Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common degenerative joint situation that induces pain and disability in the elderly. Traditionally, Eleutherine bulbosa bulb from Pasuruan, East Java, is used to treat many diseases, also as an anti-inflammatory.

Objective

In this research, we employed an in vivo model to examine the effects of 70% ethanol extracts of E. bulbosa (EBE) on the progression and development of OA.

Methods

A singular intraarticular injection of Monosodium Iodoacetate (MIA) was used to create the OA model in rats. The progression of OA was observed for three weeks. Furthermore, treatment of EBE at a dose of 6, 12, and 24 mg/200g BW orally for four weeks was conducted to assess the effects on decreasing IL- 1. level, joint swelling, and hyperalgesia.

Results

Induction was successful, indicated by a significant difference (P<0.05) in decreasing latency time, increasing joint swelling, and IL-1. level. EBE 24 mg/200 g BW treatment has significantly (P<0.05) reduced IL-1. levels, joint swelling, and response to hyperalgesia.

Conclusion

The 70% ethanol extract of E. bulbosa bulb has therapeutic effects on inflammation through reducing IL-1. in experimental MIA-induced osteoarthritis in a rat model. According to this study, EBE may have an effective potential new agent for OA therapy.

Key words: Osteoarthritis, Antiinflammatory, Eleutherine bulbosa, MIA, IL-1β

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent type of degenerative joint disease in the elderly.1 Clinically, the disease is associated with joint pain caused by the entire joint becoming dysfunctional, particularly the articular cartilage, synovium, subchondral bone, and other tissues with close mechanical and molecular biological interactions.2,3 Some characteristics of OA are tenderness, stiffness, joint swelling, immobility, and joint deformity. The risk factors of OA are gender, genetic, and joint injury, which then increase along with obesity and age.1,4 This disease is the leading cause of disability, with nearly 10-15% of adults over 60 years suffering from OA.5 The prevalence of knee OA is 240 per 100,000 individuals per year. In Indonesia, knee OA is 65% of people over 61 years old, 30% of people aged 40-60, and 5% less than 40 years. This incidence is estimated at 15.5% in men and 12.7% in women.6

IL-1 is implicated in the pathophysiology of knee OA due to increased production of this cytokine associated with the severity of symptoms.7 Furthermore, IL-1 has been shown to inhibit chondrocytes.8,9 IL-1Ra specifically inhibits the action of IL-1β by binding to IL-1R1.10 Strong evidence for the critical role of interleukin- 1β (IL-1β) and OA-associated regulation genes such as matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF- α), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in the development of OA have been reported. IL-1β is a proinflammatory substance that is important for responding to the immune system’s defenses against injury.11,12 The activation of signaling events by IL-1β was associated with the upregulation of MMP-13.9 Reduced chondrocyte proteoglycan synthesis, increases in the production of MMP, and the release of nitric oxide are all caused by IL-1β in the joint.13 Another pathway is the interaction of IL-1β to the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R1), triggering a proinflammatory response that leads to cartilage destruction followed by subchondral destruction. The pro-inflammatory response also causes synovial membrane inflammation, which manifests as pain.7 The osteoarthritis model using Monosodium Iodoacetate (MIA) in rats has been used for a long time and is well established. An intraarticular injection of MIA causes histopathological abnormalities in articular cartilage, similar to degenerative OA in humans. The metabolic inhibitor MIA disturbs the aerobic glycolytic pathway of cells and causes cell death by blocking the action of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in chondrocytes.14

Eleutherine bulbosa (Mill.) Urb is the Iridaceae family’s oriental medicinal plant. This plant is used in traditional medicine for treating several conditions, such as cough, anemia, heart failure, cancer, infertility, skin disease, and inflammation.15,16 Previous phytochemical compounds have been isolated from E. bulbosa, such as naphthalene, anthraquinone, naphthoquinone and their derivatives eleutherinone, eleutherine, isoeleutherine, eleutherol, eleuthone, eleutherinol 8-O- β -D-glucoside, eleuthoside.16-18 According to Tessele et al. (2011),19 eleutherine and isoeleutherine from Cipura paludosa (Iridaceae) have antihypernociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects due to their decrease in paw edema mice that induced carrageenan. E. bulbosa also contains luteolin, which inhibits cyclooxygenase and reduces pain.20 The previous study declared that E. bulbosa from Vietnam in mice with collagen antibody- induced arthritis could be used as an anti-inflammatory agent at 1000 mg/kg b.w. suppressed IL-16 and TNF-α, while the IL-10 was increased.15 This current study focused on IL-1β, which plays a crucial role in pain response. The IL-1β is able to increase the regulation of pronociceptive mediators, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) which plays an important role in pain processes. The IL- 1β signaling via cascades leads to the release and/or activation of nociceptive molecules such as prostaglandins, IL-6, substance P, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9).21

Therefore, inhibition of IL-1β is considered a potential target to lessen the pain and inflammation in the development of OA. This research investigated the antiosteoarthritis activity of 70% ethanol extract of E. bulbosa (EBE) in an osteoarthritis rat model induced by MIA.

