Abstract

Background

The risk of death after surgery for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma is high; nearly one in every five patients dies within 90 days after surgery. When the oncological benefit is limited, a high-risk resection may not be justified. This retrospective cohort study aimed to create two preoperative prognostic models to predict 90-day mortality and overall survival (OS) after major liver resection for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Methods

Separate models were built with factors known before surgery using multivariable regression analysis for 90-day mortality and OS. Patients were categorized in three groups: favourable profile for surgical resection (90-day mortality rate below 10 per cent and predicted OS more than 3 years), unfavourable profile (90-day mortality rate above 25 per cent and/or predicted OS below 1.5 years), and an intermediate group.

Results

A total of 1673 patients were included. Independent risk factors for both 90-day mortality and OS included ASA grade III–IV, large tumour diameter, and right-sided hepatectomy. Additional risk factors for 90-day mortality were advanced age and preoperative cholangitis; those for long-term OS were high BMI, preoperative jaundice, Bismuth IV, and hepatic artery involvement. In total, 294 patients (17.6 per cent) had a favourable risk profile for surgery (90-day mortality rate 5.8 per cent and median OS 42 months), 271 patients (16.2 per cent) an unfavourable risk profile (90-day mortality rate 26.8 per cent and median OS 16 months), and 1108 patients (66.2 per cent) an intermediate risk profile (90-day mortality rate 12.5 per cent and median OS 27 months).

Conclusion

Preoperative risk models for 90-day mortality and OS can help identify patients with resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma who are unlikely to benefit from surgical resection. Tailored shared decision-making is particularly essential for the large intermediate group.

When the oncological benefit is limited, a high-risk resection may be not be justified. Two preoperative prognostic models were created to predict 90-day mortality and survival after major liver resection for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. These can help identify patients with resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma who are unlikely to benefit from surgical resection.

Introduction

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA) is the most common malignancy of the biliary tree1. In Western countries, the incidence of pCCA is about 1–2 patients per 100 0002,3. The aim of surgery is resection with negative surgical margins4,5. Surgical resection is challenging because the tumour arises at or near the biliary confluence in proximity to the vascular inflow structures of the liver. Therefore, surgical resection typically requires major liver resection with extrahepatic bile duct resection, and often reconstruction of the portal vein and/or hepatic artery. The overall 90-day mortality rate after resection of pCCA is about 12 per cent in large nationwide Western studies6. This postoperative mortality ranks as one of the highest in surgical oncology. The most common cause of postoperative death is liver failure, typically owing to a small liver remnant aggravated by infectious complications7.

Many studies of surgery for pCCA referred to resection as the only potentially curative treatment for patients with pCCA. The chance of cure after resection, however, was only 15 per cent for patients with extrahepatic biliary tract cancer8. The 10-year recurrence-free survival rate after resection of pCCA was only 5 per cent9. Patients with lymph node metastasis rarely experience long-term survival10. The patient and multidisciplinary team should determine whether the predicted long-term overall survival (OS) after resection justifies the short-term surgical risk. Weighing these two outcomes requires consideration of factors for surgical risk known before operation (for example ASA fitness grade) and for OS (for example hepatic artery involvement). Several studies11–13 developed prognostic models for either short- or long-term postoperative outcomes. These models, however, are mostly unsuitable for preoperative decision-making because they include factors such as margin status that become available only after surgical resection.

The aim of this study was to develop two prognostic models with factors known before surgery for 90-day mortality and long-term OS after resection of pCCA. The individually predicted 90-day mortality and long-term OS can together guide the decision whether the predicted long-term OS justifies the predicted 90-day mortality.

Methods

Patients from the collaborative multicentre international database managed by the International Hepato-Pancreato Biliary Association (IHPBA) Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma Collaboration Group, undergoing a major liver resection for pathologically confirmed pCCA between 2000 and 2019, were included in this retrospective cohort study. A total of 25 participating centres worldwide included a median of 79 (i.q.r. 42–100) consecutive patients. Each centre collected data using a standardized and deidentified data file. Patient and tumour characteristics, clinical parameters, and laboratory results were collected retrospectively from medical archives. Patients were excluded from the present study if they had undergone minor liver resection or extrahepatic bile duct resection only, associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy, had unresectable disease at surgical exploration, R2 resection margins, or had undergone liver transplantation. Ethical approval and individual informed consent were waived by the Institutional Medical Ethics Committee of the Amsterdam University Medical Centre.

