Abstract

Aims

Tafamidis treatment positively affects left ventricular (LV) structure and function and improves outcomes in patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM). We aimed to investigate the relationship between treatment response and cardiac amyloid burden identified by serial quantitative 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT. We furthermore aimed to identify nuclear imaging biomarkers that could be used to quantify and monitor response to tafamidis therapy.

Methods and results

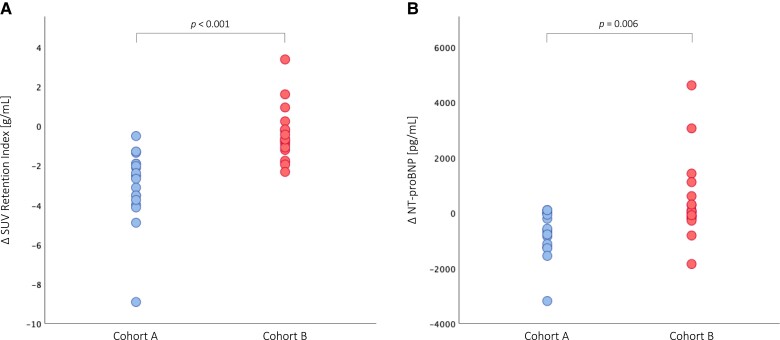

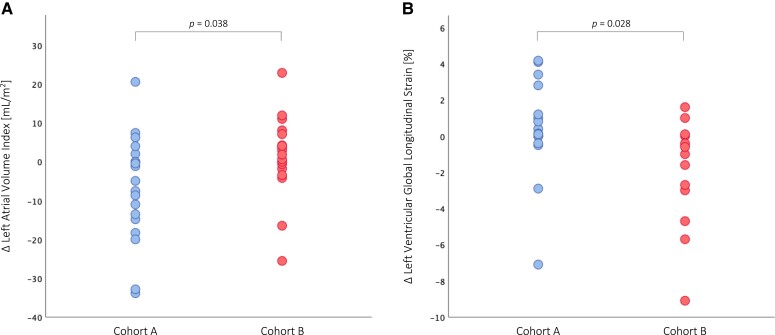

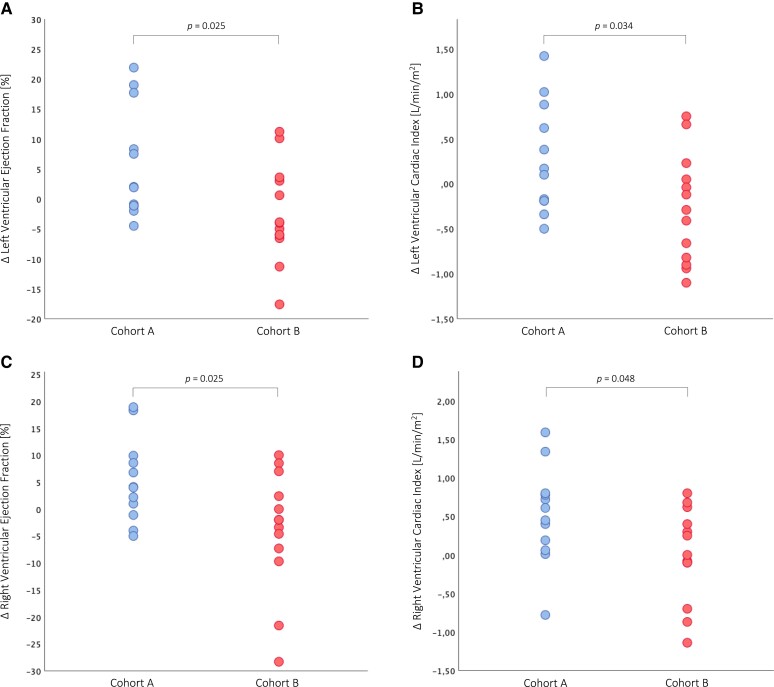

Forty wild-type ATTR-CM patients who underwent 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy and SPECT/CT imaging at baseline and after treatment with tafamidis 61 mg once daily [median, 9.0 months (interquartile range 7.0–10.0)] were divided into two cohorts based on the median (−32.3%) of the longitudinal percent change in standardized uptake value (SUV) retention index. ATTR-CM patients with a reduction greater than or equal to the median (n = 20) had a significant decrease in SUV retention index (P < 0.001) at follow-up, which translated into significant benefits in serum N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide levels (P = 0.006), left atrial volume index (P = 0.038), as well as LV [LV global longitudinal strain: P = 0.028, LV ejection fraction (EF): P = 0.027, LV cardiac index (CI): P = 0.034] and right ventricular (RV) [RVEF: P = 0.025, RVCI: P = 0.048] functions compared with patients with a decrease less than the median (n = 20).

Conclusion

Treatment with tafamidis in ATTR-CM patients results in a significant reduction in SUV retention index, associated with significant benefits for LV and RV function and cardiac biomarkers. Serial quantitative 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging with SUV may be a valid tool to quantify and monitor response to tafamidis treatment in affected patients.

Translational perspective

99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging with determination of SUV retention index as part of a routine annual examination can provide evidence of treatment response in ATTR-CM patients receiving disease-modifying therapy. Further long-term studies with 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging may help to evaluate the relationship between tafamidis-induced reduction in SUV retention index and outcome in patients with ATTR-CM and will demonstrate whether highly disease-specific 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging is more sensitive than routine diagnostic monitoring.

Keywords: SPECT/CT, SUV quantification, tafamidis, transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis, treatment monitoring

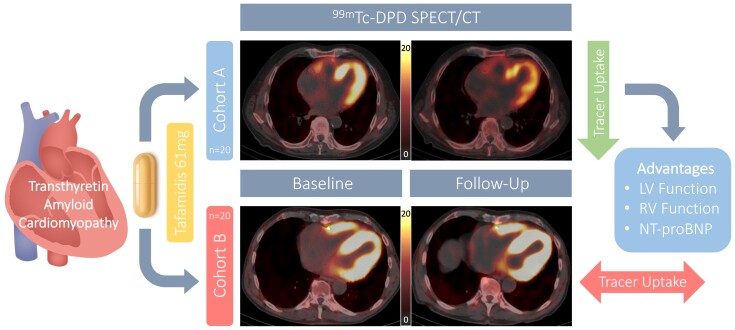

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Response to tafamidis treatment and effects on cardiac function and biomarkers. Serial quantitative 99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid (DPD) single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) imaging with standardized uptake value (SUV) of representative patients with wild-type transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy treated with tafamidis 61 mg once daily. Patients were divided into two cohorts based on the median (−32.3%) of the longitudinal percent change in SUV retention index. Cohort A patients had a longitudinal percent reduction in SUV retention index greater than or equal to the median (upper panels), which was associated with significant benefits for left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) function and serum levels of N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). Cohort B patients had either a percent decrease less than the median or even a percent increase from baseline (lower panels), without significant benefits for LV and RV function and cardiac biomarkers.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Expanding the role of bone-avid tracer cardiac single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography: assessment of treatment response in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy’, by Sharmila Dorbala, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jead108.

