Abstract

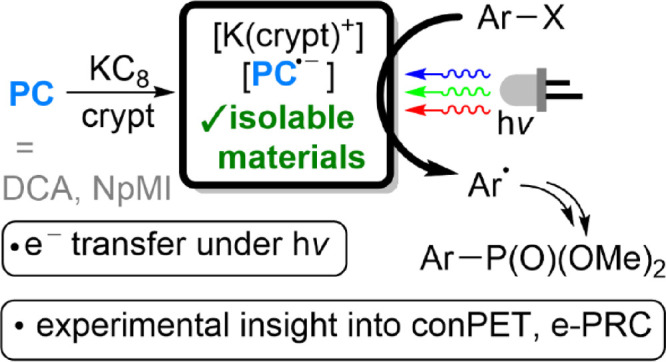

Photoredox catalysis (PRC) has gained enormous and wide-ranging interest in recent years but has also been subject to significant mechanistic uncertainty, even controversy. To provide a method by which the missing understanding can begin to be filled in, we demonstrate herein that it is possible to isolate as authentic materials the one-electron reduction products of representative PRC catalysts (PCs). Specifically, KC8 reduction of both 9,10-dicyanoanthracene and a naphthalene monoamide derivative in the presence of a cryptand provides convenient access to the corresponding [K(crypt)+][PC·–] salts as clean materials that can be fully characterized by techniques including EPR and XRD. Because PC·– states are key intermediates in PRC reactions, such isolation allows for highly controlled study of these anions’ specific reactivity and hence their mechanistic roles. As a demonstration of this principle, we show that these salts can be used to conveniently interrogate the mechanisms of recent, high-profile “conPET” and “e-PRC” reactions, which are currently the subject of both significant interest and acute controversy. Using very simple experiments, we are able to provide striking insights into these reactions’ underlying mechanisms and to observe surprising levels of hidden complexity that would otherwise have been very challenging to identify and that emphasize the care and control that are needed when interrogating and interpreting PRC mechanisms. These studies provide a foundation for the study of a far broader range of questions around conPET, e-PRC, and other PRC reaction mechanisms in the future, using the same strategy of PC·– isolation.

Keywords: conPET, e-PRC, photocatalysis, photochemistry, photoredox, radical ions

Introduction

The rapid emergence, adoption, and expansion of photoredox catalysis (PRC) has been one of the more dramatic and significant developments in synthetic chemistry of the past decade.1,2 By using light (typically visible light) to selectively photoexcite a redox-active dye, PRC allows synthetic chemists to access versatile and reactive radical intermediates in a remarkably controllable manner. This has allowed practitioners to develop a myriad of new reactions, often involving the transformation of relatively ‘unactivated’ substrates, and PRC methods have rapidly become a mainstay of modern chemistry research.3,4

At the heart of PRC lies a relatively simple mechanistic rationale, in which photoexcitation of a suitable photocatalyst dye (PC) leads to a markedly more oxidizing (or reducing) excited state (*PC), which can engage in single-electron transfer (SET) with a target substrate (Scheme 1a). The resulting radical PC·– (or PC·+) can then engage in a second SET step to close the catalytic cycle, having in the process generated one or more reactive substrate-derived radicals, sub·–/sub·+, which can then engage in subsequent, reaction-specific elementary steps to afford the final reaction products.

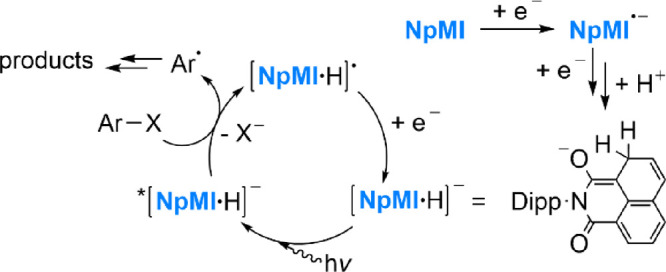

Scheme 1. Generic Mechanisms for PRC Reactions.

(a) A generic mechanism for ‘standard’ PRC reactions proceeding via reductive quenching of photocatalyst excited state *PC (analogous oxidative quenching is also possible, forming PC·+ in place of PC·–); (b) generic mechanisms proposed for reductive conPET (i) and e-PRC (ii) reactions; and (c) isolation of key PC·– intermediates allowing for direct experimental interrogation of these mechanisms, as described herein. In panels (a) and (b), sub1/sub2 may be separate reaction substrates or intermediates derived from one another.

Unfortunately, the “deceptive simplicity”5 of this mechanistic picture obscures the fact that in practice, PRC mechanisms are often highly complex and challenging to study, especially for steps that occur ‘downstream’ of initial *PC quenching or involve short (or ultrashort) excited state lifetimes. As a result, they are often poorly understood, and inspection of the recent literature reveals common, explicit concerns among practitioners about the negative impact of this limitation on current PRC research.6 On those occasions where specific PRC mechanisms have been studied in detail, the results have typically served to highlight unexpected levels of complexity in the reaction mechanisms in question.5−7

There is thus a clear need for new methods by which the mechanisms of PRC catalysis might conveniently be interrogated. One such solution would be the careful isolation of the key intermediates involved in PRC reactivity, to allow for study of their elementary reactivity under fully controlled conditions (a strategy that has been foundational to the understanding of many other homogeneous catalytic reactions). Notably, their catalytic versatility and outer-sphere reactivity mean that for any single PC, there typically exist many different reactions, all believed to proceed via exactly the same PC·– (or PC·+) state. Isolation of just one such PC·– would thus provide a tool compound to study many distinct PRC transformations. However, such a strategy has seldom been pursued until now, and its feasibility has thus remained unproven and uncertain.4d,8

An excellent example of the confusion that can surround PRC mechanisms is found in the related areas of “conPET” (consecutive photoinduced electron transfer) and “electrochemically-mediated PRC” (e-PRC).9,10 These are adaptations of the ‘standard’ PRC mechanism that have both attracted particularly intense interest in recent years as they allow the catalysts employed to generate extremely reducing (or oxidizing)11 potentials that exceed those normally accessible in visible light PRC (though there is no strict limit, potentials beyond ca. ±2 V vs SCE are commonly considered difficult to achieve for standard PRC).12 This allows for the facile activation of challenging, inert substrates, such as reduction of electron-neutral (or even electron-rich) aryl bromides and chlorides.13 To achieve this, reductive conPET mechanisms are proposed to proceed via initial formation of PC·– from PC in the same manner as for ‘standard’ PRC (Scheme 1b, i). However, once formed, this reductant is then suggested to undergo a second photoexcitation, thus increasing its reducing power considerably. Substrate reduction then occurs via SET from this excited state, *PC·–. A very similar rationale is proposed in e-PRC reactions, although in this case the ground-state PC·– is formed through direct, electrochemical reduction of ground-state PC (Scheme 1b, ii). Thus, while conPET and e-PRC differ in the number of photons required in their catalytic cycles, and often in their downstream redox chemistry,9d the same excited state (*PC·–) is invoked as a crucial catalytic intermediate in both cases. However, the viability of the key electron transfer step from these intermediates has attracted significant controversy. A more detailed discussion of this point can be found below; however, in essence, it has been argued that the doublet excited states *PC·– are simply too short-lived to engage in the proposed, presumably diffusion-limited, intermolecular SET.

Unfortunately, direct experimental interrogation of this step and of the photochemistry of relevant PC·– in general has typically proven extremely challenging and relied on advanced and specialized spectroscopic techniques that are not easily accessible for most practitioners in the field (cf. bench-stable, closed-shell PCs, which can typically be studied by accessible, established techniques such as fluorescence quenching). These studies have in turn been reliant on photo- or electrochemical methods to generate the air-sensitive PC·– intermediates in situ.14 These methods increase practical complexity, while also significantly complicating subsequent analysis and interpretation due to the inevitable presence of species other than PC·– in the analyte mixture (e.g., electrolytes, stoichiometric reductant-derived byproducts, etc.), whose impact is often uncertain and must be rigorously accounted for. Formation of side products is also possible and can easily be overlooked, leading to erroneous conclusions (vide infra).

ConPET and e-PRC thus provide excellent illustrative examples of where the study of isolated PC·– would be highly valuable. With this in mind, we report herein that relevant PC·– salts containing non-interacting counter-cations can be isolated as authentic, ‘bottleable’ materials (Scheme 1c).15 This allows for direct study of their chemical and photochemical behavior, providing insights of clear relevance to their conPET and e-PRC reactivity. The results highlight significant complexities that lie hidden in these reactions and challenge arguments that have previously been made about their mechanisms.

