Abstract

Background/purpose

With increasing accessibility to the Internet, patients frequently use the Internet for hearing healthcare information. No study has examined the information about hearing loss available in the Mandarin language on online video-sharing platforms. The study's primary purpose is to investigate the content, source, understandability, and actionability of hearing loss information in the Mandarin language's one hundred most popular online videos.

Method

In this project, publicly accessible online videos were analyzed. One hundred of the most popular Mandarin-language videos about hearing loss were identified (51 videos on YouTube and 49 on the Bilibili video-sharing platform). They were manually coded for different popularity metrics, sources, and content. Each video was also rated using the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Audiovisual Materials (PEMAT-AV) to measure the understandability and actionability scores.

Results

The video sources were classified as either media (n = 36), professional (n = 39), or consumer (n = 25). The videos covered various topics, including symptoms, consequences, and treatment of hearing loss. Overall, videos attained adequate understandability scores (mean = 73.6%) but low (mean = 43.4%) actionability scores.

Conclusions

While existing online content related to hearing loss is quite diverse and largely understandable, those videos provide limited actionable information. Hearing healthcare professionals, media, and content creators can help patients better understand their conditions and make educated hearing healthcare decisions by focusing on the actionability information in their online videos.

Keywords: Hearing loss, YouTube, BiliBili, Internet health information, Social media

1. Introduction

Hearing loss is linked to serious communication and psychosocial issues (Cunningham and Tucci, 2017). The effect of hearing loss varies among adults and is affected by co-existing health conditions, sociability level, and ability to adapt to challenging situations and experiences (Souza and Lemos, 2021). Impaired communication is a major side effect of hearing loss, and it can severely affect relationships with friends and family, as well as at the workplace. Interventions that reduce activity restrictions for people with hearing loss can be very beneficial. However, hearing healthcare has a vast health service gap (World Health Organization, 2021), and not all individuals know that effective interventions exist for hearing loss. Therefore, there is a need to present accurate information and advice regarding hearing evaluations and the availability of treatment options for individuals with hearing loss.

Since the Internet launch in 1989, Internet use has increased both substantially and rapidly. The percentage of individuals using the Internet worldwide grew over eight times within twenty years: 7% in 2000 to 60% in 2020. With the exponential growth of the Internet, online health information-seeking behavior has become a standard (Cline and Haynes, 2001), and patients are much more engaged in their healthcare (Forczek et al., 2015). Patients are more likely to use the Internet now than in previous decades to research health issues, select treatments, and manage their health (Amante et al., 2015; Laplante-Lévesque et al., 2012; Simpson et al., 2018). A plethora of healthcare knowledge is made easily accessible to people through text-based or video-based platforms. Because video-based formats are more engaging for the individual, patients and/or their family members are more likely to look to videos as sources of information rather than text-based web pages (Van den Eynde et al., 2019). The most widely used website for watching and sharing videos is YouTube. Along with providing entertainment, YouTube has developed into a popular forum for disseminating health-related information. Online video platforms also incorporate interactive features such as commenting, reacting, and messaging options to facilitate communication between the content creator and the viewers. YouTube is a commonly used platform for accessing various hearing healthcare information, even among older adults with hearing loss (Manchaiah et al., 2020a). Most participants in this study reported that it was challenging to locate reliable information on hearing health on YouTube. Overall, the growth of the Internet has allowed patients to take a much more active role in their search for and gathering hearing health information about assessments and treatments.

Despite these benefits, there is a need for improvement regarding acquiring accurate health-related information online. There is a lot of misinformation and unverified content on various platforms, and it can be challenging to determine the credibility of a particular source. Internet users need to exercise caution when seeking health information on video-sharing platforms. Multiple research studies have questioned the reliability of online content and have warned about the danger of misleading content (Amante et al., 2015; Cline and Haynes, 2001; J. Kim et al., 2021; R. Kim et al., 2017; Madathil et al., 2015; Manchaiah et al., 2020a). Additionally, according to these researchers, people rely more on the information they find on the Internet without questioning its veracity. As a result, people can be misled by information found online. Therefore, a thorough evaluation of the information presented online about hearing health is essential to public health and safety.

Madathil et al. (2015) conducted a systematic review of research related to healthcare YouTube videos. The study considered 18 articles for systematic review. The study's findings suggested the presence of misleading health information (anecdotal evidence), and the government and professional organizations uploaded high-content videos. The study recognizes that the layperson must assimilate the information presented and be vigilant and authoritative in healthcare decisions. The Internet and online videos may be used as a resource by individuals with hearing loss before seeking professional help. Hearing healthcare professionals must be aware of what online information is presented to the public and understand what predispositions the public is exposed to before seeking professional service. This information helps hearing healthcare professionals provide effective counseling and treatment strategies.

Many helpful video resources are available online for people with hearing loss and their communication partners. However, the videos vary widely in terms of quality, source, content, and actionable information. Typically, the major sources of the videos are Media, Professionals, and Consumers. Understandability and actionability were commonly used to evaluate medical audiovisual materials. Understandability is the ability of patient education materials to be understood by consumers from a wide range of backgrounds and health literacy levels. Actionability refers to a consumer's ability to determine what actions they can take in light of the information provided, regardless of their background or level of health literacy. The Patient Education Material Assessment Tool for Audiovisual Materials (PEMAT-A/V) is a tool to evaluate patient education materials' understandability and actionability scores (Shoemaker et al., 2014).