Introduction

The potentially life-threatening diagnosis of transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) is pathophysiologically characterized by disintegrated liver-derived transthyretin (TTR) that accumulates as amyloid fibrils in the myocardium, leading to progressive heart failure (HF) with fatal prognosis, especially if left untreated.1,2 Once considered a rare disease, novel diagnostic algorithms have led to an increasing number of patients being diagnosed with ATTR-CM in recent years. In particular, nuclear imaging, such as bone scintigraphy with radiolabelled phosphonates like 99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid (DPD), allows visualization of amyloid deposits by planar imaging and has become the non-invasive gold standard for the diagnosis of ATTR-CM.3 Novel nuclear imaging techniques, such as single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT), provide a 3D visualization of radioactivity in the body and determination of a standardized uptake value (SUV) indicating the concentration of the radiopharmaceutical in each tissue4,5 and may render additional support in understanding the relationship between treatment and response to disease-modifying therapies like tafamidis,6 which positively affects left ventricular (LV) structure and function and improves outcomes in ATTR-CM patients.7,8

Hence, the present study aimed to investigate the relationship between tafamidis treatment and response in ATTR-CM patients using quantitative 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging with SUV to identify nuclear imaging biomarkers that could be used to quantify and monitor response to tafamidis treatment. Therefore, serial 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy and SPECT/CT imaging were performed in ATTR-CM patients prior to and after treatment with tafamidis, divided into two cohorts based on longitudinal changes in SUV parameters, and compared for clinical and imaging outcomes.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted as part of a prospective HF registry at the Department of Internal Medicine II, Division of Cardiology at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, which includes a dedicated amyloidosis outpatient clinic. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (#796/2010) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to registry inclusion for baseline and follow-up assessments.

Study design

Consecutive registry patients diagnosed with ATTR-CM between June 2019 and April 2021 were screened for study eligibility; eligible study participants underwent baseline and follow-up assessments at our dedicated amyloidosis outpatient clinic as part of a prospective investigative imaging study. ATTR-CM patients were excluded if the following criteria were met: (i) inability to undergo 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy and SPECT/CT imaging at baseline and follow-up; (ii) presence of mutation in the TTR gene (ATTR variant); this patient population is very heterogeneous and has an individual, mutation-dependent and highly variable disease course compared with wild-type ATTR; and (iii) treatment with tafamidis prior to baseline assessment.

Diagnosis of ATTR-CM

In accordance with the non-invasive diagnostic algorithm published in 2016 by Gillmore et al.,3 bone scintigraphy was performed in patients with clinical suspicion of cardiac amyloidosis. The diagnosis of ATTR-CM was confirmed when patients had significant myocardial tracer uptake (Perugini grade ≥ 2) on bone scintigraphy and no paraprotein or monoclonal protein was detected by serum and urine immunofixation and serum free light chain assay.3,9 Patients with ATTR-CM were offered sequencing of the TTR gene, which was accepted by all patients.

Tafamidis treatment

Tafamidis 61 mg (a single capsule is bioequivalent to tafamidis meglumine 80 mg10) was administered once daily (QD), either under Pfizer’s early access program following publication of the ATTR-ACT trial8 or after approval by health insurance reimbursement.

Clinical and laboratory assessment

Clinical status was defined by New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class. Submaximal functional capacity was assessed by the 6 min walk test according to the American Thoracic Society guidelines.11 Laboratory testing included determination of cardiac biomarkers [N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP)] and troponin T, as well as haemoglobin and serum creatinine levels.

99mTc-DPD scintigraphy and SPECT/CT

Nuclear imaging was performed at the Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image-guided Therapy, Division of Nuclear Medicine at the Medical University of Vienna. Planar whole-body images were obtained 2.5 h and SPECT/CT imaging of the thorax 3.0 h after intravenous injection of 99mTc radiolabelled DPD (mean activity: 725.4 MBq ±25.7) using a hybrid SPECT/CT system (Symbia Intevo, Siemens Medical Solutions AG, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a low-energy, high-resolution collimator [mean dose length product (DLP): 86.3 mGy*cm ±30.7]. There were no differences between baseline and follow-up in the timing of 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy and SPECT/CT imaging after tracer application, 99mTc-DPD activity (725.4 MBq ± 25.7 vs. 720.8 MBq ± 28.7, P = 0.452), and DLP (86.3 mGy*cm ± 30.7 vs. 91.9 mGy*cm ± 40.1, P = 0.407). Images were acquired in 180° configuration, 64 views, 20 s per view, 256 × 256 matrix, and an energy window of 15% around the 99mTc photopeak of 141 keV. Subsequent to the SPECT acquisition, a low-dose CT scan was acquired for attenuation correction (130 kV, 35 mAs, 256 × 256 matrix, step-and-shoot acquisition with body contour). Image acquisition and reconstruction were performed using xSPECT/CT QUANT (xQUANT) technology (eight iterations, four subsets, 3.0 mm smoothing filter, and a 20 mm Gaussian filter), which uses a 3% National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) traceable precision source for standardization of uptake values across different cameras, dose calibrators, and facilities.12,13

Volume of interest

For the automatic contouring of the 3D volume of interest (VOI) of the myocardium, a threshold for maximal activity was developed in phantom experiments at which 39% of maximal activity resulted in a VOI of ∼155 mL, which was in good agreement with the cardiac insert volume of 155 mL and yielded a clear linear relationship between the applied and measured activity concentrations, as confirmed by linear regression analysis (r = 0.9998, P = 0.010).6

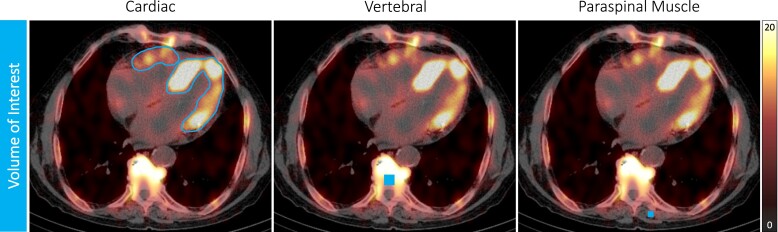

Standardized uptake value

Myocardial uptake on SPECT/CT images was determined using dedicated software (Hermes Hybrid 3D software, Hermes Medical Solutions, Stockholm, Sweden). Three-dimensional myocardial VOIs were automatically generated using a threshold-based method, as previously described, allowing clear separation of myocardial uptake from blood pool activity (Figure 1). The myocardial VOIs were reviewed by the operator and corrected if sternal or rib uptake was evident. From these VOIs, an SUV was determined, indicating the concentration of the radiopharmaceutical in the respective tissue, with SUV peak representing the highest average SUV within a 1 cm3 volume. Bone uptake (SUV peak vertebral) was calculated by placing a cubic 2.92 mL VOI in an intact vertebral body of a thoracic spine (identical at baseline and follow-up) in an area without degenerative changes to minimize distortion from high degenerative tracer accumulation. For determination of SUV peak paraspinal muscle, a cubic 1.19 mL VOI was placed in the left paraspinal muscle, attempting to match the same position at baseline and follow-up. Confounders caused by competing tracer uptake between respective tissues can be overcome by a composite SUV retention index that balances uptake between the heart, bone, and soft tissue compartments and thus may provide a means of monitoring response to therapy.14 It was calculated according to the following formula:

Figure 1.

