Abstract

We describe a case of vasospastic angina diagnosed via a personal electrocardiography monitoring device in a middle-aged woman who initially presented with chest pain and angiographic findings demonstrating coronary emboli. (Level of Difficulty: Beginner.)

Key Words: cardiovascular disease, chest pain, electrocardiogram, myocardial ischemia, thrombosis

Graphical abstract

History of Presentation

A 48-year-old woman presented to the hospital with chest pain for the past 4 days. The pain was described as a burning sensation from the middle of her chest that started at rest without exertion and radiated to her left neck. It came on gradually and was initially mild and intermittent, lasting about 2 to 5 minutes and occurring a few times a day, but then became progressively more severe and constant over the subsequent days, eventually waking her up in the middle of the night. She had associated nausea with clear emesis that did not improve with trials of over-the-counter aluminum hydroxide/magnesium hydroxide, calcium carbonate, or famotidine. Vitals included a heart rate of 73 beats/min, blood pressure of 161/96 mm Hg, and respiratory rate of 22 breaths/min. The patient appeared comfortable. Cardiac auscultation demonstrated a normal S1 and S2 and regular rate and rhythm, without murmurs or rubs. Lungs were clear on auscultation, and there was no lower extremity edema.

Learning Objectives

-

•

To develop a broad cardiac differential for young female patients who present with chest pain.

-

•

To describe and recognize the utility of a personal ECG device in the diagnosis of vasospastic angina.

-

•

To understand that severe vasospasm can present with thrombosis and is managed with calcium-channel blockers.

Past Medical History

She had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes and a family history of coronary artery disease and immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Her grandfather and brother both had myocardial infarctions in their mid-50s. ITP was diagnosed at the time of her second pregnancy without history of venous or arterial clots. She was still having menses and was not on hormonal therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

In this female patient with traditional risk factors of coronary artery disease with possible cardiac chest pain and associated symptoms of nausea and vomiting, ischemia from obstructive plaque rupture needs to be strongly considered. Her family history and young age raise the possibility of genetic disorders of lipid metabolism, including elevated lipoprotein(a) and familial hypercholesterolemia, that could predispose her to that pathology. Hypercoagulable evaluation should include a history of menses, autoimmune conditions such as antiphospholipid syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus, a family history of cancer, and the use of exogenous hormonal therapies. Paradoxically, the risk for thrombosis is higher in patients with ITP due to hyperactive young platelets, so coronary embolism from a deep vein thrombosis traveling through a right-to-left shunt should be evaluated.

Other nonobstructive etiologies to consider include spontaneous coronary artery dissection, coronary vasospasm, and microvascular disease.

Investigations

Labs were notable for rising high-sensitivity troponin T levels, from 52 ng/dL to 116 ng/dL and then 339 ng/dL (reference, normal: ≤19 ng/L). Electrocardiography demonstrated T-wave inversions in the inferior leads, new from prior (Figure 1). Transthoracic echocardiography showed normal left ventricular systolic function with ejection fraction of 60% and no significant valvular or wall motion abnormalities. Cardiac catheterization showed thrombosis of the distal left anterior descending artery and distal right posterolateral artery, concerning for coronary emboli (Figure 2 and 3, Videos 1 to 4). Evaluation for a potential embolic source was negative, including a negative lower extremity Doppler ultrasound, repeat echocardiogram with bubble study, and absence of atrial fibrillation on telemetry.

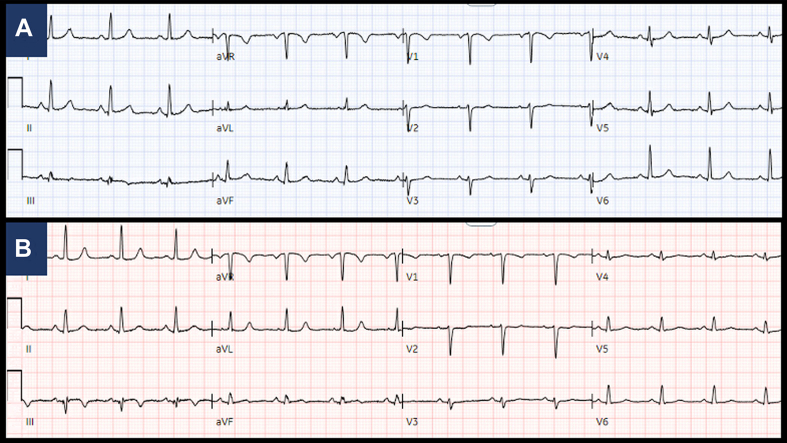

Figure 1.

