Abstract

Background: Despite safety and efficacy of medications for opioid use disorder, United States (US) hospitals face high health care costs when hospitalized patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) leave due to untreated opioid withdrawal. Recent studies have concluded that evidence-based interventions for OUD like buprenorphine are underutilized by hospital services.

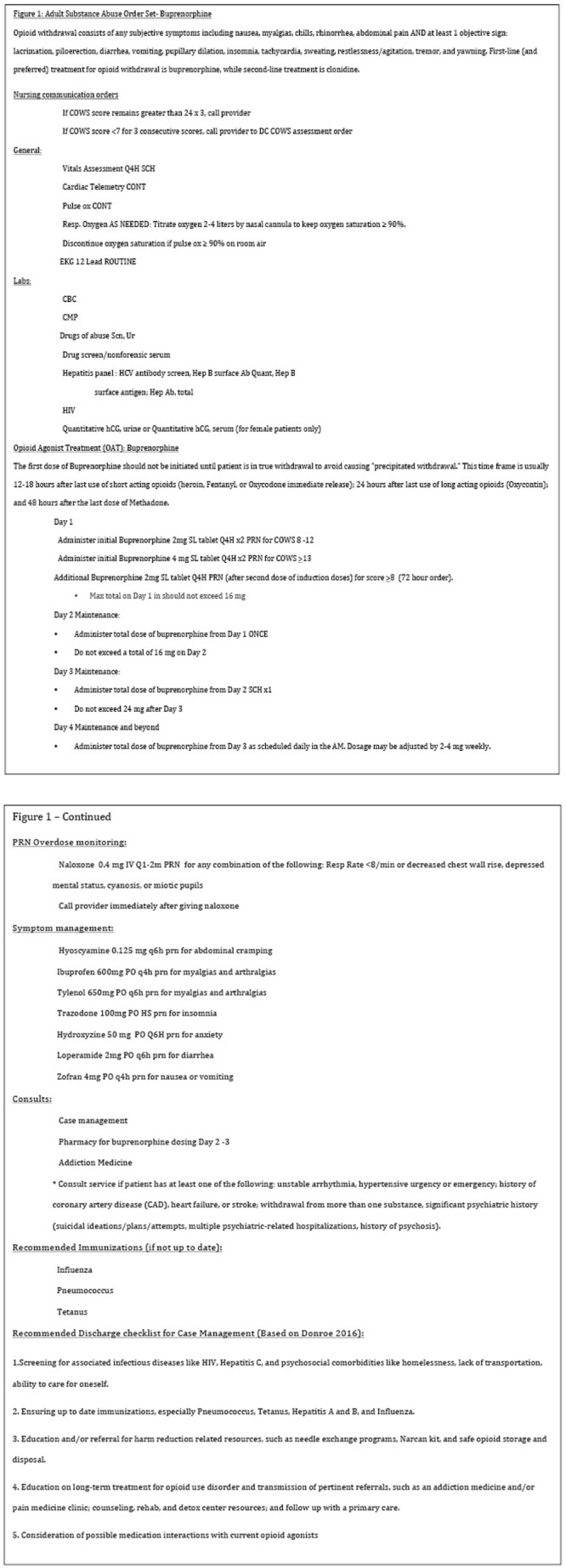

Objective: We developed a practical opioid withdrawal protocol utilizing buprenorphine and the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale to address opioid withdrawal during inpatient treatment of a primary medical condition. We are currently implementing this protocol at the UCLA hospital in Santa Monica.

Design: The protocol includes order sets with appropriate and modifiable orders that can be submitted in the electronic medical record in order to deliver seamless care for opioid withdrawal. After the physician assesses the patient and initiates the protocol, nursing provides an essential role in continuing to monitor the patient’s level of withdrawal and administering the appropriate medications in response. Inpatient pharmacy is instrumental in monitoring medication administration, as well as calculating and providing dosages for orders on Day 2 and 3 of the protocol. Collaboration with case managers is essential for providing appropriate resources and ensuring a safe discharge.

Conclusion: Current challenges to widespread implementation of a standardized withdrawal protocol are discrepancies in addiction education across medical disciplines and inadequate outpatient access to buprenorphine providers and pharmacies that carry buprenorphine supplies.