Materials and Methods

Ethical considerations

Thirty male Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus) were purchased from the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia, in healthy condition. Rats aged 3-4 months (200-300 g) were acclimatized for seven days in the Animal Laboratory, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Airlangga. The rats were kept in ideal lighting (12-hour light-dark cycle), a temperature of 22±1°C, and a humidity of 60-80%. They also had full access to drink and food. The entire process has been authorized by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia, with Ethical Clearance No. 2.KEH.120.09.2022.

Plant materials

Eleutherine bulbosa (Mill.) Urb. was found and collected from Pasuruan Regency, East Java, Indonesia. The collected plants were determined by UPT Laboratorium Herbal Materia Medica, Batu, East Java, Indonesia (Certificate of Determination No. 074/722/102-7-A/2021). Fresh bulbs of E. bulbosa were cut into small parts, dried, and mashed with a blender to obtain a dried powder of E. bulbosa bulb (1000 g). The dried plant was extracted by maceration method using 5000 mL 70% ethanol (1:5) at room temperature for 24 h. The filtrate was obtained after filtering using Whatman’s paper no.41 and re-macerated twice. The filtrate was evaporated using a rotary evaporator at 40°C with 40 rpm until the thick extract was obtained with the constant weight. The extractive value of 70% ethanol extract of E. bulbosa bulb was calculated as % w/w yield and found at 15,98%.

Rat model

Rats were divided into six groups: the naive group was given food and water ad libitum, the negative group was assigned 0,5% Carboxy Methyl Cellulose (CMC), the positive group received meloxicam (Indofarma, Indonesia) 0.135 mg/200 g BW, and 70% ethanol extract of E. bulbosa bulb in 3 kinds of dose that given Dose 1:6 mg/200 g BW; Dose 2:12 mg/200 g BW; Dose 3:24 mg/200 g BW, respectively. Intraarticular injection of MIA (4 mg MIA dissolved in 50 ml of saline) (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was performed on all groups except the naive group under anesthesia using a combination of 10% ketamine (80 mg/kg) (Agrovet, Nicaragua) and 1% xylazine (5 mg/kg) (Holland, Netherlands) to obtain the condition of OA. Three weeks after MIA induction, all rats were checked for OA success on day 21 with the measured IL-1β levels (pretest), followed by an oral administration of 70% ethanol extract daily for 28 days based on their group. Furthermore, the response of hyperalgesia and knee joint swelling was measured with a hot plate and calibrated screw micrometer for seven weeks (on days 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, and 49), respectively. Latency response was measured with a stopwatch. After the treatment, the determination of IL-1β levels in blood serum was measured on the seventh week (day 49 as a posttest). The euthanasia process was using anesthetic overdose with the combination of 300 mg/kg ketamine and 30 mg/kg xylazine intraperitoneal.

Evaluation of parameters - hyperalgesia testing

This study used a hot plate (Ugo Basile Hot/Cold Plate 35100, Gemonio, Italy) to observe the response hyperalgesia of all groups on days 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, and 49. The hot plate method was a traditional method, using unrestrained rats, and depends on the rats’ own visual to express thermal pain. A rat was left unrestrained on a metal surface kept at a constant temperature of 55±0.5°C for the hot plate test. The investigator documented the response latency, and the time it takes to generate a nocifensive reaction. Nocifensive behavior includes withdrawal or licking of the hind paw, leaning posture, stamping, and jumping. The rats were taken off the hot plate as soon as the response was seen.

Joint swelling measurement

Joint swelling was measured on the ipsilateral knee of the rat. All groups were measured utilizing a calibrated screw micrometer, on days 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, and 49.

IL-1β cytokine assay

Blood samples from the tail vein were collected into a blood collection tube on days 21 and 49. The centrifugation at 3000 rpm was performed to take the blood serum. The levels of IL-1β were determined using commercial rat IL-1β ELISA kits (Bioenzy, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocols.