Electrocardiography, Baseline and at Presentation

Baseline electrocardiography (A) from months prior showing normal sinus rhythm and (B) at time of presentation demonstrating normal sinus rhythm with nonspecific T-wave abnormalities in leads III and aVF.

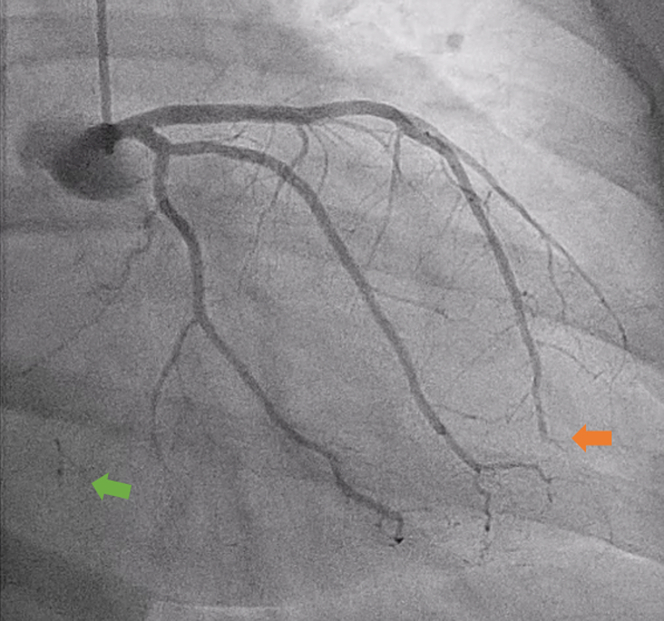

Figure 2.

Coronary Angiogram

Right anterior oblique caudal angiogram demonstrating left anterior descending artery embolism (orange arrow) and left-to-right collaterals (green arrow).

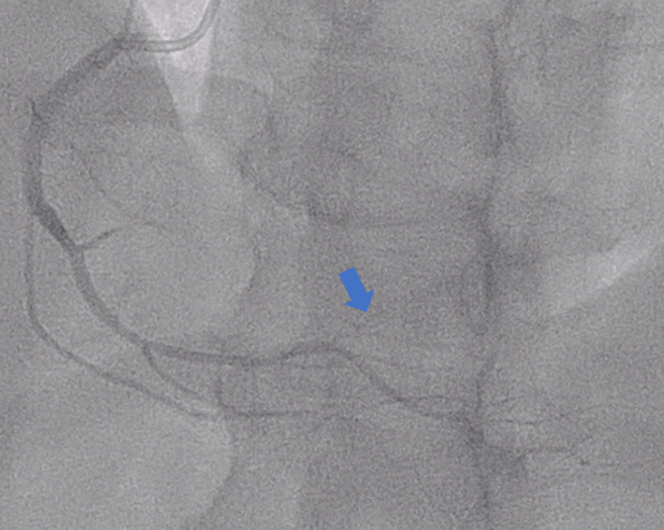

Figure 3.

Coronary Angiogram

Left anterior oblique cranial angiogram of faint/absent right posterolateral (blue arrow).

Management (Medical/Interventions)

She was discharged on metoprolol, atorvastatin, and apixaban, with a presumed thrombotic or embolic mechanism of pathology. Atrial fibrillation was not detected on a Holter monitor. Her ITP history prompted an autoimmune hypercoagulability workup, which was unremarkable. The patient continued to have similar and recurrent chest pain episodes lasting 3 to 5 minutes despite her medical therapies and normal electrocardiography (ECG) at follow-up. She then obtained a 6-lead personal ECG monitoring device (KardiaMobile 6L, AliveCor) and later captured transient ST-segment elevations (STEs) with her most severe chest pain episodes (Figure 4), establishing the diagnosis of vasospastic angina. Her metoprolol was changed to verapamil, resulting in resolution of her chest pain symptoms.

Figure 4.

ST-Segment Elevation in Inferior Leads Captured by Personal Handheld Device

Six-lead electrocardiography (ECG) monitor device (center) and our patient’s recorded electrocardiography (A) at baseline and (B) during vasospasm episode, which shows inferior ST-segment elevation with anterior ST-segment depression.