There have been a handful of research articles that are related to audiology and online video platforms. Basch et al. (2018) examined tinnitus information in one hundred most viewed YouTube videos. Out of the one hundred videos, only one-fourth of them are uploaded by professionals, while the remainder consists of videos that are anecdotal information provided by media and consumers, rendering the overall quality of the content questionable. Gunjawate et al. (2021) examined YouTube videos addressing infant hearing loss. The authors concluded that the videos have poor scores for both understandability and actionability, and there is a need for more credible content for infant hearing loss on YouTube and other online video platforms. Similar studies on the hearing loss (Manchaiah et al., 2020b) and hearing aids (Manchaiah et al., 2020c) showed acceptable understandability but poor actionability scores.

The video-sharing platforms contain videos in different languages, and patients generally access information in their native language or language with high proficiency. The available studies looking at the source, content, understandability, and actionability of online videos related to hearing health are all in English. No studies have examined other major languages, such as Mandarin and Spanish. Searching Mandarin with YouTube and hearing loss as keywords in databases such as PubMed and EBSCO yielded no relevant results. Thus, the project aims to analyze the source, popularity, content, understandability, and actionability of the most viewed one hundred online Mandarin videos. A QR code of video links with high content, understandability, and actionability scores is also provided.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

In this project, publicly accessible online videos were analyzed. The study's methodology is comparable to English-language studies on YouTube about hearing healthcare (Manchaiah et al., 2020b, 2020c). Since there were no human test subjects, the IRB did not need to approve this study.

2.2. Extraction of video data

2.2.1. Video search and video inclusion

The top 100 Mandarin language videos (from YouTube and Bilibili's online video platforms) that offered content that would be beneficial, instructive, and practical for those with hearing loss were considered for analysis. We opted to only include Bilibili and YouTube platforms in our study due to their accessibility for content creators to upload videos freely. Videos were included if they discussed signs, causes, consequences, treatments, acceptance, personal experiences, or coping information related to hearing loss. Due to the overall inclusion criteria, we utilized broad search terms that corresponded to the Mandarin translations of “hearing loss” and “hearing impairment”. The search terms considered were 聽障 (hearing impaired), 聽力障礙 (hearing difficulties), 耳聾 (deaf/hard of hearing), and 聽力下降 (hearing declined). This method made it possible to collect a wide range of frequently found videos about hearing loss. The inclusion criteria considered were: (1) the video contained information about causes, symptoms, treatments, experiences, and representations of hearing loss, (2) the video language was Mandarin Chinese, and (3) the video was freely accessible to public. Videos were disqualified if they were duplicates of previously released ones, presented in Chinese dialects other than Mandarin, primarily served as advertisements, or were too short (under 30 s). Since the popular video-sharing platform, YouTube was inaccessible in Mainland China, videos were also identified from Bilibili (nicknamed B site) video-sharing platform. In total, 51 videos were selected from YouTube and 49 from the Bilibili video-sharing platform.

Since YouTube and Bilibili online video platforms present search results based on the type of Internet browser used, the user's geographic location, the time of the search, and the user preference, the researcher performed the search on Google Chrome with an incognito window. Before the search, the researcher deleted browser history and cleared cookies to reduce bias during searching. The search process resulted in the exclusion of 62 videos in total. Ten of these videos were not in Mandarin. Fifty-two videos were also disqualified for the following reasons: main focus on Deaf culture, manual form of communication or sign language (n = 7); removal of earwax and foreign objects (n = 12), tinnitus is the main focus or sharing personal experience of tinnitus (n = 7), advertisements or entertainment videos (n = 7), too short (>30 s) (n = 12), and duplication of videos (n = 7). The videos were enrolled for the study between April to May 2021.

2.2.2. Extracting video popularity measures

After selecting the sample of 100 videos (51 from YouTube and 49 from Bilibili), the main descriptive popularity-based metadata (number of views, thumbs-up, thumbs-down) was extracted. The analysis only considered the thumbs-down data from YouTube videos since the Bilibili video-sharing platform did not allow viewers to thumbs-down a video.

2.2.3. Video source and video content coding

Source coding: The three categories listed below were created for categorizing the sources of uploads: Consumer (i.e., a member of the general public); Professional (i.e., a person with the necessary credentials and affiliations to speak on the subject); or Media (i.e., any clip that was derived from a television-based clip or an Internet channel or website).

Content coding: The valuable, informative, and helpful content for a person with hearing loss was considered for analysis. The English-language study that was conducted previously served as the reference for the content categories (Manchaiah et al., 2020b). The hearing mechanism, symptoms, types, and degrees of hearing loss, medical or genetic aspects related to hearing impairment, hearing loss causes, effects of hearing loss on a person's life and employment, effects of hearing loss on interaction with partners, confirmation or diagnosis of hearing loss, treatment or management of hearing loss, acceptance and coping, hearing loss prevention, and featuring a celebrity are among the content codes of this study. Each content code has been described along with its Mandarin translation in Appendix A. Additionally, the videos' overall goal is graded across three categories: 1. General information about hearing and/or hearing loss, 2. Personal experience with hearing loss, 3. Management or prevention of hearing loss. The content code and purpose of the video were manually scored and converted to a binary scale. For instance, if the video did not contain content described by the item, the item received 0 points. If the video contains content the item represents, the item receives 1 point. The researcher performed content coding pausing the video after 30 s to avoid the memory effect.

