Abstract

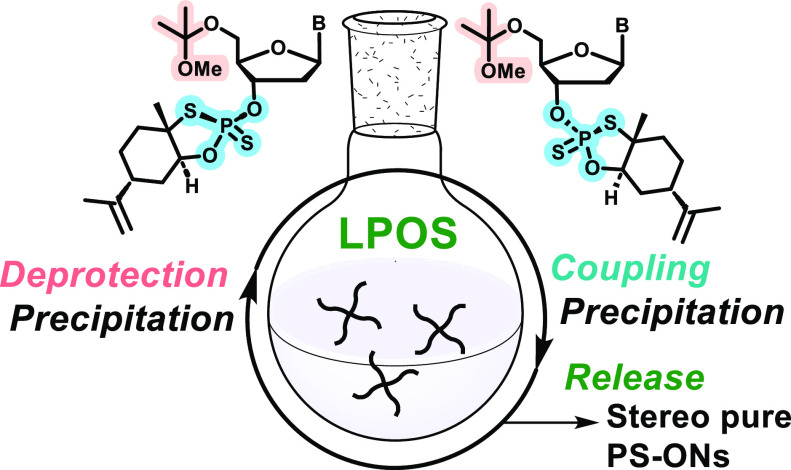

5′-O-(2-Methoxyisopropyl) (MIP)-protected 2′-deoxynucleosides as chiral P(V)-building blocks, based on the limonene-derived oxathiaphospholane sulfide, were synthesized and used for the assembly of di-, tri-, and tetranucleotide phosphorothioates on a tetrapodal pentaerythritol-derived soluble support. The synthesis cycle consisted of two reactions and two precipitations: (1) the coupling under basic conditions, followed by neutralization and precipitation and (2) an acid catalyzed 5′-O-deacetalization, followed by neutralization and precipitation. The simple P(V) chemistry together with the facile 5′-O-MIP deprotection proved efficient in the liquid phase oligonucleotide synthesis (LPOS). Ammonolysis released nearly homogeneous Rp or Sp phosphorothioate diastereomers in ca. 80% yield/synthesis cycle.

Introduction

The importance of therapeutic oligonucleotides (ONs) for treating human diseases is exponentially increasing.1 ON-based treatments have progressed beyond niche applications into areas of therapeutic targets, including hepatitis B and cardiovascular diseases, which require significantly increased amounts of ONs due to the large number of potential patients.2 The growing need for ONs has challenged current ON manufacturing that relies on the automated solid phase ON synthesis (SPOS).3 SPOS has many operational benefits, but its suitability for real-time optimized large-scale processing is limited. This and the recognized sustainability issues are prompting to develop alternative synthetic strategies aiming to greener reagents, improved reagent efficiency, better scalability, and minimized waste streams.4 In this context, the liquid phase-occurring technologies, based on soluble supports, are under investigation, which facilitate isolation of the growing ON intermediates by membrane filtration or precipitation and allow ON chain elongation in real time-optimized and process–suitable reaction conditions.5−7

An additional sustainability challenge of ONs is the growing interest toward enantiopure phosphorothioates.8−15 The proper Rp/Sp-design may not only lead to enhanced efficacy,16 reduced toxicity, and improved delivery of ONs but also to a substantial investment considering the control and regulation of stereochemical integrity and screening of the potential ON drug candidates. Recently, Baran introduced a limonene-based P(V)-chemistry,17,18 an extension of the work by Stec,19−22 which will likely have a significant impact in preparation of enantiopure phosphorothioate ONs. Furthermore, the simple and fast redox-neutral coupling chemistry, based on reactivity of the oxathiaphospholane sulfide moiety (Scheme 1), may suit well for the liquid phase oligonucleotide synthesis (LPOS).23

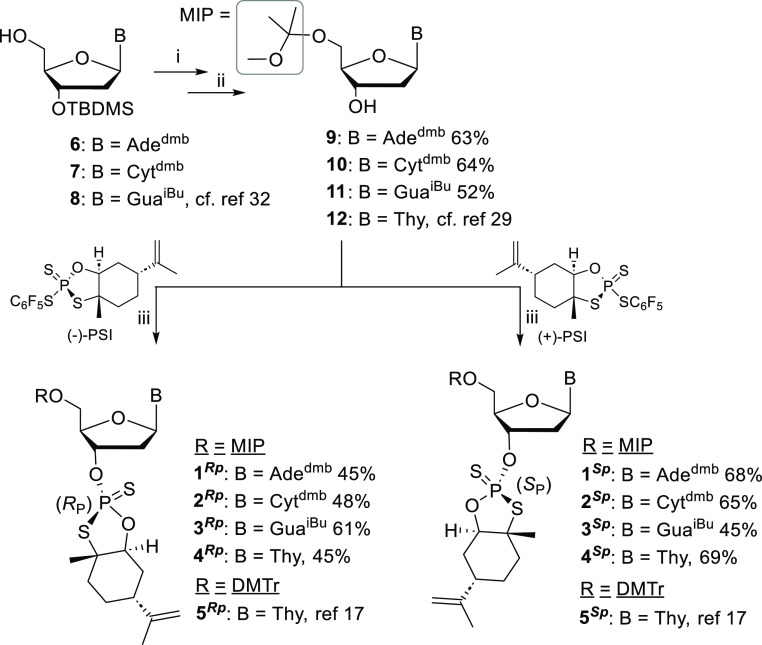

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 3′-O-Ψ-Loaded 5′-O-MIP-2′-deoxynucleosides.

Conditions: (i) 2,2-dimethoxypropane, THF, TsOH·H2O, at r.t. for 3 h; (ii) TBAF·3H2O, THF, at r.t. for 2 h—overnight; (iii) (−)-PSI/(+)-PSI, DBU, MeCN. at r.t. for 2 h.

In the present study, 5′-O-(2-methoxyisopropyl) (MIP)-protected 2′-deoxynucleosides as chiral limonene-based oxathiaphospholane sulfide [named as (+) and (−)-Ψ] building blocks (1–4Rp/Sp, Scheme 1) were synthesized and their applicability for the stereo-controlled LPOS of di-, tri-, and tetranucleotide phosphorothioates using a tetrapodal precipitative soluble support was demonstrated (Scheme 2). This is a preliminary study, which will guide to find procedures for stereo-controlled LPOS of longer ON sequences, but especially of short ON fragments24 or blockmers25,26 that can be ligated to gain full length ON products.

