Abstract

Ectopic calcification is characterized by inappropriate deposition of calcium mineral in non-skeletal connective tissues and can cause significant morbidity and mortality, particularly when it affects the cardiovascular system. Identification of the metabolic and genetic determinants of ectopic calcification could help distinguish individuals at greatest risk of developing these pathological calcifications and could guide development of medical interventions. Inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) has long been recognized as the most potent endogenous inhibitor of biomineralization. It has been intensively studied as both a marker and a potential therapeutic for ectopic calcification. Decreased extracellular concentrations of PPi have been proposed to be a unifying pathophysiological mechanism for disorders of ectopic calcification, both genetic and acquired. However, is reduced plasma concentrations of PPi a reliable predictor of ectopic calcification? This perspective article evaluates the literature in favor and against a pathophysiological role of plasma versus tissue PPi dysregulation as a determinant of, and as a biomarker for, ectopic calcification.

Keywords: ECTOPIC CALCIFICATION, INORGANIC PYROPHOSPHATE, ANIMAL MODELS, BIOMARKER

Ectopic calcification and the role of inorganic pyrophosphate

Inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) was first identified in 1961 as a potent inhibitor of in vitro calcium phosphate precipitation.(1) It was subsequently found that PPi is a normal component of urine and plasma, important for the prevention of calcification of collagen, elastin and other nucleation sites in vivo.(2,3) Subcutaneous injection of PPi inhibited vitamin D-induced aortic calcification in rats.(4) PPi was shown to be a potent, mineral-binding, small molecule inhibitor of crystal nucleation and growth.(5) Micromolar concentrations of PPi were sufficient to inhibit the deposition of hydroxyapatite crystals in connective tissues in the presence of millimolar concentrations of calcium (Ca) and phosphate (Pi).(6) Although the mechanism by which PPi inhibits hydroxyapatite crystal growth is not entirely known, PPi is thought to adsorb specifically to crystal growth sites, thus preventing further apposition of mineral ions. This mechanism of inhibiting mineralization has led to the description of PPi as a physiological “water-softener” that prevents pathological soft tissue calcification.(7,8) By contrast, degradation of PPi to Pi in bones and teeth by tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) enables the physiological mineralization of these tissues.(9)

