Abstract

Objective:

Opioid overdose is a leading cause of maternal mortality, yet limited attention has been given to the consequences of opioid use disorder (OUD) in the year following delivery when most drug-related deaths occur. This article provides an overview of the literature on OUD and overdose in the first year postpartum and provides recommendations to advance maternal opioid research.

Approach:

A rapid scoping review of peer-reviewed research (2010–2021) on OUD and overdose in the year following delivery was conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases. This article discusses existing research, remaining knowledge gaps, and methodological considerations needed.

Results:

Seven studies were included. Medication for OUD (MOUD) was the only identified factor associated with a reduction in overdose rates. Key literature gaps include the role of mental health disorders and co-occurring substance use, as well as interpersonal, social, and environmental contexts that may contribute to postpartum opioid problems and overdose.

Conclusions:

There remains a limited understanding of why women in the first year postpartum are particularly vulnerable to opioid overdose. Recommendations include: 1) identifying subgroups of women with OUD at highest risk for postpartum overdose, 2) assessing opioid use, overdose, and risks throughout the first year postpartum, 3) evaluating the effect of co-occurring physical and mental health conditions and substance use disorders, 4) investigating the social and contextual determinants of opioid use and overdose after delivery, 5) increasing MOUD retention and treatment engagement postpartum, and 6) utilizing rigorous and multidisciplinary research methods to understand and prevent postpartum overdose.

Keywords: Opioid Use Disorder, Overdose, Postpartum, Substance Use, Pregnancy, Medication for OUD

Introduction

Since 1999, the opioid mortality rate among women has increased more than 500% (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020) and opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy has quadrupled (Haight et al., 2018). As such, drug overdose has become a leading cause of death among pregnant and postpartum women (Mangla et al., 2019; Metz et al., 2016; Smid et al., 2019). An evaluation of the US National Vital Statistics System found that pregnancy-associated deaths involving opioids more than doubled from a rate of 1.3 to 4.2 per 100,000 life births from 2007 to 2016, with opioids alone accounting for 10% of pregnancy-associated deaths (Gemmill et al., 2019). Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs) have also found that maternal drug-related deaths most often occur during the first year postpartum, rather than during pregnancy. In Colorado, over 90% of pregnancy-related deaths due to drug use occurred after delivery (Metz et al., 2016) and in Utah, 80% of drug-related deaths occurred between 2–12 months postpartum (Smid et al., 2019). Moreover, MMRCs and research consistently identify opioids as the most prevalent drug involved in maternal overdose deaths (Mangla et al., 2019; Metz et al., 2016; Smid et al., 2019).

Despite the prevalence of opioid-related mortality within the first year postpartum, factors that may increase susceptibility to or protect against opioid problems and overdose after delivery are not well understood. For instance, among women with OUD, the complex demands of parenting may intersect with maternal and infant health conditions, legal and custody issues, intimate partner violence, limited healthcare and social resources, and systemic community conditions that may increase the risk of opioid problems (Mair et al., 2018; Patton et al., 2019; Rowe et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2020; Stone & Rothman, 2019). Moreover, women with OUD are less likely to access and utilize healthcare and drug treatment services (Patton et al., 2019; Wilder et al., 2015), including Medications for OUD (MOUD), in the postpartum period compared to during pregnancy. Thus, investigating and addressing the risks and contexts that contribute to overdose vulnerability for postpartum women with OUD is warranted. Thus, the objective of this rapid scoping review is to provide an overview of scientific literature on OUD and overdose among postpartum women. Using the findings from this review, we highlight critical knowledge gaps and methodological considerations needed for future research aimed at reducing maternal opioid-related morbidity and mortality.

