Abstract

Genome editing tools, through the disruption of an organism’s native genetic material or the introduction of non-native DNA, facilitate functional investigations to link genotypes to phenotypes. Transposons have been instrumental genetic tools in microbiology, enabling genome-wide, randomized disruption of genes and insertions of new genetic elements. Due to this randomness, identifying and isolating particular transposon mutants (i.e., those with modifications at a genetic locus of interest) can be laborious, often requiring one to sift through hundreds or thousands of mutants. Programmable, site-specific targeting of transposons became possible with recently described CRISPR-associated transposase (CASTs) systems, allowing the streamlined recovery of desired mutants in a single step. Like other CRISPR-derived systems, CASTs can be programmed by guide-RNA that is transcribed from short DNA sequence(s). Here, we describe a CAST system and demonstrate its function in bacteria from three classes of Proteobacteria. A dual plasmid strategy is demonstrated: (i) CAST genes are expressed from a broad-host-range replicative plasmid and (ii) guide-RNA and transposon are encoded on a high-copy, suicidal pUC plasmid. Using our CAST system, single-gene disruptions were performed with on-target efficiencies approaching 100% in Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria (Burkholderia thailandensis and Pseudomonas putida, respectively). We also report a peak efficiency of 45% in the Alphaproteobacterium Agrobacterium fabrum. In B. thailandensis, we performed simultaneous co-integration of transposons at two different target sites, demonstrating CAST’s utility in multilocus strategies. The CAST system is also capable of high-efficiency large transposon insertion totaling over 11 kbp in all three bacteria tested. Lastly, the dual plasmid system allowed for iterative transposon mutagenesis in all three bacteria without loss of efficiency. Given these iterative capabilities and large payload capacity, this system will be helpful for genome engineering experiments across several fields of research.

Keywords: CRISPR-associated transposase, CRISPR, transposon mutagenesis, proteobacteria, targeted mutagenesis

Introduction

For the past four decades, site-specific genome editing has been instrumental in elucidating many aspects of bacterial physiology and metabolism, facilitating diverse applications in metabolic engineering.1−4 The ability to integrate genes into the chromosome has enabled heterologous gene expression to produce biofuels, medicines, pesticides, and other high-value products.3,5−8 In bacteria, targeted genome editing has been traditionally performed through homologous recombination (HR).9−11 While HR is a reliable method in some bacteria, it is often inefficient and laborious. HR requires considerable amounts of customized editing template DNA and large numbers of cells for transformation. As long regions of homology must be cloned into a suicide vector, construction of the editing template can be a complicated process where multistep or multipiece assemblies are often required.12 Multiple rounds of selection and counterselection are sometimes needed to proceed from single to double-crossover mutants.

To improve upon these HR limitations, recombineering strategies that utilize phage recombinases to integrate DNA have been adopted. In some bacteria, like Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, recombineering systems enable high-efficiency integration into the genome from linear dsDNA and ssDNA.13−15 Similarly, genome editing systems that use nucleolytic CRISPR-Cas enzymes to increase HR efficiency (i.e., to increase the number of correct mutants derived from the method) have been described. These strategies include the use of CRISPR-Cas to stimulate HR from donor DNA or to counter-select nonmutated cells.16,17 While these systems are often efficient and useful, portability to nonmodel organisms can be challenging, as host-specific requirements necessitate modification of the plasmids.

Though most transposons are not inherently site-specific, they enable high-throughput forward genomic studies, disrupting genomic loci with easily identifiable insertions.18−20 Transposon sequencing (Tn-Seq) methods combine next-generation sequencing with transposon mutagenesis for high-throughput genome-wide studies of cell fitness, genetic interaction, and gene function.20−24 While most transposons insert their payload DNA randomly or semi-randomly, the Tn7 transposon consistently integrates into the same site. This integration is facilitated by elements TnsABCD:25 TnsAB acts as a heteromeric transposase26 and TnsD mediates the site-specific recognition.27 TnsD recognizes a conserved attachment site found across different taxonomic classes of bacteria28 and allows insertion of payload downstream of the conserved gene glmS. TnsD-mediated integration has not been observed to integrate at other genomic sites.29 While Tn7 is highly useful for efficient genomic integration of DNA, the inability to program the insertion location limits its genome editing capacity. A recent phylogenetic analysis found widespread Tn7-like elements in diverse bacterial families, sometimes genomically adjacent to CRISPR-Cas genes.30,31 These associations of Tn7-like elements and CRISPR-Cas genes suggested that native systems of CRISPR-guided transposable elements exist.

Recently, two of the identified novel CRISPR-associated transposase systems were demonstrated to function as site-programable transposases with high on-target efficiency and large DNA payload capacity in E. coli (>10 Kbp) and Shewanella oneidensis (>30 Kbp).32−36 Both systems use Tn7-like elements, which include the proteins TnsBCD,25,37 in complex with a Cas effector. The Scytonema hofmannii (ShCAST) system comprises a DNA targeting type V-K Cas12k in complex with the transposition proteins TnsB, TnsC, and TniQ (a homolog of TnsD).38 A second system, from Vibrio cholerae, uses a type I-F CRISPR-Cas cascade and is similarly coupled with TniQ. The ShCAST system has been mechanistically defined and shown to associate in a modular fashion.39,40 In this association, target-site-associated proteins are first recruited, including Cas12K, TniQ, and TnsC (as multiple protomers), ending with the recruitment of TnsB, which contains the transposon and stimulates ATP hydrolysis for integration.39 The V. cholerae CAST, dubbed INTEGRATE, was later shown to enable site-specific transposon integration in Klebsiella oxytoca, Pseudomonas putida, and Agrobacterium fabrum.(36,41) For both CASTs, no host-specific genes are needed, potentially allowing for broader deployment than is typical for other CRISPR-enabled tools used in genome editing. In addition to the high efficiency of insertion, the ease with which the guide-RNA target can be changed to new targets makes this system extremely portable, enabling fast and efficient mutagenesis.

One caveat observed in E. coli is that high overexpression of the CAST genes increased off-target insertions.32 This problem is easily corrected by tuning gene expression with well-characterized promoters or by altering the inducer concentrations. Outside of E. coli, the ability to precisely modulate gene expression remains limited, making control of recombinant gene expression difficult.42,43 Gene expression is also dependent on the growth phase of the organism (e.g., lag, log, and stationary phases),44,45 so experimental strategies may opt to limit the study to a particular growth phase as an orthogonal means of control. Although well-characterized toolboxes exist for some organisms,46−48 broad-host-range toolboxes show promise for identifying inducible promoters in different bacteria that can later be adopted for the control of gene expression.49

We sought to develop a fast, easy-to-use, and iterative system for targeted transposon mutagenesis in three taxonomic classes of Proteobacteria. We chose to investigate the CAST system from S. hofmannii because it has a single Cas effector protein and a relatively short functional target sequence of 24 bp coupled with an engineered single-guide RNA (sgRNA). We built several versions of the helper and donor plasmids and tested them in bacteria from three taxonomic classes of Proteobacteria (recently changed to Pseudomonadota50) relevant to biotechnology, plant engineering, pathogen modeling, and bioremediation: strains A. fabrum C58 (Af, previously A. tumefaciens(51)), Burkholderia thailandensis E264 (Bt), and P. putida KT2440 (Pp). The system was initially tested in a common target site across all three bacteria to select an efficient helper donor combination in each strain. Subsequently, each strain was individually tested by targeting native genes related to amino acid synthesis and verified through Tn-Seq. The capabilities of the system were further tested through larger-size transposons that carried the violacein expression pathway. Simultaneous co-integration and iterative integration into different target sites was achieved with high on-target efficiency. Altogether, this system was employed in various microorganisms and allowed the multiplex insertion of large payloads with high on-target efficiency. It requires minimal setup, with a fast one-step cloning reaction for re-targeting of the target site. This work also shows the first instance of Cas-associated transposon integration in B. thailandensis, expanding its genetic toolbox.

Results

Design of Broad-Host-Range Plasmids and Reporter Strains

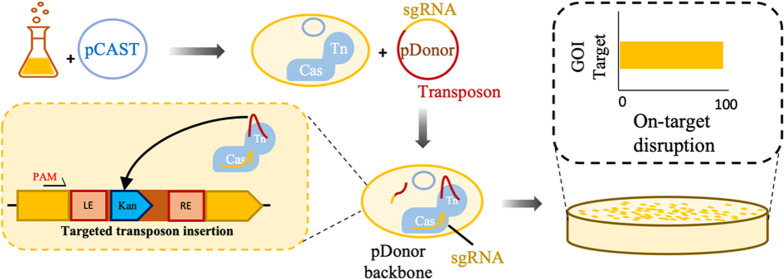

To test the S. hofmannii CAST system, we first transferred the genes from the Strecker et al. pHelper plasmid to a broad-host-range origin of replication.32,58,59 To create the CAST plasmids (pCAST), the Plac promoter, tnsB, tnsC, tniQ, and cas12k genes were cloned into a plasmid with the RK2 origin of replication with the kanamycin or gentamicin resistance markers, creating plasmids pKSh2 and pKSh5 (Supporting Figures S18 and S19), respectively. Neither pKSh plasmid nor the original pHelper possessed lacI, resulting in constitutive expression of the CAST machinery from Plac. Plasmids designed by Strecker et al. encode the sgRNA on the same plasmid as the CAST genes, which prevents iterative use of the system because the plasmid cannot be easily cured after transformation. To enable an iterative mutagenesis system and facilitate easier re-targeting, we moved the gRNA-encoded DNA to the donor plasmid (pDonor) that possessed the transposon and replaced the R6K origin with the pUC origin of replication, which is suicidal outside of the Enterobacteriaceae59 and has a higher copy number. The gene encoding monomeric Red Fluorescent Protein (mRFP) was inserted in the place of the sgRNA target sequence. After around-the-horn cloning to add a DNA target, the mRFP is removed, allowing for easy identification of clones that possess re-targeted plasmids (Supporting Figure S1). We then constructed pDonor variants with the transposon carrying tetracycline, kanamycin, gentamicin, or hygromycin markers. In this design, the bacteria are transformed sequentially with pCAST and the suicidal pDonor (Figure 1A). As the cells recover, the suicide vector pDonor encoded sgRNA is transiently expressed while the CAST complex acquires the transposon before the pDonor is lost through cell division. ShCAST mediates transposition downstream of the PAM site with the transposon left end (LE) closest to the PAM (Figure 1B).32 The dual plasmid design allows for fast re-targeting of the pDonor variants and circumvents the need to cure pCAST from the cell in iterative mutagenesis, as would be required if both sgRNA and CAST were on the same plasmid.

