Abstract

Purpose

To investigate small nerve fibre damage and inflammation at the level of the sub-basal nerve plexus (SNP) of severe obese patients and compare the results with those of healthy subjects.

Methods

This cross-sectional, observational study investigated the data of 28 patients (14 out of 28 prediabetic or diabetic) with severe obesity (Body Mass Index; BMI ≥ 40) and 20 healthy subjects. Corneal nerve fibre density (CNFD), branch density (CNBD), fibre length (CNFL), nerve fibre area (CNFA), nerve fibre width (CNFW), and nerve fractal dimension (CNFrD) and dendritic cell (DC) density were evaluated using in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM, Heidelberg Retinal Tomograph III Rostock Cornea Module). Automatic CCMetrics software (University of Manchester, UK) was used for quantitative analysis of SNP.

Results

Mean age was 48.4±7.4 and 45.1 ± 5.8 in the control and obese group, respectively (p = 0.09). Mean BMI were 49.1 ± 7.8 vs. 23.3 ± 1.4 in obese vs. control group, respectively (p < 0.001). Mean CNFD, CNBD, CNFL, CNFA, CNFW were significantly reduced in obese group compared with those in the control group (always p < 0.05, respectively). There were no significant differences in any ACCMetrics parameters between prediabetic/diabetic and non-diabetic obese patients. Increased DC densities were detected in obese group compared with those in control group (p < 0.0001). There were significant correlations between BMI scores and SNP parameters.

Conclusion

Imaging with IVCM is a feasible, non-invasive method to detect and quantify occult corneal nerve damage and increased inflammation in patients with obesity. This study suggests that obesity may be a separate risk factor for peripheral neuropathy regardless of DM.

Subject terms: Corneal diseases, Obesity

Introduction

Obesity is increasingly recognized as a serious, worldwide public health concern over the last decade [1, 2]. It is well-known that obesity may precede numerous systemic diseases including type-2 diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary heart diseases, hypertension, and dyslipidemia [3–5]. It has also been reported that obesity may be associated with various type of ocular diseases, such as cataract and increased intraocular pressure [6]. Of relevance, obesity can lead to inflammatory changes and processes in many tissues in a considerable amount of obese individuals [7–9]. One of the possible obesity-related pathologies is peripheral neuropathy, which can involve many nerves throughout the body, even corneal nerves [10, 11].

Regarding recent developments in diagnostic devices, investigators have tried to probe various markers in prediction and early detection of peripheral neuropathy by using promising diagnostic techniques. A notable example of these diagnostic tools is in vivo corneal confocal microscopy (IVCM), which detects early nerve damage by making corneal sub-epithelial neural fibres visible [12–14]. Furthermore, IVCM allows quantitative and qualitative (morphological) analysis of corneal nerve fibres. Recent evidence suggests that IVCM is a useful non-invasive tool to measure and analyze the small nerve fibres in diabetic corneas [15–17]. In light of this, questions have been raised about the availability of IVCM as a predictive marker to assess neural damage and inflammation earlier in patients with prediabetic metabolic syndrome and diet-induced obesity. So far, much uncertainty still exists about the corneal neural changes, particularly regarding inflammation in diet-induced obese patients. The research to date has only been carried out in several preclinical and clinical studies to evaluate sub-basal nerve plexus (SNP) [18–21].

This study aims to determine the utility of IVCM in the assessment of corneal small nerve fibre damage and inflammation in patients with severe obesity.

Materials and Methods

Study design and patient recruitment

This was a cross-sectional observational study of participants recruited from the outpatient clinic of cornea and external eye diseases in Marmara University Hospital. The participants were divided into two main age-matched groups based on their body mass index (BMI) as follows: diet-induced morbidly obese group having at least a BMI of 40 (Group 1) and control group having a BMI of 25 or less (Group 2). Subsequently, group 1 was classified into two subgroups according to coexisting DM. Eligibility criteria for group 1 required individuals to have no diagnosis of any neurologic or cardiovascular diseases related to neuropathy except DM. Group 2 consisted of healthy individuals without any history of neuropathic, endocrine, or cardiovascular disease. Patients with a history of ocular trauma, surgery or disease were also excluded from the study in each study group. The research adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki tenets and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Marmara University, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Clinical and laboratory assessment

Age, history of DM, BMI, haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level, and total lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL-HDL cholesterol levels) of each participant were recorded prior to participation. Medical reports of all participants were reviewed to collect HbA1c within the last three months. A level under 5.7% was accepted as ‘normal’, between 5.7% to 6.4% as ‘prediabetic’, and 6.5% or greater as ‘diabetic’ conforming to the American Diabetes Association consensus statement [22]. In cases with unavailable record of HbA1c level, the records of fasting blood glucose level (FBG, mg/dL) within the last three months were used in categorization of the relevant participants. The participants with a BMI of 40 or greater were classified as ‘severely obese’, a BMI between 25 to 30 as ‘overweight’, and a BMI from 18.5 to 25 as ‘normal’ in accordance with the WHO’s standard guidelines [23]. All participants underwent a detailed slit-lamp biomicroscopic examination followed by a routine fundus examination before IVCM testing.