Results and Discussion

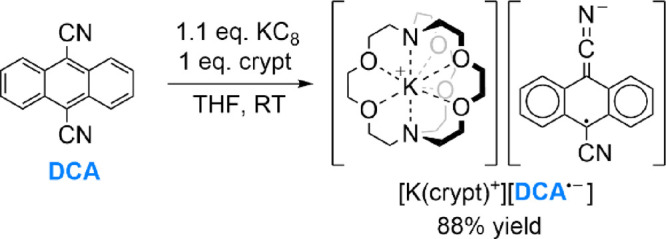

Synthesis and Characterization of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–]

Although many different PC are available, for this initial study, it was decided to target reduction of the relatively simple organic photocatalysts DCA (9,10-dicyanoanthracene) and NpMI (a naphthalene monoimide derivative), which were chosen based on the prominent roles they have played in the development of conPET and e-PRC as well as the controversy and confusion that continue to surround it (vide infra).16 The reduction potentials for both should also be chemically accessible (ca. −1.0 V, −1.3 V vs SCE for DCA, NpMI, respectively).9d,16b

Thus, a suspension of DCA in THF was treated under an inert atmosphere with an equimolar quantity of 2,2,2-cryptand (crypt) and 1.1. equiv of KC8, which led to immediate formation of a deep purple solution. Filtration to remove excess KC8 and the graphite byproduct and removal of solvent in vacuo followed by washing with PhMe and hexane yielded a dark solid, which could be identified as the target product [K(crypt)+][DCA·–], in very good yield (88%; Scheme 2).17

Scheme 2. Synthesis of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–].

Only one of several possible resonance forms of the DCA·– anion is shown.

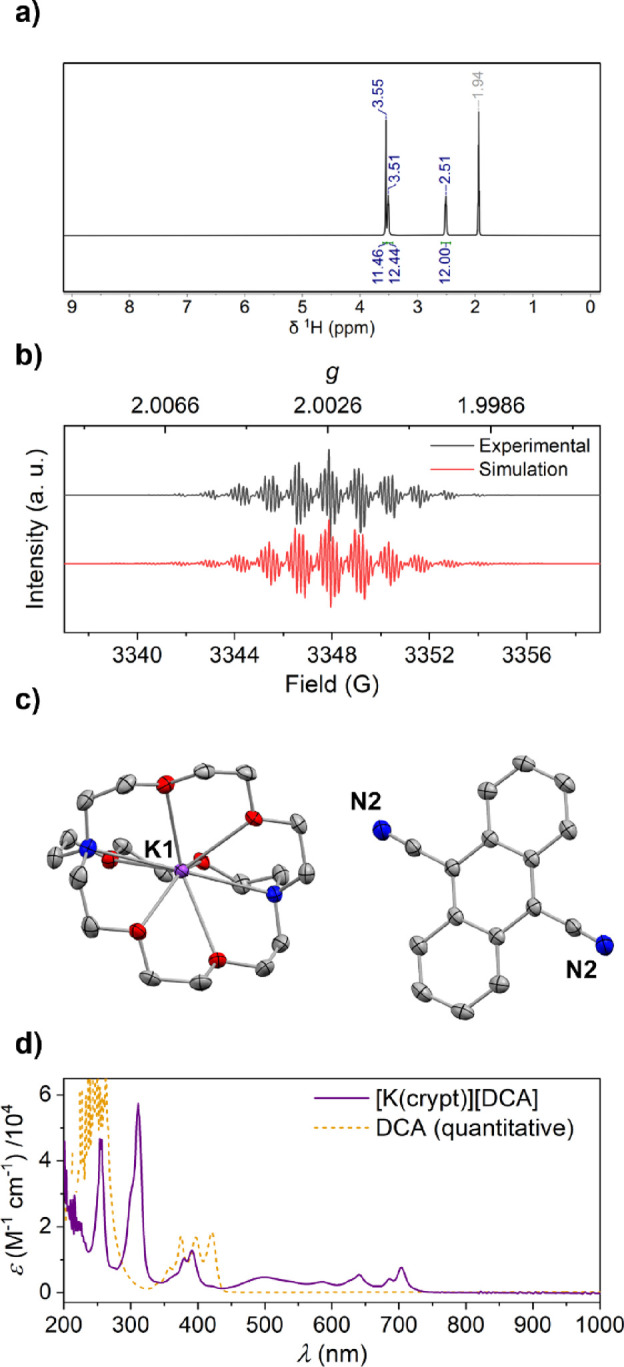

The identity of the product was confirmed by a combination of spectroscopic and crystallographic analysis (vide infra) and, crucially, its compositional purity could be confirmed by elemental analysis. As expected, room-temperature NMR analysis of the product showed only the 1H and 13C resonances expected for the cryptand moiety, with no signals detected for the paramagnetic DCA·– anion in the ±500 ppm range (Figure 1a). The corresponding X-band EPR spectrum showed a clear signal at the frequency expected for an organic radical (g = 2.00256) and clear hyperfine coupling to two equivalent N atoms and two sets of four equivalent H atoms, fully in line with the expected delocalization of spin density across the entire DCA moiety (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Spectroscopic and crystallographic characterization of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] (additional details in the SI): (a) 1H NMR spectrum (CD3CN (δ = 1.94 ppm), RT); (b) X-band EPR spectrum (4:1 PhMe/THF, 109 μM, RT; simulated as g = 2.00256, 4 × A(1H) = 3.904 MHz, 4 × A(1H) = 2.969 MHz, 2 × A(14N) = 0.4307 MHz, 15% A(13C) = 20.631 MHz); (c) single-crystal XRD structure; thermal ellipsoids shown at 50%; H atoms omitted for clarity and only one of two inequivalent DCA moieties shown (asymmetric unit contains 1 × [K(crypt)+] and 2 × 0.5[DCA·–]); C atoms in gray, N in blue, O in red, K in purple; (d) UV–vis spectrum (MeCN, 544 μM, 1 mm path, RT).

Further conclusive proof of the product structure was provided by XRD analysis of single crystals grown by slow diffusion of Et2O into a THF solution. The structure is depicted in Figure 1c and reveals two crystallographically independent half DCA·– moieties per asymmetric unit, whose charges are balanced by a single K(crypt)+ site (for full details, see Section 5.1 of the SI). Both DCA·– moieties are fully planar and show no close interactions with the K+ cation, which as expected is fully sequestered by the cryptand. Comparison of the DCA·– bond lengths with those reported for neutral DCA reveal a pattern of bond contractions and elongations consistent with the nodal structure of the SOMO,18 in line with previous predictions (Figure S60).19 The UV–vis spectrum of [K(crypt)][DCA·–] is shown in Figure 1d and is consistent with several previous in situ spectra assigned to DCA·–.20

Synthesis and Characterization of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–]

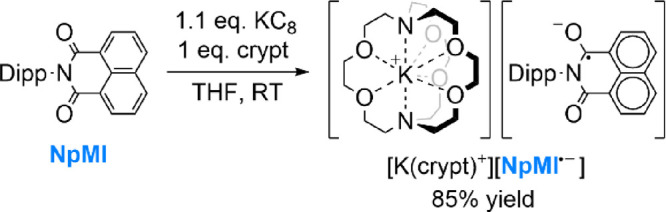

Replacing DCA with NpMI in the previous synthesis led to an essentially equivalent outcome. In this case, a deep green solid was isolated, again in excellent yield, which could be identified as the desired salt [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] through a similar combination of spectroscopic, crystallographic, and elemental analysis (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–].

Only one of several possible resonance forms of the NpMI·– anion is shown. Dipp = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl.

As for [K(crypt)+][DCA·–], 1H and 13C NMR analysis of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] showed the expected resonances for the cryptand ligand (at 3.55, 3.51, 2.51 ppm). However, in this case, a pair of broad 1H features were also observable at 1.39 and 1.07 ppm, attributed to the iPr moieties of the NpMI·– Dipp group (Figure 2a; Dipp = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl). This assignment is supported by their relative integral intensities and suggests localization of radical character on the electron-deficient naphthalene monoimide fragment rather than on the Dipp group, as expected. This interpretation is supported by the corresponding X-band EPR spectrum, which shows hyperfine coupling to one N atom and three sets of two equivalent H atoms (Figure 2b). This is consistent with previous EPR investigations of in situ electrogenerated NpMI·–, although these provided much less well-defined, pseudo-quintet signals.16a

Figure 2.

Spectroscopic and crystallographic characterization of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] (additional details in the SI): (a) 1H NMR spectrum (CD3CN (δ = 1.94 ppm), RT); (b) X-band EPR spectrum (THF, 199 μM, RT; simulated as g = 2.00371, 2 × A(1H) = 15.833 MHz, 2 × A(1H) = 13.357 MHz, 2 × A(1H) = 1.833 MHz, A(14N) = 3.760 MHz); (c) single-crystal XRD structure of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–]·(THF); thermal ellipsoids shown at 50%; H atoms, THF molecule and disorder in NpMI moiety omitted for clarity; C atoms in gray, N in blue, O in red, K in purple; (d) UV–vis spectrum (MeCN, 504 μM, 1 mm path, RT).

The crystal structure of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] reveals a single K(crypt)+ cation and a single NpMI·– environment (Figure 2c). The naphthalene fragment of the latter is disordered, and so detailed bond lengths will not be discussed. However, the naphthalene monoimide moiety is clearly planar, with no evidence of significant, residual, out-of-plane electron density that might indicate C(sp3) sites (cf. [NpMI·H–]; ref (21)). The Dipp moiety is twisted almost perpendicular to this plane, in line with the lack of spin delocalization into this part of the anion.

