Summary

Junctional adhesion molecule-like protein (JAML) serves as a co-stimulatory molecule in γδ T cells. While it has recently been described as a cancer immunotherapy target in mice, its potential to cause toxicity, specific mode of action with regard to its cellular targets, and whether it can be targeted in humans remain unknown. Here, we show that JAML is induced by T cell receptor engagement, reveal that this induction is linked to cis-regulatory interactions between the CD3D and JAML gene loci. When compared to other immunotherapy targets plagued by low target specificity and end-organ toxicity, we find JAML to be mostly restricted to and highly expressed by tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells in multiple cancer types. By delineating the key cellular targets and functional consequences of agonistic anti-JAML therapy in a murine melanoma model, we uncover its specific mode of action and the reason for its synergistic effects with anti-PD-1.

Introduction

Immunotherapies targeting co-stimulatory or co-inhibitory receptors on T cells have become an important treatment option for a variety of cancer types and several molecules like TIM31, TIGIT2, GITR3, VISTA4, LAG35 or ICOS6 are currently being explored to evaluate their anti-tumor capacity. Crucially however, most of these targets suffer from ‘on-target/off-cell’ effects, as both effector and regulatory T cell subsets in tumor tissues can express high levels of these molecules. Accordingly, we have recently shown that intratumoral PD-1 expressing follicular regulatory T (TFR) cells are critical determinants of anti-PD-1 treatment efficacy, and that anti-PD-1 therapy can activate such suppressive cells, thus dampening treatment efficacy7. In line with this, it has been demonstrated that the balance of PD-1 expressing CD8+ T cells and T regulatory (TREG) cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) is a critical biomarker predicting anti-PD-1 treatment efficacy8. Furthermore, we9,10 and others11–13 have demonstrated the critical importance of CD8+ TRM cells for anti-tumor immunity in multiple cancer types, and, while they have also been shown as being specific for tumor antigens13, so far, immunotherapies that preferentially target TRM cells have not been described. These findings imply that expression levels of immunotherapy targets on different T cell subsets need to be carefully evaluated to determine which patients might benefit from a given treatment. Furthermore, while established immunotherapy drugs like anti-PD-1 or anti-CTLA-4 have shown remarkable success in some instances, only a fraction (~20%) of patients respond to treatment14. It is well appreciated that anti-CTLA-4/anti-PD-1 combination therapy results in significantly higher overall response rates compared to monotherapy with either agent, but that combination therapy also induces more frequent and severe immune-related adverse events (irAEs) due to ‘on-target/off-tumor’ effects on T cell present in normal tissues, thus limiting its use15. Because off-cell effects and widespread immune-related toxicity severely limit both treatment efficacy and combination therapy options, there is urgent need to develop novel immunotherapy targets that exhibit a more restricted expression profile.

JAML was initially identified as the major co-stimulatory molecule in epithelial γδ T cells, and activation by coxsackie and adenovirus receptor (CXADR), its ligand expressed by epithelial cells, has been shown to be important for tissue homeostasis and wound repair16,17. While JAML has an overall low sequence identity with the costimulatory molecule CD28 (~11%), their intracellular signaling motifs bear substantial similarities and, upon ligation, recruit phosphatidylinositol-3-OH-kinase (PI3K), leading to cell activation, proliferation and cytokine production16,17. Moreover, in mouse models, JAML has been implicated an appealing cancer immunotherapy target18.

However, its role and function in tumor-infiltrating human αβ T cells, especially TRM cells, remain unexplored. Here, we report that JAML functions as a co-stimulatory molecule in human αβ CD8+ T cells, and that its expression is increased by TCR signaling. Utilizing 3D chromatin interaction maps in human T cells, we demonstrate extensive interactions between the JAML promoter and the neighboring CD3D promoter region driving JAML expression in activated T cells, but not other cell compartments. Analysis of transcriptomes and protein expression data in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from multiple cancer types in humans show that JAML is highly expressed by CD8+ TRM cells and that JAML expression on CD8+ TRM cells is associated with better survival outcomes in a large cohort of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Finally, in a murine melanoma model, we confirmed restricted expression of JAML on CD8+ T cells in primary tumor tissue, but not other non-malignant organs. Crucially, we found JAML to be expressed on distinct ‘stem-like’ Tcf7hiPdcd1lo and cytotoxic Pdcd1hiTcf7lo CD8+ TIL subsets, that, together with our unbiased RNA sequencing data, uncover why anti-JAML acts synergistically with anti-PD-1 therapy to augment TIL infiltration and anti-tumor immunity.

Results

JAML is enriched in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRM cells of multiple cancer types

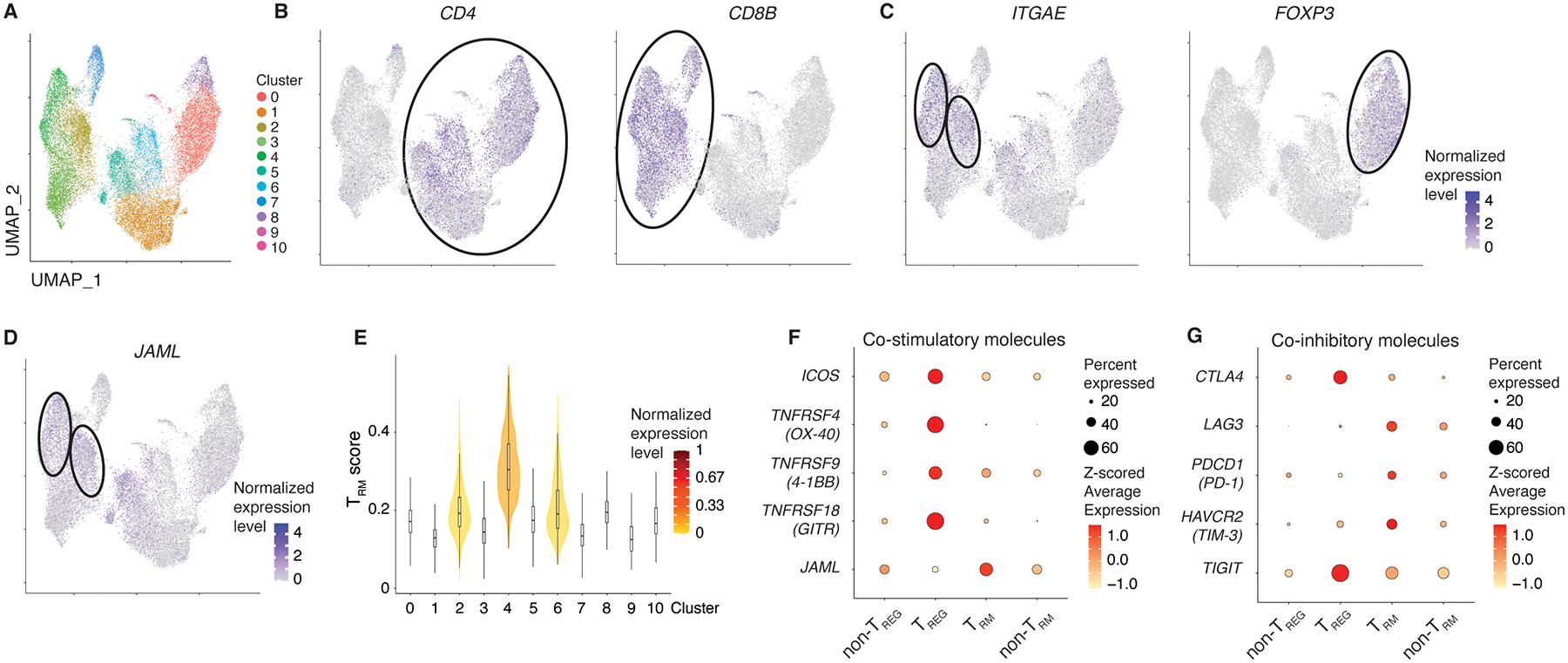

As few studies have thoroughly assessed the level and breadth of immunotherapy target expression in T cell subsets in the TME, we integrated and analyzed 9 published single-cell RNA-seq datasets of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (n=22,410 cells) spanning 7 different cancer types. Data visualization using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) revealed 10 distinct T cell subsets (Fig. 1A–C) that differed substantially in their expression of several co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory receptors (Fig. S1A). We verified that the main clusters weren’t dominated by cells from individual datasets; only clusters with few cells (9 and 10) seemed to divert from that trend (Fig. S1B). Given the opposing roles of CD4+FOXP3+ (TREG) cells and CD8+ TRM cells in anti-tumor immunity and immunotherapy efficacy (refs.7,9,12,19–23), we assessed the transcript expression levels of several immunotherapy targets in these major CD4+ (non-TREG and TREG) and CD8+ (TRM and non-TRM) T cell subsets and verified cell identify of TRM cells by utilizing a previously published tumor TRM gene signature10 (Fig. 1B–G). Importantly, TREG cells, when compared to the other T cell subsets, expressed higher levels of transcripts encoding for several co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory immunotherapy drug targets currently in clinical use or clinical trials (e.g., 4-1BB, ICOS, OX-40, GITR, TIGIT) (Fig. 1F,G), while some co-inhibitory receptors were expressed on all assessed T cell subsets (Fig. 1G). On the other hand, we found JAML transcripts to be expressed at relatively higher levels by CD8+ TRM cells when compared to TREG cells (Fig. 1F). Because co-stimulatory molecules enhance TCR-dependent cell activation, proliferation, and effector functions, we next tested whether JAML-expressing T cells exhibit transcriptional features of superior functionality when compared to their JAML-non-expressing counterparts. Notably, we found that JAML-expressing TRM cells expressed higher levels of transcripts encoding for cytotoxicity molecules (Granzyme B, Perforin) and effector cytokines (IFN-γ, CXCL13) when compared to TRM cells not expressing JAML (Fig. S1C), suggesting that JAML expression marks TRM cells with enhanced functional properties, or that JAML itself enhances functionality. Given that the expression pattern of co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory receptors was observed in many cancer types, we next verified immunotherapy target protein expression levels on tumor-infiltrating TREG and CD8+ T cells in patients with early stage and treatment naïve non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (Fig. S1D). These analyses corroborated our findings from single-cell RNA-seq data and confirmed that several immunotherapy target molecules are expressed at higher levels by tumor-infiltrating TREG cells.

Fig. 1. JAML is enriched in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRM cells of multiple cancer types.

