Abstract

Background

Previous trials found that more intensive postoperative surveillance schedules did not improve survival. Oncological follow-up also provides an opportunity to address psychological issues (for example anxiety, depression, and fear of recurrence). This systematic review assessed the impact of a less intensive surveillance strategy on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), emotional well-being, and patient satisfaction.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane database, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar to identify studies comparing different follow-up strategies after oncological surgery and their effect on HRQoL and patient satisfaction, published before 4 May 2022. A meta-analysis was conducted on the most relevant European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale subscales.

Results

Thirty-five studies were identified, focusing on melanoma (4), colorectal (10), breast (7), prostate (4), upper gastrointestinal (4), gynaecological (3), lung (2), and head and neck (1) cancers. Twenty-two studies were considered to have a low risk of bias, of which 14 showed no significant difference in HRQoL between follow-up approaches. Five studies with a low risk of bias showed improved HRQoL or emotional well-being with a less intensive follow-up approach and three with an intensive approach. Meta-analysis of HRQoL outcomes revealed no negative effects for patients receiving less intensive follow-up.

Conclusion

Low-intensity follow-up does not diminish HRQoL, emotional well-being, or patient satisfaction.

The results of this review suggest that a lower-intensity follow-up approach is non-inferior and, in some instances, even results in slightly better health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and lower anxiety rates. Additionally, previous studies and a recently published systematic review failed to show any (cancer-specific) survival benefit of intensive postoperative surveillance compared with a less intensive approach. Overall, these findings enable a reduction in follow-up intensity for patients with cancer without impact on the main purposes of follow-up: cancer-specific survival and HRQoL. It can be concluded that a patient-tailored follow-up approach is feasible.

Introduction

Cancer treatment modalities have improved significantly in the past few decades, leading to a higher number of cancer survivors1,2. After curative treatment for cancer, most patients receive oncological follow-up care by a specialist in the hospital. These visits consist of physical examinations, blood tests with measurement of serum tumour markers, and radiographic imaging3–6. The main rationale is that earlier treatment for recurrence improves survival, but multiple large RCTs7–9 and a systematic review10 found no (cancer–specific) survival benefit from intensive postoperative surveillance.

Follow-up is also intended to manage the side-effects of curative treatment, and to provide psychological assessment and support for patients recovering from cancer as psychological symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, are common in this patient group11,12. Nevertheless, frequent hospital visits have a significant impact on patients’ lives, as follow-up visits evoke distress and potentially revisit the feelings instigated during diagnosis. Hospital visits enhance concerns about the threat of recurrence13–15. For these reasons, some patients may prefer cancer follow-up in a non-hospital setting. As no two patients with cancer are alike, a patient-tailored and personalized approach to follow-up might be beneficial. The aim of this review was to assess whether health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is influenced by different follow-up approaches, varying in intensity and location.

Methods

Search strategy

This study was performed in line with the PRISMA guidelines (https://www.prisma-statement.org). Six databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane database, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar) were searched systematically for studies published before 4 May 2022. The search terms are provided in Table S1. Reference lists were screened to identify additional eligible articles.

Study selection

RCTs and observational cohort studies written in English were included when they compared follow-up approaches after treatment with curative intent for solid cancers regarding HRQoL outcomes, emotional well-being, and patient satisfaction. Studies that evaluated a follow-up period of less than 3 months after surgery were excluded, as this was considered part of the postoperative trajectory of a patient and HRQoL could be affected independent of follow-up approach. Additionally, articles investigating techniques in postoperative telemonitoring at home were excluded as this was not considered a follow-up approach after treatment. Non-original studies (for example meta-analyses, systematic reviews, editorials), non-comparative studies, and studies using simulation techniques (for example, Markov modelling, Health Technology Assessment studies) were excluded. Screening for eligible studies was conducted by two authors independently. Disagreement was resolved by joint assessment.

Data extraction and presentation

Studies were categorized based on type of solid tumour and the following aspects of follow-up: frequency of testing, setting of follow-up, diagnostic modalities used, or a combination. Setting of follow-up visits included in-hospital care, telephone or web-based check-ups and home visits, conducted by a specialist, general practitioner or specialist nurse. Data on study design, sample size, population characteristics, and questionnaire outcomes were collected.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was undertaken by two authors independently. The Cochrane tool Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Interventions (ROBINS-I) was used for observational studies, and Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) for randomized studies16,17. A study was identified as having a low risk of bias when assessed as ‘low’ using ROBINS-I, or as ‘low risk’ using RoB2. Studies were identified to be at high risk of bias when assessed as either ‘serious’ or ‘critical’ using ROBINS-I, or ‘high risk’ using RoB2. When studies scored ‘moderate’ using ROBINS-I or ‘some concerns’ using RoB2, they were evaluated again by joint assessment and categorized as low or high risk.

Quantitative assessment

A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted, using the generic inverse-variance method in Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, United Kingdom) in line with the Cochrane Collaboration handbook recommendation18. Subscales of the most applied questionnaires, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life (QLQ) C30 and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) were analyzed when reported as mean(s.d.). Results are presented as mean difference with corresponding 95 per cent confidence intervals. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic. Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the strength of the conclusions by excluding studies judged to be at high risk of bias, and by excluding articles that investigated additional coaching versus usual care instead of comparing a less intensive approach with usual care.