The UV–vis spectrum of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] is shown in Figure 2d and confirms the spectroscopic signature of the radical anion, being consistent with previous in situ observations.16a,21,22

Prior State of the Art Regarding conPET and e-PRC Mechanisms

For context, it should be noted that the mechanistic controversies surrounding synthetic applications of conPET trace back to the origins of the field. In 2014, König et al. reported reduction of aryl halides using a perylene diimide derivative as the proposed conPET catalyst,23 but the mechanism was challenged in 2017 by Cozzi et al. based on lifetime arguments (vide supra).24 In contrast, the mechanism has been supported by a more recent report from Zhang et al., although the authors emphasized the need for very high substrate concentrations.25

Similarly, the initial independent reports of synthetic e-PRC in 2020 by Wickens et al. (using NpMI)26 and Lambert et al. (using DCA)19 have also attracted considerable comment (note that DCA has been used as a photocatalyst for several proposed conPET reactions, as well as e-PRC).27 In their original report, Lambert et al. pointed to a published excited state lifetime for *DCA·– of 13.5 ns, which was expected to be long enough to allow for diffusive encounters with substrate molecules and subsequent SET (though highly concentration-dependent, it has been suggested as a rule of thumb that this usually requires lifetimes >1 ns).28 Unfortunately, reinspection of the prior literature revealed that this value, which was based on fluorescence quenching of in situ electrochemically generated solutions of DCA·–, had subsequently been found to be erroneous.29 In fact, DCA·– had been reported in a later study to be non-fluorescent, with the previously observed emission being attributed to minor formation of another species due to the presence of trace O2 during in situ electrolysis. The authors of the latter report even went so far as to state that “because the excited-state lifetimes of typical radical ions are short, they are poor candidates for use as photosensitizers”.30 This confusion neatly highlights the dangers of relying on in situ methods for PC·– generation.

Subsequent attempts in the 1990s to clarify the lifetime of *DCA·– also relied on in situ methods and gave diverging estimates.31 However, a very recent study by Vauthey et al. has indicated a value as low as a few picoseconds.32 Such short lifetimes are commonly observed for simple organic doublet anions,33,34 and with this in mind, Nocera et al. have recently argued that NpMI-catalyzed reactions proposed to proceed via e-PRC may instead be the result of in situ transformation of NpMI/NpMI·– into the Meisenheimer-type structure [NpMI·H–] (Scheme 4), which as a closed-shell species has a much longer excited state lifetime (20 ns) and is therefore suggested to be the true active catalyst.21 The authors imply that similar processes may account for other observations previously attributed to conPET/e-PRC. Others, however, have argued that intermolecular SET from *PC·– could be feasible despite their short lifetimes under certain circumstances (for example due to static and non-stationary quenching regimes that are not diffusion-limited)8,13g,32 and such steps continue to be invoked in reports of new PRC reactions, albeit often accompanied by an acknowledgement of some mechanistic uncertainty.35

Scheme 4. Alternative Mechanism for Photoreduction of Challenging Substrates Mediated by NpMI as (Pre-)catalyst Proposed by Nocera et al(21).

Dipp = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl.

Clearly, the question of *[PC·–] involvement in conPET and e-PRC mechanisms is both highly complex and rather fraught, and a comprehensive resolution of the controversy is beyond the scope of a single manuscript (vide infra). Nevertheless, in order to highlight and emphasize the experimental opportunities made available by isolation of authentic [K(crypt)+][PC·–], we present below some initial experiments toward this goal that provide important new insights while also highlighting new directions for future work.

Photoreactivity of Isolated [K(crypt)+][DCA·–]

To begin, solutions of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] in MeCN were simply irradiated under various LED wavelengths in the absence of any substrate. After 16 h, no appreciable change was observed either by UV–vis or NMR spectroscopy at any of the wavelengths studied, suggesting that any subsequent photoreactivity cannot easily be attributed to photodecomposition products (see SI, Section 3.1.1).

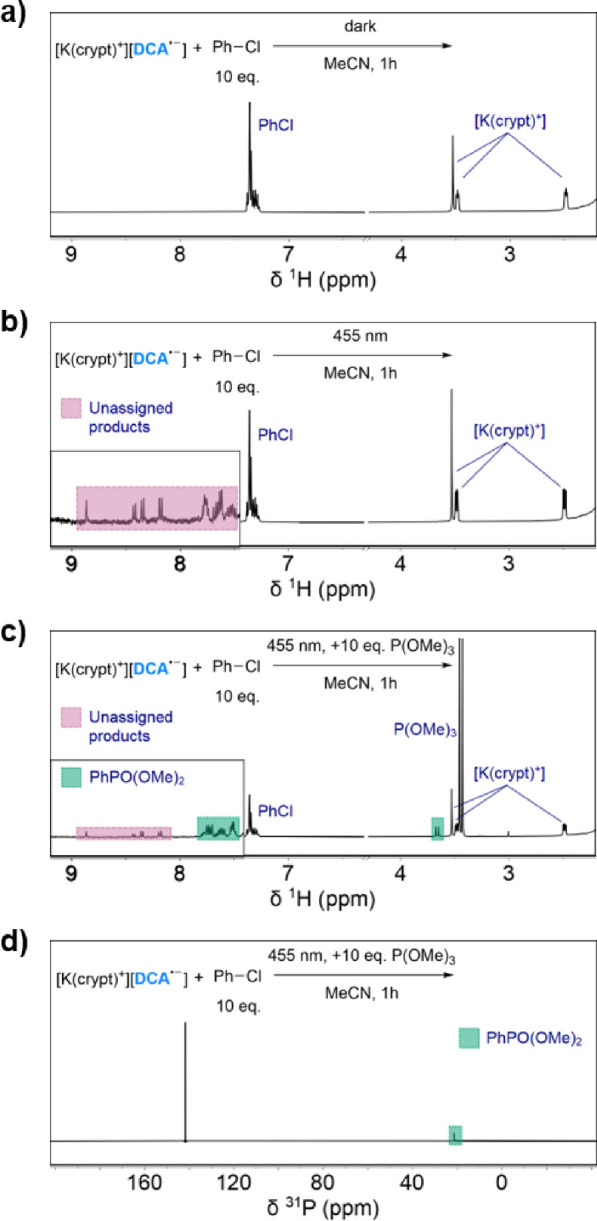

Following this confirmation of its photostability, [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] was then combined with an excess of a simple yet challenging model substrate, PhCl, at concentrations representative of those that have been used in previous catalytic reactions (5 mM in [K(crypt)+][DCA·–], 50 mM in PhCl).36 As expected, no reaction was observed in the dark (Figure 3a), either by eye or by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Figure 3.

1H NMR spectra for the reaction of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] with PhCl (10 equiv) in MeCN for 1 h (a) in the dark or (b) under 455 nm LED irradiation; and (c) 1H and (d) 31P{1H} NMR spectra for the latter reaction performed in the presence of P(OMe)3 (10 equiv). Certain ranges are inset and magnified for clarity. Additional spectra can be found in Section 3 of the SI.

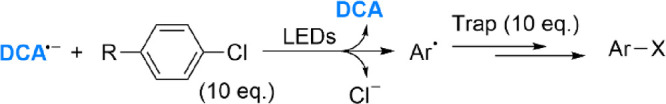

The reaction was then repeated under blue (455 nm) LED irradiation. Failure to observe reactivity in this experiment would unambiguously preclude the conPET and e-PRC mechanisms previously proposed for DCA at this wavelength. However, upon irradiation, clear reactivity was observed, with a loss of the characteristic purple color of DCA·– and the formation of new signals in the 1H NMR spectrum (Figure 3b). Moreover, formation of PhH (and trace Ph2) as downstream Ph·-derived products was clearly confirmed by GC–MS analysis (see SI, Section 3.4.1), consistent with reduction of PhCl to Ph·. However, 1H NMR analysis of the reaction also revealed a large number of other new resonances in the aromatic region, which is presumably attributable to attack of initially formed Ph· radicals on the remaining DCA·– anions (which would be expected to outcompete homocoupling due to low Ph· concentrations). Such reactions are known for similar cyanoarene motifs and typically involve displacement of cyanide (for further discussion, see Section 3.5.1 of the SI).37

To provide a neater outcome, the reaction between [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] and PhCl was repeated in the presence of a radical trap, with P(OMe)3 being chosen to provide a convenient 31P NMR handle. Simple alkyl phosphites are known to function as effective traps for aryl radicals generated during PRC (including proposed conPET), generating phosphonate esters.27b,38 In this case, a much cleaner outcome was observed, with a single set of major new signals in the 1H spectrum and only one significant new peak in the 31P{1H} spectrum, at 21.2 ppm (Figure 3c,d). These signals correspond to PhP(O)(OMe)2 (confirmed by spiking the mixture with authentic material), which is the expected final product of Ph· radical trapping by P(OMe)3. Control reactions showed no significant reaction between [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] and P(OMe)3 in the absence of PhCl (either under irradiation or in the dark). These observations are therefore again fully consistent with net reduction of PhCl by DCA·– to generate Ph· (Table 1). Quantitative 31P{1H} integration relative to a subsequently added internal standard showed 66% conversion to PhP(O)(OMe)2 relative to the amount of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] added, after 1 h (Table 1, entry 1).39

Table 1. Conversion of ArCl to ArX via Reduction to Ar· Using [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] and Subsequent Trappinga.

| entry | trapb | t/h | R | λ/nm | conv./%c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | H | 455 | 66 |

| 2 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | H | 530 | 0 |

| 3 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | H | 630 | 0 |

| 4 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | H | 730 | 0 |

| 5 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | CO2Me | 455 | 74 |

| 6 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | CO2Me | 530 | 10 |

| 7 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | CO2Me | 630 | 7 |

| 8 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | CO2Me | 730 | 8 |

| 9 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | OMe | 455 | 95d |

| 10 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | OMe | 530 | 0 |

| 11 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | OMe | 630 | 0 |

| 12 | P(OMe)3 | 1 | OMe | 730 | 0 |

| 13 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | H | 455 | 174e |

| 14 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | H | 530 | 3 |

| 15 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | H | 630 | 0 |

| 16 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | H | 730 | 0 |

| 17 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 455 | 247e |

| 18 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 530 | 82 |

| 19 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 630 | 77 |

| 20 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 730 | 37 |

| 21 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | OMe | 455 | 141d,e |

| 22 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | OMe | 530 | 0 |

| 23 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | OMe | 630 | 0 |

| 24 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | OMe | 730 | 0 |

| 25 | B2pin2 | 16 | CO2Me | 455 | 58 |

| 26 | P(OEt)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 455 | 257 |

Reaction between ArCl (10 equiv, 50 mM), trap (10 equiv, 50 mM), and [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] (1 equiv, 5 mM) in MeCN under LED irradiation (peak wavelength λ).

