Highlights

-

•

The expression levels of IFN-α, IFN-β and TLR3 significantly downregulated in cervico-vaginal samples of the HPV+ persistence group compared with the HPV+ clearance group.

-

•

L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 isolated from cervicovaginal samples of HPV clearance in women altered the host's epithelial immune response, particularly L. gasseri LGV03.

-

•

L. gasseri LGV03 enhanced the poly (I:C)-induced production of IFN by modulating the IRF3 pathway and attenuating poly (I:C)-induced production of proinflammatory mediators by regulating the NF-κB pathway in Ect1/E6E7 cells, indicating that L. gasseri LGV03 keeps the innate system alert to potential pathogens and reduces the inflammatory effects during persistent pathogen infection.

-

•

L. gasseri LGV03 also markedly inhibited the proliferation of Ect1/E6E7 cells in a zebrafish xenograft model, which may be attributed to an increased immune response mediated by L. gasseri LGV03.

Keywords: HPV clearance, Lactobacillus gasseri LGV03, Antiviral immune response, IRF3 and NF-κB signaling, Common cervicovaginal microbiota

Abstract

Persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infections is necessary for the development of cervical cancers. An increasing number of retrospective studies have found the depletion of Lactobacillus microbiota in the cervico-vagina facilitate HPV infection and might be involved in viral persistence and cancer development. However, there have been no reports confirming the immunomodulatory effects of Lactobacillus microbiota isolated from cervico-vaginal samples of HPV clearance in women. Using cervico-vaginal samples from HPV persistent infection and clearance in women, this study investigated the local immune properties in cervical mucosa. As expected, type I interferons, such as IFN-α and IFN-β, and TLR3 globally downregulated in HPV+ persistence group. Luminex cytokine/chemokine panel analysis revealed that L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 isolated from cervicovaginal samples of HPV clearance in women altered the host's epithelial immune response, particularly L. gasseri LGV03. Furthermore, L. gasseri LGV03 enhanced the poly (I:C)-induced production of IFN by modulating the IRF3 pathway and attenuating poly (I:C)-induced production of proinflammatory mediators by regulating the NF-κB pathway in Ect1/E6E7 cells, indicating that L. gasseri LGV03 keeps the innate system alert to potential pathogens and reduces the inflammatory effects during persistent pathogen infection. L. gasseri LGV03 also markedly inhibited the proliferation of Ect1/E6E7 cells in a zebrafish xenograft model, which may be attributed to an increased immune response mediated by L. gasseri LGV03.

Graphical abstract

In this study, a Luminex cytokine/chemokine panel revealed that L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 isolated from cervico-vaginal samples of HPV clearance in women have the ability to alter the host epithelial immune response, especially L. gasseri LGV03. Furthermore, L. gasseri LGV03 was able to enhance poly (I:C) induced production of type I IFN by modulating IRF3 pathway and attenuate poly (I:C) induced production of pro-inflammatory mediators by regulating NF-κB pathway, indicating that L. gasseri LGV03 keep the innate system alert to potential pathogens and reduces the inflammatory effects when there is persistent pathogen infection. Then, studies on immunomodulatory activity in vivo showed that L. gasseri LGV03 can effectively inhibit the proliferation of Ect1/E6E7 cells in zebrafish xenografts by enhancing the immune response of zebrafish, and not induce inflammatory response in vivo, indicating that L. gasseri LGV03 has the potential to shape the immune response.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is a serious threat to women's health, its incidence ranks second among cancers in women [1,2]. The host immune system is able to clear the virus in most HPV patient [3]. Nevertheless, the HPV virus could subvert the host's defense mechanisms, causing persistent infection that may lead to cervical cancer [4]. HPV primarily infects the genital epithelium and replicates within the vaginal keratinocytes [5], which play a crucial role in innate and adaptive immunity [6]. However, HPV can evade immune attack via several mechanisms [4]. There is increasing evidence to indicate that HPV viruses can interfere with the expression of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and regulate TLR signaling pathways to induce persistent infection [7]. The HPV16 E6 protein interacts with IRF-3 to downregulate the expression of IFN-α and IFN-β [8]. Britto et al. [9] observed a significant decrease in mRNA expression of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize RNA (including TLR3/7) in cervical samples. Both of these help HPV evade the host's innate immune response. However, most HPV infections are cleared and do not lead to cervical cancer because an adequate immune response can control the infection and prevent its progression to precancerous lesions [10]. This results suggested that additional factors act in conjunction with HPV to influence the immune response. Therefore, persistent HPV infection is caused by multiple factors, and further studies are required to improve our understanding of its etiology.

There is emerging evidence to suggest that the host's vaginal microbiota plays a crucial role in the process of HPV infection [11,12]. Defense mechanisms against colonization of the vagina by pathogenic organisms include the presence of lactic acid-producing Lactobacillus species [13], [14], [15], [16]. Disruptions to these defense mechanisms, as may occur with vaginal microbiome dysbiosis, may modulate the risk of viral infections [17,18]. Several studies have shown that commensal microbiota perform various immunologic functions in mammals [19,20]. The role of commensal microbiota in the regulation of antiviral immunity has been studied widely [21,22]. The intestinal microbiota releases signals for inflammasome activation [21] and calibrates IFN responsiveness by providing tonic signals [22]. A large number of retrospective studies have demonstrated that changes in cervico-vaginal microbiota with Lactobacillus depletion facilitate HPV infection and might be involved in viral persistence and cancer development [12,[23], [24], [25], [26]]. However, the immunomodulatory effect of Lactobacillus microbiota isolated from cervico-vaginal samples of HPV clearance in women has not been reported. The physical barriers of the female reproductive tract are essential to the host defense against pathogens [27], [28], [29], which can regulate the movement of molecules [30]. Moreover, the secretion of immune chemokines is central to the activation of tissue resident immune cells [31].

In the present study, differences in the cervicovaginal levels of TLRs, proinflammatory and chemoattractant cytokines were assessed in women with persistent HPV infection and HPV clearance. We examined the effects of Lactobacillus reuteri LRV03, Lactobacillus vaginalis LVV03, Lactobacillus jannaschii LJV03, and Lactobacillus gasseri LGV03 isolated from cervicovaginal samples from women with successful HPV clearance on the host epithelial immune response in ectocervical cells. We also used Ect1/E6E7 cells to investigate the antiviral effects of L. gasseri LGV03. A viral response was induced by treating Ect1/E6E7 cells with poly (I:C) and examining changes in the expression of inflammatory cytokines, IFNs, signaling molecules (IRF-3 and IκB-α), and TLRs. In vivo studies in a zebrafish xenograft model confirmed the ability of L. gasseri LGV03 to beneficially modulate the immune response to inhibit the proliferation of Ect1/E6E7 cells. Moreover, L. gasseri LGV03 did not induce inflammation in zebrafish larvae.

Materials and methods

Materials

The CaSki human cervical cancer cell line (ATCC: CRL-1550) and HPV-negative cervical carcinoma cells C33A (ATCC: HTB-31) were purchased from the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences. The Ect1/E6E7 human cervical squamous epithelial immortalized cell line (ATCC: CRL-2614) was purchased from Shanghai Baili Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Rabbit anti-RIG-I, rabbit anti-MDA-5, rabbit anti-MAVS, rabbit anti-p-IKB-α (Ser32), rabbit anti-TRAF3, rabbit anti-TBK1, rabbit anti-p-IRF3 (Ser396), rabbit anti-IRF3, rabbit anti-TLR3, β-actin rabbit antibody, and horseradish peroxide enzyme-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody were purchased from Beijing Beyotime. Human cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead Luminex panel I (45-plex) was purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Cell culture

Ect1/E6E7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). CaSki cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS. Both cell lines were cultured in an incubator at 37 °C in atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Sample collection and transportation

Patients with HPV infection who were admitted to the Department of Cervical Medicine of the Eighth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University from June 2018 to July 2021 were enrolled in our study. All patients were in the non-menstrual phase of their cycle and had no history of oral antibiotics or vaginal lavatory administration within one week. After HPV typing test, TCT examination, routine leucorrhea examination, and colposcopy and pathological biopsy for mycoplasma, chlamydia, and gonorrhea, patients were divided according to HPV infection history and colposcopic cervical pathological biopsy into HPV persistent infection and HPV clearance groups. The present study was approved by the medical ethics review of the Eighth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (Approval No.: 2019–060–01).

The inclusion criteria were: (1) female patients with HPV infection (HPV+) who were not pregnant or lactating and aged 18–65 years; (2) those without medication intervention or other treatment; (3) those with no experience of vaginal microflora suppository intervention or major vaginal surgery; and (4) those with good compliance. Before sampling, all selected patients had a detailed understanding of the sampling process and research purpose and signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who were pregnant, lactating, and in menopause; (2) those with mental illness, cognitive impairment, and autonomic ability; (3) patients receiving immunomodulators; and (4) patients with a history of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and tumor, or combined with other tumors or other major diseases. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. There was no difference in age between the HPV+ clearance (mean age, 31.96 ± 1.78 years) and the HPV+ persistent infection (mean age, 37.86 ± 2.53 years) groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristics | HPV+ Persistence group (n = 20) |

HPV+ Clearance group (n = 21) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range (mean ±SE) | 24–61 (37.86±2.53) | 22–52 (31.96±1.78) | 0.14a |

| HPV type, n (%) | Persistent HR-HPV 20 (100%) | HPV negative 0 (0%) | <0.001b |

| ThinPrep cytological test, n (%) | Inflammatory reaction 12 (60.00%) |

Inflammatory reaction 11 (52.38%) |

0.76b |

| Abnormal vaginal discharge, n (%) | WBC++ 5 (25.00%) | WBC++ 6 (28.57%) | 1.00b |

| Mycoplasma, n (%) | 6 (30.00%) | 6 (28.57%) | 1.00b |

| Chlamydia, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | / |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | / |

| Colposcopy+biopsy, n (%) | CIN 3 (15.00%) | 0 (0%) | 0.11b |

Independent t-test.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

cP-value < 0.05 considered significant.

