Abstract

Biochemical and mechanical interactions between cells and the surrounding extracellular matrix influence cell behavior and fate. Mimicking these features in vitro has prompted the design and development of biomaterials, with continuing efforts to improve tailorable systems that also incorporate dynamic chemical functionalities. The majority of these chemistries have been incorporated into synthetic biomaterials, here we focus on modifications of silk protein with dynamic features achieved via enzymatic, “click”, and photo- chemistries. The one-pot synthesis of vinyl sulfone modified silk (SilkVS) can be tuned to manipulate the degree of functionalization. The resultant modified protein-based material undergoes three different gelation mechanisms, enzymatic, “click”, and light-induced, to generate hydrogels for in vitro cell culture. Further, the versatility of this chemical functionality is exploited to mimic cell-ECM interactions via the incorporation of bioactive peptides and proteins or by altering the mechanical properties of the material to guide cell behavior. SilkVS is well-suited for use in in vitro culture, providing a natural protein with both tunable biochemistry and mechanics.

Keywords: Silk, Hydrogels, Click Chemistry, Photochemistry, Fibrosis

Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) regulates and guides cell and tissue fate in vivo.1 The ECM plays an essential role in tissue development and disease progression by providing physical and chemical cues that often change over time (e.g., development, disease, regeneration) to direct cell behavior.2–5 This signaling is present during tissue repair, where injury-induced perturbations in homeostatic processes initiate a cascade of dynamic cell-ECM interactions to restore the tissue to the native state over time.6 In fibrosis, this restorative process goes awry, where cell-ECM interactions perpetuate the disease toward a chronic state through dynamic feedback loops.4,7 Namely, fibroblasts undergo a matrix-driven activation to myofibroblasts, a highly contractile and proliferative phenotype marked by α- smooth muscle actin (αSMA) expression, which has become a pathognomonic for fibrosis.8 The path leading to either healthy or diseased tissue outcomes depends on the dynamic interplay involving matrix composition, biochemistry and mechanical cues, all of which influence cell behavior.9–13 Thus, control of these dynamic tissue features is key when studying the underlying biology or developing in vitro tissue models of a disease.

Numerous biomaterial systems have been developed in an attempt to better capture the ECM microenvironment and to parse out the role of specific biochemical or physical cues in cell fate.9,14,15 The biochemical composition16, mechanical stiffness17, and matrix architecture10 of these materials were tuned to represent healthy and diseased tissue states in order to study biological principles that underly disease progression and tissue development in vitro.15,18 While these materials highlighted the interplay between cells and their local extracellular environment, they often focus on one aspect of these tissue variables, and therefore do not account for the complexity and dynamic changes that occur during disease progression or tissue development.19 Biomaterials that can more fully represent dynamic cell-ECM interactions should offer improved and more reliable in vitro systems for the study of tissue development and disease.20

Polymeric materials capable of undergoing nanoscale changes and responses that emulate native tissue processes have been designed and engineered for use as biomaterials.9,14 Early advancements focused on manipulating network formation and biochemical composition with stimuli such as temperature21, pH22, light 23,24, magnetic fields25–27 or others.28 However, modeling tissue in vitro requires increased spatiotemporal precision than these previous methods provide. Through interdisciplinary advancement, several chemistries have advanced the capabilities of in vitro models.29 Generally, these chemistries are based on mechanisms such as click chemistry12,30–36, photochemistry10,31,32,37–39, supramolecular principles40–45, and biomolecular interactions.46–54

As biomaterials diverge from static cultures toward complex, dynamic systems, diverse chemical functionality and mechanical tunability within a singular system are essential.9,40 While the aforementioned chemistries have largely been limited to synthetic polymers, some natural materials have been chemically modified to contain advanced functionality, such as photocrosslinking57, click chemistry10, or supramolecular crosslinking.58 However, these natural polymers usually are limited in mechanical integrity and versatility, often requiring the use of multicomponent systems.

Silk fibroin (termed silk hereafter) is a natural protein that forms mechanically robust, biocompatible, and versatile biomaterials.59 Silk protein is an amphiphilic, high molecular weight polymer with highly repetitive glycine and alanine (GAGA) hydrophobic regions that are flanked by serine or tyrosines.60,61 This structure controls the unique material properties by guiding self-assembly into β-sheet secondary structures which increase the mechanical strength of the material.62 Past research has exploited this feature to generate hydrogels by inducing β-sheet crystallization to form robust, physically crosslinked networks or by employing enzymes to introduce free radicals on tyrosine side chains, which subsequently form dityrosine crosslinks.63–66 While these features are useful, the structure of silk also limits the capacity to incorporate advanced chemical strategies to aid in the development of dynamic biomaterials for in vitro cell culture systems. There are a few examples of click67–72 or photochemistry73,74 translated to silk, however, these systems target reactive motifs in low abundance such as lysine side chains requiring the addition of a second polymer to increase available reactive sites or high polymer concentrations. Thus far, silk chemistry has been limited to the tyrosine motifs (~5.3 mol% of amino acids) or lysine and acidic side chains (~2 mol% combined) along the backbone.75–79 While useful for representing some physiological ECM features, these chemistries alter the protein structure and the material properties, often rendering silk insoluble with low degrees of functionalization.78,80,81 Alternatively, the serine groups, which account for ~12 mol% of the amino acids, have not been as actively pursued in terms of chemical modifications of silk.82,83

Here, we aimed to introduce advanced chemical functionality to silk by exploiting serine moieties. The synthesis and characterization of silk modified with vinyl sulfone (SilkVS) was investigated. SilkVS can undergo both photocrosslinking and Michael-type “click” chemistry with thiol containing molecules at free vinyl sulfone groups while maintaining the previously established enzymatic reactivity at the tyrosine side chains. The various chemical functionalities provide several bioorthogonal methodologies for modifying the mechanical and biochemical features of the hydrogels formed from the modified silk. These properties are cell compatible and can be exploited to guide cell behavior by incorporating characteristic biochemical features of the ECM. Furthermore, the matrices formed can undergo secondary network formation which results in on-demand mechanical stiffening of the initial network. Examining cell behavior on these SilkVS matrices as a function of matrix stiffening, fibroblasts underwent phenotypic changes corresponding with native cell-ECM interactions.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis Vinyl Sulfone-Modified Silk (SilkVS)

Aqueous silk solutions were prepared as previously described.84 In short, Bombyx mori cocoons (Tajima Shoji Co., Ltd., Yokohama, Japan) were degummed to remove sericin protein by boiling 5g of cut cocoons in 2 L of 0.02 M NaCO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 60 mins followed by thorough rinsing in deionized (DI) water. The degummed fibers were allowed to dry overnight before solubilizing in a 9.3 M LiBr solution at a concentration of 25 %(w/v) for 4 hrs at 60°C. The solution was then dialyzed against DI water using regenerated cellulose dialysis tubing (MWCO: 3,500 Da, Spectra/Por®3 Standard RC Tubing, Spectrum Laboratories Inc., Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA). Over the course of 3 days, the dialysis water was changed 6 times. This solution was then centrifuged to remove any insoluble particulates and the concentration was calculated by measuring the mass of the silk that remained after drying a known volume of aqueous solution.

SilkVS was synthesized by first diluting the aqueous silk solution to 2 %(w/v) in 0.1 M NaOH (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). With constant vigorous stirring by a magnetic stir bar and a pH probe equipped, divinyl sulfone (DVS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was then added to the solution and a 5 min time was started. The volume of DVS was calculated by determining the theoretical serine molar content on the silk which was then multiplied by R=1.25, 2.5, or 5.0 to achieve the moles of DVS and then converted to a volume with the molar mass and density of DVS (Equation (S1)).85 During the reaction, the solution would start as a clear, slightly yellow solution and develop into a clear, slightly brown solution (depending on the degree of functionalization). After 5 mins, the solution was neutralized to pH=7.4 carefully with 10 and 1 M HCl dropwise. Caution was taken to add acid slowly and to ensure pH equilibrium before removing the sample from stirring as pH<7 will induce β-sheet crystallization in silk. To remove any excess DVS, the SilkVS solution was then dialyzed against DI water using regenerated cellulose dialysis tubing (MWCO: 3,500 Da, Spectra/Por®3 Standard RC Tubing, Spectrum Laboratories Inc., Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA) over 3 days with 6 water changes. This purification technique has been established to remove vinyl sulfone and purify chemically modified silk solutions.78,86–89 The purified SilkVS solution was then concentrated to >10 %(w/v) by hanging the tubing in a fume hood and allowing water to evaporate. Functionalization of SilkVS was confirmed by H1 nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in deuterium oxide (D2O) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) by observing a signal at δ= 6.18 corresponding to the vinyl hydrogen (Figure S1).88

Characterization of SilkVS

Protein secondary structure and the degree of functionalization was analyzed by a JASCO FTIR 6200 spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) with a miracle attenuated total reflection germanium crystal. To prepare samples for FTIR, silk solutions were flash frozen at 1 %(w/v) and then lyophilized for two days to produce a solid silk sponge. DVS solutions were prepared in a range of concentrations (0, 0.01,0.025, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0 mM) in DI water. A background of DI water was performed to isolate the signal from the DVS, respectively, in the solution. Spectra of the DVS solutions and solid sponge was obtained by averaging 32 scans with a resolution of 4 cm−1 within the wave number range of 600 to 4000 cm−1 (Figure S3). The secondary structure was observed by comparing the amide I region (1600–1700 cm−1) of unmodified silk (NSF) with SilkVS. The degree of functionalization was quantified using a custom MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) script that normalized the sulfonyl peak signal, determined by taking the integral under the curve (1050–1200 cm−1), to the amide I signal (1600–1700 cm−1). A calibration curve was also created by associating FTIR absorbance at the sulfonyl peak with DVS concentration. This curve was then used to calculate the molar degree of functionalization of vinyl sulfone in a 3 %(w/v) silk solution prepared from reconstituting the lyophilized sponges in DI water (Figure S2).