For P(OMe)3, P(OEt)3, and B2pin2 as traps, X = P(O)(OMe)2, P(O)(OEt)2, and Bpin, respectively.

Conversion to ArX measured by quantitative 31P{1H} (X = P(O)(OMe)2, P(O)(OEt)2), or 1H (X = Bpin) NMR spectroscopy relative to a subsequently added internal standard (Ph3PO or mesitylene), relative to the initial amount of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] added.

An additional, unidentified signal was also observed at δ(31P) = 17.3 ppm, integrating to 40% (entry 9), 51% (entry 21).

Average of three experiments (see Section 3.4 of the SI).

The reaction between [K(crypt)+][DCA·–], PhCl, and P(OMe)3 was also investigated under irradiation at other wavelengths. While in their e-PRC report, Lambert et al. used blue LEDs,19 others have previously argued that green light rather than blue is essential for productive photoexcitation of DCA·–,27a,27b while the Wenger group has recently used red light.27c However, in our hands, neither green (530 nm) nor red (630 nm) LED irradiation yielded measurable product formation under otherwise equivalent conditions (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). Nevertheless, when PhCl was replaced with a more electron-deficient and hence easier to reduce substrate bearing a 4-CO2Me group, the reaction proceeded at both wavelengths (albeit considerably more slowly at both wavelengths than at 455 nm; Table 1, entries 5–7) and even at 730 nm, which is at the limit of the DCA·– absorption window (Table 1, entry 8).

All three previously employed wavelengths are thus clearly competent for the aryl chloride reduction step, but with strong substrate dependence. Moreover, higher reactivity is consistently observed at 455 nm (Table 1, cf. entry 5 and entries 6–8), despite seemingly poor absorption by DCA·– around this wavelength (cf.Figure 1d, and vide infra for additional discussion). Indeed, under 455 nm LEDs, reduction could even be achieved for the more electron-rich, 4-OMe-substituted substrate 4-chloroanisole (Table 1, entries 9–12). No obvious correlation is apparent between the conversions observed at this wavelength and the electron richness/deficiency of these substrates (Table 1, cf. entries 1, 5, and 9).

As expected, increased reaction times allowed for significant improvements in substrate conversion (Table 1, entries 13–24). To our surprise, however, sufficiently extended irradiation times were consistently found to lead to conversions greater than 100% with respect to [K(crypt)+][DCA·–], particularly at 455 nm. This suggests that DCA·– is capable not only of mediating the reaction between ArCl and P(OMe)3 upon photoirradiation, but actually of catalyzing it, with modest turnover, even in the absence of an external reductant. Even higher turnovers could be observed by using lower [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] concentrations (for details, see Section 3.4.4 of the SI).

These unexpected observations further emphasize the hidden complexity that can exist in even seemingly simple photoredox reactions and that would be difficult to identify in less controllable, in situ studies. They are tentatively attributed to the catalytic mechanism summarized in Scheme 5. Simple phosphites P(OR)3 are well known as effective traps for aryl radicals Ar·, which add to form P-centered phospharanyl radicals ArP(OR)3·. Transformation of these radicals into the final observed products ArP(O)(OR)2 requires formal loss of R·, and in previous PRC studies (including conPET), this has generally been proposed to occur directly via known β-fragmentation pathways, with the resulting R· then abstracting a H atom from the reaction mixture to produce RH as the stoichiometric byproduct.38,40 However, it is known that the radical PhP(OMe)3· is also a potent reductant and that intermolecular SET from PhP(OMe)3· can be fast enough to compete with β-fragmentation.41 PhP(OMe)3· is at least reducing enough to reduce the sulfonium cation TolSPh2+ (Tol = 4-tolyl) and, based on the potentials required to reduce similar sulfonium salts (e.g., ca. −1.5 V vs SCE for Ph–TT+; TT = thianthrene),42 should also be capable of reducing neutral DCA back to the radical anion DCA·– (ca. −1.0 V vs SCE),16b hence providing turnover.43 Arbuzov-type loss of MeCl via attack of chloride on concomitantly-generated PhP(OMe)3+ would then furnish the phosphonate product.44

Scheme 5. Proposed Catalytic Mechanism for the Reaction of ArCl and P(OMe)3, Mediated by [K(crypt)+][DCA·–].

To provide qualitative support for this interpretation, the highest-turnover reaction (using MeO2CC6H4Cl and blue LEDs) was repeated using B2pin2 as an alternative radical trap instead of P(OMe)3. In this case, an analogous redox-neutral coupling pathway is not available and indeed only (sub)stoichiometric formation of the ArBpin product was observed, even with the extended reaction time (Table 1, entry 25). For thoroughness, an alternative, commonly used phosphite trap, P(OEt)3 was also tested under the same conditions and again led to greater than stoichiometric conversion (Table 1, entry 26).

Photoreactivity of Isolated [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–]

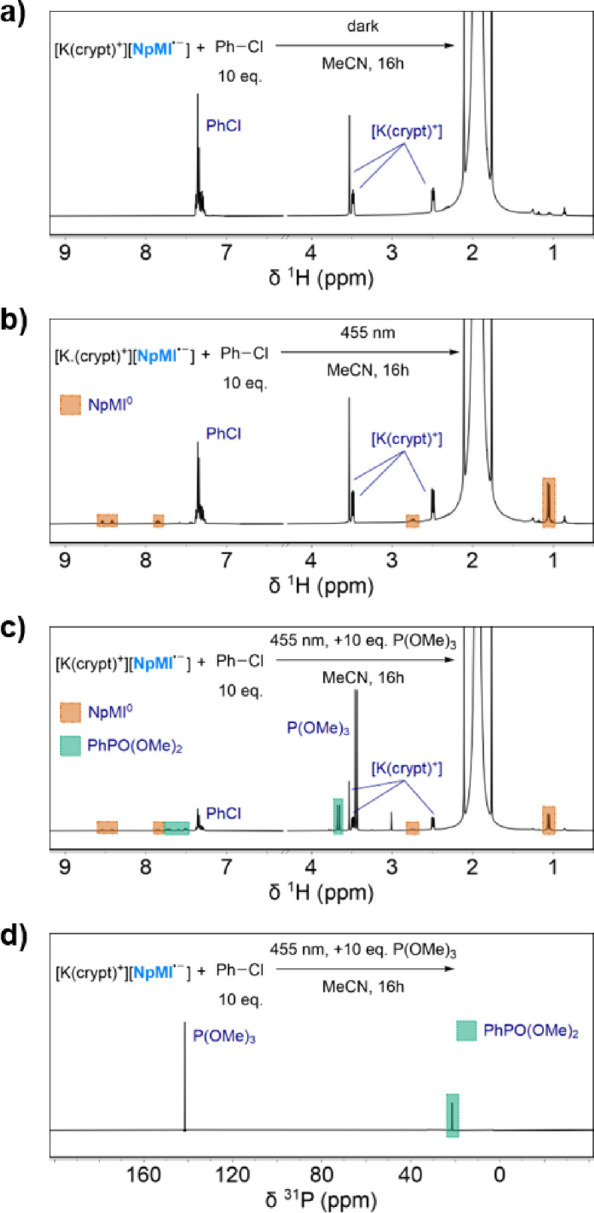

Analogous studies using [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] in place of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] yielded mostly very similar results. Again, the salt was found to be stable in the presence of PhCl in the dark (Figure 4a), as well as photostable upon irradiation at 530, 630 or 730 nm for 16 h, either alone or in the presence of P(OMe)3. However, unlike [K(crypt)+][DCA·–], the NpMI·– salt was found to decompose upon extended irradiation at 455 nm, which is the primary wavelength under which it has previously been proposed to engage in e-PRC reactivity (for full details and additional discussion, see Section 3.1.2 of the SI).26

Figure 4.

1H NMR spectra for the reaction of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] with PhCl (10 equiv) in MeCN for 16 h (a) in the dark or (b) under 455 nm LED irradiation; (c) 1H and (d) 31P{1H} NMR spectra for the latter reaction performed in the presence of P(OMe)3 (10 equiv). Additional spectra can be found in Section 3 of the SI.

