Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between age and invasive cardiovascular hemodynamics during upright exercise among healthy adults.

BACKGROUND

The marked age-related decline in maximal exercise oxygen uptake (peak VO2) may contribute to the high burden of heart failure among older individuals and their greater severity of exertional symptoms. However, the mechanisms underlying this decline are not well understood.

METHODS

A total of 104 healthy community-dwelling volunteers age 20 to 76 years well screened for cardiovascular disease underwent exhaustive upright exercise with brachial and pulmonary artery catheters; radionuclide ventriculography; and expired gas analysis for the measurement of peak VO2, cardiac output, left ventricular stroke volume, end-diastolic volume, end-systolic volume, ejection fraction, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and arteriovenous oxygen difference.

RESULTS

Over a 5.5-decade age range, there was a 40% decline in peak VO2 due primarily to reduced peak exercise cardiac output; peak arteriovenous oxygen difference was unaffected by age. The lower age-related exercise cardiac output was related to lower peak exercise heart rate and stroke volume. Aging was also associated with lower peak exercise ejection fraction, indicating reduced inotropic reserve. Peak exercise end-diastolic volume was lower with aging despite similar left ventricular filling pressure, suggesting age-related reduced diastolic compliance limiting the use of the Frank-Starling mechanism to compensate for reduced chronotropic and inotropic reserves. These age relationships were unaffected by sex.

CONCLUSIONS

The age-related decline in exercise capacity among healthy persons is due predominantly to cardiac mechanisms, including reduced chronotropic and inotropic reserve and possibly reduced Frank-Starling reserve. Peak exercise left ventricular filling pressure and arteriovenous oxygen difference are unchanged with healthy aging.

Keywords: aging, cardiovascular hemodynamics, exercise reserve, peak exercise oxygen capacity, pulmonary capillary filling pressure

Exercise capacity, measured as peak exercise oxygen uptake (peak VO2), declines progressively with advancing age even in the absence of disease (1). However, the mechanisms underlying the age-related decline in exercise capacity in healthy individuals is not well understood. This is particularly relevant because lower levels of exercise capacity with aging are strongly associated with higher risk of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular outcomes, particularly heart failure (HF). Furthermore, exercise intolerance is the primary manifestation of chronic stable HF and is particularly severe among older patients with HF (1–4).

Previous studies (3,5–10) that have examined age relations in cardiovascular hemodynamics have been limited by small sample sizes (6,9,11,12), a lack of female participants (6,12), inclusion of symptomatic individuals or those with established disease (10,13), use of indirect and noninvasive techniques for hemodynamic assessments (3,5,7,8), and hemodynamic assessments in the supine position, which is less relevant than upright exercise to ordinary daily activity (9,10,14). The results from these studies have been conflicting. Some showed age-related declines in cardiac output and stroke volume at peak exercise (5,7), others reported a decline in cardiac output due predominantly to a decrease in heart rate with no change in stroke volume (6,9,15), and others reported a decline in peripheral oxygen extraction (arteriovenous oxygen difference) and/or no changes in cardiac output (8,12,13,15). Furthermore, data on age-related differences in exercise left ventricular (LV) filling pressures are scant and reported predominantly with supine exercise studies (10,14), and their contribution to the decline in peak exercise VO2 with aging is not well understood.

In this cross-sectional, prospective study, we aimed to understand the determinants of the age-related decline in peak VO2 by evaluating the association of age with invasive cardiovascular hemodynamic parameters at rest and during upright exercise in healthy men and women, who were well screened for cardiac disease, across a relatively broad age range. We hypothesized that older age would be associated with blunted augmentation in stroke volume and heart rate and an exaggerated exercise increase in pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PWP).

METHODS

STUDY DATA SOURCE.

The present study was performed between 1982 and 1989, and data were analyzed and Figures produced at the end of the study period (1989). Please see the Online Appendix for an expanded Methods section for full details about the study data source.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS.

Healthy volunteers were recruited from the community under a research protocol approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Volunteers were initially screened by telephone interview and, if they had no apparent exclusionary criteria, were invited for a detailed interview and serial examinations. Study participants fulfilled all of the following criteria: 1) no history of cardiac, pulmonary, or any other medical disease; 2) normal physical examination, including normal seated cuff blood pressures on 2 separate days; 3) not participating in competitive athletics, isometric exercise, or endurance training; 4) no current or recent medication use; 5) normal complete blood count, electrolytes, and thyroid function panel; 6) normal spirometry and arterial blood gas analysis; 7) no coronary artery calcification by fluoroscopy; 8) normal 12-lead resting electrocardiogram; 9) normal maximal exercise electrocardiogram; and 10) normal rest and maximal exercise radionuclide ventriculograms. Participants ≥60 years of age also underwent screening using Doppler echocardiograms.