Corneal confocal microscopy

All IVCM measurements were obtained from the right eyes of the subjects. Sub-basal nerve plexus (SNP) assessment of the cornea was carried out by IVCM (Heidelberg Retina Tomograph III Rostock Cornea Module, Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) as per previously described [24]. Three high quality non-overlapping corneal images were chosen from each subjects’ right eye based upon a recently defined standardized image selection protocol [25]. The same investigator acquired all the images for each participant in a masked fashion. For the image analysis, seven corneal nerve parameters were quantified as follows: corneal nerve fibre density (CNFD), the total number of major nerves per square millimetre of corneal tissue; corneal nerve branch density (CNBD), the number of branches originating from the major nerve trunks per square millimetre; corneal nerve fibre length (CNFL), the total length of all nerve fibres and branches millimetre per square millimetre within the area of corneal tissue; corneal nerve total branch density (CTBD), the total number of branch points per frame; corneal nerve fibre area (CNFA), the total nerve fibre area per frame; corneal nerve fibre width (CNFW), the average nerve fibre width per frame; corneal nerve fractal dimension (CNFrD), a measure of the structural complexity of corneal nerves. All image analysis was performed using automated software called Automatic CCmetrics (The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK).

Corneal dendritic cell analysis

The DCs were assessed in the same image frames used for SNP analysis. DCs were determined as the cells having a bright, dendriform appearance at the level of SNP. DC density (cells/mm2) was quantified manually using the cell counter plugin of ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; provided in the public domain by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The potential inter-observer variability was excluded by performing with the same well- experienced masked observer for all DC analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data statistics were determined using SPSS for Mac (Version 19.0, IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Normally distributed data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) and non-normal distributed data were expressed as median with interquartile ranges (IQRs; 25–75% percentiles) as noted. Tests for normality were done using Shapiro-Wilk test and by visualizing the histogram and normal Q-Q plot. Normally distributed variables were analysed using a two-tailed sample independent t-test, and Mann Whitney-U test was used for comparing non-parametric variables. Correlations were analysed by Pearson’s correlation test in the normally distributed parameters and by Spearman’s correlation test in the non-normal distributed parameters. The estimated sample size to assess IVCM parameter changes was calculated as 25 patients with an alpha level of 0.05 and the statistical power of 80% [26]. All statistical testing were done using an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 28 patients with obesity (group 1) and 20 age-matched control subjects (group 2) were enrolled in this study. The mean age was 48.4 ± 7.4 in group 2 and 45.1 ± 5.8 in group 1 (p = 0.09). Subjects with obesity had significantly higher BMI compared to the control subjects (group 1 vs. group 2; 49.1 ± 7.8 vs. 23.3 ± 1.4, respectively, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in the mean levels of total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL and LDL cholesterol between group 1 and group 2. Data for HbA1c were available for 39 out of 48 participants and no significant difference in the median of HbA1c was found between group 1 and group 2 (p = 0.25). The remained all nine (1 case with obesity and 8 control cases) subjects, who had unavailable HbA1c records, had normal FBG levels within the last 3 months thereby considered as non-diabetic (the mean FBG was 83.7 mg/dL). Fourteen out of 28 subjects in Group 1 were prediabetic/diabetic (prediabetic/diabetic subgroup the median HbA1c; 6.4, IQR: 5.97–7.85 vs. non-prediabetic/non-diabetic subgroup the median HbA1c; 5.3, IQR: 5.2–5.4, p = 0.02). The detailed clinical characteristic features of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical, Body Mass Index (BMI) and metabolic characteristics of patients with obesity compared to age-matched controls.

| Obese Group | Control Group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 28 (52) | 20 (48) | – |

| Type 2 diabetes, n | 14 | 0 | – |

| Age, y | 45.1 ± 5.8 | 48.4 ± 7.4 | 0.09 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 49.1 ± 7.8 | 23.3 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| HbA1c, mmol/mol,% (25–75% percentiles) | 5.7 (5.4-6.6) | 5.3 (4.9-5.4) | 0.25 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 222 ± 44 | 221 ± 48.1 | 0.89 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 143 ± 75.5 | 142 ± 62.9 | 0.68 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 140 ± 37.3 | 138 ± 37.5 | 0.84 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 54.5 ± 12.8 | 53.5 ± 12.4 | 0.76 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD for parametric variables and median (25–75% percentiles) for non-parametric variables