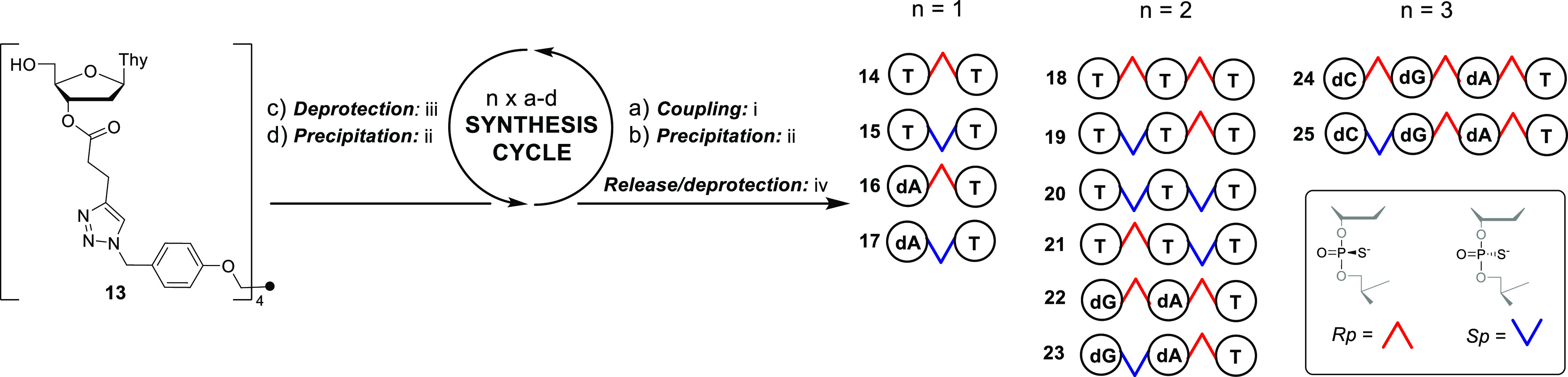

Scheme 2. Stereo-Controlled LPOS of Di-, Tri-, and Tetranucleotide Phosphorothioates.

Conditions: (i) 1.7 equiv 1–4Rp/Sp, 2.7 equiv DBU (equiv/5′-OH group), Py/MeCN (2:3, v/v), for 15–30 min at r.t., followed by addition of acetic acid (3 equiv); (ii) product mixture precipitated in 2-propanol; (iii) 5% DCA in MeOH/DCM, for 3–6 min at r.t., followed by addition of pyridine (2 equiv in comparison to DCA); (iv) 25% aqueous ammonia, for 5 h at 55 °C.

Results and Discussion

3′-O-Ψ-Loaded 5′-O-MIP-2′-deoxynucleosides

4,4′-Dimethoxytrityl (DMTr) is an established 5′-O-protecting group in SPOS27 but causes issues in LPOS.4 The reversibility of the deprotection (Sn1) and its hard reproducibility, being dependent on the scale, concentration, ON sequence and its length, may lead to a marked depurination in solution (primarily in case of DNA). Despite the promising examples, in which scavengers (e.g., silanes28 and thiols24) are used in the detritylation cocktail, we favored MIP as an alternative 5′-O-protecting group.29 The pseudo irreversible acid-catalyzed removal of MIP yields volatile byproducts: acetone and methanol. This, together with a faster reaction rate,30 leads to cleaner products and reduced depurination, which is a clear improvement in comparison to DMTr when used in solution. Synthesis of 3′-O-Ψ-loaded 5′-O-MIP-2′-deoxynucleosides (1Rp–4Rp and 1Sp–4Sp) is described in Scheme 1. Amidine-protected nucleobases have recently been used with the limonene-based P(V)-chemistry in SPOS.18 In our preliminary trials, issues related to premature cleavage of benzoyl at adenine and cytosine were noticed. To ensure better stability, 2,4-dimethylbenzoyl (dmb, ca. 20-fold more stable to alcoholysis than Bz31) was used for 2′-deoxyadosine and 2′-deoxycytidine (dAdmb and dCdmb). Standard isobutyryl was used for 2′-deoxyguanosine (dGiBu), and no N3-protection was needed for thymidine. Dmb protection was performed using a similar protocol than used typically for the benzoylation. MIP introduction was done using the 3′-O-tert-butyldimethlysilyl (TBDMS)-protected 2′-deoxynucleosides (6–832) as subjects for acetalization in a 1:1-mixture of dimethoxypropane and THF in the presence of a catalytic amount of TsOH·H2O (preparation of 6 and 7 described in the Supporting Information). After an extractive work up (or a flash chromatography in case of 9), the 3′-O-TBDMS group was removed, which gave the desired 5′-O-MIP-dAdmb (9), dCdmb (10), and dGiBu (11) in 87, 64, and 52% isolated yield (over two steps), respectively. 5′-O-MIP-T (12) has been published previously.29 The 5′-O-MIP protected 2′deoxynucleosides (9–12) were treated with commercially available (−)- and (+)-Ψ-reagents (1.3 equiv) in the presence of stoichiometric amount of 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) (1.3 equiv), which gave the desired Ψ-loaded products (1Rp–4Rp and 1Sp–4Sp) in 45–69% isolated yields. Due to the modest selectivity between the 5′-O- and 3′-O-acetalization, a complex synthesis route for the building blocks (1Rp–4Rp and 1Sp–4Sp) is described. Work on the optimized direct selective 5′-O-MIP protection is under way, which will reduce the price and carbon footprint of the 5′-O-MIP building blocks, making them real competitive alternatives for DMTr-protected ones.

Stereocontrolled LPOS Using 3′-O-Ψ-Loaded 2′-deoxynucleosides

We have previously used a pentaerytritol-derived branching unit as a soluble support for LPOS.33−37 The protected tetrapodal nucleotide constructs assembled on this unit can be isolated from the reaction media by precipitation in protic antisolvents. The same branching unit, loaded by thymidine and an ester linker is used in the present study (13, Scheme 2). First, we evaluated the compatibility of 5′-O-MIP vs 5′-O-DMTr-protected 3′-O-Ψ-loaded thymidine building blocks (4Rp, 4Sp vs 5Rp, and 5Sp(17)) for the assembly of dithymidine phosphorothioates 14 and 15 (Scheme 2). The efficiency of the coupling and 5′-deprotection was monitored by RP HPLC (a and c/synthesis cycle, Scheme 2. A mixture of pyridine/MeCN (2:3, v/v) was used as a solvent system for the coupling. The building blocks (1–5Rp/Sp) and the tetrapodal nucleotide constructs were readily soluble into this system, and it consisted of recoverable low boiling point volatiles and was tolerated well in the following precipitation step (b/synthesis cycle). Quantitative coupling was obtained in 15 min by using building blocks 4Rp/Sp or 5Rp/Sp (1.7 equiv/5′-OH group, 0.17 mol L–1) in the presence of an excess of DBU (2.7 equiv/5′-OH group, 0.27 mol L–1). No marked change in the coupling efficiency was observed, whether 5′-O-DMTr or MIP-protected building blocks were used (Figure S59). After the coupling, the reaction mixtures were neutralized by addition acetic acid (3 equiv used to neutralize DBU, not pyridine) and precipitated in 2-propanol, being an optimal antisolvent (2-propanol, MeOH and Et2O tested) to provide near quantitative recovery of the tetrapodal nucleotide constructs and efficient removal of the contaminants. For the removal of the 5′-O-DMTr and MIP, the precipitates were dissolved in a mixture of dichloroacetic acid (DCA) (5% for MIP and 20% for DMTr removal) in dichloromethane (DCM)/MeOH (2:1, v/v). Traces of tritylated products could be observed even after a prolonged DCA treatment (2 h, no scavengers used), whereas complete MIP removal was achieved in 3–6 min (Figure S60). The deprotection mixtures were neutralized by addition of pyridine (2 equiv in comparison to DCA) and precipitated in 2-propanol (d/synthesis cycle). The residues were exposed to aqueous ammonia that released dithymidine phosphorothioates 14 and 15 in average 77% yield (calculated from 13 and based on UV-absorbance of aqueous solutions of the products at λ = 260 nm). 31P NMR confirmed the stereochemical purity of the products (Figure 1).