2.2.4. Assessment of understandability and actionability

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality developed the Patient Education Material Assessment Tool (PEMAT), a free, publicly accessible tool, to evaluate the understandability and actionability of patient education materials (Shoemaker et al., 2014). The information intended for a patient audience has been evaluated using PEMAT (Balakrishnan et al., 2016; Lambert et al., 2017). The PEMAT-Audiovisual (PEMAT-AV) comprises 17 items intended for the evaluation of audiovisual resources, particularly videos found on online platforms. Thirteen of these items pertain to the assessment of understandability, while the remaining four focus on actionability. Each statement was given a score of (1) agree, (0) disagree, or N/A (not applicable). The percentage understandability and actionability subscale scores were determined by dividing the number of items that received a score of 1 (i.e., agree) by the total number of items. The calculation excluded items that were marked as not applicable. Higher percentages denote more understandable and actionable information in audiovisual material. Scores below 70% indicate poor actionability or understandability scores (Shoemaker et al., 2014).

The quality assessment process was run by two audiology doctoral students. After following the steps, as outlined in the PEMAT-AV manual, which included reading through the manual and User's Guide, watching videos, evaluating each item in the PEMAT-AV individually, and scoring the videos based on each item, they calculated each video's respective scores for actionability and understandability, and content coding. To ensure accuracy and consistency, the raters initially assessed twenty videos in the English language related to hearing loss. This step served as a calibration process for their responses using the PEMAT-AV and content coding. Once a good level of inter-rater reliability was established (indicated by an interclass correlation coefficient of >0.8), a native Mandarin speaker, who was also a doctoral student researcher, reviewed each of the 100 Mandarin videos.

2.3. Data analysis

The R statistical package (V 4.1.2) was used for the statistical analysis. The descriptive statistics were calculated for the video metadata. The PEMAT-A/V scores (i.e., the understandability and actionability subscale scores) and the video metadata were subjected to normality tests. According to the Shapiro-Wilk test and visual inspection of normality plots, these variables appeared to deviate from the normality assumption. Nonparametric tests were therefore employed for additional analysis. A chi-square analysis was conducted to determine whether video content differed across various video sources. The Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to determine whether the PEMAT-A/V scores and metadata varied depending on the type of video source (consumer, professional, or media-based) and between video sharing platforms (YouTube and Bilibili). The significant variables in the Kruskal-Wallis H test were subjected to a pairwise analysis using the Bonferroni post hoc test. Spearman correlation was used to investigate the relationship between the metadata of videos. The correlation coefficient was used to analyze the interrater reliability for PEMAT-A/V subscale ratings. Results were interpreted at a significance level of 0.05, and Bonferroni's corrections were applied for multiple comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Video popularity and video sources

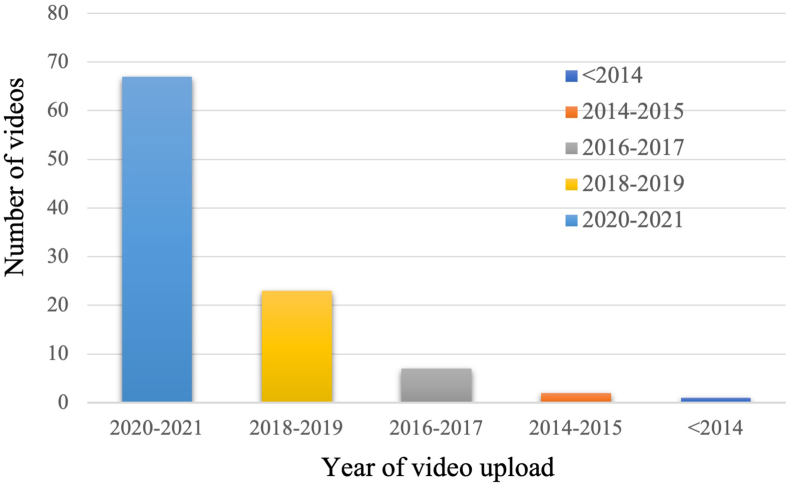

Among the 100 most popular hearing loss-related videos in the Mandarin language, the sources of the videos were categorized into three groups: media (n = 36), professional (n = 39), and consumer (n = 25). Fig. 1 displays the histogram representing the years when the videos were uploaded. It is clear from Fig. 1 that a majority of the videos were recently uploaded, specifically between 2020 and 2021, indicating an upward trend in the posting of YouTube videos in Mandarin language concerning hearing health.

Fig. 1.

Histogram of the year of video upload versus the number of videos.