To determine the molecular weight of the silk, gel electrophoresis was performed according to previous published work.90 Here, 25 μL of 1 %(w/v) unmodified silk (NSF) or SilkVS was mixed with 65 μL of LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, NuPAGE, Waltham, MA, USA) and 10 μL of reducing agent. The solutions were vortexed and then heated at 70°C in a dry heat bath for 10 min. After, 10 μL of each sample was loaded into a Bis-Tris-acetate gel along with two reference ladders Invitrogen, Novex Sharp-pre-stained Protein Standard, Waltham, MA, USA). Gels were then run at 200 V for 30 hr in 1x MES-SDS running buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The gel was then removed and fixed with a solution of 100 mL methanol, 20 mL acetic acid, and 80 mL DI water for 10 min. Colloidal blue stain (55 mL DI water, 20 mL methanol and 20 mL stain A (Invitrogen, Novex, Colloidal Blue Stain Kit, Waltham, MA, USA)) was then added for 15 min with gentle shaking. Then 5 mL of stain B (Invitrogen, Novex, Colloidal Blue Stain Kit, Waltham, MA, USA) was added and stained for 3 hrs with gentle shaking. The gel was then washed 3 times for 1 hr and then overnight with DI water. The gel was then imaged. The molecular weight distributions were determined using ImageJ (1.48v, NIH, USA) software to calculate the pixel intensity as a function of pixel distance across the gel for each well. The standard ladder was used to create a standard curve of molecular weight vs pixel distance. The standard curve was then used to plot the molecular weight distribution for each sample as a function of pixel intensity. The distribution was then fit with a gaussian distribution, and the average molecular weight was determined (n=3).

To quantify the concentration of primary amine and thiol motifs, two colorimetric assays were used. 2,4,6-Trinitrobenzene Sulfonic Acid (TNBSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to quantify free primary amines. TNBSA was diluted 100x to 0.05% (w/v) in 0.2 M Na2CO3 (pH=8.5). SilkVS and NSF was diluted to 0.5 mg/ml. The two solutions were then added at a 1:1 ratio and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. 150 μL were added to a clear 96 well plate and the absorbance at λ=420 nm was measured on a plate reader. Solutions of known lysine concentrations were prepared and analyzed in the same way to create a standard curve correlating absorbance value and lysine content. To quantify thiols, the Ellman’s reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was performed according to manufacturers’ protocol. Briefly, standards of L-cysteine were prepared in reaction buffer (0.1M NaH2PO4, 1mM EDTA, pH=8.0) from a range of 1.5–0 mM. Meanwhile, 4 mg of Ellman’s reagent was dissolved in 1 mL of reaction buffer. Then 250 μL of each standard was mixed with 2.5 mL of reaction buffer and 50 μL of the Ellman’s reagent solution and incubated at room temperature for 15 mins. The absorbance at λ=420 nm was used to generate a standard curve of absorbance as a function of concentration. To determine the reaction kinetics of the thiol-ene chemistry, SilkVS solution was prepared at 7.5 %(w/v) (pH=7.8). 1 mM of l-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the SilkVS solution. Over 30 mins, 250 μL of each sample were periodically removed and added to 50 μL of the Ellman’s reagent solution and 2.5 mL of the reaction buffer. The absorbance at λ=420 nm of each time point was then correlated with a thiol concentration and plotted as a function of time. The reaction kinetics were modeled based on a first-order decay to determine the reaction constants, k.

Hydrogel Formation

Enzymatic crosslinking of silk and SilkVS hydrogels followed the protocol described elsewhere. Briefly, silk solutions were diluted in a 40 mM 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazin-1-yl] ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 5 %(w/v) dextrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) buffer with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The final concentrations of silk and HRP were 3 %(w/v) and 10 U/mL, respectively. Then 10 μL of 1 %(v/v) H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added per 1 mL of the silk precursor solution to achieve a concentration of 0.01% (v/v) H2O2 and initiate gelation. The gel solution was then quickly pipetted into 96 well plates and incubated at 37°C for 3 hrs to allow gelation to go to completion. Michael-type “click” induced crosslinking was facilitated by initially creating a solution of silk at 7.5 %(w/v) in 40 mM HEPES and 5 %(w/v) dextrose (pH=7.8). Meanwhile, a second solution of 100mM dithiothreitrol (DTT) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was prepared in DI H2O. Then, the DTT solution was added to the silk solution at a 1:10 dilution and quickly mixed and aliquoted into molds. The solution was then incubated for 1 hr at 37°C to allow gelation to go to completion. Photocrosslinked hydrogels were prepared by diluting silk solutions to 7.5 %(w/v) in a solution of 0.02 %(w/v) lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 40 mM HEPES, and 5 %(w/v) dextrose shielding the solution from light with aluminum foil. The solution was then pipetted into molds to and then exposed to 400 nm blue light for 2.5 min. The resultant gels were then rinsed 3 times for 30 mins with Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

To prepare the dual crosslinked hydrogels, enzymatic crosslinking was initially performed according to the aforementioned protocol with only SilkVS R=2.5. Here, 40 μL of the precursor solution was pipetted into clear 96 well plates before incubating at 37°C for 3 hours. After incubation, 150 μL of a 0.025 %(w/v) LAP in DI water solution was pipetted onto each gel and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour to facilitate diffusion of the photoinitiator into the hydrogel. Then, the solution was aspirated off the top of the hydrogel and the hydrogels were treated with 400 nm blue light for 2.5 min. The stiffened hydrogels were removed and treated with 1 mM RGD-SH for 1 hr at 37°C, rinsed 3 times for 30 mins with DPBS, followed by 2 additional rinses with media facilitate cell adhesion and remove any remaining photoinitiator.

To prepare the Latent TGF-β1 (LTGF) decorated hydrogels, hydrogels were initially formed via enzymatic crosslinking according to the aforementioned protocol. The hydrogels were removed and treated with 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 40 ng of LTGF dissolved in HD50 at pH 7.6 for 1 hr at 37°C, rinsed 3 times for 30 mins with DPBS, followed by 2 additional rinses with serum containing media to facilitate cell adhesion and remove any remaining reagents.

Mechanical Testing

Rheological properties were measured at 37°C using an ARES HR10/20 rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). For the enzymatic and “click” crosslinking, the rheometer was equipped with a 40 mm stainless steel upper cone and the base was equipped with a temperature-controlled Peltier plate for the enzymatic and “click” crosslinking. A 420 μL aliquot of the hydrogel precursor solution was loaded onto the plate and the cone was lowered 47 μm, respectively. To initiate gelation, 4.2 μL of 1% H2O2 or 42 μL of 100 mM DTT, respectively, was added to the precursor solution during 10 second 100 rad/s precycle. A dynamic time sweep was performed at 1 Hz with a 1% applied strain for 4000 s to determine gelation kinetics and storage moduli followed by dynamic frequency sweeps (0.1–100 rad/s at 1% strain) and strain sweeps (0.1% to failure at 1 Hz) to analyze the elastic properties of the hydrogels. For the photocrosslinking, the rheometer was equipped with a 20 mm stainless steel plate and the base was equipped with the UV plate and connected OmniCure UV lamp calibrate to 37.5 mW/cm2. A 420 μL aliquot of the hydrogel precursor solution was loaded onto the plate and the cone or plate was lowered 1000 um. To initiate the light source was turned on for 2.5 mins. During light exposure, a dynamic time sweep was performed at 1 Hz with a 1% applied strain for 600s to determine gelation kinetics and storage moduli followed by dynamic frequency sweeps (0.1–100 rad/s at 1% strain) and strain sweeps (0.1% to failure at 1 Hz) to analyze the elastic properties of the hydrogels. Rheological properties were measured in the linear elastic region, where the storage modulus follow Newtonian behavior and was independent of applied strain.

Unconfined compression on all samples was performed on a TA Instruments RSA3 Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) between 10 mm stainless steel parallel plates. Hydrogels were placed under a preload of ~0.5g to ensure full surface contact. One load-unload cycles to 30% strain at a rate of 1% s−1 were performed to eliminate artifacts. Stress response and elastic recovery were monitored during a second load-unload cycle at the same strain rate. All moduli were calculated by taking the tangent modulus of the loading phase from 0–10% strain. Hydrogel precursor were cast into 12 mm diameter molds before adding H2O2 and allowing gelation to occur for 3 hr at 37°C. For the photo-stiffened hydrogels, the hydrogels were treated with 0.025% (w/v) LAP in DI water for 1 hr and then exposed to 400 nm blue light for 2.5 min. After, all gels were removed and shaped to 8 mm diameter samples (~2mm height) using a biopsy punch (n=5).

Cell Culture

Human Normal Lung fibroblasts (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and, unless otherwise specified, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) was supplemented into the media, where specified, at 5 ng/mL. Culture media was replaced every three days before passaging. Hydrogels were prepared according to the methods described above; however, the precursor solutions were sterilized with a 0.22 μm sterile filter. Additionally, hydrogels treated with CGRGDS peptide (RGD-SH) (Genscript Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) were incubated in a 1 mM solution in HEPES (pH=7.8) for 1 hr at 37°C followed by 3 rinses with DPBS. All hydrogels from the stiffening experiment were treated with RGD-SH. Cells were dissociated before 5 passages and seeded onto the hydrogels 5,000 cells cm−1. To measure the metabolic activity of the cells on days 1, 3, 5, and 7 the gels were washed with DPBS and the cells were then treated with culture media containing 10% (v/v) AlamarBlue Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated for 3 hours at 37°C. Following incubation, 150 μL aliquots of the supernatant media were transferred into opaque 96 well plates, and the fluorescence signal (ex: 560 nm, em: 590 nm) was measured using a microplate reader. Results were reported as the fold change in signal from day 1 (n=5).

Fluorescent Staining, Microscopy, and Analysis

To monitor the viability of the human lung fibroblasts cultured on the hydrogels, cells were stained with the Live/dead viability kit according to the manufacturers protocol and imaged with a BZ-X700 Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence Corp., Itasca, IL, USA). After incubating the cells with Ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1) and calcein-AM (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 30 mins, cells were rinsed with DPBS and imaged at day 7.

