Abstract

Reading is a rapid, distributed process that engages multiple components of the ventral visual stream. To understand the neural constituents and their interactions that allow us to identify written words, we performed direct intracranial recordings in a large cohort of humans. This allowed us to isolate the spatiotemporal dynamics of visual word recognition across the entire left ventral occipitotemporal cortex. We found that mid-fusiform cortex is the first brain region sensitive to lexicality, preceding the traditional visual word form area. The magnitude and duration of its activation are driven by the statistics of natural language. Information regarding lexicality and word frequency propagates posteriorly from this region to visual word form regions and to earlier visual cortex, which, while active earlier, show sensitivity to words later. Further, direct electrical stimulation of this region results in reading arrest, further illustrating its crucial role in reading. This unique sensitivity of mid-fusiform cortex to sub-lexical and lexical characteristics points to its central role as the orthographic lexicon - the long-term memory representations of visual word forms.

Introduction

Reading is foundational to modern civilization, yet the mechanisms by which the human brain converts orthographic inputs to lexical and semantic concepts are poorly understood. Orthographic representations are thought to be organized hierarchically in the ventral occipitotemporal cortex (vOTC) with bottom-up reading-specific processes that culminate in the visual word form area (VWFA)1–3, a region that selectively responds to written stimuli in known scripts and is involved in sub-lexical processing. At the front end of this process is the conversion of the retinal image of a written word to an invariant representation of its component letters via a bank of letter detectors3–5. Beyond this there are two possible processes that occur. The first posits “local combination detectors”3,4, that encode combinations of frequent, highly diagnostic groups of letters, bigrams (e.g. “E left of N”) or morphemes (e.g. “TION”), to interpret words. The second mechanism posits “spatial coding”6,7, wherein each letter is bound to its ordinal position, and the combination of letters by positions creates a unique lexical code for each word, that is independent of intermediate sub-lexical units. Recently, it has been argued that these two codes coexist in fluent readers: the bigram code for fast lexical access and the positional letter code for accurate reading of novel words and pseudo-words via the phonological route8. The notion of local combination detectors has received support from functional MRI experiments which reveal a bigram frequency effect in classical VWFA1–3 and a posterior-to-anterior gradient of responsivity to letters, frequent bigrams, quadrigrams and whole words within the left vOTC3,9,10. Additionally it appears that both automatic11,12 and attentionally-driven2,13 top-down influences play a crucial role in modulating activity within vOTC during reading. However, the roles that specific components of vOTC play in the integration of bottom-up processes1–3 with top-down influences11,14–21, and how this enables rapid orthographic-lexical-semantic transformations, are unknown.

More broadly, the majority of our knowledge of the cortical architecture of reading arises from functional MRI. However, the rapid speed of reading demands that we use methods with very high spatiotemporal resolution to study these processes. For instance, the posterior to anterior gradient in vOTC described above, and its sensitivity to lexicality13 and word frequency13,19,22,23, could arise from late top-down feedback from lexical areas2,15. These temporal limitations of fMRI preclude a true understanding of interactive information flow between substrates in the ventral stream. To comprehensively chart the spatial organization and functional roles of orthographic and lexical regions across the ventral visual pathway during sub-lexical and lexical tasks, we performed intracranial recordings in 35 individuals using 784 electrodes, using paradigms with systematically varied levels of attentional modulation of orthographic processing. Specifically, we isolated separable, functionally distinct vOTC regions highly sensitive to the structure and statistics of natural language at multiple stages of orthographic processing and then showed, through direct cortical stimulation, a causal link to the ability to read.

Results

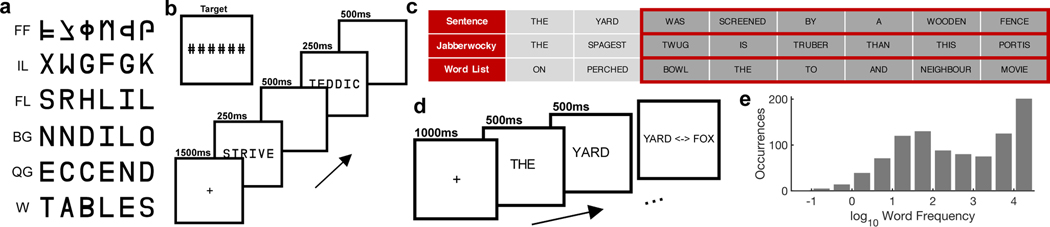

Patients participated in passive viewing and sentence reading tasks designed to disambiguate the roles of sub-regions and top-down attentional modulation within the vOTC. In the passive viewing task, patients viewed strings of false font characters (FF), infrequent letters (IL), frequent letters (FL), frequent bigrams (BG), frequent quadrigrams (QG) or words (W) while detecting a non-letter target (Figure 1a,b). In the sentence reading task, patients attended to regular sentences, word lists or jabberwocky sentences, all presented in rapid serial visual presentation format, followed by a forced choice decision of presented vs non-presented stimuli (Figure 1c,d).

Figure 1. Experimental design of the passive viewing and sentence reading tasks.

(a) Example stimuli from each of the six stimulus categories in the passive viewing task. FF: False Font, IL: Infrequent Letters, FL: Frequent Letters, BG: Frequent Bigrams, QG: Frequent Quadrigrams, W: Words. (b) Schematic representation of the passive viewing stimulus presentation. (c) Example stimuli from the three experimental conditions of the sentence reading task highlighting the words used for subsequent analyses (Words 3 to 8). (d) Schematic representation of the sentence reading stimulus presentation. (e) Histogram of log10 word frequency for the sentence stimuli. A log10 frequency of 1 represents 10 instances per million words and 4 means 10,000 instances per million words

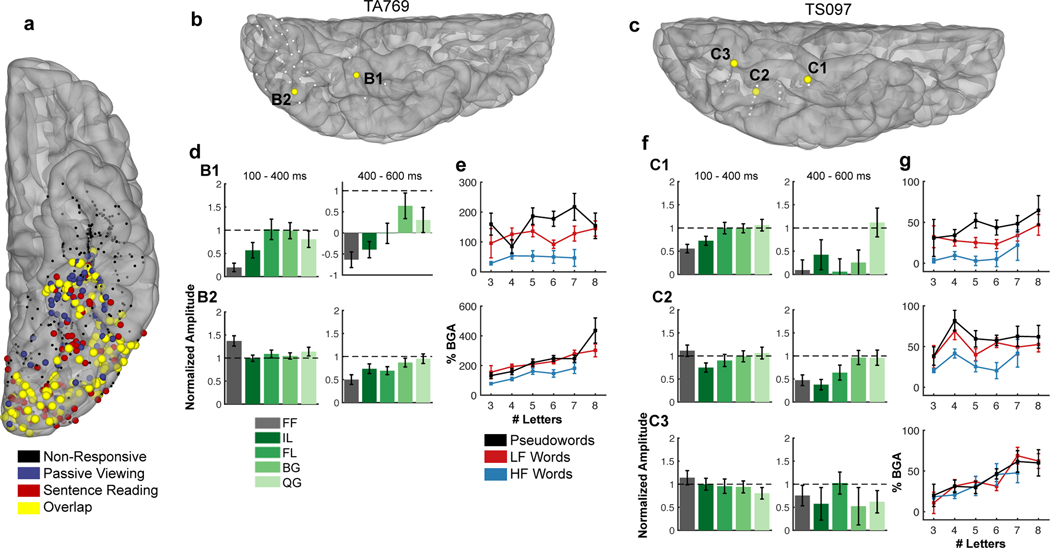

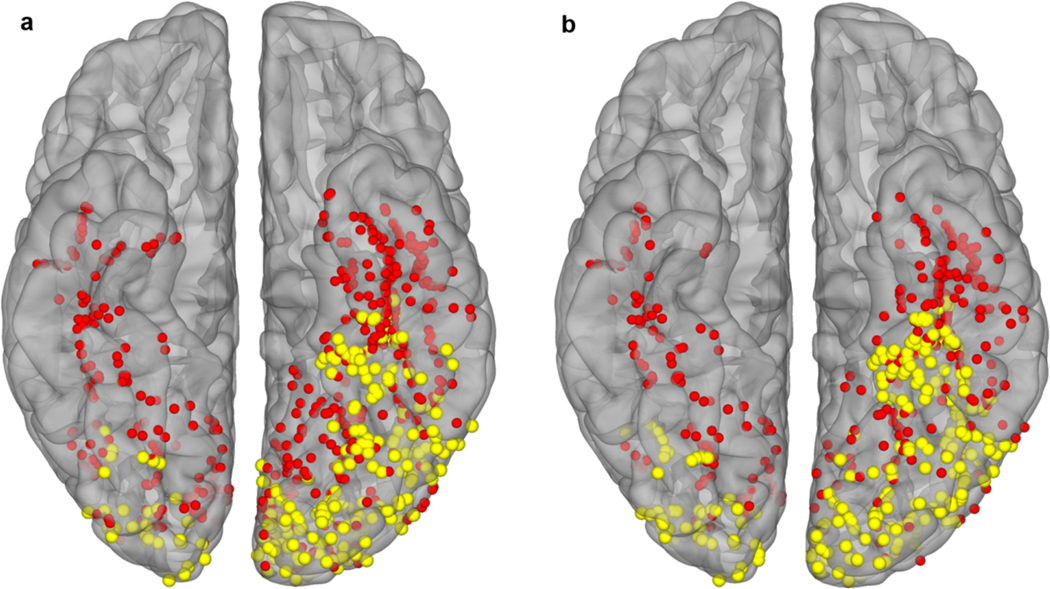

Word responsive electrodes were defined as all electrodes with >20% gamma band activation and P < 0.01 (one-tailed z-test) above a pre-stimulus baseline (−500 to −100 ms) during real word viewing. Responsiveness was seen across the entire vOTC from the occipital pole to mid-fusiform cortex in the left, language-dominant hemisphere, and only in the occipital pole of the right hemisphere (Figure 2a; Extended Data Figure 1). All presented analyses were constrained to the left hemisphere.

