Abstract

Introduction:

High output, persistent ascites (PA) is a common complication following liver transplant (LT). Recent work has identified that platelets help maintain endothelial integrity and can decrease leakage in pathological states. We sought to assess the association of PA following LT with platelet count and platelet function.

Methods:

Clot strength (MA) is a measure of platelet function and was quantified using thrombelastography (TEG). Total drain output following surgery was recorded in 24-h intervals during the same time frame as TEG. PA was considered >1 L on POD7, as that much output prohibits drain removal.

Results:

105 LT recipients with moderate or high volume preoperative ascites were prospectively enrolled. PA occurred in 28%. Platelet transfusions before and after surgery were associated with PA, in addition to POD5 TEG MA and POD5 MELD score. Patients with PA had a longer hospital length of stay and an increased rate of intraabdominal infections.

Conclusion:

Persistent ascites following liver transplant is relatively common and associated with platelet transfusions, low clot strength, and graft dysfunction.

Keywords: Persistent ascites, Liver transplantation, Platelets, Postoperative complications, Thrombelastography

1. Introduction

The most common cause of ascites in end stage liver disease is portal hypertension.1 This is further complicated by damaged endothelium and altered structures of intra-abdominal blood vessels.2 Liver transplantation (LT) immediately corrects portal hypertension, but ascites can persist or develop in the postoperative state. Persistent ascites (PA) following liver transplant (LT) is associated with decreased survival and increased morbidity, retransplant rate, treatment costs, and length of hospital stay.3-6 Postoperative ascites is commonly treated with diuretics and salt restriction.7 Additional interventions for refractory ascites have included the use of splanchnic vasoconstrictors to reduce portal blood flow.8 However, targeted therapies to improve damaged endothelium have not previously been used.

Platelets have been demonstrated to play a role in repairing damaged endothelium and decreasing permeability in pathological states.9,10 This is accomplished by adhering to the extracellular matrix, becoming activated, and forming a platelet plug.11 Post-operative thrombocytopenia has been identified as an independent risk factor for high output ascites following liver resection5 and extremely low platelet counts in living related liver transplant recipients.12 Platelet function using viscoelastic testing has not previously been assessed in the context of PA and may provide insight into a potential therapeutic strategy to reduce ascites in the postoperative setting that fails conventional management. Given these associations, we hypothesize that PA following LT is associated with platelet dysfunction quantified by clot strength using viscoelastic testing in the postoperative setting.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient population

Liver transplant recipients were pre-operatively enrolled and consented in a Colorado Multi-Institutional Review Board approved study. Research blood samples were collected pre-operatively through postoperative day (POD) five. The study time frame was from October of 2017 to May 2022. All patients were transplanted at the University of Colorado Hospital, which averages over 100 liver transplants a year. Enrollment criteria were adults (>18 years) who underwent a deceased donor liver transplant. As we were interested in persistent ascites in the postoperative period, we only included patients with moderate to high volume preoperative ascites, classified as Childs Pugh 2 or greater. Patient demographics were recorded including age, sex, co-morbidities, and sodium model for end-stage liver disease (MELD-Na) calculated on day of surgery. Additional clinical laboratory measurements and output of surgical drains were recorded through postoperative day seven. Donor demographics were extracted from an electronic donor medical record. Serial laboratory measurements on these donors are routine prior to organ donation. The peak AST and ALT were identified while during the time frame the donor’s laboratory data was collected, in addition to the donors last INR, AST, ALT, Bilirubin, creatinine, and sodium prior to organ procurement. Transfusions of red blood cells (RBC), fresh frozen plasma (FFP), cryoprecipitate (Cryo), and platelets in the recipients were determined before baseline TEG (24 h preceding) and within 24 h of subsequent research coagulation assessment.

