Abstract

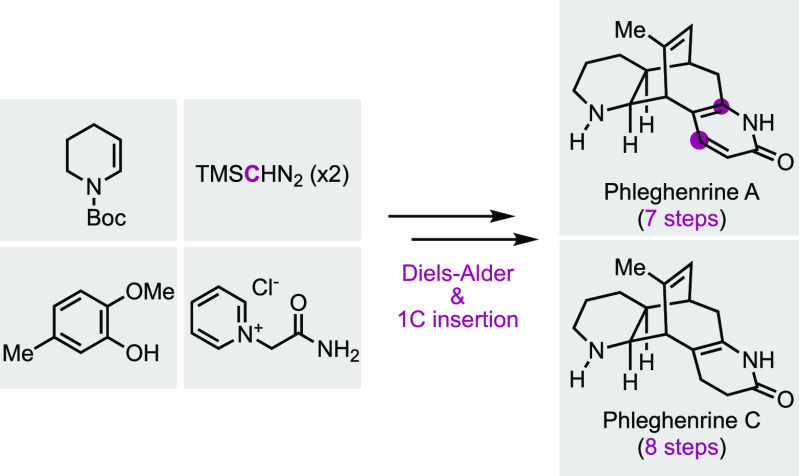

Herein, we report the total syntheses of phleghenrines A and C from commercially available starting materials in 7 and 8 steps, respectively. Notable steps include an inverse electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction between a masked o-benzoquinone and a N-protected enamine to prepare one key intermediate with a bicyclo[2.2.2]octenone core, a Büchner–Curtius–Schlotterbeck one-carbon insertion to expand the bicyclo[2.2.2]octenone to a bicyclo[3.2.2]nonenone, and Trauner’s modified 2-pyridone synthesis to install the 2-pyridone moiety.

Phleghenrines A–D (1–4, Figure 1) and neophleghenrine A (5) were isolated by Zhao and co-workers in 2016 from Phlegmariurus henryi Ching, part of the Huperziaceae.1 In addition to the phleghenrine molecules, Phlegmariurus henryi Ching was reported to produce huperzine A (6) and B (7), two famous lycopodium alkaloids with potent acetylcholinesterase inhibition activity. Huperzine A has been used as a new drug to treat Alzheimer’s disease in China and as a dietary supplement in the United States.2 It was evaluated in human clinical trials to treat traumatic brain injury as well. The phleghenrine molecules also demonstrated inhibitory activity against acetylcholinesterase with phleghenrine A (1) and D (4) as the most potent family members (IC50 = 4.91 μM for 1 and 4.32 μM for 4). Notably, the phleghenrines showed low or no inhibition activity against butylcholinesterase; thus, they may exhibit less side effects such as hepatoxicity. While phleghenrines A, B, and D share a similar 2-pyridone moiety as huperzines A and B as well as lyconadins A and C,3 another two lycopodium alkaloids with neurotrophic activity, the phleghenrines have a distinct and complex tetracyclic skeleton featuring a bicyclo[3.2.2]nonene core. Their novel chemical structures and potent acetylcholinesterase inhibition activity render them promising lead compounds for the drug discovery efforts in searching for effective treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other related neurodegenerative disorders. However, the low isolation yield (<0.0003%) is a major hurdle for their further biomedical development. In 2019, Sarpong and co-workers reported their synthetic studies to construct the [3.2.2] bicycles of the phleghenrines.4 While this manuscript was in preparation, She and co-workers reported their total syntheses of phleghenrines A and C in 19 and 18 steps, respectively, from a known diene, which requires 4 steps to prepare.5 Herein, we reported our total syntheses of phleghenrines A and C in 7 and 8 steps, respectively.6

Figure 1.

Phleghenrines and related alkaloids.

