Abstract

While aerobic exercise training (AET) has generally been shown to improve six-minute walk test (6MWT) distance (6MWD) in patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH), a substantial number of patients appear to adapt differently, with minimal or even negative changes in 6MWT distance being reported.

Purpose:

To compare post-aerobic exercise training adaptations in cardiorespiratory functional capacity across three groups of patients with PH: those with high (HI), low (LI) and negative (NEG) post-training increases in 6MWD.

Methods:

Participants were 25 females (age 54±11 years; BMI 31±7 kg/m2) who completed a vigorous, 10-week, thrice weekly, supervised treadmill walking exercise program. Cardiopulmonary exercise tests (CPET) and 6MWT were completed before and after training. Ten of the 25 participants were classified as HI (range = 47 – 143 meters), 11 were classified as LI (range = 4 – 37 meters) and 4 were classified as NEG (range = −17 to −53 meters).

Results:

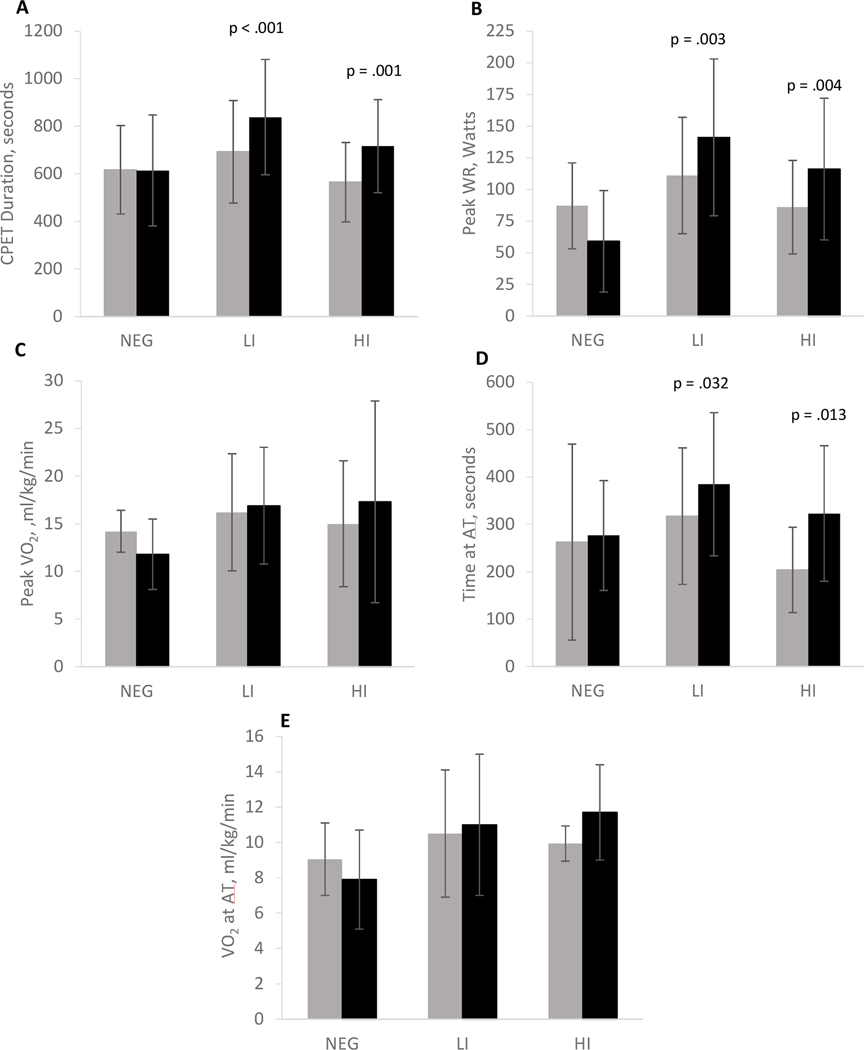

Peak CPET duration, WR and time to anaerobic threshold (AT) were significantly higher (p < 0.05) after training in both the LI and HI groups but not in the NEG group. There was a significant improvement in VE/VCO2 (p = .042), PETCO2 (p = .011) and TV (p = .050) in the HI group after training, but not in the NEG or LI group.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that sustained ventilatory inefficiency and restricted respiratory buffering may mediate exercise intolerance and impede the ability to adapt to exercise training in some patients with PH.