2.2. Blood samples and viscoelastic testing

Blood was collected and stored in a 3.5-mL tubes containing 3.2% citrate and immediately transferred for analysis via a trained professional research assistant. All viscoelastic assays were completed within 2 h of the blood draw. Blood samples were assayed with the TEG 5000 Hemostatic Analyzer (Haemonetics, Braintree, MA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations by a single research assistant with experience running more than 1000 assays. Citrated native (without activator) TEG outputs included the reaction time (R-time), angle, maximum amplitude (MA). Specifically, MA reflects clot strength and is affected mostly by platelet numbers and/or function. Additional conventional coagulation assays drawn as routine postoperative care were also included with the same times as research TEG assays: preoperatively and on POD1, 3 and 5.

2.3. Outcomes

Persistent postoperative ascites was defined as greater than 1 L of fluid at 7 days based on a definition previously used in a clinical trial.8 We also evaluated the associated clinically relevant secondary outcomes with PA including hospital length of stay, postoperative intra-abdominal infection, and graft loss.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Patients with PA were contrasted to patients with lower drain output. Continuous variables were expressed using median and interquartile ranges and compared using the Wilcoxon test. Categorical variables were expressed in frequency and percentage and compared with Chi-Squared or Fischer’s Exact tests as appropriate. Our a priori hypothesis was that TEG MA would be associated with PA, but due to potential for MA to be inclusive of other coagulation components beyond platelets13 we evaluated all conventional clinical coagulation assays drawn as standard of care on the same days that research TEG samples were collected. We performed two regression models to predict PA. One was with preoperative variables, and the other was with variables on postoperative day 5, when last research viscoelastic testing was available. Clinical variables univariately associated with high drain output were included in a logistic regression model to control for multiple significant confounders. The model discrimination performance was assessed with c-statistics. The Youden Index was used to identify the best cutoff of a continuous variable. All tests were two-tailed with significance declared at P < 0.05. All analyses were conducted in SAS vs 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

During the study period, 287 LT recipients were enrolled and 105 LT recipients met inclusion criteria based on moderate or high preoperative ascites and receiving a cadaveric organ. The median age was 53 years, 37% were female, and the median MELD was 24. 86% of the recipients received their liver from a brain dead donor, as compared to a DCD donor. In the study, 28% of recipients had PA.

3.2. TEG MA and other coagulation variables associated with PA

Baseline coagulation variables were not associated with PA, but patients with PA had higher rates of preoperative transfusions (Table 1). On POD1 platelet transfusions remained higher in PA patients, but other transfusions became non-significant. POD3 INR became significantly higher in the PA group, and platelet transfusions were also more common in this group. By POD5, both INR and MA were significantly associated with PA, but no other transfusions associations were appreciated. The trends in MA and platelet transfusions are demonstrated in Fig. 2A and B, in which after platelet transfusions stop MA becomes significantly different between cohorts.

Table 1.

Coagulation variables over time and transfusions.

| Baseline |

POD1 |

POD3 |

POD5 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No PA | PA | p- value |

No PA | PA | p-value | No PA | PA | p-value | No PA | PA | p-value | |

| Hct | 29 (26-34 | 28 (25–32) | 0.267 | 29 (27–33) | 29 (27–32) | 0.764 | 30 (27–33) | 29 (27–32) | 0.417 | 31 (27–34) | 30 (27–33) | 0.443 |

| Tx RBC | 22% | 35% | 0.177 | 56% | 69% | 0.247 | 12% | 21% | 0.227 | 11% | 14% | 0.655 |

| Plt Ct | 65 (44–93) | 59 (38–85) | 0.292 | 48 (38–59) | 51 (39–69) | 0.552 | 41 (29–48) | 36 (24–42) | 0.056 | 42 (31–58) | 35 (28–45) | 0.085 |

| TEG MA | 42 (35–54) | 40 (34–47) | 0.271 | 46 (41–54) | 47 (43–50) | 0.817 | 42 (36–49) | 42 (31–47) | 0.396 | 45 (40–53) | 39 (34–51) | 0.008a |

| Tx Plt | 1% | 28% | <0.001a | 37% | 62% | 0.020a | 5% | 24% | 0.005a | 4% | 14% | 0.074 |

| Inr | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 2.3 (1.7–2.6) | 0.060 | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 1.6 (1.4–1.6) | 0.109 | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) | <0.001a | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | <0.001a |

