Abstract

Background

Although both disc‐ or osseous‐associated forms of cervical spondylomyelopathy (CSM) are observed in the same dogs, this combined form has not been thoroughly evaluated.

Objectives

To describe imaging characteristics of dogs with concurrent disc‐ and osseous CSM and investigate an association between findings on neurological examination and imaging.

Animals

Sixty dogs with disc and osseous‐associated CSM from 232 CSM‐affected dogs.

Methods

Retrospective study. Dogs diagnosed via high‐field MRI with a combination of intervertebral disc (IVD) protrusion and osseous proliferation of articular processes, dorsal lamina, or both were identified. Large and giant breed dogs were grouped according to whether combined compressions were at the same site or different sites. Statistical methods were used to investigate the association and relationship between variables.

Results

Thirty‐five out of 60 (58%) were large breeds and 22/60 (37%) were giant breeds. Mean and median age was 6.6 and 7 years respectively (range, 0.75‐11 years). Forty of the 60 dogs (67%) had concurrent osseous and disc‐associated spinal cord compression in the same location. This was considered the main compression site in 32/40 (80%) dogs. Dogs with osseous‐ and disc‐associated compressions at the same site were more likely to have a higher neurologic grade (P = .04).

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

A substantial percentage of dogs with CSM present with concomitant IVD protrusion and osseous proliferations, most at the same site. Characterizing this combined form is important in the management of dogs with CSM because it could affect treatment choices.

Keywords: canine, cervical spine, diagnostic imaging, wobbler syndrome

Abbreviations

- CSM

cervical spondylomyelopathy

- DA‐CSM

disc‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy

- IVD

intervertebral disc

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- OA‐CSM

osseous associated cervical spondylomyelopathy

- T1W

T1‐weighted

- T2W

T2‐weighted

1. INTRODUCTION

Cervical spondylomyelopathy (CSM), commonly known as wobbler syndrome, is a disorder that affects the cervical vertebral column of dogs and is characterized by compression of the cervical spinal cord, nerve roots, or both. 1 , 2

There are usually 2 recognized forms of CSM, which can be present separately or in conjunction: one mainly associated with disc protrusion and the other with osseous proliferation. 1 Disc‐associated CSM (DA‐CSM) occurs when there is spinal cord compression secondary to intervertebral disc (IVD) protrusion. 3 Osseous‐associated CSM (OA‐CSM) typically occurs when there is compression of the spinal cord resulting mainly from osseous proliferation of the articular processes. 4 , 5 Hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum can also be observed. 6

There are numerous proposed surgical techniques for treatment of CSM. A specific method often needs to be adjusted for each dog, taking into consideration direction of the compressive lesion, cause of compression, and whether there are single or multiple compressive lesions. 7

Various MRI publications describe the imaging features of disc‐ or osseous‐associated CSM 4 , 8 , 9 and although some studies mention dogs with both osseous and disc‐associated changes, 4 , 8 , 10 no detailed description of these cases was given. The goal of the present study is to describe the signalment, history, neurologic examination findings, and magnetic resonance features of dogs with concurrent disc‐ and osseous‐associated CSM and to investigate a relationship between neurologic and imaging findings. Affected dogs were grouped according to whether or not the osseous and disc‐associated compressions were present at the same site. Our hypothesis was that the presence of osseous and disc‐associated compression at the same site would be associated with a worse neurologic status on presentation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Records were retrospectively searched from January 2005 to May 2019 for dogs with a diagnosis of CSM based on clinical signs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Search terms included: “cervical spondylomyelopathy,” “CSM,” “wobbler.” Inclusion criteria was availability of medical records supporting clinical history and neurologic examination findings compatible with a cervical myelopathy, and MRI showing spinal cord compression caused by both osseous proliferation of the articular facets or dorsal laminae and IVD protrusion, whether at the same site or different sites along the cervical vertebral column. Dogs were excluded if they had CSM‐associated lesions caused exclusively by IVD protrusion (with or without ligament hypertrophy), by osseous proliferation of the articular facets (with or without ligament hypertrophy), by laminar thickening (with or without ligament hypertrophy), by ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, or by intervertebral foraminal stenosis with nerve root compression.

Signalment, history, and neurologic examination findings were obtained from the medical records for each dog. Presentation of clinical signs was considered acute when 1 week or less and chronic when more than 1 week. Signs of neurologic dysfunction were graded as follows: grade 1, cervical hyperesthesia only; grade 2, mild pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement; grade 3, moderate pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement; grade 4, marked pelvic limb ataxia or paresis with thoracic limb involvement; grade 5, tetraparesis or inability to stand or walk without assistance (adapted from a previously published grading system). 3 Additional signs such as supraspinatus muscle atrophy were also retrieved.

Magnetic resonance images were acquired using a high‐field MRI scanner (3.0T or 1.5T). Images were obtained using varying protocols but included at least sagittal T1‐weighted (T1W; TR = 450‐700 ms; TE = 8 ms) and T2‐weighted (T2W; TR = 3500‐5000 ms; TE = 110 ms) views of the cervical vertebral column from C2 to T1 and transverse T1W (TR = 500‐650 ms; TE = 8 ms) and T2W (TR = 3000‐4000 ms; TE = 120 ms) transverse views of at least the sites of spinal cord compression. The flip angle was set at 90°. Slice thickness varied between 2 and 3 mm, with no interslice interval.