Methods

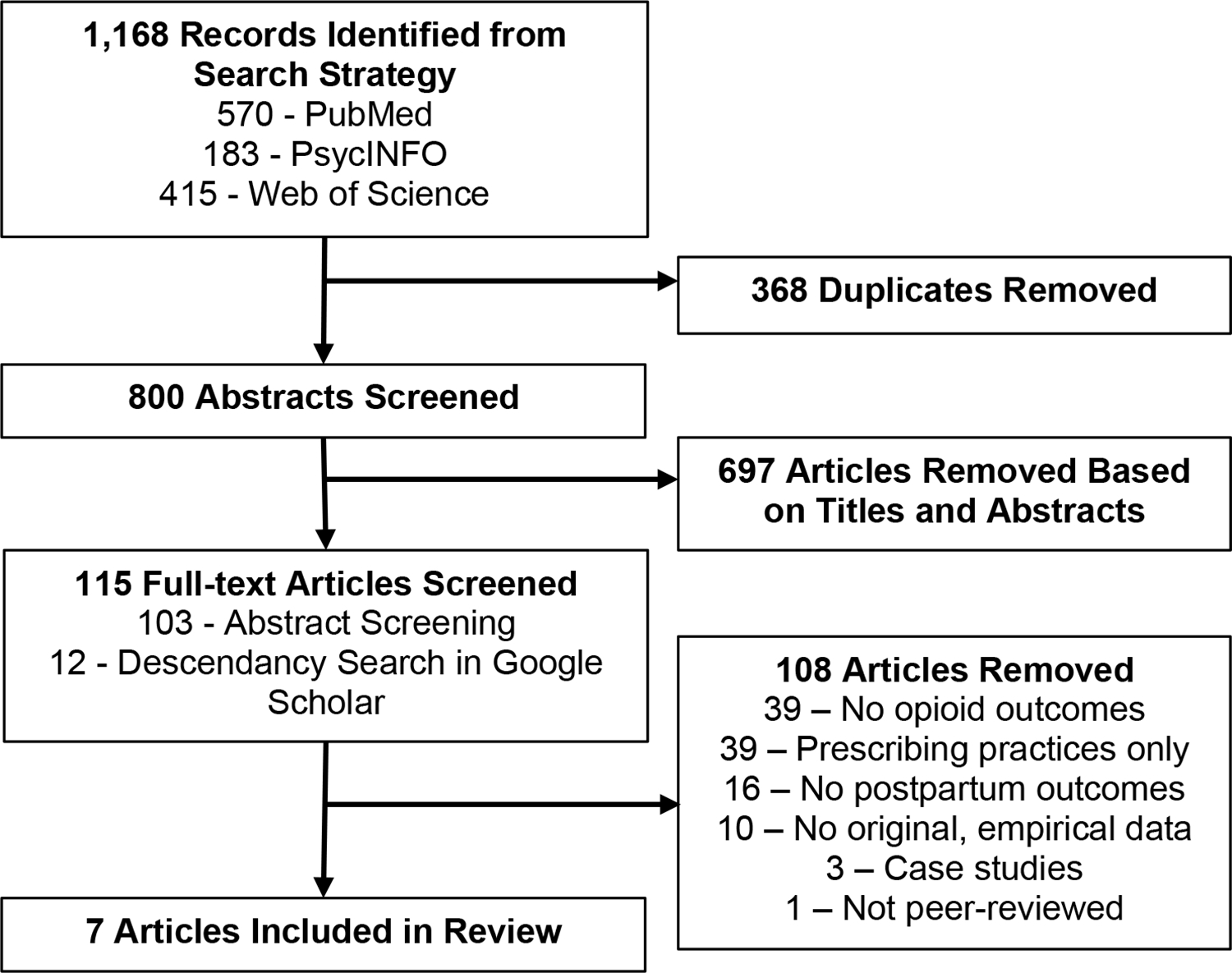

We conducted a rapid scoping review of factors associated with OUD and opioid overdose in the year following delivery. Unlike systematic reviews that focus on a specific question, a scoping review aims to provide a broad overview of the existing literature and identify gaps in knowledge (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Munn et al., 2018). Using a rapid review methodology (Ganann et al., 2010), we retrieved original and peer-reviewed research from PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases that were published in English from 2010 (corresponding to the beginning of second wave of opioid crisis with increases in heroin deaths) to the time of the search in January 2021. The search strategy was developed and tested in PubMed and then adapted for PsycINFO and Web of Science databases. The search terms included combined terms relevant to opioid use (e.g., “opioid*”, “opiate*”, “heroin”, “overdose”, “fentanyl”) and the postpartum period (e.g., “postpartum”, “postnatal”, “maternal”, “following/after delivery”). After removing duplicates, abstracts, followed by full-text documents, were screened for eligibility. Among included articles, a descendancy search (searching forwards) in Google Scholar was conducted to identify recent articles that cited the eligible articles. Full-text documents of newly identified articles were screened. Articles were included if they met the following criteria: 1) provided empirical data; 2) contained human subjects; 3) examined opioid use or related opioid outcomes as the dependent variable; and 4) examined maternal opioid outcomes up to 12-months post-delivery. In this review, we excluded articles on postpartum pain management or physician opioid prescribing, which has been investigated elsewhere (McKinnish et al., 2021; Peahl et al., 2019).

Results and Discussion

The search strategy resulted in 800 unique abstracts to be screened (Figure 1). From these, seven eligible articles were included in our review (Table 1; Cochran et al., 2018; Ellis et al., 2019; Guille et al., 2020; Kern-Goldberger et al., 2020; Nielsen et al., 2019; Schiff et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2019). With only seven studies included, all of which were published in 2018 or later and based in the United States, this review emphasizes the highly limited understanding of OUD and overdose following delivery.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram: Search Strategy Results and Article Exclusion

Table 1.

Summary of Studies on Opioid Use and Overdose in the Year Following Delivery (n=7)

| Observational Studies | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Author (Year) | Study Design & Time Period | Sample | Time Measured Post-delivery | Opioid Outcome | Relevant Independent Variables Assessed | Results |

|

| ||||||

| Ellis et al. (2019) | Retrospective chart review of methadone treatment clinic from 2010–2017 | Pregnant women enrolled in methadone treatment during pregnancy (n=72) | 30 days and 90 days | Opioid misuse, measured via toxicology | Age, race, injection drug use history, delivery type, methadone dose at delivery, days in treatment during pregnancy, opioid prescription at delivery discharge | Among the sample, 38.9% had opioid misuse within 30 days of delivery and 52.8% within 90 days. Opioid misuse at 30 days was significantly associated with days in treatment during pregnancy (p=.008), having a C-section (p=.045), and having an opioid prescription at discharge (p=.028). Age, race, IDU history, and methadone dose at delivery were not significantly associated with 30-day opioid misuse, and no variables were associated with misuse at 90 days. In adjusted models, days in treatment during pregnancy was negatively associated with opioid misuse at 30 days postpartum (b=-0.01, p=.011). |

| Kern-Goldberger et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional study of Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) from 1998–2014 | Women aged 15–54 (n=1,063,845) | Not reported; used ICD-9-CM codes to identify postpartum | OUD-related hospitalization; Opioid overdose hospitalization | Age, race, health insurance type, residential ZIP-code income quartile, hospital teaching status, hospital urbanicity, hospital bed size, region of USA | From 1998–2014, postpartum OUD hospitalizations increased from 0.8% to 2.1% and postpartum overdose-specific admissions increased from 18.8 per 100,000 admissions to 65.2. In adjusted models, risk of postpartum OUD-related admissions was significantly higher among women aged 30–34 vs. aged 25–29 (aRR=1.20, p<.001), those with Medicaid vs. private insurance (aRR=6.56, p<.001), and those at an urban vs. rural hospital (aRR=1.66, p<.001). Postpartum OUD admissions were significantly lower among women aged 15–17 (aRR=0.09, p<.001) and 18–24 (aRR=0.62, p<.001) vs. 25–29, those with residential ZIP-code incomes above the first quartile (p<.001), and those in all other race/ethnicity categories compared to whites (aRR=0.12–0.73, p<.001). Hospital bed size and teaching status were not associated with postpartum OUD admissions. |

