Key Points

Question

Is social isolation associated with hospitalization, skilled nursing facility stays, and nursing home placement among community-dwelling older adults over time?

Findings

In this nationally representative cohort study of 11 517 older adults, social isolation was significantly associated with higher odds of skilled nursing facility stays and nursing home placement during 2 years, but not with hospitalization.

Meaning

Findings from this study suggest that social isolation was associated with increased risk for nursing home entry among older US residents; efforts to reduce nursing home use and related spending should consider bolstering the social connections of older adults as an intervention.

This cohort study investigates the association of social isolation with hospitalization and nursing home entry among community-dwelling older adults.

Abstract

Importance

Social isolation is associated with adverse health outcomes, yet its implications for hospitalization and nursing home entry are not well understood.

Objective

To evaluate whether higher levels of social isolation are associated with overnight hospitalization, skilled nursing facility stays, and nursing home placement among a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling older adults after adjusting for key health and social characteristics, including loneliness and depressive symptoms.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This observational cohort study included 7 waves of longitudinal panel data from the Health and Retirement Study, with community-dwelling adults aged 65 years or older interviewed between March 1, 2006, and June 30, 2018 (11 517 respondents; 21 294 person-years). Data were analyzed from May 25, 2022, to May 4, 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Social isolation was measured with a multidomain 6-item scale (range, 0-6, in which a higher score indicates greater isolation). Multivariate logistic regressions were performed on survey-weighted data to produce national estimates for the odds of self-reported hospitalization, skilled nursing facility stays, and nursing home placement over time.

Results

A total of 57% of this study’s 11 517 participants were female, 43% were male, 8.4% were Black, 6.7% were Hispanic or Latino, 88.1% were White, 3.5% were other (“other” includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, and other race, which has no further breakdown available because this variable was obtained directly from the Health and Retirement Study), and 58.2% were aged 65 to 74 years. Approximately 15% of community-dwelling older adults in the US experienced social isolation. Higher social isolation scores were significantly associated with increased odds of nursing home placement (odds ratio, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.21-3.32) and skilled nursing facility stays (odds ratio, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.06-1.28) during 2 years. With each point increase in an individual’s social isolation score, the estimated probability of nursing home placement or a skilled nursing facility stay increased by 0.5 and 0.4 percentage points, respectively, during 2 years. Higher levels of social isolation were not associated with 2-year hospitalization rates.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study found that social isolation was a significant risk factor for nursing home use among older adults. Efforts to deter or delay nursing home entry should seek to enhance social contact at home or in community settings. The design and assessment of interventions that optimize the social connections of older adults have the potential to improve their health trajectories and outcomes.

Introduction

Nearly a quarter of community-dwelling older adults in the US experience social isolation,1,2 an objective lack of social contact that complicates the ability to age at home or in the community.1,3 Social isolation is of particular concern for older adults, who often experience bereavement or kinlessness or live alone despite needing additional support to manage complex health conditions.4,5 Social isolation is associated with functional limitations,6,7,8,9,10 declines in mental and cognitive health,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 diabetes and cardiovascular disease,11,23,24,25,26 and a 30% increase in mortality risk.1,27,28,29,30,31,32

Despite robust evidence regarding the associations between social isolation and poor health, few studies have examined its implications for costly forms of health care use.1,14,33 To our knowledge, no study has examined social isolation as a risk factor for nursing home placement in a nationally representative sample of older adults in the US. Furthermore, evidence regarding social isolation as a risk factor for hospitalization is inconclusive.1 One study linked social isolation to increased spending on acute and postacute care but was limited to Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.14 Another study found increased odds of hospitalizations and emergency department visits among Medicare Advantage enrollees but was restricted to older adults in the Northwest and used a single-item measure that combined perceived isolation and loneliness.34 Loneliness, a subjective feeling of being alone, is only moderately correlated with social isolation and is independently correlated with adverse health outcomes.1,4,13,15,28,34,35,36,37

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine consensus committee’s report on social isolation and loneliness has highlighted the need for studies that include both measures of social isolation and loneliness in the same sample to better determine the distinct effects of these factors on health.1 It is important to tease apart the effects of social isolation from loneliness because they reflect different objective and subjective mechanisms of social connection that have different implications for the design of social interventions. Furthermore, studies should consider the effects of social isolation and loneliness alongside correlated psychological states, such as depression.27 More robust evidence using multivariable modeling is needed to clarify the association between social isolation and costly forms of health care use.

Social isolation may be strongly associated with hospitalization and nursing home entry given that these services may signal worse health, a lack of adequate social supports needed for recovery or functioning at home, or both. If so, the objective nature of social isolation may lend itself well to policies and interventions that increase social contact to curb avoidable Medicare and Medicaid spending. Such strategies may also cater to older adults who prefer to receive care or age at home as opposed to facility-based settings. Given growing interest and concerns regarding social isolation in the COVID-19 era,38 there is an urgent need to examine the association between social isolation and the health care trajectories of older adults.