Patient work-up and management

Variations in surgical expertise, hospital volume, and standard of care across hospitals and over time were accepted owing to the retrospective nature of the study and long inclusion period. Most patients underwent preoperative endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage of the anticipated future liver remnant (FLR). When the anticipated FLR was considered inadequate, patients underwent portal vein embolization (PVE).

Definitions and outcomes

A major liver resection was defined as resection of at least three Couinaud segments. Resection of fewer than three Couinaud segments or an extrahepatic bile duct resection only were considered minor resections. Preoperative cholangitis was defined by the presence of fever, abdominal pain, or leucocytosis requiring biliary drainage, as defined previously in the DRAINAGE trial14. Postoperative mortality was defined as death within 90 days after resection. OS was defined as the interval between surgery and the date of death or last follow-up. Tumour margins were considered free (R0 resection) when all resection and circumferential margins were free from tumour on pathological examination. Hepatic artery or portal vein invasion was defined by the presence of abutment of at least 180° on radiological imaging (CT and/or MRI).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with R 3.5.1 (https://cran.r-project.org). Continuous data are reported as median (i.q.r.), and were compared using Mann–Whitney U tests. Categorical parameters are presented as counts and percentages, with analysis using χ2 tests. The TRIPOD recommendations were followed for the development of this prediction model (Supplementary material)15. Multivariable models for predicting 90-day mortality were constructed using logistic regression analyses, with outcomes reported as linear predictors for comparing magnitude of correlation and ORs with corresponding 95 per cent confidence intervals. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were constructed for predicting OS, with outcomes reported as linear predictors for comparing magnitude of correlation and HRs with corresponding 95 per cent confidence intervals. Only factors that are available before surgery were considered for both models. Factors were included in multivariable models based on backwards selection with a cut-off of P < 0.050. Factors predictive of 90-day mortality were also included in the long-term survival model and vice versa. Model discrimination was presented as Harrell’s C-index. Missing data were imputed using the mice package for R 3.5.1. A sensitivity analysis was undertaken for the last 6 years of the inclusion period (2014–2019). P values were two-tailed and P < 0.050 considered to be statistically significant.

Individual patients were categorized in three groups based on arbitrary chosen cut-offs following expert consensus on the predicted outcomes of both models: favourable profile for surgical resection (90-day mortality rate below 10 per cent and predicted OS above 3 years), unfavourable profile (90-day mortality risk above 25 per cent and/or predicted OS below 1.5 years), and the intermediate group.

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1. In total, 2136 patients were identified in the registry; 463 patients were excluded for the following reasons: no major liver resection (227), diagnosis other than pCCA on pathological examination of the resected specimen (201), surgical resection took place before the year 2000 (21), and macroscopically unresectable disease (R2 resection, 14). This led to 1673 eligible patients in the present study. A total of 1260 patients (79.5 per cent) presented with jaundice at first presentation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with pathologically confirmed perihilar cholangiocarcinoma

| No. of patients (n = 1673)* | |

|---|---|

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 962 : 711 |

| Age (years), median (i.q.r.) | 65 (56–72) |

| ≥70 | 481 (33.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (i.q.r.) | 24.9 (22.4–27.3) |

| WHO grade | |

| ȃ0 | 371 (54.2) |

| ȃ1 | 258 (37.7) |

| ȃ2 | 51 (7.4) |

| ȃ3 | 5 (0.7) |

| Jaundice at presentation | 1260 (79.5) |

| ASA fitness grade | |

| ȃI–II | 942 (62.5) |

| ȃIII–IV | 565 (37.5) |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 47 (4.0) |

