Abstract

Background

High surgical volumes are attributed to improved quality of care, especially for extensive procedures. However, it remains unknown whether high-volume surgeons and hospitals have better results in gallstone surgery. The aim of this study was to investigate whether operative volume affects outcomes in cholecystectomies.

Methods

A registry-based cohort study was performed, based on the Swedish Registry of Gallstone Surgery. Cholecystectomies from 2006 to 2019 were included. Annual volumes for the surgeon and hospital were retrieved. All procedures were categorized into volume-based quartiles, with the highest group as reference. Low volume was defined as fewer than 20 operations per surgeon per year and fewer than 211 cholecystectomies per hospital per year. Differences in outcomes were analysed separately for elective and acute procedures.

Results

The analysis included 154 934 cholecystectomies. Of these, 101 221 (65.3 per cent) were elective and 53 713 (34.7 per cent) were acute procedures. Surgeons with low volumes had longer operating times (P < 0.001) and higher conversion rates in elective (OR 1.35; P = 0.023) and acute (OR 2.41; P < 0.001) operations. Low-volume surgeons also caused more bile duct injuries (OR 1.41; P = 0.033) and surgical complications (OR 1.15; P = 0.033) in elective surgery, but the results were not statistically significant for acute procedures. Low-volume hospitals had more bile duct injuries in both elective (OR 1.75; P = 0.002) and acute (OR 1.96; P = 0.003) operations, and a higher mortality rate after acute surgery (OR 2.53; P = 0.007).

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that operative volumes influence outcomes in cholecystectomy. The results indicate that gallstone surgery should be performed by procedure-dedicated surgeons at hospitals with high volumes of this type of benign surgery.

This registry-based cohort study demonstrated that operative volumes, both for the surgeon and the hospital, influence outcomes of cholecystectomies. The results indicated that gallstone surgery should be performed by procedure-dedicated surgeons at hospitals with high volumes of this type of benign surgery

Introduction

Increased surgical volume is widely associated with improved quality of care, especially for more complicated procedures1–7. Accordingly, centralization of highly specialized procedures to tertiary referral centres has been discussed and implemented worldwide6. For more common and less complex procedures, such as cholecystectomies, the evidence for centralization is more ambiguous. Some previously published studies8–10 showed decreased readmission rates, shorter hospital stays, and decreased overall charges for high-volume surgeons, but argued against the benefit of centralization, because the rates of major complications, bile duct injuries, and mortality were the same, both in experienced and less experienced hands. However, other studies11–13 indicated that high-volume surgeons had better results and fewer complications, especially for patients with acute cholecystitis and other high-risk conditions.

The complication rate in both elective and acute cholecystectomies is considerable. In 2021, the overall complication rate in Sweden was 7.2 per cent for elective surgery and 10.6 per cent for acute surgery, and as high as 28.6 per cent for open and converted procedures14. If high-volume surgeons and high-volume hospitals have lower complication rates, centralization of gallbladder surgery to units with high volumes of cholecystectomies could be a way to further increase patient safety. However, the issue is complicated because laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures, and an important cornerstone of surgical education. Thus, a balance must be achieved between high volume and the need to further educate residents and younger surgeons in laparoscopic surgery.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether the surgeon’s and hospital’s annual operative cholecystectomy volume has an impact on surgical outcomes, with the aim of reducing the knowledge gap to optimal care for patients undergoing cholecystectomy.

Methods

Ethical considerations

This research was approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee in Uppsala, Sweden (2017/022).

Study design

The study was designed as a registry-based cohort study, using data from the Swedish Registry of Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (GallRiks). The cohort was defined as all patients undergoing open and laparoscopic cholecystectomies registered between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2019. The study report was structured in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist15.

Participants and variables

The cohort included all cholecystectomies performed for the indication of colic pain, polyps, and gallstone complications (cholecystitis, pancreatitis, cholangitis, common bile duct stones). Annual volumes for the lead operating surgeon and the registering hospital were calculated for each operation, based on the total volume in the preceding year. The procedures were categorized into volume-based quartiles, giving four subgroups in the outcome analysis. Differences between the groups were analysed in terms of duration of operation, surgical complications (bleeding, visceral perforation, bile duct injury, bile leakage, and abscess), bile duct injury, conversion to open surgery (or open surgery from the start), and 30-day postoperative mortality. Duration of operation was defined as the interval from the start of the procedure until wound closure. Elective and acute procedures (patients admitted acutely and operated on during the same hospital stay) were analysed separately. Patient age, sex, and ASA fitness grade were considered as potential confounders and adjusted for in the multivariable analysis.

