This cohort study investigates the association of dementia with early-, middle-, and late-life depression in a Danish cohort.

Key Points

Question

Does the association between depression and dementia persist whether depression is diagnosed in early, middle, or late life?

Findings

In this population cohort study of more than 1.4 million adult Danish citizens followed up from 1977 to 2018, the risk of dementia more than doubled for both men and women with diagnosed depression and was higher for men than women; the risk of dementia persisted whether depression was diagnosed in early, middle, or late life.

Meaning

Dementia risk associated with depression diagnosis was higher for men than women; the persistent association between dementia and depression diagnosed in early and middle life suggests that depression may increase dementia risk.

Abstract

Importance

Late-life depressive symptoms are associated with subsequent dementia diagnosis and may be an early symptom or response to preclinical disease. Evaluating associations with early- and middle-life depression will help clarify whether depression influences dementia risk.

Objective

To examine associations of early-, middle-, and late-life depression with incident dementia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a nationwide, population-based, cohort study conducted from April 2020 to March 2023. Participants included Danish citizens from the general population with depression diagnoses who were matched by sex and birth year to individuals with no depression diagnosis. Participants were followed up from 1977 to 2018. Excluded from analyses were individuals followed for less than 1 year, those younger than 18 years, or those with baseline dementia.

Exposure

Depression was defined using diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) within the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) and Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (DPCRR).

Main Outcomes and Measure

Incident dementia was defined using ICD diagnostic codes within the DPCRR and DNPR. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine associations between depression and dementia adjusting for education, income, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, anxiety disorders, stress disorders, substance use disorders, and bipolar disorder. Analyses were stratified by age at depression diagnosis, years since index date, and sex.

Results

There were 246 499 individuals (median [IQR] age, 50.8 [34.7-70.7] years; 159 421 women [64.7%]) with diagnosed depression and 1 190 302 individuals (median [IQR] age, 50.4 [34.6-70.0] years; 768 876 women [64.6%]) without depression. Approximately two-thirds of those diagnosed with depression were diagnosed before the age of 60 years (684 974 [67.7%]). The hazard of dementia among those diagnosed with depression was 2.41 times that of the comparison cohort (95% CI, 2.35-2.47). This association persisted when the time elapsed from the index date was longer than 20 to 39 years (hazard ratio [HR], 1.79; 95% CI, 1.58-2.04) and among those diagnosed with depression in early, middle, or late life (18-44 years: HR, 3.08; 95% CI, 2.64-3.58; 45-59 years: HR, 2.95; 95% CI, 2.75-3.17; ≥60 years: HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 2.25-2.38). The overall HR was greater for men (HR, 2.98; 95% CI, 2.84-3.12) than for women (HR, 2.21; 95% CI, 2.15-2.27).

Conclusions and Relevance

Results suggest that the risk of dementia was more than doubled for both men and women with diagnosed depression. The persistent association between dementia and depression diagnosed in early and middle life suggests that depression may increase dementia risk.

Introduction

Dementia is an urgent global public health problem associated with tremendous individual, societal, and economic costs.1,2,3,4 The prevalence of dementia is expected to grow commensurate with increased life expectancy and the aging of populations worldwide.1,2

Depressive symptoms frequently precede dementia onset,5,6,7,8,9 yet debate persists regarding the mechanisms that relate depression to dementia.10 First, depression and dementia may share common genetic predisposition or neuropathologic substrates.11,12,13 Second, depressive symptoms may arise in response to cognitive decline (ie, reverse causality).14 Third, depression may be an early symptom of dementia, a mechanism that is supported by an estimated 2- to 5-fold increased risk for dementia associated with late-life depression in prior studies.15,16,17,18,19,20,21 Finally, depression that occurs early in life may play an etiologic role in dementia onset20,22,23 through loss of noradrenaline-producing neurons in the locus coeruleus,24,25 loss of serotonin-producing neurons in the dorsal raphe nuclei,24 chronic glucocorticoid secretion,26,27 release of inflammatory cytokines,11,28 and other potential mechanisms. Whether depression is an early clinical manifestation of underlying dementia, a reactive symptom, an independent risk factor, or some combination thereof carries diagnostic and therapeutic implications. However, findings to date regarding the importance of early- and middle-life depression for dementia risk remain inconsistent due to differences in study population, insufficient numbers of younger patients, limited follow-up, and differences in the assessment of depression and dementia.22,29

Building on prior research, we leveraged more than 40 years of prospectively collected Danish registry data to examine the association of early-, middle-, and late-life depression with incident dementia. Because the process of neurodegeneration in dementia evolves over many years before the disease is clinically apparent, depression diagnosed in late life is generally recognized as an early symptom or as an effect of preclinical disease. By contrast, a persistent association between dementia and depression diagnosed in early or middle life would suggest that depression increases the risk for dementia. We hypothesized that the association between depression and dementia would persist regardless of time since the index date or age at depression diagnosis.

Methods

According to Danish law, registry-based research does not require ethical approval and informed consent but only permission from the Danish Data Protection Board. This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. The Danish national health care system is government funded, ensuring free access to all medical services from hospitals, specialists, and general practitioners. This nationwide, population-based, cohort study used routinely and prospectively collected data from Danish population-based registries from 1977 to 2018.30 Records were linked at the individual level using the unique identification number assigned by the Danish Civil Registration System (DCRS) to all citizens upon birth or immigration.30,31 The Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) includes data from all Danish hospitals from 1977 and complete nationwide inpatient care coverage from 1978 onward.32,33,34 The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register contains information from every inpatient psychiatric encounter from 1970 onward and data for emergency department and outpatient visits from 1995 onward.35

This study included all adult members of the Danish general population diagnosed with depression. Comparison cohort members were randomly sampled with replacement from the Danish Civil Registration System and matched to individuals diagnosed with depression on sex, birth year, and the date of depression diagnosis (the index date) with a ratio of 5:1 to improve statistical efficiency.36 At matching, comparison cohort members did not have depression; they were censored for a depression diagnosis after the index date, and thereafter, they were included in the depression cohort. Baseline sociodemographic and health characteristics were measured beginning January 1, 1978, and depression diagnoses were recorded beginning January 1, 1980. Follow-up extended from 1 year after the index date until the occurrence of a dementia diagnosis, emigration, death, or study end on December 31, 2018 (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Individuals with less than 1 year of follow-up time, with a baseline dementia diagnosis, or those younger than 18 years were excluded. Patients were not involved in identifying the research question, outcome measures, or plans for study design and implementation. No patients were asked to advise on the interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community. This study is reported per the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Depression