| Nielsen et al. (2019) | Retrospective cohort study of a statewide-linked administrative database from 2011–2015 | Women who had a delivery of a live born neonate between 2012–2014 (n=174,517 deliveries) | 12 months | Fatal and nonfatal opioid overdose | Age, race, education, marital status, health insurance type, OUD diagnosis, homeless in year before delivery, incarceration in year before delivery, depression, anxiety, number of ED visits in year before delivery, opioid treatment enrollment, MOUD at delivery, Opioid prescriptions during pregnancy, nonfatal overdose in year before delivery, delivery type, infant NAS diagnosis, infant low birth weight, infant receipt of breastmilk before discharge, prenatal care | There were 189 women who experienced at least one overdose in the year following delivery (11 per 10,000 deliveries). Of the overdoses, 93% were nonfatal and 58% occurred 7–12 months post-delivery. OUD diagnosis was associated with a substantially higher overdose rate compared to those without OUD (349.3 vs. 5.9 per 10,000 deliveries). In adjusted analyses among women with OUD, women who had a nonfatal overdose in the year before delivery (aOR=2.48, 95% CI=1.19–5.17), 3 or more ED visits in the year before delivery (aOR=2.28, 95% CI=1.8–3.75), an anxiety diagnosis (aOR=1.92, 95% CI=1.16–3.17), and an infant with NAS diagnosis (aOR=2.03, 95% CI=1.26–3.27) were at increased odds of an overdose in year following delivery. Demographics, homelessness, incarceration, depression, other opioid and drug treatment variables, delivery type and prenatal care, and other infant conditions were not significantly associated with opioid overdose among women with OUD. |

| Schiff et al. (2018) | Retrospective cohort study of a statewide-linked administrative database from 2011–2015 | Women with OUD who had a delivery of a live born neonate between 2012–2014 (n=4,154 deliveries) | 12 months | Fatal and nonfatal opioid overdose | Receipt of MOUD (methadone or buprenorphine), 3-month time interval from 0–12 months postpartum | Overdose rates were at the highest from 10–12 months postpartum at 12.4 per 100,000 person-days (95% CI=9.1–16.4), compared to 9.7 (95% CI=6.9–13.3) the year before conception and 3.3 (95% CI= 1.6–6.1) in the third trimester. While higher, differences in overdose rates 7–12 months postpartum compared to pre-conception were not statistically significant, and only significantly differed from the third trimester. Compared to those who did not receive MOUD, those with MOUD had a lower overdose rate at each 3-month postpartum interval but was only statistically significant at 4–6 months postpartum (1.3, 95% CI=0.2–4.7 vs. 10.7, 95% CI=6.8–15.9). |

| Wen et al. (2019) | Retrospective study of Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) linked per year from 2010–2014 | Women aged 15–54 who had a hospital delivery record between Jan. to Oct. of each year from 2010–2014 (n=15,701,149 deliveries) | 60 days | OUD-related (primary diagnosis) hospitalization | Age, health insurance type, OUD diagnosis at delivery, delivery type, delivery postpartum hemorrhage, pregestational and gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, chronic hypertension, residential ZIP-code income quartile, hospital teaching status and urbanicity, hospital bed size | There were 1,039 postpartum readmissions for OUD. Those with an OUD diagnosis at delivery had over a 100-fold increased risk of a postpartum OUD readmission than those without an OUD diagnosis (RR=109.61, 95% CI=96.2–124.9). In adjusted models where OUD diagnosis was controlled, OUD-related readmissions were positively associated with maternal ages 20–24 vs. 25–29 (aRR=1.16, 95% CI=1.00–1.36), having Medicaid (aRR=7.57, 95% CI=5.06–11.31) or Medicare (aRR=4.41, 95% CI=3.64–5.34) vs. private insurance, and having a C-section (aRR=1.28, 95% CI=1.12–1.45). Women aged 15–19 vs. 25–29 (aRR=0.66, 95% CI=0.50–0.87) and who experienced gestational diabetes (aRR=0.29, 95% CI=0.17–0.48) or hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (aRR=0.63, 95% CI=.48–0.83) were at lower risk of OUD readmissions. OUD readmissions were not significantly associated with postpartum hemorrhage, pregestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, residential ZIP-code income quartiles, hospital teaching status, or hospital bed size. |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention Evaluations | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Author (Year) | Study Design & Time Period | Sample | Time Measured Post-delivery | Opioid Outcome | Intervention Description | Results |

|

| ||||||

| Cochran et al. (2018) | One-group repeated measures from 2015–2016 | Pregnant women with OUD diagnosis within two weeks of buprenorphine induction (n=21) | 8 weeks | Self-reported abstinence from illicit opioid abuse | Patient Navigator (PN): ten prenatal and four postnatal sessions with a trained PN to address barriers to healthcare and drug treatment | Past 30-day abstinence from illicit opioid use increased from 68% at baseline (during pregnancy before 25 weeks gestation) to 96% at 8 weeks postpartum. After adjusting for treatment exposure, abstinence from illicit opioids increased over time (b=0.15, p<.001). |

| Guille et al. (2020) | Nonrandomized control trial from 2017–2018 | Pregnant women seeking treatment for OUD in obstetrics office (n=98) | 6–8 weeks | Opioid toxicology | Telemedicine: Standardized OUD treatment during pregnancy delivered via telemedicine; compared to patients where treatment was delivered with office-based in-person care | At 6–8 weeks postpartum, 9.8% and 20.8% of telemedicine and in-person patients, respectively, had a positive opioid toxicology (p=.24). After propensity score and covariate adjustment, patients with treatment delivered via telemedicine and in-person did not differ on postpartum opioid screens (p=.66). |

Methodological Considerations

Study Designs and Data

Study designs and data sources impact the research questions that can be asked and answered. Of the reviewed articles, five presented observational studies (Ellis et al., 2019; Kern-Goldberger et al., 2020; Nielsen et al., 2019; Schiff et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2019), while two evaluated a pilot intervention or clinical program (Cochran et al., 2018; Guille et al., 2020). Among observational studies, four used retrospective cohort designs (Ellis et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2019; Schiff et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2019) while one was cross-sectional (Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019). The intervention evaluations used a one-group repeated-measures (Cochran et al., 2018) and a nonrandomized clinical trial design (Guille et al., 2020).