Figure 2. Population activation map and single patient activations.

(a) Locations of all electrodes within the left vOTC ROI that were responsive to real words (>20% activation over baseline) during passive viewing (blue), sentence reading (red) or both tasks (yellow). Electrodes that were not responsive at all are in black. (b,c) Electrodes within single subjects, demonstrating posterior-to-anterior, location-based variability in responses to each task. (d,f) Word-amplitude normalized selectivity profiles in the passive viewing task at early (100–400ms; left) and late (400–600ms; right) time points. Horizontal dashed lines represent word response. (e,g) Plots of broadband gamma activity (BGA; 70 −150 Hz; 100–400ms) display sensitivity to length, frequency (high frequency (HF) and low frequency (LF) words), and lexical status.

Orthographic Processing in vOTC

We computed gamma band activity in two windows to characterize early (100–400 ms24) and late processes (400–600 ms). Based on prior work by us24,25 and by others that characterizes functionality of the vOTC19,26, we demarcated it into anterior and posterior regions (y = −40 mm). We found that anterior vOTC sites were more responsive to words than to FF and IL stimuli, especially in the later time window, when word induced activation was sustained longer than for other stimuli (Fig. 2d,f). Further, anterior vOTC showed greater activation for lower vs. higher frequency words (SUBTLEXus27; 100–400 ms) and longer rather than shorter words (Fig. 2e,g).

In distinction, posterior vOTC responded most to false fonts and did not distinguish between other non-word stimuli in early time windows (100–400 ms), however at later time points (400–600 ms) activation there was sensitivity to sub-lexical complexity. In the sentence reading task, posterior sites were sensitive to word length and less so to word frequency.

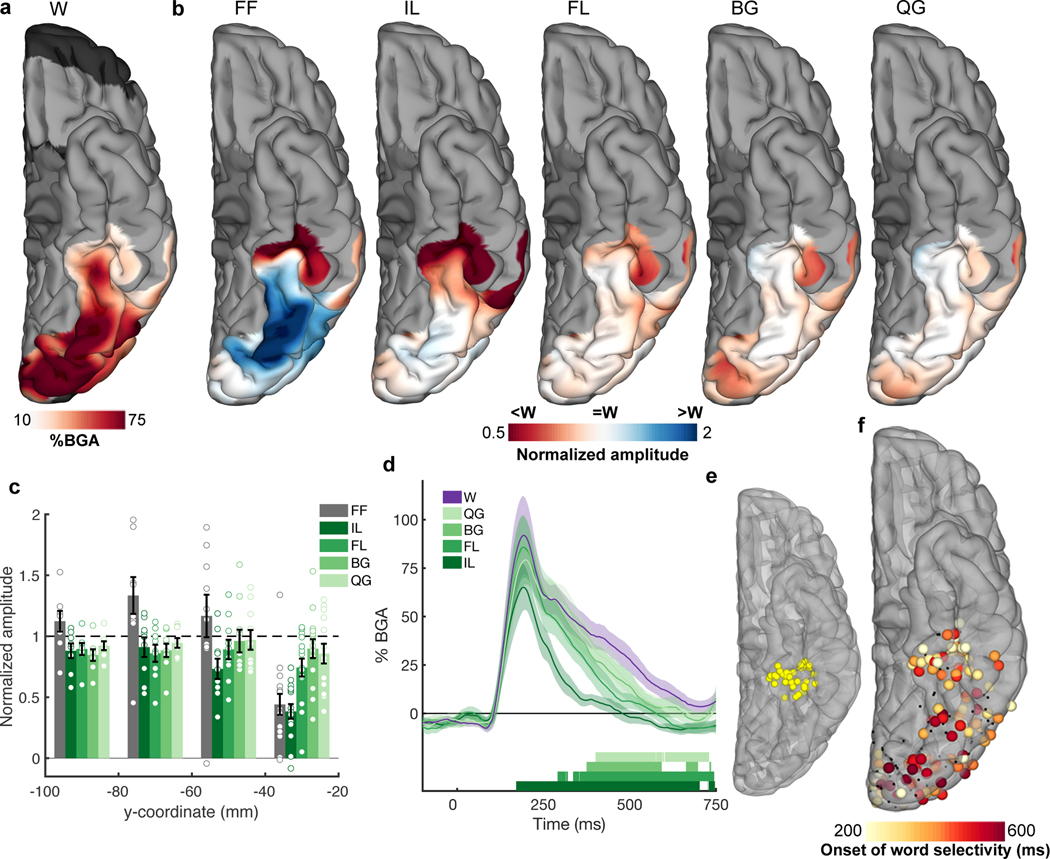

To evaluate the consistency of these effects across the population, we performed a mixed-effects, multilevel analysis (MEMA) of broadband gamma (70–150 Hz) power between 100–400 ms, in grouped normalized 3D stereotactic space. This analysis is specifically designed to account for sampling variations and to minimize effects of outliers25,28–34. This MEMA map showed that written words activated the left vOTC from occipital pole to mid-fusiform cortex (Figure 3a). We then used this map to delineate regions showing preferential activation for words compared to non-word stimuli (Figure 3b). A clear posterior-to-anterior transition - from occipital cortex to mid-fusiform gyrus - was observed. We again noted that anterior vOTC – specifically mid-fusiform cortex responded prominently to words. It also distinguished between IL stimuli and real words but did not show substantial difference between words and word-like stimuli (FL, BG and QG). This selectivity pattern was reversed in posterior occipitotemporal cortex which was more active for FF stimuli than for words.

Figure 3. Spatial mapping of selectivity to hierarchical orthographic stimuli.

(a) MEMA activation map showing the regions of significant activation to the real word stimuli during passive viewing (100 – 400 ms, 27 patients). This activation map was used as a mask and a normalization factor for the activations of the non-word stimuli (b). Normalized amplitude maps showing regions with preferential activation to words (red) or non-words (blue). (c) Electrode selectivity profiles grouped in 20 mm intervals along the y (antero-posterior) axis in Talairach space from all word responsive electrodes (207 electrodes, 20 patients). Horizontal dashed lines represent word response. Individual data points are overlaid. (d) Contrasts of the lettered non-words against words for electrodes within mid-fusiform cortex (e; 39 electrodes, 13 patients), showing latency differences for when each non-word category is distinguished from words. Coloured bars under the plots represent regions of significant difference from words (one-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank, q<0.01). (f) Spatial map of the initial timing of significant word selectivity (207 electrodes, 20 patients). Electrodes that did not reach significance shown in black.

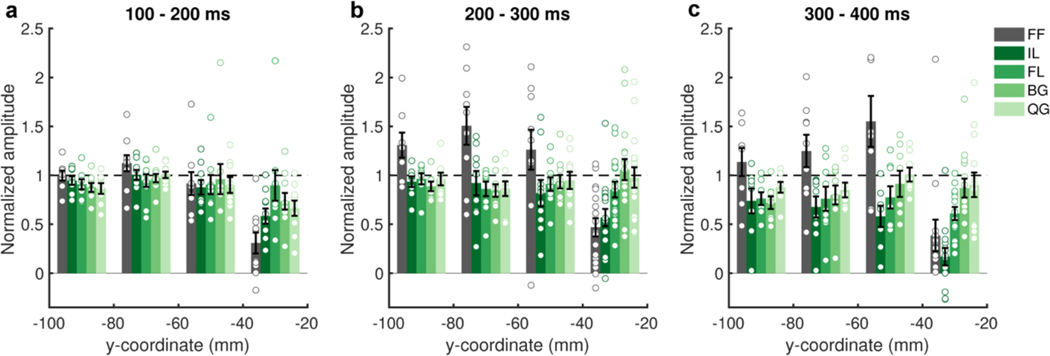

To further characterize this spatial gradient, we plotted responses as a function of electrode location along the y axis in Talairach space. Posterior to −40mm there was no significant difference between real words and any other stimulus type (Figure 3c; −100 - −80mm: one-way ANOVA, F(5,42) = 3.68, P = 0.008, Tukey’s, P = 0.32 – 0.90, M = −0.12 – 0.15, Cohen’s d = −0.54 – 0.43; −80 - −60mm: one-way ANOVA, F(5,48) = 4.83, P = 0.001, Tukey’s, P = 0.05 – 0.99, M = −0.33 – 0.13, Cohen’s d = −0.26 – 0.63; −60 - −40mm: one-way ANOVA, F(5,54) = 2.05, P = 0.09, Bayes Factor (BF01) > 109). Around −40 mm in the antero-posterior axis in Talairach space, a distinct transition occurred: responsivity to FF and IL dropped substantially (one-way ANOVA, F(5,84) = 13.3, P < 0.001; Tukey’s, FF: P < 0.001, M = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.27 – 0.85, Cohen’s d = −0.57, IL: P < 0.001, M = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.33 – 0.90, Cohen’s d = −0.63) and responses became fully selective for words and word-like stimuli (FL, BG and QG; Tukey’s, P = 0.10 – 0.90, M = 0.10 – 0.25, Cohen’s d = −0.26 – −0.10). An analysis at a higher temporal resolution revealed that vOTC anterior of −40 mm initially distinguishes word-like letter strings from IL and FF between 100 – 200 ms (Extended Data Figure 2; one-way ANOVA, F(5,54) = 6.49, P < 0.001; Tukey’s, FF: P < 0.001, M = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.29 – 1.09, Cohen’s d = −0.89, IL: P = 0.037, M = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.02 – 0.82, Cohen’s d = −0.54).