Depression was defined using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic codes from the DNPR and the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (DPCRR) (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). A prior validation study demonstrated adequate positive predictive value (74.5%) for a single diagnosis of depression in the DPCRR.37

Dementia

Dementia diagnoses were identified using ICD codes from the DPCRR and the DNPR. Our outcome definition for all-cause dementia included Alzheimer disease, vascular dementia, and other dementias (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). A prior validation study suggested a positive predictive value of 85.8% for all-cause dementia in the DPCRR and DNPR.38 Because the outcome of interest was incident dementia, we excluded outcomes occurring less than 1 year after depression diagnosis to reduce bias from inclusion of undiagnosed prevalent cases (reverse causation).

Covariates

Age, sex, and marital status were available from the DCRS. Income quartile and employment status were available from the Integrated Database for Labor Market Research. Race and ethnicity are not routinely collected in the DCRS and therefore were not included as covariates in this study. Highest education was ascertained from the Educational Attainment Register. Baseline health characteristics were ascertained from the DNPR and DPCRR using ICD codes, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, stroke, head injuries, anxiety disorders, stress disorders, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, personality disorders, and suicide attempt (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). We computed a modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score excluding dementia, CVD, COPD, and diabetes.39 Treatment with antidepressants in the 6 months before and after the index date was ascertained from the Danish National Prescription Registry using Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical codes (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Statistical Analysis

To characterize the association between depression and dementia over the life course, analyses were stratified by time since index date (1-10 years; >10-20 years; >20-39 years) and by age at depression diagnosis (early life, 18-44 years; middle life, 45-59 years; late-life, ≥60 years).40,41 Because the risks of depression and dementia differ between women and men,42,43,44 we additionally conducted analyses within strata defined by sex. We first calculated dementia risk for those with depression diagnoses and for the comparison cohort using the cumulative incidence function, treating death as a competing event.45,46 Risk differences were calculated as the difference in dementia risk between those with depression diagnoses and the comparison cohort. We then used Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to estimate the association between depression and dementia. We assessed whether the proportional hazards assumption was satisfied based on visual inspection of the complementary log-log plot.47,48 We adjusted for baseline variables regarded as common causes of depression and dementia based on current knowledge. These included education, income, CVD, diabetes, anxiety disorders, stress disorders, substance use disorders, bipolar disorder, and COPD (as an indirect measure of smoking history). Missingness categories were included for education and income.

Secondary Analyses

We conducted the following exploratory secondary analyses. First, we assessed whether treatment at the time of diagnosis modified the association of depression with dementia. To do so, we repeated our main analysis within strata defined by whether an antidepressant medication was prescribed within the 6-month periods before and after the first depression diagnosis. Second, among those with at least 1 inpatient depression diagnosis, we examined the role of disease severity by analyzing the association between the number of inpatient hospitalizations, treated as a time-varying exposure, and dementia risk. Finally, we examined potential effect modification by baseline diagnosis of COPD, stroke, anxiety disorder, substance use disorder, or head injury.

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to ascertain the robustness of our results. First, we repeated our main analysis using semi-Bayes adjustments to address multiple estimation. Briefly, this technique assumes that the spread of estimated hazard ratios (HRs) is greater than the variation of the true but unknown HR, and the adjustment serves to shrink or attenuate outlying HRs toward the null value.49,50 Second, to better characterize the importance of age at depression diagnosis, we repeated our analysis within alternative age strata: 18 to 29, 30 to 39, 40 to 49, 50 to 59, and 60 years or older. Third, because individuals who receive an inpatient depression diagnosis may have more severe disease, we repeated our main analysis separately for inpatient and outpatient depression diagnoses. Fourth, to assess whether results were influenced by secular trends, we repeated our analysis by year of depression diagnosis. Fifth, we considered the association of depression with dementia subtypes (Alzheimer disease, vascular dementia, other dementias). Sixth, as individuals diagnosed with depression between ages 18 and 44 years were less likely to develop dementia over the study period, we restricted this analysis to age 45 years or older at baseline. Seventh, we repeated our main analysis including the first year of follow-up after the index date. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which comparison cohort members were not censored if subsequently diagnosed with depression. All analyses were conducted with SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

From 316 279 individuals first diagnosed with depression from 1980 to 2018, we excluded 32 410 as a result of age younger than 18 years or baseline diagnoses of dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or amnestic syndrome. We excluded 37 370 individuals who were followed up less than 1 year after depression diagnosis. The final sample included 246 499 individuals (median [IQR] age, 50.8 [34.7-70.7] years; 159 421 women [64.7%]; 87 078 men [35.3%]) with depression and 1 190 302 matched comparison cohort members (median [IQR] age, 50.4 [34.6-70.0] years; 768 876 women [64.6%]; 421 426 men [35.4%]) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1).

