Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Sleep deprivation increases CSF Aβ and tau levels, however sleep’s effect on Aβ and tau in plasma is unknown.

METHODS:

In a cross-over design, CSF Aβ and tau concentrations were measured in five cognitively normal individuals had blood and CSF collected every two hours for thirty-six hours during sleep-deprived and normal sleep control conditions.

RESULTS:

Aβ40, Aβ42, unphosphorylated tau-threonine-181 (T181), unphosphorylated tau-threonine-217 (T217), and phosphorylated T181 (pT181) concentrations increased ~35–55% in CSF and decreased ~5–15% in plasma during sleep deprivation. CSF/plasma ratios of all AD biomarkers increased during sleep deprivation while the CSF/plasma albumin ratio, a measure of blood-CSF barrier permeability, decreased. CSF and plasma Aβ42/40, pT181/T181, and pT181/Aβ42 ratios were stable longitudinally in both groups.

DISCUSSION:

These findings show that sleep loss alters some plasma AD biomarkers by lowering brain clearance mechanisms and needs to be taken into account when interpreting individual plasma AD biomarkers but not ratios.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, sleep, biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

A key early step in the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the extracellular aggregation of amyloid-β (Aβ) as insoluble plaques that begins ~15–20 years before the onset of cognitive deficits [1]. Accumulation of hyper-phosphorylated tau (p-tau) tangles and neuronal death leads to cognitive dysfunction. Since substantial neuronal loss has occurred by the onset of cognitive symptoms, there is a critical need to identify cognitively unimpaired or mildly impaired individuals with Aβ plaques for secondary prevention trials. Multiple biofluid and imaging markers for in vivo detection of amyloid deposition have been validated: 1) cerebrospinal (CSF) Aβ42 concentration [2]; 2) CSF ratios for Aβ42/40, CSF total-tau/Aβ42, CSF p-tau/Aβ42 [3, 4]; and 3) positron emission tomography (PET) neuroimaging using radiotracers for fibrillar Aβ [5, 6]. Increasingly, plasma markers have been validated with high sensitivity and specificity for Aβ pathology [7–11].

Studies involving serial sampling of CSF in humans via indwelling lumbar catheters showed that soluble forms of Aβ and tau fluctuate with sleep-wake activity, increasing during wakefulness and decreasing during sleep [12, 13]. Overnight sleep deprivation increases the CSF concentrations of Aβ and tau by ~30–50% and also has site-specific effects on tau phosphorylation [14, 15]. Given these findings, factors such as sleep loss and time of day need to be taken into account when designing and interpreting studies using CSF AD biomarkers but the effects of sleep on plasma AD biomarkers are not as well-understood. Serial blood sampling during 24 hours of sleep deprivation was reported to elevate plasma Aβ40 and decrease the Aβ42/40 ratio during the night compared to the day, although there was not a normal sleep control group for comparison [16]. In contrast, another study found that acute sleep loss increased plasma tau levels in the morning compared to the evening but did not affect plasma Aβ [17]. None of these previous studies collected paired blood and CSF samples.

In this study, we measured multiple forms of Aβ and tau in paired blood and CSF samples collected every 2 hours for 36 hours under both sleep-deprived and normal sleep control conditions in a cross-over study design to determine the effect of acute sleep loss on plasma AD biomarkers.

METHODS

Participants and Sample Collection

Five cognitively normal amyloid-negative participants aged 30–60 underwent both sleep-deprived and normal sleep conditions in a cross-over design study. As previously reported,[14] all participants reported no clinical sleep disorders or subjective daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scores [1 participant did not complete): mean=3.75, standard deviation (SD)=2.99, range=1–8) and were screened to exclude sleep-disordered breathing with a home sleep apnea test (all with Respiratory Event Index <5). Participants were either assigned normal control or sleep-deprived conditions, and then returned ~4–6 months later on average for cross-over to the other condition. Three participants completed the control condition followed by sleep deprivation, and two participants completed sleep deprivation followed by control. Participant characteristics are listed in Table 1. The effect of sleep deprivation in these participants on CSF Aβ, tau, and p-tau were previously reported [14, 15]. The study protocol was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board and an independent safety committee oversaw the entire study with regular review of adverse events and approval to continue. All participants completed written informed consent and were compensated for their participation in the study.

Table 1:

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Control (n = 5)* | Sleep-Deprived (n=5)* |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Sex, M/F | 2/3 | 2/3 |

| Race, C/AA | 2/3 | 2/3 |

| MMSE | ||

| CSF Aβ42/40 at hour 0 | ||

| Plasma Aβ42/40 at hour 0 | ||

| SSS on Day of Catheter Placement | ||

| Overnight TST (min) | ||

| Overnight SE (%) |

AA = African American; C = Caucasian; F = female; M = male; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; Aβ = amyloid-β; SSS = Stanford Sleepiness Scale; TST = total sleep time; SE = sleep efficiency; SD = standard deviation.

5 participants completed both the sleep-deprived and normal sleep groups with interventions 4–6 months apart; all assessments were completed for each intervention group.

Venous and lumbar catheters were placed at ~7:00 a.m. on the first day. CSF and plasma were obtained every 2 hours for 36 hours. All CSF samples were collected and processed as previously described [14, 15, 18]. Blood was drawn into EDTA K2 containing Tube (BD 368589). The tubes were centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Then, plasma samples were aliquoted with 1 ml volumes and frozen by dry ice and later stored at −80 °C.