Two sterile cotton swabs (Longsee Biomedical Corporation, Guangzhou, China) were inserted into the vaginal fornix and rotated clockwise 10 times to obtain genital tract secretion samples. One cotton swab was stored in 0.9% sterile normal saline: glycerin [20% (v/v)] at −80 °C to isolate Lactobacillus strains. The other cotton swab was stored in reproductive tract microbial genome protection solution at −80 °C for DNA extraction. A cell brush was gently inserted into the cervix and rotated 360° to obtain a cell sample, which was then placed in 5 mL of RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 4 °C and transferred to the laboratory for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis.

Analysis of mRNA expression of cervical cytokines

Total RNA was extracted from each cervical cell sample using TRIzol reagent (Tiangen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentration and purity were determined using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (NanoDrop2000, Thermo). RNA integrity was examined using denatured polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. qPCR was performed in cDNA samples using Realtime PCR Master Mix (SYBR Green). The primer sequences of each gene are shown in Table 2. Cycle threshold (Ct) data were obtained using Bio-Rad Prism sequence detection software in the fluorescence qPCR instrument. Target genes were normalized to the housekeeping gene, GAPDH, and the relative expression was calculated converting the difference in cycle thresholds (ΔCt) using the 2−ΔCt method.

Table 2.

Primer sequences used in this study.

| Gene name | Sequences (5′−3′) |

|---|---|

| IL-6 | F: ATTTCCTCTTGGTCTTCTG R: GGTCCTTAGCCACTCCTT |

| IL-1β | F: GGCAGGCAGTATCACTCATT R: 5CCCAAGGCCACAGGTATTT |

| IL-8 | F: TTGCCTTGACCCTGAAGCCCCC R: GGCACATCAGGTACGATCCAGGC |

| TNF-α | F: ACTGAACTTCGGGGTGAT R: ACTTGGTGGTTTGCTACG |

| MCP-1 | F: AAACTGAAGCTCGCACTCGC R: ATTCTTGGGTTGTTGAGTGAGT |

| IFN-α | F: GAGCAATGCTTGGACAGCAG R: GAGGTTGTGGATGTGCAGGA |

| IFN-β | F: AGTTACACTGCCTTTGCC R: TCTGCTCGGACCACCATC |

| TLR3 | F: CCTGGTTTGTTAATTGGATTAACGA R: TGAGGTGGAGTGTTGCAAAGG |

| TLR4 | F: GGACTGGGTAAGGAATGAGCTAGTA R: CACACCGGGAATAAAGTCTCTGT |

| TLR9 | F: TGAAGACTTCAGGCCCAACTG R: TGCACGGTCACCAGGTTGT |

| GAPDH | F: AAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTT R: ACCAGAGTTAAAAGCAGCCCTG |

Isolation of lactobacillus strains

Cervical and vaginal secretions were subjected to gradient dilution and then coated on MRS agar plate, followed by culturing in anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 48 h. Single colonies of different forms were then selected from the plate and streaked onto a MRS AGAR plate. Pure colonies on the plate were inoculated into MRS broth (Qingdao High-Tech Industrial Park Haibo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), cultured in an anaerobic environment at 37°C for 16 h, followed by addition of 20% glycerol, and stored at -80°C.

The 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using 27F (5′ -AgAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAg-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) universal primers. The PCR reaction was performed using a final volume of 25 μL, including 5 µL of 5 × TransStart FastPfu Buffer, 2 µL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.5 µL of TransStart FastPfu DNA, 1 μL of 27F, 1 μL of 1492R primers, and 15.5 μl of ddH2O. Single colonies were cultured for 24 h then added to each reaction system. The PCR conditions were as follows: initial activation at 95°C for 2 min; 5 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 60 s, for a total of 30 cycles and the last cycle was performed at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were placed in 1% agarose gel and stained with EB solution for electrophoresis. Sequencing was performed by Suzhou Jinweizhi Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The amplified 16S rRNA gene sequence was subsequently compared with the GenBank database using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST).

Preparation of bacterial strains

L. reuteri LRV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. jannaschii LJV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 were inoculated in MRS broth and cultured at 37 °C for 16 h. Bacterial precipitates were then collected by centrifuging at 4000 × g for 10 min, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and suspended in RPMI 1640 medium or DMEM medium before adjusting the concentration to 1 × 107 CFU/mL.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined using the trypan blue dye rejection test. Ect1/E6E7 and CaSki cells were inoculated in 24-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well) and transferred to a cell culture box containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for overnight inoculation. The original medium was then replaced with fresh medium with or without L. reuteri LRV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. jannaschii LJV03, or L. gasseri LGV03 at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/mL for incubation at 37°C for 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. The cell suspension was then mixed with 0.4% trypan blue solution (Wuhan Procell Life Science and Technology Co., Ltd.) and incubated for 5 min before observing the cells using an inverted biological microscope (ICX41, Soptop) and counting the living cells using a blood cell counter. Six multiple holes were set for the analysis. Percentage cell viability was calculated as: (live cells/total cell count) × 100%.

Luminex detection

Ect1/E6E7 and CaSki cells were inoculated in 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) and transferred to a cell culture box containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for overnight inoculation. The original medium was then replaced with fresh medium with or without L. reuteri LRV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. jannaschii LJV03, L. gasseri LGV03 at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/mL for incubation at 37°C for 48 h and the supernatant collected. A 45-plex human cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead Luminex panel I (Lot: 242,751–002, Invitrogen) was used to detect cytokines/chemokines in the supernatant. Samples were tested in triplicate using Luminex Corporation according to manufacturer's instructions. Luminex Xponent 3.1 software was used to fit the standard curve and analyze the data.

Morphological identification of L. gasseri LGV03

L. gasseri LGV03 was streaked onto MRS solid medium and cultured at 37°C for 48 h in an anaerobic workstation (E500G, GeneScience, USA) to observe the macroscopic morphology of the colonies. L. gasseri LGV03 was identified by Gram staining.

Hemolysis test

L. gasseri LGV03 was inoculated on Colombian blood AGAR plate (Qingdao High-Tech Industrial Park Haibo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), using Listeria innocua CICC 10,417 as a negative contrast bacterium and Staphylococcus aureus CICC 10,473 as a positive contrast bacterium.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of L. gasseri LGV03

L. gasseri LGV03 was inoculated in MRS broth at 37 °C for 16 h. Bacterial precipitates were collected by centrifuging at 4000 × g for 10 min, washed twice with PBS, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 12 h, then washed three times with PBS, dehydrated with ethanol solution using a concentration gradient of 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 95% (15 min under each concentration), and treated with 100% ethanol twice for 20 min each. The samples then underwent critical point drying and coating before being observed under a biometric SEM (Zeiss Gemini 300).

Whole-genome sequencing analysis

Sequencing and bioinformatics analysis were commissioned by China Industrial Microbial Species Preservation and Management Center. The L. gasseri LGV03 genome was sequenced using the BGI sequencing platform and assembled using SPAdes V3.11.0. Prodigal (version: V2.6.3) software was used to conduct gene prediction for L. gasseri LGV03. The protein sequences of the predicted genes were compared with The GOG, KEGG, and GO databases in terms of blastp (BLAST 2.2.28+) to obtain the annotation information of the predicted genes.

Short chain fatty acid (SCFA) profile of L. gasseri LGV03

The SCFA concentration in the culture supernatant of L. gasseri LGV03 was determined using liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC–MS). Briefly, L. gasseri LGV03 was inoculated in MRS broth for 16 h at 37 °C, followed by centrifuging at 4000 × g for 10 min to collect the supernatant, which was filtered using a 0.22-μm sterile filter. An ACE (Aberdeen, Scotland) Excel2C-18PFP (100 × 2.1 mm, 2 μm) column and C18 guard column were used for LC–MS. Mobile phase A was water containing 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase B was acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. The sample size was 2 μL and the column was kept at 35°C.

SEM analysis of adhered L. gasseri LGV03 toward Ect1/E6E7 cells

Ect1/E6E7 cells were inoculated in 6-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well) and transferred to a cell culture box containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for overnight inoculation. The original medium was then replaced with fresh medium with or without L. gasseri LGV03 at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/mL for incubation at 37°C for 2 h to collect the supernatant. The supernatant was washed with PBS three times to remove unattached L. gasseri LGV03, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 12 h, then washed three times with PBS, dehydrated with ethanol solution using a concentration gradient of 30, 50, 70, 80, 90 and 95% (15 min for each concentration), and treated with 100% ethanol twice for 20 min each. The samples underwent critical point drying and coating before being observed under a biometric SEM (Zeiss Gemini 300).

Analysis of antiviral activity of L. gasseri LGV03 in Ect1/E6E7 cells

Ect1/E6E7 cells were inoculated in 6-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well) and transferred to a cell culture box containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for overnight inoculation. The original medium was then replaced with fresh medium with or without L. gasseri LGV03 at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/mL for incubation at 37°C for 48 h to collect the supernatant. The supernatant was washed with the fresh medium for three times to remove the unattached L. gasseri LGV03 and then stimulated with 10 μg/mL poly (I:C) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 12 h. Finally, the cells were collected for total RNA extraction. The mRNA expression levels of IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and IL-1β were quantified by qRT-PCR, and the relative number of copies of cDNA in each sample was calculated using GAPDH as the calibration gene using the ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences of each gene are shown in Table 2.