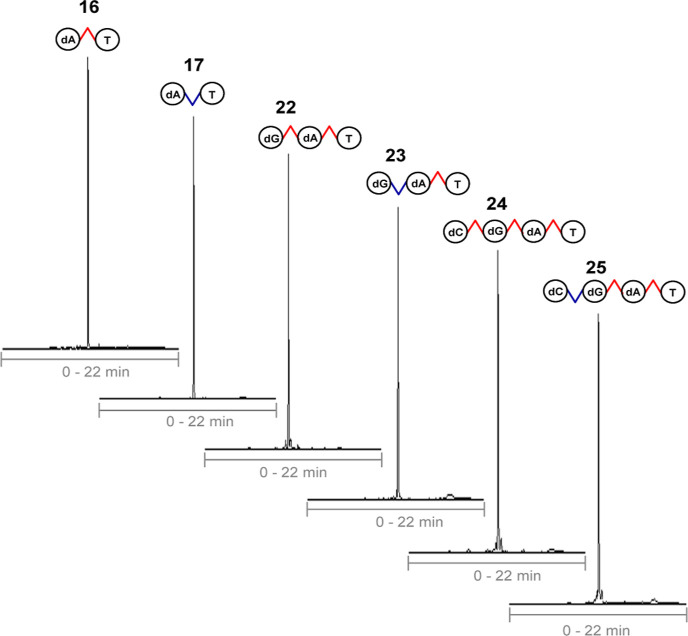

Figure 1.

31P NMR (200 MHz, D2O) spectra 14–25. cf. conditions in General Methods.

Encouraged by the successful MIP-Ψ-combination in LPOS, all stereoisomers of trithymidine phosphorothioates (18–21) and heteromeric di-, tri-, and tetranucleotide phosphorothioates (16, 17, 22–25) were then assembled using 1–4Rp/Sp. As above, RP HPLC was used to monitor each coupling and deprotection. A longer (30 min) coupling time was needed for the 2′-deoxycytidine and guanosine building blocks 2Rp, 2Sp, 3Rp, and 3Sp. Concentrated ammonia released di- (16, 17), tri- (22, 23), and tetranucleotide phosphorothioates (24, 25) in 74–81, 56–66, and 53–59% yields (based on UV-absorbance of the released ONs at λ = 260 nm), respectively, referring to ca. 80% average yield/synthesis cycle. RP HPLC profiles of the crude product mixtures of heteromeric nucleotides are described in Figure 2 (Figure S61). As seen, the limonene-based P(V) chemistry resulted in nearly quantitative couplings that led to efficient chain elongation (>95% purity in each case). The determined overall yields remained lower than expected due to the precipitation efficiency of the soluble support constructs. In each product, 31P NMR was used to confirm the stereochemical purity of the phosphorothioate linkages (Figure 1). In general, 31P NMR works well for this purpose as distinct and resolved 31P resonance signals were observed. Evidence of the stereochemical integrity was provided by exposing the heteronucleotide products (16,17, 22–25) to snake venom phosphodiesterase38−42 that selectively cleaved Rp-isomers of the phosphodiester linkages (Figures S62–S64).

Figure 2.

Examples of RP HPLC profiles of crude product (16, 17, 22–24) mixtures. cf. conditions in General Methods.

Conclusions

5′-O-(2-Methoxypropane-2-yl) (MIP)-protected 2′-deoxynucleosides, 3′-O-loaded by chiral limonene-based oxathiaphospholane sulfide (i.e. Ψ-moiety) (1–4Rp and 1–4Sp), were synthesized and used for stereo-controlled LPOS of di-, tri-, and tetranucleotides on a precipitative soluble support (13). The facile acid-catalyzed removal of MIP and redox-neutral coupling of the Ψ-building blocks proved a useful combination in LPOS. The target nucleotides were obtained in ca. 80% average yield/synthesis cycle that consisted of (1) coupling of the P(V) building blocks (1.7 equiv/5′-OH group) in the presence of DBU (2.7 equiv/5′-OH group), followed by neutralization (AcOH) and precipitation in 2-propanol, and (2) MIP-deprotection using 5% DCA in a mixture of MeOH/DCM, followed by neutralization (pyridine) and precipitation in 2-propanol. 31P NMR spectroscopy confirmed the stereo chemical purity of the products (14–25). In addition, the stereochemical Rp/Sp-integrity (of 16, 17, 22–25) was verified by exposing the nucleotides to snake venom phosphodiesterase that selectively hydrolysed Rp-isomers of the phosphorothioate linkages. This LPOS-compatible procedure may find applications in a scalable preparation of stereopure phosphorothioate ONs. The further development of this methodology may evaluate how long ON sequences can be assembled maintaining still the sufficient efficiency and purity of the ON products. The precipitation efficiency and/or solubility of the tetrapodal ON constructs may need an adjusted nucleobase protecting group scheme.43 An orthogonal linker chemistry would allow preparation of protected blockmers25,26 or fragments,24 which with an appropriate ligation chemistry may be used for the assembly of full-length ON products. It may be emphasized that recent improvements in liquid phase utilize tetra- and pentameric fragments for the convergent assembly of ONs in a kg scale.24 Some benefits of LPOS may be highlighted in the stereo-controlled synthesis. The real time monitoring and controlling of stereochemical integrity of phosphorothioate ONs are limited in the monomer-based assembly on a solid phase. In addition, the end products are contaminated by accumulating diastereomeric byproducts, potentially formed in each coupling during chain elongation. The stereo-controlled LPOS offers better access to real time monitoring of the couplings. With an efficient ligation chemistry of the corresponding pre-characterized and homogenized ON blockmers or segments, assembly of high quality stereo pure ONs may be improved.

Experimental Section

General Methods

NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance 500 and 600 MHz instruments. 31P-NMR spectra of phosphorothioate oligomers were recorded in a mixture of 0.2 M pH 7.4 sodium cacodylate buffer and D2O (4:1, v/v). Mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker microQTOF ESI mass spectrometer. DCM and DMF were dried over 4 Å molecular sieves and MeCN, and MeOH over 3 Å molecular sieves. DBU was dried over CaH2. The homogeneity of the phosphorothioates and the composition of the samples withdrawn from the reaction solutions were analyzed by RP HPLC (an analytical C18 column, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, flow rate 1 mL/min) using a mixture of 50 mM TEAA-buffer and MeCN. The samples from the reaction mixture were eluted by using linear gradient from 40 to 70% MeCN over 20 min. Signals were recorded on a UV detector at a wavelength of 260 nm.

