Abstract

Protein-based switches that respond to different inputs to regulate cellular outputs, such as gene expression, are central to synthetic biology. For increased controllability, multi-input switches that integrate several cooperating and competing signals for the regulation of a shared output are of particular interest. The nuclear hormone receptor (NHR) superfamily offers promising starting points for engineering multi-input-controlled responses to clinically approved drugs. Starting from the VgEcR/RXR pair, we demonstrate that novel (multi)drug regulation can be achieved by exchange of the ecdysone receptor (EcR) ligand binding domain (LBD) for other human NHR-derived LBDs. For responses activated to saturation by an agonist for the first LBD, we show that outputs can be boosted by an agonist targeting the second LBD. In combination with an antagonist, output levels are tunable by up to three simultaneously present small-molecule drugs. Such high-level control validates NHRs as a versatile, engineerable platform for programming multidrug-controlled responses.

Keywords: synthetic biology, protein engineering, cell engineering, modularity, nuclear hormone receptors, multi-input switches

Introduction

Cell-based switches that regulate functional outputs in response to user-defined molecular inputs form the basis for diverse synthetic biological circuits and their biomedical applications.1,2 While protein-level circuits are increasingly being developed,3 in most cases, cellular outputs are programmed through the control of target gene expression.4 Since methods for engineering transcriptional units are well established, a diverse range of outputs can be programmed with relative ease. In contrast, there is still a limited repertoire of molecular sensors that recognize inputs, such as small molecules, and that transduce the signal to a functional response, such as gene expression. Ideally, gene outputs should be adjustable in a highly precise and bidirectional manner. Compared to single-input/single-output switches, one strategy to achieve higher-level control is through the integration of multiple molecular inputs that regulate a shared molecular output.5−13 For example, for two cooperating signals, a first input could activate target gene expression and a second input could boost the response further, such that maximal output levels are only accessible in the simultaneous presence of both signals. Conversely, it may be desirable to tune down a previously activated response with a competing input. Ideally, to minimize the number of switch components and associated sources of noise, regulation would occur at a single promoter. This regulation would avoid the complexities of systems where important regulatory components, such as those of AND or NOR logic gates, are expressed from separate inducible promoters.

For biomedical applications of switches in engineered mammalian cells, clinically approved small-molecule drugs represent ideal inputs because of their well-characterized pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic, and safety profiles as well as potential synergistic effects that could be elicited with respect to disease treatment. Several drug-controlled protein switches have been developed that are based on repurposed natural proteins and/or de novo designed proteins.7,8,14−27 However, in most of these studies, individual switches responded to a single molecular input at a time. Recently, a multi-input switch was developed based on drug-bound complexes of a “receiver” protein, namely the viral protease NS3a.7 Receiver complexes with different drugs are recognized by distinct “reader” proteins, which was exploited to program graded and switchable responses.7 While this system could enable different applications with functionalized receiver/reader combinations,7 it was based on the competition of drug inputs for a single shared binding pocket in the receiver protein. This feature limits the type of response behaviors and does not allow for the synergistic action of two cooperating inputs that regulate a shared output. Similarly, small-molecule inputs in this system are limited to drugs targeting a single viral protein, which restricts the input repertoire. Moreover, the viral origin of the target may present undesired immunogenic potential. To address such limitations, alternative multi-input systems that involve drug targets other than NS3a protease would be valuable. In addition, simultaneous modulation of human drug targets could be useful for synergistic therapeutic effects.

Nuclear hormone receptors (NHRs) are a protein superfamily that appears ideally suited for the design of drug-controlled protein switches. NHRs contain a ligand binding domain (LBD), a DNA binding domain (DBD), and a transcriptional activation domain (AD)28 (Figure 1a). They can control target gene expression in a ligand-dependent manner as homo- or heterodimers bound to DNA-based response elements.28 As a superfamily of 48 different LBDs in humans, they can sense a large variety of structurally and pharmacologically diverse ligands.28 Many of the LBDs are major drug targets for different diseases, providing a large repertoire of clinically approved drugs for potential uses as switch inputs. Notably, for applications in cell therapies, repurposing a human NHR as a drug-controlled switch component could in certain cases give rise to synergies between (1) regulating engineered cells, and (2) drugging of a disease-related target. Intriguingly, multi-input-regulated responses have been observed in certain NHR heterocomplexes, in which the agonist for a first LBD activated gene expression and the agonist for a second LBD boosted expression further, while having little effect on its own.29,30 Similarly, both agonist and antagonist drugs are available for several NHRs, providing opportunities to both activate and tune down outputs. Lastly, it has been shown that receptor variants can be engineered that are compromised in their response to endogenous hormones but not specific drugs. A prime example for this is a tamoxifen-controlled estrogen receptor variant with decreased affinity for 17β-estradiol.31

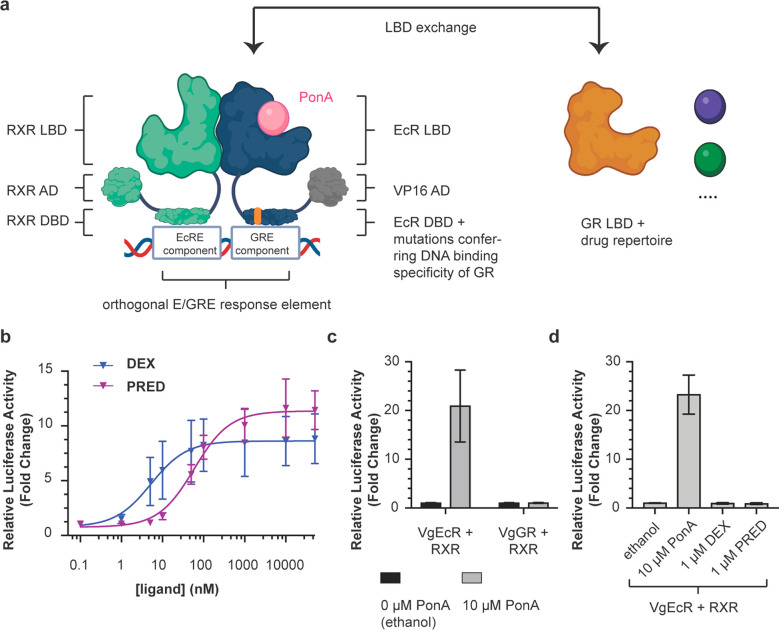

Figure 1.

Modular exchange of the EcR LBD for the GR LBD reprograms the VgEcR scaffold to respond to GR agonists. (a) Illustration of the original VgEcR/RXR system and the LBD exchange approach applied to it here. (b) The engineered VgGR/RXR pair activates luciferase reporter expression in response to the GR agonists dexamethasone (DEX) and prednisolone (PRED) in co-transfected HEK293 cells (n ≥ 5). Curve fits represent a three-parameter dose–response curve (Methods). (c) The engineered VgGR/RXR system is insensitive to PonA, in contrast to the original VgEcR/RXR system (n ≥ 8). (d) The original VgEcR/RXR pair is insensitive to DEX and PRED (n = 6). Error bars represent standard deviation. Cartoons were created with BioRender.com.