A strength of the observational studies is the use of retrospective cohort designs, allowing timely assessments of longitudinal outcomes (Ellis et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2019; Schiff et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2019). Using a range of samples and datasets, including some large nationwide inpatient datasets, the retrospective studies included in our review were able to provide an incidence of opioid use or overdose in their samples and assess a range of factors associated with these outcomes. However, due to their retrospective approach, these studies were limited in their ability to measure exposures and confounders not included in their existing dataset (Klebanoff & Snowden, 2018). In contrast, prospective studies aimed at understanding opioid use and overdose postpartum may be beneficial to this research area in being better able to capture changes in risks, trends, and contexts over time. Moreover, the inclusion of qualitative and mixed-methods data (all included articles were quantitative) may also be helpful in contextualizing existing research and provide a deeper understanding of the interpersonal and social circumstances that contribute to opioid problems and overdose events. Lastly, while also not found in this review, ecological studies can identify geographic patterns and variation in OUD and overdose patterns and inform the distribution of community resources that may be needed in the postpartum period.

Administrative and medical record data were used in six of the seven studies (Ellis et al., 2019; Guille et al., 2020; Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2019; Schiff et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2019). Although these data provide one of the few ways to assess maternal drug outcomes, they come with important limitations. Administrative data may be particularly susceptible to misclassification and reporting bias because they contain data only on healthcare or system encounters (Sillanaukee et al., 2002), resulting in an undercount of the prevalence of OUD and overdose events. They also include few individual (e.g., socioeconomic status, addiction severity) or community (e.g., local drug supply, employment) characteristics that may contribute to opioid outcomes. This field may benefit from rigorous community-based studies and methods of collecting data from this often hard-to-reach population.

Study Populations

The characteristics of a study’s sample is vital to extrapolating information about the target population and for whom research results can be generalized. In our review, three studies examined outcomes among all women with a hospital delivery (Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2019), while four focused on women with OUD diagnoses or seeking drug treatment (Cochran et al., 2018; Ellis et al., 2019; Guille et al., 2020; Schiff et al., 2018). Studies that assessed the general population of postpartum women found that opioid-related hospitalizations and overdoses were rare (Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2019). These studies aimed to identify high-risk groups, finding that those with OUD diagnoses during pregnancy or at delivery are at highest risk of opioid problems post-delivery. Only Nielsen et al. (2019) stratified their analyses examining those with and without an OUD diagnosis separately, finding drastically different overdose incidences in the year following delivery (349 vs. 6 per 10,000 deliveries). Future research should prioritize identifying factors that contribute to adverse outcomes among already high-risk populations, such as those with OUD diagnoses. Moreover, research should identify subgroups of women with OUD, such as those with severe mental illness (van Draanen et al., 2022) or who have interrupted MOUD access (e.g., incarceration; Mital et al., 2020), who may be particularly vulnerable to overdose in the first year postpartum.

Operationalizing the Postpartum Period

A fundamental yet consistent issue in this area is the variability in definitions of the postpartum period and the differing ways it is operationalized in research. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018) describes the postpartum period as the “fourth trimester”, recommending care be an ongoing and individualized process with contact with a provider within three weeks of delivery, ongoing care as needed, and concluding with a comprehensive visit by 12 weeks postpartum. Clinically, this corresponds with a one-time, in-person postpartum visit which has historically occurred between 6 and 8 weeks postpartum, when most of the physiological changes related to pregnancy have resolved. Comparatively, Medicaid, the primary insurance for pregnancy care for women with OUD in the U.S. (Jarlenski et al., 2020a), is mandated to provide coverage for uninsured women through the end of the month that includes the 60th day post-delivery. Moreover, MMRCs examine maternal deaths within one year of delivery (Smid et al., 2020). In our review, one study measured outcomes at 30 and 90 days post-delivery (Ellis et al., 2019), three between six and eight weeks post-delivery (Cochran et al., 2018; Guille et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2019), and two up to one year post-delivery (Nielsen et al., 2019; Schiff et al., 2018). The remaining study did not assess a time indicator but used ICD-9-CM postpartum codes (specific time frame or code(s) were not provided) to identify postpartum hospitalizations (Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019).

The duration of the postpartum period and how this period is operationalized in research is a particularly salient question as three studies in our review found that the incidence of opioid use and overdose increased further from delivery (Ellis et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2019; Schiff et al., 2018). In the two studies that measured outcomes up to 12-months post-delivery, the highest overdose rates occurred 7–12 months postpartum, with more than 60% occurring in this period (Nielsen et al., 2019; Schiff et al., 2018). These findings are concerning given that most overdoses occur after the clinical provision of postpartum care and pregnancy-related Medicaid eligibility windows. While these studies do not clinically define the postpartum period as such, the inconsistent operationalization and measurement of this period presents research challenges. Given the dynamic nature of how healthcare access, social stressors, and relationships change throughout the first year postpartum, research may need to prioritize the time beyond the traditional 6–8 week postpartum period or substantial maternal outcomes and risks may be missed or underestimated. In fact, Smid et al. (2020) recommend providing frequent follow-up care up to women with substance use disorders (SUDs) throughout the first year postpartum. Research may benefit from using a similar, longer-term approach in operationalizing this period. Utilizing a life course perspective, which considers factors across the life span and viewing reproductive health and substance use in a continuity (Mishra et al. 2010), may also be beneficial in measuring and identifying changing risks and contexts.

Subject-Specific Research Areas

Sociodemographics and Social Conditions

Four studies examined the relationship between individual-level sociodemographic factors and opioid use in the first year postpartum (Ellis et al., 2019; Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2019). These studies generally found that women in their 20’s, white women, and women on Medicaid had the highest rates of opioid-related outcomes in the year after delivery. However, there were important limitations. Differences between racial/ethnic groups remain understudied, with inconsistent findings across studies. Only one study had sufficient power to compare specific racial/ethnic groups (Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019), beyond comparing white versus non-white women. As Black people and other people of color experience disparate rates of maternal morbidity and substantial barriers to postpartum care (Collier & Molina, 2019; Thiel de Bocanegra et al., 2017), research is needed on the unique opioid-related patterns and risks in racial/ethnic minority women.

No studies assessed the association of individual-level socioeconomic status with postpartum opioid use. While not directly comparable, health insurance type (Medicaid versus employer-based or private insurance) was often used as a proxy for income (Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2019; Schiff et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2019). However, no study assessed the continuity of health insurance coverage, including Medicaid eligibility or enrollment after 60 days postpartum. Moreover, only one study examined the relationship of social conditions, such as homelessness and incarceration (Nielsen et al., 2019), on outcomes. Inconsistent with research findings outside the postpartum period (Mital et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2019), Nielsen et al. (2019) found that neither homelessness nor past-year incarceration was independently associated with overdose within 12-months of delivery among women with OUD. However, possibly due to misclassification, incarceration was associated with four times the adjusted odds of overdose in women without an OUD diagnosis. These findings highlight the need to further consider the complex burden of social conditions faced by postpartum women when screening for and addressing OUD and overdose.

