Abstract

This cohort study assesses the incidence of influenza-associated serious neuropsychiatric events among US children and adolescents.

Influenza is an important cause of acute respiratory illness in children. While influenza infections can manifest with neuropsychiatric symptoms,1 such symptoms could be attributed to antivirals or a combination of antivirals and influenza. The incidence of influenza-associated neuropsychiatric events in US children is unknown.2,3 We assessed the incidence of influenza-associated serious neuropsychiatric events in children and adolescents.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of individuals aged 5 to 17 years with an outpatient ICD-10 diagnosis of influenza identified during 4 influenza seasons (2016-2020) using the Tennessee Medicaid database. This study using deidentified claims data did not involve human participants; thus, it was exempt by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center institutional review board and informed consent was waived. This study followed the STROBE reporting guideline.

To reduce potential misclassification of influenza diagnoses, each season encompassed the 13 consecutive weeks that included the maximum number of laboratory-confirmed influenza cases in Tennessee laboratory-based surveillance systems.4,5 For each influenza episode, follow-up started on the diagnosis date and continued through the earliest of follow-up day 10, loss of enrollment, end of season, death, or the outcome: neuropsychiatric event resulting in hospitalization. Serious neuropsychiatric events were identified using an established algorithm with a positive predictive value of 90%6 that included neurologic and psychiatric events. The rate of serious neuropsychiatric events was calculated by dividing the number of events by the total influenza person-time (per 100 000 person-weeks of influenza). Rate was calculated overall and stratified by age, sex, underlying neurologic or psychiatric diagnosis, risk factors for influenza complications, antiviral use, influenza season, and clinical severity (eMethods in Supplement 1). Analyses were done using R, version 4.1.2.

Results

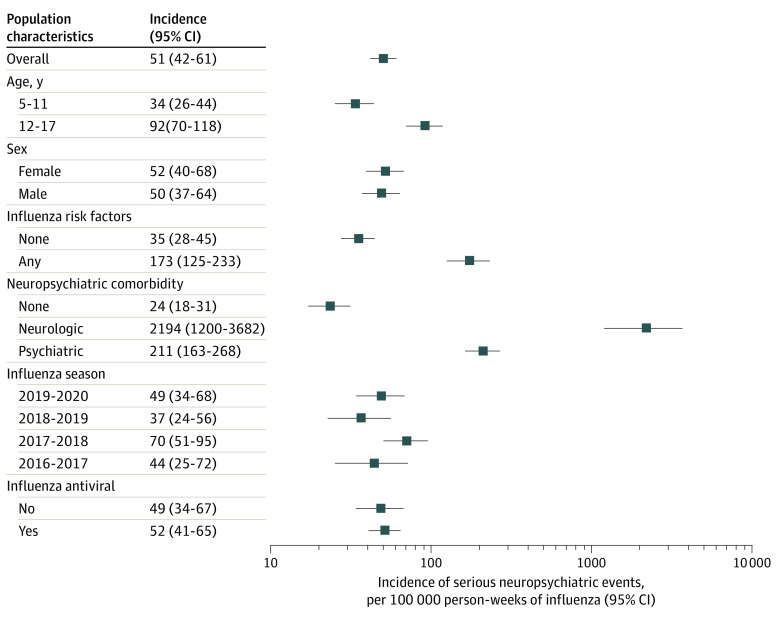

A total of 156 661 influenza diagnoses were included. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are given in the Table. The overall incidence rate was 51 (95% CI, 42-61) per 100 000 person-weeks of influenza. Incidence per 100 000 person-weeks of influenza by clinical severity categories was 0.9 (95% CI, 0.1-3.2) for critical, 40.8 (95% CI, 32.8-50.1) for important, and 9.0 (95% CI, 9.5-13.9) for unknown significance. Rates were higher among adolescents and in those with risk factors for influenza complications. Rates were markedly higher in those with neurologic and psychiatric disorders compared with those without. Rates by sex and season and for oseltamivir-exposed and -unexposed individuals were similar (Figure).

Table. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Populationa.