To address this gap, this study used 7 waves of longitudinal panel data from a nationally representative sample of older adults to test for associations between social isolation and hospital and nursing home use over time. We hypothesized that the higher levels of chronic illness associated with social isolation would result in a higher hospitalization rate. Because social isolation entails limited social contact or support at home or in the community, we also hypothesized that older adults with higher levels of social isolation would be more likely to rely on institutional settings, resulting in higher use of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and nursing home placement. By accounting for loneliness and depressive symptoms in analyses, this study further facilitates a comprehensive assessment of how various aspects of social connection and psychosocial health affect hospital and nursing home use.13

Methods

Data and Participants

This cohort study used Health and Retirement Study (HRS) panel data from March 1, 2006, to June 30, 2018. The HRS is a nationally representative, longitudinal survey that captures trends associated with health, employment, and assets among 20 000 older US residents biennially.39 Data were analyzed from May 25, 2022, to May 4, 2023. Response rates from the 2006 wave onward surpass 87%.40 The RAND Corporation cleans and appends repeated measures for participants after each round (ie, every 2 years), compiling a single longitudinal file that includes many of the core HRS questions.41 In 2006, the HRS began using a self-administered Psychosocial and Lifestyle Questionnaire (SAQ) with an alternating 50% of the larger HRS cohort each round.42 Sample A received the SAQ in 2006, 2010, and 2014, whereas sample B received the SAQ in 2008, 2012, and 2016. Response rates to the SAQ range from 73% to 88%.42 This study merged the core HRS files with the RAND longitudinal file and SAQ questionnaires, stacking data from sample A on sample B to construct 3 time points with repeated measures for the same individuals across time (eFigure in Supplement 1). Hospitalization, SNF stays, and nursing home placement were measured in 2-year increments after each time point. For example, participants in sample A had social isolation and covariates measured in 2014 and were asked during a 2016 follow-up interview whether each of the outcomes had occurred during the past 2 years (since the prior 2014 interview). As such, we harnessed the longitudinal study design by using baseline reports of social isolation and covariates at an index interview combined with hospital and nursing home use reported 2 years later. Respondents were eligible for inclusion regardless of insurance type, granted they were at least aged 65 years and community dwelling at their index SAQ interview.

Social Isolation

This study examined social isolation as the key explanatory variable of interest. We conceptualized social isolation among community-dwelling older adults as an objective lack of social contact at home and in the community. To operationalize this concept, we used a previously described 6-item measure of objective social isolation that was adapted from prior work conducted in the HRS29,43,44 and the English Longitudinal Study of Aging, an HRS sister study.7,13,32,45,46 The social isolation scale included 6 components that capture aspects of social contact, network interactions, and community engagement,13,43 including (1) marital status, (2) living arrangement, (3) frequency of contact with children, (4) frequency of contact with family, (5) frequency of contact with friends, and (6) social participation in groups, clubs, social organizations, or religious services (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Items were summed to create a continuous score that could range from 0 to 6, in which a higher score indicates greater isolation. Scores that fell into the top quintile (scores ≥3 in this study) were used as a threshold to highlight key differences in the descriptive characteristics of subgroups of older adults with low vs high social isolation scores (Table 1).29,32 However, continuous scores were used in the remainder of analyses, reflecting the gradient nature of social connection and need for research that examines social isolation on a continuum.47

Table 1. Descriptive Characteristics for Older Adults Overall and by Level of Social Isolation, 2006-2018a.

| Measure | All respondents, weighted % (unweighted No.) | Weighted % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socially isolated (n = 3127)b | Not socially isolated (n = 18 369) | ||

| Outcome variables | |||

| Overnight hospitalization | 30.54 (6671) | 31.88 | 30.28 |

| Skilled nursing facility visitsc | 3.82 (817) | 5.31 | 3.54 |

| Nursing home placementc | 1.94 (407) | 3.98 | 1.56 |

| Lonelinessc | 23.52 (4975) | 38.00 | 20.81 |

| Depressionc | 11.82 (2478) | 20.44 | 10.21 |

| Time point | |||

| First (2008-2010) | 30.08 (7903) | 29.26 | 30.24 |

| Second (2012-2014) | 33.55 (7247) | 35.12 | 33.26 |

| Third (2016-2018) | 36.36 (6346) | 35.61 | 36.50 |

| Female sexc | 57.24 (12 712) | 62.59 | 56.23 |

| Age, yc | |||

| 65-74 | 58.18 (11 590) | 50.90 | 59.54 |

| 75-84 | 31.15 (7768) | 32.20 | 30.96 |

| 85-94 | 10.17 (2055) | 15.74 | 9.13 |

| ≥95 | 0.49 (83) | 1.16 | 0.37 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Black | 8.41 (2605) | 8.29 | 8.43 |

