Abstract

Gender identity and sexual attraction are important determinants of health. This study reports distributions of gender identity and sexual attraction among Canadian youth using data from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth. Among youth aged 12 to 17, 0.2% are nonbinary and 0.2% are transgender. Among youth aged 15 to 17, 21.0%, comprising more females than males, report attraction not exclusive to the opposite gender. Given known associations between health and gender and sexual attraction, oversampling of sexual minority groups is recommended in future studies to obtain reliable estimates for identifying inequities and informing policy.

Keywords: gender identity, sexual orientation, youth, transgender persons, sexual and gender minorities, Canada

Highlights

Gender and sexual attraction as a dimension of sexual orientation are important determinants of health among youth.

Collecting gender and sexual attraction information as a routine part of public health surveillance is important for identifying inequities and informing policy.

This study provides nationally representative estimates for the distribution of gender and sexual attraction among Canadian youth.

This study identifies populations (nonbinary, transgender and same gender–attracted youth) that require oversampling or other approaches to ensure that reliable estimates can be obtained in public health surveillance.

Introduction

Gender and sexual orientation are important determinants of health among adults1-5 and youth,6-10 and data for these variables should be collected routinely in public health surveillance to identify inequities and inform policy.

Statistics Canada has recently developed data standards for sex and gender,11 and undertaken consultations for similar standards for sexual orientation.12 Gender refers to “a person’s social or personal identity as a man [male], woman [female] or nonbinary person.”13 Gender categories and normative expressions of gender vary across historical, cultural and social contexts. Sex at birth, meanwhile, is assigned based on a collection of anatomical and physiological characteristics.13 The term “cisgender” encompasses those whose gender identity corresponds to their sex at birth. “Transgender” encompasses those whose gender identity does not correspond to their sex at birth.14 “Nonbinary” encompasses those whose gender identity is not exclusively male or female.14 “Nonbinary” is often used as an umbrella term for gender identities outside the gender binary of male/female, including persons identifying as agender, genderqueer and gender fluid.14,15 Nonbinary persons may or may not identify themselves as transgender.14

Sexual orientation comprises three dimensions: sexual attraction (the sexes or genders of people to whom an individual is attracted), sexual identity (the term that one assigns oneself; e.g. heterosexual, bisexual, lesbian, gay) and sexual behaviour (the sexes or genders of people with whom an individual has sexual experiences).16,17 So-called “sexual minorities” are typically those with nonheterosexual attraction, identity or behaviour (i.e. not only attracted to the opposite sex/gender; identifying as nonheterosexual; having had same-sex/gender sexual experiences).17 Sexual orientation is distinct from “romantic orientation,” which refers to the sexes or genders of those with whom an individual desires to have romantic relationships.18 Finally, “Two-Spirit” is a term used by Indigenous peoples across North America that encompasses a broad range of gender and sexual identities, as well as a diversity of terms from a number of Indigenous languages.19

Studies have found that nonbinary, transgender, Two-Spirit and sexual minority persons in Canada face a broad range of health and social inequities compared to cisgender and heterosexual persons,1-5,19,20 including poorer mental health outcomes among youth.6,7

The distribution of sexual orientation can vary depending on which dimension is examined. Data collection for each dimension is not always possible due to practical constraints, and not all dimensions may be relevant or appropriate to measure, depending on the population being studied. For example, sexual identity develops over time and is subject to change, especially during adolescence and young adulthood.17,21 Sexual behaviour is also subject to change—many youth have not yet had sexual experiences,17 and behaviours are affected by opportunity as well as identity and attraction.22 While sexual attraction is also subject to change, studies have found that sexual attraction questions are the easiest to understand among youth and that youth consider attraction to be the principal element of sexual orientation.23,24

Few studies have examined the distribution of gender and sexual attraction (or other dimensions of sexual orientation) among Canadian youth.1,25,26 This is a major gap, given the known health and social inequities associated with nonbinary gender, transgender, Two-Spirit and minority sexual attraction among youth. This study reports distributions for gender identity and sexual attraction among a nationally representative sample of Canadian youth.