| TEG R | 0.722 | 0.050 | 0.427 | 0.531 | ||||||||

| TX FFP | 19% | 38% | 0.043a | 26% | 45% | 0.068 | 1% | 3% | 0.481 | 0% | 0% | 0.999 |

| TEG Angle | 43 (34–56) | 40 (35–48) | 0.346 | 44 (39–54) | 38 (32–50) | 0.095 | 42 (34–50) | 41 (22–49) | 0.314 | 43 (34–52) | 41 (25–47) | 0.065 |

| TX Cryo | 5% | 24% | 0.006a | 18% | 35% | 0.080 | 3% | 3% | 0.831 | 2% | 0% | 0.375 |

Hct = hematocrit, Tx RBC = red blood cell transfusion, Plt Ct = platelet count, TEG MA = thrombelastography median amplitude, Tx Plt = platelet transfusion, TEG R = thrombelastography reaction time (min), Tx FFP = fresh frozen plasma transfusion, TEG Angle = thrombelastography (degrees), Tx Cryo = cryoprecipitate transfusion, data represented as the median and 25th-75th percentile range or percentage.

= P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Clot strength over time in patients with and without PA and rates of platelet transfusions.

Preop = preoperative, POD = postoperative day, PA = persistent ascites, MA = maximum amplitude.

Panel A represents the patients MA dichotomized based on PA status during the perioperative period. The MA was comparable between groups until POD5. Panel B: represents the percent of patients getting transfused with platelets during the same time frame, in which patients with PA had a higher rate of receiving platelets until POD5.

3.3. Preoperative regression model for predicting PA

Preoperative characteristics of PA groups are shown in Table 2. Overall, PA patients were more likely to have higher MELD-Na scores and receive a platelet transfusion (Table 1). The donor of recipients with PA were more likely to have higher peak aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lower prothrombin international normalized ratio (PT/INR), and elevated creatinine (Table 2). In the multivariable regression analysis only preoperative platelet transfusion was associated with PA, which had a odds ratio of 24.5 (p = 0.006 Table 3).

Table 2.

Preoperative variables associated with PA.

| Persistent High Output Ascites | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 76, 72%) | Yes (n = 29, 28%) | ||

| Age | 54 (43–62) | 50 (44–61) | 0.649 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 42% | 24% | 0.088 |

| Pre-Operative Serum Labs | |||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.05 (0.79–1.38) | 1.09 (0.91–1.72) | 0.277 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 3.4 (3.0–3.7) | 3.5 (3.1–3.8) | 0.766 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 136 (133–138) | 135 (133–138) | 0.461 |

| MELD-Na | 21.53 (17.43–28.94) | 24.86 (22.33–30.53) | 0.024* |

| Donor Characteristics | |||

| Donor Age | 38 (28–47) | 36 (26–45) | 0.733 |

| Donor BMI | 25 (22–29) | 25 (22–30) | 0.903 |

| DCD Donor | 18% | 14% | 0.574 |

| Peak AST | 123 (47–507) | 275 (133–1022) | 0.027* |

| INR | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 0.043* |

| Creatinine | 0.90 (0.63–1.32) | 1.04 (0.89–1.71) | 0.044* |

| Operative Time (min) | 497 (417–533) | 445 (409–508) | 0.113 |

MELD-Na = sodium model for end-stage liver disease, BMI = body mass index, AST = aspartate aminotransferase, DCD = donation after cardiac death, INR = international normalized ratio, Data are given as % or median and 25th-75th percentile.

P-value < 0.05.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression for PA Preoperative Variables.

| PA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | P-Value | ||

| Platelet Transfusion | 24.5 | 2.5 | 244.0 | 0.006* |

| Donor AST | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.077 |

| Donor INR | 0.20 | 0.03 | 1.63 | 0.134 |

| Donor Creatinine | 0.93 | 0.67 | 1.29 | 0.668 |

| MELD-Na | 1.02 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 0.542 |

AST = aspartate aminotransferase, INR = international normalized ratio, MELD-Na = sodium model for end-stage liver disease

P-value < 0.05.