SPECT/CT and volume of interest. SPECT/CT 99mTc-DPD acquisition of a representative treatment-naïve patient with wild-type ATTR-CM showing the VOI for each tissue (VOI cardiac: automatically generated using a threshold-based method, VOI vertebral: 2.92 mL, VOI paraspinal muscle: 1.19 mL) placed to quantify the SUV.

Nuclear imaging analysis

Planar whole-body images were evaluated independently by two experienced physicians and visually graded according to Perugini et al.15 as previously described. Discrepancies in grading were resolved by consensus. SPECT/CT acquisitions of the thorax were analysed with dedicated software (Hermes Hybrid 3D software, Hermes Medical Solutions, Stockholm, Sweden) and evaluated by two independent, experienced observers blinded to patients’ baseline values. Dedicated software and SUV calculation methods were not changed between baseline and follow-up.

Transthoracic echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed by certified and experienced operators using modern equipment (GE Vivid E95, Vivid E9, and Vivid 7, GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI, USA) according to current recommendations.16,17 Image analyses were performed after image acquisition on a modern offline clinical workstation equipped with dedicated software (EchoPAC, GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI, USA) by certified cardiologists who were blinded to patients’ baseline values. Dedicated software and calculation methods were not changed during measurements over time.

CMR imaging

Patients without contraindications [e.g. chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 4 or 5 with an estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, or implanted cardiac device] underwent cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging on a 1.5 T scanner (MAGNETOM Avanto Fit, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) according to standard protocols,18,19,20 which included late gadolinium enhancement (0.1 mmoL/kg gadobutrol, Gadovist, Bayer Vital GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany) and T1 mapping. All CMR imaging parameters were analysed with dedicated software (cmr42, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., Calgary, Alberta, Canada) by certified radiologists and cardiologists who were blinded to patients’ baseline values. Dedicated software, T1 mapping, and extracellular volume (ECV) calculation methods were not changed between baseline and follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed either as mean and standard deviation (SD) or as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), Kruskal–Wallis test, and χ2 test were used to compare between multiple cohorts, while the paired t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, and χ2 test were used to compare between two cohorts. We considered a two-sided significance level alpha = 0.05 for statistical testing. P-values are to be interpreted in a descriptive way throughout. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA).

Results

Study participants

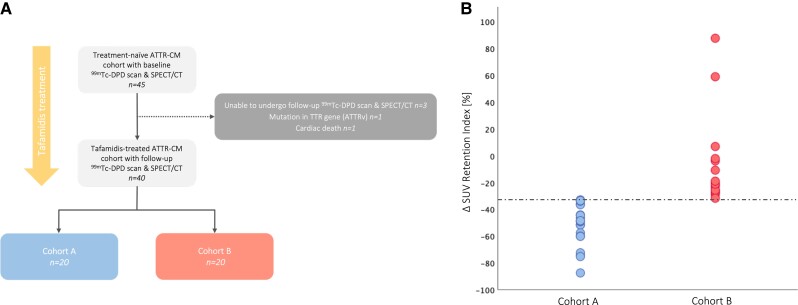

A total of 45 treatment-naïve ATTR-CM patients were evaluated for study eligibility, of whom 40 wild-type ATTR-CM patients who underwent 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy and SPECT/CT imaging prior to and after treatment with tafamidis 61 mg QD [median, 9.0 months (IQR: 7.0–10.0)] were deemed eligible; detailed reasons for study exclusion or discontinuation are shown in Figure 2A. All study participants (n = 40) underwent TTE at baseline and follow-up [median, 8.0 months (IQR: 7.0–11.0)]; in addition, 25 ATTR-CM patients without contraindications were subjected to baseline and follow-up CMR imaging [median, 9.0 months (IQR: 7.0–10.0)]. ATTR-CM patients were divided into two cohorts based on the median (−32.3%) of the longitudinal percent change in SUV retention index. Twenty ATTR-CM patients treated with tafamidis had a longitudinal percent decrease in SUV retention index greater than or equal to the median and were assigned to Cohort A, whereas the remaining 20 patients treated with tafamidis had either a percent decrease less than the median or even a percent increase from baseline and were assigned to Cohort B (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Patient flowchart. A total of 45 treatment-naïve patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) who underwent 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy and single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) imaging were screened for the study. Reasons for study exclusion or discontinuation are depicted. (B) Classification based on percentage change in SUV retention index from baseline. Tafamidis-treated ATTR-CM patients were divided into two cohorts (Cohort A and Cohort B) based on the median percent change in SUV retention index from baseline (−32.3%, dashed line).

Baseline characteristics

Detailed baseline characteristics for the entire study population and for individual cohorts are depicted in Table 1. On average, ATTR-CM patients were 78.6 years (SD: 6.6) old and predominately male (82.5%). Median serum NT-proBNP levels were markedly elevated with 2181 pg/mL (IQR: 1248–3164) and comparable between the groups [2341 pg/mL (IQR: 1296–3164) vs. 1877 pg/mL (IQR: 920–3109), P = 0.800]. Nuclear imaging with 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy of the total ATTR-CM cohort classified 47.5% patients with Perugini grade 2% and 52.5% with grade 3, without significant between-group differences (Cohort A, grade 2: 60.0%, grade 3: 40.0% vs. Cohort B, grade 2: 35.0%, grade 3: 65.0%; P = 0.119). Quantitative 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging at baseline revealed a mean cardiac SUV peak of 14.64 g/mL (SD: 4.54) and a mean SUV retention index of 4.96 g/mL (SD: 2.46), which did not differ between patients in distinct cohorts (SUV peak cardiac: 14.82 g/mL ±3.80 vs. 14.45 g/mL ±5.28, P = 0.797; SUV retention index: 5.58 g/mL ±2.57 vs. 4.35 g/mL ±2.25, P = 0.117). Echocardiographic imaging of ATTR-CM patients showed LA enlargement [left atrial volume index (LAVI): 41.2 mL/m2 ± 15.1], which was comparable between groups (43.0 mL/m2 ± 16.2 vs. 39.6 mL/m2 ± 14.1, P = 0.488). Analysis of longitudinal function by 2D speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) revealed impairments in LV global longitudinal strain (LV-GLS: −12.88% ± 3.14) and right ventricular (RV) longitudinal strain (RV-LS: −15.39% ± 5.37) that did not vary between cohorts (LV-GLS: −12.02% ± 3.21 vs. −13.91% ± 2.81, P = 0.095; RV-LS: −14.55% ± 4.81 vs. −16.38% ± 6.04, P = 0.418). ATTR-CM patients who underwent CMR (n = 25, Supplementary data online, Table S1) had mildly reduced LV function [LV ejection fraction (EF): 45.5% ± 10.2, LV cardiac index (CI): 2.68 L/min/m2 ± 0.65] and RV function (RVEF: 43.7% ± 10.2, RVCI: 2.35 L/min/m2 ± 0.51), which did not differ between cohorts (LVEF: 42.3% ± 10.4 vs. 48.5% ± 9.4, P = 0.133; LVCI: 2.63 L/min/m2 ± 0.69 vs. 2.75 L/min/m2 ± 0.38, P = 0.596; RVEF: 40.9% ± 9.2 vs. 46.2% ± 10.6, P = 0.193; RVCI: 2.29 L/min/m2 ± 0.64 vs. 2.41 L/min/m2 ± 0.36, P = 0.569) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 40) | Cohort A (n = 20) | Cohort B (n = 20) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical parameters | ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 78.6 (6.6) | 80.5 (6.0) | 76.6 (6.7) | 0.060 |