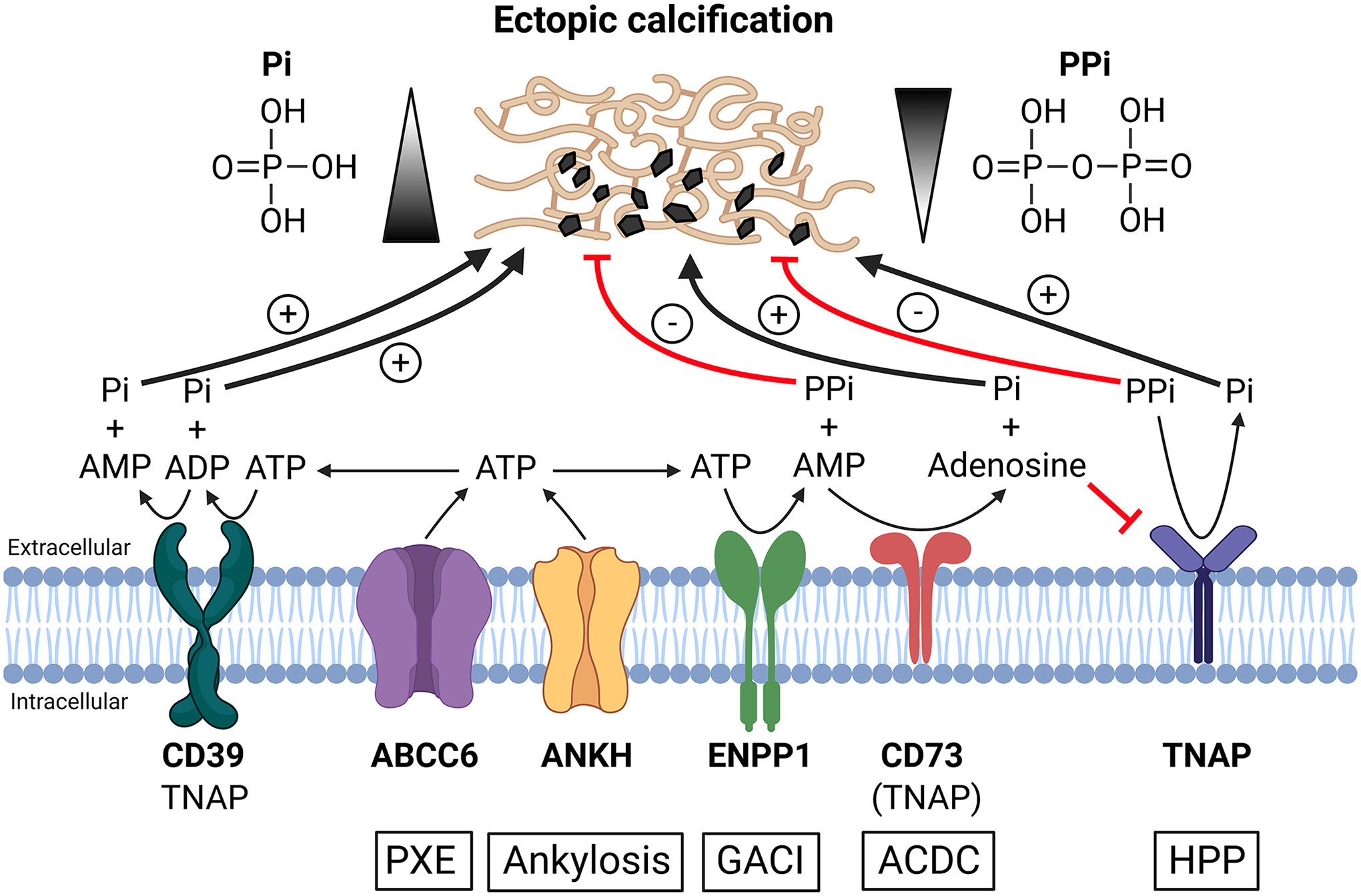

PPi is a by-product of many intracellular metabolic reactions. PPi is also produced in the extracellular matrix of most tissues, where it acts as a potent inhibitor of mineral nucleation and growth. The ABCC6, ENPP1, ANKH, CD73, and TNAP proteins are key players of extracellular PPi metabolism (Figure 1). Under physiological conditions, ABCC6 mediates the release of ATP primarily from hepatocytes into the extracellular space, whereas ANKH extrudes ATP from cells in a wide variety of tissues including joints, bones, and kidney. Extracellular ATP is converted into AMP and PPi by ENPP1, an ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1.(10,11) ENPP1 is the principal enzyme that hydrolyzes extracellular ATP to AMP and PPi, as circulating levels of PPi are low or absent in mice and GACI type 1 patients with genetic deficiency of ENPP1. ABCC6 activity is responsible for about 60–70% of plasma PPi concentrations while ANKH accounts for about 20% of plasma PPi.(12,13) CD73 converts AMP to Pi and adenosine, the second of which inhibits TNAP-mediated hydrolysis of PPi to Pi. TNAP is the key enzyme involved in the breakdown of PPi. TNAP is also a very potent ATPase, able to generate 3 molecules of Pi as ATP is hydrolyzed sequentially into ADP, AMP and adenosine.(9,14,15) Loss-of-function mutations in the TNAP protein cause hypophosphatasia (HPP), a rare inherited disorder of bone and mineral metabolism manifesting osteomalacia and rickets due to excessive levels of extracellular PPi.(16) Thus, extracellular PPi homeostasis is regulated by a balanced action of ABCC6, ANKH, and ENPP1 that promote PPi synthesis, and the opposing action of TNAP that catalyzes the degradation of ATP, ADP, AMP and PPi (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the synthesis and hydrolysis of PPi, a potent inhibitor of pathologic tissue calcification.

The underlying mechanisms of ectopic calcification remain poorly understood despite the current understanding of a seemingly linear biochemical pathway revealed by the coordinated actions of several proteins regulating the homeostasis of extracellular PPi. Autosomal recessive diseases, PXE, ankylosis, GACI, ACDC, and HPP, are caused by loss-of-function mutations in ABCC6, ANKH, ENPP1, CD73 and TNAP proteins, respectively. ABCC6 and ANKH facilitate ATP release from hepatocytes and peripheral cells, respectively, to extracellular milieu. Extracellularly released ATP is converted by ENPP1into AMP and PPi, the latter being an anti-calcification factor. CD39 competes with ENPP1 for the extracellular ATP and converts ATP into ADP and further ADP to AMP and two molecules of the pro-calcification molecule Pi. CD73 converts AMP to Pi and adenosine, the latter inhibits TNAP, an enzyme that hydrolyzes ATP and PPi. TNAP also hydrolyzes ATP to ADP, ADP to AMP, and AMP to adenosine. Deficiencies in ABCC6, ANKH, ENPP1 and CD73 proteins lead to reduced plasma PPi levels promoting pathologic calcification. By contrast, deficiency in TNAP causes defective bone mineralization in HPP due to excessive plasma PPi levels. An equilibrium between concentrations of extracellular PPi and Pi regulates ectopic calcification and normal skeletal mineralization.

Several genetic disorders that feature ectopic calcification are associated with dysregulated extracellular PPi homeostasis.(17) They include pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), generalized arterial calcification of infancy (GACI), ankylosis, and arterial calcification due to deficiency of CD73 (ACDC), all transmitted via autosomal recessive modes. PXE (OMIM 264800) is characterized by late-onset yet progressive accumulation of calcium mineral at ectopic sites, including the skin, eyes, and cardiovascular system.(18) The classical forms of PXE are caused by loss-of-function mutations in the ABCC6 gene, encoding a transmembrane efflux transporter ABCC6 protein expressed primarily in the liver. GACI is an extremely severe, early-onset vascular calcification disease often diagnosed by prenatal ultrasound revealing calcium deposits in the fetal heart and arteries.(19) Based on the mutated genes, GACI is classified into two types, GACI type 1 (OMIM 208000) and GACI type 2 (OMIM 614473) which are associated with inactivating mutations in the ENPP1 and ABCC6 genes, respectively. Regardless of the two types, most patients with GACI die before six months of age.(20,21) In contrast to GACI, ankylosis and ACDC (OMIM 211800) are adult-onset calcification disorders of elderly individuals. Patients with ankylosis develop calcification of tissues and poorly perfused bodily fluids, such as cartilage, intervertebral disc, and synovial fluid of joints.(22) Patients with ACDC develop arterial calcification in the lower extremities and calcification in joint capsules of the hands and feet causing severe pain.(23) Ankylosis and ACDC are caused by biallelic inactivating mutations in the ANKH and NT5E genes, encoding ANKH (ANK in mice) and CD73 proteins, respectively.

While we don’t understand which components of PPi metabolism act locally and which influence plasma PPi, these hereditary disorders, PXE, GACI, ankylosis, and ACDC, are all characterized by reduced circulating levels of PPi, and reduced concentrations of this important physiological inhibitor of mineralization is considered responsible for ectopic calcification in soft connective tissues.(17) This perspective article summarizes the role of circulating PPi in genetic and acquired disorders associated with ectopic calcification. We refer to systemic levels of PPi as measured by plasma PPi and by local PPi we mean PPi produced in situ at the cellular level. While the plasma PPi assay has been optimized, it still remains largely a research tool at the moment, although it may become more widely available in the near future. To our knowledge however, there are no assays that can measure extracellular PPi in vivo or in tissue sections, so this remains a major difficulty in this field. In our research papers, we have sometimes measured PPi output in primary cultures as a surrogate for local production of PPi.(24–26) Due to the lack of standardization of blood collection, processing, and assay method, there are inconsistencies in the plasma PPi concentrations reported by different laboratories, which might obscure the interpretation of the role of plasma PPi in ectopic calcification.