Western blot analysis

Ect1/E6E7 cells (2 × 107 cells/petri dish) were inoculated in 60-mm petri dishes and transferred to a cell culture box containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for overnight inoculation. The original medium was then replaced with fresh medium with or without L. gasseri LGV03 at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/mL for incubation at 37°C for 48 h to collect the supernatant. The supernatant was washed with fresh medium three times to remove unattached L. gasseri LGV03 and then stimulated with 10 μg/mL poly (I:C) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 12 h. Ect1/E6E7 cells from each group were collected by washing twice with PBS, followed by the addition of the freshly prepared RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor, and then iced for 30 min and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min to collect the supernatant for quantitative analysis of protein using the BCA method. Protein samples (50 μg) were loaded for SDS-PAGE analysis. After membrane transfer, TBST containing 5% skim milk powder was used to block for 2 h, and primary antibody was added for incubation overnight at 4°C. On the second day, the membranes were washed three times with TBST (for 10 min each) then horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (1:10,000) was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h and washed three times with TBST (10 min each). Finally, ECL chemiluminescence was used for colorations and Quantity One software was used to analyze related protein expression.

Zebrafish xenografts implantation and treatment

MRS broth was inoculated with L. gasseri LGV03 and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Bacterial precipitates were collected by centrifuging at 4000 × g for 10 min, washed twice with PBS, resuspended in embryo medium E3 (5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2, 0.33 mM MgSO4) and adjusted to 1 × 106 CFU/mL and 1 × 107 CFU/mL. Ect1/E6E7 cells or C33A cells were labeled with 2 μg/mL DiI fluorescence and incubated at 37°C for 20 min under dark conditions. Subsequently, 10–50 nL (1 × 107 cells/mL) cells were implanted into the yolk sac center of 48-h post-fertilization transgenic zebrafish (fil1:EGFP) or wild type AB line zebrafish using a microsyringe. Zebrafish were transferred to 48-well plates (1 zebrafish/well) containing 2 mL of L. gasseri LGV03 (1 × 106 CFU/mL, 1 × 107 CFU/mL) and incubated at 28 °C for 72 h. Fresh L. gasseri LGV03 solution was replaced every 24 h and embryo medium E3 was used as contrast solution. The effect of L. gasseri LGV03 on Ect1/E6E7 cells was observed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

Retention characteristic of probiotic strains in zebrafish

The bacterial culture was centrifuged at 4000 × g for 10 min to remove the supernatant from the medium. The cell pellet was washed twice with PBS. Then it was resuspended in embryo medium E3 at final concentrations of 1 × 106 CFU/mL and 1 × 107 CFU/mL. The Wild-type AB zebrafish larvae at 3 days post-fertilization (dpf) were transferred into six-well sterile plates (10 fish each well). Zebrafish larvae were exposed to L. gasseri LGV03 at final concentrations of 1 × 106 CFU/mL and 1 × 107 CFU/mL for 48 h at 28 °C. Fresh L. gasseri LGV03 solution was replaced every 24 h. After the incubation, the zebrafish larvae from each group were washed five times with embryo medium E3 to remove the bacteria adhered to the surface and then photographed by fluorescent microscope (Leica, Germany) to detect the existence of L. gasseri LGV03 in the gastrointestinal tract.

The immunomodulatory effects of L. gasseri LGV03 in zebrafish

Bacterial precipitates were collected by centrifuging at 4000 × g for 10 min, washed twice with PBS, resuspended in embryo medium E3 and adjusted to 1 × 106 CFU/mL and 1 × 107 CFU/mL. Tg (mpx: EGFP) transgenic zebrafish larvae at 3 dpf were exposed to L. gasseri LGV03 at final concentrations of 1 × 106 CFU/mL and 1 × 107 CFU/mL in six-well sterile plates (10 fish each well) for 48 h at 28 °C. Fresh L. gasseri LGV03 solution was replaced every 24 h. The neutrophils were imaged using fluorescent microscope (Leica, Germany) and counted by using ImageJ software (version1.8.0).

Measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) production in zebrafish model

The fluorescent probe dyes, DCF-DA (Sigma-Aldrich) and DAF-FMDA (Sigma-Aldrich), were used to estimate the ROS and NO production in the zebrafish model, respectively. L. gasseri LGV03 was inoculated in MRS broth at 37 °C for 16 h. Bacterial precipitates were collected by centrifuging at 4000 × g for 10 min, washed twice with PBS, resuspended in embryo medium E3 and adjusted to 1 × 106 CFU/mL and 1 × 107 CFU/mL. Healthy wild type AB line zebrafish developed to 4 dpf were selected and placed in 6-well cell culture plates, with 15 fish per well. Blank control, model (lipopolysaccharide; LPS), and L. gasseri LGV03 (1 × 106 CFU/mL, 1 × 107 CFU/mL) groups were set up, with 15 fish per group. The blank control group was incubated with embryo medium E3, the model group was incubated with 5 μg/mL LPS solution (LPS dissolved in embryo medium E3), and the L. gasseri LGV03 group was incubated with 1 × 106 CFU/mL and 1 × 107 CFU/mL (5 mL per well), followed by incubation at 28°C for 24 h, discarding the above solution. The zebrafish were then washed three times with PBS and treated with DCF-DA (20 μg/mL) or DAF-FMDA (5 μM) solution (3 mL per well) and incubated at 28 °C for 1 h under dark conditions. The zebrafish were washed three times with PBS and placed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany) to observe the fluorescence intensity and obtain photographs. Image J software was used for quantitative statistical analysis of fluorescence intensity in zebrafish.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± standard error. Comparisons between the HPV+ clearance and HPV+ persistence group were performed by Mann–Whitney U test using GraphPad Prism 9 software, whereas comparisons between multiple groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey multiple range test using SPSS 17.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Significant differences were marked as *(P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), ***(P < 0.001), or ****(P < 0.0001). For multiple comparisons between mean values, P < 0.05 was considered significant and indicated with different superscript letters.

Results

Study participants

Clinical and demographic information of the patients enrolled in the study are shown in Table 1. There were no differences between the HPV+ persistence and HPV+ clearance groups in terms of age (mean 37.86 ± 2.53 vs. 31.96 ± 1.78 years, respectively; P = 0.14) or number of women reporting abnormal vaginal discharge [5/20 (25.00%) vs. 6/21 (28.75%), P = 1.00]. There was no difference in mycoplasma detected between the HPV+ persistence (6/20; 30.00%) and HPV+ clearance (6/21; 28.75%, P = 1.00) groups. No participants were infected with Chlamydia or Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Effect of persistent HPV infection on cytokines and TLR pathogen recognition receptor mRNA expression

We analyzed the mRNA expression of TLR pathogen recognition receptors and cytokines to examine the changes in the host immune response relative to the HPV status and microbiome changes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

TLR and cytokine expression levels in cervical cells of HPV+ clearance and HPV+ persistence patient. Relative expression of target genes was normalized to GAPDH (2−ΔCt). Box plots represent 10–90 percentile; Mann-Whitney U test; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

First, we evaluated expression levels of TLRs that play a key role in innate immune response. In samples from women with persistent HPV infection, expression levels of TLR3 and TLR4 were significantly downregulated (P < 0.01), whereas TLR9 was significantly upregulated (P < 0.05). We examined cytokines essential to the innate and adaptive immune response since HPV has been shown to induce both immune responses. IFN-α and IFN-β are key cytokines expressed downstream from innate immune activation. Compared with samples from the HPV+ clearance group, the expression levels of IFN-α and IFN-β were significantly downregulated in the HPV+ persistence group (P < 0.05). In addition, compared with the HPV+ clearance group, the HPV+ persistence group had similar levels of IL-1β and TNF-α but higher levels of IL-6 (P < 0.05) and IL-8 (P < 0.01). These data suggest that the antiviral response could be impaired due to decreased TLR3 and type I IFNs expression. Hence, infected cells are not able to initiate a robust response, which potentially facilitates HPV persistence.

Lactobacillus species alter the host epithelial immune response in human ectocervical Ect1/E6E7 and cervical CaSki cells

A growing number of retrospective studies have suggested that the depletion of Lactobacillus microbiota in the cervico-vagina contributes to persistent HPV infection [12,[23], [24], [25], [26]]. Therefore, we further investigated the immunomodulatory role of Lactobacillus microbiota isolated from cervico-vaginal samples of HPV clearance in women.

