Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI)/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are lung complications diagnosed by impaired gaseous exchanges leading to mortality. From the diverse etiologies, sepsis is a prominent contributor to ALI/ARDS. In the present study, we retrieved sepsis-induced ARDS mRNA expression profile and identified 883 differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Next, we established an ARDS-specific weighted gene co-expression network (WGCN) and picked the blue module as our hub module based on highly correlated network properties. Later we subjected all hub module DEGs to form an ARDS-specific 3-node feed-forward loop (FFL) whose highest-order subnetwork motif revealed one TF (STAT6), one miRNA (miR-34a-5p), and one mRNA (TLR6). Thereafter, we screened a natural product library and identified three lead molecules that showed promising binding affinity against TLR6. We then performed molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate the stability and binding free energy of the TLR6-lead molecule complexes. Our results suggest these lead molecules may be potential therapeutic candidates for treating sepsis-induced ALI/ARDS. In-silico studies on clinical datasets for sepsis-induced ARDS indicate a possible positive interaction between miR-34a and TLR6 and an antagonizing effect on STAT6 to promote inflammation. Also, the translational study on septic mice lungs by IHC staining reveals a hike in the expression of TLR6. We report here that miR-34a actively augments the effect of sepsis on lung epithelial cell apoptosis. This study suggests that miR-34a promotes TLR6 to heighten inflammation in sepsis-induced ALI/ARDS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03700-1.

Keywords: ARDS, TLR6, WGCNA, FFL, MD simulation

Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI)/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are inflammatory lung complications inflicting a significant impact on longevity (Bersten et al. 2002; Kim and Hong 2016). The incidence and mortality of ALI/ARDS vary worldwide, ranging between 20 and 40% (Pham and Rubenfeld 2017; Schissel and Levy 2006; Sigurdsson et al. 2013). ALI/ARDS is also being reported as a leading cause of fatality in the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus two infections resulting in COVID-19 illness (Yang et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2021) with incidence rate and mortality rate in COVID-19 associated ARDS (Denson et al. 2021, p. 19; Tzotzos et al. 2020). ALI/ARDS is manifested by acutely reduced respiratory capacity leading to severe hypoxemia (Schissel and Levy 2006). Diffused alveolar damage is one of the hallmarks of ARDS, marked by compromised barrier function, vascular permeability with an accumulation of protein-rich edema and increased lung weight which ensues in reduced gas exchanges and lung compliance (Cardinal-Fernández et al. 2017; Englert et al. 2019). The onset of ARDS is multifactorial; however, it may be categorized as pulmonary (e.g., pneumonia, aspiration) and extrapulmonary (e.g., sepsis) (Raghavendran and Napolitano 2011). Sepsis is a majorly contributing etiology to ARDS incidence (Wang et al. 2021), with a mortality rate of observed in a retrospective study (Bellani et al. 2016; Mikkelsen et al. 2013). Sepsis-induced ARDS shows lower PaO2/FiO2 ratios, thus deteriorating respiratory function (Hu et al. 2020). ARDS induced by sepsis exhibits a hike in inflammation wherein macrophages dynamically switch phenotypes towards a pro-inflammatory state, thereby promoting a cascade of signaling expressing cytokines, such as TNF-, IL1-, and IL-6 (Matthay et al. 2012). Macrophages express TLRs actively on their surface membranes for distinguished ligands like PAMP’s and DAMP’s (Billack 2006; Grassin-Delyle et al. 2020). TLRs are extensively studied receptors, well known for recognizing infectious microbial PAMP ligands (Newton and Dixit 2012). However, a continuous provocation to inflammation in sepsis is aided by non-infectious endogenous ligands generated host tissue damage (Gentile and Moldawer 2013; Roh and Sohn 2018). Excessive neutrophil infiltration at the site and distant (lungs) from the site of infection is observed in sepsis (Grommes and Soehnlein 2011). This neutrophil condition becomes detrimental to the host tissue due to the release of enzymes (Ginzberg et al. 2001). The damaged host tissue causes the release of endogenous DAMP ligands (Gentile and Moldawer 2013; Ginzberg et al. 2001; Roh and Sohn 2018). The systemic inflammatory response in sepsis is actively triggered by DAMPs like high mobility group box-1 (HMGB-1), host proteins, histones, extracellular cold-inducible RNA binding protein (eCIRP), ATP, HSPs, fibrinogens, which are released post tissue injury or senescence (Denning et al. 2019; Gentile and Moldawer 2013; Schaefer 2014; Sohn et al. 2012, p. 4). DAMPs ardently initiate different TLR signaling pathways in immune cells (Zhang and Mosser 2008). Infection triggers macrophages to polarize to either phenotype to attain homeostasis. This process is efficiently regulated by microRNAs (miRNAs), which get differentially expressed in specific conditions (Curtale et al. 2019). miRNAs are nt long short chain oligonucleotides that bind to the 3′UTR of the messenger RNA (mRNA) via seed region (Bartel 2009), leading to mRNA decay by de-adenylation in RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Ha and Kim 2014; Huntzinger and Izaurralde 2011). In this way miRNAs regulate diverse processes like cell division and differentiation, senescence, inflammation, and homeostasis by regulating the mRNA concentrations (O’Brien et al. 2018). TLR signaling is actively modulated by miRNAs either by regulating the expression of TLR receptors or the downstream adapter molecules (Arenas-Padilla and Mata-Haro 2018).miRNAs are reported to regulate different genes in sepsis (Szilágyi et al. 2019). miRNAs are swiftly dysregulated in ALI/ARDS and sepsis (Cao et al. 2016; Ferruelo et al. 2018; Jiang et al. 2020). miR-34a is one such miRNA associated and prominently upregulated in sepsis inflammation (Abdelaleem et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2020; Goodwin et al. 2015; Oteiza et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2020, p. 1). miR-34a is widely allied with promoting inflammation and senescence (Bai et al. 2011; Chafik 2018; Chang et al. 2007; Khan et al. 2020, p. 4; Long et al. 2018; Mohan et al. 2015; Navarro and Lieberman 2015; Syed et al. 2017; Velasco-Torres et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2016). Experimental data of ALI/ARDS depicts a significant analogy between miR-34a and lung inflammation (Chen et al. 2020; Cheng et al. 2018, p. 3; Cui et al. 2017; Du et al. 2012; Khan et al. 2020). miR-34a also polarize macrophage to M1 phenotypes by downregulating anti-inflammatory genes such as KLF4, SIRT1, and Notch (Chen et al. 2020; Khan et al. 2020; Yamakuchi et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2015). STAT6, which IL4 strongly induces, is significantly associated with the anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype (Gong et al. 2017; Li et al. 2020; Nepal et al. 2019; Tugal et al. 2013; Yu et al. 2019, p. 24). Contrary to this, TLR6 in conjugation with TLR2, forms a heterodimer receptor for the DAMPs arising due to host tissue damage continuously promotes inflammation (Eckmann 2006; Oliveira-Nascimento et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2019). Unlike sepsis or ARDS alone, sepsis-induced ARDS is a life-threatening condition broadly characterized by lung edema leading to severe hypoxemia. In sepsis-induced ARDS, miR-34a promotes TLR6 expression, conjugating with TLR2 forming an active receptor for the non-infectious endogenous ligands which continuously triggers TLR2-TLR6 signaling resulting in uncontrolled inflammation and organ dysfunction.

Our study primarily extracted mRNA microarray dataset of sepsis-induced ARDS and identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs). These DEGs were subjected to a weighted gene co-expression (WGCN) construction followed by trait-linked hub module detection. ARDS-specific 3-node miRNA feed-forward loop (FFL) gave us an insight into key miRNAs, transcription factors (TFs), and the highest degree subnetwork motif comprising miR-34a-5p, STAT6, and TLR6. Afterwards, we employed the molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) method against TLR6 to discover potential hits for ARDS which was further validated utilizing MD simulation and MM_PBSA studies. Cecal ligation puncture (CLP)-induced sepsis in mice showed a spike in the expression of miR-34a, which was also observed in-vitro. Overexpression strategies were adopted by using miR-34a mimic in-vivo, which showed a considerable deterioration of the lung injury symptoms. Contrary to this miR-34a inhibitors alleviated the lung injury symptoms and enhanced the expression of STAT6. miR-34a was found to be positively regulating TLR6, simultaneously antagonizing STAT6. Our experimental data permits us to suggest miR-34a as a probable therapeutic target in dealing with the menace of sepsis-induced ARDS. The novelty of our work lies in the microarray data extraction, extrapolation of trait-linked hub genes and FFL analysis to understand the complex molecular mechanism and signaling pathways associated with sepsis and ARDS.

Materials and methods

ARDS-specific expression profile collection and differential expression analysis

We accessed the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)-Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (Clough and Barrett 2016) for obtaining the ARDS-associated mRNA expression profile with “acute respiratory distress syndrome” and “ARDS” being utilized as suitable keywords. The search results were further trimmed down as per the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned in the supplementary methods section. Processed expression file (i.e., series matrix) of the selected dataset was downloaded, and probe ID mapping to their equivalent HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) symbol(s) was performed utilizing the official sequencing platform library-based Bioconductor package followed by duplicate genes removal. Only officially approved HGNC symbols were retained as per the HGNC multi-symbol checker (https://www.genenames.org/tools/multi-symbol-checker/). A two-sample unpaired t test assisted in computing the p value and values of each gene across two patient groups via limma (Ritchie et al. 2015). and was set as the threshold for identification of DEGs. Lastly, Pigengene package (Foroushani et al. 2017) was utilized to remove any outlying or noisy DEGs.