A diagnosis of CSM was confirmed when there was 1 or more sites of compression of the spinal cord, nerve roots, or both observed on MRI resulting from IVD protrusion, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, osseous proliferation of the articular processes, or thickening of the dorsal lamina, as well as the presence of absolute stenosis, relative stenosis, or a combination of both, of the vertebral canal in a dog with history and neurologic examination findings compatible with a cervical myelopathy. 11

Magnetic resonance images were reviewed by a board‐certified neurologist involved in CSM research, who was blinded to the neurologic status and clinical presentation of the dogs at the time of MRI analysis. The following data were recorded: location of compressive lesions, main compressive lesion (site with the greatest reduction in cross‐sectional area and T2W hyperintensity when present), severity of the compression (mild: less than 25% of the diameter of the spinal cord; moderate: 25%‐50%, severe: greater than 50%), 5 direction of the compression (dorsal, ventral, lateral, or multidirectional when a combination of any of the previous), cause of the compression (osseous proliferation of the articular processes, IVD protrusion, 12 dorsal lamina thickening, or a combination of these). Presence of spinal cord signal changes on T1W and T2W images was investigated on sagittal and transverse as hyperintensity within the spinal cord parenchyma on T2W images and hypointensity on T1W images when compared with normal spinal cord parenchyma. 3 , 4 Intervertebral disc degeneration was also investigated on sagittal T2W images, and IVDs were classified as normal (Pfirrmann grade I), partially degenerated (Pfirrmann grades II and III) or totally degenerated (Pfirrmann grades IV and V). 13 , 14 , 15 Presence of synovial joint fluid at the articular process joint was subjectively graded as normal, decreased, or absent 4 using transverse T2W images to observe joint fluid hyperintensity and the corresponding transverse T1W images to rule out hypersignal belonging to fat. Regularity of the articular surface and presence of subchondral bone sclerosis at the articular process joint (smooth without signs of subchondral bone sclerosis, smooth with evidence of subchondral bone sclerosis, irregular with subchondral bone sclerosis) 4 was also subjectively graded using transverse T1W images. Subchondral bone sclerosis was considered when hypointense areas with irregular margins were present. Articular processes were evaluated per site. Intervertebral foraminal stenosis was also observed. T1W images were used to differentiate ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation from lamina thickening because while both soft tissue and osseous proliferation appear hypointense on T2W images, 8 bone appears much darker on T1W images.

Dogs were grouped according to whether disc‐associated and osseous‐associated compressions of the spinal cord were located at the same site (same site group) or at different sites (different sites group) and were compared for duration of clinical signs, severity of compression, direction of compression, neurologic grade, number of sites with foraminal stenosis, presence of ligamentum flavum hypertrophy/soft tissue proliferation, and presence of T2W spinal cord signal changes.

Dogs were also grouped according to median age into 2 groups: ≤7 years and >7 years. They were also divided according to breed and median age within each breed group. Giant‐breed dogs were divided into 2 subgroups: ≤5 years and >5 years. Large‐breed dogs were also separated into 2 subgroups: ≤7 years and >7 years. Age groups and breed/age subgroups were compared for the same variables used for comparison between same site and different sites groups.

Correlation was investigated between neurologic grade and direction of spinal cord compression, severity of spinal cord compression, number of sites with spinal cord compression, and presence of T2W spinal cord signal changes. Correlation was also investigated between degenerative changes of the articular process joints and IVD degeneration.

Descriptive statistics, namely frequency, mean, median, and range for categorical data were also calculated, summarized, and compiled. Association between the investigated variables was tested using chi‐square test of independence or Fisher's exact test as appropriate and Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (r) was used to calculate the relationship between variables (R v. 4.1.3, The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Correlation was classified as very weak (<0.19), weak (0.2‐0.39), moderate (0.4‐0.59), strong (0.6‐0.79), and very strong (>0.8). Positive values indicate that when 1 variable increases, so does the value of the other variable. Results were considered significant when P < .05.

3. RESULTS

Magnetic resonance imaging of 232 dogs diagnosed with CSM were reviewed. Sixty (26%) dogs met the inclusion criteria. The majority of dogs were 5 years of age or older (45/60, 75%), with ages ranging from 0.75 to 11 years at the time of diagnosis (mean: 6.6, median: 7). Fifty‐one (85%) dogs presented with proprioceptive ataxia, 34/60 (57%) with tetraparesis (7/34, 20.5%, were non‐ambulatory), and 7/60 (12%) with paraparesis. A summary of signalment and clinical signs are shown in Table 1 and a summary of MRI findings in Table 2 for dogs according to whether osseous or disc‐associated compressions were found in the same site or different sites (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of signalment and clinical signs on presentation for 60 dogs diagnosed with cervical spondylomyelopathy because of a combination of osseous‐associated and disc‐associated spinal cord compressions.

| SAME SITE | DIFFERENT SITES | |

|---|---|---|

| Number (n) of dogs | 40 | 20 |

| Mean (median) age | 7 (7) years | 6 (6) years |

| Sex | 23/40 males (58%); 17/40 females (43%) | 12/20 males (60%); 8/20 females (40%) |

| Breed size |

LARGE (n = 25, 63%): Doberman Pinscher (13/25), Labrador (3/25), Rottweiler (3/25), mixed breed (2/25), Dalmatian (1/25), Golden Retriever (1/25), Standard Poodle (1/25), Weimaraner (1/25) GIANT (n = 12, 30%): Great Dane (6/12); Swiss Mountain Dog (2/12), Saint Bernard (2/12), Bernese Mountain Dog (1/12), Newfoundland (1/12) MEDIUM (n = 2, 5%): Pit Bull Terrier (1/2), Boxer (1/2) SMALL (n = 1, 3%): Chihuahua |