Co-morbid Health Conditions and Co-occurring Substance Use

While pregnant women with OUD disproportionately experience severe maternal morbidity (Jarlenski et al., 2020a), adverse obstetric outcomes (Maeda et al., 2014), and a range of physical and mental health conditions (Shen et al., 2020), few reviewed studies investigated the role of co-occurring conditions on post-delivery opioid outcomes. Only one study examined pregnancy-related conditions, including hypertensive diseases and gestational diabetes, finding a lower associated risk for opioid-related hospitalizations within two months of delivery among a general sample of postpartum women when adjusting for OUD diagnosis (Wen et al., 2019). This study also found that among women with OUD, those that experienced hypertensive diseases and gestational diabetes had increased odds of all-cause admissions, suggesting these conditions may be related to increased risk of postpartum morbidity but not necessarily drug use or overdose during this period. Moreover, no other physical health conditions, including HIV or Hepatitis C, were examined in these studies. While infections associated with substance use may not directly cause overdose, they may be indicators for high-risk behaviors and environments, such as unsafe injection drug practices or risky sexual behaviors, that may play an important role in the risk of postpartum overdose.

Only one study considered mental health conditions, finding that both anxiety and depression diagnoses at delivery were associated with a higher incidence of overdose within one year compared to women without these diagnoses (Nielsen et al., 2019). Postpartum depression has also been linked to increased postpartum substance use and nonadherence to drug treatment (Chapman & Wu, 2013), but was not specifically explored in any reviewed studies, nor any other severe mental health conditions. While this review finds a limited understanding of mental health and opioid outcomes in the postpartum period overall, the link between mental health and OUD is well established (van Draanen et al., 2022). Mental health conditions have been associated with drug use initiation and maintenance, overdose, limited access and utilization of treatment, risky drug-related behaviors, and a lack of social support (Birtel et al., 2017; Fleming et al., 2008; Lai et al., 2015; Priester et al., 2016; van Draanen et al., 2022). Further research is needed to understand the effects of mental health conditions on drug outcomes among women with OUD and how these co-occurring conditions may change or become exacerbated in the first year postpartum.

No studies in our review measured polysubstance use despite estimates that approximately 65% of pregnant women with OUD have at least one other co-occurring SUD (Jarlenski et al., 2020b). Data from a MMRC in Utah also found that more than 80% of all drug-related maternal deaths during pregnancy and up to 12-months post-delivery involved multiple substances (Smid et al., 2019). Thus, understanding specific substance use patterns during pregnancy and postpartum may be relevant in identifying those at increased risk of deleterious outcomes post-delivery.

Medication for OUD (MOUD)

MOUD (i.e., buprenorphine or methadone) is the recommended treatment for OUD among pregnant women and has been associated with a lower risk of preterm birth and maternal overdose during pregnancy (Krans et al., 2021). In our review, MOUD was the only identified factor associated with a decreased overdose risk in the first year postpartum. Schiff et al. (2018) found that women on MOUD had consistently lower rates of overdose at each three-month interval throughout the first year postpartum compared to women not receiving MOUD during that interval, although only differences in rates from 4–6 months post-delivery were statistically significant. Two other studies examined MOUD treatment at delivery, neither finding a significant association with opioid outcomes at 30 or 90 days (Ellis et al., 2019) and within 12-months (Nielsen et al., 2019). While promising, further research is needed to evaluate the effect of MOUD throughout the first year postpartum, including differences in MOUD type, uptake and adherence, and long-term retention. Postpartum MOUD retention is a critical issue as approximately half of women discontinue MOUD within six months of delivery (Wilder et al., 2015) and may contribute to increased overdose rates 6–12 months post-delivery. While we did not examine MOUD continuation as an outcome in this review, research has identified a shorter duration of MOUD use during pregnancy, incarceration, non-white race, having an opioid prescription, and using other substances as associated with MOUD discontinuation post-delivery, while receiving an anti-depressant prescription is associated with increased retention (O’Connor et al., 2018; Schiff et al., 2021). Moreover, a major potential reason for MOUD discontinuation is the lack of health insurance and Medicaid discontinuity, as otherwise ineligible women often loose Medicaid eligibility 60 days postpartum in most states. Thus, individual, behavioral, and structural reasons for and barriers to MOUD uptake and continuation post-delivery warrant further evaluation.

Interpersonal Factors, Violence, and Trauma

While social relationships with individuals who use substances may negatively affect women’s own substance use during pregnancy (Asta et al., 2021), there remains a dearth of research on substance use among sexual and romantic partners of perinatal women. Only one reviewed study examined the relationship between marital status and overdose and found no association among women with OUD in adjusted models (Nielsen et al., 2019). Moreover, although commonly documented in the general population of women with OUD (Stone & Rothman, 2019), no studies explored the role of violence victimization, stressful life events, or trauma in postpartum opioid outcomes. Qualitatively, perinatal women have described partner violence as preventing them from fully engaging in and adhering to drug treatment and avoiding risky drug environments (Pallatino et al., 2019). Future research should investigate how these factors impact overdose and MOUD patterns throughout the postpartum period.

Child Characteristics

While OUD can be a common cause of infant health conditions and postpartum maternal overdose, only one study examined the influence of infant- or child-related characteristics on maternal opioid outcomes post-delivery. Nielsen et al. (2019) found that among women with OUD, having an infant with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) was independently associated with increased odds of experiencing an overdose in the year following delivery compared to women with OUD who had an infant without NAS. Watching an infant struggle with health conditions, especially OUD-related conditions, can incite additional fear, stigma, and shame in women and contribute to and exacerbate maternal stress, mental health conditions, and disengagement in postpartum care and MOUD (Cleveland & Bonugli, 2014). Moreover, infant health conditions may also be associated with increased child protective services involvement and custody issues, which were not examined in this literature. Other research has documented substantial effects of custody loss among mothers, including higher mortality, poorer physical and mental health, SUDs, and overdose (Harp & Oser, 2018; Wall-Wieler et al., 2018). These child-related knowledge gaps are persistent in the literature and are imperative to understanding women’s lives and drug use post-delivery.

