Abstract

Objectives

To provide reference values of trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference (TLCPD) and reveal the association of TLCPD with systemic biometric factors.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 526 quasi-healthy subjects (including 776 eyes) who required lumbar puncture for medical reasons were selected from 4915 neurology inpatients from 2019 to 2022. Patients with any diseases affecting intraocular pressure (IOP) or intracranial pressure (ICP) were excluded. The ICPs of all subjects were obtained by lumbar puncture in the left lateral decubitus position. IOP was measured in the seated position by a handheld iCare tonometer prior to lumbar puncture. TLCPD was calculated by subtracting ICP from IOP. Systemic biometric factors were assessed within 1 h prior to TLCPD measurement.

Results

The TLCPD (mean ± standard deviation) was 4.4 ± 3.6 mmHg, and the 95% reference interval (defined as the 2.5th–97.5th percentiles) of TLCPD was −2.27 to 11.94 mmHg. The 95% reference intervals for IOP and ICP were 10–21 and 6.25–15.44 mmHg, respectively. IOP was correlated with ICP (r = 0.126, p < 0.001). TLCPD was significantly negatively correlated with body mass index (r = −0.086, p = 0.049), whereas it was not associated with age, gender, height, weight, blood pressure, pulse, or waist and hip circumference.

Conclusions

This study provides reference values of TLCPD and establishes clinically applicable reference intervals for normal TLCPD. Based on association analysis, TLCPD is higher in people with lower BMI.

Subject terms: Optic nerve diseases, Physical examination, Epidemiology

Introduction

Intraocular pressure (IOP) and intracranial pressure (ICP) are two separate fluid pressures, and their association is controversial [1, 2]. The imbalance between IOP and ICP has received considerable attention in various ophthalmic and neurological diseases including glaucoma, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome, Terson syndrome, high-altitude retinopathy [3]. ICP governs the optic nerve subarachnoid space pressure (ONSP), and the imbalance between ONSP and IOP across the lamina cribrosa affects the structures and functions of the optic nerve head and optic nerve [1]. The difference between IOP and ONSP on both sides of the lamina cribrosa is called the trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference (TLCPD), which is an important parameter for evaluating the above-mentioned diseases. Because ONSP is difficult to measure directly in humans, TLCPD is often defined as the difference between IOP and ICP in research studies and clinical applications [4–6].

TLCPD has been used as a parameter in numerous ophthalmic and neurological studies as well as in clinical applications. However, the absence of TLCPD reference intervals creates confusion. Normal-tension glaucoma (NTG), a major glaucoma type, is associated with abnormally high TLCPD [4, 7–9]. However, abnormally high TLCPD is not present in all NTG patients [5, 10]. Abnormal TLCPD in individuals with NTG must be determined based on a reference interval. Papilledema is commonly seen in diseases with elevated ICP represented by IIH, although not all cases of elevated ICP are accompanied by papilledema [11]. Some patients with normal ICP may also develop papilledema due to low IOP [12]. Thus, when considering the above diseases, knowing whether the TLCPD is in the normal range is more informative than considering IOP or ICP values alone.

Numerous population-based studies have reported reference intervals for IOP and ICP in healthy and quasi-healthy subjects and analysed the associations between systemic biometric factors and IOP or ICP [13–16]. Unfortunately, no population-based studies have focused on TLCPD and its associated factors. At present, we can only estimate the TLCPD reference interval as 3–8 mmHg based on the reported reference intervals of IOP and ICP. Morgan et al. and Balaratnasingam et al. estimated a trans-laminar cribrosa pressure gradient of 20–33 mmHg/mm using human donor eyes and dog eyes [17–19]. In two population studies, Jonas et al. explored the association of systemic biometric factors with estimated TLCPD values predicted using the ICP prediction formula [20, 21]. While the results of these studies are interesting, more evidence from population-based studies is needed for clinical application. In the current study, we simultaneously measured IOP and ICP in quasi-healthy subjects (subjects with minor health issues that do not affect IOP or ICP). The findings provide TLCPD reference intervals for clinical applications. Moreover, we identified the systemic biometric factors that influence TLCPD and may affect related diseases.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted at two university-affiliated hospitals: Tongren Hospital and Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China. The study participants were quasi-healthy individuals recruited between September 2019 and March 2022 in the neurology departments of the two hospitals. All subjects required lumbar puncture for disease diagnosis. Participants gave written informed consent prior to the study. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was registered at http://www.chictr.org.cn (registration number: ChiCTR2100051713). The Medical Ethics Committees of the Beijing Tongren Hospital approved the study protocol.

All participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) 18 years of age or older; (2) lumbar puncture required for medical reasons; (3) consented to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) discharge diagnosis affecting IOP or ICP (two neurology specialists, YPW and JWW, and their team provided patients with a discharge diagnosis based on comprehensive examinations); (2) unclear diagnosis at discharge; (3) admitted for further examination due to suspected abnormal ICP or associated symptoms; (4) previous ocular or cranial trauma, surgery, laser treatment, or puncture; (5) took oral medications affecting IOP or ICP within 6 months (mannitol, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, beta-blockers, glucocorticoids, high-dose vitamin A, and tetracycline); (6) use of IOP-lowering eye drops or glucocorticoid eye drops within 1 month; and (7) seizures for any reason within 24 h. Finally, for quasi-healthy individuals with diseases that do not affect IOP or ICP but cause structural or functional abnormalities of the globe or optic nerve, the involved eye was excluded, while the healthy eye was included. Table 1 lists the types of diseases included and excluded from this study.

Table 1.

Included and excluded diseases.

| Included diseases | Excluded diseases |

|---|---|

| Idiopathic epilepsy | Glaucoma |

| Unilateral optic neuritis | Pterygium (severe, over 3 mm) |

| Unilateral optic nerve dysplasia | Uveitis |

| Unilateral ischemic optic neuropathy | Choroidal/retinal detachment |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Intraocular haemorrhage |

| Mental disorder | Bilateral optic neuritis |

| Orbital vasculitis | |

| Nonspecific orbital inflammation | |

| Secondary intracranial hypertension | |

| Space-occupying lesions of the spine/brain | |

| Intracranial infections | |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | |

| Cerebral ischemia and infarction | |

| Status epilepticus | |

| Metabolic encephalopathy |

TLCPD measurements

TLCPD was measured between 01:00 and 03:00 PM. IOP was measured at the bedside with the patient in a sitting position using an iCare rebound tonometer (Tiolat, Oy, Helsinki, Finland). After IOP measurement, the patient was placed in the left lateral position for lumbar puncture to measure ICP. IOP measurements were performed by two trained investigators (YJ and DTL), and the measurement was repeated at least six times per eye. The IOP data were averaged after excluding the highest and lowest values. Only quality measurements (indicated by zero to one bar on the device) were accepted. IOP readings were rounded to the closest whole number and reported in mmHg. ICP was measured in the standard way using the left lateral decubitus posture under local anaesthetic with the patient’s neck bent in full flexion and legs bent in full flexion up to the chest. A 20-gauge spinal needle with a length of 90 mm was placed between the lumbar vertebrae L3/L4 or L4/L5 and pushed in until resistance decreased, indicating that the needle had passed through the dura mater. After removing the stylet from the spinal needle and connecting a manometer to the needle, the cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure was measured. The ICP readings were rounded to the closest whole number and reported in mmH2O. TLCPD was calculated according to the following formula: TLCPD (mmHg) = IOP (mmHg) – ICP (mmHg).

Assessment of systemic biometric factors

Two trained physicians (YJ and XMD) assessed systemic biometric factors (basic information, medical history, physical measurements, and circulatory parameters) within 1 h prior to TLCPD measurement. The physical measurements included height, weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and hip circumference. Circulatory parameters included systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, and pulse. Brachial blood pressure and pulse were measured with the subject at rest and in a sitting position using an automatic sphygmomanometer (Omron HEM 705 LP, Omron Healthcare, Inc.) following the standard protocol [22]. Mean arterial pressure was calculated as follows: (systolic blood pressure / 3) + [(2 × diastolic blood pressure) / 3].

