Abstract

Background

Acute high-risk abdominal surgery is common, as are the attendant risks of organ failure, need for intensive care, mortality, or long hospital stay. This study assessed the implementation of standardized management.

Methods

A prospective study of all adults undergoing emergency laparotomy over an interval of 42 months (2018–2021) was undertaken; outcomes were compared with those of a retrospective control group. A new standardized clinical protocol was activated for all patients including: prompt bedside physical assessment by the surgeon and anaesthetist, interprofessional communication regarding location of resuscitation, elimination of unnecessary factors that might delay surgery, improved operating theatre competence, regular epidural, enhanced recovery care, and frequent early warning scores. The primary endpoint was 30-day mortality. Secondary endpoints were duration of hospital stay, need for intensive care, and surgical complications.

Results

A total of 1344 patients were included, 663 in the control group and 681 in the intervention group. The use of antibiotics increased (81.4 versus 94.7 per cent), and the time from the decision to operate to the start of surgery was reduced (3.80 versus 3.22 h) with use of the new protocol. Fewer anastomoses were performed (22.5 versus 16.8 per cent). The 30-day mortality rate was 14.5 per cent in the historical control group and 10.7 per cent in the intervention group (P = 0.045). The mean duration of hospital (11.9 versus 10.2 days; P = 0.007) and ICU (5.40 versus 3.12 days; P = 0.007) stays was also reduced. The rate of serious surgical complications (grade IIIb–V) was lower (37.6 versus 27.3 per cent; P = <0.001).

Conclusion

Standardized management protocols improved outcomes after emergency laparotomy.

The SMASH study implemented perioperative standardization for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy in a Swedish setting. The 30-day mortality rate was 10.7 per cent in the intervention group of 681 patients and 14.5 per cent in the control group of 663 patients. The result suggests that standardized management may improve the postoperative outcome after emergency laparotomy.

Introduction

Emergency surgery is associated with morbidity and mortality1. In most healthcare systems, emergency general surgery accounts for a significant part of the public health burden2,3. Many patients have failure of one or more organ systems4,5 and a 30-day mortality rate of 10–20 per cent is not unusual6–14, even in high-income healthcare systems. Nearly 20 000 excess deaths per year occur in the context of emergency surgery in the USA15. Great efforts have been made to improve outcomes with standardized perioperative management9,12. Countries at the forefront have developed national quality improvement programmes for emergency laparotomy6,16.

Encouraged by these changes, in 2017 the NU Hospital Group (Vastra Gotaland County in southwestern Sweden) developed a protocol for standardized management. The SMASH (Standardized perioperative Management of patients operated with acute Abdominal Surgery in a High-risk and emergency setting) study started in February 201817. The aim of the study was to investigate whether standardized perioperative management improved postoperative outcomes after emergency laparotomy in a Swedish context. Data from a prospective consecutive intervention group including all adult patients were compared with those of a control group18 treated at the same surgical centre before implementation of the standardized perioperative protocol.

Methods

This controlled single-centre study evaluated postoperative outcomes after the implementation of a standardized perioperative management protocol for adult patients undergoing high-risk abdominal surgery (emergency laparotomy and, in selected patients, laparoscopy). The study compared an intervention group with a control group. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03549624, registered 8 June 2018), and was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (868-17).

Intervention group

Starting in February 2018, a clinical standardized protocol (the intervention) was activated for every patient in need of an emergency laparotomy. The protocol served as a checklist for the staff involved, with all measures included in standardized management and as a clinical record form for patients included in the study.

Preoperative measures

Following a decision to operate, regardless of location within the hospital (surgical ward, emergency room, or ICU), the following measures were implemented immediately: measurement of vital signs (early warning score), heart rate, BP, respiratory rate, saturation, level of consciousness, and body temperature. Early treatment with antibiotics was implemented, together with insertion of a nasogastric tube and a urinary catheter, followed by extended blood chemical analyses, including haemoglobin concentration, platelet count, white blood count, levels of sodium, potassium, creatinine kinase, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin, and arterial blood gas). In addition, a bedside assessment by the responsible surgeon and anaesthetist was undertaken as soon as possible, followed by communication regarding the best location for preoperative management. For example, a clinically stable patient may be managed for a few hours on a surgical ward until the start of surgery, whereas an unstable patient would be moved directly to either the ICU or the preoperative centre for resuscitation by an anaesthetist before surgery. Both the responsible surgeon and anaesthetist eliminated factors that may delay the start of surgery.

Perioperative measures

A thoracic epidural was applied if there was no contraindication, and in patients for whom the priority for the first incision was more than 30 min (that is 2 or 6 h). This was followed by setting up an arterial line for the best haemodynamic control, and repeated chemical blood and arterial blood gas analyses. Methods for monitoring cardiac output using goal-directed fluid therapy during the perioperative phase were required. During the study interval, the centre used several different non-invasive methods (CardioQTMChichester, United Kingdom, CheetahTMMinneapolis, MN, USA, HemoSphereTMIrvine, CA, USA), but the primary goal was the same—to identify any fluid deficit and to determine whether the patient’s circulation improved with bolus doses of fluid (whether the patient responded to fluid). According to the standardization, there were two rapid sequencing protocols for the induction of anaesthesia, one for clinically stable patients and the other for unstable patients. Finally, the management protocol aimed for the highest level of clinical competence available in the responsible surgeon and anaesthetist in the operating theatre.