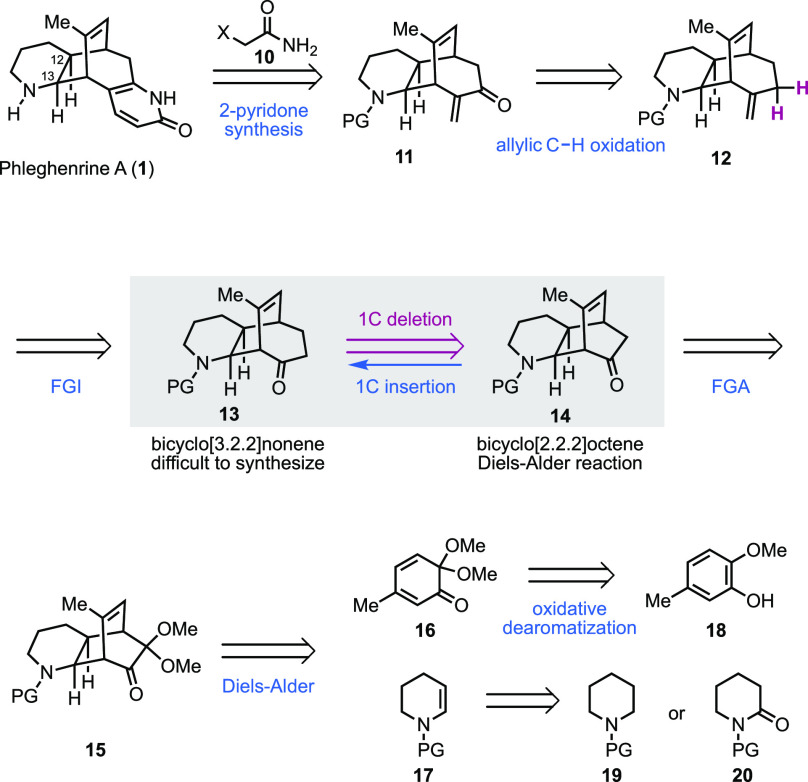

Our continued interest7 in the total synthesis and biological studies of lycopodium alkaloids with the therapeutic potential to treat various neurodegenerative disorders prompted us to pursue the total synthesis of the phleghenrine alkaloids. Retrosynthetically (Figure 2), similar to our total synthesis of lyconadins A and C,7a we decided to install the 2-pyridone moiety in the end by using the Fukuyama-Yokoshima 2-pyridone synthesis.8 Thus, tricyclic α-methylene ketone 11 with a bicyclo[3.2.2]nonene core was needed and could be synthesized from ketone 13 via a sequence of methylenation and allylic oxidation. In comparison to the bicyclo[3.2.2]nonene ring systems, the bicyclo[2.2.2]octene ring systems are much more accessible via reactions, including the Diels–Alder cycloaddition. With this in mind, we practiced a one-carbon deletion retrosynthetically and proposed intermediate 14 with a bicyclo[2.2.2]octene core as the precursor of 11. In the forward sense, a one-carbon insertion protocol is needed. Accordingly, we envisioned an approach involving a Büchner–Curtius–Schlotterbeck one-carbon homologation with (trimethylsilyl)diazomethane to convert the cyclohexenone to a cycloheptenone (14 → 13).9 Retrosynthetically, an acetal functional group addition strategy at this stage would lead to compound 15 as a precursor of 14. We planned to assemble 15 via an inverse electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction between masked o-benzoquinone (MOB) 16 and N-protected enamine 17.10 MOB 16 could be synthesized via an oxidative dearomatization of commercially available 2-methoxy-5-methylphenol (18), and 17 could be prepared via a formal dehydrogenation of piperidine derivative 19(11) or reduction of the corresponding δ-valerolactam 20.12

Figure 2.

Retrosynthetic analysis.