ARDS-specific WGCN formation and hub module detection

We utilized the WGCNA package (Langfelder and Horvath 2008; Zhang and Horvath 2005) to establish an ARDS-specific WGCN and identify significant modules having a high correlation with age. The process of WGCN formation is discussed in supplementary methods section. The dynamic tree-cut algorithm was applied to find modules from the dendrogram branches. For possible merging of any modules with highly co-expressed gene patterns, module eigengene (ME) and dissimilarity measures between MEs (MEdiss) were taken into account. Any modules with alike expression profiles were merged by observing the ME dendrogram based on Pearson correlation. Module membership (MM) (i.e., correlation between ME and gene expression profile), standard intramodular connectivity (k.in) and average gene significance (GS) of genes in a given module were computed for all modules. The supplementary methods section discusses the criteria for selecting the hub module and their genes.

ARDS-specific 3-node miRNA-mRNA-TF network construction & topological analysis

ChEA v3.0 database (Keenan et al. 2019) was queried for obtaining significant () human TFs interacting with ARDS-specific hub genes. The miRNAs relating to ARDS-specific hub genes and TFs (compiled from ChEA) were acquired from the miRWalk v3.0 database (Sticht et al. 2018). The process of picking miRNAs and FFL formation is discussed in supplementary methods section. The FFL’s topological properties were analyzed utilizing NetworkAnalyzer and CytoNCA Cytoscape plugins. The topological properties of the network are described by measurements of degree distribution ), clustering coefficient (), neighborhood connectivity (), betweenness (), closeness () and topological coefficient (. We utilized these parameters to explain topological changes when the network is perturbed.

Preparation of the natural product database

The natural product library containing compounds was selected from the MEGxp database, one of the most extensive NP chemical libraries available (AnalytiCon Discovery) for our high-throughput screening targeting the TIR domain of TLR6. These compounds were downloaded in “SDF format” and then converted to three-dimensional (3D) utilizing prepared ligand molecules in Biovia DS 2020.

Docking-based screening and MD simulation studies

A collection of natural compounds from MEGxp database (https://ac-discovery.com) was screened to rapidly discover novel drug candidates against the TLR6 protein of TIR domain (PDB ID:4OM7) (Jang and Park 2014). The primary docking screening was carried out utilizing the LibDock program followed by CDOCKER docking module of Discovery Studio 2020. The predocking strategy; preparation of ligands and protein, filtration of compounds based on drug like properties, and binding site identification were performed as previously described (Jha et al. 2022b). Following the virtual screening of potential drug candidates, a MD simulation using the Gromos96 43a1 force field parameters was run using the GROMACS 2019 software at constant temperature and pressure using an earlier protocol (Jha et al. 2022a, p. 2).

Molecular mechanics/Poisson‐Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) binding free energy calculation

Binding free energies of all three drug-target complexes were computed via the MM/PBSA method utilizing the g_mmpbsa tool from last stable trajectories (Kumari et al. 2014). The MM/PBSA calculation utilized the following equation:

where represents the total binding energy of the drug‐target complex, Greceptor denotes the binding energy of free receptor, and Gligand stands for the binding energy of unbound ligand.

Materials

Rabbit monoclonal anti-TLR6 from Abbkine, and mouse monoclonal anti-STAT6 from Biolegend, were employed for antigen detection. HRP-conjugate anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology were utilized. Merck's hematoxylin and Eosin were used to stain the mice’s lung section and check morphological changes. miR-34a inhibitors, mimics, and scramble were purchased from Qiagen.

Cecal ligation puncture model to induce ALI

C57BL/6 mice weighing 18–22 g and aged six to eight weeks were used. Pathogen-free environment with proper lighting conditions along with food and water ad-libitum. Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Government of India, followed guidelines to conduct the study with ethical approvals (File Number: 1358). Ketamine (100 mg/kg) and Xylazine (10 mg/kg) were administered to induce anesthesia in mice. miR-34a mimic and inhibitor and scramble are given at a concentration of 2 mg/kg body weight intraperitoneally. An 18-gauge needle was used to puncture the caecum already ligated at a 3/4 length from the terminal end. Through and through puncture was done induce infection in mice.

Histopathological analyses

Lungs harvested from CLP-induced septic mice were initially fixed in a neutral buffered formalin solution from Sigma and later embedded with paraffine. thick sections are subjected to standard IHC protocol. TLR6 and STAT6 primary antibodies were utilized to probe the presence of respective antigens. Later, HRP conjugate universal secondary antibody from Vector Labs is used for respective primary antibody. DAB is utilized as a substrate for the HRP, and positively stained cells was visualized under light microscope (MEZI, Japan).

Statistical analyses

Two way-ANOVA was applied to check for the statistical significance of the quantified data. Mean values were considered with a .

Results

ARDS-specific mRNA expression profile retrieval and differential expression analysis

The supplementary results section mentions the selected dataset's details and preprocessing. A total of DEGs were identified corresponding to and . We were left with DEGs after eliminating noise/outliers. A 2D volcano plot showing an overview of significant (up versus downregulated) and nonsignificant genes in the GSE66890 dataset was shown in Supplementary Figure S1A. Supplementary Figure S1B shows the expression-based heatmap of top up and downregulated ARDS-specific DEGs. Among these DEGs, MME [ and OLFM4 [] were the most up and downregulated ones. The age of samples varied from to , with the maximum patients aged , , and . Among all the samples, were constituted by females, by males, and by other gender. Supplementary Figure S1C shows the principal component analysis (PCA) plot demonstrating the DEGs expression distribution across all samples. The expression variability of all DEGs’ was reduced dimensionally with respect to sample type leading to distinct cluster formations. The scree plot in Supplementary Figure S1D shows the of variances accounted for by the top principal components (PCs).

ARDS-specific WGCN formation and hub module detection

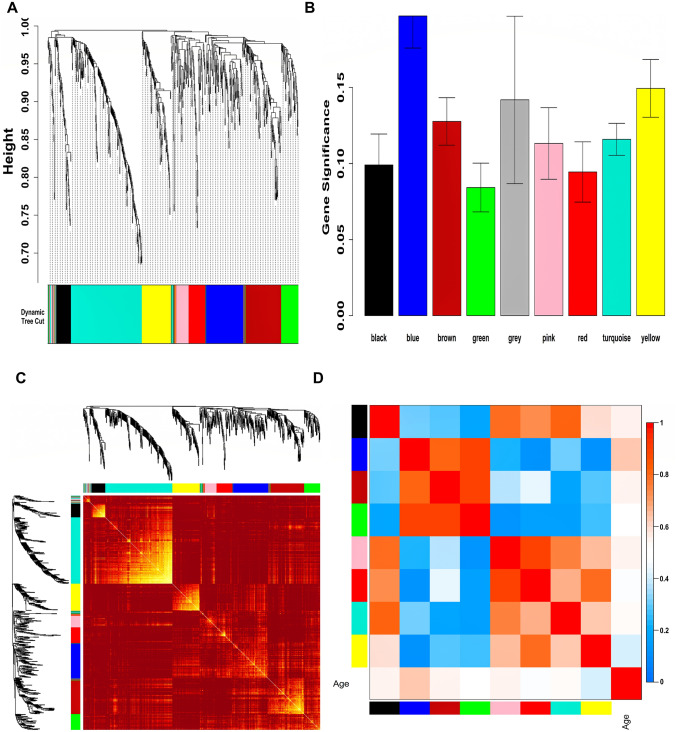

Expression data of ARDS-specific DEGs and respective age data of all samples were given as input to WGCNA. In compliance with the WGCNA guidelines, (corresponding to scale-free ) was picked for the construction of WGCN. Supplementary Figure S2 shows plots for in consideration with SFT criteria. Figure 1A shows a total of nine unique color-coded modules (i.e., grey, pink, black, red, green, yellow, brown, blue, turquoise) ranging in size from to . Figure 1B shows a GS barplot correlated with age across all modules where the blue module () was highly correlated. This relationship was highly significant ( and correlated (). Figure 1C shows the gene co-expression network (GCN) as a TOM plot among all module genes. Due to the short merging height observed in ME dendrogram, there was no need for merging modules. The grey module was rejected for further analysis since it contained unassigned genes. Figure 1D displays an eigengene adjacency heatmap for finding groups of highly correlated eigengenes termed “meta-modules”. MM versus GS correlation trend and p-values for eight modules is shown in Supplementary Table S1. GS versus k.in correlation trend and p-values for eight modules is shown in Supplementary Table S2. The blue module was chosen as our hub module based on GS versus MM and GS versus k.in correlation pattern.

Fig. 1.

A Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of ARDS-specific DEGs clustered based on dissTOM and nine color-coded modules obtained using Dynamic Tree Cut. The sizes of modules were as follows: black (), blue (), brown (), pink (), red (), green (), yellow (), turquoise (), and grey (). B Barplot showing the distribution of GS and error bars across nine modules. C Representation of WGCN as a TOM plot. Genes within columns and their corresponding rows were hierarchically clustered by cluster dendrograms (displayed along the top and left side of the plot). Progressively darker and lighter red colors within the matrix indicate higher and lower topological overlap among genes. Dark colored blocks along the diagonal signify the modules. D Eigengene adjacency heatmap shows the relatedness of co-expression gene modules. These values were based on linear regression coefficients of determination which were obtained utilizing the ME values from WGCNA. Red indicates a correlation between and while blue indicates a correlation between and

ARDS-specific 3-node miRNA-mRNA-TF network construction & topological analysis

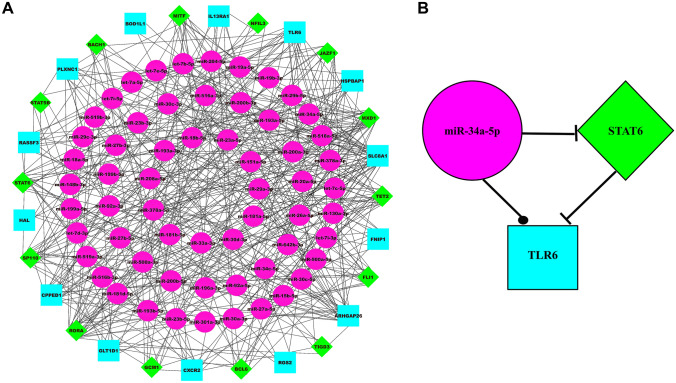

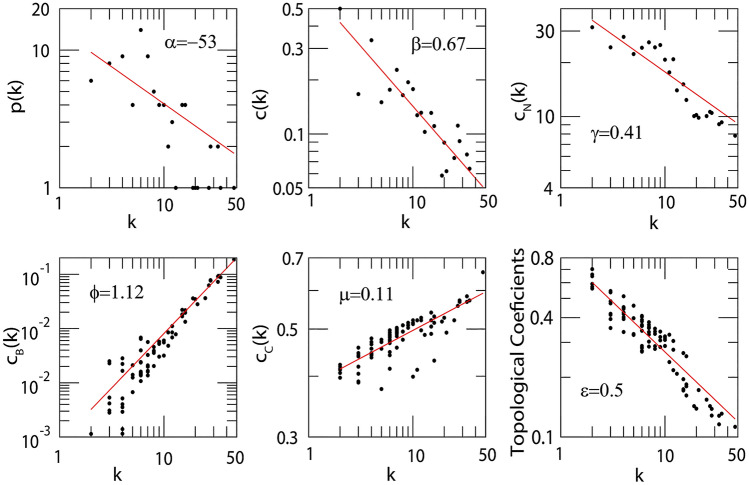

ARDS-specific 3-node miRNA-mRNA-TF network comprised nodes and edges as shown in Fig. 2A. Among these edges, belonged to miRNA-mRNA pairs, belonged to TF-mRNA pairs, and belonged to miRNA-TF pairs. Among the total nodes, , , and belonged to ARDS-specific TFs, mRNAs, and miRNAs. The degree range of miRNAs, mRNAs, and TFs in the FFL varied from to , to , and to , respectively. The degrees (average) of TFs, mRNAs and miRNAs were , , and . Based on essential centrality measures such as degree, betweenness, and closeness, the most strongly connected subnetwork motif within FFL included one TF (STAT6), one miRNA (miR-34a-5p), and one mRNA (TLR6) as shown in Fig. 2B. Thus, these regulatory elements act as hubs that might be crucial in ARDS progression. The topological properties of the FFL can be seen in Fig. 3. Because only a fewer higher-grade node numbers have significant , and values, the number of higher regulating hubs that can monitor the cancer network is smaller. Therefore, the network is dominated by moderately low-degree nodes (proteins/genes), so the network’s structure, functioning, and control are mainly performed by these low-degree proteins/genes. However, the sparsely distributed few major/leading hubs can play an important role in maintaining and regulating the stability of the cancer network. Upon study, our network demonstrated that power-law distributions were followed for the likelihood of distribution of node degree (), clustering coefficient () and neighborhood connectivity ((k)) with negative exponents (Eq. 1). This power-law function shows that the network displayed hierarchical-scale free action with the system-level organization of communities. The distribution of power laws for , , and against the distribution of degrees with negative exponents indicating more system-level organization of modules (Eq. 2). This specifies the assortive nature of the modules, indicating the likelihood of rich club forming. The hubs play a crucial role in maintaining the stability and properties of the network.

| 1 |

Fig. 2.

A ARDS-specific 3-node miRNA FFL network comprising nodes and edges. Pink-colored circular nodes represent ARDS-specific miRNAs, green-colored diamond nodes represent significant human TFs, and cyan-colored nodes represent ARDS-specific hub DEGs. B ARDS-specific highest-order subnetwork FFL motif comprising one TF (STAT6), one miRNA (miR-34a-5p), and one hub DEG (TLR6)

Fig. 3.

Topological properties of PPI network. The degree distribution (p(k)), clustering coefficient (C(k)), average neighborhood connectivity ((k)), betweenness centrality ((k)), closeness centrality ((k)) and topological coefficient ((k)) as a function of k. The power law with exponent , , , Φ, and for p(k), c(k), (k), (k), (k) and (k) respectively

The significance of hubs, and their control mechanisms, is defined by centrality estimation, such as betweenness, closeness and ) topological coefficient.

| 2 |

The power-law behaviour of these , and (centrality measurements) is again confirmed and validated by applying the power-law fitting method of Clauset et al. (Clauset et al. 2009) where p values are greater than and goodness of fit greater than . The box-and-whisker plots showing the relative expression distribution of these ARDS-specific hub genes in sepsis alone and sepsis with ARDS patient samples are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3.

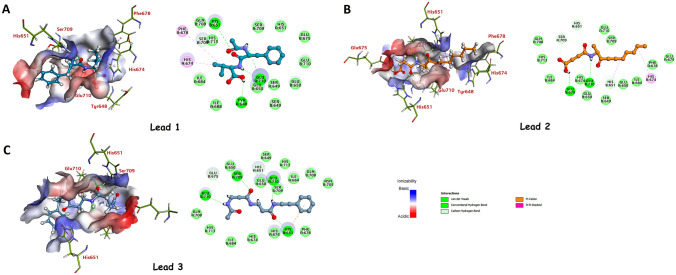

Virtual drug screening and molecular docking

4OM7 is a homodimer x-ray structure of TLR6's TIR domain. The active site was created with a sphere radius of and coordinates were , , and . Two docking algorithms in Biovia DS 2020, LibDock, and CDOCKER were utilized to assess the binding site's applicability. Initially, natural compounds were docked into the predicted active site of TLR6's TIR domain, out of which compounds were filtered utilizing this technique. The top of compounds () were then subjected to ADMET and TOPKAT filters to eliminate non-drug-like molecules and focus solely on drug-like molecules. Following that, drug-like compounds were docked utilizing the CDOCKER module of Biovia DS 2020 into the binding site of TLR6 protein to select compounds based on their ability to form favorable interactions and high CDOCKER energy with the active site. Supplementary Table S3 lists the top ten hit compounds with the highest CDOCKER energies and the amino acid residues involved in the interaction. Figure 4 depicts the receptor-ligand interactions of the selected top-3 hit compounds.

Fig. 4.

2D and 3D representation of TLR receptor residues interacting with A Lead 1, B Lead 2, and C Lead 3. Panel A, B, and C show 2D and 3D representations of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) receptor residues interacting with three different lead compounds, named Lead 1, Lead 2, and Lead 3. The 2D representations show the chemical structures of each lead compound and the specific residues in the TLR receptor that interact with the compounds. The 3D representations show the TLR receptor bound to each lead compound, indicating the orientation and spatial arrangement of the ligand and the receptor residues

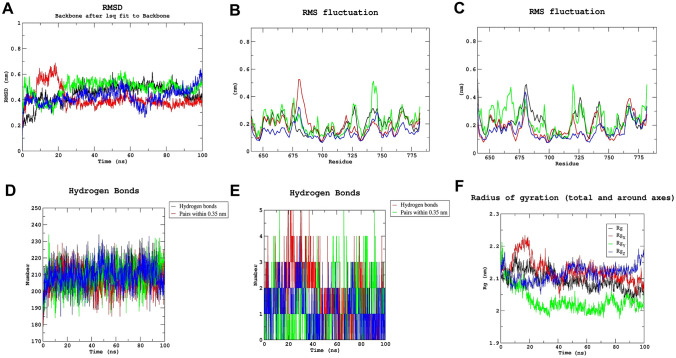

MD simulation

Utilizing MD simulation, it is possible to examine the binding stability of protein–ligand docking complexes. To verify the stability and intermolecular contacts between the protein and ligands over a time of , the complexes from docking study of three natural chemicals (Lead 1, 2 and 3) that interact with TLR protein were examined in this study. The Gromacs 2019 interface was utilized to extract MD simulation trajectories, and the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), number of hydrogen bonds, and radius of gyration () were utilized to describe the simulation findings. In MD simulation, the RMSD calculates the average distance caused by an atom's movement over a given time frame relative to a reference time frame. The RMSD value makes it possible to determine whether the simulation has equilibrated. Fluctuations between 1 and 4 A° are perfectly acceptable with respect to a reference protein structure. Backbone RMSD showed acceptable fluctuations in our three protein–ligand docking complexes, whereas Lead 1 showed least fluctuation (Fig. 5A). RMSF is required to characterize and determine the protein chain's local conformational change. Figure 5B and C show RMS fluctuations of chain A and chain B of TLR protein. Chain B showed greater fluctuation than chain A throughout the MD simulation, which showed greater flexibility in chain B.

Fig. 5.

A RMSD, B RMS fluctuation of chain A, C RMS fluctuation of Chain B, D intermolecular hydrogen bonds between proteins, E hydrogen bond between leads and TLR receptor and F radius of gyration of apoprotein, TLR (black), lead 1 (red), lead 2 (green) and lead 3 (blue) during 100 ns md simulation

Furthermore, the number of H-bonds that played an important role in the stability of the protein–ligand complex was determined utilizing simulation trajectories. Figure 5D shows that all the complexes were stable, whereas Fig. 5E shows several H-bonds persist throughout the simulation between protein and top lead compounds. Lead 1 and lead 2 had maximum number of hydrogen bonds (five), whereas lead 3 had a maximum hydrogen bonds during MD simulation. The was utilized to calculate the compactness of a protein structure. Figure 5F shows that lead had the lowest value of .