Postoperative measures

The basic criteria for postoperative ICU admission were the same as before the introduction of standardized care: failure of one or more vital organ systems. Postoperative care on the recovery ward was upgraded after bedside assessments by the responsible anaesthetist, and extended chemical blood and arterial blood gas analyses on arrival. On arrival on the ward, standard care with early nutrition, optimal pain treatment, and mobilization was upgraded with frequent assessments of the early warning score (initially on arrival, after 2 and 4 h, and then every 8 h in order to detect any deterioration in patients’ clinical status). A detailed presentation of the standardization has been published previously17.

Interprofessional team

An interprofessional working group consisting of nurses from all three surgical wards, the operating ward, recovery ward, and the ICU, a surgeon, and an anaesthetist met once a month, monitoring every patient in the intervention group to check that the standardization was being followed.

All operations versus unique individuals

The SMASH study was designed to include all operations, meaning that one unique individual was registered for each new operation. Power calculations were to include 725 operations. During statistical analysis, two data sets were created, the first with all operations, and the second with unique individuals included only once.

Control group

The group undergoing surgery before standardization (2014–2017) consisted of unselected patients undergoing high-risk abdominal emergency surgery18. Data on the controls were collected retrospectively from the computerized surgery planning system, followed by a review of every patient’s electronic medical records to ensure that all patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included and to collect all necessary data. At this time, no standardized management was undertaken, and the patients received perioperative management according to national practice. All patient-related clinical decisions were made by the responsible surgeon and anaesthetist at the time.

Missed patients

There were patients for whom the clinical protocol could not be found and reviewed by the interprofessional group, or data relating to the protocol were missing, indicating that the protocol had not been activated or had been forgotten in the clinical work. Demographic data and mortality for the missed patients are presented in Table S1.

Variables

The following variables were collected for the two groups in the study. Demographic variables included: age, sex, height and weight, supplemented with data on co-morbidity for smoking, obesity, diabetes, heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic renal failure. The variable renal failure was reported previously in an article with outcomes for the control group, where it represented both acute and chronic renal failure18. Here, the variable was re-evaluated and, after further review, included only patients with chronic renal failure. Demographic variables also included the pathology indicating surgery: mechanical ileus, peritonitis, ischaemic or gangrenous bowel, bleeding, perforation, or trauma. In the study, as in clinical practice, one patient could have several pathologies.

The time point variables described the relevant time flows: time from notification of surgery to first incision, duration of stay in hospital, and number of admissions to ICU and duration of ICU care. In addition, data on the anaesthetic assessment and interventions (induction drug, treatment with vasopressors, arterial line insertion, application of epidural anaesthesia) and the surgical procedures performed (such as adhesiolysis, intestinal resections, stoma, anastomoses, and the removal of other organs) were registered. These data also included the level of clinical perioperative competence (surgical and anaesthetic).

Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary endpoint was short-term postoperative mortality (within 30 days). Secondary endpoints were: postoperative complications according to the Clavien–Dindo classification, duration of hospital stay, postoperative admission to ICU, and duration of stay in ICU. In the future, long-term postoperative mortality (1 year) will also be analysed.

Statistical analysis

On inclusion, each patient’s medical record data were scrutinized in both groups. During this phase of processing and analysing, all the data were deidentified. Categorical variables are presented as number with percentage. The adjusted OR was calculated by GENMOD (General Mode) with the generalized estimating equation (GEE) model, with binary outcome and link function logit adjusted for age, intestinal ischaemia, faecal, purulent/other peritonitis, chronic obstructive lung disease, ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure, diabetes, obesity, smoking, ASA grade, and sex. The OR was calculated by GENMOD with the GEE model, with binary outcome and link function logit. For comparisons between groups, Fisher’s exact test (lowest 1-sided P value multiplied by 2) was used for dichotomous variables. The confidence interval for dichotomous variables was the asymptotic Wald confidence limits with continuity correction. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.4 (SS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographics

