Abstract

The purpose of this study was to report current practices and attitudes of child and adolescent psychiatrists (CAP) regarding diagnostic genetic and pharmacogenetic (PGx) testing. We surveyed 958 US-based practicing CAP. 54.9% of respondents indicated that they had ordered/referred for a genetic test in the past 12 months. 87% of respondents agreed that it is their role to discuss genetic information regarding psychiatric conditions with their patients; however, 45% rated their knowledge of genetic testing practice guidelines as poor/very poor. The most ordered test was PGx (32.2%), followed by chromosomal microarray (23.0%). 73.4% reported that PGx is at least slightly useful in child and adolescent psychiatry. Most (62.8%) were asked by a patient/family to order PGx in the past 12 months and 41.7% reported they would order PGx in response to a family request. Those who ordered a PGx test were more likely to have been asked by a patient/family and to work in private practice. 13.8% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that a PGx test can predict the effectiveness of specific antidepressants. Some respondents also indicated they would make clinical changes based on PGx information even if a medication was currently effective and there were no side effects. Genetic testing has become routine clinical care in child and adolescent psychiatry. Despite this, many providers rate their associated knowledge as poor/very poor. Patient requests were associated with ordering practices and providers misinterpretation of PGx may be leading to unnecessary changes in clinical management. There is need for further education and support for clinicians.

Keywords: genetics, psychopharmacology, genetic testing, practice patterns, child and adolescent psychiatry, survey, ethics

1. Introduction

The past decade has seen the identification of hundreds of genomic loci associated with psychiatric conditions, the ability to generate polygenic risk scores for psychiatric conditions, and the emergence of commercially available pharmacogenetic (PGx) tests aimed specifically at psychotropic medications (Brainstorm Consortium et al., 2018; Fan & Bousman, 2020; Lu et al., 2021; Müller, 2020; Murray et al., 2021). A study of US-based psychiatrists found that 14% ordered genetic tests in the past 6 months, and 41% had patients ask about genetic testing (Salm et al., 2014). A decade later, there are few data on current practices and attitudes towards genetic testing among adult or child and adolescent psychiatrists (CAP).

Genetic testing is currently part of the standard of care in the evaluation of children and adults for some neuropsychiatric conditions, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Hyman et al., 2020; Manickam et al., 2021; Volkmar et al., 2014) and intellectual and developmental disorders (IDD) (Manickam et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2020), where results can impact subsequent medical decision making (Harris et al., 2020; Manickam et al., 2021; Stafford & Sanchez-Lara, 2022); (e.g. detecting inborn errors of metabolism can lead to specific treatments)(Abdelhakim et al., 2020), and genetic diagnoses can trigger screening and follow up for associated medical conditions (Manickam et al., 2021; Stafford & Sanchez-Lara, 2022). Numerous professional organizations recommend genetic testing to evaluate ASD, but implementation remains low (Harris et al., 2020; Moreno-De-Luca et al., 2020; Soda et al., 2021).

A different category of genetic test can be used to guide pharmacological treatments (Bousman et al., 2021; Ramsey et al., 2021). The FDA has approved medication inserts with pharmacogenetically-determined medication dose recommendations for certain medications, including commonly prescribed psychotropic medications such as citalopram (PharmGKB, 2020) and aripiprazole (PharmGKB, 2019). Clinical guidelines regarding PGx tests have been released (Bousman et al., 2021; Hicks et al., 2015), including for carbamazepine dosing and HLA-B genotype (Leckband et al., 2013), and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for individuals carrying certain CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 alleles (Hicks et al., 2015, Hicks et al., 2017). Currently, various commercial PGx laboratory-developed tests with accompanying decision-support tools are available for patients with psychiatric disorders (Ontario Health, 2021). Individual hospital-based laboratories have also developed test panels to examine genes deemed relevant (e.g., Mayo Clinic, University of Florida).

In the US, genetic testing has a complicated regulatory landscape; the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services certifies individual laboratories performing laboratory testing performed on human specimens under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2023. The Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act gave regulatory authority to all food, drug, and cosmetic sales to the Food and Drug Administration. Included in this were the regulation of medical devices. The Medical Device Amendments of 1976 classified diagnostic tests as medical devices and thus genetic tests are also regulated by the FDA.

Despite the regulatory authority, many genetic tests are developed and analyzed by a single laboratory and were marketed as laboratory developed tests (LDT) wherein the FDA has largely practiced enforcement discretion (FDA, 2021). CLIA largely ensures that each laboratory has mechanisms to ensure that the testing done at that particular laboratory’s assays are valid and the laboratory has personnel and equipment to ensure proficiency in the tests offered. CLIA thus has mechanisms to ensure analytical validity; however, it does not address whether a particular test offered by a lab has clinical utility or clinical validity. The clinical utility and validity of Chromosomal Microarray based assays to detect copy number variation in the context of developmental delay and intellectual developmental disorder has been evaluated by the FDA as an in-vitro diagnostic, as it has an assay to detect the number of CGG repeats in the FMR1 gene (Fragile X syndrome is caused by genetic changes in this gene) (FDA, 2023). Clearance as an in-vitro diagnostic does not necessarily make it comprehensive nor superior than an LDT. For example, the FDA-cleared test for Fragile X is in and of itself insufficient, as other tests (e.g., Southern blot, sequencing of the FMR1 gene for rare variants) are necessary for a complete evaluation of the FMR1 gene if clinical suspicion warrants it.

Numerous other laboratories use the same, or similar, technologies for the detection of CNVs and CGG repeats; there have been studies on the variability within the analytical sensitivity of various laboratory-developed CMAs to detect CNVs of different sizes, depending on the particular assay or probes utilized within an assay or downstream processing of information used (Wang et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the clinical utility of true positive results obtained from these assays has been well established, with subsequent changes in clinical management.

Combinatorial PGx tests have also been developed as LDTs. There has also been great variability in the various PGx assays developed, both in the number of genes and regions assayed and the categorization of genotypes to phenotypes, to such a degree that attempts to discuss it as a class is difficult (Bousman & Dunlop, 2018). The degree to which PGx testing can help guide optimal pharmacological treatment remains debated. Studies meta-analyzing the results from commercial tests have shown improved rates of remission for some tests, not for others when these tests were utilized (Bousman et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2022; Ontario Health, 2021). Limitations of these studies include the subpopulations in which the studies were conducted and the discordance between results based on the specific test utilized. Professional organizations that represent psychiatrists in the United States (American Psychiatric Association, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists, American Society of Geriatric Psychiatrists, International Society of Psychiatric Genetics (International Society of Psychiatric Genetics, 2019) have not endorsed the routine use of these tests to date. What is clear is that a nuanced understanding and discussion of this topic is necessary instead of general statements that this broad class of testing can or cannot benefit care.