Screening ophthalmic examination

Within one week after TLCPD measurement, two specialized ophthalmologists (DTL and RQP) conducted a preliminary ocular disease screening for all participants. This screening involved slit-lamp examination, fundus examination, evaluation of uncorrected and best-corrected visual acuity, and the collection of ocular medical history and ocular family history. For patients with suspicious ocular disease, an experienced ophthalmologist (NLW) made the diagnosis.

Statistical analyses

The analyses of IOP and TLCPD reference values considered all the included eyes, whereas only one eye per person was considered in the correlation analysis. For patients with two included eyes, only the right eye was included in the correlation analysis. The raw data were assessed for normality by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For basic statistical description, the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation and 95% reference intervals (defined as the 2.5th–97.5th percentiles). Categorical data were expressed as frequency and percentage. Differences between groups were assessed by independent-sample T-test and Mann–Whitney U test for normally and non-normally distributed data, respectively. Differences in continuous variables between multiple groups were compared by ANOVA (for normally distributed data) or the Kruskal–Wallis test (for non-normally distributed data). Before we perform T-test or ANOVA, the homogeneity test of variance was done. For continuous covariates, correlations were evaluated using either the Pearson or Spearman correlation depending on the variable’s data distribution. For TLCPD, IOP, and ICP, a linear mixed-effects analysis was further conducted if more than two systematic biometric factors were found to be significant in the correlation analysis. Significance tests were two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using Predictive Analytics Software Statistics version 23 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

From September 2019 to March 2022, a total of 4915 patients were treated in the neurology departments of the two hospitals. In total, 526 patients with 776 eyes (341 right eyes and 435 left eyes) were included in the study. The participants were all Asian and included 251 males (47.7%) and 275 females (52.3%), aged 18–76 years (mean age = 45.3 ± 15.3 years). The demographic data of the subjects are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

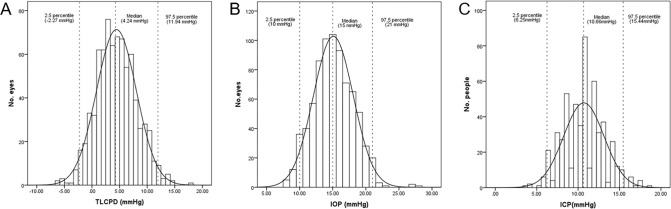

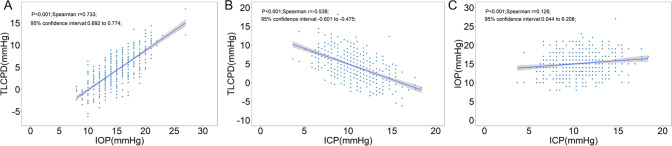

The distributions of TLCPD and IOP for the 776 included eyes and the ICP values of the 526 subjects are shown in Fig. 1. The TLCPD values were normally distributed with a mean value of 4.4 ± 3.6 mmHg, and no difference was found between male (4.3 ± 3.3 mmHg) and female (4.6 ± 3.9 mmHg) participants. The 95% reference interval of TLCPD was −2.27 to 11.94 mmHg, with 10.6% (n = 82) of the TLCPD values being below 0. The mean IOP was 15.1 ± 3.0 mmHg, with a 95% reference interval of 10.00–21.00 mmHg. IOP was significantly higher in males (15.4 ± 2.8 mmHg) than in females (14.8 ± 3.2 mmHg; p = 0.002). The mean ICP was 10.7 ± 2.4 mmHg with a 95% reference interval of 6.25–15.44 mmHg. ICP was significantly higher in males (11.1 ± 2.3 mmHg) than in females (10.3 ± 2.5 mmHg; p < 0.001). TLCPD was significantly correlated with IOP (r = 0.733, p < 0.001) and ICP (r = −0.538, p < 0.001), and IOP was correlated with ICP (r = 0.126, p < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Histograms of trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference, intraocular pressure, and intracranial pressure.

Histograms showing the distribution of trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference (A), intraocular pressure (B), and intracranial pressure (C) in quasi-healthy individuals.

Fig. 2. Scatterplots of trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference, intraocular pressure, and intracranial pressure.