STUDY PROTOCOL.

All participants were studied under identical laboratory conditions in the postabsorptive state. After administration of local anesthetic, a 7-F Swan-Ganz catheter was introduced under fluoroscopic control into the right pulmonary artery via the right antecubital vein, and an 18-gauge plastic cannula was introduced percutaneously into the left brachial artery. Exercise testing was performed in the upright position on a Fitron isokinetic bicycle (Lumex, Ronkowkoma, New York). The workload was begun at 25 W and was advanced by 25-W increments in 3-min stages to exhaustion.

Gas exchange, hemodynamic, and radionuclide measurements were simultaneously obtained at rest in the seated position and then at each workload as previously described (6,16). Continuous expired gas analysis was performed with a commercially available SensorMedics 4400 unit (Yorba Linda, California) that was calibrated before each study (6). Hemodynamic pressures were obtained using Hewlett Packard (Palo Alto, California) pressure transducers and amplifiers (6,16). Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was obtained from the brachial artery cannula, and mean pulmonary artery wedge pressure was obtained from the Swan-Ganz catheter. Blood samples were obtained at rest and in the last minute of each exercise stage and were immediately placed in an ice bath. Oxygen content and saturation of arterial and mixed venous blood samples were measured on a calibrated IL 282 CO-Oximeter (Instrumentation Laboratory Inc., Lexington, Massachusetts). Arterial lactate concentration was determined with a rapid lactate kit (Calbiochem-Behring, San Diego, California). Gated equilibrium radionuclide ventriculograms were acquired at rest and at each workload with an LEM mobile gamma camera (Searle, Skokie, Illinois) with a high-sensitivity 30° slant hole collimator interfaced with an A2 computer (Medical Data Systems, Ann Arbor, Michigan) following injection of 30 mCi technetium99m pertechnetate as previously described (6).

DERIVED VARIABLES.

Cardiac output was determined using the Fick principle (cardiac output = VO2/arteriovenous oxygen difference) and was indexed to the body surface area to obtain the cardiac index. LV ventricular end-diastolic volume and end-systolic volume indexes were calculated from the Fick stroke volume index and the radionuclide ejection fraction as previously described (6,16).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

Linear regression analyses were performed using the least squares method to determine the relationship of age to the other measured variables. Group differences were analyzed using the unpaired Student’s t-test. Significance was established at the level of p < 0.05 (2-tailed analysis). Numerical data are presented as mean ± SD. Graphic data are presented as plots for each variable versus age along with correlation coefficients (r) and p values for each relationship. For variables significantly related to age, regression lines are shown. To denote the strength of age relationships, regression lines are solid for variables with regression coefficients ≥0.30 and dashed for variables with coefficients <0.30. Regression lines are absent where there was no significant age relationship.

RESULTS

There were 104 participants (mean age 41 ± 15.7 years) with 69% men (mean age 40 years, range 20 to 76 years) and 31% women (mean age 40 years, range 21 to 67 years) (Table 1). Regular aerobic exercise activity (at least 20 min 3 times per week) was reported by 39% (n = 41) of participants; there was no difference in the age of these participants versus those who did not participate in regular exercise (age 42 ± 17 years vs. 39 ± 14 years; p = 0.31). There was no significant association between age and body surface area (r = 0.02; p = 0.30) or weight (r = −0.07; p = 0.50) (Online Figure 1), such that traditional indexing by body size would not affect age relationships.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Participants (N = 104)

| Age, yrs | 20–76; 41 ± 16 |

| Women | 31 |

| Proportion with regular aerobic exercise | 39 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.85 ± 0.18 |

| Mean arterial blood pressure, mm Hg | 99 ± 12 |

| Resting hemodynamic parameters | |

| Peak oxygen uptake, ml/m2/min | 156.1 ± 27.7 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 77 ± 13 |

| Cardiac index, l/m2/min | 2.9 ± 0.9 |

| Indexed stroke volume, ml/m2 | 37 ± 10 |

| Arteriovenous oxygen difference, vol % | 5.8 ± 1.2 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mm Hg | 2 ± 3 |

| Indexed left ventricular end-diastolic volume, ml/m2 | 59 ± 17 |

| Resting ejection fraction, % | 64 ± 9 |

Values are range, mean ± SD, or %, unless otherwise indicated.

EXERCISE ENDPOINTS.