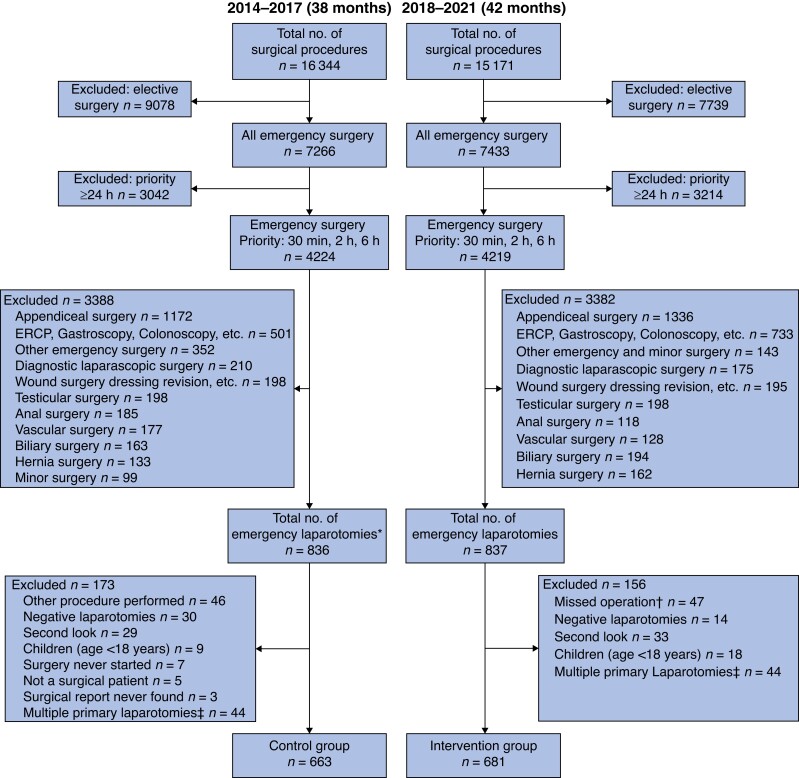

A total of 1344 patients who underwent emergency laparotomy were included in the study, 681 in the intervention group and 663 in the control group. The control phase lasted for 38 months (20 August 2014 to 20 October 2017) and the intervention phase for 42 months (25 February 2018 to 3 September 2021) (Fig. 1). The mean age in the intervention group was 67.6 years compared with 66.0 years in the control group. Both groups included a majority of women, and one or more of the listed co-morbidities occurred in 47.6 per cent of patients in the intervention group and 49.8 per cent of the controls. ASA III was the most common physical status grade (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart

*Including laparotomies that had a different procedure code initially. †Standardized protocol never used. ‡An individual can be included only once. ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

| Intervention (n = 681) |

Control (n = 663) |

P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.083 | ||

| ȃMean(s.d.) | 67.6(16.8) | 66.0(17.5) | |

| ȃMedian (range) | 71 (18–97) | 69 (18–96) | |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 317 : 364 | 302 : 361 | 0.75 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | n = 429 | n = 594 | 0.07 |

| ȃMean(s.d.) | 26.2(5.5) | 25.6(5.6) | |

| ȃMedian (range) | 25.4 (12.8–47.8) | 24.7 (11.1–67.5) | |

| Co-morbidity | |||

| ȃChronic obstructive lung disease | 67 (9.8) | 54 (8.1) | 0.32 |

| ȃIschaemic heart disease | 95 (14.0) | 80 (12.1) | 0.34 |

| ȃCongestive heart failure | 44 (6.5) | 59 (8.9) | 0.11 |

| ȃDiabetes | 84 (12.3) | 76 (11.5) | 0.68 |

| ȃChronic renal failure | 26 (3.8) | 30 (4.5) | 0.61 |

| ȃObesity | 99 (14.5) | 82 (12.4) | 0.28 |

| ȃSmoking | 80 (11.7) | 86 (13.0) | 0.55 |

| ȃNo co-morbidity | 357 (52.4) | 333 (50.2) | 0.45 |

| ASA physical status grade | 0.44 | ||

| ȃI | 48 (7.0) | 72 (10.9) | |

| ȃII | 254 (37.3) | 222 (33.5) | |

| ȃIII | 280 (41.1) | 264 (39.8) | |

| ȃIV | 79 (11.6) | 94 (14.2) | |

| ȃV | 20 (2.9) | 11 (1.7) | |

| Diagnosis at surgery | |||

| ȃPeritonitis | 0.015 | ||

| ȃȃNo peritonitis | 532 (78.1) | 489 (73.8) | |

| ȃȃPurulent | 38 (5.6) | 42 (6.3) | |

| ȃȃFaecal | 59 (8.7) | 48 (7.2) | |

| ȃȃOther | 52 (7.6) | 84 (12.7) | |

| ȃIntestinal ischaemia | 91 (13.4) | 76 (11.5) | 0.33 |

| ȃBowel obstruction | 0.049 | ||

| ȃȃNo obstruction | 273 (40.3) | 277 (42.0) | |

| ȃȃSmall intestine | 304 (44.9) | 314 (47.6) | |

| ȃȃColon | 100 (14.8) | 68 (10.3) | |

| ȃȃMissing | 4 | 4 | |

| ȃTrauma | 15 (2.2) | 20/661 (3.0) | 0.44 |

| ȃBleeding | 33 (4.8) | 41/659 (6.2) | 0.33 |

| ȃPerforation | 0.027 | ||

| ȃȃNo perforation | 469 (69.5) | 460 (69.4) | |

| ȃȃColon | 87 (12.9) | 57 (8.6) | |

| ȃȃSmall intestine | 62 (9.2) | 72 (10.9) | |

| ȃȃVentricle | 37 (5.5) | 56 (8.4) | |

| ȃȃAnastomosis | 20 (3.0) | 18 (2.7) | |

| ȃȃMissing | 6 | 0 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. *Between-groups Fisher’s exact test (lowest 1-sided P-value multiplied by 2) for dichotomous variables, Mantel–Haenszel χ2 test for ordered categorical variables, χ2 test for non-ordered categorical variables, and Fisher’s non-parametric permutation test for continuous variables.