| Hispanic | 6.74 (1571) | 6.84 | 6.72 |

| White | 88.08 (18 169) | 87.17 | 88.25 |

| Otherd | 3.51 (722) | 4.54 | 3.32 |

| Medicaidc | 6.92 (1536) | 12.68 | 5.84 |

| Current smokingc | 8.36 (1756) | 14.38 | 7.23 |

| Not physically activec | 45.17 (9861) | 54.29 | 43.46 |

| ADL difficulty score, mean (SD)c,e | 0.18 (0.60) | 0.29 (0.73) | 0.16 (0.57) |

| IADL difficulty score, mean (SD)c,e | 0.11 (0.48) | 0.18 (0.56) | 0.10 (0.46) |

| No. of chronic illnesses, mean (SD)c,e | 2.29 (1.48) | 2.43 (1.45) | 2.27 (1.49) |

| ADRDf | 2.65 (561) | 3.75 | 2.44 |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; ADRD, Alzheimer disease and related dementias; IADL, instrumental ADL.

Estimates represent weighted percentages unless indicated otherwise. Weighted 210 813 081 person-years; unweighted 21 496 person-years. Missing observations include 85 for hospitalization and 135 for skilled nursing facility stays.

Respondents with a social isolation score of 3 or higher were characterized as socially isolated for the purposes of this table.

Difference between older adults who were socially isolated and not socially isolated was significant at P ≤ .001.

Includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, and other race, which has no further breakdown available because this variable was obtained directly from the Health and Retirement Study.

Values listed for continuous scores or count variables indicate weighted means and SDs.

Difference between older adults who were socially isolated and not socially isolated was significant at P = .002.

Health Care Use Outcomes

At each wave, participants self-reported whether they had an overnight hospital stay or nursing home stay since the previous interview (ie, past 2 years). Hospitalization was dichotomized as yes or no. Respondents were counted as having an SNF stay if they reported having an overnight stay in a nursing home but were not living in the nursing home at the follow-up interview. Respondents living in a nursing home at the 2-year follow up interview were counted as long-term nursing home residents.45 Respondents already living in a nursing home at their initial SAQ interview were excluded from analyses.

Covariates

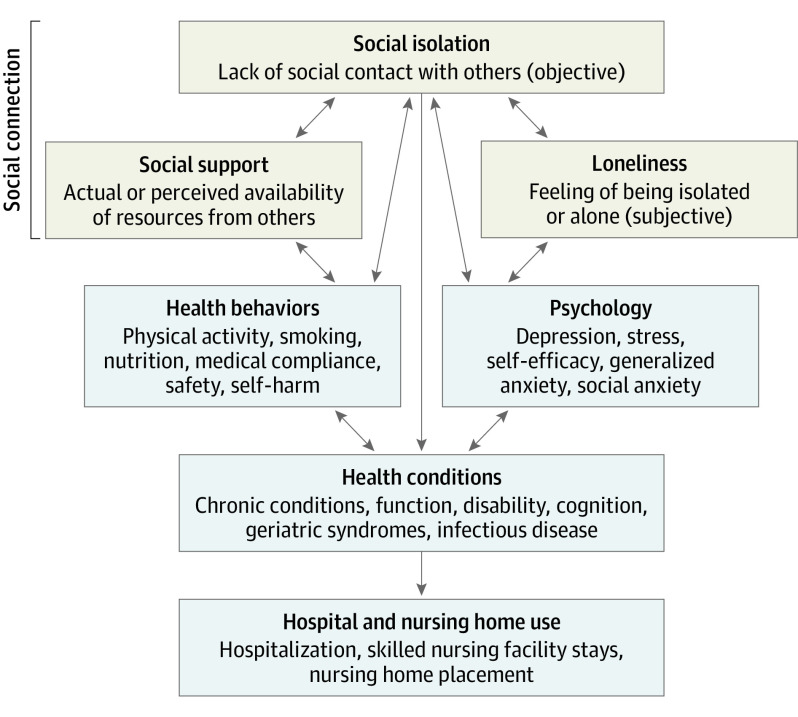

Covariates were chosen a priori and grounded in our conceptual framework, which was informed by past research examining the pathways between social isolation and health outcomes (Figure).3,23,48,49 We accounted for loneliness and depressive symptoms, sociodemographics, health behaviors, health conditions, and time.

Figure. Conceptual Framework Modeling Indirect and Direct Pathways Between Social Isolation and Hospital and Nursing Home Use.