Healthcare and Social Ecological Environments

Healthcare and social ecological environments may play an important role in opioid outcomes post-delivery. Healthcare environments, including hospital settings, policies, and availability of services in a community, are fundamental factors in accessing treatment and other services. Two studies examined hospital characteristics of opioid-related readmissions, both finding that hospital bed size and teaching status were not associated with postpartum opioid-related hospitalizations (Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2019). However, hospital types do not represent the larger community health system availability and resources that impact women’s health (Flores et al., 2020), especially since most OUD treatment is delivered outside of hospital settings.

Relatedly, Medicaid programs are the primary insurer for persons with OUD, covering about 80% of those with OUD in pregnancy (Jarlenski et al., 2020a). However, no studies considered the role of state Medicaid policies, such as Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act or the expansion of Medicaid postpartum eligibility beyond 60 days. According to a report by the US Government Accountability Offiice (2019) in which six selected Medicaid programs were examined, all six Medicaid programs, including in both expanded and nonexpanded states, have substantially lower income requirements for parents than individuals during pregnancy, greatly limiting access to healthcare and OUD treatment beyond 60 days postpartum. For example, in Alabama (a non-expanded state), Medicaid eligibility during pregnancy is 146% of the federal poverty line versus 18% for parents; in Colorado (expanded state), eligibility is 200% during pregnancy vs. 138% for parents. The report found that in some Medicaid expanded states, 75–99% of women maintained eligibility after 60 days postpartum compared to 40–60% in nonexpanded states (Government Accountability Offiice, 2019). Availability and access to MOUD and other health and social services may prove crucial factors in reducing and preventing opioid problems.

Social and community environments in which women with OUD live also may compound other vulnerabilities and contribute to postpartum opioid opportunities. Two studies examined the relationship between OUD-related hospitalizations and residential ZIP code income quartiles, finding mixed results (Kern-Goldberger et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2019). Kern-Goldberger et al. (2020) additionally found that women had an increased risk of an OUD-related postpartum hospitalization at urban compared to rural hospitals. While these studies have begun to examine community context, research has yet to understand the social and contextual determinants that lead to opioid harms and risks during the postpartum period. The physical and social environments in which individuals live and interact contribute to health, relationships, and behaviors within that environment (Krieger, 2014; Rhodes, 2009). This is significant as individuals with OUD often live in communities experiencing systemic poverty, structural racism, housing issues, violence, and accessible drug markets (Flores et al., 2020; Mair et al., 2018; Rowe et al., 2016). Moreover, a further understanding of the geographic variation and differences in rural and urban regions of OUD post-delivery is needed. In addition to different social and economic opportunities and cultures, regions may have differing drug patterns and markets and availability of postpartum care, drug treatment, and social services (Bommersbach et al., 2023; Carpenter-Song & Snell-Rood, 2016; Kozhimannil et al., 2015; Monnat, 2019). Research should further examine these social and community environments to inform the distribution of resources and contribute to the design and implementation of structural interventions.

Intervention Evaluations

Two articles evaluated interventions or clinical practice. Cochran et al. (2018) presented a pilot intervention where patients of an outpatient program for pregnant women with SUDs received ten prenatal and four postnatal sessions with a patient navigator to assist in overcoming barriers to care and MOUD. In a small sample (n=21), opioid abstinence increased from 68% at baseline during pregnancy to 96% eight weeks postpartum. Guille et al. (2020) compared the effectiveness of OUD treatment through telemedicine versus in-person care for pregnant women at a reproductive behavioral health program. Among their sample (n=98), there were no significant differences by type of treatment received in opioid toxicology 6–8 weeks postpartum.

While positive initial results were found, larger comprehensive assessments of interventions, treatments, clinical practices, and policies are needed to understand the effectiveness of interventions and prevention efforts in this population. Few interventions, other than MOUD, have specifically targeted postpartum women and pregnancy-focused interventions rarely continue monitoring effectiveness post-delivery. Efforts to improve the continuity of healthcare and drug treatment from pregnancy to non-pregnancy may serve as an opportunity to improve postpartum MOUD retention and prevent overdose. Development and evaluation of interventions for women with OUD following delivery are needed to consider the unique intersections of parenting, co-morbid conditions, child protective services involvement, and the healthcare and social environments.

Conclusions

The progression of OUD and overdose risk during the first 12-months postpartum have been largely understudied despite high opioid-related mortality during this period. This review identifies substantial research gaps in existing literature as there remains a limited understanding of why women in the first year postpartum are vulnerable for overdose and opioid-related problems. Existing research has used a range of sample populations, study designs, and measurements to understand opioid outcomes post-delivery, making comparisons between studies difficult. While we did not evaluate study quality, it is clear that this field would benefit from a variety of rigorous methodological approaches to answering research questions.

A multitude of individual, social, and structural factors may contribute to opioid use and overdose in the first year postpartum and may serve as modifiable risk factors for interventions. Based on our review and the identified knowledge gaps, we provide the following research recommendations to address and prevent deleterious postpartum opioid use and overdose and improve maternal health:

Prioritize research on opioid use and overdose among high-risk groups, such as those with OUD diagnoses, and identify subgroups among women with OUD that may be particularly vulnerable, such as among minority populations or those with limited MOUD access.

Assess maternal opioid use, overdose, risks, and contexts throughout the first year following delivery.

Evaluate the effect of co-occurring physical and mental health conditions and polysubstance use on opioid use and overdose risk after delivery.

Investigate the social and contextual determinants that place women at increased risk of opioid problems in the year following delivery.

Further understand MOUD’s role in preventing postpartum overdose and improve programs aimed at increasing MOUD retention and treatment engagement after delivery.

Utilize rigorous research designs and multidisciplinary research methods to examine postpartum opioid use and overdose.

The provided recommendations provide a call to action and highlight future directions for researchers to address and prevent maternal opioid-related morbidity and mortality. While pregnancy may serve as an opportunity to provide interventions and improve outcomes for women with OUD, research and interventions must extend beyond delivery and consider the larger social, health, family, and community contexts in which women with OUD live. Improving the outlook of OUD among postpartum women may improve women and children’s long-term health and should be a priority in substance use and maternal health research.

