Abstract

In more recent years, coordinated specialty care (CSC) has moved toward the harmonization and delivery of measures across programs to provide measurement informed care for psychosis. However, it remains unclear what strategies can be utilized to support the integration of a core assessment battery in clinical care. This column evaluates the use of a multifaceted technical assistance (TA) strategy on the delivery and completion of an assessment battery in CSC. The findings suggest that a multifaceted TA strategy can support the integration of a comprehensive assessment battery delivered by providers. Similar TA strategies may assist CSC as they adapt and move toward providing data-driven care in an effort to improve quality of care.

In recent years, coordinated specialty care (CSC) have moved towards the harmonization of measures and the collection of client level data in an effort to implement data-informed care, through the use of outcome and process measures (e.g., assessment battery) (1). A core assessment battery often includes several provider-rates scales and client self-report measures that assess psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, and service utilization (2). As CSC continues to adapt and improve, the provision of data driven care has become an essential component for many models (3). Yet the implementation of this data driven component of care in real world settings has received little attention.

At the program level the collection and monitoring of outcomes measures can be used for continuous quality improvement and to improve clinical practice when it is part of a feedback monitoring system for providers (4). The delivery of measures and collection of data can also set the stage for mental health agencies to provide measurement-based care (MBC), which has been linked to improved client outcomes for other serious mental illnesses (e.g., major depression) (5). The data collected often provides empirical evidence to inform decision-makers (e.g., state and federal) on how to distribute funding for services and it is often a requirement by funding agencies (4). Yet, the use and delivery of measures by providers is often challenging and completion rates are generally low (2,6).

What has not been well documented is the level of support, education, and/or training needed to overcome barriers to integrate an assessment battery within CSC. To address these gaps in the context of CSC, we assessed the enactment of a technical assistance (TA) and support program in improving measure completion in CSC as the first step toward implementing MBC.

Setting

From January to December 2020, nine CSC implemented in community-based outpatient mental health agencies (7), in the Pacific Northwest, U.S. participated in the study and during the 12-month period provided services to 247 clients. Providers were responsible for completing and entering provider-rated scales and facilitating the completion of self-report measures by clients using an online measurement delivery and data platform, a tool developed in Research Electronic Data Capture. The assessment battery included two provider-rated scales: Clinician-Rated Dimensions of Psychosis Symptom Severity collected monthly and service utilization collected weekly, and six client self-report measures: Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7, delivered monthly or quarterly. Washington State Institutional Review Board determined the study as exempt

Implementation Strategy

The unit of implementation strategy was at the program level and the end users of change were providers. In-Person Training –The 12-hour in-person training for providers and included a lecture-style presentation that provided an overview of the online measurement delivery and data platform; evidence to support the use of clinical and functional measures integrated in clinical care; self-report measures and cut-off scores; provider-rated scales; and examples of how the network utilizes data (e.g., to support legislature, program evaluation). Training also involved hands on assistance with tablet devices provided to each program, mock data entry, and small group discussion. Supplement paper materials included an overview of all measures and corresponding cut-off scores, delivery schedule for measures, and recommendations for the distribution of measures across team members to reduce the level of burden on one provider. As Needed Booster Training Sessions – A condensed version of the in-person training was conducted through videoconference to meet the training needs of new hires due to turnover or to serve as a refresher for providers. Consultation – Technical assistance utilized a goal focused approach based on principles of quality improvement and was delivered monthly via videoconference meetings held with program directors and CSC experts (8). These meetings included audit and feedback on the quality of the data, discussion about measurement delivery and competition rates in the past month, and addressed internal and external barriers that informed modifications to the online measurement delivery and data platform and informed the focus of subsequent meetings, which were tailored based on site. Continuous technical support was offered to all providers and could be obtained by email, videoconference, or telephone calls to troubleshoot issues and raise additional concerns or suggestions for improvement.

Outcomes

Attendance and Engagement – Program directors had the opportunity to participate in at least 12 monthly consultation meetings by videoconference and attendance was tracked. Ongoing participation in consultation included 1) the number (%) of consultation sessions attended, 2) mean number of consultation meetings across programs, and 3) the number of booster sessions delivered. Measurement Completion – One year of monthly administrative data pulls from the online measurement delivery and data platform were used to assess measurement completion by providers and clients. Completion was operationalized as when measures were delivered, and questions completed by the client with the support of the provider or outside of session via text or email.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in measure completion were examined using logistic generalized linear mixed effects (GLMM) models with a random intercept to capture the differences between sites, a random intercept to capture the repeated outcomes on participants (over 12 months) nested within site, and a fixed effect for time (month). Missing values were handled by maximum likelihood estimation, allowing unbiased estimation when data are missing at random. Separate models were fit for each measure completion outcome (total measures completed, self-report measures completed, and provider ratings completed). Results are reported using odds ratios (OR) and are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI) as well as the change in probability for ease of interpretation. A two-tailed alpha error rate of 0.05 was the statistical significance threshold. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.6.2). Generalized linear mixed effects models were fit using the glmmTMB package and marginal means were calculated using the emmeans package.

