Abstract

Triphenylmethyl (trityl, Ph3C•) radicals have been considered the prototypical carbon-centered radical since their discovery in 1900. Tris(4-substituted)-trityls [(4-R-Ph)3C•] have since been used in many ways due to their stability, persistence, and spectroscopic activity. Despite their widespread use, existing synthetic routes toward tris(4-substituted)-trityl radicals are not reproducible and often lead to impure materials. We report here robust syntheses of six electronically varied (4-RPh)3C•, where R = NMe2, OCH3, tBu, Ph, Cl, and CF3. The characterization reported for the radicals and related compounds includes five X-ray crystal structures, electrochemical potentials, and optical spectra. Each radical is best accessed using a stepwise approach from the trityl halide, (RPh)3CCl or (RPh)3CBr, by controllably removing the halide with subsequent 1e– reduction of the trityl cation, (RPh)3C+. These syntheses afford consistently crystalline trityl radicals of high purity for further studies.

Introduction

Carbon-centered radicals (CCRs) are fundamental to a suite of chemical reactions, including the homolytic cleavage and formation of C–H, C–OH, or C–X bonds. Radical polymerization and halogenation reactions have been studied for over a century and are taught to entry-level organic chemistry students.1 In organic and biological systems, C–H bonds are increasingly found to react through radical mechanisms,2 including H-atom transfer (HAT) and multisite coupled proton-electron transfer (MS-CPET).3 Organic chemists leverage the selectivity of CCRs to afford complex chemical scaffolds and regioselective functionalization.4−12 In biological systems, oxidations of C–H bonds by iron-oxo active sites in heme and nonheme enzymes proceed via CCR intermediates,13−18 and multiple CCRs are involved in the various chemistry of radical-SAM and vitamin B-12 enzymes,19−23 to name a few. Despite the wide interest, the fundamental reactivity of CCRs can be difficult to study due to their short lifetimes and high propensity for oxidation, dimerization, and other reactivity.24

The triphenylmethyl (trityl) radical is a valuable CCR reagent due to its kinetic persistence, spectroscopic addressability, and relatively high thermodynamic stability (for a CCR). The unsubstituted trityl radical (Ph3C•) was first isolated by Gomberg in 190025 and exists as an equilibrium in solution between the free radical and the quinoid dimer.26 Dimerization to the quinoid (known colloquially as head-to-tail) can be hindered by substitution at the para position of the three phenyl rings, resulting in a monomeric tris(4-substituted)trityl radical [(4-RPh)3C•] ([R]•).27,28 Head-to-head dimerization of substituted trityl radicals has been observed for highly substituted trityls (due to dispersion forces)29 but has not been reported for simple tris(4-substituted)trityl radicals, even down to low temperatures.

Despite Gomberg writing in his initial publication that “I wish to reserve the field for myself”,25 substituted trityl radicals have been widely studied and used. Among their reactivity studies are determinations of absolute rates for HAT reactions with thiophenols30 and transition metal hydrides,31 studies of biologically relevant hydroxylation,32 their use as antioxidants,33 and as an H-atom relay.34,35 Outside of their reactivity, substituted trityls are used as dopants in molecular semiconductors,36 molecular electronics,24,37 and as spin polarization agents for dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP).38

Inspired by previous work, our group set out to utilize trityl radicals to study the kinetics of HAT at CCRs. Our studies have required high-purity trityl radicals, free from the halide starting materials Ar3CCl or Ar3CBr, the trityl cations and anions (Ar3C+ and Ar3C–), and the reduced triarylmethanes (Ar3CH). Given the large breadth of literature on the formation of trityl radicals, we were surprised to find that we were unable to cleanly reproduce the synthesis of any (4-XPh)3C•. All our attempts led to material that was impure by UV–vis and/or NMR spectroscopies. The most common reported procedures involve reducing the trityl halide by a heterogeneous metal reductant, such as Ag, Cu, or Zn. Often, few synthetic details are provided, such as the size of metal particles used, equivalents, and concentration. “Optimized” syntheses for (4-tBuPh)3C• were reported as using varying amounts of Cu or Zn for various times, none of which resulted in pure radicals in our hands. Our concerns are highlighted by the variety of optical extinction coefficients found in the literature for the same trityl radical. A reproducible approach to clean (4-XPh)3C• radicals would increase accessibility and utility of these reagents for many purposes.

We report here the syntheses of six electronically varied trityl radicals [(4-RPh)3C•] where R = Me2N, MeO, tBu, Ph, Cl, and CF3. These syntheses take advantage of the multiple pathways to form trityl radicals (Scheme 1). Our criteria for these synthetic approaches include (1) relatively detailed procedures for reproducibility, (2) isolable crystalline material for storage and handling, and (3) structural characterization, which can corroborate/compliment spectroscopic studies between solution and solid states.

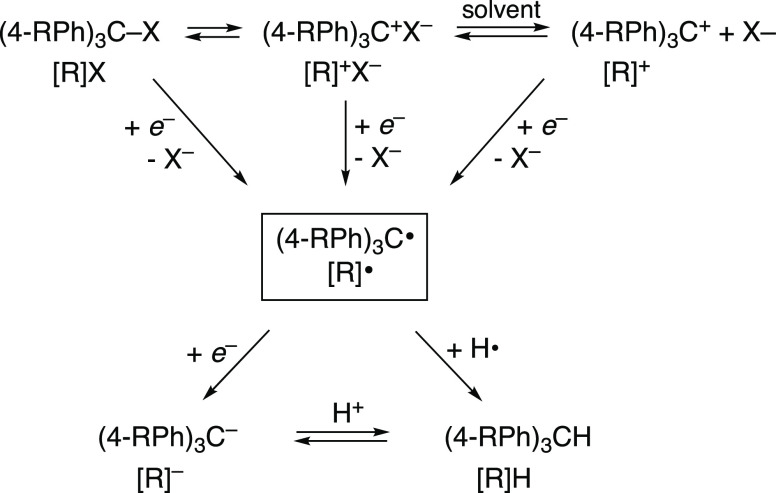

Scheme 1. 4-Substituted Trityl Radicals ([R]•) and Related Compounds.

This paper is designed as a primer for those interested in utilizing trityl radicals as reagents. As such, we discuss general synthetic challenges, common impurities, and overall structural and spectroscopic characterization in this main text. Detailed synthetic procedures and further commentary are available in the SI. For the sake of clarity, trityl species will be denoted by the R group and the oxidation state or substituent of the central methane: [R]•/+/–/H/X, e.g., [tBu]H = (4-tBuPh)3CH and [MeO]+ = (4-MeOPh)3C+.

