Abstract

Salmonella typhi is an infectious bacteria that causes typhoid fever and poses a significant risk to human health. The emergence of antibiotic resistance has become a growing concern in the management of this disease. In this work, a structure-based drug design approach was used to identify inhibitors for zinc-dependent metalloamidase LpxC, the enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of lipid A. Using an in silico approach (virtual screening, docking, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations), from a library of 59,000 indole derivatives, we were able to identify promising lead molecules with high binding affinity to the LpxC. Of these, five molecules (compound 435 (CID: 12253558), compound 436 (CID: 122514279), compound 1812 (CID: 90797680), compound 2584 (CID: 57056726), and compound 2545 (CID: 59897361)) have passed all the filtering criteria. This finding was verified by molecular dynamics (MD) simulation as well as post-dynamics free energy calculations. The five compounds that have been identified have shown the most promise compared to other compounds that are already recognized. To further validate the positive outcome of this study, experimental validation and optimization are necessary. These lead compounds may help to develop new antibiotics for antibiotic-resistant Salmonella typhi and improve typhoid fever treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03699-5.

Keywords: ADME, LpxC, MD Simulation, Docking, Toxicity

Introduction

Salmonella typhi, a gram-negative bacteria is the leading cause of typhoid fever. Typhoid fever is more prevalent in low- and middle-income regions of Asia and Africa with mortality rates exceeding >100 in one million people per year. World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated an annual death toll of 11–20 million with an additional cases of 128,000–161,000 (www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/typhoid). This situation has further worsened due to an increase in the number of Salmonella strains that have developed drug resistance to a wide range of antibiotics. It has been discovered that Salmonella is resistant to a number of antibiotics including ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, streptomycin, furazolidone, sulfonamides, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones (Threlfall 2002; Piddock 2002). One of the main aspects of virulence factors produced during Salmonella infection is lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS is a polysaccharide that acts as a permeability barrier to protect the S. typhi like other gram-negative bacterium from antibiotics (Emiola et al. 2014). LPS is composed of three interconnected components, namely the O-antigen, core oligosaccharide domain, and lipid A. O-antigen is the outermost immuno-dominant and highly variable repeating oligosaccharide that is linked to the core oligosaccharide domain, which in turn is anchored to the outer membrane via lipid A (a glucosamine-containing phosphorylated lipid). Apart from its function as a hydrophobic membrane anchor of LPS, lipid A is a strong human immuno-modulator bacterial endotoxin (Zhou and Zhao 2017). In 1983, Takayama and colleagues have elucidated the first complete chemical structure of lipid A from S. typhi (Takayama et al. 1983). Lipid A biosynthesis requires nine conserved enzymes, all of which are essential for the survival of bacterial cells. LpxC is one of those nine distinct enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of lipid A. It is a Zn2+-dependent metalloamidase that catalyzes the release of acetyl group from UDP-(3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl)-N-acetylglucosamine(myr-UDP-GlcN) to form UDP-(3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl))-N-glucosamine and acetate. This reaction is an irreversible one. Importantly, LpxC does not share any sequence homology with other zinc-metallo enzymes, thereby making it an intriguing target for drug design (Raetz et al. 2009; Jackman et al. 2000; Zhou and Barb 2008; Gronow and Brade 2001).Structure elucidation of LpxC from Escherichia coli, Aquifex aeolicus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Yersinia enterocolitica has provided substantial understanding of its catalytic site topology and mechanism. Various reported structural studies have paved the way for the development of novel inhibitors of LpxC (Coggins et al. 2005; Gennadios et al. 2006; Clayton et al. 2013; Mochalkin et al. 2008). Also, a number of LpxC inhibitors (small molecules) with hydroxamate moiety have been synthesized. One such hydroxamate-based inhibitor, L-161,240, which inhibited LpxC from E.coli was found to be inactive against LpxC from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This kind of differential inhibition can be attributed to subtle structural differences of the LpxC enzymes from the two organisms (Mdluli et al. 2006). Hence, it is critical to identify a novel series of inhibitors that are shared by all gram-negative bacteria. Indole derivatives are the active intermediates in a variety of well-known pharmaceutical products. According to 2012 US retail sales, several indole derivatives or pharmaceuticals containing indole moieties were among the top 200 best-selling medications. Our research efforts in this study involved in the screening, docking, and molecular dynamics analyses of indole derivatives against LpxC from S. typhi. The findings of this study will provide crucial information to other researchers and an opportunity to identify the most effective ligands for LpxC.

Materials and methods

Homology modeling and structure validation

The protein, UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase (LpxC) with 305 amino acids in its structure, was obtained from Uniprot (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q8Z9G5/entry) to develop the three-dimensional model structure. Clustal omega server with default settings was used to align the target and template sequences (Sievers and Higgins 2018; Sievers et al. 2011). Protein model for the target sequence was constructed using YASARA (Krieger and Vriend 2014; Krieger et al. 2009)-based Modeller 9.12 suite (Webb and Sali 2014; Fiser and Sali 2003; Sali et al. 1995). The stereo-chemical quality and validation of the generated models were confirmed during the quality check of model geometry using Ramachandran plot and Moprobity server ((Lovell et al. 2003; Carugo and Djinovic-Carugo 2013), ProSA web server (Wiederstein and Sippl 2007), ERRAT (Colovos and Yeates 1993), Verify3D (Eisenberg et al. 1997), and G-factor calculations in PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993; Laskowski et al. 1994).