Reflecting prior work,37,43,50,51 social isolation was not highly correlated with loneliness (r = 0.25) or depressive symptoms (r = 0.18), which were included as separate psychosocial covariates. Loneliness was measured with the 3-item UCLA Loneliness Scale,52,53,54 which includes questions on the frequency with which respondents believe they are lacking companionship, left out, and isolated from others. Scores with item-level missingness were imputed with the mean of the available items if respondents answered at least 2 of the 3 items (2.3%).29 Higher scores correspond to more severe loneliness, with final scores ranging from 3 to 9. Continuous scores were used in analyses, although scores between 6 and 9 indicate loneliness.32 Depressive symptoms were measured with the revised 8-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.55,56 The HRS calculates scores for respondents who answer at least 3 of the 9 question components. Final scores range from 0 to 8, in which higher scores correspond to worse depressive symptoms. Scores greater than or equal to 4 are considered to be indicative of clinically relevant depressive symptomology.55,57,58,59

We characterized age, sex, racial and ethnic identity, Medicaid enrollment, smoking status, and physical activity. We included a count of 7 chronic illnesses (self-report of physician-diagnosed hypertension, diabetes, cancer, lung disease, heart disease, stroke, or arthritis). Separately, we included an indicator for participants who reported that they had received a physician diagnosis of Alzheimer disease or a related dementia. We adjusted for functional limitations by using two 3-item scales that captured difficulty with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, both of which ranged from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater limitations.60 Finally, we constructed a categorial covariate to account for variation across time. Stepwise regressions were performed to examine the association between social isolation and each outcome before and after adjusting for demographics, health behaviors, health conditions, loneliness scores, and depressive symptom scores (Table 2). In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for history of hospitalization and SNF stays and also stratified the models by sex to determine whether the patterns of associations were consistent for women and men.

Table 2. Stepwise Regressions Estimating the Role of Social Isolation on Hospital Stays and Nursing Home Use Before and After Adjusting for Covariatesa.

| Model | Included variables | Hospitalization | Skilled nursing facility stays | Nursing home placement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | MME (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | MME (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | MME (95% CI) | ||

| A | Social isolation score only | 1.10 (1.06 to 1.12)b | 0.016 (0.010 to 0.022)b | 1.42 (1.31 to 1.54)b | 0.010 (0.007 to 0.012)b | 2.22 (1.91 to 2.58)b | 0.012 (0.010 to 0.014)b |

| B | Plus demographics | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.08) | 0.005 (−0.001 to 0.012) | 1.24 (1.14 to 1.36)b | 0.006 (0.004 to 0.009)b | 1.86 (1.49 to 2.33)b | 0.007 (0.005 to 0.010)b |

| C | Plus behavior covariates | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | 0.002 (−0.004 to 0.009) | 1.22 (1.11 to 1.33)b | 0.006 (0.003 to 0.008)b | 1.83 (1.47 to 2.28)b | 0.007 (0.005 to 0.009)b |

| D | Plus health covariates | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.03) | −0.002 (−0.008 to 0.004) | 1.16 (1.07 to 1.27)b | 0.004 (0.002 to 0.007)b | 2.00 (1.39 to 2.87)b | 0.006 (0.004 to 0.009)b |

| E | Plus loneliness | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.01) | −0.004 (−0.011 to 0.002) | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.27)b | 0.004 (0.001 to 0.007)c | 1.94 (1.28 to 2.93)c | 0.005 (0.003 to 0.008)b |

| F | Plus depression | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) | −0.005 (−0.011 to 0.001) | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.28)b | 0.004 (0.002 to 0.007)b | 2.01 (1.21 to 3.32)c | 0.005 (0.003 to 0.008)b |

Abbreviations: MME, mean marginal effects; OR, odds ratio.

Estimates represent ORs or MMEs for social isolation scores. Model A, unadjusted (social isolation); model B, adjusting for social isolation in model A, sex, age, racial identity, ethnic identity, and Medicaid status; model C, adjusting for factors in models A and B, smoking status, and physical activity; model D, adjusting for factors in models A, B, and C, difficulty with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, number of chronic illnesses, Alzheimer disease or related dementias, and time; model E, adjusting for factors in models A, B, C, and D, and loneliness scores; model F, adjusting for factors in models A, B, C, D, and E and depressive symptom scores.

Significant at P ≤ .001.