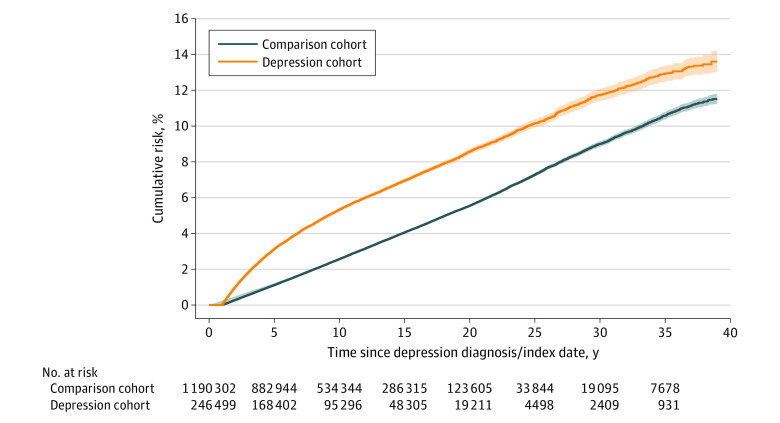

Median (IQR) follow-up was 7.89 (4.07-13.30) years for those with a depression diagnosis and 9.04 (4.87-14.74) years in the comparison cohort. Baseline health and sociodemographic characteristics for individuals with a depression diagnosis and members of the matched comparison cohort are presented in Table 1. Approximately two-thirds of patients with depressive disorders were women and were diagnosed with depression before age 60 years (684 974 [67.7%]). The minority of patients (55 435 [22.5%]) were in the lowest income quartile at baseline. The most common comorbidity was CVD (48 689 [19.8%]). All baseline health characteristics occurred less frequently among members of the matched comparison cohort. Among those with a depression diagnosis, 14 000 (5.7%) were subsequently diagnosed with dementia. In the comparison cohort, there were 38 652 dementia diagnoses (3.2%). Accounting for the competing risk of death, the estimated risk of dementia over the study period was 13.6% (95% CI, 13.0-14.2) among those with a depression diagnosis and 11.5% (95% CI, 11.3-11.8) among members of the comparison cohort. The overall risk difference was 2.09% (95% CI, 0.81-3.37). By sex, the risk difference was greater among men. By age, the risk difference was greatest among those 60 years or older at depression diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline Health and Sociodemographic Characteristics Among Individuals With a Depression Diagnosis and Members of the Comparison Cohorta.

| Characteristic | Depression diagnosis | Comparison cohort | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, No. (%) | 246 499 (100) | 1 190 302 (100) | |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Female | 159 421 (64.7) | 768 876 (64.6) | .46 |

| Male | 87 078 (35.3) | 421 426 (35.4) | |

| Age, No. (%), y | |||

| 18-44 | 109 396 (44.4) | 539 861 (45.4) | <.001 |

| 45-59 | 575 578 (23.4) | 284 927 (23.9) | |

| 60+ | 79 524 (32.3) | 365 514 (30.7) | |

| Year of diagnosis, No. (%) | |||

| 1980-1989 | 12 213 (5.0) | 60 096 (5.0) | .24 |

| 1990-1999 | 42 372 (17.2) | 204 132 (17.1) | |

| 2000-2009 | 97 751 (39.7) | 471 066 (39.6) | |

| 2010-2018 | 94 163 (38.2) | 455 008 (38.2) | |

| Highest education, No. (%)c | |||

| Basic education | 98 952 (40.1) | 383 966 (32.3) | <.001 |

| Youth education | 80 206 (32.5) | 426 828 (35.9) | |

| Higher education | 39 113 (15.9) | 244 562 (20.5) | |

| Missing | 28 228 (11.5) | 134 946 (11.3) | |

| Employment status, No. (%) | |||

| Employed | 99 401 (40.3) | 687 300 (57.7) | <.001 |

| Unemployed | 38 815 (15.7) | 110 497 (9.3) | |

| Early retirement | 41 570 (16.9) | 104 813 (8.8) | |

| State pension | 65 290 (26.5) | 268 592 (22.6) | |

| Missing | 1423 (0.6) | 19 100 (1.6) | |

| Income quartile, No. (%)d | |||

| Below Q1 | 55 435 (22.5) | 239 594 (20.1) | <.001 |

| Q1-Q2 | 77 315 (31.4) | 272 776 (22.9) | |

| Q2-Q3 | 69 952 (28.4) | 313 921 (26.4) | |

| Q3 and above | 43 120 (17.5) | 354 518 (29.8) | |

| Missing | 677 (0.3) | 9493 (0.8) | |

| Marital status, No. (%) | |||

| Married or registered partner | 98 335 (39.9) | 565 060 (47.5) | <.001 |

| Divorced | 33 480 (13.6) | 103 786 (8.7) | |

| Widowed | 28 376 (11.5) | 119 061 (10.0) | |

| Never married | 82 402 (33.4) | 374 725 (31.5) | |

| Missing | 3906 (1.6) | 27 670 (2.3) | |

| Modified CCI, No. (%)e | |||

| Low | 202 221 (82.0) | 1 060 947 (89.1) | <.001 |

| Moderate | 21 224 (8.6) | 56 978 (4.8) | |

| Severe | 15 418 (6.3) | 55 313 (4.6) | |

| Very severe | 7636 (3.1) | 17 064 (1.4) | |

| Baseline health characteristics, No. (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 48 689 (19.8) | 140 090 (11.8) | <.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 11 359 (4.6) | 24 320 (2.0) | |

| Diabetes | 11 403 (4.6) | 29 165 (2.5) | |

| Stroke | 13 855 (5.6) | 29 575 (2.5) | |

| Head injuries | 18 469 (7.5) | 50 976 (4.3) | |

| Anxiety disorders | 15 803 (6.4) | 13 655 (1.1) | |

| Stress disorders | 22 592 (9.2) | 15 896 (1.3) | |

| Bipolar disorder | 10 408 (4.2) | 3619 (0.3) | |

| Substance use disorders | 28 877 (11.7) | 30 523 (2.6) | |

| Personality disorders | 13 578 (5.5) | 9182 (0.8) | |

| Suicide attempt | 5932 (2.4) | 5009 (0.4) |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; Q, quartile.

To ensure correct temporal ordering, baseline sociodemographic and health characteristics were measured 2 years before the onset of depression, with baseline characteristics measured beginning January 1, 1978, and depression diagnoses recorded beginning January 1, 1980.

Calculated using χ2 test for categorical variables.

Basic education includes 1 preschool year and 9 school years (grades 1-9); youth education includes high school (grades 10-12); higher education includes university education.

Reflects individual income in the year before the index date.

The CCI is summary measure of hospital-diagnosed comorbidity burden characterized as follows: 0, low; 1, moderate; 2, severe; greater than 2, very severe. The CCI used in all analyses in the present study was modified to exclude diagnoses of dementia, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes.