Nearly all participants (n = 97) exercised to exhaustion, achieving a peak workload ≥100 W; 7 participants (1 male and 6 females) exercised to a peak of 75 W. Older age was significantly associated with a reduced peak workload (r = −0.58; p < 0.001) and peak VO2 (r = −0.57; p < 0.001) with an 8% lower peak VO2 per 10-year increment in age. Nearly all study participants (n = 102) had a respiratory exchange ratio at peak exercise ≥1.15; 2 participants had peak respiratory exchange ratios of 1.04 and 1.10, respectively. Older age was not associated with a lower peak respiratory exchange ratio (r = −0.01; p = 0.90). All but 3 participants achieved ≥85% of age-predicted maximal heart rate. Older participants showed a modest trend toward achieving a higher proportion of age-predicted maximal heart rate (r = 0.19; p = 0.058). All participants had at least a 5-fold increase in arterial lactate from rest to peak exercise, with significantly lower peak lactate levels observed among older participants (r = −0.45; p < 0.001). Therefore, all participants exercised to maximal or near-maximal endpoints.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN AGE AND HEMODYNAMIC PARAMETERS AT REST.

Comparisons of the resting hemodynamic parameters in the overall cohort and across different age groups are shown in Tables 2 and 3. At upright rest, older age was associated with lower measures of unindexed (r = −0.27; p < 0.01) and indexed VO2 (r = −0.20; p < 0.05), with a 12% progressive decline in resting VO2 from younger (<40 years) to older (≥60 years) age groups (Figure 1A). A significant inverse association was observed between age and resting cardiac index (r = −0.39; p < 0.001) as well as age and resting stroke volume index, with a 23% decline across the age distribution (Figures 1B and 1C). At rest, older age was significantly associated with a higher arteriovenous oxygen difference (r = 0.32; p < 0.001) (Figure 1D), slightly higher upright PWP (r = 0.17; p < 0.05) (Figure 2A), and higher MAP (r = 0.46; p < 0.001). Age was not associated with the resting heart rate (r = 0.10; p = 0.15) (Figure 2B).

TABLE 2.

Group Average Hemodynamic Measurements at Submaximal (50 W) and Peak Exercise

| Submaximal Exercise | Peak Exercise | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Peak oxygen uptake, ml/m2/min | 454 ± 72 | 1,113 ± 216 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 101 ± 17 | 168 ± 17 |

| Cardiac index, l/m2/min | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 8.3 ± 2.2 |

| LV stroke volume index, ml/m2 | 51 ± 11 | 49 ± 11 |

| LV end-diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | 72 ± 18 | 65 ± 16 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 71 ± 8 | 75 ± 10 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mm Hg | 4.5 ± 3.1 | 9 ± 4 |

| Arteriovenous oxygen difference, vol % | 9.0 ± 1.4 | 13.5 ± 2.1 |

Values are mean ± SD.

LV = left ventricular.

TABLE 3.

Group Average Hemodynamic Measurements at Rest, Submaximal (50 W), and Peak Exercise Across Different Age Groups

| Resting |

Submax (50 W) |

Peak Exercise |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 yrs | 40–60 yrs | >60 yrs | <40 yrs | 40–60 yrs | >60 yrs | <40 yrs | 40–60 yrs | >60 yrs | |

|

| |||||||||

| Peak oxygen uptake, ml/m2/min | 160 ± 29 | 160 ± 24 | 141 ± 25 | 465 ± 75 | 479 ± 55 | 392 ± 46 | 1,226 ± 252 | 1,081 ± 282 | 792 ± 179 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 79 ± 13 | 76 ± 12 | 75 ± 16 | 102 ± 16 | 100 ± 1 | 99 ± 18 | 178 ± 10 | 160 ± 13 | 148 ± 11 |

| Left ventricular stroke volume index, ml/m2 | 39 ± 10 | 40 ± 10 | 31 ± 10 | 54 ± 11 | 54 ± 11 | 40 ± 7 | 52 ± 11 | 52 ± 10 | 39 ± 6 |

| Cardiac index, l/m2/min | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 1.3 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 9.3 ± 1.9 | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 1.1 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 64 ± 9 | 65 ± 8 | 65 ± 10 | 71 ± 7 | 72 ± 8 | 71 ± 10 | 78 ± 10 | 73 ± 10 | 71 ± 10 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mm Hg | 2 ± 2.6 | 3 ± 2.3 | 3 ± 3.3 | 4.3 ± 3.3 | 5.0 ± 2.7 | 4.4 ± 3.3 | 9 ± 3.8 | 8 ± 3.4 | 8 ± 4.8 |

| Arteriovenous oxygen difference, vol % | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 8.6 ± 1.2 | 9.2 ± 1.5 | 10.1 ± 1.3 | 13.5 ± 2.0 | 13.2 ± 2.4 | 13.4 ± 1.8 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | 62 ± 18 | 61 ± 14 | 47 ± 14 | 77 ± 17 | 75 ± 11 | 58 ± 11 | 67 ± 17 | 71 ± 15 | 56 ± 11 |

Values are mean ± SD.

FIGURE 1. Association of Age With Oxygen Uptake and its Determinants at Rest.