| Preoperative biliary drainage | 1389 (83.1) |

| Preoperative cholangitis | 338 (22.3) |

| Bismuth–Corlette classification | |

| ȃI–III | 1210 (73.5) |

| ȃIV | 437 (26.5) |

| Portal vein invasion† | 428 (40.3) |

| Hepatic artery invasion† | 259 (24.5) |

| Tumor diameter (cm), median (i.q.r.) | 2.7 (2.0–4.0) |

| Portal vein embolization | 131 (16.1) |

| Surgery | |

| ȃLeft hemihepatectomy | 523 (31.3) |

| ȃLeft extended hemihepatectomy | 273 (16.3) |

| ȃRight Hemihepatectomy | 307 (18.4) |

| ȃRight extended hemihepatectomy | 570 (34.1) |

| Portal vein reconstruction | 529 (33.4) |

| Hepatic artery reconstruction | 54 (3.4) |

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | 22 (1.5) |

| R1 resection margin | 553 (33.3) |

| AJCC T category‡ | |

| ȃT1–2 | 1052 (64.6) |

| ȃT3–4 | 577 (35.4) |

| Lymph node metastases | |

| ȃN0 | 929 (56.8) |

| ȃN1 | 663 (40.6) |

| ȃN2 | 40 (2.4) |

| Poor tumour differentation | 376 (24.5) |

| Perineural invasion | 1113 (77.0) |

*Values are n (%) unless indicated otherwise. †Portal vein or hepatic artery invasion was defined as tumour contact of at least 180° on imaging. ‡AJCC 7th edition. T1–2: Bismuth type 1–3 without any vascular involvement.

The majority of patients underwent preoperative biliary drainage (1389, 83.0 per cent). Preoperative cholangitis occurred in 338 patients (22.3 per cent). Preoperative PVE was performed in 131 patients (16.1 per cent). Left hemihepatectomy (523, 31.3 per cent) and right extended hemihepatectomy (570, 34.1 per cent) were most commonly performed. Tumour-free margins (R0) were found in 1106 patients (66.7 per cent). Lymph node metastasis was classified as N1 in 663 patients (40.6 per cent) and N2 in 40 (2.4 per cent) (7th edition AJCC staging).

Ninety-day mortality

The 90-day mortality rate for the entire cohort was 13.6 per cent (228 of 1673). In the group aged less than 70 years, the 90-day mortality rate was 11.2 per cent (108 of 964), compared with 18.1 per cent (87 of 481) among those aged 70 years or more. Patients who died within 90 days were more likely to have an ASA grade of III or IV (49.0 versus 35.8 per cent; P < 0.001), preoperative cholangitis (28.9 versus 21.3 per cent; P = 0.017), or a portal vein reconstruction (41.0 versus 32.3 per cent; P = 0.013). The 90-day mortality rate was the highest after extended right hemihepatectomy (105 of 570, 18.4 per cent), followed by right hemihepatectomy (51 of 307, 16.6 per cent), extended left hemihepatectomy (29 of 273, 10.6 per cent), and left hemihepatectomy (43 of 523, 8.2 per cent).

Independent risk factors for 90-day mortality were: age (OR 1.04, 95 per cent c.i. 1.03 to 1.06), ASA grade III–IV (OR 1.46, 1.08 to 1.98), preoperative cholangitis (OR 1.61, 1.15 to 2.25), tumour diameter (OR 1.03, 1.01 to 1.05), and right-sided hepatectomy (OR 1.74, 1.24 to 2.45) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses of 90-day mortality

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | P | OR | P | |

| Male sex | 1.18 (0.89, 1.58) | 0.255 | ||

| Age (years) | 1.04 (1.03, 1.06) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.03, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 0.985 | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.733 |

| Jaundice at presentation | 1.40 (0.97, 2.06) | 0.079 | 1.14 (0.76, 1.75) | 0.531 |

| ASA grade III–IV | 1.71 (1.29, 2.26) | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.08, 1.98) | 0.014 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 0.62 (0.26, 1.28) | 0.239 | ||

| Preoperative biliary drainage | 1.41 (0.95, 2.15) | 0.100 | ||

| Preoperative cholangitis | 1.60 (1.17, 2.17) | 0.003 | 1.61 (1.15, 2.25) | 0.005 |

| Bismuth type IV | 1.19 (0.87, 1.61) | 0.274 | 1.18 (0.85, 1.63) | 0.327 |

| Hepatic artery involvement | 1.13 (0.82, 1.55) | 0.452 | 1.23 (0.86, 1.73) | 0.244 |

| Tumour diameter (cm) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 0.002 |

| Right-sided hepatectomy | 2.18 (1.62, 2.94) | <0.001 | 1.74 (1.24, 2.45) | 0.001 |