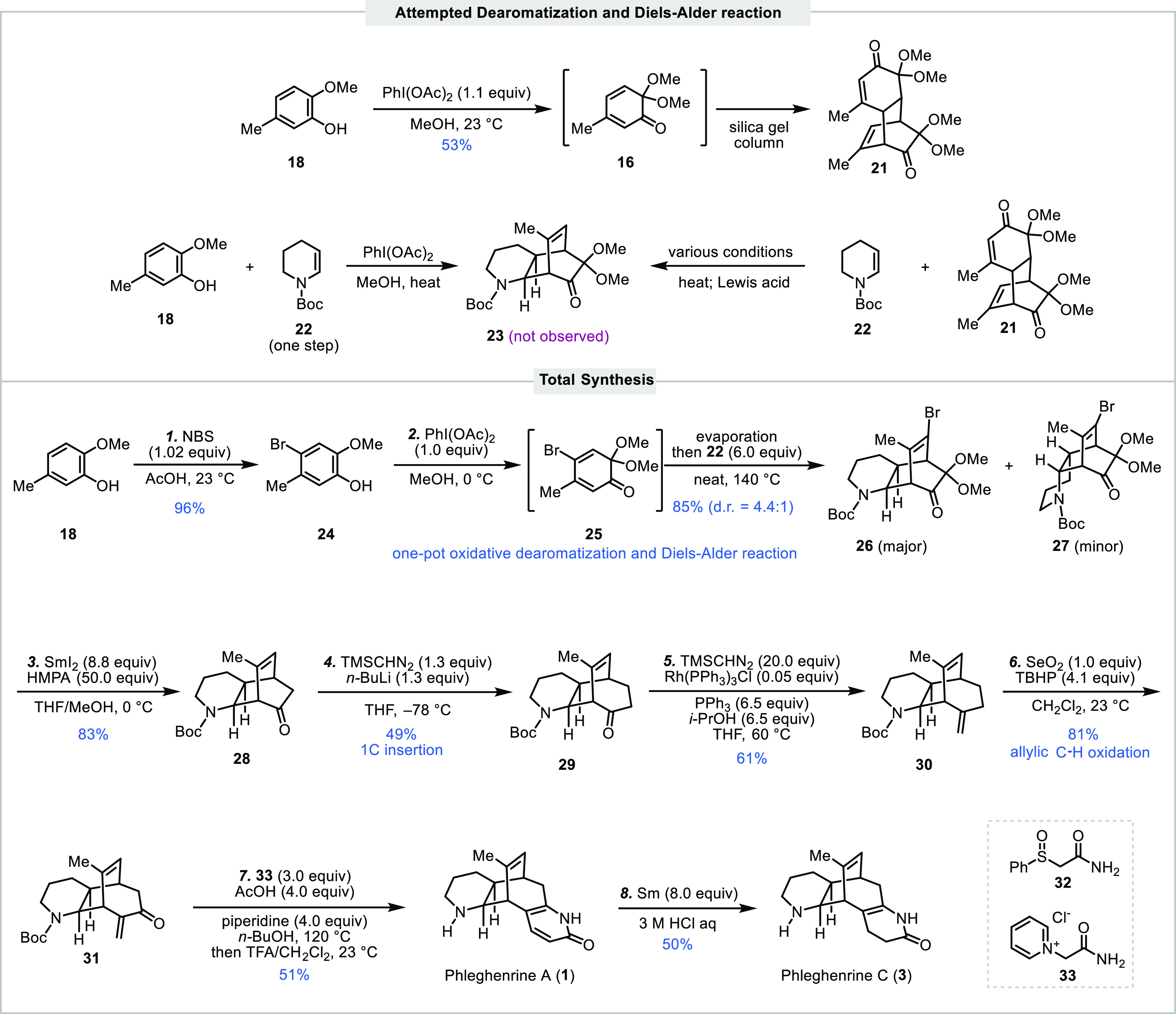

Our synthesis started from commercially available 2-methoxy-5-methylphenol (18) and known Boc-protected enamine 22 (Scheme 1). The latter can be synthesized in one step from commercially available N-Boc-protected δ-valerolactam12 or N-Boc-protected piperidine.11 We first tried to generate MOB 16 via an oxidative dearomatization of 18 with phenyliodonium diacetate in MeOH. While 16 could be formed smoothly, it underwent spontaneous Diels–Alder dimerization and cannot be isolated. Instead, dimeric product 21 was obtained. Efforts were then directed to trap MOB 16 in situ with dienophile 22 to form 23 but were unsuccessful. Since the Diels–Alder dimerization of 16 is reversible, we also explored the possibility of generating 16 via a retro-Diels–Alder reaction from 21 and trapping it in situ with 22. Unfortunately, no desired product 23 was observed, as well. To avoid the problematic MOB dimerization, we decided to install a bromide at the C-4 position of 16 (see 25). The bromide has been shown to block the dimerization and can be removed later.13 Thus, known compound 24 was prepared in 96% yield by bromination of 18 with a reported procedure using N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) in AcOH.14 As expected, oxidative dearomatization of 24 with phenyliodonium diacetate in MeOH gave known Br-MOB 25, which can be purified and characterized. After evaporation of MeOH, 22 was added, and the resulting neat mixture was heated at 140 °C to deliver the Diels–Alder adducts via a one-pot procedure in 85% yield as a separable 4.4:1 endo/exo (26/27) mixture. The bromide, after serving its purpose of blocking the MOB dimerization, was then removed with SmI2, which also removed the extra dimethyl acetal at the α-position of the ketone. Tricyclic compound 28 with a bicyclo[2.2.2]octenone core was obtained in 83% yield.

