Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the efficacy of infliximab (IFX, 5–10 mg/kg) (Group 1) and tocilizumab (TCZ, 4–8 mg/kg) (Group 2) infusions in non-infectious retinal vasculitis (RV) using Angiographic Scoring for the Uveitis Working Group fluorescein angiography (FA) scoring system.

Methods

Records of 14 patients (24 eyes) in Group 1 and 8 patients (11 eyes) in Group 2 were retrospectively evaluated to assess visual acuity (VA), anterior chamber cell and flare, vitreous haze, central subfield thickness (CST), and FA scoring at baseline and 6 months of follow-up. The measurements were employed to grade in each group.

Results

In Group 1 and 2, respectively, there was no underlying disease in 9 (60%) and 3 (42.9%) patients. Three (42.9%) patients in Group 2 had juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) as the most common identified cause. Mean improvement in VA (log MAR) and CST were 0.04 ± 0.14 and 40.3 ± 78.5 µm in Group 1; 0.04 ± 0.09 and 47.3 ± 82.3 µm in Group 2, respectively. Mean FA scores were significantly reduced from 12.4 ± 5.2 and 11.6 ± 4.4 at baseline to 6.4 ± 5.0 and 5.8 ± 3.9 at 6-month in Group 1 and 2, respectively. In Group 2, 9 eyes of 6 patients (75%) had the history of IFX use prior to TCZ initiation. There was no significant safety concern requiring treatment discontinuation during the follow-up in either group.

Conclusion

IFX and TCZ infusions showed statistically significant improvement of non-infectious RV as shown by ASUWOG FA Scoring System. TCZ, as well as IFX, appeared to be effective treatment options for non-infectious RV.

Subject terms: Uveal diseases, Drug therapy

Introduction

Retinal vasculitis (RV) is a challenging diagnosis that is defined by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group as the presence of retinal vascular changes coupled with ocular inflammation. Perivascular sheathing and vascular leakage or occlusion on fluorescein angiography (FA) were recognized as descriptive markers for RV by SUN [1]. RV can occur in a particular ocular or systemic disease setting, either infectious or non-infectious, and can also be observed as an idiopathic condition with no apparent cause [2]. Non-infectious RV is a rare, heterogeneous clinical condition characterized by the inflammatory involvement of retinal vasculature and diagnosed with the exclusion of possible infectious aetiologies. It may result in sight-threatening consequences via vascular leakage, ischemia, macular oedema, occlusion, and neovascularization [3]. Hence, prompt diagnosis and timely, optimum treatment are essential in the management of non-infectious RV and prevention of severe vision loss.

In addition to documentation of perivascular sheathing, hemorrhages, and alterations in vascular configurations on clinical examination, FA provides more of a comprehensive insight into the origin of inflammation, its extent, and associated complications. It enables detailed assessment of retinal vasculature and reveals inflammation even at the subclinical level. Furthermore, FA is useful in monitoring disease activity and treatment response objectively [4, 5]. However, FA findings are generally described in a subjective manner in clinical practice, which is compelling in terms of comparability of data across time and between different patient or treatment groups. As a result, numerous FA scoring methods have previously been described in the literature [6]. Recently, the Angiographic Scoring for the Uveitis Working Group (ASUWOG) introduced a semi-quantitative scoring scheme utilizing FA and indocyanine green angiography to determine the extent of retinal and choroidal inflammation in uveitis [5], which has since been used in several clinical studies [7–9].

In non-infectious RV, treatment mainly consists of corticosteroids followed by immunomodulatory therapies (IMT) as steroid-sparing agents thereafter. Although various conventional medications, including methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, and azathioprine, can be used with success [10, 11], biologic agents provide promising results, particularly in patients with disease refractory to standard treatment [12–14]. Recently, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors such as infliximab (IFX) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitor like tocilizumab (TCZ) have been reported to be effective in the treatment of recalcitrant cases [13–17]. Fabiani et al. [16] compared the efficacy of adalimumab (ADA) and IFX in patients with refractory RV and demonstrated similar excellent results in terms of RV resolution. Additionally, there is mounting evidence on the efficacy of TCZ in refractory uveitis, even in patients whose diseases have failed to respond to TNF-α inhibitors [15, 18, 19]. To date, no study has objectively compared the efficacy of TNF-α inhibitors and IL-6 inhibitors in treating non-infectious RV. Hence, the present study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of IFX and TCZ infusions in patients with non-infectious RV using the ASUWOG FA scoring system.