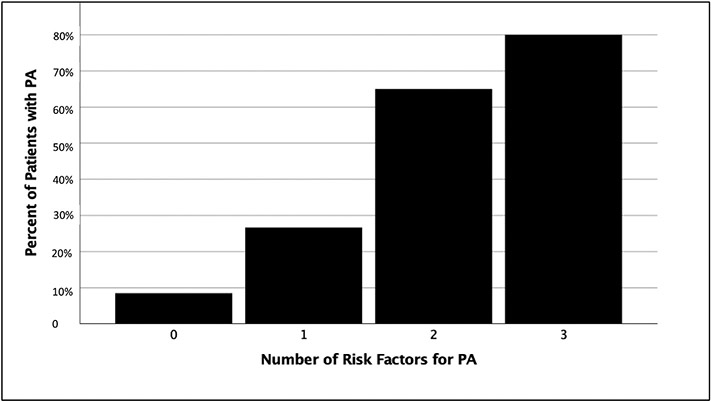

3.4. Postoperative regression model for predicting PA and outcomes

Variables associated with PA on POD5 included creatinine [2.2 (1.0–4.0) vs 1.1 (1.0–1.92) P = 0.005) and bilirubin [5.8 (2.5–10.1) vs 2.5 (1.4–5.1) p = 0.003]. Coagulation variables significantly associated with PA included MA (39 vs 45 P = 0.008) and INR (1.4 vs 1.2 P < 0.001) (Table 1). Albumin (p = 0.891) and transaminase levels (AST p = 0.434, ALT P = 0.489) were comparable between cohorts. Creatinine, bilirubin, and INR are all part of the MELD score, and when combining these variables, POD5 MELD score and MA remained significant predictors of PA (Table 4). Our ROC curve identified that an MA less than 40 mm and MELD greater than 17 on POD5 were inflection points for increased risk of PA. When combining preoperative platelet transfusion (Table 3 significant preoperative predictor of PA) with these two postoperative risk factors, there is a step wise progression from 8% to 80% rate of PA if 0 or all 3 risk factors were present (Fig. 3). Patients with PA had significantly longer hospital days [17 (14–47) vs 10 (7–17) P < 0.001], higher rates of intraabdominal infection (10% vs 1% p = 0.011), and higher but non-significant rate of graft loss (17% vs 9% p = 0.247).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression for PA Postoperative Variables.

| PA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | P-Value | ||

| POD5 | MELD-Na | 1.09 | 1.04 1.16 | 0.001* |

| POD5 | TEG MA | 0.96 | 0.91 0.998 | 0.040* |

MELD-Na = sodium model for end-stage liver disease, TEG MA = thrombelastography median amplitude

P-value < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Composite risk factors for PA and associated rates.

PA = persistent ascites.

Fig. 3 represents the composite risk factors for PA (preoperative platelet transfusion, MELD> 17 POD5 and TEG MA<40 on POD5). With each incremental increase in risk factors there is continuous increase in rate of PA.

4. Discussion

In this study, 28% of our LT recipients had persistent high output ascites following surgery. Preoperative platelet transfusion was the only significant predictor of PA after multivariable regression analysis with preoperative risk factors, despite several donor laboratory factors emerging in the univariate analysis. Patients with PA had a higher frequency of platelet transfusions in the first three days after surgery. On POD5 graft function as quantified by MELD in addition to TEG MA were significant predictors of PA. The combination of preoperative and postoperative variables associated with PA demonstrated a step wise progression in risk. PA was associated with almost double the hospital length of stay and a ten-fold rate of postoperative intraabdominal infection.