Results and Discussion

Synthetic Challenges

Trityl radical syntheses are scattered across many corners of the literature, yet there are no standardized “best practices” for synthesis and characterization of the para-substituted trityls. Decades-old preglovebox syntheses involved complicated glassware setups and harsh conditions (e.g., boiling mercury) to generate trityl radicals. Characterization was typically limited to UV–vis spectroscopy, or EPR, or elemental analysis of decomposition products. More recently, heterogeneous metal reductions of trityl halides have been utilized to generate solutions of trityl radicals that were used immediately for reactivity studies. In these cases, complete conversion of the starting material was assumed to calculate the optical molar absorptivity of the trityl solutions, ε. The concentrations were in some cases supported by quantitative EPR, which can be unreliable. For instance, even for the cleanest syntheses that we have found in the literature, the molar extinction coefficient for [tBu]• (εM, M–1 cm–1) has been reported as 750,31 825,35 and 850.39

A primary challenge of generating trityl radicals is the variety of closely related stable species that can be present in a reaction solution at any time, as shown in Scheme 1. For example, the trityl halides [R]X can readily dissociate forming ion pairs of the carbocation and halide anion, [R]+X–, even in relatively nonpolar solvents such as toluene.40−43 This is especially true for derivatives with more electron-donating para substituents (MeO and Me2N). The dissociation of ion pairs to the solvent-separated carbocation [R]+ depends on many factors, such as carbocation Lewis acidity and solvent polarity,44 and it can impact reactivity as discussed below. Following previously reported preparations for para-substituted trityl radicals, we found the carbocations to be a very common impurity as indicated by their intense absorbance in the visible spectrum.

On the other hand, heterogeneous metals such as Cu or Zn can over-reduce trityl halides to the carbanion [R]−. In the presence of any proton source (such as residual water), the carbanions quickly form triphenylmethanes [R]H, which are detectable by 1H NMR spectroscopy. While carbanions are stabilized by electron-withdrawing substituents, we surprisingly observed triphenylmethane formation by NMR in the preparation for trityl radicals with relatively more electron-donating groups such as para-methoxy.

An additional concern with heterogeneous reductants is that their particle size has a drastic effect on the reaction times and formation of impurities. The use of stronger single electron reductants (e.g., KC8) with trityl halides can easily over-reduce, leading to mixtures of carbanion and radical. To comprehensively determine purity of radicals, we advocate the combination of UV–vis, 1H NMR, and EPR spectroscopy, together with the addition of reagents that selectively trap the carbocation (e.g., isopropanol) or the carbanion. The EPR spectra of all of the radicals in this paper have been reported previously,27,45−47 and our spectra match the prior ones. The optical spectra and the extinction coefficients documented here are our recommended place to start.

Synthesis of Radicals

We began our studies by attempting to modify existing literature procedures for the synthesis of [tBu]•. Generally, these procedures involve reacting [tBu]Br with an excess of metal (e.g. Zn, Cu, or Ag) in toluene (Scheme 2, red path). Immediately, we found that these preparations in our hands led to product mixtures with large amounts of a highly colored impurity (λmax = 464 nm) (Figure S2). This yellow impurity was again observed when the colorless [tBu]Br was dissolved in toluene in the absence of any reductant. Additionally, this species was visible in the 1H NMR spectrum of [tBu]Br in C6D6 and, to a greater extent, in d3-MeCN, prompting us to assign this species as the carbocation [tBu]+. Directed synthesis and characterization of [tBu]+ corroborated this assignment as discussed below. Heterogeneous reductants are capable of reducing [tBu]+, albeit slowly: the peak at 464 nm typically persisted for several days in toluene (see SI Section 3 and Figures S3 and S4).

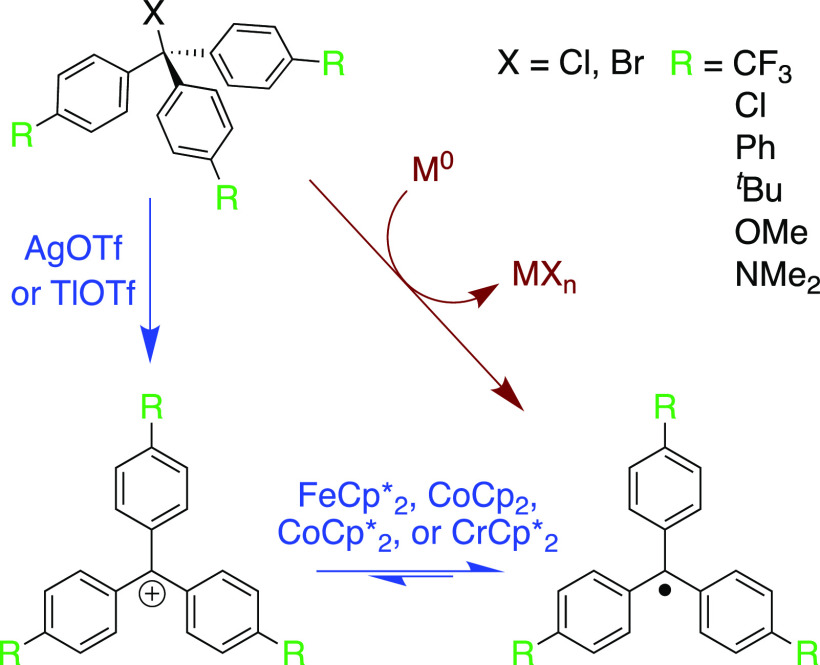

Scheme 2. Routes to Trityl Radicals: Conventional Synthesis with Heterogeneous Reductants (Red) vs the Recommended Two-Step Synthesis (Blue).

Optimization afforded reproducible access to [tBu]• using heterogeneous reductants. In the glovebox, [tBu]Br was dissolved in Et2O and treated with 40 equiv of Zn (100 mesh; opened, used, and stored in a glovebox; not acid-washed). The reaction mixture was wrapped in aluminum foil to exclude light and was stirred aggressively for two hours, at which point no carbocation was observed by UV–visible spectroscopy. While still in the glovebox, the resulting reaction mixture was vacuum-filtered over an oven-dried glass frit to isolate an orange microcrystalline powder and Zn. The flask under the fritted funnel was swapped, and the filter cake was washed with toluene to afford the crude radical. This crude orange powder was free from 1H NMR-active diamagnetic impurities. In an effort to access crystalline materials, this powder can be recrystallized by cooling a saturated Et2O solution to −35 °C overnight in the glovebox freezer to provide [tBu]• in 22% yield. The benefits of this method are two-fold: the lower ionizing power of Et2O minimizes unproductive carbocation formation, and the radical’s poor solubility allows precipitation of the product away from any impurities in solution. Multiple preparations of [tBu]• using this method gave optical spectra and εM values that were reproducible across batches.

Unfortunately, the same conditions cannot be applied to other para-substituted trityl radicals that have varying solubility and carbocation stability. Multiple synthetic methods have been reported for the formation of other trityls, but we could not reproduce them and obtain products in good purity. The large variability in reactivity and the sensitivity to a variety of factors (i.e., heterogeneous metal reductant identity and size, solvent, temperature, concentration) led us to re-evaluate our synthetic route toward this family of trityl radicals.