Correlations between age and the following parameters at upright rest: (A) oxygen consumption, (B) cardiac index, (C) stroke volume index, and (D) arteriovenous oxygen (A-V O2) difference.

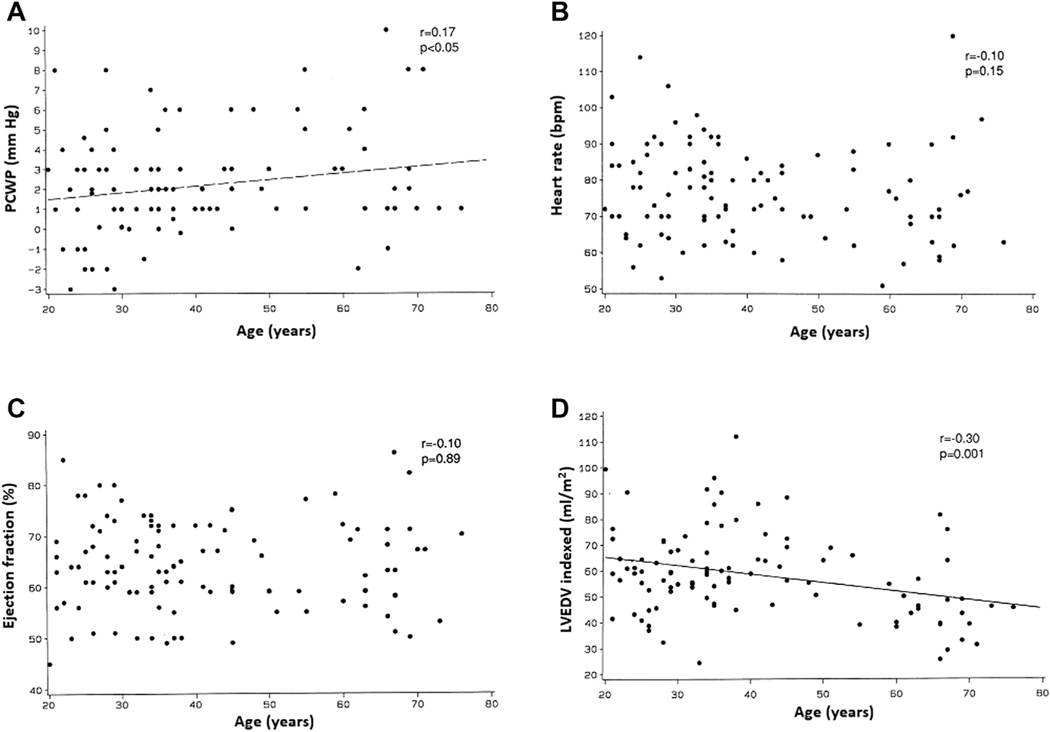

FIGURE 2. Association of Age With Cardiac Function and Hemodynamic Parameters at Rest.

Correlations between age and the following parameters at upright rest: (A) pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), (B) heart rate, (C) ejection fraction, and (D) left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (LVEDV).

Age was not associated with the resting LV ejection fraction (r = −0.10; p = 0.89) (Figure 2C). However, older age was significantly associated with lower LV end-diastolic volume (r = −0.30; p = 0.001) (Figure 2D) and end-systolic volume indexes (not shown; r = −0.20; p = 0.04).

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN AGE AND HEMODYNAMIC PARAMETERS AT UPRIGHT SUBMAXIMAL EXERCISE.

During submaximal exercise at the fixed workload of 50 W, the age relationships for VO2, cardiac index, heart rate, stroke volume index, ejection fraction, end-diastolic and end-systolic volume indexes, and MAP were relatively similar to those observed at upright rest. The arteriovenous oxygen difference was further increased with advancing age, and PWP showed no age association (Table 3, Online Figures 2 and 3).

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN AGE AND HEMODYNAMIC PARAMETERS AT UPRIGHT PEAK EXERCISE.