Experimental models where plasma PPi was a reliable predictor of ectopic calcification

Vascular calcification in GACI correlates with plasma PPi levels

Enpp1−/− knockout mice (Enpp1tm1Gdg), a rodent model of human GACI, have essentially no detectable plasma PPi and develop extensive aortic calcification by two months of age.(27) Allografts of aorta from wild-type mice into Enpp1−/− mice resulted in calcification of the donor tissue, but the amount of calcification was less than the adjacent endogenous Enpp1−/− aorta. Abnormal aortic tissue from Enpp1−/− mice showed no further calcification after transplantation into wild-type mice. These results showed that normal circulating levels of PPi overcame the absence of local PPi and prevented vascular calcification, but also that the role of local PPi production in the vascular tissue could partially prevent calcification in the presence of low plasma PPi.(27)

Genetic overexpression of human ENPP1 and administration of an ENPP1-Fc enzyme restore plasma PPi levels and completely prevent ectopic calcification in Enpp1 mutant mice

Homozygous Enpp1asj mice, so-named because they develop a peculiar joint stiffness as they age (“ages with stiffened joints,” asj), represent a useful model of human GACI.(28) These mice harbor a p.V246D missense mutation in ENPP1 resulting in absence of ENPP1 protein. Accordingly, homozygous Enpp1asj mice had low plasma PPi levels, widespread ectopic calcification, defects in bone quality and mineralization, and early mortality.(28) Crossing the Enpp1asj mice with transgenic mice ubiquitously overexpressing a human ENPP1 transgene produced Enpp1asj mice that had wild-type plasma concentrations of PPi and which did not develop ectopic calcification or bone mineralization defects.(29)

Similarly, enzyme replacement therapy with injections of recombinant ENPP1-Fc enzyme in Enpp1asj and Enpp1ttw (the “tip toe walking” mouse is another model of GACI due to genetic deficiency of ENPP1) mice normalized plasma levels of PPi, prevented ectopic calcification, improved bone mineralization, and prevented mortality.(30,31) ENPP1-Fc enzyme replacement therapy also prevented neointimal proliferation and improved blood pressure and cardiovascular functions in Enpp1ttw and Enpp1asj−2J mice (the asj-2J mutation is allelic to asj).(32,33) An ENPP1-Fc enzyme, INZ-701, is currently being studied in a phase 1/2, multi-center, open-label, first-in-human clinical trial in GACI type 1 patients (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04686175).

Human ABCC6 transgene restores plasma PPi and prevents ectopic calcification in Abcc6−/− mice

Abcc6−/− knockout mice serve as a model of PXE. After expressing low level of human ABCC6 transgene in the liver, the Abcc6−/− mice had a modest 27% increase in plasma PPi levels that led to a significant reduction in acute dystrophic cardiac calcification and chronic skin calcification.(34) Similarly, injection of young Abcc6−/− mice with recombinant adenovirus to achieve liver-targeted expression of human ABCC6 cDNA prior to the development of ectopic calcification was associated with sustained hepatic expression of human ABCC6 protein for up to 4 weeks, which normalized plasma PPi levels and prevented tissue calcification.(35)

Plasma PPi levels correlate with age of onset and severity of ectopic calcification in genetic disorders of PXE, GACI, and ACDC

The diagnosis of GACI is often made by prenatal or perinatal ultrasound and/or CT imaging that shows echo brightness or calcium deposition in vascular tissues. ENPP1-deficient patients with GACI type 1 have plasma PPi levels that are 0–10% of healthy controls,(33) indicating that most or all PPi in plasma is derived from ENPP1-mediated hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and other nucleoside triphosphates. Due to extensive arterial calcification, GACI patients have a 55% mortality rate before the age of 6 months.(36) By contrast, PXE is late-onset with the skin, eye, and cardiovascular involvements not noticeable until the patients are in their 20s or 30s, and the majority of PXE patients have a normal life expectancy. Individuals diagnosed with PXE have plasma PPi levels at 30–40% of wild-type controls.(10) ACDC is an adult-onset disorder in which ectopic calcification primarily affects the joints and lower extremity arteries. While plasma PPi levels have not been reported in patients with ACDC, circulating levels of PPi in the CD73-deficient mouse model of ACDC are approximately 50% of that in wild-type controls.(37) These observations suggest that the varying degree of reduced plasma PPi concentrations correlates, in general, with the onset and severity of the ectopic calcification phenotypes in PXE (60–70% reduction; late onset), GACI (90–100% reduction; prenatal or perinatal onset), and ACDC (50% reduction; adult onset) (Figure 1).

PPi and bisphosphonates prevent ectopic calcification in preclinical and clinical studies

Administration of PPi and non-hydrolyzable PPi analogs such as the bisphosphonates prevented ectopic calcification, attesting to the importance of PPi as a major regulator of hydroxyapatite deposition. Oral administration or subcutaneous injection of the first generation bisphosphonate etidronate increased bone mass and significantly reduced skin calcification in Abcc6−/− and Enpp1asj mice.(38,39) Daily intraperitoneal injections of PPi or etidronate that led to transient increases of plasma PPi inhibited acute dystrophic cardiac calcification and prevented spontaneous skin calcification in Abcc6−/− mice.(34) Oral administration of the tetra-sodium salt of PPi to Abcc6−/− mice and Enpp1ttw mice by ad libitum access to supplemented drinking water attenuated skin, vascular, and cardiac calcification, and this PPi salt is readily absorbed in humans.(40) Additionally, pregnant heterozygous Enpp1ttw mice that drank tetra-sodium PPi-containing water produced homozygous Enpp1ttw offspring with significantly reduced skin and vascular calcification when assessed after weaning.(40) Delivery of di-sodium and potassium salt of PPi in gelatin capsule provides an effective PPi delivery system in humans and avoids excess sodium intake, which was previously found to cause gastro-intestinal discomfort.(41) Although an inadvertent discovery, increasing the amount of PPi in the chow to 7.1 times greater than the concentration in standard chow attenuated dystrophic cardiac calcification and skin calcification in Abcc6−/− mice, providing additional evidence that dietary PPi can modulate ectopic calcification.(42)

Etidronate inhibited femoral artery calcification and subretinal neovascularization events in a double-blinded single-center one-year study consisting of 74 adult PXE patients.(43) A post-hoc analysis showed that etidronate significantly stopped calcification progression in all vascular beds except for the coronary arteries.(44)

Plasma PPi levels are low in other genetic and acquired disorders of ectopic calcification