A-C, Integrated analysis of nine published single-cell RNA-seq datasets from six different cancer types visualized by UMAP depicting CD4 and CD8 T cells (A). Seurat-normalized expression of CD4 (B, left), CD8B (B, right), ITGAE (C, left), FOXP3 (C, right) and JAML (D) in the different clusters. E, Identification of TRM clusters utilizing a previously published intratumoral TRM gene signature. F,G, Average transcript expression (color) and percentage (size) for selected co-stimulatory (F) and co-inhibitory (G) molecules in non-TREG, TREG, TRM and non-TRM cells for integrated analysis (A-D).

Together, these data suggest that immune suppressive TREG cells can get activated by agonistic antibodies targeting co-stimulatory molecules or by antibodies blocking co-inhibitory molecules, thus dampening their treatment efficacy. Conversely, JAML is primarily expressed by CD8+ TRM cells, implying that agonistic anti-JAML antibodies would preferentially activate CD8+ TRM cells with superior functionality and thus augment anti-tumor immunity.

JAML expression on TRM cells is associated with improved survival outcomes

Based on these data and given that we found that JAML is primarily expressed on highly functional TRM cells in tumor tissues10, we reasoned that expression of JAML in TRM cells may positively influence their anti-tumor activity and thus survival outcomes, and examined such association in a large cohort of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) (n=194). As expected, we found that a greater proportion of CD8+ TRM cells expressed JAML when compared to CD8+ non-TRM cells (Fig. 2A,B). Consistent with previous reports in NSCLC9 or early-stage triple negative breast cancer11, we demonstrate that intratumoral density of CD8+ TRM cells is significantly associated with improved patient survival (Fig. 2C). Moreover, HNSCC patients with higher proportions of JAML-expressing CD8+ TRM cells in the tumor had significantly better long-term overall survival outcomes when compared to those with lower proportions of JAML-expressing TRM cells (JAMLlow TRM tumors) (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that expression of JAML is likely to confer TRM cells with enhanced anti-tumor activity.

Fig. 2. JAML expression on TRM cells is associated with patient survival.

A, Whole-slide multiplexed immunohistochemistry analysis of selected markers from a treatment-naïve patient with NSCLC. B, Whole-slide multiplexed immunohistochemistry analysis depicting the percentage of JAML-expressing CD8+ TRM (CD8+CD103+) and CD8+ non-TRM (CD8+CD103−) cells in the cohort of HNSCC patients. C,D, Survival curves of a HNSCC cohort (n=194) stratified into TRMhi and TRMlo (C), JAMLhi and JAMLlo TRM cells (D). All data are mean +/− S.E.M. Significance for comparisons was computed using two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (B) or Mantel-Cox test (C,D), P = 0.1234; *P = 0.0332; **P = 0.0021; ***P = 0.0002; and ****P < 0.0001.

JAML functions as a co-stimulatory signal in human αβ T cells

As previous studies implied that JAML might not function as a co-stimulatory molecule in αβ T cells16,17, we tested whether ligand binding to JAML triggers activation of human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. At a sub-optimal concentration (0.5μg/ml) of anti-CD3, which by itself did not induce cell activation (Fig. S2A), JAML ligation by its endogenous ligand CXADR led to rapid and dose-dependent upregulation of the early activation markers CD69, CD25, PD-1 and 4-1BB (Fig. S2B) and cell proliferation (Fig. S2C). Even at low concentrations, we found that JAML, like the co-stimulatory molecule CD28, potently activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. S2B). To confirm that CXADR activates T cells through ligation of JAML, we knocked down JAML expression in primary human CD8+ T cells utilizing Crispr-Cas9 and assessed co-stimulatory effects of CXADR. Transfection of CD8+ T cells with a JAML guide RNA altered the nucleotide sequence in the targeted JAML gene region (Exon 2), presumably driven by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated insertion or deletion events (Fig. S3A), significantly diminished JAML expression (Fig. S3B) and reduced T cell activation and cytokine secretion by CXADR co-stimulation (Fig. S3C,D). Contrary to the previous report17, these data demonstrate that JAML facilitates potent co-simulation in αβ T cells.

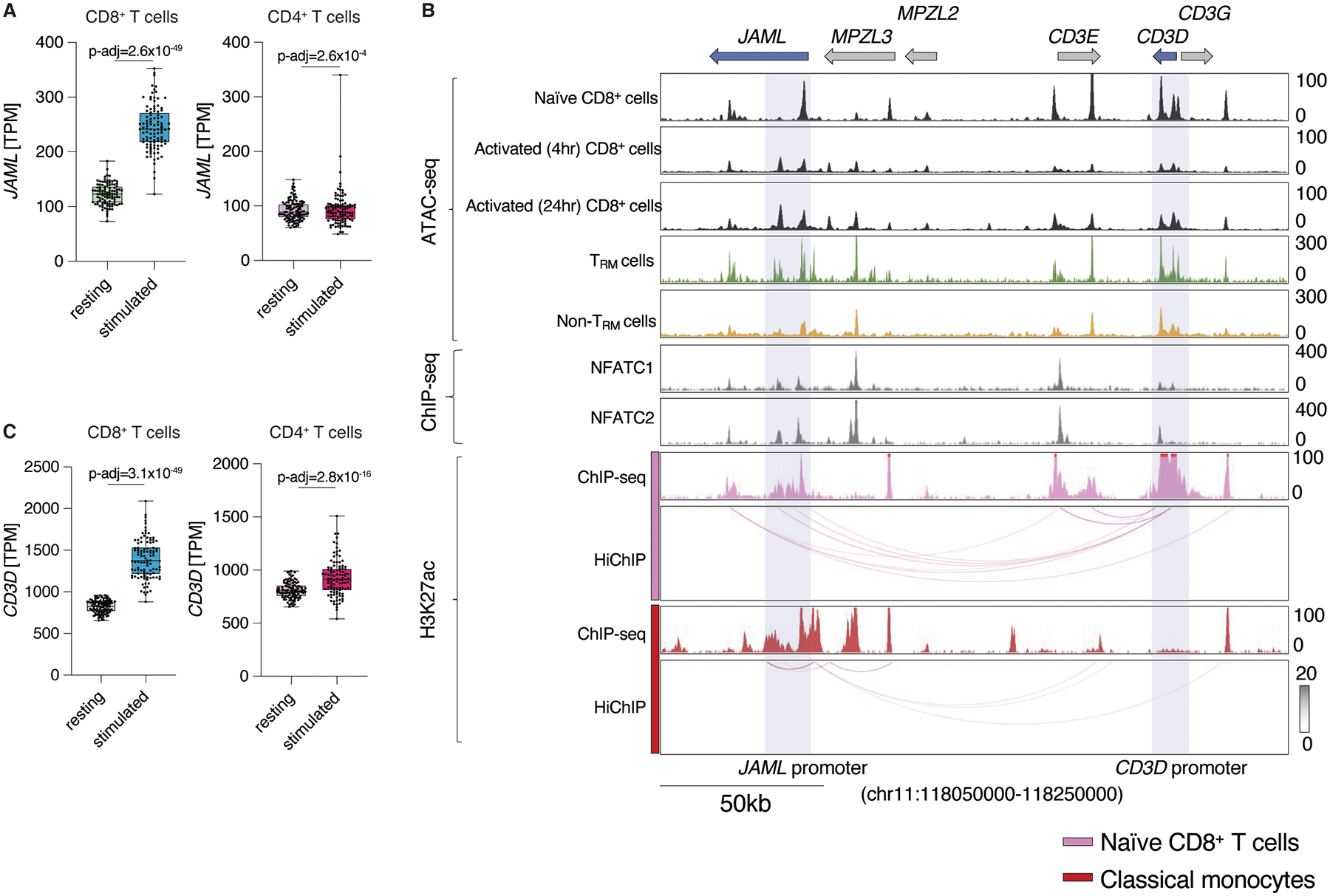

JAML expression is regulated by interactions between the CD3D and JAML promoters

Utilizing our previously published dataset24, we found that TCR stimulation more significantly increased JAML expression in human CD8+ T cells compared to CD4+ T cells (log2 fold change 1.24 versus 0.37 in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively; Fig. 3A). To investigate how TCR signaling induces JAML expression in αβ T cells, we first examined transposase accessible regions (ATAC-seq peaks) in the JAML locus in resting and stimulated human CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4A). Activation induced a strong ATAC-seq peak in the JAML intronic region (Fig. 3B) that also contained binding sites for NFAT, a key transcription factor involved in activation of genes following TCR activation. Notably, human tumor-infiltrating TRM cells displayed greater accessibility at the JAML promoter and the pertaining activation-induced intronic ATAC-seq peak region when compared to non-TRM cells. We also found several NFAT binding sites in the promoter regions of upstream genes like CD3D and CD3G which encode for key components of the TCR, and which like JAML, showed increased expression following activation (Fig. 3B). Importantly, by examining the 3D chromatin interaction map of the extended JAML locus in primary human T cells25, we found that the JAML promoter and the activation-induced intronic cis-regulatory region strongly interacted with the neighboring CD3D promoter region (Fig. 3B), suggesting that they are likely to be involved in regulating JAML expression. Accordingly, we found minimal interactions between these gene loci in other immune cell types (i.e., B cells or monocytes) that lack active CD3D promoter regions, indicative of a T cell-specific cis-regulatory control of JAML expression (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4A). As we have previously demonstrated that promoter-promoter interactions play a major role in regulating gene expression25, our data imply that the respective promoter regions of CD3D on the one hand, and JAML on the other hand, may act as reciprocal enhancers inducing each other’s expression. TCR signaling is likely to increase NFAT binding and thus the transcriptional activity of the CD3D promoter, thus driving its own expression (Fig. 3C) and with it, the expression of JAML through long-range cis-regulatory interactions. Together, these data demonstrate how and why JAML expression is induced in human T cells by TCR engagement and implies a T cell-specific inducible expression profile of this co-stimulatory molecule. Crucially and in line with our previous study10, these findings suggest that JAML expression might also be enriched in highly functional antigen-specific CD8+ TRM cells (i.e., reactive to tumor associated-antigens or neoantigens) driven by TCR-specific antigen-recognition and subsequent upregulation of JAML expression.

Fig. 3. JAML expression is induced by cis-regulatory interactions between the CD3D and JAML promoters.