Ligand library preparation for guided virtual screening and molecular docking

Custom library of Indole derivatives with > 59,000 compounds was downloaded from PubChem database. These compounds were then subjected to Drulito (http://www.niper.gov.in/pi_dev_tools/DruLiToWeb/DruLiTo_index.html) to filter out compounds on the basis of Lipinski rule of five and 7 other filters to get ~ 4,500 compounds. These compounds were then guide screened with YASARA suite (Krieger and Vriend 2014, 2015; Krieger et al. 2009, 2002, 2012, 2004; Naqsh e Zahra at al. 2013) along with two known LpxC inhibitors [LPC-138 (4-[4-(4-aminophenyl)buta-1,3-diyn-1-yl]-N-[(2S,3R)-3-hydroxy-2-methyl-1-nitroso-1-oxobutan-2-yl]benzamide) and L53 (4-[4-(4-aminophenyl)buta-1,3-diyn-1-yl]-N-[(2S,3S)-3-hydroxy-1-nitroso-1-oxobutan-2-yl]benzamide)] (data not shown). YASARA uses the protocol of Autodock Vina (Trott and Olson 2010). Known inhibitors of LpxC were used as benchmark and control to validate the docking methodology. This prepared library was used to screen the top 15 compounds from the pool of 4500 compounds. These 15 compounds were then docked with Salmonella typhi LpxC (StLpxC) homology model to find out the molecule with the most important LpxC binding features based on binding energy, which was then subjected to further analysis. PDBQT format was used to save the files. AutoGrid was used to produce a grid map utilizing the grid box. Grid center measurements were determined as X = − 7.564, Y = − 28.149, and Z = − 32.156. The size of the grid was determined to be 126 points in each of the X, Y, and Z directions with a grid spacing of 0.375Å. A scoring grid calculation was conducted based on the ligand geometry to reduce the computation time. Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) was used to select the best conformers. For each compound, a maximum of 10 conformers were chosen and taken into account. The following parameters were set: 250,000,000 as maximum number of energy assessments, 27,000,000 as maximum number of generations, 1 as maximum number of top individual that automatically survived, 0.02 mutation rate, and 0.8 crossover rate. The remaining docking parameters were left at their default settings, and 8 LGA runs were performed. Both the protein and the ligands were in a rigid state. The binding energy pose with the lowest total was retrieved and linked with the receptor structure so that it may be analyzed in future. In case of docking experiments, except for the number of GA runs (100 runs were set), rest of the parameters remained similar. For each ligand, from the allotted degrees of freedom (DOF), autodock places a cap of 10 DOF. As a result, the software will automatically assign DOF parameters in accordance with the structure of the compound.

ADME and toxicity studies

To determine a lead molecule as a best hit, it is important to analyze their ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination) properties and toxicity levels. For this, SwissADME program (Daina et al. 2017) and ProTox-II program (Banerjee et al. 2018) were used.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

MD simulation studies were carried out to understand the conformational and structural changes that occur during the formation of protein–ligand complexes. These were performed through YASARA, version 20 (Krieger et al. 2009; Krieger and Vriend 2015), with AMBER14 force field (Cornell et al. 1995). The protein–ligand complex was placed in a water box that is 10 Å bigger than each side of the protein. Hydrogen atoms were added to the protein structure at appropriate ionizable groups that are identified according to the computed pKa in relation to the pH simulation. Thus, a hydrogen atom will be added, if the computed pKa is higher than the pH. Following Ewald method (Eisenberg et al. 1997; Cheatham et al. 1995), the pKa is computed to each residue. Subsequently, the structure was then minimized using steepest-descent method followed by simulated annealing. The simulation was performed at pH 7.0 in a 0.9% NaCl solution at 300 K temperature for 100 ns. A cut-off of 7.86 Å was used for van-der-Waals forces and Particle Mesh Ewald algorithm (Essmann et al. 1995) was used for electrostatic forces. A multiple time step of 1.25 and 2.5 fs were used for intra-molecular and inter-molecular forces, respectively.

Results and discussion

Construction and overall structure of S. typhi LpxC

For modeling the LpxC structure, Uniprot sequence: Q8Z9G5 was chosen as the target sequence. The PDB ID: 4MQY structure shares a sequence identity of 98% with the target sequence. The sequence alignment of the target to template sequence is shown in supplementary data Appendix 1. Alignments of target and template sequences are adjusted to avoid gaps in the secondary structure domain. After the side-chains had been built (optimized and fine-tuned), all the newly modeled parts were subjected to a combined steepest descent and simulated annealing minimization, i.e., the backbone atoms of the aligned residues were fixed to avoid potential damage. The original ligand and other molecules in the template structure were kept intact to understand the binding and active site of the newly made 3D structure of LpxC. For a comparative analysis, various web servers such as (PS)2–3.0 (Huang et al. 2015), Modweb (Fiser and Sali 2003), Phyre2 (Kelley et al. 2015), CPHModels-3.0 (Nielsen et al. 2010), and Swiss Model (Waterhouse et al. 2018) were used to model 3D structures of the desired protein. Parameters for the quality assessment of the generated models are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Stereochemical evaluation parameters for StLpxC structure models made by Modeller and different web servers

| Models | Procheck | ERRAT | Verify-3D | ProSA | YASARA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of non-glycine and non-proline residues | No. of proline, glycine and end residues | Residue coverage | Bad contacts | G-factor | Quality factor (%) | 3D-1D Scores > 0.2 (%) |

Z-Score | RMSD | ||||

| Most favored region [A,B,L] | Additionally allowed region [a,b,l,p] | Generously allowed region [~ a, ~ b, ~ l, ~ p] | Dis-allowed region | |||||||||

| YASARA | 251 (92.3%) | 20 (7.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 33 | 305 | 3 | 0.12 | 93.266 | 100 | − 7.05 | 0.375 |

| (PS)2–3.0 | 254 (93.4%) | 17 (6.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 33 | 305 | 1 | 0.02 | 82.8283 | 93.77 | − 7.07 | 0.123 |

| Modweb | 252 (94.0%) | 15 (5.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 32 | 300 | 1 | 0.05 | 84.589 | 99.00 | − 7.11 | 0.125 |

| Phyre2 | 248 (91.2%) | 21 (7.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 33 | 305 | 2 | − 0.05 | 76.0943 | 96.39 | − 7.16 | 0.147 |

| CPHModels-3.0 | 234 (87.3%) | 33 (12.3%) | 0 | 1 (0.4%) | 33 | 301 | 0 | 0.04 | 87.6712 | 99.67 | − 7.16 | 0.520 |

| Swiss Model | 246 (91.8%) | 21 (7.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 36 | 304 | 1 | −0.12 | 97.561 | 98.33 | − 6.94 | 0.063 |

Comparison of the model quality and stereochemistry has guided the selection of the best model. Except Swiss model, none of the web-based servers has supported the inclusion of Zn2+ cofactor. With the help of PROCHECK statistics (92.3% residues in the core favorable region), a good ERRAT quality (93.266), 100% verify-3D score, 0.375 Å Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), and most reliable and high-quality representative 3D structure of StLpxC was obtained from MODELLER. The knowledge-based energy graph calculated by ProSA for the top modeled LpxC is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. The graph shows local model quality by plotting energy as a function of amino acid. As can be seen in the Supplementary Fig. 1, there are two types of lines: thick and thin. The thick line represents the average energy over each 40 residue fragments, while the thin line depicts window size of 10 residues that is seen in the background of the graph. In general, the positive values correspond to erroneous part of the input structure. As can be seen in the graph, majority portion of the top modeled structure has negative values and hence can be considered as the most reliable model for the protein. Ramachandran Plot (Lovell et al. 2003; Carugo and Djinovic-Carugo 2013; Ramachandran et al. 1963) shows the assignment of amino acids on the basis of phi-psi angles (Supplementary Fig. 2). The total number of residues that fall in the favored region and allowed region are 297 (98.0%) and 6 (2.0%), respectively. No outlier residues were present in the model. ModWeb and Swiss Model generated models had stereochemistry and quality that is comparable to that of the MODELLER constructed model. However, incorporation of Zn2+ ion in the structural model (LpxC is a zinc-dependent metalloenzyme) was a feature supported by MODELLER alone, thereby guiding the selection of the most structurally relevant as well as a good quality model. StLpxC 3D structure acquired in this study has the same typical β1–α–α–β2 geometry of LpxC protein with characteristic slight changes accordig to the sequence of the protein.