A 4D representation of the evolution of the functional selectivity in the vOTC was generated by performing MEMA on short, overlapping time windows (150 ms width, 10 ms spacing) to generate successive images of cortical activity (Video 1, Video 2). These analyses clearly illustrate the primacy of the mid-fusiform cortex in word identification. Within the mid-fusiform cortex (39 electrodes, 13 patients) each non-word class has a distinct difference in duration of activation - with increasing sub-lexical structure, the latency of word/non-word distinction increases (IL: 170 ms, FL: 290 ms, BG: 380 ms, QG: 410 ms; one-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank, q < 0.01; Figure 3d, Video 2).

This 4D representation also reveals that at later time periods (>300 ms) an anterior-to-posterior propagation of word selectivity occurs - posterior regions show greater sustained activity for words rather than non-words. To further elaborate this antero-posterior spread of word selectivity, we calculated the sensitivity index (d-prime for words vs. all non-word stimuli) over time at each electrode in vOTC to find the earliest point where responses for real vs. non-words diverged (Figure 3e; p < 0.01 for >50ms). Again, the mid-fusiform cortex showed the earliest word selective response (~250 ms) and this selectivity then progressed posteriorly to occipital pole (~500 ms). A correlation of the latency of d-prime significance with the y axis quantified this anterior-to-posterior selectivity gradient (Pearson correlation, r(205) = −0.33, P < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.48 - −0.21).

In summary, word selectivity in vOTC during passive viewing occurs first in mid-fusiform cortex (mFus). This selectivity then spreads posteriorly to earlier visual regions such as posterolateral vOTC, which while active early, demonstrates word selectivity later. Within mid-fusiform cortex we observe latency differences in word/non-word categorization based on the sub-lexical complexity of presented letter strings.

Lexical Processing in Mid-Fusiform Cortex

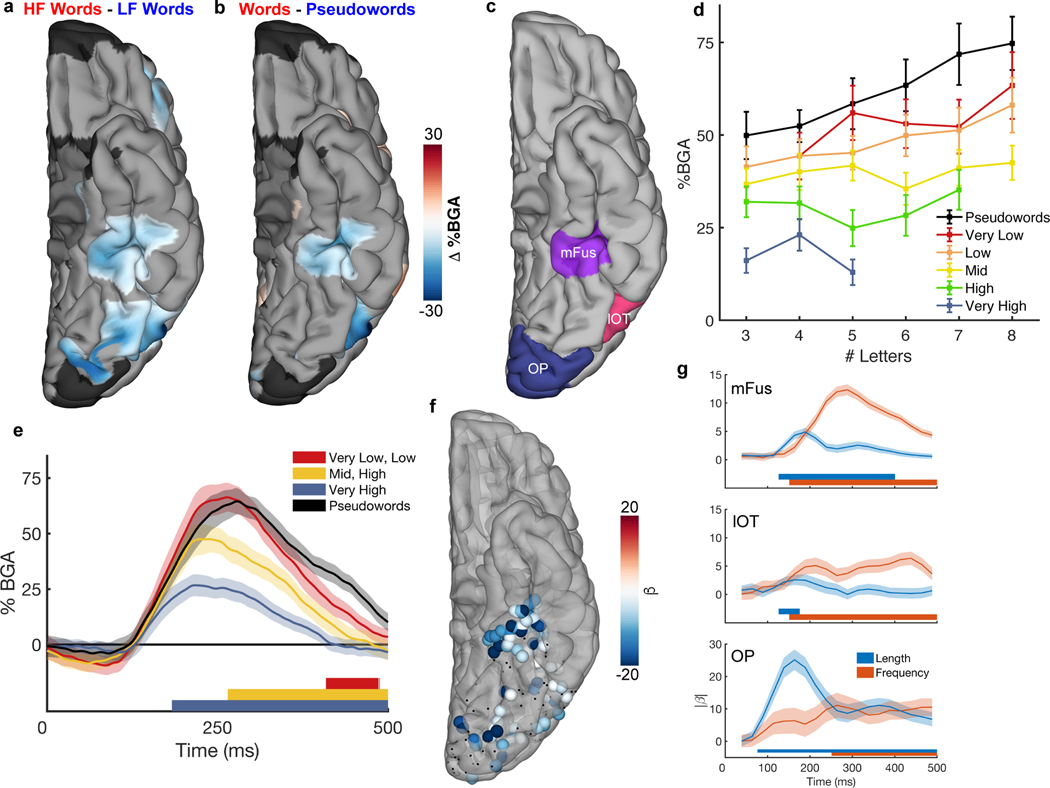

Next, we sought to examine how this spatiotemporal lexical response pattern relates to higher order processes, such as sentence reading, that engage the entire reading network. Lexical contrasts between high vs. low frequency words and real vs. pseudowords, of gamma activity between 100–400 ms after each word, revealed two significant clusters consistent across both contrasts – the mid-fusiform cortex (mFus) and lateral occipitotemporal gyrus (Figure 4a,b). In this task, where words were attended, we saw a reversal of the word vs non-word selectivity seen in the previous, passive-viewing task: pseudowords in Jabberwocky sentences showed greater activation than real words2,13, suggesting the task itself modulates activity in mFus.

Figure 4. Spatiotemporal map of word frequency and lexicality effects during sentence reading.

Contrast MEMA of (a) high frequency (HF; f > 2.5) vs low frequency (LF; f < 1.5) words from the sentence condition and (b) real words vs pseudowords (content words from sentences vs content words from Jabberwocky), using only words that were matched for length (28 patients). (c) Delineation of ROIs- mFus: Mid-fusiform cortex, lOT: Lateral occipitotemporal cortex, OP: Occipital Pole. (d) Mid-fusiform cortex activation to real words from the sentence condition separated by word frequency and length. (e) Contrasts of different frequency words against pseudowords, within mid-fusiform cortex, showing latency differences between when each word frequency band can be distinguished from pseudowords (49 electrodes, 15 patients). Coloured bars under the plots represent regions of significant difference from pseudowords (one-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank, q<0.01). (f) Individual electrodes showing significant modulation of gamma activity by word frequency (multiple linear regression, q<0.05; 196 electrodes, 20 patients). Electrodes with non-significant modulation are black. (g) Time courses (LME, beta ± SE) of length and frequency sensitivity within the three ROIs. Coloured bars under the plots represent regions of significant effect (q<0.01).

To quantify the relative sensitivity of mFus (49 electrodes, 15 patients; Figure 4c) to word frequency and word length, we performed a linear mixed effects (LME) analysis with fixed effects modelling word length and log word frequency (Figure 4d). A large proportion of the variance of this region’s activity (r2 = 0.73) is explained by word frequency (t(336) = −10.9, β = −7.6, P < 0.001, 95% CI = −8.9 – −6.2), and word length (t(336) = 4.6, β = 2.4, P < 0.001, 95% CI = 1.4 – 3.5), though their interaction has no significant impact on mFus activity (t(336) = −1.1, β = −0.45, P = 0.29, 95% CI = −1.3 – 0.4, BF01 = 45). Further, to eliminate the confound of transition probabilities inherent to sentence construction, we separately analysed activity for the word list condition (Extended Data Figure 3). This LME model revealed no significant interaction between word frequency in syntactically correct sentences or in unstructured word lists (t(580) = −0.55, β = −0.3, P = 0.58, 95% CI = −1.3 – 0.8, BF01 = 49), thus disambiguating word frequency from predictability. We also assessed effects of other closely related parameters, bigram frequency and orthographic neighbourhood for the pseudoword stimuli in mid-fusiform cortex, that have been invoked by “local combination detector” based reading models3,4. We found no significant effects of bigram frequency (LME: t(156) = 1.8, β = 4.4, P = 0.08, 95% CI = −0.5 – 9.3, BF01 = 4.0), mean positional bigram frequency (LME: t(187) = 0.05, β = −0.11, P = 0.96, 95% CI = −3.8 – 4.0, BF01 = 23), open bigram frequency (LME: t(195) = 1.1, β = 1.9, P = 0.26, 95% CI = −1.4 – 5.3, BF01 = 11) or orthographic neighbourhood (LME: t(84) = 0.96, β = 4.9, P = 0.34, 95% CI = −5.3 – 15.3, BF01 = 3.9).