A, JAML expression (TPM) in resting and anti-CD3 and anti-CD28-stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from donors (n=104) from a published bulk RNA-seq dataset24. B, ATAC-seq, ChIP–seq tracks and HiChIP interactions for the extended JAML and CD3 gene loci in indicated cell populations, the black arrow indicates the activation-induced intronic region. C, CD3D expression (TPM) in resting and anti-CD3 and anti-CD28-stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from donors (n=104) from a published bulk RNA-seq dataset24.

Murine CD8+ TILs selectively express high levels of JAML

We next assessed whether our findings in human T cells are also applicable to murine T cells. Similar to human αβ T cells, we found that TCR-signaling rapidly upregulated JAML expression on murine αβ CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4A). Upon co-stimulation with an agonistic anti-JAML antibody17 and anti-CD3, we observed a substantial upregulation of surface activation markers, confirming that JAML can function as a co-stimulatory molecule even in murine αβ T cells, a finding replicated in a recent study18 (Fig. 4B and Fig. S5A,B). Importantly, stronger TCR stimulation resulted in higher expression of JAML and thus required a ~10-fold lower concentration of agonistic anti-JAML antibody to activate CD8+ T cells even more strongly (Fig. 4C), implying that high avidity T cells (i.e., tumor antigen-reactive CD8+ T cells) expressing high levels of JAML, are likely to be highly sensitive to agonistic anti-JAML antibody treatment, even at relatively low concentrations. These results supported the rationale for testing the co-stimulatory function of JAML in vivo, especially in the context of tumor models, to determine if JAML could be utilized as a cancer immunotherapy target that potentially surpasses treatment efficacy of current immunotherapy drugs due to its low expression on immunosuppressive TREG cells. We tested this hypothesis in a murine melanoma model that is refractory to anti-PD-1 therapy. Given that short-term s.c. syngeneic tumor models do not induce robust anti-tumor CD8+ TRM responses23, we first assessed JAML expression levels on CD4+ (TREG and non-TREG) and CD8+ TILs of B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing mice. Consistent with our observations in human TILs, JAML was expressed at significantly higher levels in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells when compared to tumor-infiltrating TREG cells and CD4+ non-TREG cells (Fig. 4D), implying that treatment with agonistic JAML antibodies should preferentially activate CD8+ T cells over immunosuppressive TREG cells and thus enhance anti-tumor immune responses. Importantly, we found relatively low expression of JAML in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells present in spleen, colon and liver of tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 4E–G), suggesting that therapies activating JAML are likely to act primarily on CD8+ T cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME) and might therefore exert a favorable safety profile by not engaging T cells at common sites of immune-related toxicity. We further corroborated that notion by assessing the expression of JAML on bona-fide small intestine intra-epithelial (siIEL) and lamina propria (LPL) TRM cells, demonstrating that these cells do not express JAML under steady-state conditions (Fig. S5C).

Fig. 4. JAML is highly expressed by CD8+ TILs in a murine melanoma model.

A, Representative histogram plots of in vitro stimulated CD8+ T cells showing the expression levels of JAML in CD8+ T cells treated as indicated. B,C, Flow-cytometric analysis of murine CD8+ T cells stimulated with 0.1μg/ml anti-CD3 + indicated concentrations of anti-JAML (B), or 0.5μg/ml anti-CD3 + indicated concentrations of anti-JAML (C), depicted is the expression of early activation markers CD69, CD25, PD-1 and 4-1BB, results for n=2 technical replicates are shown. D-G, Mice were subcutaneously inoculated with B16F10-OVA cells in the right flank. Flow-cytometric analysis and representative histogram plots of the MFI of JAML in T cell populations in indicated organs at d18 after tumor inoculation (n=6 mice/group), (tumor, P<0.0001 for CD4+ non-TREG vs CD8+, P<0.0001 for CD4+ TREG vs CD8+; spleen, P<0.0001 for CD4+ non-TREG vs CD8+, P<0.0001 for CD4+ TREG vs CD8+; colon, P=0.0002 for CD4+ non-TREG vs CD8+, P<0.0001 for CD4+ TREG vs CD8+). Data are mean +/− S.E.M and are representative of at least 2 independent experiments. Significance for comparisons (D-G) was computed using one-way ANOVA comparing the mean of each group with the mean of the other groups followed by Tukey’s test; P = 0.1234; *P = 0.0332; **P = 0.0021; ***P = 0.0002; and ****P < 0.0001.

‘Stem-like’ CD8+ TILs express JAML.

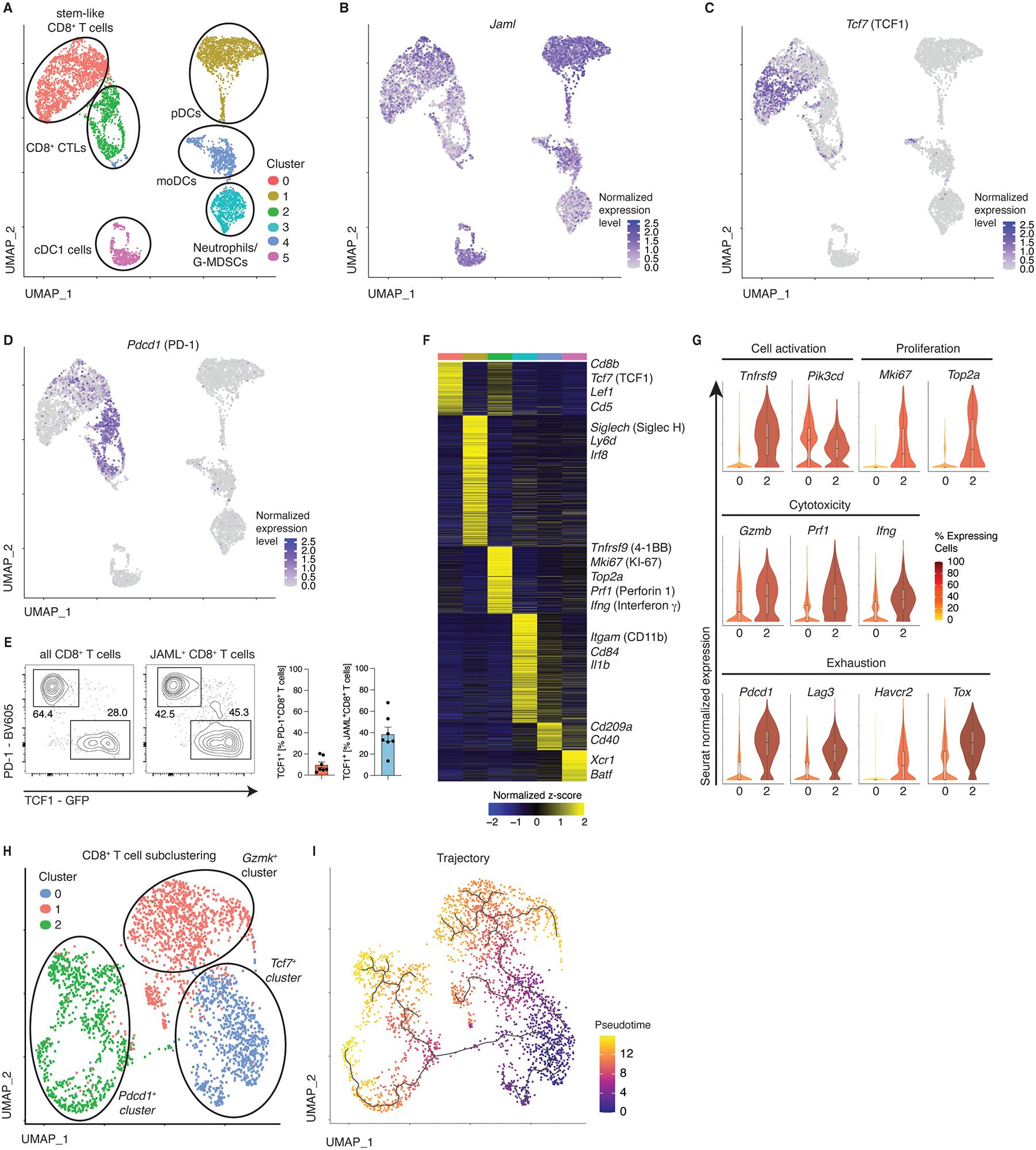

To determine the properties of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cell subsets that express JAML and to explore the other immune cell types that express JAML in an unbiased manner, we performed single-cell RNA-sequencing of JAML-expressing CD45+ cells present in primary late-stage tumor tissue of 3 individual B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing mice (Fig. S5D). Unbiased clustering depicted by UMAP analysis revealed 6 clusters, and importantly, substantiated that JAML expression in the T cell compartment is restricted to CD8+ TILs (cluster 0,2; Fig. 5A). The JAML-expressing CD8+ TILs (Fig. 5B) clustered into two distinct subsets that displayed striking differences in the expression of transcripts encoding for TCF1 (Tcf7) and PD-1 (Pdcd1) (Fig. 5C,D). We corroborated these data on the protein level, demonstrating that only a small proportion of TCF1-expressing CD8+ T cells co-expressed PD-1 (Fig. 5E), implying that anti-PD-1 treatment does not activate stem-like CD8+ T cells in the TME. Conversely, we found similar ratios of JAML-expressing CD8+ T expressing PD-1 or TCF1 (Fig. 5E), suggesting that anti-JAML treatment might induce a sustained anti-tumor immune response as it would activate both stem-like and effector CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, JAML-expressing and PD-1 expressing CD8+ T cells also expressed high levels of CX3CR1, but not KLRG1 (Fig. S5E), implying that such cells are a mixture of TCM, TEM and stem-like T cells. The Pdcd1-low cluster (cluster 0) expressed high levels of molecules linked to ‘stem-like’ properties (i.e., Tcf7, Lef1, Cd5), which have been shown to be important for sustaining anti-viral and anti-tumor immune responses26–28 (Fig. 5F,G). In contrast, the Pdcd1-enriched CD8+ T cell cluster (cluster 2), when compared to cluster 0 CD8+ T cells, displayed significantly higher expression of several transcripts linked to T cell activation (Tnfrsf9, Pik3cd), cytotoxicity (Gzmb, Prf1, Ifng) and cell proliferation (Mki67, Top2a), which suggested recent TCR activation by antigen-encounter, presumably directed to tumor antigens. The Pdcd1-enriched cluster also expressed high levels of other transcripts linked to exhaustion (Lag3, Havcr2, Tox) (Fig. 5B–G), and in agreement with previous studies29,30, these results indicate that expression of these exhaustion-like markers in murine TILs is unlikely to impede their functionality. Instead, it appears that expression of these molecules is a necessary adaptation to survive in the TME31 and to potentially limit immunopathology32, and likely marks effector T cells potentially responding to tumor antigens. Thus, these CD8+ T cells by virtue of co-expressing both PD-1 and JAML are likely to be activated by both agonistic anti-JAML antibodies and anti-PD1 therapies, and, importantly, when these therapies are combined, synergistic activation and enhanced anti-tumor responses are likely. Whereas, JAML-expressing PD-1− cells, which comprise stem-like T cells, are likely to be preferentially activated by agonistic anti-JAML antibodies when compared to anti-PD1 therapies. Sub-clustering of the Jaml-expressing CD8+ T cell clusters combined with trajectory analyses revealed 3 distinct populations (2 effector-like clusters and 1 stem-like cluster) and a developmental path originating from the stem-like Tcf7-expressing population, implying that these cells sustain the intratumoral effector pool (Fig. 5H,I).