N4-(2,4-Dimethylbenzoyl)-5′-O-(2-methoxypropane-2-yl)-2′-deoxyadenosine (9)

To a solution of 6 (67 g, 135 mmol) in THF (330 mL) and 2,2-dimethoxypropane (330 mL) at 0–5 °C TsOH·H2O (1.28 g, 6.73 mmol, 0.05 equiv) was added. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm up, then stirred at room temperature for 3 h, quenched by addition of triethylamine, and concentrated. The residue was eluted though a short silica gel column (heptane/ethyl acetate, 3:1–2:1, v/v). The product fractions were combined and evaporated to dryness to give 55 g (72%) of 3′-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-N4-(2,4-dimethylbenzoyl)-5′-O-(2-methoxypropane-2-yl)-2′-deoxyadenosine as white solid. The intermediate product (55 g, 97 mmol) was dissolved in THF (550 mL), and the mixture was cooled to 0–5 °C. TBAF·3H2O (31 g, 97 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The reaction solution was concentrated and purified by silica gel column chromatography (n-heptane/ethyl acetate, 1:1, v/v) to give 39 g (63% from 6) of the product (9) as white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.01 (s, 1H), 8.71 (s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 7.50 (d, 1H, J = 7.7 Hz), 7.11 (s, 1H), 7.08 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.52 (t, 1H, J = 6.5 Hz), 5.48 (d, 1H, J = 4.4 Hz), 4.52 (m, 1H), 4.08–3.97 (m, 1H), 3.59 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5, 4.0 Hz), 3.50 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5, 5.4 Hz), 3.00 (s, 3H), 2.91–2.83 (m, 1H, J = 12.9, 6.3 Hz), 2.48–2.39 (m, 4H), 2.32 (s, 3H), 1.25 (s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 167.8, 151.9, 151.7, 150.1, 142.8, 140.2, 136.7, 132.5, 131.5, 128.4, 126.1, 125.3, 99.6, 86.0, 83.5, 70.8, 61.0, 47.8, 39.5, 24.2, 24.1, 20.9, 19.8. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – H]− calcd for C23H28N5O5–, 454.2096; found, 454.2111.

N4-(2,4-Dimethylbenzoyl)-5′-O-(2-methoxypropane-2-yl)-2′-deoxycytidine (10)

To a solution of 7 (58.0 g, 123 mmol) in THF (290 mL) and 2,2-dimethoxypropane (290 mL), TsOH·H2O (2.33 g, 12.26 mmol, 0.1 equiv) was added. The reaction was stirred at 25 °C for 2 h and quenched by addition of NaHCO3 (21 g, 245 mmol, 2.0 equiv) and Et3N (58 mL). The mixture was stirred for 30 min and concentrated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in THF (290 mL) and TBAF·3H2O (64.0 g, 245 mmol, 2.0 equiv) was added. After stirring at 25 °C for 2 h, the mixture was concentrated to dryness. The residue was re-dissolved in DCM (580 mL) and washed with water. The organic phase was separated, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated to dryness. The crude was purified by silica gel chromatography (EtOAc/DCM = 1:2–1:0, v/v) to give 34 g (64%) of the product (10) as white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.08 (s, 1H), 8.34 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.40 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.35 (d, 1H, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.10 (s, 1H), 7.08 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 6.14 (t, 1H, J = 6.0 Hz), 5.36 (d, 1H, J = 4.5 Hz), 4.31–4.17 (m, 1H), 3.98 (q, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz), 3.60 (dd, 1H, J = 10.8, 3.5 Hz), 3.53 (dd, 1H, J = 10.8, 4.1 Hz), 3.12 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 2.35–2.32 (m, 1H), 2.31 (s, 3H), 2.15–2.05 (m, 1H), 1.32 (s, 3H), 1.30 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 169.6, 162.8, 154.4, 144.6, 140.5, 136.4, 132.1, 131.4, 128.3, 126.1, 99.8, 95.6, 86.2, 86.0, 69.9, 60.2, 48.1, 40.9, 24.1, 24.1 20.8, 19.7; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+calcd for C22H30N3O6+, 432.2135; found, 432.2129.

N2-Isobutyryl-5′-O-(2-methoxypropan-2-yl)-2′-deoxyguanosine (11)

To a solution of 8 (175 g, 304 mmol) in THF (875 mL) and 2,2-dimethoxypropane (875 mL), TsOH·H2O (5.78 g, 30.4 mmol, 0.1 equiv) was added. After stirring at 10 °C for 1 h, TEA (175 mL) and THF (875 mL) were added into the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was washed with 5% NaHCO3 aqueous solution and separated. The organic phase was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was triturated with MTBE to give a white solid (128 g). 120 g (185 mmol) of the solid was dissolved in THF (1.2 L), and TBAF·3H2O (116.7 g, 370.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv) was added. After stirring at 6–12 °C for 4 h, DCM (1.8 L) was added into the mixture. The mixture was washed with aqueous 10% NH4Cl solution. The combined organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (ethyl acetate/acetone = 4:1, v/v) to give 11 as off-white solid (61 g, yield: 52%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 12.07 (s, 1H), 11.68 (s, 1H), 8.19 (s, 1H), 6.23 (t, 1H, J = 6.5 Hz), 5.41 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 4.41–4.38 (m, 1H), 3.95–3.92 (m, 1H), 3.51 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5, 4.0 Hz), 3.45 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5, 5.5 Hz), 3.02 (s, 3H), 2.80–2.75 (m, 1H), 2.67–2.62 (m, 1H), 2.34–2.30 (m, 1H), 1.26 (s, 6H), 1.13 (d, 6H, J = 7.0 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 180.1, 154.8, 148.4, 148.1, 137.3, 120.2, 99.6, 85.8, 82.9, 70.6, 60.9, 47.8, 39.5, 34.8, 24.1, 24.1, 18.8, 18.8; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+calcd for C18H28N5O6+, 410.2040; found, 410.2031.

N6-(2,4-Dimethylbenzoyl)-5′-O-(2-methoxypropan-2-yl)-2′-deoxyadenosine Loaded with (−)-Ψ (1Rp)

N6-(2,4-Dimethylbenzoyl)-5′-O-(1-methoxy-1-methylethyl)-2′-deoxyadenosine (9, 0.78 g, 1.72 mmol) and (−)-Ψ-reagent (1.00 g, 2.24 mmol) (dried over P2O5 overnight) were dissolved in anhydrous MeCN (8.0 mL), and DBU (335 μL, 2.24 mmol) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h and filtrated through a short silica gel column by eluting with 1% pyridine in EtOAc. The product fractions were combined and washed with sat. aq NaHCO3 (50 mL), brine (50 mL), and KH2PO4 (50 mL). The organic phase was dried over MgSO4, filtrated, and concentrated under vacuum. The crude product was purified by a silica gel chromatography eluting with a mixture of pyridine and EtOAc (1:99, v/v). The product fractions were combined and evaporated to dryness. The residue was co-evaporated twice with DCM to yield the desired product 1Rp as a white foam (0.51 g, 45%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN): δ 9.23 (br s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 8.36 (s, 1H), 7.53 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.16 (s, 1H), 7.11 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.50 (dd, 1H, J = 6.5 and 6.5 Hz), 5.52 (m, 1H), 5.07 (s, 1H), 4.98 (s, 1H), 4.54 (m, 1H), 4.35 (m, 1H), 3.65 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 3.5 Hz), 3.62 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 4.0 Hz), 3.10 (s, 3H), 3.06 (m, 1H), 2.75 (m, 1H), 2.66 (m, 1H), 2.47 and 2.38 (2× s, 6H), 2.34, 2.12, 2.02–1.94 and 1.85 (m, 6H), 1.83, and 1.70 (2× s, 6H), 1.31 and 1.30 (2× s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CD3CN): δ 167.9, 152.5, 152,5 150.3, 146.4, 142.5, 141.7, 137.7, 133.0, 132.4, 128.6, 126.8, 124.7, 111.8, 100.8, 86.9, 85.1 (J = 8.1 Hz), 84.5, 79.8 (J = 7.7 Hz), 66.8, 61.1, 48.6, 39.4, 38.9 (J = 2.9 Hz), 34.2 (J = 8.8 Hz), 27.9 (J = 15.4 Hz), 24.3, 24.2, 23.5, 22.4, 21.7, 21.0, and 19.8; 31P NMR (202 MHz, CD3CN): δ = 100.65. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C33H45N5O6PS2+, 702,2543; found, 702.2534.