Measurement of CSF and Plasma Aβ and Tau

CSF Aβ and tau were measured by immunoprecipitation (IP) and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) as previously described [14, 15]. We conducted the plasma Aβ IP LC/MS as reported [10] except all handling processes were performed by Hamilton Microlab STAR Liquid Handling System (Hamilton, NV, U.S.A) in an automated processing method. Human plasma tau separation was performed as previously described [19] with modifications. Frozen plasma aliquots of 1 ml were thawed at room temperature and centrifuged at 21,130 g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Plasma samples were spiked with 2.5 ng of 15N-labeled recombinant 2N4R tau internal standard (gift from Guy Lippens, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Universite de Lille, Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France) with a mixture of 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), 1% NP-40, and 5 mM guanidine and then immunoprecipitated with 20 μl Tau1 antibody cross-linked to sepharose beads at 4°C overnight. The pelleted sepharose beads were washed with 25 mM TEABC and then the sample was extracted with 200 μL 0.1% TFA. The extracted samples were loaded on an Oasis HLB 96-well μElution plate 30 μm, 2 mg Sorbent per well (Waters) conditioned with 200 μl MeOH and 200 μl 0.1% TFA. After loading, samples were desalted with 200 μl 0.1% TFA and then eluted with 100 μl 27.5% acetonitrile-0.1% TFA solution. After drying, absolute quantitation peptides (Life Technologies) to 5 and 0.5 fmol for each unphosphorylated and phosphorylated peptide were added to the samples for quantitation and then digested with 400 ng trypsin in 25mM TEABC for 16 hours. Finally, samples were purified by solid phase extraction on C18 TopTips (Glygen) and desalted and eluted with 100 μl 60% ACN, 0.1% FA. The eluate was lyophilized and resuspended in 12.5 μl 2% ACN, 0.1% FA before nano-LC-MS/high-resolution MS analysis by using nanoAcquity ultra performance LC system (Waters) coupled to an Orbitrap Tribrid Lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating as reported [20]. Skyline software (MacCoss Lab, University of Washington, Seattle, WA) was used to extract the LC-MS data.

Measurement of CSF/Plasma Albumin Ratio

CSF albumin and plasma albumin were quantified by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the kit instructions. CSF and plasma from all time points of each participant were run in duplicate on the same ELISA plate.

Statistics Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28 (IBM, Armonk, NY). All serial CSF and plasma Aβ and tau data were analyzed with general linear mixed models in order to account for the dependences of the longitudinal measurements [21]. Comparisons were made between conditions with individual within-participant data and not group averaged data. Intervention group and time of day were treated as fixed effects. Random intercepts and slopes for time were used to accommodate individual variation. The Akaike Information Criterion was used to compare covariance structures and compound symmetry was selected as the best fit. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The normality assumption was verified through residual plots.