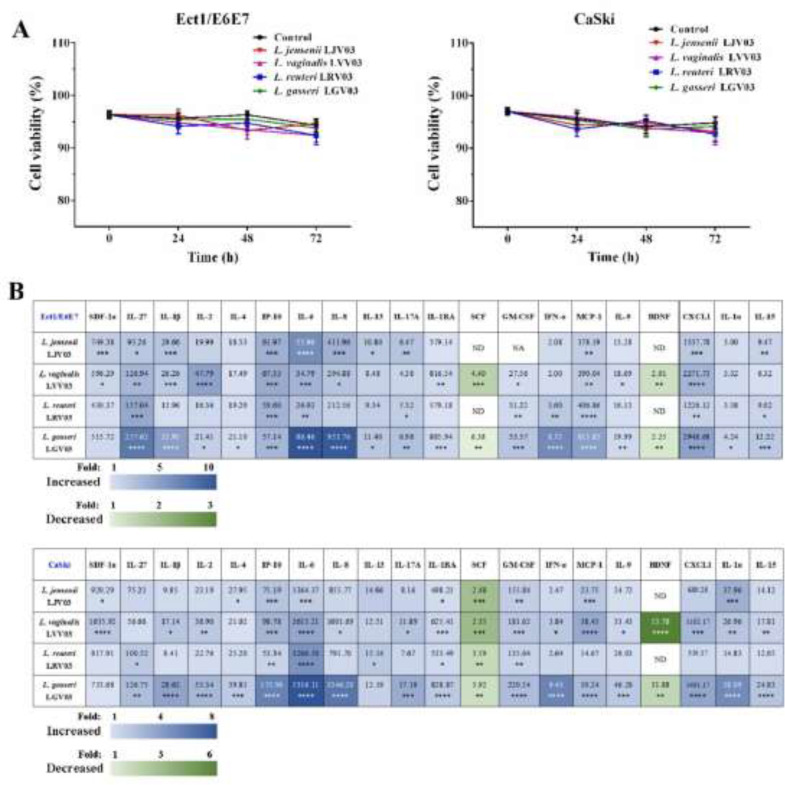

L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 were isolated from cervicovaginal samples from women in the HPV clearance group and identified by 16S RNA, named, and stored in our laboratory. The cytotoxicity of L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 was evaluated using trypan blue dye exclusion assay. The cell survival rate decreased slightly in response to 24 to 72-h exposure to 1 × 107 CFU/mL L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 (Fig. 2A). This indicated that L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 do not significantly affect the cytotoxicity of Ect1/E6E7 and CaSki cells. Consequently, further experiments to assess the antiviral activity were carried out at this concentration in the present study.

Fig. 2.

Effect of L. jensenii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 on viability and host epithelial immune response of Ect1/E6E7 and CaSki cells. (A) Effects of L. jensenii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 on Ect1/E6E7 and CaSki cells proliferation. (B) Immune cytokines/chemokines released from Ect1/E6E7 and CaSki cells after exposure to L. jensenii, L. vaginalis, L. reuteri, and L. gasseri (1 × 107 CFU/mL) for 48 h were measured by Luminex. Heat map depicts fold change by color, p-value by asterisks, and concentration (pg/mL) of each analyte by the number value present in each corresponding box. one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. ND: Non-Detectable.

We examined whether L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 could alter the host's epithelial immune response. We performed a discovery-based multiplex Luminex assay to assess the immune profile of Ect1/E6E7 and CaSki cells after exposure to L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03. Overall, the results of the Luminex assay revealed a significantly varied and diverse immune profile between untreated (control) cells and those exposed to L. jannaschii LJV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. reuteri LRV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 (Fig. 2B, Tables S1 and S2). After focusing only on those cytokines/chemokines exhibiting greater than a fivefold change with a significant P-value < 0.05, IL-6 (5.90-fold) increased in response to L. jensenii LJV03 in Ect1/E6E7 cells and IL-27 (7.04-fold), IL-6 (9.12-fold), IL-8 (8.80-fold), and IFN-α (5.98-fold) increased in response to L. gasseri LGV03 in Ect1/E6E7 cells (Fig. 2B). In addition, L. gasseri LGV03 significantly increased the secretion of IL-6, IL-8, IFN-α, and IL-1α in CaSki cells (P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Secretion of IL-6, IL-8, IFN-α, and IL-1α increased 7.93, 6.31, 5.63, and 5.26-fold, respectively. These results suggest that L. gasseri LGV03 was most efficient for mediating the host epithelial immune response. Therefore, L. gasseri LGV03 was selected for further experiments.

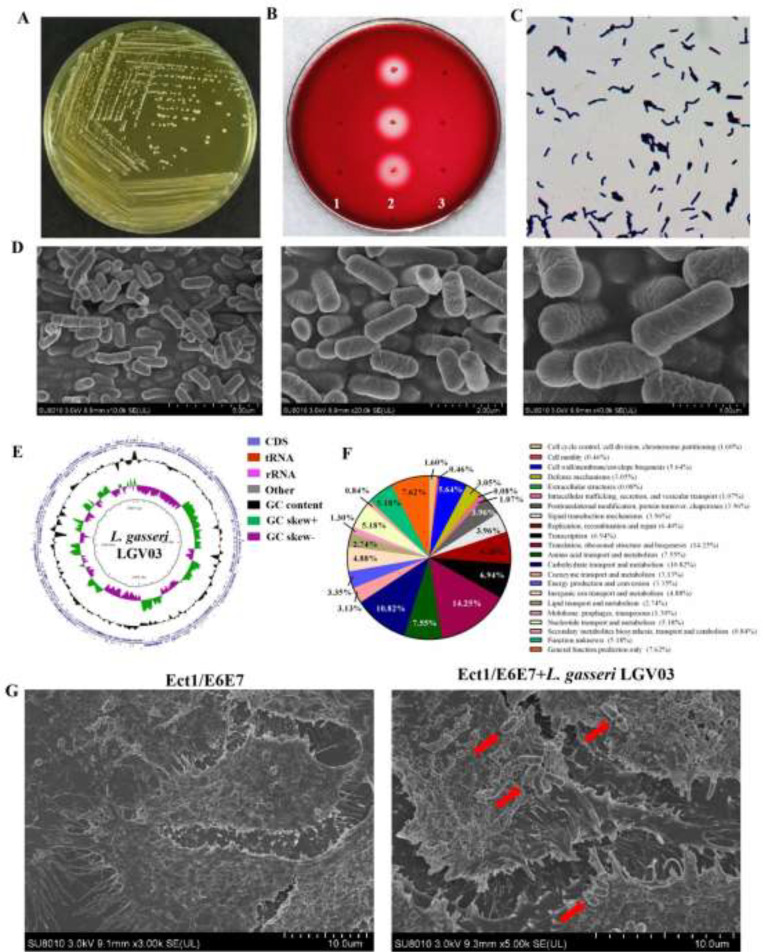

Morphological characteristics and biological properties of L. gasseri LGV03

L. gasseri LGV03 grows well on MRS medium. After a 48 h culture, the bacterial colonies were round, milky, waxy and white, the edge was clear and neat (Fig. 3A). Compared with positive control, S. aureus CICC 10,473, which has blood hemolysis activity, L. gasseri LGV03 showed no hemolytic activity, which was the same as the negative control (L. innocua CICC 10,417) (Fig. 3B). Gram staining and direct observation by scanning electrochemical microscopy showed the strain was Gram positive and rod-shaped with rounded ends (Fig. 3C and D).

Fig. 3.

Characterization and whole genome sequencing of L. gasseri LGV03. (A) L. gasseri LGV03 colonies on MRS agar cultured anaerobically after 48 h at 37 °C. (B) L. gasseri LGV03 colonies after culturing for 48 h on Columbia blood agar. 1 (negative control): Listeria innocua (CICC 10,417); 2 (positive control): Staphylococcus aureus (CICC 10,473); 3: L. gasseri LGV03. (C) Gram staining properties of L. gasseri LGV03. (D) Scanning electron microscope observation of L. gasseri LGV03. (E) The graphical circular map of the L. gasseri LGV03 genome. (F) COG function classification of L. gasseri LGV03. (G) Scanning electron microscope analysis of Ect1/E6E7 cells where the L. gasseri LGV03 adheres to the surface monolayer of cells. Red arrow indicates attachment of L. gasseri LGV03 to Ect1/E6E7 cells.

SCFAs are reported to affect epithelial cell metabolism and innate inflammatory response [16,32]. In particular, butyrate may reverse the course of otherwise lethal sepsis by enhancing pathogen clearance via the restoration of host immunity in an IRF3-dependent manner [33]. Acetate, propionate, butyrate, and isovalerate are usually found in the vaginal environment [34]. We assessed the production of SCFAs in culture supernatants of L. gasseri LGV03 using LC–MS. Acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, and isovaleric acid were the dominant SCFA produced by L. gasseri LGV03 (Table 3).

Table 3.

The production of SCFAs in culture supernatant of L. gasseri LGV03.

| SCFAs | Concentration (ng/mL) | SCFAs | Concentration (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic acid | 33,491.71±137.71 | 2,2-Dimethylbutanoic acid | ND |

| Propionic acid | 75.44±1.03 | 2-Ethyl butyric acid | ND |

| Isobutyric acid | ND | 3,3-Dimethylbutanoic acid | ND |

| Butyric acid | 32.25±1.10 | 2-Methylvaleric acid | ND |

| 2-Methylbutyric acid | ND | 3-Methylvaleric acid | ND |

| Isovaleric acid | 29.28±0.09 | 4-Methylvaleric acid | ND |

Genetic characteristics of L. gasseri LGV03

The entire genome of L. gasseri LGV03 was sequenced to look for other possible characteristics. A graphical circular map of the L. gasseri LGV03 genome is presented in Fig. 3E and the general features of the genome are listed in Table 4. The genome of L. gasseri LGV03 was assembled into a single circular chromosome composed of 1982,292 bp with 34.85% GC content. Genome sequencing also revealed that L. gasseri LGV03 was a plasmid-free bacterium. A total of 1971 genes, five rRNAs (including 5S, 16S, and 23S genes), 45 tRNA, and 53 ncRNA were found in the circular chromosome of L. gasseri LGV03. BLAST analysis of the VFDB and VirulenceFinder was unable to identify virulence factor genes in the genome of L. gasseri LGV03. In addition, no antibiotic resistance genes were found in L. gasseri LGV03 using CARD and ResFinder. We previously reported the antibiotic susceptibility of L. gasseri LGV03 [35] and showed it was sensitive to penicillin, ampicillin, meropenem, vancomycin, erythromycin, and linezolid, with minimum inhibitory concentration values of 0.048, 0.19, 0.38, 0.75, 0.064, and 0.75 µg/mL, respectively, and resistant to clindamycin (6 µg/mL). Therefore, these data suggest that L. gasseri LGV03 can be considered safe, without potential virulence factors or risk of spreading antibiotic resistance genes.