Significant at P < .01.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were reported for the full sample (Table 1). In addition, subgroup characteristics were compared for older adults whose social isolation scores were low (<3) or high (≥3) using χ2 tests and t tests (Table 1). Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regressions that nested person-years within unique individuals were used to model whether continuous social isolation scores were associated with increased odds of hospitalization, SNF stays, and nursing home placement during 2-year periods while adjusting for loneliness, depressive symptoms, sociodemographics, health behaviors, and health conditions (eTables 2, 3, and 4 in Supplement 1).23 Mean marginal effects were also computed (Table 2). Respondents with social isolation scores and covariates available at their index interview but who died before follow-up were not included in analyses (n = 1670). Respondent-level survey sampling weights constructed by HRS for the SAQ were applied to adjust for the complex survey design of HRS and to produce nationally representative estimates.42 In multilevel modeling, we included the respondent-level weights for person-years in level 1 and the ratio of wave weight to initial weight for unique individuals in level 2, using the Stata command svyset hhidpn, weight(saq_wgt) || _n, weight(weight_rat). All empirical analyses were performed with Stata version 16 (StataCorp LLC), including the melogit command for multilevel regressions. P values were 2-sided, with the level of significance at P = .05. The George Mason University institutional review board determined this research study was exempt from the need for informed consent because of the deidentified nature of the data.61 This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Results

This study included a sample of 21 294 person-year observations derived from 11 517 community-dwelling older adults in the US. A total of 57% of participants were female, 43% were male, 8.4% were Black, 6.7% were Hispanic or Latino, 88.1% were White, 3.5% were other (“other” includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, and other race, which has no further breakdown available because this variable was obtained directly from the HRS), and 58.2% were aged 65 to 74 years. Approximately 15% were socially isolated, 23% were lonely, and 12% were classified as having depressive symptomology across each wave. In any given 2-year period, approximately 30% of respondents experienced a hospitalization, 4% had an SNF stay, and 2% transitioned from the community to a nursing home for long-term care (Table 1). Statistical analyses from χ2 tests and t tests showed that older adults with social isolation scores of 3 or higher had significantly more SNF stays and nursing home placement but not more hospitalization. Older adults with social isolation scores of 3 or higher also tended to have higher loneliness and depressive symptom scores; were more often female, older, Medicaid enrollees, currently smoking, and not physically active; had more difficulty with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living and more chronic illnesses; and were more likely to report having received a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease or a related dementia (Table 1).

In unadjusted models, each additional point in an older adult’s social isolation score was significantly associated with 1.10 times greater odds of hospitalization (95% CI, 1.06-1.12), 1.42 times greater odds of SNF stays (95% CI, 1.31-1.54), and 2.22 times greater odds of nursing home placement (95% CI, 1.91-2.58) during the course of 2 years (Table 2). In fully adjusted models, higher social isolation scores remained a significant indicator of future SNF stays. Each additional point in an older adult’s social isolation score put him or her at 1.16 times greater odds (95% CI, 1.06-1.28) of having an SNF stay during 2 years. Typically, the estimated probability of having an SNF stay within 2 years increased by 0.4 percentage points with each additional point in an individual’s social isolation score. Higher depressive symptom scores (odds ratio [OR], 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02-1.15) were associated with greater odds of having an SNF stay, although loneliness scores were not (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.92-1.07) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Fully adjusted models also demonstrated that for each point increase in an older adult’s social isolation score, the odds of nursing home placement doubled (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.21-3.32). Typically, the estimated probability of nursing home placement within 2 years increased by half a percentage point with each additional point in an individual’s social isolation score. Higher loneliness scores were associated with increased odds of nursing home placement (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.08-1.90), but depressive symptom scores were not (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.84-1.23) (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

In fully adjusted models, higher social isolation scores were associated with 0.97 times lower odds of hospitalization during 2 years, but this trend did not meet statistical significance (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.93-1.01). Higher depressive symptom scores (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.06-1.12), but not loneliness scores (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.98-1.05), were associated with significantly higher odds of hospitalization across the sample of older adults during 2 years (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for history of hospitalization and SNF use and found consistent results for social isolation. In sex-stratified models, higher social isolation scores remained significantly associated with increased odds of nursing home placement for both men (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.00-2.82) and women (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.20-2.54). Social isolation scores were associated with SNF stays for women (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.04-1.30), but this association did not reach statistical significance for men (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.00-1.37). The association between social isolation and hospitalization remained insignificant for both women (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.92-1.02) and men (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91-1.03).

Discussion

This study examined associations of social isolation with hospitalization, SNF stays, and nursing home placement among a nationally representative panel of community-dwelling older adults. After adjusting for loneliness and depressive symptoms, higher levels of social isolation remained significantly associated with increased odds of SNF stays and nursing home placement, but not with hospitalization. Each additional point in an individual’s social isolation score increased his or her estimated probability of nursing home placement by half a percentage point, doubling the odds of nursing home placement within 2 years. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate a significant association between long-term nursing home placement and social isolation among a nationally representative cohort of older adults in the US.