Materials and methods

A retrospective chart review was performed using the Stanford Research Repository (STARR) tool to identify non-infectious RV patients who presented at the Byers Eye Institute of Stanford University between 2017 and 2021. Patients treated either with IFX or TCZ infusions for at least six (6) months with active disease or high risk for relapse were enrolled in the study. Non-infectious RV was diagnosed based on comprehensive eye examination and FA. Patients classified as high-risk were those who had persistent inflammation documented on FA while receiving other immunomodulatory therapies (IMT) prior to initiation of IFX or TCZ. The exclusion criteria were the presence of other aetiologies for RV (i.e., infectious, Eales disease), diabetic retinopathy, uncontrolled hypertension, retinal vascular occlusion, ocular ischemic syndrome, hemoglobinopathies, ocular or systemic malignancies, media opacities and/or small pupil precluding FA (OPTOS Plc, Dunfermline, UK) and OCT (Heidelberg Spectralis HRA + OCT device, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany), and history of vitreoretinal surgery. Baseline complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were performed and repeated every two months during the follow-up. Patients were also screened for tuberculosis by QuantiFERON gold tuberculosis test before biologic agent initiation. In the IFX-treated group (Group 1), IFX infusions were given at a dose of 5–10 mg/kg as monthly infusions with no loading dose, while in the TCZ-treated group, TCZ infusions were administered at a rate of 4–8 mg/kg per month. In addition to IFX or TCZ, intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone (MP) (250–1000 mg/day) for 1-3 days every month was added to the initial treatment regimen in some patients to augment the anti-inflammatory management.

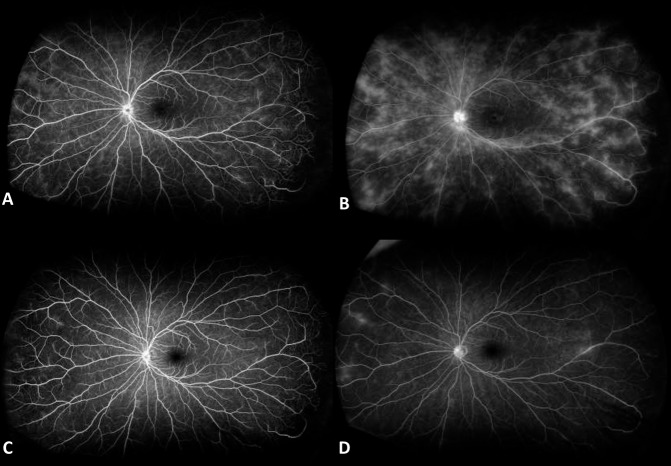

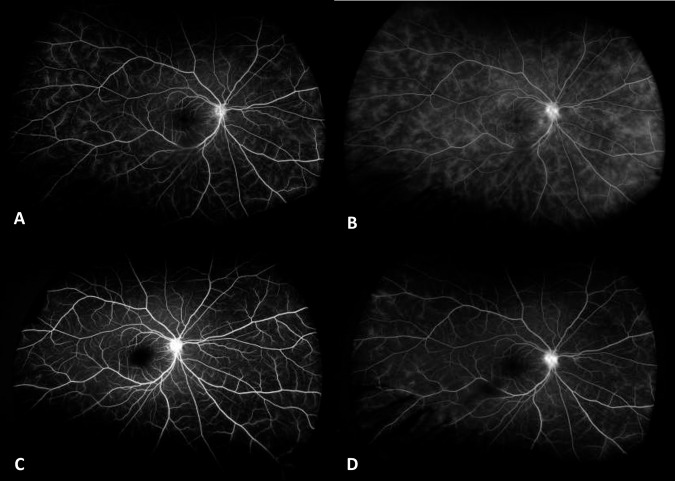

The medical records of patients were reviewed for age, gender, underlying ocular and/or systemic disease, and treatment history. Visual acuity (VA), anterior chamber (AC) cells and flare, vitreous haze (VH) using the SUN classification system [1] by slit-lamp examination (QDN), central subfield thickness (CST) on OCT, and FA scores at baseline and 6th month were recorded. CST was calculated automatically by the OCT software. The ASUWOG system was utilized for FA scoring of all patients which assigns a total score of 40 to several indicators of inflammation on FA [5]. Two independent masked graders (IK and GU) evaluated the FA images. Presence of macular and optic disc leakage on FA were noted as the “presence of cystoid macular oedema (CMO)” and “Optic disc involvement”, respectively. Representative baseline and 6th month FA images of 2 patients are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Baseline and 6th month measurements were compared in each treatment group, as well as between Groups 1 and 2.

Fig. 1. Fluorescein angiography images of a representative patient who received infliximab at baseline.

A Early phase and B late phase, and 6th month of follow-up C early phase and D late phase.

Fig. 2. Fluorescein angiography images of a representative patient who received tocilizumab at baseline.

A Early phase and B late phase, and 6th month of follow-up C early phase and D late phase.

