Abstract

The lack and maldistribution of public health workers are critical issues for primary health care. This study aimed to assess the availability of public health workers at primary health care and to identify its related factors. We use secondary data from health facility research in 2019. Overall, 68.79% of primary health care in rural areas and 71.33% of primary health care in remote areas have the number of public health workers fit standards, but urban areas only reach 46.82%. The public health worker from health promotion and behavior concentration is more dominantly fulfilled than others. Accreditation status is a determinant factor of the availability of public health workers in urban and rural primary health care. Especially remote primary health care, it is not only affected by accreditation status but also service capability. The government needs to review the policy of public health worker recruitment at primary health care to support the fulfillment of public health workers. Public health education should start considering career development programs to ensure that all graduates from various concentrations can be absorbed into the workforce.

Key words: Human resources for health, public health workforce, Workforce policy, Career planning, Public health graduates

Introduction

Indonesia is facing a human resources crisis at all levels of health care facilities. In particular, primary health care still experiences a lack of health workers. Of 9699 primary health care, over 90% have doctors, nurses, and midwives, but 24% of primary health care are without public health workers. 1 Although human resources for health at primary health care increased in 2011-2017, inequality is getting wider. Provinces with the highest proportion of primary health care without public health workers are DKI Jakarta (80.6%), Papua (49.2%), East Java (45%), West Papua (38.7%), Maluku (37.4%), and North Sulawesi (36%).2

The availability of public health workers is a vital part of primary health care. In addition to providing health services, primary health care is also a center for encouraging health-oriented development and public empowerment.3 The public health worker has a significant role in carrying out this function by promoting public health.4 If a public health worker is adequate, a disease prevention and control program will be potentially more optimal. Furthermore, countries with better primary health care systems were also proven to have lower mortality rates and better health care outcomes. 5

Fulfillment of human resources for health is one of the priority development agendas in the health sector. Efforts to improve human resources for health contribute to health system performance.6 Various efforts to fulfill human resources for health in primary health care are the regional non-permanent employee scheme, Nusantara Sehat program, and contract/honorary recruitment.1 The restructuring of the Ministry of Health with the establishment of the Directorate General of Health Workers is also evidence of the government’s seriousness to fulfill human resources for health through the formulation of policies in the health workforce consist of planning needs, utilization, training, qualification improvement, competency evaluation, career development, protection, and well-being.7

However, fulfilling public health worker needs is not convenient due to several unnoticed factors. It includes the low career development system in public health education that makes graduates are confused when looking for a workplace, limited recruitment leading to non-optimal labor absorption, and misperception of the workplace so that prospective graduates are more interested in working in cities than rural and remote areas. Previous research also mentioned similar things that the factors contributing to the availability of public health workers come from the university education system,8 government policies regarding the provision of the workforce,9 and the preferences of prospective graduates.10

In the last ten years, the issues of human resources for health have become a highlight in health research in Indonesia. Most of the existing research studied medical workers such as doctors, nurses, midwives, dentists, and specialists,11 while research about public health worker is still rare. Therefore, this research explored the availability of public health workers (the number and types) and identified the determinants in the expectation of strengthening the function of primary health care in carrying out public health services.

Materials and Methods

Data source

The data were collected from the Indonesia health facility survey in 2019, a continuous survey conducted since 2011 to map the availability of health facilities and the availability of human resources for health, and performance index. The health facility survey in 2019 involved all primary health care throughout 33 provinces in Indonesia. The survey was conducted in primary health care by collecting information about profiles, information systems, organization and planning, rooms, health efforts, human resources, supporting facilities, disease diagnosis, treatment capabilities, laboratory capabilities, pharmacy, financing, capitation and non-capitation, and provider satisfaction.

Characteristics of primary health care

Information from the primary health care was collected using a questionnaire that included questions about service capacity, regional category, accreditation status, accreditation predicate, and financial management system.

Measurement of the number of public health worker

The number of public health workers in primary health care was measured from accumulating public health workers in seven concentrations consisting of epidemiology, health promotion and behavior, occupational health, health policy and administration, biostatistics and population, reproductive health and family planning, and health informatics. The availability of public health workers is grouped based on the region according to the Regulation of Minister of Health Number 75 of 2014.3 Primary health care in urban areas must have at least two public health workers, while primary health care in rural and remote areas must have at least one public health worker.

Data analysis

This research only analyzed samples with complete information about the characteristics of the primary health care and public health workers and is free from outliers. Data were analyzed in two stages of univariate and bivariate analysis. The univariate analysis applied simple frequency distribution to describe the characteristics of primary health care and the availability of public health workers. Meanwhile, the bivariate analysis used the Chi-Square test to assess the relationship between the characteristics of primary health care and the availability of public health workers based on the area of primary health care. Data were further analyzed using Stata software version 12.0 for Windows.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The National Institute of Health Research and Development, Ministry of Health, Indonesia (Reference Number LB.02.01/2/KE.011/2019). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to questionnaire administration.