Lastly, we evaluated the effect of word frequency on latency of lexicality in mFus by computing time courses of activation for high, mid and low frequency words and pseudowords, all matched for word length. We found a clear separation of duration of activity dependent on word frequency. High frequency words (180 ms) were distinguishable from pseudowords earliest, followed by mid-frequency words (270 ms) and lastly low frequency words (400 ms) (one-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank, q < 0.01; Figure 4e).

Temporal Dynamics of Lexical Processing

To replicate this analysis at the level of individual electrodes rather than for the population, we performed a multiple linear regression using broadband gamma activity at individual electrodes (Figure 4f). Like the MEMA (Figure 4a), this also revealed distinct separations in activity between mid-fusiform cortex and lateral occipitotemporal cortex. An LME model over time (Figure 4g) showed an effect of word length first at the occipital pole (75 ms) and then more anteriorly. Conversely, frequency sensitivity appeared earliest in lateral occipitotemporal cortex and mid-fusiform cortex (150 ms) and spread posteriorly. Thus, across all our data, we see two temporal stages of lexical selectivity, initial selectivity in mid-fusiform cortex followed by an anterior-to-posterior spread of selectivity.

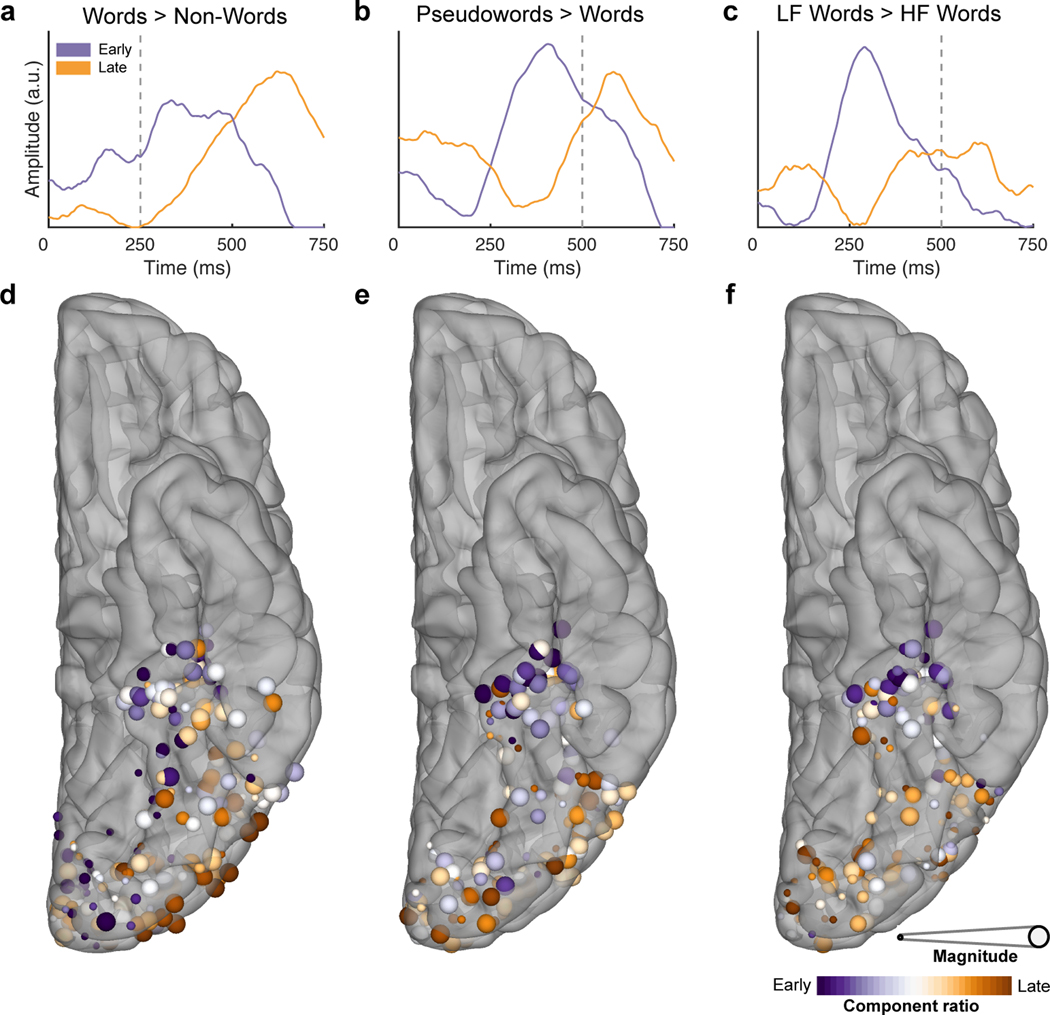

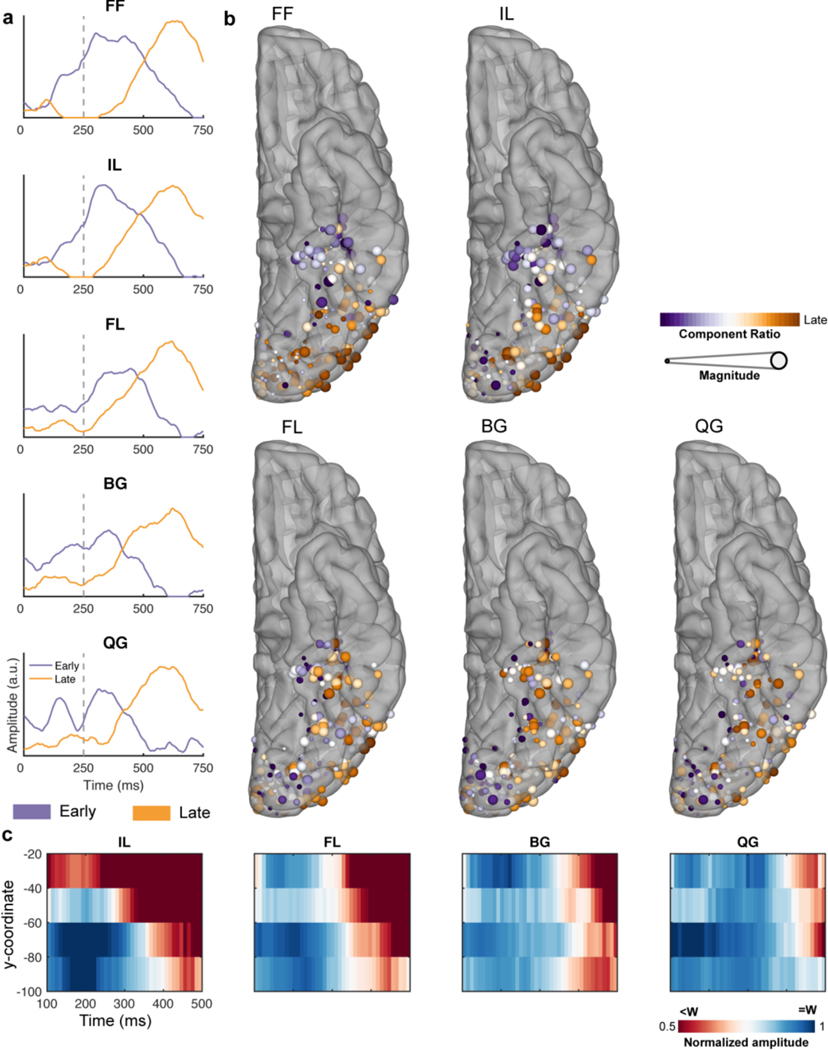

In our final analysis, we used an unsupervised clustering algorithm, non-negative matrix factorization (NNMF), on the time courses of the lexical and sub-lexical selectivity to quantify their spatiotemporal overlap and separability. An NNMF of the time courses of d-prime selectivity for words vs all non-words in the passive viewing task (Figure 5a) revealed a now familiar pattern - an early component in mid-fusiform and a late component in posterolateral vOTC and occipital sites (Fig. 5d). These components were preserved in analyses for each of the non-word conditions (Extended Data Figure 4a,b). With increasing sub-lexical complexity, the early component diminished, and the late component remained highly consistent, representing latency differences in the mid-fusiform for distinguishing these conditions from words (Figure 3d; Extended Data Figure 4c).

Figure 5. Antero-posterior differences in the timing of frequency and lexicality effects.

Temporal (a,b,c) and spatial (d,e,f) representations of the two archetypal components generated from the NNMF for the contrasts of words vs non-words in the passive viewing task (a,d; 207 electrodes, 20 patients), words vs pseudowords (b,e) and high (HF) vs low (LF) frequency words (c,f) during sentence reading (196 electrodes, 20 patients). Vertical dashed lines denote word offset time. Spatial representations (d,e,f) are coloured based on the weighting of their membership to either component. Size is based on the magnitude of the contrast between experimental conditions.

An NNMF analysis of time courses of z-scores of lexical selectivity, distinguishing pseudowords from real words and high from low frequency words (Figure 5b,c), revealed an almost identical pattern - an early component in mid-fusiform cortex and a late component over posterolateral vOTC and occipital sites (Figure 5e,f). The late component was remarkably similar in time course to that seen in the passive viewing task, however, the early component was variable across these two conditions, reflecting differences in latency in the distinction of different frequency words discussed earlier.