Bowel obstruction in any form was present in 59.7 per cent of patients in the intervention group and in 58.0 per cent of controls, but there were more cases of colonic obstruction in the intervention group (14.8 versus 10.3 per cent) (Table 1). The rate of intestinal perforation was equally high in both groups, but peritonitis was more common in the control group. Intestinal ischaemia or gangrene was present in 13.4 per cent of patients in the intervention group and 11.5 per cent of controls.

Management

The time from notification of surgery to the start of operation was reduced from 3.80 to 3.22 h with use of the standardized protocol. Perioperative antibiotic use increased from 81.4 to 94.7 per cent (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intervention variables

| Intervention (n = 681) |

Control (n = 663) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Perioperative management | ||

| ȃPreoperative administration of antibiotics | 645 (94.7) | 524 of 644 (81.4) |

| ȃUse of epidural anaesthesia | 484 (71.1) | 444 (67.0) |

| ȃArterial line set up | 578 (84.9) | 244 (36.8) |

| ȃNoradrenaline (norephinephrine) used | 586 (86.3) | 474 (71.5) |

| ȃInduction of anaesthesia | ||

| ȃȃPropofol | 501 (79.0) | 550 (83.5) |

| ȃȃKetamine | 61 (9.6) | 60 (9.1) |

| ȃȃPropofol + ketamine | 72 (11.4) | 49 (7.4) |

| ȃȃMissing | 46 | 4 |

| ȃGoal-directed fluid therapy in theatre | 527 of 679 (77.6) | –* |

| ȃAnaesthesia complication | ||

| ȃȃNo | 601 (91.6) | 573 (87.2) |

| ȃȃAspiration | 11 (1.7) | 5 (0.8) |

| ȃȃOther complication | 44 (6.7) | 79 (12.0) |

| ȃȃMissing | 25 | 6 |

| Postoperative care in recovery unit (hours) | n = 563 | n = 545 |

| ȃMean(s.d.) | 6.85(4.51) | 7.64(4.67) |

| ȃMedian (range) | 5.22 (1.53–26.85) | 5.87 (0.43– 27.07) |

| Degree of urgency | ||

| ȃEmergency | 24 (3.5) | 23 (3.5) |

| ȃWithin 2 h | 372 (54.6) | 254 (38.3) |

| ȃWithin 6 h | 285 (41.9) | 386 (58.2) |

| Time from registration to start of surgery (hours) | ||

| ȃMean(s.d.) | 3.22(1.96) | 3.80(3.36) |

| ȃMedian (range) | 2.73 (−0.52 – 17.3) | 3.03 (0.08–54.12) |

| Total duration of operation (minutes) | ||

| ȃMean(s.d.) | 94.0(48.2) | 90.7(48.8) |

| ȃMedian (range) | 84 (12–335) | 81 (20–375) |

| Perioperative care—highest competence level in operating theatre | ||

| ȃSurgeons | ||

| ȃȃRegistrar | 34 (5.0) | 56 (8.5) |

| ȃȃSpecialist | 177 (26.2) | 183 (27.7) |

| ȃȃSenior consultant | 464 (68.7) | 421 (63.8) |

| ȃȃMissing | 6 | 3 |

| ȃAnaesthetists | ||

| ȃȃRegistrar | 207 (30.5) | 253 (38.4) |

| ȃȃSpecialist | 155 (22.8) | 127 (19.3) |

| ȃȃSenior consultant | 317 (46.7) | 278 (42.2) |

| ȃȃMissing | 2 | 5 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. *Data not available retrospectively.

Goal-directed fluid therapy was used in 77.6 per cent of operations in the intervention group, and haemodynamic monitoring with an arterial line was used in 84.9 and 36.8 per cent of patients in the protocol and control groups respectively (Table 2). Fewer anastomoses were fashioned in the intervention group (16.8 versus 22.5 per cent) (Table 3). Colonic resections were less common during the interventional phase than before (49.0 versus 59.4 per cent), whereas small bowel surgery was more common (46.0 versus 34.7 per cent).

Table 3.