The strategy that we developed leverages the stability of trityl carbocations as isolable intermediates. Since the triphenylmethyl cations are so stable, evident by their spontaneous formation from the halide precursors, we sought to controllably synthesize and reduce them. Previously reported electrochemical measurements found that some carbocations exhibit reversible one-electron reduction waves.48−50 Therefore, outer-sphere electron transfer by a homogeneous reagent with the appropriate reduction potential should enable stoichiometric formation of the radical from the carbocation. We decided to target a set of trityl substrates, ranging from electron-rich (R = Me2N, MeO, tBu, and Ph) to electron-deficient (R = Cl and CF3). These were chosen due to their frequent use in the literature and the range of electron richness (Hammett 3σp = −2.49 to +2.28), allowing users a choice of electronic polarity when utilizing trityl radicals.

Those familiar with the existing trityl literature may note that we are omitting [NO2]•, a derivative that was popular in the early days of trityl chemistry (1920–1940s). Crystalline samples of this radical have always been difficult to access; the crystal structure was solved using material generated by dipping a zinc rod in a solution of [NO2]Br51 over days. This is not a suitable procedure to generate appreciable quantities. An improved synthetic procedure for this derivative has been reported,36 but its extremely low solubility in all common solvents makes it challenging to work with. While [NO2]• is not a focus here, some of its reported physical and optical parameters are included in the summary in Table 1 below for comparison.

Table 1. Crystallographic, Optical, and Electrochemical Data for the Trityl Radicals Reported Here.

| R = | Θaveragea | Σanglesb | λmax (nm)c | ε (M–1 cm–1)c | E(+/•)d | E(•/−)d | ΔEe | 3σp67 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me2N | 403f | 58,000f | –1.17 | [−2.14] | 1.07 | –2.49 | ||

| MeO | 36.3° | 360.0(5)° | 536 | 560 | –0.58 | [−1.84] | 1.30 | –0.81 |

| tBu | 31.0° | 360.0(5)° | 525 | 815 | [−0.40] | [−1.77] | 1.37 | –0.48 |

| Ph | 30.8° | 359.9(7)° | 565 | 1000 | [−0.30] | [−1.44] | 1.14 | –0.03 |

| Cl | 27.0° | 360.0(2)° | 536 | 380 | 0.00 | [−1.27] | 1.27 | 0.69 |

| CF3 | 32.7° | 360.0(3)° | 522 | 1240 | 0.29 | –1.10 | 1.39 | 1.62 |

| NO2 | 32.0°44 | 360(1)° | 61932 g | n/a | 2.28 |

Dihedral angle defined as the angle between the plane of a phenyl group and the plane of the central 4 carbons.

Sum of angles around central methyl carbon.

Reported at room temperature in toluene unless otherwise noted. Molar extinction coefficients are reported with an uncertainty of ±3%.

Potentials in MeCN are reported as V vs Fc/Fc+. Potentials are E1/2 = (Ep,a + Ep,c)/2 except those in square brackets that are irreversible potentials, reported as the potential at the cathodic peak current, Ep,c.

ΔE = E(+/•) – E(•/−).

Reported at room temperature in MeCN.

Reported in MeCN as a saturated solution, without a concentration listed.

The synthetic approach that worked best is a two-step path through the carbocation (Scheme 2, blue path). The starting materials are the commercial trityl chlorides [MeO]Cl or [Me2N]+Cl– (better known as crystal violet) or the easily accessible trityl bromides [tBu]Br, [Ph]Br, [Cl]Br, and [CF3]Br. Abstraction of the trityl halide using silver trifluoromethanesulfonate (silver triflate, AgOTf) in dichloromethane (DCM) affords the carbocation. Following filtration of the AgX product (X = Cl and Br), reduction of the carbocation with a one-electron reductant provides the radicals. The appropriate reductant was chosen based on the carbocation reduction potential, FeCp*2 for e––poor, easily reduced cations, and the stronger CoCp2 or CrCp*2 for e––rich [R]+ (see Table S2 for reduction potentials of metallocenes used here). The radicals [Cl]•, [Ph]•, and [tBu]• have poor solubility in MeCN, so reductions done in this solvent yielded the radicals as clean, isolable precipitates, while any remaining reactants or side products remained soluble. Although [MeO]• did not precipitate from MeCN quickly at room temperature, a clean product was obtained by extraction into nonpolar solvents followed by recrystallization.

Synthesis of [CF3]• required simultaneous use of thallium(I) triflate and FeCp*2 in a one-pot synthesis, as opposed to the stepwise approach [caution: thallium salts are very toxic]. In our hands, [CF3]+ decomposed over the course of hours even in the solid state. Given the instability of [CF3]+, the faster and cleaner halide abstraction by TlOTf versus Ag(I) salts was employed. This enabled one-pot synthesis since Tl(I) is not reduced by the FeCp*2. In the presence of the reductant, [CF3]+ immediately converts to [CF3]•, minimizing decomposition and side product formation. The radical can also be accessed by deprotonation followed by oxidation of the carbanion, similar to the synthesis of polychlorinated trityl radicals.52 [CF3]− was generated by stoichiometric addition of nBu4N+OH– (TBAOH) to [CF3]H in THF, and subsequent oxidation with p-chloranil produced the radical cleanly by optical spectroscopy (SI Section 5). However, reactions on a larger scale formed a much less pure product. [CF3]• was purified by cooling a concentrated pentane solution to −35 °C to yield large green needles.

[Me2N]• proved to be the most difficult radical in the series to synthesize cleanly. One complicating factor is the strong ion-pairing of [Me2N]+ in lower-polarity solvents. Oliveira et al. estimated that in solvents with low dielectric constants (ε < 10), the ion-pair association constant of [Me2N]+ with Cl– is between 105 and 108 M–1.53 This was evident when AgOTf would not remove Cl– from a solution of crystal violet in DCM under similar conditions to the other trityl halides (although the iodide salt54 reacts with AgOTf). The ion-pairing stabilization of [Me2N]+X– can also make it more difficult to reduce the cation.55 We therefore recommend using [Me2N]BPh456 as the starting material and the strong reductant CrCp*2 (Keq values for reduction by CrCp*2 and CoCp2 are ∼8 × 104 and 340 based on the 1e– reduction potentials57). CoCp*2 was too reducing, giving [Me2N]H as the major product by 1H NMR. [Me2N]• generated in this fashion was extracted into toluene, away from side products and the starting material.