Corneal confocal microscopy assessments

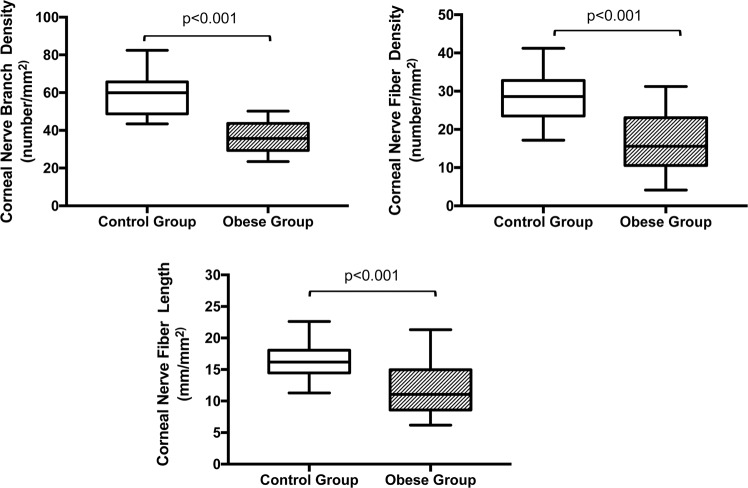

The mean CNFD was significantly reduced in the subjects with obesity compared to that in group 2 (group 1 vs. group 2; 16.4 ± 7.7 no./mm2 vs. 28.0 ± 6.5 no./mm2, respectively, p < 0.001). Likewise, the subjects with obesity had a significantly reduced mean of CNFL and CNBD compared to the control group (CNFL; group 1 vs. group 2; 11.9 ± 4.1 mm/mm2vs.16.5 ± 2.9 mm/mm2, CNBD; group 1 vs. group 2; 38.1 ± 13.5 no./mm2 vs. 58.3 ± 11.3 no./mm2 respectively, p < 0.001 for both CNFL and CNBD) (Fig. 1.). Similarly, there were clinically relevant difference between the subjects with obesity and the control group regarding the mean CTBD, CNFA, CNFW and CNFrD (CTBD; group 1 vs. group 2; 41.56 ± 30.33 no./mm2vs. 57.68 ± 27.25 no./mm2, p = 0.02, CNFA; group 1 vs. group 2; 0.005 ± 0.002 mm2/mm2 vs. 0.007 ± 0.001 mm2/mm2, p = 0.046, CNFW; group 1 vs. group 2; 0.022 ± 0.001 mm/mm2 vs. 0.020 ± 0.001 mm/mm2, p = 0.01, CNFrD; group 1 vs. group 2; 1.44 ± 0.05 vs. 1.49 ± 0.02, p = 0.002). Fourteen subjects (50%) in group 1 had DM without retinopathy. In subgroup analysis, no statistically significant difference was found in any of the SNP parameters between obese subjects with and without coexisting DM (Table 2). In addition, there was no significant difference between the subjects with prediabetes and those with DM regarding any of the SNP parameters.

Fig. 1. Comparisons of corneal nerve fibre morphological parameters between subjects with obesity (group 1) and age-matched healthy control subjects (group 2).

Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Table 2.

In vivo corneal confocal assessment of patients with obesity (with/without diabetes) compared to age-matched controls.

| Obese Group (pre-diabetic/diabetic) | Obese Group (non-prediabetic/non-diabetic) | Control Group | p* | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 14 | 14 | 20 | – | |

| HbA1c %,mmol/mol, (25%-75% percentiles) | 6.4 (5.97-7.85) | 5.3 (5.2-5.4) | 5.3 (4.9-5.4) | 0.02 | 0.25 |

| CNFD, no./mm2 | 15.9 ± 7.4 | 16.9 ± 8.3 | 28.0 ± 6.5 | 0.73 | <0.001 |

| CNFL, mm/mm2 | 12.0 ± 4.5 | 11.9 ± 4.0 | 16.5 ± 2.9 | 0.95 | <0.001 |

| CNBD, no./mm2 | 39.3 ± 17.6 | 36.8 ± 8.1 | 58.3 ± 11.3 | 0.63 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD for parametric variables and median (25–75% percentiles) for non-parametric variables.