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a rare disease involving complex pathophysiological interactions among the pulmonary, cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems.1 Vascular changes such as impaired vasodilation of the pulmonary microvasculature lead to increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), which during exercise results in dyspnea, fatigue and physical activity intolerance.2 In severe cases, the progressive increase in PVR can lead to cor pulmonale and death. Diagnosis of PH often occurs with the patient becoming symptomatic (NYHA III/NYHA IV) during later stages of the disease,3 particularly in those who are less physically active. Medications are available for the treatment of PH to prolong life, yet the prognosis remains poor.4 There is currently no known cure for PH.

Aerobic exercise training (AET) has been shown to improve exercise intolerance in patients with PH beyond gains attributable to those associated with pharmacotherapy.5–8 The magnitude of AET induced increases in cardiorespiratory endurance and exercise tolerance have been associated with increased longevity and improved health related quality of life (QOL) in patients with PH.5,7,9 However, not all patients with PH who participate in AET are able to realize a clinically important improvement. Grunig et al.10 found that 14.2% of patients with PH had no significant improvement in total distance walked on a six-minute walk test (6MWT) following supervised, inpatient aerobic exercise training. Characteristic differences in cardiorespiratory function between those who adapt to AET and those who have a low to negligible improvement remain elusive and understudied.

The distance covered on a 6MWT (6MWD) is a measure of cardiorespiratory endurance, and disease progression in patients with PH. Greater 6MWD has been associated with higher peak oxygen consumption (VO2), lower ventilatory equivalents for carbon dioxide (VE/VCO2) and higher oxygen pulse during a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET), and lower mortality.11,12 The 6MWD is also frequently used as a functional outcome measure and is thought to be an important predictor of survival in this population.13 Findings from several studies have suggested that improved hemodynamics may be associated with improved 6MWD while other studies have failed to find an association.14 The 6MWD has been used as a measure of survival with a distance over 500m indicating good survival prognosis, and less than 300m associated with poor survival prognosis.1 While the 6MWT is widely used by physicians and researchers, there are limitations to its use that include variability in results associated with age, height, weight, ethnicity, disease status, comorbidities, supplemental O2 use, instructions by the technician, learning effects, patient’s mood and motivation and encouragement level.15,16 Nonetheless, understanding the mechanisms underlying 6MWT performance and 6MWD improvement may begin to fill informational gaps regarding the mechanisms through which this field test is prognostic.

The aim of this study was to characterize aerobic exercise induced changes in cardiopulmonary fitness among groups of patients who adapt with changes above versus below the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in 6MWT distance.

Materials and Methodology

Participants

Participants in this study were enrolled in the National Institutes of Health Exercise Therapy for Advance Lung Disease Trials [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00678821]. Previously reported findings from this study include improved overall exercise capacity, fatigue and physical activity tolerance, and health related QOL.7,17 Prior to beginning recruitment, this protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions (NIH: 08-CC-0133; Inova: 08.129; GMU: 6057).

Participants were recruited from the greater Washington DC area through Inova Fairfax Hospital (Falls Church, VA) or the National Institutes of Health (NIH) campus (Bethesda, MD) between September 2009 and October 2011. All World Health Organization (WHO) groups of PH8 with varying etiologies were included in this study. PH was identified by a resting mean pulmonary arterial pressure of 25 mmHg or higher measured by a right-heart catherization. Participants were stable on all PH related medications for 3 months, sedentary and had no pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) within 6 months of study participation. Participants completing a 6MWT of ≥400 meters and classified as WHO/New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I, as well as participants completing ≤50 meters during the 6MWT and classified as WHO/NYHA class IV were excluded to avoid “ceiling” or “floor” effects. Participants with obstructive disease (FEV1/FVC ≤65), history of heart disease with an ejection fraction of <40%, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 18 mmHg, a history of severe hepatic, renal or mitochondrial dysfunction, psychiatric disease or the use of medications limiting exercise, illicit drug use, tobacco use or pregnancy were excluded. Enrolled participants were instructed to maintain their current dietary and physical activity lifestyle. All participants were advised of potential risks and benefits of their participation. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants prior to enrollment in this study.