Data sources

GallRiks was founded in May 2005 by the Swedish National Board of Health, the Swedish Society of Laparoscopic Surgery, the Swedish Society of Upper Abdominal Surgery, and the Swedish Surgical Association. The registry is supported financially by the Swedish National Health Authorities. The main aim of the registry is to ensure uniform and evidence-based treatment of gallstone disease and high-quality patient care nationwide. In addition, the registry is a reliable source of continuously updated information about indications, outcomes, and the negative aspects of novel techniques. The registry has been described in detail previously16.

Approximately 12 000–14 000 cholecystectomies, in both children and adults, are registered every year and the national coverage of the registry is 94.5 per cent14. Each procedure is registered online by the surgeon, using their unique identification code, which remains constant, even if the surgeon is active at different hospitals. Thirty-day postoperative follow-up is undertaken by a local coordinator. The follow-up and registration of complications are based on information from the medical records. The registry includes patient characteristics, surgery-specific parameters, and information about intraoperative and postoperative adverse events. Intraoperative adverse events include bile duct injury (any lesion to the bile ducts other than the cystic duct), bleeding (requiring intervention, conversion to open surgery or blood transfusion), visceral perforation, and any other reason for the operation to be terminated prematurely. Postoperative adverse events are defined as any complication presenting during the first 30 days after operation. Thirty-day mortality data are retrieved from the National Population Registry.

Bias

Registrations should be carried out online during or immediately after the operation, to reduce the risk of recall bias. The validity of the registry data is monitored by independent reviewers at least every third year. The validation process has shown a high degree of correctness (97 per cent) without missing serious adverse events14,17.

Study size

All cholecystectomies performed in Sweden between 2006 and 2019 were included. The registry started in 2005, but did not reach adequate national coverage until 2006. Cholecystectomies as part of more extensive procedures, such as malignant surgery and transplant surgery, were not included in the data set. The goal was to include as many valid operations as possible to use the full potential of the national registry.

Statistical analysis

Annual operative volumes for the lead surgeon and performing hospital were calculated from the number of cholecystectomies undertaken in the year preceding each procedure. The surgeon’s unique identification number was used when calculating individual volumes. Four volume groups, based on quartile individual and centre volumes, were used in the analysis. The highest quartile was used as reference category. Patient demographics were presented in contingency tables. The association between annual volume and duration of surgery was calculated using a mixed linear model with intercept of the surgeon nested in hospital as random effects, adjusting for age, sex, and ASA grade, with results presented as mean increase in duration of operation. The mixed linear model was selected for analysis of operating time to compensate for the vast time differences among the procedures. The associations between annual volumes and risk of surgical complications, bile duct injury, conversion to open surgery, and 30-day mortality were calculated using generalized estimated equations with an independent correlation structure and robust standard errors, adjusted for patient age, sex, and ASA grade; data are presented as ORs with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Only complete cases were analyzed in the models. P < 0.050 was considered significant. Spline functions with two knots at the 33rd and 67th percentiles were used to plot mean duration of operation, risk of surgical complications, bile duct injury, and conversion to open surgery with respect to operative volume, with pointwise 95 per cent confidence intervals. A logarithmic scale for operative volume was used in the diagrams.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS® version 28.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and diagrams were created with R version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

During the 14 years from 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2019, a total of 162 472 patients were registered after undergoing laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy. The included operations were carried out by 2637 surgeons, from 89 different centres in Sweden. Cholecystectomies from 2006 were excluded from the analysis because no volumes could be calculated. This resulted in a database of 154 934 cholecystectomies, of which 101 221 (65.3 per cent) were elective and 53 713 (34.7 per cent) were acute procedures (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart

Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. The mean(s.d.) number of procedures undertaken during the preceding year was 24(23) (range 0–210) for the individual surgeon and 234(127) (range 0–515) for the hospital. Volume data were divided into quartiles for the analysis. For the individual surgeon, these were: quartile 1, 9 or fewer; quartile 2, 10–19; quartile 3, 20–33; and quartile 4, more than 33 cholecystectomies per year. Groups for the registering hospital were: quartile 1, 136 or fewer; quartile 2, 137–210; quartile 3, 211–305; and quartile 4, over 305 cholecystectomies per year. To facilitate presentation of the results, a cut-off between low and high volume was set between quartiles 2 and 3, giving a definition of low annual volume as fewer than 20 operations for the individual and fewer than 211 operations for the hospital. Of the 2637 surgeons, 1061 (40.2 per cent) carried out at least 20 procedures per year and 40 (44.9 per cent) of the 89 centres registered more than 210 operations per year. The follow-up time was 30 days, based on the organization of the registry.