Binding free energy

The average binding free energy and its corresponding components obtained from the MM/PBSA calculation of all drug-target complexes are listed in Table 1. The table's energetic profile of all the lead molecules shows that all complexes are highly stable, although the TLR-Lead1 offers the highest stability. In the TLR-Lead1 complex, specific interaction in the form of hydrogen-bond or salt-bridge is almost three times higher than the non-specific interaction—Van der Waals interaction indicates a highly stable interaction between drug-target complex, and it maintains throughout the simulation. In the TLR-Lead2 complex, the same trend has been observed in TLR-Lead1. In the TLR-Lead3 complex, the Van der Waals interaction has dominated electrostatic interaction.

Table 1.

MM/PBSA binding free energy profile

| S. no. | Compound | ∆EVDW (kcal/mol) | ∆EELE (kcal/mol) | ∆GSOL-PB (kcal/mol) | ∆GSOL-NP (kcal/mol) | ∆Gbind-PBSA (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TLR-Lead 1 | |||||

| 2 | TLR-Lead 2 | |||||

| 3 | TLR-Lead 3 |

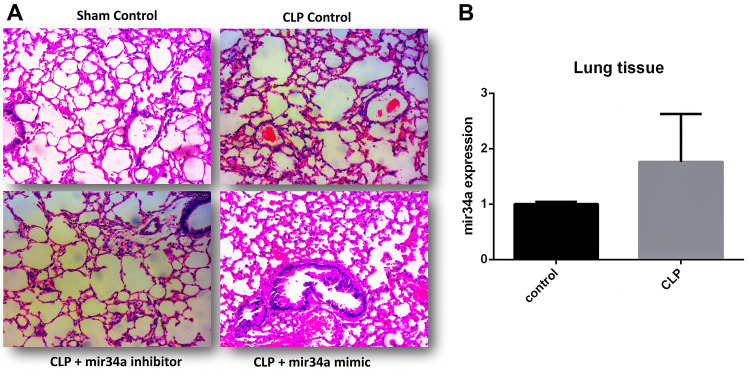

Expression of miR-34a is hiked in sepsis-induced ALI deteriorating lung function

miR-34a is found culpable in promoting inflammation by regulating the expression of different genes. The involvement of miR-34a in the progression and worsening of lung injury has been proved by different research accounts [49, 69–71]. In-silico analyses of clinical data sets of sepsis-induced ARDS suggest a hike in miR-34a expression. We also tested the CLP-induced septic mice lungs to check the expression of miR-34a compared to normal control. Figure 6B shows a considerable hike in the septic mice lung, indicating a probable correlation between miR-34a and lung injury symptoms. For this purpose, we established a sepsis-induced lung injury model. Inhibitors and mimics were injected intraperitoneally to check miR-34a involvement in sepsis-induced pathophysiology. Scramble is utilized as a control for comparison. H & E staining exhibits the changes in the lung tissue from different groups (Fig. 6A). The CLP group combined with scramble & mimic showed a thickening around the alveoli, representing hyaline membrane formation. Also, neutrophilia in interstitial and alveolar space are profusely contributing to lung injury. These observations were limited in CLP scramble group. However, it got more prominent with the addition of miR-34 mimic. Contrary to this, much less damage to the lung tissue is seen in the CLP miR-34a inhibitor group (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Sepsis-induced expression of miR-34a. A H&E staining of lung tissue from the CLP-induced septic mice. Inhibitor & mimic of miR-34a and scramble is used to create different groups to check their effect on the lung pathology by light microscope. B CLP-induced sepsis gives rise to miR-34a expression in the lung tissue. Student t-test is applied to test the significance. ( animals)

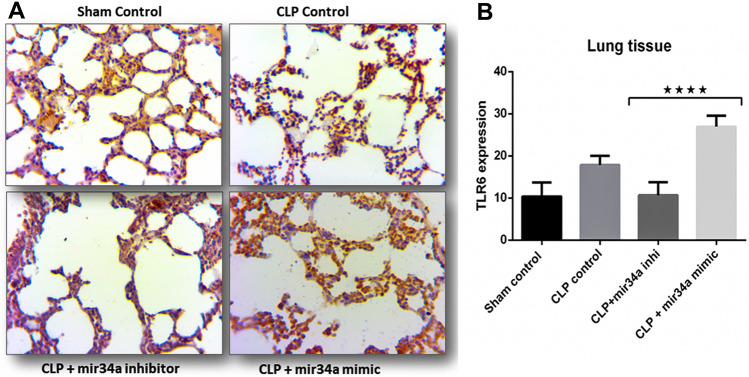

miR-34a elevates TLR6 expression in septic lung tissue

Major finding of in-silico analyses is the probability of positive interaction between TLR6 and miR-34. TLR6 work in conjugation with TLR2 forming a heterodimer for ligand recognition, which are supposed to be the derivatives of host tissue along with infectious PAMPs. Extrapulmonary sepsis puts the pro-inflammatory cytokines into circulation and the non-infectious DAMP ligands. Thus, non-infectious endogenous ligands are also part of sepsis-induced lung injury’s overall inflammatory response. Based on the in-silico findings, we put forward the idea that TLR6 expression increases in septic mice which miR-34a regulates, and it actively participates in reaching the overly inflamed lung condition. TLR6 expression was probed in different groups belonging to scramble, miR-34a mimics, and inhibitors. According to the in-silico findings, TLR6 is markedly expressed in the CLP-induced septic lungs (Fig. 7A). However, adding miR-34a mimics to the group enhanced TLR6 staining unequivocally (Fig. 7A). Contrary to this observation, less and dampened expression is seen in CLP + miR-34a inhibitors, strengthening our idea of a probable relationship between miR-34a and TLR6 (Fig. 7A). Positively stained areas were quantified by imageJ software and graphically represented by Prism software (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

miR-34a regulates the expression of TLR6. A IHC stained septic mice lung tissue sections to see the expression of TLR6 antigen. Different groups were created to see variability in expression. B Two-way ANOVA quantified TLR6 expression. , ( animals)

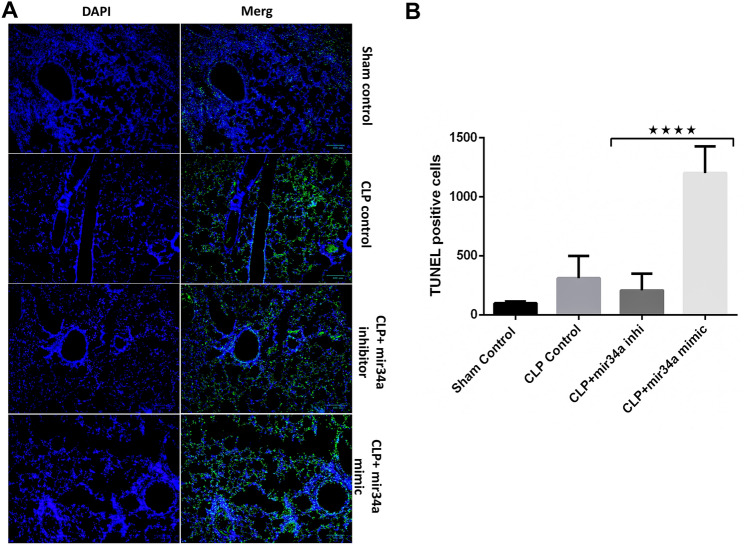

miR-34a accelerates the sepsis-induced apoptosis, which exacerbates lung injury

Apoptosis is a dynamic phenomenon significantly contributing to the pathophysiology of sepsis. In the acute phase, it has successfully fostered disease severity. In response to the changed inflammatory settings cells undergo apoptosis by altering the integrity of DNA. To check whether miR-34a augments sepsis-induced apoptosis, we checked the septic mice lung tissue by TUNEL assay, which detects the fragmented DNA. The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzyme utilizes the fragmented DNA of cells as a template. TUNEL-positive cells are observed as green, fluorescent dots in lung sections. Based on staining, we compared the different treatment groups. More TUNEL-positive cells were visible in the CLP group as compared to the sham control figure (Fig. 8A). Further, the number of positive cells showed a remarkable hike by adding miR-34a mimic. TUNEL-positive cells were quantified by ImageJ software and graphically represented to test the significance (Fig. 8B). The results help us derive that miR-34a profoundly augments the apoptosis induced by CLP-induced sepsis in mice lungs. (Figs. 8A, B).

Fig. 8.

miR-34a promotes apoptosis in CLP-induced septic lungs. A TUNEL staining of the paraffin-embedded septic mice lungs from different treatment groups. B Quantification of the positively stained cells by ImageJ software by two-way ANOVA. , ( animals)

Discussion

The major finding of the present study is that miR-34a significantly augments the expression of TLR6 in sepsis-induced lung injury. Simultaneously miR-34a checks the STAT6 signaling to promote inflammation in sepsis. Also, we report that epithelial cell apoptosis is accelerated by miR-34a, the leading cause of worsening lung injury symptoms, ultimately leading to mortality. FFLs can engineer recurrent network motifs to enhance gene regulation's robustness in mammalian genomes (Bo et al. 2021). A three-node FFL can be extended to form a four-node or five-node FFL by adding further interaction links. 3-node miRNA FFL comprises a TF, a miRNA, and a common gene target with miRNAs dominating or driving the whole network (Sun et al. 2012). Finally, in-silico efforts reveal the potential of natural compounds (Lead1, Lead2, and Lead3) as anti-sepsis candidate molecules against TLR6's TIR domain.