Nevertheless, irradiation at this wavelength in the presence of PhCl led to clear reformation of neutral NpMI, which could be observed in the 1H NMR spectrum (Figure 4b; cf. with [K(crypt)+][DCA·–], vide supra). Similar results were also observed at 530 nm (see Section 3.5.2 of the SI). The fate of the Ph fragment could not be clearly ascertained from the same spectra (due to overlap with the much larger resonances for the remaining PhCl starting material), but GC–MS analysis again confirmed formation of PhH (see SI, Section 3.4.1). Analogous irradiation of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] in the presence of both PhCl and P(OMe)3 again led to formation of PhP(O)(OMe)2 (Figure 4c,d). As with [K(crypt)+][DCA·–], superstoichiometric amounts of product formation were achievable (Table 2).

Table 2. Conversion of ArCl to ArX via Reduction to Ar· Using [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] and Subsequent Trappinga.

| entry | trapb | t/h | R | λ/nm | conv./%c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | H | 455 | 157d |

| 2 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | H | 530 | 106 |

| 3 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | H | 630 | 4 |

| 4 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | H | 730 | 0 |

| 5 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 455 | 225d |

| 6 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 530 | 155 |

| 7 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 630 | 159 |

| 8 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 730 | 173 |

| 9 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | OMe | 455 | 195d,e |

| 10 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | OMe | 530 | 99 |

| 11 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | OMe | 630 | 0 |

| 12 | P(OMe)3 | 16 | OMe | 730 | 0 |

| 13 | B2pin2 | 16 | CO2Me | 455 | 61 |

| 14 | B2pin2 | 16 | CO2Me | 530 | 38 |

| 15 | P(OEt)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 455 | 177 |

| 16 | P(OEt)3 | 16 | CO2Me | 530 | 85 |

Reaction between ArCl (10 equiv, 50 mM), trap (10 equiv, 50 mM), and [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] (1 equiv, 5 mM) in MeCN under LED irradiation (peak wavelength λ).

For P(OMe)3, P(OEt)3, and B2pin2 as traps, X = P(O)(OMe)2, P(O)(OEt)2, and Bpin, respectively.

Conversion to ArX measured by quantitative 31P{1H} (X = P(O)(OMe)2, P(O)(OEt)2), or 1H (X = Bpin) NMR spectroscopy relative to a subsequently added internal standard (Ph3PO or mesitylene), relative to the initial amount of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–] added.

Average of three experiments (see Section 3.4 of the SI).

An additional, unidentified signal was also observed at δ(31P) = 17.3 ppm, integrating to 16%.

Despite the broad similarities, clear differences in wavelength dependence were also observed between the NpMI·– and DCA·– salts. For example, while 530 nm irradiation did not induce significant reduction of PhCl when using DCA·–, clear conversion was observed at this wavelength using NpMI·–, which is qualitatively consistent with the increased reducing power expected of the latter (Table 2, entry 2).9d Conversely, no more than a trace reaction was observed at 630 nm (Table 2, entry 3). This contrasts with the generally similar reactivity observed at 530 and 630 nm using DCA·– and may be due to relatively weak absorption by NpMI·– around this wavelength. Like with DCA·–, however, blue light was found to consistently give the highest conversions (e.g., Table 2, entries 5–8). Again, comparative reactions were performed using B2pin2 (Table 2, entries 13 and 14) and P(OEt)3 (Table 2, entries 15 and 16) as alternative radical traps, with the former only achieving stoichiometric conversions.

Discussion

The results of the above photoreactivity experiments are striking and – while the primary goal of this report is not to advocate for one specific reaction mechanism over another – it has certainly not escaped our notice that they are almost entirely consistent with the originally proposed conPET and e-PRC mechanisms and rather harder to rationalize via alternative mechanisms that do not involve SET from *PC·–. Indeed, these results present a clear challenge to the idea that such mechanisms must be inherently and fundamentally infeasible, despite recent arguments to this effect.

Nevertheless, we would also emphasize the hidden levels of inherent reaction complexity uncovered by these same experiments, which must also be considered during their interpretation. For example, the observed instability of both DCA·– and NpMI·– under certain catalytically relevant conditions (presence of Ph·, blue LEDs, respectively) has obvious potential mechanistic relevance and means that even if the originally proposed conPET and e-PRC mechanisms are viable in principle, a holistic understanding of these reactions will have to consider the potential (photo)reactivity of these decomposition products as well. Nor would the viability of conPET and e-PRC mechanisms automatically preclude other pathways, such as Nocera’s proposed Meisenheimer mechanism,21 from being kinetically competitive in certain reactions.

Similarly, although almost all of the observations made can very easily be rationalized using the original conPET/e-PRC mechanistic model, there are exceptions, such as the unexpected wavelength dependence noted above. For example, the almost ‘binary’ loss of reactivity toward PhCl for DCA·– at wavelengths other than 455 nm (see entries 1–3 in Table 1) contrasts with the relatively poor absorption by DCA·– at this wavelength. Nor can these initial results yet account for how SET is able to occur, despite the reportedly short *PC·– lifetimes.

These remaining issues can potentially be reconciled through the involvement of higher-order excited states45 and/or transient pre-assembly of PC·– and the substrate (though no such preassembly has yet been detected by steady-state spectroscopy: see Section 3.2 of the SI).16b,46,47 However, until this is confirmed, alternative mechanisms cannot quite be precluded, and a more detailed, critical discussion of several such mechanisms can be found in Section 4 of the SI.

Filling in these final puzzle pieces will require more detailed studies of the transient absorption behavior, preassembly, and decomposition of PC·–, which are beyond the scope of this initial manuscript. Fortunately though, these are all studies that will also be significantly aided and simplified by the accessibility of authentic [K(crypt)+][PC·–] as isolated materials (and efforts in these directions are already underway). On a broader note, the results reported herein provide a clear proof-of-principle for the viability of isolating PRC-relevant PC·– states of commonly employed PCs. This has the potential to be a much more general strategy for the study of PRC mechanisms and only requires equipment that is widely accessible in synthetic laboratories. However, it has seldom been pursued until now.4d,8,48 It has recently been noted of PRC mechanisms that “reaction intermediates formed following the initial PET step [from PC] are seldom monitored and [...] there still remains much to discover about the supposedly ‘dark’ reactions of photocatalytic cycles”.7e As illustrated herein, isolated PC·– represent ideal tools for the study of these missing steps. Thus, while we have focused so far on the investigation of conPET and e-PRC mechanisms, DCA in particular has also been employed as a photocatalyst for a much larger variety of ‘standard’ PRC transformations, all of which are proposed to proceed viaDCA·– as a key intermediate.49 Isolation of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] thus provides a tool compound that can be used to study these reactions as well.

Conclusions

For the first time, it has been possible to isolate radical anion salts corresponding to the one-electron reduced forms of photocatalysts that have been employed in mechanistically controversial conPET and e-PRC reactions. These can be prepared as authentic materials on a preparative scale and in good yields and their isolation allows for detailed characterization, including by techniques that have not previously been applicable such as XRD. Their availability as ‘bottleable’ compounds has allowed for convenient yet precise and controlled study of their (photo)reactivity, using relatively simple experiments. This in turn has allowed significant new insights into conPET and e-PRC reactions to rapidly be uncovered, including observations of unexpected turnover, counterintuitive wavelength dependence, and previously unreported catalyst (photo)decomposition pathways. These results provide strong, qualitative support for proposed conPET and e-PRC mechanisms, while also highlighting areas where future work is needed to reconcile certain experimental observations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the EPSRC for award of an Early Career Fellowship (EP/V056069/1), Prof. Matthew Langton for use of a UV–vis spectrometer, the Material and Chemical Characterisation Facility (MC2) at the University of Bath for technical support and assistance,50 and Prof. Robert Wolf for early support. Z.F. would like to dedicate this article to the women of Iran who are fighting for their freedom.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.3c02515.

Full experimental details for synthesis and characterization of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] and [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] including copies of NMR, EPR, and UV–vis spectra and XRD data; full experimental details for all photoreactivity studies including LED specifications and quantification of products; additional discussion of alternative photochemical mechanisms (PDF)

CIF file of [K(crypt)+][DCA·–] (CIF)

CIF file of [K(crypt)+][NpMI·–]·(THF) (CIF)