Previously, NHRs or their LBDs have been used as ligand-controlled switches of gene expression in mammalian,32−35 plant36 and yeast37 cells. A suitable starting point to engineer novel (multi)drug-controlled responses is provided by a receptor pair30,34 that was engineered for gene regulation in mammalian cells with high orthogonality, i.e., with minimal crosstalk from endogenous receptors or ligands. This pair consists of human retinoid x receptor (RXR) and a chimeric receptor based on ecdysone receptor (EcR) from Drosophila melanogaster, which is induced by the plant-derived ligand ponasterone A (PonA)30,34 (Figure 1a, Figure S1). To achieve orthogonality to endogenous receptors, point mutations were introduced into the DBD of EcR to obtain the binding specificity of human glucocorticoid receptor (GR), while keeping RXR’s native DNA-binding specificity intact. This non-native combination of DBDs allows the dimer to bind to an appropriately engineered DNA sequence consisting of one-half-site each of the ecdysone response element (EcRE) and the glucocorticoid response element (GRE), which is not recognized by endogenous receptors, including native GR homodimers34 (Figure 1a). Besides this mutated DBD, the “VgEcR” chimera also contains the AD of VP16 from Herpes simplex for transcriptional activation instead of the native N-terminal domain of EcR.34 Notably, the presence of both an EcR and an RXR agonist has been shown to produce higher output levels, when compared to an EcR agonist alone,30 potentially enabling multi-input control for engineered derivatives of this system as well. While well-suited for orthogonal gene regulation in human cells by one or more ligands, limitations have been noted with regards to biomedical applications.38 Of particular note, the EcR LBD responds to ligands that are not approved for clinical use and approval in the future was deemed unlikely.38 Similarly, synergistic switch regulation and drugging of human disease targets is not possible with EcR agonists. Lastly, the LBD’s origin from insects could present undesired immunogenicity issues. To address these issues, one could envision replacing the LBD of EcR with NHR-derived LBDs from human drug targets. Yet, it is unclear how amenable the VgEcR receptor is to engineering new ligand specificities and which multi-input behaviors can arise in accordingly engineered receptors.

Here, we investigate the amenability of dimeric NHR-based systems for engineering multidrug-controlled gene outputs. First, we reprogram the VgEcR system to respond to FDA-approved small molecules by modular exchange of the EcR LBD for human NHR-derived LBDs, while maintaining the previously engineered DBDs to retain regulation of an orthogonal target gene in human cells (Figure 1a). Second, we demonstrate that output levels of the engineered receptor pair can be controlled by up to three simultaneously present small-molecule drugs with distinct roles in activating, boosting, and counteracting target gene expression. Our results validate dimeric NHR-based systems as a versatile scaffold pair for programming multidrug-controlled switches of gene expression in mammalian cells and motivate future use of this protein scaffold for engineering gene switches.

Results

Modular Exchange of the EcR LBD for the GR LBD Enables Drug-Controlled Reporter Expression

We first tested whether the VgEcR scaffold could be engineered to respond to agonists of human NHR ligands. We exchanged the EcR LBD with the LBD of human glucocorticoid receptor (GR), which offers a repertoire of approved drug modulators used in various disease applications (Figure 1a). For example, dexamethasone (DEX) is used clinically to mitigate adverse effects in chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–T cell therapies, such as “cytokine release syndrome” (CRS) or neuroinflammation.39,40 We did not exchange RXR’s LBD, as it can form heterodimers with many different NHRs28 and ligand-dependent modulation of the GR-RXR interaction has been observed.29

To generate a chimera between the AD-DBD portion of VgEcR and the LBD of GR, we first built a structural model of an EcR/RXR LBD dimer consisting of a homology model of VgEcR and the structure of human RXR (PDB: 3dzy). We then aligned a crystal structure of the human GR LBD (PDB: 1m2z) to the model to inform chimera design (Figure S2a). We experimentally tested four different variants of a “VgGR” chimera (Figure S2b) through a co-transfection assay34,41,42 in a human model cell line (Figure S3). In particular, we transiently transfected HEK293 cells with three plasmids, namely (1) a pErv3 derivative, which constitutively expresses RXR and VgGR, (2) pEGSH-Luc, in which Firefly luciferase expression is controlled by the previously engineered VgEcR/RXR-dependent promoter, (3) pRL-CMV, which constitutively expresses Renilla luciferase as an internal control and for normalization41 (Figure S3). Relative luciferase expression, as determined by the ratio of Firefly/Renilla luciferase activity and normalized to the response without ligand but appropriate solvent, was measured 20 h after ligand addition.

In this assay, one out of the four tested VgGR chimeras, in which the EcR LBD was exchanged for the full-length GR523–777 LBD (VgGR-01, or simply VgGR from here on), activated reporter expression dependent on DEX in a dose-dependent manner when co-expressed with RXR (Figure 1b, Figure S2b,c). In addition to DEX, VgGR/RXR also responded in a dose-dependent manner to prednisolone (PRED), another drug agonist of GR (Figure 1b). Notably, the system was more sensitive to DEX than to PRED with EC50 values of 5.2 and 58.5 nM respectively, while reporter levels saturated at slightly higher levels for PRED (Figure 1b). As expected, the VgGR/RXR pair did not respond to PonA (Figure 1c, Figure S4), while the original VgEcR/RXR system did not respond to GR ligands, including DEX and PRED (Figure 1d, S5). Taken together, drug-dependent reporter expression from the orthogonal VgEcR/RXR promoter can be reprogrammed by structure-guided modular exchange of the EcR LBD for a drug-responsive human NHR LBD.

Cooperation of RXR and GR Drug Agonists Can Boost VgGR-Induced Reporter Expression

Improved control over target gene expression would be achieved if maximal output levels are only accessible in the simultaneous presence of two different small molecule inputs. Therefore, we tested whether two drug inputs can cooperate in activating gene expression by the engineered VgGR/RXR system. Previously, it has been shown that RXR agonists can enhance DEX-activated reporter expression by GR from a purely GR-specific response element in COS1 cells.29 This effect was also observed when RXR could not bind DNA by itself and was attributed to an enhanced interaction of the GR and RXR LBDs in the presence of an RXR agonist.29 Together with the observation that RXR agonists can enhance PonA-activated expression by VgEcR,30 this suggested that RXR agonists could also boost DEX-activated reporter expression from the orthogonal VgGR/RXR-dependent promoter.

To test this hypothesis, we performed a two-dimensional titration of DEX against the clinically approved RXR agonist drug bexarotene (BEX) (Figure 2a,b). While DEX alone was able to activate reporter expression up to around one order of magnitude (Figure 1b, 2b), BEX alone only activated reporter expression weakly, up to around 2-fold (Figure 2b, Figure S6). Strikingly, BEX was able to boost reporter expression over the entire range of tested DEX concentrations (Figure 2b,c). In particular, BEX potentiated expression levels even at saturating concentrations of DEX (Figure 2b,c). Thus, maximal expression levels under the tested conditions are only accessible if both DEX and BEX are present at sufficiently high concentration.

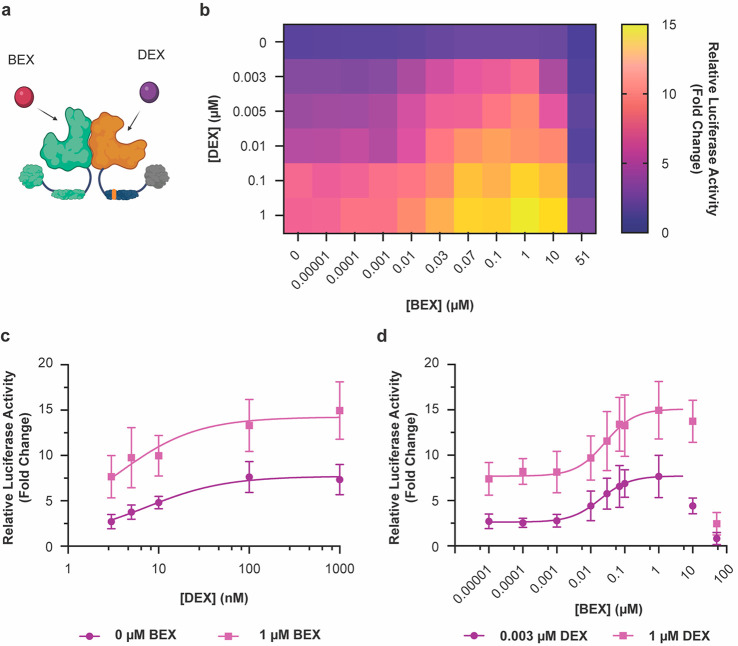

Figure 2.