Statistical analysis

Data from rat experiments were collected, and the results were presented as mean ± SD of 5 rats in each group using Graph Pad Prism 7 while the analytical statistic using SPSS 25. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the data statistically, and then the LSD post hoc test was performed. A P-value of less than 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

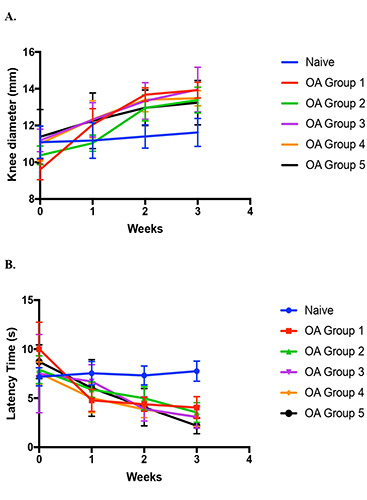

After the treatment, data were collected and analyzed. According to Figure 1, the knee joint was swelling as the increased diameter was around 20-30%. Figure 1 also shows that from the second week up to the third week the progression of OA seems at a steady state. It indicates a specific set of beginning conditions because a steady state is an example of an attractor that can be attained.22,23 Based on Figure 2, in the third week IL-1. level of the naive group and negative control have a significant difference (P<0.01). Thereby, in the fourth week, the rats were separated into groups and given the treatment for 28 days. The negative control rats were inflamed and marked by swollen joints. The knee diameter, time latency, and IL-1. level have been measured.

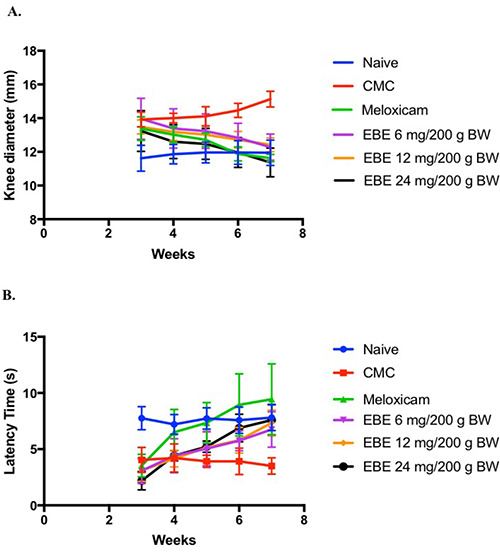

In comparison, there was a significant difference between the rats that were given EBE 24 mg/200 g BW and the other dose but no significant difference with the positive control (meloxicam) group. In addition, to evaluate osteoarthritis based on the clinical data, time latency and level of IL-1. of the joints were assessed. The time latency of the negative control group showed a significantly differed from the other groups (P<0.05). Treatment with EBE 6, 12, and 24 mg/200g BW was increased each week. On the first week after treatment, the time latency of positive control and EBE 24 mg/200 g BM group was increased up to 80%, but EBE 6 and 12 mg/200g BW group were increased up to 40%. In the second and third weeks, the time latency of all the treatment groups increased up to 20%, but in the last week, the increase of time latency decreased by 10% (Figure 3b).

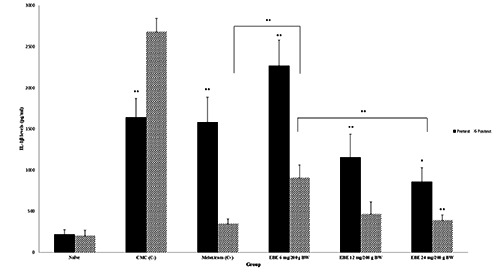

Therefore, the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1. was measured in rats receiving EBE. According to Figure 3, EBE 12 and 24 mg/200 g BW significantly (P<0.01) suppressed the amount of IL- 1. in the serum of rats compared with negative control after 28 days. EBE dose 24 mg/200 g BW is also significantly different from EBE 6 mg/200 g BW.

Figure 1.

The development of OA after injecting MIA in three weeks (A) rat knee diameter; (B) time latency. Data are present as Mean±SD base on N=5 for all groups.

Figure 2.

The effects of EBE in vivo MIA induced OA model (A) Rat’s knee diameter was significantly decreased after the treatment of EBE as compared to the negative control group (P<0.01); (B) Time latency was significantly increased after the treatment of EBE as compared to the negative control group (P<0.05). Data are present as Mean±SD base on n=5 for all groups.

Figure 3.