Surgical procedures

| Intervention (n = 681) |

Control (n = 663) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Type of operation | ||

| ȃPrimary emergency laparotomy | 602 (88.4) | 572 (86.3) |

| ȃReoperation | 79 (11.6) | 91 (13.7) |

| ȃInitial laparoscopy | 45 (6.6) | –* |

| Bowel resections | 239 (35.1) | 239 (36) |

| Colon | 117 (49.0) | 142 (59.4) |

| ȃSmall intestine | 110 (46.0) | 83 (34.7) |

| ȃColon and small intestine | 12 (5.0) | 14 (5.9) |

| ȃMissing | 1 | 0 |

| Anastomoses | 114 of 679 (16.8) | 149 (22.5) |

| Stoma formation | 165 of 679 (24.3) | 169 (25.5) |

| Adhesiolysis | 314 of 678 (46.3) | 299 (45.1) |

| Excision of intra-abdominal organ | ||

| ȃNone | 669 (98.2) | 648 (97.7) |

| ȃPart of/whole stomach | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) |

| ȃSpleen | 5 (0.7) | 5 (0.8) |

| ȃPart of liver | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| ȃUterus and/or ovaries | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. *Data not available for controls.

Outcomes

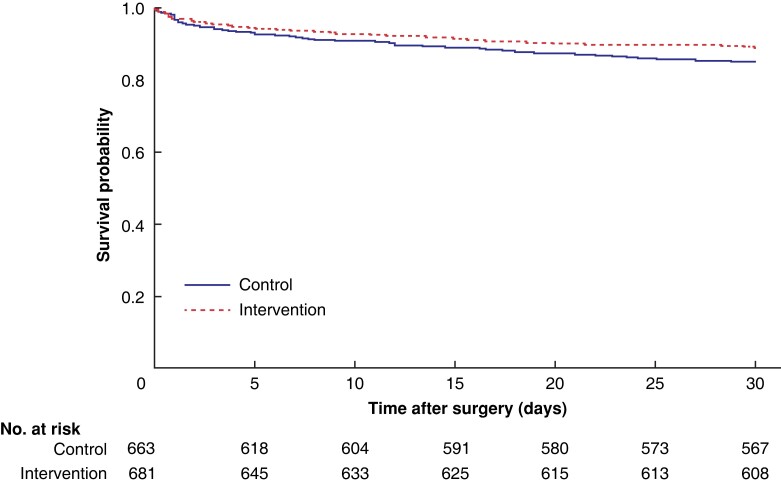

Patients in the protocol group had a lower 30-day mortality rate than controls (10.7 versus 14.5 per cent; P = 0.045) (Table 4 and Fig. 2). The mean duration of hospital stay was reduced to 10.2 days, and 19.2 per cent of patients in the intervention group required primary intensive care compared with 21.9 per cent of controls. Duration of ICU stay was reduced from a mean of 5.40 to 3.12 days with use of the standardized protocol, and the readmission rate was only 3.2 per cent, compared with 4.5 per cent in the control group. The rate of serious surgical complications (Clavien–Dindo grade IIIb–V) decreased (Table 5).

Table 4.

Primary efficacy analysis

| Intervention (n = 681) |

Control (n = 663) |

Adjusted GEE model† | Unadjusted GEE model‡ | Comparison between groups§ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR* | P | OR* | P | Difference* | P | |||

| Death within 30 days | 73 (10.7) | 96 (14.5) | 0.69 (0.47, 0.99) | 0.045 | 0.71 (0.51, 0.98) | 0.038 | 3.8 (0.1, 7.5) | 0.046 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated; *values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. †Analysed by GENMOD (General Mode) with generalized estimating equation (GEE) model, with binary outcome and link function logit adjusted for: age, intestinal ischaemia, faecal, purulent/other peritonitis, chronic obstructive lung disease, ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure, diabetes, obesity, smoking, ASA grade, and sex. ‡Analysed by GENMOD with GEE model, with binary outcome and link function logit. §The confidence interval for dichotomous variables is the asymptotic Wald confidence limits with continuity correction. Analysis by Fisher’s exact test (lowest 1-sided P value multiplied by 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing probability of survival up to 30 days after surgery

Table 5.

Secondary efficacy analyses adjusted

| Intervention (n = 681) |

Control (n = 663) |

Adjusted GEE model† | Unadjusted GEE model‡ | Comparison between groups§ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS mean/OR* | P | LS mean/OR* | P | Difference* | P | |||

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | ||||||||

| ȃMean(s.d.) | 10.2(13.3) | 11.9(13.0) | LS mean −1.90 (−3.27, −0.53) | 0.007 | LS mean 1.71 (−3.12, −0.30) | 0.0172 | −1.71 (−3.13, −0.31) | 0.017 |

| ȃMedian (range) | 7 (0–175.6) | 7.5 (0.1–112.9) | ||||||

| ICU care | 133 (19.5) | 145 (21.9) | OR 1.19 (0.88, 1.60) | 0.26 | OR 1.15 (0.89, 1.50) | 0.29 | 2.3 (−2.1, 6.8) | 0.32 |

| Duration of ICU care (days) | n = 133 | n = 145 | ||||||

| ȃMean(s.d.) | 3.12(5.97) | 5.40(8.34) | LS mean −2.35 (−4.07, −0.64) | 0.007 | LS mean −2.28 (−4.00, −0.57) | 0.009 | −2.28 (−4.01, −0.59) | 0.006 |