Given a decade of quick advances in psychiatric genomics research and debates about the utility of PGx, it is important to identify and understand psychiatrists’ current practices, understanding, and attitudes regarding genetic testing. Here we report on the survey results regarding current practices, knowledge, and attitudes regarding genetic testing used as part of clinical care with a focus on PGx testing.

2. Methods

Design and Setting

The Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine approved this study (protocol number H-46219). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Survey methods have been previously described (see Pereira et al., 2022). Briefly, a 47-question survey was developed to assess CAP current practice, knowledge, and perceptions toward genetic testing based on current literature with input from an expert panel consisting of CAP, psychologists, genetic counselors, bioethicists, lawyers, and an anthropologist using a modified Delphi method (Dalkey & Helmer, 1963). The survey included three sections: general (diagnostic) genetic testing, PGx testing, and polygenic risk scores. Survey participants were recruited from publicly available listservs, professional organizations, national conferences, and other professional meetings. Web searches were conducted to identify other publicly available contact information for CAP.

The survey was administered in English, and was electronically distributed over a four-week period in June 2020 using Qualtrics©. Questions about the current use of general genetic testing and PGx testing were used to learn about CAP knowledge, experience, opinions on current and potential future utility, and concerns and appropriateness of PGx testing. For results on knowledge and perceptions of the utility of genetic testing in the evaluation of ASD, see (Soda et al., 2021), and for results related to polygenic risk scores, see (Pereira et al., 2022). The survey is found as supplementary file 1.

Measures

The survey items were designed to ascertain clinicians’ knowledge about genetic testing in psychiatry, experiences with ordering genetic testing, perceived current and future utility of genetic testing, and clinicians’ views on the potential impact of genetic testing on mental health stigma.

Self-rated knowledge of genetic testing:

Respondents self-rated their knowledge about genetic testing in psychiatry, genetic testing guidelines in psychiatry, and knowledge about how to integrate genetic test results and PGx test results into practice. Response options included: Very Poor, Poor, Good, or Very Good.

Experiences/Current practices with ordering genetic testing:

Ordering practices were ascertained using up to six questions nested in conditional response queues. The first question asked whether a respondent ordered any genetic testing in the past 12 months as a yes/no question. If the respondent selected yes, they were then asked the approximate percentage of patients for whom they ordered genetic tests and whether they involved a genetic specialist when considering and/or interpreting genetic tests.

Participants reported the conditions for which genetic tests were ordered (e.g., ASD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder), the type of test ordered (e.g., Chromosomal microarray, targeted testing for a specific disorder), and their reasons for ordering (e.g., diagnostic clarification, medication side effects). All questions were multiple-choice with multiple selections enabled, and included an option to write in responses not listed.

Current and future utility of genetic testing in psychiatry:

Respondents reported perceived current and future utility for genetic testing for ASD, IDD, for reasons other than for ASD/IDD, and child and adolescent psychiatry broadly. Response options included: Not at all useful, Slightly useful, Useful, Very useful.

Attitudes toward role in genetic testing in psychiatry:

Respondents reported whether they feel it is their role to discuss genetic information regarding psychiatric illness with patients and their families. Response options included: Strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree.

Interpretation and clinical translation of knowledge of pharmacogenetics:

Respondents reported whether there is sufficient evidence that PGx test results can predict the effectiveness of one antidepressant medication over another on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”). Respondents were also allowed to answer, “I do not know”. Respondents were also asked, “If PGx test results show that a patient is at an increased risk for a serious side effect, but the patient has responded well to the medication without any significant side effects, how likely are you to:” change the medication or change the dose of the current medication. Response options included: Very unlikely, Unlikely, Likely, or Very likely.

Statistical Methods:

Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square and logistic regression. When cell sizes were small, Fisher’s exact Test was used to compare the categorical groups. For comparisons of the current or future utility of genetic testing, McNemar changes tests (McNemar, 1947) were computed. Continuous variables were assessed using analysis of variance and two-sided p-values (p < .05) are reported.