Scatterplots showing the association between trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference (TLCPD), intraocular pressure (IOP), and intracranial pressure (ICP) in 526 subjects: the associations between (A) TLCPD and IOP; (B) TLCPD and ICP; and (C) IOP and ICP.

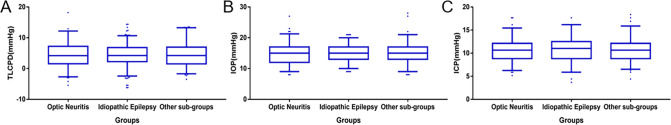

Among the included subjects, 185 patients were diagnosed with optic neuritis, and 194 patients were diagnosed with idiopathic epilepsy; the remaining 147 patients were placed into the ‘other’ group. The median TLCPD and 95% reference intervals of the three groups overlapped considerably and were not significantly different (4.18 [−2.69 to 12.18] vs. 4.24 [−2.44 to 10.68] vs. 4.24 [−1.70 to 13.27]; p = 0.884). The median IOP and 95% reference intervals in the three groups overlapped considerably and were not significantly different (15 [9–21] vs. 15 [10–20] vs. 15 [9–21]; p = 0.947). The median ICP and 95% reference intervals in the three groups overlapped considerably and were not significantly different (10.66 [6.25–15.44] vs. 11.03 [5.88–16.18] vs. 10.66 [6.51–15.88]; p = 0.829); Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Box plots of trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference, intraocular pressure, and intracranial pressure.

Box plots showing the distribution of A trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference (TLCPD), B intraocular pressure (IOP), and C intracranial pressure (ICP) in three groups with different disease diagnoses. The average pressure was not statistically significant difference among the three groups.

Spearman correlation analysis revealed that TLCPD was significantly negatively correlated with BMI (r = −0.086, p = 0.049). IOP was significantly correlated with gender (r = −0.087, p = 0.047), weight (r = 0.169, p < 0.001), BMI (r = 0.136, p = 0.002), waist circumference (r = 0.150, p = 0.012), hip circumference (r = 0.191, p = 0.002), systolic blood pressure (r = 0.194, p < 0.001), diastolic blood pressure (r = 0.110, p = 0.016), and mean arterial pressure (r = 0.168, p < 0.001). ICP was significantly correlated with gender (r = −0.173, p < 0.001), height (r = 0.113, p = 0.013), weight (r = 0.286, p < 0.001), BMI (r = 0.278, p < 0.001), waist circumference (r = 0.120, p = 0.044), systolic blood pressure (r = 0.181, p < 0.001), diastolic blood pressure (r = 0.200, p < 0.001), and mean arterial pressure (r = 0.254, p < 0.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients between systemic biometric factors and TLCPD, IOP, and ICP.

| TLCPD | ICP | IOP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | r | p | r | p | r | p |

| Age | 0.025 | 0.565 | –0.071 | 0.103 | –0.025 | 0.571 |

| Gender | 0.049 | 0.264 | –0.173 | <0.001* | –0.087 | 0.047* |

| Height | –0.013 | 0.774 | 0.113 | 0.013* | 0.076 | 0.098 |

| Weight | –0.056 | 0.218 | 0.286 | <0.001* | 0.169 | <0.001* |

| Body mass index | –0.086 | 0.049* | 0.278 | <0.001* | 0.136 | 0.002* |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.029 | 0.530 | 0.181 | <0.001* | 0.194 | <0.001* |

| Diastolic blood pressure | –0.058 | 0.203 | 0.200 | <0.001* | 0.110 | 0.016* |

| Mean arterial pressure | –0.045 | 0.300 | 0.254 | <0.001* | 0.168 | <0.001* |

| Pulse rate | –0.020 | 0.739 | 0.041 | 0.492 | 0.008 | 0.896 |

| Waist circumference | 0.014 | 0.812 | 0.120 | 0.044* | 0.150 | 0.012* |

| Hip circumference | 0.072 | 0.24 | 0.085 | 0.164 | 0.191 | 0.002* |

TLCPD trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference, ICP intracranial pressure, IOP intraocular pressure.