[Me2N]• is also difficult to isolate cleanly because it spontaneously decomposes, even in the dark. By 1H NMR, the primary decomposition product was [Me2N]H, with many small low-intensity aromatic resonances; crystal violet was not formed. This instability has been previously reported, and [Me2N]H was detected by spectrofluorimetric voltammetry.32,58 In our hands, crystallized [Me2N]• always contained some [Me2N]H, preventing growing a good-quality single crystal for structural studies. Monitoring the decay of [Me2N]• by optical spectroscopy indicated slow bimolecular kinetics (a 3 mM solution of the radical decayed over 2 weeks, Figure S24). To minimize decomposition, we recommend synthesis of this radical at lower concentrations (see the SI for conditions).

The trityl radicals are all stable in the solid state for months at room temperature under an inert atmosphere, including in the presence of light. This enables their utility like any other air-sensitive benchtop reagent, i.e., it is not necessary to make a fresh radical solid for every experiment. The solution stability of the radicals depends on the para-substituent, as judged by changes in optical spectra over time (SI Section 6). The para-phenyl species, [Ph]•, was found to be the most stable, being unchanged for more than a day in toluene even in ambient lab light. Solutions of [tBu]•, [CF3]•, and [MeO]• were stable in the dark, showing no decay overnight in a cuvette wrapped in aluminum foil in a glovebox. [tBu]• was found to be stable both in toluene and in MeCN. In room light, [tBu]• in toluene decayed in a first-order fashion with t1/2 ≅ 3 h; in MeCN, half was lost in ∼1/2 h in a multiexponential decrease. The chloro-substituted radical is the least stable of all of these radicals, decomposing completely over a couple of days in toluene, even in the absence of light.

Photodecomposition of trityl radicals has been previously described, and cyclization between two aryl groups leading to a 9-phenylfluorenyl radical and 2H• equivalents was proposed.59−61 Such photocyclizations are common in organic chemistry such as those observed with stilbenes in the presence of UV light.62 From this, the relative photocyclization resistance observed for [Ph]• likely stems from the extra delocalization in the excited state.63

The differing para functional groups bestow varying solubilities for the radical series. All of the radicals are soluble in toluene and benzene obtaining concentrations >10 mM except for [Ph]•, which saturates at a concentration of ∼2 mM. The solubilities in THF appear to be similar but are lower in diethyl ether. The radicals are insoluble in hexamethyldisiloxane, except [Me2N]• to a small extent, allowing its use as a good cocrystallizing solvent. In hexane and pentane, the radicals dissolve to a small extent to give some colorization to the solution, except for [Ph]•, which was insoluble. [CF3]• has the highest solubility in pentane (∼20 mM). As mentioned earlier, [Cl]•, [Ph]•, and [tBu]• are insoluble in MeCN, while those with the more polar substituents [CF3]•, [MeO]•, and [Me2N]• radicals are soluble in MeCN with concentrations >10 mM. Prior reports have used acetone, chloroform, pyridine, or alcohol/hydrocarbon mixtures as solvents for spectroscopic studies.36,47,64

X-ray Crystallography of Radicals

Single crystals of the trityl radicals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained upon recrystallization (see the SI for individual conditions). The molecular structures of the series (4-RPh)3C• (R = CF3, Cl, Ph, tBu, and MeO; Figure 1) are similar to the structure of [NO2]•, the only previously reported crystal structure of a para-substituted trityl radical. All six structures have a trigonal planar, sp2-hybridized central carbon atom, based on the sums of the central C–C–C bond angles being 360° (Table 1).

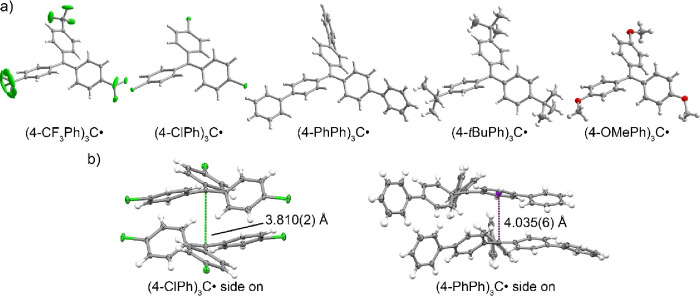

Figure 1.

(a) Molecular structures of the trityl radicals determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction; thermal ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability (one of the CF3 groups is disordered). Cl and F, green; O, red; C, gray; H, white. (b) Side-on view of radical stacking in [Cl]• (left) and [Ph]• (right) structures showing possible intermolecular interactions. The purple ball in the structure for [Ph]• represents the ring centroid.

All of the radical structures have propeller-like orientations of the three phenyl rings. For all but the R = Ph compound, there are only slight distortions from a perfect 3-fold symmetry in the crystals (at 100 K). Dihedral angles (Θ, defined as the angle between the plane of a phenyl group and the plane of the central 4 carbons) range from 25 to 35° for R = Cl, tBu, and MeO. The similar angles suggest similar degrees of radical delocalization, though the solid-state structures are likely affected by crystal packing. This is consistent with EPR studies of 11 trityl radicals in which the 1H hyperfine coupling values at room temperature in solution suggested similar delocalizations.28,36

Inspection of the crystal packing in structures of [Cl]• and [Ph]• shows the potential for intermolecular interactions. The distance between sp2 radical centers of neighboring molecules in the structure of [Cl]• is 3.810(2) Å (Figure 1b). As a consequence, the phenyl rings are less twisted relative to the other radical molecules (Θaverage = 26.95° for [Cl]•), making them more planar overall. This C···C distance is too long for a chemical bond but could indicate a possible weak interaction or could just be due to crystal packing. The crystal structure for [Ph]• reveals that one of the phenyl groups adjacent to the radical aligns with the radical center of an adjacent molecule (Figure 1b, the phenyl centroid···central C distance is 4.035(6) Å). This decreases the torsion angle for that phenyl group, likely leading to more extensive radical delocalization. Intermolecular coupling has been reported for [Ph]• based on EPR spectra of a concentrated frozen toluene glass of [Ph]•, which implicated a triplet ground state with an eclipsed conformation of two radicals 4.3−4.7 Å apart.65

The room-temperature EPR spectra of toluene solutions of [CF3]•, [tBu]•, and [MeO]• are sharp and show only one set of isotropic 1H hyperfine values for the inner most phenyl rings, indicating isolated radicals.27,46 However, broadened spectra were reported for [Cl]• in toluene.66 Our room-temperature EPR spectra also show larger line widths for [Ph]• and [Cl]• as compared to [CF3]•, [tBu]•, and [MeO]• in similar ∼0.25 mM toluene solutions (see SI Section 8). The broadening could be due to intermolecular interactions, or perhaps to instrument parameters, dipolar coupling, quadrupolar moment of 35/37Cl, or to the viscosity of toluene (as suggested in ref (47)).

UV–Vis Spectroscopy of Radicals, Carbocations, and Carbanions

UV–visible spectra were obtained for all of the radicals in toluene, using our purified materials (recrystallized and clean by 1H NMR). In all cases, the absorbances increase linearly with concentrations up to 1 mM (SI Figures S5–S9). This shows that there is no significant dimerization of these radicals under these conditions.