Virtual screening, toxicity prediction, and molecular interaction

All the indole-based compounds were initially screened using various filter parameters such as Lipinski rule that resulted in 100 compounds with best binding affinity. Then, out of these 100 compounds, fifteen compounds have specifically shown binding to the Zn2+and having best binding affinity and dissociation constants (Table 2). From this, the top five compounds were selected for molecular dynamics simulations for conformational-based studies.

Table 2.

Guided virtual screening of the best five screened natural compounds

| Ligand ID (PubChem ID) | Ligand name | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Dissociation constant (µM) | Contacting residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0435 (CID: 122535858) | 3-Chloro-N-[2-[(E)-3-(hydroxyamino)-3-oxoprop-1-enyl]phenyl]-1H-indole-2-carboxamide | − 9.0010 | 0.25 | L18, M61, L62, H79, I103, F161, T191, F192, G193, F194, D197, I198, C207, G210, A215, H238, K239, D242, H265, Zn306 |

| 0436 (CID:122514279) | 1-Ethyl-N-[2-[(E)-3-(hydroxyamino)-3-oxoprop-1-enyl]phenyl]indole-2-carboxamide | − 9.0010 | 0.25 | L18, M61, L62, C63, H79, I103, F161, T191, F192, G193, F194, D197, I198, C207, G210, A215, H238, K239, D242, H265, Zn306 |

| 1812 (CID:90797680) | 5-Chloro-N-[(2R)-4-(dihydroxyamino)-4-oxo-1-phenylbutan-2-yl]-1H-indole-2-carboxamide | − 8.6920 | 0.40 | L18, M61, L62, C63, E78, H79, I103, F161, T191, F192, G193, F194, I198, C207, G210, S211, C214, A215, V217, H238, K239, D242, H265, Zn306 |

| 2584 (CID:57056726) (CID:57056726) | N-[(2S)-1-Amino-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl]-5-chloro-1H-indole-2-carboxamide | − 8.5170 | 0.57 | L18, M61, L62, C63, H79, I103, F161, T191, F192, G193, I198, C207, G210, S211, C214, A215, V217, H238, K239, D242, H265, Zn306 |

| 2545 (CID:59897361) | 5-Chloro-N-[(2S,3R)-3-hydroxy-4-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl]-1H-indole-2-carboxamide | − 8.4390 | 0.66 | L18, T60, M61, L62, C63, E78, H79, I103, F161, T191, F192, G193, I198, C207, G210, S211, C214, A215, V217, H238, K239, D242, H265, Zn306 |

Simultaneously, these fifteen compounds were checked for their toxicity using online tool named Protox-II (Banerjee et al. 2018). Table 3 shows the results of toxicity prediction. All the best five compounds (435, 436, 1812, 2584, and 2545) were found to be bound to the active site of LpxC (Kalinin and Holl 2016) (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Toxicity prediction results for the selected 5 natural compounds as calculated using online tool ProTox-II (Banerjee et al. 2018)

| No | Natural compound | Predicated LD50 (mg/kg) | Predicted toxicity class | Average similarity (%) | Prediction accuracy (%) | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 435 | 800 | 4 | 47.51 | 54.26 | Hepatotoxicity, Carcinogenicity, Mutagenicity, Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) |

| 2 | 436 | 500 | 4 | 46 | 54.26 | Carcinogenicity, Mutagenicity, Cytotoxicity |

| 3 | 1812 | 200 | 3 | 56.69 | 67.38 | Hepatotoxicity, Immunotoxicity, Mutagenicity |

| 4 | 2584 | 1000 | 4 | 61.82 | 68.07 | None |

| 5 | 2545 | 1600 | 4 | 59.22 | 67.38 | Immunotoxicity |

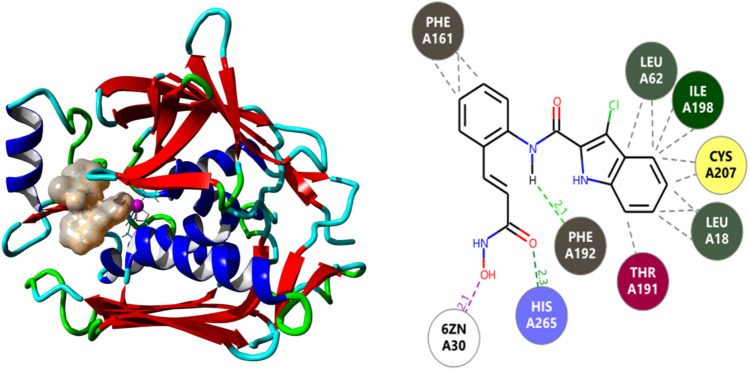

Fig. 1.

The binding site of compound 435 in LpxC and a pictorial two-dimensional representation of its binding interactions with the amino acids. The residues H79, H238, D242, F161, F192, and F194 are located in the active site of LpxC. A basic patch that includes residues K143, K239, K262, and H265 is located close to the active site and plays an important part in the ligand binding process

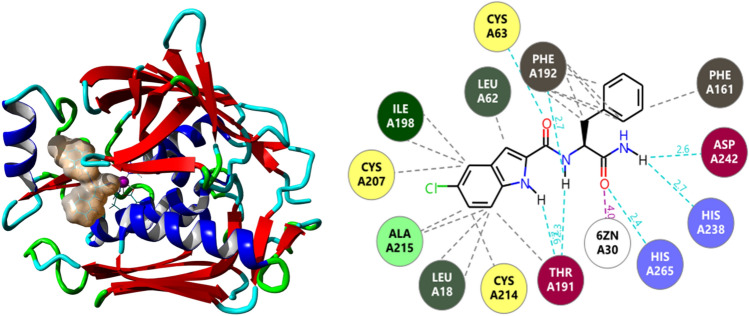

The ADME properties of the five best compounds showed that 2584 is the only one that is non-toxic. Figure 2 represents the compound 2584 binding site in LpxC and two-dimensional image of its interaction with various amino acids (L18, M61, L62, C63, H79, I103, F161, T191, F192, G193, I198, C207, G210, S211, C214, A215, V217, H238, K239, D242, H265) and Zn306 residues.