LARGE (n = 10, 50%): Doberman Pinscher (5/10), mixed breed (2/10), German Shepherd (1/10), Labrador (1/10), Rottweiler (1/10) GIANT (n = 10, 50%): Great Dane (8/10), Newfoundland (1/10), Swiss Mountain Dog (1/10) |

| Acute vs chronic | Chronic (n = 29, 73%); acute (n = 11, 28%) | Chronic (n = 16, 80%); acute (n = 4, 20%) |

| Mean (median) duration of clinical signs | 110 (61) days | 342 (61) days |

| Dogs with cervical pain on palpation | 22/40 (55%) | 11/20 (55%) |

| Dogs with infraspinatus/supraspinatus muscle atrophy | 10/40 (25%) | 7/20 (35%) |

| Neurologic grade a | Grade 4 (n = 15, 38%); grade 3 (n = 14, 35%); grade 5 (n = 7, 18%); grade 2 (n = 3, 8%); grade 1 (n = 1, 3%) | Grade 3 (n = 7, 35%); grade 2 (n = 7, 35%); grade 4 (n = 5, 25%); grade 1 (n = 1, 5%) |

Note: Dogs were grouped according to whether the osseous‐ and disc‐associated compressions were located at the same site (SAME SITE) or not (DIFFERENT SITES).

Neurologic grading system: grade 1 (cervical hyperesthesia only), grade 2 (mild pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement), grade 3 (moderate pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement), grade 4 (marked pelvic limb ataxia or paresis with thoracic limb involvement), grade 5 (tetraparesis with inability to stand or walk without assistance).

TABLE 2.

Summary of magnetic resonance imaging findings for 60 dogs diagnosed with cervical spondylomyelopathy because of a combination of osseous‐associated and disc‐associated spinal cord compressions.

| SAME SITE (n = 40 dogs) | DIFFERENT SITES (n = 20 dogs) | |

|---|---|---|

| Main site of spinal cord compression | C6‐C7 (n = 21, 53%); C5‐C6 (n = 12, 30%); C4‐C5 (n = 5, 13%); C3‐C4 (n = 1, 3%); C2‐C3 (n = 1, 3%) | C6‐C7 (n = 11, 55%); C5‐C6 (n = 8, 40%); C4‐C5 (n = 1, 5%) |

| Number of sites of spinal cord compression | 2 (n = 17, 43%); 3 (n = 8, 20%); 4 (n = 7, 18%); 1 (n = 5, 13%); 5 (n = 3, 8%) | 3 (n = 7, 35%); 4 (n = 7, 35%); 2 (n = 6, 30%) |

| Severity of spinal cord compression at main compression site | Severe (n = 20, 50%); moderate (n = 17, 43%); mild (n = 3, 8%) | Moderate (n = 9, 45%); severe (n = 7, 35%); mild (n = 4, 20%) |

| Dogs with T2W hyperintensity in spinal cord parenchyma | 25/40 (63%) | 8/20 (40%) |

| Dogs with T1W hypointensity in spinal cord parenchyma | 6/40 (15%) | 1/20 (5%) |

Note: Dogs were grouped according to whether the osseous‐ and disc‐associated compressions were located at the same site (SAME SITE) or not (DIFFERENT SITES).

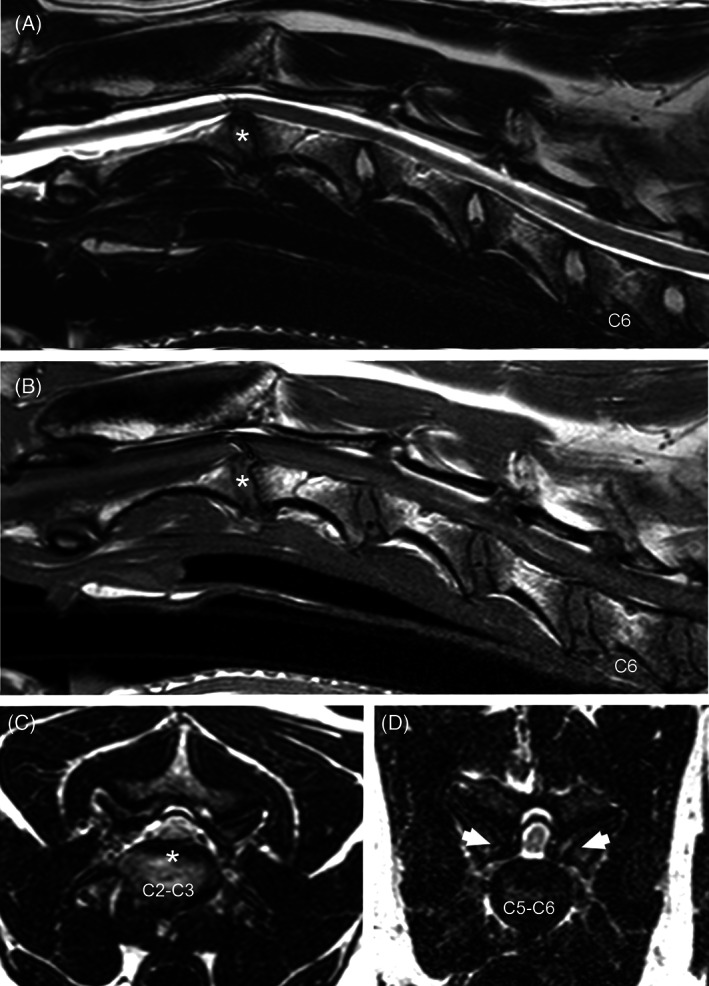

FIGURE 1.