Plasma PPi concentrations are low in other clinical conditions in which ectopic calcification occurs, such as chronic kidney disease,(45–47) systemic sclerosis,(48) and progeria.(49) The reduced plasma PPi in a mouse model of progeria is caused by increased activities of TNAP and CD39 that enhance PPi hydrolysis and reduce the availability of ATP for PPi generation. As a corollary, intensive treatment with the combination of ATP, the TNAP inhibitor levamisole, and the CD39 inhibitor ARL67156, prevented vascular calcification and increased longevity in these mice.(49) PPi and bisphosphonates also reduce arterial calcification in animals with renal failure,(50,51) and pharmacological TNAP inhibition led to an increase in plasma PPi that prevented aortic calcification in a murine model of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder.(52)

Experimental models where plasma PPi was not a reliable predictor of ectopic calcification

Patients who are ENPP1 heterozygotes or ABCC6 homozygotes display completely different phenotypes despite similarly reduced plasma PPi levels

Recent studies suggest that some patients who are heterozygous for ENPP1 variants manifest early-onset osteoporosis.(53,54) These individuals have plasma PPi levels similar to ABCC6 homozygotes with PXE.(53) In addition, ABCC6-PXE patients have similar reductions in plasma PPi levels to ABCC6-GACI type 2 patients.(55) Furthermore, although most patients with biallelic ENPP1 variants develop GACI type 1, some patients instead manifest typical PXE despite having similarly low plasma PPi levels.(56) Plasma PPi does not fully explain the extent of ectopic calcification and divergent phenotypes of these patients, suggesting the involvement of local, cell-specific effects of ENPP1 and ABCC6 on various tissues, and the compounding effects of systemic factors such as plasma Ca, Pi, and Mg, and fetuin-A levels.(57–59)

Genetic overexpression of human ENPP1 and administration of an ENPP1-Fc enzyme restore plasma PPi levels but do not completely prevent ectopic calcification in Abcc6−/− mice

Crossing Abcc6−/− mice with transgenic mice carrying the human ENPP1 cDNA generates Abcc6−/− mice with normal plasma levels of PPi. These mice still developed ectopic calcification although it was significantly less than the Abcc6−/− mice.(29) The same results were observed in Abcc6−/− mice after administration of ENPP1-Fc, a recombinant ENPP1 enzyme. Ectopic calcification was not completely prevented even with a high dose of ENPP1-Fc that caused plasma PPi levels to exceed those of wild-type mice.(60) These results suggest that ENPP1 did not correct the underlying ABCC6 deficiency, and suggest that local PPi levels may be determinant in those tissues affected by ectopic calcification in the PXE mice.

Novel mouse models carrying the p.H362A and p.T238A ENPP1 missense mutations develop distinct phenotypes albeit low plasma PPi levels

The characterization of the Enpp1asj mouse model of GACI has shed light on the catalytic activity of the ENPP1 protein through its ability to hydrolyze ATP to generate PPi, thereby regulating soft tissue calcification and bone mineralization. In addition to ATP, ENPP1 was recently found to hydrolyze extracellular cyclic GMP-AMP (2’,3’-cGAMP), an agonist for the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) that is evaluated as a target in cancer immunotherapy.(61) The distinct roles of ENPP1’s catalytic activities on ATP and cGAMP on plasma PPi, ectopic calcification, bone mineralization, and immune responses were recently analyzed using two mouse models with different missense mutations in the ENPP1 protein, p.H362A and p.T238A, that were generated by CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing.(62,63) These mutant mice have striking biochemical and phenotypical differences from the Enpp1asj mice (Table 1). Because the p.V246D mutation in the Enpp1asj mouse leads to a deficiency of ENPP1 protein, these mice are unable to hydrolyze both ATP and cGAMP. By contrast, mutant mice with p.H362A or p.T238A mutation express the mutant ENPP1 proteins at levels that are similar to the wild-type protein in normal mice. When analyzed in vitro, the ENPP1 p.H362A mutant cannot hydrolyze cGAMP while maintaining the hydrolysis activity of ATP to produce AMP and PPi.(62) By contrast, ex vivo hydrolysis of ATP was similarly reduced in plasma from Enpp1asj and the p.H362A mutant mice, and plasma concentrations of PPi were comparably reduced in both mutant mouse lines relative to wild-type mice. Remarkably, despite having plasma levels of PPi that are as low as in the Enpp1asj mice, the p.H362A mutant mice do not exhibit ectopic calcification and defective bone mineralization seen in Enpp1asj mice. Exogenously added ATP was, however, degraded in the liver lysate of the p.H362A mice, suggesting that tissue PPi rather than circulating PPi prevents the development of ectopic calcification in these mice.(62) While cGAMP is not responsible for the devastating vascular calcification phenotype in GACI, it was shown to be responsible for antiviral immunity and systemic inflammation.(62) The ENPP1 p.T238A mutant lacks catalytic activity for hydrolysis of both ATP and cGAMP, allowing for ENPP1 protein signaling to be studied uncoupled from its enzymatic activity. These mice have plasma PPi as low as in the Enpp1asj mice, yet they develop normal trabecular bone microarchitecture, have favorable bone biomechanical properties, and develop less severe joint calcification than Enpp1asj mice.(63)

Table 1.

Biochemical findings and clinical features of mouse models with different mutations in the Enpp1 gene

| Characteristics | Mouse models with Enpp1 mutations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| p.V246D (asj) | p.H362A | p.T238A | |

| Biochemical features: | |||

| Is ENPP1 protein made | No | Yes | Yes |

| Hydrolysis of ATP | No | Yes | No |

| Hydrolysis of 2’3’-cGAMP | No | No | No |

| Plasma PPi | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Plasma Pi | ↓ | Similar to WT mice | ↓ |

| Plasma FGF23 | ↑ | Not reported | ↑ |

| Plasma PTH | ↑ | Not reported | ↑ |

| Phenotypical features: | |||

| Breeding and lifespan | Difficulty breeding beyond 2–3 mo | Normal lifespan and readily breed | Increased mortality beyond 20 wks |

| Stiffened posture | Yes | No | Less severe than asj mice |

| Ectopic calcification | Wide spread, many tissues affected | Very minimal (only muzzle, ear, and airway analyzed) | Less severe than asj mice (only joints of forepaws analyzed) |

| Vascular stenosis | No | Not reported | Not reported |

| Bone (μCT, histomorphometry) | ↓BMD (trabecular and cortical bone) | Not reported | Normal trabecular bone, Moderate changes of cortical bone |

| Bone (mechanic property) | ↓ | Not reported | Maximal load similar to WT mice, stiffness and total work less severe than asj mice |

| Calvarial mineralization | ↓ | Not reported | ↑ |

| Wnt inhibitor Sfrp1 expression | ↑ | Not reported | ↓ |

Overexpression and inhibition of TNAP drives and inhibits ectopic calcification, respectively, without altering plasma PPi levels