Fig. 2.

Docking analysis of the complex between StLpxC and compound 2584.Surface image of the bound ligand and secondary model of StLpxC at the active site (left), and a two-dimensional representation (2D) of StLpxC-2584 interactions (right)

The pyrrole ring of compound 2584 facilitates additional space to capture the basic patch of the region adjacent to the active site. This even covers the exit site of the enzyme as well, which restrict the entry and exit of the substrate in the binding pocket of LpxC. Similarly, L18, M61, L62, H79, I103, F161, T191, F192, G193, F194, D197, I198, C207, G210, A215, H238, K239, D242, H265, Zn306 residues make bonded and non-bonded interactions with compound 435.Compounds 435 and 436 are well-known inhibitors of histone deacetylases (HDACs). These enzymes are involved in the removal of acetyl functional groups from the lysine residues of both histone and non-histone proteins. In humans alone, there are 18 types of HDAC enzymes that use either Zinc2+ or NAD + as cofactors to deacetylate the acetyl lysine substrates (Seto and Yoshida 2014; Gallinari et al. 2007). Since the mechanistic action of both LpxC and histone deacetylase is similar, we can speculate that the inhibitors of histone deacetylase (compound 435 and 436) can have the tendency to inhibit LpxC as well. LpxC is very much conserved in Gram-negative bacteria. To cross-check the binding efficacy, the selected 5 compounds were also docked with experimentally solved 3D structures of LpxC enzyme from other species (E.coli (PDB ID:4MQY) (Lee et al. 2014), P.aeruginosa (PDB ID:6CAX) (to be published), A.aeolicus (PDB ID:6IH0) (to be published), Y.enterocolitica (PDB ID:3NZK) (Cole et al. 2011)). The obtained results are tabulated in supplementary Table 1 along with the interaction profiles in supplementary data Appendix 2. In ProTox-II (Banerjee et al. 2018), there are 6 classes for toxicity (1–6). Class 1 has LD50 ≤ 5, which is fatal in nature and on the other hand, class 6 shows LD50 > 5000, which means the compound is non-toxic. Along with these data, physicochemical parameters of the selected 5 compounds are also tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Physicochemical parameters of selected 5 compounds obtained from PubChem (Kim et al. 2016)

| Ligand ID | Name of the indole derivative compound | Structure | Molecular weight (g/mol) | No. of H-bond donors | No. of H-bond acceptors | Log p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0435 | 3-Chloro-N-[2-[(E)-3-(hydroxyamino)-3-oxoprop-1-enyl]phenyl]-1H-indole-2-carboxamide |  |

355.8 | 4 | 3 | 3.1 |

| 0436 | 1-Ethyl-N-[2-[(E)-3-(hydroxyamino)-3-oxoprop-1-enyl]phenyl]indole-2-carboxamidepropyl]benzamide] |  |

349.4 | 3 | 3 | 2.7 |

| 1812 | 5-Chloro-N-[(2R)-4-(dihydroxyamino)-4-oxo-1-phenylbutan-2-yl]-1H-indole-2-carboxamide |  |

387.8 | 4 | 4 | 2.8 |

| 2584 | N-[(2S)-1-Amino-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl]-5-chloro-1H-indole-2-carboxamide |  |

341.8 | 3 | 2 | 3.2 |

| 2545 | 5-Chloro-N-[(2S,3R)-3-hydroxy-4-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl]-1H-indole-2-carboxamide |  |

370.8 | 3 | 3 | 3.4 |

Molecular dynamics simulation

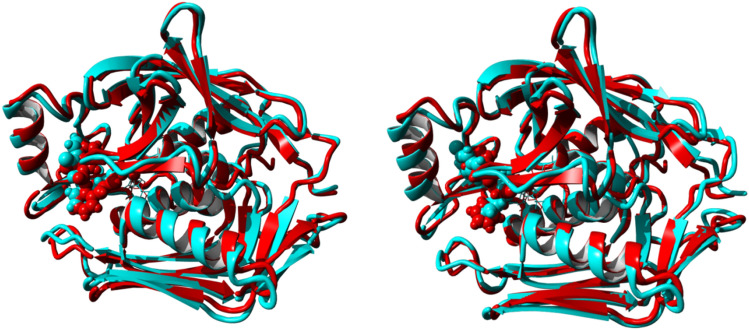

Five protein–ligand complexes obtained from the guided screening of indole derivatives is subjected to molecular dynamics simulation studies using ‘mdrun’ macro of YASARA suite for 100 ns time frame. These simulation studies have provided the information regarding the strength of the interaction and the binding partners that take part in molecular bonding. Figure 3 demonstrates the difference between the initial and final conformations of the protein–ligand complexes (before and after the MD simulation runs) of 100 ns each.

Fig. 3.

Superimpositions of pre-(red) and post-MD simulations (cyan) of three-dimensional structures of LpxC-435 and LpxC-2584 complexes respectively

Initial and final poses are aligned and superimposed to understand the dynamicity of the complex. LpxC-2584 complex has an RMSD of 1.105 Å over 302 aligned residues with 100.00% sequence identity. Similarly, LpxC-435 has an RMSD of 1.198 Å over 302 aligned residues with 100.00% sequence identity. Overall RMSD for C-alpha atom Fig. 4 (left panel) and Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) per residue based in all five complexes are shown in Fig. 4 (right panel).

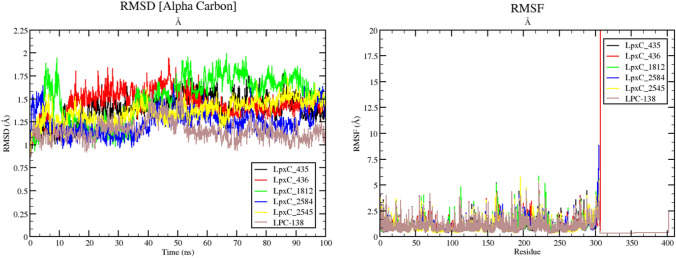

Fig. 4.