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics about the popularity-based metadata. The videos received an average of 42,890 views (21–947,953). There were over 4.29 million views in total. The video's duration ranged from 1:00 to 39:17 min, with a mean of 6:34 min. The total time of all the videos combined is 655 min or 10.55 h. Thumbs-up and thumbs-down totaled 169,930 and 325, respectively, for these videos. The Bilibili video-sharing platform no longer displays the total number of thumbs-downs, contributing partly to the overall thumbs-down being lower. The Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to determine whether the metadata varied between different video sources. There were significant differences in the number of views between video sources (χ2 = 22.145, p = <0.001), thumbs-up (χ2 = 29.6, p = <0.001), thumbs-down (χ2 = 12.8, p = <0.01), but not for video length (χ2 = 2.7, p = 0.259). For the number of views, the pairwise comparisons with the Dunn test adjusting for multiple comparisons showed that Consumer videos have higher thumbs-ups than Media and Professional videos, and media videos have higher thumbs-ups than professional videos (p < 0.05). The consumer videos had a higher thumbs-up and thumbs-down than media and professional videos, whereas media and professional videos were not different. The Spearman rho correlation test was used to investigate the relationships between metadata. Thumbs-up and thumbs-down responses had a strong positive correlation with the total number of views (p < 0.001). Thumbs-up and thumbs-down responses showed a strong positive correlation (p < 0.01). The most popular videos are more likely to receive thumbs-ups and thumbs-downs, so these results are to be expected. The duration of the video had no discernible relationship to the other metadata.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, including views, video length, thumbs-up/down, categorized by source, for the 100 most popular hearing loss videos in Mandarin.

| Mean | Median | Min-Max | SD | SE | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of views | ||||||

| Consumer | 68,699 | 4406 | 140, 420,931 | 122,243 | 24,449 | 1,717,480 |

| Professional | 54,068 | 345 | 21, 947,953 | 211,619 | 33,886 | 2,108,637 |

| Media | 12,858 | 2287 | 80, 160,563 | 36,881 | 6147 | 462,891 |

| All | 42,890 | 1837 | 21, 947,953 | 147,778 | 14,778 | 4,289,008 |

| Video length (mm:ss) | ||||||

| Consumer | 6:49 | 6:17 | 1:32, 20:36 | 4:28 | 0:54 | 170:37 |

| Professional | 5:47 | 4:15 | 1:00, 18:46 | 4:58 | 0:48 | 225:31 |

| Media | 7:33 | 4:27 | 1:02, 39:17 | 8:22 | 1:24 | 271:48 |

| All | 6:34 | 4:27 | 1:00, 39:17 | 6:16 | 0:38 | 655:56 |

| Number of thumbs-ups | ||||||

| Consumer | 2560 | 163 | 0-12,654 | 4099 | 820 | 64,006 |

| Professional | 130 | 20 | 0-1818 | 416 | 069 | 4674 |

| Media | 2596 | 04 | 0-47,059 | 10,516 | 1684 | 101,250 |

| All | 1699 | 23 | 0-47,509 | 6927 | 693 | 169,930 |

| Number of thumbs-downs | ||||||

| Consumer | 16.5 | 03 | 0–88 | 28.32 | 07.57 | 231 |

| Professional | 02.0 | 01 | 0–23 | 04.41 | 0.85 | 56 |

| Media | 03.8 | 00 | 0–35 | 10.97 | 03.49 | 38 |

| All | 06.4 | 01 | 0–88 | 16.74 | 02.36 | 325 |

3.2. Video content categories

Table 2 lists the percentage of the 100 most popular hearing loss videos that address the specific content theme and the overall objective. Online Mandarin videos provide a diverse range of content themes, with the majority catering to consumers' preferences. These include videos featuring individuals with hearing loss, the treatment and management of hearing loss, the impact of hearing loss on one's personal and professional life, as well as the symptoms associated with hearing loss. Videos uploaded by professionals frequently included information on the causes, types, and severity of hearing loss and its management and treatment. On the other hand, in media videos, persons with hearing loss, the symptoms of hearing loss, and the management of hearing loss were featured. The three video sources all serve the general purpose of disseminating information about hearing, hearing loss, and the treatment or prevention of hearing loss. Unlike media and professional videos, consumer-uploaded videos include personal hearing loss experiences. For four video content codes (types and degrees of hearing loss, effects of hearing loss on development, treatment or management of hearing loss, and hearing loss prevention), the chi-square analysis revealed no correlation between the video sources. The remaining content found a significant association with the video upload source. The Chi-square results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Percentage of the 100 most popular hearing loss videos that present a specific content theme and their overall purpose.

| Content | Source category of video in % |

Association with source |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Consumer | Professionals | Media | χ2 | p-value | |

| Hearing mechanism | 16 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 14.176 | 0.001 |

| Types and degree of hearing loss | 49 | 36 | 62 | 44 | 4.3987 | 0.1109 |

| Hearing loss signs and symptoms | 60 | 80 | 31 | 78 | 22.564 | <0.001 |

| Medical or genetic aspects related to hearing impairment | 39 | 12 | 54 | 42 | 11.268 | 0.004 |

| Hearing loss causes | 51 | 20 | 62 | 58 | 11.956 | 0.003 |

| Aspects of hearing loss that relate to development | 10 | 12 | 3 | 17 | 4.2421 | 0.1199 |

| Effects of hearing loss on a person's life and employment | 58 | 84 | 28 | 67 | 21.626 | <0.001 |