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory setting that arises due to dysregulated immune response to microbial infection (Gyawali et al. 2019; Rello et al. 2017). Lungs are supposed to be most vulnerable and responsive to the changed inflammatory milieu (Hotchkiss et al. 2016, 1999). This rapidly induces alterations in lung functioning, which further aggravates disease symptoms. Thus, sepsis-induced lung injury is a major concern contributing to the global disease tally. Infectious PAMP ligands are the leading cause of initiation of any microbial infection; however, the continuous trigger for dysregulated immune response includes non-infectious endogenous DAMP ligands (Kawasaki and Kawai 2014; Takeda and Akira 2004). Extrapulmonary infection like sepsis generates a systemic inflammatory response flagged by the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators and their secretion into circulation, along with the DAMPs (Humphries et al. 2018). This results to the expression and activation of TLR receptors in the lungs appreciably (Radstake et al. 2004; Ramírez Cruz et al. 2004). TLR4-MyD88 dependent signaling leads to the activation of TF NFκB, which finally culminates in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL6, and TNFα (Kawasaki and Kawai 2014; Radstake et al. 2004). This further expresses different TLRs on the membranes of APCs and endothelial cells. The TLR signaling releases cytokines, which act as an attractant for the neutrophils to the site of infection and the injured tissue (Kremserova et al. 2016). Thus, neutrophils are inevitable in reducing microbial infection, but it also helps improve the symptoms of lung injury (Ginzberg et al. 2001; Grommes and Soehnlein 2011). However, scenario changes in the condition of systemic inflammation as in sepsis. PAMPs and DAMPs actively contribute to the continuous provocation of the immune response (Denning et al. 2019; Gentile and Moldawer 2013). This leads to lung neutrophilia, which becomes detrimental to host tissue. In this study, we propose that non-infectious endogenous ligands actively trigger the TLR6 signaling in sepsis and may significantly contribute to inflammation.

Our study reports the expression of TLR6 in CLP-induced septic mice lungs. TLR6 signaling culminates in the expression of pro-inflammatory genes. Lungs harvested from septic mice were subjected to IHC analyses to look for the expression of TLR6. Profuse TLR6 staining was observed in the CLP-only group. As per our hypothesis, we found miR-34a augmenting the expression of TLR6 in the lung sections from the CLP + miR-34a mimic group. TLR6 staining was quantified by imageJ software. The data obtained were significant enough to correlate miR-34a and TLR6 expression. Further, we claim that miR-34a aggravates lung inflammation in septic mice via TLR6 signaling and the canonical pathways. miRNAs are differentially expressed in reported cases of sepsis, underscoring their role in the progression or resolution of sepsis (Ghafouri-Fard et al. 2021). miR-34a is well acknowledged for hiking inflammation by polarizing macrophages to the M1 phenotype (Cheng et al. 2018; Khan et al. 2020) simultaneously down-regulating the anti-inflammatory mediators (Shetty et al. 2017). The expression of miR-34a is notable in the LPS-induced lung injury model. However, inhibition of miR-34a successfully mitigates lung injury characteristics overall, positively affecting survival (Chen et al. 2020). We also checked the expression of miR-34a in CLP-induced sepsis mice. Results indicate a marked increase in expression compared to the control group. Based on the results we can say that miR-34a plays a vital role in the sepsis pathophysiology.

Epithelial cell apoptosis is one of the contributors to ALI (Martin et al. 2005). miR-34a mediates p53 acetylation to accelerate epithelial cell apoptosis, thus actively promoting lung injury (Shetty et al. 2017). However, the inhibition of miR-34a in LPS-treated HUVEC cells slowed down apoptosis (Zhang et al. 2020). Apoptosis is commonly observed in sepsis where epithelial cell apoptosis is reported to contribute to the severity of lung injury in its acute phase. Contrary to this in the latter phase, immune cell apoptosis paramount’s to immune suppression (Guinee et al. 1996; Hattori et al. 2010; Hotchkiss et al. 2003; Kitamura et al. 2001; Lang and Matute-Bello 2009; Luan et al. 2015). Intra-tracheally instilled LPS induces apoptosis in epithelial and endothelial cells (Kawasaki et al. 2000; Ogata-Suetsugu et al. 2017). One of the attributes of apoptosis is DNA damage/ fragmentation (Maeyama et al. 2001; Perl et al. 2007). This fragmented DNA is a template for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzyme in TUNEL assay. In the present study, septic mice lung sections from the CLP group were subjected to a TUNEL assay to affirm sepsis-induced apoptosis. The findings were in coherence with the previously reported work. CLP group showed positive TUNEL staining convincing enough to pronounce that sepsis-induced inflammation is the underlying cause of epithelial cell death. Inclusion of miR-34a mimics had a compounding effect on apoptosis-induced cell death. Our study not only reiterates the effect of sepsis on lung epithelial cells but also ascertains the role of miR-34a in exacerbating inflammation. The strategy adopted by miR-34a in elevating inflammation is checking the expression of anti-inflammatory genes. Different research groups have reported miR-34a targeting the genes that foster the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype of macrophages (Khan et al. 2020; Tundup et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2020). STAT6 is fairly acclaimed for its involvement in modulating the phenotype of macrophages to the M2 state (Cai et al. 2019; Gong et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2018; Li et al. 2021). The expression of STAT6 accelerates the uptake of apoptotic neutrophils which is the key to the resolution of inflammation (Nepal et al. 2019). In a separate study, STAT6 has been validated as a target of miR-34a (Tundup et al. 2014). To analyze the contribution of the miR-34a-STAT6 axis in the deterioration of symptoms in septic mice, we checked the expression of STAT6 with conditions of inhibition and overexpression of miR-34a. Inhibition of miR-34a increased staining of STAT6 in the septic lung sections. Contrary to this observation, adding miR-34a mimic to the CLP group swiftly checks the expression of STAT6. Based on the translational study of STAT6 with caveat of miR-34a, we can afford to say that miR-34a actively targets STAT6 as one of the strategies to accelerate inflammation in sepsis-induced ALI/ARDS.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Prithvi Singh would like to thank the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for awarding him Senior Research Fellowship [Grant Number: BMI/11(89)/2020]. Indrakant Kumar Singh would like to thank ICMR [Grant Number: ISRM/12(58)/2020] and Department of Health Research (DHR), Government of India (Grant Number: LTFTII-ID-2021-2013) for providing him financial assistance. Prakash Jha would like to thank the Department of Science & Technology (DST), Government of India for awarding him DST-INSPIRE fellowship (Grant Number: DST/INSPIRE/03/2016/000026). Madhu Chopra would like to thank the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India (grant number: BT/PR40153/BTIS/137/8/2021) for providing Bioinformatics Infrastructure Facility (BIF) at Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Center for Biomedical Research (ACBR).

Abbreviations

- ALI

Acute lung injury

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- miRNA

microRNA

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- WGCNA

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

- FFL

Feed-forward loop

- TFs

Transcription factors

- MD

Molecular dynamics

- CLP

Cecal ligation puncture

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- HGNC

HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee

- ME

Module Eigengene

- MM

Module membership

- GS

Gene significance

- MM/PBSA

Molecular mechanics/Poisson‐Boltzmann surface area

- RMSD

Root mean square deviation

- RMSF

Root mean square fluctuation

Radius of gyration

- TLR6

Toll-like receptor 6

- STAT6

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6

Author contributions

MJK: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, investigation, validation, visualization. PS: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. PJ: software, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. AN: software, writing—review & editing. MZM: software, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. GB: writing—review & editing. BK: writing—review & editing. KP: software, data curation, writing—review & editing. SA: resources, writing—review & editing. MC: writing—review & editing. RD: writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration. IKS: writing—review & editing, resources, supervision, project administration. MAS: writing—review & editing, resources, supervision, project administration.

Funding

This research work did not receive any external funding.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article is available in NCBI-GEO at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE66890, and can be accessed with GSE66890.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have are no conflict of interest.

Human ethics and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Mohd Junaid Khan and Prithvi Singh have contributed equally to this work as co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Ravins Dohare, Email: ravinsdohare@gmail.com.

Indrakant Kumar Singh, Email: iksingh@db.du.ac.in.

Mansoor Ali Syed, Email: smansoor@jmi.ac.in.