Among the few epidemiologic studies examining psychosocial risks for nursing home entry, most do not include objective and subjective measures of social connection.45 The present study found that future nursing home placement had stronger associations with social isolation than with loneliness. The associations between loneliness and health remain important and should not be overlooked. Nonetheless, this and past research suggest that policies and practices seeking to use aspects of social health to reduce nursing home use should consider targeting social isolation, which is associated with postacute and long-term nursing home use.14,45

The objective nature of social isolation has great potential for intervention. Older adults who are socially isolated tend to have fewer caregivers, potentially increasing their reliance on nursing homes for postacute recovery and long-term care. Furthermore, nursing homes may offer safe living environments and fulfill important social needs that might otherwise go unmet for older adults with limited social contact at home or in the community. Medical and social programs and policies that deliver additional points of contact to patients in their own environment, such as through home-based primary care, Medicaid-covered home and community-based services, or the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, could provide an avenue through which social isolation can be identified and addressed for community-dwelling older adults. By bolstering social connection for people living in home- and community-based settings, such programs might offset transitions to nursing homes for older adults who might otherwise seek placement there to access support.

We did not find evidence that social isolation was associated with hospitalization. Research on social isolation and hospital use tends to be limited to subpopulations (eg, certain payers) and yields mixed evidence.1,14,33,34 We hypothesized that socially isolated older adults would be at increased risk for hospitalization because of forgone preventive care and worsened physical and mental health. However, this was not supported by our fully adjusted models. It is possible that socially isolated older adults lack support persons who might otherwise flag a perceived or actual need to visit the emergency department or who could provide transportation there. Furthermore, individuals who truly require hospitalization may seek it regardless of social support levels. Future research should examine the association between social isolation and length of stay, reason for admission, and potentially avoidable admissions. Additionally, intervention studies should consider the hospital setting as a unique opportunity to interact with the most socially isolated older adults and provide them with resources.62,63

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the data were observational, making it difficult to draw causal conclusions. For instance, social isolation may be more common in older adults with a higher severity of illness, and it may be this proportion of illness rather than social isolation that is associated with health care use. However, previous work in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging yielded similar results after attenuating this concern by excluding the sickest participants.32 The use of instrumental variables for social isolation may further elucidate this possibility.

Second, rates of social isolation, chronic illness, hospitalization, and nursing home use were likely underreported. However, past research has found relatively good concordance between administrative or claims-based records and self-reported use of costly health care services.64,65 Using self-reported data also allowed us to generalize findings to older adults with a variety of insurance types (eg, not limited to Medicare fee-for-service claims). It is also likely that socially isolated individuals were harder to locate and recruit and thus less likely to participate in this study.1,66 Additionally, hospital and nursing home use was not estimated for respondents who died before follow-up. Given the close ties between social isolation and mortality,27 we believe that a stronger association between social isolation and costly forms of health care use would have been observed if those individuals had survived. Problems associated with underreporting, underrepresentation, and attrition likely lead to underestimates of the true associations between social isolation and hospital and nursing home use.

Third, the data set did not include some factors that could be associated with access to care (eg, precise geographic indicators, proximity or transportation to clinical locations, and attitudes about health care use).67 Limited social supports may also be associated with other forms of health care use that were not examined here (eg, home care, outpatient care, and inpatient rehabilitation), but that should be examined in future research. Finally, the social isolation measure used in this study was adapted from a body of research using the English Longitudinal Study of Aging, an HRS sister study.7,13,18,29,32,46 Although validated measures of social isolation exist,4,68 psychometric testing is needed to validate the present measure for HRS.

Conclusions

This cohort study provides new evidence regarding social isolation as a significant risk factor for SNF stays and nursing home placement among older adults. To our knowledge, it is the first study to investigate the association between social isolation and nursing home placement in a nationally representative, longitudinal sample of adults aged 65 years or older in the US. This research also addresses methodological limitations of previous studies by using an objective, multidomain measure of social isolation while adjusting for loneliness and depressive symptoms in the same sample. The implications of social isolation for adverse health outcomes have become increasingly salient in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. Research examining the burden of social isolation on hospitalization and nursing home use among older adults is critical to informing efforts that have stemmed from the pandemic to reduce social isolation among older adults. This study contributes new data to inform planning by public health officials and health systems as they develop interventions to reduce social isolation. Future research to improve aging in place through enhanced social connection can use objective social isolation measures to identify older adults who are at greater risk of nursing home entry.

eFigure. Stacked Data Structure Used to Examine the Impact of Social Isolation on Outcomes Over the Following Two Years Using the Health and Retirement Study

eTable 1. Six-Item Measure of Social Isolation in the Health and Retirement Study

eTable 2. Factors Associated With Hospitalization Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Skilled Nursing Facility Stays Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults

eTable 4. Factors Associated With Nursing Home Placement Among Previously Community-Dwelling Older Adults