Multi-input control by cooperation of GR and RXR agonists. (a) Illustration of the 2-input scheme for regulating the VgGR/RXR pair (created with BioRender.com). (b) A simultaneously present RXR agonist can boost DEX-activated responses, as observed by a two-dimensional titration of DEX vs BEX (n ≥ 5). The stark drop-off in reporter expression at the highest BEX concentration is likely due to toxicity, as a similar drop-off was also observed for constitutively expressed Renilla luciferase (Figure S7). (c) BEX shifts DEX dose–response curves to higher output levels (n = 6). (d) DEX shifts BEX dose–response curves to higher output levels (n = 6). Curve fits represent a three-parameter dose–response curve (Methods). The data points at 10 μM and 51 μM BEX were omitted for these curve fits due to the drop-off in reporter expression (see also Figure S7). Error bars represent standard deviation.

When analyzing DEX and BEX dose–responses, the ligands appeared to shift each other’s outputs to higher levels rather than changing the shape of the response curves (Figure 2c,d). Moreover, the total output in the presence of both ligands was higher than the combination of the individual ligand outputs (Figure S6), similar to response behaviors observed in other engineered multi-input/single-output systems.10,11,13 We observed a stark drop in reporter expression at the highest tested concentration of BEX (51 μM). However, as both Firefly and Renilla luciferase levels were drastically decreased under these conditions (Figure S7), we attribute this effect to nonspecific effects and/or ligand toxicity. Although this behavior defines an upper limit for BEX concentration in applications, BEX boosted reporter expression to approximate saturation over a wide window of BEX concentrations in our experiments (from 70 nM to at least 1 μM BEX) (Figure 2b,d).

We also investigated if response parameters of the VgGR/RXR system could additionally be tuned by modular exchange of its transcriptional activation domains (Figure S8a). In particular, we tested variants containing either the H. simplex VP16 domain that is also part of VgEcR,34 the VP16-derived VP64 domain43 and the trimeric fusion protein VPR44 consisting of VP64, human p65 and Rta from Epstein-Barr virus (Figure S8a). Indeed, output levels varied depending on the AD fusion (Figure S8b). Most notably, the VPR domain substantially increased both the basal expression and output levels at saturating agonist concentrations (Figure S8b), while the dynamic range could not be increased relative to the VgGR/RXR system (Figure S8c). Notably, it has previously been observed that strong expression of exogenous genes can impose a substantial burden due to competition of independent processes for limited cellular resources.45,46 As the potent VPR domain has been reported to negatively impact gene expression from a separate promoter in this manner,45 we compared the activities of constitutively expressed Renilla luciferase between cells transfected with plasmids for the different AD fusions (Figure S9). Indeed, we observed a notable decrease in Renilla luciferase activity for the samples containing VPR fusions compared to the other ADs, indicating substantial gene expression burden as in previous use cases45 for this tripartite AD (Figure S9). Thus, output levels may be amplified during normalization for the VPR fusion constructs. This effect will be important to consider for future applications and potential follow-up studies, as has been the case for other instances of gene expression burden.46,47 Nevertheless, our results provide useful insights that may guide future engineering strategies aiming to modulate output levels, dependent on whether either tight repression without ligands or high output levels with ligand are preferred.

Competition between GR Agonist and Antagonist Drugs in the Presence or Absence of an RXR Agonist Drug Enables 3-Input Control over Reporter Expression

In certain scenarios, it may be desirable to attenuate an activated response or tune an agonist’s functional concentration window. Toward these ends, we took advantage of the existing repertoire of clinically approved GR antagonists. In particular, we titrated DEX against RU-486 (mifepristone) to measure reporter expression at varying agonist/antagonist ratios (Figure 3a). As anticipated, we observed maximal expression levels for high concentrations of agonist (DEX) in the absence of antagonist (RU-486) (Figure 3b), and increasing concentrations of RU-486 resulted in a reduction of output levels (Figure 3b,c). We note that, in the absence of DEX, RU-486 elicited an increase in reporter expression, which is consistent with this drug’s reported partial agonist effect48 (Figure S10). Further, as for BEX, a nonspecific decrease in luciferase expression was observed at the highest tested concentration of 51 μM RU-486 (Figure S11).

Figure 3.

Multi-input control by simultaneous presence of GR agonists and antagonists. (a) Illustration of the 3-input scheme for regulating the VgGR/RXR pair (created with BioRender.com). (b) A simultaneously present GR inhibitor can attenuate DEX-activated responses, as observed by a two-dimensional titration of DEX vs RU-486 without BEX (left) or with BEX (right) at a saturating concentration of 1 μM (Figure 2) (n ≥ 5). (c) BEX shifts RU-486 dose–response curves to higher output levels (n = 6). (d) RU-486 modulates agonist sensitivity, as observed by shifting DEX dose–response to higher concentrations (n = 6). The data point at 51 μM RU-486 is omitted from the curve fits and is likely due to toxicity, as a similar drop-off was also observed for constitutively expressed Renilla luciferase (Figure S11). Curve fits represent a three-parameter dose–response curve (Methods). Error bars represent standard deviation.

Besides enabling reduction of DEX-activated output levels, fine-tuning of both agonist and antagonist levels also modulated the agonist sensitivity, i.e., the concentration window in which a change in ligand concentration leads to a detectable change in reporter output (Figure 3d). For example, at increasing concentrations of RU-486, higher DEX concentrations were required to both activate reporter expression and reach saturation (Figure 3d). Furthermore, we compared output reduction in the additional presence and absence of the RXR agonist BEX at a saturating concentration. While the two-dimensional response behaviors had similar properties qualitatively with or without BEX (Figure 3b), output levels were shifted to higher levels in the presence of BEX (Figure 3b,c).

Lastly, we analyzed the temporal evolution of reporter expression and its control through the sequential addition of drug modulators. While DEX alone activated reporter expression to moderate levels after several hours, subsequent addition of BEX allowed for boosting of output levels relative to the single-drug response (Figure S12). Addition of RU-486 to cells previously treated with dexamethasone and bexarotene attenuated reporter expression compared to cells without the antagonist (Figure S12). The observation that RU-486 did not lead to a return of output levels close to the baseline is consistent with our titrations with simultaneously added drugs, in which reporter expression saturated at substantially higher levels in the presence of DEX and BEX than in the presence of no drugs or DEX alone (Figure 3b,c). Moreover, this result is likely exacerbated by the amount of protein and mRNA already produced before addition of the antagonist. In the future, this behavior could be tuned by modulating mRNA stability or protein stability, including through the incorporation of degrons.49

Taken together, these results demonstrate that output levels in the VgGR/RXR system can be controlled by up to three simultaneously present small-molecule ligands with distinct modulatory roles. Thereby, target gene expression can be activated by a GR agonist (DEX), boosted by an RXR agonist (BEX) and attenuated by a GR antagonist (RU-486).