Figure 1.

CAST system schematic. (A) Schematic of the experimental steps for CAST-mediated transposon mutagenesis. The bacteria are first transformed with pCAST, then CAST is induced, and the strain is transformed with the suicide plasmid pDonor, which encodes for the sgRNA and the transposon. (B) The transposon inserts directionally with the left end (LE) integrating nearest the PAM.

System Validation by Targeting eyfp

To enable easier testing of our system, we integrated eyfp into the chromosome using the site-specific mini-Tn7 integration system.60 Targeting of eyfp leads to its disruption and results in a loss of fluorescent signal, providing a simple way of detecting on-target insertion (Figure 2A). This also provided us with a common target site for testing in A. fabrum, B. thailandensis, and P. putida (Supporting Figure S2), representing the Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria, respectively. A. fabrum and P. putida were then transformed with pKSh2 and B. thailandensis with pKSh5. We chose targets with the KGTB PAM (Supporting Text) because of substantial degeneracy in the first and fourth positions according to the PAM wheel.32 The pDonor plasmid with the eyfp-1 sgRNA was transformed into each strain after growth to mid-log phase and spotted onto media with the corresponding antibiotic to select transposon integrants. All three transformations had about 103 CFU (Colony forming unit) μg–1 of DNA transformed, indicating successful transposon integration. Mutants were assessed for loss of fluorescence on a blue light transilluminator (Figure 2A). The PLlacO-1 promoter driving transcription of eyfp functions across many bacterial species, though the expression can be low,49 and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between cells that express eyfp and those that do not. Accordingly, we also screened the colonies with PCR using primers that distinguish the presence or absence of insertion based on product size (Supporting Figure S3A). In B. thailandensis, 12 of 14 colonies screened had the eyfp gene disrupted by the transposon, as confirmed by PCR amplification (Supporting Figure S3B). In contrast, we could not identify any eyfp mutants in either P. putida or A. fabrum, suggesting that the transposon integrated at an off-target location.

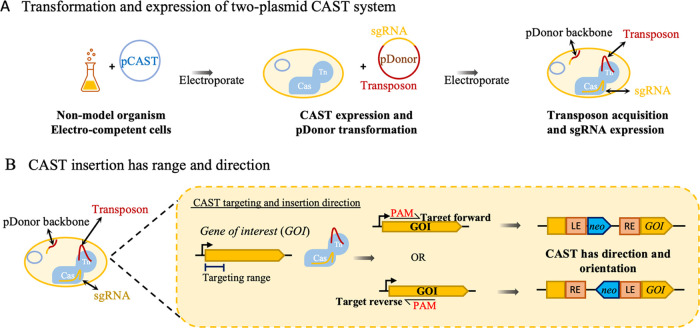

Figure 2.

CAST targeted disruption of eyfp in three Proteobacteria. (A) CAST eyfp targeted integration mutants were selected by the transposon antibiotic resistance marker. The eyfp mutants that lose fluorescence are identified upon exposure to blue light (470 nm). (B) Map of sgRNA targets (arrows), PAM site (diamonds), and insertion direction (arrow point). The sgRNA targeting range is above the gene, and the total gene length is below the gene. (C) Relative frequency of eyfp results in A. fabrum, B. thailandensis, and P. putida. Target name, PAM site, length in bp, the helper plasmid (CAST plasmid), and the transposon resistance marker are given. The loss of fluorescence was calculated with n mutants collected, while genotyping was performed on 24 clones for all targets. The Tn-Seq on-target % was calculated with all reads from each experiment (bin size = 1 Kbp). (D) Density plot of transposon insertions for target eyfp-2 in A. fabrum, B. thailandensis, and P. putida in reads per million (RPM). The x-axis goes from the start of eyfp (0 bp) to 500 bp into the eyfp gene. The vertical dotted red line depicts the start of the PAM site with the arrow pointing to the direction of insertion for target eyfp-2, and the horizontal red dotted line depicts 1 × 104 RPM (bin size = 1 bp).

We hypothesized that the off-target integrations in P. putida and A. fabrum were caused by high expression of the CAST machinery, a phenomenon reported by Strecker et al. in their description of CAST function in E. coli. Accordingly, we modified the CAST plasmid to include an inducible promoter by replacing the Plac promoter with the PLlac promoter and the Lac repressor, creating plasmid pBLlSh261 (Supporting Figure S20). In addition to the original eyfp-1, several other targets within eyfp were tested, (Figure 2B). We also chose to test different length guide-RNA targets, including some with only 17 bp targets, as it has been reported that spacer length can influence the targeting in other CRISPR-Cas systems.62−67

In P. putida, some targets had over 50% efficiency (Figure 2C), while the same targets were inefficient in A. fabrum. For example, in A. fabrum, eyfp-1 and eyfp-2 yielded only 2 and 3% on-target using the pBLlSh2 CAST plasmid, respectively, even though the same sgRNA had over 40% efficiency in B. thailandensis or P. putida, demonstrating that there is a host-specific variable affecting on-target efficiency. We then re-tested the pKSh2 plasmid in A. fabrum by transforming overnight cultures or using a double-setback technique,68 diluting to OD600 of 0.1, 0.3, or 0.5 after reaching exponential phase, repeating the dilution, and then transforming with the donor plasmid during log phase. A. fabrum grown overnight with pKSh2 gave one on-target mutant across three biological replicates, while the second dilution at OD600 0.5 gave the greatest efficiency out of all tested (Supporting Figure S14A), so we continued with this method. After optimization of the pKSh2 CAST in A. fabrum, the targets eyfp-1 and eyfp-2 yielded 9 and 46% on-target insertion rates (Figure 2C), respectively, suggesting that precise conditions for growth could influence the system’s functionality (Supporting Text).

To identify the integration site of the off-targets and to further confirm the on-target observations, we performed Tn-Seq-like mapping of the transposon and genomic DNA junction of the transformation pool. Results revealed that eyfp-2 was successfully targeted in all three bacteria, and eyfp-5 had high on-target insertion frequencies in P. putida and B. thailandensis (Figures 2C,D and S4). Across all three bacteria, off-target insertions were found at low frequencies throughout their genomes (Supporting Figure S4). Target eyfp-2 in P. putida was 17% on-target and the highest integration at a single off-target region was 5% of total reads. For B. thailandensis and A. fabrum, the highest off-target regions for eyfp-2 account for only 0.12 and 0.31%, respectively, suggesting that off-targets do not accumulate at predetermined positions. A comparison of eyfp-2 on-target insertions across all three bacteria shows the maximum integration falls within ∼20 bp of each other and spans ∼300 bp for B. thailandensis and ∼100 bp for the other organisms (Figure 2D). The differences in the insertion span length could be attributed to the difference in overall efficiency among the bacteria.

We also examined changing the antibiotic resistance marker on the pDonor plasmid for P. putida. For the eyfp-1 target, the pDonor carrying the transposon with the tetracycline marker had 2% on-target efficiency while the pDonor carrying the gentamicin marker showed an increased 75% on-target efficiency (Figures 2C and S5). Both markers resulted in similar transformation efficiencies ∼104 CFU μg–1 of DNA transformed (Supporting Table S13), suggesting that selection strength alone was not the reason for the observed discrepancy. The tetracycline marker was efficient in other instances, discussed below with amino acid biosynthesis gene targets.

The most efficient system in each bacterium had an average transformation efficiency of 104 CFU μg–1 DNA, allowing the retrieval of thousands of transposition mutants with just one mL of cell culture (Supporting Table S8). No significant difference was observed in the on-target efficiency of the different length sgRNA that we tested (p-value > 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test; Supporting Table S9). The different targets had varying on-target efficiency in all of the bacteria tested. Overall, our results had an agreement of 94% for the paired phenotypic and genotypic tests confirming or refuting on-target integration. Differences between loss of fluorescence (n = 96) and PCR (n = 24) percentages may be due to the difference in sample size, but these present with a strong positive correlation across the subset of genotyped mutants of all three Proteobacteria (r = 0.9823, p-value = <2 × 10–16; Supporting Table S10). Because each bacterium showed between 40 and 99% efficiency for at least one sgRNA target, we were encouraged to extend this system to different targets. In practical terms, efficiencies of even 40% allow for rapid, facile screening of mutants, as at most screening 10 colonies will enable the identification of a mutant with the correct insertion.