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 156 661) | Serious neuropsychiatric event | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without (n = 156 548) | With (n = 113) | ||

| Age | |||

| Median (IQR) | 9.32 (6.91-12.63) | 9.32 (6.91-12.63) | 12.36 (9.27-15.17) |

| 5-11 y | 110 675 (71) | 110 622 (71) | 53 (47) |

| 12-17 y | 45 986 (29) | 45 926 (29) | 60 (53) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 76 645 (49) | 76 588 (49) | 57 (50) |

| Male | 80 016 (51) | 79 960 (51) | 56 (50) |

| Race and ethnicityb | |||

| Black | 23 907 (15) | 23 893 (15) | 14 (12) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 248 (<1) | 248 (<1) | 0 |

| White | 96 890 (62) | 96 839 (62) | 51 (45) |

| Other or unknownc | 35 616 (23) | 35 568 (23) | 48 (43) |

| Neuropsychiatric comorbidity | |||

| Psychiatric | 22 005 (14) | 21 939 (14) | 66 (58) |

| Neurologic | 460 (<1) | 446 (<1) | 14 (12) |

| Any antiviral medicationd | 104 777 (67) | 104 700 (67) | 77 (68) |

| Any influenza risk factore | 17 546 (11) | 17 503 (11) | 43 (38) |

| Influenza season | |||

| 2016-2017 | 25 469 (16) | 25 453 (16) | 16 (14) |

| 2017-2018 | 40 927 (26) | 40 886 (26) | 41 (36) |

| 2018-2019 | 40 173 (26) | 40 152 (26) | 21 (19) |

| 2019-2020 | 50 092 (32) | 50 057 (32) | 35 (31) |

Data are presented as number (percentage) of the study population unless otherwise specified. Percentages may not add to 100% because of rounding.

Race and ethnicity were ascertained by self-report and are reported to describe the study population. Race and ethnicity were not used in data analysis.

Other race and ethnicity included American Indian, Asian, Cuban or Haitian, Southeast Asian, or other.

Oseltamivir constituted more than 99% of antiviral use.

As defined by the 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Figure. Incidence of Influenza-Associated Serious Neuropsychiatric Events.

Antiviral dispensing occurred 2 days before influenza diagnosis through 10 days after diagnosis. The predominant influenza viruses each season included influenza A(H3N2) in the 2016-2017 season, influenza A(H3N2) and influenza B in the 2017-2018 season, influenza A(H3N2) in the 2018-2019 season, and influenza A(H1N1pdm09) in the 2019-2020 season.5 Risk factors for influenza complications were defined based on the 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Neurologic events included seizures, encephalitis, ataxia or movement disorders, altered mental status (also includes encephalopathy, delirium, confusion, and paranoia), dizziness, headache, sleeping disorders, and vision changes. Psychiatric events included homicidal, suicidal, or self-harm behaviors; mood disorders; psychosis; hallucination; and mood disorders. Horizontal lines represent 95% CIs.

Discussion

In this study, the incidence of influenza-associated serious neuropsychiatric events in children and adolescents was low and varied with age and presence of risk factors for influenza complications and of neurologic or psychiatric comorbidities. Our estimates are lower than the 100 neuropsychiatric events per 100 000 influenza diagnoses reported in a Korean study focusing on ambulatory events.2 That study also found higher incidence among Korean children with preexisting neurologic disorders. Our rates are more similar to those reported by a recent Australian study focusing on severe neurologic complications of laboratory-confirmed influenza infections.3

Study strengths include use of a large database, highly specific and validated outcome measurement,6 and influenza season definition designed to minimize exposure misclassification.4 Limitations include the lack of information on vaccination status, virus type, and children younger than 5 years. Findings may not be directly applicable to populations other than individuals enrolled in Tennessee Medicaid. Incidence may be underestimated due to our inability to capture influenza-associated events without an influenza diagnosis. We did not characterize dose, duration, or exact timing of oseltamivir in relation to start of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Our rate estimates highlight the importance of vaccination and antiviral treatment for children and adolescents at high risk for serious influenza complications, especially those with psychiatric and neurologic conditions. Our findings do not support an association between oseltamivir and neuropsychiatric events, although we did not control for important potential confounders to fully explore potential associations. Additional study is needed to determine the extent to which vaccination or antiviral treatment may modify the risk of influenza-associated neuropsychiatric events.

eMethods

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Mizuguchi M. Influenza encephalopathy and related neuropsychiatric syndromes. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(Suppl 3)(suppl 3):67-71. doi: 10.1111/irv.12177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huh K, Kang M, Shin DH, Hong J, Jung J. Oseltamivir and the risk of neuropsychiatric events: a national, population-based study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(9):e409-e414. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnelley E, Teutsch S, Zurynski Y, et al. ; Contributors to the Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit . Severe influenza-associated neurological disease in Australian children: seasonal population-based surveillance 2008-2018. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2022;11(12):533-540. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piac069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, et al. ; New Vaccine Surveillance Network . The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):31-40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Weekly U.S. influenza surveillance report. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm

- 6.Antoon JW, Feinstein JA, Grijalva CG, et al. Identifying acute neuropsychiatric events in children and adolescents. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(5):e152-e160. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2021-006329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Data Sharing Statement