) H:Si(100), (2) NHx-terminated Si(100), (3) H:SiNx/Si(100), and (4) bare Si(100), to gain a systematic understanding of the reaction mechanism between these precursors and substrates. On the H:Si(100) surface, both precursors show a thermoneutral reaction energy for the elimination of the first Cp ligand via H transfer from the substrate. At most, only one Cp ligand is eliminated for both RuCp2 and CoCp2 on the H:Si(100) surface since the second Cp ligand elimination step is highly endothermic.

We can consider a modification to this Si(100) surface termination to surface NHx terminations by running the plasma step first and exploiting radicals •NH and •NH2 to modify to an NHx–Si(100) surface. The elimination of surface H terminations via H2 formation and desorption with plasma radical •H is endothermic. The preferred NHx termination on the Si(100) surface at a typical ALD operating temperature of 600 K is 1 ML NH + 1 ML NH2, with NH2 occupying surface top sites and NH occupying surface bridge sites. This is analogous to our previously analyzed mixed NHx terminations on Ru(100) and Co(100) surfaces, where NH2 occupies surface sites and NH prefers bridge sites on the metal surface.

On the NHx-terminated Si(100) surface, RuCp2 shows endothermic reactions for elimination of both Cp ligands. On the contrary, NHx terminations can promote the first Cp ligand elimination for CoCp2 with the computed overall reaction energy at −0.21 eV, and the reaction energies to eliminate both Cp ligands on the NHx-terminated Si(100) surface is endothermic. The computed activation barrier for the first H transfer step is moderate at 0.73 eV. This difference is due to the stronger Ru–C bond strength compared to Co–C bond strength. This is also observed in the elimination of Cp ligands on NHx-terminated Ru and Co surfaces, where CoCp2 has exothermic reaction energies and low activation barriers on NHx-terminated Co(001) and Co(100) surfaces, but RuCp2 has endothermic reaction energies and high activation barriers on NHx-terminated Ru(001) and Ru(100) surfaces.

Both precursors have endothermic reactions of Cp ligand elimination on the H:SiNx/Si(100) surface. Compared to the NHx termination, the H:SiNx termination is thicker and shows less reactivity. This indicates that the surface reactivity is highly dependent on substrate terminations, which can also be utilized for area-selective deposition.

Therefore, in the initial stages of PE-ALD of Co with CoCp2, our results show that N2/H2 plasma pretreatment on the Si substrates would generate surface NHx terminations, which promote Cp ligand elimination and will reduce the nucleation delay relative to H-terminated silicon. The use of an initial NH3 plasma pulse before the metal pulse would produce this substrate. However, the resulting surface should not have a thick Si–NHx terminating region, which promotes nucleation delay and can be avoided with a short plasma pulse. In addition, endothermic reactions in some cases suggest that a long nucleation delay will be observed in an ALD process. The reactivity is highly dependent on Si(100) substrate terminations, which can also be utilized for area-selective deposition. For Ru deposition, RuCp2 is not a useful precursor, showing highly endothermic ligand elimination reactions on all Si terminations.

The effect of modifying metal precursors, including ligand modification with MeCp or EtCp, on the reactions at the initial stages are the subject of ongoing work, while a complete understanding of the deposition of Ru or Co for Cu seed layers can be obtained from follow-up work investigating the precursor reaction mechanisms on TaN/SiO2/Si and TiN/SiO2/Si substrates.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge generous support from Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) through the SFI–NSFC Partnership program, Grant Number 17/NSFC/5279, NITRALD, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant number 51861135105. Computing resources have been generously supported by Science Foundation Ireland at Tyndall and through the SFI/HEA-funded Irish Centre for High-End Computing (www.ichec.ie). J.L. acknowledges the support from HPC Vega in Slovenia through the EuroHPC JU call project.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcc.3c02933.