Testing B. thailandensis with Auxotrophic Targets

We next sought to confirm that the CAST system could disrupt native genes in all three bacteria. As pKSh5 in conjunction with the kanamycin-carrying donor plasmid resulted in high efficiency in B. thailandensis, we continued testing with this combination. We targeted genes where disruption would cause amino acid auxotrophy, thus providing two lines of evidence that the integrations were on-target; (1) mutants would be unable to grow on a minimal medium, (2) growth is restored with cognate amino acid supplementation (Figure 3A). To minimize the chance of pleiotropic effects changing cell physiology, we targeted genes that were either on single transcripts or were last in their predicted operon.

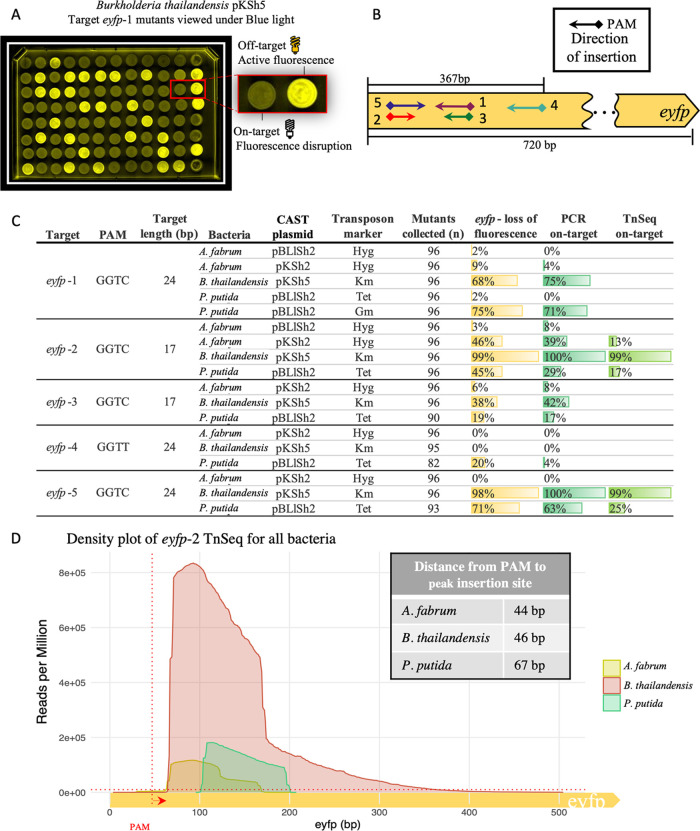

Figure 3.

Auxotrophic screening and target efficiency in B. thailandensis. (A) Auxotrophic CAST mutants with the integrated resistance marker are spotted on LB-agar plate plus antibiotic. Subsequently, mutants are passed to M9 agar with and without the cognate amino acid. Selection plates for B. thailandensistrpA-1 target that results in tryptophan auxotrophy. M9 minimal media plates with 0.2% glucose (Glc) with or without 0.8 mM tryptophan (l-Trp). (B) Map of sgRNA targets (arrows), PAM site (diamonds), and insertion direction (arrow point). (C) Relative frequency table of on-target gene disruption results with auxotrophy complementation (n = mutants collected) and genotype (n = 24).

In B. thailandensis, we targeted argC and trpA to yield arginine and tryptophan auxotrophs, respectively. A total of five trpA and four argC targets located within the first 33% of the coding sequence was tested (Figure 3B). Delivery of the pDonor plasmids resulted in an average transformation efficiency of 8.3 × 103 CFU μg–1 across all targets (Supporting Table S8). The data summarized in Figure 3C shows that six of nine sgRNA’s had very high efficiency with over 90% on-target. Both trpA-1 and trpA-5, which targeted the same region but with a 24- or 16-bp protospacer, yielded very high on-target efficiencies, confirming that protospacers of just 16-bp are functional. The other three trpA sgRNA, each with a 24-bp protospacer and targeting regions slightly up- and downstream had much lower efficiencies.

All four targets in argC yielded very high on-target efficiencies. We observed that the rich medium did not provide sufficient arginine during preliminary experiments, and the auxotrophs grew poorly. Thus, in subsequent experiments, arginine was added to the recovery medium. Target argC-1, which had a TGTC PAM site and 24-bp protospacer, was nearly 100% efficient. The argC-2 target had a GGTC PAM, and a 24-bp protospacer was similarly efficient. We then tested the same PAM as the argC-2 region, but with different length sgRNA, argC-3 (20-bp), and argC-4 (28-bp), and in both cases found nearly 100% on-target efficiency on both tests.

In most cases, the PCR performed on a subset of clones confirmed the observed phenotype with 96% of PCRs in agreement with the auxotrophy assessment and with a positive Pearson correlation of r = 0.9875, p-value = 1.25 × 10–12 (Supporting Table S10). Two factors likely caused the slight differences between phenotype and genotype efficiencies for targets trpA-3-4. First, there was variation in sample size since only a quarter of the mutants screened for auxotrophy were also genotyped. Second, there appeared to be some mutants that were mixed populations that had both auxotrophs and prototrophs. The PCR indicated a mutant genotype with these samples, though the putative mutant also grew on M9.

Testing P. putida with Auxotrophic Targets

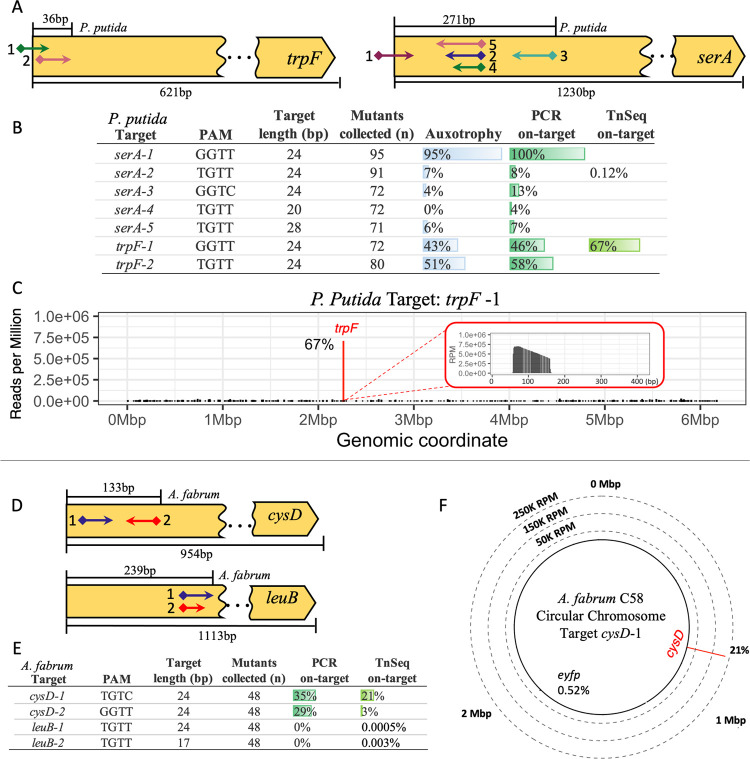

In P. putida, we targeted trpF and serA to make tryptophan and serine auxotrophs, respectively (Figure 4A). Mutants obtained with target serA-1 had high rates of auxotrophy, while targets serA-2 and serA-3 were less than 10% on-target (Figure 4B). The Tn-Seq results also showed low efficiency for serA-2, with on-target reads accounting for only 0.12% of total mapped reads and infrequent transposon insertion around the on-target area (Supporting Figure S6A,B). For serA-2 (24-bp target), we then tested versions of the guide that were 20- and 28-bp in length, with serA-4 and serA-5, respectively. A comparison of the three sgRNA showed virtually no difference in the number of auxotrophic mutants obtained from each (Figure 4B), suggesting that adjusting sgRNA length does not improve on-target efficiency in P. putida.

Figure 4.

Gene disruption in P. putida and A. fabrum. (A) Map of auxotrophic sgRNA targets across P. putida amino acid biosynthesis genes trpF and serA. SgRNA targets (arrows) with the PAM site (diamonds) and insertion direction (arrow point). SgRNA targeting range (above gene) and total gene length (below gene). (B) Relative frequency table of auxotrophy complementation (n = mutants collected), genotype (n = 24), and Tn-Seq results for P. putida targets. (C) Tn-Seq results for P. putida target trpF-1 with on-target reads (red bar) and frequency (%) across the whole genome (bin size = 1 Kbp). Zoomed-in view of transposon insertion of trpF-1 start at target site PAM (0bp) (bin size = 1 bp). (D) Map of sgRNA targets across A. fabrum amino acid biosynthesis genes cysD and leuB. (E) Relative frequency table of genotype (n = 48) and Tn-Seq results for A. fabrum targets. (F) Tn-Seq results for A. fabrum target cysD-1 with on-target reads (red bar) and frequency (%) across the whole genome (bin size = 1 Kbp). Dashed rings represent the Y-axis in reads per million (RPM) with Mbp (Megabase pair) denoting the chromosome coordinates.