Modular Exchange of the EcR LBD for the Estrogen Receptor LBD Enables Reporter Expression in Response to Additional Drugs

Finally, we tested the amenability of VgEcR for modular exchange of the EcR LBD for a human NHR-derived LBD other than GR. We chose estrogen receptor (ER) due to its clinical relevance as an important drug target and correspondingly large repertoire of approved drug modulators (Figure 4a). In addition, an ER variant (ERT2) has previously been engineered that displays reduced sensitivity to the endogenous ER ligand 17β-estradiol (E2), but responds to the active tamoxifen metabolite 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT).31 Such a variant could be useful for biomedical applications due to its increased orthogonality in a physiological context and has been used in various bioengineering and synthetic biology approaches.18,27,31,50

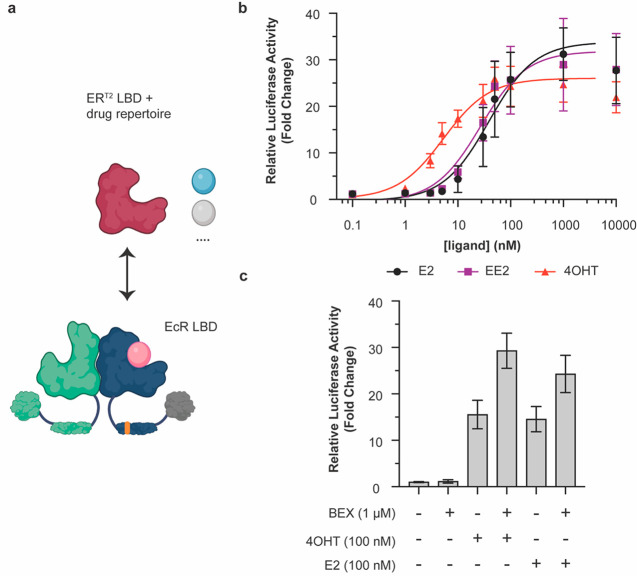

Figure 4.

Modular exchange of the EcR LBD for the ERT2 LBD reprograms the VgEcR scaffold to respond to ER ligands. (a) Schematic of the LBD replacement strategy for obtaining VgERT2/RXR (created with BioRender.com). (b) The engineered VgERT2/RXR pair activates luciferase reporter expression in response to the ER ligands 17β-estradiol (E2), 17α-ethynylestradiol (EE2), and 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) in co-transfected HEK293 cells (n ≥ 5). (c) A simultaneously present RXR agonist (BEX) can boost 4OHT-activated and E2-activated responses for VgERT2/RXR, while having little effect on its own (n = 9). The data points at 10 μM were excluded from the curve fits due to the slight drop-off in reporter levels under these conditions. Curve fits represent a three-parameter dose–response curve (Methods). Error bars represent standard deviation.

As for GR, we generated chimeras of the AD-DBD portion of VgEcR with a small number of ER LBD variants (Figure S13a–c). We generated two chimeras with the ERα LBD based on different fusion points in a structural alignment of the EcR and ERα LBD (PDB: 1ere). Additionally, we designed one chimera with the ERT2 variant, whose domain sequence was adapted from a previously reported fusion to Cre recombinase.51 Here, we generated a fusion of the described ERT2 domain to VgEcR within the latter’s hinge domain between the DBD and LBD. All of the three tested chimeras were capable of activating reporter expression in response to the ER modulators E2, 17α-ethynylestradiol (EE2) and 4OHT from the original VgEcR/RXR response element when co-expressed with RXR (Figure 4b, S13e,f). As expected, none of the ER modulators activated reporter expression by VgEcR/RXR (Figure S5). Interestingly, the basal and maximal output levels, dynamic range and ligand sensitivity of the VgER chimeras varied substantially between the variants (Figure S13e,f). The ERT2 variant displayed the best combination of low basal activity and high fold activation (Figure 4b, S13e,f). Additionally, in contrast to the two variants that had not been engineered for improved drug selectivity, the ERT2 variant was substantially more sensitive to 4OHT (EC50: 5.33 nM) than E2 (EC50: 38.76 nM) or EE2 (EC50: 26.84 nM) (Figure 4b, Figure S13f).

Finally, we tested if BEX could boost output levels of VgERT2/RXR. As for VgGR/RXR, BEX on its own had little effect on reporter expression (Figure 4c). However, in the case of 4OHT- or E2-activated reporter expression, the simultaneous presence of BEX indeed resulted in a boosting of output levels, up to around 2-fold (Figure 4c). Curiously, we only observed BEX-mediated boosting of 4OHT- or E2-activated outputs for the engineered ERT2 variant, but not the ER-02 variant (Figure S14), which lacks the mutations desensitizing the receptor against E2 and is fused to the VgEcR scaffold in a different manner (Figure S13b,c). Nevertheless, taken together our results illustrate that two different NHR pairs (using GR or ER paired with RXR) could be engineered for (multi)drug-controlled gene regulation from the orthogonal VgEcR/RXR promoter.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that novel multidrug-controlled gene regulation from an orthogonal promoter can be programmed via modular domain exchange starting from the VgEcR/RXR system. While exemplifying our strategy by replacing the EcR LBD with the GR or ER LBDs, the approach followed here should be applicable to a variety of other NHR-derived LBDs by harnessing RXR’s inherent capacity to dimerize with many other NHRs.28 Thus, our results encourage a systematic characterization of functional dimers on the scale of the entire NHR protein superfamily, which could identify a breadth of new multidrug-controlled switches that regulate gene outputs from the existing E/GRE response element. Conversely, the use of synthetic DBDs based on engineered zinc-finger domains18,52 could allow NHR-based switches to control target expression from new DNA sites and thus enable higher-order complexity via multiplexing.

Notably, a simple structure-guided modular exchange strategy was sufficient to achieve responsiveness to approved drugs targeting human NHRs. This relative practical ease is an advantage over engineering workflows that involve extensive computational design and high-throughput optimization and should make the engineering of new NHR-derived gene switches more accessible in resource-limited settings. Nevertheless, we note that, while functional variants could be identified out of only a handful of tested variants for both VgGR and VgER(T2), seemingly minor details in our chimera designs had notable effects. For example, truncating the GR LBD by the six most C-terminal amino acids did not result in a functional response (Figure S2). Conversely, all three tested ER variants were functional, but with widely different sensing characteristics (Figure S13). Such potentially unexpected sequence-function relationships indicate that the testing of multiple variants is recommended for the design of future LBD exchange variants. In turn, for a given protein variant, drug modulators exhibited differences in terms of their EC50 and output levels at saturation. A lower drug concentration would be advantageous to avoid undesired physiological effects. On the other hand, a higher dynamic range could allow for more fine-grained tuning of outputs and potentially stronger activation of downstream responses arising from particular target genes when drug concentrations are not limiting. In terms of modular AD exchange, stronger ADs resulted in a simultaneous change in basal and maximal output levels (Figure S8), while also indicating gene expression burden (Figure S9). To address the coupling of basal and maximal activity, LBD variants could be engineered that are conditionally destabilized in the absence of ligand, such that ligand-dependent high outputs are retained, while background levels are selectively reduced. In turn, cellular burden could be mitigated with molecular control strategies that have recently been developed.45−47 In general, our variant-specific observations highlight certain limits to the modularity of natural protein elements and raise the question how the rationally engineered chimeras tested herein would compare to de novo designed protein components in terms of success rate and sensor-actuator performance.