| Extended hepatectomy | 1.48 (1.12, 1.97) | 0.007 | ||

| C-index for model | 0.685 | |||

Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

Long-term overall survival

Median survival was 27 (95 per cent c.i. 24.6 to 28.8) months and the 5-year OS rate was 17 per cent. Median OS was 33 months after left hemihepatectomy, 27 months after left extended hemihepatectomy, 25 months after right hemihepatectomy, and 21 months after right extended hemihepatectomy. Men had worse median OS than women (25 versus 30 months; P = 0.016). Patients with worse median OS were more likely to have an ASA grade of III–IV (23 months versus 30 months for ASA I–II; P < 0.001), Bismuth IV tumours (24 months versus 28 months for Bismuth I–III; P = 0.001), hepatic artery invasion (20 versus 28 months; P < 0.001), or jaundice at presentation (24 versus 42 months; P < 0.001).

Independent poor prognostic factors for OS were: BMI (hazard ratio 1.02, 95 per cent c.i. 1.00 to1.03), jaundice at presentation (HR 1.43, 1.21 to 1.69), ASA grade III to IV (HR 1.34; 1.17 to 1.54), Bismuth type IV tumour (HR 1.20, 1.05 to 1.37), hepatic artery involvement (HR 1.27, 1.09 to 1.50), tumour diameter (HR 1.02, 1.00 to1.03), and right-sided hepatectomy (HR 1.27, 1.13 to 1.44) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable survival analyses of factors associated with overall survival of patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P | HR | P | |

| Male sex | 1.16 (1.03, 1.30) | 0.016 | ||

| Age (years) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.025 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.115 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | 0.060 | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | 0.022 |

| Jaundice at presentation | 1.52 (1.30, 1.78) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.21, 1.69) | <0.001 |

| ASA grade III–IV | 1.39 (1.23, 1.58) | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.17, 1.54) | <0.001 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 0.95 (0.67, 1.34) | 0.754 | ||

| Preoperative biliary drainage | 1.21 (1.03, 1.42) | 0.021 | ||

| Preoperative cholangitis | 1.19 (1.02, 1.37) | 0.025 | 1.16 (0.99, 1.36) | 0.069 |

| Bismuth type IV | 1.23 (1.08, 1.41) | 0.001 | 1.20 (1.05, 1.37) | 0.009 |

| Hepatic artery involvement | 1.36 (1.14, 1.62) | <0.001 | 1.27 (1.09, 1.50) | 0.002 |

| Tumour diameter (cm) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | 0.013 |

| Right-sided hepatectomy | 1.26 (1.12, 1.42) | <0.001 | 1.27 (1.13, 1.44) | <0.001 |

| Extended hepatectomy | 1.26 (1.12, 1.42) | <0.001 | ||

| C-index for model | 0.601 | |||

Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

Long-term overall survival versus 90-day mortality

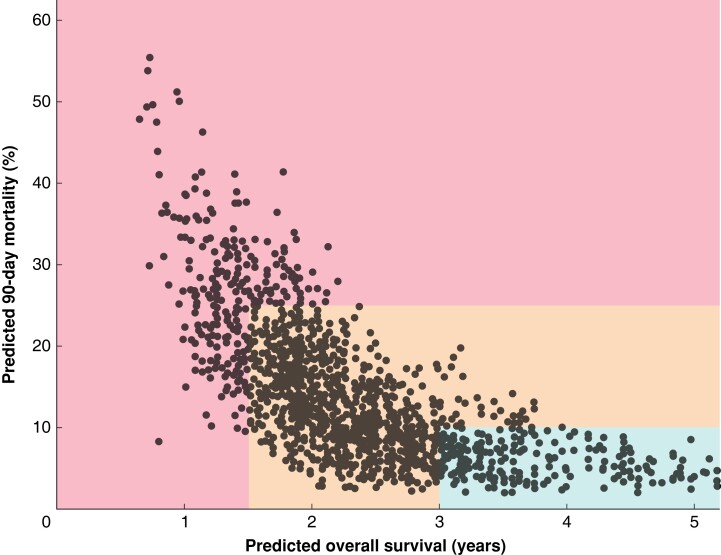

Figure 1 shows both the predicted 90-day postoperative mortality rate and the predicted OS for each patient. A favourable risk profile for surgery was found for 294 patients (17.6 per cent) with a 90-day mortality rate of 5.8 per cent and median OS of 42 months; an intermediate risk profile was found for 1108 patients (66.2 per cent) with a 90-day mortality rate of 12.5 per cent and median OS of 27 months; and an unfavourable risk profile was found for 271 patients (16.2 per cent) with a 90-day mortality rate of 26.8 per cent and median OS of 16 months.