Methods

Data source

This study used data from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (CHSCY), a cross-sectional survey conducted by Statistics Canada.27 Data collection occurred between 11 February and 2 August 2019. The CHSCY covered a nationally representative sample of children and youth aged 1 to 17 years, excluding those living on First Nation reserves and other Aboriginal settlements, those living in foster homes and the institutionalized population. The sampling frame consisted of beneficiaries of the Canada Child Benefit, covering 98% of the population aged 1 to 17 in all provinces and 96% in all territories. The CHSCY is a Statistics Canada survey conducted under the authority of the Statistics Act, and informed consent and assent were obtained from all participants. The CHSCY and its methodology are further described elsewhere.27

This study focusses on youth aged 12 to 17 years. Data were collected by electronic questionnaire or telephone interview. All youth were asked about gender identity, while only youth aged 15 to 17 were asked about sexual attraction. Other dimensions of sexual orientation (i.e. sexual identity and behaviour) were not included in the CHSCY.

There were 11077 respondents aged 12 to 17 in the 2019 CHSCY (5301 aged 15 to 17; response rate: 41.3%). Survey weights were provided by Statistics Canada to account for sampling and nonresponse and generate nationally representative estimates. Analyses were restricted to those with available data, totalling 11064 respondents (99.9%) for gender identity, and 5254 respondents (99.1%) for sexual attraction.

Measures

Sex

Youth were asked, “What was your sex at birth? Sex refers to sex assigned at birth.” Response options were “male” and “female.”

Gender identity

Youth were asked, “Gender refers to current gender which may be different from sex assigned at birth and may be different from what is indicated on legal documents. What is your gender?” Response options were “male,” “female,” “or please specify.” Youth who identified as a gender other than male or female were classified as “nonbinary.”

Cisgender or non-cisgender

Youth whose gender corresponded with their sex at birth were classified as “cisgender.” Youth who identified as a gender other than male or female were classified as “nonbinary.” Youth who identified as the opposite gender to their sex at birth were classified as “transgender.” While nonbinary persons may or may not identify themselves as transgender, Statistics Canada data standards consider nonbinary and transgender persons as constituting different categories, with transgender persons identifying as part of the gender binary of male/female.14 Since not all categories were reportable due to low sample sizes and high sampling variability, nonbinary and transgender youth were grouped together as “non-cisgender”

Sexual attraction

Youth aged 15 to 17 were asked whether they were “only attracted to males”; “mostly attracted to males”; “equally attracted to females and males”; “mostly attracted to females”; “only attracted to females”; or “not sure.” Cisgender and transgender youth were classified as “only attracted to the opposite gender”; “attracted to both genders”; “only attracted to the same gender”; or “not sure” based on their reported sexual attraction and self-identified gender. Nonbinary youth were classified as “attracted to both genders”; “only attracted to one gender”; or “not sure.”

Males and females classified as “attracted to both genders” were further disaggregated as: “mostly attracted to the opposite gender”; “equally attracted to both genders”; or “mostly attracted to the same gender,” where there was sufficient sample size.

Analyses by sexual attraction, particularly for the inclusion of nonbinary youth, were not always possible due to insufficient sample size. Therefore, for the current analysis, all youth were classified as having “attraction exclusive to the opposite gender”; or “attraction not exclusive to the opposite gender” if they were attracted to both genders, the same gender, not sure or if they self-identified as nonbinary gender. Similar classifications have been used in other studies.28,29 Those reporting “not sure” were excluded as a sensitivity analysis.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate percentages and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for gender identity measures overall and stratified by age group (12–14 and 15–17 years). Descriptive statistics were used to calculate percentages and 95% CIs for sexual attraction measures overall and stratified by gender (male/female). All statistics were calculated using survey weights provided by Statistics Canada to be nationally representative. We calculated 95% CIs using bootstrap weights. Two-tailed hypothesis tests were used to assess differences in gender by age and sexual attraction by gender under a significance level of 0.05. Analyses were conducted in SAS EG 7.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, US).

Results

Gender identity

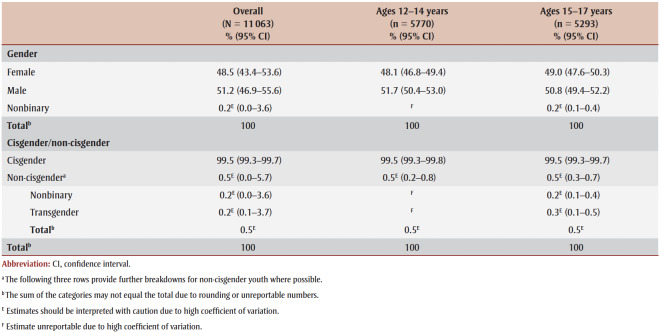

Among Canadian youth aged 12 to 17years, approximately 0.5% were classified as non-cisgender, with 0.2% identifying as nonbinary and 0.2% transgender (Table1). The percentage of youth classified as non-cisgender did not differ by age group.