The IL-1ß levels on the pretest increased in rat serum compared with the naïve group. The cytokine was measured in the serum of EBE treated rats at three doses (6, 12, and 24 mg/200 g BW) together with negative (CMC) and positive (meloxicam) groups. The levels of IL-1ß were decreased after treatment as compared with the negative control group (P<0.01). Data are present as Mean±SD base on n=5 for all groups. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Discussion

Inflammation and pain are recognized as the primary cause of OA symptoms and development. MIA disrupts the metabolism of chondrocytes by inhibiting glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, which impacts the production of ROS and the breakdown of the cartilage matrix. MIA also increases proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1. and TNF-α that may cause the production of COX-2 and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).8 Additionally, IL-1. has been shown to accelerate cartilage breakdown in articular chondrocytes and inhibit the synthesis of cartilage matrix (5). MMPs and ADAMTS are zinc-dependent endopeptidases that play an important role in cartilage matrix destruction.24 The production of MMPs and ADAMTS is significantly increased during OA in response to proinflammatory mediators, including IL-1. and TNF- α.25 Administration of EBE at various doses could increase latency time as well as decrease joint swelling and IL-1. in the OA rats model. It was due to the compounds in EBE, such as flavonoids and naphthoquinone. Quercetin is a basic structure that forms other flavonoids. Before having the first pass effect, the small intestine absorbs quercetin, then delivered it to the liver by portal circulation. The quercetin will diffuse throughout the body’s tissues at that point. It is well known that quercetin significantly binds to plasma albumin. Quercetin inhibits the Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) receptor and has an opioid action.20 In naphthoquinone derivatives, Hong et al. (2008)26 showed clear evidence that T helper cell proliferation is partially inhibited by both eleutherine and isoeleutherine. The substances also elevated levels of the cytokine IL-2 and apoptosis. Through the secretion of several cytokines, the biological response to inflammation is managed by T cells. In addition, another study showed that eleutherine and isoeleutherine might affect the mechanical hypernociception induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Eleutherine has been reported to be able to interfere with paw edema caused by PGE2 or histamine significantly. It is well known that the release of many inflammatory mediators occurs as a result of inflammatory hypernociception.19 Otherwise, in silico prediction of b-sitosterol in the Eleutherine americana shows that it has anti-inflammatory activity and has a strong affinity for COX-2 greater than celecoxib. The in silico toxicity prediction indicated that the compound was not toxic.27 It is interesting that b-sitosterol is a steroid molecule with high closeness to corticosteroids, which are known as anti-inflammatory drugs. This may explain the high affinity of b-sitosterol to COX-2 as well as the intermolecular connections created.28

The study’s limitations were recognized. First, this research did not histologically examine the rat knee’s articular cartilage. The quantitative results revealed some distinct tendencies, and current study findings are important and useful for creating an OA model. The present study’s findings significantly contributed to the knowledge of mechanisms in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Second, induced OA using the chemical compound MIA. Some previous studies claimed that chemical has a different pathophysiology unrelated to post-traumatic OA.29,20 However, several studies have revealed morphological and histological alterations in the articular tissues that are identical to the characteristics of human OA.14,31

EBE at various doses has been able to increase latency time as well as decrease joint swelling and IL-1. in OA rats model, but only EBE 24 mg/200 g BW reduced joint swelling and IL-1. level as well as meloxicam. Enhancing EBE dosage reduces the sign of antiosteoarthritis which helps decrease pain and inflammation.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that EBE decreased the IL-1β induced inflammatory response, reduced joint swelling, and increased time latency. Additionally, MIA caused OA in the rat model, and EBE had a protective effect against OA degeneration. These findings suggested that EBE 12 and 24 mg/200 g BW might be a potential treatment for OA as well as meloxicam.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Faculty of Excellence Research (Penelitian Unggulan Fakultas) of Airlangga University with the contract No. 545/UN3.15/PT/2022

Funding Statement

Funding: None.