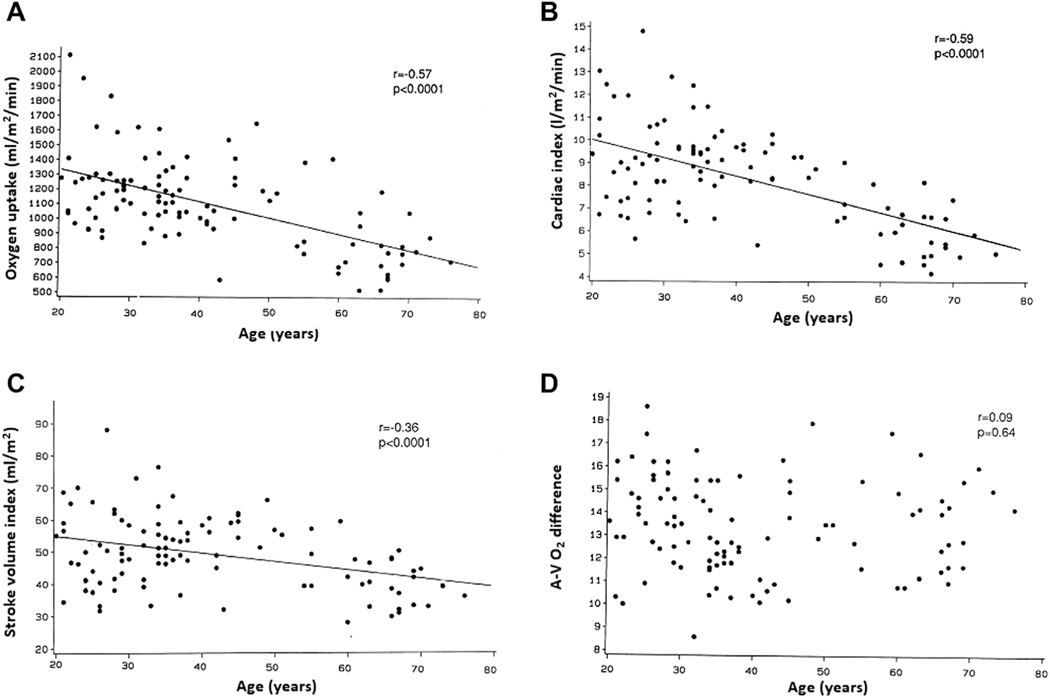

A comparison of the peak exercise hemodynamic parameters across different age groups is shown in Table 3. At peak exercise, older age was associated with significantly lower unindexed and indexed measures of peak VO2 (r = −0.50 and r = −0.57, respectively; p < 0.001 for both) (Figure 3A), with a ~40% reduction in parameters across the age distribution. Similarly, older age was significantly associated with a lower cardiac index (r = −0.59; p < 0.001) (Figure 3B) and stroke volume index (r = −0.36; p < 0.001) (Figure 3C) at peak exercise and was 38% and 25% lower, respectively, among older (>60 years) versus younger age groups (<40 years) (Table 3). In contrast, there was no significant association between age and peak arteriovenous oxygen difference (r = 0.09; p = 0.64) (Figure 3D).

FIGURE 3. Association of Age With Oxygen Uptake and its Determinants at Peak Exercise.

Correlations between age and the following parameters at upright peak exercise: (A) oxygen consumption, (B) cardiac index, (C) stroke volume index, and (D) arteriovenous oxygen (A-V O2) difference.

Age was also not associated with peak exercise PWP (r = 0.08; p = 0.59) (Figure 4A) but was significantly associated with higher MAP (r = 0.25; p < 0.01). There was a strong inverse association between age and peak exercise heart rate (r = −0.75; p < 0.001) (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4. Association of Age With Cardiac Function and Hemodynamic Parameters at Peak Exercise.

Correlations between age and the following parameters at upright peak exercise: (A) PCWP, (B) heart rate, (C) ejection fraction, and (D) LVEDV. Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

Older age was significantly associated with a lower peak LV ejection fraction (r = −0.31; p < 0.001) (Figure 4C) but not with end-diastolic (r = −0.15; p = 0.07) (Figure 4D) or end-systolic volume indexes (not shown; r = 0.12; p = 0.25).

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN AGE AND MEASURES OF EXERCISE CARDIAC RESERVE.

There were significant inverse associations between age and the absolute increase from rest to peak exercise in VO2 (r = −0.56; p < 0.001), cardiac index (r = −0.52; p < 0.001), heart rate (r = −0.65; p < 0.001), and LV ejection fraction (r = −0.36; p < 0.001) and a modest inverse relationship with arteriovenous oxygen difference (r = −0.28; p < 0.01). Older age was also significantly associated with a lesser decrease in end-systolic volume index (r = 0.31; p < 0.001) and a greater decrease in systemic vascular resistance index (r = −0.37; p < 0.001) from rest to peak exercise. Age was not associated with changes in stroke volume index, end-diastolic volume index, or MAP from rest to peak exercise. Neither the change in MAP nor the change in systemic vascular resistance index during exercise was related to the change in LV ejection fraction or end-systolic volume.

EFFECT OF SEX.

In sex-stratified analyses, the associations between age and cardiovascular parameters at rest, submaximal exercise, and peak exercise were similar to that observed in the overall cohort.