N6-(2,4-Dimethylbenzoyl)-5′-O-(2-methoxypropan-2-yl)-2′-deoxyadenosine Loaded with (+)-Ψ (1Sp)

1Sp was synthesized as above (cf. 1Rp) using 9 and (+)-Ψ-reagent as starting materials. The product 1Sp was obtained as a white foam (0.83 g, 68%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN): δ 9.44 (br s, 1H), 8.62 (s, 1H), 8.33 (s, 1H), 7.50 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.13 (s, 1H), 7.07 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.50 (dd, 1H, J = 6.5 and 6.5 Hz), 5.53 (m, 1H), 5.03 (s, 1H), 4.94 (s, 1H), 4.53 (m, 1H), 4.36 (m, 1H), 3.67 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 3.5 Hz), 3.64 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 4.5 Hz), 3.09 (s, 3H), 3.03 (m, 1H), 2.73 (m, 1H), 2.65 (m, 1H), 2.46 and 2.36 (2× s, 6H), 2.31, 2.11, 2.01–1.94 and 1.85 (m, 6H), 1.81, and 1.70 (2× s, 6H), 1.31 and 1.30 (2× s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CD3CN): δ 167.9, 152.5, 152.4 150.3, 146.3, 142.6, 141.7, 137.6, 133.1, 132.3, 128.5, 126.8, 124.7, 111.7, 100.7, 87.0, 85.2 (J = 5.4 Hz), 84.6, 80.0 (J = 7.8 Hz), 66.7, 61.0, 48.6, 39.4, 38.7 (J = 5.4 Hz), 34.2 (J = 9.3 Hz), 27.9 (J = 15.4 Hz), 24.3, 24.2, 23.5, 22.4, 21.7, 21.0 and 19.8; 31P NMR (202 MHz, CD3CN): δ = 100.16; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C33H45N5O6PS2+, 702,2543; found, 702.2548.

N4-(2,4-Dimethylbenzoyl)-5′-O-(2-methoxypropan-2-yl)-2′-deoxycytidine Loaded with (−)-Ψ (2Rp)

2Rp was synthesized as above (cf. 1Rp) using 10 and (−)-Ψ-reagent as starting materials. The product 2Rp was obtained as a white foam in 48% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, (CD3CN): δ 8.98 (br s, 1H), 8.28 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.48 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.45 (d, 1H, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.16 (s, 1H), 7.13 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.20 (dd, 1H, J = 6.5 and 6.5 Hz), 5.29 (m, 1H), 5.05 (s, 1H), 4.97 (s, 1H), 4.50 (m, 1H), 4.39 (m, 1H), 3.69 (dd, 1H, J = 11.0 and 3.0 Hz), 3.64 (dd, 1H, J = 11.0 and 3.0 Hz), 3.21 (s, 3H), 2.74 (m, 1H), 2.66 (m, 1H), 2.44 and 2.37 (2× s, 6H), 2.35 (m, 2H), 2.33, 2.10, 1.99–1.93 and 1.85 (m, 5H), 1.83, and 1.69 (2× s, 6H), 1.38 and 1.35 (2× s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, (CD3CN): δ 169.9, 163.3, 155.3, 146.4, 145.1, 142.2, 137.7, 132.6, 132.4, 128.5, 126.9, 111.7, 100.9, 96.1, 87.5, 86.9, 85.5 (J = 8.0 Hz), 79.8 (J = 7.6 Hz), 66.8, 60.7, 48.9, 40.5 (J = 3.4 Hz), 39.4, 34.1 (J = 9.1 Hz), 27.8 (J = 15.4 Hz), 24.2, 24.2, 23.5, 22.4, 21.7, 20.9 and 19.7; 31P NMR (202 MHz, (CD3CN): δ 100.62; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C32H45N3O7PS2+, 678,2431; found, 678.2439.

N4-(2,4-Dimethylbenzoyl)-5′-O-(2-methoxypropan-2-yl)-2′-deoxycytidine Loaded with (+)-Ψ-Reagent (2Sp)

2Sp was synthesized as above (cf. 1Rp) using 10 and (+)-Ψ-reagent as starting materials. The product 2Sp was obtained as a white foam in 65% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, (CD3)2CO): δ 9.65 (br s, 1H), 8.39 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.59 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.48 (d, 1H, J = 3.5 Hz), 7.15 (s, 1H), 7.13 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.30 (dd, 1H, J = 6.5 and 6.5 Hz), 5.39 (m, 1H), 5.05 (s, 1H), 4.97 (s, 1H), 4.55 (m, 1H), 4.46 (m, 1H), 3.79 (dd, 1H, J = 11.0 and 3.0 Hz), 3.75 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 3.0 Hz), 3.26 (s, 3H), 2.75 (m, 1H), 2.69 (m, 1H), 2.47 and 2.36 (2× s, 6H), 2.41 (m, 1H), 2.33, 2.14, 2.08–1.98 and 1.90 (m, 6H), 1.82 and 1.73 (2× s, 6H), 1.42 and 1.40 (2× s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, (CD3)2CO): δ 169.2, 162.9, 154.3, 145.6, 144.3, 141.2, 137.1, 132.2, 131.8, 128.0, 126.3, 111.2, 100.3, 95.5, 86.8, 86.1, 85.1 (J = 5.0 Hz), 79.5 (J = 7.7 Hz), 65.9, 60.2, 48.3, 39.9 (J = 5.9 Hz), 38.9, 33.6 (J = 9.1 Hz), 27.4 (J = 15.5 Hz), 23.8, 23.7, 23.1, 21.9, 21.1, 20.4 and 19.3; 31P NMR (202 MHz, (CD3)2CO): δ = 99.80; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C32H45N3O7PS2+, 678.2431; found, 678.2445.