Results

Literature search

Following a comprehensive literature search (Table S1), 2736 references were identified and screened after removing duplicates. Based on the title and abstract, 2646 articles were excluded and the full text of 90 was screened. Ultimately, 35 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion (Fig. 1). The included articles were subcategorized into follow-up after treatment of colorectal (10), breast (7), prostate (4), upper gastrointestinal cancer (4), melanoma (4), and gynaecological (3), lung (2), and head and neck cancer (1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing selection of articles for review

QoL, quality of life.

Overall study characteristics

A total of 35 studies were included, 31 RCTs and 4 cohort studies. In total, 22 studies were categorized as low risk (20 RCTs and 2 cohort studies). Overall, 24 articles showed no significant difference in HRQoL, emotional well-being or patient satisfaction with different follow-up approaches. Of the 22 articles that had a low risk of bias, 14 showed no significant difference in HRQoL, emotional well-being or patient satisfaction between follow-up approaches, in 5 studies improved HRQoL or emotional well-being was associated with less intensive follow-up, and in 3 with an intensive approach. An overview of all included articles, risk of bias, and main results can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of included articles

| Reference | Study design | Patients | FU type | Minimal FU | Intensive FU | Conclusion | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ackermann et al.20 | RCT | 100, melanoma | Patient-initiated | Patient-initiated FU | Traditional hospital FU | No differences in HRQoL | High |

| Augestad et al.21 | RCT | 110, colorectal cancer | GP | GP FU | Traditional hospital FU | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Batehup et al.22 | Prospective | 251, colorectal cancer | Patient-initiated | Traditional outpatient FU | Patient-triggered FU | HRQoL in favour of minimal FU | High |

| Beaver et al.23 | RCT | 374, breast cancer | Nurse | Nurse-led telephone FU | Traditional hospital FU | No differences in anxiety, greater satisfaction with telephone FU | High |

| Beaver et al.24 | RCT | 65, colorectal cancer | Telephone | Telephone FU | Traditional hospital FU | No differences in anxiety and satisfaction | Low |

| Björneklett et al.25 | RCT | 362, breast cancer | Frequency | Usual care | Additional support programme | HRQoL in favour of intensive FU | Low |

| Davis et al.26 | RCT | 94, prostate cancer | Patient-initiated | Symptom monitoring + feedback | Usual care | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| De Leeuw et al.28 | Prospective | 160, head and neck cancer | Nurse | Traditional care | Additional nursing consultations | No differences in HRQoL | High |

| Deckers et al.29 | RCT | 180, melanoma | Frequency | Experimental (fewer clinical visits) | Traditional hospital FU | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Denis et al.30 | RCT | 121, lung cancer | Web/app | Web-mediated FU with less CT | Routine FU (more CT) | HRQoL in favour of minimal FU | High |

| Elliott et al.31 | Retrospective | 726, upper GI cancer | Frequency | Surveillance (less CT/PET–CT) | Intensive surveillance | HRQoL in favour of minimal FU | Low |

| Emery et al.32 | RCT | 493, prostate cancer | GP | GP visits (replacing 2 hospital visits) | Traditional hospital FU | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Faithfull et al.33 | RCT | 115, prostate and bladder cancer | Nurse | Nurse-led telephone FU | Traditional hospital FU | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Frankland et al.34 | Prospective | 627, prostate cancer | Patient-initiated | Remote monitoring (patient-led FU) | Traditional hospital FU | HRQoL in favour of minimal FU | Low |

| Hovdenak Jakobsen et al.35 | RCT | 336, colorectal cancer | Patient-initiated | Patient-initiated FU | Traditional hospital FU | HRQoL in favour of minimal FU | Low |

| Jefford et al.36 | RCT | 224, colorectal cancer | Frequency | Usual care | Additional specialist nurse consultations | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Jeppesen et al.37 | RCT | 156, gynaecological cancer | Patient-initiated | Patient-initiated FU | Traditional hospital FU | HRQoL in favour of intensive FU | Low |

| Kimman et al.39 | RCT | 299, breast cancer | Nurse | Nurse-led telephone FU | Traditional hospital FU | No differences in patient satisfaction | High |

| Kimman et al.40 | RCT | 299, breast cancer | Web/app | Nurse-led telephone FU | Extra educational programme | No differences in HRQoL | High |

| Kirshbaum et al.41 | RCT | 112, breast cancer | Patient-initiated | Standard breast clinic after care | Open-access aftercare by nurses | No differences in HRQoL | High |

| Kjeldsen et al. 199942 | RCT | 350, colorectal cancer | Frequency | Virtually no FU (examination every 5 years) | Frequent hospital FU | HRQoL in favour of intensive FU | High |

| Koinberg et al.43 | RCT | 264, breast cancer | Nurse | Nurse-led FU on demand | Physician FU | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Liberati44 | RCT | 1330, breast cancer | Frequency | Only clinically indicated tests | Physician FU + imaging | No differences in HRQoL | High |

| Moncrieff et al.45 | RCT | 82, upper GI cancer | Nurse | Nurse-led telephone care | Specialist care (clinical visits) | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Malmström et al.46 | RCT | 207, upper GI cancer | Frequency | Experimental (fewer clinical visits) | Conventional (more clinical visits) | No differences in HRQoL | High |

| Morrison et al.47 | RCT | 24, gynaecological cancer | Nurse | Specialist nurse-led telephone education | Traditional hospital FU | HRQoL in favour of minimal FU | Low |