RMSD (left panel) calculations in (Å) for C-alpha atom of the protein–ligand complexes in 100 ns. RMSF (right panel) is calculated per residue based to understand the level of fluctuations imparted during the MD simulation

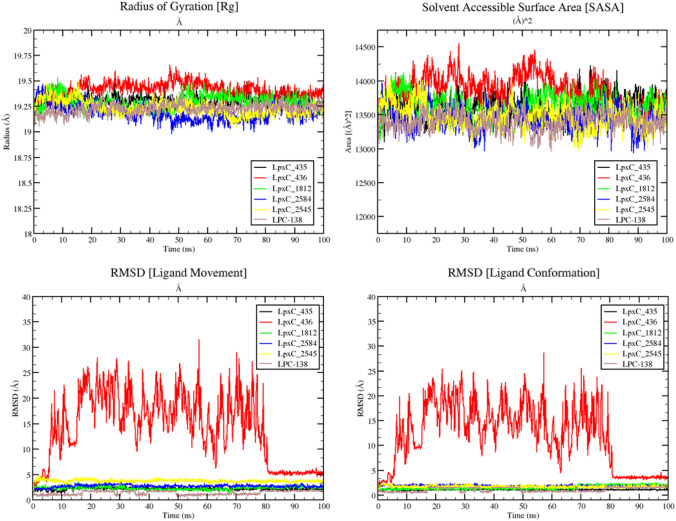

The overall trajectories for LpxC-435(in black) complex have showed least deviation from the starting structure with an average rmsd of ~ 1.5 Å, whereas LpxC-2584 (in blue) complex has showed slight deviation at ~ 90 ns time frame with an average rmsd of ~ 1.25 Å. LpxC-1812 and LpxC-436 complexes have shown higher deviation in the trajectory. Remaining molecules have behaved almost normally in terms of energetics. Fascinatingly, the rmsd of the complexes have never exceeded 2 Å denoting the structural integrity of the protein and complexes as a whole. In case of RMSF graph as well, the fluctuation for LpxC-435 complex (in black) barely has any major spike (once around at residue 191 or 192) (3 Å) and for LpxC-2584 complex (in blue) two major spikes one around/at residue 161 or 162 (3 Å) and near the residue of 191 or 192 (4.5 Å). Rest of the graph shows several minor fluctuating events and finally equilibrated states of RMSF (Fig. 4 right panel). The Radius of Gyration (Rg) fluctuations, Solvant Accessible Surface Area (SASA) values, and RMSD of ligand movement and conformation in their respective complexes during the period of simulation (100 ns) are presented in Fig. 5 (upper left panel) shows the values for radius of gyration (Rg) of the selected protein–ligand complexes.

Fig. 5.

Plots for radius of gyration (upper left), SASA (upper right), RMSD ligand movement (lower left), and RMSD ligand conformation (lower right) for all selected 5 complexes along with one control

Rg denotes the degree of compactness and rigidness of the protein. Greater Rg value indicates higher flexibility and conformation of the protein, whereas lower Rg value denotes more rigidity (Lobanov et al. 2008). We can easily observe that all complexes including the control (LPC-138) has Rg values within the window of 18.9–19.7 Å. This indicates the conformational stability and rigidity of the complex. On top of that, the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) plot (Fig. 5 upper right panel) also demonstrates the closed conformation of the protein with conserved and defined packing (even after ligand binding). The SASA profile of the control (LPC-138) and LpxC-435and LpxC-2584 are very close to each other (with approx. size area of 13,500 (Å)2). Figure 5 lower panels (left and right) show the movement and conformation of protein-bound ligand from its actual docked position and pose during the course of simulation of 100 ns. In LpxC-436 complex, ligand left its binding pocket as soon as the simulation has started. Therefore, we did not take this ligand for the race of best lead compound anymore. Rest of the ligands along with the control (LPC-138) showed static and stable binding in the active site of the LpxC protein (tabulated in Table 5).

Table 5.

Interactions table between enzyme and inhibitors before and after MD simulations

| Complex | Interactions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before MD simulation | After MD simulation | |||||

| Residue | Interaction | Distance | Residue | Interaction | Distance | |

| StLpxC-0435 |

HIS265 PHE192 ALA215 LEU18 CYS207 LEU62 LEU62 ILE198 ILE198 THR191 Zn |

H-bond H-bond Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Unfavorable donor–donor Covalent interaction |

2.34 2.08 4.56 5.10 5.33 4.80 4.84 5.34 4.43 1.34 – |

PHE192 PHE192 PHE192 PHE192 LEU62 ILE198 ILE198 ILE198 LEU201 CYS207 CYS207 CYS207 LEU18 ALA215 THR191 HIS238 ZN |

H-bond H-bond H-bond Pi-Pi stacked Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Sulfur Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl C H-bond C H-bond Covalent interaction |

1.98 1.99 1.88 5.32 4.38 5.15 4.82 4.05 4.74 4.61 5.91 5.40 5.27 4.82 2.61 2.39 – |

| StLpxC-0436 |

PHE192 HIS265 LEU62 LEU62 CYS207 ILE198 LEU18 ALA215 THR191 ZN |

H-bond H-bond Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Unfavorable donor donor Covalent interaction |

2.08 2.34 5.43 4.86 5.33 5.47 4.90 4.41 1.34 - |

– | – | – |

| StLpxC-1812 |

THR191 ASP242 CYS63 PHE192 PHE192 LEU62 LEU62 LEU62 LEU18 CYS214 ALA215 ALA215 CYS207 CYS207 VAL217 ILE198 ILE198 Zn |

H-bond H-bond H-bond H-bond Pi–Pi T C H-bond Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Sulfur Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Covalent interaction |

2.11 2.76 2.88 2.33 4.92 2.58 4.71 5.33 4.71 5.62 3.84 4.03 5.21 4.61 5.22 3.66 5.30 – |

LEU62 GLU78 PHE192 LEU62 LEU62 HIS163 LYS239 HIS238 CYS63 CYS63 CYS214 LEU18 ALA215 ALA215 ALA215 ZN |

H-bond H-bond H-bond Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi–Pi stacked Pi-cation C H-bond Pi-Sulfur Pi-Sulfur Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Covalent interaction |