Table 1.

Demographics of included patients

| Elective surgery (n = 101 221) |

Acute surgery (n = 53 713) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| ȃ< 50 | 31 273 (30.9) | 16 220 (30.2) |

| ȃ≥ 50 | 69 854 (69.0) | 37 250 (69.4) |

| ȃMissing | 94 (0.1) | 243 (0.4) |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 30 953 (30.6): 70 261 (69.4) | 21 980 (40.9): 31 705 (59.0) |

| ȃMissing | 7 (0.0) | 28 (0.1) |

| ASA fitness grade | ||

| ȃI | 50 216 (49.6) | 22 213 (41.4) |

| ȃII–III | 43 579 (43.1) | 24 793 (46.1) |

| ȃ≥ IV | 7303 (7.2) | 6302 (11.7) |

| ȃMissing | 123 (0.1) | 405 (0.8) |

| Surgical approach | ||

| ȃLaparoscopic | 93 568 (92.4) | 42 340 (78.8) |

| ȃLaparoscopic converted to open | 3864 (3.8) | 5609 (10.5) |

| ȃOpen | 2305 (2.3) | 5324 (9.9) |

| ȃOther techniques | 1484 (1.5) | 440 (0.8) |

Values are n (%).

Cholecystectomy data

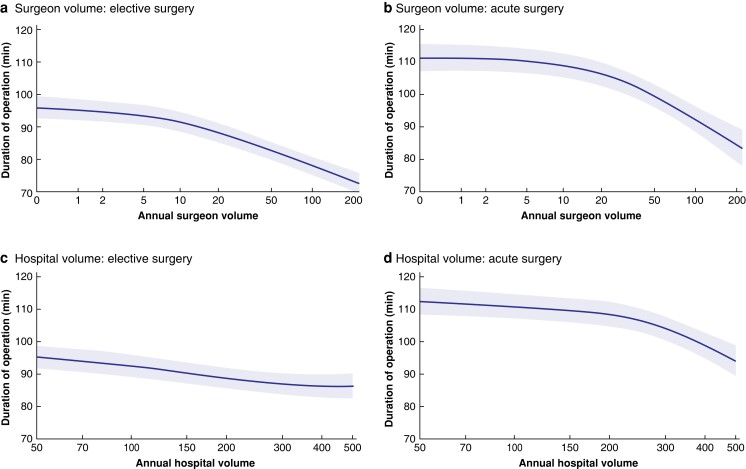

The mean(s.d.) duration of surgery was 92(45) min for elective surgery and 115(55) min for acute surgery. The mean duration for the different volume categories is shown in Table 2. The operating time decreased significantly with increasing volumes for both the individual surgeon and the hospital, in both elective and acute surgery (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Mixed-model analysis for surgeon and hospital volumes with duration of operation as outcome

| Volume per year | Elective surgery‡ | Acute surgery§ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of surgery (min)* | Increase† | P | Duration of surgery (min)* | Increase† | P | |

| Surgeon | ||||||

| ȃ≤ 9 | 103(44) | 10.80 (9.85, 11.75) | <0.001 | 123(53) | 10.29 (8.60, 11.98) | <0.001 |

| ȃ10–19 | 97(45) | 6.70 (6.10, 7.89) | <0.001 | 120(56) | 8.04 (6.43, 9.66) | <0.001 |

| ȃ20–33 | 89(44) | 3.65 (2.85, 4.45) | <0.001 | 111(55) | 3.59 (2.08, 5.09) | <0.001 |

| ȃ> 33 | 80(42) | – | 99(53) | – | ||

| Hospital | ||||||

| ȃ≤ 136 | 94(45) | 4.41 (2.77, 6.06) | <0.001 | 120(54) | 3.63 (0.92, 6.34) | 0.009 |

| ȃ137–210 | 95(46) | 2.76 (1.26, 4.25) | <0.001 | 119(55) | 1.99 (−0.47, 4.45) | 0.113 |

| ȃ211–305 | 93(45) | 1.31 (−0.02, 2.62) | 0.053 | 118(57) | 4.65 (2.56, 6.75) | <0.001 |

| ȃ> 305 | 85(42) | – | 104(52) | – | ||

*Values are mean(s.d.); †values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, and ASA grade. Some ‡235 and §662 patients were excluded owing to missing values.