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- For some relevant reviews, see:; a Prier C. K.; Rankic D. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Romero N. A.; Nicewicz D. A. Organic Photoredox Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10075–10166. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Allen A. R.; Noten E. A.; Stephenson C. R. J. Aryl Transfer Strategies Mediated by Photoinduced Electron Transfer. Chem. Rev. 2021, 122, 2695–2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For some of the seminal early reports, see:; a Ischay M. A.; Anzovino M. E.; Du J.; Yoon T. P. Efficient Visible Light Photocatalysis of [2+2] Enone Cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12886–12887. 10.1021/ja805387f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nicewicz D. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Merging Photoredox Catalysis with Organocatalysis: The Direct Asymmetric Alkylation of Aldehydes. Science 2008, 322, 77–80. 10.1126/science.1161976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Narayanam J. M. R.; Tucker J. W.; Stephenson C. R. J. Electron-Transfer Photoredox Catalysis: Development of a Tin-Free Reductive Dehalogenation Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 8756–8757. 10.1021/ja9033582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzo L.; Pagire S. K.; Reiser O.; König B. Visible-Light Photocatalysis: Does It Make a Difference in Organic Synthesis?. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10034–10072. 10.1002/anie.201709766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRC is primarily employed in the context of organic synthesis. However, for some emerging applications of PRC in inorganic synthesis, see, for example:; a Wang D.; Loose F.; Chirik P. J.; Knowles R. R. N–H Bond Formation in a Manganese(V) Nitride Yields Ammonia by Light-Driven Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4795–4799. 10.1021/jacs.8b12957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lennert U.; Arockiam P. B.; Streitferdt V.; Scott D. J.; Rödl C.; Gschwind R. M.; Wolf R. Direct catalytic transformation of white phosphorus into arylphosphines and phosphonium salts. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 1101–1106. 10.1038/s41929-019-0378-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Johansen C. M.; Boyd E. A.; Peters J. C. Catalytic transfer hydrogenation of N2 to NH3 via a photoredox catalysis strategy. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eade3510 10.1126/sciadv.ade3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ashida Y.; Onozuka Y.; Arashiba K.; Konomi A.; Tanaka H.; Kuriyama S.; Yamazaki Y.; Yoshizawa K.; Nishibayashi Y. Catalytic nitrogen fixation using visible light energy. Nat. Comm.un. 2022, 13, 7263. 10.1038/s41467-022-34984-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Davey S. G. Deceptive simplicity. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 444. 10.1038/s41570-021-00305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Stevenson B. G.; Spielvogel E. H.; Loiaconi E. A.; Wambua V. M.; Nakhamiyayev R. V.; Swierk J. R. Mechanistic Investigations of an α-Aminoarylation Photoredox Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 8878–8885. 10.1021/jacs.1c03693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For example:; a Marchini M.; Bergamini G.; Cozzi P. G.; Ceroni P.; Balzani V. Photoredox Catalysis: The Need to Elucidate the Photochemical Mechanism. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12820–12821. 10.1002/anie.201706217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ghosh I.; Bardagi J. I.; König B. Reply to “Photoredox Catalysis: The Need to Elucidate the Photochemical Mechanism.”. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12822–12824. 10.1002/anie.201707594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Seegerer A.; Nitschke P.; Gschwind R. M. Combined In Situ Illumination-NMR-UV/Vis Spectroscopy: A New Mechanistic Tool in Photochemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7493–7497. 10.1002/anie.201801250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Buzzetti L.; Crisenza G. E. M.; Melchiorre P. Mechanistic Studies in Photocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3730–3747. 10.1002/anie.201809984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Coles M. S.; Beves J. E.; Moore E. G. A Photophysical Study of Sensitization-Initiated Electron Transfer: Insights into the Mechanism of Photoredox Activity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9522–9526. 10.1002/anie.201916359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Sun R.; Qin Y.; Nocera D. G. General Paradigm in Photoredox Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Allows for Light-Free Access to Reactivity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9527–9533. 10.1002/anie.201916398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Noël T.; Zysman-Colman E. The promise and pitfalls of photocatalysis for organic synthesis. Chem. Catal. 2022, 468–476. 10.1016/j.checat.2021.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For selected further examples, see:; a Donabauer K.; Maity M.; Berger A. L.; Huff G. S.; Crespi S.; König B. Photocatalytic carbanion generation – benzylation of aliphatic aldehydes to secondary alcohols. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 5162–5166. 10.1039/C9SC01356C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Connell T. U.; Fraser C. L.; Czyz M. L.; Smith Z. M.; Hayne D. J.; Doeven E. H.; Agugiaro J.; Wilson D. J. D.; Adcock J. L.; Scully A. D.; Gómez D. E.; Barnett N. W.; Polyzos A.; Francis P. S. The Tandem Photoredox Catalysis Mechanism of [Ir(ppy)2(dtb-bpy)]+ Enabling Access to Energy Demanding Organic Substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17646–17658. 10.1021/jacs.9b07370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Goliszewska K.; Rybicka-Jasińska K.; Clark J. A.; Vullev V. I.; Gryko D. Photoredox Catalysis: The Reaction Mechanism Can Adjust to Electronic Properties of a Catalyst. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5920–5927. 10.1021/acscatal.0c00200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Till N. A.; Tian L.; Dong Z.; Scholes G. D.; MacMillan D. W. C. Mechanistic Analysis of Metallaphotoredox C–N Coupling: Photocatalysis Initiates and Perpetuates Ni(I)/Ni(III) Coupling Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 15830–15841. 10.1021/jacs.0c05901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Connell T. U. The forgotten reagent of photoredox catalysis. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 13176–13188. 10.1039/D2DT01491B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Stevenson B. G.; Pracsak A. V.; Lee A. A.; Talbott E. D.; Fredin L. A.; Swierk J. R. Enhanced basicity of an electron donor–acceptor complex. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 2943–2945. 10.1039/D2CC05985A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Mandigma M. J. P.; Kaur J.; Barham J. P. Organophotocatalytic Mechanisms: Simplicity or Naïvety? Diverting Reactive Pathways by Modifications of Catalyst Structure, Redox States and Substrate Preassemblies. ChemCatChem 2023, e202201542 10.1002/cctc.202201542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Žurauskas J.; Domański M.; Hitzfeld P. S.; Butera V.; Scott D. J.; Rehbein J.; Kumar A.; Thyrhaug E.; Hauer J.; Barham J. P. Hole-mediated photoredox catalysis: tris(p-substituted)biarylaminium radical cations as tunable, precomplexing and potent photooxidants Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 1132–1142. 10.1039/D0QO01609H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews relevant to these areas that include historical developments, see:; a Barham J. P.; König B. Synthetic Photoelectrochemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11732–11747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Glaser F.; Kerzig C.; Wenger O. S. Multi-Photon Excitation in Photoredox Catalysis: Concepts, Applications. Methods. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10266–10284. 10.1002/anie.201915762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Castellanos-Soriano J.; Herrera-Luna J. C.; Díaz Díaz D.; Consuelo Jiménez M.; Pérez-Ruiz P. Recent applications of biphotonic processes in organic synthesis. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 1709–1716. 10.1039/D0QO00466A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Wu S.; Kaur J.; Karl T. A.; Tian X.; Barham J. P. Synthetic Molecular Photoelectrochemistry: New Frontiers in Synthetic Applications, Mechanistic Insights and Scalability. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202107811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Huang H.; Steiniger A.; Lambert T. H. Electrophotocatalysis: Combining Light and Electricity to Catalyze Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 12567–12583. 10.1021/jacs.2c01914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Markushyna Y.; Savateev A. Light as a Tool in Organic Photocatalysis: Multi-Photon Excitation and Chromoselective Reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202200026 10.1002/ejoc.202200026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Note that while we favor the term “e-PRC” alternatives such as “electron-primed PRC” can also be found in the literature, alongside more ambiguous terminology. A detailed discussion of the relevant nomenclature can be found in ref (9a).