| ȃMedian (range) | 1.29 (0.02–53.54) | 2.15 (0.03– 62.02) | ||||||

| Readmission to ICU | 22 (3.2) | 30 (4.5) | OR 1.62 (0.90, 2.91) | 0.11 | OR 1.42 (0.81, 2.49) | 0.22 | 1.3 (−0.9, 3.5) | 0.28 |

| Surgical complications (Clavien–Dindo classification) | LS mean −0.16 (−0.23, −0.09) | <0.001 | LS mean −0.15 (−0.22, −0.08) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| ȃNo complications | 1 (0.1) | 7 (1.1) | ||||||

| ȃGrade I–IIIa | 494 (72.5) | 407 (61.4) | ||||||

| ȃGrade IIIb–IVb | 115 (16.9) | 141 (21.3) | ||||||

| ȃGrade V | 71 (10.4) | 108 (16.3) | ||||||

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated; *values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. †Analysed by GENMOD (General Mode) with GEE model, with binary outcome and link function logit adjusted for age, intestinal ischaemia, faecal, purulent/other peritonitis, chronic obstructive lung disease, ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure, diabetes, obesity, smoking, ASA grade, and sex. ‡Analysed by GENMOD with GEE model, with binary outcome and link function logit. §For dichotomous variables, the confidence interval is the asymptotic Wald confidence limits with continuity correction; analysis by Fisher’s exact test (lowest 1-sided P value multiplied by 2). LS (Least Squares), .

Discussion

A reduction in 30-day mortality, serious surgical complications, duration of hospital and ICU stay, and need for reoperation was observed in this study of protocol-driven standardized management of patients needing emergency laparotomy, compared with historical controls.

The time to first incision has been considered important in several studies and may be defined according to prehospital, preimaging, decision, and preoperative phases19. The SMASH care bundle activates from the middle of the decision phase and the preoperative phase when a notification of surgery is made. As a result, the management in earlier phases within emergency care was not included in the present study. A focus on the early phases could further improve the outcome.

The new standardized management protocol has several parts and checkpoints. One explanation for the improved results might be use of the standardized form and the close collaboration between surgeon and anaesthetist, and not one specific item. A data review indicated improvements in many of the management variables regarded beforehand as being important in the SMASH study care bundle17. These included a shorter time to the start of surgery and more patients treated with early antibiotics, generally higher level of clinical competence in the operating theatre, and the upgrade of postoperative care at recovery. However, data on goal-directed fluid therapy in the control group are missing, so the impact of this factor is difficult to assess.

The main aim of the SMASH study was to include every operation; one individual could be included more than once in order to reflect reality in clinical practice. The study population comprised generally severely ill patients who were often in need of repeated surgery. However, the total data were divided into two sets, one including all operations and the other with patients included only once. Comparing the analyses of the two sets revealed the same statistically significant differences in secondary outcome. However, as death was the primary endpoint, and this could happen only once, the data set comprising unique individuals was used in the analyses presented here. The data set including all operations is available in Tables S2–S6.

Among the weaknesses of this study, frailty was not examined. Evaluating frailty in elderly patients could help to identify those in need of adapted care and those who have a good prognosis despite old age20. In addition, the authors did not use any tools to estimate the risks associated with the surgical procedure. Today, there are a number of tools available to estimate these risks, such as P-POSSUM and American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program calculators. These tools were initially developed for elective situations, but adaptations for emergency laparotomy are available21. The single-centre design of the present study reduced the external validity and made the study interval longer. Undertaking this investigation as a multicentre study theoretically could have shortened the study time and provided better generalizability. On the other hand, such an approach could have led to reduced compliance with the protocol and increased complexity in data collection. Some data are missing for the control cohort because these patients were included retrospectively. No randomization of patients was undertaken in this study, even though there were indications that standardization of management could be beneficial to the patient without any risk.

The improved outcome can be explained in part by causes other than the new standardized protocol. The study covered a period of 8 years, during which the development of highly specialized medical care improved continuously. For example, anastomosis was less common in the intervention group, which could be explained by the development of damage control surgery. Furthermore, a better general standard of intensive care may have affected the results. In addition, the Hawthorne effect may have played a role. It has previously been stated that improvements can occur solely because clinicians are observed. The fact that the present interprofessional working group carried out monthly audits of all laparotomies could have led to this effect22. This study was designed in 2017 and the field of high-risk emergency abdominal surgery is developing continuously. Part 1 of an enhanced recovery after surgery programme for emergency laparotomy was published more recently23.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Kartus for overall support; J. Kliger for linguistic assistance; P. Ekman (Statistiska Konsultgruppen) for data analysis. The interprofessional group comprised C. Karlsson, K. Hedström, H. Strömberg, C. Algons, A. Karlsson, L. Novela Larsson, M. Eriksson, A. Olsson, A. Allegra, and G. Hagberg.