The NHR superfamily provides a rich and diverse drug repertoire, accounting for a significant fraction (16%) of approved small-molecule drugs.53 In addition, human NHR protein domains appear well suited for applications in cellular therapies, such as engineered immune cells.54 In particular, certain NHRs may be synergistically targeted during switching, as they may be overexpressed in cancer. Our study represents a proof-of-principle for the protein engineering aspects and the tested compounds were largely chosen for this purpose. Nevertheless, several factors would be important to consider regarding potential biomedical applications. In principle, the 4OHT-controlled VgERT2/RXR pair could form the basis of an ON-switch driving the expression of a CAR within engineered T-cells applied in ER-positive breast cancer, given progress in the general application of CAR-T cells for the treatment of solid tumors.55 On the other hand, dexamethasone’s immunosuppressive effects and its clinical use in treating CRS and neurotoxicity39,40 render the VgGR/RXR pair more appropriate as an OFF-switch. In this case, one could envision controlling the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines,56 a pro-apoptotic caspase,22 or a transcriptional repressor reducing CAR expression from a different promoter. While ERT2 was previously engineered for reduced sensitivity to endogenous hormones,31 other receptors including GR could benefit from similar approaches regarding their ligand sensitivity. However, although tissue levels of GR ligands depend on a given physiological context, we have not observed substantial background activation for the VgGR/RXR pair compared to VgEcR/RXR (Figure S4). As with other drug-controlled gene switches, limiting factors including the possibility of a drug’s targeting of multiple receptors,57 potential drug–drug interactions and the therapeutic windows of drugs would have to be considered on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, for implementing gene switches in immune cells, it would be important to achieve stable integration and expression of our NHR-based components in clinically relevant cell types and to test if pharmacologically relevant absolute levels of target gene outputs can be achieved via drug induction as compared to their constitutive expression.

Taken together, we have validated the amenability of the VgEcR/RXR pair to engineer novel multidrug-regulated gene expression, which inspires new directions from both a protein engineering and synthetic biology perspective.

Methods

In Silico Design of NHR Chimeras

As no crystal structure of the VgEcR/RXR dimer is available, we built a structural model. For VgEcR, we generated a homology model using Swiss-Model58 with PDB structure 4nqa as template. For human RXR, we used the available PDB structure 3dzy. We then aligned the VgEcR homology model and the RXR crystal structure to an orthologous dimer structure, i.e., the PonA-bound EcR in complex with the RXR homologue Ultraspiracle (USP) from Tribolium castaneum, using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.4.2 Schrödinger, LLC. From this model, we extracted the complex consisting of the newly oriented VgEcR/RXR LBDs as well as PonA. Lastly, we parametrized the PonA ligand and relaxed the ligand-bound dimer structure with Rosetta59 using coordinate constraints.

To generate VgGR, the DEX-bound human GR LBD from PDB structure 1m2z was aligned to the PonA-bound VgEcR LBD within our VgEcR/RXR LBD dimer model. Four variants were tested, in all of which the GR LBD, starting at GR residue 523, was inserted at the C-terminus of VgEcR residue 293 (Figure S2a,b). All four variants contained the F602S mutation in GR, which was also part of the crystallized protein and is thought to increase solubility.60 VgGR (VgGR-01) contained the full-length LBD (GR523–777/F602S). VgGR-02 encompasses VgGR-01 truncated by the C-terminal loop (VgGR523–771/F602S). VgGR-03 additionally contains the I628A mutation, which was described to prevent GR homodimerization60 (VgGR523–771/F602S/I628A). VgGR-04 is a chimera of the VgGR-03 LBD with the central interface helix of VgEcR (GR523–711/F602S/I628A-VgEcR487–520-GR751–771), as observed in our alignment (Figure S2a).

To generate VgER-01 and -02, the 17β-estradiol-bound ER LBD from PDB structure 1ere was aligned to the PonA-bound VgEcR LBD (Figure S13a). The resulting domain orientation was reasonably well recapitulated by AlphaFold2-multimer61/ColabFold,62 although a stretch at ER’s C-terminus appeared disordered (Figure S13d). ER-01 and ER-02 differed with respect to their fusion to the VgEcR scaffold (Figure S13c). In ER-01, the N-terminal helix of ER was retained and the N-terminus of the EcR LBD was truncated to keep as much of the ER LBD intact as possible, resulting in VgEcR1–293-ER305–595. In ER-02, the N-terminal helix of ER was truncated and the remaining LBD thus merged more seamlessly into VgEcR’s N-terminal helix, resulting in VgEcR1–297-ER312–595. For generating VgERT2, the final ERT2 sequence length was determined based on a previous successful fusion to Cre recombinase.51 An alignment of the 4OHT-bound ER LBD (PDB structure 3ert) appeared globally similar to the one bound to E2 (Figure S13a). As the functional ERT2 sequence within the context of the Cre fusion contained an additional N-terminal portion of ER not part of the LBD’s crystal structure, a sequence alignment was performed with Clustal Omega.63 This alignment suggested an appropriate insertion point of the ERT2 sequence within the hinge domain of VgEcR connecting the DBD and LBD, resulting in VgEcR1–268-ER283–594/G400V/M543A/L544A.

AD variants were designed through simple replacement of the VP16 sequence of VgEcR (residues 12–89) or the N-terminal domain of RXR (residues 2–99) with the tested AD sequences. Details are summarized in the Supporting Information “Construct Details”.

DNA Constructs

pErv3,64 pEGSH,64 and pEGSH-Luc64 were obtained as part of the “Complete Control Vector Kit” from Agilent Technologies Inc. (Catalog number 217468). pRL-CMV was obtained from Promega Corporation. First, we modified pErv3, such that VgEcR and RXR (derivatives) are both tagged. While we determined an N-terminal myc tag within the VgEcR ORF, we did not identify tags in RXR. Therefore, we generated N- and C-terminal fusions of RXR with 3x-FLAG or 3-HA tags, all four of which produced a functional response to PonA when co-expressed with VgEcR (Figure S1). Unless stated otherwise, all experiments were performed with RXR-3xFLAG (simply referred to as RXR here) or derivatives thereof. As an exception, during prototyping of GR variants, VgGR-02, VgGR-03, and VgGR-04 were co-expressed from their vectors with 3xHA-RXR. To generate the pErv3 derivatives expressing RXR-3xFLAG and RXR-3xHA, we used the Gibson Assembly master mix (NEB) with PCR products amplified from pErv3 and custom gene fragments (IDT gBlocks) for the tags. To generate the pErv3 derivatives expressing 3xFLAG-RXR and 3xHA-RXR, restriction-based cloning using pErv3 and custom gene fragments (IDT gBlocks) was performed. pErv3 derivatives expressing GR, ER and AD variants were obtained with PCR-amplified gene fragments (IDT gBlocks) using restriction-based cloning with enzymes purchased from NEB. Information on tested plasmids, including DNA coding sequences and protein sequences of VgEcR and RXR (derivatives) as well as details of their construction (enzymes, gene fragment and primer sequences) are summarized in the Supporting Information “Construct Details” and tabs 1–3 therein.

Small Molecules

PonA was obtained from Agilent Technologies Inc./Invitrogen. Dexamethasone, prednisolone, E2, EE2, and 4OHT were obtained from MilliporeSigma. Bexarotene was obtained from Thermo Scientific. RU-486 was obtained from Torcis Bioscience. Stock solutions in ethanol were prepared for all compounds at 100× of their final assay concentrations.