| Hearing loss effects on communication partners: | 37 | 48 | 21 | 44 | 6.6693 | 0.04 |

| Confirmation or diagnosis of hearing loss | 48 | 16 | 59 | 58 | 13.542 | 0.001 |

| Hearing loss management or treatment | 75 | 84 | 62 | 83 | 6.1207 | 0.06 |

| Acceptance and coping | 28 | 60 | 3 | 33 | 25.465 | <0.001 |

| Prevention of hearing loss | 16 | 4 | 21 | 19 | 3.5515 | 0.1694 |

| Featuring an individual with hearing loss | 54 | 96 | 5 | 78 | 62.813 | <0.001 |

| Purpose | ||||||

|

97 | 92 | 100 | 97 | 2 | 0.3679 |

|

54 | 100 | 8 | 72 | 61.2 | <0.001 |

|

81 | 80 | 72 | 92 | 3.3 | 0.24 |

Note: Bolded items are those with significant differences according to Bonferroni-corrected significance levels.

3.3. Understandability and actionability

The PEMAT-A/V assessed the YouTube video content's understandability and actionability scores. The understandability and actionability had an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.84 and 0.87, respectively, indicating good inter-rater reliability. The descriptive statistics for the PEMAT-A/V ratings are shown in Table 3. Regarding understandability, over 80% of the videos made their purpose evident, used everyday usage language, used active voice, presented in a logical sequence, and materials were explained clearly. An adequate rating (i.e., over 70%) was also attained for familiarizing the audience with medical terms. On the other hand, many videos should have broken information into short sections, include informative headers, provide a summary, and use illustrations and photographs. In the actionability subscale, none of the topics reached an adequate rating of over 70%. The descriptive statistics of the understandability and actionability scores broken down into the three types of video sources—consumer, professional, and media—are presented in Table 4. The mean understandability score of 73.6% is deemed adequate, but the actionability score of 43% falls below the acceptable criterion of 70%, indicating inadequacy. The Kruskal-Wallis H test revealed a significant difference in the understandability scores across video sources (χ2 = 11.237, p = 0.003). The pairwise comparisons of understandability scores revealed that consumer videos had significantly lower understandability scores when compared to media and professional videos (p < 0.05). These findings imply that videos created by media and professionals were more straightforward for viewers to understand. But no significant difference between media and professional videos was found. The actionability scores from the three video sources did not differ according to the Kruskal-Wallis H test (χ2 = 0.238, p = 0.88). To understand the influence of video-sharing platforms (Bilibili and YouTube) on understandability and actionability scores, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was administered. The results indicated that YouTube videos had significantly better understandability (χ2 = 7.622, p = 0.007) and actionability (χ2 = 12.299, p = 0.0001) scores than Bilibili videos.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the PEMAT-A/V topics.

| PEMAT-A/V factors and items | Frequency (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disagree | Agree | Not applicable | |

| UNDERSTANDABILITY | |||

| TOPIC: CONTENT | |||

|

05 | 95 | 0 |

| TOPIC: WORD CHOICE & STYLE | |||

|

06 | 94 | 0 |

|

27 | 73 | 0 |

|

04 | 96 | 0 |

| TOPIC: ORGANIZATION | |||

|

67 | 33 | 0 |

|

68 | 32 | 0 |

|

07 | 93 | 0 |

|

92 | 08 | 0 |

| TOPIC: LAYOUT & DESIGN | |||

|

05 | 93 | 2 |

|

04 | 94 | 2 |

| TOPIC: USE OF VISUAL AIDS | |||

|

03 | 23 | 74 |

| ACTIONABILITY | |||

|

39 | 61 | 0 |

|

70 | 30 | 0 |

|

64 | 36 | 0 |

|

0 | 02 | 98 |

Table 4.

Percentage PEMAT A/V Understandability and Actionability Scores across video Sources.

| Source | Mean | Median | Min-Max | SD | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understandability | |||||

| Consumer | 65.5 | 70 | 12.5–90 | 17.9 | 14 |

| Professional | 74.5 | 72.72 | 50–100 | 9.67 | 1.54 |

| Media | 79 | 80 | 44.4–100 | 12.95 | 2.16 |

| All | 73.6 | 72.7 | 12.5–100 | 14.16 | 1.41 |

| Actionability | |||||

| Consumer | 40 | 33 | 0–100 | 39.7 | 13.3 |

| Professional | 44.7 | 33.33 | 0–100 | 44.9 | 7.19 |

| Media | 44.7 | 33.3 | 0–100 | 37 | 6.16 |

| All | 43.4 | 33.33 | 0–100 | 40.4 | 4.04 |

4. Discussions

Online health information-seeking behavior has become a standard, and patients increasingly depend on the Internet for healthcare information. This study aimed to analyze the source, popularity, content, understandability, and actionability of the top 100 online Mandarin videos (51 videos from YouTube and 49 from the Bilibili platform). The findings revealed that the videos came from a variety of sources, including media (n = 36), professional (n = 39), and consumer (n = 25) sources. Videos also had a wide range of content and received adequate understandability scores (73.6%) but very low actionability scores (43.4%).