RESULTS

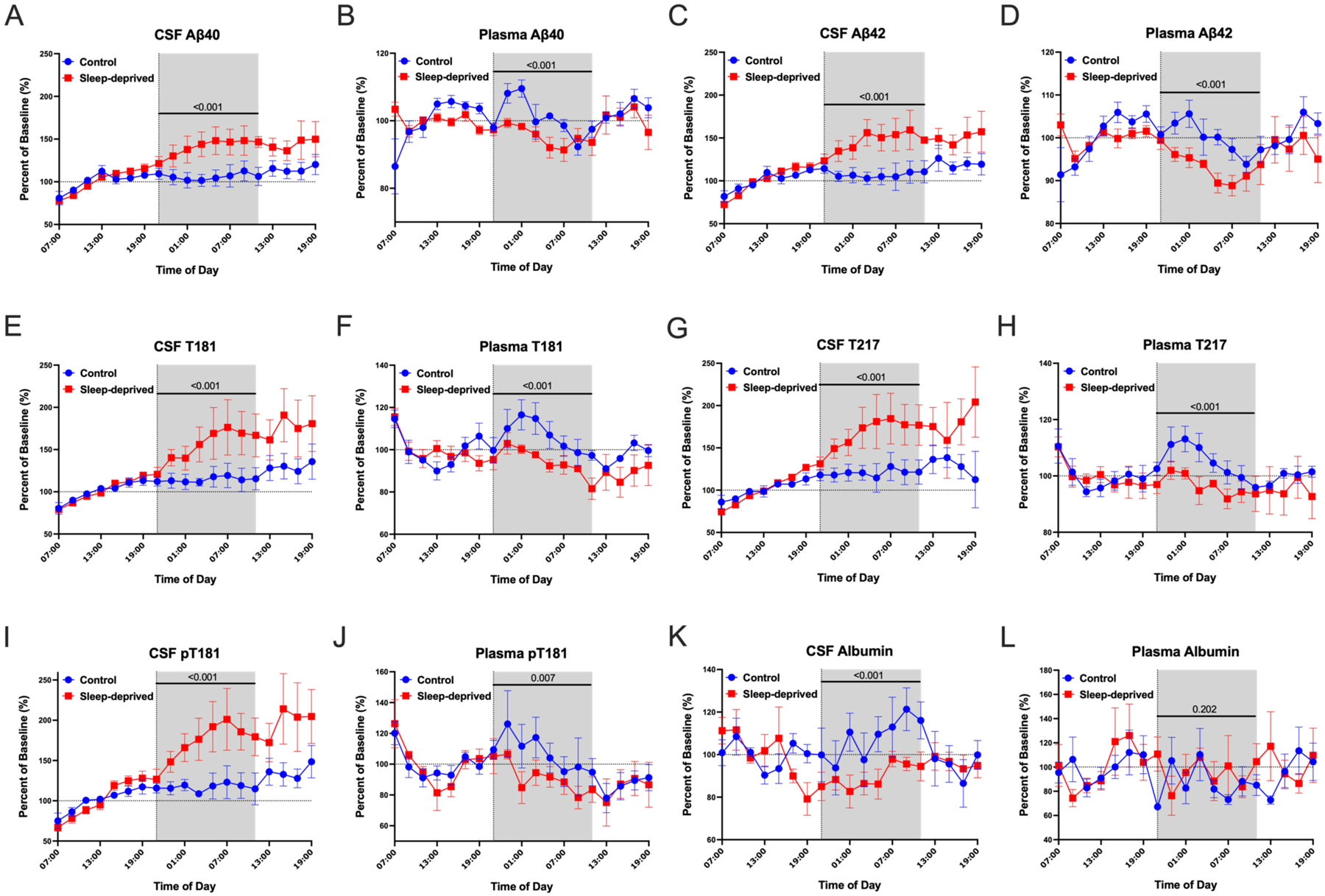

Aβ40, Aβ42, non-phosphorylated tau-threonine-181 (T181, sometimes referred to as “total tau”), phosphorylated T181 (pT181), and non-phosphorylated tau-threonine-217 (T217, sometimes referred to as “total tau”) were measured in both CSF and plasma. As in our previous work, Aβ and tau concentrations were normalized to the average of hours 0–12 (07:00–19:00) before the intervention started when all participants were awake and the overnight period was defined as 21:00–11:00 to account for the transit time from brain to the lumbar catheter [14, 15]. Mean overnight concentrations of CSF Aβ40, Aβ42, T181, pT181, and T217 increased ~35–55% above baseline during sleep deprivation while plasma Aβ and tau decreased 5–15% below baseline during sleep deprivation (Figure 1A–J).

Figure 1:

Sleep loss decreases plasma but increases CSF AD biomarkers. Mean overnight Aβ, tau and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) concentration normalized to a baseline of the average concentrations over hours 0–12 (07:00–19:00) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma. Sleep deprivation increased overnight Aβ40, Aβ42, T181, T217, and pT181 levels by 35–55% from baseline during sleep deprivation compared with controls. In plasma, sleep deprivation decreased overnight Aβ40, Aβ42, T181, T217, and pT181 by 5–15% in plasma compared to participants in the control group (A-J). The overnight albumin level in CSF decreased ~18% from baseline during sleep deprivation, but in plasma was not significantly different in the sleep-deprived group compared with the control (K, L). The overnight period during the intervention night was defined as hours 18 to 28 (21:00–11:00) to account for the transit time of CSF from the brain to the lumbar catheter (shaded area). Blue: control; Red: sleep-deprived; Error bars indicate standard error. The vertical dashed line is the intervention start time. The horizontal dashed line is at 100% of baseline. P-values are shown.

Overnight CSF and plasma Aβ and tau concentrations showed inverse changes during sleep-deprived compared to control conditions. To test if this inverse effect of sleep deprivation on CSF and plasma Aβ and tau was due to changes in transport across the blood-CSF barrier, we measured CSF and plasma albumin. Albumin is abundant in blood and neither synthesized nor metabolized intrathecally [22]. Although there were no significant group differences in plasma albumin during sleep deprivation, the mean overnight concentration of CSF albumin decreased ~18% from baseline in the sleep-deprived group suggesting that transport from blood to CSF was impaired or blood-brain barrier integrity was increased (Figure 1K–L). The overnight mean group differences for CSF and plasma Aβ40, Aβ42, T181, T217, pT181, and albumin are shown in Table 2.

Table 2:

Mixed Model Results for Change in Overnight (21:00–11:00) CSF and Plasma Aβ, Tau, Phosphorylated Tau, and Albumin from Baseline

| CSF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker | Factor | Pairwise Comparison | Mean Difference (95% CI) | F (df) | p |

| Aβ40, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +33.675 (24.480, 42.869) | 53.71 (1,59.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 0.612 (7,59.00) | 0.743 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.658 (7,59.00) | 0.706 | |||

| Aβ42, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +37.406 (26.822, 47.989) | 50.02 (1,59.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 0.525 (7,59.00) | 0.812 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.983 (7,59.00) | 0.452 | |||

| T181, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +40.499 (27.316, 53.683) | 37.76 (1,60.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 1.34 (7,60.00) | 0.246 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.863 (7,60.00) | 0.541 | |||

| T217, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +45.995 (34.250, 57.740) | 61.37 (1,60.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 1.54 (7,60.00) | 0.171 | |||

| Intervention x time | 1.13 (7,60.00) | 0.359 | |||

| pT181, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +55.110 (40.003, 70.217) | 53.25 (1,60.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 1.50 (7,60.00) | 0.186 | |||

| Intervention x time | 1.18 (7,60.00) | 0.328 | |||

| Albumin, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | −18.140 (−25.926, −10.353) | 21.71 (1,60.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 1.56 (7,60.00) | 0.164 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.495 (7,60.00) | 0.834 | |||

| Plasma | |||||

| Biomarker | Factor | Pairwise Comparison | Mean Difference (95% CI) | F (df) | p |

| Aβ40, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | −5.293 (−8.023, −2.563) | 15.04 (1,60.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 4.01 (7,60.00) | 0.001 | |||

| Intervention x time | 1.48 (7,60.00) | 0.190 | |||

| Aβ42, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | −6.315 (−9.080, −3.550) | 20.87 (1,60.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 2.68 (7,60.00) | 0.018 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.805 (7,60.00) | 0.586 | |||

| T181, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | −11.351 (−16.386, −6.316) | 20.35 (1,59.03) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 3.48 (7,59.03) | 0.003 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.487 (7,59.03) | 0.840 | |||