DISCUSSION

The present study has several important findings. First, at rest and submaximal upright exercise, older age was associated with significantly lower peak VO2, cardiac index, and LV stroke volume index. Second, older age was associated with higher PWP at rest, but, contrary to our hypothesis, PWP during submaximal and maximal exercise was not age related. Third, at peak exercise, older age was significantly associated with lower VO2 and cardiac index, with up to a 40% reduction in these parameters over the 5.5-decade age span. Fourth, this was related primarily to lower peak exercise heart rate and peak stroke volume indexes (22% and 35% reduction over 5.5 decades, respectively) (Central Illustration). Finally, these age relationships were independent of sex. These findings highlight specific age-related changes in cardiovascular hemodynamics with upright, exhaustive exercise in healthy individuals, which may contribute to the age-related decline in exercise capacity.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Mechanisms of Decline in Exercise Capacity With Healthy Aging.

Changes in peak exercise hemodynamic parameters associated with healthy aging. A-V O2 diff. = exercise arteriovenous-oxygen difference; CO = cardiac output; HR = heart rate; PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; SV = stroke volume; VO2 = oxygen uptake.

We observed a 40% reduction in peak VO2 among over a 5.5-decade span, amounting to ~8% decline per decade. This is comparable with the age-related decline in peak VO2 observed in prior studies (17). The mechanisms underlying the substantial age-related decline in peak VO2 have been debated. In the present study, we observed a significant inverse association between age and cardiac index, stroke volume index, ejection fraction, and heart rate at peak exercise. Taken together, these findings suggest that lower peak VO2 in older age is driven primarily by lower peak exercise heart rate and stroke volume. Consistent with our observations, most studies using the direct Fick technique, dye dilution, or acetylene rebreathing to assess cardiac output have demonstrated significantly lower cardiac index and maximal heart rate in older individuals (5–7,9,10). However, the association between age and stroke volume during exercise has been controversial. Some prior studies have demonstrated lower peak exercise stroke volume in older individuals (5,7), whereas others reported no age-related changes or even an increase (6,8,9,15,18).

Several factors such as differences in age range (6), sex distribution (9,15), and posture (upright vs. supine exercise) (9) may underlie the discordant findings across studies regarding the association between age and exercise stroke volume. It is noteworthy that exercise stroke volume was not different among young versus middle-age subgroups (<40 years vs. 40 to 60 years), and lower exercise stroke volume was noted only in older individuals (≥60 years age). Along these lines, Higginbotham et al. (6) observed no significant age-related decline in exercise stroke volume in a previous study using a younger subset of our study cohort (<50 years). Supporting this, in the Dallas Bed Rest Study (12), there was no decline in stroke volume at peak exercise during longitudinal follow-up from age 20 to 50 years (30-year follow-up from baseline), but there was a decline between 50 and 60 years of age (40-year follow-up from baseline) (12,19). It is plausible that impairment in exercise LV contractile reserve, which was observed in the present study and by other investigators, occurs at a later age and, thus, would not have been detected in the younger population.

Prior studies that have performed direct, invasive measures of arteriovenous oxygen difference have, like the present study, found no significant association between age and peak exercise arteriovenous oxygen difference (6,14,16), whereas others have suggested a decrease with aging (7,12,15). In the present study, the findings of a significantly increased arteriovenous oxygen difference at submaximal exercise, apparently compensating for lower cardiac output, and a smaller absolute increase from rest to exercise suggest the possibility that the reduced arteriovenous oxygen reserve may have contributed, along with reduced cardiac output, to the lower peak VO2 with aging. This would be expected based on the prior observations of reduced capillary density and skeletal muscle oxidative capacity with aging (20).

Findings from our study also add significantly to the available published reports by examining the association between age and LV filling pressure at peak upright exercise. Contrary to our hypothesis, we observed no significant association between age and peak exercise PWP. This is in contrast to a recent study by Wolsk et al. (14), who reported higher PWP with exercise among older individuals. However, Wolsk et al. (14) performed exercise hemodynamic assessments in the supine position, the workload was calibrated equivalent to submaximal upright exercise (21), and only exercise electrocardiographic screening was used (14) to exclude ischemic heart disease, such that some older participants could have had exercise-induced ischemia to account for the increased exercise PWP. Van Empel et al. (10) also reported age-related increased LV filling pressure with supine peak exercise. The most likely explanation for the difference in LV filling pressure findings in these 2 supine exercise studies and the present upright study is that there are marked, fundamental differences in intracardiac hemodynamics between upright and supine exercise (21,22). In healthy persons in the supine position, LV filling pressure at rest is already near the maximum achieved at upright exercise, and with supine exercise, LV filling pressure only increases ≤1-fold (14,21). In contrast, in the upright position, LV pressure is minimized at rest and is very low, as confirmed in this study (2 ± 3 mm Hg), due to the effects of gravity and venous pooling. Then, with exercise and activation of the “muscle pump,” volume is returned to the central circulation, and LV filling pressure progressively increases up to 4-fold (21,22). Thus, LV filling pressures and diastolic volumes are not comparable between upright and supine exercise, and as discussed previously, the upright position is the most relevant to ordinary physical activity.