Scheme 1. Total Syntheses of Phleghenrines A and C.

We then moved on to explore the Büchner–Curtius–Schlotterbeck one-carbon insertion and were happy to learn that desired product 29 with a bicyclo[3.2.2]nonenone core could be obtained in 41% yield by exposing 28 to (diazo(trimethylsilyl)methyl)lithium generated from treating (trimethylsilyl)diazomethane with n-BuLi in THF at low temperature. Compound 29 was further advanced to α-methylene ketone 31 in two steps for the next 2-pyridone synthesis. The Wittig one-carbon homologation was realized by using the Lebel modification, which releases methylenetriphenylphosphorane catalytically from the Wilkinson’s catalyst, PPh3 and trimethylsilyldiazomethane.15 Product 30 was obtained in 61% yield. Notably, the yield from conventional Wittig methylenation is much lower (36%). Allylic C–H oxidation with a combination of SeO2 and tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) occurred smoothly and delivered 31 in 81% yield. The last step is to install the 2-pyridone moiety, which turned out to be nontrivial. We first explored the Fukuyama-Yokoshima 2-pyridone synthesis protocol using 2-(phenylsulfinyl)acetamide 32. After comprehensive explorations, we were able to get the desired product phleghenrine A (1) via one-pot Boc removal, but the yield never went above 10%. Acetamide derivative 33 was used by Trauner and co-workers in their lycoposerramine T total synthesis to build the corresponding 2-pyridone.16 Thus, we explored Trauner’s protocol and were able to achieve a one-pot 2-pyridone synthesis and Boc-deprotection to synthesize phleghenrine A (1) in 51% yield. We further demonstrated that phleghenrine A (1) could be partially reduced to phleghenrine C (3) with Sm in HCl in modest yield.17 Overall, from commercially available starting materials, phleghenrine A (1) and phleghenrine C (3) were prepared in 7 and 8 steps, respectively, which are significantly shorter than the syntheses (23 and 22 steps) reported recently by She and co-workers.5

In summary, concise total syntheses of the structurally novel and scarce lycopodium alkaloids phleghenrine A (1) and phleghenrine C (3) with potent and selective acetylcholinesterase inhibition activities were achieved. The combination of an inverse electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction and a Büchner–Curtius–Schlotterbeck one-carbon insertion enabled an efficient construction of the bicyclo[3.2.2]nonene core of the phleghenrine alkaloids. Other key steps include a Lebel-modified Wittig olefination, allylic C–H oxidation, and Trauner’s modified 2-pyridone synthesis. This current synthetic route could potentially be adapted for phleghenrine analogue synthesis, thus facilitating further biological evaluations of the phleghenrine alkaloids.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH R35 GM128570.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.3c01784.

Experimental procedures and spectra data (PDF)