3. Results

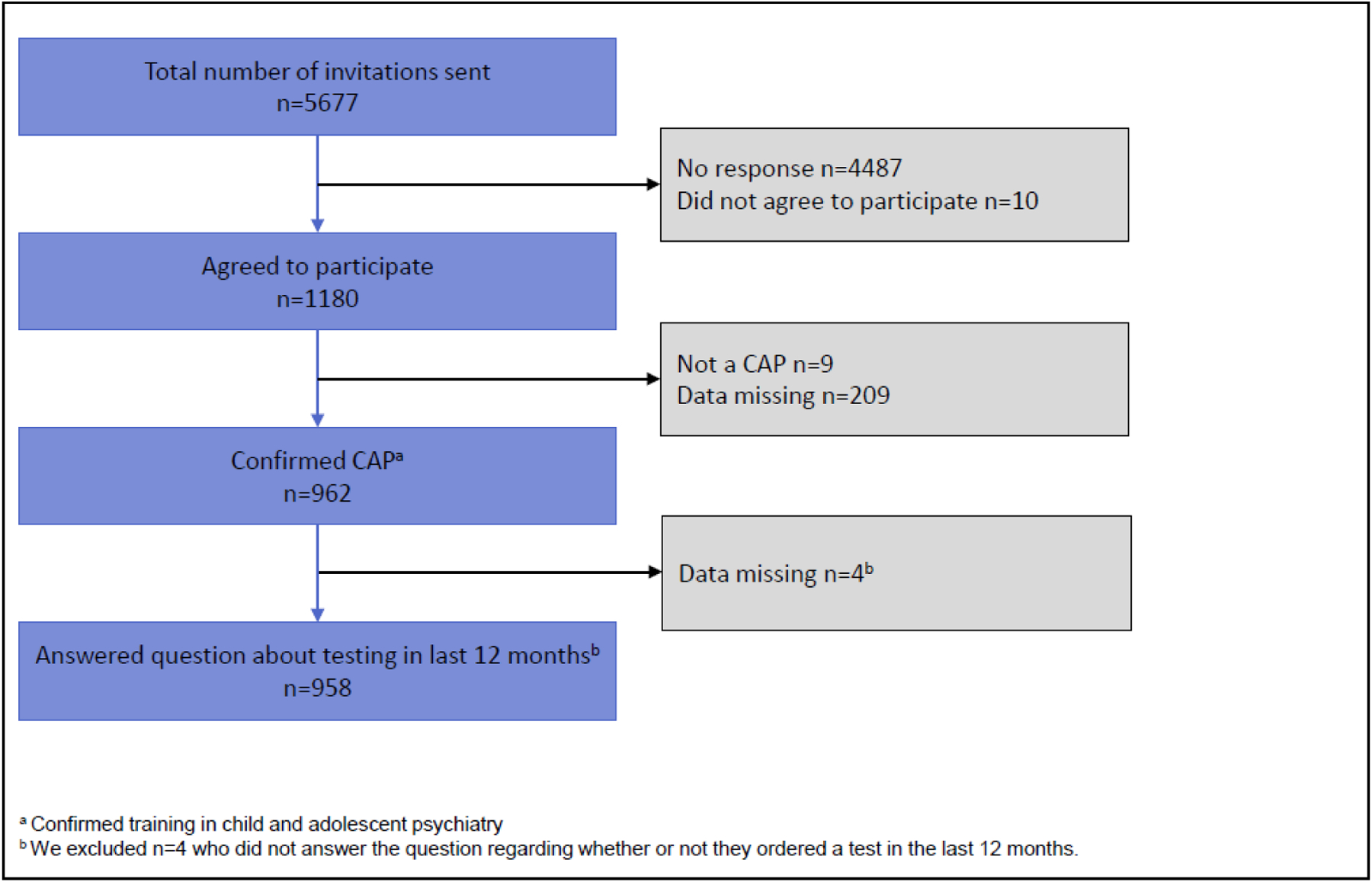

The survey was distributed to 5,677 individuals. Of 1180 who agreed to participate, 962 completed surveys were obtained (16.9% completion rate), which reflects ~11.6% of practicing U.S. CAP. Four participants were excluded because they did not indicate whether they ordered genetic testing in the past 12 months, for a final total of 958 respondents included in analyses. See Figure 1 for the study flow diagram and see Table 1 for participant characteristics.

Figure 1:

Diagram of study flow

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Participant Characteristics | Total sample (n=958)* |

|---|---|

| Gender | (n=952) |

| Female: | 474 (49%) |

| Male: | 453 (48%) |

| Prefer Not to Say: | 25 (3%) |

| Other: | 1 (<1%) |

| Trans Male: | 1 (<1%) |

| Ethnicity | (n=951) |

| White/European American: | 662 (70%) |

| Asian: | 95 (10%) |

| Prefer Not to Say: | 54 (6%) |

| Black/African American: | 36 (4%) |

| Hispanic/Latinx: | 36 (4%) |

| Mixed Ethnicity/Race: | 33 (3%) |

| Other: | 17 (2%) |

| Middle Eastern/Mediterranean: | 13 (1%) |

| American Indian/Native American: | 4 (<1%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: | 1 (<1%) |

| Number of years in Clinical Practice as CAP | (n=956) |

| 16+ years: | 529 (55%) |

| 6–10 years: | 178 (19%) |

| 11–15 years: | 167 (17%) |

| 1–5 years: | 61 (6%) |

| CAP Fellow: | 19 (2%) |

| Resident: | 2 (<1%) |

| Medical Practice Setting a | (n=951) |

| Private Practice: | 380 (40%) |

| Clinic: | 266 (28%) |

| University Medical Center: | 225 (24%) |

| Hospital: | 132 (14%) |

| Community Agency: | 114 (12%) |

| Psychiatric Hospital: | 83 (9%) |

| Other: | 70 (7%) |

| Government: | 31 (3%) |

| Retired: | 24 (3%) |

| Emergency Room: | 20 (2%) |

| Military: | 10 (1%) |

| (1355 total practice settings) |

Sample sizes may slightly differ due to missing data

Respondents selected all that apply.

Reported use and Subjective Knowledge of Genetic Testing

Fifty-five percent of respondents indicated they ordered/referred for any genetic test in the past 12 months, with the majority of those who ordered tests (86.3%) reporting ordering tests for ≤10% of their patients. Of those who ordered genetic testing, 60.5% reported that they involved a genetic specialist (e.g., a genetic counselor, medical geneticist, psychiatric geneticist).

Eighty-seven percent of respondents agreed that it is their role to discuss genetic information regarding psychiatric conditions with their patients and their families. However, 45.2% of all respondents, and 36.1% of those who ordered genetic tests, rated their subjective knowledge of genetic testing practice guidelines in psychiatry as poor or very poor. Furthermore, 33.2% of all respondents reported their knowledge of how to integrate genetic testing into their practice as poor or very poor, and 26.7% rated their knowledge of genetic testing in psychiatry as poor or very poor. However, with respect to PGx testing, 66.7% of respondents rated their knowledge of how to integrate PGx testing into their practice as good or very good.