Taken together, these data suggest that the primary mechanism of the age-related decline in peak VO2 is a decline in exercise cardiac output reserve. The age-related reduction in cardiac output reserve is due primarily to a combination of reduced heart rate and LV contractile reserve (lower ejection fraction and higher end-systolic volume at peak exercise). The reduced inotropic response in older participants was not due to increased afterload as evidenced by an inverse association between age and change in systemic vascular resistance with exercise (r = −0.37; p < 0.001). Likely due to decreased LV diastolic compliance, older individuals demonstrated an inability to compensate for age-related declines in chronotropic and inotropic reserve by engaging the Frank-Starling mechanism because they had lower peak exercise end-diastolic volume despite LV filling pressures that were similar to younger individuals.

Our study findings have several important clinical implications. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing has been proposed as an important tool to identify older individuals at risk for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF); diagnose early, mild HFpEF by unmasking pathological abnormalities in hemodynamic exercise reserve; and guide treatment strategies for patients with established HFpEF (23,24). However, this can be challenging due to significant alterations in exercise parameters due to aging alone. The present results help establish normative standards and identify potential cutoffs for objectively assessed cardiovascular hemodynamic parameters during upright exercise, which could facilitate HFpEF diagnosis. Interestingly, these data suggest that thresholds for normal PWP during upright exercise may not need to be adjusted for age. These results also provide insight into potential pathophysiological mechanisms that may underlie the development of clinical HFpEF in older individuals because even at rest there was evidence of mildly reduced LV diastolic compliance (lower end-diastolic volume despite higher PWP), and with exercise there was reduced chronotropic, inotropic, and cardiac output reserve with inability to compensate via the Frank-Starling mechanism, suggesting reduced LV diastolic compliance.

STUDY STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS.

The present study has several strengths, including rigorous screening to exclude the effects of overt and occult cardiovascular disease, a relatively large cohort, a relatively wide age span, representation of both sexes, invasive measurements with systemic and pulmonary artery catheters, measurement of cardiac output by the Fick technique, simultaneous expired gas analysis and radionuclide angiography, and use of the upright position for exercise. These methods were designed to overcome some of the key limitations of prior studies. Direct measurements of PWP and arteriovenous oxygen difference during maximal exercise in healthy older persons are particularly rare and highly informative.

The study also has some limitations. First, because of the need for minimization of chest motion in order to obtain quality radionuclide ventriculographic data, bicycle exercise was used, which has been variably reported to result in a slightly lower peak VO2 than treadmill exercise. However, all participants underwent identical testing such that this should not have affected the age relationships. Second, although a plateau in exercise VO2 was not specifically sought, all participants exercised to exhaustion and had at least a 5-fold increase in arterial lactate during exercise, and nearly all achieved a peak workload of 100 W, had a respiratory exchange ratio at peak exercise ≥1.15, and achieved at least 85% of their age-predicted maximum heart rate. Thus, the differences in peak workload and oxygen consumption among participants were unlikely to be related to diminished intensity of effort or motivation. Third, even with rigorous screening methods applied in this study to exclude the effects of cardiac disease, it is not possible to ensure that no participant with mild, occult coronary artery disease was included. However, the results obtained were highly significant statistically, relatively uniform across the age range, and were unlikely to have been affected significantly in such a case. Moreover, subjects age ≥65 years were contacted at the 5-year follow-up, and none had had a cardiovascular event, confirming lack of cardiovascular disease at the time of exercise testing. Fourth, although we excluded competitive athletes and endurance training and there was no significant relation of age with reported regular exercise, we cannot exclude a potential effect of the level of habitual physical activity. However, it is known that peak VO2 declines with aging even with lifelong, regular high-level exercise. Fifth, submaximal data were assessed at a fixed, 50-W workload, which may represent differing percentages of maximal, and this should be taken into account when interpreting these data. Sixth, as detailed in the Online Appendix, these hemodynamic studies were conducted from 1982 to 1989. The raw data are in formats incompatible with current programs, limiting the range of new, individual-level analyses. The hemodynamic data in the tables were extracted from the previously generated plot Figures using image digitalizer software. Furthermore, some of the physiological study protocols and techniques used in this study are different from those used in the current era. However, all studies were performed using identical protocols and laboratory conditions, so the age-related trends observed should be valid. Endothelial function, which may play a role in age-related decline in exercise capacity, was not assessed. Despite the time period of data collection, fundamental, normative human exercise physiology should not have changed significantly.