Transient Transfection of HEK293 Cells and Luciferase Reporter Assays

The luciferase reporter assay was adapted from previous protocols.41,42 First, HEK293 cells (obtained from the UCSF Cell Culture Core Facility) were seeded in a sterile, tissue culture treated, white, flat-bottom 96-well microplate (Corning, product number 3917) at a density of 3 × 104 cells per well in 100 μL DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, cells were transiently transfected on the next day using lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfection mixes were prepared, such that addition of 10 μL of DNA:lipid complexes in DMEM resulted in 24 ng pErv3 derivative, 95 ng pEGSH-Luc, 2 ng pRL-CMV, and 0.4 μL lipofectamine 2000 reagent per well. Cells in background wells were transfected with 95 ng empty pEGSH vector. Upon incubation for approximately 24 h, the media was exchanged for 75 μL DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS per well. On the following day, small molecules from 100× stock solutions, or ethanol for measuring basal expression, were added to the cells. Finally, after incubation for 20 h, Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity were measured in a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek) using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For analyzing the temporal evolution of reporter expression dependent on the sequential addition of drugs, cells were seeded in one plate per time point, as the luminescence assay involved cell lysis. After transfection and media exchange as above, dexamethasone was added to all plates at the start of the time course. After measuring luciferase activity in one plate after approximately 9 h, bexarotene was added to the remaining plates. After measuring luciferase activity in another plate after approximately 23 h, RU-486 was added to the remaining plates and luciferase activity measured in them after approximately 47, 72, and 95 h. In all plates, a portion of wells was also used to measure responses to only a subset of drugs for comparison and without drugs but solvent for internal normalization.

Data Analysis

For both the Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities in a given sample well, an average of the reads from the background wells was subtracted. The Firefly/Renilla Luc Ratio was then calculated from these background-corrected levels. The relative luciferase activity (fold change) represents the Firefly/Renilla Luc Ratio in the presence of a small molecule, normalized by the Firefly/Renilla Luc ratio in the absence of small molecules but with ethanol. To calculate this property, we divided the Firefly/Renilla Luc Ratio of every drug-containing sample well by an average of the Firefly/Renilla Luc Ratio for same-day replicate wells without drug. The plotted values were then obtained by averaging relative luciferase activities from same/multiday replicates.

Dose–response curves, heat maps, and bar plots were generated with Prism 9 (GraphPad). Nonlinear curve fits were obtained with the built-in “Agonist vs. response (three parameters)” [Y = Bottom + X·(Top – Bottom)/(EC50 + X)] and “Inhibitor vs. response (three parameters)” [Y = Bottom + (Top – Bottom)/(1 + (X/IC50))] equations. EC50 estimates were obtained from such curve fits to relative luciferase activity data.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Kortemme lab as well as Prof. Kole Roybal (UCSF) for helpful suggestions and discussions. This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Grants R01GM110089 and R35GM145236 to T.K.; S.K. was supported by a Postdoctoral Independent Research Grant of the UCSF “Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research” (PBBR), which is partially funded by the Sandler foundation, and a Li foundation endowed fellowship. Tanja Kortemme is a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Senior Investigator.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- EcR

ecdysone receptor

- RXR

retinoid x receptor

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- DBD

DNA binding domain

- AD

activation domain

- NHR

nuclear hormone receptor

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- PonA

ponasterone A

- DEX

dexamethasone

- PRED

prednisolone

- BEX

bexarotene

- E2

17β-estradiol

- EE2

17α-ethynylestradiol

- 4OHT

4-hydroxytamoxifen

- E/GRE

ecdysone/glucocorticoid response element

- USP

ultraspiracle.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssynbio.3c00080.