| Sex male, n (%) | 33 (82.5) | 17 (85.0) | 16 (80.0) | 0.687 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 25.8 (3.7) | 26.5 (3.4) | 25.1 (3.9) | 0.214 |

| NYHA functional class ≥III, n (%) | 22 (55.0) | 14 (70.0) | 8 (40.0) | 0.059 |

| 6-min walk distance (m), mean (SD) | 386.6 (130.8) | 351.8 (132.5) | 417.5 (124.9) | 0.147 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 20 (50.0) | 10 (50.0) | 10 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| Arterial hypertension | 23 (57.5) | 11 (55.0) | 12 (60.0) | 0.757 |

| Coronary artery disease | 13 (32.5) | 8 (40.0) | 5 (25.0) | 0.324 |

| Pacemaker or ICD | 10 (25.0) | 6 (30.0) | 4 (20.0) | 0.595 |

| Polyneuropathy | 24 (60.0) | 12 (60.0) | 12 (60.0) | 1.000 |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | 19 (47.5) | 9 (45.0) | 10 (50.0) | 0.759 |

| Concomitant medication, n (%) | ||||

| Anticoagulant | 23 (57.5) | 12 (60.0) | 11 (55.0) | 0.757 |

| Beta-blocker | 15 (37.5) | 9 (45.0) | 6 (30.0) | 0.340 |

| ACE inhibitor | 13 (32.5) | 7 (35.0) | 6 (30.0) | 0.744 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 8 (20.0) | 3 (15.0) | 5 (25.0) | 0.442 |

| Diuretic agent | 33 (82.5) | 16 (80.0) | 17 (85.0) | 0.687 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 21 (52.5) | 9 (45.0) | 12 (60.0) | 0.355 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), mean (SD) | 13.5 (1.4) | 13.1 (1.8) | 13.8 (0.8) | 0.106 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 1.35 (0.80) | 1.52 (1.07) | 1.19 (0.30) | 0.192 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), mean (SD) | 60.4 (21.6) | 58.9 (26.0) | 61.8 (16.7) | 0.678 |

| Troponin T (ng/L), mean (SD) | 60.3 (53.6) | 66.7 (72.4) | 53.9 (23.7) | 0.455 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 2181 (1248–3164) | 2341 (1296–3164) | 1877 (920–3109) | 0.800 |

| Nuclear imaging parameters | ||||

| Perugini grade 2, n (%) | 19 (47.5) | 12 (60.0) | 7 (35.0) | 0.119 |

| Perugini grade 3, n (%) | 21 (52.5) | 8 (40.0) | 13 (65.0) | 0.119 |

| SUV peak cardiac (g/mL), mean (SD) | 14.64 (4.54) | 14.82 (3.80) | 14.45 (5.28) | 0.797 |

| SUV retention index (g/mL), mean (SD) | 4.96 (2.46) | 5.58 (2.57) | 4.35 (2.25) | 0.117 |

| 99mTc-DPD activity (MBq), mean (SD) | 725.4 (25.7) | 729.4 (24.8) | 721.4 (26.6) | 0.328 |

| DLP (mGy*cm), mean (SD) | 86.3 (30.7) | 86.9 (26.9) | 85.7 (34.9) | 0.909 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||||

| Intraventricular septum (mm), mean (SD) | 19.2 (3.7) | 19.9 (4.3) | 18.5 (2.9) | 0.234 |

| LV end-diastolic diameter (mm), mean (SD) | 43.0 (6.8) | 43.9 (6.4) | 42.2 (7.2) | 0.430 |

| LV ejection fraction (%), mean (SD) | 49.1 (11.1) | 47.3 (7.3) | 50.6 (9.0) | 0.231 |

| LV global longitudinal strain (−%), mean (SD) | 12.88 (3.14) | 12.02 (3.21) | 13.91 (2.81) | 0.095 |

| LA length (mm), mean (SD) | 61.2 (9.2) | 63.0 (11.1) | 59.4 (6.6) | 0.231 |

| LA volume index (mL/m2), mean (SD) | 41.2 (15.1) | 43.0 (16.2) | 39.6 (14.1) | 0.488 |

| LA reservoir strain (%), mean (SD) | 9.15 (5.02) | 8.18 (6.08) | 9.97 (4.00) | 0.398 |

| RV end-diastolic diameter (mm), mean (SD) | 33.5 (5.4) | 35.8 (5.3) | 31.4 (4.8) | 0.010 |

| RV longitudinal strain (−%), mean (SD) | 15.39 (5.37) | 14.55 (4.81) | 16.38 (6.04) | 0.418 |

| RA length (mm), mean (SD) | 59.6 (8.9) | 59.7 (10.6) | 59.6 (7.4) | 0.949 |

| TR velocity (m/s), mean (SD) | 2.99 (0.44) | 2.88 (0.41) | 3.09 (0.46) | 0.188 |

| CMR imaging parameters | n = 25 | n = 12 | n = 13 | |

| Interventricular septum (mm), mean (SD) | 17.5 (3.5) | 18.0 (3.1) | 17.0 (4.0) | 0.499 |

| LV mass index (g/m2), mean (SD) | 92.8 (23.2) | 97.5 (23.2) | 87.6 (23.0) | 0.297 |

| LV ejection fraction (%), mean (SD) | 45.5 (10.2) | 42.3 (10.4) | 48.5 (9.4) | 0.133 |

| LV cardiac index (L/min/m2), mean (SD) | 2.68 (0.65) | 2.63 (0.69) | 2.75 (0.38) | 0.596 |

| LA area index (cm2/m2), mean (SD) | 15.7 (2.7) | 16.4 (3.0) | 15.1 (2.3) | 0.239 |

| RV ejection fraction (%), mean (SD) | 43.7 (10.2) | 40.9 (9.2) | 46.2 (10.6) | 0.193 |

| RV cardiac index (L/min/m2), mean (SD) | 2.35 (0.51) | 2.29 (0.64) | 2.41 (0.36) | 0.569 |

| RA area index (cm2/m2), mean (SD) | 14.9 (4.1) | 16.2 (4.7) | 13.8 (3.2) | 0.155 |

| ECV (%), mean (SD) | 50.2 (14.3) | 53.4 (10.2) | 47.0 (17.3) | 0.286 |

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation (SD), or median and interquartile range (IQR), or total numbers (n) and percent (%). Bold indicates P < 0.05.