| Naeser et al.48 | RCT | 297, melanoma | Frequency | Traditional FU | Additional imaging and blood tests | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Ngu et al.49 | RCT | 385, gynaecological cancer | Nurse | Nurse-led FU on demand | Gynaecologist-led clinic FU | HRQoL in favour of minimal FU | Low |

| Oliveira et al.50 | RCT | 81, upper GI cancer | Telephone | Traditional FU | Additional telephone FU | No differences in HRQoL | High |

| Rosati et al.8 | RCT | 1242, colorectal cancer | Frequency | Minimal programme | Intensive programme (more imaging) | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Sui et al.51 | RCT | 200, lung cancer | Web/app | Usual care | WERP | HRQoL in favour of intensive FU | Low |

| Verschuur et al.52 | RCT | 103, upper GI cancer | Nurse | Nurse-led FU | Physician-led FU | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Vos et al.27 | RCT | 353, colorectal cancer | GP | GP FU | Surgeon FU | No differences in HRQoL | High |

| Wattchow et al.19 | RCT | 203, colorectal cancer | GP | GP FU | Surgeon FU | No differences in HRQoL | Low |

| Zhan et al.53 | RCT | 4948, colorectal cancer | Frequency | Usual care | Intensified CEA protocol | No differences in anxiety | Low |

FU, follow-up; HRQol, health-related quality of life; GP, general practitioner; GI, gastrointestinal; WERP, WeChat app-based education and rehabilitation programme; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

Twenty-six articles measured HRQoL, 17 studies measured anxiety and patient well-being, and 8 evaluated patient satisfaction. A large variety of validated and a few non-validated patient-reported outcome questionnaires were employed. The most commonly used instruments were the EORTC QLQ-C30, followed by the HADS (Table S2). Mean results for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and HADS subscales are presented in Figs S1 and S2 respectively.

Type of cancer

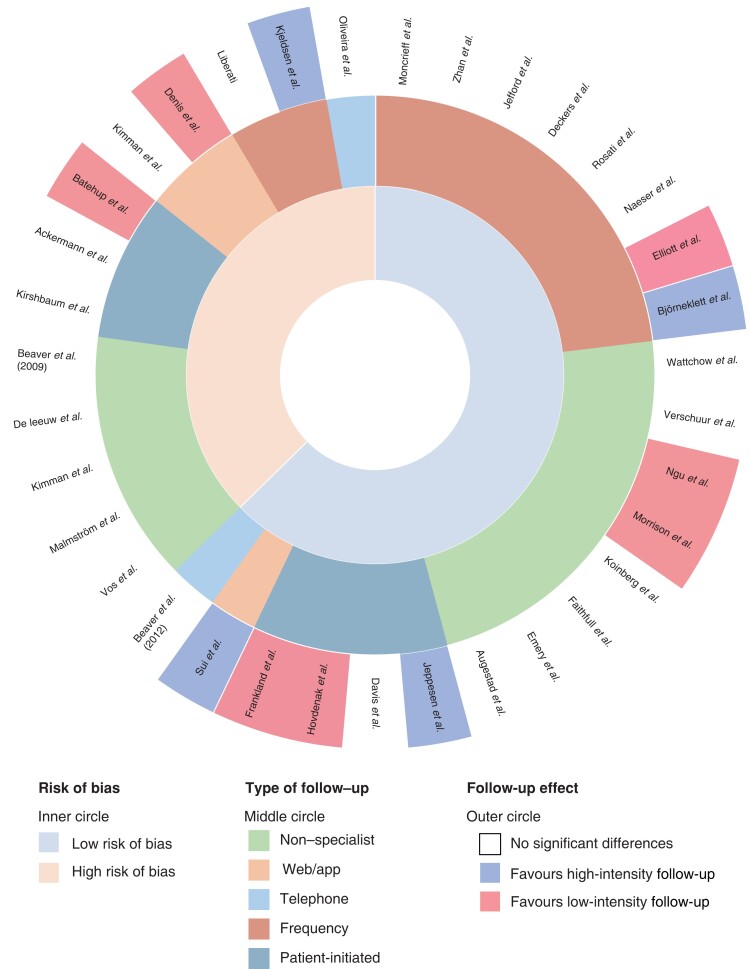

A comprehensive overview of all included studies by cancer type and outcome measure is shown in Fig. 2 and supplementary material.

Fig. 2.

Multilayered circle plot: effect of follow-up categorized by tumour type

.

Colorectal cancer

A total of 10 studies (9 RCTs, 1 cohort) were included, of which 7 had a low risk of bias. These studies included a total of 8082 patients who were in follow-up for colorectal cancer8,21,22,24,35,36,42,19,27,53. Sample sizes ranged from 65 to 4948. None of the studies with a low risk of bias showed a negative difference in terms of overall HRQoL, emotional well-being, and patient satisfaction8,21,24,35,36,19. High-risk studies were divided, with one42 favouring a more intensive approach, one22 favouring a less intensive approach, and one showing no significant differences27.

Breast cancer

In total, 2741 patients with breast cancer were included in 7 RCTs, of which 143 had a low risk of bias. The sample size ranged from 112 to 133023,25,39,40,40,41,43,19. Six of the included references showed no significant difference in terms of HRQoL, emotional well-being, and patient satisfaction with different follow-up approaches. One study looked at the effect of a support programme additional to usual care, and found that it affected the intervention group positively.