Sagittal T2 (A) and T1‐weighted (B) and transverse T2 (C) and T1‐weighted (D) MR images from a 6‐year‐old Bernese Mountain dog with C5‐C6 ventrodorsal and C6‐C7 ventral compression with spinal cord hyperintensity at both sites. The ventral component is intervertebral disc protrusion (arrows) and the dorsal component is ligamentum flavum/soft tissue hypertrophy and dorsal lamina thickening (asterisk). There is also osseous proliferation of the articular processes seen on transverse images (C, D). Absent joint fluid can be seem at the right articular process joint and reduced joint fluid on the left articular process joint (C—open arrowheads). Subchondral bone of the articular processes was classified as smooth with signs of subchondral sclerosis bilaterally (D—open arrowheads).

Forty of the 60 dogs (67%) had combined disc‐associated and osseous‐associated spinal cord compressions at the same site, 32/40 (80%) of these were considered the main compressive site. These compressions were caused by IVD protrusion, IVD protrusion and dorsal lamina thickening with or without ligamentum flavum hypertrophy in 15 dogs, IVD protrusion and osseous proliferation of the articular processes (Figure 2) in 9 dogs (1 dog also had a synovial cyst contributing to spinal cord compression at the same site), osseous proliferation of the articular processes with dorsal lamina thickening or ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, or both in 8 dogs (1 also had synovial cyst contributing to spinal cord compression at same site). For the remaining 8/40 dogs, where concurrent disc‐ and osseous‐associated compressions in the same site were not considered as the primary compressive lesion, main compression of the spinal cord was attributed to IVD protrusion in 5 dogs, articular process proliferation and ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation in 1 dog, lamina thickening in 1 dog, and articular process proliferation in 1 dog.

FIGURE 2.

Sagittal (A) and transverse (B) T2‐weighted MR images from a 10‐year‐old Swiss Mountain dog with a mild C6‐C7 ventral (asterisk) and dorsolateral (arrow) compression caused by intervertebral disc protrusion and osseous proliferation of the right articular processes, respectively.

In the 20/60 (33%) dogs where disc‐associated and osseous‐associated compressions occurred at different sites, main compression of the spinal cord was attributed to intervertebral protrusion in 9 dogs (on its own in 7 dogs, or combined with ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation in 2 dogs), articular process proliferation in 7 dogs (on its own in 6 dogs and together with lamina thickening in 1 dog), lamina thickening and ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation in 3 dogs, and ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation in 1 dog.

The 9 dogs with main compression associated with IVD protrusion had osseus proliferation causing varying degrees of spinal cord compression at other sites (Figure 3): 2 dogs had articular process proliferation at C5‐C6, 1 of which also had lamina thickening at C3‐C4 and ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation at C4‐C5; 2 dogs had articular process proliferation at C4‐C5, 1 of which also had ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation at C3‐C4, while the other had ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation at C6‐C7 and articular process proliferation incidentally observed at C7‐T1; 1 dog had articular process proliferation at C6‐C7 with ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation at C3‐C4 and C4‐C5; 1 dog had articular process proliferation at C3‐C4; 1 dog had lamina thickening at C5‐C6 with proliferation of articular processes incidentally observed at C7‐T1; 1 dog had ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation and lamina thickening at C4‐C5, and 1 dog had ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation and lamina thickening at C3‐C4 with lamina thickening at C4‐C5.

FIGURE 3.

Sagittal T2 (A) and T1‐weighted (B) and transverse T2‐weighted (C, D) MR images from a 6‐year‐old Great Dane. Compression of the spinal cord can be seen at C2‐C3 because of intervertebral disc protrusion (asterisk), and at C5‐C6 caused by osseous proliferation of the articular processes (D—arrows). There is reduced articular joint fluid bilaterally at C5‐C6 (D). Note the presence of an artifact on sagittal T2w and T1W images over the spinal cord at C2‐C3.

The 7 dogs with main compression associated with proliferation of articular processes all had IVD protrusion in other sites: 2 dogs had IVD protrusion at C2‐C3 and articular process proliferation at C4‐C5 and C5‐C6, 2 dogs had IVD protrusion at C4‐C5 and articular process proliferation at C6‐C7, 1 dog had IVD protrusion at C2‐C3 and C4‐C5, 1 dog had articular process proliferation and IVD protrusion located at C4‐C5, and 1 dog had IVD protrusion at C3‐C4, lamina thickening at C5‐C6 with mild articular process proliferation observed incidentally at C7‐T1. Those with main compression associated with lamina thickening and ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation had IVD protrusion (2 dogs; located at C5‐C6 in 1 dog and at C2‐C3 and C3‐C4, with ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation and lamina thickening also at C6‐C7 in 1 dog) and articular process proliferation and IVD protrusion separately (1 dog with IVD protrusion located at C2‐C3 and C3‐C4 and articular process proliferation at C5‐C6). As for the 1 dog with main compression attributed to ligamentum flavum/soft tissue proliferation, articular process proliferation and IVD protrusion were observed separately at C4‐C5 and C2‐C3 respectively.

When comparing dogs from the same site group with those from the different sites group, there was a significant difference (P = .04) between neurologic grades in those 2 groups, with dogs in the same site group being more likely to have been assigned a neurologic grade of 4 or 5 (the 7 dogs with neurologic grade 5 were in the same site group). Of note, there was no significant difference for severity of spinal cord compression, and no other statistical difference between these groups was observed.