Contributor Information

Terje J Timan, University of Gothenburg, Sahlgrenska Academy, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Gothenburg, Sweden; Department of Research and Development, NU Hospital Group, Trollhättan, Sweden; Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, NU Hospital Group, Trollhättan, Sweden.

Ove Karlsson, University of Gothenburg, Sahlgrenska Academy, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Ninni Sernert, University of Gothenburg, Sahlgrenska Academy, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Gothenburg, Sweden; Department of Research and Development, NU Hospital Group, Trollhättan, Sweden.

Mattias Prytz, University of Gothenburg, Sahlgrenska Academy, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Gothenburg, Sweden; Department of Research and Development, NU Hospital Group, Trollhättan, Sweden; Department of Surgery, NU Hospital Group, Trollhättan, Sweden.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Research and Development, NU Hospital Group. Grants were received from the Local Research and Development Council Fyrbodal (VGFOUFBD-803271) and the Willhelm & Martina Lundgren Science Foundation (2019-2883). The two funding parties had no impact on the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of the results in the study.

Author contributions

Terje Timan (Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing E28093 review & editing), Ove Karlsson (Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing), Ninni Sernert (Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing), and Mattias Prytz (Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS online.

Data availability

The data sets analysed in this study and statistical code are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Havens JM, Peetz AB, Do WS, Cooper Z, Kelly E, Askari Ret al. The excess morbidity and mortality of emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;78:306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gale SC, Shafi S, Dombrovskiy VY, Arumugam D, Crystal JS. The public health burden of emergency general surgery in the United States: a 10-year analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample—2001 to 2010. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;77:202–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ogola GO, Gale SC, Haider A, Shafi S. The financial burden of emergency general surgery: national estimates 2010 to 2060. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:444–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peden C, Scott MJ. Anesthesia for emergency abdominal surgery. Anesthesiol Clin 2015;33:209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer Ret al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:304–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aggarwal G, Peden CJ, Mohammed MA, Pullyblank A, Williams B, Stephens Tet al. Evaluation of the collaborative use of an evidence-based care bundle in emergency laparotomy. JAMA Surg 2019;154:e190145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Al-Temimi MH, Griffee M, Enniss TM, Preston R, Vargo D, Overton Set al. When is death inevitable after emergency laparotomy? Analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. J Am Coll Surg 2012;215:503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barazanchi AWH, Xia W, MacFater W, Bhat S, MacFater H, Taneja Aet al. Risk factors for mortality after emergency laparotomy: scoping systematic review. ANZ J Surg 2020;90:1895–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huddart S, Peden CJ, Swart M, McCormick B, Dickinson M, Mohammed MAet al. Use of a pathway quality improvement care bundle to reduce mortality after emergency laparotomy. Br J Surg 2015;102:57–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saunders DI, Murray D, Pichel AC, Varley S, Peden CJ. Variations in mortality after emergency laparotomy: the first report of the UK Emergency Laparotomy Network. Br J Anaesth 2012;109:368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shapter SL, Paul MJ, White SM. Incidence and estimated annual cost of emergency laparotomy in England: is there a major funding shortfall? Anaesthesia 2012;67:474–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tengberg LT, Bay-Nielsen M, Bisgaard T, Cihoric M, Lauritsen ML, Foss NB. Multidisciplinary perioperative protocol in patients undergoing acute high-risk abdominal surgery. Br J Surg 2017;104:463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vester-Andersen M, Lundstrom LH, Moller MH, Waldau T, Rosenberg J, Moller AM. Mortality and postoperative care pathways after emergency gastrointestinal surgery in 2904 patients: a population-based cohort study. Br J Anaesth 2014;112:860–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lasithiotakis K, Kritsotakis EI, Kokkinakis S, Petra G, Paterakis K, Karali GAet al. The Hellenic Emergency Laparotomy Study (HELAS): a prospective multicentre study on the outcomes of emergency laparotomy in Greece. World J Surg 2023;;47:130–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hashmi ZG, Jarman MP, Havens JM, Scott JW, Goralnick E, Cooper Zet al. Quantifying lives lost due to variability in emergency general surgery outcomes: why we need a national emergency general surgery quality improvement program. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021;90:685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. NELA Project team. Year 7 Full Report of the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit. http://nela.org.uk/reports. November 2021.