Prostate cancer

Four studies (1 RCTs, 1 cohort) analysed patients with prostate cancer, including 1329 patients. Sample size ranged from 94 to 62726,32–34. All four studies were considered to have a low risk of bias. Three studies26,32,33 showed no significant difference in terms of HRQoL, psychological well-being, and patient satisfaction with different follow-up approaches. Frankland et al.34 reported a significant difference, with better HRQoL for patients with a less intensive follow-up approach.

Upper gastrointestinal tract cancer

A total of four studies were included, of which three were RCTs and one a retrospective cohort study. These studies included a total of 992 patients who were in follow-up for cancer of the upper gastrointestinal tract. The sample size ranged from 81 to 726, and two31,52 of four articles had a low risk of bias. Three46,50,52 of these studies showed no significant difference in terms of HRQoL, psychological well-being, and patient satisfaction. The retrospective cohort study by Elliott et al.31 revealed better HRQoL with less intensive follow-up.

Melanoma

Four studies, all RCTs, were included with a total of 784 patients in follow-up for melanoma. Sample size ranged from 100 to 297 patients20,29,45,48. Three studies were at low risk of bias, and none showed a significant difference in terms of HRQoL, psychological well-being, and patient satisfaction with different follow-up approaches.

Gynaecological cancer

Three studies focused on a total of 565 patients after oncological gynaecological treatment; all were considered to have a low risk of bias. Sample size ranged from 24 to 38537,47,49. Two studies focused on nurse-led follow-up and one study considered patient-initiated follow-up as the minimal intensive follow-up. Results were divided, with two studies showing a significant difference favouring the less intensive follow-up approach and one favouring more intensive follow-up in terms of fear of cancer recurrence.

Lung cancer

In total 321 patients with lung cancer were included in two studies. Sample size was 121 and 20030,51. Both studies focused on web-mediated or app-based follow-up. Results were divided; the study by Sui et al.51, which had a low risk of bias, favoured a more intensive follow-up approach in terms of a chat app in addition to usual care, whereas that by Denis et al.30, with a high risk of bias, favoured a less intensive follow-up scheme by means of web-mediated follow-up with less imaging.

Head and neck cancer

One study28 evaluated the HRQoL associated with follow-up intensity in patients with head and neck cancer. Patients received additional bimonthly nursing follow-up consultations. The baseline EORTC scales were significantly worse for patients in the nursing consultation group. After 12 months, the outcome was consistent in both groups. Adding nursing consultations to the routine follow-up had a positive effect on HRQoL.

Type of follow-up

HRQoL, anxiety, and patient satisfaction outcomes by follow-up approach are visualized in the multilayered circle plot in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Multilayered circle plot: effect of follow-up categorized by follow-up type

.

Non-specialist follow-up

In total, 13 studies investigated the effects on HRQoL and emotional well-being when patients received non-specialist follow-up (general practitioner or specialist nurse). Eleven of these studies showed no significant difference compared with traditional in-hospital specialist care, resulting in non-inferiority of the nurse- or general practitioner-led follow-up. Two studies47,49 reported significant differences favouring the follow-up scheme conducted by specialist nurses, showing positive changes in HRQoL.

Telephone follow-up

Several studies provide insights into how patients evaluate telephone follow-up after treatment for colorectal cancer, breast cancer, gynaecological cancer, and cancer of the upper gastrointestinal tract23,24,39,40,43,46,47,50. None of the included studies showed any negative effects on HRQoL, emotional well-being or patient satisfaction during telephone follow-up. Morrison et al.41 evaluated telephone follow-up in a group of patients with gynaecological cancer. For all the EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales, the group receiving telephone follow-up had equal or better scores at 6 months of follow-up compared with usual care in the hospital setting.

Frequency of follow-up

A few studies investigated a reduced-frequency follow-up scheme with fewer follow-up appointments, and less radiographic imaging or other interventions such as a colonoscopy8,29,31,40,42,44,45. Five of these studies showed no significant differences regarding HRQoL, emotional well-being or patient satisfaction. A retrospective cohort study by Elliott et al.31, investigating reduced frequency after curative surgery for oesophageal surgery, showed increased levels of anxiety in the group receiving an intensive follow-up approach. A study by Kjeldsen et al.42, which had a high risk of bias, compared traditional follow-up with virtually no follow-up (examination every 5 years), and reported a small difference in HRQoL scores between the two study groups slightly favouring the more intensive approach.

A few articles looked at educational support programmes additional to usual care, resulting in more intensive follow-up25,36. Björneklett et al.25 investigated an additional support programme for patients after treatment for breast cancer, and concluded that there was a small positive difference for the intervention group. Jefford et al.36 looked at a SurvivorCare package additional to usual care for patients with colorectal cancer, and concluded that there were no significant differences between groups.