*p-value for comparison of obese subgroups regarding pre-diabetic/diabetic vs. non-prediabetic/non-diabetic

p-value for comparison of obese group (as group 1) with age-matched control group

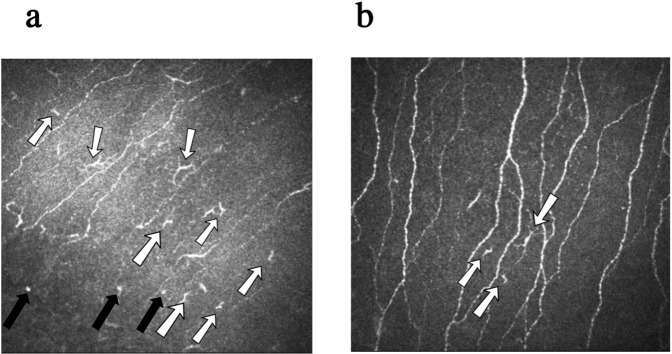

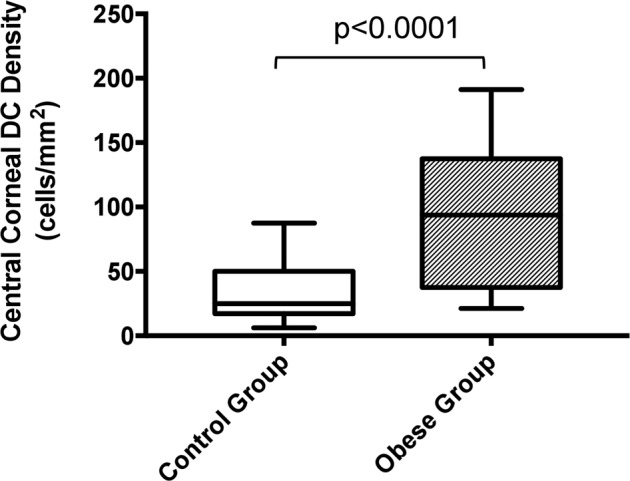

At the layer of SNP, the median density of DCs in the control group was calculated as 25 cells/mm2, IQR: 18.8-48.4, whilst a median number of 93.8, IQR: 40.6-134 was detected in the obese group. There was a statistically significant difference in the median density of DCs between the two groups (p < 0.0001, 95% CI; −84.8, −31.4) (Fig. 2.). Further subgroup analysis in severe obese group revealed that the median density of DCs of the subjects with DM was significantly higher than that of the subjects without DM (Median, IQR: 125, 93.8–150 vs. 62.5, 37.5–100, p = 0.02, obese subjects with DM vs. obese subjects without DM, respectively). Remarkably, the median density of DCs of the obese subjects without DM was also significantly higher than that of control group (Median, IQR: 62.5, 37.5–100 vs. 25, 18.8–48.4, p = 0.003, obese subjects without DM vs. control subjects, respectively). The IVCM images of the representative cases in each group are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2. Comparing of the median dendritic cell densities of the severe obese group (group 1) and age-matched healthy control subjects (group 2).

Data are presented as the median with min. to max. DC Dendritic Cell.

Fig. 3. Examples of IVCM imaging of corneal SNP in a patient with severe obesity (a) and a healthy control subject (b).

In the patient with severe obesity, remarkable reduction in CNFD, CNBD, CNFL, and deteriorated morphology of SNP are well illustrated (a). Normal morphology of corneal SNP can be clearly identified in the image of the healthy control subject (b). The white arrows represent the DCs. The black arrows indicate the immature DCs. Note the increased numbers of DCs in the image (a) compared to the image (b). IVCM: In vivo corneal confocal microscopy, SNP: Sub-basal nerve plexus, CNFD Corneal nerve fibre density, CNBD Corneal nerve branch density, CNFL Corneal nerve fibre length, DC Dendritic cell.

Regarding correlations between the IVCM measurements and BMIs of the participants, CNFD (r = −0.55, p < 0.001), CNFL (r = −0.50, p = 0.003), CNBD (r = −0.64, p < 0.001), and CNFrD (r = 0.39, p = 0.006) correlated negatively, while CNFW (r = 0.42, p = 0.003) and the density of DCs (r = 0.55, p < 0.001) correlated positively with the BMI.