The present study followed the Helsinki Declaration tenets, the United States Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, and the Harmonized Tripartite Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (1996). The Stanford University Institutional Review Board approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from each patient. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were performed to compare data between Groups 1 and 2, as well as Baseline and 6-month data. Inter- and intra- eye correlation were also accounted for in the statistical analysis using GEE. To account for intra- eye correlation, bilateral vs unilateral were included as a factor into GEE model in the analyses. The inter- eye correlation with drug selection or two time points was also evaluated as the presence of interaction in the model in each analysis. GEE Type of Model was appropriately selected based on the data characteristics in each analysis, as well. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all p values were two-sided.

Results

This non-randomized, retrospective, observational study included 35 eyes of 22 patients with non-infectious RV who were treated with IFX (Group 1, 24 eyes of 14 patients) or TCZ (Group 2, 11 eyes of 8 patients). The mean age was 23.8 ± 19.8 (range, 7–71) years in Group 1, and 15.6 ± 7.5 (range, 7–41) years in Group 2 (p = 0.382). Table 1 shows the demographics and clinical characteristics of Groups 1 and 2. There was no identified ocular or systemic cause for RV in 14 and five eyes of seven (50%) and three (37.5%) patients in Groups 1 and 2, respectively. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) was the most identified underlying disease in Group 2 (four patients (50%), five eyes), whereas two patients (14.3%, two eyes) had JIA in Group 1. Five patients (35.7%, seven eyes) in Group 1 and seven patients (87.5%, ten eyes) in Group 2 had history of prior IMT use including azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, ADA and IFX (Table 1). For these patients, IFX and TCZ were started without wash-out period due to insufficient response to ongoing prior therapy based on the clinical findings and/or persistent leakage on FA.

Table 1.

Demographic features and clinical characteristics of patients in the study population.

| Group 1 (IFX) (n = 24 eyes) | Group 2 (TCZ) (n = 11 eyes) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female/Male) | 9/5 | 5/3 | 0.564 |

| Race [% (n)] | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 42.9% (6) | 87.5% (7) | 0.028 |

| Non-Hispanic/Non-Latino | 57.1% (8) | 12.5% (1) | |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 23.8 ± 19.8 (7–71) | 15.6 ± 7.5 (7–41) | 0.818 |

| Laterality of disease [% (n) patients] | |||

| Bilateral | 85.7% (12) | 75% (6) | 0.602 |

| Unilateral | 16.7% (2) | 25% (2) | |

| Lens status [% (n) phakic] | 91.6% (22) | 72.7% (8) | 0.309 |

| Prior IMT use [% (n)] | 29.2% (7) | 90.9% (10) | 0.023 |

| Azathioprine | 4.2% (1) | - | |

| Methotrexate | 4.2% (1) | 36.4% (5) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 12.5% (3) | - | |

| Filgotinib | 8.3% (2) | - | |

| Adalimumab | 8.3% (2) | 36.4% (5) | |

| Infliximab | - | 81.8% (9) | |

| Corticotropin gel | 4.2% (1) | - | |

| Disease type [% (n)] | 0.241 | ||

| Anterior uveitis | 8.3% (2) | 27.3% (3) | |

| Intermediate uveitis | 12.5% (3) | 27.3 % (3) | |

| Posterior uveitis | 25.0% (6) | 18.2% (2) | |

| Panuveitis | 54.2% (13) | 27.3% (3) | |

| Underlying disease [% (n)] | 0.028 | ||

| Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis | 8.3% (2) | 45.5% (5) | |

| HLA-B27-associated spondyloarthropathy | 4.2% (1) | 9.1% (1) | |

| Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease | 8.3% (2) | - | |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis | 8.3% (2) | - | |

| Cold agglutinin disease | 8.3% (2) | - | |

| Sympathetic ophthalmia | 4.2% (1) | - | |

| Idiopathic | 58.3% (14) | 45.5% (5) | |

| IV Methylprednisolone usage | |||

| Number of patients [% (n)] | 85.7% (12) | 87.5% (7) | 0.786 |

| Duration of treatment (month) | 4.8 ± 2.2 (0–6) | 4.8 ± 2.4 (0–6) | 0.934 |

| Cumulative dose (mg/kg/patient) | 164.3 ± 123.9 (0–450) | 83.1 ± 75.4 (0–240) | 0.102 |

All patients, regardless of the (disease) type of uveitis, had retinal vasculitis with documented findings on fluorescein angiography.

IFX Infliximab, TCZ Tocilizumab, SD Standard deviation, IMT Immunomodulatory therapy, IV Intravenous.

Bold values represent significant p value.