Author Contributions

X.C. and L.L. ontributed equally

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Dong L.-B.; Wu X.-D.; Shi X.; Zhang Z.-J.; Yang J.; Zhao Q.-S. Phleghenrines A–D and Neophleghenrine A, Bioactive and Structurally Rigid Lycopodium Alkaloids from Phlegmariurus henryi. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 4498–4501. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.-Y. New insights into huperzine A for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012, 33, 1170–1175. 10.1038/aps.2012.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi J.; Hirasawa Y.; Yoshida N.; Morita H. Lyconadin A, a Novel Alkaloid from Lycopodium complanatum. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 5901–5904. 10.1021/jo0103874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritsch P. J.; Gimenez-Nueno I.; Wonilowicz L.; Sarpong R. Copper-Catalyzed [4 + 2] Cycloaddition of 9H-Cyclohepta[b]pyridine-9-one and Electron-Rich Alkenes. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 8717–8723. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b00899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H.; Hou H.; Duan J.; Huang J.; Duan X.; Xie X.; Li H.; She X. Total Syntheses of Phleghenrines A and C: A [4 + 2] Cycloaddition and Ring-Expansion Approach. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 3358–3363. 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cai X.Palladium-Catalyzed Hydroxycyclopropanol Ring-Opening Carbonylative Lactonization to Fused Bicyclic Lactones and Total Synthesis of Phleghenrine Alkaloids, Ph.D. Thesis, Purdue University, 2021. 10.25394/PGS.15078792.v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cai X.; Li L.; Wang Y.-C.; Zhou J.; Dai M.. Concise Total Syntheses of Phleghenrines A and C. ChemRxiv 2023. 10.26434/chemrxiv-2023-8f4rz. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- a Yang Y.; Haskins C. W.; Zhang W.; Low P. L.; Dai M. Divergent Total Syntheses of Lyconadins A and C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3922–3925. 10.1002/anie.201400416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ma D.; Martin B. S.; Gallagher K. S.; Saito T.; Dai M. One-Carbon Insertion and Polarity Inversion Enabled a Pyrrole Strategy to the Total Syntheses of Pyridine-Containing Lycopodium Alkaloids: Complanadine A and Lycodine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 16383–16387. 10.1021/jacs.1c08626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Martin B. S.; Ma D.; Saito T.; Gallagher K. S.; Dai M. Concise Total Synthesis of Complanadine A Enabled by Pyrrole-to-Pyridine Molecular Editing. Synthesis 2023, 10.1055/a-2107-5159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Fujii M.; Nishimura T.; Koshiba T.; Yokoshima S.; Fukuyama T. 2-Pyridone Synthesis Using 2-(Phenylsulfinyl)acetamide. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 232–234. 10.1021/ol303320c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nishimura T.; Unni A. K.; Yokoshima S.; Fukuyama T. Total Syntheses of Lyconadins A–C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3243–3247. 10.1021/ja312065m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candeias N. R.; Paterna R.; Gois P. M. P. Homologation Reaction of Ketones with Diazo Compounds. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2937–2981. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C.-C.; Peddinti R. K. Masked o-Benzoquinones in Organic Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 856–866. 10.1021/ar000194n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg-Douglas N.; Choi Y.; Aquila B.; Huynh H.; Nicewicz D. A. β-Functionalization of Saturated Aza-Heterocycles Enabled by Organic Photoredox Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 3153–3158. 10.1021/acscatal.1c00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.; Truc V.; Riebel P.; Hierl E.; Mudryk B. One-pot synthesis of cyclic enecarbamates from lactam carbamates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 4011–4013. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.04.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Lai C.-H.; Shen Y.-L.; Liao C.-C. Synthesis of Stable Bromo-substituted Masked o-Benzoquinones and their Application to the Synthesis of Bicyclo[2.2.2]octenones. Synlett 1997, 12, 1351–1352. 10.1055/s-1997-1053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lai C.-H.; Shen Y.-L.; Wang M.-N.; Kameswara Rao N. S.; Liao C.-C. Intermolecular Diels-Alder Reactions of Brominated Masked o-Benzoquinones with Electron-Deficient Dienophiles. A Detour Method to Synthesize Bicyclo[2.2.2]octenones from 2-Methoxyphenols. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 6493–6502. 10.1021/jo020171h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Surasani S. R.; Parumala S. K. R.; Peddinti R. K. Diels-Alder reactions of 4-halo masked o-benzoquinones. Experimental and theoretical investigations. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 5656–5668. 10.1039/C4OB00856A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus P.; Seipp C. Concise Synthesis of the Hasubanan Alkaloid (±)-Cepharatine A Using a Suzuki Coupling Reaction To Effect o,p-Phenolic Coupling. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 4870–4871. 10.1021/ol402302k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lebel H.; Guay D.; Paquet V.; Huard K. Highly efficient synthesis of terminal alkenes from ketones. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 3047–3050. 10.1021/ol049085p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xu B.; Liu C.; Dai M. Catalysis-Enabled 13-Step Total Synthesis of (−)-Peyssonnoside A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 19700–19703. 10.1021/jacs.2c09919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartrampf F. W. W.; Furukawa T.; Trauner D. A Conia-Ene-Type Cyclization under Basic Conditions Enables an Efficient Synthesis of (−)-Lycoposerramine R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 893–896. 10.1002/anie.201610021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding R.; Fu J.-G.; Xu G.-Q.; Sun B.-F.; Lin G.-Q. Divergent Total Synthesis of the Lycopodium Alkaloids Huperzine A, Huperzine B, and Huperzine U. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 240–250. 10.1021/jo402419h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.