In contrast, both trpF targets had a moderate frequency of auxotrophy. The trpF-1 had 43%, and trpF-2 had 51% auxotrophy, consistent with the genotyped on-target frequencies (Figure 4B). The Tn-Seq data for target trpF-1 shows 67% on-target reads with insertions spanning ∼100 bp of the target site (Figure 4C). The Tn-Seq data revealed no prominent off-target locations for target trpF-1; instead, off-targets were spread throughout the genome. For trpF-1 and serA-2, the highest off-target sites found through Tn-Seq account for 1.73 and 3.76% of all insertions. Overall, the phenotype and genotype results for P. putida had good agreement, with 91% of the subset of screened clones having matching phenotype and genotype, with a Pearson correlation of r = 0.9734, p-value = 1.06 × 10–09 (Supporting Table S10).

Targeting Amino Acid Biosynthesis Genes in A. fabrum

In A. fabrum, the cysteine and leucine biosynthesis genes, cysD and leuB (Figure 4D), were selected as possible auxotrophic targets. It was previously reported that cysD disruption results in mucoid colonies but not auxotrophy on agar plates.69 However, this phenotype was challenging to discern, and leuB disruptions were also prototrophic under the conditions tested here. Thus, genotyping by PCR was used to quantify transposons insertions (Figure 4E). The average transformation efficiency for these targets ranged between 103 and 104 CFU μg–1 of DNA transformed (Supporting Table S11).

Genotyping revealed that targets in cysD had transposon insertion frequencies over 25% for both cysD-1 and cysD-2. Tn-Seq data showed a similar result for cysD-1, with an on-target insertion frequency of 21% (Figures 4F and S7). However, cysD-2 had only 3% on-target based on the Tn-Seq data (Figure 4E), though this was still the most abundant integration site (Supporting Figure S8). This slight discrepancy is likely attributed to amplification bias during the Tn-Seq mapping procedure.70 For targets leuB-1 (24-bp) and its shorter version leuB-2 (17-bp), no on-target transposon insertions were found through genotyping by PCR (n = 48), and Tn-Seq found <0.005% integrations in the targeted region of leuB for both targets (Figures 4E and Figure S9B). The A. fabrum Tn-Seq results had similar off-target patterns for all four sgRNA, with integrations mapping across the whole genome, encompassing both the circular and linear chromosomes and the native pAT and pTi plasmids. The most prominent location for off-target integration for all four sgRNA was the eyfp integration region, though only <1% of reads were mapped to that location for all targets (Figures 4F and 7–9A).

The relatively high level of on-target integrations observed for cysD is promising, though improvements are needed to enable a consistently efficient system. Perhaps further optimization of the promoter driving the CAST expression or growth conditions would further improve efficiency. Alternatively, further experimentation could identify properties of targets or PAMs most likely to function with high efficiency using the plasmids developed here.

Multiplex Targeting in B. thailandensis

Given the high efficiency of on-target insertion in B. thailandensis, we investigated whether simultaneous transposon insertion at two different target sites was possible (Figure 5A). The ability to introduce two insertions simultaneously will streamline strain engineering applications and profoundly increase the ease of strain construction. Plasmids targeting eyfp-2 and trpA-1 (with kanamycin and tetracycline resistance markers, respectively) were co-transformed into cells that possessed the pKSh5 plasmid. Colonies appeared two days after plating on LB with selection for both resistance markers, with a transformation efficiency of 1.2 × 105 CFU μg–1 DNA transformed (Supporting Table S12). Auxotrophy was tested through spotting in minimal media, and remarkably, most colonies had both mutations (Figure 5B). Transposon sequencing of the transformed pool confirms this trend (Figure 5C), where 43 and 56% of the reads map to eyfp and trpA, respectively, accounting for 99% of reads in the dataset. While these reads should theoretically be split 50:50 between the two targets, we attribute the slight unevenness of the on-target numbers to bias in the Tn-Seq amplification step.

Figure 5.

Multiplex Tn integrations in B. thailandensis and temperature-sensitive pCAST. (A) Multiplexing schematic, both pDonor are simultaneously transformed into the cell. (B) Relative frequency table of multiplex targeting with auxotrophy/fluorescence disruption and genotyping results for B. thailandensis in co-transformed targets trpA-1 and eyfp-2. (C) Tn-Seq results for eyfp-2 (yellow) in chromosome I and trpA-1 (red) in chromosome II. Read frequency presented as a percentage across both chromosomes (bin size = 1 Kbp). Zoomed-in view of transposon insertion of both gene targets start at the PAM site (0 bp) (bin size = 1 bp). (D) Map of sgRNA targets in B. thailandensis genes motA and class A β-lactamase (β-lac) encoding BTH_RS07435. (E) Relative frequency table for B. thailandensis pRO16Sh5 temperature-sensitive pCAST with phenotype (n = mutants collected) and genotype (n = 24) results. Phenotype results reflect disruption of tryptophan production (trpA-1), motility (motA-1), or carbenicillin 100 μg/mL resistance (class A β-lactamase). (F) Relative frequency table for P. putida pRO16Sh2 temperature-sensitive pCAST with auxotrophy (n = mutants collected) and genotype (n = 24) results. (G) Motility assay for pRO16Sh5 B. thailandensismotA-1 in semisolid LB 0.3% agar, successful gene disruption results in loss of motility halo. (H) Schematic for iterative transformations. The pDonors are transformed consecutively into the cell, selecting for the transposon and pCAST in between transformations. (I) Recovery plate of serA-1 transformations for P. putida with a violacein transposon integration. (J) Relative frequency table for iterative transformation for all three bacteria with genotype results. The initial target, with the corresponding antibiotic marker in parenthesis, is given followed by the second mutation.

Assessment of Whole Plasmid Integration

The ShCAST sometimes resulted in co-integration, where the entire donor plasmid is integrated into the target site because the system lacks an equivalent of the endonuclease tnsA.(26,71,72) To determine the frequency of co-integrate formation, we performed PCR with primers that amplify the plasmid backbone outside of the transposon (Supporting Figure S10A). Consistent with the observation in E. coli, the plasmid was sometimes integrated into the chromosome in all three strains. In B. thailandensis and P. putida, 43 and 32% of the integrations possessed the whole plasmid, respectively. In comparison, A. fabrum had the most plasmid integrations, with an average of 81% (Supporting Table S14 and Figure S10B). There was no correlation between target efficiency and co-integrate formation when looking at phenotype data (Pearson correlation of r = −0.15, p-value = 0.3298) or genotype data (Pearson correlation of r = −0.211, p-value = 0.1787) across all three bacteria.

Although integration of the whole plasmid is not desired, disruption of the targeted genes occurs, nonetheless. Thus, this phenomenon does not detract from the usefulness of this targeted mutagenesis system. Since the antibiotic marker is flanked with FRT recognition sites, we suspected that the flippase (Flp) recombinase would remove the plasmid backbone and marker simultaneously, resulting in the desired genotype. We first confirmed that Flp recombinase worked as expected for the excision of the selection marker from a transposon integration in B. thailandensis without the plasmid backbone (Supporting Figure S11). We next tested whether Flp recombinase could remove both integrated markers and the plasmid integration. PCR amplification of a co-integrate confirmed that about two-thirds of colonies were kanamycin-sensitive and had lost the plasmid backbone (Supporting Figure S10C,D). Colonies that retained resistance after induction of Flp were found to still have one of the kanamycin marker copies (while the other had been excised); other times, the pUC backbone was also found through PCR, possibly from inefficient excisions (Supporting Figure S10E). Our results indicate that successful marker excision could remove the pDonor backbone in cases of complete plasmid integration with high efficiency.

CAST Insertion of an 11 kbp Operon

In E. coli, transposon payloads of 10 kbp are efficiently integrated into the genome.36 To assess whether these large insertions were also possible in the bacteria of this study, we tested a transposon that totaled 11.1 kbp containing a gentamicin resistance gene and the violacein biosynthesis pathway composed of vioABCDE (Supporting Figure S12A), which produces a purple pigment in cells. This transposon was delivered from a pDonor containing a sgRNA targeting eyfp-1, with the complete vector totaling 13.9 kbp. We successfully transformed and recovered violacein transposon mutants in all three bacteria, across three biological replicates with a mean transformation efficiency of 7.7 × 103 for P. putida (Supporting Table S13), 2 × 101 for B. thailandensis (Supporting Table S12), and 6.3 CFU μg–1 DNA transformed for A. fabrum (Supporting Table S11). All P. putida mutants presented with violet color at the time of recovery (Supporting Figure S12B), with 91.5% of all mutants collected (n = 47) found to be on-target when genotyped (Supporting Figure S12C). For B. thailandensis (n = 10) and A. fabrum (n = 5), none of the mutants presented with violet color, but genotyping revealed 80% on-target transposition in B. thailandensis and none in A. fabrum (Supporting Figure S12D,E). Genotyping for the vioABCDE operon revealed that all B. thailandensis and A. fabrum mutants possessed the violacein operon. The mutants for B. thailandensis and A. fabrum were grown under selective pressure for the transposon and an inducer for expression of violacein, but these failed to turn purple after 4 days of growth, suggesting the operon is inoperative in these bacteria.