N2-Isobutyryl-5′-O-(2-methoxypropan-2-yl)-2′-deoxyguanosine Loaded with (−)-Ψ (3Rp)

3Rp was synthesized as above (cf. 1Rp) using 11 and (−)-Ψ-reagent as starting materials. The product 3Rp was obtained as a white foam in 61% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN): δ 11.90 (br s, 1H), 9.35 (br s, 1H), 7.93 (s, 1H), 6.24 (dd, 1H, J = 7.0 and 7.0 Hz), 5.48 (m, 1H), 5.06 (s, 1H), 4.96 (s, 1H), 4.50 (m, 1H), 4.31 (m, 1H), 3.67 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 4.0 Hz), 3.60 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 4.5 Hz), 3.10 (s, 3H), 3.04 (m, 1H), 2.70 (septet, 1H, J = 6.5 Hz), 2.68–2.65 (m, 2H, H2″ and CH); 2.34, 2.06, 2.00–1.91, and 1.84 (m, 6H), 1.81 and 1.70 (2× s, 6H), 1.32 and 1.31 (2× s, 6H), 1.23 (d, 6H, J = 6.5 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CD3CN): δ = 180.4, 155.9, 149.1, 148.6, 146.4, 138.1, 121.8, 111.7, 100.8, 87.0, 85.1 (J = 7.3 Hz), 84.4, 79.9 (J = 7.6 Hz), 66.8, 61.1, 48.6, 39.4, 38.3 (J = 3.3 Hz), 36.3, 34.2 (J = 8.8 Hz), 27.9 (J = 15.5 Hz), 24.3, 24.2, 23.55, 22.4, 21.7, 18.8 and 18.7; 31P NMR (202 MHz, CD3CN): δ = 100.85; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C28H43N5O7PS2+, 656.2336; found, 656.2326.

N2-Isobutyryl-5′-O-(2-methoxypropan-2-yl)-2′-deoxyguanosine Activated with (+)-Ψ (3Sp)

3Sp was synthesized as above (cf. 1Rp) using 11 and (+)-Ψ-reagent as starting materials. The product 3Sp was obtained as a white foam in 45% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN): δ 12.01 (br s, 1H), 9.59 (br s, 1H), 7.95 (s, 1H), 6.25 (dd, 1H, J = 7.0 and 7.0 Hz), 5.46 (m, 1H), 5.03 (s, 1H), 4.93 (s, 1H), 4.48 (m, 1H), 4.31 (m, 1H), 3.68 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 4.0 Hz), 3.62 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 4.5 Hz), 3.11 (s, 3H), 2.99 (m, 1H), 2.72 (septet, 1H, J = 6.5 Hz), 2.68–2.64 (m, 2H), 2.31, 2.08, 2.01–1.91, and 1.84 (m, 6H), 1.80 and 1.70 (2× s, 6H), 1.32 and 1.31 (2× s, 6H), 1.22 (d, 6H, J = 6.5 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CD3CN): δ 180.5, 155.9, 149.0, 148.6, 146.4, 138.0, 121.7, 111.7, 100.8, 87.1, 85.3 (J = 5.4 Hz), 84.6, 80.2 (J = 8.1 Hz), 66.7, 61.0, 48.6, 39.4, 38.4 (J = 5.3 Hz), 36.3, 34.2 (J = 8.8 Hz), 27.9 (J = 15.4), 24.3, 24.2, 23.5, 22.4, 21.7, 18.8 and 18.8; 31P NMR (202 MHz, CD3CN): δ = 100.39; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C28H43N5O7PS2+, 656.2336; found, 656.2333.

5′-O-(2-Methoxypropan-2-yl)-thymidine Loaded with (−)-PSI-Reagent (4Rp)

4Rp was synthesized as above (cf. 1Rp) using 12 (−)-PSI-regent as starting materials. The product 4Rp was obtained as a white foam in 45% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.63 (d, 1H, J = 1.50 Hz); 6.45 (dd, 1H, J = 9.0 and 5.5 Hz), 5.40 (m, 1H), 5.10 (s, 1H), 4.94 (s, 1H), 4.50 (m, 1H), 4.38 (m, 1H), 3.75 (dd, 1H, J = 11.0 and 2.5 Hz), 3.69 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5 and 2.0 Hz), 3.27 (s, 3H), 2.63 (m, 1H), 2.53 (m, 1H), 2.36 (m, 1H), 2.24 (m, 1H), 2.16 (m, 1H), 2.01–1.79 (m, 4H); 1.96 (d, 3H, J = 1.0 Hz), 1.83 (s, 3H), 1.73 (s, 3H), 1.43 (s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.2, 150.0, 144.7, 135.3, 112.2, 111.1, 100.5, 86.1, 84.8 (J = 12.5 Hz), 84.6, 79.9 (J = 7.4 Hz), 66.0, 60.9, 49.0, 39.4 (J = 4.4 Hz), 38.8, 33.6 (J = 9.6 Hz), 27.7 (15.5 Hz), 24.5, 24.4, 23.4, 22.6, 21.8, 12.5; 31P NMR (202 MHz, CDCl3): δ 101.72 ppm. ESI+-HRMS m/z: [M + Na]+ calcd for C24H37N2O7PS2Na+, 583.1672; found, 583.1689.

5′-O-(2-Methoxypropan-2-yl)-thymidine Loaded with (+)-PSI-Reagent (4Sp)

4Sp was synthesized as above (cf. 1Rp) using 12 and (+)-PSI-reagent as starting materials. The product 4Sp was obtained as a white foam in 69% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.38 (s, 1H), 7.61 (d, 1H, J = 1.0 Hz), 6.45 (dd, 1H, J = 9.0 and 5.5 Hz), 5.39 (m, 1H), 5.07 (s, 1H), 4.91 (s, 1H), 4.48 (m, 1H), 4.37 (m, 1H), 3.75 (dd, 1H, J = 11.0 and 2.50 Hz), 3.68 (dd, 1H, J = 11.0 and 2.5 Hz), 3.26 (s, 3H), 2.60 (m, 1H), 2.50 (m, 1H), 2.30 (m, 1H), 2.22–2.12 (m, 2H), 1.99, 1.91–1.83 and 1.77 (m, 4H), 1.94 (d, 3H, J = 0.50 Hz), 1.81 (s, 3H), 1.71 (s, 3H), 1.41 (s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.3, 150.2, 144.7, 135.3, 112.2, 111.2, 100.5, 86.1, 84.9, 84.8 (J = 14.5 Hz), 80.1 (J = 7.3 Hz), 65.8, 60.8, 49.0, 39.1 (J = 7.6 Hz), 38.8, 33.7 (J = 9.2 Hz), 27.8 (J = 15.9 Hz), 24.5, 24.4, 23.4, 22.7, 21.7, 12.5; 31P NMR (202 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 101.59 ppm. ESI+-HRMS m/z: [M + Na]+ calcd for C24H37N2O7PS2Na+, 583.1672; found, 583.1689.

General Procedure for LPOS

a/Synthesis Cycle

The tetrapodal nucleoside construct (cf. 13, 50 μmol), the Ψ -activated 2′-deoxynucleoside building block (1–4Rp/Sp, 0.33 mmol), and DBU (83 μL, 0.54 mmol) were dissolved in a mixture of pyridine/MeCN (2:3, v/v, 1.9 mL) under nitrogen. The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 min–1 h (at r.t.) and then acetic acid (36 μL, 0.60 mmol) was added.

b/Synthesis Cycle

The coupling mixture was added dropwise to cold (4 °C) 2-propanol (30 mL), resulting in white precipitation. The mixture was centrifugated, the 2-propanol supernatant was decanted off, and the precipitate was dried under vacuum.

c/Synthesis Cycle

The precipitate was dissolved in a mixture of DCA-dichloromethane/methanol (0.12:2:1, v/v, 1.6 mL). The mixture was stirred for 3–6 min (at r.t.) and neutralized by addition of pyridine (50 μL, 2 equiv compared to DCA).

d/Synthesis Cycle

The deprotection mixture was added dropwise to cold (4 °C) 2-propanol (30 mL), resulting in white precipitation. The mixture was centrifugated, the 2-propanol supernatant was decanted off, and the precipitate was dried under vacuum. By using this synthesis cycle and repeating it (n = 2 and 3), white powder of protected tetrapodal di-, tri-, and tetranucleotides were obtained in 95–98, 81–89, and 76–86% yields, respectively.