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance, DLP, dose length product; ECV, extracellular volume; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LA, left atrium, LV, left ventricle; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; SUV, standardized uptake value; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; 99mTc-DPD, 99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid.

Longitudinal changes in imaging parameters—within-cohort comparison

Detailed follow-up characteristics for the overall cohort and individual cohorts are shown in Table 2. 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy and SPECT/CT follow-up were performed after a median of 9.0 months (IQR: 7.0–10.0). Using serial quantitative 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging, we found a significant reduction in cardiac SUV peak (baseline: 14.64 g/mL vs. follow-up: 11.42 g/mL, P < 0.001, Figure 3) in the overall ATTR-CM cohort under tafamidis treatment, which is also evident when considering the individual cohorts (Cohort A: 14.82 g/mL vs. 10.77 g/mL, P < 0.001; Cohort B: 14.45 g/mL vs. 12.06 g/mL, P = 0.003). Adjustment with the SUV retention index revealed a significant decrease in the overall cohort (4.96 g/mL vs. 3.27 g/mL, P < 0.001) and Cohort A (5.58 g/mL vs. 2.66 g/mL, P < 0.001) at follow-up, while there was no improvement in Cohort B (4.35 g/mL vs. 3.87 g/mL, P = 0.116). Echocardiographically, we observed a significant decrease in LAVI (43.0 mL/m2 vs. 36.3 mL/m2, P = 0.046) in patients in Cohort A, but evidence of increase in LAVI (39.6 mL/m2 vs. 41.1 mL/m2, P = 0.507) in patients in Cohort B. Using 2D-STE, we found evidence of stabilization of LV-GLS (−12.02% vs. −12.44%, P = 0.520) and RV-LS (−14.55% vs. −13.85%, P = 0.580) in Cohort A, but significant impairments in LV (−13.91% vs. −12.01%, P = 0.030) and RV (−16.38% vs. −14.56%, P = 0.030) longitudinal functions in Cohort B. Analysis of cardiac function by CMR showed significant improvements in LV (LVEF: 42.3% vs. 48.0%, P = 0.047) and RV (RVEF: 40.9% vs. 46.2%, P = 0.036; RVCI: 2.29 L/min/m2 vs. 2.80 L/min/m2, P = 0.016) functions in ATTR-CM patients in Cohort A.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline and follow-up characteristics

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 40) | Cohort A (n = 20) | Cohort B (n = 20) | Δ Cohort A | Δ Cohort B | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | P-value | Baseline | Follow-up | P-value | Baseline | Follow-up | P-value | P-value | |||

| Clinical parameters | ||||||||||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 25.8 (3.7) | 25.5 (3.5) | 0.011 | 26.5 (3.4) | 26.1 (3.4) | 0.029 | 25.1 (3.9) | 24.8 (3.6) | 0.166 | −0.4 (0.7) | −0.3 (0.8) | 0.626 |

| NYHA functional class ≥III, n (%) | 22 (55.0) | 17 (42.5) | 0.030 | 14 (70.0) | 9 (45.0) | 0.021 | 8 (40.0) | 8 (40.0) | 1.000 | −5 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.049 |

| 6-min walk distance (m), mean (SD) | 386.6 (130.8) | 380.2 (145.3) | 0.631 | 351.8 (132.5) | 364.6 (158.6) | 0.556 | 417.5 (124.9) | 394.1 (135.4) | 0.148 | 12.8 (85.2) | −23.4 (65.5) | 0.172 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||||||||||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), mean (SD) | 13.5 (1.4) | 13.4 (1.4) | 0.414 | 13.1 (1.8) | 13.1 (1.8) | 1.000 | 13.8 (0.8) | 13.6 (0.8) | 0.224 | 0.0 (0.8) | −0.2 (0.7) | 0.416 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 1.35 (0.80) | 1.43 (0.93) | 0.298 | 1.52 (1.07) | 1.63 (1.27) | 0.442 | 1.19 (0.30) | 1.23 (0.28) | 0.311 | 0.11 (0.63) | 0.04 (0.18) | 0.643 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2), mean (SD) | 60.4 (21.6) | 57.0 (19.8) | 0.052 | 58.9 (26.0) | 54.9 (24.3) | 0.181 | 61.8 (16.7) | 59.0 (14.4) | 0.136 | −4.0 (12.8) | −2.8 (8.0) | 0.730 |

| Troponin T (ng/L), mean (SD) | 60.3 (53.6) | 63.9 (53.8) | 0.094 | 66.7 (72.4) | 69.7 (71.1) | 0.251 | 53.9 (23.7) | 58.2 (28.7) | 0.231 | 3.0 (11.1) | 4.3 (15.5) | 0.754 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 2181 (1248–3164) | 1675 (1212–2682) | 0.068 | 2341 (1296–3164) | 1492 (1263–2148) | 0.002 | 1877 (920–3109) | 1943 (1202–3010) | 0.550 | −849 | 66 | 0.006 |

| Nuclear imaging parameters | ||||||||||||

| Perugini grade 3, n (%) | 21 (52.5) | 18 (45.0) | 0.262 | 8 (40.0) | 5 (25.0) | 0.186 | 13 (65.0) | 13 (65.0) | 1.000 | −3 (15.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.657 |

| SUV peak cardiac (g/mL), mean (SD) | 14.64 (4.54) | 11.42 (3.94) | <0.001 | 14.82 (3.80) | 10.77 (3.98) | <0.001 | 14.45 (5.28) | 12.06 (3.90) | 0.003 | −4.05 (2.43) | −2.39 (3.09) | 0.066 |

| SUV retention index (g/mL), mean (SD) | 4.96 (2.46) | 3.27 (1.77) | <0.001 | 5.58 (2.57) | 2.66 (1.42) | <0.001 | 4.35 (2.25) | 3.87 (1.92) | 0.116 | −2.92 (1.80) | −0.48 (1.31) | <0.001 |

| 99mTc-DPD activity (MBq), mean (SD) | 725.4 (25.7) | 720.8 (28.7) | 0.452 | 729.4 (24.8) | 723.9 (38.6) | 0.615 | 721.4 (26.6) | 717.7 (13.6) | 0.531 | −5.5 (49.0) | −3.7 (25.9) | 0.879 |

| DLP (mGy*cm), mean (SD) | 86.3 (30.7) | 91.9 (40.1) | 0.407 | 86.9 (26.9) | 98.2 (37.5) | 0.190 | 85.7 (34.9) | 85.2 (42.7) | 0.959 | 11.3 (37.4) | −0.5 (45.7) | 0.377 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||||||||||||

| Intraventricular septum (mm), mean (SD) | 19.2 (3.7) | 19.9 (3.8) | 0.010 | 19.9 (4.3) | 20.5 (4.4) | 0.077 | 18.5 (2.9) | 19.4 (2.9) | 0.061 | 0.6 (1.3) | 0.9 (2.1) | 0.476 |

| LV end-diastolic diameter (mm), mean (SD) | 43.0 (6.8) | 41.4 (8.0) | 0.116 | 43.9 (6.4) | 42.2 (8.1) | 0.246 | 42.2 (7.2) | 40.7 (8.1) | 0.307 | −1.7 (6.3) | −1.5 (10.0) | 0.908 |