The spectra of [CF3]•, [Cl]•, [tBu]•, and [MeO]• feature three closely spaced well-resolved bands in the visible region, with additional smaller features, while [Ph]• features a single broad band (Figure 2a and Table 1). The lowest-energy visible band is relatively sharp for X = CF3, Cl, tBu, and MeO, and the energy of this transition is relatively unaffected by the para-substituent. [Me2N]• exhibits one intense band at λ = 406 nm with low-intensity shoulders around 600 nm (off scale in Figure 2a, see Figure S23 top). The fine structure of trityl radical optical absorption spectra is better resolved, and fluorescence is observed, at “liquid air” temperatures, as reported by G. N. Lewis et al. in 1944.64

Figure 2.

UV–visible spectra of [(4-RPh)3C]+/•/– measured at room temperature. (a) Absorbance spectra of radicals plotted as molar extinction coefficient (εM) in M–1 cm–1. Each radical spectrum is reported in toluene, except [Me2N]•, which is reported in MeCN. (b) Absorbance spectra of the carbocations in DCM, plotted as εM, generated from the reaction of the triarylmethyl halide with AgOTf except for crystal violet. (c) Absorbance spectra of the carbanions in THF, plotted as εM, generated from reduction of the triarylmethyl halide with KC8 or from deprotonation with TBAOH. Estimated εM values for the carbocations and carbanions are presented in Table S1.

The optical spectra of the para-substituted radicals serve as good indicators for the purity of the material. The primary common impurities are the carbocation and carbanion, and both have higher peak molar extinction coefficients (εM), ≥ ∼104 M–1 cm–1, than the radicals, 400–1000 cm–1 M–1 (Table 1 and Table S1). Thus, even small amounts of these impurities are spectroscopically apparent.

A simple chemical test for the presence of carbocation is the addition of isopropyl alcohol (IPA). The solutions all rapidly turn colorless for all the carbocations except [Me2N]+. 1H NMR spectra showed the formation of the corresponding trityl-isopropyl ether. Due to the high stability of [Me2N]+ (crystal violet), a stronger base such as tetra-n-butylammonium hydroxide was required to quench the solution color, forming the carbinol. This qualitatively follows the trend in pKR+ values reported previously: KR+ is the equilibrium constant for Ar3C+ + H2O → Ar3COH + H+ in aqueous acid.68 Degassed IPA does not react with any of the radicals, as no change is observed in the optical spectra upon addition of IPA beyond what is needed to quench the carbocation.

Similar to the carbocations, the carbanions have strong, broad, optical absorbances typically in the 400–600 nm range (Figure 2c). Their molar extinction coefficients, εM, are estimated to be ∼104 cm–1 M–1. These are 5–10 times lower for [R]− than for [R]+ but roughly 10 times larger than those for the radicals (Figure 2 and Table S1). The carbanions were generated in situ by reduction of the bromide or chloride precursors [R]X with KC8 in dry THF and characterized by UV–vis spectroscopy. All carbanions are indefinitely stable in dry, air-free THF, with the exception of [Cl]K, which decomposes over the course of hours to a colorless solution.

The presence of a carbanion can be chemically tested by addition of a simple alcohol such as methanol, which rapidly quenches the color of the solutions. For [tBu]−K+ in THF, from [tBu]• + KC8, the addition of excess 18-crown-6 redshifted the λmax by ∼20 nm. The 18-crown-6 presumably binds the K+ and reduces its interaction with the carbanion. This could be due to a direct C––K+ or π–K+ interaction, or to a tight ion pair. Similar interactions are likely to occur for the other carbanions except for [CF3]−[nBu4N]+.

Cyclic Voltammetry of the Carbocations and Radicals

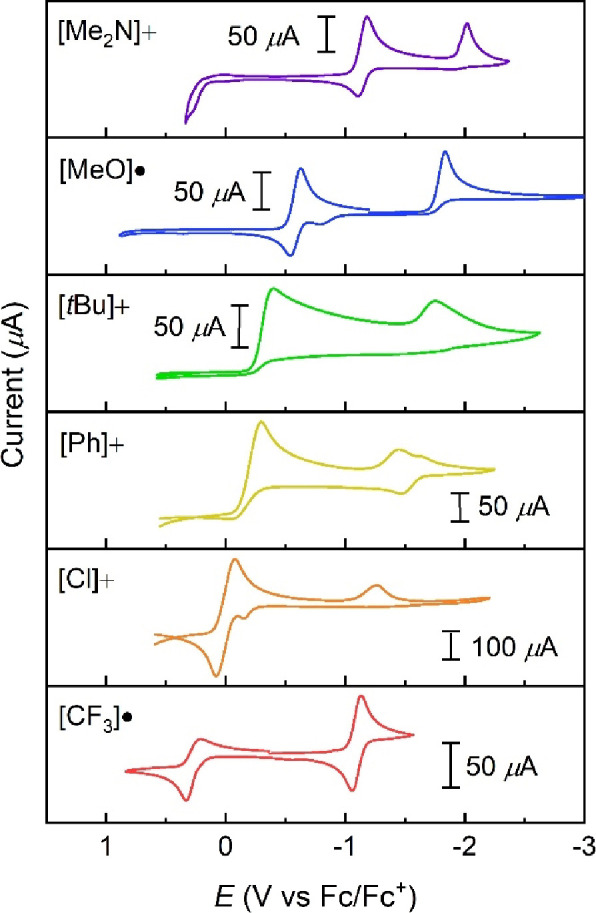

The span of electron-withdrawing/electron-donating substituents in the trityl radicals studied here, 3σp = −2.49 to +1.62, prompted us to investigate their electrochemical properties using cyclic voltammetry (CV). A previous study has reported reduction potentials of some of the carbocations in MeCN using polarography, though to our knowledge, the reduction potentials to the carbanions have not been investigated.69 CVs of degassed MeCN solutions of carbocations or radicals are shown in Figure 3. The carbocations for R = tBu, Ph, and Cl were used because the radicals are insoluble in MeCN.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammograms of carbocations or radicals (5–15 mM) in MeCN at room temperature, 0.1 M [Bu4N][PF6], internally referenced after the scan with Fc/Fc+, and with iR compensation; scan rates, 100 mV/s.

All of the voltammograms display two redox features, which we attribute to the cation/radical [R]+/[R]• and radical/anion couples [R]•/[R]−. Starting from the resting potential for the cations, these are two reductive waves; from the radicals, these are one reduction and one oxidation event.