Participation and Attendance

Over the course of 12 months, 73 of 103 (71%) TA meetings were attended by program directors. After the initial training, 22 booster sessions (M=2.4; range 1– 4 sessions) were delivered virtually. Meeting duration ranged from 16 to 60 minutes, with longer meetings focused on features of the online data platform and/or strategies to engage clients.

Changes in Measurement Completion Over Time

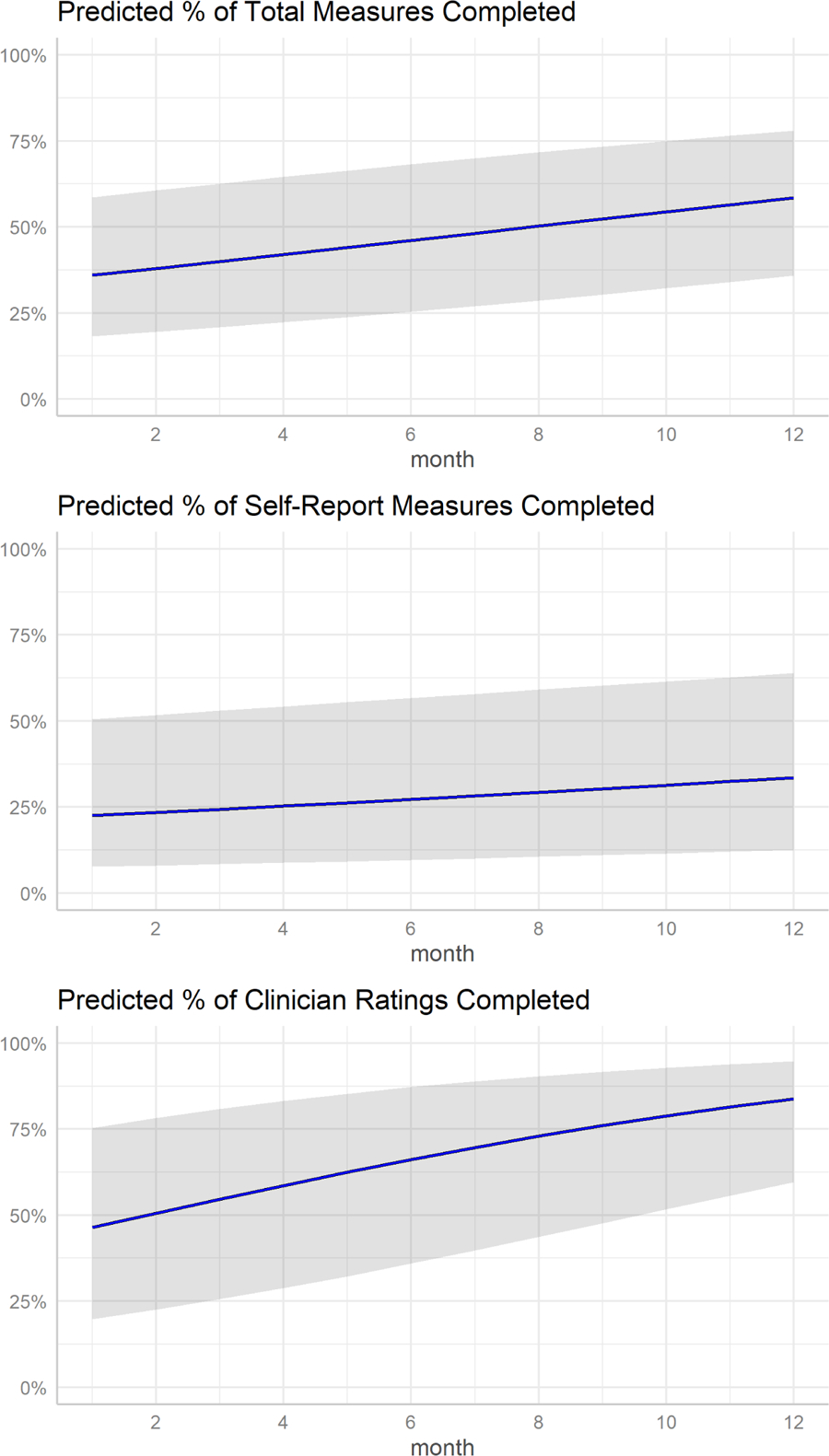

A total of 5,831 provider-rated scales and 3,190 self-report measures were completed across 12 months. Of the self-report measures, 109 (3%) were independently completed and captured by email or text message. Over the 12-month study period, overall measure completion significantly increased (OR=1.09, CI:1.07–1.10, p< 0.001). Among clients, the completion of self-report measures significantly increased (OR=1.05, CI:1.03–1.07, p< 0.001) and the competition of provider-rated scales significantly increased (OR=1.18, CI:1.15–1.20, p< 0.001). Of the three outcomes investigated, provider-rating scales completion showed the most improvement over time (from 47% at month 1 to 84% at month 12). Figure 1 demonstrates the improvement in measure completion over time.