Studies investigating the cellular responses to treatment with RGD-SH were terminated at day 5. Studies investigating the cellular responses to treatment with mechanical stimuli and LTGF were terminated at day 6. At termination, cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 15 min at room temperature. To stain the actin cytoskeleton and nuclei, samples were permeabilized in PBS solution containing Triton X-100 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) (1% w/v) for 15 mins; blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) overnight; and stained simultaneously with phalloidin and 2’-(4-Ethoxyphenyl)-5-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)-2,5’-bi-1H-benzimidazole trihydrochloride (Hoechst 33342) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For immunostaining, samples were permeabilized and blocked as mentioned then incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-αSMA (1:1000; Abcam ab7817, Waltham, MA, USA) for 3 hours followed by donkey anti-mouse AlexaFluor 657 (1:2000; ThermoScientific Waltham, MA, USA) for 3 hours with 3x PBS washes in between. Images were captured using a Leica SPX8 laser scanning confocal microscope with excitation wavelengths 405, 488, and 638 nm. Single cell protein analysis were performed using CellProfiler. Myofibroblasts were denoted as nucleated, F-actin+, αSMA+ cells. αSMA signal quantified as total fluorescence under each mask and thresholded according to the NSF, TGF-β1− controls. A similar method was used to quantify αSMA+ fibroblasts.10 For cell density calculations, Hoechst-stained cell nuclei were thresholded and counted.

Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

For all experiments, cells were seeded on to 35 mm diameter hydrogels at 5,000 cells/cm2. Cells were lysed and RNA isolated using TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) reagent according to the manufacturers protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated from deoxyribonuclease (DNase)-free RNA and amplified. Gene expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT1). Experiments were run with three technical replicates. For a complete list of primers, see Figure S11 (Azenta Life Sciences, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as means ± standard deviations. Sample size was indicated in the respective subsections. One- or two-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) with Tukey’s post hos multiple comparison tests were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad San Diego, CA, USA) unless specified otherwise. (*p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001)

Results

Silk Vinyl Sulfone (SilkVS) Synthesis

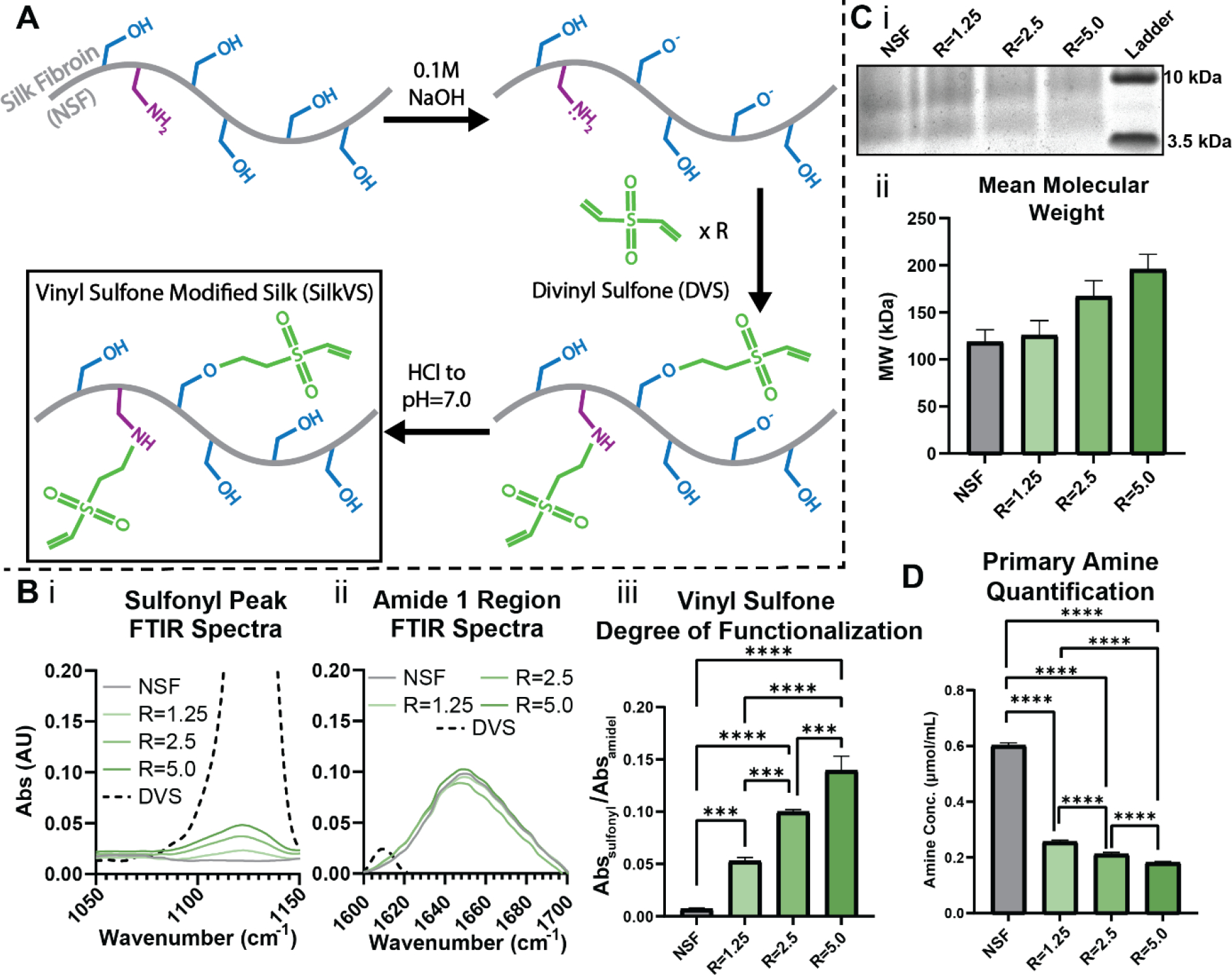

SilkVS was synthesized according to the schematic in Figure 1A. The serine and lysine groups were targeted by a one-pot synthesis under alkaline aqueous conditions. Divinyl sulfone (DVS) was added at 1.25, 2.5 and 5.0 molar excess of the serines85 (R=1.25, 2.5 and 5.0, respectively) to control the degree of functionalization. H1-NMR confirmed the addition of the vinyl group on the protein backbone with the δ = 6.28 ppm88 (Figure S1). Further, the reaction between serine motifs and the divinyl sulfone molecules is corroborated by the peak at δ = 3.5 ppm which corresponds to the ether formed during the reaction of the primary alcohol on serine and the vinyl sulfone group of DVS (Figure 1A, S1). This was further corroborated with Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis, which showed distinct absorbance at 1131 cm−1 corresponding to the vinyl sulfone sulfoxide (S=O) bonds91 (Figure 1Bi). The FTIR spectra also shows absorbance peaks at 1600–1700 cm−1 which indicates the presence of the silk protein92. This region, known as the amide 1 region, appears on the spectra due to the secondary structure of the protein (i.e. random coils, α-helices, β-sheets, etc.). This region of the FTIR spectra confirms that the reaction conditions did not alter the secondary structure of silk (Figure 1Bii, S3). In addition, FTIR spectra showed an increase in the abundance of the vinyl sulfone groups relative to the amide I signal (1600–1700 cm−1) with increasing R-value (Figure 1B, S2, S3). Further, analysis with a 2,4,6-Trinitrobenzene Sulfonic Acid (TNBSA) assay confirmed that primary amines of lysine moieties were consumed during the reaction, and there was a decrease in primary amine content with increasing R-value (Figure 1D). Molecular weight distributions of the native, unmodified silk were compared to the vinyl sulfone modified silk (Figure 1C, S4) to understand the impact of reaction conditions on the molecular weight. There was a slight increase in overall mean molecular weight as a function of R due to the addition of the vinyl sulfone groups (Figure 1Cii).

Figure 1. Synthesis and Characterization of Vinyl Sulfone Modified Silk.

(A) Native, unmodified silk (NSF) was reacted under basic conditions with various molar ratios (R) of divinyl sulfone (DVS) to generate SilkVS. (B) FTIR was used to quantify the degree of functionalization by normalizing the sulfonyl peak (i) to the amide I peak (ii) for each R-value (iii), n=3. (C) SDS-PAGE analysis (i, representative image) of SilkVS and NSF were used to determine the mean molecular weights (ii), n=3. (D) Primary amine content determined using TNBSA assay, n=5. All data presented are means ± SDs.; * p≤0.05, ** p≤0.01, *** p≤0.005, **** p<0.0001.