Author Contributions

S.K. and T.K. conceived the project. S.K. performed in silico chimera design, cloning, mammalian cell reporter experiments, and data analysis. S.K. and N.P. built the structural model of the VgEcR/RXR dimer. N.P. performed cloning and preliminary functional characterization of tagged RXR variants. Y.Z. provided technical help with initial cell culture experiments. S.K. wrote the manuscript draft with contributions from T.K. and N.P.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kretschmer S.; Kortemme T. Advances in the Computational Design of Small-Molecule-Controlled Protein-Based Circuits for Synthetic Biology. P Ieee 2022, 110 (5), 659–674. 10.1109/JPROC.2022.3157898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri M.; Fussenegger M. Therapeutic cell engineering: designing programmable synthetic genetic circuits in mammalian cells. Protein Cell 2022, 13, 476. 10.1007/s13238-021-00876-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Elowitz M. B. Programmable protein circuit design. Cell 2021, 184 (9), 2284–2301. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada T.; DiAndreth B.; Teague B.; Weiss R. Programming gene and engineered-cell therapies with synthetic biology. Science 2018, 10.1126/science.aad1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata F.; Matyjaszkiewicz A.; Fiore G.; Grierson C. S.; Marucci L.; di Bernardo M.; Savery N. J. An Orthogonal Multi-input Integration System to Control Gene Expression in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 2017, 6 (10), 1816–1824. 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel R.; Rubens J. R.; Sarpeshkar R.; Lu T. K. Synthetic analog computation in living cells. Nature 2013, 497 (7451), 619–23. 10.1038/nature12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foight G. W.; Wang Z.; Wei C. T.; Greisen P. Jr; Warner K. M.; Cunningham-Bryant D.; Park K.; Brunette T. J.; Sheffler W.; Baker D.; Maly D. J. Multi-input chemical control of protein dimerization for programming graded cellular responses. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37 (10), 1209–1216. 10.1038/s41587-019-0242-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. S.; Wong N. M.; Tague E.; Ngo J. T.; Khalil A. S.; Wong W. W. High-performance multiplex drug-gated CAR circuits. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 1294. 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T.; DeRose R.; Suarez A.; Ueno T.; Chen M.; Sun T. P.; Wolfgang M. J.; Mukherjee C.; Meyers D. J.; Inoue T. Rapid and orthogonal logic gating with a gibberellin-induced dimerization system. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8 (5), 465–70. 10.1038/nchembio.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon J. J.; Kandula V.; Hong M.; Donahue P. S.; Boucher J. D.; Bagheri N.; Leonard J. N. Model-guided design of mammalian genetic programs. Sci. Adv. 2021, 10.1126/sciadv.abe9375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shis D. L.; Hussain F.; Meinhardt S.; Swint-Kruse L.; Bennett M. R. Modular, multi-input transcriptional logic gating with orthogonal LacI/GalR family chimeras. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014, 3 (9), 645–51. 10.1021/sb500262f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg B. H.; Pham N. T. H.; Caraballo L. D.; Lozanoski T.; Engel A.; Bhatia S.; Wong W. W. Large-scale design of robust genetic circuits with multiple inputs and outputs for mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35 (5), 453–462. 10.1038/nbt.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong D. M.; Cinar S.; Shis D. L.; Josic K.; Ott W.; Bennett M. R. Predicting Transcriptional Output of Synthetic Multi-input Promoters. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7 (8), 1834–1843. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Z. B.; Martinko A. J.; Nguyen D. P.; Wells J. A. Human antibody-based chemically induced dimerizers for cell therapeutic applications. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14 (2), 112–117. 10.1038/nchembio.2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs C. L.; Badiee R. K.; Lin M. Z. StaPLs: versatile genetically encoded modules for engineering drug-inducible proteins. Nat. Methods 2018, 15 (7), 523–526. 10.1038/s41592-018-0041-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan M.; Scarfo I.; Larson R. C.; Walker A.; Schmidts A.; Guirguis A. A.; Gasser J. A.; Slabicki M.; Bouffard A. A.; Castano A. P.; Kann M. C.; Cabral M. L.; Tepper A.; Grinshpun D. E.; Sperling A. S.; Kyung T.; Sievers Q. L.; Birnbaum M. E.; Maus M. V.; Ebert B. L. Reversible ON- and OFF-switch chimeric antigen receptors controlled by lenalidomide. Sci. Transl Med. 2021, 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labanieh L.; Majzner R. G.; Klysz D.; Sotillo E.; Fisher C. J.; Vilches-Moure J. G.; Pacheco K. Z. B.; Malipatlolla M.; Xu P.; Hui J. H.; Murty T.; Theruvath J.; Mehta N.; Yamada-Hunter S. A.; Weber E. W.; Heitzeneder S.; Parker K. R.; Satpathy A. T.; Chang H. Y.; Lin M. Z.; Cochran J. R.; Mackall C. L. Enhanced safety and efficacy of protease-regulated CAR-T cell receptors. Cell 2022, 185 (10), 1745–1763. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. S.; Israni D. V.; Gagnon K. A.; Gan K. A.; Raymond M. H.; Sander J. D.; Roybal K. T.; Joung J. K.; Wong W. W.; Khalil A. S. Multidimensional control of therapeutic human cell function with synthetic gene circuits. Science 2022, 378 (6625), 1227–1234. 10.1126/science.ade0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman S. A.; Wang L. C.; Moon E. K.; Khire U. R.; Albelda S. M.; Milone M. C. Ligand-Induced Degradation of a CAR Permits Reversible Remote Control of CAR T Cell Activity In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Ther 2020, 28 (7), 1600–1613. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakemura R.; Terakura S.; Watanabe K.; Julamanee J.; Takagi E.; Miyao K.; Koyama D.; Goto T.; Hanajiri R.; Nishida T.; Murata M.; Kiyoi H. A Tet-On Inducible System for Controlling CD19-Chimeric Antigen Receptor Expression upon Drug Administration. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016, 4 (8), 658–68. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui M.; Tous C.; Wong W. W. Small molecule-inducible gene regulatory systems in mammalian cells: progress and design principles. Curr. Opin Biotechnol 2022, 78, 102823. 10.1016/j.copbio.2022.102823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straathof K. C.; Pule M. A.; Yotnda P.; Dotti G.; Vanin E. F.; Brenner M. K.; Heslop H. E.; Spencer D. M.; Rooney C. M. An inducible caspase 9 safety switch for T-cell therapy. Blood 2005, 105 (11), 4247–54. 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. Y.; Roybal K. T.; Puchner E. M.; Onuffer J.; Lim W. A. Remote control of therapeutic T cells through a small molecule-gated chimeric receptor. Science 2015, 350 (6258), aab4077. 10.1126/science.aab4077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagyu S.; Hoyos V.; Del Bufalo F.; Brenner M. K. An Inducible Caspase-9 Suicide Gene to Improve the Safety of Therapy Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Mol. Ther 2015, 23 (9), 1475–85. 10.1038/mt.2015.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajc C. U.; Dobersberger M.; Schaffner I.; Mlynek G.; Puhringer D.; Salzer B.; Djinovic-Carugo K.; Steinberger P.; De Sousa Linhares A.; Yang N. J.; Obinger C.; Holter W.; Traxlmayr M. W.; Lehner M. A conformation-specific ON-switch for controlling CAR T cells with an orally available drug. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117 (26), 14926–14935. 10.1073/pnas.1911154117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetsche B.; Volz S. E.; Zhang F. A split-Cas9 architecture for inducible genome editing and transcription modulation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33 (2), 139–42. 10.1038/nbt.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C.; Zhao Y.; Zhang J.; Lu J.; Chen L.; Zhang Y.; Ying Y.; Xu J.; Wei S.; Wang Y. HIT-Cas9: A CRISPR/Cas9 Genome-Editing Device under Tight and Effective Drug Control. Mol. Ther Nucleic Acids 2018, 13, 208–219. 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weikum E. R.; Liu X.; Ortlund E. A. The nuclear receptor superfamily: A structural perspective. Protein Sci. 2018, 27 (11), 1876–1892. 10.1002/pro.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth K.; Sarang Z.; Scholtz B.; Brazda P.; Ghyselinck N.; Chambon P.; Fesus L.; Szondy Z. Retinoids enhance glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of T cells by facilitating glucocorticoid receptor-mediated transcription. Cell Death Differ. 2011, 18 (5), 783–92. 10.1038/cdd.2010.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez E.; Nelson M. C.; Eshelman B.; Banayo E.; Koder A.; Cho G. J.; Evans R. M. Identification of ligands and coligands for the ecdysone-regulated gene switch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97 (26), 14512–14517. 10.1073/pnas.260499497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil R.; Wagner J.; Metzger D.; Chambon P. Regulation of Cre recombinase activity by mutated estrogen receptor ligand-binding domains. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 237 (3), 752–7. 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman H. M.; Yee A.; Diggelmann H.; Hastings J. C.; Tal-Singer R.; Seidel-Dugan C. A.; Eisenberg R. J.; Cohen G. H. Use of a glucocorticoid-inducible promoter for expression of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein gC1, a cytotoxic protein in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989, 9 (6), 2303–2314. 10.1128/mcb.9.6.2303-2314.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko M. S.H.; Naomi T.; Norifumi S.; Toshiya T. An auto-inducible vector conferring high glucocorticoid inducibility upon stable transformant cells. Gene 1989, 84 (2), 383–389. 