Temperature-Sensitive pCAST

Our goal was to improve the mutant construction process and allow easy curing of the CAST plasmid with a temperature-sensitive origin of replication (Ts). Accordingly, we moved the pCAST to the pRO1600 Ts origin previously used in B. thailandensis.(52) The resulting plasmids, pRO16Sh5 (gentamicin) and pRO16Sh2 (kanamycin) were transformed into B. thailandensis and P. putida, respectively. For the non-Ts plasmids in these two organisms, curing pCAST took three days in B. thailandensis and P. putida and resulted in ∼70% of the population losing the plasmid (Supporting Figure S13A,C). In A. fabrum, increasing the incubation to two overnights resulted in a significant increase in pCAST loss from <10 to ∼75% of the population (Supporting Figure S13D). With pRO16Sh5, 4 h of growth at a high temperature (42 °C for Bt and 37 °C for Pp) resulted in over 85% plasmid loss in both bacteria (Supporting Figure S13B,E), thereby decreasing the time needed for curing from three days to one day. The genome integration efficiency using pRO16Sh5 was assessed in B. thailandensis using the target trpA-1 and two new physiologically relevant targets for motility (motA-1) and β-lactam resistance (β-lac-1) (Figure 5D). Disruption of motA-1 causes loss of the motility halo in a semisolid medium (Figure 5G) while target β-lac-1, which encodes for a class A β-lactamase, renders carbenicillin sensitivity. The trpA-1 target had similar results with the pKSh5 and pRO16Sh5 plasmids, with an on-target efficiency of ∼100% (Figure 5E). The pRO16Sh5 system also had high efficiency for targets motA-1 and β-lac-1, with over 60% on-target efficiency in both (Figure 5E). In P. putida, the on-target efficiency with pRO16Sh2 was also high (Figure 5F). In comparison to the pBLlSh2 plasmid using a tetracycline marker, an improvement from ∼45 to ∼75% efficiency with trpF-1 was observed. We then tested the serA-1 and serA-2 targets with the gentamicin-marked transposon. Both targets had efficiencies near 100% with the pRO16Sh2 plasmid, a dramatic increase from the <10% efficiency for target serA-2 with a tetracycline marker in the pBLlSh2 system. Though we mostly attribute this increase to the gentamicin marker since a similar increase in efficiency was observed relative to the tetracycline marker for target eyfp-1. Our results demonstrate that the pRO16Sh plasmid allows for a simplified mutagenesis protocol with on-target efficiency meeting or exceeding the pBLlSh2 plasmid.

Iterative CAST Mutagenesis

Iterative transposon mutagenesis is achievable by simply transforming a pDonor plasmid with a new target and compatible selection marker (Figure 5H). To demonstrate, we performed an iterative experiment in all three bacteria. In P. putida an eyfp-1 violacein (Gm) mutant that was cured of the pHelper was re-transformed with pRO16Sh2 and subsequently transformed with the target serA-1 (Tet). This resulted in a transformation efficiency of 6.4 × 103 CFU μg–1 DNA transformed, and 95% on-target insertion verified through genotype (Figure 5I,J). A subsample of these mutants showed all still contained the violacein integration. After one week it was noted all serA-1 transformants had turned purple (Figure 5I). In A. fabrum on-target cysD-1 (Hyg) mutants were grown in kanamycin selecting for pKSH2 and subsequently transformed with eyfp-1 (Cm) and yielded 4.8 × 103 CFU μg–1 DNA transformed. The eyfp-1 on-target integration was found in 33% of the samples screened (Figure 5J). In B. thailandensis, a β-lac-1 (Kan) on-target mutants were grown in gentamicin selecting for pRO16Sh5 and transformed with trpA-1 tetracycline for 7.3 × 103 CFU μg–1 DNA transformed with 96% on-target efficiency (Figure 5J).

Discussion

Random transposon mutagenesis has allowed the study of gene disruptions that cause loss of function in bacterial cells.22,73 The randomness of integration has served as a valuable tool to rapidly create whole-genome deletion libraries that can be screened for loss of function or population-level dropout analysis.74−76 Until recently, this technology was limited by the inability to target-specific locations, making retrieval of specific mutants a lengthy and challenging process as transposon libraries had to be created and mapped to find desired mutants. CAST technology combines the efficiency of transposon mutagenesis with the site-specific targeting of CRISPR. Our approach uses CAST from S. hofmannii for an iterative and easily re-programmable transposon mutagenesis system. Re-targeting the pDonor sgRNA through around-the-horn cloning77 is an easy and efficient two-step process of amplification and ligation that can be parallelized for high-throughput plasmid construction. The Ts CAST plasmids in B. thailandensis and P. putida maintain high efficiency and streamline the plasmid curing process. Furthermore, multiplex and iterative transformations allow multiple modifications in the cell in a short amount of time. Applications for this work include the possibility to construct precise transposon mutant libraries as has been recently shown in other bacteria with Cas12k.35 Although this work focused on only three members of the Proteobacteria, we expect that the system and plasmids will be useful in diverse bacteria, broadening the molecular tools for genomic editing.

Overall, our approach allowed targeted transposon mutants in a short time, with initial setup and one round of integration taking as little as three days. While the on-target efficiencies we observed varied widely, the ease with which target plasmids can be constructed, the efficiency of transformation, and the large payload size make this technique potentially transformative. Overall, over 4000 mutants were collected and analyzed for the correct on-target disruption phenotype. Approximately one-quarter of all collected mutants were further analyzed through PCR, linking phenotype with genotype. We found multiple targets with ∼100% on-targeting efficiency in B. thailandensis and P. putida and a maximum efficiency of 45% for A. fabrum. Discrepancies between genotype and Tn-Seq results could be attributed to differences in sample sizes (24 colonies vs the whole mutant population) or these could be due to variations between biological replicates. The results shown in this work were particularly positive in B. thailandensis, an important pathogen model, which showed the highest on-target efficiency and overall performance, expanding its molecular toolbox. The overall efficiencies shown in this work allow quick identification of mutants because even 10% efficiency requires very few colonies to be screened to identify one with the desired mutation. These efficiencies are similar to previously reported shCAST efficiencies, as in Vo et al. where efficiencies of 45% with similar spreads of off-target patterns are described for ShCAST.36 Large transposon insertions were also achieved in all bacteria, through the integration of an 11.1 Kbp transposon carrying the violacein biosynthetic pathway. We also obtained multiplex transposition into two separate target sites with different resistance genes, demonstrating the capacity to achieve multiple targeted genomic modifications in tandem in a cell, considerably reducing the time needed to create polygenic mutants. Finally, curing the CAST plasmid for a finished mutant in all three bacteria can be achieved in as little as one day with the use of the Ts pRO16Sh5 in B. thailandensis and P. putida curing ∼100% of the population, or in three to four days with the other CAST plasmids resulting in ∼70% efficiency of plasmid loss.

The CAST system has several advantages compared to other methods for genome editing in bacteria. Compared to traditional homologous recombination (HR) from suicide vectors, the CAST protocol is faster and less laborious because custom vectors with long regions of homology do not need to be constructed (Supporting Figure S16). Instead, only 16–24 bp of the sgRNA on pDonor is changed, a modification that is both easy to perform and scalable for high-throughput mutagenesis. Additionally, the transformation efficiency allows the scale to be decreased by an order of magnitude compared to other engineering methods. HR protocols often require 20–50 mL of culture concentrated 200× for transformation or large concentration DNA (>500 ng) to achieve high efficiencies.78−80 We used less than 1 mL of cell culture for the three bacteria tested here and with as little as 50 ng of DNA to obtain up to 106 CFUs. These decreased volumes and concentrations allow for simpler workflows and easy scaling to test many sgRNA or target many genes.

Methods for recombineering with phage-derived proteins have been described in all three bacteria tested here, although in A. fabrum(81) these methods have not been widely adopted. The system described in B. thailandensis(82) still requires a complicated cloning step to integrate regions of homology and multiple rounds of selection/counterselection. In P. putida, several recombineering techniques have been described,79,80 some of which use CRISPR/Cas to counter-select17 against unedited cells or stimulate recombination.46,83 These techniques are highly useful, and some enable scar-free mutagenesis. However, each method has its downsides, including low editing efficiency, the limited size of integrations, and complicated cloning schemes. While the CAST also has limitations, the large cargo size and relative simplicity in targeting are inherent advantages. In contrast to other CRISPR-enabled methods that require the design and construction of both the guide-RNA and the cognate repair template, the CAST system requires customization of only the guide-RNA. Overall, compared to HR and recombineering, while CAST does not currently support scarless mutations, it simplifies and accelerates multiplex genomic modifications while maintaining site-directed mutagenesis.

In comparison to other CAST systems (Supporting Figure S17), the type I-F V. cholerae (Tn6677), INTEGRATE (VchINT)36 system was recently demonstrated to function from a broad-host-range vector and was highly efficient in K. oxytoca and P. putida. This system used a replicative plasmid encoding the CAST, sgRNA, and the transposon (pSPIN) or a two-plasmid system with the transposon encoded in a second plasmid. In P. putida the pSPIN system was robust and showed high on-target efficiency ranging from 76.9 to 99.8%, like some of the efficiencies reported in this work. Recently, a second INTEGRATE-based system was published on A. fabrum(41) which uses a single replicative plasmid carrying INTEGRATE, the sgRNA, and transposon. This system used a pBBR1 backbone which presented with similar on-target efficiencies as those reported here for A. fabrum, with a range of 3.5–22.2%. Interestingly, the use of a different backbone, pVS1, showed increased efficiency reaching up to 75% on-target in A. fabrum.(41) This presents a new avenue to explore to achieve higher efficiency in A. fabrum. Because some of the described INTEGRATE plasmids are replicative, it is unclear if they can be easily cured in the cells which have integrated the transposon, with the notable exception of the temperature-sensitive pSPIN plasmid. Without curing this plasmid, only one round of mutagenesis can occur. In contrast, our dual plasmid system has a replicative plasmid carrying the CAST machinery, while the sgRNA and transposon are encoded on a suicide vector. While we cannot rule out the possibility of multiple insertions per mutant, the dual plasmid design prevents replication and subsequent re-targeting, and we have not found any evidence of this occurrence. This design strategy makes our system inherently iterative because nonintegrated donor DNA cannot be maintained, enabling faster subsequent mutagenesis with a compatible antibiotic marker and different sgRNA targets. Consistent with previous observations, we also found that the S. hofmannii CAST inserts transposons directionally with the left arm adjacent to the target PAM. On the other hand, the V. cholerae-derived system inserts the transposon in both orientations, making confirmation of on-target insertion more difficult. Our system achieved ∼100% efficiency in P. putida and B. thailandensis, comparable to the high efficiencies reported for INTEGRATE. However, different targets were tested in INTEGRATE and the present study, so we cannot make direct sgRNA and target site comparisons to the data reported here.