When the year of video upload was compared, the majority of videos were uploaded recently between the year 2020–2021, suggesting increasing trends in uploading YouTube videos related to hearing health in the Mandarin language. These trends may follow for 2021–23 as there is greater awareness, need, and openness to use the Internet across ages. The increase in content creators and viewership during the COVID-19 pandemic would also influence the number of video uploads and views. The mean number of views and the mean length of the videos are surprisingly similar to videos on the same topic in English (Manchaiah et al., 2020b). Among all three sources, Consumer-uploaded videos have more views, thumbs-ups, and thumbs-downs than professional and media-uploaded videos. These results contrast with a similar English language study by Manchaiah et al. (2020b), where all three sources had similar views, thumbs-ups, and thumbs-downs. But, Basch et al. (2018) reported that consumer-uploaded videos were the most popular related to tinnitus.

4.1. Content of the online Mandarin videos

The information in the online Mandarin videos about hearing loss covers various topics, such as its causes, symptoms, management, and treatments. Most of the videos uploaded by consumers dealt with the effects of hearing loss on a person's life and career, as well as its treatment and management, offering insights from a personal perspective. Videos uploaded by professionals focused more on the causes, types, and degrees of hearing loss and their management and treatment. Videos uploaded by the media mainly featured people with hearing loss and its symptoms. These findings are grossly similar to a study on English videos by Manchaiah et al. (2020a, 2020b, 2020c), where consumers who uploaded videos had a mutual focus on personal experience of hearing loss as well as acceptance and coping. These findings suggest that consumers are interested in providing insights on living and coping with hearing loss regardless of language and culture. Similarly, media-uploaded videos in English and Mandarin feature individuals with hearing loss. However, there is a distinction in the content focus between the two languages. English media-uploaded videos tended to emphasize the causes of hearing loss, including pathologies of the outer, middle, and inner ear, that contribute to hearing impairment. On the other hand, Mandarin media-uploaded videos primarily discuss the symptoms associated with hearing loss, featuring individuals who experience hearing loss. This difference in content could be attributed to the fact that English-language media-uploaded videos often delve into individual cases and treatment options related to hearing loss, providing a comprehensive understanding of the condition. In contrast, Mandarin media-uploaded videos primarily focused on raising awareness about the symptoms of hearing loss and showcasing personal experiences. The content differences between English and Mandarin media-uploaded videos offer a clearer picture to researchers about the information available to individuals in each respective language. Overall, these findings suggest that the media is an essential source for the general public to obtain basic information related to hearing loss. In both English and Mandarin languages, the professionals who uploaded videos primarily focus on key aspects related to hearing loss, including its types, degrees, and treatment or management options. In English professional-uploaded videos, there is also a consideration of symptoms associated with hearing loss, whereas Mandarin professional-uploaded videos delve into the causes of hearing loss.

Generally, professional uploaded videos aim to provide comprehensive knowledge about hearing loss, covering medical and audiological aspects. However, they may offer less information regarding coping strategies and personal experiences of individuals with hearing loss. This observation aligns with a study by Basch et al. (2018), which found that consumers tend to share more personal information about tinnitus than other sources. These findings highlight the importance of different types of content while recognizing that information provided by various sources may vary. It is worth noting that the Mandarin language videos about hearing loss cover a wide range of topics, providing a diverse and comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

4.2. Understandability and actionability

In the Mandarin language, hearing loss-related videos achieved an average understandability score of 73.6% across different sources, with Consumer uploaded videos scoring the lowest at 66% and Media uploaded videos scoring the highest at 76%. On the other hand, English language videos regarding hearing loss obtained an average understandability score of 77% across all three sources, with Media uploaded videos scoring the lowest at 71% and Professional uploaded videos scoring the highest at 76% (Manchaiah et al., 2020b).

Overall, both the present study and a similar study in English indicate that videos from all three sources demonstrate good understandability, suggesting that individuals unfamiliar with hearing health can easily comprehend the content. However, when it comes to the actionability aspect, there is a notable difference. Mandarin language videos related to hearing loss have an average actionability score of 43%, indicating that they may have a limited impact on guiding viewers toward finding solutions for their hearing condition. Similarly, English language videos for hearing loss score an average actionability score of 31%, indicating a lack of clear guidance for the general public regarding actionable steps for addressing their hearing conditions (Manchaiah et al., 2020b).

Similar poor actionability scores have been reported across various topics (hearing aids (Manchaiah et al., 2020c), infant hearing loss (Gunjawate et al., 2021), and Autism (Bellon-Harn et al., 2020). Hearing healthcare professionals, media, and the general public should upload more videos with quality content and high understandability and actionability scores since it can help patients better understand their conditions and make educated hearing healthcare decisions. In addition, the high visibility of these videos may help reduce social stigmas associated with hearing loss treatment, such as the use of hearing aids. Overall, the actionability of the videos uploaded from all three sources remains low, implying that after the general public search for hearing loss-related information online, they are less likely to act regarding their hearing health condition. Therefore, it is recommended that content creators should include resources for referral, aural rehabilitation, and education to increase patients' awareness to act on their hearing conditions. This actionability information would raise awareness about hearing loss treatment and may also increase the likelihood of patients seeking professional evaluations and treatment.