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: opportunities for the health care system. National Academies Press; 2020. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25663 [PubMed]

- 2.Cudjoe TKM, Roth DL, Szanton SL, Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Thorpe RJ. The epidemiology of social isolation: National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(1):107-113. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodgson S, Watts I, Fraser S, Roderick P, Dambha-Miller H. Loneliness, social isolation, cardiovascular disease and mortality: a synthesis of the literature and conceptual framework. J R Soc Med. 2020;113(5):185-192. doi: 10.1177/0141076820918236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Measuring social isolation among older adults using multiple indicators from the NSHAP study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(suppl 1):i38-i46. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plick NP, Ankuda CK, Mair CA, Husain M, Ornstein KA. A national profile of kinlessness at the end of life among older adults: findings from the Health and Retirement Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(8):2143-2151. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ida S, Kaneko R, Imataka K, et al. Factors associated with social isolation and being homebound among older patients with diabetes: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e037528. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar A, McMunn A, Demakakos P, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Social isolation and loneliness: prospective associations with functional status in older adults. Health Psychol. 2017;36(2):179-187. doi: 10.1037/hea0000437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bu F, Abell J, Zaninotto P, Fancourt D. A longitudinal analysis of loneliness, social isolation and falls amongst older people in England. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20064. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77104-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pohl JS, Cochrane BB, Schepp KG, Woods NF. Falls and social isolation of older adults in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2018;11(2):61-70. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20180216-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cudjoe TKM, Prichett L, Szanton SL, Roberts Lavigne LC, Thorpe RJ Jr. Social isolation, homebound status, and race among older adults: findings from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (2011-2019). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(7):2093-2100. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evid Based Nurs. 2014;17(2):59-60. doi: 10.1136/eb-2013-101379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi H, Irwin MR, Cho HJ. Impact of social isolation on behavioral health in elderly: systematic review. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(4):432-438. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i4.432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011;30(4):377-385. doi: 10.1037/a0022826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw JG, Farid M, Noel-Miller C, et al. Social isolation and Medicare spending: among older adults, objective social isolation increases expenditures while loneliness does not. J Aging Health. 2017;29(7):1119-1143. doi: 10.1177/0898264317703559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pohl JS, Cochrane BB, Schepp KG, Woods NF. Measuring social isolation in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2017;10(6):277-287. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20171002-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu TL, Hall BJ, Canham SL, Lam AIF. The association between social capital and depression among Chinese older adults living in public housing. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204(10):764-769. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lara E, Caballero FF, Rico-Uribe LA, et al. Are loneliness and social isolation associated with cognitive decline? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(11):1613-1622. doi: 10.1002/gps.5174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shankar A, Hamer M, McMunn A, Steptoe A. Social isolation and loneliness: relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(2):161-170. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31827f09cd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Oude Voshaar RC, et al. Social relationships and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;22:39-57. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Zuidema SU, et al. Social relationships and cognitive decline: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(4):1169-1206. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penninkilampi R, Casey AN, Singh MF, Brodaty H. The association between social engagement, loneliness, and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(4):1619-1633. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang AR, Roth DL, Cidav T, et al. Social isolation and 9-year dementia risk in community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(3):765-773. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for CVD: implications for evidence-based patient care and scientific inquiry. Heart. 2016;102(13):987-989. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102(13):1009-1016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(3):578-583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511085112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golaszewski NM, LaCroix AZ, Godino JG, et al. Evaluation of social isolation, loneliness, and cardiovascular disease among older women in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2146461. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227-237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crowe CL, Domingue BW, Graf GH, Keyes KM, Kwon D, Belsky DW. Associations of loneliness and social isolation with health span and life span in the US Health and Retirement Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(11):1997-2006. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glab128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Artiga S, Hinton E. Beyond health care: the role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. Kaiser Family Foundation. Published May 10, 2018. Accessed November 16, 2020. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/

- 31.Determinants of health. World Health Organization. Published February 3, 2017. Accessed November 16, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/determinants-of-health

- 32.Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):5797-5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veazie S, Gilbert J, Winchell K, Paynter R, Guise JM. Addressing Social Isolation to Improve the Health of Older Adults: A Rapid Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2019. doi: 10.23970/AHRQEPC-RAPIDISOLATION [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosen DM, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, et al. Social isolation associated with future health care utilization. Popul Health Manag. 2021;24(3):333-337. doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hajek A, Luppa M, Brettschneider C, et al. Correlates of institutionalization among the oldest old—evidence from the multicenter AgeCoDe-AgeQualiDe study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(7):1095-1102. doi: 10.1002/gps.5548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valtorta NK, Moore DC, Barron L, Stow D, Hanratty B. Older adults’ social relationships and health care utilization: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):e1-e10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coyle CE, Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. 2012;24(8):1346-1363. doi: 10.1177/0898264312460275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Sullivan R, Burns A, Leavey G, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on loneliness and social isolation: a multi-country study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):9982. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18199982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Health and Retirement Study. University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research. Accessed March 3, 2022. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/about