| LV ejection fraction (%), mean (SD) | 49.1 (11.1) | 48.9 (8.2) | 0.923 | 47.3 (7.3) | 49.8 (12.6) | 0.306 | 50.6 (9.0) | 48.3 (9.6) | 0.153 | 2.5 (10.0) | −2.3 (6.5) | 0.101 |

| LV global longitudinal strain (−%), mean (SD) | 12.88 (3.14) | 12.25 (3.94) | 0.251 | 12.02 (3.21) | 12.44 (3.91) | 0.520 | 13.91 (2.81) | 12.01 (4.12) | 0.030 | 0.42 (2.66) | −1.90 (2.92) | 0.028 |

| LA length (mm), mean (SD) | 61.2 (9.2) | 60.5 (7.4) | 0.651 | 63.0 (11.1) | 59.1 (7.3) | 0.072 | 59.4 (6.6) | 61.9 (7.3) | 0.134 | −3.9 (8.9) | 2.5 (7.1) | 0.018 |

| LA volume index (mL/m2), mean (SD) | 41.2 (15.1) | 38.8 (11.8) | 0.220 | 43.0 (16.2) | 36.3 (11.3) | 0.046 | 39.6 (14.1) | 41.1 (12.1) | 0.507 | −6.7 (13.6) | 1.5 (10.0) | 0.038 |

| LA reservoir strain (%), mean (SD) | 9.15 (5.02) | 8.66 (4.55) | 0.438 | 8.18 (6.08) | 8.47 (5.43) | 0.461 | 9.97 (4.00) | 8.82 (3.88) | 0.313 | 0.29 (1.23) | −1.15 (3.92) | 0.233 |

| RV end-diastolic diameter (mm), mean (SD) | 33.5 (5.4) | 34.5 (4.3) | 0.198 | 35.8 (5.3) | 35.7 (4.2) | 0.959 | 31.4 (4.8) | 33.4 (4.2) | 0.089 | −0.1 (4.4) | 2.0 (5.0) | 0.182 |

| RV longitudinal strain (−%), mean (SD) | 15.39 (5.37) | 14.18 (5.27) | 0.113 | 14.55 (4.81) | 13.85 (4.99) | 0.580 | 16.38 (6.04) | 14.56 (5.80) | 0.030 | −0.70 (4.42) | −1.82 (2.38) | 0.459 |

| RA length (mm), mean (SD) | 59.6 (8.9) | 59.7 (7.3) | 0.939 | 59.7 (10.6) | 58.5 (7.2) | 0.506 | 59.6 (7.4) | 60.9 (7.4) | 0.091 | −1.2 (8.1) | 1.3 (3.4) | 0.206 |

| TR velocity (m/s), mean (SD) | 2.99 (0.44) | 3.01 (0.39) | 0.684 | 2.88 (0.41) | 2.89 (0.36) | 0.902 | 3.09 (0.46) | 3.12 (0.40) | 0.661 | 0.01 (0.34) | 0.03 (0.33) | 0.830 |

| CMR imaging parameters | n = 25 | n = 12 | n = 13 | |||||||||

| Intraventricular septum (mm), mean (SD) | 17.5 (3.5) | 18.1 (3.2) | 0.162 | 18.0 (3.1) | 18.1 (2.9) | 0.767 | 17.0 (4.0) | 18.0 (3.6) | 0.103 | 0.1 (1.8) | 1.0 (1.8) | 0.296 |

| LV mass index (g/m2), mean (SD) | 92.8 (23.2) | 94.5 (23.5) | 0.620 | 97.5 (23.2) | 96.4 (2.0.5) | 0.858 | 87.6 (23.0) | 92.5 (27.1) | 0.169 | −1.1 (21.7) | 4.9 (11.4) | 0.405 |

| LV ejection fraction (%), mean (SD) | 45.5 (10.2) | 47.0 (8.2) | 0.443 | 42.3 (10.4) | 48.0 (8.0) | 0.047 | 48.5 (9.4) | 46.0 (8.6) | 0.295 | 5.7 (9.2) | −2.5 (8.1) | 0.027 |

| LV cardiac index (L/min/m2), mean (SD) | 2.68 (0.65) | 2.69 (0.55) | 0.906 | 2.63 (0.69) | 2.89 (0.62) | 0.154 | 2.75 (0.38) | 2.47 (0.64) | 0.124 | 0.26 (0.60) | −0.28 (0.60) | 0.034 |

| LA area index (cm2/m2), mean (SD) | 15.7 (2.7) | 16.1 (3.0) | 0.369 | 16.4 (3.0) | 16.8 (2.4) | 0.168 | 15.1 (2.3) | 15.4 (3.4) | 0.686 | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.3 (2.9) | 0.876 |

| RV ejection fraction (%), mean (SD) | 43.7 (10.2) | 44.2 (11.1) | 0.812 | 40.9 (9.2) | 46.2 (12.0) | 0.036 | 46.2 (10.6) | 42.3 (10.3) | 0.227 | 5.3 (7.7) | −3.9 (11.1) | 0.025 |

| RV cardiac index (L/min/m2), mean (SD) | 2.35 (0.51) | 2.60 (0.57) | 0.069 | 2.29 (0.64) | 2.80 (0.56) | 0.016 | 2.41 (0.36) | 2.42 (0.53) | 0.978 | 0.51 (0.63) | 0.01 (0.60) | 0.048 |

| RA area index (cm2/m2), mean (SD) | 14.9 (4.1) | 15.4 (4.4) | 0.315 | 16.2 (4.7) | 16.8 (4.9) | 0.285 | 13.8 (3.2) | 14.2 (3.6) | 0.611 | 0.6 (1.9) | 0.4 (3.2) | 0.892 |

| ECV (%), mean (SD) | 50.2 (14.3) | 52.8 (16.6) | 0.169 | 53.4 (10.2) | 54.5 (10.7) | 0.720 | 47.0 (17.3) | 51.2 (21.4) | 0.103 | 1.1 (10.0) | 4.2 (8.2) | 0.408 |

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation (SD), or median and interquartile range (IQR), or total numbers (n) and percent (%). Bold indicates P < 0.05. Abbreviations as in Table 1.