Significance.

What is already known on this subject:

Opioid overdose is a leading cause of maternal death within one year of delivery. Factors that increase susceptibility to or protect against opioid problems and overdose after delivery are not well understood.

What this study adds:

Seven articles were identified in a rapid scoping review of opioid use disorder (OUD) and overdose in the year following delivery. Medication for OUD (MOUD) was the only identified factor associated with a decreased risk of postpartum overdose. Literature gaps include co-morbid conditions, interpersonal factors, and social and environmental contexts that contribute to opioid-related morbidity and mortality after delivery.

Funding:

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant F31DA052142.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval: This study did not include human subjects and was exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Consent to participate: Not applicable

Consent for publication: Not applicable

Availability of data and material: Not applicable

Code availability: Not applicable

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2018, May). ACOG committee opinion no. 736: Optimizing postpartum care. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(5), e140–e150. 10.1097/aog.0000000000002633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, & O’Malley L (2005, 2005/02/01). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asta D, Davis A, Krishnamurti T, Klocke L, Abdullah W, & Krans EE (2021, 2021/05/01/). The influence of social relationships on substance use behaviors among pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 222, 108665. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtel MD, Wood L, & Kempa NJ (2017). Stigma and social support in substance abuse: Implications for mental health and well-being. Psychiatry Research, 252, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommersbach T, Justen M, Bunting AM, Funaro MC, Winstanley EL, & Joudrey PJ (2023, 2023/02/01/). Multidimensional assessment of access to medications for opioid use disorder across urban and rural communities: A scoping review. International Journal of Drug Policy, 112, 103931. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter-Song E, & Snell-Rood C (2016). The Changing Context of Rural America: A Call to Examine the Impact of Social Change on Mental Health and Mental Health Care. Psychiatric Services, 68(5), 503–506. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman SLC, & Wu L-T (2013). Postpartum substance use and depressive symptoms: a review. Women & health, 53(5), 479–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland LM, & Bonugli R (2014). Experiences of mothers of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome in the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 43(3), 318–329. 10.1111/1552-6909.12306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran GT, Hruschak V, Abdullah W, Krans E, Douaihy AB, Bobby S, Fusco R, & Tarter R (2018, Jan/Feb). Optimizing pregnancy treatment interventions for moms (OPTI-Mom): A pilot study. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 12(1), 72–79. 10.1097/adm.0000000000000370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier A.-r. Y., & Molina RL (2019). Maternal mortality in the United States: Updates on trends, causes, and solutions. Neoreviews, 20(10), e561–e574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JD, Cairncross M, Struble CA, Carr MM, Ledgerwood DM, & Lundahl LH (2019, Mar/Apr). Correlates of treatment retention and opioid misuse among postpartum women in methadone treatment. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 13(2), 153–158. 10.1097/adm.0000000000000467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MF, Davis J, & Passik SD (2008). Reported Lifetime Aberrant Drug-Taking Behaviors Are Predictive of Current Substance Use and Mental Health Problems in Primary Care Patients. Pain Medicine, 9(8), 1098–1106. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00491.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores MW, Le Cook B, Mullin B, Halperin-Goldstein G, Nathan A, Tenso K, & Schuman-Olivier Z (2020). Associations between neighborhood-level factors and opioid-related mortality: A multilevel analysis using death certificate data. Addiction, 115(10), 1878–1889. 10.1111/add.15009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganann R, Ciliska D, & Thomas H (2010). Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implementation Science, 5, 56–56. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmill A, Kiang MV, & Alexander MJ (2019, 2019/01/01/). Trends in pregnancy-associated mortality involving opioids in the United States, 2007–2016. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 220(1), 115–116. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government Accountability Office. (2019). Medicaid: Opioid Use Disorder Services for Pregnant and Postpartum Women, and Children. (GAO-20–40). Retrieved from: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-40.pdf

- Guille C, Simpson AN, Douglas E, Boyars L, Cristaldi K, McElligott J, Johnson D, & Brady K (2020, Jan 3). Treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnant women via telemedicine: A nonrandomized controlled trial. Jama Network Open, 3(1), e1920177. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, Bohm MK, & Callaghan WM (2018). Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization - United States, 1999–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(31), 845–849. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6731a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harp KLH, & Oser CB (2018, 2018/03/01/). A longitudinal analysis of the impact of child custody loss on drug use and crime among a sample of African American mothers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 77, 1–12. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarlenski M, Krans EE, Chen Q, Rothenberger SD, Cartus A, Zivin K, & Bodnar LM (2020a). Substance use disorders and risk of severe maternal morbidity in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 216, 108236. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarlenski MP, Paul NC, & Krans EE (2020b). Polysubstance use among pregnant women with opioid use disorder in the United States, 2007–2016. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 136(3), 556–564. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2020). Opioid Overdose Deaths by Gender. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrived from: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-deaths-by-gender/