In cadaveric donors, renal dysfunction, and portal vein thrombosis have been associated with PA.4 Consistent with all these studies, we identified that increased creatinine on POD5 was associated with PA. We did not have postoperative portal vein thrombosis in this cohort, so we were unable to determine if this was a risk factor. Early allograft dysfunction in LT has been associated with increased vascular resistance in the portal vein and hepatic artery14 and in theory would be a risk factor for PA. We identify that and elevated POD5 MELD score was associated with PA. Potentially these grafts with evidence of dysfunction in the early postoperative period could have additional intravascular resistance contributing to PA. Low platelet count following LT have also been associated with PA in living donors.12 Thrombocytopenia has been associated adverse outcomes in LT for decades15 and repeatedly demonstrated to have an association with morbidity and graft loss in more contemporary studies,16,17 but these studies failed to report specific complications attributed to ascites. While platelet counts did not reach statistical significance in our study, the PA cohort had lower counts, and these patients were more frequently receiving a platelet transfusion in the pre and postoperative period. Our study represents the first functional coagulation assay identifying decreasing clot strength after surgery as a risk factor for early PA. An elevated INR on POD3 and POD5 also emerged as a risk factor for PA in our study. Work outside of transplant has demonstrated that the plasma in which platelets circulate can alter their activity,18 which could explain why a lower MA was significant rather than platelet counts between groups.

Intrahepatic and extrahepatic endothelial damage that occurs during liver transplantation19 remains a poorly understood process. Prior to transplant, epithelial cells are most vulnerable to damage in patients with cirrhosis.5,20 Systemic and splanchnic endothelial damage may even worsen following LT due to increased blood flow velocity resulting in endothelial cell swelling, endothelial desquamation, and loss of endothelial cell fenestration.21 Preexisting epithelial disorders exacerbated by transplant would be a set up for PA in liver transplant, despite resolution of portal hypertension. Our data may have identified that a specific cohort of patients have preexisting endothelial dysfunction prior to transplantation. Specifically, this cohort of patients had higher MELD-Na scores suggesting more advanced liver disease and was more likely to have a platelet transfusion prior to transplant. Disease states causing chronic inflammation, including cirrhosis, are known to cause leaky post capillary venules and manifest with a disseminated intravascular coagulation state.22 Pretransplant patients with end stage liver disease are more often thought of as having a lack of synthetic capacity,23 rather than having intravascular coagulation consumption. However, the spleen has been ascribed to be a culprit for consumption of platelets.24 It is unclear if these patients continue to have splenic consumption of platelets following transplant, or if a diffuse systemic process is occurring. PA patients in our study had persistently high rates of platelet transfusions through POD3 and demonstrated decreased clot strength by POD5 when transfusion rates decreased. Differentiating a pathologic consumptive process versus platelets repairing damaged endothelium would have an impact on patients’ management. There is emerging data that platelets can help repair living donor livers after transplant,25 which could have the potential to help improve the systemic endothelium supported by ex vivo endothelial research.26

Persistent ascites is a serious complication following transplant surgery. PA can last beyond 3 months following transplant and become a chronic problem.3,27 PA identified early on POD7 also portends to poor outcomes such as early graft loss in addition to increased hospital costs.5,28 We have appreciated the same complications associated with PA with increased hospital length of stay and increased risk of infection. Unfortunately, there are no interventions in treating PA beyond supportive measures and diuresis. Addressing endothelial damage as a therapeutic target for management of PA represents a potential new arena to explore. Given the crucial role platelets play in maintaining endothelial integrity, platelet transfusions have been successfully used as a therapeutic or prophylactic strategy for hemorrhage, a different type of leakage pathology than ascites.29 An alternative to increasing platelet counts, is to modify the circulating plasma to improve platelet function. The dual role of platelets and plasma in preserving endothelial integrity has been proposed26 and the effects of plasma in healthy versus injured individuals has been demonstrated to alter platelet function.18 Patients with PA had elevated INRs, that would not improve with a FFP transfusion (median INR 1.4), but the plasma has other properties that restore platelet function beyond coagulation factors. Recent work has identified specific proteins in plasma that help restore damaged endothelium.30