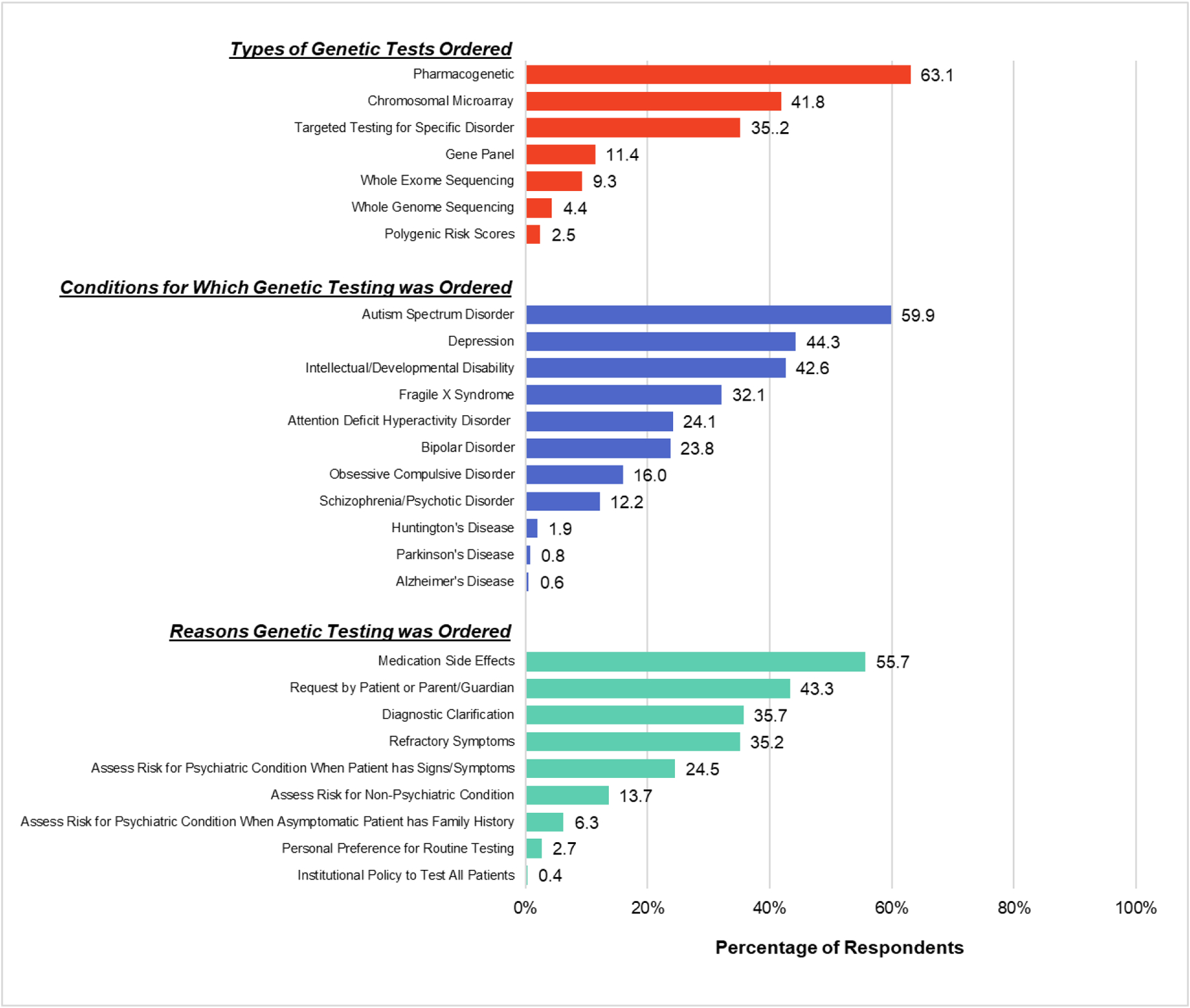

The types of genetic tests ordered, conditions for which genetic testing was ordered, and reasons genetic testing was ordered by the CAP that responded as having ordered a genetic test in the past 12 months are shown in Figure 2. The most ordered test was PGx testing, followed by chromosomal microarray.

Figure 2.

Respondents who ordered a genetic test in the past 12 months (n = 526) were asked what types of genetic tests they ordered, for which conditions they ordered the testing, and for which reasons they ordered the testing. The percentage of respondents choosing each option are shown. Please note that percentages will total over 100%, as respondents were able to select as many options that applied.