Figure 1.

Predicted percent of measure completion over time

Note. Gray bands represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion and Conclusions

These findings indicate significant improvements across 12 months in the delivery and completion of provider-rated scales and client self-report measures in CSC during implementation, however, results revealed a more pronounced improvement in the completion of provider-rated scales. Prior work suggests that CSC providers experience more challenges with administering and having clients complete self-report measures than they do with completing provider-rated scales (2). Our findings demonstrate that while there was a slight increase in the completion of client self-report measures, Figure 1 potentially highlights the difficulties that providers may have engaging clients in the process of completing measures and potentially conveying the utility in doing so.

While our findings are primarily focused on the delivery and completion of an assessment battery is one component in the provision of data-informed care. In a practice setting there are limitations to simply focusing only on completion rates and not emphasizing the active involvement of clients. What is also a crucial component that warrants additional attention is how the active involvement of clients or lack thereof impacts the quality and validity of responses and meaningful integration into care. During pre-implementation of an assessment battery or prior to scale up, CSC should engage in a rapid learning participatory approach to ensure measures selected are meaningful to clients, as those with lived experience tend to be excluded during the pre-implementation phase of evidence-based practices. The use of task shifting or sharing approaches, whereby tasks are shifted from one role to another to better utilize resources, could also serve as a way to further integrate the role of peer specialists (9). Rather than providers, the role of peer specialists can be used to better address client needs and improve responsiveness to data driven components of CSC. For instance, peer data champions are a role previously used in learning healthcare systems to inform current clients on how data is used to personalize treatment (e.g., utility) and gather feedback from clients that can be integrated to into care (quality improvement) (10).

It should also be noted that the TA strategy was utilized within a network of CSC and supported by an academic-community partnership funded by the state and may not be generalizable to all CSC, without this additional level of support. At a more practical level is understanding the amount of external support needed (e.g., training, coaching) and associated cost for CSC to integrate an assessment battery especially for programs in low resource settings.

The findings from study addresses an understudied area in the implementation of CSC and potentially suggests the feasibility TA strategy to facilitate the delivery of an assessment battery in CSC. It also further highlights the need for stakeholder input throughout the implementation process and additional strategies to increase client buy-in in the utility of data-informed care as programs move towards implementing MBC.

Highlights.

There is insufficient evidence on how to support CSC integrate assessment batteries as they move towards providing more data-informed care.

Results demonstrated improvement in the delivery and completion of provider-rated scales and self-reported measures.

Additional work is needed that involves clients/peers throughout implementation to ensure the meaningful completion of measures and quality of data.

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible in part by funding from the Washington State Health Care Authority, Division of Behavioral Health and Recovery (DBHR).

Funding

The work was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH117457)

Footnotes

Previous Presentation: The data from this paper was presented at the 6th Society for Implementation Research Collaboration in San Diego, California, September 8–10, 2022

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- 1.Early Psychosis Intervention Network (EPINET). National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-funded-by-nimh/research-initiatives/early-psychosis-intervention-network-epinet

- 2.Kline ER, Johnson KA, Szmulewicz A, et al. : “Real-world” first-episode psychosis care in Massachusetts: Lessons learned from a pilot implementation of harmonized data collection. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 16: 678–682, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinssen RK, Azrin ST: A National Learning Health Experiment in Early Psychosis Research and Care. PS appi.ps 20220153, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickman L: A Measurement Feedback System (MFS) Is Necessary to Improve Mental Health Outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47: 1114–1119, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwan B, Rickwood DJ: A systematic review of mental health outcome measures for young people aged 12 to 25 years. BMC Psychiatry 15, 2015.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4647516/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garland AF, Kruse M, Aarons GA: Clinicians and outcome measurement: What’s the use? The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 30: 393–405, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oluwoye O, Reneau H, Stokes B, et al. : Preliminary evaluation of Washington State’s early intervention program for first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services 71: 228–235, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A: The Quality Implementation Framework: A Synthesis of Critical Steps in the Implementation Process. Am J Community Psychol 50: 462–480, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, et al. : Task-Sharing Approaches to Improve Mental Health Care in Rural and Other Low-Resource Settings: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Rural Health 34: 48–62, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles SE, Allen D, Donnelly A, et al. : Participatory codesign of patient involvement in a Learning Health System: How can data‐driven care be patient‐driven care? Health Expect 25: 103–115, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]