Table 1. Gender identities of Canadian youth aged 12 to 17 years overall and by age, 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

Sexual attraction

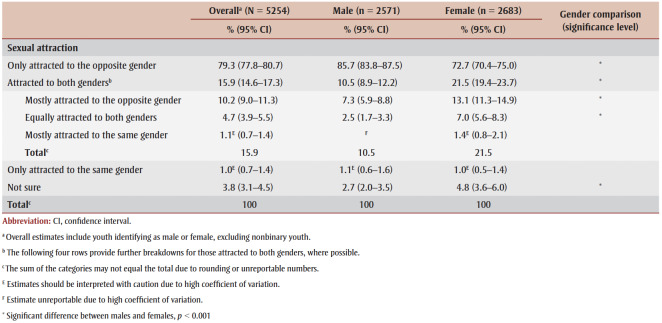

Among all youth aged 15 to 17 years, 79.0% reported attraction exclusive to the opposite gender, whereas 21.0% reported attraction not exclusive to the opposite gender (attracted to both genders, not sure of their sexual attraction, or nonbinary). When youth who were not sure of their sexual attraction (n=190, 3.6%) were excluded in a sensitivity analysis, 17.8% of youth reported attraction not exclusive to the opposite gender (23.7% of females, 11.9% of males).

Among cisgender and transgender youth aged 15 to 17 years who identified as male or female, 79.3% were only attracted to the opposite gender, 15.9% were attracted to both genders, 1.0% were only attracted to the same gender and 3.8% were not sure (Table 2). The majority of youth attracted to both genders were mostly attracted to the opposite gender. Females were less likely to only be attracted to the opposite gender than males. All transgender youth reported attraction to both genders or only to the same gender (percentage unreportable due to small sample size). Among nonbinary youth aged 15 to 17 years, 69.9% reported attraction to both genders. The remainder were attracted to one gender or not sure of their sexual attraction (percentages unreportable due to small sample size).

Table 2. Sexual attraction of Canadian male and female youth aged 15 to 17 years, overall and by gender, 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

Analyse

Cette tude prsente les premires estimations reprsentatives l’chelle nationale de la rpartition des identits de genre et de l’attirance sexuelle chez les jeunes Canadiens de 12 17ans.

Identit de genre

Parmi la population de jeunes tudie, 0,2% se sont identifis comme non binaires et 0,2% comme ayant une identit de genre diffrente du sexe qui leur a t assign la naissance (c’est‑‑dire comme personnes transgenres). Ces estimations concordent de manire gnrale avec les donnes du Recensement de 2021, dans lequel 0,79% des Canadiens de 15 24ans se sont identifis comme personnes non binaires ou transgenres25, ainsi qu’avec les rsultats de l’enqute sur la sant des adolescents de la Colombie‑Britannique ralise en 2013, o moins de 1% des rpondants s’taient identifis comme transgenres26. De mme, 1,2% des rpondants se sont identifis comme personnes transgenres dans une enqute populationnelle ralise en Nouvelle‑Zlande auprs d’lves du secondaire30, tandis que cette proportion tait de 1,1% dans une enqute reprsentative l’chelle nationale ralise aux tats‑Unis auprs de jeunes de 14 17 ans31. Bien qu’elles reprsentent une petite proportion de la population, les personnes non binaires et transgenres se heurtent un large ventail d’iniquits1-7. Il faudrait envisager de procder un surchantillonnage de ces groupes lors de la conception d’tudes de surveillance et de recherche afin d’obtenir des estimations fiables et de tirer des conclusions quant leur sant et aux iniquits auxquelles ils font face32.

Attirance sexuelle

Un pourcentage considrable de jeunes (21,0%) a dclar avoir une attirance non exclusive envers des personnes du genre oppos. Ce chiffre est similaire au pourcentage de jeunes ayant dclar une identit sexuelle autre qu’htrosexuelle dans l’enqute sur la sant des adolescents de la Colombie‑Britannique de 2013 (19%)26, et considrablement plus leve que dans l’Enqute sur la sant dans les collectivits canadiennes de 2015 pour les jeunes de 15 24ans (5,6%)1. Les carts dans les estimations peuvent s’expliquer par des diffrences relatives aux dimensions de l’orientation sexuelle et la population value, aux choix de rponse offerts ou encore aux tendances au fil du temps. En effet, on a observ au fil des annes une augmentation de la proportion de personnes qui s’identifient comme personnes gaies, lesbiennes ou bisexuelles, en particulier chez les jeunes gnrations33. Ailleurs qu’au Canada, on a constat par exemple que 25,6% des jeunes de 14 17ans aux tats‑Unis ont dclar avoir une attirance non exclusive envers des personnes du genre oppos dans une enqute reprsentative l’chelle nationale31, comparativement seulement 11,1% des jeunes de 14 15ans en Australie34.