References

- Abdelaleem OO, Mohammed SR, El Sayed HS, Hussein SK, Ali DY, Abdelwahed MY, Gaber SN, Hemeda NF, El-Hmid RGA. Serum miR-34a-5p and miR-199a-3p as new biomarkers of neonatal sepsis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0262339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas-Padilla M, Mata-Haro V. Regulation of TLR signaling pathways by microRNAs: implications in inflammatory diseases. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2018;43:482–489. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2018.81351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X-Y, Ma Y, Ding R, Fu B, Shi S, Chen X-M. miR-335 and miR-34a promote renal senescence by suppressing mitochondrial antioxidative enzymes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1252–1261. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, Ranieri M, Rubenfeld G, Thompson BT, Wrigge H, Slutsky AS, Pesenti A, for the LUNG SAFE Investigators and the ESICM Trials Group Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315:788. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersten AD, Edibam C, Hunt T, Moran J. Incidence and mortality of acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome in three Australian states. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:443–448. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.2101124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billack B. Macrophage activation: role of toll-like receptors, nitric oxide, and nuclear factor kappa B. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70:102. doi: 10.5688/aj7005102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo C, Zhang H, Cao Y, Lu X, Zhang C, Li S, Kong X, Zhang X, Bai M, Tian K, Saitgareeva A, Lyaysan G, Wang J, Ning S, Wang L. Construction of a TF–miRNA–gene feed-forward loop network predicts biomarkers and potential drugs for myasthenia gravis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2416. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81962-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W, Dai X, Chen J, Zhao J, Xu M, Zhang L, Yang B, Zhang W, Rocha M, Nakao T, Kofler J, Shi Y, Stetler RA, Hu X, Chen J. STAT6/Arg1 promotes microglia/macrophage efferocytosis and inflammation resolution in stroke mice. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e131355. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Lyu YI, Tang J, Li Y. MicroRNAs: novel regulatory molecules in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Biomed Rep. 2016;4:523–527. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal-Fernández P, Lorente JA, Ballén-Barragán A, Matute-Bello G. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and diffuse alveolar damage. New insights on a complex relationship. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:844–850. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201609-728PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chafik A. Mir-34a-5p and mir-34a-3p contribute to the signaling pathway of p53 by targeting overlapping sets of genes. IJMBOA. 2018 doi: 10.15406/ijmboa.2018.03.00042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T-C, Wentzel EA, Kent OA, Ramachandran K, Mullendore M, Lee KH, Feldmann G, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Lowenstein CJ, Arking DE, Beer MA, Maitra A, Mendell JT. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Ding R, Hu Z, Yin X, Xiao F, Zhang W, Yan S, Lv C. MicroRNA-34a inhibition alleviates lung injury in cecal ligation and puncture induced septic mice. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1829. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D-L, Fang H-X, Liang Y, Zhao Y, Shi C. MicroRNA-34a promotes iNOS secretion from pulmonary macrophages in septic suckling rats through activating STAT3 pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;105:1276–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauset A, Shalizi CR, Newman MEJ. Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM Rev. 2009;51:661–703. doi: 10.1137/070710111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clough E, Barrett T. The gene expression omnibus database. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1418:93–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Ge J, Xie N, Banerjee S, Zhou Y, Liu R-M, Thannickal VJ, Liu G. miR-34a promotes fibrosis in aged lungs by inducing alveolarepithelial dysfunctions. Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;312:L415–L424. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00335.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtale G, Rubino M, Locati M. MicroRNAs as molecular switches in macrophage activation. Front Immunol. 2019;10:799. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning N-L, Aziz M, Gurien SD, Wang P. DAMPs and NETs in sepsis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2536. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson JL, Gillet AS, Zu Y, Brown M, Pham T, Yoshida Y, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Douglas IS, Moore M, Tea K, Wetherbie A, Stevens R, Lefante J, Shaffer JG, Armaignac DL, Belden KA, Kaufman M, Heavner SF, Danesh VC, Cheruku SR, St-Hill CA, Boman K, Deo N, Bansal V, Kumar VK, Walkey AJ, Kashyap R, Mesland J-B, Henin P, Petre H, Buelens I, Gerard A-C, Clevenbergh P, Del-Granado RC, Mercado JA, Vega-Terraza E, Iturricha-Caceres MF, Garza R, Chu E, Chan V, Gavidia OY, Pachon F, Kassas ME, Tawheed A, Pineda E, Reyes Guillen GM, Soto HA, Vallecillo-Lizardo AK, Segu SS, Chakraborty T, Joyce E, Kasumalla PS, Vadgaonkar G, Ediga R, Basety S, Dammareddy S, Raju U, Manduva J, Kolakani N, Sripathi S, Chaitanya S, Cherian A, Parameswaran S, Parthiban M, Menu PA, Daga MK, Agarwal M, Rohtagi I, Papani S, Kamuram M, Agrawal KK, Baghel V, Patel Kirti K, Mohan SK, Jyothisree E, Dalili N, Nafa M, Matsuda W, Suzuki R, Sanui M, Horikita S, Itagaki Y, Kodate A, Takahashi Y, Moriki K, Shiga T, Iwasaki Y, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Gonzale JG, Salcido-Montenegro A, Camacho-Ortiz A, Hassan-Hanga F, Galadanci H, Gezawa AS, Kabir H, Amole TG, Haliru DG, Ibrahim AS, Asghar MS, Syed M, Naqvi SAA, Zabolotskikh IB, Musaeva TS, Alamoudi RK, AlSharif HM, Almazwaghi SA, Elsakran MS, Aid MA, Darwich MA, Hagag OM, Ali SA, Rocacorba A, Supena K, Juane ER, Medina J, Baduria J, Amer MR, Bawazeer MA, Dahhan TI, Kseibi E, Butt AS, Khurshid SM, Rabee M, Abujazar M, Alghunaim RK, Abualkhair M, AlFirm AT, Almazyad MA, Alarifi MI, Macarambon JM, Bukhari AA, Albahrani HA, Asfina KN, Aldossary KM, Zoran MZ, Popadic V, Klasnja S, Bojicic J, Kovacevic B, Predrag S, Stojakov DS, Ignjatovic DK, Bojicic SC, Bobos MM, Nenadic IB, Zaric MS, Djuric MD, Djukic VR, Teruel SY, Martin BC, Sili U, Bilgin H, Ay P, Dodd KW, Goodmanson N, Hesse