TNAP is a known regulator of eutopic and ectopic calcification. The role of TNAP in soft tissue and bone mineralization through hydrolysis of PPi has been well studied. TNAP deficiency occurs in patients with hypophosphatasia (HPP), a genetic disorder characterized by impaired mineralization of the skeleton and teeth featuring rickets and early loss of teeth in children or osteomalacia and dental problems in adults caused by accumulation of extracellular PPi concentrations.(16) As a corollary, one would postulate that increased TNAP expression would enhance PPi hydrolysis and thereby reduce plasma PPi levels, with consequent development of ectopic calcification. The characterization of three TNAP transgenic mice point to a more complicated scenario. Transgenic mice in which overexpression of human TNAP targeted to osteoblasts had serum alkaline phosphatase activity 10–20 times of wild-type mice. These mice exhibited increased bone mineralization, yet their plasma PPi levels were not different from wild-type mice.(64) The vascular smooth muscle cell-specific and endothelial cell-specific human TNAP transgenic mice had serum alkaline phosphatase activity that was 4–20 and 20–35 times of the wild-type mice, respectively.(65,66) These mice had normal plasma PPi levels, yet they developed severe arterial calcification.(65,66) The results suggest that normal plasma PPi levels do not explain the occurring of ectopic calcification, and suggest instead that local tissue levels of PPi determine hydroxyapatite deposition in calcification-prone tissues. The lack of an apparent effect of those higher levels of plasma TNAP on plasma PPi could be attributed in part to the fact that TNAP is physiologically inhibited by normal plasma concentrations of Pi.(67)

When TNAP was overexpressed instead via administration of an AAV8-hTNAP-D10 vector targeting TNAP expression in the bone, serum alkaline phosphatase activity was increased 500–800 times in the wild-type and Alpl−/− mice.(68) Plasma PPi was then significantly suppressed in these mice, yet there was no ectopic calcification in the kidneys, aorta, coronary arteries, and brain in a 70-day follow-up.(68) Similar findings were reported for asfotase alfa, a recombinant and bone-targeted TNAP enzyme currently used for the treatment of patients with HPP.(69) This, however, is not unexpected given the documented dual requirement for the local co-expression of TNAP in the context of a collagenous matrix as necessary and sufficient to mineralize any extracellular matrix.(70)

Genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of TNAP via Abcc6−/−Alpl+/− mice (with ~50% reduction of serum alkaline phosphatase activity) and the pharmacological TNAP inhibitor SBI-425, respectively, showed significant inhibition of ectopic calcification in Abcc6−/− mice.(71) In an independent study, SBI-425 also attenuated tissue calcification in Abcc6−/− mice without altering bone mineralization.(72) In these studies, plasma PPi levels were not altered, suggesting the contribution of local events, such as increased tissue levels of PPi, to the therapeutic effects of TNAP inhibition.

Plasma PPi levels do not correlate with the degree of ectopic calcification and disease severity in PXE patients

A study was performed with 107 French PXE patients and 26 healthy controls investigating the relationship between plasma PPi levels, coronary calcification, lower limbs arterial calcification, and disease severity by Phenodex score.(73) The results of this study show that plasma PPi concentration is lower in PXE patients compared to healthy controls and that arterial calcification is strongly dependent on age but not on plasma PPi levels.(73) Correlations of plasma PPi levels and serum alkaline phosphatase activities are reported with conflicting results in PXE patients.(73,74)

Plasma PPi is not a determinant of serum T50 measuring serum calcification propensity in PXE patients

Serum samples from a cohort of 57 Belgian PXE patients were evaluated via the T50 serum calcification propensity assay.(75) T50 was found to be an independent predictor of ocular, vascular, and overall disease severity in PXE. Multivariate regression analysis identified serum levels of fetuin-A, phosphorus, and magnesium but not PPi as significant determinants of T50.(75) The serum T50 score, however, does not measure apatite formation, the site of action of PPi. Furthermore, this test was done in serum, which does not reflect plasma PPi due to release of PPi from platelets. Thus, PPi would not be expected to alter the serum calcification propensity score.

Conclusions and future prospects

Identifying genetic and metabolic determinants for ectopic calcification is of paramount importance toward understanding the drivers and inhibitors of the ectopic calcification process in general. Unquestionably, PPi is a critical mediator of ectopic calcification. There are, however, emerging data suggesting that circulating PPi may not be a good proxy for extracellular PPi levels in tissues prone to calcification, and that changes in local PPi concentrations may exert a profound role controlling ectopic calcification. Unfortunately, there is currently no method for determining the level of extracellular PPi in tissues. Such an assay, if developed, could help answer some of the unexplained findings. In addition to PPi, ectopic calcification is also influenced by Ca, Pi, Mg, and fetuin-A levels in the blood and diet and variations in those may also affect comparisons between studies and models.

Acknowledgement

This paper is dedicated to the memory of our dear colleague Jouni Uitto, M.D., Ph.D. (1943–2022), who passed away while this paper was being peer-reviewed.

Grant numbers and sources of support:

The original work of the authors has been supported by the PXE International, and the NIH/NIAMS grants K01AR64766 (QL), R01AR28450 (JU), R01AR55225 (JU), R01AR72695 (QL and JU), R21AR77332 (QL), R21AR80277 (QL), and R01DE12889 (JLM).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Qiaoli Li: Conceptualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Douglas Ralph: writing – review and editing. Michael Levine: writing – review and editing. José Luis Millán: writing – review and editing. Jouni Uitto: writing – review and editing.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable - no new data generated.