In this initial survey, few of the CV waves appear chemically reversible. This was at first surprising given the chemical stability of the species involved, but the syntheses described above were under different conditions. The reductions of [tBu]+ and [Ph]+ to their respective radicals are irreversible, likely due to low solubility of the radical species. Blocking of the electrode by precipitation could also explain the smaller wave for reduction to the carbanion. Both of the [R]+/[R]• events for R = Me2N and MeO are reversible, which is more apparent when scanning only over that feature as shown in Figure S25. The irreversibility of most of the reductions to the carbanions likely is a result of rapid protonation by residual water in the electrolyte. Our MeCN contains <5 ppm H2O (the detection limit) from Karl Fischer titration. In our experience, it is not possible to dry MeCN further (or to purchase drier MeCN), while the THF used in the preparative experiments was dried in a solvent system and dispensed directly into a glovebox. For [CF3]•, oxidation is quasireversible reflecting the instability of the carbocation formed, while reduction to the carbanion is the only apparently reversible [R]•/[R]− wave in the series. [CF3]− is the most stable carbanion and presumably the least basic.

The [R]+/[R]• and [R]•/[R]− potentials each span a range of >1 V across the series. [Me2N]• is very easy to oxidize, while [CF3]• is not very difficult to reduce (Table 1). Yet, the differences between E(+/•) and E(•/−) for each [X]+/•/– are much more constant: ΔE = 1.25 ± 0.18 V.

The E(+/•) and E(•/−) potentials each correlate well with the Hammett parameters σp (Table 2) and almost as well with σp+ and σp– (SI Section 7). The E/3σp slopes are 0.35 V/3σp and 0.29 V/3σp (r2 = 0.99, 0.93), respectively. The poorer correlation for E(•/−) is likely due to the mixing of E1/2 and Ep potentials. After converting E to ln(Keq) [Δln(Keq) = FΔE/RT], the slopes correspond to Hammett ρ per 3σp of 6.0 for E(+/•) and 4.9 for E(•/−). These ρ values extend the detailed prior transient studies of the benzyl and diphenylmethyl radical potentials.70 While all of the ρ values are large, the effect per substituent decreases with an increasing number of aryl rings, in part because of the distortion from planarity in the polyaryl compounds. The topic of substituent effects on the properties of free radicals has of course received much attention.71

Table 2. Hammett Parameters for Reduction Potentials of Arylmethanesa.

| ρ | ρ+ | ρ– | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ar3C+/• | per 3σ | 6.0 | 3.5 | ||

| Ar3C•/– | per 3σ | 4.9 | 4.8 | ||

| ArPhCH+/• | per 1σ | 5.6 | |||

| ArPhCH•/– | per 1σ | 7.4 | |||

| ArCH2+/• | per 1σ | 9.3 | |||

| ArCH2•/– | per 1σ | 13.5 | |||

The first two lines are from this work (Table 1 and SI Section 7); the remaining values are from ref (70).

Conclusions and Outlook

Trityl radicals, Ar3C•, have served as model and useful carbon-centered radicals in studies in many areas of chemistry for over 120 years. A variety of synthetic methods have been reported, many to generate solutions of the radicals that are typically used without detailed characterization. The studies reported here show that the prior procedures do not reproducibly give pure radicals. We identify the common impurities, especially the related carbocation Ar3C+ and the carbanion Ar3C–, provide their spectroscopic signatures, and indicate why they are formed.

This report describes a new two-step synthetic route and detailed procedures for the preparation of six para-substituted trityl radicals in high purity. Trityl halides Ar3CX are first converted to Ar3C+, which is then reduced to the radical Ar3C• with appropriate outer-sphere metallocene reductants such as FeCp*2, CoCp2, or CrCp*2. By this simple method, solids of high purity have been isolated and fully characterized by optical, NMR, and EPR spectroscopies. Five of the six have been characterized by single-crystal X-ray crystallography. Since the isolated radicals are absent of impurities by 1H NMR and optical spectroscopies, accurate determinations of molar absorptivities, εM, are reported. The εM should be valuable for quantitative studies using these radicals.

While some applications of trityl radicals may not require such high-purity materials, we believe that in most cases, it will be valuable to work with isolated, storable crystalline materials. We encourage future practitioners to use the syntheses described here, which are not onerous. The general synthetic approach will also likely prove applicable to more highly decorated trityl radicals. We especially encourage use of the spectral data and reactivity reported here to check for common impurities in trityl radicals, such as the carbocation or the trityl methane.

The trityl radicals studied here exhibit a wide range of reduction potentials, from very electron-rich (X = Me2N) to electron-deficient (X = CF3). This will allow researchers to choose a trityl radical that best fits the electronic needs of their application. We hope that this guide and the ready availability of pure materials enable further use of trityl radicals in understanding molecular and biochemical reactivity, in molecular electronics, in organic semiconductors, and many new areas.

Acknowledgments

A.M.H. gratefully acknowledges support from a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. S.C.C. (F32GM1329266-02) gratefully acknowledges support from a U.S. National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein Postdoctoral Fellowship. We acknowledge the U.S. National Institutes of Health (2R01GM50422 and 1R35GM144105 to J.M.M.) for funding this work.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.3c00658.

Experimental procedures for the synthesis and characterization of radicals (PDF)

Author Contributions

† A.M.H. and S.C.C. contributed equally to this work.

Author Contributions

A.M.H., S.C.C., and G.S. conducted experiments. B.Q.M. was responsible for the crystallographic work. The manuscript was written by A.M.H., S.C.C., and J.M.M. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Roberts J. D.; Caserio M. C.. Basic principles of organic chemistry; 2nd ed.; W. A., Benjamin: Menlo Park: Calif., 1977; pp. 350–409. [Google Scholar]