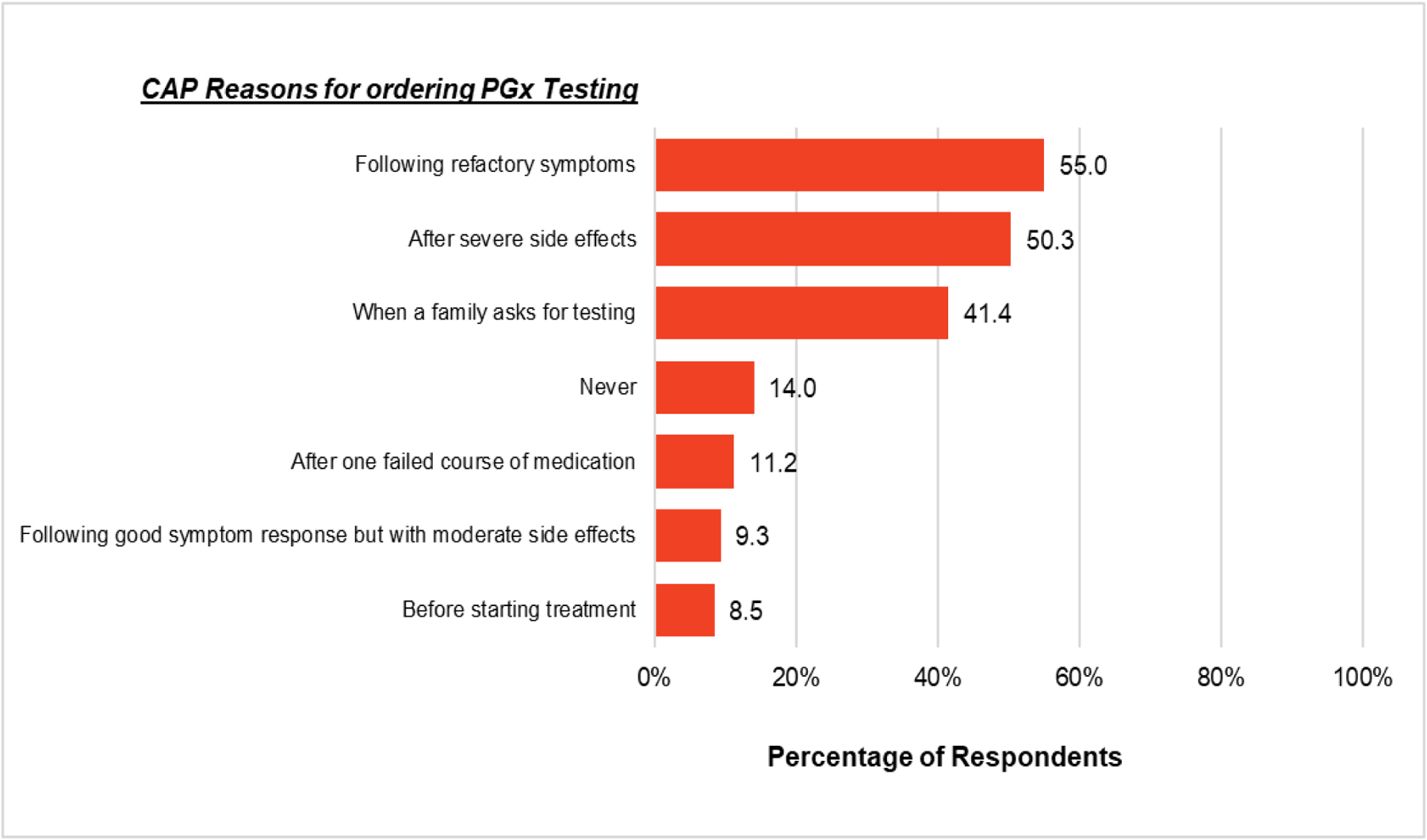

Regarding PGx testing, 32.2% of respondents reported ordering a PGx test in the prior 12 months. When asked when they would order a PGx test, the top three reasons were following refractory symptoms (55.0%), after severe side effects (50.3%), and when a family requested testing (41.4%; Figure 3). Fourteen percent of respondents reported they would never order PGx testing.

Figure 3.

Percentage of respondents (n = 958) who chose each option when asked when they would order a PGx test. Please note that percentages will total over 100%, as respondents were able to select as many options that applied.

Given the only clinical indication for the use of CMA in psychiatry are for the medical evaluation of those with ASD/IDD, we examined whether respondents reporting that they ordered testing for ASD/IDD were generally the ones ordering CMA testing. Of the 958 respondents, 220 (23.0%) reported requesting a CMA. Of those who requested a CMA, 96.8% endorsed ordering tests for ASD or IDD in the past 12 months, as compared to 18.4% of providers ordering tests for ASD or IDD but reporting that they did not request a CMA in the past 12 months. This difference was statistically significant (OR = 134.69, 95% CI = 62.02 – 292.51, p <.001). Overall, the majority of CAP have ordered genetic testing in the past 12 months and feel it is their role to discuss genetic testing, despite many reporting they felt their knowledge of testing was poor.

Perceived Utility

73.4% of respondents reported that PGx tests are currently at least slightly useful in CAP practice, and 93.3% believed PGx would be at least slightly useful in five years (X2(1) = 186.13, p <.001). We also identified a subgroup of respondents who reported ordering PGx testing despite identifying they felt PGx currently had no utility in child and adolescent psychiatry (7.1%). The most common reason these individuals reported ordering PGx tests was a family member requesting testing (68.2%).

In comparison, approximately 84% of respondents indicated that genetic testing was at least slightly useful for ASD (previously published in Soda et al., 2021), and 90.7% of respondents indicated that genetic testing was at least slightly useful for IDD. Among CAP who ordered a genetic test in the previous 12 months, 87.7% rated genetic testing for ASD as slightly to very useful, whereas 82.1% of those who did not order a genetic test rated genetic testing for ASD as slightly to very useful (X2 (1) = 5.77, p =.017). Among CAP who ordered a genetic test, 93.2% rated genetic testing for IDD as slightly to very useful, whereas 89.0% of those who did not order a genetic test rated genetic testing as slightly to very useful (X2 (1) = 10.90, p <.001). Overall, 76.3% of respondents felt that genetic testing for reasons other than testing for ASD/IDD was currently at least slightly useful. In contrast, 94.4% rated the utility of genetic testing for reasons other than ASD/IDD in five years would be slightly to very useful (X2(1) = 163.28, p <.001). Overall, our findings indicate that CAP feel that testing for reasons other than ASD/IDD, and PGX testing specifically, are currently useful and the utility of these tests will increase in the future; perceived utility was related to ordering patterns.

Predictors of Ordering a Genetic Test

Respondents’ perceived utility of genetic testing for conditions other than ASD/IDD was associated with an increased likelihood of ordering any genetic test (OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.21 – 2.24, p =.002). In addition to perceived utility, respondents were more likely to report ordering a genetic test when they reported greater knowledge about: genetic testing in psychiatry (OR = 2.20, 95% CI = 1.76 – 2.75, p <.001), genetic testing practice guidelines (OR = 1.83, 95% CI = 1.50 – 2.23, p <.001), and how to integrate genetic testing overall into their practice (OR = 2.35, 95% CI = 1.89 – 2.94, p <.001). CAP with ≤11 years of post-fellowship years in practice were 37% less likely to request any genetic test compared to CAP with >11 years of post-fellowship years in practice (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.47 – 0.85, p =.002).

Practice setting was associated with the frequency and self-reported knowledge with regard to genetic testing. Those who self-reported at least some component of having a private practice were more likely to order PGx tests compared to those who were not in any private practice (OR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.41 – 2.45, p <.001). This subgroup was also less likely to order diagnostic tests (OR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.38 – 0.69, p <.001). Those with at least some private practice setting did not significantly differ regarding self-reported knowledge about genetic testing F(1, 943) = 0.63, p =.427 or genetic testing practice guidelines in psychiatry F(1, 929) = 0.12, p =.725 compared to those who did not. In contrast, CAP at university medical centers were more likely to order diagnostic genetic testing defined as CMA, Fragile X, exome/genome, and other specific genetic tests (OR = 2.71, 95% CI = 1.97 – 3.73, p <.001). Practicing at a university medical center was also associated with greater self-reported knowledge of practice guidelines regarding psychiatric genetic testing F(1, 909) = 4.67, p = .031, and how to integrate them into practice F(1,924) = 5.10, p = .024.

Regarding PGx testing, respondents who reported higher levels of perceived utility of PGx were more likely to report ordering PGx testing in the last 12 months (OR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.47 – 2.16, p <.001). 62.8% of respondents reporting that they had been asked by a patient or family member to order a PGx test in the last year. Of the 32.3% who reported ordering a PGx test in the prior year, those who reported ordering a PGx test were significantly more likely to have been asked by a patient or family member to order PGx testing (49.2%) compared to respondents who did not receive a patient or family request for testing (6.8%), X2(1) = 172.86, p < .001. Overall, clinicians’ perceived utility of testing, their self-reported levels of knowledge surrounding testing and guidelines, and practice settings were associated with ordering patterns; for PGx specifically, patient or family request was also associated with ordering testing.