| T217, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | −8.302 (−12.171, −4.434) | 18.43 (1,60.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 2.77 (7,60.00) | 0.015 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.578 (7,60.00) | 0.771 | |||

| pT181, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | −15.456 (−26.537, −4.375) | 7.79 (1,59.12) | 0.007 |

| Time of day | 1.61 (7,59.12) | 0.151 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.269 (7,59.12) | 0.964 | |||

| Albumin, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +8.612 (−4.740, 21.964) | 1.67 (1,57.16) | 0.202 |

| Time of day | 0.748 (7,57.10) | 0.633 | |||

| Intervention x time | 1.31 (7,57.10) | 0.264 | |||

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; Aβ = amyloid-β; T181 = unphosphorylated tau-181; T217 = unphosphorylated tau-217; pT181 = phosphorylated tau-181; CI = confidence intervals; df = degrees of freedom

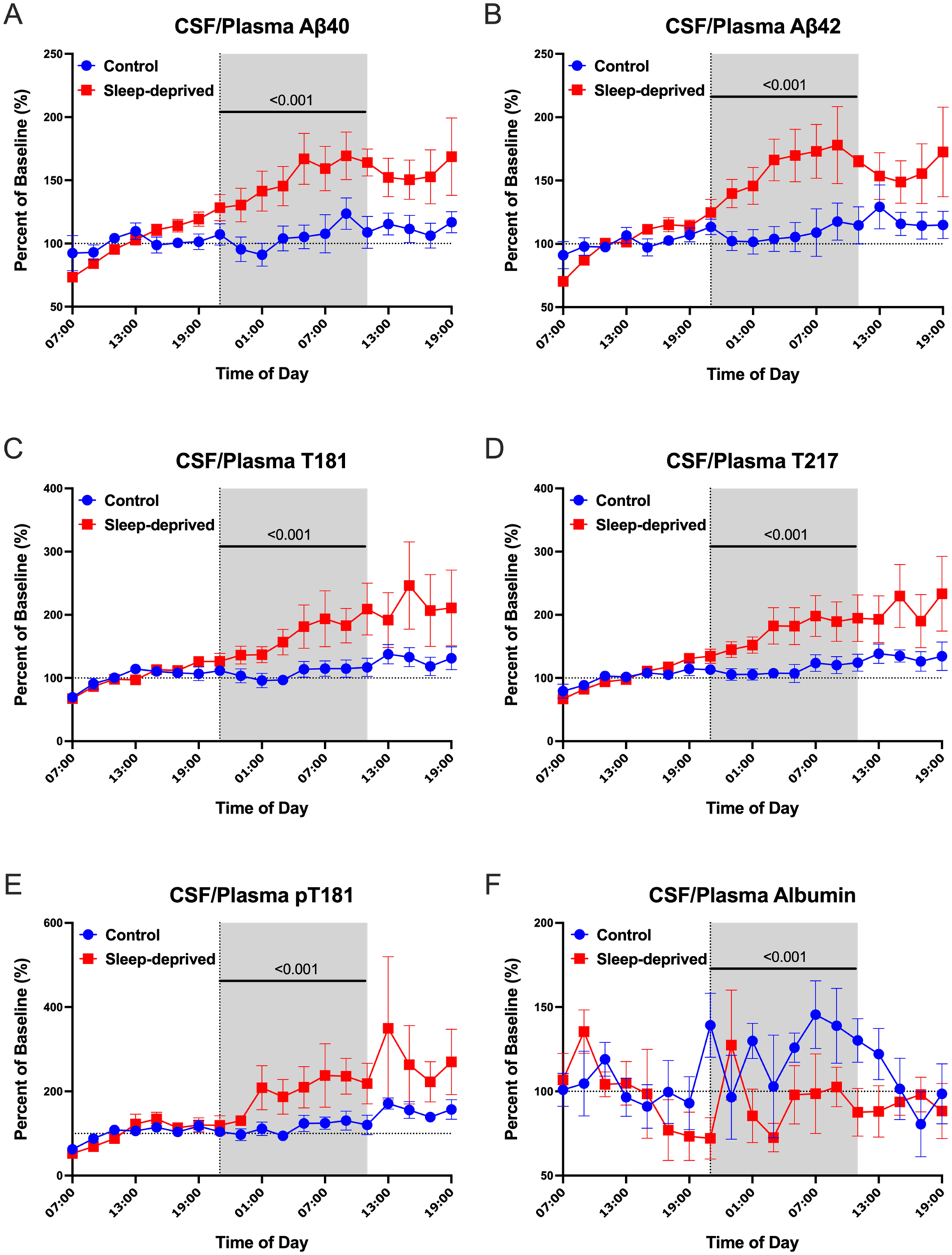

The CSF/plasma albumin ratio index is commonly used to evaluate blood-CSF barrier integrity by the quantitative measurements of albumin in CSF and plasma collected simultaneously [22, 23]. In addition to the CSF/plasma albumin ratio, we also compared the CSF/plasma ratio of Aβ40, Aβ42, T181, T217, and pT181 normalized to the average of hours 0–12 (07:00–19:00) before the intervention started. We found that the overnight CSF/plasma ratio of Aβ40, Aβ42, T181, T217, and pT181 increased during sleep deprivation but the CSF/plasma albumin ratio decreased during sleep deprivation (Figure 2A–F, Table 3). Since the concentration of albumin is highest in plasma and the concentrations of Aβ and tau are highest in CSF, these findings suggest that protein transport between CSF and plasma was impaired by sleep loss.