Between age groups (≤7 years and >7 years), there was a statistical difference in direction (P = .04) and severity (P = .03) of spinal cord compression. Dogs 7 years or younger were more likely to have compression classified as severity 3 than grade 2, while dogs older than 7 years were more likely to have severity grade 2 than 3. And while both groups had mostly multidirectional compressions, the second most common cause of main spinal cord compression in dogs 7 years or younger was osseous proliferation of articular processes while in dogs over 7 years of age, it was IVD protrusions. No other significant differences were observed between these groups. A summary of clinical and MRI findings can be found in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Summary of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings for 60 dogs diagnosed with cervical spondylomyelopathy due to a combination of osseous‐associated and disc‐associated spinal cord compressions grouped according to median age.

| Age | ≤7 years | >7 years |

|---|---|---|

| Number (n) of dogs | 29 | 31 |

| Sex | 17 males (59%); 12 females (41%) | 18 males (58%); 13 females (42%) |

| Acute vs chronic | Chronic (n = 26, 90%); acute (n = 3, 10%) | Chronic (n = 23, 74%); acute (n = 8, 26%) |

| Mean (median) duration of clinical signs | 243 (60) days | 136 (61) days |

| Neurologic grade a | Grade 3 (n = 12, 41%); grade 4 (n = 8, 28%); grade 2 (n = 7, 24%); grade 5 (n = 1, 4%); grade 1 (n = 1, 4%) | Grade 3 (n = 9, 29%); grade 4 (n = 12, 39%); grade 5 (n = 6, 19%); grade 2 (n = 3, 10%); grade 1 (n = 1, 3%) |

| Main site of spinal cord compression | C6‐C7 (n = 15, 52%); C5‐C6 (n = 9, 31%); C4‐C5 (n = 3, 10%); C3‐C4 (n = 1, 4%); C2‐C3 (n = 1, 4%) | C6‐C7 (n = 17, 55%); C5‐C6 (n = 11, 35%); C4‐C5 (n = 3, 10%) |

| Severity of main compression site | Grade 3 (n = 15, 52%); grade 2 (n = 8, 28%); grade 1 (n = 6, 21%) | Grade 2 (n = 18, 58%); grade 3 (n = 12, 39%); grade 1 (n = 1, 3%) |

| Dogs with T2W hyperintensity in spinal cord parenchyma | 16/29 (55%) | 17/31 (55%) |

| Dogs with T1W hypointensity in spinal cord parenchyma | 5/29 (17%) | 2/31 (7%) |

Neurologic grading system: grade 1 (cervical hyperesthesia only), grade 2 (mild pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement), grade 3 (moderate pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement), grade 4 (marked pelvic limb ataxia or paresis with thoracic limb involvement), grade 5 (tetraparesis with inability to stand or walk without assistance).

Regarding giant or large breed/age subgroups, for giant breed dogs (≤5 years and >5 years; Table 4), most dogs with T2W spinal cord parenchyma hyperintensity (8/10) were older than 5 years (P = .03). No difference was noted for the large breed/age subgroups (≤7 years and >7 years; Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Summary of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings for 22 giant breed dogs diagnosed with cervical spondylomyelopathy because of a combination of osseous‐associated and disc‐associated spinal cord compressions.

| Age | ≤5 years | >5 years |

|---|---|---|

| Number (n) of dogs | 11 | 11 |

| Sex | 9/11 males (82%); 2/11 females (18%) | 8/11 males (73%); 3/11 females (27%) |

| Acute vs chronic | Chronic (n = 11, 100%) | Chronic (n = 6, 55%); acute (n = 5, 46%) |

| Mean (median) duration of clinical signs | 211 (61) days | 477 (75) days |

| Neurologic grade a | Grade 3 (n = 5, 46%); grade 4 (n = 4, 36%); grade 2 (n = 1, 9%); grade 5 (n = 1, 9%) | Grade 3 (n = 3, 27%); grade 4 (n = 3, 27%); grade 5 (n = 3, 27%); grade 2 (n = 2, 18%) |

| Main site of spinal cord compression | C6‐C7 (n = 6, 55%); C5‐C6 (n = 4, 36%); C2‐C3 (n = 1, 9%) | C6‐C7 (n = 6, 55%); C5‐C6 (n = 3, 27%); C4‐C5 (n = 2, 18%) |

| Severity of main compression site | Grade 3 (n = 6, 55%); grade 2 (n = 3, 27%); grade 1 (n = 2, 18%) | Grade 3 (n = 7, 64%); grade 2 (n = 4, 36%) |

| Dogs with T2W hyperintensity in spinal cord parenchyma | 2/11 (18%) | 8/11 (73%) |

| Dogs with T1W hypointensity in spinal cord parenchyma | 1/11 (9%) | 2/11 (18%) |

Note: Dogs were grouped according to median age.

Neurologic grading system: grade 1 (cervical hyperesthesia only), grade 2 (mild pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement), grade 3 (moderate pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement), grade 4 (marked pelvic limb ataxia or paresis with thoracic limb involvement), grade 5 (tetraparesis with inability to stand or walk without assistance).

TABLE 5.

Summary of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings for 35 large breed dogs diagnosed with cervical spondylomyelopathy because of a combination of osseous‐associated and disc‐associated spinal cord compressions.

| Age | ≤7 years | >7 years |

|---|---|---|

| Number (n) of dogs | 19 | 16 |

| Sex | 12/19 females (63%); 7/19 males (37%) | 9/16 males (56%); 7/16 females (44%) |

| Acute vs chronic | Chronic (n = 17, 90%); acute (n = 2, 11%) | Chronic (n = 12, 75%); acute (n = 4, 25%) |

| Mean (median) duration of clinical signs | 111 (61) days | 87 (43) days |

| Neurologic grade a | Grade 3 (n = 6, 32%); grade 4 (n = 6, 32%); grade 2 (n = 6, 32%); grade 1 (n = 1, 5%) | Grade 3 (n = 6, 38%); grade 4 (n = 6, 38%); grade 5 (n = 2, 13%); grade 2 (n = 1, 6%); grade 1 (n = 1, 6%) |

| Main site of spinal cord compression | C6‐C7 (n = 13, 68%); C5‐C6 (n = 4, 21%); C4‐C5 (n = 1, 5%); C3‐C4 (n = 1, 5%) | C6‐C7 (n = 8, 50%); C5‐C6 (n = 7, 44%); C4‐C5 (n = 1, 6%) |

| Severity of main compression site | Grade 2 (n = 8, 42%); grade 3 (n = 7, 37%); grade 1 (n = 4, 21%) | Grade 2 (n = 8, 50%); grade 3 (n = 7, 44%); grade 1 (n = 1, 6%) |

| Dogs with T2W hyperintensity in spinal cord parenchyma | 14/19 (74%) | 8/16 (50%) |

| Dogs with T1W hypointensity in spinal cord parenchyma | 4/19 (21%) | 0 |

Note: Dogs were grouped according to median age.