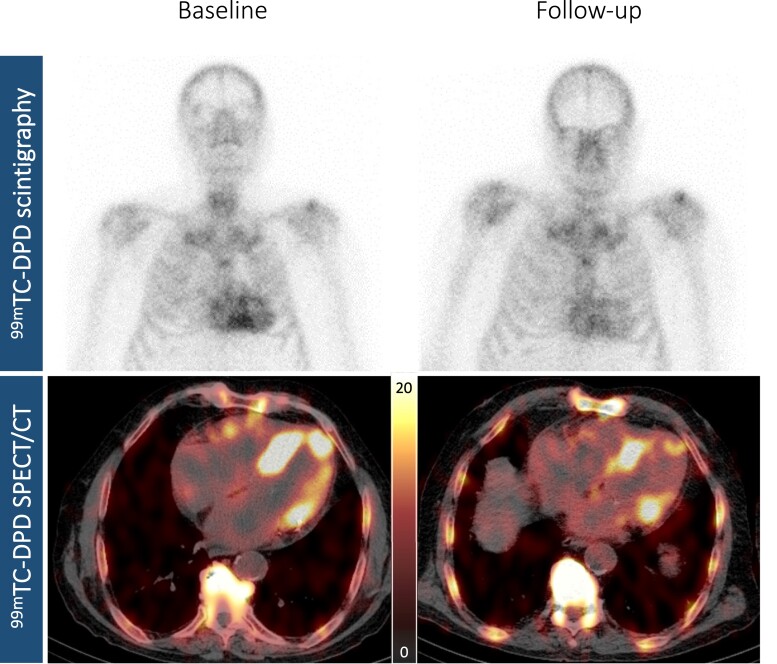

Figure 3.

Visualization of response to tafamidis treatment by nuclear imaging. Planar whole-body 99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid (DPD) image (upper panels) and axial 99mTc-DPD single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) imaging (lower panels) of a representative tafamidis treatment-responsive patient with wild-type ATTR-CM at baseline (left panels, Perugini grade 3, SUV peak cardiac: 12.40 g/mL) and at follow-up (right panels, Perugini grade 2, SUV peak cardiac: 8.56 g/mL).

Longitudinal changes in imaging and clinical parameters—between-cohort comparison

ATTR-CM patients in Cohort A showed a statistically significant decrease in SUV retention index (P < 0.001, Figure 4A) at the end of the observation period, which translated into significant benefits in serum NT-proBNP levels (P = 0.006, Figure 4B), LAVI (P = 0.038, Figure 5A), as well as LV function (LV-GLS: P = 0.028, Figure 5B; LVEF: P = 0.027, Figure 6A; LVCI: P = 0.034, Figure 6B) and RV function (RVEF: P = 0.025, Figure 6C; RVCI: P = 0.048, Figure 6D) compared with patients in Cohort B.

Figure 4.

Longitudinal changes in nuclear imaging and clinical parameters. (A) Change in standardized uptake value (SUV) retention index. (B) Change in serum N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels.

Figure 5.

Longitudinal changes in echocardiographic parameters. (A) Change in left atrial volume index. (B) Change in left ventricular global longitudinal strain.

Figure 6.

Longitudinal changes in cardiac magnetic resonance imaging parameters. (A) Change in left ventricular ejection fraction. (B) Change in left ventricular cardiac index. (C) Change in right ventricular ejection fraction. (D) Change in right ventricular cardiac index.

Discussion

Treatment with tafamidis positively affects LV structure and function and improves outcomes in ATTR-CM patients.7,8 Novel nuclear imaging techniques such as quantitative SPECT/CT imaging may contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between tafamidis treatment and response and may therefore be suitable for monitoring disease-specific therapies.6 Using serial quantitative 99mTC-DPD SPECT/CT imaging with SUV, we were able to demonstrate that (i) treatment with tafamidis 61 mg QD in ATTR-CM patients resulted in a significant decrease in cardiac SUV peak and SUV retention index from baseline; (ii) ATTR-CM patients in whom the percent decrease in SUV retention index was greater than or equal to the median had significant benefits in serum NT-proBNP levels, LAVI, as well as LV and RV function; (iii) serial quantitative 99mTC-DPD-SPECT/CT imaging with SUV may be a valid tool for quantifying and monitoring disease-specific therapy in affected patients.

In the present study, ATTR-CM patients (n = 40) treated with tafamidis 61 mg QD for a median of 9.0 (IQR 7.0–10.0) months showed a significant decrease in cardiac SUV peak (P < 0.001) and SUV retention index (P < 0.001) compared with baseline, which is consistent with previous findings.21,22 Moreover, ATTR-CM patients in whom the percent decrease in SUV retention index was greater than or equal to the median (Cohort A, n = 20) had a significant reduction in SUV retention index (P < 0.001) at the end of the observation period, while patients in whom the percent decrease was less than the median (Cohort B, n = 20) showed no significant improvement at follow-up (P = 0.116), resulting in significant differences in cohort comparison (P < 0.001, Figure 4A).

When comparing the two cohorts on a clinical level, we observed a significant improvement in serum NT-proBNP levels in patients in Cohort A (P = 0.002) as opposed to Cohort B (P = 0.550; cohort comparison: P = 0.006, Figure 4B). These findings suggest that the reduction in SUV retention index induced by tafamidis is associated with clinical benefits and may be reflected in clinical outcomes.

Further evidence that the tafamidis-induced decrease in SUV retention index is associated with beneficial effects was provided by imaging of the LV. ATTR-CM patients in Cohort A had a significant improvement in LVEF (P = 0.047) and evidence of LV-GLS stabilization (P = 0.520), while patients in Cohort B showed no beneficial effect on LVEF (P = 0.295, cohort comparison: P = 0.027, Figure 6A) and experienced a significant worsening of LV longitudinal function at follow-up (P = 0.030, cohort comparison: P = 0.028, Figure 5B). These results are consistent with recently published echocardiographic data describing less deterioration of LV-GLS with tafamidis treatment.23,24 In addition, we observed significant benefits in LVCI in patients of Cohort A compared with patients in Cohort B (P = 0.034, Figure 6B), which is further supported by the results of our CMR imaging study, in which a beneficial effect of tafamidis treatment on LV function was observed.7

When focusing on the RV, we found evidence of stabilization of RV-LS in ATTR-CM patients in Cohort A (P = 0.580), while patients in Cohort B experienced a significant deterioration of RV longitudinal function (P = 0.030). This is also evident in the assessment of RV function by CMR, which showed significant benefits in patients in Cohort A compared with Cohort B (RVEF: P = 0.025, Figure 6C; RVCI: P = 0.048, Figure 6D). Interestingly, beneficial effects of tafamidis on RV function have not yet been reported in the literature. However, in ATTR-CM, amyloid fibrils can also be expected to be deposited in the RV,25 as shown by the tracer accumulation in Figure 3, demonstrating improvements in the LV and RV in Cohort A at follow-up. Therefore, tafamidis-induced reduction in cardiac SUV peak and SUV retention index in Cohort A may affect both LV and RV, as reflected by significant improvements in LVEF (P = 0.057) and RVEF (P = 0.036) in the CMR cohort.

Nevertheless, there is still uncertainty about the mechanisms underlying the beneficial response to tafamidis treatment and whether there are differences in outcomes between patients in Cohort A and Cohort B. Further long-term studies to evaluate the association between tafamidis-induced reduction in SUV retention index and outcome are warranted and will demonstrate whether highly disease-specific 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging is more sensitive than routine diagnostic monitoring.