Figure 2:

Blood-CSF transport impaired by sleep loss. CSF/Plasma Protein Ratio normalized to a baseline of the average ratio over hours 0–12 (07:00–19:00). The CSF/plasma ratio increased for Aβ40, Aβ42, T181, T217, and pT181 during the overnight period in the sleep-deprived group compared with the control (A-E). The CSF/plasma albumin ratio, a marker of blood-CSF permeability, was decreased overnight during sleep deprivation (F). The overnight period during the intervention night was defined as hours 18 to 28 (21:00–11:00). Blue: control; Red: sleep-deprived; Error bars indicate standard error. The vertical dashed line is the intervention start time. The horizontal dashed line is at time 0. P-values are shown.

Table 3:

Mixed Model Results for Change in Overnight (21:00 – 11:00) CSF/Plasma Ratios of Aβ, Tau, Phosphorylated Tau, and Albumin from Baseline

| CSF/Plasma Ratios | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker | Factor | Pairwise Comparison | Mean Difference (95% CI) | F (df) | p |

| Aβ40, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +44.577 (34.058, 55.097) | 71.90 (1,59.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 2.48 (7,59.00) | 0.027 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.689 (7,59.00) | 0.681 | |||

| Aβ42, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +48.692 (35.615, 61.769) | 55.51 (1,59.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 1.27 (7,59.00) | 0.279 | |||

| Intervention x time | 1.00 (7,59.00) | 0.439 | |||

| T181, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +57.702 (39.331, 76.073) | 39.50 (1,59.01) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 1.99 (7,59.01) | 0.072 | |||

| Intervention x time | 1.02 (7,59.01) | 0.425 | |||

| T217, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +58.823 (43.968, 73.677) | 62.74 (1,60.00) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 2.10 (7,60.00) | 0.057 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.956 (7,60.00) | 0.472 | |||

| pT181, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | +81.160 (50.118, 112.203) | 27.37 (1,59.02) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 1.66 (7,59.02) | 0.138 | |||

| Intervention x time | 0.687 (7,59.02) | 0.683 | |||

| Albumin, % baseline | Intervention | Sleep-deprived vs. Control | −32.397 (−50.410, −14.384) | 12.97 (1,57.19) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | 0.718 (7,57.15) | 0.657 | |||

| Intervention x time | 1.24 (7,57.15) | 0.298 | |||

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; Aβ = amyloid-β; T181 = unphosphorylated tau-181; T217 = unphosphorylated tau-217; pT181 = phosphorylated tau-181; CI = confidence intervals; df = degrees of freedom