- Kern-Goldberger AR, Huang Y, Polin M, Siddiq Z, Wright JD, D’Alton ME, & Friedman AM (2020). Opioid use disorder during antepartum and postpartum hospitalizations. American Journal of Perinatology, 14, 1467–1475. 10.1055/s-0039-1694725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff MA, & Snowden JM (2018). Historical (retrospective) cohort studies and other epidemiologic study designs in perinatal research. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 219(5), 447–450. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil KB, Casey MM, Hung P, Han X, Prasad S, & Moscovice IS (2015). The Rural Obstetric Workforce in US Hospitals: Challenges and Opportunities. The Journal of Rural Health, 31(4), 365–372. 10.1111/jrh.12112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krans EE, Kim JY, Chen Q, Rothenberger SD, James III AE, Kelley D, & Jarlenski MP (2021). Outcomes associated with the use of medications for opioid use disorder during pregnancy. Addiction, 116(12), 3504–3514. 10.1111/add.15582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (2014). Got theory? On the 21 st c. CE rise of explicit use of epidemiologic theories of disease distribution: A review and ecosocial analysis. Current Epidemiology Reports, 1(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lai HMX, Cleary M, Sitharthan T, & Hunt GE (2015). Prevalence of comorbid substance use, anxiety and mood disorders in epidemiological surveys, 1990–2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154, 1–13. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, Creanga AA, & Leffert LR (2014). Opioid Abuse and Dependence during Pregnancy: Temporal Trends and Obstetrical Outcomes. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 121(6), 1158–1165. 10.1097/aln.0000000000000472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair C, Sumetsky N, Burke JG, & Gaidus A (2018). Investigating the social ecological contexts of opioid use disorder and poisoning hospitalizations in Pennsylvania. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(6), 899–908. 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangla K, Hoffman MC, Trumpff C, O’Grady S, & Monk C (2019). Maternal self-harm deaths: an unrecognized and preventable outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 221(4), 295–303. 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnish TR, Lewkowitz AK, Carter EB, & Veade AE (2021). The impact of race on postpartum opioid prescribing practices: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1), 434. 10.1186/s12884-021-03954-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz TD, Rovner P, Hoffman MC, Allshouse AA, Beckwith KM, & Binswanger IA (2016). Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004–2012. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 128(6), 1233–1240. 10.1097/aog.0000000000001695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mital S, Wolff J, & Carroll JJ (2020). The relationship between incarceration history and overdose in North America: A scoping review of the evidence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 213, 108088. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal L, & Suzuki J (2017). Feasibility of collaborative care treatment of opioid use disorders with buprenorphine during pregnancy. Subst Abus, 38(3), 261–264. 10.1080/08897077.2015.1129525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnat SM (2019). The contributions of socioeconomic and opioid supply factors to U.S. drug mortality rates: Urban-rural and within-rural differences. Journal of Rural Studies, 68, 319–335. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, & Aromataris E (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen T, Bernson D, Terplan M, Wakeman SE, Yule AM, Mehta PK, Bharel M, Diop H, Taveras EM, Wilens TE, & Schiff DM (2019). Maternal and infant characteristics associated with maternal opioid overdose in the year following delivery. Addiction. 10.1111/add.14825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AB, Uhler B, O’Brien LM, & Knuppel K (2018). Predictors of treatment retention in postpartum women prescribed buprenorphine during pregnancy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 86, 26–29. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallatino C, Chang JC, & Krans EE (2019). The intersection of intimate partner violence and substance use among women with opioid use disorder. Substance Abuse. 10.1080/08897077.2019.1671296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton BP, Krans EE, Kim JY, & Jarlenski M (2019). The impact of medicaid expansion on postpartum health care utilization among pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Substance Abuse, 40(3), 371–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peahl AF, Dalton VK, Montgomery JR, Lai YL, Hu HM, & Waljee JF (2019, Jul 3). Rates of new persistent opioid use after vaginal or cesarean birth among US women. Jama Network Open, 2(7), e197863. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, Clone S, DeHart D, & Seay KD (2016, 2016/02/01/). Treatment Access Barriers and Disparities Among Individuals with Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders: An Integrative Literature Review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 61, 47–59. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T (2009). Risk environments and drug harms: A social science for harm reduction approach. International Journal of Drug Policy, 20(3), 193–201. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe C, Santos G-M, Vittinghoff E, Wheeler E, Davidson P, & Coffin PO (2016). Neighborhood-level and spatial characteristics associated with lay naloxone reversal events and opioid overdose deaths. Journal of Urban Health, 93(1), 117–130. 10.1007/s11524-015-0023-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Terplan M, Hood M, Bernson D, Diop H, Bharel M, Wilens TE, LaRochelle M, Walley AY, & Land T (2018). Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 132(2), 466–474. 10.1097/aog.0000000000002734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff DM, Nielsen TC, Hoeppner BB, Terplan M, Hadland SE, Bernson D, Greenfield SF, Bernstein J, Bharel M, Reddy J, Taveras EM, Kelly JF, & Wilens TE (2021). Methadone and buprenorphine discontinuation among postpartum women with opioid use disorder. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.04.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Lo-Ciganic W-H, Segal R, & Goodin AJ (2020). Prevalence of substance use disorder and psychiatric comorbidity burden among pregnant women with opioid use disorder in a large administrative database, 2009–2014. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1–7. 10.1080/0167482X.2020.1727882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanaukee P, Kääriäinen J, Sillanaukee P, Poutanen P, & Seppä K (2002). Substance Use–Related Outpatient Consultations in Specialized Health Care: An Underestimated Entity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 26(9), 1359–1364. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02679.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smid MC, Schauberger CW, Terplan M, & Wright TE (2020). Early lessons from maternal mortality review committees on drug-related deaths: Time for obstetrical providers to take the lead in addressing addiction. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM, 2(4). 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smid MC, Stone NM, Baksh L, Debbink MP, Einerson BD, Varner MW, Gordon AJ, & Clark EAS (2019). Pregnancy-associated death in Utah: Contribution of drug-induced deaths. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133(6), 1131–1140. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R, & Rothman EF (2019). Opioid use and intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Current Epidemiology Reports, 6(2), 215–230. 10.1007/s40471-019-00197-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Braughton M, Bradsberry M, Howell M, Logan J, & Schwarz EB (2017). Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum care and contraception in California’s Medicaid program. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(1), 47.e41–47.e47. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Draanen J, Tsang C, Mitra S, Phuong V, Murakami A, Karamouzian M, & Richardson L (2022). Mental disorder and opioid overdose: a systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(4), 647–671. 10.1007/s00127-021-02199-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall-Wieler E, Roos LL, Nickel NC, Chateau D, & Brownell M (2018). Mortality among mothers whose children were taken into care by child protection services: A discordant sibling analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(6), 1182–1188. 10.1093/aje/kwy062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen T, Batista N, Wright JD, D’Alton ME, Attenello FJ, Mack WJ, & Friedman AM (2019). Postpartum readmissions among women with opioid use disorder. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM, 1(1), 89–98. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder C, Lewis D, & Winhusen T (2015). Medication assisted treatment discontinuation in pregnant and postpartum women with opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 149, 225–231. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Needleman J, Gelberg L, Kominski G, Shoptaw S, & Tsugawa Y (2019). Association between homelessness and opioid overdose and opioid-related hospital admissions/emergency department visits. Social Science & Medicine, 242, 112585. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]