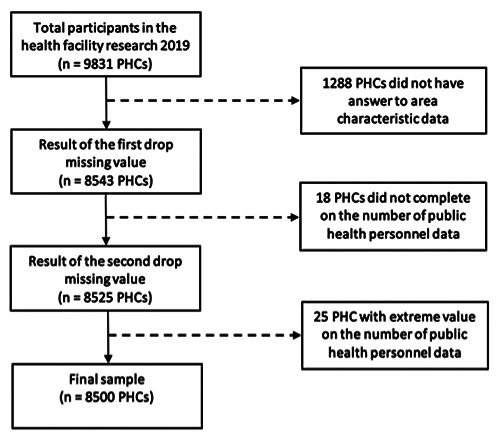

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing selection of study sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of primary health care.

| Variables | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Service capacity | ||

| Inpatient | 3680 | 43.29 |

| Without inpatient | 4820 | 56.71 |

| Region category | ||

| Urban | 2424 | 28.52 |

| Rural | 4133 | 48.62 |

| Remote | 1943 | 22.86 |

| Accreditation status | ||

| Accredited | 6728 | 79.15 |

| Not accredited | 1772 | 20.85 |

| Accreditation predicate | ||

| Perfect | 43 | 0.64 |

| Prime | 730 | 10.85 |

| Medium | 3777 | 56.14 |

| Basic | 2178 | 32.37 |

| Financial management system | ||

| Regional public service agency | 2721 | 32.01 |

| Non-regional public service agency | 5779 | 67.99 |

| Availability of public health worker in urban areas | ||

| Fulfilled | 1135 | 46.82 |

| Not fulfilled | 1289 | 53.18 |

| Availability of public health worker in rural areas | ||

| Fulfilled | 2843 | 68.79 |

| Not fulfilled | 1290 | 31.21 |

| Availability of public health worker in remote areas | ||

| Fulfilled | 1386 | 71.33 |

| Not fulfilled | 557 | 28.67 |

Results

There is 9831 primary health care recorded in the health facility survey 2019. Among these primary health care, 1331 (13.5%) are excluded from further analysis because they did not have complete information about the characteristics of the primary health care and the number of public health workers as well as there were extreme values in the number of public health worker (more than ten workers for each type of public health worker). Therefore, the analysis was carried out based on 8500 primary health care (see Figure 1). Table 1 describes the characteristics of 8500 primary health care and the availability of public health workers based on the region. Just over 56% of primary health care do not have inpatient services. The region of primary health care is very heterogeneous (28.52% urban areas, 48.62% rural areas, 22.86% remote areas). Most of the primary health care (79.15%) has been accredited with various predicates (0.64% perfect, 10.85% prime, 56.14% medium, 32.37% basic). Furthermore, almost two-thirds of primary health care (67.99%) use a non-regional public service agency financial management system. In relation to the availability of public health workers, the vast majority of the primary health care in rural areas (68.79%) and remote areas (71.33%) have public health workers that fit the Ministry of Health standards. Meanwhile, primary health care in urban areas with qualified public health workers is almost the same as primary health care with unfulfilled health workers, with only a 6.36% difference.

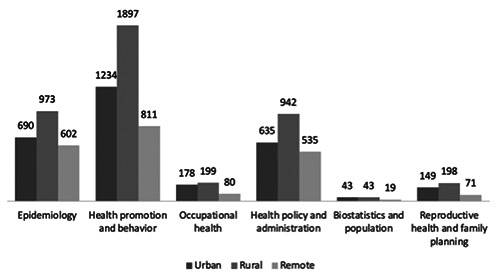

Figure 2 shows the inequity of public health workers in primary health care. Based on concentration, the highest type of public health workers in primary health care is health promotion and behavior. The number of primary health care which has public health workers from health policy and administration and epidemiology is not too different. The number of primary health care with public health workers from occupational health, reproductive health and family planning is almost similar. Meanwhile, the lowest type of public health workers in primary health care is biostatistics and population. By region, the primary health care in rural areas has more public health workers in all concentrations. On the other hand, primary health care in remote areas has fewer public health workers in each concentration compared to others.