Quantitative assessment

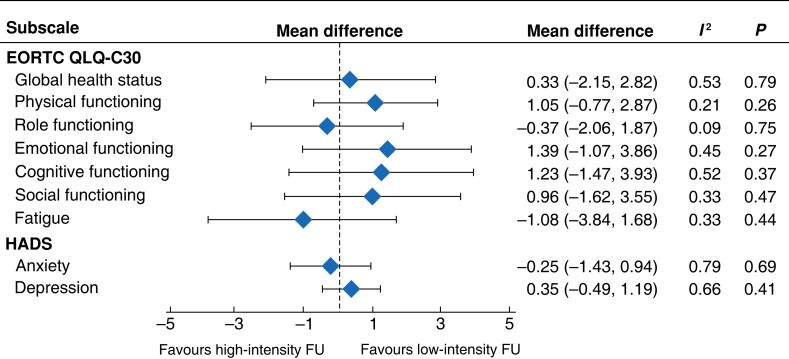

Meta-analysis

Of the 35 identified studies, 10 were eligible for quantitative synthesis of the EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales and 4 for the HADS subscales54,38. Although the studies varied in setting (nurse-, specialist- or general practitioner-led, telephone- or web-mediated follow-up) and intensity of follow-up, there was little inconsistency in the results. None of the subscales showed a significant direction of effect, indicating non-inferiority of low-intensity follow-up. Simplified results of the meta-analysis of the most relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales and the HADS questionnaire are shown in Fig. 4; forest plots for individual subdomains are available in Figs S1 and S2.

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Mean differences are shown with 95% confidence intervals. HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; FU, follow-up.

Sensitivity analysis

After excluding studies with a high risk of bias, findings for the outcome HRQoL were robust to sensitivity analyses. Excluding studies at high risk of bias for the EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales40,41,46, there was no statistical evidence of a HRQoL advantage for patients receiving less intensive follow-up in any of the subscales. A drawback was that results from some EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales such as pain and insomnia were not reported by all articles, notwithstanding analysis of the subscales deemed most relevant. Furthermore, a significant number of articles only disclosed the overall score for the EORTC QLQ-C30. Therefore, meta-analysis of these was not possible.

After excluding studies investigating additional support or rehabilitation programmes compared with usual follow-up care25,36,51, there was statistical evidence of a HRQoL advantage on the global health status scale (mean difference 2.11, 95 per cent c.i. 0.13 to 4.09; P = 0.04), with little heterogeneity (I² = 19 per cent, P = 0.28).

Sensitivity analyses for studies using the HADS subscales showed robust results for anxiety (mean difference −0.05, −1.39 to 1.29) and depression (mean difference 0.38, −0.165 to 1.741), after exclusion of a study41 at high risk of bias. After excluding studies investigating additional support or rehabilitation programmes51, there was no statistical evidence of an advantage for the comparison of intensive versus less intensive follow-up in the depression subscale (mean difference 0.00, −0.71 to 0.71). There was, however, an advantage in the anxiety subscale favouring less intensive follow-up (mean difference −0.79, −1.41 to −0.17; P = 0.01).

Discussion

The aim of oncological follow-up after curative treatment is to detect the development of recurrent disease, and it also provides an opportunity to address psychological issues, such as anxiety, depression, and fear of recurrence. This systematic review provides an overview of the impact of different follow-up approaches on HRQoL, emotional well-being, and patient satisfaction for patients with solid tumours. The present review identified 35 studies comparing follow-up approaches, differing in frequency, location of the appointment, and who provided the check-up care, of which 17 were considered to be at low risk of bias. There was no evidence of negative effects regarding HRQoL, emotional well-being or satisfaction when patients experienced less intensive follow-up. The absence of negative effects was irrespective of cancer type, location, intensity, frequency, or modality of follow-up. Patients are equally, or even more, satisfied with nurse-led follow-up models55–57. Non-specialist follow-up is feasible and results show similar and even better HRQoL compared with traditional follow-up. Nurse-led follow-up is very cost-effective33,47.

None of the included studies showed any negative effects on HRQoL, emotional well-being or patient satisfaction for telephone follow-up. The convenience of conducting follow-up from the comfort of a patient’s own home enables continuity of care and personalized support. Additionally, it provides an opportunity for uninterrupted contact, which is more difficult to achieve in a hospital environment. Beaver et al.24. noted it to be unlikely that specialist nurses could provide follow-up care for all patients on completion of treatment. Nevertheless, they could take responsibility for a significant cohort who prefer being telephoned at home. If telephone support is equivalent to hospital support, with no physical or psychological disadvantages, an approach offering patients a choice of follow-up care could be introduced.

Both non-specialist follow-up and telephone follow-up can be of value for oncological patients after treatment. Busy hospital clinics in the follow-up setting, sometimes allocating only 5–10 min per visit, are not conducive to a detailed and personalized discussion of patient’s needs, preferences, and concerns. A potential reason why follow-up in hospital could lead to worse emotional and cognitive functioning is that patients may have their sick role reinforced, as they are regularly reminded of their diagnosis and of the possibility that their cancer may recur. Other noteworthy advantages of telemedicine and non-specialist follow-up are diminished workload for hospital personnel, and reducing transport time and cost for patients, adding to a more sustainable healthcare system. Moreover, reducing hospital visits has become especially relevant during the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. It provided a stimulus for re-evaluating the setting in which care could be conducted, and rapidly increased caregivers’ and patients’ acceptability of alternative follow-up methods, such as telemedicine, instead of conventional outpatient visits58–64.

Approaches investigating a reduced-frequency follow-up trajectory entailed patient-triggered follow-up and fewer investigations (for example blood withdrawal, imaging, and outpatient visits). A review summarising the literature on gynaecologic cancer patients’ and health care professionals’ views on follow-up found that the patients’ greatest concern was fear of recurrence65. Patients’ greatest need was therefore reassurance, because they assume that the main purpose of a routine follow-up programme would be early detection of relapse. Consequently, this specific patient group prefers seeing their specialist, although studies have found that routine follow-up is not the desire of the majority of the patients, when told about the lack of evidence37. Results have shown higher anxiety levels with patient-initiated follow-up in gynaecological cancer66,67. However, the two other gynaecology studies47,49 reported positive HRQoL in patients followed up by nurses.