Table 4.

General features of L. gasseri LGV03 genome.

| Attribute | Values |

|---|---|

| Min sequence length | 517 bp |

| Max sequence length | 178,370 bp |

| Total sequence number | 45 |

| N50 length | 84,973 |

| N90 length | 28,115 |

| Total sequence length | 1982,292 |

| G + C content (%) | 34.85% |

| Predicted genes | 1971 |

| Plasmid | Not reported |

| rRNA genes (5S, 16S, 23S) | 5 (3, 1, 1) |

| tRNA genes | 45 |

| ncRNA | 53 |

COG database annotations are shown in Fig. 3F. The largest part of this subsystem is allocated to translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (14.25%), carbohydrate transport and metabolism (10.82%), general function prediction only (7.62%), amino acid transport and metabolism (7.55%), transcription (6.94%), replication, recombination, and repair (6.40%), and cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (5.64%). The enriched GO function and KEGG pathway analysis of L. gasseri LGV03 is shown Fig. S1A and S1B. The top three enriched biological processes included catalytic activity (16.69%), metabolic process (15.49%), and binding (13.29%). It is noteworthy that L. gasseri LGV03 contains biological functions of genes related to regulation of biological process (2.49%) and biological adhesion (0.05%).

SEM analysis of adherence of L. gasseri LGV03 to Ect1/E6E7 cells

Adhesion of Lactobacilli is essential for exertion of beneficial probiotic effects in the vagina [36]. In the present study, adhesion of L. gasseri LGV03 to Ect1/E6E7 cells was verified by SEM. Fig. 3G shows the presence of rod-shaped L. gasseri LGV03 forming short chains or in pairs adhering to the surface of Ect1/E6E7 cells, which may contribute to limiting the colonization of pathogenic microorganisms and may modulate the host immune system [37,38].

Immunomodulatory activity of L. gasseri LGV03 in Ect1/E6E7 cells

Previous in vitro studies have shown that challenging human intestinal epithelial cells with the TLR3/RIG-I agonist, poly (I:C), could be effectively used for the screening and selection of immunobiotic strains with antiviral activity [39,40]. Therefore, we examined the effect of L. gasseri LGV03 on the innate immune response of Ect1/E6E7 cells after poly (I:C) challenge. Expression of IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and IL-1β were determined after poly (I:C) stimulation (Fig. 4). Poly (I:C) significantly increased the expression of all the inflammatory factors evaluated compared with untreated control cells, in line with previous findings [40,41]. L. gasseri LGV03 significantly increased the production of IFN-a and IFN-β in Ect1/E6E7 cells in response to poly (I:C) stimulation. However, L. gasseri LGV03 significantly reduced the expression of the proinflammatory chemokines IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β compared with those in the poly (I:C)-challenged control Ect1/E6E7 cells. No changes in the expression of MCP-1 were observed in L. gasseri LGV03-treated cells compared with poly (I:C)-challenged control Ect1/E6E7 cells. These results allow us to speculate that L. gasseri LGV03 has the capacity to improve antiviral defenses and/or modulate inflammation-mediated damage.

Fig. 4.

Antiviral activities of L. gasseri LGV03 in human ectocervical Ect1/E6E7 cells. After Ect1/E6E7 cells were treated with L. gasseri LGV03 and Poly (I:C), the expression of IFN-α, IFN-βIL-6, MCP-1, IL-8, and IL-1β were analyzed by RT-PCR. Cells treated with either Poly (I:C) or medium alone were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The positive control was used for comparison of L. gasseri LGV03 treated groups. The mean differences among the different superscript letters (a, b, C) were significant at 0.05 level. The results are expressed as mean ± SE and represent data from three independent experiments (n = 3 in each experiment).

Effect of L. gasseri LGV03 on signaling pathways in Ect1/E6E7 cells

We next evaluated whether L. gasseri LGV03 could modulate the IRF3 and NF-κB signaling pathways in Ect1/E6E7 cells in response to poly (I:C) challenge to gain more insight into the mechanisms of L. gasseri LGV03 on modulation of innate antiviral immune responses. Compared with poly (I:C) treatment, L. gasseri LGV03 was able to increase the levels of TLR3, TRAF3, TBK1, and p-IRF3 in Ect1/E6E7 cells post-treated with poly (I:C) (Fig. 5). On the contrary, poly (I:C) alone significantly increased the levels of RIG-I, MDA-5, MAVS, and p-IκB-α in Ect1/E6E7 cells, whereas L. gasseri LGV03-treated Ect1/E6E7 cells showed decreased expression of RIG-I, MDA-5, MAVS, and p-IκB-α after poly (I:C) challenge (Fig. 5). These results suggest that L. gasseri LGV03 can enhance poly (I:C)-induced production of type I IFN by modulating IRF3 pathway and attenuate poly (I:C) induced production of proinflammatory mediators by regulating the NF-κB pathway, indicating that L. gasseri LGV03 keeps the innate system alert to potential pathogens and reduces the inflammatory effects during persistent pathogen infection

Fig. 5.

Effect of L. gasseri LGV03 on NF-κB and IRF3 pathways in human ectocervical Ect1/E6E7 cells induced by poly (I:C) treatment. Ect1/E6E7 cells were pre-stimulated with L. gasseri LGV03 for 48 h, and then stimulated with Poly (I:C) for 12 h.

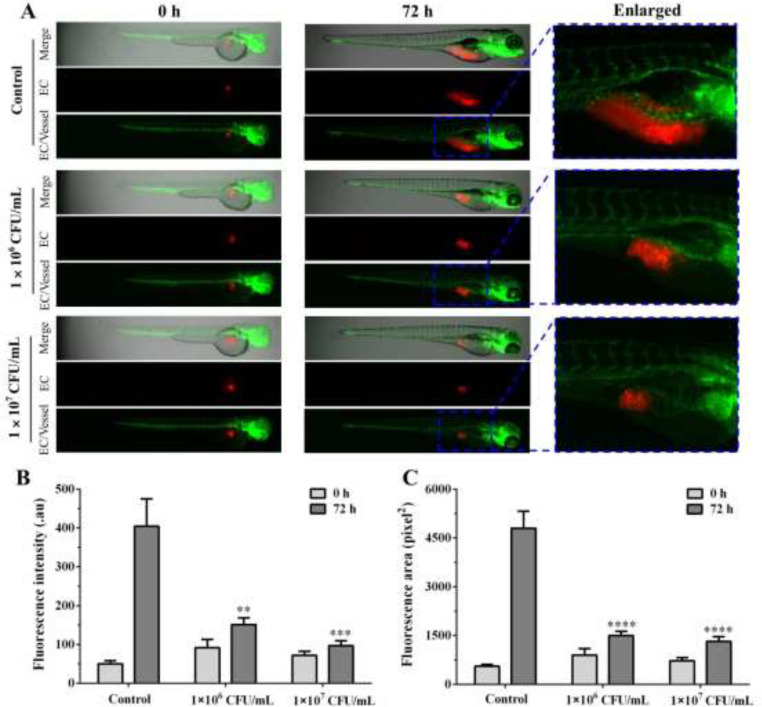

In vivo immunomodulatory effect of L. gasseri LGV03 in zebrafish

To confirm the in vivo immunomodulatory activity, the effects of L. gasseri LGV03 on the proliferation of Ect1/E6E7 cells in zebrafish were determined. Red fluorescence-labeled Ect1/E6E7 cells were microinjected into the perivitelline space of transgenic zebrafish embryos (fli1:EGFP) and different concentrations of L. gasseri LGV03 were added. A few red Ect1/E6E7 cells were distributed near the subintestinal vessel (SIV) area of zebrafish in the absence of L. gasseri LGV03 treatment at 0 h (Fig. 6A). In the control group, the number of Ect1/E6E7 cells increased in the SIV area at 72 h after xenotransplantation, suggesting the ability of the Ect1/E6E7 cells for infinite proliferation (Fig. 6A). However, the number of Ect1/E6E7 cells in the 1 × 106 CFU/mL L. gasseri LGV03-treated zebrafish group slightly increased at 72 h compared with that in the untreated control group (Fig. 6B and C). At 72 h after treatment with L. gasseri LGV03 (1 × 107 CFU/mL), the number of Ect1/E6E7 cells remained almost constant (Fig. 6B and C), suggesting that L. gasseri LGV03 can effectively suppress the proliferation of Ect1/E6E7 cells in zebrafish xenografts. Moreover, L. gasseri LGV03 had little effect on the proliferation of HPV-negative cervical carcinoma cells C33A in zebrafish xenografts, indicating that L. gasseri LGV03 may only affect the growth of HPV-positive cervical cancer cell lines Ect1/E6E7 in zebrafish (Fig. S2). In addition, L. gasseri LGV03 did not significantly affect the growth of Ect1/E6E7 cells in vitro (Fig. 2A). Thus, L. gasseri LGV03 markedly suppressed the growth of Ect1/E6E7 cells in zebrafish xenografts, which may be due to L. gasseri LGV03 increasing the immune response in zebrafish.

Fig. 6.