Fig. 5. JAML is expressed by distinct CD8+ TILs.

A,B, Analysis of 10x single-cell RNA-seq data visualized by UMAP. Seurat clustering of tumor-infiltrating CD45+JAML+ cells in the B16F10-OVA model at d18 after tumor inoculation (A), B-D, Seurat-normalized expression of Jaml (B), Tcf7 (C) and Pdcd1 (D). E, Flow-cytometric analysis of CD8+ TILs (as in A) expressing the indicated markers. F, Heatmap depicting genes enriched in the identified clusters. Shown are significantly differentially expressed transcripts (Log2 FC>0.25 and adjusted P-value <0.05). G, Violin plots showing Seurat-normalized expression levels of the indicated markers in cells from cluster 0 and cluster 2. H, Sub-clustering of Cd8-expressing TIL subsets from (A). I, Single-cell pseudotime trajectory analysis of the subclustered CD8+ TILs (H) constructed using the Monocle3 algorithm.

Although, other lymphocyte subsets like TREG were not represented in JAML-expressing immune cells, we found several dendritic cell subsets expressed JAML (clusters 1,4,5) and corroborated previous reports of JAML-expressing neutrophils or granulocyte-derived myeloid-derived suppressor cells MDSCs (cluster 3)33,34, (Fig. 5A,B,F) in the TME. This result suggests that therapies targeting JAML may have ‘on-target/off-cell’ effects on JAML-expressing myeloid and dendritic cell compartments, but whether JAML agonistic antibodies modulate the functional activity of such cells remains to be explored. Conversely, anti-JAML antibodies are unlikely to elicit ‘on-target/off-tumor’ effects, as T cells in other non-malignant organs lack substantial expression of JAML, and are thus unlikely to cause end-organ toxicity.

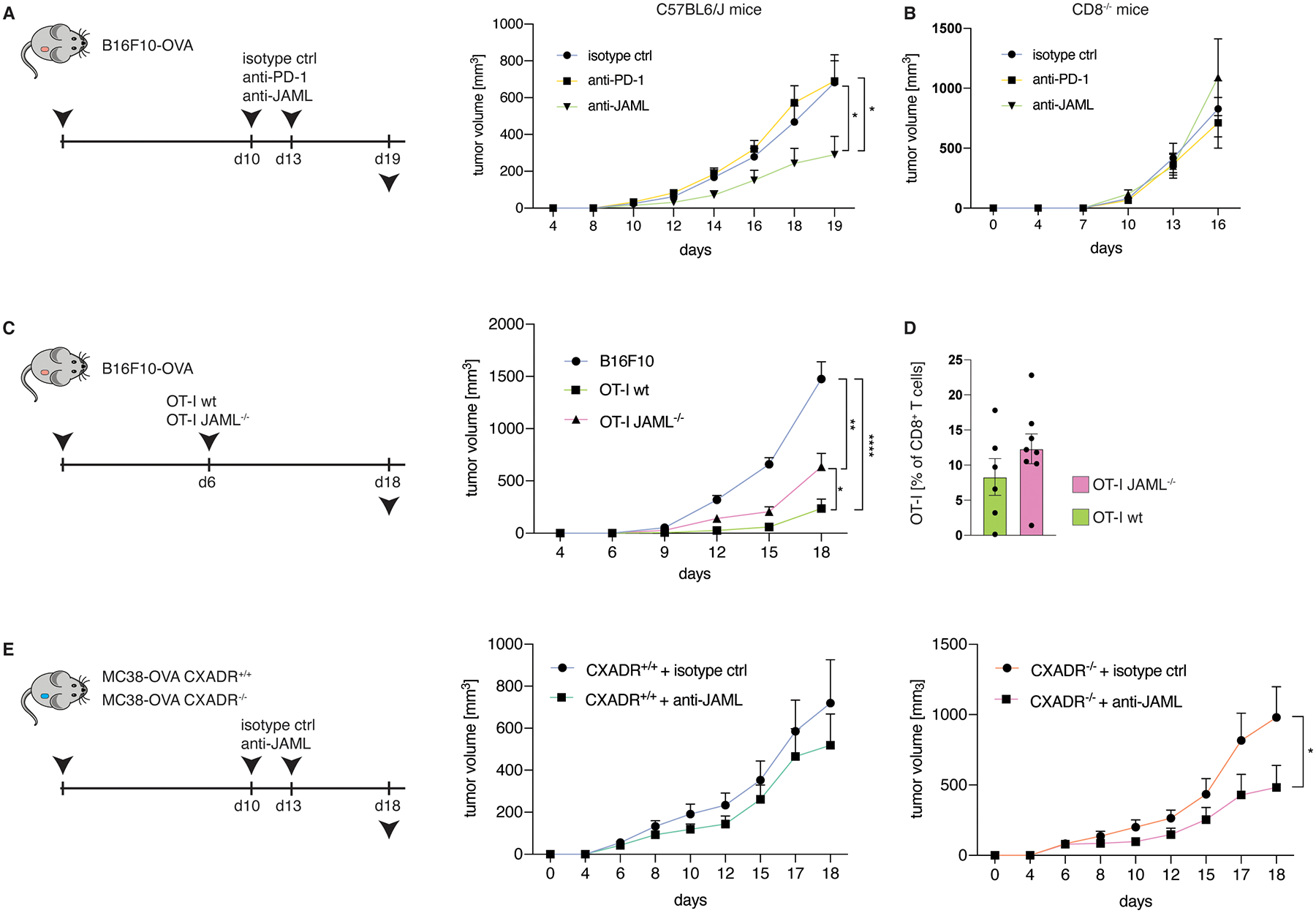

The anti-tumor effects of anti-JAML depend on CD8+ TILs

In line with previous studies35, we found no changes in tumor volume upon anti-PD-1 monotherapy in the B16F10-OVA tumor model (Fig. 6A). Conversely, treatment with agonistic anti-JAML antibodies significantly reduced tumor volume in B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing wildtype (Fig. 6A), but not CD8−/− mice (Fig. 6B), implying that the observed effects are likely dependent on CD8+ T cells. Accordingly, while adoptive transfer of OVA antigen-specific JAML-sufficient OT-I CD8+ T cells (OT-I JAMLwt) decreased tumor growth, Crispr-Cas9-mediated depletion of JAML on transferred OT-I CD8+ T cells (OT-I JAML−/−) reduced tumor control (Fig. 6C and Fig. S6a). Given that the frequencies of JAML-sufficient and JAML-deficient OT-I T cells in tumor tissues were comparable (Fig. 6D), it is unlikely that the observed differences in tumor control can be contributed to distinct migration tendencies or altered in vivo persistence. These data imply that CXADR (endogenous JAML ligand) might be expressed by cells in the TME, as JAML-expressing, but not JAML-deficient OT-I T cells, controlled tumor growth. Interestingly, we found that B16F10 melanoma cells expressed CXADR, albeit at profoundly lower levels when compared to MC38 adenocarcinoma cells (Fig. S6B), implying that tumor cells might provide co-stimulation to JAML-expressing TILs. To test this hypothesis, we utilized CRISPR-Cas9 to generate CXADR-deficient MC38-OVA cells (Fig. S6C) and performed an in vitro proliferation assay co-culturing either CXADR-sufficient or CXADR-deficient MC38-OVA tumor cells with CD8+ OT-I T cells. Notably, we found significantly less proliferation of CD8+ OT-I T cells when they were co-cultured with CXADR−/− MC38-OVA tumor cells (Fig. S6D), implying that tumor cells can provide co-stimulatory signals to CD8+ TILs via CXADR. As we observed that agonistic anti-JAML antibody treatment decreased tumor growth in B16F10-OVA melanoma cells but not MC38-OVA tumor cells (Fig. 6A,E), we reasoned that the disparate CXADR expression levels might be a critical determinant of anti-JAML treatment efficacy. To assess this hypothesis, we inoculated mice with either CXADR+/+ or CXADR−/− MC38-OVA cells and found that anti-JAML therapy was more effective in CXADR−/− MC38-OVA treated mice (Fig. 6E), implying that tumor cells themselves trigger TIL activation via JAML. Utilizing TCGA data, we verified the relatively lower expression of CXADR on melanoma samples when compared to other tumors of epithelial origins like esophageal, colonic and lung cancer (Fig. S6E), pointing to a possible immune evasion mechanism in melanoma and highlighting the potential benefit of agonistic anti-JAML antibody treatment specifically in human cancers expressing low levels of CXADR. Accordingly, CXADR expression on tumor cells might be utilized as an effective biomarker to predict efficacy of anti-JAML treatment efficacy.

Fig. 6. Agonistic JAML antibody treatment impedes tumor growth.