Keywords: inpatient, opioid, withdrawal, buprenorphine, addiction, overdoses

Introduction

Patients with substance use disorders are among the highest users of hospital services 1 . With continually rising total nominal healthcare spending, increased overdoses and death of the current opioid epidemic, and costs associated with the COVID-19 pandemic 2 , the very survival of hospitals may depend on developing cost-effective and evidence-based ways of providing care. Unfortunately, addiction-specific interventions for opioid use disorder during admission and at discharge are underused, and therefore a missed opportunity for saving costs and delivering quality care 3 . Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) with methadone or buprenorphine, when compared to brief intervention and referral, has been shown to result in 4 :

- fewer relapses

- decreased mortality rates

- decreased acquisition of HIV infection

- decreased criminal activity

- increased rate of retention in rehabilitation programs

However, the approach of medication-assisted treatment has yet to adapted at the level of hospital care 5 .

Patients seen with opioid withdrawal typically suffer from the commonly overlooked diagnosis of opioid use disorder (OUD), and as a result, are seen most often at the hospital with complications such abscesses, cellulitis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, bacteremia, or history poly-substance use 6 . Many prescribers struggle to diagnose and manage OUD in patients being treated with opioids for chronic pain. The treatment for both opioid withdrawal and OUD is buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist with long-acting properties that act to minimize the “high” at the opioid receptors caused by other short-acting opioids 7 .

Proposed protocol

Our purpose is to suggest a practical and evidence-based protocol for hospitalists and other hospital care providers who are treating patients vulnerable to opioid withdrawal. We are currently implementing this protocol at UCLA hospital in Santa Monica, USA. The proposal was inspired by the legal allowance provided by Title 21 in the Code of Federal Regulations 1306.07c 8 regarding buprenorphine in the inpatient setting:

“This section is not intended to impose any limitations on a physician or authorized hospital staff to administer or dispense narcotic drugs in a hospital to maintain or detoxify a person as an incidental adjunct to medical or surgical treatment of conditions other than addiction, or to administer or dispense narcotic drugs to persons with intractable pain in which no relief or cure is possible or none has been found after reasonable efforts.”

The protocol incorporates administration of buprenorphine guided by the use of a clinician tool called the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS 9 ), which can be seen as parallel to the Clinical Intoxication Withdrawal Assessment (CIWA-AR; 10 ) for alcohol use disorder. Recommended order sets for treatment with buprenorphine are included ( Figure 1). An important note is that these orders can be adjusted based on feasible workflows and nursing availability of the institution; for example, additional buprenorphine can be provided within 1-3 hours as needed after the initial dose of buprenorphine if the patient complains of persistent, severe withdrawal symptoms 11 .

Figure 1.

The daily average maintenance dose ranges between 6–16 mg per day; however the provider must be mindful of individualizing care for each patient, which can be achieved by correlating doses with COWS scoring. Scores can be computed manually or through a flowsheet in the electronic medical record, where they can be easily monitored. Just as pharmacies assist with the dosing of vancomycin and warfarin, we feel that the inpatient pharmacist can also provide assistance in ensuring correct baseline dosing on day 2 and day 3 of the protocol, based on the addition of the doses received the previous day and ensuring the patient receives that specific amount for treatment consistency.

The first dose of buprenorphine should be provided when the patient is in moderate withdrawal or at least 12 hours after a short-acting opioid 12 . The protocol is useful for providing these instructions to the healthcare provider. Patients should be very open about their use when offered buprenorphine as a relief, since the terrible symptoms of withdrawal are very uncomfortable and can be life threatening 13 . In the event that a patient undergoes precipitated withdrawal after receiving the first dose of buprenorphine, the provider may provide supportive treatment in addition to clonidine or repeat buprenorphine 2 mg every one hour for four doses followed by administration of 8 mg for two doses (maximum 24 mg), until relief is achieved.

Conclusion

Continuation of buprenorphine for long-term management in OUD is advised. This medication should be given in the form of buprenorphine/naloxone to discourage diversion. If the patient is unable to continue after discharge, the medication can be tapered, although this option is highly discouraged 14 .

No study has established the optimal duration of MOUD, but it should be noted that patients with OUD are vulnerable to interruptions in their buprenorphine treatment 15 and have a high risk of relapse after stopping their maintenance medication 16 . If the patient chooses not to continue buprenorphine, he/she must be educated on the risk of relapse and provided with referral for continued treatment. All patients with opioid use disorder should be discharged with naloxone and handouts on how to accept buprenorphine treatment 17 .