IFX was started as IV infusions at 5 mg/kg in 11 eyes of six patients, 7.5 mg/kg in 12 eyes of seven patients, and 10 mg/kg in one eye of one patient. At the 3rd and 6th month follow-up, four eyes (16.7%) of two patients and five eyes (20.8%) of three patients required dose increase to 7.5 and 10 mg/kg due to persisting severe inflammation demonstrated on FA, respectively. TCZ was initiated as IV infusions at 4 mg/kg and increased to 8 mg/kg in four eyes (36.4%) of three patients, whereas it was given at 8 mg/kg in seven eyes (63.6%) of five patients. Twelve patients (85.7%) in IFX group and seven patients (87.5%) in TCZ group received the respective infusions along with IV methylprednisolone (MP) (250–1000 mg/day) for 1–3 days every month for at least 3 months. In Groups 1 and 2, the cumulative dose for IV MP was 164.3 ± 123.9 (0–450) mg/kg/patient and 83.1 ± 75.4 (0–240) mg/kg/patient, respectively (p = 0.303). The mean duration for IV MP therapy was 4.8 ± 2.2 (0–6) months in Group 1 and 4.8 ± 2.4 (0–6) months in Group 2 (p = 0.810). In addition, five patients (35.7%, eight eyes) in Group 1 and five patients (62.5%, seven eyes) in Group 2 received concomitant IMT with IFX or TCZ infusions during the follow-up, respectively. Additional IMTs included azathioprine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil. There was no patient who received local steroid therapy including subtenon triamcinolone injection, intravitreal dexamethasone or fluocinolone acetate implants. No patient experienced a significant safety concern requiring treatment discontinuation during the 6-month follow-up.

The mean improvement in VA at 6 months was 0.04 ± 0.14 log MAR in Group 1 and 0.04 ± 0.09 log MAR in Group 2. VA improved in 14 (58.3%) and 4 (50%) eyes and was stable in 10 (41.7%) and 4 (50%) eyes in Group 1 and 2, respectively. The mean improvement in CST at 6 months was 40.3 ± 78.5 µm in Group 1 (p < 0.001) and 47.3 ± 82.3 µm in Group 2 (p = 0.010). The difference in CST improvement between the two groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.367). CMO was observed in 7 and 5 eyes, of which 4 and 4 eyes showed complete resolution of CMO in Group 1 and 2 at 6th month, respectively. No vitreomacular traction was noted in any patient. In Group 1, the mean FA score significantly reduced from 12.4 ± 5.2 at baseline to 6.4 ± 5.0 at 6 months (p < 0.001) (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 1). In Group 2, the mean FA score significantly decreased from 11.6 ± 4.4 at baseline to 5.8 ± 3.9 at 6 months (p = 0.001) (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 2). In Groups 1 and 2, respectively, 12 (50%) eyes and 5 (45.5%) eyes showed >50% improvement in their FA score compared to baseline. At month 6, there was one eye of one patient in each group which showed complete resolution of the RV with a FA score of 0. Also, there were 10 out of 24 eyes in Group 1, and 4 out of 11 eyes in Group 2 which had a FA score <4 at 6th month. There was no patient with unchanged or worsened FA score at 6 months in either group. The difference in mean improvement of FA scores between Groups 1 and 2 was statistically insignificant (p = 0.923).

Table 2.

Baseline and 6th month clinical characteristics of patients treated with infliximab.

| Baseline (mean ± SD) (Median, range) | 6th month (mean ± SD) (Median, range) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Acuity (log MAR) | 0.19 ± 0.21 (0.1, 0–0.8) | 0.15 ± 0.26 (0.1, 0–0.8) | 0.086a |

| AC cells (0-4) | 0.35 ± 0.71 (0, 0–3) | 0.02 ± 0.10 (0, 0–1) | 0.022b |

| AC flare (0-4) | 0.79 ± 0.51 (1, 0–2) | 0.54 ± 0.41 (0.5, 0–2) | 0.008b |

| Vitreous haze (0-4) | 0.44 ± 0.49 (0, 0–1) | 0.17 ± 0.32 (0, 0–1) | 0.053b |

| CST (μm) | 328.3 ± 113.6 (297, 202–683) | 287.9 ± 74.3 (277, 194–581) | <0.001a |

| FA score | 12.4 ± 5.2 (13, 3–21) | 6.4 ± 5.0 (6, 0–17) | <0.001a |

| Presence of CMO | 29.2% (7) | 12.5% (3) | 0.037c |

| Optic Disc involvement | 87.5% (21) | 50.0% (12) | 0.002c |

SD Standard deviation, AC Anterior chamber, CST Central subfield thickness, FA Fluorescein angiography, CMO Cystoid macular oedema.

aGEE with linear regression model.

bGEE with ordinal logistic model.

cGEE with binary logistic model.

Bold values represent significant p value.

Table 3.