Table 2 summarizes an analysis of the relationship between the characteristics of primary health care and the availability of public health workers in primary health care. Availability of public health workers was significantly associated with accreditation status. This means that accredited primary health care has a higher probability of fulfilled public health workers than unaccredited primary health care. However, service capacity, accreditation predicate, and financial management system are not related to the availability of public health workers in urban areas. The rural primary health care finding is similar to urban primary health care due to accreditation status also has a significant relationship with the availability of public health workers. This means that accredited primary health care has a higher probability of having fulfilled public health workers than unaccredited primary health care. Meanwhile, the service capacity, accreditation predicate, and financial management status are not related to the availability of public health workers at primary health care in rural areas. There is a significant relationship between service capacity and accreditation status with the availability of public health workers at primary health care in remote areas. This means that primary health care which has inpatient services has a higher probability of having fulfilled public health workers than primary health care without inpatient services. On the other hand, accredited primary health care also has a higher probability of having their public health workers fulfilled than unaccredited primary health care. Meanwhile, accreditation predicate and financial management status are not associated with the availability of public health workers at primary health care in remote areas.

Figure 2.

Mapping of public health workers by concentration and region.

Table 2.

The availability of public health workers in primary health care with associated factors.

| Variables | Urban Areas (n=2424) | Rural Areas (n=4133) | Remote Areas (n=1943) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fulfilled | Not Fulfilled | p-value | Fulfilled | Not Fulfilled | p-value | Fulfilled | Not Fulfilled | p-value | |

| Service capacity | |||||||||

| Inpatient | 359 (49.31) | 369 (50.69) | 0.108 | 1402 (70.24) | 594 (29.76) | 0.051 | 734 (76.78) | 222 (23.22) | 0.000 |

| Without inpatient | 776 (45.75) | 920 (54.25) | 1441 (67.43) | 696 (32.57) | 652 (66.06) | 335 (33.94) | |||

| Accreditation status | |||||||||

| Accredited | 1067(49.13) | 1105 (50.87) | 0.000 | 2440 (69.91) | 1050 (30.09) | 0.000 | 812 (76.17) | 254 (23.83) | 0.000 |

| Not accredited | 68 (26.98) | 184 (73.02) | 403 (62.67) | 240 (37.33) | 574 (65.45) | 303 (34.55) | |||

| Accreditation predicate | |||||||||

| Perfect | 14 (60.87) | 9 (39.13) | 0.334 | 14 (77.78) | 4 (22.22) | 0.357 | 2 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.496 |

| Prime | 164 (50.62) | 160 (49.38) | 257 (68.17) | 120 (31.83) | 20 (68.97) | 9 (31.03) | |||

| Medium | 588 (47.65) | 646 (52.35) | 1405 (69.21) | 625 (30.79) | 385 (75.05) | 128 (24.95) | |||

| Basic | 301 (50.93) | 290 (49.07) | 764 (71.74) | 301 (28.26) | 405 (77.59) | 117 (22.41) | |||

| Financial management system | |||||||||

| Regional public service agency | 461 (46.15) | 538 (53.85) | 0.576 | 1019 (70.03) | 436 (29.97) | 0.202 | 194 (72.66) | 73 (27.34) | 0.606 |

| Non-regional public service agency | 674 (47.30) | 751 (52.7) | 1824 (68.11) | 854 (31.89) | 1192 (71.12) | 484 (28.88) | |||

Discussion

This study shows that there were primary health care whose public health workers have not met the needs yet, but the number is not more than primary health care whose public health workers were already by workforce standards. The situation indicates that the shortage of human resources for health in Indonesia not only in medical workers but also in public health workers. The National Planning and Development Agency reported that the shortage issue of human resources for health in primary health care occurred in the workers implementing public health services such as public health workers, environmental health workers, and nutritionists.12 The shortage of public health workers in primary health care is assumed to occur after the moratorium policy on health workers other than doctors, midwives, and nurses.1 This study also finds that primary health care in rural and remote areas had more public health workers than primary health care in urban areas. The high absence of public health workers in primary health care in urban areas occurred because the primary health care at the sub-village level was included in the survey calculations.

Law Number 36 of 2014 about health workers mentions five types of public health workers, epidemiology, health promotion and behavior, occupational health, health policy and administration, biostatistics and population, reproductive health and family planning.13 However, not all these types of public health workers are available in primary health care. This study revealed that health promotion and behavioral staff were more fulfilled than other types of public health workers. The new policy about primary health care in the Regulation of Ministry of Health Number 43 of 2019 specifically explains that the standard for public health workers is to have at least health promotion and behavior.14 Other types of public health workers are not always available at primary health care. Compared to other countries, the types of public health workers who are not fulfilled include public health nurses, epidemiologists, healthcare educators, and administrators. 15 Other studies also showed the most prominent absence of public health workers in environmental health, epidemiology, and public health nutrition.16

This study finds a significant relationship between the accreditation status of primary health care and the availability of public health workers. Primary health care that carries out accreditation must be motivated to fulfill the human resources for health needs to obtain a satisfying predicate. The workforce is one component of primary health care facility management that becomes the standard for assessing the accreditation of primary health care.17 Primary health care which does not have adequate human resources for health will likely not carry out accreditation. There are various obstacles encountered in implementing accreditation, including the shortage of human resources for health.18 This study also finds a significant relationship between the service capacity and the availability of public health workers. The complexity of health services in the health facilities makes the need for human resources for health is increasing.