*Statistically significant p values (p < 0.05).

Linear mixed-effects analysis revealed that ICP was associated with gender (β = 0.69, p = 0.032), BMI (β = 0.20, p = 0.001), and mean arterial pressure (β = 0.03, p = 0.031; Supplementary Table 2). IOP was associated with BMI (β = 0.17, p = 0.025) and mean arterial pressure (β = 0.06, p < 0.001; Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

This study provides clinically applicable reference intervals for normal TLCPD. Although the subjects were not healthy individuals, we excluded diseases that could have influenced the results and the reference intervals obtained were theoretically consistent with a healthy population. We verified the following: (1) the quasi-healthy subjects in this study were categorised into patients with unilateral optic neuritis, idiopathic epilepsy, and other diseases, and the TLCPD, IOP, and ICP values of these subjects did not differ significantly among these three groups; and (2) the reference intervals for IOP and ICP were similar to those reported in a healthy population [13, 16, 23, 24].

The mean value of TLCPD obtained in this study was 4.4 mmHg. Thus, in most patients, IOP was higher than ICP, consistent with previous findings. The 95% TLCPD reference interval obtained in this study (−2.27 to 11.94 mmHg) is broader than the predicted reference interval (3–8 mmHg) based on known reference intervals of IOP (10–21 mmHg) and ICP (7–13 mmHg). However, the predicted interval is obtained by simple calculation and does not reflect the actual population. Interestingly, in our study, ICP was higher than IOP in 10.6% of subjects without pressure-related optic nerve head disorders. This does not support the hypothesis that papilledema occurs when IOP is lower than ICP.

IIH is the most common cause of papilledema. Elevated ICP leads to increased ONSP, resulting in impaired axoplasmic flow and the swelling of axonal nerve fibres [3]. However, the relationship between elevated ICP and papilledema is not absolute; some patients with IIH do not have papilledema, and 10% of patients with IIH show asymmetric optic papilledema [11]. This implies that factors other than ICP play a role in the disease progression of IIH patients presenting with papilledema. Notably, low IOP can also cause papilledema [12], suggesting that TLCPD may be a better metric than ICP for the diagnosis of papilledema. Additional studies should investigate whether people with TLCPD below −2.27 mmHg are more likely to develop papilledema than those with TLCPD in the normal range. In addition, the role of the imbalance between IOP and ICP in the development of papilledema requires further exploration.

Those with TLCPD above 11.94 mmHg should be alerted to the risk of glaucoma. IOP greater than 21 mmHg has long been considered a major risk factor for glaucoma [17, 25, 26]. However, NTG, a subtype of open-angle glaucoma associated with normal IOP, cannot be diagnosed based on IOP measurement. In Asian countries such as China and Japan, NTG accounts for 70–92% of open-angle glaucoma [27, 28]. ICP has been suggested to play a role in open-angle glaucoma and particularly NTG. Abnormally high TLCPD is responsible for the pathogenesis in NTG [17, 29]. Berdahl et al. reviewed a large number of patients who had undergone lumbar puncture and found low ICP values in primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) patients [8]. Berdahl et al. also found that TLCPD was higher in patients with NTG and high-pressure POAG compared to matched non-glaucomatous subjects [7]. Ren et al. prospectively confirmed that NTG patients have lower ICP and higher TLCPD compared with high-pressure POAG and non-glaucomatous subjects [4]. Unfortunately, due to the lack of a reference interval for TLCPD, these studies were based on the comparison of means between groups, preventing them from (1) identifying individuals with abnormally elevated TLCPD and (2) defining abnormal values for ICP in patients with glaucoma.