References

- 1.Fleish H, Neuman WF. Mechanisms of calcification: role of collagen, polyphosphates, and phosphatase. Am J Physiol. Jun 1961;200:1296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleisch H, Bisaz S. Isolation from urine of pyrophosphate, a calcification inhibitor. Am J Physiol. Oct 1962;203:671–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleisch H, Bisaz S. Mechanism of calcification: inhibitory role of pyrophosphate. Nature. Sep 1 1962;195:911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleisch H, Schibler D, Maerki J, Frossard I. Inhibition of aortic calcification by means of pyrophosphate and polyphosphates. Nature. Sep 18 1965;207(5003):1300–1. Epub 1965/09/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer JL. Can biological calcification occur in the presence of pyrophosphate? Arch Biochem Biophys. May 15 1984;231(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleisch H, Russell RG, Straumann F. Effect of pyrophosphate on hydroxyapatite and its implications in calcium homeostasis. Nature. Nov 26 1966;212(5065):901–3. Epub 1966/11/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orriss IR. Extracellular pyrophosphate: The body’s “water softener”. Bone. May 2020;134:115243. Epub 2020/01/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orriss IR, Arnett TR, Russell RG. Pyrophosphate: a key inhibitor of mineralisation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. Jun 2016;28:57–68. Epub 2016/04/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millan JL. The role of phosphatases in the initiation of skeletal mineralization. Calcif Tissue Int. Oct 2013;93(4):299–306. Epub 20121127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansen RS, Duijst S, Mahakena S, Sommer D, Szeri F, Varadi A, et al. ABCC6-mediated ATP secretion by the liver is the main source of the mineralization inhibitor inorganic pyrophosphate in the systemic circulation-brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. Sep 2014;34(9):1985–9. Epub 2014/06/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansen RS, Kucukosmanoglu A, de Haas M, Sapthu S, Otero JA, Hegman IE, et al. ABCC6 prevents ectopic mineralization seen in pseudoxanthoma elasticum by inducing cellular nucleotide release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Dec 10 2013;110(50):20206–11. Epub 2013/11/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szeri F, Niaziorimi F, Donnelly S, Fariha N, Tertyshnaia M, Patel D, et al. The Mineralization Regulator ANKH Mediates Cellular Efflux of ATP, Not Pyrophosphate. J Bone Miner Res. Feb 11 2022. Epub 20220211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szeri FNF, Donnelly S, Fariha N, Tertyshnaia M, Patel D, Lundkvist S, van de Wetering K. Ankylosis homologue mediates cellular efflux of ATP, not pyrophosphate. bioRxiv 2021;doi: 10.1101/2021.08.27.457978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciancaglini P, Yadav MC, Simao AM, Narisawa S, Pizauro JM, Farquharson C, et al. Kinetic analysis of substrate utilization by native and TNAP-, NPP1-, or PHOSPHO1-deficient matrix vesicles. J Bone Miner Res. Apr 2010;25(4):716–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simao AM, Yadav MC, Narisawa S, Bolean M, Pizauro JM, Hoylaerts MF, et al. Proteoliposomes harboring alkaline phosphatase and nucleotide pyrophosphatase as matrix vesicle biomimetics. J Biol Chem. Mar 5 2010;285(10):7598–609. Epub 20100104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whyte MP. Hypophosphatasia and the role of alkaline phosphatase in skeletal mineralization. Endocr Rev. Aug 1994;15(4):439–61. Epub 1994/08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ralph D, van de Wetering K, Uitto J, Li Q. Inorganic Pyrophosphate Deficiency Syndromes and Potential Treatments for Pathologic Tissue Calcification. Am J Pathol. May 2022;192(5):762–70. Epub 20220216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neldner KH. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Clin Dermatol. Jan-Mar 1988;6(1):1–159. Epub 1988/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rutsch F, Ruf N, Vaingankar S, Toliat MR, Suk A, Hohne W, et al. Mutations in ENPP1 are associated with ‘idiopathic’ infantile arterial calcification. Nat Genet. Aug 2003;34(4):379–81. Epub 2003/07/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira CR, Hackbarth ME, Ziegler SG, Pan KS, Roberts MS, Rosing DR, et al. Prospective phenotyping of long-term survivors of generalized arterial calcification of infancy (GACI). Genet Med. Feb 2021;23(2):396–407. Epub 2020/10/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferreira CR, Kintzinger K, Hackbarth ME, Botschen U, Nitschke Y, Mughal MZ, et al. Ectopic Calcification and Hypophosphatemic Rickets: Natural History of ENPP1 and ABCC6 Deficiencies. J Bone Miner Res. Nov 2021;36(11):2193–202. Epub 20210816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morava E, Kuhnisch J, Drijvers JM, Robben JH, Cremers C, van Setten P, et al. Autosomal recessive mental retardation, deafness, ankylosis, and mild hypophosphatemia associated with a novel ANKH mutation in a consanguineous family. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Jan 2011;96(1):E189–98. Epub 2010/10/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.St Hilaire C, Ziegler SG, Markello TC, Brusco A, Groden C, Gill F, et al. NT5E mutations and arterial calcifications. N Engl J Med. Feb 3 2011;364(5):432–42. Epub 2011/02/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hessle L, Johnson KA, Anderson HC, Narisawa S, Sali A, Goding JW, et al. Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase and plasma cell membrane glycoprotein-1 are central antagonistic regulators of bone mineralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jul 9 2002;99(14):9445–9. Epub 20020624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson KA, Hessle L, Vaingankar S, Wennberg C, Mauro S, Narisawa S, et al. Osteoblast tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase antagonizes and regulates PC-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. Oct 2000;279(4):R1365–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yadav MC, Simao AM, Narisawa S, Huesa C, McKee MD, Farquharson C, et al. Loss of skeletal mineralization by the simultaneous ablation of PHOSPHO1 and alkaline phosphatase function: a unified model of the mechanisms of initiation of skeletal calcification. J Bone Miner Res. Feb 2011;26(2):286–97. Epub 20100803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lomashvili KA, Narisawa S, Millan JL, O’Neill WC. Vascular calcification is dependent on plasma levels of pyrophosphate. Kidney Int. Jun 2014;85(6):1351–6. Epub 2014/04/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Guo H, Chou DW, Berndt A, Sundberg JP, Uitto J. Mutant Enpp1asj mice as a model for generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Dis Model Mech. Sep 