Neurologic grading system: grade 1 (cervical hyperesthesia only), grade 2 (mild pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement), grade 3 (moderate pelvic limb ataxia or paresis ± thoracic limb involvement), grade 4 (marked pelvic limb ataxia or paresis with thoracic limb involvement), grade 5 (tetraparesis with inability to stand or walk without assistance).

Correlations between neurologic and MRI characteristics found to be statistically significant were a weak correlation between neurologic grade and direction of spinal cord compression (r = 0.31; P = .02), where multidirectional compression was associated with a higher neurologic grade, and a positive weak correlation between neurologic grade and severity of spinal cord compression (r = 0.28; P = .03).

Fifty‐nine out of 60 (98%) dogs had some degree of IVD degeneration between C2‐C3 and C6‐C7, with 50/59 (85%) having at least 3 degenerated discs between C2‐C3 and C6‐C7. A total of 132 discs were classified as partially degenerated (80 discs classified as Pfirrmann grade II and 52 discs as grade III) and 79 discs were classified as totally degenerated (65 discs classified as Pfirrmann grade IV and 14 discs as grade V) between C2‐C3 and C6‐C7. Intervertebral foraminal stenosis was present in varying degrees in 56/60 (93%) dogs.

A total of 329 out of 360 (91%) sites were available for review of articular processes. Overall, decreased or absent synovial fluid signal was observed in at least 1 location in 59/60 (98%) dogs, with a total of 281 (85%) sites affected (Figure 4). Changes to regularity of the articular surface, signs of subchondral sclerosis, or both were observed in 59/60 (98%) dogs, with a total of 270 (82%) affected sites.

FIGURE 4.

Transverse T1 (A) and T2‐weighted (B) MR images from a 4‐year‐old Labrador Retriever. Subchondral bone at the articular processes was classified as smooth with signs of subchondral sclerosis (A—asterisks). Articular joint fluid was considered absent at the right articular process joint and normal at the left articular process joint (B—arrows).

When investigating a correlation between degenerative changes in IVDs and articular processes, a very strong correlation was observed between the number of degenerated IVDs and the number of articular processes with irregular surfaces and signs of subchondral sclerosis (r = 0.84; P = .04) and the number of articular processes with absent synovial fluid signal (r = 0.85; P = .03).

4. DISCUSSION

We present the MRI findings in 60 dogs with CSM caused by a combination of disc‐ and osseous‐associated compression of the spinal cord. This report focuses specifically on dogs that had both forms of CSM. The majority of CSM publications usually divide the disease in disc‐ and osseous‐associated forms, 9 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 though various studies have included dogs with concomitant disc‐ and osseous‐associated compressions. 4 , 8 , 10 Our report shows that concomitant disc‐ and osseous‐associated CSM lesions are relatively common, affecting 26% of the dogs evaluated for this study (60 out of 232) that were diagnosed with CSM via MRI during the period of our large retrospective study. The percentage of dogs with concurrent osseous and disc‐associated spinal cord compressions in other studies varied immensely, with ranges going from approximately 9.5% to 42%, though the absolute number of dogs was much smaller (range, 2‐13). 4 , 8 , 10 Our sample size was identified out of a large pool of CSM affected dogs, as such it might more accurately reflect the percentage of combined OA‐ and DA‐CSM in dogs with CSM.

The majority of dogs that presented with combined osseous‐ and disc‐associated CSM were 5 years or older (75%), male (58%), with a chronic presentation (75%), and were more commonly Great Danes (23%) and Doberman Pinschers (30%). Main site of spinal cord compression was C6‐C7 (53%) and C5‐C6 (33%). Proprioceptive ataxia (85%) was the main presenting neurologic exam finding, followed by tetraparesis (57%). These findings suggest a mixture of what is commonly reported for disc‐ and osseous‐associated CSM. 9 , 15 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 Although there has been no verified predilection in sex for dogs with CSM, other reports have also observed a majority of affected dogs are males. 8 , 11 , 15 , 16 , 19 , 22 , 23 Though less frequent, concomitant osseous and disc‐associated lesions were present in younger dogs in our study. Age should not be used as the sole reason to discard disc protrusion since younger dogs can also present with DA‐CSM. 15 , 18 , 21 , 24

A positive weak correlation was observed between neurologic grade and severity of spinal cord compression at the principal site of compression. A positive correlation between these 2 variables has also been observed in dogs with exclusively DA‐CSM (moderate correlation in 63 dogs) 15 and OA‐CSM (weak correlation in 100 dogs). 22 Dogs with osseous‐ and disc‐associated compressions at the same site were more likely to have a higher neurologic grade; however, there was no significant difference for severity of the main compression site when comparing dogs with combined osseous‐ and disc‐associated compressions in the same site with dogs where these compressions occurred at different sites. The authors theorize that severity of spinal cord compression contributes to overall clinical presentation of these dogs, though other factors, such as the presence of dynamic lesions 25 , 26 and severity of the secondary sites of spinal cord compression might also affect manifestation of clinical signs. There is no correlation between neurologic grade and number of affected sites in dogs with DA‐CSM. 15

The authors' impression is that dogs with combined osseous‐ and disc‐associated compressions were more severely affected than dogs with DA‐CSM or OA‐CSM exclusively. This is partly supported by the percentage of dogs with neurologic grades 3 to 5 (80%) in the present study when compared to dogs with DA‐CSM (63%) 15 and OA‐CSM (74%) 22 when using the same neurologic grading method and a similar sample size.