- For oxidizing examples, see ref (8) and:; a Christensen J. A.; Phelan B. T.; Chaudhuri S.; Acharya A.; Batista V. S.; Wasielewski M. R. Phenothiazine Radical Cation Excited States as Super-oxidants for Energy-Demanding Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5290–5299. 10.1021/jacs.8b01778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rombach D.; Wagenknecht H.-A. Photoredox Catalytic Activation of Sulfur Hexafluoride for Pentafluorosulfanylation of α-Methyl- and α-Phenyl Styrene. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 2955–2961. 10.1002/cctc.201800501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Rombach D.; Wagenknecht H.-A. Photoredox Catalytic α-Alkoxypentafluorosulfanylation of α-Methyl- and α-Phenylstyrene Using SF6. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 300–303. 10.1002/anie.201910830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Huang H.; Strater Z. M.; Rauch M.; Shee J.; Sisto T. J.; Nuckolls C.; Lambert T. H. Electrophotocatalysis with a Trisaminocyclopropenium Radical Dication. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 13318–13322. 10.1002/anie.201906381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Targos K.; Williams O. P.; Wickens Z. K. Unveiling Potent Photooxidation Behavior of Catalytic Photoreductants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 4125–4132. 10.1021/jacs.1c00399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Li P.; Deetz A. M.; Hu J.; Meyer G. J.; Hu K. Chloride Oxidation by One- or Two-Photon Excitation of N-Phenylphenothiazine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17604–17610. 10.1021/jacs.2c07107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Huang H.; Lambert T. H. Regiodivergent Electrophotocatalytic Aminooxygenation of Aryl Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 18803–18809. 10.1021/jacs.2c08951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Shen T.; Li Y.-L.; Ye K.-Y.; Lambert T. H. Electrophotocatalytic oxygenation of multiple adjacent C–H bonds. Nature 2023, 614, 275–280. 10.1038/s41586-022-05608-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Li P.; Liu R.; Zhao Z.; Niu F.; Hu K. Lignin C–C bond cleavage induced by consecutive two-photon excitation of a metal-free photocatalyst. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 1777–1780. 10.1039/D2CC06730G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Steiniger K. A.; Lambert T. H. Olefination of carbonyls with alkenes enabled by electrophotocatalytic generation of distonic radical cations. Sci. Adv. 2023, 10.1126/sciadv.adg3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For example, see; De Vos D.; Gadde K.; Maes B. Emerging Activation Modes and Techniques in Visible-Light-Photocatalyzed Organic Synthesis. Synthesis 2023, 55, 193–231. 10.1055/a-1946-0512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For reducing examples other than those based on perylene diimide, dicyanoanthracene, or naphthalene monoimide scaffolds (which are referenced separately, below), see:; a Kerzig C.; Guo X.; Wenger O. S. Unexpected Hydrated Electron Source for Preparative Visible-Light Driven Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2122–2127. 10.1021/jacs.8b12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Brandl F.; Bergwinkl S.; Allacher C.; Dick B. Consecutive Photoinduced Electron Transfer (conPET): The Mechanism of the Photocatalyst Rhodamine 6G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 7946–7954. 10.1002/chem.201905167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cole J. P.; Chen D.-F.; Kudisch M.; Pearson R. M.; Lim C.-H.; Miyake G. M. Organocatalyzed Birch Reduction Driven by Visible Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 13573–13581. 10.1021/jacs.0c05899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Giedyk M.; Narobe R.; Weiß S.; Touraud D.; Kunz W.; König B. Photocatalytic activation of alkyl chlorides by assembly-promoted single electron transfer in microheterogeneous solutions. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 40–47. [Google Scholar]; e MacKenzie I. A.; Wang L.; Onuska N. P. R.; Williams O. F.; Begam K.; Moran A. M.; Dunietz B. D.; Nicewicz D. A. Discovery and characterization of an acridine radical photoreductant. Nature 2020, 580, 76–80. 10.1038/s41586-020-2131-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Santos M. S.; Cybularczyk-Cecotka M.; König B.; Giedyk M. Minisci C–H Alkylation of Heteroarenes Enabled by Dual Photoredox/Bromide Catalysis in Micellar Solutions. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15323–15329. 10.1002/chem.202002320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Caby S.; Bouchet L. M.; Argüello J. E.; Rossi R. A.; Bardagi J. I. Excitation of Radical Anions of Naphthalene Diimides in Consecutive- and Electro-Photocatalysis. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 3001–3009. 10.1002/cctc.202100359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Chernowsky C. P.; Chmiel A. F.; Wickens Z. K. Electrochemical Activation of Diverse Conventional Photoredox Catalysts Induces Potent Photoreductant Activity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 21418–21425. 10.1002/anie.202107169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Chmiel A. F.; Williams O. P.; Chernowsky C. P.; Yeung C. S.; Wickens Z. K. Non-innocent Radical Ion Intermediates in Photoredox Catalysis: Parallel Reduction Modes Enable Coupling of Diverse Aryl Chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10882–10889. 10.1021/jacs.1c05988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Ju T.; Zhou Y.-Q.; Cao K.-G.; Fu Q.; Ye J.-H.; Sun G.-Q.; Liu X.-F.; Chen L.; Liao L.-L.; Yu D.-G. Dicarboxylation of alkenes, allenes and (hetero)arenes with CO2 via visible-light photoredox catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 304–311. 10.1038/s41929-021-00594-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; k Xu J.; Cao J.; Wu X.; Wang H.; Yang X.; Tang X.; Toh R. W.; Zhou R.; Yeow E. K. L.; Wu J. Unveiling Extreme Photoreduction Potentials of Donor–Acceptor Cyanoarenes to Access Aryl Radicals from Aryl Chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13266–13273. 10.1021/jacs.1c05994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Fang Y.; Liu T.; Chen L.; Chao D. Exploiting consecutive photoinduced electron transfer (ConPET) in CO2 photoreduction. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7972–7975. 10.1039/D2CC02356C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Foja R.; Walter A.; Jandl C.; Thyrhaug E.; Hauer J.; Storch G. Reduced Molecular Flavins as Single-Electron Reductants after Photoexcitation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 4721–4726. 10.1021/jacs.1c13285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Ilic A.; Schwarz J.; Johnson C.; de Groot L. H. M.; Kaufhold S.; Lomoth R.; Wärnmark K. Photoredox catalysis via consecutive 2LMCT- and 3MLCT-excitation of an Fe(III/II)–N-heterocyclic carbene complex. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 9165–9175. 10.1039/D2SC02122F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o Jeong D. Y.; Lee D. S.; Lee H. L.; Nah S.; Lee J. Y.; Cho E. J.; You Y. Evidence and Governing Factors of the Radical-Ion Photoredox Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 6047–6059. 10.1021/acscatal.2c00763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; p Zott M. D.; Canstraight V. M.; Peters J. C. Mechanism of a Luminescent Dicopper System That Facilitates Electrophotochemical Coupling of Benzyl Chlorides via a Strongly Reducing Excited State. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 10781–10786. 10.1021/acscatal.2c03215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; q Pavlovska T.; Lesný D. K.; Hoskovcová I.; Archipowa N.; Kutta R. J.; Cibulka R. Tuning Deazaflavins Towards Highly Potent Reducing Photocatalysts Guided by Mechanistic Understanding – Enhancement of the Key Step by the Internal Heavy Atom Effect. Chem. – Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202200768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; r Soika J.; McLaughlin C.; Neveselý T.; Daniliuc C. G.; Molloy J. J.; Gilmour R. Organophotocatalytic N–O Bond Cleavage of Weinreb Amides: Mechanism-Guided Evolution of a PET to ConPET Platform. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 10047–10056. 10.1021/acscatal.2c02991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; s Song L.; Wang W.; Yue J.-P.; Jiang Y.-X.; Wei M.-K.; Zhang H.-P.; Yan S.-C.; Liao L.-L.; Yu D.-G. Visible-light photocatalytic di- and hydro-carboxylation of unactivated alkenes with CO2. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 832–838. 10.1038/s41929-022-00841-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; t Venditto N. J.; Liang Y. S.; El Mokadem R. K.; Nicewicz D. A. Ketone–Olefin Coupling of Aliphatic and Aromatic Carbonyls Catalyzed by Excited-State Acridine Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11888–11896. 10.1021/jacs.2c04822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; u Caby S.; Oliva L. M.; Bardagi J. I. Unravelling the Effect of Water Addition in Consecutive Photocatalysis with Naphthalene Diimide. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 711–716. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c02172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; v Kwon Y.; Lee J.; Noh Y.; Kim D.; Lee Y.; Yu C.; Roldao J. C.; Feng S.; Gierschner J.; Wannemacher R.; Kwon M. S. Formation and degradation of strongly reducing cyanoarene-based radical anions towards efficient radical anion-mediated photoredox catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 92. 10.1038/s41467-022-35774-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; w Chen L.; Qu Q.; Ran C.-K.; Wang W.; Zhang W.; He Y.; Liao L.-L.; Ye J.-H.; Yu D.-G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202217918 10.1002/anie.202217918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; x Wan X.; Wang D.; Huang H.; Mao G.-J.; Deng G.-J. Radical-mediated photoredox hydroarylation with thiosulfonate. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 2767–2770. 10.1039/D2CC05948G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Or, more occasionally, in situ reduction by purely chemical means. For example, see refs (4b, 13e).