Table 2. Dementia Risk Among Individuals With a Depression Diagnosis and Members of the Comparison Cohorta .

| Age | Depression diagnosis | Comparison cohort | Risk difference (95% CI)b | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events/No. at risk | Dementia risk (95% CI)a | Events/number at risk | Dementia risk (95% CI)a | |||

| Overall | ||||||

| 1-10 y | 10 774/246 499 | 5.33 (5.23 to 5.43) | 23 420/1 190 302 | 2.57 (2.53 to 2.60) | 2.76 (2.56 to 2.97) | <.001 |

| >10-20 y | 2637/95 296 | 4.55 (4.37 to 4.74) | 11 697/534 344 | 3.56 (3.49 to 3.62) | 1.00 (0.62 to 1.37) | |

| >20-39 y | 589/19 206 | 9.82 (8.74 to 11.0) | 3535/123 570 | 9.09 (8.68 to 9.52) | 0.73 (−1.55 to 3.01) | |

| 1-39 y | 14 000/246 499 | 13.6 (13.0 to 14.2) | 38 652/1 190 302 | 11.51 (11.2 to 11.8) | 2.09 (0.81 to 3.37) | |

| Women | ||||||

| 1-10 y | 7297/159 421 | 5.57 (5.45 to 5.70) | 17 092/768 876 | 2.89 (2.85 to 2.93) | 2.68 (2.42 to 2.95) | <.001 |

| >10-20 y | 1879/63 351 | 4.89 (4.66 to 5.12) | 8660/348 215 | 4.00 (3.91 to 4.09) | 0.89 (0.41 to 1.37) | |

| >20-39 y | 450/13 286 | 10.3 (9.12 to 11.5) | 2665/83 321 | 9.73 (9.26 to 10.2) | 0.53 (−1.91 to 2.97) | .68 |

| 1-39 y | 9626/159 421 | 14.5 (13.8 to 15.1) | 28 417/768 876 | 12.6 (12.3 to 12.9) | 1.88 (0.47 to 3.29) | <.001 |

| Men | ||||||

| 1-10 y | 3477/87 078 | 4.86 (4.70 to 5.02) | 6328/421 426 | 1.97 (1.92 to 2.01) | 2.89 (2.57 to 3.22) | <.001 |

| >10-20 y | 758/31 945 | 3.87 (3.58 to 4.17) | 3037/186 129 | 2.70 (2.60 to 2.81) | 1.16 (0.57 to 1.75) | |

| >20-39 y | 139/5920 | 8.85 (6.30 to 11.9) | 870/40 249 | 7.67 (6.79 to 8.62) | 1.18 (−4.16 to 6.52) | .68 |

| 1-39 y | 4374/87 078 | 11.9 (10.6 to 13.4) | 10 235/421 426 | 9.35 (8.74 to 9.98) | 2.59 (−0.37 to 5.55) | .09 |

| 18-44 y | ||||||

| 1-10 y | 191/109 396 | 0.24 (0.20 to 0.27) | 140/539 861 | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) | 0.20 (0.13 to 0.26) | <.001 |

| >10-20 y | 141/51 680 | 0.51 (0.43 to 0.61) | 199/258 077 | 0.15 (0.13 to 0.18) | 0.36 (0.19 to 0.54) | |

| >20-39 y | 109/11 117 | 4.67 (3.71 to 5.79) | 310/61 304 | 2.75 (2.38 to 3.17) | 1.92 (−0.13 to 3.97) | .67 |

| 1-39 y | 441/109 396 | 4.83 (3.97 to 5.80) | 649/539 861 | 2.84 (2.48 to 3.24) | 1.99 (0.14 to 3.84) | .04 |

| 45-59 y | ||||||

| 1-10 y | 915/57 578 | 2.00 (1.87 to 2.13) | 796/284 927 | 0.38 (0.35 to 0.40) | 1.62 (1.37 to 1.88) | <.001 |

| >10-20 y | 678/26 671 | 4.26 (3.94 to 4.60) | 1456/150 333 | 1.67 (1.58 to 1.76) | 2.59 (1.94 to 3.25) | |

| >20-39 y | 310/6378 | 16.8 (14.2 to 19.7) | 1623/43 535 | 15.3 (14.3 to 16.3) | 1.57 (−3.99 to 7.12) | .59 |

| 1-39 y | 1903/57 578 | 15.5 (13.9 to 17.2) | 3875/284 927 | 14.3 (13.4 to 15.1) | 1.27 (−2.30 to 4.84) | .50 |

| ≥60 y | ||||||

| 1-10 y | 9668/79 525 | 14.0 (13.7 to 14.2) | 22 484/365 514 | 7.54 (7.45 to 7.64) | 6.43 (5.89 to 6.98) | <.001 |

| >10-20 y | 1818/16 945 | 14.6 (14.0 to 15.3) | 10 042/125 934 | 11.4 (11.2 to 11.6) | 3.21 (1.89 to 4.53) | |

| >20-39 y | 170/1711 | 16.4 (14.0 to 18.9) | 1602/18 731 | 15.5 (14.7 to 16.3) | 0.87 (−4.09 to 5.83) | .74 |

| 1-39 y | 11 656/79 525 | 20.1 (19.8 to 20.5) | 34 128/365 514 | 17.3 (17.1 to 17.5) | 2.86 (1.99 to 3.72) | <.001 |

For the study population overall and within strata defined by sex and age at depression diagnoses, we present results further stratified by the time elapsed between the index date and the depression diagnoses (1-10 years; >10-20 years; >20-30 years; 1-39 years).

Dementia risk per 100 individuals was calculated using the cumulative incidence function, accounting for the competing risk of death. Risk differences were calculated as the difference in dementia risk among individuals with a depression diagnosis and the comparison cohort. The null value for a risk difference is zero.