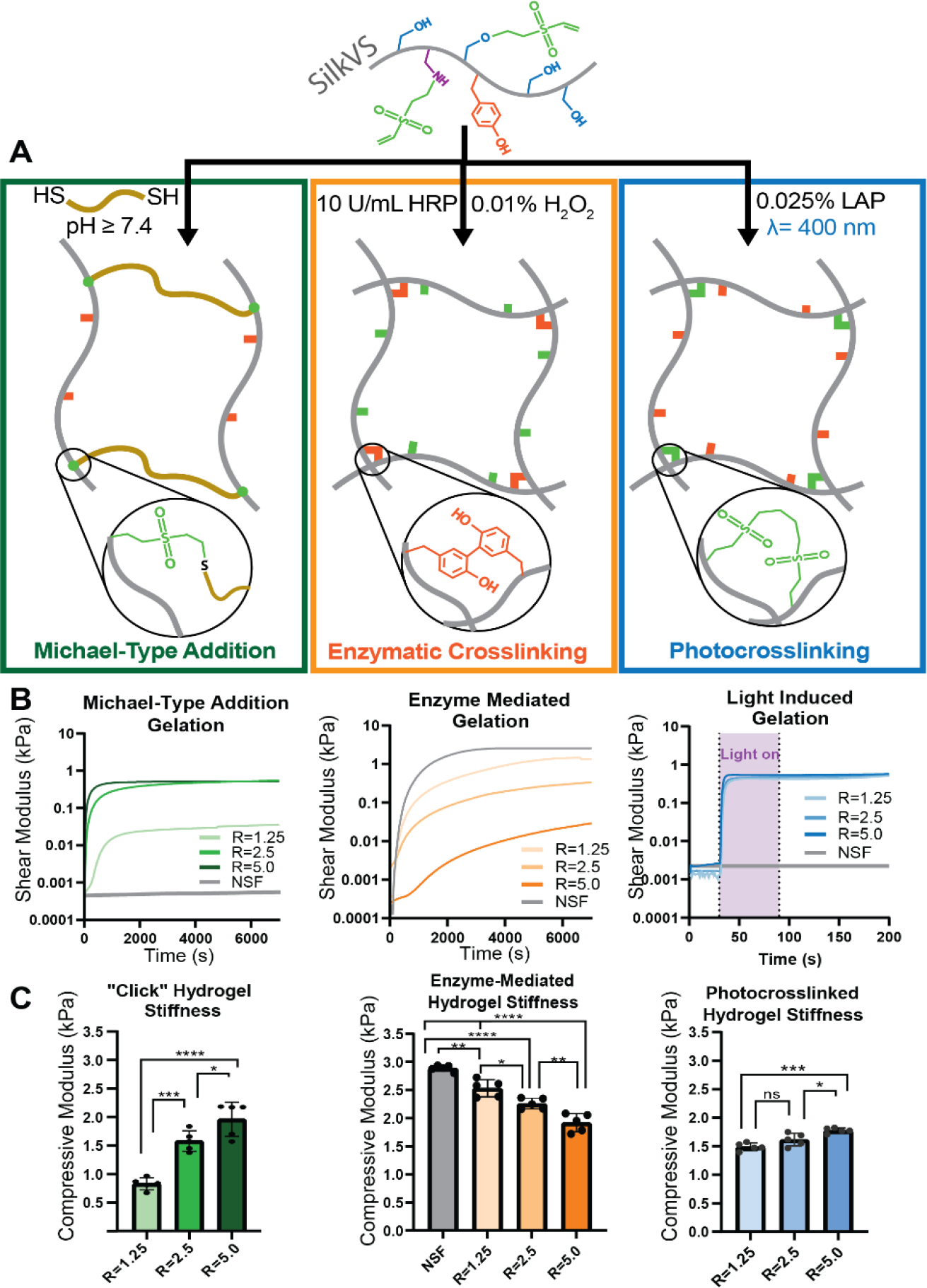

Gelation of SilkVS

SilkVS polymer underwent enzymatic crosslinking based on in situ rheological (Figure 2A, B) and fluorescence (Figure S5) analyses where gelation was induced by the addition of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). There was an impedance of dityrosine crosslink formation compared to the native silk control and the formation of dityrosine bonds occurred at a reduced rate with increasing R-value (Figure S5). In addition to enzymatic crosslinking, the material was also amenable to “click” chemistry as the available vinyl sulfone groups along the silk backbone are susceptible to Michael-type additions with free thiol groups (Figure 2A). A thiol flanked molecule, 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT), was used as a crosslinker to induce network formation. At pH 7.6, the thiols were activated, and gelation occurred in ~15 mins after addition of the crosslinker (Figure 2B). With increasing R-value, there was a reduction in gelation time. Furthermore, the kinetics of the thiol-ene Michael type addition, using L-cysteine as a model monothiol molecule, exhibited a similar increase in reaction rate with increasing R-value (Figure S7).

Figure 2. Multiple Gelation Mechanisms of SilkVS.

(A) SilkVS has the potential to crosslink via three distinct mechanisms: thiol-ene Michael-type addition (green) occurred in the presence of a dithiol molecule (DTT), enzymatically induced dityrosine formation (orange) in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and H2O2, and photocrosslinking (blue) in the presence of a photoinitiator (LAP) and 400nm blue light. (B) The gelation kinetics for each mechanism were tracked via in situ rheometry to monitor shear modulus (n=3). (C) Compressive moduli of the hydrogels were measured (n=5). All data presented are means ± SDs.; * p≤0.05, ** p≤0.01, *** p≤0.005, **** p<0.0001 No significance unless otherwise indicated.

Functionalization of silk with vinyl sulfone also enabled photocrosslinking by exploiting available vinyl groups to undergo free-radical crosslinking in the presence of a photoinitiator and blue light (400 nm) (Figure 2A). Using lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) as the photoinitiator, there was an increase in shear modulus upon exposure to light, which correlated to network formation (Figure 2B). The degree of functionalization guided the rate at which the modulus increased, with larger R-values forming networks at a faster rate.

Mechanical Properties

The enzymatically crosslinked hydrogels had compressive moduli of 1.65 ± 0.06, 1.59 ± 0.08, 1.20 ± 0.17, and 1.08 ± 0.05 kPa for native silk and the R = 1.25, 2.5, and 5.0 hydrogels, respectively (Figure 2C). The increased functionalization of SilkVS impeded dityrosine network formation and therefore reduced the compressive moduli. The opposite trend was found for both thiol-ene crosslinking and photocrosslinking. The hydrogels crosslinked with 0.2 mg/mL LAP and 1 min of blue light (λ=400 nm) exposure had compressive moduli of 1.39 ± 0.068, 1.47 ± 0.11, and 1.78 ± 0.046 kPa for the R = 1.25, 2.5, and 5.0 hydrogels, respectively (Figure 2C). SilkVS was crosslinked via thiol-ene click chemistry upon the addition of 10 mM DTT, the resultant compressive moduli were 0.82 ± 0.11, 1.57 ± 0.18, and 1.95 ± 0.13 kPa for the R = 1.25, 2.5, and 5.0 hydrogels, respectively (Figure 2C). All gels demonstrated elastic behavior as indicated by the rheological frequency sweep and amplitude sweeps (Figure S6).

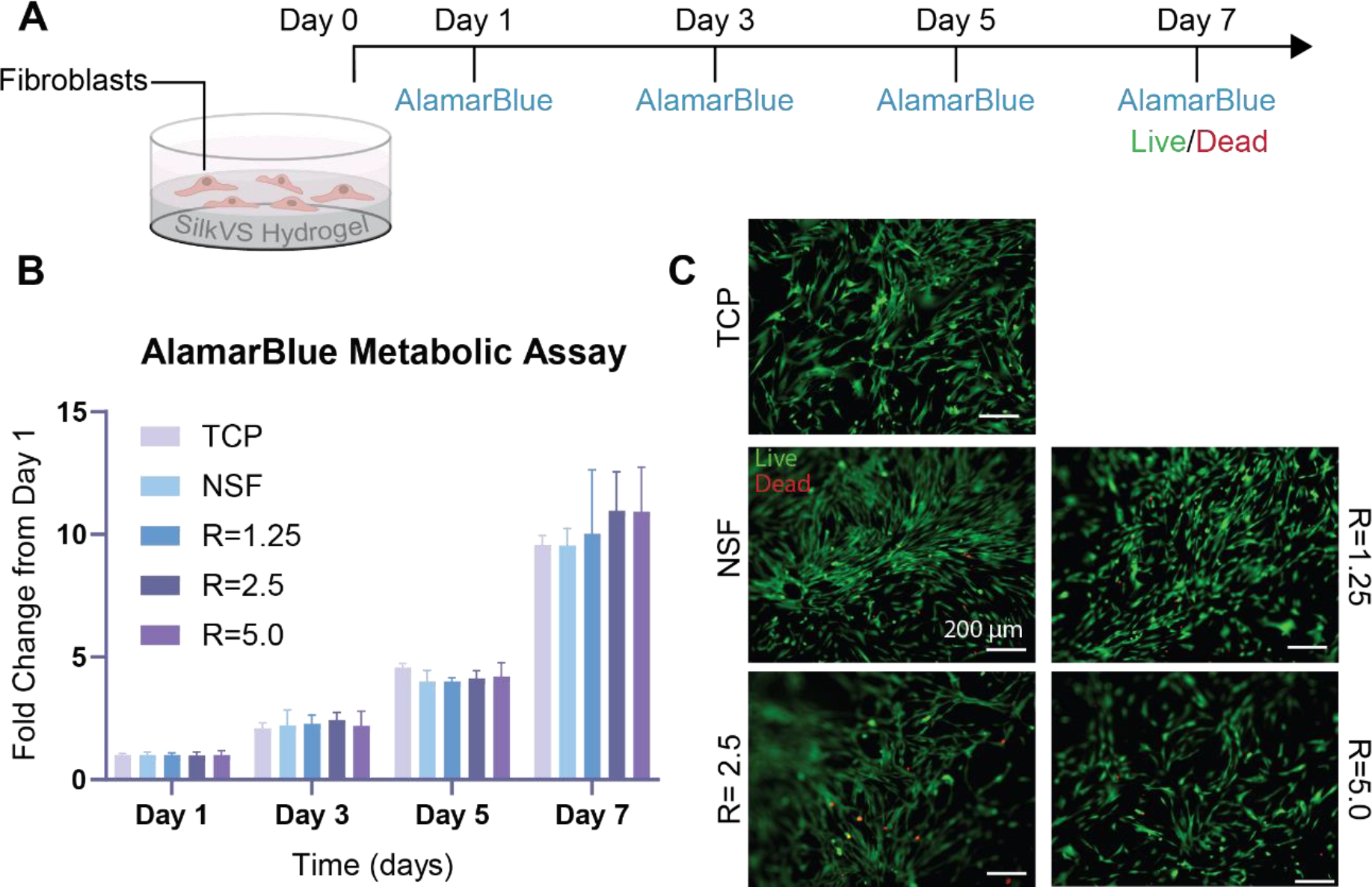

Cytocompatibility

After validating the utility of SilkVS for generating hydrogels, cytocompatibility was assessed via Live/Dead staining and monitoring metabolic activity with AlamarBlue (Figure 3B). All SilkVS material compositions supported increased metabolic activity over 7 days comparable to the unmodified native silk control. Live/dead image analysis showed minimal cell death in all conditions as represented by a low, red ethidium homodimer signal and high, green calcein signal (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. SilkVS Hydrogel Cytocompatibility.

(A) Cytocompatibility was assessed by seeding fibroblasts on enzymatically crosslinking SilkVS and native silk hydrogels and observing metabolic activity and viability. (B) Cell metabolism was assessed using AlamarBlue over 7 days (n=5). (C) Cell viability was measured with fluorescence imaging where live cells were indicated by a green signal and cell death by red signal (C). Images are representative (n=5) All data presented are means ± SDs.; * p≤0.05, ** p≤0.01, *** p≤0.005, **** p<0.0001. No significance unless otherwise indicated.