Fig. 2.

Spline functions for mean duration of operation for elective and acute procedures, with respect to operative volume for surgeons and hospitals

Duration of operation for a elective and b acute operations according to surgeon volume, and c elective and d acute operations according to hospital volume. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Cholangiography was performed in 91.1 per cent of elective and 92.3 per cent of acute procedures, according to the standard routine in Sweden. Common bile duct stones were found in 7.5 per cent of elective and 19.1 per cent of acute cholecystectomies.

Complications

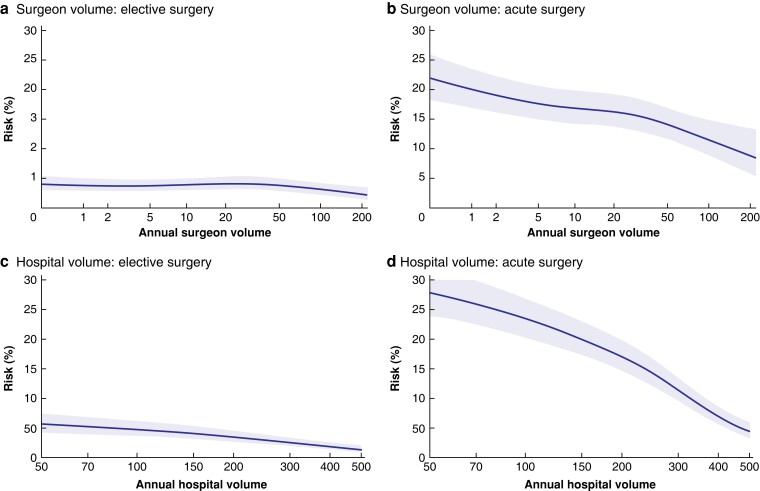

The total rate of surgical complications (bleeding, visceral perforation, bile duct injury, bile leakage, abscesses) was 3.4 per cent in elective and 5.3 per cent in acute surgery. Surgical complication rates were slightly higher for surgeons with annual volumes of between 10 and 33 operations in elective surgery compared with the highest-volume category, although there was no difference between the lowest and highest quartile (Table 3). However, no significant difference was evident in acute surgery. There was no difference in surgical complication rate between the volume categories at the hospital level (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Generalized estimated equations for surgeon and hospital volumes and surgical outcomes

| Volume per year | Elective surgery* | Acute surgery† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | P | OR | P | ||

| Surgical complications | Surgeon | ||||

| ȃ≤ 9 | 1.08 (0.95, 1.23) | 0.257 | 1.08 (0.93, 1.26) | 0.312 | |

| ȃ10–19 | 1.15 (1.01, 1.31) | 0.033 | 1.01 (0.86, 1.18) | 0.926 | |

| ȃ20–33 | 1.16 (1.02, 1.31) | 0.025 | 0.96 (0.82, 1.12) | 0.609 | |

| ȃ> 33 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Hospital | |||||

| ȃ≤136 | 1.09 (0.95, 1.26) | 0.203 | 1.06 (0.91, 1.24) | 0.457 | |

| ȃ137–210 | 1.07 (0.93, 1.23) | 0.334 | 1.04 (0.91, 1.19) | 0.526 | |

| ȃ211–305 | 0.94 (0.83, 1.06) | 0.319 | 0.95 (0.83, 1.09) | 0.474 | |

| ȃ> 305 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Bile duct injury | Surgeon | ||||