Comparing the understandability and actionability scores between video-sharing platforms (Bilibili and YouTube), we found that YouTube videos exhibited significantly higher scores in both understandability and actionability compared to Bilibili videos. These disparities in scores could be attributed to the demographic composition of Bilibili's audience, which predominantly consists of younger individuals born between 1990 and 2009. This demographic characteristic may influence the content, style, and presentation of videos on the platform, potentially impacting user preferences and the effectiveness of health-related information delivery.

4.3. QR code of the videos of recommendation based on the content, understandability, and actionability scores

Five of the top 100 most watched videos on hearing loss were chosen as recommendations for Mandarin-speaking viewers interested in learning more about hearing loss symptoms, hearing conservation, and management for those with hearing loss. These videos received high ratings for their content, understandability, and actionability scores. Hearing healthcare professionals can also use these videos to increase patient awareness of their condition and effective management options. Fig. 2 is the QR code of these five recommended videos.

Fig. 2.

QR code of the five recommended videos based on the rating of content, Understandability, and Actionability scores.

5. Limitations and future research

A few limitations apply to this study. First, the study evaluated the source, purpose, understandability, and actionability; however, each video's content credibility was not assessed. Future studies need to explore the misinformation or the credibility of presented information. Second, there may be search bias from the person who collects the data and from the YouTube/Bilibili platforms that are country specific. Third, the PEMAT was a rating tool designed for the general public with no or limited knowledge of the researched topic. The rating individuals of this study were audiology doctoral students that are educated on hearing health-related topics and may have rated the videos with hearing health-related knowledge. Future research directions should consider working on rating videos in languages other than English and Mandarin and comparing the results based on language and cultural differences. In addition, the raters of the videos should include both individuals without audiology backgrounds and with audiology backgrounds and compare results from different raters.

6. Conclusion

Overall, online Mandarin videos provide content across a wide range of topics with adequate understandability scores related to hearing loss. However, the actionability scores are low, meaning that these videos may not provide enough information on what actionability to take when diagnosed with hearing loss. Hearing healthcare professionals, media, and the general public should upload more videos with quality content and high understandability and actionability scores since it can help the public better understand their conditions and make educated hearing healthcare decisions. Additionally, the increased visibility of these videos may assist in lessening the social stigma connected to hearing loss treatment, including the use of hearing aids.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dr. Vinaya Manchaiah for helping with the development of this project. The authors would also like to thank Ms. Allyson Goff and the California State University- Los Angeles writing center for professional editing and other expert assistance in improving the quality of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of PLA General Hospital Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery.

Appendix A.

Content Code (English/Mandarin)

-

1.

Hearing mechanism: the anatomy and physiology of the auditory system in people with or without hearing impairment; how sound is transmitted into the auditory system

聽覺機制:普通或受損聽覺系統的生理機能和構造;聲音在聽覺系統中的傳播

-

2.

Types and degree of hearing loss: Hearing loss types include sensorineural, conductive, mixed, congenital, and noise-induced; the degree of hearing loss is normal, mild, moderate, severe, and profound.

聽障的類型與程度:聽障的類型(例:感音神經性聽覺損傷、傳導性聽覺損傷、混合性聽覺損傷)和程度(例:輕度,中度,重度)

-

3.

Hearing loss signs and symptoms: symptoms of hearing loss, such as vertigo, aural fullness, ringing in the ears, and tinnitus; communication problems caused by hearing loss

聽障的症狀:與聽障相關的症狀如頭暈,耳朵腫脹感、暈眩、耳鳴; 與聽障相關的溝通障礙

-

4.

Medical or genetic aspects related to hearing impairment: inherited or incidental conditions that are related to hearing loss; genetic counseling and testing

醫學或遺傳原因導致的聽覺損傷:遺傳或意外導致的聽覺損傷;基因測試與基因諮詢

-

5.

Hearing loss causes: the pathologies of the outer/middle/inner ear that is associated with hearing loss; noise, traumatic brain injury, imbalance in pressure and other factors that contribute to hearing impairment

聽覺損傷的原因:外耳/中耳/內耳病變與聽障的關係;噪音、創傷性腦損傷、中內耳壓力不平衡及其他聽障相關因素

-

6.

Aspects of hearing loss that relate to development: the impact of hearing loss on speech, language, learning, and cognitive development

聽力問題對發育的影響:聽力問題對語言、學習、感知發展的影響

-

7.

Effects of hearing loss on a person's life and employment

聽力問題對自身的影響:聽力問題對聽障者自身的影響

-

8.

Impact of Hearing loss on communication partners: the impact of hearing loss on the caregiver, family member, and acquaintance of the individual with hearing loss

聽力問題對溝通對象的影響:聽力問題對照顧者、家庭成員、旁人的影響

-

9.

Confirmation or diagnosis of hearing loss: medical evaluation that confirms hearing loss

聽力損傷的診斷:聽障的醫學診斷或自我判斷

-

10.

Hearing loss management or treatment: hearing loss treatment such as hearing aids, assistive devices, implantable devices, and options for the management of hearing loss such as aural rehabilitation classes and communication strategies; research that is related to hearing loss treatment

聽障治療手段:醫療器械如助聽器、輔具、電子耳等,或是聽力復健課程,溝通技巧等手段,以及治療聽障相關的研究

-

11.