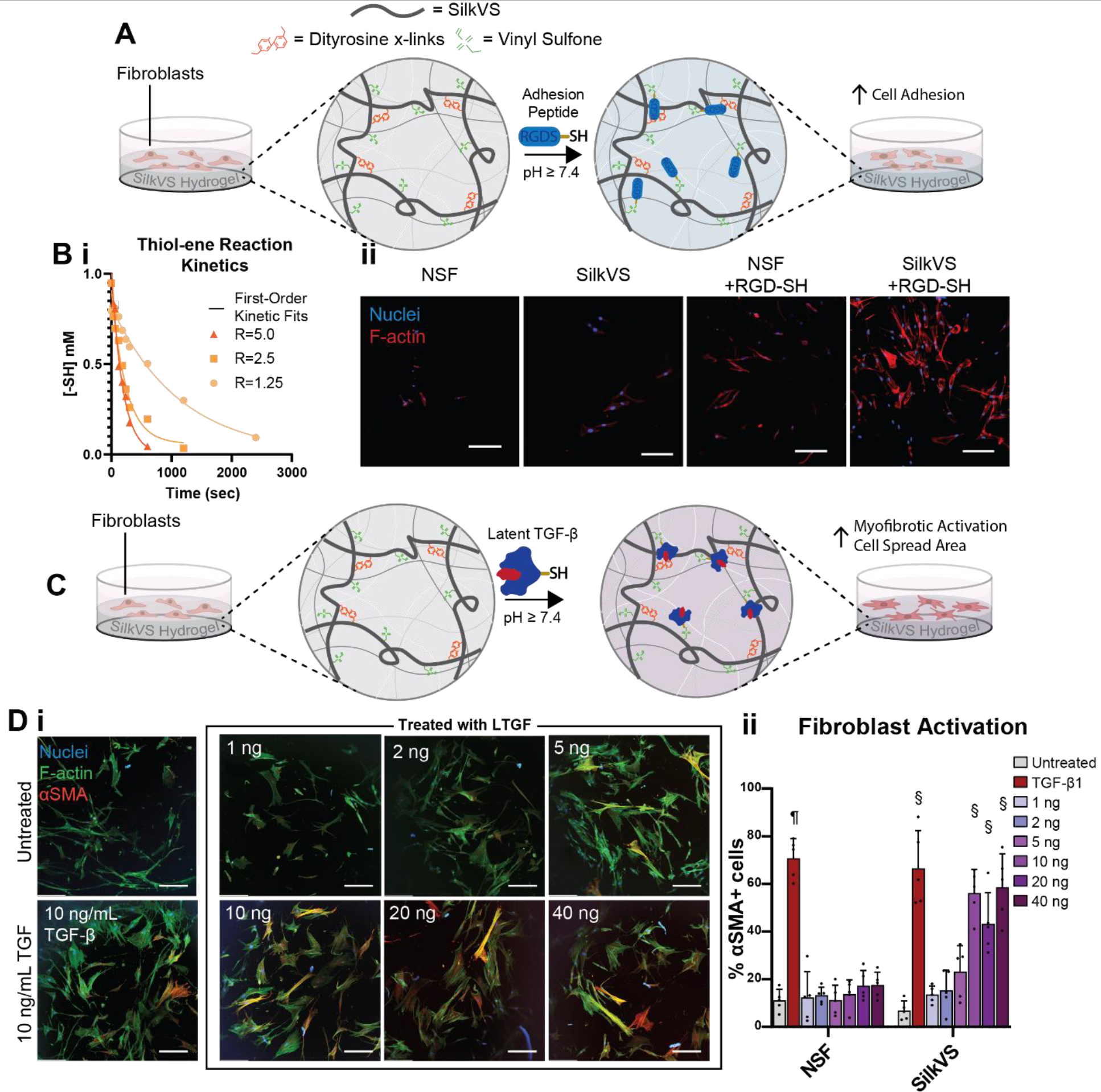

Bioconjugation of SilkVS via thiol-ene “click” chemistry

The materials were engineered to display cell instructive ECM features (bioactive peptides and proteins) (Figure 4A, C). Ellman’s assay was used to characterize the “click” chemistry between the free vinyl groups of SilkVS and available thiol motifs by quantifying the concentration of thiols over time (Figure 4Bi). When mixed with L-cysteine, the SilkVS rapidly consumed the thiol motifs, with the rate dependent on the degree of functionalization of the SilkVS. The profile of thiols in solution was first order with increasing reaction constant, k, with increasing R value (Figure S7). A cell binding peptide flanked by a cysteine group, CGRGDS (denoted RGD-SH), was then covalently bound to the network via the thiol-ene Michael type addition.10 The same thiol quantification was run with RGD-SH to capture reaction kinetics of the peptide with SilkVS (R=2.5) and the kinetic profile was comparable to the L-cysteine profile (Figure S7). When translated to hydrogel culture, the absence of RGD-SH resulted in poor cell binding to the surface of native silk and SilkVS hydrogels. When RGD-SH was added, cell binding improved significantly for both systems. The former showed some cell adhesion at day 5 in culture, while the RGD-SH-SilkVS hydrogels had a comparatively higher cell density at day 5 (Figure 4Bii, S8).

Figure 4. Bioactive Molecules Decorate SilkVS Network to Guide Cell Behavior.

(A) Thiol flanked cell adhesion peptide RGD-SH was displayed in the hydrogel network to guide cell adhesion on the SilkVS hydrogel. (Bi) Thiol-ene reaction kinetics between thiol containing molecules and SilkVS monitored using Elman’s reagent. This chemistry was then used to “click” on RGD motifs to increase cell adhesion as indicated by images of cells on the hydrogel surfaces (ii) (n=5). (C) A more complex and physiologically relevant biomolecule, latent TGF-β1 (LTGF), displayed on the surface at different concentrations. (D) Immunofluorescence imaging used to characterize fibroblast activation on the hydrogels in comparison to untreated and TGF-β1 treated controls (i) (n=5). Images were analyzed to determine the number of activated cells as determined by αSMA+ expression (n=5). Scale bars are 200 μm. All data presented are means ± SDs. Statistics are compared within the same condition group; no significance unless otherwise indicated; § indicates significant from all treatments other than those containing §, p≤0.05; ¶ indicates significant from all conditions, p<0.0001.

The use of RGD-SH peptide provided a proof-of concept for cell control related to cell binding, however more complex biochemical systems were pursued to further mimic features of the ECM. Latent Transforming Growth Factor (LTGF)-β1, a protein complex that stores and releases TGF-β1 in vivo and is implicated in fibrotic disease progression, was employed.2 The protein complex was bound to the SilkVS matrix via available thiol groups on the protein and the response of fibroblasts seeded on the hydrogel matrices was observed (Figure 4C). Cellular responses to hydrogels treated with a range of LTGF concentrations (0.1 ng to 40 ng) were observed. With increasing LTGF concentration, there was an increase in fibroblast myofibrotic activation, quantified by observing increased expression of α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) (Figure 4Di, ii). This myofibrotic activation is a biomarker for fibrosis. The extent of cell activation plateaued after exceeding 10 ng of LTGF (Figure 4Dii).

Mechanical Activation

Stiff hydrogels were formed by generating photoinduced secondary networks. Hydrogels were initially prepared by exploiting the enzymatic crosslinking, followed by the formation of a secondary photocrosslinked network at the vinyl groups with 400 nm light and the photoinitiator LAP (Figure 5A). This secondary network increased the compressive moduli of the hydrogels to 5.32 ± 0.69, 6.29 ± 0.728, and 8.04 ± 0.71 kPa for the R=1.25, 2.5, and 5.0 hydrogels, respectively (Figure 5B). Fibroblasts seeded on the soft untreated SilkVS matrix (R=2.5) showed minimal myofibrotic activation as determined by quantifying the expression of αSMA. In contrast, fibroblasts seeded on the photo-stiffened hydrogels, representative of the mechanics of fibrotic tissue93, supported increased cell spreading and more αSMA expression (Figure 5Ci). Image analysis demonstrated that cells seeded on the stiffer matrices underwent increased myofibrotic activation (~70% of cells were αSMA+) compared to the cells seeded on the softer matrix (~15% αSMA+) (Figure S9). This conclusion was corroborated by RT-qPCR analysis, which showed a significant increase in ACTA2 and COL1A genes associated with fibrosis, in cells exposed to the stiffer hydrogels (Figure 5Cii).

Figure 5. Dual Crosslinked SilkVS Network Alters Mechanical Properties and Activates Fibroblasts.

(A) SilkVS hydrogels undergo secondary network formation upon exposure to light (λ=400 nm) and photoinitiator, LAP, resulting in stiffening of the matrix. (B) The extent of stiffening was characterized with compression testing for all SilkVS R-values (n=5). (C) Fibroblasts seeded on R=2.5 hydrogels and treated with light or TGF-β1 were imaged after 6 days to assess cellular activation by staining for αSMA and counter-staining the nuclei and F-actin (i). Images are representative (n=5). RT-qPCR was performed on cells exposed to the various treatment conditions to characterize gene expression of ACTA2 and COL1A, two genes associated with fibrotic activation normalized to the housekeeping gene HPRT1 (ii) (n=3). Scale bars are 200 μm. All data presented are means ± SDs.; * p≤0.05, ** p≤0.01, *** p≤0.005, **** p<0.0001. No significance unless otherwise indicated.

To assess the interplay of mechanics and biochemical composition on disease progression, similar photostiffening treatments were performed with TGF-β1 supplemented into the growth media. The presence of TGF-β1 resulted in a significant increase in myofibrotic activation in all conditions (Figure 5Ci). When combined with stiffened SilkVS matrices, there was an amplification of this activation; the fold change in gene expression was significantly upregulated for both ACTA2 and COL1A (Figure Cii).