In vivo immunomodulatory effect of L. gasseri LGV03 in zebrafish. (A) DiI-labeled Ect1/E6E7 cells (EC, red) were implanted into the yolk sac of zebrafish embryos, and different concentrations of L. gasseri LGV03 (1 × 106 CFU/mL, 1 × 107 CFU/mL) were added. Fluorescence intensity (B) and fluorescent area (C) of xenografted Ect1/E6E7 cells were analyzed quantitatively. Fluorescent microscopy images of Ect1/E6E7 cells in zebrafish xenografts at 0 h and 72 h. The results are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 5). one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to control.

Immersed zebrafish using L. gasseri LGV03 with FITC labeling, the intestinal tract of zebrafish were observed under fluorescence microscope, as shown in Fig. S3. The fluorescence of intestinal bulb, mid-intestine and posterior intestine of zebrafish were clearly visible at 48 h, indicating that L. gasseri successfully colonized the gastrointestinal tract of zebrafish. In addition, the number of neutrophil in 5 dpf zebrafish larvae were significantly increased following exposure to 1 × 106 CFU/mL and 1 × 107 CFU/mL L. gasseri LGV03 relative to that of the control, suggesting that L. gasseri LGV03 was able to impact the immune system of zebrafifish (Fig. S4). Then, it is tempting to speculate that L. gasseri LGV03 could get into the intestinal tract of zebrafish where it played a potential role in immunomodulatory effects by interacting with the immune system. Overall, these results confifirmed that L. gasseri LGV03 was able to result in a significant improvement in tumor immune microenvironment, which was evidenced by a signifificant increase in the abundance of neutrophils.

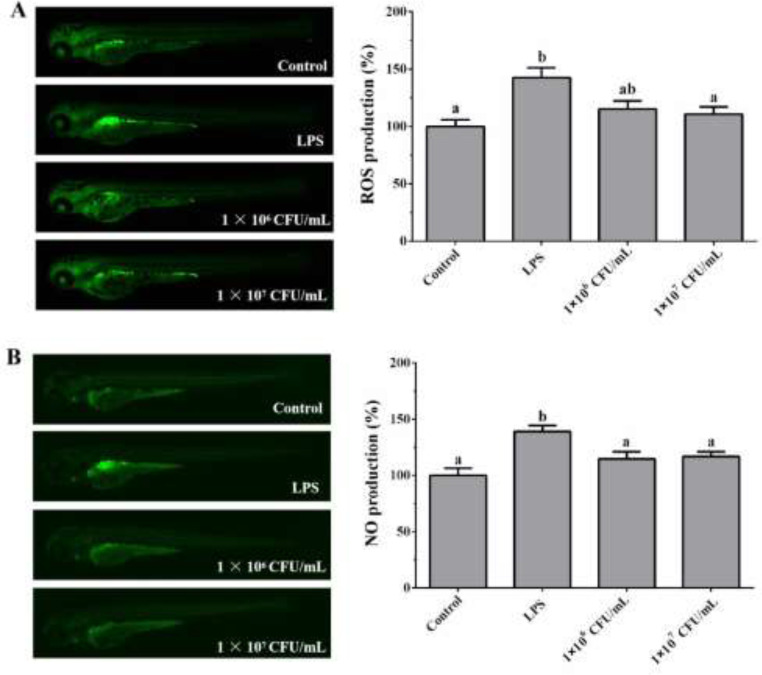

Previous in vitro studies indicated that L. gasseri LGV03 significantly induces proinflammatory cytokine production in Ect1/E6E7 and CaSki cells. Therefore, we examined whether L. gasseri LGV03 induced an inflammatory response in vivo. Excessive ROS and NO production significantly contributes to the pathogenesis of inflammation [42,43]; therefore, we measured ROS and NO production induced by L. gasseri LGV03 in zebrafish model. Fig. 7A and B show a typical fluorescence micrograph of the zebrafish. The negative control, which was not treated with LPS or L. gasseri LGV03, generated a clear image, whereas the positive control, which was treated with LPS only, generated a fluorescence image, indicating the production of excessive ROS and NO in zebrafish. However, when zebrafish larvae were treated with L. gasseri LGV03, the levels of ROS and NO generation did not increase significantly, suggesting that L. gasseri LGV03 did not induce an inflammatory response in vivo.

Fig. 7.

Effect of L. gasseri LGV03 on the ROS and NO production in the zebrafish larvae. The levels of ROS (A) and NO (B) generation were measured through image analysis and fluorescence microscopy. Experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 15 per treatment), and the data are expressed as mean ± SE. Different superscript letters (a, b and ab) indicate significant differences (p <0.05) among the groups.

Discussion

Persistent infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) is a primary cause of cervical cancer worldwide. An increasing number of retrospective studies have found the depletion of Lactobacillus microbiota in the cervico-vagina facilitate HPV infection and might be involved in viral persistence and cancer development [12,[23], [24], [25], [26]]. However, the immunomodulatory role of Lactobacillus microbiota isolated from cervico-vaginal samples of HPV clearance in women has not been reported. In our study, we assessed differences in genital immunology between persistent HPV infection and clearance. We also further evaluated the immunomodulatory role of Lactobacillus microbiota isolated from cervico-vaginal samples of HPV clearance in women. Our data indicated that the vaginal microbiota dominated by Lactobacilli, especially by L. gasser LGV03, may be able to suppress viral escape and restore immune homeostasis in cervical epithelial cells.

Most HPV infections are spontaneously cleared, viral persistence could lead to carcinogenesis [44,45]. However, in most cases of HPV infection, the virus can be cleared. The other factors act in conjunction with HPV to influence immune response [46]. More and more studies indicated that the vaginal microbiota play key role in the health of the lower female genital tract, especially in the persistent HPV-mediated cervical carcinogenesis [47,48]. Substantial evidence suggest that vaginal microbiome may be involved in the modulation of the local immune response in cervical mucosa [49]. The cytokine production could be modulated by HPV, impairing the immune response [3]. Therefore, we also evaluated the expression levels of the TLRs and immune cytokines that play a key role in innate immune response. The expressin of TLR3, TLR4, IFN-α, and IFN-β were downregulated in women with persistent HPV infection (Fig. 1). The results are corroborated by the findings of a case–control study comparing cervical biopsies from healthy and carcinoma samples that reported a reduction in TLR3 expression [50]. Activation of TLR3 by double-stranded (ds)RNA induces the production of several antiviral proteins, which further to establish antiviral state against viruses [51,52]. As expected, the expression of antiviral IFN-α and IFN-β was significantly downregulated in samples from women with persistent HPV infection, since it is known that HPV reduces IFN-I production through E6/E7 protein [53,54]. TLR4 is expressed at the plasma membrane, which can be recognized by HIV envelope, and HPV capsid protein, as well as bacterial LPS [55,56]. The TLR4 expression data corroborate the theory that the innate immune response can be modulate by Lactobacilli by triggering TLR4 activation. We detected increased expression of TLR9, IL-6, and IL-8 in persistent HPV-infected mucosa, as reported previously (Fig. 1B) [57]. The results can be explained by the higher levels of TLR9 in women with persistent HPV infection, which suggests that TLR9 supports a sustained inflammatory response in persistent HPV infection [57]. The increase of TLR9 level in women with persistent positive HPV may be determined by different factors affecting the immune response to HPV [57]. The different results of TLR9 activation in the natural history of HPV infection may depend on the balance between the inhibitory intensity of HPV on TLR9 and the ability of subjects to drive appropriate TLR9 activation. If the immune response can not successfully eliminate HPV infection within a certain period of time, the overexpression of TLR9 (which cannot cause an antiviral response) in women with persistent infection will lead to unnecessary effects, such as persistent inflammation, thus increasing the risk of cancer progression [58,59].

A large number of retrospective studies have shown that the cervico-vaginal Lactobacillus microbiota plays a significant role in shaping the immune response responsible for HPV clearance [12,[23], [24], [25], [26]]. However, there have been no reports confirming the immunomodulatory effects of Lactobacillus microbiota isolated from cervico-vaginal samples of HPV clearance in women. We next examined the effects of L. reuteri LRV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. jannaschii LJV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 isolated from cervicovaginal samples from women in the HPV clearance group on the host epithelial immune response in ectocervical cells using Luminex assays (Fig. 2B). Overall, cytokine/chemokine expression was significantly increased after treatment with L. reuteri LRV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. jannaschii LJV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 compared with treatment with growth media alone (P < 0.05). These results suggest that L. reuteri LRV03, L. vaginalis LVV03, L. jannaschii LJV03, and L. gasseri LGV03 can modify the host cervical epithelial immune response. Moreover, L. gasseri LGV03 was the only species to significantly increase the cytokine IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-α greater than fivefold in Ect1/E6E7 and CaSki cells. L. gasseri LGV03 can produce butyric acid, which could restore normal levels of IRF3 in vitro and in vivo to reverse the course of otherwise lethal sepsis (Table 3) [33]. Therefore, it is speculated that L. gasseri LGV03 was the most represented bacterial species regulating immune homeostasis in the vaginal microbiome.

The safety of probiotic strains is also important, including antibiotic resistance genes and potential virulence factors. Currently, many probiotic products only list the name of bacteria, without related genetic background information and specific strain name, but the safety of probiotics is strain-specific [60,61]. Genomics studies on the safety and efficacy of probiotics are crucial for obtaining lactic acid bacteria that can be used to develop probiotics [62]. This method can fully reveal the genetic information of lactic acid bacteria, systematically explain the metabolic mechanisms and physiological functions of lactic acid bacteria, lay a foundation for the genetic evolution and systematic classification of lactic acid bacteria, and provide a basis for the screening of excellent bacterial species. In this study, the whole genome sequencing showed that the genome size of L. gasseri LGV03 strain is 1982,292 bp with a GC content of 34.85%. COG annotation data of L. gasseri LGV03 shown that the protein coding sequence mainly involves the basic physiological activities of the strain, such as translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (14.25%), carbohydrate transport and metabolism (10.82%), general function prediction only (7.62%), amino acid transport and metabolism (7.55%), transcription (6.94%), replication, recombination, and repair (6.40%), and cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (5.64%). Fortunately, the strain had no virulence genes and no antibiotic resistance genes were detected. It was safe for antibiotic resistance gene delivery and virulence gene.