Release/Deprotection

The powders were dissolved in concentrated (25%) aqueous ammonia (2 mL) and the mixtures were incubated at 55 °C for 3 h (14, 15, 18–21) or overnight (16, 17, 22–25). The precipitated traces of the soluble support, i.e., tetrakis[(4-{[4-(3-amino-3-oxopropyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl-]methyl}phenoxy)-methyl]methane,28 was filtered off and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in water, washed with ethyl acetate, and subjected then to a RP HPLC analysis (Figure 2). The yields of the nucleotides (14–17: 74–81%, 18–23: 56–66% and 24 and 25: 59 and 53%) were determined according to UV-absorbance at λ = 260 nm. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M – H]−: 14 and 15: calcd, 561.1062; found, 561.1067 and 561.1069, 16 and 17: calcd, 570.1178; found, 570.1169 and 570.1179, 18–21: calcd, 881.1294; found, 881.1295, 881.1291, 881.1298 and 881.1298, in this order, 22 and 23: calcd, 915.1474; found, 915.1494 and 915.1509, 24 and 25: calcd, 1220.1719; found, 1220.1702 and 1220.1712; 31P NMR (200 MHz, D2O) of 14–25: Figure 1.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis

To confirm the stereochemical integrity of the phosphodiester linkages, nucleotides 16, 17, 22–25 were exposed to phosphodiesterase I extracted from venom of Crotalus admanteus (svPDE). The enzymatic reactions were carried out in sealed tubes immersed in an aluminum dry block heater. The enzymatic hydrolysis was followed in a 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer (234 μL) at pH 8.5 and at 37 °C in the presence of svPDE (60 μL) and 0.15 mM MgCl2 (4.5 μL). The initial phosphorothioate substrate concentration was 0.33 mM. The aliquots (50 μL) withdrawn from the reaction solution (300 μL) were diluted with a 100 μL mixture of 50 mM TEAA buffer and filtered with minisart RC4 filters (0.2 μm). The composition of the samples was analyzed by RP-HPLC (Figures S61–S63).

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was developed with the support of the ACS Green Chemistry Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable (http://www.acsgcipr.org). The ACS GCI is a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to catalyze and enable the implementation of green and sustainable chemistry throughout the global chemistry enterprise. The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable, composed of pharmaceutical and related industries, was established in 2005 to encourage innovation while catalyzing the integration of green chemistry and green engineering in the pharmaceutical industry. The activities of the Roundtable reflect its member’s shared belief that the pursuit of green chemistry and engineering is imperative for business and environmental sustainability.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.3c01006.