Understanding of PGx

Given the demonstrated common use of PGx in care at present, we further assessed the potential impact of PGx results on current patient care. Approximately 14% (13.8%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that a PGx test can predict the effectiveness of one antidepressant over another, indicating a problematic gap in knowledge concerning how to interpret PGx testing results, and 1.8% indicated that they did not know. Furthermore, 6.9% noted that they would likely or very likely change a medication, and 12.0% noted that they would change the dosage of the currently prescribed medication if PGx showed a patient is at an increased risk for serious side effects even if the patient has responded well to the medication without any significant side effects. Overall, these findings highlight some misunderstandings and misuses of PGx testing among a small portion of CAP.

4. Discussion

We report the largest survey of psychiatrists on the topic of genetic testing to date. Relative to a prior survey study conducted in 2011 (Salm et al., 2014), 1) Respondents continue to believe it is their role to discuss genetic findings in the context of psychiatric practice, 2) The fraction of psychiatrists reporting use of genetic testing has dramatically increased to a degree that it now constitutes a majority, and 3) A substantial fraction continue to report poor knowledge about these tests and how to incorporate them into practice.

Most respondents (54.9%) ordered a genetic test in the prior year, suggesting that genetic testing is now a common part of clinical care in child and adolescent psychiatry in the US 2011 survey found that 14% of US psychiatrists ordered genetic tests (Salm et al., 2014), suggesting a significant increase in this practice. More respondents reported ordering PGx testing than any other type of test (i.e., Fragile X, CMA, or WES), all of which currently have clear guidelines supporting their use in child and adolescent psychiatry (Hyman et al., 2020; Manickam et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2020; Volkmar et al., 2014), a status that PGx testing does not currently have (AACAP, 2020; Zubenko et al., 2018).

The most commonly reported type of PGx test were commercial combinatorial tests combined with clinical decision support tools for which the greatest evidence exists in adults with depression after a first failed medication (Bousman et al., 2019; Ontario Health, 2021; Zubenko et al., 2018), a result that has not been consistently replicated in a non-industry sponsored study (Oslin et al., 2022) or in children and adolescents (Vande Voort et al., 2022). These combinatorial tests include the specific genetic tests contained within some established guidelines, and their output often contradicts standard of care (Vande Voort et al., 2022).

Most respondents answered the questions about knowledge of PGx in a manner consistent with the strength of the evidence about the clinical utility of these tests in psychiatric practice. That 8% of respondents would change a currently effective medication that was not producing any side effects based on a PGx test result indicates that test usage may contribute to unnecessary and inappropriate medication changes.

In contrast to diagnostic testing in the context of ASD/IDD, wherein perceived utility was associated with the likelihood of test ordering, the perceived utility of PGx testing did not seem to influence clinicians’ reported ordering of PGx. CAP who reported ordering PGx testing were more likely to order these tests when the patients or families asked them to order this type of test or if they had a private practice location. This has implications for future attempts to influence the use of these tests; it may be the case that whereas clinician education may play a role in increasing the deployment of clinically indicated genetic testing for medical evaluation in the context of ASD/IDD, the same may not be the case for PGx testing.

Leaving aside the issue of whether or not PGx testing has sufficient evidence significantly impacting clinical outcomes for its implementation in the context of psychiatry, which remains widely debated (AACAP, 2020; Bousman et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2022; Fan & Bousman, 2020; Ramsey et al., 2021; Zubenko et al., 2018), clinicians should be ordering tests that they believe will positively impact clinical care, and not simply because a patient or family asked for it. Educational interventions that guide CAP on how to talk to patients about their reasons for not ordering certain tests may be indicated, as has been done with the prescription of unnecessary antibiotics in the primary care context (Altiner et al., 2012; Fleming-Dutra et al., 2016).

There may be factors other than patient requests to account for the association between private practice and increased likelihood of ordering PGx tests, such as fewer restrictions or less oversight from institution policies, on-site pharmacists, practice formularies, including third-party payers, towards PGx testing such that private-practice psychiatry may allow for CAP to order these tests at an increased frequency relative to other locations.

It should be noted that there are several scenarios in which it is clinically appropriate to order PGx tests. For example, the current FDA labeling for carbamazepine has a black box warning that states that patients with ancestry in genetically at-risk populations should be screened for the presence of HLA-B*15:02 prior to initiating treatment with carbamazepine. Patients testing positive for the allele should not be treated with carbamazepine unless the benefit clearly outweigh the risks (Carbamazepine, 2022). There is concern that those respondents who answered that they would never order a PGx test are either unaware of such labeling or alternatively have decided that they would never prescribe carbamazepine.

The difference between the implementation of genetic testing in the medical evaluation of ASD/IDD and PGx that may account for the higher rates of PGx being ordered in the absence of psychiatric professional organization’s inclusion of PGx as a part of guideline-concordant care include more active direct patient-engagement by PGx laboratories that provide this testing (Center for Devices and Radiological Health, 2019). Companies that offer PGx have greatly facilitated such testing by lowering the barriers towards ordering PGx on the part of physicians.

Several limitations should be considered. First, despite being the largest survey about genetics among CAP to date, our response rate was modest. Second, CAP were limited to those in the U.S. and results may not generalize to CAP in other countries.

The association between higher self-rated knowledge and guideline-concordant diagnostic genetic testing in respondents with academic affiliations may reflect differences in the dissemination of guidelines and implementation of practice change between such institutions relative to non-academic affiliated providers. The lag time between the release of a clinical guideline and its translation into clinical practice is commonly quoted to take 17 years (Morris et al., 2011). Given the relative recency of the AACAP practice parameters for ASD (Volkmar et al., 2014) and IDD (Siegel et al., 2020), the increased likelihood of having ordered genetic testing amongst those <10 years out of training is not entirely surprising. Board recertification testing for CAP was once every 10 years, and many trained community psychiatrists may have never had the training experience to order or interpret diagnostic genetic tests in the context of psychiatry. What is clear from the results of this survey is that guidelines are insufficient, and more education, collaboration with genetics healthcare professionals (i.e., genetic counselors(Austin et al., 2014)), as well as resources to appropriately implement genetic testing in psychiatry, are required.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers 3R00HG008689 and R01MH128676, and P50HD103555 for the use of the Clinical and Translational Core facilities.