Our study addresses the above issue by providing an upper limit of the reference interval for TLCPD (11.94 mmHg). Based on our results, we suggest that Asian ocular hypertension (OHT) patients with IOP >27 mmHg after correction for other influencing factors (e.g., central corneal thickness) should be followed closely and treated aggressively. For most people with normal ICP (<15.44 mmHg), an IOP of 27 mmHg means that TLCPD is in the abnormal range. Similarly, if a patient with NTG (IOP <21 mmHg) has a predicted ICP of less than 9 mmHg based on non-invasive ICP measurements, the disease is likely due to abnormal TLCPD, and an aggressive reduction of IOP is indicated. In addition, the TLCPD reference interval provided by this study may explain the discrepancy in past findings regarding the association of NTG with low ICP [5, 10]. We propose that NTG due to abnormal TLCPD is only one NTG subtype; based on previous studies, this NTG subtype is more common in Asian populations and less common in Caucasian populations [4, 10, 30, 31]. NTG is a complex syndrome with a variety of pathological pathways in different subtypes [32]. The TLCPD reference interval reported herein can be used to further differentiate NTG subtypes.

TLCPD is calculated by subtracting ICP from IOP; thus, TLCPD is obviously positively associated with IOP and negatively associated with ICP. Notably, IOP and ICP are also correlated, and IOP has been suggested as a predictive metric for ICP [2]. The correlation between IOP and ICP is pronounced in intracranial hypertension, mainly due to the return of blood to optic veins through the superior orbital fissure to the intracranial cavernous sinus; higher ICP causes elevated intraocular venous pressure, resulting in higher IOP [33]. Hou et al. demonstrated that ICP and IOP are positively correlated only within specific pressure intervals in dogs [34]. In this study, we used a handheld tonometer to measure IOP and ICP simultaneously and found a positive but weak association between IOP and ICP. Using IOP to predict ICP is not feasible in populations with normal ICP. In contrast, the difference between IOP and ICP is more valuable in clinical applications.

Berdahl et al. and Ren et al. found that ICP and TLCPD are higher in patients with OHT compared with the controls [7, 35]. They suggested that the elevated ICP in OHT might counterbalance the elevated IOP and prevent or slow glaucomatous optic nerve damage. However, this explanation cannot account for the higher TLCPD in OHT patients compared with the control group [7, 35]. Based on the findings of the present study, we suggest that ICP and TLCPD are positively correlated with IOP in populations without glaucoma; therefore, the higher ICP and TLCPD values in OHT patients with respect to normal subjects are physiological and may not be related to the unique pathophysiological changes in OHT. Additional follow-up with OHT patients with TLCPD >11.94 mmHg would be valuable to confirm the role of TLCPD in the diagnosis and treatment of OHT by determining if these patients are more likely to develop glaucoma in the following years.

TLCPD was associated with BMI in this study. BMI has been reported to be positively associated with both IOP and ICP due to the excess adipose tissue and higher abdominal pressure in individuals with high BMI [13–15, 36]. Excess adipose tissue causes elevated orbital pressure, resulting in higher episcleral venous pressure [13]. Increased abdominal pressure can alter the venous pressure to affect ICP [15]. In the present study, multivariable analysis showed that BMI was an independent factor in both IOP and ICP, and we confirmed the significant negative association between BMI and TLCPD. The theory that IOP is a single risk factor cannot explain why high BMI accompanied by high IOP reduces the risk of open-angle glaucoma [13, 14, 37]. Alternatively, we propose that although higher BMI is associated with higher IOP, it also corresponds to higher ICP and lower TLCPD, which protects against glaucoma. In contrast, in patients with IIH, obese patients are more likely to have negative TLCPD, which is a risk factor for the development of papilledema. In addition, age, gender, circulatory parameters, and physical parameters other than BMI were not associated with TLCPD in this study.

This study has some limitations. First, since lumbar puncture is invasive and poses a risk of infection, recruiting large numbers of healthy subjects is difficult and ethically controversial. Thus, we enrolled quasi-healthy subjects in this study and excluded subjects with known diseases, medications, surgeries, and other factors affecting IOP or ICP. However, unknown factors affecting the results may have been present. Second, this study determined a reference interval for TLCPD to provide a straightforward and universal indicator for ophthalmic and neurological applications. However, in clinical applications of TLCPD, other ophthalmic parameters should be considered (e.g., central corneal thickness, lamina cribrosa thickness, and ocular axis).