Discussion

Polyneuropathy is a disabling condition of the peripheral nerves affecting up to 7 % of the population in Western countries [27]. While previous studies pointed out type 1 and type 2 DM as the most well-established driver for polyneuropathy, a definitive aetiology cannot be established in 2 out of 10 patients [28, 29]. Moreover, enhanced hyperglycaemia control may not help to reduce the incidence of peripheral neuropathy, particularly in those patients with type 2 DM [30]. For this reason, obesity as a likely cause of small nerve fibre loss has received considerable attention in recent years [31–33]. Current research has suggested that obesity alone may be as strong an independent driver for peripheral neuropathy as prediabetes and type 2 DM. This study was set out with the aim of investigating small nerve fibre damage and corneal inflammation linked to the changes in the morphology of SNP and the count of DCs in severely obese patients using IVCM imaging. The results of this study have shown the decreased CNFL, CNFD, CNBD, CTBD, CNFA, and CNFrD as well as the increased number of DCs in the cornea of patients with severe obesity as compared to age-matched controls.

The past decade has seen the rapid advances in the field of ocular imaging methods. One of these imaging techniques which have recently received greater interest and accessibility to clinicians is IVCM. IVCM is a rapid, non-invasive technique that allows visualization of corneal layers with an acceptable resolution, and can exhibit corneal nerve plexus and its bundles in detail [34]. Accordingly, numerous studies have emphasized the usefulness of IVCM for early detection of peripheral neuropathy not only in patients with dry eye disease (DED) associated with DM, but also other neuropathies, such as chemotherapy-induced, idiopathic small fibre and inflammatory neuropathies [35–39]. It has been suggested that IVCM allows for earlier detection of peripheral neuropathy with comparable diagnostic capability to conventional skin biopsy in patients with prediabetes and DM [40].

While previous studies pointed out DM as the most well-established component of the metabolic syndrome driving peripheral neuropathy, small nerve fibre loss associated with obesity has received considerable attention in recent years [41–43]. Obesity is associated with an inflammation triggering cascade on body homeostasis [44]. In recent decades, obesity has been considered as a low-grade chronic inflammatory state, which is characterized by an increase in systemic markers of inflammation and infiltration of inflammatory cells in adipose tissue [45, 46]. It is proposed that an acute adaptive inflammatory response followed by a long-term pathological inflammatory phase commences after an initial triggering stressor [47, 48]. Experimental data have shown elevated levels of Interleukin 6 (IL-6) and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1) in the cornea of high-fat diet fed mice as well as a negative correlation between corneal nerve density and body weight. Correspondingly, recent experimental studies have reported small nerve fibre damage in the cornea of obese mice and rat models without diabetes [18, 19, 49]. In their observational controlled study (lean controls), Callaghan et al. [33] investigated the association between metabolic syndrome components and polyneuropathy assessment outcomes such as neuropathy symptoms, abnormal sensory examination, and abnormal reflexes in patients with obesity. They concluded that DM, obesity, and waist circumference were the components of the metabolic syndrome most closely associated with peripheral neuropathy. Another study reporting on metabolic syndrome-related polyneuropathy pointed out that the prevalence of symptomatic distal polyneuropathy was more common in patients with additional metabolic syndrome components independent of glycaemic status [50]. In parallel with these results, we detected a significant decrease in the density and length of SNP in our cohort of severely obese patients regardless of coexisting DM, compared to healthy controls. In support of this, we found moderate negative correlations between BMI and the parameters of SNP including CNBD, CNFD, CNFL, and CNFrD as well as a positive correlation with DCs. Taken together, our findings may suggest that obesity may be an isolated driver for early small fibre damage. To the best of our knowledge, there are several recent studies evaluated corneal nerves in a similar group of severely obese patients [20, 21, 51–53]. For instance, Azmi et al. [21] reported that subjects with obesity had significant improvement in the CNFD, CNBD, and CNFL correlated to BMI changes at 1 year following bariatric surgery. Similarly, Tóth et al. [20] noted the impact of pre-diabetic status in obesity that may lead to type-2 DM and thereby worsening corneal small nerve fibre damage. In another study, Iqbal et al. [52] compared the IVCM measurement results between the patients with severe obesity and healthy control group. They stated that the mean corneal keratocyte density, CNFD, CNFL, and CNBD were reduced at baseline compared to control subjects and significantly increased 12 months after bariatric surgery compared to control group. Adam et al. [26] assessed 26 obese patients with DM regarding microvascular complications, particularly neuropathy, before and 12 months after bariatric surgery. Similarly, they reported that CNFD, CNFL and CNBD significantly improved after bariatric surgery. They also found a significant correlation between reduction in blood triglyceride levels and the change in CNFL. In support of this, Azmi et al. [21, 53] stated a clinically relevant association between small nerve fibre damage and serum triglyceride levels. In contrast to the findings of the relevant studies investigated the association between IVCM parameters and lipid parameters, there was no significant association between the levels of triglycerides and any SNP parameters in our study. All patients with obesity in our cohort were already on medical treatment for hyperlipidaemia, and there were also no significant differences in lipid panel parameters between the obese group and controls.