Discussion: Association With Current Guidelines/Position Papers/Current Practice

Vasospastic angina is an underdiagnosed yet very common cause of ischemia with no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA). Diagnosis is made by capturing transient STEs that are associated with chest pain episodes. Because the STE may be so brief, electrocardiographic documentation proves to be difficult. In the absence of serendipitously capturing the events, the current gold standard method for diagnosis involves testing with a provocative stimulus, usually acetylcholine, during invasive coronary angiography.1 The randomized control Stratified Medical Therapy Using Invasive Coronary Function Testing in Angina: The CORonary MICrovascular Angina (CorMicA) trial showed benefit of improved angina in patients with no obstructive CAD through stratified medical therapy following a diagnosis with an interventional diagnostic procedure (IDP).2 Provocative testing can help distinguish those patients with vasospastic angina, microvascular angina, and noncardiac chest pain but is not without the rare risk of serious major complications, including cardiogenic shock and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia. Such testing requires operator comfort, experience, and time and is thus limited in practice.3 More often, noninvasive diagnostic tools lead to the consideration of INOCA followed by empiric trials of nitrates and calcium-channel blockers to arrive at the working diagnosis of vasospastic angina.

Here, we present the first reported alternative noninvasive, consumer-friendly, and economical means of diagnosing vasospastic angina with the use of an ambulatory ECG monitoring device that changed management and resultant symptoms. Based on the patient’s history and risk factors, inductive reasoning was used to generate the working hypothesis that a hypercoagulopathy caused her to have coronary emboli and associated chest pain. Further hematologic and lipid disorder investigation was pursued but did not support the initial hypothesis. The limitation of inductive reasoning is that new factors or evidence may emerge that prove a working hypothesis wrong. Thus, when generating treatment plans with this type of reasoning, consideration of other potential differential diagnoses must remain open. In this case, new evidence demonstrated by the device helped conclude that our patient’s presenting non–STE myocardial infarction was due to vasospasm-related thrombus.

Digital health tools, especially mobile applications and wearables, can be utilized for out-of-hospital patient monitoring. As they become more ubiquitous and affordable, patients may turn to them as an adjunct to traditional care management, providing patient empowerment and reassurance, and they may prove to have novel use cases. The digital device used by the patient has been explored primarily in the setting of arrhythmia detection. For example, the randomized controlled Assessment of Remote Heart Rhythm Sampling Using the AliveCor Heart Monitor to Screen for Atrial Fibrillation (REHEARSE-AF) trial showed a significantly higher rate of detection of asymptomatic atrial fibrillation using the single-lead monitor compared with routine care, resulting in appropriate management such as anticoagulation for stroke reduction in this patient population with elevated CHA2DS2-VASc scores.4 The device demonstrated reasonable fidelity as a screening tool, with a study showing a sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 98.5% in detecting atrial fibrillation.5 In a case series of 6 college athletes, the 6-lead device demonstrated the ability to detect otherwise difficult to capture exercise-related arrhythmias and provided a provisional diagnosis that guided treatment in 5 of the 6 athletes. These arrhythmias included atrial fibrillation/flutter and supraventricular tachycardias.6 While capturing accurate data is crucial, the interpretation and further clinical management is even more important, highlighting the need for these technologies to be integrated with the patient’s care team and physician.

Follow-Up

After the diagnosis was established, the patient was switched from metoprolol to verapamil with resolution of her angina.

Conclusions

The current case demonstrates the novel utility of personal ECG devices in aiding in the noninvasive diagnosis of vasospastic angina. Physicians should be aware of this consumer-friendly and economical tool in patients presenting with INOCA and vasospastic angina.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental videos, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

Coronary angiography: RAO caudal view

Coronary angiography: LAO cranial view

Coronary angiography: LAO caudal view

Coronary angiography: LAO cranial view of right coronary artery

References

- 1.Ford T.J., Berry C. How to diagnose and manage angina without obstructive coronary artery disease: lessons from the British Heart Foundation CorMicA trial. Interv Cardiol. 2019;14(2):76–82. doi: 10.15420/icr.2019.04.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford T.J., Stanley B., Good R., et al. Stratified medical therapy using invasive coronary function testing in angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(23 Pt A):2841–2855. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sardella G., Mancone M. Invasive functional test in patients with angina and suspected CAD: search more to learn more. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(23 Pt A):2856–2858. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halcox J.P.J., Wareham K., Cardew A., et al. Assessment of remote heart rhythm sampling using the AliveCor Heart Monitor to screen for atrial fibrillation: the REHEARSE-AF study. Circulation. 2017;136(19):1784–1794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaprutko T, Zaprutko J, Sprakwa J, et al. The comparison of Kardia Mobile and Hartmann Veroval 2 in 1 in detecting first diagnosed atrial fibrillation. Cardiol J. Published online August 6, 2021. https://doi.org/10.5603/CJ.a2021.0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Jewson J.L., Orchard J.W., Semsarian C., et al. Use of a smartphone electrocardiogram to diagnose arrhythmias during exercise in athletes: a case series. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2022;6(4):ytac126. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytac126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Coronary angiography: RAO caudal view

Coronary angiography: LAO cranial view

Coronary angiography: LAO caudal view

Coronary angiography: LAO cranial view of right coronary artery