l’instar des tudes portant sur l’identit sexuelle chez les jeunes et les adultes du Canada1,26, les femmes taient plus susceptibles que les hommes de dclarer avoir une attirance non exclusive envers des personnes du genre oppos. Cette diffrence est en grande partie attribuable au fait que les femmes sont plus nombreuses dclarer avoir une attirance envers des personnes des deux genres ou tre incertaines de leur attirance.

La variabilit de l’chantillonnage tait leve pour le pourcentage de jeunes attirs surtout et attirs seulement par des personnes du mme genre. Le pourcentage de garons attirs surtout par des personnes du mme genre n’a pas pu tre publi, tout comme la rpartition de l’attirance sexuelle chez les jeunes non binaires ou transgenres. De manire gnrale, on recommande de publier les estimations pour toutes les catgories d’attirance sexuelle lorsque cela est possible, car l’tat de sant peut diffrer d’un groupe l’autre8, et cet lment devrait tre pris en compte dans le plan d’chantillonnage des tudes de surveillance.

Pour valuer les diffrences relatives l’tat de sant selon l’attirance sexuelle l’aide des donnes actuelles, il peut s’avrer ncessaire de regrouper certaines catgories (par exemple l’attirance exclusive envers des personnes du genre oppos comparativement attirance non exclusive envers des personnes du genre oppos) afin de pouvoir fournir des estimations fiables. La plupart des jeunes qui n’taient pas attirs exclusivement par des personnes du genre oppos taient attirs surtout par des personnes du genre oppos. Des tudes laissent entendre que certaines de ces personnes pourraient avoir une identit htrosexuelle ou adopter des comportements htrosexuels35. Mme si les jeunes qui n’taient pas certains de leur attirance sexuelle ont t classs dans la catgorie des jeunes n’tant pas attirs exclusivement par des personnes du genre oppos, certains d’entre eux pourraient avoir une orientation htrosexuelle ultrieurement36. Dans le cas des personnes attires par des personnes du genre oppos, l’attirance se rvle relativement stable tout au long de l’adolescence et du dbut de l’ge adulte comparativement aux personnes attires par des personnes du mme genre ou des deux genres et aux personnes incertaines de leur attirance, mme si les tudes semblent faire tat de diffrences quant la stabilit de l’orientation sexuelle21,36,37. Il peut par consquent tre pertinent de comparer les personnes qui sont attires seulement par des personnes du genre oppos celles qui dclarent toute autre forme d’attirance, en particulier dans les analyses transversales.

Points forts et limites

Il s’agit de la premire tude dcrivant la rpartition de l’identit de genre et de l’attirance sexuelle chez les jeunes Canadiens de 12 17ans et apportant une contribution importante l’volution de la comprhension de la porte de la diversit sexuelle et de genre au sein de cette population. Ces rsultats font ressortir la ncessit d’accrotre la recherche sur l’efficacit des politiques et des interventions pour rduire au minimum les iniquits en sant fondes sur le genre et l’attirance ou l’orientation sexuelle. Les tudes dont on dispose font tat d’interventions visant rduire la consommation de substances, les facteurs de stress d’ordre social et les proccupations lies la sant mentale38-40, dont une tude d’intervention ciblant les jeunes qui ont une attirance envers des personnes du mme genre et qui ont des ides suicidaires41. Jusqu’ prsent cependant, les recherches ont t limites, particulirement chez les jeunes.

Cette tude comporte plusieurs limites. Malgr la taille importante de l’chantillon, une grande variabilit a t observe dans les pourcentages obtenus chez certains groupes. Il n’a pas t possible de dterminer la rpartition de l’attirance envers certaines identits de genre particulires, notamment chez les jeunes bispirituels.

Le questionnaire ne prcisait pas si l’attirance sexuelle envers les hommes et envers les femmes tait fonde sur le genre ou sur le sexe. Aux fins de notre tude, nous avons suppos que l’attirance tait fonde sur le genre plutt que sur le sexe, ce qui n’est peut-tre pas le cas pour tous les rpondants.