We also aimed to investigate whether corneal nerve damage was associated with an infiltration of DCs. Several studies have shown that immune and nervous systems are closely connected, and corneal neuropathy due to various aetiologies is strongly correlated with an increase in inflammatory cells in the cornea [54–56]. Data from studies involving immunohistochemical staining of human corneal cells using specific markers pointed out the presence of corneal DCs consisting of predominantly Langerhans cells [57, 58]. Moreover, the presence of dendritic cells adjacent to corneal nerve fibres was shown in obese diabetic mice models, and peripheral nerve inflammation induced by hyperglycaemia and obesity was asserted to play a role in aggravating small nerve fibre damage [59]. A recent study by D’Onofrio et al. [60] has demonstrated that significant loss in corneal nerves correlated with increase in Langerhans cell density in patients with type1 DM. Our data showed a significant increase in DC density in severely obese patients compared to healthy controls and this increase was more pronounced in prediabetic/diabetic obese patients. In addition, the correlation analysis demonstrated a significant weak to moderate positive correlation between the DC count and BMI. This finding suggests that inflammation may be the common underlying mechanism inducing obesity- and diabetes-mediated small nerve fibre damage.

A limitation of this study is the relatively small number of patients and controls. Secondly, IVCM parameters could not be compared with other conventional techniques to detect peripheral neuropathy. In addition, this study lacked a longitudinal follow-up to monitor the progression of these changes over time or possible reversal after treatment.

In conclusion, the present study highlights the utility of IVCM in the assessment and early detection of obesity-related small fibre damage and further suggests that severe obesity alone may be a strong independent driver for peripheral neuropathy. Future studies on the current topic, nevertheless, are needed to elucidate the validation of these results.

Summary

What was known before

Obesity is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation

In vivo corneal confocal microscopy provides good diagnostic utility for diabetic neuropathy

What this study adds

Apart from diabetes mellitus, obesity, itself, can lead to a small nerve fibre damage and increase in number of dendritic cells, which are able to be shown by in vivo corneal confocal microscopy in human cornea

In vivo corneal confocal microscopy has a very predictive utility for the development of peripheral neuropathy associated with obesity

Author contributions

SG, FOA, SAT and AET conceived, designed, and conducted the study. SG and FOA recruited participants and collated data. SG and SAT conducted data analysis. SG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Friedman N, Fanning L. Overweight and obesity: an overview of prevalence, clinical impact, and economic impact. Dis Manag. 2004;7:1–6. doi: 10.1089/1093507042317152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: Prevalence and trends, 1960–1994. Int J Obes. 1998;22:39–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson RE, Frank LL, Kristal AR, White E. A comprehensive examination of health conditions associated with obesity in older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:385–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM. Metabolic complications of obesity. Endocrine. 2000;13:155–65. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:13:2:155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckel RH, Krauss RM. American Heart Association call to action: Obesity as a major risk factor for coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1998;97:2099–100. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.21.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung N, Wong TY. Obesity and eye diseases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:180–95. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Himes RW, Smith CW. Tlr2 is critical for diet‐induced metabolic syndrome in a murine model. FASEB J. 2010;24:731–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-141929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu H, Ghosh S, Perrard XD, Feng L, Garcia GE, Perrard JL, et al. T-cell accumulation and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted upregulation in adipose tissue in obesity. Circulation. 2007;115:1029–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu H, Gower RM, Wang H, Perrard XYD, Ma R, Bullard DC, et al. Functional role of CD11c+ monocytes in atherogenesis associated with hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2009;119:2708–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.823740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singleton J, Volckmann E, Graham T, Smith A. Neuropathy associated with nondiabetic obesity. Neurology. 2014;82:S36.006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ylitalo KR, Sowers MF, Heeringa S. Peripheral vascular disease and peripheral neuropathy in individuals with cardiometabolic clustering and obesity: National health and nutrition examination survey 2001-2004. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1642–7. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2150.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lalive PH, Truffert A, Magistris MR, Landis T, Dosso A. Peripheral autoimmune neuropathy assessed using corneal in vivo confocal microscopy. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:403–5. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asghar O, Petropoulos IN, Alam U, Jones W, Jeziorska M, Marshall A, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy detects neuropathy in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2643–6. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruzat A, Qazi Y, Hamrah P. In vivo confocal microscopy of corneal nerves in health and disease. Ocul. Surf. 2017;15:15–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavakoli M, Quattrini C, Abbott C, Kallinikos P, Marshall A, Finnigan J, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy: A novel noninvasive test to diagnose and stratify the severity of human diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1792–7. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang MS, Yuan Y, Gu ZX, Zhuang SL. Corneal confocal microscopy for assessment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A meta-analysi. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:9–14. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petropoulos IN, Alam U, Fadavi H, Asghar O, Green P, Ponirakis G, et al. Corneal nerve loss detected with corneal confocal microscopy is symmetrical and related to the severity of diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3646–51. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coppey L, Davidson E, Shevalye H, Obrosov A, Torres M, Yorek MA. Progressive loss of corneal nerve fibers and sensitivity in rats modeling obesity and type 2 diabetes is reversible with omega-3 fatty acid intervention: Supporting cornea analyses as a marker for peripheral neuropathy and treatment. Diabetes. Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2020;13:1367–84. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S247571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hargrave A, Courson JA, Pham V, Landry P, Magadi S, Shankar P, et al. Corneal dysfunction precedes the onset of hyperglycemia in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. PLoS One. 2020; 15. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Tóth N, Silver DM, Balla S, Káplár M, Csutak A. In vivo corneal confocal microscopy and optical coherence tomography on eyes of participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus and obese participants without diabetes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259:3339–50. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azmi S, Ferdousi M, Liu Y, Adam S, Iqbal Z, Dhage S, et al. Bariatric surgery leads to an improvement in small nerve fibre damage in subjects with obesity. Int J Obes. 2021;45:631–8. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-00727-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:S62-9. 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Anon.Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee.; 1995. [PubMed]