Ectocervical epithelial cells act as immune sentinels, which play important roles in maintaining the local immune response in cervical mucosa [5]. They can induce mucosal immune responses to pathogens by expressing soluble factors, such as proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, to recruit and activate immune cells [63]. The expression of TLRs in ectocervical epithelial cells plays an important role on the induction of the local immune response in the cervical mucosa by sensing antigens derived from pathogens during their infection [64]. Several studies have examined TLR expression and their vital roles in the induction of host defense systems against infectious diseases [65]. IFNs, proinflammatory cytokines, and chemokines are produced by infected cells in order to induce the recruitment and activation of immune cells and establish an antiviral state for virus clearance. Among the antiviral factors produced by infected cells, IFN-α and IFN-β are key cytokine involved in the protection against virus infection, and therefore the improvement of this antiviral cytokine by cervical epithelial cells have been used as a biomarker in the searching of beneficial microbes able to protect against virus infection [66], [67], [68]. In addition to IFNs, appropriate balance of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-1β) and chemokines (IL-8 and MCP-1) is necessary to protect against invading pathogens and avoid uncontrolled inflammatory responses that can lead to tissue damage [69]. Therefore, we evaluated whether L. gasseri LGV03 induced the expression of IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and IL-1β in Ect1/E6E7 cells. The results shown that L. gasseri LGV03 stimulation increased the expression of IFN-α and IFN-β in response to poly (I:C) (Fig. 4). The results in this paper are in agreement with the results of others studies on Bifidobacterium infantis MCC12, Bifidobacterium breve MCC1274 [70], Lactobacillus casei MEP221106 [71], Lactobacillus delbrueckii TUA4408L [40] and L. casei Zhang [72]. We also found that L. gasseri LGV03 was able to reduce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-1β) and chemokine (IL-8) in Ect1/E6E7 cells stimulated with poly (I:C) (Fig. 4). TLR negative regulators play key roles in regulating the immune responses against pathogens. Among them, the protein A20 is capable to terminate TLR signaling that result in the inhibition of NF-κB activation and the expression of inflammatory factors [73]. Then, it is tempting to speculate that L. gasseri LGV03 may increased the expression of A20 in Ect1/E6E7 cells stimulated with poly (I:C), thereby inhibiting the expression of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β, which is worthy of further study. Kanmani and Kim [68] also reported that Lactobacillus plantarum DU1, Weissella cibaria DU1, and Lactobacillus sakei reduced levels of IL-6/8, MCP-1, and IL-1β in HCT116 human colon cancer cells stimulated with poly (I:C). Our results showed that L. gasseri LGV03 boosts IFN-α and IFN-β production to inhibit the inflammatory responses induced by poly (I:C). We believe that L. gasseri LGV03 keeps the innate system alert to potential pathogens and reduces the inflammatory effects during persistent pathogen infection.

It is important to clarify the role of L. gasseri LGV03 during viral infection. During viral infection, host cell TLRs could activate IFN regulatory factors to regulate the production of IFN-α/β [74]. In the present study, as expected, challenging Ect1/E6E7 cells with L. gasseri LGV03 increased IRF3phosphorylation in response to TLR3 agonist (Fig. 5). The virus is also recognized by RIG-I and/or MDA-5, which in turn activate the NF-κB pathway, increasing the production of inflammatory cytokines in vivo and in vitro [75]. We found that L. gasseri LGV03 downregulated p-IκB-α (Fig. 5). Our data indicate that L. gasseri LGV03 enhanced the poly (I:C)-induced viral response by modulating the IRF3 pathway and attenuate the poly (I:C)-induced inflammatory response by regulating NF-κB pathway (Fig. 8). Similar results were obtained by Kitazawa et al. [40], who reported that L. delbrueckii TUA4408L enhanced the poly (I:C)-modulated IRF3 pathway and attenuated the poly (I:C)-mediated NF-κB activation in porcine intestinal epithelial cells.

Fig. 8.

Proposed mechanism involved in the antiviral activity of L. gasseri LGV03 in vitro. The possible immunomodulatory activity of L. gasseri LGV03 in Ect1/E6E7 cells after stimulation with poly (I:C). Arrows indicate up and down-regulation of cytokines/chemokines, and anti-viral factors. (+): upregulation, (-): down-regulation.