Les identits non cisgenres et les orientations non htrosexuelles sont souvent porteuses de stigmates, qui varient en fonction du contexte socital et culturel24,42. Ces stigmates peuvent entraner un biais de dsirabilit sociale lors de la dclaration, de sorte que les pourcentages de personnes dclarant une identit non cisgenre et une attirance sexuelle non exclusive envers le genre oppos pourraient tre sous‑estims. Ces biais sont susceptibles de s’attnuer au fil du temps, grce la reconnaissance, la visibilit et l’acceptation de la diversit de genre et sexuelle42.

Enfin, cette tude se limitait l’analyse de l’attirance sexuelle en tant que dimension de l’orientation sexuelle. Bien qu’il puisse sembler plus appropri de mesurer la dimension de l’attirance sexuelle chez les jeunes plutt que les dimensions de l’identit sexuelle ou du comportement sexuel, l’attirance sexuelle ne concorde pas toujours avec les autres dimensions et peut entraner des rpercussions diffrentes sur la sant23,24. Idalement, la surveillance devrait englober les trois dimensions afin de surveiller les ingalits, de faciliter les recherches et de cibler les groupes ayant des besoins en sant publique.

Conclusion

Based on self-reported data, 0.2% of Canadian youth aged 12 to 17 years identify as nonbinary and 0.2% as transgender. Among Canadian youth aged 15 to 17 identifying as male, female or nonbinary, 79.0% report attraction exclusive to the opposite gender, whereas 21.0% report attraction not exclusive to the opposite gender. Previous research has shown significant health and social inequities for the latter group and other minorities in this study. Conducting surveillance and research is a necessary step in reducing inequities, and researchers should consider oversampling or other approaches to ensure that reliable estimates can be obtained for nonbinary and transgender youth and youth with same-gender attraction.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

CW, GB, SLW, CS, BJ, MTB, KCR—conceptualization, writing—reviewing & editing. CW, GB—methodology. CW—formal analysis; writing—original draft.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Gilmour H, et al. Sexual orientation and complete mental health. Health Rep. 2019;30((11)):3–10. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x201901100001-eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele LS, Ross LE, Dobinson C, Veldhuizen S, Tinmouth JM, et al. Women’s sexual orientation and health: results from a Canadian population-based survey. Women Health. 2009;49((5)):353–67. doi: 10.1080/03630240903238685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan DJ, Ross LE, Dobinson C, Veldhuizen S, Steele LS, et al. Men’s sexual orientation and health in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2010;101((3)):255–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03404385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffray B, et al. Experiences of violent victimization and unwanted sexual behaviours among gay, lesbian, bisexual and other sexual minority people, and the transgender population, in Canada, 2018. Jaffray B. 2020:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): The Daily: A statistical portrait of Canada’s diverse LGBTQ2+ communities [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210615/dq210615a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Blais M, Duford J, bert M, et al. Health outcomes of sexual-minority youth in Canada: an overview. Adolesc Saude. 2015;12((3)):53–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, Saewyc EM, et al. The mental health of Canadian transgender youth compared with the Canadian population. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60((1)):44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen MF, Merry SN, Robinson EM, et al, et al. Sexual attraction, depression, self-harm, suicidality and help-seeking behaviour in New Zealand secondary school students. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45((5)):376–83. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.559635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk JW, Miller JM, Gilman SE, Lipsky LM, Haynie DL, Simons-Morton BG, et al. Sexual minority status and adolescent eating behaviors, physical activity, and weight status. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55((6)):839–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbey D, Mahfouda S, Ohan J, Lin A, Perry Y, et al. Trajectories of mental health difficulties in young people who are attracted to the same gender: a systematic review. Adolesc Res Rev. 2020:281–93. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Variables - by subject [Internet] Available from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/concepts/definitions/index. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Participate in the consultation on gender and sexual diversity statistical metadata standards [Internet] Available from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/concepts/consult-variables/gender. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Gender of person [Internet] Available from: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DEC&Id;=410445. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Classification of cisgender, transgender and non-binary [Internet] Available from: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?Function=getVD&TVD;=1326715. [Google Scholar]