The CAST plasmids described here, available with several antibiotic resistance markers, can potentially be used directly in other members of Proteobacteria. The use of a common target with varying efficiencies across all three bacteria, eyfp, suggests some host-specific factors contribute to varying on-target efficiency. Although the efficiencies reported in this work have a wide range, these are still suitable for fast easy mutant screening. As we observed, initial optimization of growth and multiple target selections may be necessary to find conditions suitable for high on-target transposition in other organisms. To this end, our recently described plasmid toolbox49 can be used to identify regulated promoters that function in Proteobacteria to match the level of expression required for high on-target efficiency. Further research and more comprehensive studies on the target efficiency across the genome could improve the ability to predict which target sites will function with higher efficiency and how the transposon cargo genes might impact overall system efficacy. In sum, the CAST system described here is a fast, easy, and efficient solution to creating gene disruptions and insertions with a wide range of applications suitable for deployment across diverse bacterial species. While initial work is needed to set up the system, the potential to modify nonmodel organisms and reuse the method for eventual genomic modifications makes this a valuable addition to the genetic engineering toolbox.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Media, and Growth Conditions

All media and growth conditions for E. coli, A. fabrum, B. thailandensis, and P. putida are provided in SI Materials and Methods. The complete lists of strains, plasmids, and primers are provided in Tables S1–S4.

Plasmid Cloning

A full list of plasmids and Addgene identifiers is presented in Table S2. All primers are listed in Tables S3 and S4. Primer pairs for pCAST and pDonor cloning PCRs are listed in Supporting Table S6. Q5 2X MM (NEB) was used following the manufacturer’s protocol. All PCRs were DpnI digested for 30 min at 37 °C and purified with a PCR clean-up kit prior to assembly with NEBuilder-HiFi assembly mix, except for pRO16Sh5 which was blunt ligated using T7 ligase (NEB). The assemblies were transformed into chemically competent E. coli NEB 5-α (NEB) and plated onto the medium with the cognate antibiotic. pCAST plasmid cloning: ShCAST genes were PCR amplified from pHelper_ShCAST_sgRNA. The vector backbones were amplified from plasmids carrying an RK2 origin of replication with a Kanamycin resistance gene for pKSh2 or Gentamicin for pKSh5, and a pBBR1 oriV for the pBLlSh2 backbone. The pRO1600 Ts origin was amplified from pFlpe2.52 pDonor plasmid construction: The sgRNA was amplified from pHelper_ShCAST_sgRNA, and the transposon was amplified from pDonor_ShCAST_kanR. The two linear fragments were phosphorylated with T4 Polynucleotide Kinase and ligated with T4 DNA ligase, following the manufacturer’s protocols. Violacein pDonor (pUCSh5vio-2300) cloning: The plasmid backbone was amplified from pUCSh5-2300 (this study), and the violacein insert, the PCin promoter, and cinR repressor were amplified from pBLlVio5. pDonor re-targeting: The pDonor sgRNA was re-targeted using around-the-horn cloning by amplifying the template with mRFP in place of the target sequence. The phosphorylated primer 2505 was paired with primers that possess overhangs containing the target sequence (Supporting Table S4). The reaction was DpnI digested, purified with a silica column kit, ligated using T4 DNA ligase at room temperature (RT) overnight, and transformed into chemically competent E. coli cells. Colonies were screened the following day for the absence of red color, indicating loss of mRFP, and the sequence was verified.

Creation of Reporter Strains with a Yellow Fluorescent Protein

The enhanced yellow fluorescence protein (eyfp) reporter strains of Bt, Pp, and Af were constructed with the mini-Tn7 system according to Choi et al.52 The eyfp integration in Bt was confirmed to be in chromosome 1 by PCR as described by Choi et al. (Supporting Figure S2).

CAST Experiments

B. thailandensis. One colony of Bt with pKSh5 or pRO16Sh5 was grown overnight at 30 °C 200 rpm in 5 mL of LB Gm. The following day 4.5 mL of culture was spun down at 3000g for 3 min. The pellet was washed 2× with 300 mM sucrose at RT and resuspended in 300 μL of the sucrose solution. 50 μL of Bt resuspension was electroporated in a 0.1 cm cuvette at RT with 0.5 μL of pDonor plasmid (average ∼200 ng) at 2.2 kV using a MicroPulser (Bio-Rad). The cells were recovered in 1 mL of SOB at 37 °C for 2 h, and 1:10 dilutions were plated on LB Km and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h until colonies appeared. P. putida. One small colony of Pp with pBLlSh2 was grown overnight at 30 °C 200 rpm in 5 mL of LB Km, and the following day diluted to OD600 0.1 in fresh LB Km and grown at 30 °C, 200 rpm. Upon reaching mid-log phase (OD600 0.4–0.5), the culture was induced with 1 mM IPTG and grown for an additional 1 h. The cells were then made electrocompetent with a 300 mM sucrose RT 2× wash and electroporated in a 0.1 cm cuvette at 1.8 kV, recovered in 1 mL of SOB at 30 °C for 2 h, and plated on LB Tet or Gm and incubated overnight at 30 °C until colonies appeared. For pRO16Sh2, a culture was struck out in LB-agar Km and grown overnight at 30 °C, the next day three colonies were passed into 5 mL of LB Km 30 °C 200 rpm and grown until mid-log phase. At this time the cells were made electrocompetent and the protocol follows as previously described. A. fabrum. One colony of Af with pKSh2 was grown overnight in LB Km at 30 °C, 200 rpm. The overnight culture was diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 in 5 mL of LB Km and then diluted again at the mid-exponential phase. 1 mL of cells was then washed twice in 300 mM sucrose and then electroporated with pDonor at RT in a 0.1 cm cuvette with a 2.2 kV pulse. The cells were recovered in 1 mL of SOB at 30 °C for 4 h, and 1:10 dilutions were plated on LB Hyg and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h. For all three bacteria, CFU counts were from an average of 32 colonies from each of three biological replicates that were picked into media plus antibiotic for the selection of the transposon insertion mutants.

Phenotypic Screens

Colonies obtained after transformation with pDonor were resuspended in sterile water and immediately spotted onto LB-agar with the appropriate antibiotic. The spots were resuspended in sterile water for loss of fluorescence screens, re-spotted onto an LB-agar plate, and incubated overnight at 30 °C. Plates were removed from the incubator and left at RT for one week to allow continued expression of eyfp for better visualization. The plates were viewed through a blue light transilluminator (470 nm) and assessed for fluorescence. Loss of fluorescence on-target % was calculated as totalnon-fluorescent mutants/totalmutants. For auxotrophy screens, each spot was resuspended in sterile water, and 5–10 μL was immediately spotted onto M9 agar with appropriate antibiotics with and without amino acid supplementation. The auxotrophy phenotype on-target % was calculated as totalauxotrophic/totalmutants, totalauxotrophic = #MutantsM9+AA – #MutantsM9.

Genotyping Transposon Insertion Mutants

Supporting Table S7 has primer pairs for the genotyping PCRs. An average of eight colonies per biological replicate and 24 total colonies per target were screened by colony PCR. KAPA2G Robust PCR Kit was used to make the PCR master mix using Buffer B with enhancer. Individual mutants were passed to a 96-well plate with 50 μL of water, and 1 μL of the cell suspension was passed to a PCR tube with the PCR mix. Reactions were separated on a 2% (w/v) agarose gel and imaged.

Tn-Seq Library Preparation

Transposon insertion sites were mapped with Tn-Seq in independent integration experiments where the pDonor plasmid was transformed as described above, and the entire transformation was plated after two hours of recovery. The following day, all colonies in the plate were scraped into a 1.5 mL tube, washed, and resuspended with 250 μL of phosphate-buffered saline. Genomic DNA was then extracted using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) followed by ethanol precipitation.53 Extracted gDNA was prepared for sequencing using a modified protocol54 for the NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB) at 1/2 of the recommended reaction volume. After adaptor ligation, transposon-containing fragments were enriched by nested PCR amplification using primers 2625 and 2731 for 15 cycles, followed by primers 2761 and 2731 for 7 cycles. Samples were then PCR amplified for 7 cycles with Illumina adapters that possessed unique dual indexes using the NGS UDI Primer Set 48 (Eurofins Genomics). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 (2 × 150 bp paired-end reads, Novogene Co. Sacramento, CA). Bioinformatic analysis of on/off-targeting was performed by aligning trimmed and quality filtered reads to reference genomes using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner v0.7.17.55 Details on sequencing analysis and the bioinformatic pipeline are given in SI Materials and Methods.