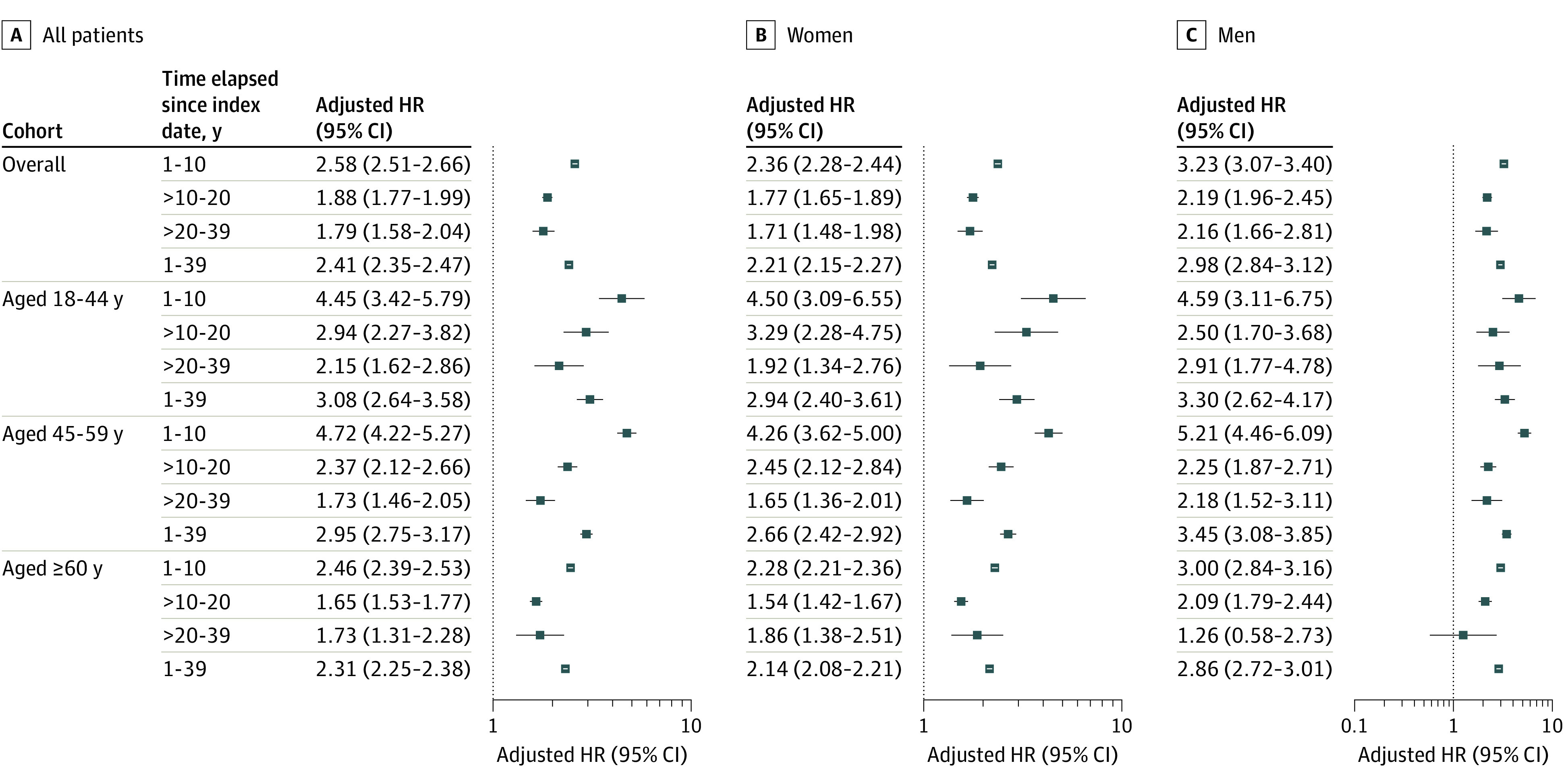

Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the association between depression diagnosis and subsequent dementia. The proportional hazards assumption was satisfied based on visual inspection of the complementary log-log plot (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1). Figure 1 depicts that the cumulative incidence of dementia was consistently increased among individuals with depression as compared with members of the comparison cohort. Figure 2 depicts the results of Cox regression analysis for the population overall and for men and women separately within strata defined by age and time elapsed since the index date. The overall hazard of dementia among those diagnosed with depression was 2.41 times that of the comparison cohort (95% CI, 2.35-2.47). This association persisted when the time elapsed from the index date was greater than 20 to 39 years (HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.58-2.04) and whether depression was diagnosed in early, middle, or late life (18-44 years: HR, 3.08; 95% CI, 2.64-3.58; 45-59 years: HR, 2.95; 95% CI, 2.75-3.17; ≥60 years: HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 2.25-2.38). By sex, the overall hazard of dementia was greater for men (HR, 2.98; 95% CI, 2.84-3.12) than for women (HR, 2.21; 95% CI, 2.15-2.27).

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Dementia for Individuals With Depression Diagnoses and Members of the Matched Comparison Cohort, 1980 to 2018.

Figure 2. Adjusted Hazard Ratios (HRs) for the Association Between Depression and Dementia by Sex, Age, and Time Elapsed From the Index Date, 1980 to 2018.

We used Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to estimate the association between depression and dementia. We adjusted for variables regarded as common causes of depression and dementia based on current knowledge that were measured at baseline: education, income, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, anxiety disorders, stress disorders, substance use disorders, and bipolar disorder. Missingness categories were included for the education and income covariates.

Secondary Analyses

Results were similar among patients who were and were not prescribed treatment with an antidepressant in the 6 months before or after depression diagnosis (treated: HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 2.35-2.49; not treated: HR, 2.35; 95% CI, 2.22-2.48) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Among the 113 629 individuals with at least 1 inpatient depression diagnosis, the hazard of dementia was further increased among those with multiple inpatient hospitalizations vs 1 inpatient hospitalization (2 hospitalizations: HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.21-1.46; 3 hospitalizations: HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.43-1.83; ≥4 hospitalizations: HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.39-1.60) (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Results were attenuated among persons diagnosed with CVD, COPD, stroke, anxiety disorder, and substance use disorder at baseline but were stronger for those with head injury (HR, 3.76; 95% CI, 2.30-6.13) vs those without (HR, 2.40; 95% CI, 2.34-2.46) (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