2013;6(5):1227–35. Epub 2013/06/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao J, Kingman J, Sundberg JP, Uitto J, Li Q. Plasma PPi Deficiency Is the Major, but Not the Exclusive, Cause of Ectopic Mineralization in an Abcc6(−/−) Mouse Model of PXE. J Invest Dermatol. Nov 2017;137(11):2336–43. Epub 2017/06/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albright RA, Stabach P, Cao W, Kavanagh D, Mullen I, Braddock AA, et al. ENPP1-Fc prevents mortality and vascular calcifications in rodent model of generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Nat Commun. Dec 1 2015;6:10006. Epub 2015/12/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng Z, O’Brien K, Howe J, Sullivan C, Schrier D, Lynch A, et al. INZ-701 Prevents Ectopic Tissue Calcification and Restores Bone Architecture and Growth in ENPP1-Deficient Mice. J Bone Miner Res. Aug 2021;36(8):1594–604. Epub 20210505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan T, Sinkevicius KW, Vong S, Avakian A, Leavitt MC, Malanson H, et al. ENPP1 enzyme replacement therapy improves blood pressure and cardiovascular function in a mouse model of generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Dis Model Mech. Oct 8 2018;11(10). Epub 2018/08/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nitschke Y, Yan Y, Buers I, Kintziger K, Askew K, Rutsch F. ENPP1-Fc prevents neointima formation in generalized arterial calcification of infancy through the generation of AMP. Exp Mol Med. Oct 29 2018;50(10):1–12. Epub 2018/10/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pomozi V, Brampton C, van de Wetering K, Zoll J, Calio B, Pham K, et al. Pyrophosphate Supplementation Prevents Chronic and Acute Calcification in ABCC6-Deficient Mice. Am J Pathol. Jun 2017;187(6):1258–72. Epub 2017/04/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang J, Snook AE, Uitto J, Li Q. Adenovirus-Mediated ABCC6 Gene Therapy for Heritable Ectopic Mineralization Disorders. J Invest Dermatol. Jun 2019;139(6):1254–63. Epub 2019/01/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutsch F, Boyer P, Nitschke Y, Ruf N, Lorenz-Depierieux B, Wittkampf T, et al. Hypophosphatemia, hyperphosphaturia, and bisphosphonate treatment are associated with survival beyond infancy in generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. Dec 2008;1(2):133–40. Epub 2009/12/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q, Price TP, Sundberg JP, Uitto J. Juxta-articular joint-capsule mineralization in CD73 deficient mice: similarities to patients with NT5E mutations. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(16):2609–15. Epub 2014/12/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Q, Kingman J, Sundberg JP, Levine MA, Uitto J. Dual Effects of Bisphosphonates on Ectopic Skin and Vascular Soft Tissue Mineralization versus Bone Microarchitecture in a Mouse Model of Generalized Arterial Calcification of Infancy. J Invest Dermatol. Jan 2016;136(1):275–83. Epub 2016/01/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Q, Sundberg JP, Levine MA, Terry SF, Uitto J. The effects of bisphosphonates on ectopic soft tissue mineralization caused by mutations in the ABCC6 gene. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(7):1082–9. Epub 2015/01/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dedinszki D, Szeri F, Kozak E, Pomozi V, Tokesi N, Mezei TR, et al. Oral administration of pyrophosphate inhibits connective tissue calcification. EMBO Mol Med. Nov 2017;9(11):1463–70. Epub 2017/07/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kozak E, Fulop K, Tokesi N, Rao N, Li Q, Terry SF, et al. Oral supplementation of inorganic pyrophosphate in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Exp Dermatol. Nov 10 2021. Epub 2021/11/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pomozi V, Julian CB, Zoll J, Pham K, Kuo S, Tokesi N, et al. Dietary Pyrophosphate Modulates Calcification in a Mouse Model of Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum: Implication for Treatment of Patients. J Invest Dermatol. May 2019;139(5):1082–8. Epub 2018/11/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kranenburg G, de Jong PA, Bartstra JW, Lagerweij SJ, Lam MG, Ossewaarde-van Norel J, et al. Etidronate for Prevention of Ectopic Mineralization in Patients With Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum. J Am Coll Cardiol. Mar 13 2018;71(10):1117–26. Epub 2018/03/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartstra JW, de Jong PA, Kranenburg G, Wolterink JM, Isgum I, Wijsman A, et al. Etidronate halts systemic arterial calcification in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Atherosclerosis. Jan 2020;292:37–41. Epub 2019/11/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lomashvili KA, Khawandi W, O’Neill WC. Reduced plasma pyrophosphate levels in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. Aug 2005;16(8):2495–500. Epub 2005/06/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Neill WC, Sigrist MK, McIntyre CW. Plasma pyrophosphate and vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. Jan 2010;25(1):187–91. Epub 2009/07/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Risseeuw S, van Leeuwen R, Imhof SM, de Jong PA, Mali W, Spiering W, et al. The effect of etidronate on choroidal neovascular activity in patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0240970. Epub 20201020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsu VM, Kozak E, Li Q, Bocskai M, Schlesinger N, Rosenthal A, et al. Inorganic pyrophosphate is reduced in patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). Mar 2 2022;61(3):1158–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villa-Bellosta R ATP-based therapy prevents vascular calcification and extends longevity in a mouse model of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Nov 19 2019;116(47):23698–704. Epub 2019/11/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lomashvili KA, Monier-Faugere MC, Wang X, Malluche HH, O’Neill WC. Effect of bisphosphonates on vascular calcification and bone metabolism in experimental renal failure. Kidney Int. Mar 2009;75(6):617–25. Epub 20090107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Neill WC, Lomashvili KA, Malluche HH, Faugere MC, Riser BL. Treatment with pyrophosphate inhibits uremic vascular calcification. Kidney Int. Mar 2011;79(5):512–7. Epub 2010/12/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tani T, Fujiwara M, Orimo H, Shimizu A, Narisawa S, Pinkerton AB, et al. Inhibition of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase protects against medial arterial calcification and improves survival probability in the CKD-MBD mouse model. J Pathol. Jan 2020;250(1):30–41. Epub 2019/09/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oheim R, Zimmerman K, Maulding ND, Sturznickel J, von Kroge S, Kavanagh D, et al. Human Heterozygous ENPP1 Deficiency Is Associated