Statistics

The efficiency, mean, and standard deviations were calculated using R56 v3.6.1, RStudio v1.2.1335, and table 157 package. Comparisons of phenotype and genotype efficiency were made using Pearson correlation. Global statistical analysis between sgRNA length and efficiency was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Statistical analysis of efficiency between paired groups of targets with different sgRNA lengths in Bt and Pp was done using the Mann–Whitney U test. At least three independent experiments were used for all tests, a p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

L.T.R. was partially supported by the Florida education fund McKnight doctoral fellowship. The authors thank L. Schuster and C. Mosby-Haundrup for their helpful conversations and comments on the manuscript. They also thank C. Mejia and C. Espinoza for their technical assistance.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data for each mutant is in the supporting dataset spreadsheet. Plasmid sequences, transformation efficiencies, transposon sequencing statistics, location of genomic targets, insertion distances, and main off-target regions are also in the supplementary dataset. Transposon sequencing data is available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) sequence read archive (SRA; BioProject accession: PRJNA756570). R script for data analysis can be found at GitHub (https://github.com/lidi-marie/ReischLab-CAST).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssynbio.3c00065.

sgRNA target selection; A. fabrum targeting efficiency (Supporting Text); bacterial strains, plasmid maintenance, media, and growth conditions (Supporting Materials and Methods); Flp-mediated marker excision; curing CAST plasmids; A. fabrum pCAST efficiency; Tn-Seq bioinformatic pipeline; bacterial strains used in the study; plasmids used in the study (supporting tables); oligoes used in the study; pDonor re-targeting oligoes; sgRNA target sequences; PCRs used in cloning; PCR for genotyping integrations; transformation efficiencies by CAST plasmid; global statistics for genotype efficiency; Pearson correlation between phenotype and genotype; transformation efficiencies by target in A. fabrum, B. thailandensis, and P. putida; co-integrate results; supporting figures; insertion of eyfp cassette across targeted Proteobacteria through a mini-Tn7 system; yellow fluorescence CAST targeting and insertion genotyping; Tn-Seq data for eyfp targets eyfp-2 and eyfp-5 across Proteobacteria; P. putida CAST target eyfp-1 genotyping; P. putida Tn-Seq results for targets serA-2 and trpF-1; A. fabrum amino acid biosynthesis gene target results; A. fabrum Tn-Seq results for target cysD-2; A. fabrum Tn-Seq results for targets leuB-1 and leuB-2; co-integrate insertion and Flp-mediated excision; Flp-mediated antibiotic marker excision Sanger sequencing; violacein pathway transposon insertion; curability of helper plasmid (pCAST); A. fabrum pCAST efficiency; source data for electrophoresis gels and growth patches in supplementary file; timeline of CAST protocol; and system comparisons (PDF)

Legends datasets (XLSX)

Author Contributions

C.R.R. conceived the study and performed the initial plasmid cloning. L.T.R. performed the transposition experiments, phenotype and genotype assays, and data analysis. A.J.E. prepared the next-generation sequencing library, and L.T.R. graphed and analyzed the data. C.R.R., M.G.C., and L.T.R. drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

This work was supported by the University of Florida Opportunity Fund and the Department of Microbiology and Cell Science.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ingram L. O.; Conway T.; Clark D. P.; Sewell G. W.; Preston J. F. Genetic Engineering of Ethanol Production in Escherichia Coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 2420–2425. 10.1128/AEM.53.10.2420-2425.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riglar D. T.; Silver P. A. Engineering Bacteria for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 214–225. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J.; Shao Z.; Zhao H. Engineering Microbial Factories for Synthesis of Value-Added Products. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 873. 10.1007/S10295-011-0970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens L. B.; Tang Y.; Chooi Y. H. Metabolic Engineering for the Production of Natural Products. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2011, 2, 211–236. 10.1146/ANNUREV-CHEMBIOENG-061010-114209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta K.; Beall D. S.; Mejia J. P.; Shanmugam K. T.; Ingram L. O. Genetic Improvement of Escherichia Coli for Ethanol Production: Chromosomal Integration of Zymomonas Mobilis Genes Encoding Pyruvate Decarboxylase and Alcohol Dehydrogenase II. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 893–900. 10.1128/AEM.57.4.893-900.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkhada D.; Kim E.; Lee H. C.; Sohng J. K. Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia Coli for the Biological Synthesis of 7-O-Xylosyl Naringenin. Mol. Cells 2009, 28, 397–401. 10.1007/S10059-009-0135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su B.; Song D.; Zhu H. Homology-Dependent Recombination of Large Synthetic Pathways into E. Coli Genome via λ-Red and CRISPR/Cas9 Dependent Selection Methodology. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 108 10.1186/s12934-020-01360-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M.; Koizumi S. Microbial Production of N-Acetylneuraminic Acid by Genetically Engineered Escherichia Coli. Carbohydr. Res. 2010, 345, 2605–2609. 10.1016/J.CARRES.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvkun G. B.; Ausubel F. M. A General Method for Site-Directed Mutagenesis in Prokaryotes. Nature 1981, 289, 85–88. 10.1038/289085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasin M.; Schimmel P. Deletion of an Essential Gene in Escherichia Coli by Site-Specific Recombination with Linear DNA Fragments. J. Bacteriol. 1984, 159, 783–786. 10.1128/jb.159.2.783-786.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winans S. C.; Elledge S. J.; Krueger J. H.; Walker G. C. Site-Directed Insertion and Deletion Mutagenesis with Cloned Fragments in Escherichia Coli. J. Bacteriol. 1985, 161, 1219–1221. 10.1128/jb.161.3.1219-1221.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Buchholz F.; Muyrers J. P. P.; Francis Stewart A. A New Logic for DNA Engineering Using Recombination in Escherichia Coli. Nat. Genet. 1998, 123–128. 10.1038/2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Zhang Y.; Zhang Y.; Pi Y.; Gu T.; Song L.; Wang Y.; Ji Q.. CRISPR/Cas9-Based Genome Editing in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Cytidine Deaminase-Mediated Base Editing in Pseudomonas Species IScience 2018, pp 222–231 10.1016/j.isci.2018.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reisch C. R.; Prather K. L. J. The No-SCAR (Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering) System for Genome Editing in Escherichia Coli. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15096 10.1038/srep15096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K. C. Use of Bacteriophage Lambda Recombination Functions to Promote Gene Replacement in Escherichia Coli. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 2063–2071. 10.1128/JB.180.8.2063-2071.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.; Bikard D.; Cox D.; Zhang F.; Marraffini L. A. RNA-Guided Editing of Bacterial Genomes Using CRISPR-Cas Systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 233–239. 10.1038/nbt.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio T.; de Lorenzo V.; Martínez-García E. CRISPR/Cas9-Based Counterselection Boosts Recombineering Efficiency in Pseudomonas Putida. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, 1700161 10.1002/biot.201700161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerley B. J.; Rubin E. J.; Camilli A.; Lampe D. J.; Robertson H. M.; Mekalanos J. J. Systematic Identification of Essential Genes by in Vitro Mariner Mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 8927–8932. 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich K. A.; Chovan L.; Hessler P. Genome Scanning in Haemophilus Influenzae for Identification of Essential Genes. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 4961–4968. 10.1128/jb.181.16.4961-4968.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison C. A.; Peterson S. N.; Gill S. R.; Cline R. T.; White O.; Fraser C. M.; Smith H. O.; Venter J. C. Global Transposon Mutagenesis and a Minimal Mycoplasma Genome. Science 1999, 286, 2165–2169. 10.1126/science.286.5447.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Opijnen T.; Camilli A. Transposon Insertion Sequencing: A New Tool for Systems-Level Analysis of Microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 435–442. 10.1038/nrmicro3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Opijnen T.; Bodi K. L.; Camilli A. Tn-Seq: High-Throughput Parallel Sequencing for Fitness and Genetic Interaction Studies in Microorganisms. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 767–772. 10.1038/nmeth.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Des Etages S. A.; Coelho P. S. R.; Roeder G. S.; Snyder M. High-Throughput Methods for the Large-Scale Analysis of Gene Function by Transposon Tagging. Methods Enzymol. 2000, 328, 550–574. 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)28418-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson N.; Mekalanos J. J. Transposon-Based Approaches to Identify Essential Bacterial Genes. Trends Microbiol. 2000, 521–526. 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01865-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell C. S.; Craig N. L. Tn7 Transposition: Two Transposition Pathways Directed by Five Tn7-Encoded Genes. Genes Dev. 1988, 2, 137–149. 10.1101/GAD.2.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnovsky R. J.; May E. W.; Craig N. L. The Tn7 Transposase Is a Heteromeric Complex in Which DNA Breakage and Joining Activities Are Distributed between Different Gene Products. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 6348–6361. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell C. S.; Craig N. L. Tn7 Transposition: Recognition of the AttTn7 Target Sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989, 86, 3958–3962. 10.1073/pnas.86.11.3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra R.; McKenzie G. J.; Yi L.; Lee C. A.; Craig N. L. Characterization of the TnsD-AttTn7 Complex That Promotes Site-Specific Insertion of Tn7. Mobile DNA 2010, 1, 18. 10.1186/1759-8753-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig N. L. Tn7: A Target Site-Specific Transposon. Mol. Microbiol. 1991, 5, 2569–2573. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. E.; Makarova K. S.; Shmakov S.; Koonin E. V. Recruitment of CRISPR-Cas Systems by Tn7-like Transposons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, E7358–E7366. 10.1073/pnas.1709035114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure G.; Shmakov S. A.; Yan W. X.; Cheng D. R.; Scott D. A.; Peters J. E.; Makarova K. S.; Koonin Ev. CRISPR–Cas in Mobile Genetic Elements: Counter-Defence and Beyond. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 513–525. 10.1038/s41579-019-0204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecker J.; Ladha A.; Gardner Z.; Schmid-Burgk J. L.; Makarova K. S.; Koonin Ev.; Zhang F. RNA-Guided DNA Insertion with CRISPR-Associated Transposases. Science 2019, 365, 48–53. 10.1126/science.aax9181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klompe S. E.; Vo P. L. H.; Halpin-Healy T. S.; Sternberg S. H. Transposon-Encoded CRISPR–Cas Systems Direct RNA-Guided DNA Integration. Nature 2019, 571, 219–225. 10.1038/s41586-019-1323-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z. H.; Wu J.; Liu J. Q.; Min D.; Liu D. F.; Li W. W.; Yu H. Q. Repurposing CRISPR RNA-Guided Integrases System for One-Step, Efficient Genomic Integration of Ultra-Long DNA Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 7739–7750. 10.1093/NAR/GKAC554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Ren Z.-H.; Tang N.; Chai G.; Zhang H.; Zhang Y.; Ma J.; Wu Z.; Shen X.; Huang X.; Luo G.-Z.; Ji Q. Targeted Genetic Screening in Bacteria with a Cas12k-Guided Transposase. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109635 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo P. L. H.; Ronda C.; Klompe S. E.; Chen E. E.; Acree C.; Wang H. H.; Sternberg S. H. CRISPR RNA-Guided Integrases for High-Efficiency, Multiplexed Bacterial Genome Engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 480–489. 10.1038/s41587-020-00745-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. U.; Tsai A. W. L.; Chen T. H.; Peters J. E.; Kellogg E. H. Mechanistic Details of CRISPR-Associated Transposon Recruitment and Integration Revealed by Cryo-EM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119, e2202590119 10.1073/pnas.2202590119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenjo-Castaño F.; Sofos N.; López-Méndez B.; Stutzke L. S.; Fuglsang A.; Stella S.; Montoya G. Structure of the TnsB Transposase-DNA Complex of Type V-K CRISPR-Associated Transposon. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5792 10.1038/S41467-022-33504-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. U.; Tsai A. W. L.; Rizo A. N.; Truong V. H.; Wellner T. X.; Schargel R. D.; Kellogg E. H. Structures of the Holo CRISPR RNA-Guided Transposon Integration Complex. Nature 2023, 613, 775–782. 10.1038/S41586-022-05573-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querques I.; Schmitz M.; Oberli S.; Chanez C.; Jinek M. Target Site Selection and Remodeling by Type V CRISPR-Transposon Systems. Nature 2021, 599, 497–502. 10.1038/S41586-021-04030-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliu E.; Lee K.; Wang K. CRISPR RNA-Guided Integrase Enables High-efficiency Targeted Genome Engineering in Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1916–1927. 10.1111/PBI.13872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S. R.; Gaines J.; Roop R. M.; Farrand S. K. Broad-Host-Range Expression Vectors with Tightly Regulated Promoters and Their Use to Examine the Influence of TraR and TraM Expression on Ti Plasmid Quorum Sensing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 5053–5062. 10.1128/AEM.01098-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Cuilan W.; Daniel J. J.; Howell M.; Sulaiman A.; Brown P. J. B. Mini-Tn7 Insertion in an Artificial AttTn7 Site Enables Depletion of the Essential Master Regulator CtrA in the Phytopathogen Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 5015–5025. 10.1128/AEM.01392-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Azam T.; Iwata A.; Nishimura A.; Ueda S.; Ishihama A. Growth Phase-Dependent Variation in Protein Composition of the Escherichia Coli Nucleoid. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6361. 10.1128/JB.181.20.6361-6370.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.; Vasileva D.; Suzuki-Minakuchi C.; Okada K.; Luo F.; Igarashi Y.; Nojiri H. Growth Phase-Dependent Expression Profiles of Three Vital H-NS Family Proteins Encoded on the Chromosome of Pseudomonas Putida KT2440 and on the PCAR1 Plasmid. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 188 10.1186/s12866-017-1091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T. B.; Rand J. M.; Nurani W.; Courtney D. K.; Liu S. A.; Pfleger B. F. Genetic Tools for Reliable Gene Expression and Recombineering in Pseudomonas Putida. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 45, 517–527. 10.1007/s10295-017-2001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiziou S.; Sauveplane V.; Chang H. J.; Clerté C.; Declerck N.; Jules M.; Bonnet J. A Part Toolbox to Tune Genetic Expression in Bacillus Subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 7495–7508. 10.1093/nar/gkw624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y.; Song M.; Li F.; Li C.; Lin X.; Chen Y.; Chen Y.; Xu J.; Ding Q.; Song H. A Synthetic Plasmid Toolkit for Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 410. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster L. A.; Reisch C. R. A Plasmid Toolbox for Controlled Gene Expression across the Proteobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 7189–7202. 10.1093/nar/gkab496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren A.; Garrity G. M. Valid Publication of the Names of Forty-Two Phyla of Prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 005056 10.1099/ijsem.0.005056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle F.; Campillo T.; Vial L.; Baude J.; Costechareyre D.; Chapulliot D.; Shams M.; Abrouk D.; Lavire C.; Oger-Desfeux C.; Hommais F.; Guéguen L.; Daubin V.; Muller D.; Nesme X. Genomic Species Are Ecological Species as Revealed by Comparative Genomics in Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Genome Biol. Evol. 2011, 3, 762–781. 10.1093/gbe/evr070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H.; Mima T.; Casart Y.; Rholl D.; Kumar A.; Beacham I. R.; Schweizer H. P. Genetic Tools for Select-Agent-Compliant Manipulation of Burkholderia Pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1064–1075. 10.1128/AEM.02430-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J.; Russell D. W.. Commonly Used Techniques in Molecular Cloning. Appendix 8; CSH LAboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 2001; pp A8. 1–A8.55. [Google Scholar]