Discussion

The pivotal role of the ECM in tissue development and disease progression continues to be investigated and new tools have been developed to better represent the physiological features of the processes involved.9,55,56 Three-dimensional (3D) biomaterial systems have been integral to capturing cell-ECM interactions in vitro. Recent material systems aim to capture the dynamic properties of tissue development and disease pathology by employing unique chemical strategies that mimic these time-dependent changes during disease progression and provide control over the material properties during these dynamic conditions. Much of these chemistries harness “click”, photo-, or supramolecular chemistries to enable bioorthogonal and dynamic control over the polymer network.19,40,54,56 Here we explored the potential of silk protein-based biomaterial designs to represent biochemical and mechanical features of native ECM in vitro. We selected silk due to its unique chemistry, amphiphilicity, self-assembly features, and formation into materials with robust mechanical properties.

The chemical synthesis of SilkVS followed the schematic in Figure 1A. Under basic conditions, the serine hydroxyl and lysine primary amine side chains were deprotonated forming reactive nucleophiles. In the presence of the electrophile divinyl sulfone (DVS), the nucleophilic alkoxides and primary amines reacted to form vinyl sulfone modified silk (SilkVS). This chemical mechanism has previously been used as a crosslinker in polysaccharide material networks such as hyaluronic acid (HA) or dextran.88,94 However, by tuning the stoichiometry, the reaction can be saturated or terminated before crosslinking occurs, leaving unreacted vinyl sulfone groups for use in subsequent reactions. Moreover, it has been shown that the degree of functionalization can be controlled with three different parameters: time, DVS concentration, and pH.88 An initial validation of the synthesis with several analytical techniques (H1-NMR, FTIR, and TNBSA assay) confirmed that this chemistry can be translated to silk (Figure 1B, D, S1, S2). Then, to avoid prolonged exposure and the risk of protein degradation in alkaline reaction conditions, DVS concentration was varied to tune the final degree of functionalization. Specifically, the value of R, which corresponds to the molar ratio of DVS to serine moieties in the silk backbone, was altered and characterization of the polymer product confirmed that the chemistry was tunable. This is useful as the degree of functionalization can be altered to tune polymer structure which can then be exploited to manipulate the properties of the biomaterials formed (i.e., reactivity, mechanical, bioactivity).

While it was confirmed that vinyl sulfone was successfully conjugated onto the silk backbone, we next set out to confirm the functionality of the newly added motifs. It has been established that the tyrosine motifs that comprise the silk amino acid backbone form crosslinks in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) forming a hydrogel network.95 With the conjugation of vinyl sulfone onto the silk backbone, this enzymatic functionality is expanded, incorporating a reactive motif that has been previously shown to undergo photo- and click chemistries (Figure 2)89. Thiol-ene click crosslinking is useful for in vitro culture systems as it occurs rapidly within the range of physiological pH to ensure cell viability and homogeneity throughout the matrix.56 Alternatively, the light-induced crosslinking allows for rapid crosslinking of the network within seconds of exposure to light. This is useful for in vitro culture systems, as well as for bioprinting ink because light allows for precise spatial control of crosslinking, however it is limited to small-scale material fabrication since absorption will increase with increasing penetration depth.96 When confirming the enzyme-mediated reactivity of SilkVS, it was shown that the tyrosine motifs are still available and functional. Interestingly, with increasing R-value, there was an observed inhibition of the gelation and reduction in the compressive moduli of the hydrogels (Figure 2B, C, S5). This suggests that, while tyrosine moieties are not involved in the chemical synthesis, their functionality is altered in the resultant SilkVS molecules. This could be attributed to steric hinderances or quenching of the free radicals by the added vinyl sulfone motifs. Additionally, this slowed crosslinking allows for greater polymer chain rearrangement which would not only impact the final hydrogel mechanical properties, but also potentially alter the availability of the vinyl sulfone groups in the hydrogel network as they are not homogenously distributed across the silk backbone. Nonetheless, SilkVS formed a hydrogel in all conditions in the presence of HRP and H2O2, with minimal impact on hydrogel mechanics (Figure 1C) confirming the modified protein maintains the previously established reactivity. The inhibition of enzymatic gelation contrasts with the click and photo-induced gelation of SilkVS both of which show accelerated gelation kinetics and increased mechanical properties with increasing R-value (Figure 2). The resultant hydrogels had similar mechanics across SilkVS degrees of modification and showed elastic behavior (Figure S6). Together, these data confirm that the conjugated vinyl sulfone groups are functional and demonstrate that the hydrogel properties can be tuned by controlling the degree of functionalization.

After validating the chemical synthesis and functionality of the materials, the feasibility of this material for in vitro cell culture was determined. Metabolic assessments and Live/Dead imaging of cells seeded on the hydrogel matrices confirmed that SilkVS was cytocompatible, regardless of the degree of functionalization, and provided a viable material for in vitro cell culture (Figure 3). To ensure high vinyl sulfone functionality with practical enzymatic crosslinking times, R=2.5 was selected for all cell culture experiments.

Next, to understand the potential of SilkVS for modeling biochemical features of the ECM in vitro, the functional polymer was exploited to bioorthogonally conjugate bioactive molecules onto the protein network. By exploiting the available vinyl sulfone motifs post-enzymatic crosslinking, the hydrogel network was decorated with RGD-SH peptides to control cell adhesion (Figure 4A). RGD is an amino acid sequence found in several biomolecules like fibronectin, where it is was first discovered, and it is recognized by integrins on the surface of cells promoting cell adhesion97. When cultured without serum, cells minimally adhered to the surfaces as silk contains no native cell binding sites along its backbone.59 Upon the addition of the RGD-SH peptide, there was increased cell adhesion to both the SilkVS and native silk matrices (Figure 4Bi). While the latter is guided by peptide adsorption to the protein matrix, as shown by the reduced cell density, the former is a result of covalent binding to the SilkVS network at the vinyl sulfone motifs resulting in higher cell density (Figure 4Bii, S8). This provided a demonstration of the ability to manipulate cell behavior by exploiting SilkVS chemistry to guide cell adhesion by displaying cell binding motifs, RGD-SH, along the polymer backbone.

To further elaborate on the potential of this system to mimic biochemical dynamics of disease, we exploited the thiol-ene chemistry to covalently bind latent transforming growth factor-β1 complex (LTGF) to the extracellular network (Figure 4C). LTGF is a bioactive protein complex found in the ECM where a latency-associated peptide binds TGF-β1 sequestering the growth factor and releasing it upon injury.98–100 While TGF-β1 is essential for homeostatic wound healing, it is also a key biochemical factor in fibrotic diseases where it induces myofibrotic activation.101 This growth factor is canonically supplemented in its active form into growth medium to study fibrotic activation in vitro; however, this supplementation is limited in representing the native cell-ECM interactions that guide growth factor release and activation.101,102 Further, the presence of excess active TGF-β1 is implicated in diseases suggesting supplementation in vitro may cause undesirable study outcomes.103,104 By incorporating LTGF into the matrix we aimed to better capture disease dynamics and cell-ECM interactions, highlighting the potential of this material network for use for in vitro disease models. When seeded onto the SilkVS matrix decorated with LTGF, fibroblasts underwent a myofibrotic activation, indicated by the increased production of αSMA (Figure 4D). This response was not observed in the silk controls treated with the complex. This suggested that the growth factor binds to the network allowing cells to then interact with the ECM bound LTGF, resulting in the release of the TGF-β1 which then induces myofibrotic activation. This activation was dose-dependent, as αSMA expression increased with increasing LTGF. Interestingly, at LTGF concentrations above 10 ng per well, the cellular behavior appears to be independent of LTGF concentration (Figure Dii), suggesting that the cellular response was saturated. These results highlight the chemical functionality of the material which can be exploited to engineer in vitro systems that recapitulate native cell-ECM interactions.

We next set out to demonstrate the potential of the material for parsing out mechanical contributions of the ECM on physiological processes. Utilizing fibrosis as a model physiological process, we set out to capture the dynamic mechanical environment of the diseased tissue. A hallmark of fibrotic tissue is the formation of stiff scar tissue which stimulates stromal fibroblasts to undergo a phenotypic transition to the more contractile and active myofibroblasts marked by αSMA contractile fibers.14,105 By exploiting the various crosslinking modalities available to SilkVS networks, we demonstrated that the material system captured the mechanical dynamics of diseases (Figure 5B). Employing enzymatic crosslinking to generate a soft hydrogel reminiscent of healthy lung tissue mechanics and a secondary photocrosslinking to generate a stiff hydrogel that captures fibrotic tissue mechanics, changes in the matrix mechanics were utilized to replicate the mechanical activation of fibroblasts.10,14,17 It is worth noting that both RGD-SH bioconjugation and photostiffening exploit the same reactive sites potentially impacting one another, so all photostiffening was performed prior to bioconjugation to preserve the material properties of the photosstiffened hydrogels. Nonetheless, fibroblasts underwent increased myofibrotic differentiation when cultured on the stiff light-treated substrates, whereas fibroblasts cultured on the soft untreated SilkVS and native silk hydrogels remained largely quiescent and inactivated (Figure 5Ci, S10). This was corroborated by assessing the expression of fibrotic genes ACTA2 and COL1A, which showed that cells cultured on the dual crosslinked matrix underwent myofibrotic activation. Interestingly, when the biochemical contribution of the ECM was also considered by supplementing TGF-β1 into the mechanically dynamic system, we noted increased expression of both fibrotic genes (Figure 5Cii). This suggested that the ECM biochemical composition works synergistically with the mechanical stimuli to exacerbate this diseased state. This conclusion highlights the importance of considering both the ECM biochemical composition and mechanical stimuli when designing an in vitro tissue model. Furthermore, the results suggest the potential of SilkVS for in vitro studies by providing a material system to control both the biochemical and mechanical extracellular environment.