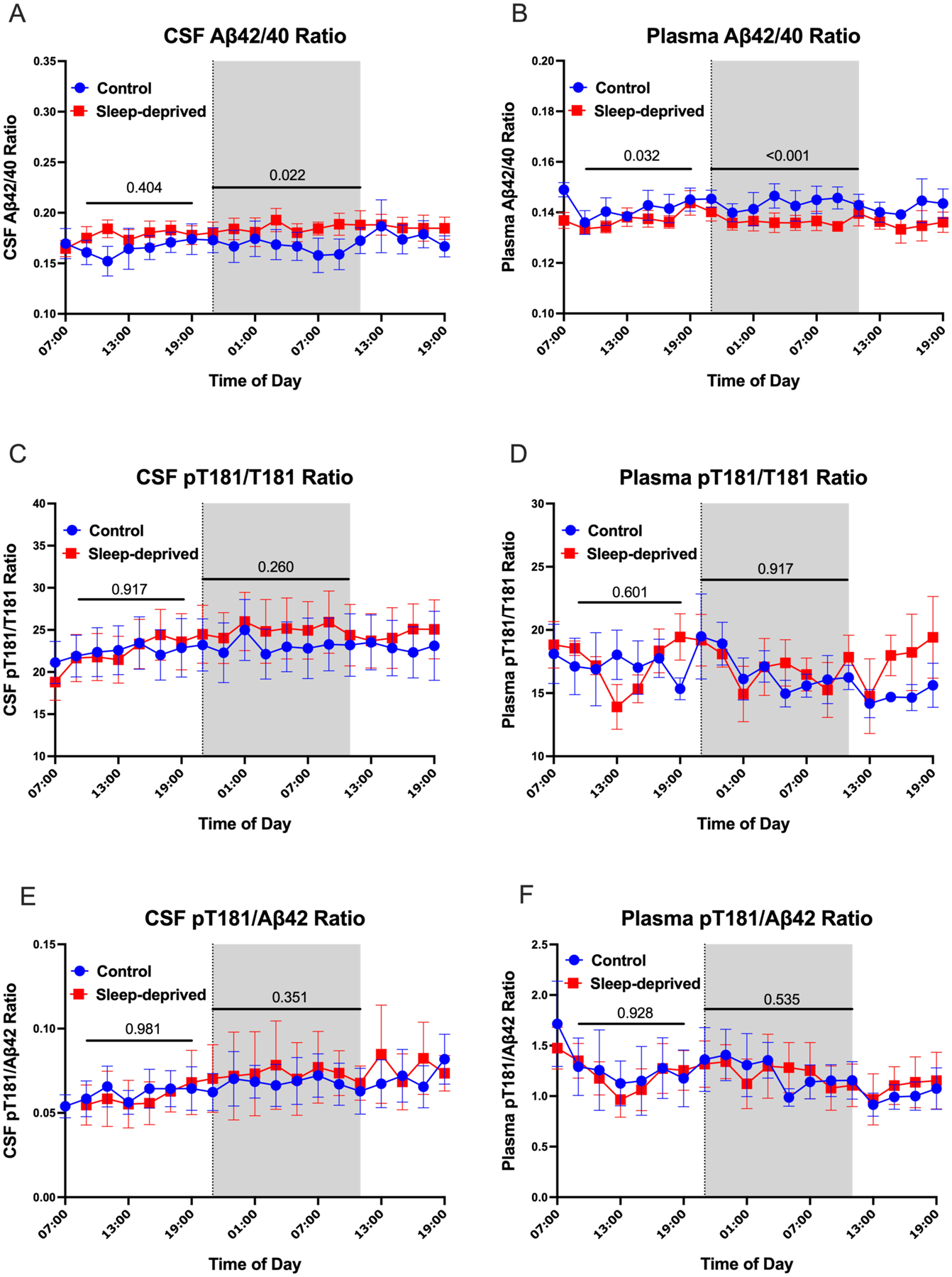

Although sleep loss decreased overnight levels of individual plasma AD biomarkers (Aβ40, T181, etc.) from baseline compared to controls, several recently validated plasma markers for amyloid deposition have used ratios rather than individual biomarker concentrations (e.g., Aβ42/40 ratio) [8, 9]. We found no mean group differences of the unadjusted biomarker ratios for pT181/T181 and pT181/Aβ42 in both plasma and CSF during the day (09:00–19:00) or overnight (01:00–11:00) periods. For Aβ42/40, however, the plasma ratio was significantly higher in the control condition during both the day and overnight periods but not in CSF (Figure 3A–F; Supplementary Tables 1–2). These findings do not support a sleep effect on plasma Aβ42/40 since the control condition is higher than during the sleep-deprived condition throughout the entire sampling period.

Figure 3:

No effect of sleep on Alzheimer’s disease biomarker ratios. Both daytime and overnight Aβ42/40 ratios were not significantly different between the sleep-deprived and control groups in CSF, but they did differ in plasma (A, B). The CSF Aβ42/40 ratio for one participant’s time course under the control condition was abnormally high compared to the same participant’s time course under the sleep-deprived condition and was excluded. Although plasma Aβ42/40 ratios were higher in the control group than the sleep-deprived group, there were no evidence of an effect from sleep loss. Both day and night ratios of pT181/T181 and pT181/ Aβ42 in CSF and plasma were not significantly different between groups (C-F). The overnight period during the intervention night was defined as hours 18 to 28 (21:00–11:00) (Shaded area). The day period was defined as 09:00 – 19:00. Blue: control; Red: sleep-deprived; Error bars indicate standard error. The vertical dashed line is the intervention start time. P-values are shown.

Our previous work defined the overnight period as 01:00–11:00 and we report the same analyses presented above with this overnight period in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Figure 1–3; Supplementary Tables 3–5).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that one night of sleep deprivation decreases the clearance of Aβ, tau, and p-tau from the central nervous system resulting in overnight concentrations that are higher in CSF and lower in blood. Overnight plasma Aβ, tau, and p-tau levels were ~5–15% lower in the sleep-deprived group compared to controls while CSF concentrations of these proteins were ~35–55% higher. Based on CSF Aβ stable isotope labeling kinetics (SILK) between the sleep-deprived and control participants, we previously concluded that changes in production rate were the necessary and critical factor for the increase in CSF Aβ levels. Although clearance effects alone did not account for this finding, clearance effects were not ruled out [14]. The CSF/blood ratios of Aβ, tau, p-tau, and albumin support that sleep loss disrupted transport between CSF and blood. However, the effect of sleep on production and clearance on Aβ, tau, and other metabolites needs further study and was not accounted for in our most recent models[24].

Substantial evidence supports that sleep loss decreases the clearance of substances from the central nervous system. For instance, one night of sleep deprivation after intrathecal injection of gadolinium resulted in decreased clearance of the tracer even after a night of recovery sleep [25]. Multiple pathways are involved in the clearance of substances from the brain including glymphatic flow, perivascular efflux, drainage via lymphatic vessels, and transport across the blood-brain barrier. Many of these pathways have been associated with sleep and Aβ clearance [26, 27]. In addition to these mechanisms, Aβ has been shown to efflux from the brain across the blood-CSF barrier via p-glycoprotein and lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1) transporters [28–32]. P-glycoprotein activity has been shown to change diurnally, but has not been associated with sleep [33]. How tau is cleared from the brain is less clear, but prior work suggested that exosomes [34], lymphatics [35], and glymphatic function [36] may be involved.

The concentrations of plasma-derived proteins in CSF depend on the plasma concentration, blood-CSF barrier permeability, and CSF flow or turnover [37]. Albumin enters CSF from blood across the blood-CSF barrier and is transported via binding glycoprotein receptors on epithelial cells in the choroid plexus [38]. Based on the CSF and plasma albumin concentrations as well as the CSF/plasma albumin index, we found that the influx of albumin from blood to CSF was impaired by sleep deprivation. This finding may be due to altered blood-CSF barrier function and/or altered CSF flow or turnover.

Plasma AD biomarkers are validated as highly sensitive and specific for in vivo amyloid status in humans [8, 9] and are being increasingly used in the clinic. However, potential factors that may affect their levels are not well-understood. Chronic kidney disease, for instance, was recently found to affect plasma phospho-tau concentrations [39]. In our study, sleep deprivation had inverse effects on CSF and plasma AD biomarkers raising concerns about how sleep may affect the diagnostic accuracy of plasma amyloid tests. Ratios of AD biomarkers, such as Aβ42/40 and pT181/T181, were not affected by sleep. Collecting blood and/or CSF for observational and interventional studies within a narrow range of time will also help minimize potential variance.