K, Bird P, Weinert C, Schoenrade N, Altaher A, Mayar E, Aronson M, Cooper T, Logan M, Miner B, Papo G, Siegal EM, Runningen P, Patel LA, Melamed RR, Tierney DM, Raj VS, Mazumder N, Hill CS, Kirkland L, Schmitz N, Sigman A, Hall J, Raval AA, Franks A, Jarvis JM, Kharbanda A, Jhajhria S, Fyffe Z, Capizzi S, Alicie B, Green M, Corckarell L, Drennan A, Dubuque K, Fambrough T, Gasaway N, Krantz B, Nebi P, Orga J, Serfass M, Simion A, Warren K, Wheeler C, Woolman C, Christie AB, Ashley DW, Adiga R, Moyer AS, Verghese GM, Sikora-Newsome A, Forehand CC, Bruning R, Jones TW, Sabov M, Zaidi F, Tissavirasingham F, Malipeddi D, Mosier JM, Lutrick K, Campbell BS, Wilson C, Rivers P, Brinks J, Ndiva-Mongoh M, Gilson B, Armaignac Donaa L, Parris D, Zuniga MP, Vargas I, Boronat V, Hutton A, Kaur N, Neupane P, Sadule-Rios N, Rojas LM, Neupane A, Rivera P, Valle Carlos C, Vincent G, Amin M, Schelle ME, Steadham A, Howard CM, McBride C, Abraham J, Garner O, Richards K, Collins K, Antony P, Mathew S, Danesh V, Dubrocq G, Davis AL, Hammers MJ, McGahey IM, Farris AC, Priest E, Korsmo R, Fares L, Skiles K, Shor SM, Burns K, Flores M, Newman L, Wilk DA, Ettlinger J, Bomar J, Darji H, Arroliga A, Dowell CA, Gonzales GH, Flores MF, Walkey A J, Waikar SS, Garcia MA, Colona M, Kibbelaar Z, Leong M, Wallman D, Soni K, Maccarone J, Gilman J, Devis Y, Chung J, Paracha M, Lumelsky DN, DiLorenzo M, Abdurrahman N, Johnson S, Hersh MAM, Wachs SL, Swigger BS, Sattler LA, Moulton MN, Zammit K, McGrath PJ, Loeffler W, Chilbert MR, Tirupathi R, Tang A, Safi A, Green C, Newell J, Ramani N, Ganti BH, Ihle RE, Davis EA, Martin SA, Sayed IA, Gist KM, Strom L, Chiotos K, Blatz AM, Lee G, Burnett RH, Traynor DM, Surani S, White J, Khan A, Dhahwal R, Cheruku S, Ahmed F, Deonarine C, Jones A, Shaikh MA, Preston D, Chin J, Vachharajani V, Duggal A, Rajendram P, Mehkri O, Dugar S, Biehl M, Sacha G, Houltham S, Kind A, Ashok K, Poynter B, Beukemann ME, Rice R, Gole S, Shaner V, Conjeevaram A, Ferrari M, Alappan N, Minear S, Hernandez-Montfort J, Nasim SS, Sunderkrishnan R, Sahoo D, Milligan PS, Gupta SK, Koglin JM, Gibson R, Johnson L, Preston F, Scott C, Nungester B, Byrne DD, Schorr CA, Grant K, Doktar KL, Porto MC, Kaplan O, Siegler JE, Schonewald B, Woodford A, Tsai A, Reid S, Bhowmick K, Daneshpooy S, Mowdawalla C, Dave TA, Connor Crudeli WK, Ferry C, Nguyen L, Modi S, Padala N, Patel PJ, Lin Belle Qiuyun J, Liu FM, Kota R, Banerjee A, Daugherty SK, Atkinson S, Shrimpton K, Ontai S, Contreras B, Obinwanko U, Amamasi N, Sharafi A, Lee S, Esber Z, Jinjvadia C, Bartz RR, Krishnamoorthy V, Kraft B, Pulsipher A, Friedman E, Mehta S, Kaufman M, Lobel G, Gandhi N, Abdelaty A, Shaji E, Lim K, Marte J, Sosa DA, Yamane DP, Benjenk I, Prasanna N, Perkins N, Roth PJ, Litwin A, Pariyadath A, Moschella P, Llano T, Waller C, Kallies K, Thorsen J, Fitzsimmons A, Olsen H, Smalls N, Davis SQ, Jovic V, Masuda M, Hayes A, Nault K, Smith M, Snow W, Liptak R, Durant H, Pendleton V, Nanavati A, Mrozowsk R, Doubleday E, Liu YM, Zavala S, Shim E, Reilkoff RA, Heneghan JA, Eichen S, Goertzen L, Rajala S, Feussom G, Tang B, Junia CC, Lichtenberg R, Sidhu H, Espinoza D, Rodrigues S, Zabala MJ, Goyes D, Susheela A, Hatharaliyadda B, Rameshkumar N, Kasireddy A, Maldonado G, Beltran L, Chaugule A, Khan H, Patil N, Patil R, Cartin-Ceba R, Sen A, Talaei F, Kashyap R, Pablo Domecq J, Gajic O, Bansal V, Tekin A, Lal A, O’Horo JC, Deo NN, Sharma M, Qamar S, Singh R, Valencia Morales DJ, La Nou AT, Bogojevic M, Zec S, Sanghavi D, Guru P, Morno Franco P, Ganaphadithan K, Saunders H, Fleissner Z, Garcia J, Yu-Lee-Mateus A, Yarrarapu SN, Kaur N, Giri A, Mustafa-Hasan M, Donepudi A, Khan SA, Jain NK, Koritala T, Nanchal RS, Bergl PA, Peterson JL, Yamanaka T, Barreras NA, Markos M, Fareeduddin A, Mehta R, Venkata C, Engemann M, Mantese A, Tarabichi Y, Perzynski A, Wang C, Kotekal D, Briceno-Bierwirth AC, Orellana GM, Catalasan G, Ahmed S, Matute CF, Hamdan A, Salinas I, Nogal GD, Tejada A, Chen J-T, Hope A, Tsagaris Z, Ruen E, Hambardzumyan A, Siddiqi NA, Jurado L, Tincher L, Brown C, Aulakh BS, Tripathi S, Bandy JA, Kreps L, Bollinger DR, Scott Stienecker R, Melendez AG, Brunner TA, Budzon SM, Heffernan JL, Souder JM, Miller TL, Maisonneuve AG, Redfern RE, Shoemaker J, Micham J, Kenney L, Naimy G, J Pulver KP, Yehle J, Weeks A, Inman T, Delmonaco BL, Franklin A, Heath M, Vilella AL, Kutner SB, Clark K, Moore D, Anderson HL, Rajkumar D, Abunayla A, Heiter J, Zaren HA, Smith SJ, Lewis GC, Seames L, Farlow C, Miller J, Broadstreet G, Martinez A, Allison M, Mittal A, Ruiz R, Skaanland A, Ross R, Patel U, Hodge J, Patel Krunal Kumar Dalal S, Kavani H, Joseph S, Bernstein MA, Goff IK, Naftilan M, Mathew A, Williams D, Murdock S, Ducey M, Nelson K, Block J, Mitchel J, O’Brien CG, Cox S, Amzuta I, Shah A, Modi R, Al-Khalisy H, Masuta P, Schafer M, Wratney A, Carter KL, Olmos M, Parker BM, Quintanilla J, Craig TA, Clough BJ, Jameson JT, Gupta N, Jones TL, Ayers SC, Harrell AB, Brown BR, Darby C, Page K, Brown A, McAbee J, Belden KA, Baram M, Weber DM, DePaola R, Xia Y, Carter H, Tolley A, Ferranti M, Steele M, Kemble L, Sethi J, Cheng Han C, Pagliaro J, Husian A, Malhotra A, Zawaydeh Q, Sines BJ, Bice TJ, Markotic D, Bosnjak I, Vail EA, Nicholson S, Jonas RB, Dement AE, Tang W, DeRose M, Villarreal RE, Dy RV, Lardino A, Sharma J, Czieki R, Christopher J, Lacey R, Mashina M, Patel K, Gomaa D, Goodman M, Wakefield D, Spuzzillo A, Shinn JO, Bihorac A, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Omalay G, Hashemighouchani H, Cupka JS, Ruppert MM, McGonagill PW, Galet C, Hubbard J, Wang D, Allan L, Badheka A, Chegondi M, Nazir U, Rampon G, Riggle J, Dismag N, Akca O, Lenhardt R, Cavallazzi RS, Jerde A, Black A, Polidori A, Griffey H, Winkler J, Brenzel T, Alvarez RA, Alarocon-Calderon A, Sosa MA, Mahabir SK, Patel MJ, Parker P, Admon A, Hanna S, Chanderraj R, Pliakas M, Wolski A, Cirino J, Dandachi D, Regunath H, Camazine MN, Geiger GE, Njai AO, Saad BM, Shah FA, Chuan B, Rawal SL, Piracha M, Tonna JE, Levin NM, Suslavich K, Tsolinas R, Fica ZT, Skidmore CR, Stapleton RD, Dixon AE, Johnson O, Ardren SS, Burns S, Raymond A, Gonyaw E, Hodgdon K, Houseger C, Lin B, McQuesten K, Pecott- Grimm H, Sweet J, Ventrone S, Khandelwal N, West TE, Caldwell ES, Lovelace-Macon L, Garimella N, Dow DB, Akhter M, Rahman RA, Mulrow M, Wilfong EM, Vela K, Khanna AK, Harris L, Cusson B, Fowler J, Vaneenenaam D, Mckinney G, Udoh I, Johnson K, Lyons PG, Michelson AP, Haulf SS, Lynch LM, Nguyen NM, Steinbery A, Braus N, Pattan V, Papke J, Jimada I, Mhid N, Chakola S, Sheth K, Ammar A, Ammar M, Lopez VT, Dela-Cruz C, Khosla A, Gautam S (2021) Metabolic syndrome and acute respiratory distress syndrome in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open 4: e2140568. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40568