2.58 2.99 2.24 4.23 4.75 4.97 4.88 2.90 5.73 5.90 4.46 5.37 3.90 4.03 4.95 – |

| StLpxC-2584 |

PHE192 PHE192 HIS265 ASP242 LEU62 LEU62 ALA215 ALA215 ALA215 CYS214 CYS207 CYS207 VAL217 ILE198 ILE198 LEU18 LEU18 ZN |

H-bond Pi–Pi stacked H-bond H-bond C H-bond Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Sulfur Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Unfavorable metal donor |

2.69 4.73 2.40 2.63 2.39 4.74 4.94 3.61 4.06 5.25 5.12 4.86 4.94 3.62 5.19 4.65 5.30 1.72 |

PHE192 PHE192 LEU62 CYS207 CYS207 CYS207 ALA215 LEU201 ILE198 ILE198 GLU78 ASP242 LYS239 ZN |

H-Bond H-Bond Pi-Alkyl Pi-Sulfur Pi-Sulfur Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Attractive Charge Attractive Charge Pi-sigma Covalent interaction |

2.44 1.85 4.63 5.85 5.71 4.76 4.23 5.29 5.06 4.58 4.27 4.73 2.77 – |

| StLpxC-2545 |

PHE192 PHE192 PHE161 CYS63 LEU18 CYS214 ALA215 ALA215 ALA215 VAL217 CYS207 CYS207 ILE198 ILE198 LEU62 LEU62 ZN ZN |

H-Bond Pi–Pi stacked Pi–Pi T C–H bond Pi-Alkyl Pi-Sulfur Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Metal acceptor Unfavorable metal donor |

3.07 4.89 5.72 2.28 4.68 5.43 5.04 3.73 4.18 5.23 5.14 4.57 3.63 5.21 5.45 4.81 3.38 2.37 |

THR191 THR191 ALA215 ILE198 ILE198 VAL217 PHE212 CYS207 GLU78 HIS79 ZN |

H-Bond H-Bond Pi-Alkyl Pi-Alkyl Alkyl Alkyl Alkyl Pi-Sulfur C H-bond C H-bond VanderWaals |

1.90 1.96 4.57 5.07 4.69 4.99 3.37 5.98 2.80 2.32 – |

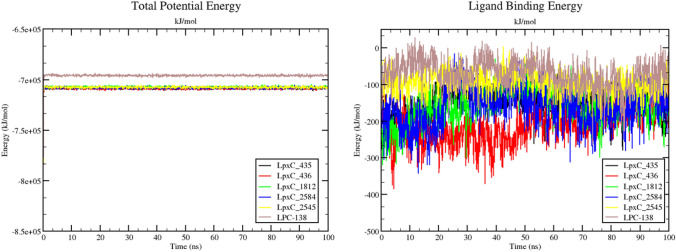

Ligand 435 being very close to the control molecule and showed its potency to be developed into a lead potent inhibitor of LpxC, which may pass the clinical trials too. The obtained MD simulation results are based on total potential energy (which forms by combining different energy contributors like Bond, Angle, Dihedral, Planarity, Coulomb, VdW to make up the total potential energy) for all the 5 complexes (along with the control complex) suggested that upon ligand binding, there were no significant deviations or conformational changes in the protein structure (Fig. 6 (left panel)).

Fig. 6.

Total potential energy of all five different complexes along with the control molecule LPC-138

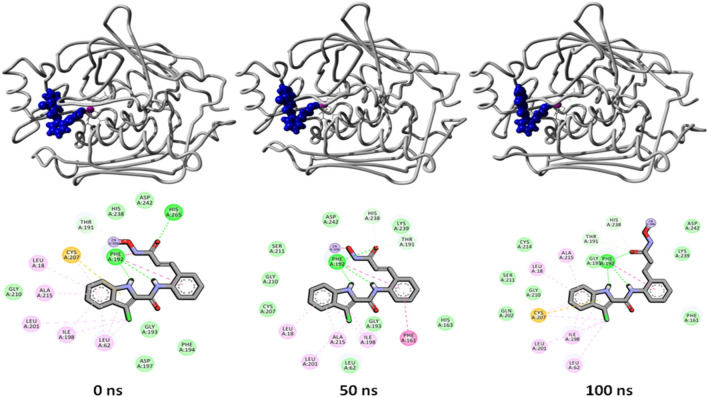

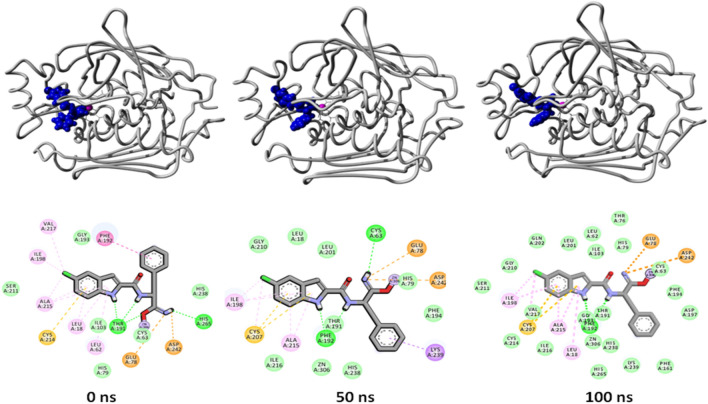

Potential energy for the five complexes is a little better than the potential energy of the control complex indicating better binding of the ligand (Fig. 6 right panel). LpxC-435 and LpxC-2584 complexes (overlapping) have displayed the lowest static ligand binding energy for the whole 100 ns simulation period (-200 kJ/mol).To understand the change and binding stability in the ligand-docked complexes, we studied the conformational change of LpxC-435 and LpxC-2584 complexes at 3 different time intervals (0 ns, 50 ns, and 100 ns). Figures 7 and 8 shows the overall structure of LpxC in association with compound 435 and 2584, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Binding interactions between compound 435 and LpxC protein at different time intervals (0 ns, 50 ns, and 100 ns, respectively) of the MD simulation run. Colour scheme of 2D binding profile is same as Fig. 4 and 5

Fig. 8.

Binding interactions between compound 2584 and LpxC protein at different time intervals (0 ns, 50 ns and 100 ns, respectively) of 100 ns MD simulation run

From the images, it can be observed that there is a change in the binding partner residues that can be easily observed. Slight difference in the surface view of the complex can also be seen in the upper panels of both the figures (Figs. 7 and 9). These slight changes suggest that both the ligands are persistent in their binding inside the active site (as validated with the ligand binding energy score). With these results, we can speculate the potent role of these two compounds in the inhibitory studies of LpxC enzyme after further development and various in vitro and in vivo experimentation. Out of these two compounds, 435 showed certain toxicity as compared to 2584, which did not show any toxicity. Hence, there is an enormous room in the further development of 2584 as a working inhibitor of LpxC enzyme. The comparative structural analysis suggests that both ligand 2584 and the hydroxamate inhibitor have common binding pocket in LpxC (Fig. 9).