Case management can play a key role in coordinating resources with outpatient providers, treatment centers, and/or living facilities based on insurance and social situation 18 . Case managers should have an updated list of substance abuse treatment resources (including rehabilitation centers), and active buprenorphine providers to reference when coordinating a patient’s discharge.

Current challenges to widespread implementation are misconceptions surrounding addiction treatment, discrepancies in addiction education across medical disciplines, and inadequate outpatient access to buprenorphine providers and pharmacies that carry buprenorphine supplies 19 . However, these obstacles should not delay hospitals from establishing a standardized system for treating patients for opioid withdrawal, especially in the midst of the current opioid crisis. While education and expanding outpatient resources will remain an ongoing endeavor in the foreseeable future, opioid withdrawal must be treated with the same seriousness and standard of care as is generally done with any other medical problem for the duration of a patient’s inpatient stay.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was not sought/required as the protocol hasn’t been experimented yet, and no patient interaction or similar activity occurred.

Data availability

No data are associated with this article.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UCLA Hospital of Santa Monica and the Departments of Family Medicine , Addiction Medicine, and Quality Improvement. We thank Philip Levin, medical director, for his unwavering leadership and commitment to high quality of care. For their support and contribution, we extend appreciation to Roger Lee, head of Hospital Medicine,

Sherry Watson-Lawler and Elisa Lynn from Quality Improvement, Alise Hadley and Jason Madamba from Pharmacy leadership, Coleen Wilson and Mary Beth Chambers from Nursing leadership, and Mary Noli Pilkington from Care Coordination and Clinical Social work. Consent was obtained for the individuals listed above to be named in this article.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Peterson C, Li M, Xu L, et al. : Assessment of Annual Cost of Substance Use Disorder in US Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210242. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barocas JA, Savinkina A, Adams J, et al. : Clinical impact, costs, and cost-effectiveness of hospital-based strategies for addressing the US opioid epidemic: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(1):e56–e64. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00248-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Theisen-Toupal J, et al. : Suboptimal Addiction Interventions for Patients Hospitalized with Injection Drug Use-Associated Infective Endocarditis. Am J Med. 2016;129(5):481–5. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. : Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–44. 10.1001/jama.2015.3474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim B, Nolan S, Ti L: Addressing the prescription opioid crisis: Potential for hospital-based interventions? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017;36(2):149–152. 10.1111/dar.12541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eaton EF, Vettese T: Management of Opioid Use Disorder and Infectious Disease in the Inpatient Setting. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2020;34(3):511–524. 10.1016/j.idc.2020.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R: CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–1645. 10.1001/jama.2016.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration: 21 CFR 1306.07 - Administering or dispensing of narcotic drugs.1998; 21 CFR 1306.07. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wesson DR, Ling W: The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(2):253–259. 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. : Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353–7. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. California Society of Addiction Medicine: 2019 Guidelines for Physicians Working in California Opioid Treatment Programs.San Francisco, CA: California Department of Health Care Services;2019. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chou R, Korthuis PT, Weimer M, et al. : Medication-Assisted Treatment Models of Care for Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care Settings.2016. Reference Source [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Darke S, Larney S, Farrell M: Yes, people can die from opiate withdrawal. Addiction. 2017;112(2):199–200. 10.1111/add.13512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nielsen S, Hillhouse M, Thomas C, et al. : A comparison of buprenorphine taper outcomes between prescription opioid and heroin users. J Addict Med. 2013;7(1):33–8. 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318277e92e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morgan JR, Schackman BR, Leff JA, et al. : Injectable naltrexone, oral naltrexone, and buprenorphine utilization and discontinuation among individuals treated for opioid use disorder in a United States commercially insured population. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;85:90–96. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bentzley BS, Barth KS, Back SE, et al. : Discontinuation of buprenorphine maintenance therapy: perspectives and outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;52:48–57. 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zoorob R, Kowalchuk A, Mejia de Grubb M: Buprenorphine Therapy for Opioid Use Disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(5):313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abbott PJ: Case management: ongoing evaluation of patients' needs in an opioid treatment program. Prof Case Manag. 2010;15(3):145–52. 10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181c8c72c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hill LG, Loera LJ, Evoy KE, et al. : Availability of buprenorphine/naloxone films and naloxone nasal spray in community pharmacies in Texas, USA. Addiction. 2021;116(6):1505–1511. 10.1111/add.15314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]