A,B, Tumor volume of C57BL/6J (a, n=10 mice for isotype control group and n=9 for anti-PD-1 and anti-JAML groups, P=0.0141 for isotype control vs anti-JAML and P=0.0227 for anti-PD-1 vs anti-JAML) or CD8−/− (B, n=7 mice/group for isotype control and anti-JAML and n=6 mice/group for anti-PD-1) mice s.c. inoculated with B16F10-OVA cells and treated with isotype control antibodies, anti-PD-1 antibodies or anti-JAML antibodies at indicated time points. C,D, Tumor volume (c, P<0.0001 for B16F10 vs OT-Iwt, P=0.0014 for B16F10 vs OT-I JAML−/−, P=0.033 for OT-Iwt vs OT-I JAML−/−) (n=13 mice/group for the control group, n=8 mice/group for OT-Iwt and n=10 mice/group for OT-I JAML−/−), and frequencies of tumor-infiltrating OT-I T cells (D, n=6 mice/group for OT-Iwt and n=8 mice/group for OT-I JAML−/−) of mice s.c. inoculated with B16F10-OVA cells and treated with 1×106 adoptively transferred wildtype OT-I T cells or JAML−/− OT-I T cells at day 6 after tumor inoculation. E, Tumor volume of mice s.c. inoculated with CXADR+/+ or CXADR−/− MC38-OVA cells and treated with either isotype control antibodies or anti-JAML antibodies at indicated time points (n=8 mice/group for CXADR+/+ + isotype control and n=7 mice/group for CXADR+/+ + anti-JAML, P=0.61; n=8 mice/group for CXADR−/− + isotype control and n=7 mice/group for CXADR−/− + anti-JAML, P=0.041). All data are mean +/− S.E.M and are representative of at least 2 independent experiments. Significance for comparisons was computed using two-tailed Mann-Whitney test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001.

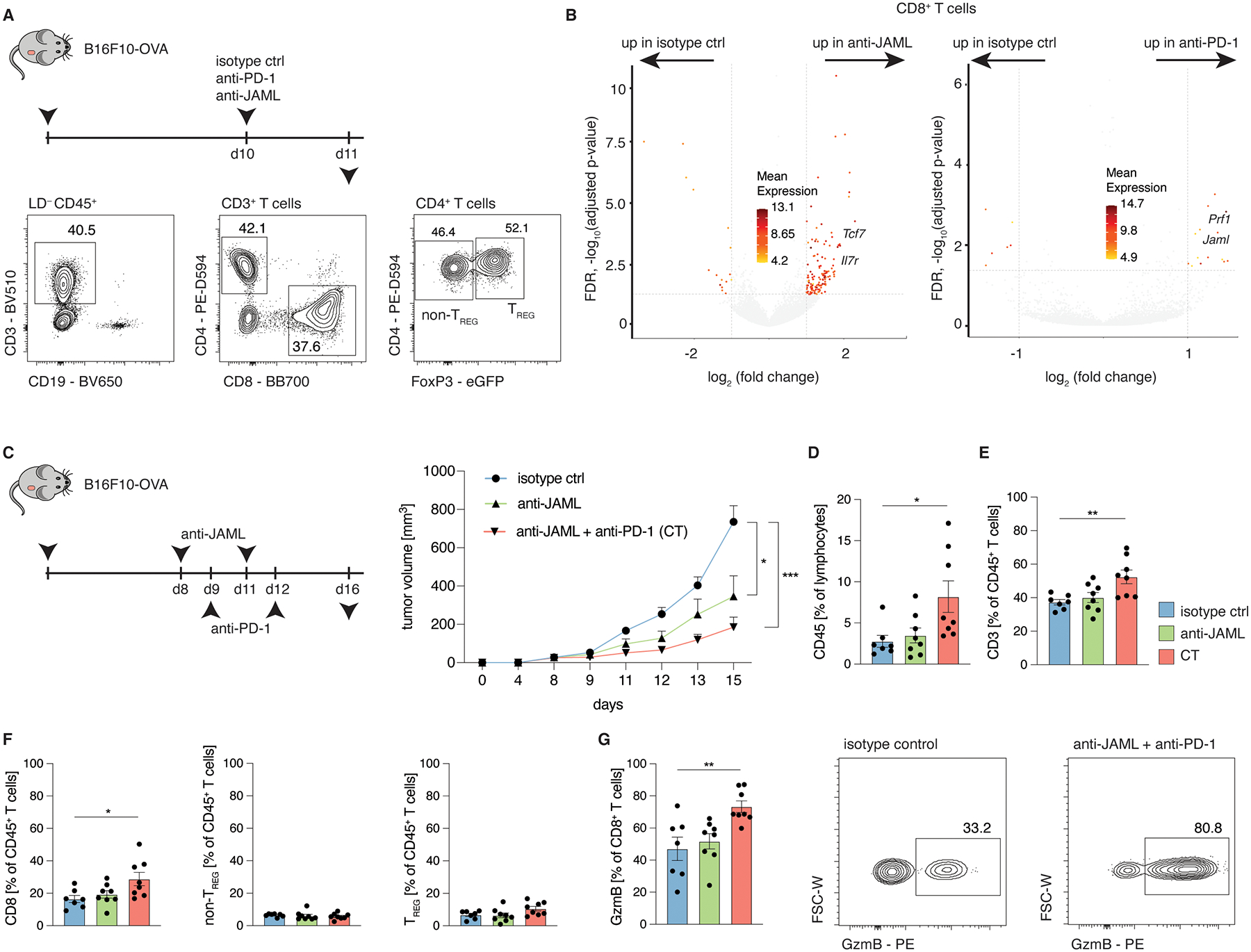

Synergistic anti-tumor effects in combination therapy with anti-PD-1 and anti-JAML

To elucidate molecular pathways selectively influenced by JAML signaling and to delineate the responsiveness of distinct TIL subsets to agonistic anti-JAML antibody and anti-PD1 treatment in vivo, we performed RNA-seq analyses of sorted tumor-infiltrating CD4+ TREG and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 7A). Pair-wise comparison of the bulk transcriptomes of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in treatment conditions versus isotype control showed that a greater number of genes were differentially expressed (DEG) in mice receiving agonistic anti-JAML therapy compared to anti-PD-1 therapy (151 versus 22 DEGs), and the converse was observed in tumor-infiltrating TREG (45 versus 342 DEGs), (Fig. 7B and Fig. S7A). In line with our previous study7, we found that anti-PD-1 therapy can activate suppressive TREG cells, as evidenced by upregulation of several transcripts linked to functionality (Prf1, Lag3) and proliferation (Mki67, Top2a), while anti-JAML does not (Fig. S7A).

Fig. 7. Anti-JAML synergizes with anti-PD-1 therapy.

Mice were subcutaneously inoculated with B16F10-OVA cells or MC38-OVA in the right flank and treated with either isotype control antibodies, anti-PD-1 antibodies or anti-JAML antibodies at indicated time points. A, Representative histogram plots depicting the gating strategy for CD4+ TREG cells, CD4+ non-TREG cells and CD8+ T cells. B, Volcano plot of isotype control vs anti-JAML (left) and isotype control vs anti-PD-1 (right) depicting differentially expressed transcripts (Log2 FC>1 and adjusted P-value <0.05). C-G, Tumor volume (C, n=7 mice/group for isotype control, n=8 mice/group for anti-JAML and CT; P=0.0225 for isotype control vs anti-JAML; P=0.0006 for isotype control vs CT), frequencies (D-G; P=0.0192 (D), P=0.0063 (E), P=0.0211 (F), P=0.0044 (G)) and representative contour plots of indicated cell populations of B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing mice treated as indicated as in (C). Data (C-G) are mean +/− S.E.M and are representative of at least 2 independent experiments. Significance for comparisons was computed using one-way ANOVA comparing the mean of each group with the mean of the control group (isotype control) followed by Dunnett’s test; P = 0.1234; *P = 0.0332; **P = 0.0021; ***P = 0.0002; and ****P < 0.0001.

These findings confirmed that unlike anti-PD-1 therapies, agonistic anti-JAML antibodies preferentially target CD8+ TILs over immune suppressive TREG cells due to its restricted expression profile (Fig. 7C). Importantly, anti-JAML treatment significantly increased the expression levels of genes (i.e., Tcf7, Il7r) shown to play a role in supporting ‘stem-like’ properties of T cells26–28, implying that anti-JAML therapy might either maintain or reinforce the ‘stem-like’ phenotype in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (Fig. 7B). This result supports our hypothesis, generated from single-cell transcriptomic analysis of JAML-expressing CD8+ TILs (Fig. 5A–G), that ‘stem-like’ TILs are likely to be more responsive to agonistic anti-JAML antibodies when compared to anti-PD1 therapy.

Moreover, 2 of the most upregulated transcripts in CD8+ T cells by anti-PD-1 therapy were Prf1, encoding for Perforin, and interestingly, Jaml (Fig. 7B), indicative of an interconnected pathway between PD-1 signaling, which restricts TCR signaling and CD28 co-stimulation36,37, and JAML expression, which we found to be induced by TCR signaling. Thus, we hypothesize that releasing TCR restriction with anti-PD-1 antibodies, upregulates the expression JAML on CD8+ T cells, which can then be targeted by agonistic anti-JAML antibodies, causing a further and selective activation of (tumor antigen-specific) CD8+ TILs. Based on these findings and given that anti-JAML agonistic antibody seems to reinforce a ‘stem-like’ phenotype and as multiple studies have identified TSCM cells as pivotal mediators of anti-PD-1 treatment efficacy26–28, we hypothesized that combination therapy (anti-JAML+anti-PD-1) is likely to result in improved tumor control. As before, we utilized the B16F10-OVA model that is refractory to anti-PD-1 monotherapy. Importantly, we found that anti-JAML/anti-PD-1 combination therapy resulted in greater reduction in tumor growth, demonstrating their synergistic effects (Fig. 7C). This enhanced anti-tumor response was associated with a significant increase in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) (Fig. 7D), and was predominantly mediated by elevated levels of CD8+ TILs, while the frequencies of CD4+ non-TREG or CD4+ TREG cells remained stable (Fig. 7E,F). Notably, the proportion of granzyme B expressing CD8+ TILs was also significantly higher in combination therapy compared to anti-JAML monotherapy or isotype controls (Fig. 7G). Together, these findings provide mechanistic insights as to why agonistic anti-JAML therapy synergizes with anti-PD-1 treatment to improve tumor control.