Although it is not rare to see older large‐breed dogs with disc‐associated CSM, the simultaneous presence of osseous‐associated changes in these dogs are not commonly reported. 11 , 16 Similarly, giant‐breed dogs commonly present with osseous‐associated lesions instead of disc‐associated CSM and are considered less likely to have disc‐associated lesions. 1 , 2 The majority (58%) of the dogs in this study were large breeds (most of them Dobermans) and 37% were giant breeds (mainly Great Danes), mostly older than 5 years of age. Indeed, the large number of older dogs, with only 15/60 (25%) dogs younger than 5 years of age, might have played a role in these results since IVD protrusion is more common in older dogs 27 ; however, a study in 20 juvenile dogs with CSM showed that almost half had some degree of IVD degeneration at 1 year of age or younger. 24

An important consideration is whether both osseous‐associated and disc‐associated lesions occur independently in these dogs, or if there is some synergistic factor between them in which the changes to each motion segment from articular process changes or from IVD protrusion then contributes to the deterioration of the other component. The latter supposition does not, however, entirely explain why these dogs developed both osseous and disc‐associated changes while others developed only disc or osseous‐associated CSM. It also cannot be ruled out that the pathogenesis of DA‐CSM and OA‐CSM might have a common genetic rather than biomechanical cause, such as the association described between chondrodystrophy and IVD extrusion. 28 A very strong correlation was observed between degenerated IVDs and articular processes with surface degenerative changes and with absent synovial fluid signal. A strong correlation between the number of IVDs with total degeneration and number of articular processes with irregular surface and signs of subchondral sclerosis is observed in 63 dogs with exclusively DA‐CSM. 15 A previous study in 13 Great Danes with primarily OA‐CSM found a weak correlation between IVD degenerative changes and degenerative changes affecting the articular synovial fluid, 4 but no correlation between these factors in 100 dogs with exclusively OA‐CSM was observed. 22

Approximately half the dogs had signal changes with T2W hyperintensity observed on MRI, with only 7 dogs also having accompanying T1W hypointensity. These changes have been experimentally associated with gray matter changes such as motor neuron loss and necrosis in dogs. 29 The percentage of dogs with signal changes is similar to the average of previous reports. 4 , 8 , 11 , 15 , 17 , 22 , 30

Recognizing cases of combined forms of compression is paramount not only for surgical planning, but for determining whether or not a dog is a good surgical candidate. Although there are currently numerous surgical treatment options described for CSM, 6 , 7 , 18 , 23 , 31 the many variations in manifestation of the disease, as well as the general lack of understanding of its pathogenesis 2 make it so there is no ideal surgical treatment. Surgery is chosen based on, among other factors, cause and direction of spinal cord compression. 7 Dorsal laminectomy is often the surgery of choice for osseous‐associated lesions, 6 , 19 whereas ventral approaches are preferred for DA‐CSM. 11 , 18 , 23 The presence of combined osseous‐ and disc‐associated CSM requires careful evaluation of the viability of a surgical procedure and possibly the need for a combination of procedures.

Limitations for this study are mainly associated with its retrospective nature, such as varying imaging protocols and neurologic examination performed by different veterinary neurologists; however, all examinations were performed by board‐certified neurologists at the time of presentation and diagnosis, and MRIs were performed using a high‐field scanner and according to institutional standards and were reviewed by the same person for this study to lessen variability of subjective observations. Another limitation was that 31 out of 360 sites were not available for review on transverse images. Also, computed tomography would have been ideal for investigating osseous changes, but was not available for the vast majority of cases. The lack of dynamic MRI studies (flexion/extension) for all dogs is another limitation since severity of the compressive lesions might not fully be appreciated on neutral images. Also, since only the most severe site of compression was considered for statistical analysis, the importance of secondary compressive sites might have been underestimated.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our findings indicate that a substantial percentage of CSM‐affected dogs present with concurrent IVD protrusions and osseous changes, with more than half of these occurring at the same location. Dogs with osseous‐ and disc‐associated compressions at the same site were more likely to have a higher neurologic grade. It is important to routinely and carefully evaluate all cervical levels to make sure additional lesions are not overlooked, especially when it is customary to classify CSM cases as either resulting from IVD protrusion or osseous proliferation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no IACUC or other approval was needed. This is a retrospective imaging study. No live animals were recruited for this study.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

No funding was received for this study. The authors thank Joel Fonseca Nogueira and Luciana Bignardi de Soares Brisola Casimiro da Costa for their help with statistical analyses. The authors also thank Roberta Englebeck and Krystal Phillips from the Health Information Team from The Ohio State University Veterinary Medical Center Medical Records Department for their assistance. The contents of this manuscript were partially presented as an abstract at the 2019 European College of Veterinary Neurology (ECVN) Annual Symposium, Wroclaw, Poland.