Direct Cortical Stimulation of Reading Areas

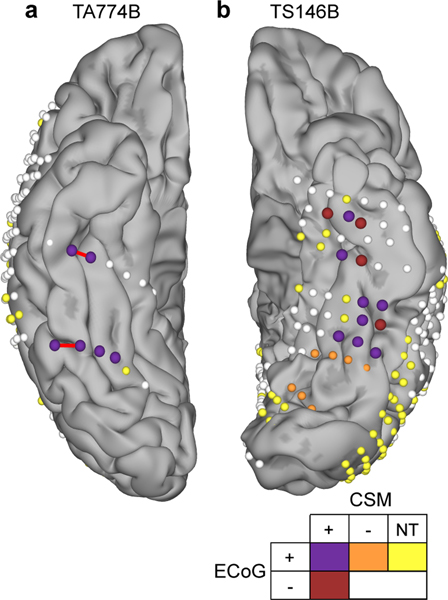

To test the causal, rather than correlational role of these regions in reading, we performed direct cortical stimulation of the vOTC in two patients with SDE electrodes who had coverage across both the mid-fusiform cortex and lateral occipitotemporal gyrus in their language-dominant hemisphere (one right and one left hemisphere dominant as proven by intracarotid amytal testing) (Figure 6). Stimulation of either region resulted in slowed word production or full reading arrest (Video 3). Both patients reported comparable subjective experiences, that the words were clearly visible and in focus but they were unable to read them; “I can see it, It’s like I don’t know how to read” (TA774B), “Even though I can see the words I can’t say them” (TS146B). Stimulation during other naming and speech production tasks resulted in no deficits. Both patients reported no perceptual differences between stimulation at each site.

Figure 6. Cortical stimulation mapping (CSM) of reading.

Electrode localizations of the two patients who underwent reading CSM, highlighting electrodes active during electrocorticography (ECoG) of word reading (ECoG+; >20% BGA above baseline) and those leading to reading arrest during stimulation (CSM+). Sites not active during reading (ECoG-), not leading to reading disruption during CSM (CSM-) or not tested (NT) during CSM are noted. Red bars indicate the electrode pairs stimulated in Video 3. Patient TA774B was right hemisphere dominant for language, confirmed by intra-carotid sodium amobarbital injection.

Discussion

Our work reveals two spatiotemporally distinct constituents of the vOTC that perform distinct roles and are causally linked to reading: mid-fusiform cortex and lateral occipitotemporal gyrus. Of these, our work shows the central role of the mid-fusiform cortex in both word vs. non-word discrimination and lexical identification. The amplitude and duration of activity in these regions is highly sensitive to the statistics of natural language, including word frequency and lexicality.

Our finding that orthographic-to-lexical transformation occurs in mid-fusiform cortex is concordant with emerging evidence from lesion-symptom mapping35–37 and intracranial stimulation studies38,39. It is also congruent with functional imaging studies of word frequency13,19,22,23 and those that show greater activation for attended pseudowords than known words in the vOTC13. We find that lateral occipitotemporal cortex, while active earlier, displays sensitivity to lexical processing later than mFus cortex. The early and late selectivity in these regions during both sub-lexical and lexical processing is a potential correlate of bottom-up and top-down processes. The existence of two separable ventral cortical regions with distinct lexical and sub-lexical sensitivities is concordant with the view of a non-unitary VWFA19,26,40.

An orthographic lexicon41,42, or the long-term memory representations of which letter strings correspond to familiar words is expected to be tuned to word frequency and lexicality. Indeed, these two features were found to be coded earliest in mid-fusiform cortex and drive its activity. Our model, incorporating just word frequency and length explained 73% of the variance of mid-fusiform activation. This central role of the mid-fusiform has also recently been suggested by selective hemodynamic changes following training to incorporate new words into the lexicon43,44.

The latency distinctions we observed in the mid-fusiform for words of varying lexical and sub-lexical frequency are also consistent with a heuristic where the prime driver of search in the neural lexicon is word frequency, and this search terminates once a match is found45,46. Under this hypothesis, higher frequency words are matched to a long-term memory representation faster than infrequent words, while pseudowords require the longest search times, since they do not match any long-term memory representations. These latency differences invoke the possibility that this region functions as the “bottleneck” that limits reading speed19,47,48.

Given previous behavioural and imaging results, we initially predicted sensitivity in vOTC to orthographic neighbourhood or bigram frequency, thought to be predictors of speed and accuracy of non-word identification49–51. During passive viewing there were latency differences in word/non-word discrimination in mid-fusiform based on n-gram frequencies. However, during sentence reading neither of these factors showed significant effects on pseudoword activation in mid-fusiform cortex. The influence of these factors on orthographic processing may depend on the demands of the specific task52,53. Specifically, both factors have been shown to play a role in how quickly participants reject non-words in lexical decision, and may be more indicative of how participants perform that particular task rather than reflect automatic word identification processes.

The existence of an anterior-to-posterior spread of lexical and sub-lexical information from mid-fusiform cortex to earlier visual processing regions implies recursive feedback and feedforward interactions between multiple stages of visual processing within the ventral stream. This notion has a storied past in cognitive models of reading, including the interactive activation model5, its derivatives42,54, and the interactive account14,15. The direct measurement of this anterior-to-posterior spread from mid-fusiform implies its role in mediating input from frontal regions26 during word11,12,21 and object55 recognition.

Our data suggest that during bottom-up prelexical processing, there may be a direct transition from letter recognition to the lexicon. Here, we found that during the initial bottom-up phase of orthographic processing, the full gradient which was reported in fMRI3,9,10 was not immediately present. Rather, in the first 300 ms following stimulus onset, only false fonts and infrequent letters were sharply distinguished from other stimuli. It is only in a later time window, starting around 300 ms or more, that stimuli with frequent bigrams, quadrigrams and real words separate in the brain (Figure 3). This suggests that the fMRI signals observed by Vinckier et al. were mostly due to a late, and presumably top-down, stage of processing.

It is possible that small regions sensitive to letter bigrams could have been missed by intracranial sampling. At present, however, the minimal hypothesis that agrees with the current data is that during bottom-up processing, a location-specific representation of letters, sensitive to word length, is directly followed by a lexical representation of the recognized word, sensitive only to word frequency - as postulated in spatial-coding models and in accordance with a few other MEG and intracranial studies56,57. Following this bottom-up stage, visual areas would be expected to receive top-down feedback. For pseudoword stimuli, this feedback would be proportional to how close the stimuli are to existing items in the lexicon, i.e. to what extent they approximate real words, thus explaining the gradient previously seen in fMRI9.

In this framework, efficient recognition of written words would be primarily based on a fast, prelexical recognition of individual letters. During reading acquisition, frequent letters would become more efficiently coded in occipital and occipitotemporal cortices, as suggested by several fMRI studies58–60. This proposal is compatible with a recent psychophysical study which evaluated the impact of literacy on the perception of letters and their combinations61. The results suggested that reading acquisition is not necessarily accompanied by a growing sensitivity to frequent bigrams, but by an improved coding of individual letters and their precise locations, thus reducing the interactions between nearby letters61,62.

The spatiotemporal resolution of intracranial recordings provides unparalleled insights into reading processes, unobtainable via other means. Furthermore, fMRI measures of hemodynamic responses in the vicinity of mid-fusiform cortex, are prone to be degraded by susceptibility artifacts63,64. These features may also explain the novelty of our findings relative to the functional imaging literature.

While the involvement of mid-fusiform in aspects of both sub-lexical and lexical processing in reading is reasonably unambiguous, the specificity of this region to orthographic input needs more study, perhaps at scales smaller than afforded by the electrodes used here. We have previously shown that left mid-fusiform cortex is a critical lexical hub for both visually and auditory cued naming25,33, and these data imply that it is in fact a multi-modal lexical hub whose role includes encoding orthographic information. However, as we show here, stimulation38,39 or lesioning35–37 of the mid-fusiform can lead to selective disruption of orthographic naming, potentially suggesting separable orthographic specific regions in the mid-fusiform. This could also be interpreted as there being a lack of redundant processing pathways for written language as compared to other domains, resulting in orthographic processing being more susceptible to disruption. It is generally accepted that CSM is the gold-standard method of causally testing the behavioural correlates of a cortical region. Effects of cortical stimulation are strongest locally around the stimulating electrode pair, however, a potential limitation of this assumption is the possibility of producing non-local effects by propagation of the applied current via functional pathways65.

In summary, we have demonstrated a central role of the mid-fusiform cortex in the early processing of the statistics of lexical and sub-lexical information in visual word reading. We have characterized the activity of mid-fusiform cortex as being sensitive, in both amplitude and duration, to the frequencies of words in natural language. Further, we have shown the existence of an anterior-to-posterior spread of lexical information from mid-fusiform to earlier visual regions including classical VWFA.