Discussion

Immunotherapies utilizing agonistic antibodies were initially considered to mainly activate the CD8+ T cell compartment, without appreciating potential effects on regulatory T cell subsets. However, subsequent studies have demonstrated that various immunotherapy drugs suffer from ‘on-target/off-cell effects’ and ‘on-target/off-tumor effects’, effectively dampening their treatment efficacy and clinical use. This initially underappreciated mechanism infers that T cell subsets other than CD8+ T cells (i.e. suppressive TREG or TFR cells) can express high levels of a given immunotherapy drug target in tumor tissues (on-target/off-cell effects). By binding and activating such suppressive cells, immunotherapies can create an immunosuppressive milieu and thus impede clinical potential and utility. Contrary to that, an overactivation of the immune system in normal tissues (on-target/off-tumor effects), frequently observed by non-specifically targeting TREG cells with anti-CTLA-4 and further exacerbated by combination with anti-PD-1 therapy, can cause severe irAEs. Hence, there remains an unmet need for the development of immunotherapy targets that exhibit a more restricted expression profile.

Here we show that the co-stimulatory molecule JAML is highly expressed in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRM cells in multiple human cancer types, and that its expression is associated with enhanced functional potential of TRM cells and also improved long-term survival outcomes in a cohort of HNSCC patients. Utilizing in vitro stimulation and CRISPR-Cas9 assays, we found that JAML signaling through its endogenous ligand CXADR potently and selectively activates CD8+ T cells, and to a lesser degree, CD4+ T cells. These assays also revealed that JAML is potently induced by TCR signaling, implying that antigen-recognition drives JAML expression. We demonstrated extensive 3D chromatin interactions between the promoters of CD3D and JAML in human T cells, but not other immune cell types like monocytes, implying that these cis-regulatory interactions might drive JAML expression. Crucially, these data suggest that agonistic anti-JAML antibodies might preferentially target and co-stimulate tumor-antigen specific CD8+ T cells, which upregulated JAML expression due to recent TCR engagement, in tumor tissues. Accordingly, anti-JAML therapy showed beneficial effects in a murine melanoma model, an effect that was dependent on CD8+ T cells. Moreover, we found JAML expression to be predominantly restricted to CD8+ T cells in tumor tissue, with low expression in T cells from other organs or other T cell compartments, further substantiating the notion that it might specifically activate (antigen-specific) CD8+ T cells in the TME, thus reducing the risk of irAEs in non-malignant organs. Crucially, in murine tumors, we found two distinct subsets of JAML-expressing CD8+ T cells; (i) a ‘stem-like’ population of CD8+ T cells expressing high levels of Tcf7, demonstrated to be pivotal for efficacious immune responses against viruses and tumors, and (ii), a Pdcd-1 enriched effector CTL cluster, likely driving anti-tumor effects. Furthermore, by uncovering an interconnected pathway between JAML and PD-1, our data provide mechanistic insights for the observed synergistic effects of anti-JAML and anti-PD-1 therapy, which significantly increased TIL infiltration and thus efficiently controlled tumor growth. While a recent study described JAML as a potential cancer immunotherapy target in mice18, our study provides critical insights into how anti-JAML agonistic antibody mediates its function and identify JAML as an immunotherapy target in tumor-infiltrating TRM cells with a low risk of ‘off-cell’ and ‘off-tumor’ effects, features that are likely to enhance anti-tumor efficacy without causing significant irAEs in humans.

Limitations of the study

We demonstrate that JAML is an attractive immunotherapy target that might primarily activate tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. A major limitation of the study is the lack of JAML protein expression data on human TIL populations, as well as on T cell subsets in non-malignant organs. This is crucial for the assessment of potential irAEs and thus requires assessments in future studies.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests should be directed to Pandurangan Vijayanand (vijay@lji.org)

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents

Data and code availability.

Expression data have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE185162, password: wtwdemycbdenpmz). This Super Series includes data from mouse samples. Source data are provided with this paper. H3K27ac ChIP-seq and HiChIP data for 6 common immune cell and ATAC-seq data for 15 DICE cell types have been previously reported24,25,38 and are available from the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP; accession number: phs001703.v4.p1). ATAC-seq data for TRM cells and non-TRM cells were previously reported10 and are available on GEO (accession number: GSE111898). NFATC1 and NFATC2 ChIP-seq data was obtained from GEO (accession number: GSM2810039 and GSM2810040 respectively). All original code has been deposited on GitHub (https://github.com/vijaybioinfo/JAML_reproducibility) and is publicly available as of the date of publication. An explanation and version changes are included. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice.

C57BL/6J (stock no. 000664), OT-I (stock no. 003831). CD45.1 (stock no. 002014), CD8−/− (stock no. 002665) and TCF7GFP flox (stock no. 030909) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. In all experiments, female mice (6–12 weeks old) were used. In the vivarium, housing temperature was kept within the range of 20–24 °C; humidity was monitored but not controlled and ranged from 30 to 70%. The mice were kept in 12h light–dark cycles (06:00–18:00 light). The La Jolla institute for Immunology Animal Ethics Committee approved all animal work.

METHOD DETAILS

Tumor cell lines.

MC38-OVA cells, a gift from the S. Fuchs laboratory (UPenn) were approved for use by M. Smyth (Peter MacCallum cancer center). The B16F10-OVA cells were a gift from the J. Linden laboratory (LJI). All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma infection and were subsequently treated with Plasmocin (InvivoGen) to prevent contamination.

Tumor models.

Tumor models were used as described before7. The mice were s.c. inoculated with 2×106 MC38-OVA cells (CXADR+/+ or CXADR−/−) or 1–1.5 × 105 B16F10-OVA cells into the right flank. The mice were injected intraperitoneally at indicated time points with either 200μg isotype control antibodies, anti-PD-1 (29F1. A1, Bioxcell) or anti-JAML (4E10, Biolegend). Tumor size was monitored every 2–3 days to ensure that the tumors did not exceed 25mm in diameter. At experimental endpoint, tumors were harvested and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were analyzed. Tumor volume was calculated as described previously7.

CRISPR assays.

Human or murine CD8+ T cells were activated with 2μg/ml of anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for 48h prior to electroporation and transfection with a pre-mixed sgRNA targeting JAML, CXADR or an irrelevant gene region using the Neon Transfection System (settings: 1,600V, 10ms, 3 pulses). Knockdown efficiency was evaluated via flow-cytometry (murine) or real-time PCR (human) for transcripts. crRNA targeting murine Jaml: GGCCCTGTGGATAACCTACA, crRNA targeting murine Cxadr: ACGAGTAACGATGTCAAGTC, crRNA targeting human JAML: TGTCCCCCATCAAGTGTACG.

In vitro assays.

CD8+ T cells were labeled with CellTrace Violet (ThermoFisher). Subsequently, 20,000 cells were added to 96-well cell-culture plates containing 40,000 CXADR+/+ or CXADR−/− cells respectively in 200μl complete RPMI medium. CD8+ T cell proliferation was determined three days later. For detection of early activation markers, cells were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of anti-CD3, anti-JAML, anti-CD28 or recombinant CXADR Fc (chimeric fusion protein).

Flow cytometry.

Lymphocytes were isolated from the liver or spleen by mechanically dispersing the cells through a 70μm cell strainer (Miltenyi) generating single-cell suspensions. RBC lysis (BioLegend) was performed to lyse and remove red blood cells. Tumors were harvested and TILs were isolated by dispersing the tumors in 2 ml sterile PBS and subsequently incubating the samples at 37°C with liberase DL (Roche) and DNase I (Sigma) for 15 min. Colonic tissue cell were isolated as described previously39. To create single-cell suspensions, the samples (tumor, liver, colon or spleen) were passed through a 70-μm cell strainer. The cells were kept in staining buffer (PBS with 2 mM EDTA and 2% FBS), FcγR blocked (clone 2.4G2, BD Biosciences), followed by staining with the indicated antibodies at 4°C for 30 min; secondary stains were conducted where indicated for selected markers. The samples were then either sorted or fixed and stained intracellularly with a FOXP3 transcription factor kit (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To determine cell viability, fixable viability dye (ThermoFisher) was used in all staining reactions. For the bulk RNA-seq analyses, we sorted tumor-infiltrating TREG or CD8+ cells based on the expression of the indicated markers (Fig. 7a). All samples were sorted on a BD FACS Fusion system or acquired on a BD FACS Fortessa system (both BD Biosciences) and then analyzed using FlowJo 10.4.1. CXADR antibody was obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: Monoclonal Anti-Mouse Coxsackie and Adenovirus Receptor, Clone U54.R.mCAR.4 (immunoglobulin G, Rat), NR-9216.

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

The primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry included anti-CD8 (pre-diluted; C8/144B, Agilent Dako), anti-JAML (1:100; Atlas, HPA047929), anti-CD103 (1:500; Abcam, ab129202), CK (1:5; Dako, AE1/AE3) The samples for the immunohistochemical analyses were prepared, stained and analyzed as previously described7. Cells were identified by nucleus detection and cytoplasmic regions were simulated up to 5 μm per cell; protein expression was measured using the mean staining intensity within the simulated cell regions.

Bulk RNA-seq.

Total RNA was purified from murine tumor-infiltrating TREG (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+FOXP3+) and CD8+ T (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD8+) cells using the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) and quantified as previously described9,40. RNA-seq libraries were prepared with a Smart-seq2 protocol and were sequenced on an Illumina platform41. Quality-control was applied as previously described9 and data were analyzed as described previously7.

Meta-analysis of published single-cell RNA-seq studies.

The meta-analysis was conducted as described previously7. In brief, nine published single-cell RNA-seq datasets28,42–49 of CD4-expressing and CD8-expressing (n=22,410) tumor-infiltrating T cells were integrated with UMAP using the R package Seurat v3.0. For each dataset, cells that expressed fewer than 200 genes were considered outliers and discarded. We integrated data from all cohorts using the alignment by the ‘anchors’ option in Seurat 3.0 as described previously7. Briefly, the alignment is a computational strategy to ‘anchor’ diverse datasets together, facilitating the integration and comparison of single-cell measurements from different technologies and modalities. The ‘anchors’ correspond to similar biological states between datasets. These pairwise correspondences between datasets allows the transformation of datasets into a shared space regardless of the existence of large technical and/or biological divergences. This improved function in Seurat 3.0 allows integration of multiple RNA-seq datasets generated by different platforms50. We used the FindIntegrationAnchors function to find correspondences across the different study datasets with default parameters (dimensionality = 1:30). Furthermore, we used the IntegrateData function to generate a Seurat Object with an integrated and batch-corrected expression matrix. In total, 22,410 cells and 2,000 most variable genes were used for clustering. We used the standard workflow from Seurat, scaling the integrated data, finding relevant components with principal-component analysis and visualizing the results with UMAP. The number of relevant components was determined from an elbow plot. UMAP dimensionality reduction and clustering were applied with the following parameters: 2,000 genes; 30 principal components; resolution, 0.4. The cells that were used for the integration were selected from clusters labeled in the original studies as tumor CD4+ T cells and from pretreatment samples when necessary.