1H and 13C NMR data for 1–4Rp/Sp, 9–11; synthesis and characterization data for 6 and 7; and examples of RP HPLC profiles of the coupling reactions, crude products, and of the enzymatic degradation of 16, 17, and 22–25 (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kulkarni J. A.; Witzigmann D.; Thomson S. B.; Chen S.; Leavitt B. R.; Cullis P. R.; van der Meel R. The current landscape of nucleic acid therapeutics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 630–643. 10.1038/s41565-021-00898-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moumne L.; Marie A. C.; Crouvezier N. Oligonucleotide Therapeutics: From Discovery and Development to Patentability. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 260. 10.3390/pharmaceutics14020260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaucage S. L.; Caruthers M. H. Deoxynucleoside phosphoramidites—A new class of key intermediates for deoxypolynucleotide synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 1859–1862. 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)90461-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B. I.; Antia F. D.; Brueggemeier S. B.; Diorazio L. J.; Koenig S. G.; Kopach M. E.; Lee H.; Olbrich M.; Watson A. L. Sustainability challenges and opportunities in oligonucleotide manufacturing. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 49–61. 10.1021/acs.joc.0c02291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina A. G.; Sanghvi Y. S. Liquid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis: Past, present, and future predictions. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2019, 77, e82 10.1002/cpnc.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnberg H. Synthesis of oligonucleotides on a soluble support. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 1368–1387. 10.3762/bjoc.13.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama S.; Hirai K.. Synthesis of Therapeutic Oligonucleotides; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd, 2018; pp 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Almer H.; Stawinski J.; Strömberg R. Synthesis of stereochemically homogeneous oligoribonucleoside all-RP-phosphorothioates by combining H-phosphonate chemistry and enzymatic digestion. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1994, 1459–1460. 10.1039/c39940001459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheruvallath Z. S.; Sasmor H.; Cole D. L.; Ravikumar V. T. Influence of diastereomeric ratios of deoxyribonucleoside phosphoramidites on the synthesis of phosphorothioate oligonucleotides. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2000, 19, 533–543. 10.1080/15257770008035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka N.; Wada T.; Saigo K. Diastereocontrolled synthesis of dinucleoside phosphorothioates using a novel class of activators, dialkyl(cyanomethyl)ammonium tetrafluoroborates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 4962–4963. 10.1021/ja017275e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak L. A.; Gora M.; Bukowiecka-Matusiak M.; Mourgues S.; Pratviel G.; Meunier B.; Stec W. J. The P-stereocontrolled synthesis of PO/PS-chimeric oligonucleotides by incorporation of dinucleoside phosphorothioates bearing an O-4-nitrophenyl phosphorothioate protecting group. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2005, 2924–2930. 10.1002/ejoc.200400910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oka N.; Yamamoto M.; Sato T.; Wada T. Solid-phase synthesis of stereoregular oligodeoxyribonucleoside phosphorothioates using bicyclic oxazaphospholidine derivatives as monomer units. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16031–16037. 10.1021/ja805780u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto N.; Oka N.; Sato T.; Wada T. Stereocontrolled solid-phase synthesis of oligonucleoside H-phosphonates by an oxazaphospholidine approach. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 496–499. 10.1002/anie.200804408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W. B.; Migawa M. T.; Vasquez G.; Murray H. M.; Nichols J. G.; Gaus H.; Berdeja A.; Lee S.; Hart C. E.; Lima W. F.; Swayze E. E.; Seth P. P. Synthesis, biophysical properties and biological activity of second generation antisense oligonucleotides containing chiral phosphorothioate linkages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 13456–13468. 10.1093/nar/gku1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamuri S.; Liu D.; Eltepu L.; Liu B.; Reboton L. J.; Preston R.; Bradshaw C. W. Identification of a tricyclic PIII chiral auxiliary for solid-supported synthesis of stereopure phosphorothioate-containing oligonucleotides. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1298–1303. 10.1002/cbic.201900631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto N.; Butler D. C. D.; Svrzikapa N.; Mohapatra S.; Zlatev I.; Sah D. W. Y.; Meena; Standley S. M.; Lu G.; Apponi L. H.; Frank-Kamenetsky M.; Zhang J. J.; Vargeese C.; Verdine G. L. Control of phosphorothioate stereochemistry substantially increases the efficacy of antisense oligonucleotides. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 845–851. 10.1038/nbt.3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouse K. W.; deGruyter J. N.; Schmidt M. A.; Zheng B.; Vantourout J. C.; Kingston C.; Mercer S. E.; Mcdonald I. M.; Olson R. E.; Zhu Y.; Hang C.; Zhu J.; Yuan C.; Wang Q.; Park P.; Eastgate M. D.; Baran P. S. Unlocking P(V): Reagents for chiral phosphorothioate synthesis. Science 2018, 361, 1234–1238. 10.1126/science.aau3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Knouse K. W.; Qiu S.; Hao W.; Padial N. M.; Vantourout J. C.; Zheng B.; Mercer S. E.; Lopez-Ogalla J.; Narayan R.; Olson R. E.; Blackmond D. G.; Eastgate M. D.; Schmidt M. A.; McDonald I. M.; Baran P. S. A P(V) platform for oligonucleotide synthesis. Science 2021, 373, 1265–1270. 10.1126/science.abi9727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stec W. J.; Grajkowski A.; Koziolkiewicz M.; Uznanski B. Novel route to oligo(deoxyribonucleoside phosphorothioates). Stereocontrolled synthesis of P-chiral oligo(deoxyribonucleoside phosphorothioates). Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19, 5883–5888. 10.1093/nar/19.21.5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stec W. J.; Grajkowski A.; Kobylanska A.; Karwowski B.; Koziolkiewicz M.; Misiura K.; Okruszek A.; Wilk A.; Guga P.; Boczkowska M. Diastereomers of nucleoside 3’–O-(2-thio-1,3,2-oxathia(selena)phospholanes): Building blocks for stereocontrolled synthesis of oligo(nucleoside phosphorothioate)s. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 12019–12029. 10.1021/ja00154a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stec W. J.; Karwowski B.; Boczkowska M.; Guga P.; Koziołkiewicz M.; Sochacki M.; Wieczorek M. W.; Błaszczyk J. Deoxyribonucleoside 3’-O-(2-thio- and 2-oxo-spiro-4,4-pentamethylene-1,3,2-oxathiaphospholane)s: Monomers for stereocontrolled synthesis of oligo(deoxyribonucleoside phosphorothioate)s and chimeric PS/PO oligonucleotides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 7156–7167. 10.1021/ja973801j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guga P.; Stec W. J. Synthesis of phosphorothioate oligonucleotides with stereodefined phosphorothioate linkages. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2003, 14, 4. 10.1002/0471142700.nc0417s14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virta P. More versatile synthesis of oligonucleotides. Science 2021, 373, 1196–1197. 10.1126/science.abk3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Kiesman W. F.; Yan W.; Jiang H.; Antia F. D.; Yang J.; Fillon Y. A.; Xiao L.; Shi X. Development of kilogram-scale convergent liquid-phase synthesis of oligonucleotides. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 2087–2110. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c01756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kungurtsev V.; Lönnberg H.; Virta P. Synthesis of protected 2′-O-deoxyribonucleotides on a precipitative soluble support: a useful procedure for the preparation of trimer phosphoramidites. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 105428–105432. 10.1039/c6ra22316h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suchsland R.; Appel B.; Virta P.; Müller S. Synthesis of fully protected trinucleotide building blocks on a disulphide-linked soluble support. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 3892–3896. 10.1039/d0ra10941j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seliger H. Protection of 5′-hydroxy functions of nucleosides. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2000, 00, 2.3.1. 10.1002/0471142700.nc0203s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creusen G.; Akintayo C. O.; Schumann K.; Walther A. Scalable one-pot-liquid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis for model network hydrogels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16610–16621. 10.1021/jacs.0c05488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina A. G.; Kungurtsev V.; Virta P.; Lönnberg H. Acetylated and methylated β-cyclodextrins as viable soluble supports for the synthesis of short 2′-oligodeoxyribo-nucleotides in solution. Molecules 2012, 17, 12102–12120. 10.3390/molecules171012102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z.; Koivikko H.; Oivanen M.; Heinonen P. Tuning the stability of alkoxyisopropyl protection groups. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 746–751. 10.3762/bjoc.15.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köster H.; Kulikowski K.; Liese T.; Heikens W.; Kohli V. N-Acyl protecting groups for deoxynucleosides. Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 363–369. 10.1016/s0040-4020(01)92022-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Löschner T.; Engels J. One pot Rp-diastereoselective synthesis of dinucleoside methylphosphonates using methyldichlorophosphine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 5587–5590. 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)93806-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kungurtsev V.; Laakkonen J.; Molina A. G.; Virta P. Solution-phase synthesis of short oligo-2-deoxyribonucleotides by using clustered nucleosides as a soluble support. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 6687–6693. 10.1002/ejoc.201300864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kungurtsev V.; Virta P.; Lönnberg H. Synthesis of short oligodeoxyribonucleotides by phosphotriester chemistry on a precipitative tetrapodal Support. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 7886–7890. 10.1002/ejoc.201301352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez Molina A.; Jabgunde A. M.; Virta P.; Lönnberg H. Solution phase synthesis of short oligoribonucleotides on a precipitative tetrapodal support. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 2279–2285. 10.3762/bjoc.10.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina A. G.; Jabgunde A. M.; Virta P.; Lönnberg H. Assembly of short oligoribonucleotides from commercially available building blocks on a tetrapodal soluble support. Curr. Org. Synth. 2015, 12, 202–207. 10.2174/1570179411666141120215703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jabgunde A. M.; Molina A. G.; Virta P.; Lönnberg H. Preparation of a disulfide-linked precipitative soluble support for solution-phase synthesis of trimeric oligodeoxyribonucleotide 3′-(2-chlorophenylphosphate) building blocks. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 1553–1560. 10.3762/bjoc.11.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein F. Nucleoside phosphorothioates. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1985, 54, 367–402. 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein F. Phosphorothioate analogues of nucleotides—Tools for the investigation of biochemical processes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1983, 22, 423–439. 10.1002/anie.198304233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frey P. A. Chiral phosphorothioates: stereochemical analysis of enzymatic substitution at phosphorus. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1989, 62, 119–201. 10.1002/9780470123089.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariko K.; Sobol R. W. Jr.; Suhadolnik L.; Li S. W.; Reichenbach N. L.; Suhadolnik R. J.; Charubala R.; Pfleiderer W. Phosphorothioate analogs of 2’,5’-oligoadenylate. Enzymatically synthesized 2’,5’-phosphorothioate dimer and trimer: unequivocal structural assignment and activation of 2’,5’-oligoadenylate-dependent endoribonuclease. Biochemistry 1987, 26, 7127–7135. 10.1021/bi00396a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgers P. M. J.; Eckstein F. Diastereomers of 5’-O-adenosyl 3’-O-uridyl phosphorothioate: chemical synthesis and enzymic properties. Biochemistry 1979, 18, 592–596. 10.1021/bi00571a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride L. J.; Kierzek R.; Beaucage S. L.; Caruthers M. H. Nucleotide chemistry. 16. Amidine protecting groups for oligonucleotide synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 2040–2048. 10.1021/ja00268a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.