Sensitivity Analyses

Analysis of the association between depression and dementia using semi-Bayes adjustment were consistent with those of our main analysis (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Findings within different age strata showed a greater hazard of dementia observed among individuals diagnosed with depression between ages 18 and 29 years (HR, 4.85; 95% CI, 2.73-8.60) and between ages 30 and 39 years (HR, 3.10; 95% CI, 2.46-3.90). However, dementia diagnoses were relatively rare in these age strata, as evidenced by wide CIs (eTable 7 in Supplement 1). Findings were similar among those diagnosed with depression in the inpatient vs outpatient settings (eTable 8 in Supplement 1) and by year of depression diagnosis (eTable 9 in Supplement 1). We observed greater hazard of dementia for vascular dementia (HR, 3.28; 95% CI, 3.07-3.50) and a smaller hazard of dementia for Alzheimer disease (HR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.65-1.80) (eTable 10 in Supplement). Finally, results were consistent with those of our main analysis when we restricted our analysis to those 45 years or older at baseline, included the first year of follow-up after depression diagnosis, and when comparison cohort members were not censored on diagnosis of depression (eTables 11-13 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

This cohort study examined the association of early-, middle-, and late-life depression with subsequent dementia in Denmark. Findings support our hypothesis that associations would persist regardless of time since depression diagnosis or the age at which depression was diagnosed. The overall hazard of dementia for people with depression was more than doubled as compared with the comparison cohort. This association persisted when the time elapsed from the index date was greater than 20 years and when depression was diagnosed in early, middle, or late life. Our results therefore suggest that depression is not only an early symptom of dementia but also that depression is associated with an increase in dementia risk.

The recent Lancet 2020 report on dementia prevention highlighted results from several recent studies that focused on depression and dementia with sample sizes ranging from 4922 to 28 916 and follow-up between 14 and 25 years.10,51,52 Our analysis leverages routinely and prospectively collected data from more than 1.4 million Danish citizens followed up from 1977 to 2018, allowing for more precise estimates and examination of potential heterogeneities.

Consistent with prior studies, our results suggest an association between dementia and late-life depression, in keeping with the theorized role for depression as a reactive or early symptom of cognitive decline. For example, among 2160 community-dwelling Medicare recipients 65 years and older at baseline who were followed up in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP), late-life depression was associated with incident dementia.21 In 281 540 veterans 55 years and older at baseline (1997-2000), those with dysthymia or depression were twice as likely to develop incident dementia compared with those with no such diagnosis between 2001 and 2007.20 Among 949 participants in the Framingham Original Cohort, those with depressive symptoms at baseline (1990-1994) had more than 1.5-fold increased risk for subsequent dementia and Alzheimer disease vs those without baseline depression over the 17-year study period.16

Relatively fewer studies have had sufficient duration of follow-up to examine the association of early- or middle-life depression with dementia, and the findings to date remain inconsistent. For example, among 13 535 long-term members of the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California, depressive symptoms assessed in middle life (1964-1973) and late life (1994-2000) were associated with increased risk for incident all-cause dementia, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia between 2003 and 2009.22 By contrast, in an analysis of 10 308 individuals aged 35 to 55 years at baseline recruited to the Whitehall II study with follow-up from 1985 to 2015, depressive symptoms earlier in this study (corresponding to middle life) were not associated with significantly increased dementia risk. Depressive symptoms later in follow-up were, however, associated with increased dementia risk in this study.23

In our analyses, the risk of dementia was more than doubled in both men and women diagnosed with depression, although the hazard of dementia was greater in men. One possible explanation for this finding is that men are less likely to seek health care than women.53,54 Depressive symptoms among men may, therefore, reflect more severe disease at time of diagnosis, increasing the apparent risk of dementia associated with depression compared with the relative risk for women. Alternatively, differential mechanisms may mediate the association between depression and dementia among men, such as health behaviors, endogenous sex hormone exposures, or comorbid medical conditions. Ultimately, this finding warrants further examination in alternative settings where direct measures of depressive symptoms and time-dependent measures of possible mediating variables are available.

The increased risk of dementia associated with depression diagnosis raises the intriguing question of whether effective treatment of depression could modify dementia risk. Although findings were similar among those who were and were not treated with an antidepressant within 6 months of their depression diagnosis, our analysis does not consider the duration or effectiveness of treatment, nor were we able to identify individuals who received behavioral therapy. In our analysis of disease severity, recurrent inpatient hospitalizations were associated with increasing risk of dementia. Together, these results may motivate ongoing research focused on the complex and time-varying association between treatment and dementia, particularly when direct measures of disease burden and depression severity are available.

Finally, we found a persistent although attenuated association between depression and dementia among those with baseline anxiety disorder or substance use disorder. We were unable to examine effect modification by personality disorders, suicide attempts, bipolar disorder, or stress disorders (including posttraumatic stress disorder) due to the small number of dementia diagnoses within these strata. As several psychiatric disorders have been previously associated with dementia,55,56,57,58,59 the implications of co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses for dementia risk are an important topic for future research.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the sample size and duration of follow-up. However, results from this study, which are based on analysis of Danish registry data, may have imperfect or limited generalizability to other populations where risks for depression and dementia may differ. Selection bias was negligible, as we included all depression diagnoses among adult Danish citizens recorded within the study period and sampled comparison cohort members at random from the Danish general population. Our use of diagnostic codes to identify incident depression and dementia was a potential source of misclassification. However, earlier validation studies have demonstrated adequate positive predictive values for a single diagnosis of depression (74.5%) and a single diagnosis of dementia (85.5%) in Danish hospital registers.37,38 Registry data, however, limit our ability to precisely characterize resolution and recurrence of depression or its severity over the life course, both of which may influence dementia risk. Detection bias could contribute to some of our results (ie, dementia may have been more frequently diagnosed among individuals with depression who received treatment). Reassuringly, our findings remained consistent across sensitivity analyses for depression diagnoses in the inpatient and outpatient settings and regardless of time elapsed between diagnoses of depression and dementia.