A limitation of our study is the small number of participants, however all participants repeated both intervention groups allowing for intra-individual comparisons of 190 total time points (19/participant/intervention). A major strength of this study is the paired CSF-plasma samples collected simultaneously under controlled sleep interventions for 36 hours. All participants were cognitively normal and biomarker negative for amyloid pathology [14], a major limitation that prevents the extension of our results to individuals with amyloid deposition, cognitive impairment, or medical comorbidities such as vascular disease or chronic kidney disease that may impair clearance from the brain or alter plasma AD biomarkers such as p-tau. Further, CSF to blood clearance varies between individuals in general and across neurological diseases [40]. This study adjusts for this limitation through intra-individual comparison, but it is unknown how CSF to blood clearance varies across time in individuals or is affected by sleep deprivation. Future studies are needed to clarify the impact of sleep deprivation on plasma AD biomarkers in different patient populations.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic Review:

The authors reviewed the literature using traditional (e.g., PubMed) sources and meeting abstracts and presentations. Although sleep deprivation increases cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ and tau levels, there have been several recent publications describing how sleep loss affects blood Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. These relevant citations are appropriately cited.

Interpretation:

Our findings showed opposite effects of sleep loss on CSF and blood AD biomarkers. Although individual AD biomarkers were affected, ratios of AD biomarkers (e.g., Aβ42/40) were not. We suggest a hypothesis that brain-CSF barrier function is affected by sleep loss.

Future Directions:

The manuscript proposes that sleep loss alters plasma AD biomarkers by disrupting brain clearance mechanisms and this effect needs to be taken into account when interpreting individual biomarkers. However, plasma AD biomarker ratios, such as Aβ42/40, were not affected by sleep loss. Future studies in larger cohorts are needed to confirm and extend these findings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for their time and commitment to the study. We thank Dr. Donald Elbert for helpful discussion. This study was funded by the Centene Corporation contract (P19-00559) for the Washington University-Centene ARCH Personalized Medicine Initiative. Additional support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH): R03 AG047999, K76 AG054863, P50 AG05681, and P01 AG26276 (National Institute on Aging); R01 NS065667 and R01 NS097799 (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke). The 15N- 441 tau internal standard was a generous gift from G. Lippens. Dr N. Kanaan generously provided the Tau1 antibody that is a tau epitope 192-199. HJ8.5 antibody to tau epitope 27-35 was generously given by Dr. David Holtzman. The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclosures

H.L., Y.H., S.L.C., B.A.: No disclosures.

N.R.B.: Washington University and R.J.B. have equity ownership interest in C2N Diagnostics and R.J.B. receives income from C2N Diagnostics for serving on the scientific advisory board. R.J.B. and N.R.B. may receive income based on technology (methods of diagnosing AD with phosphorylation changes) licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics.

V.O.: VO has submitted the US provisional patent application “Plasma Based Methods for Detecting CNS Amyloid Deposition” as co-inventors and may receive royalty income based on technology (stable isotope labeling kinetics and blood plasma assay) licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics

J.G.B.: JGB has submitted the US provisional patent application “Plasma Based Methods for Detecting CNS Amyloid Deposition” as co-inventors and may receive royalty income based on technology (stable isotope labeling kinetics and blood plasma assay) licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics.

R.J.B.: Washington University and RJB have equity ownership interest in C2N Diagnostics and receive income based on technology (blood plasma assay) licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics. RJB receives income from C2N Diagnostics for serving on the scientific advisory board. Washington University, with RJB as co-inventor, has submitted the US nonprovisional patent application “Plasma Based Methods for Determining A-Beta Amyloidosis.” RJB has received honoraria as a speaker/consultant/advisory board member from Amgen, Eisai, Hoffman-LaRoche, and Janssen; and reimbursement of travel expenses from, Hoffman-La Roche and Janssen.

B.P.L.: B.P.L. has received honoraria as a consultant/advisory board member/DSMB member from Eli Lilly and Beacon Biosignals.