In contrast, patient-triggered follow-up is acceptable for patients with colorectal cancer and can be considered to be a realistic alternative22,35. This approach provides elements evidenced to be very important to patients: convenience, personalized information when desired, reassurance through a process of quick access to specialist advice, and a trusting relationship with care providers. Both telephone follow-up and open-access care by nurses are a feasible alternative to hospital-based follow-up, and have the added advantage of not having to attend a clinic that may reinforce unnecessary worry of recurrence24,41.

Fewer blood tests and less imaging did not seem to have a negative impact on HRQoL or emotional well-being in most included articles8,29,36,44,45,48. One study42 comparing conventional hospital follow-up with virtually no follow-up (physical examination every 5 years) found that HRQoL slightly favoured a more intensive approach. More imaging after oesophagectomy may give rise to more patient anxiety31. Instead of reducing frequency, some articles investigated the effect of additional support and coaching25. Another example of this is the chat-based educational programme51. Certainly, the overall sense is that a lower intensity follow-up is non-inferior for HRQoL, and may be better in terms of the global health status of the EORTC QLQ-C30 or anxiety subscale of the HADS questionnaire68.

Conclusion

In conclusion, less intensive follow-up of oncological surgery has no negative influence on HRQoL, emotional wellbeing and patient satisfaction. There seems to be no difference in who conducts the follow-up visit, whether this is the oncological specialist, the general practitioner or the specialist nurse. Overall, these findings enable a reduction in follow-up intensity for patients with cancer without an impact on the main purposes of follow-up: cancer-specific survival and HRQoL. It can be concluded that a patient-tailored follow-up approach is feasible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

L.W. and K.R.V. are joint authors of this article. The authors thank E. Krabbendam and M. Engel from the Erasmus MC Medical Library for developing and updating the search strategies.

Contributor Information

Lissa Wullaert, Department of Surgical Oncology and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Kelly R Voigt, Department of Surgical Oncology and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Cornelis Verhoef, Department of Surgical Oncology and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Olga Husson, Department of Surgical Oncology and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Department of Psychosocial Research and Epidemiology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Dirk J Grünhagen, Department of Surgical Oncology and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Author contributions

Lissa Wullaert (conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing), Kelly Voigt (conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing), Kees Verhoef (conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing), Olga Husson (conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing), and Dirk Grünhagen (conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing).

Funding

The authors have no funding to declare.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS online.