Finally, we aimed to minimize confounding by including a comprehensive set of sociodemographic and health-related adjustment factors in all statistical models. These data do not include direct measures of smoking, a known risk factor for depression and dementia.60,61,62 As an alternative, we included COPD as an indirect proxy because prior studies showed that 97% of Danish patients with COPD have a history of smoking.63 We were further unable to account for several factors that may be important confounders of the association of interest, including family history, physical activity, dietary patterns, reproductive history, and social connectedness.64,65,66,67,68,69,70 The effect of residual confounding on the estimated results is unknown.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, among more than 1.4 million Danish citizens followed up from 1978 to 2018, the risk of dementia was more than doubled for both men and women with diagnosed depression. Our results suggest a persistent positive association when depression diagnosis precedes dementia diagnosis by more than 20 years and when depression is diagnosed in early or middle life. These results suggest that depression is associated with an increased risk of dementia.

eFigure 1. Study Timeline and Length of Follow-Up for Study Subjects and Data Sources, 1977-2018

eTable 1. Diagnostic Codes From the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth and Tenth Revisions (ICD-8 and ICD-10)

eTable 2. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Codes for Prescribed Antidepressants

eFigure 2. Flow Chart Depicting Exclusion Criteria for Patients Diagnosed with Depressive Disorders (Pane A) and Members of the Comparison Cohort (Panel B), 1977-2018

eFigure 3. Complementary Log-Log Plot for Proportional Hazards Assumption

eTable 3. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Treatment With Prescribed Antidepressant

eTable 4. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Frequency of Inpatient Encounters Among Those With a Depression Diagnosis

eTable 5. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Baseline Health Characteristics

eTable 6. Semi-Bayes Adjustment for Multiple Estimation

eTable 7. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia within Alternative Age Strata

eTable 8. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia for Inpatient and Outpatient Depression Diagnoses

eTable 9. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Year at Depression Diagnosis

eTable 10. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Dementia Subtypes

eTable 11. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia Restricted to Those Age ≥45 at Baseline

eTable 12. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia Including the First Year of Follow-Up

eTable 13. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia Without Censoring of Comparison Cohort Members