Financial Disclosures (Conflicts of interest)

Dr. Soda receives grant support from NIH. Dr. Merner reports no financial relationships with commercial interests. Dr. Small receives grant support from NIH. Ms. Torgerson reports no financial relationships with commercial interests. Ms. Muñoz reports no financial relationships with commercial interests. Dr Austin receives support from BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services, and grant funding from Genome BC/Genome Canada, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. They have consulted for 23andme. Dr. Storch is a consultant for Biohaven and Brainsway. He receives grant support from NIH, International OCD Foundation, and Ream Foundation. He owns stock valued under $5000 in Nview. He receives book royalties from Elsevier, Springer, Oxford, Guilford, American Psychological Association, Lawrence Erlbaum, and Jessica Kingsley. Dr. Pereira receives grant support from NIH. Dr. Lázaro-Muñoz receives grant support from NIH.

Footnotes

Ethics Declaration

The Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine approved this study (protocol number H-46219). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability

De-identified survey data are available upon request from the corresponding author. Data will be made available to researchers whose proposed use of the data has been approved by the study team.

References

- AACAP, 2020. Clinical Use of Pharmacogenetic Tests in Prescribing Psychotropic Medications for Children and Adolescents. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/Policy_Statements/2020/Clinical-Use-Pharmacogenetic-Tests-Prescribing-Psychotropic-Medications-for-Children-Adolescents.aspx (accessed 29 September 2022)

- Abdelhakim M, McMurray E, Syed AR, Kafkas S, Kamau AA, Schofield PN, Hoehndorf R, 2020. DDIEM: Drug database for inborn errors of metabolism. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 15, 146. 10.1186/s13023-020-01428-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altiner A, Berner R, Diener A, Feldmeier G, Köchling A, Löffler C, Schröder H, Siegel A, Wollny A, Kern WV, 2012. Converting habits of antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections in German primary care—The cluster-randomized controlled CHANGE-2 trial. BMC Family Practice, 13, 124. 10.1186/1471-2296-13-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin J, Inglis A, Hadjipavlou G, 2014. Genetic Counseling for Common Psychiatric Disorders: An Opportunity for Interdisciplinary Collaboration. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(5), 584–585. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousman CA, Arandjelovic K, Mancuso SG, Eyre HA, Dunlop BW, 2019. Pharmacogenetic tests and depressive symptom remission: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacogenomics, 20(1), 37–47. 10.2217/pgs-2018-0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousman CA, Bengesser SA, Aitchison KJ, Amare AT, Aschauer H, Baune BT, Asl BB, Bishop JR, Burmeister M, Chaumette B, Chen L-S, Cordner ZA, Deckert J, Degenhardt F, DeLisi LE, Folkersen L, Kennedy JL, Klein TE, McClay JL, … Müller DJ, 2021. Review and Consensus on Pharmacogenomic Testing in Psychiatry. Pharmacopsychiatry, 54(1), 5–17. 10.1055/a-1288-1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousman CA, Dunlop BW, 2018. Genotype, phenotype, and medication recommendation agreement among commercial pharmacogenetic-based decision support tools. The Pharmacogenomics Journal, 18(5), Article 5. 10.1038/s41397-018-0027-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium Brainstorm, Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Walters RK, Bras J, Duncan L, Escott-Price V, Falcone GJ, Gormley P, Malik R, Patsopoulos NA, Ripke S, Wei Z, Yu D, Lee PH, Turley P, Grenier-Boley B, Chouraki V, … Murray R, 2018. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science (New York, N.Y.), 360(6395), eaap8757. 10.1126/science.aap8757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LC, Stanton JD, Bharthi K, Maruf AA, Müller DJ, Bousman CA, 2022. Pharmacogenomic Testing and Depressive Symptom Remission: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective, Controlled Clinical Trials. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 112(6), 1303–1317. 10.1002/cpt.2748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbamazepine: Extended-Release Capsules Rx Only, 2023. https://nctr-crs.fda.gov/fdalabel/services/spl/set-ids/ceb84aa4-2041-6e6e-e053-2995a90a0f24/spl-doc?hl=carbamazepine

- Center for Devices and Radiological Health, 2019. Inova Genomics Laboratory—577422—04/04/2019, FDA. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20201219080850/https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/inova-genomics-laboratory-577422-04042019 (accessed 29 November 2022).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2023. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/legislation/clia?redirect=/clia/ (accessed 12 April 2023)

- Dalkey N, Helmer O, 1963. An Experimental Application of the DELPHI Method to the Use of Experts. Management Science, 9(3), 458–467. 10.1287/mnsc.9.3.458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M, Bousman CA, 2020. Commercial Pharmacogenetic Tests in Psychiatry: Do they Facilitate the Implementation of Pharmacogenetic Dosing Guidelines? Pharmacopsychiatry, 53(4), 174–178. 10.1055/a-0863-4692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA, 2021. Laws Enforced by FDA. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/laws-enforced-fda (accessed 28 November 2022).

- FDA, 2023. Nucleic Acid Based Tests. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/in-vitro-diagnostics/nucleic-acid-based-tests (accessed 10 April 2023).

- Fleming-Dutra KE, Mangione-Smith R, Hicks LA, 2016. How to Prescribe Fewer Unnecessary Antibiotics: Talking Points That Work with Patients and Their Families. American Family Physician, 94(3), 200–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris HK, Sideridis GD, Barbaresi WJ, Harstad E, 2020. Pathogenic Yield of Genetic Testing in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 146(4), e20193211. 10.1542/peds.2019-3211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JK, Bishop JR, Sangkuhl K, Müller DJ, Ji Y, Leckband SG, Leeder JS, Graham RL, Chiulli DL, LLerena A, Skaar TC, Scott SA, Stingl JC, Klein TE, Caudle KE, Gaedigk A, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium., 2015.Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotypes and Dosing of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 98(2), 127–134. 10.1002/cpt.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JK, Sangkuhl K, Swen JJ, Ellingrod VL, Müller DJ, Shimoda K, Bishop JR, Kharasch ED, Skaar TC, Gaedigk A, Dunnenberger HM, Klein TE, Caudle KE, Stingl JC, 2017. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline (CPIC) for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of tricyclic antidepressants: 2016 update. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 102(1), 37–44. 10.1002/cpt.597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM, COUNCIL ON CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES, S. O. D. A. B. P., Kuo DZ, Apkon S, Davidson LF, Ellerbeck KA, Foster JEA, Noritz GH, Leppert MO, Saunders BS, Stille C, Yin L, Weitzman CC, Childers DO Jr, Levine JM, Peralta-Carcelen AM, Poon JK, … Bridgemohan C, 2020. Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 145(1), e20193447. 10.1542/peds.2019-3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Society of Psychiatric Genetics, 2019. Genetic Testing Statement. https://ispg.net/genetic-testing-statement/ (accessed 29 November 2022)