Single-cell transcriptome analysis.

Murine CD45+JAML+ cells from three B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing mice were isolated and prepared as described above. Cells from each mouse were barcoded with murine Totalseq-B antibodies. Cells were sorted and complementary DNA libraries were constructed using the standard 10x Genomics sequencing protocol. The antibody capture data were analyzed using custom scripts (github.com/vijaybioinfo/ab_capture), as previously described7. n=8,474 cells were sequenced and doublets51, cells with fewer than 1,500 and more than 6,000 expressed genes, less than 1,000 and more than 50,000 counts, and more than 5% mitochondrial counts were filtered out. 5,976 cells were used for downstream analyses. For clustering with Seurat (3.0), we used 15 principal components from a set of highly variable genes (n = 609) taking 20% of the variance after filtering out genes with a mean expression of less than 0.01. Differential gene expression was calculated using MAST (P<0.05, log2FC>0.25) as described previously7.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

The number of mice per group and statistical tests used can be found in the figure legends. Details on sample elimination, quality control, and displayed data are stated in the figure legends and methods. Sample sizes were based on previous experiments and published studies to ensure reliable statistical testing accounting for variability between groups. Mice that did not develop tumors by 10 days after inoculation, before therapeutic intervention, were not included in the analyses. Low quality samples were excluded from the analyses and stated in the methods section. Data in heatmaps are displayed as log2-normalized z-scores. Experiments were reproduced in at least two independent experiments. Age and sex-matched mice were used in the experiments and animals were randomly assigned to the experimental groups. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9. The graphical abstract has been created with Biorender.com.

Supplementary Material

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies - mouse | ||

| KLRG1 – BV421 | Biolegend | Cat#138414, RRID: AB_2565613 |

| CD3 – BV510 | Biolegend | Cat#100353, RRID: AB_2565879 |

| PD-1 – BV605 | Biolegend | Cat#135220, RRID: AB_2562616 |

| CD19 – BV650 | Biolegend | Cat#115541, RRID: AB_11204087 |

| CX3CR1 – BV711 | Biolegend | Cat#149031, RRID: AB_2565939 |

| FOXP3 – FITC | eBioscience | Cat#11-5773-82, RRID: AB_465243 |

| CD4 – PE-D594 | Biolegend | Cat#100566, RRID: AB_2563685 |

| CD8 – BB700 | BD Biosciences | Cat#566409, RRID: AB_2744467 |

| CD103 – BV421 | Biolegend | Cat#121421, RRID: AB_2562901 |

| JAML – APC | Miltenyi | Cat#130-114-680, |

| CD25 – BB700 | BD Biosciences | Cat#566498, RRID: AB_2744345 |

| 4-1BB – PE | Biolegend | Cat#106106, RRID: AB_2287565 |

| CD69 – BV786 | Biolegend | Cat#104543, RRID: AB_2629640 |

| CXADR – A647 | BEI Resources | NR-9216, RRID: N/A |

| Antibodies - human | ||

| ICOS – BV786 | Biolegend | Cat#313534, RRID: AB_2629729 |

| GITR – BV711 | Biolegend | Cat#371212, RRID: AB_2687161 |

| PD-1 – BV421 | BD Biosciences | Cat#562584, RRID: AB_2737668 |

| 4-1BB – APC | Biolegend | Cat#309810, RRID: A AB_830672 |

| CD25 – PE | BD Biosciences | Cat#555432, RRID: AB_395826 |

| CD69 – BV605 | Biolegend | Cat#310938, RRID: AB_2562307 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| CXADR Fc | R&D Systems | Cat#3336-CX-050 RRID: N/A |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw and analyzed data | This paper | GEO: GSE185162 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| MC38-OVA | Peter MacCallum cancer center | N/A |

| B16F10-OVA | LJI | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratories | #000664 |

| OT-I | Jackson Laboratories | #003831 |

| CD45.1 | Jackson Laboratories | #002014 |

| CD8−/− | Jackson Laboratories | #002665 |

| TCF7GFP flox | Jackson Laboratories | #030909 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Cell Ranger 3.1.0 | 10x Genomics | https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/downloads/latest |

| bcl2fastq2 v2.20 | illumina | https://support.illumina.com/sequencing/sequencing_software/bcl2fastq-conversion-software.html |

| Scrublet 0.2.3 | Wolock et al. | https://github.com/swolock/scrublet |

| Seurat 3.1.5 | Stuart et al. | https://github.com/satijalab/seurat |

| Other | ||

| Analysis code | This paper | https://github.com/vijaybioinfo/JAML_reproducibility |

Acknowledgements.

This work was funded by a combination of institutional, philanthropic, and corporate support. We thank C. Kim, D. Hinz, and C. Dillingham for their assistance with cell sorting (FACS Aria Fusion Cell Sorter; grant no. S10 RR027366); H. Simon for assistance with library preparation, next-generation sequencing using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 (NIH grant no. S10OD016262) and NovaSeq6000 (grant no. S10OD025052-01). This work was supported by the William K. Bowes, Jr. Foundation (P.V.) and the Whitaker Foundation (C.H.O.). The funders have no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Inclusion and diversity. We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Declaration of interests. The La Jolla Institute of Immunology has filed a patent “Methods for modulating an immune response to cancer or tumor cells” related to this work and S.E., P.V. and C.H.O. are co-inventors on this patent.