In summary, we determined a 95% reference interval of −2.27 to 11.94 mmHg for TLCPD. This interval can be used to determine NTG risk factors, identify the aetiology of papilledema, and inform the study, diagnosis, and treatment of various optic nerve head diseases. Although several circulatory and physical parameters affect both IOP and ICP, only BMI affects TLCPD (TLCPD is negatively associated with BMI). As non-invasive methods to measure ICP improve and the pathogenesis of pressure-related ophthalmic and neurological diseases are further elucidated, the TLCPD reference intervals is expected to become the primary basis for the diagnosis and treatment of optic nerve head diseases.

Summary

What was known before

Trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference abnormalities have been one of the hottest topics in the field of open-angle glaucoma.

Trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference has been associated with the pathogenesis and management of a variety of neurological and ophthalmic diseases.

What this study adds

We remedy the lack of a trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference reference interval.

The reference interval is applied to multiple ophthalmic and neurological diseases.

The higher the BMI, the lower the trans-laminar cribrosa pressure difference.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank AiMi Academic Services (www.aimieditor.com) for the English language editing and review services.

Author contributions

NLW and JWW contributed to the design, acquisition of funding and general supervision of the research group. RQP and DTL contributed to the design, acquired data, analysis of results and drafting of the manuscript. XMD, XYL, LHG, JC, YJ and YPW contributed to the acquired data and advised on the research. KC, TMR and YC contributed to the data analysis.

Funding

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82130029). The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ruiqi Pang, Danting Lin.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Jiawei Wang, Ningli Wang.

Contributor Information

Jiawei Wang, Email: wangjwcq@163.com.

Ningli Wang, Email: wningli@vip.163.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41433-022-02323-9.