Methods

Participants:

A total of 35 participants (17 male, 19–60 years, 5 left-handed, IQ 94 ± 13, age of epilepsy onset 19 ± 10 years) took part in the intracranial recording experiments after written informed consent was obtained. All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston as Protocol Number HSC-MS-06–0385. Inclusion criteria for this study were that the participants were English native speakers, left hemisphere dominant for language and did not have a significant additional neurological history (e.g. previous resections, MR imaging abnormalities such as malformations or hypoplasia). Three additional participants were tested but were later excluded from the main analysis as they were determined to be right hemisphere language dominant. Hemispheric dominance for language was determined either by fMRI activation (n = 1) or intra-carotid sodium amobarbital injection (n = 2). Given electrode placement in these patients was for clinical need rather than experimental purposes, no statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes but the number of patients required was based on providing adequate coverage of the areas being studied, greater than that of previous comparable studies25,34,38,56. Two additional participants (both female) were recruited post-hoc for cortical stimulation mapping in their language dominant hemisphere (as confirmed by intra-carotid sodium amobarbital injection), based on the findings of the main analysis. Permission was obtained from patients for whom identifiable images are presented.

Electrode Implantation and Data Recording:

Data were acquired from either subdural grid electrodes (SDEs; 7 patients) or stereotactically placed depth electrodes (sEEGs; 28 patients) implanted for clinical purposes of seizure localization of pharmaco-resistant epilepsy. SDEs were subdural platinum-iridium electrodes embedded in a silicone elastomer sheet (PMT Corporation; top-hat design; 3mm diameter cortical contact) and were surgically implanted via a craniotomy following previously described methods66–68. sEEG probes (PMT corporation, Chanhassen, Minnesota) were 0.8 mm in diameter, had 8–16 contacts and were implanted using a Robotic Surgical Assistant (ROSA; Medtech, Montpellier, France)69,70. Each contact was a platinum-iridium cylinder, 2.0 mm in length with a centre-to-centre separation of 3.5–4.43 mm. Each patient had multiple (12–20) probes implanted.

Following implantation, electrodes were localized by co-registration of pre-operative anatomical 3T MRI and post-operative CT scans using a cost function in AFNI71. Electrode positions were projected onto a cortical surface model generated in FreeSurfer72, and displayed on the cortical surface model for visualization68.

Intracranial data were collected using the NeuroPort recording system (Blackrock Microsystems, Salt Lake City, Utah), digitized at 2 kHz. They were imported into MATLAB initially referenced to the white matter channel used as a reference by the clinical acquisition system, visually inspected for line noise, artefacts and epileptic activity. Electrodes with excessive line noise or localized to sites of seizure onset were excluded. Each electrode was re-referenced offline to the common average of the remaining channels. Trials contaminated by inter-ictal epileptic spikes were discarded.

Stimuli and Experimental Design:

27 participants undertook a task passively viewing orthographic stimuli and 28 participants undertook a rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) sentence reading task, reading real sentences, Jabberwocky sentences and word lists. 2 additional participants undertook a word and pseudoword reading task and later underwent cortical stimulation mapping.

All stimuli were displayed on a 15.4” 2880×1800 LCD screen positioned at eye-level at a distance of 80 cm and presented using Psychtoolbox73 in MATLAB.

Orthographic Passive Viewing:

Participants were presented with 80 runs, each six stimuli in length and containing one six-character stimulus from each of six categories in a pseudorandom order. Stimulus categories, in increasing order of sub-lexical structure, were (1) false font strings, (2) infrequent letters, (3) frequent letters, (4) frequent bigrams, (5) frequent quadrigrams and (6) words (Figure 1a). n-gram frequencies were calculated from the English Lexicon Project74. False fonts used a custom-designed pseudo-font with fixed character spacing. Each letter was replaced by an unfamiliar shape with an almost equal number of strokes and angles and similar overall visual appearance. The stimuli were based on a previous study9, converted for American English readers.

A 1500 ms fixation cross was presented between each run. During each run, each stimulus was presented for 250 ms followed by a blank screen for 500 ms. Stimuli were presented in all capital letters in Arial font with a height of 150 pixels. To maintain attention, participants were asked to press a button on seeing a target string of ###### presented. The target stimulus was inserted randomly into 20 runs as an additional stimulus and was excluded from analysis. Detection rate of the target stimuli was 91 ± 10 %.

Sentence Reading:

Participants were presented with eight-word sentences using an RSVP format (Figure 1c). A 1000 ms fixation cross was presented followed by each word presented one at a time, each for 500 ms. Words were presented in all capital letters, in Arial font with a height of 150 pixels. To maintain the participants’ attention, after each sentence they were presented with a two-alternative forced choice, deciding which of two presented words was present in the preceding sentence, responding via a key press. Only trials with a correct response were used for analysis. Overall performance in this task was 92 ± 4 % with a response time of 2142 ± 782 ms.

Stimuli were presented in blocks containing 40 real sentences, 20 Jabberwocky sentences and 20 word lists in a pseudorandom order. Each participant completed between 2–4 blocks.

Word choice was based on stimuli used for a previous study75. Jabberwocky words were selected as pronounceable pseudowords, designed to fill the syntactic role of nouns, verbs and adjectives by inclusion of relevant functional morphemes.

Single Word Reading:

Participants were presented with monosyllabic words or pseudowords and were asked to read them aloud. Each word was presented for 1500 ms with a 2000 ms inter-word fixation cross presented. Words were presented in all lower-case letters, in Arial font with a height of 150 pixels. Stimuli were presented in two blocks, each containing 40 real words and 40 pseudowords.

Cortical Stimulation Mapping:

Trains of 50Hz balanced 0.3-ms period square-waves were delivered to adjacent electrodes for 3–5 s during the task66. Stimulation was applied using a Nihon Kohden PE-210A stimulator. At each electrode pair, stimulation was begun at a current of 2 mA and increased stepwise by 1–2 mA until either an overt phenomenon was observed, after-discharges were induced, or the 10-mA limit was reached. Positive pairs were identified as sites that repeatably resulted in reading arrest while reading standard passages (i.e. the Grandfather and Rainbow passages).

Signal Analysis:

A total of 5666 electrode contacts were implanted, 891 of these were excluded from analysis due to proximity to the seizure onset zone, excessive interictal spikes or line noise.

Electrode level analysis was limited to a region of interest (ROI) based on a brain parcellation from the Human Connectome Project76. The ROI encompassed the entire occipital lobe and most of the ventral temporal surface, excluding parahippocampal and entorhinal regions (Figure 2b).

Analyses were performed by first bandpass filtering raw data of each electrode into broadband gamma activity (BGA; 70–150Hz) following removal of line noise (zero-phase 2nd order Butterworth bandstop filters). A frequency domain bandpass Hilbert transform (paired sigmoid flanks with half-width 1.5 Hz) was applied and the analytic amplitude was smoothed (Savitzky - Golay FIR, 3rd order, frame length of 151 ms; Matlab 2017a, Mathworks, Natick, MA). BGA is presented here as percentage change from baseline level, defined as the period −500 to −100 ms before each run in the passive viewing task or before word 1 of each sentence.

Electrodes were tested to determine whether they were word responsive within the window 100–400ms post stimulus onset, a time window previously used for determining selectivity of vOTC24. This was done by measuring the response to real words in the passive viewing task, or all words in word position 1 in sentence reading. Responsiveness threshold was set at 20% amplitude increase above baseline with P<0.01(one-tailed z-test). 601 and 459 electrodes respectively were located in left, language-dominant vOTC for the passive viewing and sentence reading tasks of which 207 and 196 (in 20 patients each) were word responsive (Figure 2b).

When presented as grouped electrode response plots, within-subject averages were taken of all electrodes within each ROI then presented as the across subject average, with coloured patches representing ±1 standard error.

Linguistic Analysis:

When separating content and function words, function words were defined as either articles, pronouns, auxiliary verbs, conjunctions, prepositions or particles. We quantified word frequency as the base-10 log of the SUBTLEXus frequency27. This resulted in a frequency of 1 meaning 10 instances per million words and 4 meaning 10,000 instances per million words. Bigram frequency was calculated as the mean frequency of each adjacent two letter pair, as calculated from the English Lexicon Project74. Orthographic neighbourhood was quantified as the orthographic Levenshtein distance (OLD20); the mean number of single character edits required to convert the word into its 20 nearest neighbors77.

Statistical Modelling:

Word Selectivity:

The onset time of word selectivity within individual electrodes was defined as the first time point where the d-prime of word vs. all non-word stimuli became significant (P<0.01 for at least 50 ms). The significance threshold was determined by bootstrapping with randomly assigned category labels, using 1000 repetitions.

Non-negative matrix factorization (NNMF):

NNMF is an unsupervised clustering algorithm78. This method expresses a non-negative matrix A as the product of “class weight” matrix W and “class archetype” matrix H, minimizing ||A – WH||2.

The factorization rank k = 2 was chosen for all analyses in this work. Repeat analyses with higher ranks did not identify additional response types. Inputs to the factorization were d-prime values (Figure 5a) or z-scores (Figure 5b,c, Extended Data Figure 4a) that were half-wave rectified. These were calculated for the m electrodes at n time points for the temporal analyses. Factorization generated a pair of class weights for each electrode and a pair of class archetypes – the basis function for each class. Component ratio was defined as the magnitude normalized ratio between the class weights at each electrode. Magnitude was defined as the sum of class weights at each electrode.