CONCLUSIONS

Invasive cardiovascular hemodynamics during exhaustive upright exercise across a broad age range of healthy men and women indicate that the mechanisms for the age-related decline in peak VO2 are predominantly central cardiac with reduced chronotropic and inotropic reserve. Peak exercise PWP and arteriovenous oxygen difference are not age related.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE:

These results provide normative standards for cardiovascular hemodynamic parameters during upright exhaustive exercise and insight to the mechanisms of the marked age-related decline in exercise capacity.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK:

These results support future longitudinal follow-up studies to understand how aging changes in exercise hemodynamic reserve may contribute to the development of HF in older persons.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Kitzman is supported in part by National Institute of Health grants R01AG18915, P30AG021332, and R01AG045551, and the Kermit G. Phillips Endowed Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- HF

heart failure

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- LV

left ventricular

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- PWP

pulmonary artery wedge pressure

- VO2

oxygen uptake

Footnotes

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Upadhya B, Pisani B, Kitzman DW. Evolution of a geriatric syndrome: pathophysiology and treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:2431–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry JD, Pandey A, Gao A, et al. Physical fitness and risk for heart failure and coronary artery disease. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:627–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleg JL, Morrell CH, Bos AG, et al. Accelerated longitudinal decline of aerobic capacity in healthy older adults. Circulation 2005;112:674–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imboden MT, Harber MP, Whaley MH, Finch WH, Bishop DL, Kaminsky LA. Cardiorespiratory fitness and mortality in healthy men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2283–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correia LC, Lakatta EG, O’Connor FC, et al. Attenuated cardiovascular reserve during prolonged submaximal cycle exercise in healthy older subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:1290–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higginbotham MB, Morris KG, Williams RS, Coleman RE, Cobb FR. Physiologic basis for the age-related decline in aerobic work capacity. Am J Cardiol 1986;57:1374–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogawa T, Spina RJ, Martin WH 3rd., et al. Effects of aging, sex, and physical training on cardiovascular responses to exercise. Circulation 1992;86:494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodeheffer RJ, Gerstenblith G, Becker LC, Fleg JL, Weisfeldt ML, Lakatta EG. Exercise cardiac output is maintained with advancing age in healthy human subjects: cardiac dilatation and increased stroke volume compensate for a diminished heart rate. Circulation 1984;69:203–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stratton JR, Levy WC, Cerqueira MD, Schwartz RS, Abrass IB. Cardiovascular responses to exercise. Effects of aging and exercise training in healthy men. Circulation 1994;89:1648–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Empel VP, Kaye DM, Borlaug BA. Effects of healthy aging on the cardiopulmonary hemodynamic response to exercise. Am J Cardiol 2014;114:131–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arbab-Zadeh A, Dijk E, Prasad A, et al. Effect of aging and physical activity on left ventricular compliance. Circulation 2004;110:1799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGuire DK, Levine BD, Williamson JW, et al. A 30-year follow-up of the Dallas Bedrest and Training Study: I. Effect of age on the cardiovascular response to exercise. Circulation 2001;104:1350–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esposito F, Mathieu-Costello O, Shabetai R, Wagner PD, Richardson RS. Limited maximal exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: partitioning the contributors. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1945–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolsk E, Bakkestrom R, Thomsen JH, et al. The influence of age on hemodynamic parameters during rest and exercise in healthy individuals. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beere PA, Russell SD, Morey MC, Kitzman DW, Higginbotham MB. Aerobic exercise training can reverse age-related peripheral circulatory changes in healthy older men. Circulation 1999;100:1085–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan MJ, Cobb FR, Higginbotham MB. Stroke volume increases by similar mechanisms during upright exercise in normal men and women. Am J Cardiol 1991;67:1405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitzman DWUB, Haykowsky M Effects of aging on cardiovascular structure and function. In: Halter JP, editor. Hazzard’s Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education, 2017:1129–43. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleg JL, O’Connor F, Gerstenblith G, et al. Impact of age on the cardiovascular response to dynamic upright exercise in healthy men and women. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1995;78:890–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGavock JM, Hastings JL, Snell PG, et al. A forty-year follow-up of the Dallas Bed Rest and Training study: the effect of age on the cardiovascular response to exercise in men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:293–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coggan AR, Spina RJ, Rogers MA, et al. Histochemical and enzymatic characteristics of skeletal muscle in master athletes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1990;68:1896–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poliner LR, Dehmer GJ, Lewis SE, Parkey RW, Blomqvist CG, Willerson JT. Left ventricular performance in normal subjects: a comparison of the responses to exercise in the upright and supine positions. Circulation 1980; 62:528–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higginbotham MB, Morris KG, Williams RS, McHale PA, Coleman RE, Cobb FR. Regulation of stroke volume during submaximal and maximal upright exercise in normal man. Circ Res 1986;58:281–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CS, Redfield MM. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2010; 3:588–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorajja P, Borlaug BA, Dimas VV, et al. SCAI/HFSA clinical expert consensus document on the use of invasive hemodynamics for the diagnosis and management of cardiovascular disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2017;89:E233–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.