| ≤ 9 | 1.41 (1.03, 1.95) | 0.033 | 1.03 (0.71, 1.49) | 0.875 | |

| ȃ10–19 | 1.58 (1.15, 2.17) | 0.005 | 0.88 (0.60, 1.30) | 0.528 | |

| ȃ20–33 | 1.33 (0.98, 1.80) | 0.063 | 0.98 (0.65, 1.48) | 0.913 | |

| ȃ> 33 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Hospital | |||||

| ≤ 136 | 1.75 (1.23, 2.49) | 0.002 | 1.52 (0.95, 2.44) | 0.082 | |

| ȃ137–210 | 1.97 (1.39, 2.81) | <0.001 | 1.96 (1.25, 2.94) | 0.003 | |

| ȃ211–305 | 1.42 (0.96, 2.09) | 0.078 | 1.84 (1.21, 2.79) | 0.004 | |

| ȃ> 305 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Conversion to open surgery | Surgeon | ||||

| ȃ≤ 9 | 1.35 (1.04, 1.75) | 0.023 | 2.41 (1.91, 3.04) | <0.001 | |

| ȃ10–19 | 1.39 (1.07, 1.80) | 0.014 | 1.68 (1.33, 2.11) | <0.001 | |

| ȃ20–33 | 1.26 (1.04, 1.59) | 0.020 | 1.28 (1.05, 1.56) | 0.017 | |

| ȃ> 33 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Hospitalȃ | |||||

| ȃ≤136 | 2.66 (1.95, 3.63) | <0.001 | 3.59 (2.96, 4.34) | <0.001 | |

| ȃ137–210 | 2.10 (1.64, 2.69) | <0.001 | 3.11 (2.55, 3.79) | <0.001 | |

| ȃ211–305 | 1.41 (1.14, 1.75) | 0.002 | 1.78 (1.48, 2.14) | <0.001 | |

| ȃ> 305 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| 30-day mortality | Surgeon | ||||

| ȃ≤ 9 | 1.74 (0.80, 3.81) | 0.164 | 1.49 (0.83, 2.68) | 0.180 | |

| ȃ10–19 | 1.32 (0.58, 3.02) | 0.513 | 1.44 (0.78, 2.68) | 0.248 | |

| ȃ20–33 | 0.59 (0.22, 1.56) | 0.286 | 1.20 (0.67, 2.18) | 0.540 | |

| ȃ> 33 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Hospital | |||||

| ȃ≤136 | 2.07 (0.87, 4.95) | 0.102 | 2.53 (1.29, 4.94) | 0.007 | |

| ȃ137–210 | 1.84 (0.74, 4.56) | 0.190 | 2.09 (1.09, 3.98) | 0.026 | |

| ȃ211–305 | 0.77 (0.26, 2.32) | 0.640 | 1.76 (0.88, 3.51) | 0.110 | |

| ȃ>305 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, and ASA grade. Some *216 and †648 patients were excluded owing to missing values.

Fig. 3.

Spline functions for surgical complications in elective and acute procedures, with respect to operative volume for surgeons and hospitals

Surgical complication risk for a elective and b acute operations according to surgeon volume, and c elective and d acute operations according to hospital volume. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

The total 30-day complication rate, including surgical complications and all other registered intraoperative and postoperative complications (such as wound infections, thrombosis, cardiac and pulmonary complications, mortality) was 8.5 per cent for elective procedures and 13.3 per cent for acute procedures. The total complication rate was slightly higher for surgeons with annual volumes of 9 or fewer procedures (OR 1.11; P = 0.027) and volumes between 10 and 19 (OR 1.12; P = 0.017) in elective surgery, but no significant disparity could be seen in the total complication rate between the other groups at either the individual or hospital level (data not shown).

Bile duct injury

The risk of bile duct injury was 0.3 per cent in elective and 0.4 per cent in acute surgery, including any lesion to the bile ducts diagnosed during or after the operation, except for the cystic duct. Surgeons with a low annual volume caused more bile duct injuries in elective surgery. No significant disparity could be seen for acute surgery. Hospitals with low annual volumes had a higher frequency of bile duct injuries, in both elective and acute procedures (Table 3 and Fig. 4). Bile leakage was diagnosed after the operation in 1118 (1.1 per cent) of the elective and 876 (1.6 per cent) of the acute procedures. The leakage was described as leakage from the cystic duct in 441 (0.4 per cent) elective and 361 (0.7 per cent) acute procedures, and from an unknown location in 304 (0.3 per cent) elective and 263 (0.5 per cent) acute operations. No statistically significant correlation between leakage from the cystic duct and operative volume was evident at either the individual or hospital level.