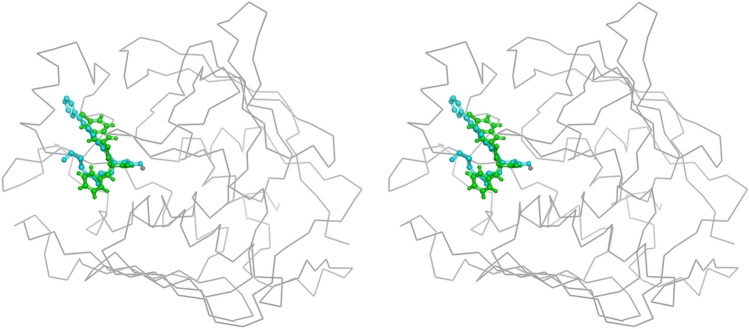

Fig. 9.

Superimposed stereo view of ligand 2584(Green color) and the hydroxamate (Cyan color) inhibitors both bind to LpxC

Importantly, ligand 2584 and hydroxamate share the common inter-molecular interactions because they both occupy the UDP pocket in the LpxC structure. Hydroxamate inhibitors and ligand 2584 are bound with LpxC with at least 5 hydrogen bonds along with strong coordination with zinc ions at the binding site. Both the inhibitors are well placed in the pocket having non-polar rings superimposed in the non-polar environments in the UDP pocket. The residues involved in hydrogen bonding interactions with ligands are M61, T191, F192, D242, and H265, respectively. The binding of ligand 2584 and the hydroxamate inhibitor are comparable in nature.

Conclusion

Antibiotics has changed the modern medicine and helped to save the millions of lives. However, they are becoming less effective because of the fast spreading of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. So, it is of importance to identify new targets and approaches to produce inhibitors to control these AMR (Singh et al. 2002; Singh et al. 2022; Purohit et al. 2008).The principal cause of typhoid, and Salmonella typhi has also evolved into an opportunistic lethal multi-drug-resistant infection, needing the development of new chemical drugs to treat it. The metalloamidase from S. typhi of LpxC did not reveal any structural resemblance to any known human metallo-amidase. It has been concluded that it is a promising target, and the purpose of this research is to identify new compounds that have the potential to serve as novel inhibitors for the purpose of efficiently controlling this pathogenic organism. There are two domains in the overall structure of S. typhi of LpxC. The first is Domain I, and the second is Domain II. Domain II of insert II has a substrate binding site, which is the target location where majority of known inhibitors of LpxC interact and slow down the enzyme's activity. A total of 59,000 indole derivatives were identified and filtered using Lipinski rule of five and seven additional filters to yield about 4500 compounds to screen against LpxC. After virtual screening, docking, and MD simulation studies, the five best compounds against LpxC were found to be 435, 436, 1812, 2584, and 2545, respectively. Docking studies of these compounds showed that these molecules could bind to the active site of different LpxC enzymes. All the 5 compounds were bound to the active site and MD simulation evaluates for 100 ns has revealed that the LpxC-435 and LpxC-2584 complexes have exhibited the lowest static ligand binding energy (− 200 kJ/mol). Toxicity studies have suggested that 2584 is non-toxic and has significant potential for further development as an inhibitor of the LpxC enzyme. The indole derivative 2584 has been identified as the primary molecule capable of destroying the lethal organism if synthesized and utilized.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Sudhir Kumar Pal [project id: BMI/11(30)/2020] and Sanjit Kumar acknowledge the financial assistance from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) (IRIS ID: 2019-14004). We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Kali Kishore Reddy Tetala, Dr. Mukesh Kumar and Debasish Roy for their informative and insightful comments regarding the work.