Reaction mechanisms of RuCp2 and CoCp2 on the bare Si substrate, generation of surface NHx terminations with active plasma radicals, and structures of SINx/Si(100) and H:Si(100) with active plasma radicals (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Josell D.; Wheeler D.; Witt C.; Moffat T. P. Seedless superfill: Copper electrodeposition in trenches with ruthenium barriers. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2003, 6, C143. 10.1149/1.1605271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon O.-K.; Kim J.-H.; Park H.-S.; Kang S.-W. Atomic layer deposition of ruthenium thin films for copper glue layer. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, G109. 10.1149/1.1640633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Duquette D. J. Effect of chemical composition on adhesion of directly electrodeposited copper film on TiN. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, C417. 10.1149/1.2189971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mun K.-Y.; Hong T. E.; Cheon T.; Jang Y.; Lim B.-Y.; Kim S.; Kim S.-H. The effects of nitrogen incorporation on the properties of atomic layer deposited Ru thin films as a direct-plateable diffusion barrier for Cu interconnect. Thin Solid films 2014, 562, 118–125. 10.1016/j.tsf.2014.03.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon O.-K.; Kwon S.-H.; Park H.-S.; Kang S.-W. Plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of ruthenium thin films. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2004, 7, C46. 10.1149/1.1648612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S.-H.; Kwon O.-K.; Min J.-S.; Kang S.-W. Plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of Ru–TiN thin films for copper diffusion barrier metals. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, G578. 10.1149/1.2193335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.-C.; Pan F.-M. In Situ Two-Step Plasma Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition of Ru/RuNx Barriers for Seedless Copper Electroplating. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, G97. 10.1149/1.3554734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-B.-R.; Kim H. High-quality cobalt thin films by plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2006, 9, G323. 10.1149/1.2338777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Ramos K.; Saly M. J.; Kanjolia R. K.; Chabal Y. J. Atomic layer deposition of cobalt silicide thin films studied by in Situ infrared spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 4943–4949. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b00743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B.; Ding Z.-J.; Wu X.; Liu W.-J.; Zhang D. W.; Ding S.-J. Plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of cobalt films using Co (EtCp) 2 as a metal precursor. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 76 10.1186/s11671-019-2913-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaloyeros A. E.; Pan Y.; Goff J.; Arkles B. Review—Cobalt Thin Films: Trends in Processing Technologies and Emerging Applications. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, P119–P152. 10.1149/2.0051902jss. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George S. M. Atomic layer deposition: an overview. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 111–131. 10.1021/cr900056b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S. D. Atomic-scale simulation of ALD chemistry. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2012, 27, 074008 10.1088/0268-1242/27/7/074008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richey N. E.; de Paula C.; Bent S. F. Understanding chemical and physical mechanisms in atomic layer deposition. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 040902 10.1063/1.5133390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Profijt H. B.; Potts S.; Van de Sanden M.; Kessels W. Plasma-assisted atomic layer deposition: basics, opportunities, and challenges. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2011, 29, 050801 10.1116/1.3609974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kariniemi M.; Niinisto J.; Hatanpaa T.; Kemell M.; Sajavaara T.; Ritala M.; Leskela M. Plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of silver thin films. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 2901–2907. 10.1021/cm200402j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rai V. R.; Vandalon V.; Agarwal S. Surface reaction mechanisms during ozone and oxygen plasma assisted atomic layer deposition of aluminum oxide. Langmuir 2010, 26, 13732–13735. 10.1021/la101485a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang G.; Xu L.; Ma J.; Li A. Theoretical Understanding of the Reaction Mechanism of SiO2 Atomic Layer Deposition. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 1247–1255. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b04422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widjaja Y.; Musgrave C. B. Atomic layer deposition of hafnium oxide: A detailed reaction mechanism from first principles. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 1931–1934. 10.1063/1.1495847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S. D.; Scarel G.; Wiemer C.; Fanciulli M.; Pavia G. Ozone-Based Atomic Layer Deposition of Alumina from TMA: Growth, Morphology, and Reaction Mechanism. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 3764–3773. 10.1021/cm0608903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karwal S.; Karasulu B.; Knoops H. C. M.; Vandalon V.; Kessels W. M. M.; Creatore M. Atomic insights into the oxygen incorporation in atomic layer deposited conductive nitrides and its mitigation by energetic ions. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 10092–10099. 10.1039/D0NR08921D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari W.; Eom T.-K.; Kim S.-H.; Kim H. Plasma Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition of Ruthenium Thin Films Using Isopropylmethylbenzene-Cyclohexadiene-Ruthenium and NH3 Plasma. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 158, D42 10.1149/1.3515320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J.; Lee H. B. R.; Kim D.; Kim D.; Cheon T.; Cheon T.; Kim S.-H.; Kim H. Atomic layer deposition of Co using N2/H2 plasma as a reactant. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, H1179 10.1149/2.077111jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vos M. F. J.; van Straaten G.; Kessels W. E.; Mackus A. J. Atomic layer deposition of cobalt using H2-, N2-, and NH3-based plasmas: on the role of the co-reactant. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 22519–22529. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b06342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hämäläinen J.; Ritala M.; Leskelä M. Atomic Layer Deposition of Noble Metals and Their Oxides. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 786–801. 10.1021/cm402221y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miikkulainen V.; Leskelä M.; Ritala M.; Puurunen R. L. Crystallinity of inorganic films grown by atomic layer deposition: Overview and general trends. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 021301 10.1063/1.4757907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knisley T. J.; Kalutarage L. C.; Winter C. H. Precursors and chemistry for the atomic layer deposition of metallic first row transition metal films. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 3222–3231. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal Ramos K.; Saly M. J.; Chabal Y. J. Precursor design and reaction mechanisms for the atomic layer deposition of metal films. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 3271–3281. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swerts J.; Delabie A.; Salimullah M.; Popovici M.; Kim M.-S.; Schaekers M.; Van Elshocht S. Impact of the plasma ambient and the ruthenium precursor on the growth of ruthenium films by plasma enhanced atomic layer deposition. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2012, 1, P19–P21. 10.1149/2.003202ssl. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q.; Jiang Y.-L.; Musschoot J.; Deduytsche D.; Detavernier C.; Van Meirhaeghe R. L.; Van den Berghe S.; Ru G.-P.; Li B.-Z.; Qu X.-P. Ru thin film grown on TaN by plasma enhanced atomic layer deposition. Thin Solid Films 2009, 517, 4689–4693. 10.1016/j.tsf.2009.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reif J.; Knaut M.; Killge S.; Winkler F.; Albert M.; Bartha J. W. In Vacuo Studies on Plasma-Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition of Cobalt Thin Films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2020, 38, 012405 10.1116/1.5132891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Lu H.; Zhang D. W.; Nolan M. Reaction Mechanism of the Metal Precursor Pulse in Plasma-Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition of Cobalt and the Role of Surface Facets. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 11990–12000. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c02976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Lu H. L.; Zhang D. W.; Nolan M. Reactions of ruthenium cyclopentadienyl precursor in the metal precursor pulse of Ru atomic layer deposition. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 2919–2932. 10.1039/D0TC03910A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Lu H.; Zhang D. W.; Nolan M. Self-limiting nitrogen/hydrogen plasma radical chemistry in plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of cobalt. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 4712–4725. 10.1039/D1NR05568B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerts J.; Armini S.; Carbonell L.; Delabie A.; Franquet A.; Mertens S.; Popovici M.; Schaekers M.; Witters T.; Tökei Z.; et al. Scalability of plasma enhanced atomic layer deposited ruthenium films for interconnect applications. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2012, 30, 01A103 10.1116/1.3625566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S.-H.; Kwon O.-K.; Kim J.-H.; Oh H.-R.; Kim K.-H.; Kang S.-W. Initial stages of ruthenium film growth in plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 155, H296. 10.1149/1.2868779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phung Q. M.; Vancoillie S.; Pourtois G.; Swerts J.; Pierloot K.; Delabie A. Atomic Layer Deposition of Ruthenium on a Titanium Nitride Surface: A Density Functional Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 19442–19453. 10.1021/jp405489w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi M.; Elliott S. D. Atomistic kinetic Monte Carlo study of atomic layer deposition derived from density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2014, 35, 244–259. 10.1002/jcc.23491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimaiti Y.; Elliott S. D. Precursor Adsorption on Copper Surfaces as the First Step during the Deposition of Copper: A Density Functional Study with van der Waals Correction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 9375–9385. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b01402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S. D.; Dey G.; Maimaiti Y. Classification of processes for the atomic layer deposition of metals based on mechanistic information from density functional theory calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 052822 10.1063/1.4975085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Nolan M. Coverage and Stability of NHx-Terminated Cobalt and Ruthenium Surfaces: A First-Principles Investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 25166–25175. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b06287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G.; Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758. 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Chevary J. A.; Vosko S. H.; Jackson K. A.; Pederson M. R.; Singh D. J.; Fiolhais C. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: Applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 6671. 10.1103/PhysRevB.46.6671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monkhorst H. J.; Pack J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188. 10.1103/PhysRevB.13.5188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henkelman G.; Uberuaga B. P.; Jónsson H. A Climbing Image Nudged Elastic Band Method for Finding Saddle Points and Minimum Energy Paths. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9901–9904. 10.1063/1.1329672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swart M. Metal–ligand bonding in metallocenes: Differentiation between spin state, electrostatic and covalent bonding. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2007, 360, 179–189. 10.1016/j.ica.2006.07.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.-J.; Kim W.-H.; Lee H. B. R.; Maeng W.; Maeng W.; Kim H. Thermal and plasma enhanced atomic layer deposition ruthenium and electrical characterization as a metal electrode. Microelectron. Eng. 2008, 85, 39–44. 10.1016/j.mee.2007.01.239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phung Q. M.; Pourtois G.; Swerts J.; Pierloot K.; Delabie A. Atomic Layer Deposition of Ruthenium on Ruthenium Surfaces: A Theoretical Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 6592–6603. 10.1021/jp5125958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.