Surface-based mixed-effects multilevel analysis (SB-MEMA):

SB-MEMA was used to provide statistically robust28–30 and topologically precise25,31–33 effect estimates of band-limited power change from the baseline period. This method, developed and described previously by our group79,80, accounts for sparse sampling, outlier inferences, as well as intra- and inter-subject variability to produce population maps of cortical activity. Significance levels were computed at a corrected alpha-level of 0.01 using family-wise error rate corrections for multiple comparisons. The minimum criterion for family-wise error rates was determined by white-noise clustering analysis (Monte Carlo simulations, 1000 iterations) of data with the same dimension and smoothness as that analyzed80. All maps were smoothed with a geodesic Gaussian smoothing filter (3 mm full-width at half-maximum) for visual presentation.

Amplitude normalized maps were created by normalizing to the beta values of an activation mask. The activation mask comprised of significant activation clusters satisfying the following conditions; corrected P<0.01, beta>10% and coverage>2 patients.

To produce the activation movies, SB-MEMA was computed on short, overlapping time windows (150 ms width, 10 ms spacing), generating individual frames of cortical activity.

Linear Mixed Effects (LME) Modelling:

For grouped electrode statistical tests, a linear mixed effects model was used. LME models are an extension on a multiple linear regression, incorporating fixed effects for fixed experimental variables and random effects for uncontrolled variables. The fixed effects in our model were word length and word frequency and our random effect was the patient. Word length was the number of letters in each word. This variable was mean-centred to avoid an intercept at an unattainable value - a zero-letter word. Word frequency was converted to an ordinal variable to facilitate combination across patients. The ordinal categories for frequency (f) were very high (f>3.5), high (2.5< f ≤3.5), mid (1.5< f ≤2.5), low (0.5< f ≤1.5) and very low (f≤0.5). The random effect of patient allowed a random intercept for each patient to account for differences in mean response size between patients.

These predictors were used to model the average BGA in the window 100–400ms after word onset. Word responses within each length/frequency combination were averaged within patient. Patients only contributed responses to length/frequency combinations for which they had at least five word-epochs to be averaged together.

For single electrode analysis of the frequency effect a multiple linear regression was used. Factors word length and word frequency were again used. Word length was again mean-centred. Word frequency was treated as a continuous variable. For this analysis all the word epochs from the sentence and word list conditions were used. Results were corrected for multiple comparisons using a Benjamini-Hochberg False Detection Rate (FDR) threshold of q<0.05.

Temporal effects of length and frequency on cortical activity were tested using the LME model with 25 ms, non-overlapping windows. Significance was accepted at an FDR corrected threshold of q<0.01.

For statistical comparisons, data were assumed to be normal in distribution. Given the distinct experimental conditions, data collection and analysis could not reasonably be performed in a manner blinded to the conditions of the experiments.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Lateralization of Word Responsive Electrodes in Ventral Cortex.

Map of word responsive (yellow; activation >20% above baseline) and unresponsive (red) electrodes in the passive viewing (a; 27 patients) and sentence (b; 28 patients) tasks. In the non-dominant right hemisphere (n = 14 patients), word responses were confined to occipital cortex.

Extended Data Figure 2. Spatiotemporal mapping of selectivity to hierarchical orthographic stimuli.

Word-amplitude normalized selectivity profiles grouped in 20 mm intervals along the y (antero-posterior) axis in Talairach space for three consecutive time windows (20 patients). Within each time window, electrodes with >20% activation above baseline in response to words were utilized. Averaged within patient. Standard errors represent between patient variability. Individual data points are overlaid. Horizontal dashed lines represent word response.

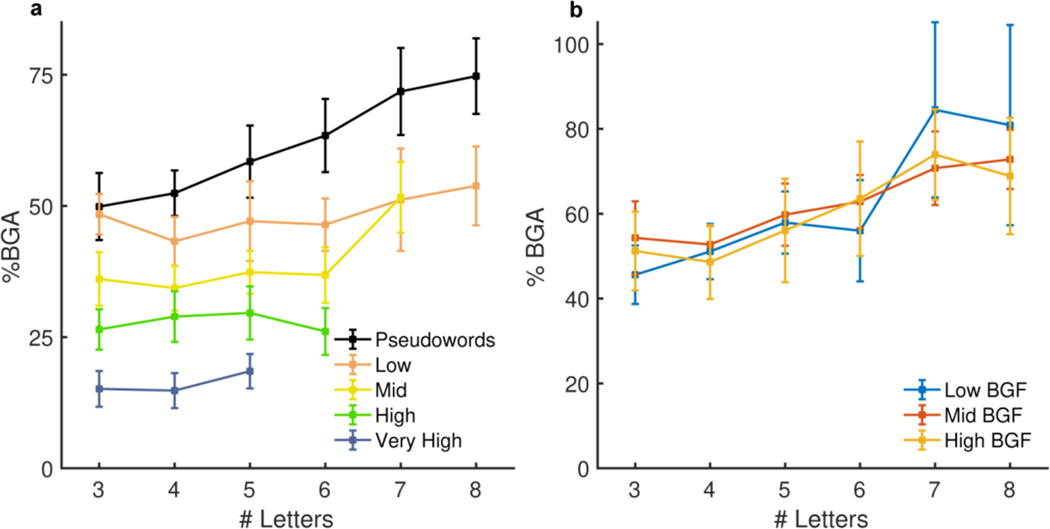

Extended Data Figure 3. Lexical and Sub-Lexical Frequency Effects in Mid-Fusiform Cortex.

(a) Mid-fusiform responses to real words from the word list condition separated by word frequency and length (49 electrodes, 15 patients). (b) Pseudoword responses in mid-fusiform cortex from the Jabberwocky condition separated by bigram frequency (BGF) and word length (49 electrodes, 15 patients).

Extended Data Figure 4. Timing of the selectivity to hierarchical orthographic stimuli in the passive viewing task.

(a) Temporal representations of the two archetypal components generated from NNMF of the z-scores of words against each non-word condition. (b) Spatial map of the NNMF decompositions of the z-score word selectivity (207 electrodes, 20 patients). (c) Spatiotemporal representation of word vs non-word selectivity (non-word normalized to word activity) for each of the letter-form conditions. Electrode selectivity profiles were grouped every 20 mm along the antero-posterior axis in Talairach space. Each condition shows an anterior-to-posterior spread of word selectivity (red). FF: False Font, IL: Infrequent Letters, FL: Frequent Letters, BG: Frequent Bigrams, QG: Frequent Quadrigrams.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Yujing Wang for assistance coordinating patient data transfers and Eliana Klier for comments on previous versions of this manuscript. We express our gratitude to all the patients who participated in this study; the neurologists at the Texas Comprehensive Epilepsy Program who participated in the care of these patients; and all the nurses and technicians in the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit at Memorial Hermann Hospital who helped make this research possible. This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute on Deafness and Communicable Disorders via the BRAIN initiative “Research on Humans” grant NS098981. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Code Availability

The custom code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author on request.