References

- 1.Yunus MHM, Nordin A, Kamal H. Pathophysiological perspective of osteoarthritis. Medicina 2020;56:614-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grassel S, Zaucke F, Madry H. Osteoarthritis: Novel Molecular Mechanisms Increase Our Understanding of the Disease Pathology. J Clin Med 202;10:1938-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldring SR, Goldring MB. Changes in the osteochondral unit during osteoarthritis: structure, function and cartilage–bone crosstalk. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016;12:632-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui A, Li H, Wang D, et al. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in populationbased studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020;29–30:100587-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang X, Pei W, Ni B, et al. Chondroprotective and antiarthritic effects of galangin in osteoarthritis: An in vitro and in vivo study. Eur J Pharmacol 2021;906:174232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddik M, Haryadi RD. The risk factors effect of knee osteoarthritis towards postural lateral sway. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol 2020;14:1787-92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budhiparama NC, Lumban-Gaol I, Sudoyo H, et al. Interleukin-1 genetic polymorphisms in knee osteoarthritis: What do we know? A meta-analysis and systematic review. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2022;30:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khotib J, Pratiwi AP, Ardianto C, et al. Attenuation of IL-1. on the use of glucosamine as an adjuvant in meloxicam treatment in rat models with osteoarthritis. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 2020;30:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasheed Z, Al-Shobaili HA, Rasheed N, et al. MicroRNA-26a- 5p regulates the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase via activation of NF-κB pathway in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys 2016;594:61-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood 2011;117:3720-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Castejon G, Brough D. Understanding the mechanism of IL-1β secretion. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2011;22:189-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinarello CA, Simon A, van der Meer JWM. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in a broad spectrum of diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012;11:633-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joosten LAB, Smeets RL, Koenders MI, et al. Interleukin-18 promotes joint inflammation and induces interleukin-1-driven cartilage destruction. Am J Clin Pathol 2004;165:959–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi I, Matsuzaki T, Kuroki H, et al. Induction of osteoarthritis by injecting monosodium iodoacetate into the patellofemoral joint of an experimental rat model. PLoS ONE 2018;13:e0196625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanh PTB, Thao DT, Nga NT, et al. Toxicity and anti-inflammatory activities of an extract of the Eleutherine bulbosa rhizome on collagen antibody-induced arthritis in a mouse model. Nat Prod Commun 2018;13:883-6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim Hyun S, Hong Hye-Jin, Kim Sohyun, et al. Chemical constituents of the rhizome of Eleutherine bulbosa and their inhibitory effect on the pro-inflammatory cytokines production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Bull Korean Chem Soc 2013;34:633-6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Insanu M, Kusmardiyani S, Hartati R. Recent studies on phytochemicals and pharmacological effects of Eleutherine Americana Merr. Procedia Chem 2014;13:221-8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamarudin AA, Sayuti NH, Saad N, et al. Eleutherine bulbosa (Mill.) Urb. Bulb: review of the pharmacological activities and its prospects for application. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:6747-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tessele P, Delle Monache F, Quintao N, et al. A new naphthoquinone isolated from the bulbs of Cipura paludosa and pharmacological activity of two main constituents. Planta Med 2011;77:1035-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hafizh M, Indiastuti DN, Mukono IS. Analgesic effect of dayak onion (Eleutherine americana (Aubl.) Merr.) on mice (Mus musculus) by hot plate test method. BHSJ 2021;4: 22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren K, Torres R. Role of interleukin-1β during pain and inflammation. Brain Research Reviews 2009;60:57-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen H, Qin J, Shi H, et al. Rhoifolin ameliorates osteoarthritis via the Nrf2/NF-κB axis: in vitro and in vivo experiments. Osteoarthr Cartil 2022;S1063458422000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobie EA. An introduction to dynamical systems. Sci Signal; 4. Epub ahead of print 20 September 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malemud CJ. Inhibition of MMPs and ADAM/ADAMTS. Biochem Pharmacol 2019;165:33-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincent TL. IL-1 in osteoarthritis: time for a critical review of the literature. F1000Res 2019;8:934-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong J-H, Yu ES, Han A-R, et al. Isoeleutherin and eleutherinol, naturally occurring selective modulators of Th cell-mediated immune responses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008;371:278-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damayanti S, Puspaningrum D, N. Muhammad H, et al. Interaction of the chemical constituents of Eleutherine americana (AUBL.) MERR. EX K. HEYNE with cyclooxygenase and H5N1 RNA polymerase: an in-silico study. Rasayan J Chem 2021;14:844–54. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raghavamma STV, Rama Rao N, Devala Rao G. Inhibitory potential of important phytochemicals from Pergularia daemia (Forsk.) chiov., on snake venom (Naja naja). J Genet Eng Biotechnol 2016;14:211-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuyinu EL, Narayanan G, Nair LS, et al. Animal models of osteoarthritis: classification, update, and measurement of outcomes. J Orthop Surg Res 2016;11:19-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang L, Li L, Geng C, et al. Monosodium iodoacetate induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway involving ROS production and caspase activation in rat chondrocytes in vitro: apoptosis induced by monosodium iodoacetate. J Orthop Res 2013;31:364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]