Limitations

Several limitations are inherent to the present study. First, the present study is limited by its sample size due to the single-centre design, and centre-specific bias cannot be excluded. However, limiting data collection to one centre has the advantages of constant quality of work-up, adherence to a constant clinical routine, and constant follow-up. Second, individual differences in the duration of tafamidis treatment depending on the timing of 99mTC-DPD SPECT/CT follow-up, as well as differences between timing of baseline TTE, CMR, and 99mTC-DPD SPECT/CT imaging and follow-up may have affected the results. However, this is the first study to systematically perform serial quantitative 99mTC-DPD SPECT/CT imaging with clinical and imaging outcomes in ATTR-CM patients treated with tafamidis. Third, the significant beneficial effects on LVEF observed with CMR in Cohort A were not reflected in TTE, indicating a small observed effect. However, CMR is the established gold standard for quantification of EF.26 Fourth, although there is evidence that cardiac SUV peak correlates with ECV14 and thus with amyloid burden in the myocardium,27 this has not yet been histologically validated. However, the study’s main findings are consistent with previously published data. Finally, the observation period was too short to assess differences in outcome between cohorts.

Conclusion

Using serial quantitative 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging with SUV, we demonstrated that treatment with tafamidis 61 mg QD in ATTR-CM patients results in a significant reduction in SUV retention index, associated with significant benefits for LV and RV function and cardiac biomarkers. Our data suggest that serial quantitative 99mTc-DPD SPECT/CT imaging with SUV may be a valid tool to quantify and monitor response to tafamidis treatment in affected patients.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

None.

Contributor Information

René Rettl, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Tim Wollenweber, Division of Nuclear Medicine, Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image-guided Therapy, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, 1090 Vienna, Austria.

Franz Duca, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Christina Binder, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Bernhard Cherouny, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Theresa-Marie Dachs, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Luciana Camuz Ligios, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Lore Schrutka, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Daniel Dalos, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Dietrich Beitzke, Division of Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology, Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image-guided Therapy, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, 1090 Vienna, Austria.

Christian Loewe, Division of Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology, Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image-guided Therapy, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, 1090 Vienna, Austria.

Roza Badr Eslam, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Johannes Kastner, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria.

Marcus Hacker, Division of Nuclear Medicine, Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image-guided Therapy, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, 1090 Vienna, Austria.

Diana Bonderman, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, Vienna 1090, Austria; Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine V, Favoriten Clinic, Kundratstraße 3, 1100 Vienna, Austria.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant (ID#56478425) from Pfizer Inc. (to R.R.). However, Pfizer Inc. did not have influence on study design, data processing, or statistical analysis.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article. There is no online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Ruberg F, Berk J. Transthyretin (TTR) cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation 2012;126:1286–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gertz MA, Benson MD, Dyck PJ, Grogan M, Coelho T, Cruz Met al. . Diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy of transthyretin amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:2451–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gillmore JD, Maurer MS, Falk RH, Merlini G, Damy T, Dispenzieri Aet al. . Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation 2016;133:2404–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Armstrong IS, Hoffmann SA. Activity concentration measurements using a conjugate gradient (Siemens xSPECT) reconstruction algorithm in SPECT/CT. Nucl Med Commun 2016;37:1212–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Delcroix O, Robin P, Gouillou M, Le Duc-Pennec A, Alavi Z, Le Roux PYet al. . A new SPECT/CT reconstruction algorithm: reliability and accuracy in clinical routine for non-oncologic bone diseases. EJNMMI Res 2018;8:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wollenweber T, Rettl R, Kretschmer-Chott E, Rasul S, Kulterer O, Rainer Eet al. . In vivo quantification of myocardial amyloid deposits in patients with suspected transthyretin-related amyloidosis (ATTR). J Clin Med 2020;9:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rettl R, Mann C, Duca F, Dachs TM, Binder C, Ligios LCet al. . Tafamidis treatment delays structural and functional changes of the left ventricle in patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2022;23:767–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, Elliott PM, Merlini G, Waddington-Cruz Met al. . Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1007–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bonderman D, Pölzl G, Ablasser K, Agis H, Aschauer S, Auer-Grumbach Met al. . Diagnosis and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis: an interdisciplinary consensus statement. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2020;132:742–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lockwood PA, Le VH, O'Gorman MT, Patterson TA, Sultan MB, Tankisheva Eet al. . The bioequivalence of tafamidis 61-mg free acid capsules and tafamidis meglumine 4×20-mg capsules in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2020;9:849–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories . ATS Statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vija A. Introduction to xSPECT technology: evolving multi-modal SPECT to become context-based and quantitative. Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Molecular Imaging, White Pap 2013:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramsay SC, Lindsay K, Fong W, Patford S, Younger J, Atherton J. Tc-HDP quantitative SPECT/CT in transthyretin cardiac amyloid and the development of a reference interval for myocardial uptake in the non-affected population. Eur J Hybrid Imaging 2018;2:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scully PR, Morris E, Patel KP, Treibel TA, Burniston M, Klotz Eet al. . DPD quantification in cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13:1353–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perugini E, Guidalotti PL, Salvi F, Cooke RM, Pettinato C, Riva Let al. . Noninvasive etiologic diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis using 99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid scintigraphy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1076–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran Ket al. . Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:685–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande Let al. . Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:233–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kammerlander AA, Marzluf BA, Zotter-Tufaro C, Aschauer S, Duca F, Bachmann Aet al. . T1 mapping by CMR imaging from histological validation to clinical implication. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kramer CM, Barkhausen J, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Flamm SD, Kim RJ, Nagel E. Standardized cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) protocols: 2020 update. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2020;22:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Messroghli DR, Moon JC, Ferreira VM, Grosse-Wortmann L, He T, Kellman Pet al. . Clinical recommendations for cardiovascular magnetic resonance mapping of T1, T2, T2 and extracellular volume: a consensus statement by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) endorsed by the European Association for Cardiovascular Imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017;19:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elsadany M, Godoy Rivas C, Arora S, Jaiswal A, Weissler-Snir A, Duvall W. The use of SPECT/CT quantification of 99mTc-PYP uptake to assess tafamidis treatment response in ATTR cardiac amyloidosis. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;22:jeab111–058. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bellevre D, Bailliez A, Maréchaux S, Manrique A, Mouquet F. First follow-up of cardiac amyloidosis treated by tafamidis, evaluated by absolute quantification in bone scintigraphy. JACC Case Reports 2021;3:133–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Giblin GT, Cuddy SAM, González-López E, Sewell A, Murphy A, Dorbala Set al. . Effect of tafamidis on global longitudinal strain and myocardial work in transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2022;23:1029–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rettl R, Duca F, Binder C, Dachs TM, Cherouny B, Camuz Ligios Let al. . Impact of tafamidis on myocardial strain in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. Amyloid 2022:1–11 Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Binder C, Duca F, Stelzer PD, Nitsche C, Rettl R, Aschauer Set al. . Mechanisms of heart failure in transthyretin vs. light chain amyloidosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;20:512–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bellenger NG, Burgess MI, Ray SG, Lahiri A, Coats AJ, Cleland JGet al. . Comparison of left ventricular ejection fraction and volumes in heart failure by echocardiography, radionuclide ventriculography and cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Are they interchangeable? Eur Heart J 2000;21:1387–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duca F, Kammerlander AA, Panzenböck A, Binder C, Aschauer S, Loewe Cet al. . Cardiac magnetic resonance T 1 mapping in cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:1924–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article. There is no online supplementary material.