Baseline and 6th month clinical characteristics of patients treated with tocilizumab.

| Baseline (mean ± SD) (Median, range) | 6th month (mean ± SD) (Median, range) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Acuity (log MAR) | 0.46 ± 0.46 (0.3, 0–1.2) | 0.43 ± 0.45 (0.3, 0-1.2) | 0.122a |

| AC cells (0–4) | 0.27 ± 0.65 (0, 0–2) | 0.0 ± 0.00 (0) | 0.142b |

| AC flare (0–4) | 1.27 ± 0.60 (1.5, 0–2) | 0.65 ± 0.24 (0.5, 0-1) | 0.001b |

| Vitreous haze (0–4) | 0.14 ± 0.32 (0, 0–1) | 0.22 ± 0.51 (0, 0-1) | 0.723b |

| CST (μm) | 353.2 ± 97.3 (323, 251-524) | 299.1 ± 36.8 (289, 250-373) | 0.010a |

| FA score | 11.6 ± 4.4 (12, 4-17) | 5.8 ± 3.9 (6, 0-14) | 0.001a |

| Presence of CMO | 45.5% (5) | 9.1% (1) | 0.038c |

| Optic disc involvement | 90.9% (10) | 63.6% (7) | 0.073c |

SD Standard deviation, AC Anterior chamber, CST Central subfield thickness, FA Fluorescein angiography, CME Cystoid macular oedema.

aGEE with linear regression model.

bGEE with ordinal logistic model.

cGEE with binary logistic model.

Bold values represent significant p value.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that both IFX and TCZ resulted in significant resolution of RV at 6 months, as objectively shown by the ASUWOG FA scoring system. In addition, the efficacy of IFX and TCZ infusions were comparable in terms of significant improvement of inflammation at 6 months in patients with non-infectious RV. To the best of our knowledge, the index study is the first to assess the efficacy of IFX and TCZ infusions in treating non-infectious RV altogether in the 2 groups studies. Overall, nearly half of the patients in both groups demonstrated >50% improvement in their FA score at 6th month which supported the clinical effectiveness of both IFX and TCZ in this population.

Rapid and maintained efficacy of treatment is critical for non-infectious RV to avoid relapse and associated irreversible, severe functional loss. After the approval of ADA for the treatment of non-infectious uveitis by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016, several treatment strategies, including those with other TNF-α inhibitor IFX and IL-6 inhibitor TCZ, have been increasingly utilized particularly for the treatment of refractory inflammation. IFX has been shown to be effective in the treatment of refractory Adamantiades-Behçet’s uveitis, JIA, Takayasu disease, and idiopathic uveitis [12, 20, 21], even when failed with ADA [22, 23]. Sharma et al. [13] demonstrated that IFX (5 mg/kg in 95%) is an effective drug for the treatment of recalcitrant RV, with 59 out of 60 (98.3%) patients having a good and relatively quick treatment response on FA within 3 months. Nine patients withdrew from the study prior to 6 months, 3 discontinued IFX due to side effects, 1 was discontinued due to treatment failure, and 5 patients were lost to follow up due to other extenuating circumstances. At 6 months, 45 of 51 (88.23%) patients were maintaining remission with IFX, 5 (9.8%) were in partial remission, and 1 patient had failed. Fabian et al. [16] compared the efficacy of IFX and ADA in recalcitrant RV with no significant difference in terms of complete RV resolution between the two drugs. The percentages of patients achieving RV remission within 3 and 12 months were 54% and 86%, respectively. Recently, Maleki et al. [23] demonstrated that either TNF-α inhibitor, ADA or IFX, can be used to treat patients with idiopathic inflammatory retinal vascular leakage who have failed to respond to one of the other agents.

On the other hand, TCZ, which is a recombinant monoclonal antibody against IL-6 receptor, has also been increasingly reported as a safe and effective treatment option for refractory uveitis involving Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease, JIA, and relapsing polychondritis [15, 24–26]. Although TCZ is currently an off-label drug for uveitis, it has been demonstrated to be beneficial in treating uveitic patients, including those with disease refractory to TNF-α inhibitors [14, 17, 19]. No study has evaluated the efficacy of TCZ specifically in non-infectious RV. In the series of Ozturk et al. [14], 8 mg/kg TCZ monthly infusions were given to refractory Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease patients who had failed treatment with TNF-α inhibitors and interferon-α, with the follow-up ranging from 5–19 months. Favorable response, indicated as reduction in AC laser flare meter values, central macular thickness (CMT) and FA scores, was demonstrated mostly after 6 months. They proposed that TCZ appears to be a powerful option with the variable onset of action, as it was used after the failure of other biologic agents. However, the authors reported that none of the patients had complete resolution of leakage (“dry FA”). Therefore, they underlined the importance of long-term treatment to achieve complete subsidence of inflammation. Calvo-Rio et al. [17] has also reported successful results with TCZ, involving VA improvement, reduction in AC cells and CMT, in 25 patients with severe JIA-associated uveitis (8 and 3 patients failed with ADA and IFX, respectively) in which some patients had manifestations of RV. In another study indicating the efficacy of TCZ with complete remission in 8 out of 11 patients in refractory uveitis of Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease, eight and four patients had a history of ADA and IFX use, respectively [15]. In our present study, among the non-infectious RV patients treated with TCZ, there were four patients with history of ADA usage, two of whom failed and two of whom had side effects; there were six patients with history of IFX usage, three of whom failed and three of whom had side effects. On the other hand, among the non-infectious RV patients treated with IFX, there were two patients who failed with ADA and no patient was noted with the history of TCZ usage prior to initiation of IFX.