There are several limitations to our study. We cannot conclude that platelet dysfunction/decreased clot strength was the cause of PA. Multiple studies have attributed low platelet counts to graft dysfunction.12,17 It remains debated if attempts to correct platelet counts post transfusion would impact outcome.31 Our study demonstrates that livers with increased postoperative MELD scores on POD5 were associated with PA and supports that graft dysfunction following transplant has a role in PA. In addition, the fluid that came out of the drains post operatively was not evaluated for its contents, and could have components of chyle, which is another less frequently encountered source of fluid loss following liver transplant.32 Moreover, clot strength is not independent of other components of coagulation including fibrinogen.33 We found that INR was also elevated in patients with PA, and the clot strength could be reflective of multiple coagulation processes occurring. Ongoing work to evaluate platelet specific function with aggregometry would help delineate if platelet function was driving this process. In addition, given the risk of platelet transfusions with thrombosis or infectious complications in liver transplant,34 more mechanistic studies are needed before this hypothesis is put to the clinical test. Our study also used a 7-day cut off for assessing PA, while other studies evaluated patients weeks to months after transplant. There is also a potential that PA is unavoidable in a specific patient population. By identifying PA risk factors, it would at least begin to have a clinical impact on the planning of postoperative drain management and evaluate improvement measures to reduce intra-abdominal infections. This could be pre-defined times for drain removal and paracentesis postoperatively or initiation of prophylactic antibiotics if prolonged drain placement is anticipated.

In conclusion, our study has identified that platelet transfusions, graft dysfunction, and decreased clot strength on POD5 is associated with PA. Future work evaluating the role of endothelial dysfunction in driving PA represents a new arena of research in LT, that has a paucity of data but potential the help improve patient outcomes. However, our study is limited to observational data and a clear cause has not been established.

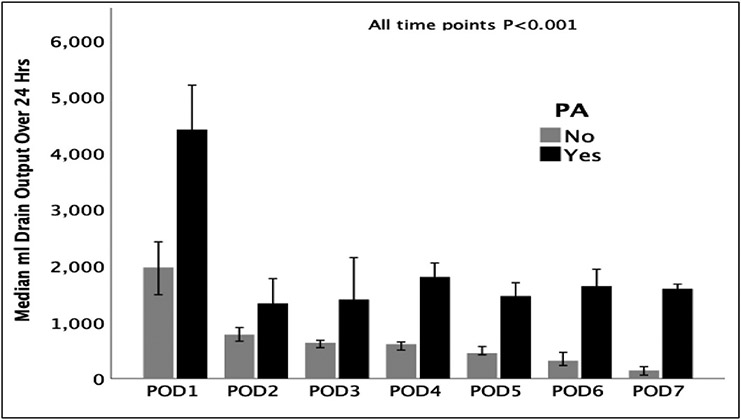

Fig. 1.

Post-liver transplant drain output over time between groups with and without PA.

POD = postoperative day, PA = persistent ascites.

Fig. 1 demonstrates the drain output between patients with and without PA for the first 7 postoperative days.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute: R00-HL151887 and American Society of Transplant Surgeons Veloxis Fellowship Award, and University of Colorado Academic Enrichment Fund