- 17. Timan TJ, Sernert N, Karlsson O, Prytz M. SMASH standardised perioperative management of patients operated with acute abdominal surgery in a high-risk setting. BMC Res Notes 2020;13:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jansson Timan T, Hagberg G, Sernert N, Karlsson O, Prytz M. Mortality following emergency laparotomy: a Swedish cohort study. BMC Surg 2021;21:322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murray V, Burke JR, Hughes M, Schofield C, Young A. Delay to surgery in acute perforated and ischaemic gastrointestinal pathology: a systematic review. BJS Open 2021;5:zrab072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O. A scoping review of the clinical frailty scale. BMC Geriatr 2020;20:393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hunter Emergency Laparotomy Collaborator Group . High-risk emergency laparotomy in Australia: comparing NELA, P-POSSUM, and ACS-NSQIP calculators. J Surg Res 2020;246:300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garrouste-Orgeas M, Soufir L, Tabah A, Schwebel C, Vesin A, Adrie Cet al. A multifaceted program for improving quality of care in intensive care units: IATROREF study. Crit Care Med 2012;40:468–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peden CJ, Aggarwal G, Aitken RJ, Anderson ID, Bang Foss N, Cooper Zet al. Guidelines for perioperative care for emergency laparotomy Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations: part 1—preoperative: diagnosis, rapid assessment and optimization. World J Surg 2021;45:1272–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets analysed in this study and statistical code are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Havens JM, Peetz AB, Do WS, Cooper Z, Kelly E, Askari Ret al. The excess morbidity and mortality of emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;78:306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gale SC, Shafi S, Dombrovskiy VY, Arumugam D, Crystal JS. The public health burden of emergency general surgery in the United States: a 10-year analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample—2001 to 2010. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;77:202–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ogola GO, Gale SC, Haider A, Shafi S. The financial burden of emergency general surgery: national estimates 2010 to 2060. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:444–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peden C, Scott MJ. Anesthesia for emergency abdominal surgery. Anesthesiol Clin 2015;33:209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer Ret al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:304–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aggarwal G, Peden CJ, Mohammed MA, Pullyblank A, Williams B, Stephens Tet al. Evaluation of the collaborative use of an evidence-based care bundle in emergency laparotomy. JAMA Surg 2019;154:e190145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Al-Temimi MH, Griffee M, Enniss TM, Preston R, Vargo D, Overton Set al. When is death inevitable after emergency laparotomy? Analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. J Am Coll Surg 2012;215:503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barazanchi AWH, Xia W, MacFater W, Bhat S, MacFater H, Taneja Aet al. Risk factors for mortality after emergency laparotomy: scoping systematic review. ANZ J Surg 2020;90:1895–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huddart S, Peden CJ, Swart M, McCormick B, Dickinson M, Mohammed MAet al. Use of a pathway quality improvement care bundle to reduce mortality after emergency laparotomy. Br J Surg 2015;102:57–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saunders DI, Murray D, Pichel AC, Varley S, Peden CJ. Variations in mortality after emergency laparotomy: the first report of the UK Emergency Laparotomy Network. Br J Anaesth 2012;109:368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shapter SL, Paul MJ, White SM. Incidence and estimated annual cost of emergency laparotomy in England: is there a major funding shortfall? Anaesthesia 2012;67:474–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tengberg LT, Bay-Nielsen M, Bisgaard T, Cihoric M, Lauritsen ML, Foss NB. Multidisciplinary perioperative protocol in patients undergoing acute high-risk abdominal surgery. Br J Surg 2017;104:463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vester-Andersen M, Lundstrom LH, Moller MH, Waldau T, Rosenberg J, Moller AM. Mortality and postoperative care pathways after emergency gastrointestinal surgery in 2904 patients: a population-based cohort study. Br J Anaesth 2014;112:860–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lasithiotakis K, Kritsotakis EI, Kokkinakis S, Petra G, Paterakis K, Karali GAet al. The Hellenic Emergency Laparotomy Study (HELAS): a prospective multicentre study on the outcomes of emergency laparotomy in Greece. World J Surg 2023;;47:130–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hashmi ZG, Jarman MP, Havens JM, Scott JW, Goralnick E, Cooper Zet al. Quantifying lives lost due to variability in emergency general surgery outcomes: why we need a national emergency general surgery quality improvement program. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021;90:685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. NELA Project team. Year 7 Full Report of the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit. http://nela.org.uk/reports. November 2021.

- 17. Timan TJ, Sernert N, Karlsson O, Prytz M. SMASH standardised perioperative management of patients operated with acute abdominal surgery in a high-risk setting. BMC Res Notes 2020;13:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jansson Timan T, Hagberg G, Sernert N, Karlsson O, Prytz M. Mortality following emergency laparotomy: a Swedish cohort study. BMC Surg 2021;21:322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murray V, Burke JR, Hughes M, Schofield C, Young A. Delay to surgery in acute perforated and ischaemic gastrointestinal pathology: a systematic review. BJS Open 2021;5:zrab072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O. A scoping review of the clinical frailty scale. BMC Geriatr 2020;20:393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hunter Emergency Laparotomy Collaborator Group . High-risk emergency laparotomy in Australia: comparing NELA, P-POSSUM, and ACS-NSQIP calculators. J Surg Res 2020;246:300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garrouste-Orgeas M, Soufir L, Tabah A, Schwebel C, Vesin A, Adrie Cet al. A multifaceted program for improving quality of care in intensive care units: IATROREF study. Crit Care Med 2012;40:468–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peden CJ, Aggarwal G, Aitken RJ, Anderson ID, Bang Foss N, Cooper Zet al. Guidelines for perioperative care for emergency laparotomy Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations: part 1—preoperative: diagnosis, rapid assessment and optimization. World J Surg 2021;45:1272–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]