Data availability statement

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and can be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Brouwer NPM, Bos A, Lemmens V, Tanis PJ, Hugen N, Nagtegaal IDet al. An overview of 25 years of incidence, treatment and outcome of colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer 2018;143:2758–2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Verdecchia A, Guzzinati S, Francisci S, De Angelis R, Bray F, Allemani Cet al. Survival trends in European cancer patients diagnosed from 1988 to 1999. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1042–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cardoso R, Coburn NG, Seevaratnam R, Mahar A, Helyer L, Law Cet al. A systematic review of patient surveillance after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a brief review. Gastric Cancer 2012;15:S164–S167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmidt-Hansen M, Baldwin DR, Hasler E. What is the most effective follow-up model for lung cancer patients? A systematic review. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:821–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Swinnen J, Keupers M, Soens J, Lavens M, Postema S, Van Ongeval C. Breast imaging surveillance after curative treatment for primary non-metastasised breast cancer in non-high-risk women: a systematic review. Insights Imaging 2018;9:961–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Stok EP, Spaander MCW, Grunhagen DJ, Verhoef C, Kuipers EJ. Surveillance after curative treatment for colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:297–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Primrose JN, Perera R, Gray A, Rose P, Fuller A, Corkhill Aet al. Effect of 3 to 5 years of scheduled CEA and CT follow-up to detect recurrence of colorectal cancer: the FACS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311:263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosati G, Ambrosini G, Barni S, Andreoni B, Corradini G, Luchena Get al. A randomized trial of intensive versus minimal surveillance of patients with resected Dukes B2–C colorectal carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2016;27:274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wille-Jorgensen P, Syk I, Smedh K, Laurberg S, Nielsen DT, Petersen SHet al. Effect of more vs less frequent follow-up testing on overall and colorectal cancer-specific mortality in patients with stage II or III colorectal cancer: the COLOFOL randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;319:2095–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Galjart B, Höppener DJ, Aerts J, Bangma CH, Verhoef C, Grünhagen DJ. Follow-up strategy and survival for five common cancers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2022;174:185–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pitman A, Suleman S, Hyde N, Hodgkiss A. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ 2018;361:k1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Niedzwiedz CL, Knifton L, Robb KA, Katikireddi SV, Smith DJ. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: a growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer 2019;19:943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Greimel E, Nordin A, Lanceley A, Creutzberg CL, van de Poll-Franse LV, Radisic VBet al. Psychometric validation of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire-endometrial cancer module (EORTC QLQ-EN24). Eur J Cancer 2011;47:183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nicolaije KA, Husson O, Ezendam NP, Vos MC, Kruitwagen RF, Lybeert MLet al. Endometrial cancer survivors are unsatisfied with received information about diagnosis, treatment and follow-up: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Patient Educ Couns 2012;88:427–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stiggelbout AM, de Haes JC, Vree R, van de Velde CJ, Bruijninckx CM, van Groningen Ket al. Follow-up of colorectal cancer patients: quality of life and attitudes towards follow-up. Br J Cancer 1997;75:914–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman ADet al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan Met al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3. Cochrane, 2022. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- 19. Ackermann DM, Dieng M, Medcalf E, Jenkins MC, van Kemenade CH, Janda Met al. Assessing the potential for patient-led surveillance after treatment of localized melanoma (MEL-SELF): a pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2022;158:33–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Augestad KM, Norum J, Dehof S, Aspevik R, Ringberg U, Nestvold Tet al. Cost-effectiveness and quality of life in surgeon versus general practitioner-organised colon cancer surveillance: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Batehup L, Porter K, Gage H, Williams P, Simmonds P, Lowson Eet al. Follow-up after curative treatment for colorectal cancer: longitudinal evaluation of patient initiated follow-up in the first 12 months. Supportive Care Cancer 2017;25:2063–2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beaver K, Tysver-Robinson D, Campbell M, Twomey M, Williamson S, Hindley Aet al. Comparing hospital and telephone follow-up after treatment for breast cancer: randomised equivalence trial. BMJ 2009;338:a3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beaver K, Campbell M, Williamson S, Procter D, Sheridan J, Heath Jet al. An exploratory randomized controlled trial comparing telephone and hospital follow-up after treatment for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2012;14:1201–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Björneklett HG, Rosenblad A, Lindemalm C, Ojutkangas ML, Letocha H, Strang Pet al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized study of support group intervention in women with primary breast cancer. J Psychosom Res 2013;74:346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Davis KM, Dawson D, Kelly S, Red S, Penek S, Lynch Jet al. Monitoring of health-related quality of life and symptoms in prostate cancer survivors: a randomized trial. J Supportive Oncol 2013;11:174–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Leeuw J, Prins JB, Teerenstra S, Merkx MAW, Marres HAM, Van Achterberg T. Nurse-led follow-up care for head and neck cancer patients: a quasi-experimental prospective trial. Supportive Care Cancer 2013;21:537–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deckers EA, Hoekstra-Weebers J, Damude S, Francken AB, Ter Meulen S, Bastiaannet Eet al. The MELFO study: a multicenter, prospective, randomized clinical trial on the effects of a reduced stage-adjusted follow-up schedule on cutaneous melanoma IB–IIC patients—results after 3 years. Ann Surg Oncol 2020;27:1407–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Denis F, Basch EM, Lethrosne C, Pourel N, Molinier O, Pointreau Yet al. Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up via patient-reported outcomes (PRO) vs. routine surveillance in lung cancer patients: final results. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:6500 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elliott JA, Markar SR, Klevebro F, Johar A, Goense L, Lagergren Pet al. An international multicenter study exploring whether surveillance after esophageal cancer surgery impacts oncological and quality of life outcomes (ENSURE). Ann Surg 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Emery JD, Jefford M, King M, Hayne D, Martin A, Doorey Jet al. Procare trial: a phase II randomized controlled trial of shared care for follow-up of men with prostate cancer. BJU Int 2017;119:381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Faithfull S, Corner J, Meyer L, Huddart R, Dearnaley D. Evaluation of nurse-led follow up for patients undergoing pelvic radiotherapy. Br J Cancer 2001;85:1853–1864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Frankland J, Brodie H, Cooke D, Foster C, Foster R, Gage Het al. Follow-up care after treatment for prostate cancer: evaluation of a supported self-management and remote surveillance programme. BMC Cancer 2019;19:368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hovdenak Jakobsen I, Vind Thaysen H, Laurberg S, Johansen C, Juul T; FURCA Steering Group . Patient-led follow-up reduces outpatient doctor visits and improves patient satisfaction. One-year analysis of secondary outcomes in the randomised trial Follow-Up after Rectal CAncer (FURCA). Acta Oncol 2021;60:1130–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jefford M, Gough K, Drosdowsky A, Russell L, Aranda S, Butow Pet al. A randomized controlled trial of a nurse-led supportive care package (SurvivorCare) for survivors of colorectal cancer. Oncologist 2016;21:1014–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jeppesen MM, Jensen PT, Hansen DG, Christensen RD, Mogensen O. Patient-initiated follow up affects fear of recurrence and healthcare use: a randomised trial in early-stage endometrial cancer. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2018;125:1705–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kimman ML, Bloebaum MMF, Dirksen CD, Houben RMA, Lambin P, Boersma LJ. Patient satisfaction with nurse-led telephone follow-up after curative treatment for breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2010;10:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kimman ML, Dirksen CD, Voogd AC, Falger P, Gijsen BCM, Thuring Met al. Nurse-led telephone follow-up and an educational group programme after breast cancer treatment: results of a 2 × 2 randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:1027–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kirshbaum MN, Dent J, Stephenson J, Topping AE, Allinson V, McCoy Met al. Open access follow-up care for early breast cancer: a randomised controlled quality of life analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017;26:e12577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kjeldsen BJ, Thorsen H, Whalley D, Kronborg O. Influence of follow-up on health-related quality of life after radical surgery for colorectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999;34:509–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koinberg IL, Fridlund B, Engholm GB, Holmberg L. Nurse-led follow-up on demand or by a physician after breast cancer surgery: a randomised study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2004;8:109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liberati A. Impact of follow-up testing on survival and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1994;271:1587–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moncrieff MD, Underwood B, Garioch JJ, Heaton M, Patel N, Bastiaannet Eet al. The MelFo study UK: effects of a reduced-frequency, stage-adjusted follow-up schedule for cutaneous melanoma 1B to 2C patients after 3-years. Ann Surg Oncol 2020;27:4109–4119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Malmström M, Ivarsson B, Klefsgård R, Persson K, Jakobsson U, Johansson J. The effect of a nurse led telephone supportive care programme on patients’ quality of life, received information and health care contacts after oesophageal cancer surgery—a six month RCT-follow-up study. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;64:86–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Morrison V, Spencer LH, Totton N, Pye K, Yeo ST, Butterworth Cet al. Trial of optimal personalised care after treatment—gynaecological cancer (TOPCAT-G): a randomized feasibility trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2018;28:401–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Naeser Y, Helgadottir H, Hansson J, Ingvar C, Elander NO, Flygare Pet al. Quality of life in the first year of follow-up in a randomized multicenter trial assessing the role of imaging after radical surgery of stage IIB–C and III cutaneous melanoma (TRIM study). Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ngu SF, Wei N, Li J, Chu MMY, Tse KY, Ngan HYSet al. Nurse-led follow-up in survivorship care of gynaecological malignancies—a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2020;29:e13325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Oliveira DDSS, Ribeiro Junior U, Sartório NA, Dias AR, Takeda FR, Cecconello I. Impact of telephone monitoring on cancer patients undergoing esophagectomy and gastrectomy. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2021;55:e03679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sui Y, Wang T, Wang X. The impact of WeChat app-based education and rehabilitation program on anxiety, depression, quality of life, loss of follow-up and survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients who underwent surgical resection. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2020;45:101707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Verschuur EML, Steyerberg EW, Tilanus HW, Polinder S, Essink-Bot ML, Tran KTCet al. Nurse-led follow-up of patients after oesophageal or gastric cardia cancer surgery: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer 2009;100:70–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vos JAM, Duineveld LAM, Wieldraaijer T, Wind J, Busschers WB, Sert Eet al. Effect of general practitioner-led versus surgeon-led colon cancer survivorship care, with or without eHealth support, on quality of life (I CARE): an interim analysis of 1-year results of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:1175–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wattchow DA, Weller DP, Esterman A, Pilotto LS, McGorm K, Hammett Zet al. General practice vs surgical-based follow-up for patients with colon cancer: randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 2006;94:1116–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhan Z, Verberne CJ, Van Den Heuvel ER, Grossmann I, Ranchor AV, Wiggers Tet al. Psychological effects of the intensified follow-up of the CEAwatch trial after treatment for colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2017;12:e0184740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJet al. The European Organization for Research And Treatment Of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cox K, Wilson E. Follow-up for people with cancer: nurse-led services and telephone interventions. J Adv Nurs 2003;43:51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lewis RA, Neal RD, Williams NH, France B, Hendry M, Russell Det al. Follow-up of cancer in primary care versus secondary care: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2009;59:e234–e247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lanceley A, Berzuini C, Burnell M, Gessler S, Morris S, Ryan Aet al. Ovarian cancer follow-up: a preliminary comparison of 2 approaches. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2017;27:59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Darcourt JG, Aparicio K, Dorsey PM, Ensor JE, Zsigmond EM, Wong STet al. Analysis of the implementation of telehealth visits for care of patients with cancer in Houston during the COVID-19 pandemic. JCO Oncol Pract 2021;17:e36–e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hasson SP, Waissengrin B, Shachar E, Hodruj M, Fayngor R, Brezis Met al. Rapid implementation of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives and preferences of patients with cancer. Oncologist 2021;26:e679–ee85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pardolesi A, Gherzi L, Pastorino U. Telemedicine for management of patients with lung cancer during COVID-19 in an Italian cancer institute: SmartDoc project. Tumori 2022;108:357–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rodler S, Apfelbeck M, Schulz GB, Ivanova T, Buchner A, Staehler Met al. Telehealth in uro-oncology beyond the pandemic: toll or lifesaver? Eur Urol Focus 2020;6:1097–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Smith SJ, Smith AB, Kennett W, Vinod SK. Exploring cancer patients’, caregivers’, and clinicians’ utilisation and experiences of telehealth services during COVID-19: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2022;105:3134–3142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Triantafillou V, Layfield E, Prasad A, Deng J, Shanti RM, Newman JGet al. Patient perceptions of head and neck ambulatory telemedicine visits: a qualitative study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021;164:923–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zimmerman BS, Seidman D, Berger N, Cascetta KP, Nezolosky M, Trlica Ket al. Patient perception of telehealth services for breast and gynecologic oncology care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single center survey-based study. J Breast Cancer 2020;23:542–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dahl L, Wittrup I, Væggemose U, Petersen LK, Blaakaer J. Life after gynecologic cancer—a review of patients quality of life, needs, and preferences in regard to follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013;23:227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lewis RA, Neal RD, Hendry M, France B, Williams NH, Russell Det al. Patients’ and healthcare professionals’ views of cancer follow-up: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2009;59:e248–e259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kew FM, Galaal K, Manderville H. Patients’ views of follow-up after treatment for gynaecological cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;29:135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, de Castro G Jr, Martyn St-James M, Fayers PMet al. Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:1713–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and can be shared upon request to the corresponding author.