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Dementia Forecasting Collaborators GBD; GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators . Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(2):e105-e125. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease International . Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112-2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince M, Prina M, Guerchet M. World Alzheimer Report 2013—Journey of Caring: An Analysis of Long-Term Care for Dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer disease. Lancet. 2006;368(9533):387-403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park JH, Lee SB, Lee TJ, et al. Depression in vascular dementia is quantitatively and qualitatively different from depression in Alzheimer disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23(2):67-73. doi: 10.1159/000097039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballard C, Bannister C, Solis M, Oyebode F, Wilcock G. The prevalence, associations, and symptoms of depression amongst dementia sufferers. J Affect Disord. 1996;36(3-4):135-144. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00072-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballard C, Neill D, O’Brien J, McKeith IG, Ince P, Perry R. Anxiety, depression, and psychosis in vascular dementia: prevalence and associations. J Affect Disord. 2000;59(2):97-106. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00057-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuring JK, Mathias JL, Ward L. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and PTSD in people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2018;28(4):393-416. doi: 10.1007/s11065-018-9396-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi S, Wang C, Jiang T, Zhu X-C, Yu J-T, Tan L. The prevalence of depression in Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12(2):189-198. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666150204124310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413-446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye Q, Bai F, Zhang Z. Shared genetic risk factors for late-life depression and Alzheimer disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(1):1-15. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas AJ, Kalaria RNT, O’Brien JT. Depression and vascular disease: what is the relationship? J Affect Disord. 2004;79(1-3):81-95. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00349-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geda YE, Schneider LS, Gitlin LN, et al. ; Neuropsychiatric Syndromes Professional Interest Area of ISTAART . Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease: past progress and anticipation of the future. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):602-608. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bature F, Guinn BA, Pang D, Pappas Y. Signs and symptoms preceding the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease: a systematic scoping review of literature from 1937 to 2016. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e015746. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen K, Lolk A, Kragh-Sørensen P, Petersen NE, Green A. Depression and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Epidemiology. 2005;16(2):233-238. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000152116.32580.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saczynski JS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Auerbach S, Wolf PA, Au R. Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2010;75(1):35-41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e62138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gatz JL, Tyas SL, St John P, Montgomery P. Do depressive symptoms predict Alzheimer disease and dementia? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(6):744-747. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaup AR, Byers AL, Falvey C, et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms in older adults and risk of dementia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(5):525-531. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirza SS, Wolters FJ, Swanson SA, et al. 10-year trajectories of depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: a population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(7):628-635. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byers AL, Covinsky KE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K. Dysthymia and depression increase risk of dementia and mortality among older veterans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):664-672. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31822001c1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard E, Reitz C, Honig LH, et al. Late-life depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(3):374-382. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Byers AL, McCormick M, Schaefer C, Whitmer RA. Midlife vs late-life depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: differential effects for Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(5):493-498. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh-Manoux A, Dugravot A, Fournier A, et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms before diagnosis of dementia: a 28-year follow-up study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):712-718. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zweig RM, Ross CA, Hedreen JC, et al. The neuropathology of aminergic nuclei in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 1988;24(2):233-242. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Förstl H, Burns A, Luthert P, Cairns N, Lantos P, Levy R. Clinical and neuropathological correlates of depression in Alzheimer disease. Psychol Med. 1992;22(4):877-884. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700038459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sierksma AS, van den Hove DL, Steinbusch HW, Prickaerts J. Major depression, cognitive dysfunction, and Alzheimer disease: is there a link? Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;626(1):72-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butters MA, Young JB, Lopez O, et al. Pathways linking late-life depression to persistent cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10(3):345-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porcelli S, Crisafulli C, Donato L, et al. Role of neurodevelopment involved genes in psychiatric comorbidities and modulation of inflammatory processes in Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Sci. 2016;370:162-166. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.09.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byers AL, Yaffe K. Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(6):323-331. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. The Danish health care system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:563-591. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S179083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541-549. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):30-33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersen TF, Madsen M, Jørgensen J, Mellemkjoer L, Olsen JH. The Danish National Hospital Register: a valuable source of data for modern health sciences. Dan Med Bull. 1999;46(3):263-268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nickelsen TN. Data validity and coverage in the Danish National Health Registry: a literature review. Article in Danish. Ugeskr Laeger. 2001;164(1):33-37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raboud J, Breslow NE. Efficiency gains from the addition of controls to matched sets in cohort studies. Stat Med. 1989;8(8):977-985. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bock C, Bukh JD, Vinberg M, Gether U, Kessing LV. Validity of the diagnosis of a single depressive episode in a case register. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-5-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phung TKT, Andersen BB, Høgh P, Kessing LV, Mortensen PB, Waldemar G. Validity of dementia diagnoses in the Danish hospital registers. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24(3):220-228. doi: 10.1159/000107084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Lash TL, Sørensen HT. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson Comorbidity Index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brodaty H, Peters K, Boyce P, et al. Age and depression. J Affect Disord. 1991;23(3):137-149. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90026-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Age and depression. J Health Soc Behav. 1992;33(3):187-205. doi: 10.2307/2137349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. ; National Comorbidity Survey Replication . The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095-3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niu H, Álvarez-Álvarez I, Guillén-Grima F, Aguinaga-Ontoso I. Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer disease in Europe: a meta-analysis. Article in Spanish. Neurologia. 2017;32(8):523-532. English Edition. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2016.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anstey KJ, Peters R, Mortby ME, et al. Association of sex differences in dementia risk factors with sex differences in memory decline in a population-based cohort spanning 20-76 years. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7710. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86397-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Survival Analysis a Self-Learning Text. Springer; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersen PK, Abildstrom SZ, Rosthøj S. Competing risks as a multistate model. Stat Methods Med Res. 2002;11(2):203-215. doi: 10.1191/0962280202sm281ra [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515-526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Survival Analysis. Vol 3. Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greenland S, Poole C. Empirical-Bayes and semi-Bayes approaches to occupational and environmental hazard surveillance. Arch Environ Health. 1994;49(1):9-16. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1994.9934409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greenland S, Robins JM. Empirical-Bayes adjustments for multiple comparisons are sometimes useful. Epidemiology. 1991;2(4):244-251. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199107000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zotcheva E, Bergh S, Selbæk G, et al. Midlife physical activity, psychological distress, and dementia risk: the HUNT study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(2):825-833. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L. Depression as a modifiable factor to decrease the risk of dementia. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(5):e1117-e1117. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mojtabai R. Use of specialty substance abuse and mental health services in adults with substance use disorders in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78(3):345-354. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mackenzie CS, Reynolds K, Cairney J, Streiner DL, Sareen J. Disorder-specific mental health service use for mood and anxiety disorders: associations with age, sex, and psychiatric comorbidity. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(3):234-242. doi: 10.1002/da.20911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kessing LV, Andersen PK. Does the risk of developing dementia increase with the number of episodes in patients with depressive disorder and in patients with bipolar disorder? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(12):1662-1666. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.031773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greenberg MS, Tanev K, Marin MF, Pitman RK. Stress, PTSD, and dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3)(suppl):S155-S165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gradus JL, Horváth-Puhó E, Lash TL, et al. Stress disorders and dementia in the Danish population. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(3):493-499. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seignourel PJ, Kunik ME, Snow L, Wilson N, Stanley M. Anxiety in dementia: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(7):1071-1082. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cipriani G, Borin G, Vedovello M, Di Fiorino A, Nuti A. Sociopathic behavior and dementia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113(2):111-115. doi: 10.1007/s13760-012-0161-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, Munafò MR. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):3-13. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mathew AR, Hogarth L, Leventhal AM, Cook JW, Hitsman B. Cigarette smoking and depression comorbidity: systematic review and proposed theoretical model. Addiction. 2017;112(3):401-412. doi: 10.1111/add.13604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Salim A, O’Kearney R. Smoking as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(4):367-378. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lange P, Tøttenborg SS, Sorknæs AD, et al. Danish Register of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:673-678. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S99489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Camacho TC, Roberts RE, Lazarus NB, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD. Physical activity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134(2):220-231. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Najar J, Östling S, Gudmundsson P, et al. Cognitive and physical activity and dementia: a 44-year longitudinal population study of women. Neurology. 2019;92(12):e1322-e1330. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ravaglia G, Forti P, Lucicesare A, et al. Physical activity and dementia risk in the elderly: findings from a prospective Italian study. Neurology. 2008;70(19 Pt 2):1786-1794. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000296276.50595.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morris MC. Nutrition and risk of dementia: overview and methodological issues. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1367(1):31-37. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marx W, Lane M, Hockey M, et al. Diet and depression: exploring the biological mechanisms of action. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(1):134-150. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00925-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perry BL, McConnell WR, Coleman ME, Roth AR, Peng S, Apostolova LG. Why the cognitive “fountain of youth” may be upstream: pathways to dementia risk and resilience through social connectedness. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(5):934-941. doi: 10.1002/alz.12443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Santini ZI, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S, Mason C, Haro JM. The association between social relationships and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:53-65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Study Timeline and Length of Follow-Up for Study Subjects and Data Sources, 1977-2018

eTable 1. Diagnostic Codes From the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth and Tenth Revisions (ICD-8 and ICD-10)

eTable 2. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Codes for Prescribed Antidepressants

eFigure 2. Flow Chart Depicting Exclusion Criteria for Patients Diagnosed with Depressive Disorders (Pane A) and Members of the Comparison Cohort (Panel B), 1977-2018

eFigure 3. Complementary Log-Log Plot for Proportional Hazards Assumption

eTable 3. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Treatment With Prescribed Antidepressant

eTable 4. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Frequency of Inpatient Encounters Among Those With a Depression Diagnosis

eTable 5. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Baseline Health Characteristics

eTable 6. Semi-Bayes Adjustment for Multiple Estimation

eTable 7. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia within Alternative Age Strata

eTable 8. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia for Inpatient and Outpatient Depression Diagnoses

eTable 9. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Year at Depression Diagnosis

eTable 10. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia by Dementia Subtypes

eTable 11. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia Restricted to Those Age ≥45 at Baseline

eTable 12. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia Including the First Year of Follow-Up

eTable 13. Adjusted HR for Depression and Dementia Without Censoring of Comparison Cohort Members

Data Sharing Statement