Fig. 4.

Spline functions for bile duct injury in elective and acute procedures, with respect to operative volume for surgeons and hospitals

Bile duct injury risk for a elective and b acute operations according to surgeon volume, and c elective and d acute operations according to hospital volume. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Conversion to open surgery

Surgical approaches in the cohort are recorded in Table 1. The risk of an open operation or conversion to open surgery was significantly higher for all quartiles in elective and acute surgery compared with the highest-volume category, for both surgeons and hospitals and, most notably, for acute surgery (Table 3 and Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Spline functions for conversion to open surgery in elective and acute procedures, with respect to operative volume for surgeons and hospitals

Risk of conversion to open surgery for a elective and b acute operations according to surgeon volume, and c elective and d acute operations according to hospital volume. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Mortality

The overall 30-day mortality rate was 0.05 per cent after elective and 0.33 per cent after acute surgery. It was significantly higher for hospitals with low operative volumes of acute surgery (Table 3).

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that the surgeon’s and hospital’s cholecystectomy volumes have an impact on duration of operation and surgical outcomes. This indicates that gallbladder surgery should be performed by surgeons with high operative volumes at high-volume hospitals, to decrease the frequency of adverse events and improve healthcare for patients with gallstone-related diseases. However, because gallstone surgery forms an important part of surgical education, senior advice and assistance is essential during the learning process, and a balance between high volume and education must be achieved.

According to the present results, high-volume surgeons have shorter operating times and are less prone to convert to open surgery. The same tendency is shown by high-volume hospitals. The association between increased operative volumes for cholecystectomies and decreased operating time, and costs, has been demonstrated previously18,19. Conversion to open surgery is associated with significantly longer hospital stay and prolonged recovery time20. However, open surgery may be the safest alternative in selected patients for whom laparoscopic access is unsatisfactory, owing to anatomical variations or extensive inflammation. The decision to convert may reflect an ability to reconsider the circumstances and choose a new approach, based on extensive experience with gallstone surgery, but it can also reflect a lack of skills to solve complicated situations laparoscopically.

In this study, low-volume surgeons had more bile duct injuries and slightly more surgical complications than high-volume surgeons in elective surgery, but there was no difference between the volume categories for acute surgery. Low-volume hospitals had a higher frequency of bile duct injuries in both acute and elective operations. The association between high volume and decreased levels of adverse events in acute surgery has been observed in other studies9,11. The statistically non-significant results for surgical complications and bile duct injuries in acute surgery are somewhat surprising. They may be explained by residual confounding related to volume and outcome, or the fact that differences in outcomes after acute surgery are influenced to a greater extent by other factors. Previously published studies21–24 have suggested that patient characteristics, such as male sex, age, and previous upper abdominal surgery, or the presence of cholecystitis, have a greater impact on outcomes than the surgeon’s operative volume. Although the mortality rate after gallbladder surgery is low, 30-day mortality doubled in hospitals with less extensive volumes. This was also observed in the Scottish population by Harrison et al.12 in 2012.

Some limitations should be mentioned. The national coverage of 94.5 per cent and the 97 per cent follow-up are strengths of the registry and the study, as well as the magnitude of the database14,17. There are, however, obvious limitations with registry-based studies. Intraoperative data should be registered as soon as possible after the operation, but this may vary as a result of different routines. Therefore, incorrect and missing data may be introduced. The complication rate is based on information from the medical records. It is possible that patients with complications are treated at a hospital other than the one in which they underwent surgery. This may be a source of bias when comparing high- and low-volume units, especially for elective operations at private clinics and for acute operations, which are usually performed at the local hospital, even if the patient originates from another part of the country. Hospitals in the same region in Sweden often use the same system for medical records. The estimate of operative volumes in this study is based on the lead operating surgeon. However, the most senior colleague may be registered as the lead surgeon, even if a major part of the operation is performed by a less experienced surgeon. This may also have affected the association between surgeon volume and duration of operation. Because annual volumes are based on the year preceding the cholecystectomy, experienced surgeons may have been classified incorrectly as low-volume surgeons if they mainly assisted colleagues undergoing training. Surgical volumes may also differ over time owing to education, research, parental leave, level of competence of other members of the surgical team, surgical equipment, and reorganization. Furthermore, surgeons may have acquired advanced skills from performing other surgical procedures.