Data availability

Data available on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All co-authors have agreed to submit the manuscript to the journal. The findings have not been published elsewhere. The manuscript is not currently under consideration by another journal. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Banerjee P, Eckert AO, Schrey AK, Preissner R. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W257–W263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carugo O, Djinovic-Carugo K. Half a century of Ramachandran plots. Acta Crystallogr. 2013;69:1333–1341. doi: 10.1107/S090744491301158X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham TI, Miller JL, Fox T, Darden TA, Kollman PA. Molecular dynamics simulations on solvated biomolecular systems: the particle mesh Ewald method leads to stable trajectories of DNA, RNA, and proteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1995;117(14):4193–4. doi: 10.1021/ja00119a045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton GM, Klein DJ, Rickert KW, Patel SB, Kornienko M, Zugay-Murphy J, Reid JC, Tummala S, Sharma S, Singh SB, Miesel L. Structure of the bacterial deacetylase LpxC bound to the nucleotide reaction product reveals mechanisms of oxyanion stabilization and proton transfer. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(47):34073–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.513028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggins BE, McClerren AL, Jiang L, Li X, Rudolph J, Hindsgaul O, Raetz CR, Zhou P. Refined Solution Structure of the LpxC− TU-514 Complex and p K a analysis of an active site histidine: insights into the mechanism and inhibitor design. Biochemistry. 2005;44(4):1114–26. doi: 10.1021/bi047820z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole KE, Gattis SG, Angell HD, Fierke CA, Christianson DW. Structure of the metal-dependent deacetylase LpxC from Yersinia enterocolitica complexed with the potent inhibitor CHIR-090. Biochemistry. 2011;50:258–265. doi: 10.1021/bi101622a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colovos C, Yeates TO. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1511–1519. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell WD, Cieplak P, Bayly CI, Gould IR, Merz KM, Ferguson DM, Spellmeyer DC, Fox T, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117(19):5179–97. doi: 10.1021/ja00124a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Lüthy R, Bowie JU. VERIFY3D: assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Meth Enzymol. 1997;277:396–404. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)77022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emiola A, George J, Andrews SS. A complete pathway model for lipid A biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE. 2014;10:e0121216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LG. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103(19):8577–93. doi: 10.1063/1.470117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser A, Sali A. Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Meth Enzymol. 2003;374:461–491. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallinari P, Di Marco S, Jones P, Pallaoro M, Steinkühler C. HDACs, histone deacetylation and gene transcription: from molecular biology to cancer therapeutics. Cell Res. 2007;17:195–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennadios HA, Whittington DA, Li X, Fierke CA, Christianson DW. Mechanistic inferences from the binding of ligands to LpxC, a Metal-Dependent Deacetylase. Biochemistry. 2006;45(26):7940–8. doi: 10.1021/bi060823m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronow S, Brade H. Invited review: Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis: which steps do bacteria need to survive? J Endotox Res. 2001;7(1):3–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T-T, Hwang J-K, Chen C-H, Chu C-S, Lee C-W, Chen C-C. (PS)2: protein structure prediction server version 3.0. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:338–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman JE, Fierke CA, Tumey LN, Pirrung M, Uchiyama T, Tahir SH, Hindsgaul O, Raetz CR. Antibacterial Agents That Target Lipid A Biosynthesis in Gram-negative Bacteria: Inhibition of diverse UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylases by substrate analogs containing zinc binding motifs. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(15):11002–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinin DV, Holl R. Insights into the Zinc-Dependent Deacetylase LpxC: Biochemical Properties and Inhibitor Design. Curr Top Med Chem. 2016;16:2379–2430. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160413135835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Thiessen PA, Bolton EE, Chen J, Fu G, Gindulyte A, Han L, He J, He S, Shoemaker BA, Wang J, Yu B, Zhang J, Bryant SH. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1202–D1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger E, Vriend G. YASARA View - molecular graphics for all devices - from smartphones to workstations. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2981–2982. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger E, Vriend G. New ways to boost molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 2015;36:996–1007. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger E, Koraimann G, Vriend G. Increasing the precision of comparative models with YASARA NOVA–a self-parameterizing force field. Proteins. 2002;47:393–402. doi: 10.1002/prot.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger E, Darden T, Nabuurs SB, Finkelstein A, Vriend G. Making optimal use of empirical energy functions: force-field parameterization in crystal space. Proteins. 2004;57:678–683. doi: 10.1002/prot.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger E, Nielsen JE, Spronk CA, Vriend G. Fast empirical pKa prediction by Ewald summation. J Mol Graph Model. 2006;25(4):481–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger E, Joo K, Lee J, Lee J, Raman S, Thompson J, Tyka M, Baker D, Karplus K. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins. 2009;77(Suppl 9):114–122. doi: 10.1002/prot.22570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger E, Dunbrack RL, Hooft RWW, Krieger B. Assignment of protonation states in proteins and ligands: combining pKa prediction with hydrogen bonding network optimization. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;819:405–421. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-465-0_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. Journal of applied crystallography. 1993;26(2):283–91. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Smith DK, Jones DT, Hutchinson EG, Morris AL, Naylor D, Moss DS, Thornton JM (1994) PROCHECK v. 3.0. Program to Check the Stereochemistry Quality of Protein Structures. Operating Instructions..

- Lee C-J, Liang X, Gopalaswamy R, Najeeb J, Ark ED, Toone EJ, Zhou P. Structural basis of the promiscuous inhibitor susceptibility of Escherichia coli LpxC. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:237–246. doi: 10.1021/cb400067g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobanov MY, Bogatyreva NS, Galzitskaya OV. Radius of gyration as an indicator of protein structure compactness. Mol Biol. 2008;42:623–628. doi: 10.1134/S0026893308040195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB, de Bakker PIW, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Structure validation by Calpha geometry: phi, psi and Cbeta deviation. Proteins. 2003;50:437–450. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mdluli KE, Witte PR, Kline T, Barb AW, Erwin AL, Mansfield BE, McClerren AL, Pirrung MC, Tumey LN, Warrener P, Raetz CR. Molecular validation of LpxC as an antibacterial drug target in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(6):2178–84. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00140-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochalkin I, Knafels JD, Lightle S. Crystal structure of LpxC from Pseudomonas aeruginosa complexed with the potent BB-78485 inhibitor. Protein Sci. 2008;17(3):450–7. doi: 10.1110/ps.073324108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqsh-e-Zahra S, Khattak NA, Mir A. Comparative modeling and docking studies of p16ink4/cyclin D1/Rb pathway genes in lung cancer revealed functionally interactive residue of RB1 and its functional partner E2F1. Theor Biol Med Model. 2013;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Lund O, Petersen TN. CPHmodels-3.0–remote homology modeling using structure-guided sequence profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W576–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piddock LJ. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella serovars isolated from humans and food animals. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26(1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper U, Webb BM, Dong GQ, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Fan H, Kim SJ, Khuri N, Spill YG, Weinkam P, Hammel M, Tainer JA. ModBase, a database of annotated comparative protein structure models and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(11):D336–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit R, Rajasekaran R, Sudandiradoss C, George C, Ramanathan K, Rao S. Studies on flexibility and binding affinity of Asp25 of HIV-1 protease mutants. Int J Biol Macromol. 2008;42:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raetz CR, Guan Z, Ingram BO, Six DA, Song F, Wang X, Zhao J. Discovery of new biosynthetic pathways: the lipid A story. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:S103–8. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800060-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran GN, Ramakrishnan C, Sasisekharan V. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J Mol Biol. 1963;7:95–99. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(63)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Potterton L, Yuan F, van Vlijmen H, Karplus M. Evaluation of comparative protein modeling by MODELLER. Proteins. 1995;23:318–326. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto E, Yoshida M. Erasers of histone acetylation: the histone deacetylase enzymes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014;6:a018713. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Higgins DG. Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein Sci. 2018;27:135–145. doi: 10.1002/pro.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Bhardwaj VK, Das P, Purohit R. Identification of 11β-HSD1 inhibitors through enhanced sampling methods. Chem Commun. 2022;58:5005–5008. doi: 10.1039/d1cc06894f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Kumar S, Bhardwaj VK, Purohit R. Screening and reckoning of potential therapeutic agents against DprE1 protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Liq. 2022;358:119101. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama K, Qureshi N, Mascagni P. Complete structure of lipid A obtained from the lipopolysaccharides of the heptoseless mutant of Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1983;258(21):12801–3. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)44040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfall EJ. Antimicrobial drug resistance in Salmonella: problems and perspectives in food-and water-borne infections. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26(2):141–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R, Heer FT, de Beer TAP, Rempfer C, Bordoli L, Lepore R, Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P, Barb AW. Mechanism and inhibition of LpxC: an essential zinc-dependent deacetylase of bacterial lipid A synthesis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2008;9(1):9–15. doi: 10.2174/138920108783497668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P, Zhao J. Structure, inhibition, and regulation of essential lipid A enzymes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2017;1862(11):1424–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.