With Early Onset Osteoporosis, a Phenotype Recapitulated in a Mouse Model of Enpp1 Deficiency. J Bone Miner Res. Mar 2020;35(3):528–39. Epub 20191205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kato H, Ansh AJ, Lester ER, Kinoshita Y, Hidaka N, Hoshino Y, et al. Identification of ENPP1 Haploinsufficiency in Patients With Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis and Early-Onset Osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. Jun 2022;37(6):1125–35. Epub 20220411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agarwal N, Agarwal U, Alfirevic Z, Lim J, Kaleem M, Landes C, et al. Skeletal abnormalities secondary to antenatal etidronate treatment for suspected generalised arterial calcification of infancy. Bone Rep. Jun 2020;12:100280. Epub 20200513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ralph D, Nitschke Y, Levine MA, Caffet M, Wurst T, Saeidian AH, et al. ENPP1 variants in patients with GACI and PXE expand the clinical and genetic heterogeneity of heritable disorders of ectopic calcification. PLoS Genet. Apr 2022;18(4):e1010192. Epub 20220428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Babler A, Schmitz C, Buescher A, Herrmann M, Gremse F, Gorgels T, et al. Microvasculopathy and soft tissue calcification in mice are governed by fetuin-A, magnesium and pyrophosphate. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228938. Epub 2020/02/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jahnen-Dechent W, Buscher A, Koppert S, Heiss A, Kuro OM, Smith ER. Mud in the blood: the role of protein-mineral complexes and extracellular vesicles in biomineralisation and calcification. J Struct Biol. Oct 1 2020;212(1):107577. Epub 20200722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang Q, Dibra F, Lee MD, Oldenburg R, Uitto J. Overexpression of fetuin-a counteracts ectopic mineralization in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (abcc6(−/−)). J Invest Dermatol. May 2010;130(5):1288–96. Epub 20100121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jacobs IJ, Cheng Z, Ralph D, O’Brien K, Flaman L, Howe J, et al. INZ-701, a recombinant ENPP1 enzyme, prevents ectopic calcification in an Abcc6(−/−) mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Exp Dermatol. Jul 2022;31(7):1095–101. Epub 20220516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Onyedibe KI, Wang M, Sintim HO. ENPP1, an Old Enzyme with New Functions, and Small Molecule Inhibitors-A STING in the Tale of ENPP1. Molecules. Nov 19 2019;24(22). Epub 20191119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carozza JA, Cordova AF, Brown JA, AlSaif Y, Bohnert V, Cao X, et al. ENPP1’s regulation of extracellular cGAMP is a ubiquitous mechanism of attenuating STING signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. May 24 2022;119(21):e2119189119. Epub 20220519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zimmerman K, Liu X, von Kroge S, Stabach P, Lester ER, Chu EY, et al. Catalysis-Independent ENPP1 Protein Signaling Regulates Mammalian Bone Mass. J Bone Miner Res. Sep 2022;37(9):1733–49. Epub 20220729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Narisawa S, Yadav MC, Millan JL. In vivo overexpression of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase increases skeletal mineralization and affects the phosphorylation status of osteopontin. J Bone Miner Res. Jul 2013;28(7):1587–98. Epub 2013/02/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Savinov AY, Salehi M, Yadav MC, Radichev I, Millan JL, Savinova OV. Transgenic Overexpression of Tissue-Nonspecific Alkaline Phosphatase (TNAP) in Vascular Endothelium Results in Generalized Arterial Calcification. J Am Heart Assoc. Dec 16 2015;4(12). Epub 2015/12/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sheen CR, Kuss P, Narisawa S, Yadav MC, Nigro J, Wang W, et al. Pathophysiological role of vascular smooth muscle alkaline phosphatase in medial artery calcification. J Bone Miner Res. May 2015;30(5):824–36. Epub 2014/11/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coburn SP, Mahuren JD, Jain M, Zubovic Y, Wortsman J. Alkaline phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.1) in serum is inhibited by physiological concentrations of inorganic phosphate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Nov 1998;83(11):3951–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kinoshita Y, Mohamed FF, Amadeu de Oliveira F, Narisawa S, Miyake K, Foster BL, et al. Gene Therapy Using Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 8 Encoding TNAP-D10 Improves the Skeletal and Dentoalveolar Phenotypes in Alpl(−/−) Mice. J Bone Miner Res. Sep 2021;36(9):1835–49. Epub 20210615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Millan JL, Narisawa S, Lemire I, Loisel TP, Boileau G, Leonard P, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for murine hypophosphatasia. J Bone Miner Res. Jun 2008;23(6):777–87. Epub 2007/12/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murshed M, Harmey D, Millan JL, McKee MD, Karsenty G. Unique coexpression in osteoblasts of broadly expressed genes accounts for the spatial restriction of ECM mineralization to bone. Genes Dev. May 1 2005;19(9):1093–104. Epub 20050415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Q, Huang J, Pinkerton AB, Millan JL, van Zelst BD, Levine MA, et al. Inhibition of Tissue-Nonspecific Alkaline Phosphatase Attenuates Ectopic Mineralization in the Abcc6(−/−) Mouse Model of PXE but Not in the Enpp1 Mutant Mouse Models of GACI. J Invest Dermatol. Feb 2019;139(2):360–8. Epub 2018/08/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ziegler SG, Ferreira CR, MacFarlane EG, Riddle RC, Tomlinson RE, Chew EY, et al. Ectopic calcification in pseudoxanthoma elasticum responds to inhibition of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase. Sci Transl Med. Jun 7 2017;9(393). Epub 2017/06/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leftheriotis G, Navasiolava N, Clotaire L, Duranton C, Le Saux O, Bendahhou S, et al. Relationships between Plasma Pyrophosphate, Vascular Calcification and Clinical Severity in Patients Affected by Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum. J Clin Med. May 5 2022;11(9). Epub 20220505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sanchez-Tevar AM, Garcia-Fernandez M, Murcia-Casas B, Rioja-Villodres J, Carrillo JL, Camacho M, et al. Plasma inorganic pyrophosphate and alkaline phosphatase in patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Ann Transl Med. Dec 2019;7(24):798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nollet L, Van Gils M, Fischer S, Campens L, Karthik S, Pasch A, et al. Serum Calcification Propensity T50 Associates with Disease Severity in Patients with Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum. J Clin Med. Jun 28 2022;11(13). Epub 20220628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable - no new data generated.