This study interprets that the availability of public health workers in primary health care is only concentrated in certain types. This condition should be a concern for the university as a production unit for prospective workers. Public health education needs to design a career development system by considering the needs of each graduate user institution and mapping the workplace of graduates based on their concentration. In addition, to help graduates for postgraduate studies, public health education also plays a role in preparing graduates to enter public health broader employment destinations.19 The public health education curriculum is designed to develop the skills of graduates for early career professionals. 20 This study also shows that government policies in providing a workforce at primary health care tend to be limited so that the availability of public health workers has not been fulfilled. The government needs to review the workforce recruitment strategy to encourage the fulfillment of public health workers in primary health care. Previous research predicting a “labor crisis” in public health emphasized the use of recruitment strategies to avoid potential negative impacts on public health and population health systems.21

Conclusions

This study concludes on three main findings, including that not all primary health care has public health workers according to workforce standards, there are differences in the availability of public health workers by type, and there is the relationship between the characteristics of primary health care including the accreditation status and service capacity with the availability of public health workers. These findings also encourage public health education to design student career development programs to ensure that all graduates from various concentrations can be absorbed into the workforce in graduate user institutions. Furthermore, the government is also expected to study the policy on the recruitment of health worker, especially in public health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank The National Institute of Health Research and Development, Ministry of Health, Indonesia, for the approval to use data from the health facility research in 2019. The research received funding from the Faculty of Sport Science, Universitas Negeri Malang.

References

- 1.Harahap NP. Kajian sektor kesehatan: sumber daya manusia kesehatan. Jakarta: Direktorat Kesehatan dan Gizi Masyarakat, Kedeputian Pembangunan Manusia, Masyarakat, dan Kebudayaan, Kementerian Perencanaan dan Pengembangan Nasional Republik Indonesia; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan. Laporan riset ketenagaan di bidang kesehatan (Risnakes) tahun 2017: Puskesmas. Jakarta: Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 75 Tahun 2014 tentang Puskesmas. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tao D, Evashwick CJ, Grivna M, Harrison R. Educating the public health workforce: a scoping review. Front Public Heal. 2018;6:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, Wulu J, Regan J, Politzer R. The relationship between primary care, income inequality, and mortality in US States, 1980-1995. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(5):412-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Djibuti M, Gotsadze G, Mataradze G, Menabde G. Human resources for health challenges of public health system reform in Georgia. Hum Resour Health. 2008;6(8):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peraturan Presiden Republik Indonesia Nomor Tahun 2021 tentang Kementerian Kesehatan. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming ML, Parker E, Gould T, Service M. Educating the public health workforce: issues and challenges. Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 2009;6(8):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haughton B, George A. The public health nutrition workforce and its future challenges: the US experience. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(8):782-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vahabi A, Vahabi B, Khateri A, Mirzaei M, Ahmadian M. The perspective of public health students of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences regarding field of study and future career and its related factors in 2014. Sci J Nursing, Midwifery Paramed Fac. 2016;1(3):33-45. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budijanto D, Astuti D. Tingkat kecukupan tenaga kesehatan strategis Puskesmas di Indonesia (analisis implementasi Permenkes No. 75 Tahun 2014). Bul Penelit Sist Kesehat. 2015;18(75):179-86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harahap N. Akselerasi pemenuhan sumber daya manusia kesehatan. Jakarta: Kementerian Perencanaan dan Pengembangan Nasional Republik Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 36 Tahun 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 43 Tahun 2019 tentang Pusat Kesehatan Masyarakat. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenstock L, Silver GB, Helsing K, Evashwick C, Katz R, Klag M, et al. On linkages: confronting the public health workforce crisis: ASPH statement on the public health workforce. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(May-June):395-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilliard TM, Boulton ML. Public health workforce research in review: a 25-year retrospective. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5 Suppl. 1):S17-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 46 Tahun 2015 tentang Akreditasi Puskesmas Klinik Pratama Tempat Praktik Mandiri Dokter dan Tempat Praktik Mandiri Dokter Gigi. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Effendi DE, Ardani I, Nugroho AP, Samosir JV. Stakeholders’ perspectives of factors that enable primary health center accreditation in eastern Indonesia. Ann Trop Med Public Heal. 2021;24(01):1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macleod F, Perry I. Career paths for graduates from an undergraduate public health programme in Ireland. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28(Suppl. 4):183. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson-Hurwitz DC, Buchthal OV. Using deliberative pedagogy as a tool for critical thinking and career preparation among undergraduate public health students. Front Public Heal. 2019;7:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Draper DA, Hurley RE, Lauer JD. Public health workforce shortages imperil nation’s health. Maryland, Center for Studying Health System Change; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]