References

- 1.Wolf Y, Anderson AC, and Kuchroo VK (2020). TIM3 comes of age as an inhibitory receptor. Nat Rev Immunol 20, 173–185. 10.1038/s41577-019-0224-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manieri NA, Chiang EY, and Grogan JL (2017). TIGIT: A Key Inhibitor of the Cancer Immunity Cycle. Trends Immunol 38, 20–28. 10.1016/j.it.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang B, Zhang W, Jankovic V, Golubov J, Poon P, Oswald EM, Gurer C, Wei J, Ramos I, Wu Q, et al. (2018). Combination cancer immunotherapy targeting PD-1 and GITR can rescue CD8+ T cell dysfunction and maintain memory phenotype. Sci Immunol. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat7061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao J, Ward JF, Pettaway CA, Shi LZ, Subudhi SK, Vence LM, Zhao H, Chen J, Chen H, Efstathiou E, et al. (2017). VISTA is an inhibitory immune checkpoint that is increased after ipilimumab therapy in patients with prostate cancer. Nat Med 23, 551–555. 10.1038/nm.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews LP, Somasundaram A, Moskovitz JM, Szymczak-Workman AL, Liu C, Cillo AR, Lin H, Normolle DP, Moynihan KD, Taniuchi I, et al. (2020). Resistance to PD1 blockade in the absence of metalloprotease-mediated LAG3 shedding. Sci Immunol 5. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soldevilla MM, Villanueva H, Meraviglia-Crivelli D, Menon AP, Ruiz M, Cebollero J, Villalba M, Moreno B, Lozano T, Llopiz D, et al. (2019). ICOS Costimulation at the Tumor Site in Combination with CTLA-4 Blockade Therapy Elicits Strong Tumor Immunity. Molecular Therapy 27, 1878–1891. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eschweiler S, Clarke J, Ramírez-Suástegui C, Panwar B, Madrigal A, Chee SJ, Karydis I, Woo E, Alzetani A, Elsheikh S, et al. (2021). Intratumoral follicular regulatory T cells curtail anti-PD-1 treatment efficacy. Nat Immunol, 1–12. 10.1038/s41590-021-00958-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumagai S, Togashi Y, Kamada T, Sugiyama E, Nishinakamura H, Takeuchi Y, Vitaly K, Itahashi K, Maeda Y, Matsui S, et al. (2020). The PD-1 expression balance between effector and regulatory T cells predicts the clinical efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapies. Nat Immunol. 10.1038/s41590-020-0769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganesan A-P, Clarke J, Wood O, Garrido-Martin EM, Chee SJ, Mellows T, Samaniego-Castruita D, Singh D, Seumois G, Alzetani A, et al. (2017). Tissue-resident memory features are linked to the magnitude of cytotoxic T cell responses in human lung cancer. Nat Immunol 18, 940–950. 10.1038/ni.3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke J, Panwar B, Madrigal A, Singh D, Gujar R, Wood O, Chee SJ, Eschweiler S, King EV, Awad AS, et al. (2019). Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of tissue-resident memory T cells in human lung cancer. Journal of Experimental Medicine 216. 10.1084/jem.20190249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savas P, Virassamy B, Ye C, Salim A, Mintoff CP, Caramia F, Salgado R, Byrne DJ, Teo ZL, Dushyanthen S, et al. (2018). Single-cell profiling of breast cancer T cells reveals a tissue-resident memory subset associated with improved prognosis. Nat Med 24, 986–993. 10.1038/s41591-018-0078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okla K, Farber DL, and Zou W (2021). Tissue-resident memory T cells in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Journal of Experimental Medicine 218. 10.1084/jem.20201605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoni Y, Becht E, Fehlings M, Loh CY, Koo S-L, Teng KWW, Yeong JPS, Nahar R, Zhang T, Kared H, et al. (2018). Bystander CD8+ T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature 2018 557:7706 557, 575–579. 10.1038/s41586-018-0130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pardoll DM (2012). The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 12, 252–264. 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu T-E, Pluzanski A, Lee JS, Otterson GA, Audigier-Valette C, Minenza E, Linardou H, Burgers S, Salman P, et al. (2018). Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. New England Journal of Medicine, NEJMoa1801946. 10.1056/NEJMoa1801946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verdino P, Witherden DA, Havran WL, and Wilson IA (2010). The molecular interaction of CAR and JAML recruits the central cell signal transducer PI3K. Science 329(5996), 10.1126/science.1187996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witherden DA, Verdino P, Rieder SE, Garijo O, Mills RE, Teyton L, Fischer WH, Wilson IA, and Havran WL (2010). The junctional adhesion molecule JAML is a costimulatory receptor for epithelial γδ T cell activation. Science 329(5996). 10.1126/science.1192698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGraw JM, Thelen F, Hampton EN, Bruno NE, Young TS, Havran WL, and Witherden DA (2021). JAML promotes CD8 and γδ T cell antitumor immunity and is a novel target for cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Experimental Medicine 218. 10.1084/JEM.20202644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchan SL, Dou L, Remer M, Booth SG, Dunn SN, Lai C, Semmrich M, Teige I, Mårtensson L, Penfold CA, et al. (2018). Antibodies to Costimulatory Receptor 4-1BB Enhance Anti-tumor Immunity via T Regulatory Cell Depletion and Promotion of CD8 T Cell Effector Function. Immunity. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamada T, Togashi Y, Tay C, Ha D, Sasaki A, and Nakamura Y (2019). PD-1 + regulatory T cells amplified by PD-1 blockade promote hyperprogression of cancer. 116. 10.1073/pnas.1822001116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards J, Wilmott JS, Madore J, Gide TN, Quek C, Tasker A, Ferguson A, Chen J, Hewavisenti R, Hersey P, et al. (2018). CD103+ tumor-resident CD8+ T cells are associated with improved survival in immunotherapy-naïve melanoma patients and expand significantly during anti-PD-1 treatment. Clinical Cancer Research 24, 3036–3045. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SL, Gebhardt T, and Mackay LK (2019). Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Cancer Immunosurveillance. Trends Immunol 40, 735–747. 10.1016/j.it.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park SL, Buzzai A, Rautela J, Hor JL, Hochheiser K, Effern M, McBain N, Wagner T, Edwards J, McConville R, et al. (2019). Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells promote melanoma–immune equilibrium in skin. Nature 565, 366–371. 10.1038/s41586-018-0812-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmiedel BJ, Singh D, Madrigal A, Valdovino-Gonzalez AG, White BM, Zapardiel-Gonzalo J, Ha B, Altay G, Greenbaum JA, McVicker G, et al. (2018). Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms on Human Immune Cell Gene Expression. Cell 175, 1701–1715.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandra V, Bhattacharyya S, Schmiedel BJ, Madrigal A, Gonzalez-Colin C, Fotsing S, Crinklaw A, Seumois G, Mohammadi P, Kronenberg M, et al. (2021). Promoter-interacting expression quantitative trait loci are enriched for functional genetic variants. Nat Genet 53, 110–119. 10.1038/s41588-020-00745-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Im SJ, Hashimoto M, Gerner MY, Lee J, Kissick HT, Burger MC, Shan Q, Hale JS, Lee J, Nasti TH, et al. (2016). Defining CD8+ T cells that provide the proliferative burst after PD-1 therapy. Nature 537, 417–421. 10.1038/nature19330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siddiqui I, Schaeuble K, Chennupati V, Marraco SAF, Calderon-copete S, Ferreira DP, Carmona SJ, Scarpellino L, Gfeller D, Pradervand S, et al. (2019). Intratumoral Tcf1+PD-1+CD8+ T Cells with Stem-like Properties Promote Tumor Control in Response to Vaccination and Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy. Immunity 50, 1–17. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sade-Feldman M, Yizhak K, Bjorgaard SL, Ray JP, de Boer CG, Jenkins RW, Lieb DJ, Chen JH, Frederick DT, Barzily-Rokni M, et al. (2018). Defining T Cell States Associated with Response to Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Melanoma. Cell 175, 998–1013.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott AC, Dündar F, Zumbo P, Chandran SS, Klebanoff CA, Shakiba M, Trivedi P, Menocal L, Appleby H, Camara S, et al. (2019). TOX is a critical regulator of tumour-specific T cell differentiation. Nature. 10.1038/s41586-019-1324-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bassez A, Vos H, Van Dyck L, Floris G, Arijs I, Desmedt C, Boeckx B, Vanden Bempt M, Nevelsteen I, Lambein K, et al. (2021). A single-cell map of intratumoral changes during anti-PD1 treatment of patients with breast cancer. Nature Medicine 2021 27:5 27, 820–832. 10.1038/s41591-021-01323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alfei F, Kanev K, Hofmann M, Wu M, Ghoneim HE, Roelli P, Utzschneider DT, von Hoesslin M, Cullen JG, Fan Y, et al. (2019). TOX reinforces the phenotype and longevity of exhausted T cells in chronic viral infection. Nature. 10.1038/s41586-019-1326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Z, Wang S, Goplen NP, Li C, Cheon IS, Dai Q, Huang S, Shan J, Ma C, Ye Z, et al. (2019). PD-1hi CD8+ resident memory T cells balance immunity and fibrotic sequelae. Sci Immunol 4, 1217. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber DA, Sumagin R, McCall IC, Leoni G, Neumann PA, Andargachew R, Brazil JC, Medina-Contreras O, Denning TL, Nusrat A, et al. (2014). Neutrophil-derived JAML inhibits repair of intestinal epithelial injury during acute inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 7, 1221–1232. 10.1038/mi.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alshetaiwi H, Pervolarakis N, McIntyre LL, Ma D, Nguyen Q, Rath JA, Nee K, Hernandez G, Evans K, Torosian L, et al. (2020). Defining the emergence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer using single-cell transcriptomics. Sci Immunol 5, 6017. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleffel S, Posch C, Barthel SR, Mueller H, Schlapbach C, Guenova E, Elco CP, Lee N, Juneja VR, Zhan Q, et al. (2015). Melanoma Cell-Intrinsic PD-1 Receptor Functions Promote Tumor Growth. Cell 162, 1242–1256. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamphorst AO, Wieland A, Nasti T, Yang S, Zhang R, Barber DL, Konieczny BT, Candace Z, Koenig L, et al. (2017). Rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells by PD-1 – targeted therapies is CD28-dependent. Science 355(6332). 10.1126/science.aaf0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hui E, Zhu J, Cheung J, Su X, Taylor MJ, Kim JM, Mellman I, and Vale RD (2017). The T cell costimulatory receptor CD28 is a primary target of PD-1 mediated inhibition. Science 355(6332). 10.1126/science.aaf1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmiedel BJ, Chandra V, Rocha J, Gonzalez-Colin C, Bhattacharyya S, Madrigal A, Ottensmeier CH, Ay F, and Vijayanand P (2021). COVID-19 genetic risk variants are associated with expression of multiple genes in diverse immune cell types. Nat Commun, 12(1):6760. 10.1038/s41467-021-26888-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eschweiler S, Ramírez-Suástegui C, Li Y, King E, Chudley L, Thomas J, Wood O, von Witzleben A, Jeffrey D, McCann K, et al. (2022). Intermittent PI3Kδ inhibition sustains anti-tumour immunity and curbs irAEs. Nature 2022 605:7911 605, 741–746. 10.1038/s41586-022-04685-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engel I, Seumois G, Chavez L, Samaniego-Castruita D, White B, Chawla A, Mock D, Vijayanand P, and Kronenberg M (2016). Innate-like functions of natural killer T cell subsets result from highly divergent gene programs. Nat Immunol. 10.1038/ni.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picelli S, Faridani OR, Björklund ÅK, Winberg G, Sagasser S, and Sandberg R (2014). Full-length RNA-seq from single cells using Smart-seq2. Nat Protoc 9, 171–181. 10.1038/nprot.2014.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo X, Zhang Y, Zheng L, Zheng C, Song J, Zhang Q, Kang B, Liu Z, Jin L, Xing R, et al. (2018). Global characterization of T cells in non-small-cell lung cancer by single-cell sequencing. 24. 10.1038/s41591-018-0045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng C, Zheng L, Yoo J, Guo H, Zhang Y, and Guo X (2017). Landscape of Infiltrating T Cells in Liver Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell Sequencing Resource Landscape of Infiltrating T Cells in Liver Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell Sequencing. Cell 169, 1342–1356.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang L, Yu X, Zheng L, Zhang Y, Li Y, Fang Q, Gao R, Kang B, Zhang Q, Huang JY, et al. (2018). Lineage tracking reveals dynamic relationships of T cells in colorectal cancer. Nature 564, 268–272. 10.1038/s41586-018-0694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puram SV, Tirosh I, Parikh AS, Patel AP, Yizhak K, Gillespie S, Rodman C, Luo CL, Mroz EA, Emerick KS, et al. (2017). Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Primary and Metastatic Tumor Ecosystems in Head and Neck Cancer. Cell 171, 1611–1624.e24. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jerby-Arnon L, Shah P, Cuoco MS, Rodman C, Su MJ, Melms JC, Leeson R, Kanodia A, Mei S, Lin JR, et al. (2018). A Cancer Cell Program Promotes T Cell Exclusion and Resistance to Checkpoint Blockade. Cell 175, 984–997.e24. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oh DY, Kwek SS, Raju SS, Li T, McCarthy E, Chow E, Aran D, Ilano A, Pai CCS, Rancan C, et al. (2020). Intratumoral CD4+ T Cells Mediate Anti-tumor Cytotoxicity in Human Bladder Cancer. Cell 181, 1612–1625.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Z. L, L. Z, S. KM, F. Q, Z. W, O. SA, H. Y, W. L, Z. Q, K. A, et al. (2020). Single-Cell Analyses Inform Mechanisms of Myeloid-Targeted Therapies in Colon Cancer. Cell 181, 442–459.e29. 10.1016/J.CELL.2020.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.M. A, M. CE, R. JK, H. L, H. F, K. DL, Y. EA, S. EL, T. W, Z. A, et al. (2020). Therapy-Induced Evolution of Human Lung Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Cell 182, 1232–1251.e22. 10.1016/J.CELL.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM, Hao Y, Stoeckius M, Smibert P, and Satija R (2019). Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e21. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolock SL, Lopez R, and Klein AM (2019). Scrublet: Computational Identification of Cell Doublets in Single-Cell Transcriptomic Data. Cell Syst 8, 281–291.e9. 10.1016/J.CELS.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Expression data have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE185162, password: wtwdemycbdenpmz). This Super Series includes data from mouse samples. Source data are provided with this paper. H3K27ac ChIP-seq and HiChIP data for 6 common immune cell and ATAC-seq data for 15 DICE cell types have been previously reported24,25,38 and are available from the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP; accession number: phs001703.v4.p1). ATAC-seq data for TRM cells and non-TRM cells were previously reported10 and are available on GEO (accession number: GSE111898). NFATC1 and NFATC2 ChIP-seq data was obtained from GEO (accession number: GSM2810039 and GSM2810040 respectively). All original code has been deposited on GitHub (https://github.com/vijaybioinfo/JAML_reproducibility) and is publicly available as of the date of publication. An explanation and version changes are included. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.