Fig. 1.

Predicted 90-day mortality versus predicted overall survival

Patients in the green zone (favourable risk profile for surgery) all had a predicted overall survival (OS) exceeding 3 years and a predicted 90-day mortality rate below 10 per cent. Patients in the red zone (unfavourable risk profile for surgery) had a predicted OS below 1.5 years and/or a predicted 90-day mortality rate above 25 per cent. Patients in the orange zone had an intermediate risk profile. A calculator for predicting both long-term OS and 90-day mortality for the individual patient is available at https://dhoppener.shinyapps.io/risk_vs_harm_app/. The following are examples of actual patients in each zone. In the middle of the green zone was a 62-year-old woman with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 and ASA II. She presented with painless jaundice, and underwent endoscopic biliary drainage. She had a 4.5-cm Bismuth II perihilar cholangiocarcinoma without hepatic arterial involvement that required a left hemihepatectomy. In the middle of the orange zone was a 79-year-old woman with a BMI of 23 kg/m2 and ASA II. She presented with preoperative jaundice, and underwent endoscopic and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. She had a 1.2-cm Bismuth II perihilar cholangiocarcinoma without hepatic arterial involvement that required a left extended hemihepatectomy. In the middle of the red zone was a 78-year-old man with a BMI of 24 kg/m2 and ASA IV. He presented with painless jaundice and underwent endoscopic biliary drainage. He had a 2-cm Bismuth IV perihilar cholangiocarcinoma with hepatic arterial involvement that required a right hemihepatectomy.

In the sensitivity analysis, HRs and ORs were comparable to those for the complete cohort, with slightly better C-index values. A calculator for predicting both long-term OS and 90-day mortality for the individual patient is available at https://dhoppener.shinyapps.io/risk_versus_harm_app/.

Discussion

In this study, two preoperative prognostic models were developed for predicting 90-day mortality and long-term OS after resection of pCCA. Patients were categorized in three groups based on predicted risk for both outcomes. A favourable risk profile (90-day mortality rate below 10 per cent and predicted OS above 3 years) was observed in 17.6 per cent of patients, reflecting those who were likely to benefit from surgical resection. An unfavourable risk profile (90-day mortality rate above 25 per cent and/or predicted OS below 1.5 years) was found in 16.2 per cent of patients, who were unlikely to benefit from surgery. An intermediate risk profile, observed in 66.2 per cent of patients, would require a more tailored approach balancing patient preferences regarding surgical risk and long-term OS.

A recent systematic review6 reported a pooled 90-day mortality rate of 12 per cent after major liver resection for pCCA in Western countries. This is comparable to the 90-day mortality rate of 13.6 per cent in the present study, which excluded patients who underwent extrahepatic bile duct resection only. Postoperative mortality after resection for pCCA is mostly due to posthepatectomy liver failure16,17. Reduction in liver failure and mortality can be achieved by adequate biliary drainage and preoperative augmentation of the FLR with PVE18. PVE was performed in about 60 per cent of patients in a large Asian study19, with a low postoperative mortality rate of 2 per cent. Only 16 per cent of patients in the present study underwent PVE. More liberal use of PVE may increase the FLR volume, and decrease postoperative liver failure and mortality20.

Surgical resection of pCCA offers the best chance of long-term survival. The 5-year OS rate of 17 per cent and median OS of 27 months in this study is comparable to values in other series. Published median OS after resection of pCCA ranged from 20 to 40 months21, with 5-year OS rates ranging from 10 to 30 per cent1. Although long-term survival after resection of pCCA remains poor, the median OS with palliative systemic chemotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer was only 11 months, with no survivors beyond 3 years22. However, these patients had advanced disease. OS in patients with resectable pCCA receiving palliative chemotherapy would probably be better. Nevertheless, the potential survival benefit of surgical resection should be carefully balanced against the risk of 90-day mortality. In addition to postoperative mortality, surgical resection is associated with considerable morbidity, with prolonged hospital stay and recovery after discharge.