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90512-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- No D.; Yao T. P.; Evans R. M. Ecdysone-inducible gene expression in mammalian cells and transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93 (8), 3346–51. 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braselmann S.; Graninger P.; Busslinger M. A selective transcriptional induction system for mammalian cells based on Gal4-estrogen receptor fusion proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993, 90 (5), 1657–61. 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schena M.; Lloyd A. M.; Davis R. W. A steroid-inducible gene expression system for plant cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991, 88 (23), 10421–5. 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvion J. F.; Havaux-Copf B.; Picard D. Fusion of GAL4-VP16 to a steroid-binding domain provides a tool for gratuitous induction of galactose-responsive genes in yeast. Gene 1993, 131 (1), 129–34. 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90681-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fussenegger M. The impact of mammalian gene regulation concepts on functional genomic research, metabolic engineering, and advanced gene therapies. Biotechnol. Prog. 2001, 17 (1), 1–51. 10.1021/bp000129c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulier B.; Enserink J. M.; Walchli S. Pharmacologic Control of CAR T Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22 (9), 4320. 10.3390/ijms22094320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelapu S. S.; Tummala S.; Kebriaei P.; Wierda W.; Gutierrez C.; Locke F. L.; Komanduri K. V.; Lin Y.; Jain N.; Daver N.; Westin J.; Gulbis A. M.; Loghin M. E.; de Groot J. F.; Adkins S.; Davis S. E.; Rezvani K.; Hwu P.; Shpall E. J. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy - assessment and management of toxicities. Nat. Rev. Clin Oncol 2018, 15 (1), 47–62. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karzenowski D.; Potter D. W.; Padidam M. Inducible control of transgene expression with ecdysone receptor: gene switches with high sensitivity, robust expression, and reduced size. Biotechniques 2005, 39 (2), 191–192. 194, 196 passim 10.2144/05392ST01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto N.; Viswanatha R.; Bittar R.; Li Z.; Haga-Yamanaka S.; Perrimon N.; Yamanaka N. A Membrane Transporter Is Required for Steroid Hormone Uptake in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 2018, 47 (3), 294–305. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli R. R.; Segal D. J.; Dreier B.; Barbas C. F. 3rd Toward controlling gene expression at will: specific regulation of the erbB-2/HER-2 promoter by using polydactyl zinc finger proteins constructed from modular building blocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95 (25), 14628–33. 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez A.; Scheiman J.; Vora S.; Pruitt B. W.; Tuttle M.; E P. R. I.; Lin S.; Kiani S.; Guzman C. D.; Wiegand D. J.; Ter-Ovanesyan D.; Braff J. L.; Davidsohn N.; Housden B. E.; Perrimon N.; Weiss R.; Aach J.; Collins J. J.; Church G. M. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated transcriptional programming. Nat. Methods 2015, 12 (4), 326–328. 10.1038/nmeth.3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. D.; Qian Y.; Siciliano V.; DiAndreth B.; Huh J.; Weiss R.; Del Vecchio D. An endoribonuclease-based feedforward controller for decoupling resource-limited genetic modules in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 5690. 10.1038/s41467-020-19126-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei T.; Cella F.; Tedeschi F.; Gutierrez J.; Stan G. B.; Khammash M.; Siciliano V. Characterization and mitigation of gene expression burden in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 4641. 10.1038/s41467-020-18392-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella F.; Perrino G.; Tedeschi F.; Viero G.; Bosia C.; Stan G. B.; Siciliano V. MIRELLA: a mathematical model explains the effect of microRNA-mediated synthetic genes regulation on intracellular resource allocation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51 (7), 3452–3464. 10.1093/nar/gkad151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Jonklaas J.; Danielsen M. The glucocorticoid agonist activities of mifepristone (RU486) and progesterone are dependent on glucocorticoid receptor levels but not on EC50 values. Steroids 2007, 72 (6–7), 600–8. 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin H.; Muller M.; Tigges M.; Scheller L.; Lang M.; Fussenegger M. A modular degron library for synthetic circuits in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 2013. 10.1038/s41467-019-09974-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. E.; Zhou W.; Thangaraj J.; Kyriakakis P.; Wu Y.; Huang Z.; Ho P.; Pan Y.; Limsakul P.; Xu X.; Wang Y. An AND-Gated Drug and Photoactivatable Cre-loxP System for Spatiotemporal Control in Cell-Based Therapeutics. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8 (10), 2359–2371. 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerberg A. A.; Stewart S.; Stankunas K. Spatial and temporal control of transgene expression in zebrafish. PLoS One 2014, 9 (3), e92217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue P. S.; Draut J. W.; Muldoon J. J.; Edelstein H. I.; Bagheri N.; Leonard J. N. The COMET toolkit for composing customizable genetic programs in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 779. 10.1038/s41467-019-14147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos R.; Ursu O.; Gaulton A.; Bento A. P.; Donadi R. S.; Bologa C. G.; Karlsson A.; Al-Lazikani B.; Hersey A.; Oprea T. I.; Overington J. P. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2017, 16 (1), 19–34. 10.1038/nrd.2016.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim W. A.; June C. H. The Principles of Engineering Immune Cells to Treat Cancer. Cell 2017, 168 (4), 724–740. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labanieh L.; Majzner R. G.; Mackall C. L. Programming CAR-T cells to kill cancer. Nat. Biomed Eng. 2018, 2 (6), 377–391. 10.1038/s41551-018-0235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opal S. M.; DePalo V. A. Anti-inflammatory cytokines. Chest 2000, 117 (4), 1162–72. 10.1378/chest.117.4.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt S. A.; Edwards D. P. Mechanism of action of progesterone antagonists. Exp Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2002, 227 (11), 969–80. 10.1177/153537020222701104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A.; Bertoni M.; Bienert S.; Studer G.; Tauriello G.; Gumienny R.; Heer F. T.; de Beer T. A. P.; Rempfer C.; Bordoli L.; Lepore R.; Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (W1), W296–W303. 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leman J. K.; Weitzner B. D.; Lewis S. M.; Adolf-Bryfogle J.; Alam N.; Alford R. F.; Aprahamian M.; Baker D.; Barlow K. A.; Barth P.; Basanta B.; Bender B. J.; Blacklock K.; Bonet J.; Boyken S. E.; Bradley P.; Bystroff C.; Conway P.; Cooper S.; Correia B. E.; Coventry B.; Das R.; De Jong R. M.; DiMaio F.; Dsilva L.; Dunbrack R.; Ford A. S.; Frenz B.; Fu D. Y.; Geniesse C.; Goldschmidt L.; Gowthaman R.; Gray J. J.; Gront D.; Guffy S.; Horowitz S.; Huang P. S.; Huber T.; Jacobs T. M.; Jeliazkov J. R.; Johnson D. K.; Kappel K.; Karanicolas J.; Khakzad H.; Khar K. R.; Khare S. D.; Khatib F.; Khramushin A.; King I. C.; Kleffner R.; Koepnick B.; Kortemme T.; Kuenze G.; Kuhlman B.; Kuroda D.; Labonte J. W.; Lai J. K.; Lapidoth G.; Leaver-Fay A.; Lindert S.; Linsky T.; London N.; Lubin J. H.; Lyskov S.; Maguire J.; Malmstrom L.; Marcos E.; Marcu O.; Marze N. A.; Meiler J.; Moretti R.; Mulligan V. K.; Nerli S.; Norn C.; O’Conchuir S.; Ollikainen N.; Ovchinnikov S.; Pacella M. S.; Pan X.; Park H.; Pavlovicz R. E.; Pethe M.; Pierce B. G.; Pilla K. B.; Raveh B.; Renfrew P. D.; Burman S. S. R.; Rubenstein A.; Sauer M. F.; Scheck A.; Schief W.; Schueler-Furman O.; Sedan Y.; Sevy A. M.; Sgourakis N. G.; Shi L.; Siegel J. B.; Silva D. A.; Smith S.; Song Y.; Stein A.; Szegedy M.; Teets F. D.; Thyme S. B.; Wang R. Y.; Watkins A.; Zimmerman L.; Bonneau R. Macromolecular modeling and design in Rosetta: recent methods and frameworks. Nat. Methods 2020, 17 (7), 665–680. 10.1038/s41592-020-0848-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe R. K.; Montana V. G.; Stanley T. B.; Delves C. J.; Apolito C. J.; McKee D. D.; Consler T. G.; Parks D. J.; Stewart E. L.; Willson T. M.; Lambert M. H.; Moore J. T.; Pearce K. H.; Xu H. E. Crystal structure of the glucocorticoid receptor ligand binding domain reveals a novel mode of receptor dimerization and coactivator recognition. Cell 2002, 110 (1), 93–105. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R.; O’Neill M.; Pritzel A.; Antropova N.; Senior A.; Green T.; Žídek A.; Bates R.; Blackwell S.; Yim J.. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. BioRxiv, March 10, 2022. 10.1101/2021.10.04.463034. [DOI]

- Mirdita M.; Schutze K.; Moriwaki Y.; Heo L.; Ovchinnikov S.; Steinegger M. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19 (6), 679–682. 10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira F.; Pearce M.; Tivey A. R. N.; Basutkar P.; Lee J.; Edbali O.; Madhusoodanan N.; Kolesnikov A.; Lopez R. Search and sequence analysis tools services from EMBL-EBI in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50 (W1), W276–9. 10.1093/nar/gkac240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyborski D. L.; Bauer J. C.; Vaillancourt P. Bicistronic expression of ecdysone-inducible receptors in mammalian cells. Biotechniques 2001, 31 (3), 618–20. 622, 624 10.2144/01313pf02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.