- Darcy J. W.; Koronkiewicz B.; Parada G. A.; Mayer J. M. A Continuum of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reactivity. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2391–2399. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darcy J. W.; Kolmar S. S.; Mayer J. M. Transition State Asymmetry in C-H Bond Cleavage by Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10777–10787. 10.1021/jacs.9b04303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitre S. P.; Weires N. A.; Overman L. E. Forging C(sp3)-C(sp3) Bonds with Carbon-Centered Radicals in the Synthesis of Complex Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2800–2813. 10.1021/jacs.8b11790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonjoch J.; Diaba F. Radical Reactions in Alkaloid Synthesis: A Perspective from Carbon Radical Precursors. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 5070–5100. 10.1002/ejoc.202000391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero K. J.; Galliher M. S.; Pratt D. A.; Stephenson C. R. J. Radicals in Natural Product Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7851–7866. 10.1039/C8CS00379C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y. L.; Liu G. X.; Liu J. W.; Tram L.; Qiu H.; Doyle M. P. Radical-Mediated Strategies for the Functionalization of Alkenes with Diazo Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 13846–13855. 10.1021/jacs.0c05183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S.; Cheung K. P. S.; Gevorgyan V. C-H Functionalization Reactions Enabled by Hydrogen Atom Transfer to Carbon-Centered Radicals. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12974–12993. 10.1039/D0SC04881J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibler I. N.-M.; Tekle-Smith M. A.; Doyle A. G. A General Strategy for C(sp3)-H Functionalization with Nucleophiles Using Methyl Radical as a Hydrogen Atom Abstractor. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6950. 10.1038/s41467-021-27165-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendler S.; Macmillan D. W. C. Enantioselective Polyene Cyclization via Organo-SOMO Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 5027–5029. 10.1021/ja100185p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le C.; Liang Y.; Evans R. W.; Li X.; MacMillan D. W. C. Selective sp3 C-H Alkylation via Polarity-Match-Based Cross-Coupling. Nature 2017, 547, 79–83. 10.1038/nature22813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsaee F.; Senarathna M. C.; Kannangara P. B.; Alexander S. N.; Arche P. D. E.; Welin E. R. Radical philicity and its role in selective organic transformations. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 486–499. 10.1038/s41570-021-00284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittra K.; Green M. T. Reduction Potentials of P450 Compounds I and II: Insight into the Thermodynamics of C-H Bond Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5504–5510. 10.1021/jacs.9b00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittle J.; Green M. T. Cytochrome P450 Compound I: Capture, Characterization, and C-H Bond Activation Kinetics. Science 2010, 330, 933–937. 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantignana V.; Serrano-Plana J.; Draksharapu A.; Magallón C.; Banerjee S.; Fan R.; Gamba I.; Guo Y.; Que L. Jr.; Costas M.; Spectroscopic and Reactivity Comparisons between Nonheme Oxoiron(IV) and Oxoiron(V) Species Bearing the Same Ancillary Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 15078–15091. 10.1021/jacs.9b05758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav V.; Rodriguez R. J.; Siegler M. A.; Goldberg D. P. Determining the Inherent Selectivity for Carbon Radical Hydroxylation versus Halogenation with Fe(III)(OH)(X) Complexes: Relevance to the Rebound Step in Non-heme Iron Halogenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 7259–7264. 10.1021/jacs.0c00493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangia T. M.; Davies C. G.; Prendergast J. R.; Gordon J. B.; Siegler M. A.; Jameson G. N. L.; Goldberg D. P. Observation of Radical Rebound in a Mononuclear Nonheme Iron Model Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4191–4194. 10.1021/jacs.7b12707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard E. F.; Yadav V.; Goldberg D. P.; de Visser S. P. What Drives Radical Halogenation versus Hydroxylation in Mononuclear Nonheme Iron Complexes? A Combined Experimental and Computational Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 10752–10767. 10.1021/jacs.2c01375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. C.; Suess D. L. M. Reversible Formation of Alkyl Radicals at [Fe4S4] Clusters and Its Implications for Selectivity in Radical SAM Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 14240–14248. 10.1021/jacs.0c05590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vey J. L.; Drennan C. L. Structural Insights into Radical Generation by the Radical SAM Superfamily. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 2487–2506. 10.1021/cr9002616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick J. B.; Duffus B. R.; Duschene K. S.; Shepard E. M. Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4229–4317. 10.1021/cr4004709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. L. Chemistry and Enzymology of Vitamin B12. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2075–2150. 10.1021/cr030720z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber K.; Puffer B.; Kräutler B. Vitamin B12-derivatives—enzyme cofactors and ligands of proteins and nucleic acids. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4346–4363. 10.1039/c1cs15118e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks R. G.Stable Radicals: Fundamentals and Applied Aspects of Odd-Electron Compounds; Wiley: Hoboken, N.J., 2010, 10.1002/9780470666975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomberg M. An Instance of Trivalent Carbon: Triphenylmethyl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1900, 22, 757–771. 10.1021/ja02049a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lankamp H.; Nauta W. T.; MacLean C. A new interpretation of the monomer-dimer equilibrium of triphenylmethyl- and alkylsubstituted-diphenyl methyl-radicals in solution. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968, 9, 249–254. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)75598-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair J.; Kivelson D. Electron Spin Resonance Studies of Substituted Triphenylmethyl Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 5074–5080. 10.1021/ja01021a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dünnebacke D.; Neumann W. P.; Penenory A.; Stewen U. Über Sterisch Gehinderte Greie Radikale, XIX. Stabile 4,4′,4″-Trisubstituierte Triphenylmethyl-Radikale. Chem. Ber. 1989, 122, 533–535. 10.1002/cber.19891220322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rösel S.; Schreiner P. R. Computational Chemistry as a Conceptual Game Changer: Understanding the Role of London Dispersion in Hexaphenylethane Derivatives (Gomberg Systems). Isr. J. Chem. 2022, 62, e202200002 10.1002/ijch.202200002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colle T. H.; Lewis E. S. Hydrogen Atom Transfers From Thiophenols to Triarylmethyl Radicals. Rates, Substituent Effects, and Tunnel Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 1810–1814. 10.1021/ja00501a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D. C.; Lawrie C. J. C.; Moody A. E.; Norton J. R. Relative Rates of Hydrogen Atom (H•) Transfer from Transition-Metal Hydrides to Trityl Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 4888–4895. 10.1021/ja00013a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaragoza J. P. T.; Yosca T. H.; Siegler M. A.; Moënne-Loccoz P.; Green M. T.; Goldberg D. P. Direct Observation of Oxygen Rebound with an Iron-Hydroxide Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13640–13643. 10.1021/jacs.7b07979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez A.; Selga A.; Torres J. L.; Julié L. Reducing Activity of Polyphenols with Stable Radicals of the TTM Series. Electron Transfer versus H-Abstraction Reactions in Flavan-3-ols. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4583–4586. 10.1021/ol048015f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Han A.; Pulling M. E.; Estes D. P.; Norton J. R. Evidence for Formation of a Co-H Bond from (H2O)2Co(dmgBF2)2 under H2: Application to Radical Cyclizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 14662–14665. 10.1021/ja306037w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekara T.; Abramo G. P.; Hansen A.; Neugebauer H.; Bursch M.; Grimme S.; Norton J. R. TEMPO-Mediated Catalysis of the Sterically Hindered Hydrogen Atom Transfer Reaction between (C5Ph5)Cr(CO)3H and a Trityl Radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 1882–1886. 10.1021/jacs.8b12892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter W. W.; Vaid T. P. Doping of an Organic Molecular Semiconductor by Substitutional Cocrystallization with a Molecular n-Dopant. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 469–475. 10.1039/B610806G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L.; Shi J.; Wei J.; Yu T.; Huang W. Air-Stable Organic Radicals: New-Generation Materials for Flexible Electronics?. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1908015 10.1002/adma.201908015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedenbänder T.; Aladin V.; Saeidpour S.; Corzilius B. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization for Sensitivity Enhancement in Biomolecular Solid-State NMR. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 9738–9794. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibbert H. B.; Neugebauer H.; Norton J. R.; Hansen A.; Bursch M.; Grimme S. Hydrogen atom transfer rates from Tp-containing metal-hydrides to trityl radicals. Can. J. Chem. 2020, 99, 216–220. 10.1139/cjc-2020-0392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y. X.; Theyssen N.; Eifert T.; Liauw M. A.; Franciò G.; Schenk K.; Leitner W.; Reetz M. T. Concerning the Role of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide in SN1 Reactions. Chemistry 2017, 23, 3898–3902. 10.1002/chem.201604151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtin N. N.; Leftin H. P. Ionization and Dissociation Equilibria in Sulfur Dioxide. IV. Alkyl and Aryl Derivatives of Triphenylchloromethane at 0 and −8.9°. J. Phys. Chem. 1956, 60, 164–169. 10.1021/j150536a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yukawa Y.; Tsuno Y. Resonance Effect in Hammett Relationship. III. The Modified Hammett Relationship for Electrophilic Reactions. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1959, 32, 971–981. 10.1246/bcsj.32.971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Price E.; Lichtin N. N. Ionization and dissociation equilibria of some triphenylchloromethane derivatives in nitrobenzene at 25°. Tetrahedron Lett. 1960, 1, 10–16. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)84079-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman H. H.Carbonium Ions; John Wiley & Sons: Nashville, TN, 1973; Vol. 4, pp. 1501–1574. [Google Scholar]