In the present study, both IFX and TCZ infusions improved AC reaction and CST measurements. Approximately one third of the patients showed VA improvement by ≥ two lines at the 6-month of follow-up, despite insignificant change in VA which can be explained by the patients mostly being phakic, relatively short follow-up time, and small number of patients with CMO. Additionally, as reported in the literature [17, 24, 27, 28], CST measurements on OCT significantly reduced in both IFX and TCZ groups. The complete resolution of CMO was observed in 4 out of 7 eyes and 4 out of 5 eyes of patients treated with IFX and TCZ, respectively. In addition, both IFX and TCZ demonstrated statistically significant improvement of FA score at the 6-month mark, despite no statistically significant change in VA. The presence of persistent leakage from retinal capillaries when the patient is clinically quiet carries a risk for relapses and complications. Therefore, the concomitant use of both objective FA scoring and other clinical features is of crucial importance for meticulous evaluation of non-infectious RV. Moreover, given there is no consensus on the optimum duration of treatment and variable onset of action, the improving trend in FA scores at six-months of therapy also supported that long-term sustained treatment might be useful in non-infectious RV, a challenging disease, to accomplish the fullest potential of drugs and better control of inflammation.

In addition, as an important point, the present study employed reliable semi-quantitative FA scoring system to objectively assess the alterations during the follow-up of all patients, as well as in between groups. Previous studies assessing the efficacy of IFX or TCZ usually employed discrete parameters like complete/partial remission, or active/inactive disease on FA [13, 15, 16], and only few studies used FA scoring [8, 9, 19]. However, we strongly believe that such a large-scale FA scoring system provides a detailed and less biased assessment and should be used more frequently to monitor ocular inflammatory diseases including non-infectious RV.

Most of the patients in each group were also receiving IV MP along with either IFX or TCZ during the 6-month follow-up. Certainly, MP can also contribute to the improvement of the RV. However, the confounding effect of MP would be the same for both groups since the comparison of number of patients, duration of therapy and cumulative doses were statistically insignificant. The fact that the majority of patients in both groups received IV MP is a significant limitation of this study, and remains a confounder as we cannot really gauge what treatment effect IV MP had, over and above the agents IFX and TCZ. Clinically, we have observed that MP alone often may not lead to remission in eyes with severe or refractory non-infectious RV. Hence, we have employed a biologic agent (IFX or TCZ) and added IV MP to achieve synergistic effects. In addition, long term treatment of these patients should not include high-dose corticosteroids, given its side effects.

There are some limitations of the present study including its non-randomized, retrospective design, small study group, relatively short-term data, and heterogenous population composed of both biologic-naïve and previously biologic-treated eyes. In the statistical method, GEE was applied to the analyses to account for inter- and intra- eye correlation. However, there is a discussion about a bias of GEE for small samples like in our preliminary study [29]. In addition, four (50%) patients in Group 2 had JIA as the most commonly identified underlying disease, whereas two patients had JIA in Group 1. Retrospective nature of the study particularly limited head-to-head comparison of IFX and TCZ. However, RV is a rare entity, and the clinical value of new treatment options in this challenging disease is of critical importance. Moreover, the real-life data put additional benefit to the outcomes from clinical trials for more realistic approach in the management. Inequal distribution of prior IMT use in between groups may have influenced the treatment outcomes by favouring IFX. Since the significant proportion of patients who received TCZ had a previous history of IFX use, comparable improvement in FA scores might be interpreted as TCZ could be even superior in head-to-head comparison with IFX. Besides, given the relatively better side effect profile [19, 30] of TCZ and potential development of anti-IFX antibodies [31], TCZ may be a viable alternative in patients who failed or experienced adverse effects from IFX. On the other hand, it is important to keep in mind that IFX is beneficial for significant resolution of RV in a variety of eyes. Nonetheless, each patient differs in his/her severity and activity of RV, as well as treatment need, and it is difficult to create perfectly homogeneous group of patients. In addition, our results supported the efficacy of both IFX and TCZ in significant resolution of non-infectious RV. Fabian et al. [16] also found no significant difference between biologic-naïve patients and those previously treated with biologics, as well as between patients co-administered with conventional medications and those treated with TNF-α inhibitor monotherapy. Additionally, different dosing regimens should be kept in our armamentarium when considering the efficacy of each drug, as starting with higher doses may result in a more complete and rapid resolution of inflammation. Lastly, neither IFX nor TCZ posed any substantial safety concerns in the index study, and both were well tolerated. However, long-term data of a larger population is required to unveil potential side effects of both IFX and TCZ.