Footnotes

Presented at the Southwestern Surgical Congress, Wigwam, Arizona April 2022

References

- 1.Turco L, Garcia-Tsao G. Portal hypertension: pathogenesis and diagnosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23(4):573–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwakiri Y. Endothelial dysfunction in the regulation of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Liver Int. 2012;32(2):199–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirera I, Navasa M, Rimola A, et al. Ascites after liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2000;6(2):157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gotthardt DN, Weiss KH, Rathenberg V, et al. Persistent ascites after liver transplantation: etiology, treatment and impact on survival. Ann Transplant. 2013; 18:378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishizawa T, Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, et al. Risk factors and management of ascites after liver resection to treat hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2009;144(1):46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lan BY, Landry GM, Tan VO, et al. Ascites in hepatitis C liver transplant recipients frequently occurs in the absence of advanced fibrosis. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(2):366–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishida S, Gaynor JJ, Nakamura N, et al. Refractory ascites after liver transplantation: an analysis of 1058 liver transplant patients at a single center. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(1):140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee TY, Fan HL, Wang CW, et al. Somatostatin therapy in patients with massive ascites after liver transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2019;24:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gimbrone MA Jr, Aster RH, Cotran RS, et al. Preservation of vascular integrity in organs perfused in vitro with a platelet-rich medium. Nature. 1969;222(5188):33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitchens CS, Pendergast JF. Human thrombocytopenia is associated with structural abnormalities of the endothelium that are ameliorated by glucocorticosteroid administration. Blood. 1986;67(1):203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molica F, Stierlin FB, Fontana P, et al. Pannexin- and connexin-mediated intercellular communication in platelet function. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pamecha V, Mahansaria SS, Kumar S, et al. Association of thrombocytopenia with outcome following adult living donor liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2016;29(10):1126–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon C, Ranucci M, Hochleitner G, et al. Assessing the methodology for calculating platelet contribution to clot strength (platelet component) in thromboelastometry and thrombelastography. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(4):868–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harms J, Ringe B, Pichlmayr R. Postoperative liver allograft dysfunction: the use of quantitative duplex Doppler signal analysis in adult liver transplant patients. Bildgebung. 1995;62(2):124–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCaughan GW, Herkes R, Powers B, et al. Thrombocytopenia post liver transplantation. Correlations with pre-operative platelet count, blood transfusion requirements, allograft function and outcome. J Hepatol. 1992;16(1-2):16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lesurtel M, Raptis DA, Melloul E, et al. Low platelet counts after liver transplantation predict early posttransplant survival: the 60-5 criterion. Liver Transplant. 2014;20(2):147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akamatsu N, Sugawara Y, Kanako J, et al. Low platelet counts and prolonged prothrombin time early after operation predict the 90 Days morbidity and mortality in living-donor liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2017;265(1):166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fields AT, Matthay ZA, Nunez-Garcia B, et al. Good platelets gone bad: the effects of trauma patient plasma on healthy platelet aggregation. Shock. 2021;55(2):189–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiefer J, Lebherz-Eichinger D, Erdoes G, et al. Alterations of endothelial glycocalyx during orthotopic liver transplantation in patients with end-stage liver disease. Transplantation. 2015;99(10):2118–2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwakiri Y, Groszmann RJ. Vascular endothelial dysfunction in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2007;46(5):927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmes D, Budny TB, Dietl KH, et al. Detrimental effect of sinusoidal overperfusion after liver resection and partial liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2005;17(12):862–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oda M, Han JY, Nakamura M. Endothelial cell dysfunction in microvasculature: relevance to disease processes. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2000;23(2-4):199–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tripodi A. Liver disease and hemostatic (Dys)function. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015;41(5):462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scharf RE. Thrombocytopenia and hemostatic changes in acute and chronic liver disease: pathophysiology, clinical and laboratory features, and management. J Clin Med. 2021;10(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Yi NJ, Shin WY, et al. Platelet transfusion can be related to liver regeneration after living donor liver transplantation. World J Surg. 2010;34(5):1052–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barry M, Pati S. Targeting repair of the vascular endothelium and glycocalyx after traumatic injury with plasma and platelet resuscitation. Matrix Biol. 2022;14, 100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart CA, Wertheim J, Olthoff K, et al. Ascites after liver transplantation–a mystery. Liver Transplant. 2004;10(5):654–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shirouzu Y, Ohya Y, Suda H, et al. Massive ascites after living donor liver transplantation with a right lobe graft larger than 0.8% of the recipient’s body weight. Clin Transplant. 2010;24(4):520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humbrecht C, Kientz D, Gachet C. Platelet transfusion: current challenges. Transfus Clin Biol. 2018;25(3):151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng X, Cao Y, Huby MP, et al. Adiponectin in fresh frozen plasma contributes to restoration of vascular barrier function after hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2016;45(1):50–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi K, Nagai S, Safwan M, et al. Thrombocytopenia after liver transplantation: should we care? World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(13):1386–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukerji AN, Tseng E, Karachristos A, et al. Chylous ascites after liver transplant: case report and review of literature. Exp Clin Transplant. 2013;11(4):367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlimp CJ, Solomon C, Ranucci M, et al. The effectiveness of different functional fibrinogen polymerization assays in eliminating platelet contribution to clot strength in thromboelastometry. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(2):269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pereboom IT, Lisman T, Porte RJ. Platelets in liver transplantation: friend or foe? Liver Transplant. 2008;14(7):923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]