- Bates N, Chin M, Becker T, et al. National Academies Press. Washington(DC): 2022. Measuring sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578625/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, Bauer GR, Skay CL, et al, et al. Measuring sexual orientation in adolescent health surveys: evaluation of eight school-based surveys. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35((4)):345–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igartua K, Thombs BD, Burgos G, Montoro R, et al. Concordance and discrepancy in sexual identity, attraction, and behavior among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45((6)):602–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Sham WW, Wong WI, et al. Are romantic orientation and sexual orientation different. Curr Psychol. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S, et al. An introduction to the health of two-spirit people: historical, contemporary and emergent issues. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Infobase. Ottawa(ON): Health inequalities data tool [Internet] Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/health-inequalities/data-tool/index. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, Vignoles VL, et al. Identity development among sexual-minority youth. Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_28. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL, et al. Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36((3)):385–94. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Conron K, Patel A, Freedner N, et al. Making sense of sexual orientation measures: findings from a cognitive processing study with adolescents on health survey questions. J LGBT Health Res. 2007;3((1)):55–65. doi: 10.1300/j463v03n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, et al. Research on adolescence sexual orientation: development, health disparities, stigma and resilience. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21((1)):256–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): The Daily: Canada is the first country to provide census data on transgender and non-binary people [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220427/dq220427b-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Stewart D, Poon C, Peled M, Saewyc E, et al. McCreary Centre Society. Vancouver(BC): 2014. From Hastings Street to Haida Gwaii: provincial results of the 2013 BC Adolescent Health Survey. Available from: https://www.saravyc.ubc.ca/2014/04/30/from-hastings-street-to-haida-gwaii-provincial-results-of-the-2013-bc-adolescent-health-survey/ [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (CHSCY) [Internet] Available from: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS;=5233. [Google Scholar]

- Mereish EH, Poteat VP, et al. Let’s get physical: sexual orientation disparities in physical activity, sports involvement, and obesity among a population-based sample of adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2015;105((9)):1842–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perales F, Campbell A, O’Flaherty M, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent time use: how sexual minority youth spend their time. Child Dev. 2020:983–1000. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TC, Lucassen MF, Bullen P, et al, et al. The health and well-being of transgender high school students: results from the New Zealand adolescent health survey (Youth’12) J Adolesc Health. 2014;55((1)):93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SE, O’Brien EK, Coleman B, Tessman GK, Hoffman L, Delahanty J, et al. Sexual and gender minority U.S. amepre. 2019;57((2)):256–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JG, Jabson JM, Bowen DJ, et al. Measuring sexual and gender minority populations in health surveillance. LGBT Health. 2017;4((2)):82–105. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, et al. LGBT Identification in U.S. LGBT Identification in U.S. ticks up to 7.1%. Gallup [Internet] Available from: https://news.gallup.com/poll/389792/lgbt-identification-ticks-up.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Perales F, Campbell A, et al. Early roots of sexual-orientation health disparities: associations between sexual attraction, health and well-being in a national sample of Australian adolescents. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019:954–62. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-211588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharma C, Bauer GR, et al. Understanding sexual orientation and health in Canada: who are we capturing and who are we missing using the Statistics Canada sexual orientation question. Can J Public Health. 2017:e21–e26. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.108.5848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott MQ, Corliss HL, Wypij D, Rosario M, Austin SB, et al. Stability and change in self-reported sexual orientation identity in young people: application of mobility metrics. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40((3)):519–32. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9691-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Norton S, Rahman Q, et al. Childhood gender nonconformity and the stability of self-reported sexual orientation from adolescence to young adulthood in a birth cohort. Dev Psychol. 2021:557–69. doi: 10.1037/dev0001164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobaica S, Alman A, Jackowich S, Kwon P, et al. Empirically based psychological interventions with sexual minority youth: a systematic review. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2018;5((3)):313–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbey D, Morgan H, Lin A, Perry Y, et al. Effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of digital health interventions for LGBTIQ+ young people: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2020:e20158–23. doi: 10.2196/20158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, Wang K, Pachankis JE, et al. What reduces sexual minority stress. Chaudoir SR, Wang K, Pachankis JE. 2017;73((3)):586–617. doi: 10.1111/josi.12233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GM, Diamond GS, Levy S, Closs C, Ladipo T, Siqueland L, et al. Attachment-based family therapy for suicidal lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: a treatment development study and open trial with preliminary findings. Psychotherapy. 2012;49((1): 62-71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026247. Erratum in: Psychotherapy. 2013; 50(4)):62–71. doi: 10.1037/a0026247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerwijk EL, Sevelius JM, et al. Transgender population size in the United States: a meta-regression of population-based probability samples. Am J Public Health. 2017;107((2)):e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]