Acceptance and coping: understanding and accepting the potential obstacles of hearing impairment; coping with the consequences of hearing loss on self and others

接受和應對:理解和接受聽障帶來的潛在障礙; 聽障對自身與他人帶來影響的應對方式

-

12.

Prevention of hearing loss: principles, recommendations, and tools for protecting hearing; noise and hearing loss

聽覺損傷的預防:聽力保護相關的準則、條例、器具;噪音與聽障

-

13.

Featuring an individual with hearing loss: sharing a personal experience or discussing hearing loss-related issues to raise public awareness of hearing loss

聽障者的經驗分享:個人經驗分享或討論聽障相關話題,幫助大眾了解聽障

References

- Amante D.J., Hogan T.P., Pagoto S.L., English T.M., Lapane K.L. Access to care and use of the Internet to search for health information: results from the US national health interview survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015;17(4):e106. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan V., Chandy Z., Hseih A., Bui T.-L., Verma S.P. Readability and understandability of online vocal cord paralysis materials. Otolaryngology-Head Neck Surg. (Tokyo) 2016;154(3):460–464. doi: 10.1177/0194599815626146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch C.H., Yin J., Kollia B., Adedokun A., Trusty S., Yeboah F., Fung I.C.-H. Public online information about tinnitus: a cross-sectional study of YouTube videos. Noise Health. 2018;20(92):1–8. doi: 10.4103/nah.NAH_32_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellon-Harn M.L., Manchaiah V., Morris L.R. A cross-sectional descriptive analysis of portrayal of autism spectrum disorders in YouTube videos: a short report. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice. 2020;24(1):263–268. doi: 10.1177/1362361319864222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline R.J., Haynes K.M. Consumer health information seeking on the Internet: the state of the art. Health Educ. Res. 2001;16(6):671–692. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham L.L., Tucci D.L. Hearing loss in adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377(25):2465–2473. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1616601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forczek E., Makra P., Lanyi C.S., Bari F. The Internet as a new tool in the rehabilitation process of patients—education in focus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2015;12(3):2373–2391. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120302373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunjawate D.R., Ravi R., Bellon-Harn M.L., Manchaiah V. Content analysis of YouTube videos addressing infant hearing loss: a cross-sectional study. J. Consum. Health Internet. 2021;25(1):20–34. doi: 10.1080/15398285.2020.1852387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim R., Jun J.-S., Ahn S.-H., Jung S., Minn Y.-K., Hwang S.H. Content analysis of Korean videos regarding restless legs syndrome on YouTube. Journal of Movement Disorders. 2021;14(2):144–147. doi: 10.14802/jmd.20137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R., Park H.-Y., Kim H.-J., Kim A., Jang M.-H., Jeon B. Dry facts are not always inviting: a content analysis of Korean videos regarding Parkinson's disease on YouTube. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017;46:167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert K., Mullan J., Mansfield K., Koukomous A., Mesiti L. Evaluation of the quality and health literacy demand of online renal diet information. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017;30(5):634–645. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante-Lévesque A., Knudsen L.V., Preminger J.E., Jones L., Nielsen C., Öberg M., Lunner T., Hickson L., Naylor G., Kramer S.E. Hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation: perspectives of adults with hearing impairment. Int. J. Audiol. 2012;51(2):93–102. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2011.606284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madathil K.C., Rivera-Rodriguez A.J., Greenstein J.S., Gramopadhye A.K. Healthcare information on YouTube: a systematic review. Health Inf. J. 2015;21(3):173–194. doi: 10.1177/1460458213512220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchaiah V., Bellon, -Harn Monica L., Kelly, -Campbell Rebecca J., Beukes E.W., Bailey A., Pyykk ő I. Media use by older adults with hearing loss: an exploratory survey. Am. J. Audiol. 2020;29(2):218–225. doi: 10.1044/2020_AJA-19-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchaiah V., Bellon-Harn M.L., Godina I.M., Beukes E.W., Vinay Portrayal of hearing loss in YouTube videos: an exploratory cross-sectional analysis. Am. J. Audiol. 2020;29(3):450–459. doi: 10.1044/2020_AJA-19-00121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchaiah V., Bellon-Harn M.L., Michaels M., Swarnalatha Nagaraj V., Beukes E.W. A content analysis of YouTube videos related to hearing aids. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2020;31(9):636–645. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1717123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker S.J., Wolf M.S., Brach C. Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ. Counsel. 2014;96(3):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A., Clarke S., Šarkić B., Smullen J.B., Pereira C.J. Internet usage and loneliness in older hearing aid wearers. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology. 2018;42:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Souza V.C., Lemos S.M.A. Restrição à participação de adultos e idosos: associação com fatores auditivos e socioambientais. CoDAS. 2021;33(6) doi: 10.1590/2317-1782/20202020212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eynde J., Crauwels A., Demaerel P.G., Van Eycken L., Bullens D., Schrijvers R., Toelen J. YouTube videos as a source of information about immunology for medical students: cross-sectional study. JMIR Medical Education. 2019;5(1) doi: 10.2196/12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2021. World report on hearing—executive summary.https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240021570 from. [Google Scholar]