Study Design

All participants enrolled in this study completed a 6MWT and treadmill cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) to volitional fatigue at baseline and following AET. Non-invasive cardiac output (Qt) and stroke volume (SV) were also measured at rest and during CPET. Participants with a prescription for supplemental oxygen (O2) performed the CPET breathing a hyperoxic gas mixture (containing a fraction of inspired O2 of 40%) and the 6MWT with an O2 flow of 6 L/min. One participant was medically prescribed an O2 flow rate of 10 L/min with exercise, therefore, the 6MWT was performed on 10 L/min. Follow-up tests for all participants were performed using the same concentration of supplemental O2. O2 need during training was based on maintaining arterial oxygen saturation levels above 90%.

In the current analysis, all participants were assigned to one of three groups based on their 6MWT performance after AET: high improvement (HI), low to neglible improvement (LI) and a negative response (NEG) group, in which 6MWT distance declined after AET. The group designations were defined by clear cutpoints in the 6MWT change distribution after AET and the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 38–41 meters18,19 criteria for 6MWT performance in PH.

Procedures

Six-minute Walk Test (6MWT):

Resting pulse and arterial oxygen saturation were measured by an identical procedure for all participants before, during and after the 6MWT in accordance with American Thoracic Society recommendations.20 Participants were instructed to walk as far as possible around a predetermined course measuring 80 meters for six consecutive minutes. Short breaks were permitted as needed but participants were not allowed to sit during the break. Heart rate, rating of perceived exertion, rating of perceived dyspnea and oxygen saturation were recorded every lap (80 m). Participants were instructed to sit down and rest immediately upon completion of six minutes of walking. Pulse and oxygen saturation were monitored and recorded for 10 minutes following the test. The post-pre training change in 6MWD was determined and the baseline distance was used as the primary classification for participant group classification and assignment for this study.

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test (CPET):

Pulmonary gas exchange was measured continuously using breath-by-breath open circuit spirometry (Medgraphics, Cardio 2 Ultima, Medical Graphics Corp, St. Paul, MN), using a neoprene facemask that was secured across the face and around the mouth and nose of the participant. Heart rate (HR) was continuously recorded by a 12-lead EKG system that integrated directly with the cardiopulmonary exercise testing system. Infrared pulse oximetry and bioelectrical impedance cardiographic measurements were monitored continuously and recorded throughout the resting and testing procedures. Blood pressure was also measured at rest, quiet standing and every 2 minutes during the CPET.

The CPET was a modified Naughton protocol7 where the treadmill speed and/or grade were gradually increased every 2 minutes. The target test endpoint was volitional exhaustion, operationally defined as the subject’s expression of the inability to continue due to fatigue and/or symptoms despite strong encouragement by the exercise staff. The anaerobic threshold (AT) was determined by plotting oxygen consumption on expired volume breath-by-breath and applying the V-Slope method for quantification of the AT deflection point.17,21 Peak VO2 was determined from the last 8 breaths achieved by the participant. Participants with a prescription for supplemental oxygen performed the exercise test breathing 40% FiO2. Seated resting and quiet standing pre-exercise data were collected prior to the beginning of the test.

Bioelectrical Impedance Cardiography (ZCG):

Bioelectrical impedance cardiography (ZCG) was used to determine cardiac output (Qt) and stroke volume (SV) non-invasively during rest and exercise using a PhysioFlow® Enduro bioimpedance plethysmograph (Manatec Biomedical, France). The ZCG system measures total electrical conductivity of the thorax and the changes to electrical current, which vary only with changes in fluid volume. This signal is measured through silver chloride electrodes placed on the participant’s chest and neck. The dedicated software in the system plotted the changes in transthoracic impedance during the cardiac cycle on time, subsequently calculating cardiac stroke volume (SV) by applying an algorithm to the waveform. SV was then multiplied by HR to quantify cardiac output (Qt).