- Inert, weakly coordinating cations were chosen to minimize any counterion effects, which can have a measurable impact on photoredox reactivity. For example, see:; a Farney E. P.; Chapman S. J.; Swords W. B.; Torelli M. D.; Hamers R. J.; Yoon T. P. Discovery and Elucidation of Counteranion Dependence in Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6385–6391. 10.1021/jacs.9b01885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Earley J. D.; Zieleniewska A. H.; Ripberger H.; Shin N. Y.; Lazorski M. S.; Mast Z. J.; Sayre H. J.; McCusker J. K.; Scholes G. D.; Knowles R. R.; Reid O. G.; Rumbles G. Ion-pair reorganization regulates reactivity in photoredox catalysts. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 746–753. 10.1038/s41557-022-00911-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See also:; c Rohe S.; Morris A. O.; McCallum T.; Barriault L. Hydrogen Atom Transfer Reactions via Photoredox Catalyzed Chlorine Atom Generation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15664–15669. 10.1002/anie.201810187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In addition to the ‘parent’ DCA and NpMI structures, other derivatives based upon the same scaffolds have also been investigated in PRC contexts, including e-PRC. For example, see:; a Tian X.; Karl T. A.; Reiter S.; Yakubov S.; de Vivie-Riedle R.; König B.; Barham J. P. Electro-mediated PhotoRedox Catalysis for Selective C(sp3)–O Cleavages of Phosphinated Alcohols to Carbanions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 20817–20825. 10.1002/anie.202105895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mandigma M. J. P.; Žurauskas J.; MacGregor C. I.; Edwards L. J.; Shahin A.; d’Heureuse L.; Yip P.; Birch D. J. S.; Gruber T.; Heilmann J.; John M. P.; Barham J. P. An organophotocatalytic late-stage N–CH3 oxidation of trialkylamines to N-formamides with O2 in continuous flow. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 1912–1924. 10.1039/D1SC05840A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stable radical anions have been reported and isolated for some other, more electron-deficient cyanoarenes, though not in the context of photocatalysis. For example, see; Kumar Y.; Kumar S.; Mandal K.; Mukhopadhyay P. Isolation of Tetracyano-Naphthalenediimide and Its Stable Planar Radical Anion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16318–16322. 10.1002/anie.201807836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano L.; Karothu D. P.; Schramm S.; Ahmed E.; Rezgui R.; Barber T. J.; Famulari A.; Naumov P. Dual-Mode Light Transduction through a Plastically Bendable Organic Crystal as an Optical Waveguide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 17254–17258. 10.1002/anie.201810514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Kim H.; Lambert T. H.; Lin S. Reductive Electrophotocatalysis: Merging Electricity and Light To Achieve Extreme Reduction Potentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2087–2092. 10.1021/jacs.9b10678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For example:; Pedersen S. U.; Christensen T. B.; Thomasen T.; Daasbjerg K. New methods for the accurate determination of extinction and diffusion coefficients of aromatic and heteroaromatic radical anions in N,N-dimethylformamide. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1998, 454, 123–143. 10.1016/S0022-0728(98)00195-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reith A. J.; Gonzalez M. I.; Kudisch B.; Nava M.; Nocera D. G. How Radical Are “Radical” Photocatalysts? A Closed-Shell Meisenheimer Complex Is Identified as a Super-Reducing Photoreagent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14352–14359. 10.1021/jacs.1c06844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For in situ UV-vis observations of related naphthalene monoimide-derived radical anions, see:; Gosztola D.; Niemczyk M. P.; Svec W.; Lukas A. S.; Wasielewski M. R. Excited Doublet States of Electrochemically Generated Aromatic Imide and Diimide Radical Anions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 6545–6551. 10.1021/jp000706f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ghosh I.; Ghosh T.; Bardagi J. I.; König B. Reduction of aryl halides by consecutive visible light-induced electron transfer processes. Science 2014, 346, 725–728. 10.1126/science.1258232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For a more recent example proposed to proceed via e-PRC, see; b Chen Y.-J.; Deng W.-H.; Guo J.-D.; Ci R.-N.; Zhou C.; Chen B.; Li X.-B.; Guo X.-N.; Liao R.-Z.; Tung C.-H.; Wu L.-Z. Transition-Metal-Free, Site-Selective C–F Arylation of Polyfluoroarenes via Electrophotocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17261–17268. 10.1021/jacs.2c08068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchini M.; Gualandi A.; Mengozzi L.; Franchi P.; Lucarini M.; Cozzi P. G.; Balzani V.; Ceroni P. Mechanistic insights into two-photon-driven photocatalysis in organic synthesis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 20, 8071–8076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman C. J. IV; Kim S.; Zhang F.; Schanze K. S. Direct Observation of the Reduction of Aryl Halides by a Photoexcited Perylene Diimide Radical Anion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2204–2207. 10.1021/jacs.9b13027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowper N. G. W.; Chernowsky C. P.; Williams O. P.; Wickens Z. K. Potent Reductants via Electron-Primed Photoredox Catalysis: Unlocking Aryl Chlorides for Radical Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2093–2099. 10.1021/jacs.9b12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Neumeier M.; Sampedro D.; Májek M.; de la Peña O’Shea V. A.; Jacobi von Wangelin A.; Pérez-Ruiz R. Dichromatic Photocatalytic Substitutions of Aryl Halides with a Small Organic Dye. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 105–108. 10.1002/chem.201705326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Herrera-Luna J. C.; Díaz Díaz D.; Jiménez M. C.; Pérez-Ruiz R. Highly Efficient Production of Heteroarene Phosphonates by Dichromatic Photoredox Catalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 48784–48794. 10.1021/acsami.1c14497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Glaser F.; Wenger O. S. Red Light-Based Dual Photoredox Strategy Resembling the Z-Scheme of Natural Photosynthesis. JACS Au 2022, 2, 1488–1503. 10.1021/jacsau.2c00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Arias-Rotondo D. M.; McCusker J. K. The photophysics of photoredox catalysis: a roadmap for catalyst design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5803–5820. 10.1039/C6CS00526H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gadde K.; De Vos D.; Maes B. U. W. Basic Concepts and Activation Modes in Visible-Light-Photocatalyzed Organic Synthesis. Synthesis 2023, 52, 164–192. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen J.; Lund H.; Nyvad A. I.; Yamato T.; Mitchell R. H.; Dingle T. W.; Williams R. V.; Mahedevan R. Electron-transfer Fluorescence Quenching of Radical Ions. Acta Chem. Scand. 1983, 37b, 459–466. 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.37b-0459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin D. T.; Fox M. A. Excited-State Behavior of Thermally Stable Radical Ions. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 408–411. 10.1021/j100053a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Fujita M.; Ishida A.; Majima T.; Takamuku S. Lifetimes of Radical Anions of Dicyanoanthracene, Phenazine, and Anthraquinone in the Excited State from the Selective Electron-Transfer Quenching. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 5382–5387. 10.1021/jp953203w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Gumy J.-C.; Vauthey E. Investigation of the Excited-State Dynamics of Radical Ions in the Condensed Phase Using the Picosecond Transient Grating Technique. J. Phys. Chem. A 1997, 101, 8575–8580. 10.1021/jp972066v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith J. S.; Aster A.; Vauthey E. The excited-state dynamics of the radical anions of cyanoanthracenes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 24, 568–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Although, some organic doublet species can have much longer-lived excited states. For some recent examples, see:; a Imran M.; Wehrmann C. M.; Chen M. S. Open-Shell Effects on Optoelectronic Properties: Antiambipolar Charge Transport and Anti-Kasha Doublet Emission from a N-Substituted Bisphenalenyl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 38–43. 10.1021/jacs.9b10677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hudson J. M.; Hele T. J. H.; Evans E. W. Efficient light-emitting diodes from organic radicals with doublet emission. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 180901. 10.1063/5.0047636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Malpicci D.; Lucenti E.; Giannini C.; Forni A.; Botta C.; Cariati E. Prompt and Long-Lived Anti-Kasha Emission from Organic Dyes. Molecules 2021, 26, 6999. 10.3390/molecules26226999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Though less common, it is possible for PC·– to be a neutral radical rather than an anion, if the parent PC is cationic. For a conPET example, see ref (13e).

- For example, ref (27c).

- For example, cf. ca. 5 and 100 mM, respectively, in ref (19); 10 and 200 mM, respectively, in ref (27a); 5 and 50 mM, respectively, in ref (27b); 2.5 and 25 mM, respectively, in ref (27c).

- Magnion D.; Arnold D. R. Photochemical Nucleophile–Olefin Combination, Aromatic Substitution Reaction. Its Synthetic Development and Mechanistic Exploration. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi-Ashton J. A.; Clarke A. K.; Unsworth W. P.; Taylor R. J. K. Phosphoranyl Radical Fragmentation Reactions Driven by Photoredox Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 7250–7261. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Note that due to inevitable differences in photochemical setup, comparison of reaction rates with those in the literature requires extreme caution.

- Note that unlike Ar·, Me· generated in this way would not be expected to undergo net reaction with P(OMe)3 as such addition is only transient and reversible (see; Bentrude W. G. Phosphoranyl radicals - their structure, formation, and reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 1982, 15, 117–125. 10.1021/ar00076a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; ).; This is consistent with our experimental results, in which no formation of MeP(O)(OMe) was indicated in any 31P{1H} NMR spectra.

- Kampmeier J. A.; Nalli T. W. Phosphoranyl radicals as reducing agents: SRN1 chains with onium salts and neutral nucleophiles. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 943–949. 10.1021/jo00056a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Chen J.; Sang R.; Ham W.-S.; Plutschack M. B.; Berger F.; Chabbra S.; Schnegg A.; Genicot C.; Ritter T. Photoredox catalysis with aryl sulfonium salts enables site-selective late-stage fluorination. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 56–62. 10.1038/s41557-019-0353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- As an alternative, the phospharanyl radical PhP(OMe)3· could be capable of reducing the aryl chloride substrate directly. This possibility is difficult to exclude in the absence of more precise redox data regarding PhP(OMe)3· and could be favored by the higher concentration of ArCl than DCA. Nevertheless, we consider this option to be less likely due to the much less negative reduction potential of the latter, which should therefore be much easier to reduce.

- Formation of MeCl appears consistent with the resonance at δ(1H) = 3.07 ppm that can be seen in Figure 3c. See; Barany G.; Schroll A. L.; Mott A. W.; Halsrud D. A. A general strategy for elaboration of the dithiocarbonyl functionality, −(C=O)SS-: application to the synthesis of bis(chlorocarbonyl)disulfane and related derivatives of thiocarbonic acids. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 4750–4761. 10.1021/jo00172a056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For some recent reports including discussion of such higher excited states in PRC, see refs (8, 13c, 16a).

- Zeng L.; Liu T.; He C.; Shi D.; Zhang F.; Duan C. Organized Aggregation Makes Insoluble Perylene Diimide Efficient for the Reduction of Aryl Halides via Consecutive Visible Light-Induced Electron-Transfer Processes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 3958–3961. 10.1021/jacs.5b12931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- It has recently been shown that similar preassembly is possible without being detectable by steady-state spectroscopy. See:; Kumar A.; Malevich P.; Mewes L.; Wu S.; Barham J. P.; Hauer J. Transient absorption spectroscopy based on uncompressed hollow core fiber whitelight proves pre-association between a radical ion photocatalyst and substrate. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 144201. 10.1063/5.0142225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- While this manuscript was under review, Knowles and colleagues reported isolation and study of a series of reduced Ir photocatalysts. See:; Baek Y.; Reinhold A.; Tian L.; Jeffrey P. D.; Scholes G. D.; Knowles R. R. Singly Reduced Iridium Chromophores: Synthesis, Characterization and Photochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 12499–12508. 10.1021/jacs.2c13249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For example, see:; Glaser F.; Wenger O. S. Sensitizer-controlled photochemical reactivity via upconversion of red light. Chem. Sci. 2022, 14, 149–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and references therein.

- University of Bath, Material and Chemical Characterisation Facility (MC2), 10.15125/mx6j-3r54. [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.