Patient age, sex, and ASA grade were considered as potential confounders and included in the outcome analysis. However, BMI was not adjusted for. The registry’s BMI variable was mandatory only from 2010, so there is a lot of missing information in the cohort. Older age and male sex are known risk factors for a more complex procedure, and are common predictors of conversion to open surgery25,26. ASA grade indirectly includes BMI and should also be taken into consideration, as hospitals with elective profiles, such as private clinics, generally operate on healthier patients. The reason for conversion and other patient co-morbidities were not included in the analysis. Furthermore, the severity of the inflammation in acute surgery was not registered, which may be a confounding factor.

The spline diagrams show wide confidence intervals for the lowest- and highest-volume categories. Case mix and individual surgical skill certainly result in variation at the individual level. For hospitals, smaller units might have a few active, high-volume surgeons contributing to the total volume, and other hospitals, such as universities, may have many low-volume surgeons. A high individual volume, as well as experience with more complicated gallstone operations, can be maintained by performing both elective and acute procedures, and by avoiding dividing gallstone surgery between multiple units and individuals. In addition, gallbladder surgery is, and will probably continue to be, an important part of surgical education. The volume–outcome relationship demonstrated in this study highlights the importance of having senior advice available when needed, especially for surgeons with limited experience of gallstone surgery.

Based on the present results, it is difficult to recommend a minimum annual volume of cholecystectomies. For most variables, there seems to be a decrease in adverse events, or at least a flattened curve, for the two highest-volume categories. The definition of low volume as fewer than 20 operations per individual and fewer than 211 operations per hospital each year is comparable to that in other studies8,10–13,21,22 and might be an amount to strive for. Here, less than 50 per cent of all surgeons and hospitals achieved this. It would not be realistic to encourage a reduction in the number of surgeons performing cholecystectomies in Sweden based on these limits. However, the results emphasize the importance of procedure-dedicated and accredited surgeons, as well as the development of hospitals with considerable experience of treating and optimizing patients with gallstone-related diseases. Previous studies of more advanced surgical procedures have shown that high-volume institutions have better outcomes, not only because of higher volumes, but also owing to the presence of multidisciplinary teams with well established routines, standardized perioperative care, and specialists available around the clock6. Important factors to strive for in gallstone surgery are efficient day care for elective surgery, routines for acute cholecystectomies (to prioritize and operate on patients without delay), and competence in the perioperative removal of common bile duct stones. However, centralizing healthcare must be carried out taking population density into consideration. Centralization of malignant surgery in Sweden has affected organization such that many university clinics perform limited volumes of benign general surgery, such as cholecystectomies14. For gallstone surgery, the referral centre may be a regional or county hospital27. This is a way to provide access to a high-volume centre, within a reasonable distance, for the entire population.

These results are based on the Swedish population, geography, and surgical setting, which affects their generalizability. They should be interpreted with caution in countries with other healthcare structures. Nevertheless, the study emphasizes the importance of surgical volume at the individual and hospital level in less complex procedures, such as cholecystectomies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. Trickett for proof-reading.

Contributor Information

My Blohm, Department of Clinical Sciences, Intervention and Technology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Department of Surgery, Mora Hospital, Mora, Sweden; Center for Clinical Research, Uppsala University, Falun, Sweden.

Gabriel Sandblom, Department of Clinical Science and Education, South General Hospital, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Lars Enochsson, Department of Clinical Sciences, Intervention and Technology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Department of Surgical and Perioperative Sciences, Surgery, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden; Department of Surgery, Sunderby Hospital, Luleå, Sweden.

Mats Hedberg, Department of Surgery, Mora Hospital, Mora, Sweden.

Mikael Franko Andersson, Department of Clinical Science and Education, South General Hospital, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Johanna Österberg, Department of Clinical Sciences, Intervention and Technology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Department of Surgery, Mora Hospital, Mora, Sweden; Center for Clinical Research, Uppsala University, Falun, Sweden.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Center for Clinical Research, Falun (CKFUU-697181), and Stockholm Regional Council, Stockholm (ALF 20190336).