The influence of (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy was not included in this preoperative risk evaluation. Only a few small retrospective studies of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for biliary tract cancer are available23. These studies mainly included patients with locally advanced or borderline resectable biliary tract cancer, for whom neoadjuvant chemotherapy might offer downstaging. A currently ongoing phase II trial, the NACRAC study24, may provide insight into whether neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy (gemcitabine + external beam radiation) can affect postoperative survival or not. The possibility of starting adjuvant chemotherapy is largely dependent on the postoperative recovery. The potential benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy is limited, as demonstrated by the BILCAP trial (capecitabine versus observation; HR 0.80, 95 per cent c.i. 0.63 to 1.04), the BCAT trial (gemcitabine versus observation; HR 1.01, 0.70 to 1.45), and the Prodige trial (gemcitabine and oxaliplatin versus observation; HR 1.08, 0.70 to 1.66)25–27.

Patients (and surgeons) might differ regarding the 90-day mortality risk that they believe would justify resection. This study assumed an arbitrary predicted 90-day mortality risk of 25 per cent above which a resection seems rarely justified. Similarly, patients (and surgeons) might also differ regarding the long-term OS that they believe would justify the surgical risks. This study assumed a predicted OS of 18 months below which a resection seems rarely justified. In surgical oncology, unfavourable patient factors and more advanced disease are often associated with both poor short- and long-term outcomes. In the present study, ASA grade III–IV, tumour diameter, and right-sided resection were associated with both worse 90-day mortality and worse long-term OS. Future research should investigate how patients and surgeons both balance surgical risk and long-term OS. Moreover, patients rely primarily on the information from the surgeon. Adequate use of shared decision-making can increase patient satisfaction and decrease decisional regret28.

Several staging systems for pCCA are used to guide treatment including the AJCC, Bismuth–Corlette, and Blumgart systems29–31. However, these staging systems consider only anatomical aspects of the tumour. To address these limitations, several prognostic models have been developed for survival after surgical resection of pCCA12,32–35. These models typically include margin status, nodal status, and tumour differentiation. Although these variables are strong independent prognostic factors, they are available only after surgical resection and cannot therefore be used for preoperative decision-making.

This study should be viewed in the light of several limitations. First, inherent to all retrospective studies, the diagnosis and treatment of patients differed between the 25 participating centres and changed over time during the two-decade inclusion period. However, to achieve its aim, this study required a very large cohort that was otherwise not available. Second, about one-third of patients with resectable pCCA on imaging do not undergo resection because of occult metastatic disease or more advanced disease. These patients were not included in this multicentre cohort. Therefore, the predicted OS and 90-day mortality apply only to patients who do undergo resection. Most studies presented outcomes only for patients with resected pCCA. Studies including all patients with resectable pCCA (for example the DRAINAGE and INTERCPT trials) reported a much higher perioperative mortality rate14,36. The proportion of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) was small (4 per cent), as most patients with PSC underwent liver transplantation and were therefore not included in this cohort of resections. Finally, patients with a suspected diagnosis of pCCA but a different diagnosis after resection (5–10 per cent) were not included in this multicentre cohort37. In the preoperative setting, the final diagnosis is not known. Consequently, observed OS will be slightly longer than predicted by the model because of patients with non-malignant disease.

Collaborators

Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma Collaboration Group: T.M. van Gulik, L.C. Franken, J.I. Erdmann, B.M. Zonderhuis, G. Kazemier, L.E. Nooijen (Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands); S.K. Maithel (Emory University, Atlanta, USA); J.L.A. van Vugt, J.N.M. IJzermans, R.J. Porte (Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands); L. Aldrighetti, R. Marino (IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital, Milan, Italy); K.J. Roberts (Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, UK); M.C. Giglio, R. Troisi (Ghent University Hospital and Medical School, Ghent, Belgium); M. Malago, S. van Laarhoven (Royal Free Hospital, University College London, London, UK); H. Lang, F. Bartsch, R. Margies (Universitätsmedizin Mainz, Mainz, Germany); R. Alikhanov, M. Efanov (Moscow Clinical Scientific Center, Moscow, Russia); A. Guglielmi, (University School of Medicine of Verona, Verona, Italy); H.Z. Malik, L.M. Quinn (University Hospital Aintree, Liverpool, UK); C. Gomez-Gavara, C. Dopazo (all D'Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain); E. de Savornin Lohman, P. de Reuver (Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands); S.W.M. Olde Damink, S. Bouwense (Maastrischt University Medical Center, Maastricht, the Netherlands); E. Sparrelid, H. Jansson, S. Glig (Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden); M. Schmelzle, C. Benzing (Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany); M. Serenari, M. Ravaioli (l'Università di Bologna, Bologna, Italy); J. Rolinger, I. Capobianco (Tübingen University Hospital, Tübingen, Germany); E. Schadde, J. Heil (Cantonal Hospital Winterthur, Zurich, Switserland); Q.I. Molenaar, J. Hagendoorn (University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands); W.O.Bechstein, T.A. Nguyen (Universitätsklinikum Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany); J. Geers (University Hospital KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium); P. Lodge, A. Hakeem, R. Prasad (St. James's University Hospital, Leeds, UK); J. Bednarsch (University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany); F. Hoogwater, M.A. de Boer (University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