Bonelli MA, da Costa RC. Magnetic resonance imaging and neurologic characterization of combined osseous‐ and disc‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2023;37(4):1418‐1427. doi: 10.1111/jvim.16792

REFERENCES

- 1. da Costa RC. Cervical spondylomyelopathy (wobbler syndrome) in dogs. Vet Clin N Am Small Anim Pract. 2010;40:881‐913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Decker S, da Costa RC, Volk HA, et al. Current insights and controversies in the pathogenesis and diagnosis of disc‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy in dogs. Vet Rec. 2012;171:531‐537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. da Costa RC, Parent JM, Partlow G, Dobson H, Holmberg DL, LaMarre J. Morphologic and morphometric magnetic resonance imaging features of Doberman Pinschers with and without clinical signs of cervical spondylomyelopathy. Am J Vet Res. 2006;67:1601‐1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gutierrez‐Quintana R, Penderis J. MRI features of cervical articular process degenerative joint disease in Great Dane dogs with cervical spondylomyelopathy. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2012;53:304‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martin‐Vaquero P, da Costa RC. Magnetic resonance imaging features of Great Danes with and without clinical signs of cervical spondylomyelopathy. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;245:393‐400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Risio L, Muñana K, Murray M, et al. Dorsal laminectomy for caudal cervical spondylomyelopathy: postoperative recovery and long‐term follow‐up in 20 dogs. Vet Surg. 2002;31:418‐427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Platt SR, da Costa RC. Cervical vertebral column and spinal cord. In: Tobias KM, Johnston SA, eds. Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal. 2nd ed. St. Louis MO: Elsevier; 2012:438‐484. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lipsitz D, Levitski RE, Chauvet AE, Berry WL. Magnetic resonance imaging features of cervical stenotic myelopathy in 21 dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2001;42:20‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murthy VD, Gaitero L, Monteith G. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in 26 dogs with canine osseous‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy. Can Vet J. 2014;55:169‐174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewis M, Olby NJ, Sharp NJ, Early P. Long‐term effect of cervical distraction and stabilization on neurological status and imaging findings in giant breed dogs with cervical stenotic myelopathy. Vet Surg. 2013;42(6):701‐709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. da Costa RC, Parent JM, Holmberg DL, Sinclair D, Monteith G. Outcome of medical and surgical treatment in dogs with cervical spondylomyelopathy: 104 cases (1988‐2004). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;233:1284‐1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Decker S, Gomes SA, Packer RM, et al. Evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging guidelines for differentiation between thoracolumbar intervertebral disk extrusions and intervertebral disk protrusions in dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2016;57:526‐533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, et al. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:1873‐1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bergknut N, Auriemma E, Wijsman S, et al. Evaluation of intervertebral disk degeneration in chondrodystrophic and nonchondrodystrophic dogs by use of Pfirrmann grading of images obtained with low‐field magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Vet Res. 2011;72(7):893‐898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonelli MA, da Costa LBSBC, da Costa RC. Magnetic resonance imaging and neurological findings in dogs with disc‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy: a case series. BMC Vet Res. 2021;17(1):145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Decker S, Bhatti SF, Duchateau L, et al. Clinical evaluation of 51 dogs treated conservatively for disc‐associated wobbler syndrome. J Small Anim Pract. 2009;50(3):136‐142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gasper JA, Rylander H, Stenglein JL, et al. Osseous‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy in dogs: 27 cases (2000‐2012). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;244:1309‐1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Solano MA, Fitzpatrick N, Bertran J. Cervical distraction‐stabilization using an intervertebral spacer screw and string‐of pearl (SOP™) plates in 16 dogs with disc‐associated wobbler syndrome. Vet Surg. 2015;44(5):627‐641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Poad L, Smith M, De Decker S. Comparing the clinical presentation and outcomes of dogs receiving medical or surgical treatment for osseous‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy. Vet Rec. 2022;190(6):e831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lewis DG. Cervical spondylomyelopathy (‘wobbler’ syndrome) in the dog: a study based on 224 cases. J Small Anim Pract. 1989;30:657‐665. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stabile F, Bernardini M, Bevilacqua G. Neurological signs and pre‐ and post‐traction low‐field MRI findings in Dobermanns with disc‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56:331‐338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bonelli MA, da Costa LBSBC, da Costa RC. Association of neurologic signs with high‐field MRI findings in 100 dogs with osseous‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2021;62(6):678‐686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Steffen F, Voss K, Morgan JP. Distraction‐fusion for caudal cervical spondylomyelopathy using an intervertebral cage and locking plates in 14 dogs. Vet Surg. 2011;40(6):743‐752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Albuquerque BM, da Costa RC. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging characterization of cervical spondylomyelopathy in juvenile dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33(5):2160‐2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Provencher M, Habing A, Moore SA, Cook L, Phillips G, Costa RC. Kinematic magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of disc‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy in Doberman Pinschers. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30:1121‐1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Provencher M, Habing A, Moore SA, Cook L, Phillips G, da Costa RC. Evaluation of osseous‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy in dogs using kinematic magnetic resonance imaging. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2017;58:411‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Decker S, Gielen IM, Duchateau L, et al. Evolution of clinical signs and predictors of outcome after conservative medical treatment for disk‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;240:848‐857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brown EA, Dickinson PJ, Mansour T, et al. FGF4 retrogene on CFA12 is responsible for chondrodystrophy and intervertebral disc disease in dogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(43):11476‐11481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. al‐Mefty O, Harkey HL, Marawi I, et al. Experimental chronic compressive cervical myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:550‐561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eagleson JS, Diaz J, Platt SR, et al. Cervical vertebral malformation‐malarticulation syndrome in the Bernese mountain dog: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging features. J Small Anim Pract. 2009;50:186‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rohner D, Kowaleski MP, Schwarz G, Forterre F. Short‐term clinical and radiographical outcome after application of anchored intervertebral spacers in dogs with disc‐associated cervical spondylomyelopathy. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2019;32(2):158‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]