The zebrafish has been widely used in the study of human disease and development, and about 70% of the protein-coding genes are conserved between the two species [76]. In general, the zebrafish immune system has proven to be remarkably similar to that of humans [77]. Finally, an experimental zebrafish xenografts model was used to further verify the immunomodulatory activity of L. gasseri LGV03 in vivo. Our data indicated that L. gasseri LGV03 can effectively blocked the proliferation of Ect1/E6E7 cells in zebrafish xenografts (Fig. 6). L. gasseri LGV03 did not significantly affect the growth of Ect1/E6E7 cells in vitro (Fig. 2A). These findings suggest that L. gasseri LGV03 effectively inhibited the proliferation of Ect1/E6E7 cells in zebrafish xenografts, which may be due to L. gasseri LGV03 increasing the immune response in zebrafish. Moreover, L. gasseri LGV03 did not induce an inflammatory response in vivo, indicating that L. gasseri LGV03 may be used as antiviral substitutes for human and animal applications.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that in vitro exposure of L. gasseri LGV03 isolated from cervicovaginal samples of HPV clearance in women beneficially modulates the innate antiviral immune response induced by poly (I:C) in Ect1/E6E7 cells. L. gasseri LGV03 significantly upregulated mRNA levels of IFN-α and IFN-β, and downregulated IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β levels. L. gasseri LGV03 effectively inhibited the proliferation of Ect1/E6E7 cells in zebrafish xenografts by enhancing the immune response of zebrafish, but did not induce inflammatory response in vivo, indicating that L. gasseri LGV03 has the potential to improve the local immune response in cervical mucosa.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Qiong Gao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Tao Fan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Siying Luo: Data curation, Methodology. Jieting Zheng: Data curation, Methodology. Lin Zhang: Data curation, Methodology. Longbing Cao: Data curation, Methodology. Zikang Zhang: Validation, Methodology. Li Li: . Zhu Huang: Validation, Investigation. Huifen Zhang: Validation, Methodology. Liuxuan Huang: Validation, Investigation. Qing Xiao: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Feng Qiu: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest to this work. We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interest that represents a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant NO. 2023A1515011439),Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant NO. 2021A1515220025),Basic Research Project of Shenzhen Basic Research Special Project (Natural Science Foundation) (Grant NO. JCYJ20190808101001738), Public health scientific research project of Futian District, Shenzhen (Grant NO. FTWS2020001, Grant NO. FTWS2019002, Grant NO. FTWS2019035, Grant NO. FTWS2021038), Public health scientific research project of Guangming District (Grant NO. 2020R01044, Grant NO. 2021R01054).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101714.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Carrero Y.N., Callejas D.E., Mosquerac J.A. In situ immunopathological events in human cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer: review. Transl. Oncol. 2021;14(5) doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffman M., Castle P.E., Jeronimo J., Rodriguez A.C., Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):890–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou C., Tuong Z.K., Frazer I.H. Papillomavirus immune evasion strategies target the infected cell and the local immune system. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:682. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X., Cheng Y., Li C. The role of TLRs in cervical cancer with HPV infection: a review. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017;2:17055. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley M.A. Epithelial cell responses to infection with human papillomavirus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25(2):215–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05028-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan T., Barra N.G., Lee A.J., Ashkar A.A. Innate and adaptive immunity against herpes simplex virus type 2 in the genital mucosa. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011;88(2):210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nestle F.O., Di Meglio P., Qin J.Z., Nickoloff B.J. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9(10):679–691. doi: 10.1038/nri2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo Cigno I., Calati F., Albertini S., Gariglio M. Subversion of host innate immunity by human papillomavirus oncoproteins. Pathogens. 2020;9(4) doi: 10.3390/pathogens9040292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britto A.M.A., Goes L.R., Sivro A., Policarpo C., Meirelles A.R., Furtado Y., Almeida G., Arthos J., Cicala C., Soares M.A., Machado E.S., Giannini A.L.M. HPV induces changes in innate immune and adhesion molecule markers in cervical mucosa with potential impact on HIV infection. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:2078. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Insinga R.P., Perez G., Wheeler C.M., Koutsky L.A., Garland S.M., Leodolter S., Joura E.A., Ferris D.G., Steben M., Hernandez-Avila M., Brown D.R., Elbasha E., Munoz N., Paavonen J., Haupt R.M., Investigators F.I. Incident cervical HPV infections in young women: transition probabilities for CIN and infection clearance. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2011;20(2):287–296. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitra A., MacIntyre D.A., Marchesi J.R., Lee Y.S., Bennett P.R., Kyrgiou M. The vaginal microbiota, human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: what do we know and where are we going next? Microbiome. 2016;4(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dareng E.O., Ma B., Adebamowo S.N., Famooto A., Ravel J., Pharoah P.P., Adebamowo C.A. Vaginal microbiota diversity and paucity of Lactobacillus species are associated with persistent hrHPV infection in HIV negative but not in HIV positive women. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):19095. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76003-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillier S.L., Krohn M.A., Klebanoff S.J., Eschenbach D.A. The relationship of hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli to bacterial vaginosis and genital microflora in pregnant women. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;79(3):369–373. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong Z., Luna Y., Yu P., Fan H. Lactobacilli inactivate chlamydia trachomatis through lactic acid but not H2O2. PLoS One. 2014;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Hanlon D.E., Moench T.R., Cone R.A. In vaginal fluid, bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis can be suppressed with lactic acid but not hydrogen peroxide. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doerflinger S.Y., Throop A.L., Herbst-Kralovetz M.M. Bacteria in the vaginal microbiome alter the innate immune response and barrier properties of the human vaginal epithelia in a species-specific manner. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;209(12):1989–1999. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaiha G.D., Dong T., Palaniyar N., Mitchell D.A., Reid K.B., Clark H.W. Surfactant protein A binds to HIV and inhibits direct infection of CD4+ cells, but enhances dendritic cell-mediated viral transfer. J. Immunol. 2008;181(1):601–609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J.E., Lee S., Lee H., Song Y.M., Lee K., Han M.J., Sung J., Ko G. Association of the vaginal microbiota with human papillomavirus infection in a Korean twin cohort. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honda K., Littman D.R. The microbiome in infectious disease and inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:759–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Littman D.R., Pamer E.G. Role of the commensal microbiota in normal and pathogenic host immune responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10(4):311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ichinohe T., Pang I.K., Kumamoto Y., Peaper D.R., Ho J.H., Murray T.S., Iwasaki A. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108(13):5354–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019378108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abt M.C., Osborne L.C., Monticelli L.A., Doering T.A., Alenghat T., Sonnenberg G.F., Paley M.A., Antenus M., Williams K.L., Erikson J., Wherry E.J., Artis D. Commensal bacteria calibrate the activation threshold of innate antiviral immunity. Immunity. 2012;37(1):158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng J.J., Song J.H., Yu C.X., Wang F., Wang P.C., Meng J.W. Difference in vaginal microecology, local immunity and HPV infection among childbearing-age women with different degrees of cervical lesions in Inner Mongolia. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0806-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y., Wang L., Pei F., Ji M., Zhang F., Sun Y., Zhao Q., Hong Y., Wang X., Tian J., Wang Y. Patients with LR-HPV infection have a distinct vaginal microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019;9:294. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borgogna J.C., Shardell M.D., Santori E.K., Nelson T.M., Rath J.M., Glover E.D., Ravel J., Gravitt P., Yeoman C.J., Brotman R.M. Authors' reply re: the vaginal metabolome and microbiota of cervical HPV-positive and HPV-negative women: a cross-sectional analysis. BJOG. 2020;127(6):773–774. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawahara R., Fujii T., Kukimoto I., Nomura H., Kawasaki R., Nishio E., Ichikawa R., Tsukamoto T., Iwata A. Changes to the cervicovaginal microbiota and cervical cytokine profile following surgery for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):2156. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80176-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blaskewicz C.D., Pudney J., Anderson D.J. Structure and function of intercellular junctions in human cervical and vaginal mucosal epithelia. Biol. Reprod. 2011;85(1):97–104. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.090423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannella F., Scagnolari C., Selvaggi C., Stentella P., Recine N., Antonelli G., Pierangeli A. Interferon lambda 1 expression in cervical cells differs between low-risk and high-risk human papillomavirus-positive women. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014;203(3):177–184. doi: 10.1007/s00430-014-0330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haase A.T. Early events in sexual transmission of HIV and SIV and opportunities for interventions. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011;62:127–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-080709-124959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrahams V.M., Potter J.A., Bhat G., Peltier M.R., Saade G., Menon R. Bacterial modulation of human fetal membrane Toll-like receptor expression. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013;69(1):33–40. doi: 10.1111/aji.12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Black A.P., Ardern-Jones M.R., Kasprowicz V., Bowness P., Jones L., Bailey A.S., Ogg G.S. Human keratinocyte induction of rapid effector function in antigen-specific memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37(6):1485–1493. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Usyk M., Zolnik C.P., Castle P.E., Porras C., Herrero R., Gradissimo A., Gonzalez P., Safaeian M., Schiffman M., Burk R.D., Costa Rica H.P.V.V.T.G. Cervicovaginal microbiome and natural history of HPV in a longitudinal study. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim S.M., DeFazio J.R., Hyoju S.K., Sangani K., Keskey R., Krezalek M.A., Khodarev N.N., Sangwan N., Christley S., Harris K.G., Malik A., Zaborin A., Bouziat R., Ranoa D.R., Wiegerinck M., Ernest J.D., Shakhsheer B.A., Fleming I.D., Weichselbaum R.R., Antonopoulos D.A., Gilbert J.A., Barreiro L.B., Zaborina O., Jabri B., Alverdy J.C. Fecal microbiota transplant rescues mice from human pathogen mediated sepsis by restoring systemic immunity. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):2354. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15545-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brotman R.M., Klebanoff M.A., Nansel T.R., Yu K.F., Andrews W.W., Zhang J., Schwebke J.R. Bacterial vaginosis assessed by gram stain and diminished colonization resistance to incident gonococcal, chlamydial, and trichomonal genital infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;202(12):1907–1915. doi: 10.1086/657320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bingsen S., Longbin C., Jieting Z., Lin Z., Zikang Z., Feng Q. Isolation, identification and safety evaluation of Lactobacillus gasseri isolated from the vagina of healthy women. J. South. Med. Univ. 2021;41(12):1809–1815. doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2021.12.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maragkoudakis P.A., Zoumpopoulou G., Miaris C., Kalantzopoulos G., Pot B., Tsakalidou E. Probiotic potential of Lactobacillus strains isolated from dairy products. Int. Dairy J. 2006;16(3):189–199. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gopal P.K., Prasad J., Smart J., Gill H.S. In vitro adherence properties of Lactobacillus rhamnosus DR20 and Bifidobacterium lactis DR10 strains and their antagonistic activity against an enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001;67(3):207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(01)00440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner R.D., Johnson S.J. Probiotic bacteria prevent Salmonella - induced suppression of lymphoproliferation in mice by an immunomodulatory mechanism. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-0990-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishizuka T., Kanmani P., Kobayashi H., Miyazaki A., Soma J., Suda Y., Aso H., Nochi T., Iwabuchi N., Xiao J.Z., Saito T., Villena J., Kitazawa H. Immunobiotic bifidobacteria strains modulate rotavirus immune response in porcine intestinal epitheliocytes via pattern recognition receptor signaling. PLoS One. 2016;11(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanmani P., Albarracin L., Kobayashi H., Hebert E.M., Saavedra L., Komatsu R., Gatica B., Miyazaki A., Ikeda-Ohtsubo W., Suda Y., Aso H., Egusa S., Mishima T., Salas-Burgos A., Takahashi H., Villena J., Kitazawa H. Genomic characterization of lactobacillus delbrueckii TUA4408L and evaluation of the antiviral activities of its extracellular polysaccharides in porcine intestinal epithelial cells. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2178. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Indo Y., Kitahara S., Tomokiyo M., Araki S., Islam M.A., Zhou B., Albarracin L., Miyazaki A., Ikeda-Ohtsubo W., Nochi T., Takenouchi T., Uenishi H., Aso H., Takahashi H., Kurata S., Villena J., Kitazawa H. Ligilactobacillus salivarius strains isolated from the porcine gut modulate innate immune responses in epithelial cells and improve protection against intestinal viral-bacterial superinfection. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.652923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tripathi P., Tripathi P., Kashyap L., Singh V. The role of nitric oxide in inflammatory reactions. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2007;51(3):443–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mills E.L., O'Neill L.A. Reprogramming mitochondrial metabolism in macrophages as an anti-inflammatory signal. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016;46(1):13–21. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ilhan Z.E., Łaniewski P., Thomas N., Roe D.J., Chase D.M., Herbst-Kralovetz M.M. Deciphering the complex interplay between microbiota, HPV, inflammation and cancer through cervicovaginal metabolic profiling. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Paola M., Sani C., Clemente A.M., Iossa A., Perissi E., Castronovo G., Tanturli M., Rivero D., Cozzolino F., Cavalieri D., Carozzi F., De Filippo C., Torcia M.G. Characterization of cervico-vaginal microbiota in women developing persistent high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):10200. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09842-6. -10200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanodia S., Fahey L.M., Kast W.M. Mechanisms used by human papillomaviruses to escape the host immune response. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7(1):79–89. doi: 10.2174/156800907780006869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y., Yu T., Yan H., Li D., Yu T., Yuan T., Rahaman A., Ali S., Abbas F., Dian Z., Wu X., Baloch Z. Vaginal microbiota and HPV infection: novel mechanistic insights and therapeutic strategies. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020;13:1213–1220. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S210615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harper A., Vijayakumar V., Ouwehand A.C., Ter Haar J., Obis D., Espadaler J., Binda S., Desiraju S., Day R. Viral infections, the microbiome, and probiotics. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.596166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moscicki A.B., Shi B., Huang H., Barnard E., Li H. Cervical-vaginal microbiome and associated cytokine profiles in a prospective study of HPV 16 acquisition, persistence, and clearance. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.569022. -569022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aggarwal R., Misra S., Guleria C., Suri V., Mangat N., Sharma M., Nijhawan R., Minz R. Characterization of toll-like receptor transcriptome in squamous cell carcinoma of cervix: a case–control study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015;138(2):358–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]