- Leckband SG, Kelsoe JR, Dunnenberger HM, George AL, Tran E, Berger R, Müller DJ, Whirl-Carrillo M, Caudle KE, Pirmohamed M, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium., 2013. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for HLA-B genotype and carbamazepine dosing. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 94(3), 324–328. 10.1038/clpt.2013.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Qiao J, Shao Z, Wang T, Huang S, Zeng P, 2021. A comprehensive gene-centric pleiotropic association analysis for 14 psychiatric disorders with GWAS summary statistics. BMC Medicine, 19, 314. 10.1186/s12916-021-02186-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manickam K, McClain MR, Demmer LA, Biswas S, Kearney HM, Malinowski J, Massingham LJ, Miller D, Yu TW, Hisama FM, ACMG Board of Directors., 2021. Exome and genome sequencing for pediatric patients with congenital anomalies or intellectual disability: An evidence-based clinical guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 23(11), 2029–2037. 10.1038/s41436-021-01242-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNemar Q, 1947. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika, 12(2), 153–157. 10.1007/BF02295996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-De-Luca D, Kavanaugh BC, Best CR, Sheinkopf SJ, Phornphutkul C, Morrow EM, 2020. Clinical Genetic Testing in Autism Spectrum Disorder in a Large Community-Based Population Sample. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(9), 979–981. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J, 2011. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104(12), 510–520. 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller DJ (2020). Pharmacogenetics in Psychiatry. Pharmacopsychiatry, 53(4), 153–154. 10.1055/a-1212-1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray GK, Lin T, Austin J, McGrath JJ, Hickie IB, Wray NR, 2021. Could Polygenic Risk Scores Be Useful in Psychiatry?: A Review. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(2), 210–219. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Ontario, 2021. Multi-gene Pharmacogenomic Testing That Includes Decision-Support Tools to Guide Medication Selection for Major Depression: A Health Technology Assessment. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, 21(13), 1–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Shih M-C, Ingram EP, Wray LO, Chapman SR, Kranzler HR, Gelernter J, Pyne JM, Stone A, DuVall SL, Lehmann LS, Thase ME, PRIME Care Research Group., 2022. Effect of Pharmacogenomic Testing for Drug-Gene Interactions on Medication Selection and Remission of Symptoms in Major Depressive Disorder: The PRIME Care Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 328(2), 151–161. 10.1001/jama.2022.9805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira S, Muñoz KA, Small BJ, Soda T, Torgerson LN, Sanchez CE, Austin J, Storch EA, Lázaro-Muñoz G, 2022. Psychiatric polygenic risk scores: Child and adolescent psychiatrists’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics: The Official Publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics, 189(7–8), 293–302. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PharmGKB, 2019. Annotation of FDA Label for aripiprazole and CYP2D6. https://www.pharmgkb.org/labelAnnotation/PA166104839 (accessed 28 September 2022).

- PharmGKB, 2020. Annotation of FDA Label for citalopram and CYP2C19. https://www.pharmgkb.org/labelAnnotation/PA166104852 (accessed 28 September 2022).

- Ramsey LB, Namerow LB, Bishop JR, Hicks JK, Bousman C, Croarkin PE, Mathews CA, Van Driest SL, Strawn JR, 2021. Thoughtful Clinical Use of Pharmacogenetics in Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(6), 660–664. 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salm M, Abbate K, Appelbaum P, Ottman R, Chung W, Marder K, Leu C-S, Alcalay R, Goldman J, Curtis AM, Leech C, Taber KJ, Klitzman R, 2014. Use of genetic tests among neurologists and psychiatrists: Knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and needs for training. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 23(2), 156–163. 10.1007/s10897-013-9624-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, McGuire K, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Stratigos K, King B, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI), Bellonci C, Hayek M, Keable H, Rockhill C, Bukstein OG, Walter HJ, 2020. Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Intellectual Disability (Intellectual Developmental Disorder). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(4), 468–496. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, McGuire K, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Stratigos K, King B, Bellonci C, Hayek M, Keable H, Rockhill C, Bukstein OG, Walter HJ, 2020. Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Intellectual Disability (Intellectual Developmental Disorder). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(4), 468–496. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soda T, Pereira S, Small BJ, Torgerson LN, Muñoz KA, Austin J, Storch EA, Lázaro-Muñoz G, 2021. Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists’ Perceptions of Utility and Self-rated Knowledge of Genetic Testing Predict Usage for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(6), 657–660. 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford CF, Sanchez-Lara PA, 2022. Impact of Genetic and Genomic Testing on the Clinical Management of Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Genes, 13(4), 585. 10.3390/genes13040585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Voort JL, Orth SS, Shekunov J, Romanowicz M, Geske JR, Ward JA, Leibman NI, Frye MA, Croarkin PE, 2022. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Combinatorial Pharmacogenetics Testing in Adolescent Depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(1), 46–55. 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar F, Siegel M, Woodbury-Smith M, King B, McCracken J, State M, 2014. Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(2), 237–257. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J-C, Radcliff J, Coe SJ, Mahon LW, 2019. Effects of platforms, size filter cutoffs, and targeted regions of cytogenomic microarray on detection of copy number variants and uniparental disomy in prenatal diagnosis: Results from 5026 pregnancies. Prenatal Diagnosis, 39(3), 137–156. 10.1002/pd.5375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubenko GS, Sommer BR, Cohen BM, 2018. On the Marketing and Use of Pharmacogenetic Tests for Psychiatric Treatment. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(8), 769–770. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified survey data are available upon request from the corresponding author. Data will be made available to researchers whose proposed use of the data has been approved by the study team.