P.B.O and B.G.K. are joint senior authors.

Contributor Information

Anne-Marleen van Keulen, Department of Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Stefan Buettner, Department of Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Joris I Erdmann, Department of Surgery, Amsterdam University Medical Centres, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Johann Pratschke, Department of Surgery, Campus Charité Mitte, Campus Virchow-Klinikum-Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

Francesca Ratti, Division of Hepatobiliary Surgery, IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital, Milan, Italy.

William R Jarnagin, Department of Surgery, Hepatopancreatobiliary Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Andreas A Schnitzbauer, Department of General, Visceral, Transplant and Thoracic Surgery, University Hospital Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany.

Hauke Lang, Department of General, Visceral and Transplantation Surgery, University Hospital of Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

Andrea Ruzzenente, Department of Surgery, Unit of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery, University of Verona Medical School, Verona, Italy.

Silvio Nadalin, Department of General and Transplant Surgery, University Hospital Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany.

Matteo Cescon, General Surgery and Transplant Unit, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

Baki Topal, Department of Visceral Surgery, University Hospitals KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Pim B Olthof, Department of Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Department of Surgery, Amsterdam University Medical Centres, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Bas Groot Koerkamp, Department of Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Funding

The authors have no funding to declare.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS online.

Data availability

Data were obtained from the Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma Collaboration Group. Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Kamangar F, Winter JM, Lillemoe KDet al. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg 2007;245:755–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khan SA, Tavolari S, Brandi G. Cholangiocarcinoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Liver Int 2019;39(Suppl 1):19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:9–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pichlmayr R, Lamesch P, Weimann A, Tusch G, Ringe B. Surgical treatment of cholangiocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 1995;19:83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hartog H, Ijzermans JNM, van Gulik TM, Koerkamp BG. Resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Clin North Am 2016;96:247–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Franken LC, Schreuder AM, Roos E, van Dieren S, Busch OR, Besselink MGet al. Morbidity and mortality after major liver resection in patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery 2019;165:918–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Keulen AM, Buettner S, Besselink MG, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, IJzermans JNet al. Primary and secondary liver failure after major liver resection for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery 2021;170:1024–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Spolverato G, Bagante F, Ethun CG, Poultsides G, Tran T, Idrees Ket al. Defining the chance of statistical cure among patients with extrahepatic biliary tract cancer. World J Surg 2017;41:224–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Keulen AM, Olthof PB, Cescon M, Guglielmi A, Jarnagin WR, Nadalin Set al. Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma Collaboration Group. Actual 10-year survival after resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: what factors preclude a chance for cure? Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:6260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koerkamp BG, Wiggers JK, Allen PJ, Besselink MG, Blumgart LH, Busch ORet al. Recurrence rate and pattern of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma after curative intent resection. J Am Coll Surg 2015;221:1041–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wiggers JK, Koerkamp BG, Cieslak KP, Doussot A, van Klaveren D, Allen PJet al. Postoperative mortality after liver resection for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: development of a risk score and importance of biliary drainage of the future liver remnant. J Am Coll Surg 2016;223:321–331.e321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koerkamp BG, Wiggers JK, Gonen M, Doussot A, Allen PJ, Besselink MGHet al. Survival after resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma—development and external validation of a prognostic nomogram. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1930–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gaspersz MP, Buettner S, Roos E, van Vugt JLA, Coelen RJS, Vugts Jet al. A preoperative prognostic model to predict surgical success in patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2018;118:469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coelen RJS, Roos E, Wiggers JK, Besselink MG, Buis CI, Busch ORCet al. Endoscopic versus percutaneous biliary drainage in patients with resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;3:681–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:134–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Olthof PB, Wiggers JK, Groot Koerkamp B, Coelen RJ, Allen PJ, Besselink MGet al. Postoperative liver failure risk score: identifying patients with resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma who can benefit from portal vein embolization. J Am Coll Surg 2017;225:387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Ardito F, Giovannini I, Aldrighetti L, Belli Get al. Improvement in perioperative and long-term outcome after surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: results of an Italian multicenter analysis of 440 patients. Arch Surg 2012;147:26–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nagino M, Kamiya J, Nishio H, Ebata T, Arai T, Nimura Y. Two hundred forty consecutive portal vein embolizations before extended hepatectomy for biliary cancer: surgical outcome and long-term follow-up. Ann Surg 2006;243:364–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yokoyama Y, Ebata T, Igami T, Sugawara G, Mizuno T, Yamaguchi Jet al. The predictive value of indocyanine green clearance in future liver remnant for posthepatectomy liver failure following hepatectomy with extrahepatic bile duct resection. World J Surg 2016;40:1440–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Franken LC, Rassam F, van Lienden KP, Bennink RJ, Besselink MG, Busch ORet al. Effect of structured use of preoperative portal vein embolization on outcomes after liver resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. BJS Open 2020;4:449–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Popescu I, Dumitrascu T. Curative-intent surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic factors for clinical decision making. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2014;399:693–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas Aet al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1273–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frosio F, Mocchegiani F, Conte G, Bona ED, Vecchi A, Nicolini Det al. Neoadjuvant therapy in the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 2019;11:279–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu K, Kei N, Hiroshi Y, Takanori M, Hiroki H, Takaho Oet al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for cholangiocarcinoma to improve R0 resection rate: the first report of phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:402–402 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Primrose JN, Fox RP, Palmer DH, Malik HZ, Prasad R, Mirza Det al. Capecitabine compared with observation in resected biliary tract cancer (BILCAP): a randomised, controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:663–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ebata T, Hirano S, Konishi M, Uesaka K, Tsuchiya Y, Ohtsuka Met al. Bile Duct Cancer Adjuvant Trial (BCAT) Study Group . Randomized clinical trial of adjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy versus observation in resected bile duct cancer. Br J Surg 2018;105:192–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edeline J, Benabdelghani M, Bertaut A, Watelet J, Hammel P, Joly JPet al. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin chemotherapy or surveillance in resected biliary tract cancer (PRODIGE 12-ACCORD 18-UNICANCER GI): a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:658–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chichua M, Brivio E, Mazzoni D, Pravettoni G. Shared decision-making and the lessons learned about decision regret in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2022;30:4587–4590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1975;140:170–178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Gonen M, Burke EC, Bodniewicz BJet al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2001;234:507–517; discussion 517–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Edge SB, Compton CC. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th edn). New York: Springer, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y, Wu Z, Wang X, Li C, Chang J, Jiang Wet al. Development and external validation of a nomogram for predicting the effect of tumor size on survival of patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2020;20:1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen P, Li B, Zhu Y, Chen W, Liu X, Li Met al. Establishment and validation of a prognostic nomogram for patients with resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2016;7:37319–37330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li P, Song L. A novel prognostic nomogram for patients with surgically resected perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a SEER-based study. Ann Transl Med 2021;9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Qi F, Zhou B, Xia J. Nomograms predict survival outcome of Klatskin tumors patients. PeerJ 2020;8:e8570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Elmunzer BJ, Smith ZL, Tarnasky P, Wang AY, Yachimski P, Banovac Fet al. INTERCPT study group and the United States Cooperative for Outcomes Research in Endoscopy (USCORE) . An unsuccessful randomized trial of percutaneous vs endoscopic drainage of suspected malignant hilar obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:1282–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Corvera CU, Blumgart LH, Darvishian F, Klimstra DS, DeMatteo R, Fong Yet al. Clinical and pathologic features of proximal biliary strictures masquerading as hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2005;201:862–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data were obtained from the Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma Collaboration Group. Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.