In conclusion, therapy with IFX and TCZ infusions (as we do not have clear data on subcutaneous TCZ) showed significant improvement of non-infectious RV as shown by the ASUWOG FA Scoring System. TCZ, as well as IFX, appeared to be effective treatment options for non-infectious RV. In addition, TCZ may be considered as a potentially effective alternative treatment for patients with JIA-associated RV or those who failed IFX therapy. Future prospective, randomized studies comparing IFX and TCZ in a larger and homogeneous population utilizing different dose regimens and considering different concomitant IMTs will be helpful to generate additional data on the employment of TCZ and IFX for the management of non-infectious RV.

Summary

What was known before

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors such as infliximab (IFX) and interleukin-6 inhibitor like tocilizumab (TCZ) have been reported to be effective in the treatment of refractory cases with non-infectious retinal vasculitis (RV).

What this study adds

Both IFX and TCZ infusions showed statistically significant improvement of non-infectious RV objectively shown by fluorescein angiography scoring. TCZ might be an alternative in patients who failed with Infliximab.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

IK was supported by a grant from the International Council of Ophthalmology (ICO) Retina Research Foundation (RRF) Helmerich Fellowship Program, as the recipient of 2020 ICO-RRF Helmerich One-Year Fellowship Award. WM was supported by a grant from the Japan Eye Bank Association Oversea Research Program and Kobe University Long Term Oversea Visit Program for Young Researchers.

Author contributions

IK was responsible for conducting the research, designing the study, extracting and analyzing the data, interpreting the results, writing and revising the manuscript; GU contributed in extracting the data, editing and critical revision of the manuscript; WM was responsible for analyzing the data, interpreting the results, critical revision of the manuscript; JR was responsible for editing and revision of the manuscript; CO contributed in interpreting the data and critical revision of the manuscript; AM contributed in interpreting the data; MSH contributed to design of the study and data interpretation; MZ contributed in analyzing and interpreting the data; SL was responsible for extracting the data; AD was responsible for extracting the data; HG contributed in analyzing and interpreting the data, editing and critical revision of the manuscript; QDN was responsible for critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding

Research to Prevent Blindness Department Challenge Award and National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health P30 Award (EY026877) have been awarded to the Byers Eye Institute at Stanford University.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are only available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

QDN serves on the Scientific Advisory Board for Affibody, Acelyrin, and Regeneron. The remaining authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41433-022-02315-9.