References

- 1.Berdahl JP, Yu DY, Morgan WH. The translaminar pressure gradient in sustained zero gravity, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and glaucoma. Med Hypotheses. 2012;79:719–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yavin D, Luu J, James MT, Roberts DJ, Sutherland GR, Jette N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of intraocular pressure measurement for the detection of raised intracranial pressure: meta-analysis: a systematic review. J Neurosurg. 2014;121:680–7. doi: 10.3171/2014.4.JNS13932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu KC, Fleischman D, Lee AG, Killer HE, Chen JJ, Bhatti MT. Current concepts of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and the translaminar cribrosa pressure gradient: a paradigm of optic disk disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2020;65:48–66. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ren R, Jonas JB, Tian G, Zhen Y, Ma K, Li S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in glaucoma: a prospective study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindén C, Qvarlander S, Jóhannesson G, Johansson E, Östlund F, Malm J, et al. Normal-tension glaucoma has normal intracranial pressure: a prospective study of intracranial pressure and intraocular pressure in different body positions. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berdahl JP, Ferguson TJ, Samuelson TW. Periodic normalization of the translaminar pressure gradient prevents glaucomatous damage. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:110258. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berdahl JP, Fautsch MP, Stinnett SS, Allingham RR. Intracranial pressure in primary open angle glaucoma, normal tension glaucoma, and ocular hypertension: a case-control study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5412–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berdahl JP, Allingham RR, Johnson DH. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure is decreased in primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:763–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JWY, Chan PP, Zhang X, Chen LJ, Jonas JB. Latest developments in normal-pressure glaucoma: diagnosis, epidemiology, genetics, etiology, causes and mechanisms to management. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Philos) 2019;8:457–68. doi: 10.1097/01.APO.0000605096.48529.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pircher A, Remonda L, Weinreb RN, Killer HE. Translaminar pressure in Caucasian normal tension glaucoma patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95:e524–31. doi: 10.1111/aos.13302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wall M, White WN., II Asymmetric papilledema in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: prospective interocular comparison of sensory visual function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:134–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radke PM, Rubinstein TJ, Hamilton SR, Jamil AL, Sires BS. The translaminar pressure gradient: papilledema after trabeculectomy treated with optic nerve sheath fenestration. J Glaucoma. 2018;27:e154–7. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoehn R, Mirshahi A, Hoffmann EM, Kottler UB, Wild PS, Laubert-Reh D, et al. Distribution of intraocular pressure and its association with ocular features and cardiovascular risk factors: the Gutenberg Health Study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:961–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomoyose E, Higa A, Sakai H, Sawaguchi S, Iwase A, Tomidokoro A, et al. Intraocular pressure and related systemic and ocular biometric factors in a population-based study in Japan: the Kumejima study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischman D, Berdahl JP, Zaydlarova J, Stinnett S, Fautsch MP, Allingham RR. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure decreases with older age. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malm J, Jacobsson J, Birgander R, Eklund A. Reference values for CSF outflow resistance and intracranial pressure in healthy elderly. Neurology. 2011;76:903–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820f2dd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price DA, Harris A, Siesky B, Mathew S. The influence of translaminar pressure gradient and intracranial pressure in glaucoma: a review. J Glaucoma. 2020;29:141–6. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan WH, Yu DY, Alder VA, Cringle SJ, Cooper RL, House PH, et al. The correlation between cerebrospinal fluid pressure and retrolaminar tissue pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1419–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balaratnasingam C, Morgan WH, Johnstone V, Pandav SS, Cringle SJ, Yu DY. Histomorphometric measurements in human and dog optic nerve and an estimation of optic nerve pressure gradients in human. Exp Eye Res. 2009;89:618–28. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonas JB, Wang N, Wang YX, You QS, Xie X, Yang D, et al. Body height, estimated cerebrospinal fluid pressure and open-angle glaucoma. The Beijing Eye Study 2011. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonas JB, Nangia V, Wang N, Bhate K, Nangia P, Nangia P, et al. Trans-lamina cribrosa pressure difference and open-angle glaucoma. The central India eye and medical study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–81. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SC, Lueck CJ. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in adults. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34:278–83. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norager NH, Olsen MH, Pedersen SH, Riedel CS, Czosnyka M, Juhler M. Reference values for intracranial pressure and lumbar cerebrospinal fluid pressure: a systematic review. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2021;18:19. doi: 10.1186/s12987-021-00253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vishwaraj CR, Kavitha S, Venkatesh R, Shukla AG, Chandran P, Tripathi S. Neuroprotection in glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:380–5. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1158_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downs JC. Neural coupling of intracranial pressure and aqueous humour outflow facility: a potential new therapeutic target for intraocular pressure management. J Physiol. 2020;598:1429–30. doi: 10.1113/JP279355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao J, Solano MM, Oldenburg CE, Liu T, Wang Y, Wang N, et al. Prevalence of normal-tension glaucoma in the chinese population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;199:101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwase A, Suzuki Y, Araie M, Yamamoto T, Abe H, Shirato S, et al. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in Japanese: the Tajimi Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1641–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jonas JB, Wang N, Yang D, Ritch R, Panda-Jonas S. Facts and myths of cerebrospinal fluid pressure for the physiology of the eye. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015;46:67–83. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Yang D, Ma T, Shi W, Zhu Q, Kang J, et al. Measurement and associations of the optic nerve subarachnoid space in normal tension and primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;186:128–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang N, Xie X, Yang D, Xian J, Li Y, Ren R, et al. Orbital cerebrospinal fluid space in glaucoma: the Beijing intracranial and intraocular pressure (iCOP) study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2065–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Killer HE, Pircher A. Normal tension glaucoma: review of current understanding and mechanisms of the pathogenesis. Eye (Lond) 2018;32:924–30. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0042-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Yang Y, Lu Y, Liu D, Xu E, Jia J, et al. Intraocular pressure vs intracranial pressure in disease conditions: a prospective cohort study (Beijing iCOP study) BMC Neurol. 2012;12:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hou R, Zhang Z, Yang D, Wang H, Chen W, Li Z, et al. Pressure balance and imbalance in the optic nerve chamber: The Beijing Intracranial and Intraocular Pressure (iCOP) Study. Sci China Life Sci. 2016;59:495–503. doi: 10.1007/s11427-016-5022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ren R, Zhang X, Wang N, Li B, Tian G, Jonas JB. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in ocular hypertension. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:e142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wakerley BR, Warner R, Cole M, Stone K, Foy C, Sittampalam M. Cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure: the effect of body mass index and body composition. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;188:105597. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pasquale LR, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Kang JH. Anthropometric measures and their relation to incident primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1521–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.