Reference

- [1].Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee S-Y, Dence CS, Shah AR, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid-beta-42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:512–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fagan AM, Shaw LM, Xiong C, Vanderstichele H, Mintun MA, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Comparison of analytical platforms for cerebrospinal fluid measures of β-amyloid 1–42, total tau, and p-tau181 for identifying Alzheimer disease amyloid plaque pathology. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Shah AR, Aldea P, Roe CM, Mach RH, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau(181) increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:371–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:306–3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Choi SR, Golding G, Zhuang Z, Zhang W, Lim N, Hefti F, et al. Preclinical properties of 18F-AV-45: a PET agent for Abeta plaques in the brain. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1887–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ovod V, Ramsey KN, Mawuenyega KG, Bollinger JG, Hicks T, Schneider T, et al. Amyloid β concentrations and stable isotope labeling kinetics of human plasma specific to central nervous system amyloidosis. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:841–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schindler SE, Bollinger JG, Ovod V, Mawuenyega KG, Li Y, Gordon BA, et al. High-precision plasma beta-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology. 2019;93:e1647–e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Janelidze S, Teunissen CE, Zetterberg H, Allué JA, Sarasa L, Eichenlaub U, et al. Head-to-Head Comparison of 8 Plasma Amyloid-β 42/40 Assays in Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:1375–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li Y, Schindler SE, Bollinger JG, Ovod V, Mawuenyega KG, Weiner MW, et al. Validation of Plasma Amyloid-β 42/40 for Detecting Alzheimer Disease Amyloid Plaques. Neurology. 2021;98:e688–e99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Palmqvist S, Janelidze S, Quiroz YT, Zetterberg H, Lopera F, Stomrud E, et al. Discriminative Accuracy of Plasma Phospho-tau217 for Alzheimer Disease vs Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Huang Y, Potter R, Sigurdson W, Santacruz A, Shih S, Ju Y-E, et al. Effects of age and amyloid deposition on Aβ dynamics in the human central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:51–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Holth JK, Fritschi SK, Wang C, Pedersen NP, Cirrito JR, Finn MB, et al. The sleep-wake cycle regulates extracellular tau in mice and humans. Science. 2019;363:880–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lucey BP, Hicks TJ, McLeland JS, Toedebusch CD, Boyd J, Elbert DL, et al. Effect of sleep on overnight CSF amyloid-β kinetics. Ann Neurol. 2018;83:197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Barthélemy NR, Liu H, Lu W, Kotzbauer PT, Bateman RJ, Lucey BP. Sleep deprivation affects tau phosphorylation in human cerebrospinal fluid. Ann Neurol. 2020;87:700–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wei M, Zhao B, Huo K, Deng Y, Shang S, Liu J, et al. Sleep Deprivation Induced Plasma Amyloid-β Transport Disturbance in Healthy Young Adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Benedict C, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Cedernaes J. Effects of acute sleep loss on diurnal plasma dynamics of CNS health biomarkers in young men. Neurology. 2020;94:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Barthélemy NR, Mallipeddi N, Moiseyev P, Sato C, Bateman RJ. Tau phosphorylation rates measured by mass spectrometry differ in the intracellular brain vs. extracellular cerebrospinal fluid compartments and are differentially affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Barthélemy NR, Horie K, Sato C, Bateman RJ. Blood plasma phosphorylated-tau isoforms track CNS change in Alzheimer’s disease. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20200861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Barthélemy NR, Li Y, Joseph-Mathurin N, Gordon BA, Hassenstab J, Benzinger TL, et al. A soluble phosphorylated tau signature links tau, amyloid and the evolution of stages of dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2020;26:398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hedeker D Generalized linear mixed models. In: Everitt BS, Howell DC, editors. Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2005. p. 729–38. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tumani H, Hegen H. CSF Albumin: Albumin CSF/Serum Ratio (Marker for Blood-CSF Barrier Function). New York: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bowman GL, Kaye JA, Moore M, Waichunas D, Carlson NE, Quinn JF. Blood-brain barrier impairment in Alzheimer disease: stability and functional significance. Neurology. 2007;68:1809–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Elbert DL, Patterson BW, Lucey BP, Benzinger TLS, Bateman RJ. Importance of CSF-based Aβ clearance with age in humans increases with declining efficacy of blood-brain barrier/proteolytic pathways. Commun Biol. 2022;5:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Eide PK, Vinje V, Pripp AH, Mardal KA, Ringstad G. Sleep deprivation impairs molecular clearance from the human brain. Brain. 2021;144:863–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, Liao Y, Thiyagarajan M, et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. 2013;342:373–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hablitz LM, Plá V, Giannetto M, Vinitsky HS, Stæger FF, Metcalfe T, et al. Circadian control of brain glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lam FC, Liu R, Lu P, Shapiro AB, Renoir JM, Sharom FJ, et al. beta-Amyloid efflux mediated by p-glycoprotein. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cirrito JR, Deane R, Fagan AM, Spinner ML, Parsadanian M, Finn MB, et al. P-glycoprotein deficiency at the blood-brain barrier increases amyloid-beta deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3285–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Storck SE, Meister S, Nahrath J, Meißner JN, Schubert N, Di Spiezio A, et al. Endothelial LRP1 transports amyloid-β(1–42) across the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:123–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bruckmann S, Brenn A, Grube M, Niedrig K, Holtfreter S, von Bohlen und Halbach O, et al. Lack of P-glycoprotein Results in Impairment of Removal of Beta-Amyloid and Increased Intraparenchymal Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy after Active Immunization in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;14:656–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sweeney MD, Kisler K, Montagne A, Toga AW, Zlokovic BV. The role of brain vasculature in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1318–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kervezee L, Hartman R, van den Berg DJ, Shimizu S, Emoto-Yamamoto Y, Meijer JH, et al. Diurnal variation in P-glycoprotein-mediated transport and cerebrospinal fluid turnover in the brain. Aaps j. 2014;16:1029–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shi M, Kovac A, Korff A, Cook TJ, Ginghina C, Bullock KM, et al. CNS tau efflux via exosomes is likely increased in Parkinson’s disease but not in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:1125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Patel TK, Habimana-Griffin L, Gao X, Xu B, Achilefu S, Alitalo K, et al. Dural lymphatics regulate clearance of extracellular tau from the CNS. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ishida K, Yamada K, Nishiyama R, Hashimoto T, Nishida I, Abe Y, et al. Glymphatic system clears extracellular tau and protects from tau aggregation and neurodegeneration. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2022;219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Seyfert S, Faulstich A, Marx P. What determines the CSF concentrations of albumin and plasma-derived IgG? J Neurol Sci. 2004;219:31–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Liddelow SA, Dzięgielewska KM, Møllgård K, Whish SC, Noor NM, Wheaton BJ, et al. Cellular specificity of the blood-CSF barrier for albumin transfer across the choroid plexus epithelium. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mielke MM, Dage JL, Frank RD, Algeciras-Schimnich A, Knopman DS, Lowe VJ, et al. Performance of plasma phosphorylated tau 181 and 217 in the community. Nat Med. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hovd MH, Mariussen E, Uggerud H, Lashkarivand A, Christensen H, Ringstad G, et al. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of CSF to blood clearance: prospective tracer study of 161 patients under work-up for CSF disorders. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2022;19:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.