- 40.Sample sizes and response rates: Health and Retirement Study. University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research. Published April 2017. Accessed March 3, 2022. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/publications/biblio/9042

- 41.RAND HRS longitudinal file 2020 (V1). RAND Social and Economic Well-being. RAND Corporation. Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.rand.org/well-being/social-and-behavioral-policy/centers/aging/dataprod/hrs-data.html

- 42.Smith J, Ryan L, Fisher G, Sonnega A, Weir D. HRS Psychosocial and Lifestyle Questionnaire 2006-2016: documentation report core section LB. Published July 2017. Accessed October 18, 2021. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/biblio/HRS%202006-2016%20SAQ%20Documentation_07.06.17_0.pdf

- 43.Kotwal AA, Cenzer IS, Waite LJ, et al. The epidemiology of social isolation and loneliness among older adults during the last years of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(11):3081-3091. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coyle C. The Effects of Loneliness and Social Isolation on Hypertension in Later Life: Including Risk, Diagnosis and Management of the Chronic Condition. University of Massachusetts Boston; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanratty B, Stow D, Collingridge Moore D, Valtorta NK, Matthews F. Loneliness as a risk factor for care home admission in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing. 2018;47(6):896-900. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rafnsson SB, Orrell M, d’Orsi E, Hogervorst E, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social integration, and incident dementia over 6 years: prospective findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(1):114-124. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Office of the Surgeon General, Public Health Service . Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, Kane RL. Predicting nursing home admission in the US: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843-857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi LC, Steptoe A. Social isolation, loneliness, and health behaviors at older ages: longitudinal cohort study. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(7):582-593. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(1):31-48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys. Res Aging. 2004;26(6):655-672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML. Developing a measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess. 1978;42(3):290-294. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(3):472-480. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11(2):139-148. doi: 10.1017/S1041610299005694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Briggs R, Carey D, O’Halloran AM, Kenny RA, Kennelly SP. Validation of the 8-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in a cohort of community-dwelling older people: data from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Eur Geriatr Med. 2018;9(1):121-126. doi: 10.1007/s41999-017-0016-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. Major depression in community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: prevalence and 2- and 4-year follow-up symptoms. Psychol Med. 2004;34(4):623-634. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steffick D. Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2000. doi: 10.7826/ISR-UM.06.585031.001.05.0005.2000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zivin K, Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, et al. Depression among older adults in the United States and England. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(11):1036-1044. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181dba6d2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Overview of the health measures in the Health and Retirement Study. J Hum Resour. 1995;30:S84-S107. doi: 10.2307/146279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) . 45 CFR 46. US Dept of Health and Human Services. Published March 10, 2021. Accessed June 14, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html

- 62.Falvey JR, Cohen AB, O’Leary JR, Leo-Summers L, Murphy TE, Ferrante LE. Association of social isolation with disability burden and 1-year mortality among older adults with critical illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(11):1433-1439. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.5022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perissinotto C, Holt-Lunstad J, Periyakoil VS, Covinsky K. A practical approach to assessing and mitigating loneliness and isolation in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):657-662. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Short ME, Goetzel RZ, Pei X, et al. How accurate are self-reports? analysis of self-reported health care utilization and absence when compared with administrative data. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(7):786-796. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a86671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raina P, Torrance-Rynard V, Wong M, Woodward C. Agreement between self-reported and routinely collected health-care utilization data among seniors. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(3):751-774. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pomeroy ML, Gimm G, Cuellar A, Ihara E, Cudjoe T. Associations between social isolation and hospital stays, nursing home entry, and mortality over time. Innovation Aging. 2023;6(S1):180. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igac059.721 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cayenne NA, Jacobsohn GC, Jones CMC, et al. Association between social isolation and outpatient follow-up in older adults following emergency department discharge. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;93:104298. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist. 2006;46(4):503-513. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Stacked Data Structure Used to Examine the Impact of Social Isolation on Outcomes Over the Following Two Years Using the Health and Retirement Study

eTable 1. Six-Item Measure of Social Isolation in the Health and Retirement Study

eTable 2. Factors Associated With Hospitalization Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Skilled Nursing Facility Stays Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults

eTable 4. Factors Associated With Nursing Home Placement Among Previously Community-Dwelling Older Adults

Data Sharing Statement