- 24.Davidson EP, Coppey LJ, Holmes A, Yorek MA. Changes in corneal innervation and sensitivity and acetylcholine-mediated vascular relaxation of the posterior ciliary artery in a type 2 diabetic rat. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:1182–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalteniece A, Ferdousi M, Adam S, Schofield J, Azmi S, Petropoulos I, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy is a rapid reproducible ophthalmic technique for quantifying corneal nerve abnormalities. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adam S, Azmi S, Ho JH, Liu Y, Ferdousi M, Siahmansur T, et al. Improvements in Diabetic Neuropathy and Nephropathy After Bariatric Surgery: a Prospective Cohort Study. Obes. Surg. 2020. 10.1007/s11695-020-05052-8. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33104989/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.England JD, Asbury AK. Peripheral neuropathy. Lancet. 2004;363:2151–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16508-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lubec D, Müllbacher W, Finsterer J, Mamoli B. Diagnostic work-up in peripheral neuropathy: an analysis of 171 cases. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:723–7. doi: 10.1136/pgmj. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyck PJ, Oviatt KF, Lambert EH. Intensive evaluation of referred unclassified neuropathies yields improved diagnosis. Ann Neurol. 1981;10:222–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callaghan B, Feldman E. The metabolic syndrome and neuropathy: therapeutic challenges and opportunities. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:397–403. doi: 10.1002/ana.23986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanewinckel R, Drenthen J, Ligthart S, Dehghan A, Franco OH, Hofman A, et al. Metabolic syndrome is related to polyneuropathy and impaired peripheral nerve function: a prospective population-based cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1336–42. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Callaghan BC, Gao L, Li Y, Zhou X, Reynolds E, Banerjee M, et al. Diabetes and obesity are the main metabolic drivers of peripheral neuropathy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5:397–405. doi: 10.1002/acn3.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Callaghan BC, Xia R, Reynolds E, Banerjee M, Rothberg AE, Burant CF, et al. Association Between Metabolic Syndrome Components and Polyneuropathy in an Obese Population. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1468–76. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grupcheva CN, Wong T, Riley AF. Assessing the sub-basal nerve plexus of the living healthy human cornea by in vivo confocal microscopy. In: Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 30. Clin Exp Ophthalmol; 2002;187–90. 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2002.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Misra SL, Patel DV, McGhee CN, Pradhan M, Kilfoyle D, Braatvedt GD, et al. Peripheral neuropathy and tear film dysfunction in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Res. 2014;2014:848659. doi: 10.1155/2014/848659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferdousi M, Azmi S, Petropoulos IN, Fadavi H, Ponirakis G, Marshall A, et al. Corneal Confocal Microscopy Detects Small Fibre Neuropathy in Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer and Nerve Regeneration in Chemotherapy Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tavakoli M, Marshall A, Pitceathly R, Fadavi H, Gow D, Roberts ME, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy: a novel means to detect nerve fibre damage in idiopathic small fibre neuropathy. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider C, Bucher F, Cursiefen C, Fink GR, Heindl LM, Lehmann HC. Corneal confocal microscopy detects small fiber damage in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2014;19:322–7. doi: 10.1111/jns.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleischer M, Lee I, Erdlenbruch F, Hinrichs L, Petropoulos IN, Malik RA, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy differentiates inflammatory from diabetic neuropathy. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:89. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02130-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tavakoli M, Petropoulos IN, Malik RA. Corneal confocal microscopy to assess diabetic neuropathy: an eye on the foot. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:1179–89. doi: 10.1177/193229681300700509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziegler D, Rathmann W, Dickhaus T, Meisinger C, Mielck A, KORA Study Group Prevalence of polyneuropathy in pre-diabetes and diabetes is associated with abdominal obesity and macroangiopathy: the MONICA/KORA Augsburg Surveys S2 and S3. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:464–9. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee CC, Perkins BA, Kayaniyil S, Harris SB, Retnakaran R, Gerstein HC, et al. Peripheral Neuropathy and Nerve Dysfunction in Individuals at High Risk for Type 2 Diabetes: The PROMISE Cohort. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:793–800. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu B, Hu J, Wen J, Zhang Z, Zhou L, Li Y, et al. Determination of peripheral neuropathy prevalence and associated factors in Chinese subjects with diabetes and pre-diabetes - ShangHai Diabetic neuRopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetics Study (SH-DREAMS) PLoS One. 2013;8:e61053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buckman LB, Hasty AH, Flaherty DK, Buckman CT, Thompson MM, Matlock BK, et al. Obesity induced by a high-fat diet is associated with increased immune cell entry into the central nervous system. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;35:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mancuso P. The role of adipokines in chronic inflammation. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2016;5:47–56. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S73223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin L, Lee JH, Buras ED, Yu K, Wang R, Wayne Smith C, et al. Ghrelin receptor regulates adipose tissue inflammation in aging. Aging. 2016;8:178–91. doi: 10.18632/aging.100888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yorek MS, Obrosov A, Shevalye H, Holmes A, Harper MM, Kardon RH, et al. Effect of diet-induced obesity or type 1 or type 2 diabetes on corneal nerves and peripheral neuropathy in C57Bl/6J mice. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2015;20:24–31. doi: 10.1111/jns.12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Callaghan BC, Xia R, Banerjee M, de Rekeneire N, Harris TB, Newman AB, et al. Health ABC Study. Metabolic Syndrome Components Are Associated With Symptomatic Polyneuropathy Independent of Glycemic Status. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:801–7. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ho JH, Adam S, Azmi S, Ferdousi M, Liu Y, Kalteniece A, et al. Male sexual dysfunction in obesity: The role of sex hormones and small fibre neuropathy. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iqbal Z, Kalteniece A, Ferdousi M, Adam S, D’Onofrio L, Ho JH, et al. Corneal keratocyte density and corneal nerves are reduced in patients with severe obesity and improve after bariatric surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62:20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azmi S, Ferdousi M, Liu Y, Adam S, Siahmansur T, Ponirakis G, et al. The role of abnormalities of lipoproteins and HDL functionality in small fibre dysfunction in people with severe obesity. Sci Rep. 2021;11:12573. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khan A, Li Y, Ponirakis G, Akhtar N, Gad H, George P, et al. Corneal immune cells are increased in patients with multiple sclerosis. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2021;10:19. doi: 10.1167/tvst.10.4.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thimm A, Carpinteiro A, Oubari S, Papathanasiou M, Kessler L, Rischpler C, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy to detect early immune-mediated small nerve fibre loss in AL amyloidosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9:853–63. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiao L, Zhang Y, Wang H, Fan D. Corneal confocal microscopy in the evaluation of immune-related motor neuron disease syndrome. BMC Neurol. 2022;22:138. doi: 10.1186/s12883-022-02667-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mayer WJ, Irschick UM, Moser P, Wurm M, Huemer HP, Romani N, et al. Characterization of antigen-presenting cells in fresh and cultured human corneas using novel dendritic cell markers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4459–67. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mayer WJ, Mackert MJ, Kranebitter N, Messmer EM, Grüterich M, Kampik A, et al. Distribution of antigen presenting cells in the human cornea: correlation of in vivo confocal microscopy and immunohistochemistry in different pathologic entities. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:1012–8. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.696172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leppin K, Behrendt AK, Reichard M, Stachs O, Guthoff RF, Baltrusch S, et al. Diabetes mellitus leads to accumulation of dendritic cells and nerve fiber damage of the subbasal nerve plexus in the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:3603–15. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D’Onofrio L, Kalteniece A, Ferdousi M, Azmi S, Petropoulos IN, Ponirakis G, et al. Small Nerve Fiber Damage and Langerhans Cells in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes and LADA Measured by Corneal Confocal Microscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62:5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.6.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.