Data Availability

The datasets generated from this research are not publicly available due to them containing information non-compliant with HIPAA and the human participants the data were collected from have not consented to their public release. However, they are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Dehaene S, Le Clec’H G, Poline J-B, LeBihan D. & Cohen L. The visual word form area: a prelexical representation of visual words in the fusiform gyrus. Neuroreport 13, 321–325 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dehaene S. & Cohen L. The unique role of the visual word form area in reading. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 254–262 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehaene S, Cohen L, Sigman M. & Vinckier F. The neural code for written words: A proposal. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 335–341 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grainger J. & Van Heuven WJB Modeling letter position coding in printed word perception. in The Mental Lexicon; (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClelland JL & Rumelhart DE An interactive activation model of context effects in letter perception: I. An account of basic findings. Psychol. Rev. 88, 375–407 (1981). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis CJ The spatial coding model of visual word identification. Psychol. Rev. 117, 713–758 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitney C. How the brain encodes the order of letters in a printed word: The SERIOL model and selective literature review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 8, 221–243 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grainger J, Dufau S. & Ziegler JC A Vision of Reading. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20, 171–179 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinckier F. et al. Hierarchical Coding of Letter Strings in the Ventral Stream: Dissecting the Inner Organization of the Visual Word-Form System. Neuron 55, 143–156 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Binder JR, Medler DA, Westbury CF, Liebenthal E. & Buchanan L. Tuning of the human left fusiform gyrus to sublexical orthographic structure. Neuroimage 33, 739–748 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whaley ML, Kadipasaoglu CM, Cox SJ & Tandon N. Modulation of Orthographic Decoding by Frontal Cortex. J. Neurosci. 36, 1173–1184 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heilbron M, Richter D, Ekman M, Hagoort P. & de Lange FP Word contexts enhance the neural representation of individual letters in early visual cortex. Nat. Commun. 11, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kronbichler M. et al. The visual word form area and the frequency with which words are encountered: Evidence from a parametric fMRI study. Neuroimage 21, 946–953 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price CJ & Devlin JT The myth of the visual word form area. Neuroimage 19, 473–481 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price CJ & Devlin JT The Interactive Account of ventral occipitotemporal contributions to reading. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 246–253 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kay KN & Yeatman JD Bottom-up and top-down computations in word- and face-selective cortex. Elife 6, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song Y, Hu S, Li X, Li W. & Liu J. The Role of Top-Down Task Context in Learning to Perceive Objects. J. Neurosci. 30, 9869–9876 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Starrfelt R. & Gerlach C. The Visual What For Area: Words and pictures in the left fusiform gyrus. Neuroimage 35, 334–342 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White AL, Palmer J, Boynton GM & Yeatman JD Parallel spatial channels converge at a bottleneck in anterior word-selective cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 10087–10096 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pammer K. et al. Visual word recognition: The first half second. Neuroimage 22, 1819–1825 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodhead ZVJ et al. Reading front to back: MEG evidence for early feedback effects during word recognition. Cereb. Cortex 24, 817–825 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuster S, Hawelka S, Hutzler F, Kronbichler M. & Richlan F. Words in Context: The Effects of Length, Frequency, and Predictability on Brain Responses during Natural Reading. Cereb. Cortex 26, 3889–3904 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graves WW, Desai R, Humphries C, Seidenberg MS & Binder JR Neural systems for reading aloud: A multiparametric approach. Cereb. Cortex 20, 1799–1815 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadipasaoglu CM, Conner CR, Whaley ML, Baboyan VG & Tandon N. Category-selectivity in human visual cortex follows cortical topology: A grouped icEEG study. PLoS One 11, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forseth KJ et al. A lexical semantic hub for heteromodal naming in middle fusiform gyrus. Brain 141, 2112–2126 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lerma-Usabiaga G, Carreiras M. & Paz-Alonso PM Converging evidence for functional and structural segregation within the left ventral occipitotemporal cortex in reading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 9981–9990 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brysbaert M. & New B. Moving beyond Kučera and Francis: A critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 977–990 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischl B, Sereno MI, Tootell RBH & Dale A. High-resolution inter-subject averaging and a surface-based coordinate system. Hum. Brain Mapp. 8, 272–284 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argall BD, Saad ZS & Beauchamp MS Simplified intersubject averaging on the cortical surface using SUMA. Hum. Brain Mapp. 27, 14–27 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saad ZS & Reynolds RC Suma. Neuroimage 62, 768–773 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller KJ et al. Spectral changes in cortical surface potentials during motor movement. J. Neurosci. 27, 2424–32 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esposito F. et al. Cortex-based inter-subject analysis of iEEG and fMRI data sets: Application to sustained task-related BOLD and gamma responses. Neuroimage 66, 457–468 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conner CR, Chen G, Pieters TA & Tandon N. Category specific spatial dissociations of parallel processes underlying visual naming. Cereb. Cortex 24, 2741–2750 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woolnough O, Forseth KJ, Rollo PS & Tandon N. Uncovering the functional anatomy of the human insula during speech. Elife 8, e53086 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pflugshaupt T. et al. About the role of visual field defects in pure alexia. Brain 132, 1907–1917 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodríguez-López C, Guerrero Molina MP & Martínez Salio A. Pure alexia: two cases and a new neuroanatomical classification. J. Neurol. 265, 436–438 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsapkini K. & Rapp B. The orthography-specific functions of the left fusiform gyrus: Evidence of modality and category specificity. Cortex 46, 185–205 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirshorn EA et al. Decoding and disrupting left midfusiform gyrus activity during word reading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 8162–8167 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mani J. et al. Evidence for a basal temporal visual language center: Cortical stimulation producing pure alexia. Neurology 71, 1621–1627 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouhali F, Bézagu Z, Dehaene S. & Cohen L. A mesial-to-lateral dissociation for orthographic processing in the visual cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 21936–21946 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coltheart M. Are there lexicons? Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A Hum. Exp. Psychol. 57, 1153–1171 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coltheart M, Rastle K, Perry C, Langdon R. & Ziegler J. DRC: A dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychol. Rev. 108, 204–256 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glezer LS, Kim J, Rule J, Jiang X. & Riesenhuber M. Adding Words to the Brain’s Visual Dictionary: Novel Word Learning Selectively Sharpens Orthographic Representations in the VWFA. J. Neurosci. 35, 4965–4972 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor JSH, Davis MH & Rastle K. Mapping visual symbols onto spoken language along the ventral visual stream. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 17723–17728 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norris D. The Bayesian reader: Explaining word recognition as an optimal bayesian decision process. Psychol. Rev. 113, 327–357 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gold JI & Shadlen MN Banburismus and the Brain: Decoding the Relationship between Sensory Stimuli, Decisions, and Reward. Neuron 36, 299–308 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rayner K. & Duffy SA Lexical complexity and fixation times in reading: Effects of word frequency, verb complexity, and lexical ambiguity. Mem. Cognit. 14, 191–201 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rayner K. Visual attention in reading: Eye movements reflect cognitive processes. Mem. Cognit. 5, 443–448 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carreiras M, Perea M. & Grainger J. Effects of orthographic neighborhood in visual word recognition: Cross-task comparisons. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 23, 857–871 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grainger J, Dufau S, Montant M, Ziegler JC & Fagot J. Orthographic Processing in Baboons (Papio papio). Science (80-. ). 336, 245–249 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rice GA & Robinson DO The role of bigram frequency in the perception of words and nonwords. Mem. Cognit. 3, 513–518 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meade G, Grainger J. & Holcomb PJ Task modulates ERP effects of orthographic neighborhood for pseudowords but not words. Neuropsychologia 129, 385–396 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Balota DA, Cortese MJ, Sergent-Marshall SD, Spieler DH & Yap MJ Visual word recognition of single-syllable words. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 133, 283–316 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perry C, Ziegler JC & Zorzi M. Nested incremental modeling in the development of computational theories: The CDP+ model of reading aloud. Psychol. Rev. 114, 273–315 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bar M. et al. Top-down facilitation of visual recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 449–454 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lochy A. et al. Selective visual representation of letters and words in the left ventral occipito-temporal cortex with intracerebral recordings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, E7595–E7604 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thesen T. et al. Sequential then interactive processing of letters and words in the left fusiform gyrus. Nat. Commun. 3, 1284–1288 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang CHC et al. Adaptation of the human visual system to the statistics of letters and line configurations. Neuroimage 120, 428–440 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dehaene S, Cohen L, Morais J. & Kolinsky R. Illiterate to literate: Behavioural and cerebral changes induced by reading acquisition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 234–244 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szwed M, Qiao E, Jobert A, Dehaene S. & Cohen L. Effects of literacy in early visual and occipitotemporal areas of Chinese and French readers. J. Cogn. Neurosci. (2014) doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Agrawal A, Hari KVS & Arun SP Reading Increases the Compositionality of Visual Word Representations. Psychol. Sci. 30, 1707–1723 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lochy A, Van Reybroeck M. & Rossion B. Left cortical specialization for visual letter strings predicts rudimentary knowledge of letter-sound association in preschoolers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 8544–8549 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomas Yeo BT et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 1125–1165 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Devlin JT et al. Susceptibility-induced loss of signal: Comparing PET and fMRI on a semantic task. Neuroimage 11, 589–600 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Borchers S, Himmelbach M, Logothetis N. & Karnath HO Direct electrical stimulation of human cortex-the gold standard for mapping brain functions? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 63–70 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tandon N. Mapping of human language. in Clinical Brain Mapping (eds. Yoshor D. & Mizrahi E) 203–218 (McGraw Hill Education, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Conner CR, Ellmore TM, Pieters TA, Disano MA & Tandon N. Variability of the Relationship between Electrophysiology and BOLD-fMRI across Cortical Regions in Humans. J. Neurosci. 31, 12855–12865 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pieters TA, Conner CR & Tandon N. Recursive grid partitioning on a cortical surface model: an optimized technique for the localization of implanted subdural electrodes. J. Neurosurg. 118, 1086–1097 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tandon N. et al. Analysis of Morbidity and Outcomes Associated With Use of Subdural Grids vs Stereoelectroencephalography in Patients With Intractable Epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. 76, 672–681 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rollo PS, Rollo MJ, Zhu P, Woolnough O. & Tandon N. Oblique Trajectory Angles in Robotic Stereoelectroencephalography. J. Neurosurg. (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cox RW AFNI: Software for Analysis and Visualization of Functional Magnetic Resonance Neuroimages. Comput. Biomed. Res. 29, 162–173 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dale AM, Fischl B. & Sereno MI Cortical Surface-Based Analysis: I. Segmentation and Surface Reconstruction. Neuroimage 9, 179–194 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kleiner M, Brainard D. & Pelli D. What’s new in Psychtoolbox-3? Perception 36, (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Balota DA et al. The English Lexicon Project. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 445–459 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fedorenko E. et al. Neural correlate of the construction of sentence meaning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, E6256–E6262 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Glasser MF et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature 536, 171–178 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yarkoni T, Balota D. & Yap M. Moving beyond Coltheart’s N: A new measure of orthographic similarity. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 15, 971–979 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berry MW, Browne M, Langville AN, Pauca VP & Plemmons RJ Algorithms and applications for approximate nonnegative matrix factorization. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 52, 155–173 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kadipasaoglu CM et al. Development of grouped icEEG for the study of cognitive processing. Front. Psychol. 6, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kadipasaoglu CM et al. Surface-based mixed effects multilevel analysis of grouped human electrocorticography. Neuroimage 101, 215–224 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated from this research are not publicly available due to them containing information non-compliant with HIPAA and the human participants the data were collected from have not consented to their public release. However, they are available on request from the corresponding author.