- Palani N.Transposon Insertion Sequencing (Tn-seq) Library Preparation Protocol-Includes UMI for PCR Duplicate Removal Protocols 2019 10.17504/protocols.io.w9sfh6e. [DOI]

- Li H.; Durbin R. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna: https://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Rich B.Table 1: Tables of Descriptive Statistics in HTML, R package version 1.4.2; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=table1.

- Caspi R.; Pacek M.; Consiglieri G.; Helinski D. R.; Toukdarian A.; Konieczny I. A Broad Host Range Replicon with Different Requirements for Replication Initiation in Three Bacterial Species. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 3262–3271. 10.1093/EMBOJ/20.12.3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kües U.; Stahl U. Replication of Plasmids in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1989, 53, 491–516. 10.1128/MR.53.4.491-516.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H.; Schweizer H. P. Mini-Tn7 Insertion in Bacteria with Single AttTn7 Sites: Example Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 153–161. 10.1038/nprot.2006.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz R.; Bujard H. Independent and Tight Regulation of Transcriptional Units in Escherichia Coli via the LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I1-I2regulatory Elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 1203–1210. 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y.; Sander J. D.; Reyon D.; Cascio V. M.; Joung J. K. Improving CRISPR-Cas Nuclease Specificity Using Truncated Guide RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 279–284. 10.1038/nbt.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson A. W.; Hosny N.; Swanson Z. A.; Hering B. J.; Burlak C. Optimizing SgRNA Length to Improve Target Specificity and Efficiency for the GGTA1 Gene Using the CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing System. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0226107 10.1371/journal.pone.0226107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Xiao T.; Chen C.-H. H.; Li W.; Meyer C. A.; Wu Q.; Wu D.; Cong L.; Zhang F.; Liu J. S.; Brown M.; Liu X. S. Sequence Determinants of Improved CRISPR SgRNA Design. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1147–1157. 10.1101/gr.191452.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.-P.; Li X.-L.; Neises A.; Chen W.; Hu L.-P.; Ji G.-Z.; Yu J.-Y.; Xu J.; Yuan W.-P.; Cheng T.; Zhang X.-B. Different Effects of SgRNA Length on CRISPR-Mediated Gene Knockout Efficiency. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28566 10.1038/srep28566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran F. A.; Hsu P. D.; Lin C. Y.; Gootenberg J. S.; Konermann S.; Trevino A. E.; Scott D. A.; Inoue A.; Matoba S.; Zhang Y.; Zhang F. Double Nicking by RNA-Guided CRISPR Cas9 for Enhanced Genome Editing Specificity. Cell 2013, 154, 1380–1389. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang Y.; Jia G.; Choi J.; Ma H.; Anaya E.; Ye C.; Shankar P.; Wu H. Optimizing SgRNA Structure to Improve CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Efficiency. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 280. 10.1186/s13059-015-0846-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J. R.; Rubin A. J.; Davis J. H.; Ajo-Franklin C. M.; Cumbers J.; Czar M. J.; de Mora K.; Glieberman A. L.; Monie D. D.; Endy D. Measuring the Activity of BioBrick Promoters Using an in Vivo Reference Standard. J. Biol. Eng. 2009, 3, 1–13. 10.1186/1754-1611-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]