References

- 1.Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT. Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working G. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu El-Asrar AM, Herbort CP, Tabbara KF. Retinal vasculitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13:415–33. doi: 10.1080/09273940591003828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Asrar AM, Herbort CP, Tabbara KF. A clinical approach to the diagnosis of retinal vasculitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30:149–73. doi: 10.1007/s10792-009-9301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciardella AP, Prall FR, Borodoker N, Cunningham ET., Jr Imaging techniques for posterior uveitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15:519–30. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000144386.05116.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tugal-Tutkun I, Herbort CP, Khairallah M, Angiography Scoring for Uveitis Working G. Scoring of dual fluorescein and ICG inflammatory angiographic signs for the grading of posterior segment inflammation (dual fluorescein and ICG angiographic scoring system for uveitis) Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30:539–52. doi: 10.1007/s10792-008-9263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suhler EB. A prospective trial of infliximab therapy for refractory uveitis: preliminary safety and efficacy outcomes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:903–12. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang HM, Lee SC. Long-term progression of retinal vasculitis in Behcet patients using a fluorescein angiography scoring system. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252:1001–8. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2637-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balci O, Jeannin B, Herbort CP., Jr Contribution of dual fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography to the appraisal of posterior involvement in birdshot retinochoroiditis and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2018;38:527–39. doi: 10.1007/s10792-017-0487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadiq MA, Hassan M, Afridi R, Halim MS, Do DV, Sepah YJ, et al. Posterior segment inflammatory outcomes assessed using fluorescein angiography in the STOP-UVEITIS study. Int J Retin Vitreous. 2020;6:47. doi: 10.1186/s40942-020-00245-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, Bodaghi B, Chamberlain AM, Gul A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of Behcet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1656–62. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.080432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenbaum JT, Sibley CH, Lin P. Retinal vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28:228–35. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvo-Río V, Blanco R, Beltrán E, Sánchez-Bursón J, Mesquida M, Adán A, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha therapy in patients with refractory uveitis due to Behcet’s disease: a 1-year follow-up study of 124 patients. Rheumatol (Oxf) 2014;53:2223–31. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma PK, Markov GT, Bajwa A, Foster CS. Long-Term Efficacy of Systemic Infliximab in Recalcitrant Retinal Vasculitis. Retina. 2015;35:2641–6. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eser Ozturk H, Oray M, Tugal-Tutkun I. Tocilizumab for the Treatment of Behcet Uveitis that Failed Interferon Alpha and Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Therapy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26:1005–14. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2017.1355471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atienza-Mateo B, Calvo-Rio V, Beltran E, Martinez-Costa L, Valls-Pascual E, Hernandez-Garfella M, et al. Anti-interleukin 6 receptor tocilizumab in refractory uveitis associated with Behcet’s disease: multicentre retrospective study. Rheumatol (Oxf) 2018;57:856–64. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fabiani C, Sota J, Rigante D, Vitale A, Emmi G, Lopalco G, et al. Efficacy of adalimumab and infliximab in recalcitrant retinal vasculitis inadequately responsive to other immunomodulatory therapies. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:2805–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4133-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvo-Río V, Santos-Gómez M, Calvo I, González-Fernández MI, López-Montesinos B, Mesquida M, et al. Anti-Interleukin-6 Receptor Tocilizumab for Severe Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis Refractory to Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy: A Multicenter Study of Twenty-Five Patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:668–75. doi: 10.1002/art.39940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muselier A, Bielefeld P, Bidot S, Vinit J, Besancenot JF, Bron A. Efficacy of tocilizumab in two patients with anti-TNF-alpha refractory uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19:382–3. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2011.606593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wennink RAW, Ayuso VK, de Vries LA, Vastert SJ, de Boer JH. Tocilizumab as an Effective Treatment Option in Children with Refractory Intermediate and Panuveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:21–25. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1712431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ucan Gunduz G, Yalcinbayir O, Cekic S, Yildiz M, Kilic SS. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Treatment in the Management of Pediatric Noninfectious Uveitis: Infliximab Versus Adalimumab. J Ocul Pharm Ther. 2021;37:236–40. doi: 10.1089/jop.2020.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos-Gómez M, Calvo-Río V, Blanco R, Beltrán E, Mesquida M, Adán A, et al. The effect of biologic therapy different from infliximab or adalimumab in patients with refractory uveitis due to Behcet’s disease: results of a multicentre open-label study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:S34–S40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashkenazy N, Saboo US, Abraham A, Ronconi C, Cao JH. Successful treatment with infliximab after adalimumab failure in pediatric noninfectious uveitis. J AAPOS. 2019;23:151 e1–151 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maleki A, Garcia CM, Asgari S, Manhapra A, Foster CS Response to the Second TNF-alpha Inhibitor (Adalimumab or Infliximab) after Failing the First One in Refractory Idiopathic Inflammatory Retinal Vascular Leakage. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021:1-10. 10.1080/09273948.2020.1869787. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sepah YJ, Sadiq MA, Chu DS, Dacey M, Gallemore R, Dayani P, et al. Primary (Month-6) Outcomes of the STOP-Uveitis Study: Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Patients With Noninfectious Uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;183:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maleki A, Manhapra A, Asgari S, Chang PY, Foster CS, Anesi SD. Tocilizumab Employment in the Treatment of Resistant Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Associated Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:14–20. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1817501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farhat R, Clavel G, Villeneuve D, Abdelmassih Y, Sahyoun M, Gabison E, et al. Sustained Remission with Tocilizumab in Refractory Relapsing Polychondritis with Ocular Involvement: A Case Series. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:9–13. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1763405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adán A, Mesquida M, Llorenç V, Espinosa G, Molins B, Hernández MV, et al. Tocilizumab treatment for refractory uveitis-related cystoid macular edema. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:2627–32. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2436-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vegas-Revenga N, Calvo-Rio V, Mesquida M, Adan A, Hernandez MV, Beltran E, et al. Anti-IL6-Receptor Tocilizumab in Refractory and Noninfectious Uveitic Cystoid Macular Edema: Multicenter Study of 25 Patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;200:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paul S, Zhang X. Small sample GEE estimation of regression parameters for longitudinal data. Stat Med. 2014;33:3869–81. doi: 10.1002/sim.6198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mesquida M, Molins B, Llorenc V, Sainz de la Maza M, Adan A. Long-term effects of tocilizumab therapy for refractory uveitis-related macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2380–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haraoui B, Cameron L, Ouellet M, White B. Anti-infliximab antibodies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who require higher doses of infliximab to achieve or maintain a clinical response. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:31–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are only available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.