- Maki A. H.; Allendoerfer R. D.; Danner J. C.; Keys R. T. Electron nuclear double resonance in solutions. Spin densities in triarylmethyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 4225–4231. 10.1021/ja01018a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hart W. J. The E.S.R. spectra of triarylmethyl radicals. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 75–84. 10.1080/00268977000101021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hart W. J. ESR spectra of some chlorine-substituted triphenylmethyl radicals. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1967, 1, 233–234. 10.1016/0009-2614(67)85060-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R.; Chu W. Thermodynamic determination of pKa’s of weak hydrocarbon acids using electrochemical reduction data. Triarylmethyl anions, cycloheptatrienyl anion, and triphenyl- and trialkylcyclopropenyl anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 411–418. 10.1021/ja00783a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J.; Handoo K. L.; Parker V. D. Hydride affinities of carbenium ions in acetonitrile and dimethyl sulfoxide solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 2655–2660. 10.1021/ja00060a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett E. M.; Flowers R. A.; Ludwig R. T.; Meekhof A. E.; Walek S. A. Triarylmethanes and 9-arylxanthenes as prototypes amphihydric compounds for relating the stabilities of cations, anions and radicals by C-H bond cleavage and electron transfer. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 1997, 10, 499–513. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen P.; Klewe B.; Östlund E.; Bloom G.; Hagen G. The Crystal Structure of the Free Radical Tri-p-nitrophenylmethyl. Acta Chem. Scand. 1967, 21, 2599–2607. 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.21-2599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armet O.; Veciana J.; Rovira C.; Riera J.; Castaner J.; Molins E.; Rius J.; Miravitlles C.; Olivella S.; Brichfeus J. Inert carbon free radicals. 8. Polychlorotriphenylmethyl radicals: synthesis, structure, and spin-density distribution. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 5608–5616. 10.1021/j100306a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira C. S.; Branco K. P.; Baptista M. S.; Indig G. L. Solvent and concentration effects on the visible spectra of tri-para-dialkylamino-substituted triarylmethane dyes in liquid solutions. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2002, 58, 2971–2982. 10.1016/S1386-1425(02)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulev Y. A.; Gugkaeva Z. T.; Lokutova A. V.; Maleev V. I.; Peregudov A. S.; Wu X.; North M.; Belokon Y. N. Carbocation/Polyol Systems as Efficient Organic Catalysts for the Preparation of Cyclic Carbonates. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1152–1159. 10.1002/cssc.201601246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For instance, reduction of [Me2N]+ to MeCN forms [Me2N]•, but that equilibrium is shifted back to the cation upon addition of less polar toluene (by optical spectroscopy).

- Spangler B. D.; Vanýsek P.; Hernandez I. C.; Rogers R. D. Structure of crystal violet tetraphenylborate. J. Crystallogr. Spectrosc. Res. 1989, 19, 589–596. 10.1007/BF01185394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J. L.; Edelstein N.; Spencer B.; Smart J. C. Syntheses and electronic structures of decamethylmetallocenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 1882–1893. 10.1021/ja00371a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Compton R. G.; Wellington R. G. Spectrofluorimetric hydrodynamic voltammetry: the investigation of electrode reaction mechanisms. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 270–273. 10.1021/j100052a045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden S. T.; Jones W. J. CXLVI.—The photodecomposition of triphenylmethyl. J. Chem. Soc. 1928, 1149–1158. 10.1039/JR9280001149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg A.; Schmidt K. H.; Meisel D. Photophysics and photochemistry of arylmethyl radicals in liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 83–91. 10.1021/ja00287a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M. A.; Gaillard E.; Chen C. C. Photochemistry of stable free radicals: the photolysis of perchlorotriphenylmethyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 7088–7094. 10.1021/ja00257a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen K. B. Photochemical oxidative cyclisation of stilbenes and stilbenoids--the Mallory-reaction. Molecules 2010, 15, 4334–4358. 10.3390/molecules15064334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory F. B.; Mallory C. W. Photocyclization of Stilbenes and Related Molecules. Org. React. 2005, 1–456. 10.1002/0471264180.or030.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G. N.; Lipkin D.; Magel T. T. The Light Absorption and Fluorescence of Triarylmethyl Free Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1944, 66, 1579–1583. 10.1021/ja01237a048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broser W.; Kurreck H.; Niemeier W. Über paramagnetische dimerenkomplexe des substituierten triphenylmethylradikals. Tetrahedron 1976, 32, 1183–1187. 10.1016/0040-4020(76)85043-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Judeikis H.; Kivelson D. The E.s.r. Spectra of Some Substituted Triarylmethyl Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 1132–1134. 10.1021/ja00866a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C.; Leo A.. Substituent constants for correlation analysis in chemistry and biology; Wiley: New York, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.-M.; Bruno J. W.; Enyinnaya E. Hydride Affinities of Arylcarbenium Ions and Iminium Ions in Dimethyl Sulfoxide and Acetonitrile. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 4671–4678. 10.1021/jo980120d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volz H.; Lotsch W. Polarographische reduktion von triarylmethylkationen. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 10, 2275–2278. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)88140-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sim B. A.; Milne P. H.; Griller D.; Wayner D. D. M. Thermodynamic significance of .rho.+ and .rho.- from substituent effects on the redox potentials of arylmethyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 6635–6638. 10.1021/ja00174a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walter R. I. Substituent Effects on the Properties of Stable Aromatic Free Radicals. The Criterion for Non-Hammett Behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 88, 1923–1930. 10.1021/ja00961a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.