This work outlines a “one-pot” chemical synthesis that exploits the relatively abundant serine motifs in silk to decorate the protein with vinyl sulfone groups enabling both photocrosslinking and thiol-ene “click” chemistry without inhibiting the enzymatic crosslinking potential of the protein. While there have been a few examples of click67–72 or photochemistry73,74 translated to silk, these systems target low abundant reactive motifs requiring the addition of a second polymer to increase available reactive sites or high polymer concentrations that are not feasible for in vitro cell encapsulation or bioprinting. This work provides the first example of a purely silk-based hydrogel system that employs click chemistry to form a hydrogel network. The resultant material exploits several crosslinking modalities to engineer the mechanical and biochemical composition of hydrogel scaffolds, with implication towards future three-dimensional studies and bioprinting fabrication techniques. When utilized as an in vitro culture system, the functionality lends itself to guiding cell behavior and parsing out the influence of different features of the extracellular environment, such as biochemistry and mechanics, on physiological processes with a single material system.

The versatility of silk-based materials and the results above contribute to the advancement of in vitro tissue modelling and tissue engineering, particularly toward developing tissue models of diseases where dynamic and complex cell-ECM interactions significantly impact outcomes, as in fibrosis. Analogous systems like poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) or HA have established similar chemical modalities, however they require multistep syntheses involving harsh processing and result in material systems that are limited by their biocompatibility or mechanical integrity.43,106 Herein, we strengthen silk as a viable biomaterial scaffold by developing a novel, facile chemical synthesis that imparts a range of functionality to the protein, suggesting a role in next generation biomaterials, engineered tissues and in vitro tissue models.

Conclusions

Silk was modified at serine and lysine side chains to incorporate vinyl sulfone functional groups. The vinyl sulfone modified silk (SilkVS) underwent hydrogel network formation via enzymatic, thiol-ene “click”, and photochemistries. The multifunctional network was amendable to selective decoration with thiol containing molecules and dual network formation was observed upon exposure to blue light and a photoinitiator. During cell culture, the material supported cell growth and also allowed for control of cell behavior by altering the biochemical and mechanical environment. The results point to the novel utility of SilkVS for in vitro cell culture as the introduced functionality allows for bioorthogonal chemistry that can be used to mimic biochemical and mechanical environments of tissues during disease progression and development. Future use of this material can exploit this versatility to represent several tissues features in a single system allowing researchers to parse out the synergistic biological implications of the ECM with high fidelity. Additionally, SilkVS has the potential for use in bioprinting of soft tissue where the photocrosslinking capabilities can be exploited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the NIH (P41EB027062) for support of this work. The authors thank Rebecca Hershman, Sawnaz Shaidani, Olivia Foster, and Carmen Preda-Rucsanda for their technical help. For the use of their rheometer, the authors acknowledge the Harvard University Center for Nanoscale Systems (CNS); a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Network (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation under NSF award no. ECCS-2025158.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT Author Statement

Thomas Falcucci: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Visualization, Project Administration Margaret Radke: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing-Review & Editing Jugal Kishore Sahoo: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization Onur Hasturk: Conceptualization, Writing-Review & Editing David L Kaplan: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing-Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data and Materials availability:

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

References

- 1.Rosales AM & Anseth KS The design of reversible hydrogels to capture extracellular matrix dynamics. Nature Reviews Materials 1, 15012, doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2015.12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinz B The extracellular matrix and transforming growth factor-beta1: Tale of a strained relationship. Matrix Biol 47, 54–65, doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.05.006 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garamszegi N et al. Extracellular matrix-induced transforming growth factor-beta receptor signaling dynamics. Oncogene 29, 2368–2380, doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.514 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C & Brown RA Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3, 349–363, doi: 10.1038/nrm809 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pakshir P & Hinz B The big five in fibrosis: Macrophages, myofibroblasts, matrix, mechanics, and miscommunication. Matrix Biol 68–69, 81–93, doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.01.019 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson NC, Rieder F & Wynn TA Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature 587, 555–566, doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2938-9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saucerman JJ, Tan PM, Buchholz KS, McCulloch AD & Omens JH Mechanical regulation of gene expression in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cardiol 16, 361–378, doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0155-8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pakshir P et al. The myofibroblast at a glance. Journal of Cell Science 133, jcs227900, doi: 10.1242/jcs.227900 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lou J & Mooney DJ Chemical strategies to engineer hydrogels for cell culture. Nature Reviews Chemistry 6, 726–744, doi: 10.1038/s41570-022-00420-7 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matera DL et al. Microengineered 3D pulmonary interstitial mimetics highlight a critical role for matrix degradation in myofibroblast differentiation. Sci Adv 6, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb5069 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia Y et al. The Plasticity of Nanofibrous Matrix Regulates Fibroblast Activation in Fibrosis. Advanced Healthcare Materials n/a, 2001856, doi: 10.1002/adhm.202001856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Caprio N & Bellas E Collagen Stiffness and Architecture Regulate Fibrotic Gene Expression in Engineered Adipose Tissue. Adv Biosyst 4, e1900286, doi: 10.1002/adbi.201900286 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y et al. ECM-inspired micro/nanofibers for modulating cell function and tissue generation. Science Advances 6, eabc2036, doi:doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc2036 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson MD, Burdick JA & Wells RG Engineered Biomaterial Platforms to Study Fibrosis. Adv Healthc Mater, e1901682, doi: 10.1002/adhm.201901682 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bretherton RC & DeForest CA The Art of Engineering Biomimetic Cellular Microenvironments. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01549 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wishart AL et al. Decellularized extracellular matrix scaffolds identify full-length collagen VI as a driver of breast cancer cell invasion in obesity and metastasis. Science Advances 6, eabc3175, doi:doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc3175 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker CJ et al. Author Correction: Nuclear mechanosensing drives chromatin remodelling in persistently activated fibroblasts. Nat Biomed Eng, doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00748-3 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker CJ et al. Extracellular matrix stiffness controls cardiac valve myofibroblast activation through epigenetic remodeling. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 7, e10394, doi: 10.1002/btm2.10394 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badeau BA & DeForest CA Programming Stimuli-Responsive Behavior into Biomaterials. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 21, 241–265, doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-060418-052324 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Félix Vélez NE, Gorashi RM & Aguado BA Chemical and molecular tools to probe biological sex differences at multiple length scales. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 10, 7089–7098, doi: 10.1039/D2TB00871H (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klouda L & Mikos AG Thermoresponsive hydrogels in biomedical applications. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 68, 34–45, doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.02.025 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang S et al. A pH-responsive supramolecular polymer gel as an enteric elastomer for use in gastric devices. Nature Materials 14, 1065–1071, doi: 10.1038/nmat4355 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosales AM, Mabry KM, Nehls EM & Anseth KS Photoresponsive elastic properties of azobenzene-containing poly(ethylene-glycol)-based hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 16, 798–806, doi: 10.1021/bm501710e (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu L et al. Cyclic stiffness modulation of cell-laden protein–polymer hydrogels in response to user-specified stimuli including light. Advanced Biosystems 2, 1800240 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szabo D, Czako-Nagy II, Zrinyi M & Vertes A Magnetic and Mossbauer Studies of Magnetite-Loaded Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogels. J Colloid Interface Sci 221, 166–172, doi: 10.1006/jcis.1999.6572 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filipcsei G, Feher J & Zrinyi M Electric field sensitive neutral polymer gels. J Mol Struct 554, 109–117, doi:Doi 10.1016/S0022-2860(00)00564-0 (2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zlotnick HM et al. Magneto-Driven Gradients of Diamagnetic Objects for Engineering Complex Tissues. Adv Mater 32, e2005030, doi: 10.1002/adma.202005030 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosales AM, Vega SL, DelRio FW, Burdick JA & Anseth KS Hydrogels with Reversible Mechanics to Probe Dynamic Cell Microenvironments. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 56, 12132–12136, doi: 10.1002/anie.201705684 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Correa S et al. Translational Applications of Hydrogels. Chemical Reviews 121, 11385–11457, doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01177 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caliari SR et al. Gradually softening hydrogels for modeling hepatic stellate cell behavior during fibrosis regression. Integrative Biology 8, 720–728, doi: 10.1039/c6ib00027d (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caliari SR et al. Stiffening hydrogels for investigating the dynamics of hepatic stellate cell mechanotransduction during myofibroblast activation. Scientific Reports 6, 21387, doi: 10.1038/srep21387 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shadish JA & DeForest CA Site-Selective Protein Modification: From Functionalized Proteins to Functional Biomaterials. Matter 2, 50–77, doi: 10.1016/j.matt.2019.11.011 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shadish JA, Strange AC & DeForest CA Genetically Encoded Photocleavable Linkers for Patterned Protein Release from Biomaterials. J Am Chem Soc 141, 15619–15625, doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b07239 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma H, Caldwell AS, Azagarsamy MA, Gonzalez Rodriguez A & Anseth KS Bioorthogonal click chemistries enable simultaneous spatial patterning of multiple proteins to probe synergistic protein effects on fibroblast function. Biomaterials 255, 120205, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120205 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrou CL et al. Clickable decellularized extracellular matrix as a new tool for building hybrid-hydrogels to model chronic fibrotic diseases in vitro. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 8, 6814–6826, doi: 10.1039/D0TB00613K (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gramlich WM, Kim IL & Burdick JA Synthesis and orthogonal photopatterning of hyaluronic acid hydrogels with thiol-norbornene chemistry. Biomaterials 34, 9803–9811, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.089 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Killaars AR et al. Extended Exposure to Stiff Microenvironments Leads to Persistent Chromatin Remodeling in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Adv Sci (Weinh) 6, 1801483, doi: 10.1002/advs.201801483 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silver JS et al. Injury-mediated stiffening persistently activates muscle stem cells through YAP and TAZ mechanotransduction. Science Advances 7, eabe4501, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe4501 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeForest CA & Tirrell DA A photoreversible protein-patterning approach for guiding stem cell fate in three-dimensional gels. Nat Mater 14, 523–531, doi: 10.1038/nmat4219 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Addonizio CJ, Gates BD & Webber MJ Supramolecular “Click Chemistry” for Targeting in the Body. Bioconjugate Chemistry 32, 1935–1946, doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.1c00326 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoque J, Sangaj N & Varghese S Stimuli-Responsive Supramolecular Hydrogels and Their Applications in Regenerative Medicine. Macromolecular Bioscience 19, 1800259, doi: 10.1002/mabi.201800259 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen G & Jiang M Cyclodextrin-based inclusion complexation bridging supramolecular chemistry and macromolecular self-assembly. Chemical Society Reviews 40, 2254–2266, doi: 10.1039/C0CS00153H (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loebel C, Rodell CB, Chen MH & Burdick JA Shear-thinning and self-healing hydrogels as injectable therapeutics and for 3D-printing. Nature Protocols 12, 1521–1541, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.053 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webber MJ, Appel EA, Meijer EW & Langer R Supramolecular biomaterials. Nature Materials 15, 13–26, doi: 10.1038/nmat4474 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rizwan M, Baker AEG & Shoichet MS Designing Hydrogels for 3D Cell Culture Using Dynamic Covalent Crosslinking. Advanced Healthcare Materials 10, 2100234, doi: 10.1002/adhm.202100234 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni S et al. Recent Progress in Aptamer Discoveries and Modifications for Therapeutic Applications. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 13, 9500–9519, doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c05750 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang D, Hu Y, Liu P & Luo D Bioresponsive DNA Hydrogels: Beyond the Conventional Stimuli Responsiveness. Accounts of Chemical Research 50, 733–739, doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00581 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hammer JA & West JL Dynamic Ligand Presentation in Biomaterials. Bioconjug Chem 29, 2140–2149, doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00288 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sui Z, King WJ & Murphy WL Protein-Based Hydrogels with Tunable Dynamic Responses. Advanced Functional Materials 18, 1824–1831, doi: 10.1002/adfm.200701288 (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lutolf MP et al. Synthetic Matrix Metalloproteinase-Sensitive Hydrogels for the Conduction of Tissue Regeneration: Engineering Cell-Invasion Characteristics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 5413–5418 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turk BE, Huang LL, Piro ET & Cantley LC Determination of protease cleavage site motifs using mixture-based oriented peptide libraries. Nature Biotechnology 19, 661–667, doi: 10.1038/90273 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levin A et al. Biomimetic peptide self-assembly for functional materials. Nature Reviews Chemistry 4, 615–634, doi: 10.1038/s41570-020-0215-y (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Z et al. Programmable integrin and N-cadherin adhesive interactions modulate mechanosensing of mesenchymal stem cells by cofilin phosphorylation. Nature Communications 13, 6854, doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34424-0 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Speidel AT, Grigsby CL & Stevens MM Ascendancy of semi-synthetic biomaterials from design towards democratization. Nature Materials 21, 989–992, doi: 10.1038/s41563-022-01348-5 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muir VG & Burdick JA Chemically Modified Biopolymers for the Formation of Biomedical Hydrogels. Chem Rev 121, 10908–10949, doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00923 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hui E, Sumey JL & Caliari SR Click-functionalized hydrogel design for mechanobiology investigations. Molecular Systems Design & Engineering 6, 670–707, doi: 10.1039/D1ME00049G (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Batalov I, Stevens KR & DeForest CA Photopatterned biomolecule immobilization to guide three-dimensional cell fate in natural protein-based hydrogels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014194118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daly AC, Davidson MD & Burdick JA 3D bioprinting of high cell-density heterogeneous tissue models through spheroid fusion within self-healing hydrogels. Nature Communications 12, 753, doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21029-2 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li C et al. Design of biodegradable, implantable devices towards clinical translation. Nature Reviews Materials 5, 61–81, doi: 10.1038/s41578-019-0150-z (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang W, Ling S, Li C, Omenetto FG & Kaplan DL Silkworm silk-based materials and devices generated using bio-nanotechnology. Chemical Society Reviews 47, 6486–6504, doi: 10.1039/C8CS00187A (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou CZ et al. Silk fibroin: structural implications of a remarkable amino acid sequence. Proteins 44, 119–122, doi: 10.1002/prot.1078 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qi Y et al. A Review of Structure Construction of Silk Fibroin Biomaterials from Single Structures to Multi-Level Structures. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, 237 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Partlow BP et al. Highly tunable elastomeric silk biomaterials. Adv Funct Mater 24, 4615–4624, doi: 10.1002/adfm.201400526 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Partlow BP, Applegate MB, Omenetto FG & Kaplan DL Dityrosine Cross-Linking in Designing Biomaterials. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2, 2108–2121, doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00454 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng H & Zuo B Functional silk fibroin hydrogels: preparation, properties and applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 9, 1238–1258, doi: 10.1039/D0TB02099K (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chakraborty J, Mu X, Pramanick A, Kaplan DL & Ghosh S Recent advances in bioprinting using silk protein-based bioinks. Biomaterials 287, 121672, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121672 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao H et al. Decoration of silk fibroin by click chemistry for biomedical application. Journal of Structural Biology 186, 420–430, doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.02.009 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harvey D, Bardelang P, Goodacre SL, Cockayne A & Thomas NR Antibiotic Spider Silk: Site-Specific Functionalization of Recombinant Spider Silk Using “Click” Chemistry. Advanced Materials 29, 1604245, doi: 10.1002/adma.201604245 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang X et al. Surface Modification of Bombyx mori Silk Fibroin Film via Thiol-ene Click Chemistry. Processes 8, 498 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang X et al. Chemical modification of Bombyx mori silk fibers with vinyl groups for thiol-ene click chemistry. BMC Chemistry 13, 114, doi: 10.1186/s13065-019-0630-7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liang J, Zhang X, Chen Z, Li S & Yan C Thiol–Ene Click Reaction Initiated Rapid Gelation of PEGDA/Silk Fibroin Hydrogels. Polymers 11, 2102 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ryu S et al. Dual mode gelation behavior of silk fibroin microgel embedded poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 4, 4574–4584, doi: 10.1039/C6TB00896H (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim SH et al. 3D bioprinted silk fibroin hydrogels for tissue engineering. Nature Protocols 16, 5484–5532, doi: 10.1038/s41596-021-00622-1 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mu X, Sahoo JK, Cebe P & Kaplan DL Photo-Crosslinked Silk Fibroin for 3D Printing. Polymers 12, 2936 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murphy AR & Kaplan DL Biomedical applications of chemically-modified silk fibroin. Journal of Materials Chemistry 19, 6443–6450, doi: 10.1039/B905802H (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hausken KG et al. Quantitative Functionalization of the Tyrosine Residues in Silk Fibroin through an Amino-Tyrosine Intermediate. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 223, 2200119, doi: 10.1002/macp.202200119 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Choi J, McGill M, Raia NR, Hasturk O & Kaplan DL Silk Hydrogels Crosslinked by the Fenton Reaction. Adv Healthc Mater 8, e1900644, doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900644 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hasturk O, Jordan KE, Choi J & Kaplan DL Enzymatically crosslinked silk and silk-gelatin hydrogels with tunable gelation kinetics, mechanical properties and bioactivity for cell culture and encapsulation. Biomaterials 232, 119720, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119720 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hasturk O, Sahoo JK & Kaplan DL Synthesis and Characterization of Silk Ionomers for Layer-by-Layer Electrostatic Deposition on Individual Mammalian Cells. Biomacromolecules 21, 2829–2843, doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.0c00523 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murphy AR, St John P & Kaplan DL Modification of silk fibroin using diazonium coupling chemistry and the effects on hMSC proliferation and differentiation. Biomaterials 29, 2829–2838, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.039 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McGill M, Grant JM & Kaplan DL Enzyme-Mediated Conjugation of Peptides to Silk Fibroin for Facile Hydrogel Functionalization. Ann Biomed Eng, doi: 10.1007/s10439-020-02503-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heichel DL & Burke KA Enhancing the Carboxylation Efficiency of Silk Fibroin through the Disruption of Noncovalent Interactions. Bioconjugate Chemistry 31, 1307–1312, doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00168 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ju J, Hu N, Cairns DM, Liu H & Timko BP Photo–cross-linkable, insulating silk fibroin for bioelectronics with enhanced cell affinity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 15482–15489, doi:doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003696117 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rockwood DN et al. Materials fabrication from Bombyx mori silk fibroin. Nature protocols 6, 1612 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhou CZ et al. Fine organization of Bombyx mori fibroin heavy chain gene. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 2413–2419, doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.2413 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hasturk O et al. Cytoprotection of Human Progenitor and Stem Cells through Encapsulation in Alginate Templated, Dual Crosslinked Silk and Silk–Gelatin Composite Hydrogel Microbeads. Advanced Healthcare Materials 11, 2200293, doi: 10.1002/adhm.202200293 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sahoo JK et al. Sugar Functionalization of Silks with Pathway-Controlled Substitution and Properties. Advanced Biology 5, 2100388, doi: 10.1002/adbi.202100388 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yu Y & Chau Y One-Step “Click” Method for Generating Vinyl Sulfone Groups on Hydroxyl-Containing Water-Soluble Polymers. Biomacromolecules 13, 937–942, doi: 10.1021/bm2014476 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Davidson CD et al. Myofibroblast activation in synthetic fibrous matrices composed of dextran vinyl sulfone. Acta Biomater 105, 78–86, doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.01.009 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sahoo JK et al. Silk degumming time controls horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed hydrogel properties. Biomaterials Science 8, 4176–4185, doi: 10.1039/D0BM00512F (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ellzy MW, Jensen JO & Kay JG Vibrational frequencies and structural determinations of di-vinyl sulfone. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 59, 867–881, doi: 10.1016/S1386-1425(02)00239-1 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hu X, Kaplan D & Cebe P Determining Beta-Sheet Crystallinity in Fibrous Proteins by Thermal Analysis and Infrared Spectroscopy. Macromolecules 39, 6161–6170, doi: 10.1021/ma0610109 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sundarakrishnan A, Chen Y, Black LD, Aldridge BB & Kaplan DL Engineered cell and tissue models of pulmonary fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 129, 78–94, doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.12.013 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khunmanee S, Jeong Y & Park H Crosslinking method of hyaluronic-based hydrogel for biomedical applications. J Tissue Eng 8, 2041731417726464, doi: 10.1177/2041731417726464 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Raia NR et al. Enzymatically crosslinked silk-hyaluronic acid hydrogels. Biomaterials 131, 58–67, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.03.046 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]