- Du R, Sun W, Xia L, Zhao A, Yu Y, Zhao L, Wang H, Huang C, Sun S. Hypoxia-induced down-regulation of microRNA-34a promotes EMT by targeting the notch signaling pathway in tubular epithelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckmann L. CHAPTER 42—innate immunity. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. 4. Burlington: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 1033–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Englert JA, Bobba C, Baron RM. Integrating molecular pathogenesis and clinical translation in sepsis-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. JCI Insight. 2019;4:124061. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.124061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferruelo A, Peñuelas Ó, Lorente JA. MicroRNAs as biomarkers of acute lung injury. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:34–34. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.01.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foroushani A, Agrahari R, Docking R, Chang L, Duns G, Hudoba M, Karsan A, Zare H. Large-scale gene network analysis reveals the significance of extracellular matrix pathway and homeobox genes in acute myeloid leukemia: an introduction to the Pigengene package and its applications. BMC Med Genomics. 2017;10:16. doi: 10.1186/s12920-017-0253-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile LF, Moldawer LL. DAMPs, PAMPs, and the origins of SIRS in bacterial sepsis. Shock. 2013;39:113–114. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318277109c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafouri-Fard S, Khoshbakht T, Hussen BM, Taheri M, Arefian N. Regulatory role of non-coding RNAs on immune responses during sepsis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:798713. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.798713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzberg HH, Cherapanov V, Dong Q, Cantin A, McCulloch CAG, Shannon PT, Downey GP. Neutrophil-mediated epithelial injury during transmigration: role of elastase. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G705–G717. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M, Zhuo X, Ma A. STAT6 upregulation promotes M2 macrophage polarization to suppress atherosclerosis. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2017;23:240–249. doi: 10.12659/msmbr.904014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin AJ, Guo C, Cook JA, Wolf B, Halushka PV, Fan H. Plasma levels of microRNA are altered with the development of shock in human sepsis: an observational study. Crit Care. 2015;19:440. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassin-Delyle S, Abrial C, Salvator H, Brollo M, Naline E, Devillier P. The role of toll-like receptors in the production of cytokines by human lung macrophages. J Innate Immun. 2020;12:63–73. doi: 10.1159/000494463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grommes J, Soehnlein O. Contribution of neutrophils to acute lung injury. Mol Med. 2011;17:293–307. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinee D, Fleming M, Hayashi T, Woodward M, Zhang J, Walls J, Koss M, Ferrans V, Travis W. Association of p53 and WAF1 expression with apoptosis in diffuse alveolar damage. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:531–538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyawali B, Ramakrishna K, Dhamoon AS. Sepsis: the evolution in definition, pathophysiology, and management. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119835043. doi: 10.1177/2050312119835043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:509–524. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y, Takano K, Teramae H, Yamamoto S, Yokoo H, Matsuda N. Insights into sepsis therapeutic design based on the apoptotic death pathway. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;114:354–365. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10R04CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, Tinsley KW, Cobb JP, Matuschak GM, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230–1251. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Karl IE. Role of apoptotic cell death in sepsis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:585–592. doi: 10.1080/00365540310015692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL, Opal SM, Reinhart K, Turnbull IR, Vincent J-L. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16045. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Wang H, Han C, Cao X. Src promotes anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophage generation via the IL-4/STAT6 pathway. Cytokine. 2018;111:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Hao C, Tang S. 2020. From sepsis to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): emerging preventive strategies based on molecular and genetic researches. Biosci Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Humphries DC, O’Neill S, Scholefield E, Dorward DA, Mackinnon AC, Rossi AG, Haslett C, Andrews PJD, Rhodes J, Dhaliwal K. Cerebral concussion primes the lungs for subsequent neutrophil-mediated injury. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e937–e944. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:99–110. doi: 10.1038/nrg2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang T-H, Park HH. Crystal structure of TIR domain of TLR6 reveals novel dimeric interface of TIR-TIR interaction for toll-like receptor signaling pathway. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:3305–3313. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha P, Saluja D, Chopra M. Structure-guided pharmacophore based virtual screening, docking, and molecular dynamics to discover repurposed drugs as novel inhibitors against endoribonuclease Nsp15 of SARS-CoV-2. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2022.2079561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha P, Singh P, Arora S, Sultan A, Nayek A, Ponnusamy K, Syed MA, Dohare R, Chopra M. Integrative multiomics and in silico analysis revealed the role of ARHGEF1 and its screened antagonist in mild and severe COVID-19 patients. J Cell Biochem. 2022;123:673–690. doi: 10.1002/jcb.30213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z-F, Zhang L, Shen J. MicroRNA: potential biomarker and target of therapy in acute lung injury. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2020;39:1429–1442. doi: 10.1177/0960327120926254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Kawai T. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2014;5:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki M, Kuwano K, Hagimoto N, Matsuba T, Kunitake R, Tanaka T, Maeyama T, Hara N. Protection from lethal apoptosis in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice by a caspase inhibitor. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:597–603. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan AB, Torre D, Lachmann A, Leong AK, Wojciechowicz ML, Utti V, Jagodnik KM, Kropiwnicki E, Wang Z, Maayan A. ChEA3: transcription factor enrichment analysis by orthogonal omics integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W212–W224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MJ, Singh P, Dohare R, Jha R, Rahmani AH, Almatroodi SA, Ali S, Syed MA. Inhibition of miRNA-34a promotes M2 macrophage polarization and improves LPS-induced lung injury by targeting Klf4. Genes. 2020;11:966. doi: 10.3390/genes11090966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W-Y, Hong S-B. Sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome: recent update. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2016;79:53. doi: 10.4046/trd.2016.79.2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura Y, Hashimoto S, Mizuta N, Kobayashi A, Kooguchi K, Fujiwara I, Nakajima H. Fas/FasL-dependent apoptosis of alveolar cells after lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:762–769. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2003065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremserova S, Perecko T, Soucek K, Klinke A, Baldus S, Eiserich JP, Kubala L. Lung neutrophilia in myeloperoxidase deficient mice during the course of acute pulmonary inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:5219056. doi: 10.1155/2016/5219056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R, Kumar R, Open Source Drug Discovery Consortium. Lynn A. g_mmpbsa —a GROMACS tool for high-throughput MM-PBSA calculations. J Chem Inf Model. 2014;54:1951–1962. doi: 10.1021/ci500020m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang JD, Matute-Bello G. Lymphocytes, apoptosis and sepsis: making the jump from mice to humans. Crit Care. 2009;13:109. doi: 10.1186/cc7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Wei C, Cai S, Fang L. TRPM7 modulates macrophage polarization by STAT1/STAT6 pathways in RAW264.7 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;533:692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Sheng Q, Zhang C, Han C, Bai H, Lai P, Fan Y, Ding Y, Dou X. STAT6 up-regulation amplifies M2 macrophage anti-inflammatory capacity through mesenchymal stem cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;91:107266. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Y-J, Liu X-P, Chen S-S, Zong D-D, Chen Y, Chen P. miR-34a is involved in CSE-induced apoptosis of human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells by targeting Notch-1 receptor protein. Respir Res. 2018;19:21. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0722-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan Y, Yao Y, Xiao X, Sheng Z. Insights into the apoptotic death of immune cells in sepsis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2015;35:17–22. doi: 10.1089/jir.2014.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeyama T, Kuwano K, Kawasaki M, Kunitake R, Hagimoto N, Matsuba T, Yoshimi M, Inoshima I, Yoshida K, Hara N. Upregulation of Fas-signalling molecules in lung epithelial cells from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:180. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17201800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TR, Hagimoto N, Nakamura M, Matute-Bello G. Apoptosis and epithelial injury in the lungs. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:214–220. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-031AC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2731–2740. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen ME, Shah CV, Meyer NJ, Gaieski DF, Lyon S, Miltiades AN, Goyal M, Fuchs BD, Bellamy SL, Christie JD. The epidemiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients presenting to the emergency department with severe sepsis. Shock. 2013;40:375–381. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182a64682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan M, Kumar V, Lackner AA, Alvarez X. Dysregulated miR-34a–SIRT1–acetyl p65 axis is a potential mediator of immune activation in the colon during chronic simian immunodeficiency virus infection of rhesus macaques. J Immunol. 2015;194:291–306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro F, Lieberman J. miR-34 and p53: new insights into a complex functional relationship. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepal S, Tiruppathi C, Tsukasaki Y, Farahany J, Mittal M, Rehman J, Prockop DJ, Malik AB. STAT6 induces expression of Gas6 in macrophages to clear apoptotic neutrophils and resolve inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:16513–16518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821601116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton K, Dixit VM. Signaling in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a006049–a006049. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, Peng C. Overview of MicroRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:402. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata-Suetsugu S, Yanagihara T, Hamada N, Ikeda-Harada C, Yokoyama T, Suzuki K, Kawaguchi T, Maeyama T, Kuwano K, Nakanishi Y. Amphiregulin suppresses epithelial cell apoptosis in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;484:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Nascimento L, Massari P, Wetzler LM. The role of TLR2 in infection and immunity. Front Immun. 2012 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oteiza L, Ferruelo A, Nín N, Arenillas M, de Paula M, Pandolfi R, Moreno L, Herrero R, González-Rodríguez P, Peñuelas Ó, Pérez-Vizcaíno F, Lorente JA. Serum MicroRNAs as biomarkers of sepsis and resuscitation. Appl Sci. 2021;11:11549. doi: 10.3390/app112311549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perl M, Chung C-S, Perl U, Lomas-Neira J, de Paepe M, Cioffi WG, Ayala A. Fas-induced pulmonary apoptosis and inflammation during indirect acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:591–601. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1743OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T, Rubenfeld GD. Fifty years of research in ARDS. The epidemiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome. A 50th birthday review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:860–870. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201609-1773CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radstake TRDJ, Roelofs MF, Jenniskens YM, Oppers-Walgreen B, van Riel PLCM, Barrera P, Joosten LAB, van den Berg WB. Expression of toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in rheumatoid synovial tissue and regulation by proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-12 and interleukin-18 via interferon-? Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3856–3865. doi: 10.1002/art.20678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendran K, Napolitano LM. Definition of ALI/ARDS. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Cruz NE, Maldonado Bernal C, Cuevas Urióstegui ML, Castañoń J, López Macías C, Isibasi A. Toll-like receptors: dysregulation in vivo in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Rev Alerg Mex. 2004;51:210–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rello J, Valenzuela-Sánchez F, Ruiz-Rodriguez M, Moyano S. Sepsis: a review of advances in management. Adv Ther. 2017;34:2393–2411. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0622-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47–e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh JS, Sohn DH. Damage-associated molecular patterns in inflammatory diseases. Immune Netw. 2018;18:e27. doi: 10.4110/in.2018.18.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L. Complexity of danger: the diverse nature of damage-associated molecular patterns. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:35237–35245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.619304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schissel SL, Levy BD. Acute lung injury (ALI) and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) In: Lubin MF, Smith RB, Dodson TF, Spell NO, Walker HK, editors. Medical management of the surgical patient. Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty SK, Tiwari N, Marudamuthu AS, Puthusseri B, Bhandary YP, Fu J, Levin J, Idell S, Shetty S. p53 and miR-34a feedback promotes lung epithelial injury and pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:1016–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson MI, Sigvaldason K, Gunnarsson TS, Moller A, Sigurdsson GH. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: nationwide changes in incidence, treatment and mortality over 23 years: ARDS incidence and survival. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:37–45. doi: 10.1111/aas.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn D, Sokolove J, Sharpe O, Erhart JC, Chandra PE, Lahey LJ, Lindstrom TM, Hwang I, Boyer KA, Andriacchi TP, Robinson WH. Plasma proteins present in osteoarthritic synovial fluid can stimulate cytokine production via Toll-like receptor 4. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R7. doi: 10.1186/ar3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sticht C, De La Torre C, Parveen A, Gretz N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0206239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Gong X, Purow B, Zhao Z. Uncovering MicroRNA and transcription factor mediated regulatory networks in glioblastoma. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, Das P, Pawar A, Aghai ZH, Kaskinen A, Zhuang ZW, Ambalavanan N, Pryhuber G, Andersson S, Bhandari V. Hyperoxia causes miR-34a-mediated injury via angiopoietin-1 in neonatal lungs. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1173. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01349-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilágyi B, Fejes Z, Pócsi M, Kappelmayer J, Nagy B. Role of sepsis modulated circulating microRNAs. EJIFCC. 2019;30:128–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Akira S. TLR signaling pathways. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugal D, Liao X, Jain MK. Transcriptional control of macrophage polarization. ATVB. 2013;33:1135–1144. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tundup S, Srivastava L, Chandora K, Harn D. Mir-34a regulates macrophage polarization by targeting IL-4Ralpa/STAT6 axis (INM2P.423) J Immunol. 2014;192:56.6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.192.Supp.56.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tzotzos SJ, Fischer B, Fischer H, Zeitlinger M. Incidence of ARDS and outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a global literature survey. Crit Care. 2020;24:516. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03240-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco-Torres Y, Ruiz-López V, Pérez-Bautista O, Buendía-Roldan I, Ramírez-Venegas A, Pérez-Ramos J, Falfán-Valencia R, Ramos C, Montaño M. miR-34a in serum is involved in mild-to-moderate COPD in women exposed to biomass smoke. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19:227. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0977-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Yao J, Li Z, Zu G, Feng D, Shan W, Li Y, Hu Y, Zhao Y, Tian X. miR-34a-5p inhibition alleviates intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced reactive oxygen species accumulation and apoptosis via activation of SIRT1 signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;24:961–973. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H-F, Li Y, Wang Y-Q, Li H-J, Dou L. MicroRNA-494–3p alleviates inflammatory response in sepsis by targeting TLR6. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:2971–2977. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201904_17578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang L, Xi X, Zhou J-X, China Critical Care Sepsis Trial (CCCST) Workgroup The association between etiologies and mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicenter observational cohort study. Front Med (lausanne) 2021;8:739596. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.739596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Lowenstein CJ. miR-34a repression of SIRT1 regulates apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13421–13426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801613105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, Yu T, Wang Y, Pan S, Zou X, Yuan S, Shang Y. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]