Disclosure

G.S., L.E., and J.Ö. are unpaid members of the leadership board of GallRiks. J.Ö. has received payment for a lecture from Baxter, Mölnlycke. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

Data availability

The research data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:511–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maruthappu M, Gilbert BJ, El-Harasis MA, Nagendran M, McCulloch P, Duclos Aet al. The influence of volume and experience on individual surgical performance: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2015;261:642–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Birkmeyer JD, Sun YT, Wong SL, Stukel TA. Hospital volume and late survival after cancer surgery. Ann Surg 2007;245:777–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borowski DW, Bradburn DM, Mills SJ, Bharathan B, Wilson RG, Ratcliffe AAet al. Volume–outcome analysis of colorectal cancer-related outcomes. Br J Surg 2010;97:1416–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2128–2137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vonlanthen R, Lodge P, Barkun JS, Farges O, Rogiers X, Soreide Ket al. Toward a consensus on centralization in surgery. Ann Surg 2018;268:712–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med 1979;301:1364–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abelson JS, Spiegel JD, Afaneh C, Mao J, Sedrakyan A, Yeo HL. Evaluating cumulative and annual surgeon volume in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery 2017;161:611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Terho P, Sallinen V, Leppaniemi A, Mentula P. Does the surgeon’s caseload affect the outcome in laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2020;30:522–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zehetner J, Leidl S, Wuttke ME, Wayand W, Shamiyeh A. Conversion in laparoscopic cholecystectomy in low- versus high-volume hospitals: is there a difference? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2010;20:173–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Csikesz NG, Singla A, Murphy MM, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Surgeon volume metrics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:2398–2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harrison EM, O’Neill S, Meurs TS, Wong PL, Duxbury M, Paterson-Brown Set al. Hospital volume and patient outcomes after cholecystectomy in Scotland: retrospective, national population based study. BMJ 2012;344:e3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hobbs MS, Mai Q, Knuiman MW, Fletcher DR, Ridout SC. Surgeon experience and trends in intraoperative complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2006;93:844–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. GallRiks . The Swedish Registry of Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Annual Report (2021). [cited 2022 May 01] Available from: https://www.ucr.uu.se/gallriks/for-vardgivare/rapporter/arsrapporter.

- 15. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JPet al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Enochsson L, Thulin A, Osterberg J, Sandblom G, Persson G. The Swedish Registry Of Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (GallRiks): a nationwide registry for quality assurance of gallstone surgery. JAMA Surg 2013;148:471–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rystedt J, Montgomery A, Persson G. Completeness and correctness of cholecystectomy data in a national register—GallRiks. Scand J Surg 2014;103:237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi HY, Lee KT, Chiu CC, Lee HH. The volume–outcome relationship in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a population-based study using propensity score matching. Surg Endosc 2013;27:3139–3145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stahl CC, Udani S, Schwartz PB, Aiken T, Acher AW, Barrett JRet al. Surgeon variability impacts costs in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: the volume–cost relationship. J Gastrointest Surg 2021;25:195–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keus F, de Jong JA, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (4)CD006231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abraham S, Nemeth T, Benko R, Matuz M, Vaczi D, Toth Iet al. Evaluation of the conversion rate as it relates to preoperative risk factors and surgeon experience: a retrospective study of 4013 patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BMC Surg 2021;21:151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murphy MM, Ng SC, Simons JP, Csikesz NG, Shah SA, Tseng JF. Predictors of major complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: surgeon, hospital, or patient? J Am Coll Surg 2010;211:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sinha S, Hofman D, Stoker DL, Friend PJ, Poloniecki JD, Thompson MMet al. Epidemiological study of provision of cholecystectomy in England from 2000 to 2009: retrospective analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics. Surg Endosc 2013;27:162–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Donkervoort SC, Dijksman LM, Versluis PG, Clous EA, Vahl AC. Surgeon’s volume is not associated with complication outcome after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis Sci 2014;59:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Panni RZ, Strasberg SM. Preoperative predictors of conversion as indicators of local inflammation in acute cholecystitis: strategies for future studies to develop quantitative predictors. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2018;25:101–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wakabayashi G, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJet al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: surgical management of acute cholecystitis: safe steps in laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2018;25:73–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lindqvist L, Sandblom G, Nordin P, Hemmingsson O, Enochsson L. Regional variations in the treatment of gallstone disease may affect patient outcome: a large, population-based register study in Sweden. Scand J Surg 2020;110:335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The research data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.