Exercise Training:

Participants completed 10 weeks of supervised treadmill walking, three times a week, at an intensity of 70–80% of heart rate reserve (; Equation 1).22 CPET was used to determine peak .

| (Equation 1) |

The initial session was 30 minutes with one minute being added to each subsequent session until 45 minutes was achieved. Participants were required to attend at least 80% of the sessions (i.e., 24 sessions in 10 weeks) for their data to be included in the analysis. Supplemental oxygen was provided to participants with a prescription, and those with an SpO2 less than 90% during the exercise sessions.

Statistical Analysis:

Group demographics were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to determine significant differences in measures of cardiorespiratory function between HI, LI and NEG while controlling for covariant influences such as the use of supplemental O2. Bonferroni post hoc analyses were used to determine differences between groups and correct for multiple comparisons. Paired t-tests were used to determine within-group differences in CPET and cardiorespiratory variables before and after AET. Pearson Product-Moment correlations were used to assess correlations between the change in 6MWD and other variables of interest (e.g. VE/VCO2, PETCO2 and time at AT). All analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) version 25. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant. Data are reported as means ± SD.

Results

Demographics

Of the 302 patients screened, 33 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants withdrew from the study before completion, two participants were excluded due to medication changes, one failed to complete final testing and one was excluded due to an unusual response during testing in which the participant’s VO2 decreased in response to an increase in workload. By chance, 25 of the 26 participants who met the inclusion criteria were female. Since there was only one male enrolled in the study, his data were also excluded due to a potential gender bias relative to both disease maladaptation and exercise response. The remaining data from 25 female participants (Table 1), who completed between 24 and 30 sessions of AET, over 10 weeks, as well as all the testing procedures were included in the analyses. Etiological distribution was primarily (88%) World Health Organization (WHO) Group I (primary arterial hypertension), 4% WHO Group III (PH associated with interstitial lung disease), 4% WHO Group IV (chronic thromboembolic PH) and 4% WHO Group V (PH due to blood and other disorders). Participants were assigned to one of three groups based on their improvement in 6MWD following AET: high improvement group (HI) defined as Δ6MWD of 47 to 143 meters (n=10), low improvement group (LI) defined as Δ6MWD of 4 to 37 meters (n=11), and negative response group (NEG) defined as Δ6MWD of −17 to −53 meters (n=4). The HI and LI groups were determined from an observed breakpoint in 6MWD improvement (Figure 1), which coincided with the MCID for a clinically significant improvement in 6MWD (38–41 meters).18,19 6MWD increased significantly more in HI than in LI (85.6 ±31.2 meters vs 19.6 ± 8.7 meters, p < .0001) whereas 6MWD significantly declined by −28.0 ± 16.8 meters (p = .045) in NEG after AET. There were no significant group differences in demographics (Table 1), cardiac hemodynamics, pulmonary function, or CPET measures (Table 2) at baseline.

Table 1.

Group Demographic Characteristics

| NEG (n = 4) | LI (n = 11) | HI (n = 10) | p - value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, yr | 55.0 ± 15.0 | 51.5 ± 10.4 | 57.4 ± 9.3 | .458 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 ± 2.5 | 31.0 ± 7.87 | 32.1 ± 7.9 | .569 |

| Hemodynamic variables | ||||

| mPAP, mmHg | 40.5 ± 10.4 | 48.9 ± 16.2 | 39.4 ±12.0 | .279 |

| RAP, mmHg | 6.0 ± 3.5 | 10.6 ± 5.0 | 6.7 ± 6.1 | .173 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 10.8 ± 3.1 | 11.1 ± 3.3 | 8.9 ± 3.3 | .289 |

| PVR, Wood units | 435.8 ± 150.8 | 678.4 ± 402.9 | 479.7 ± 212.5 | .252 |

| Qt, L/min | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | .769 |

| Pulmonary function | ||||

| FVC, % predicted | 70.5 ± 14.5 | 62.7 ± 19.0 | 74.9 ± 13.4 | .261 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 70 ± 12.5 | 61.9 ± 16.5 | 70.9 ± 14.9 | .395 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 80.5 ± 11.6 | 79.2 ± 8.0 | 77.8 ± 14.2 | .913 |

| DLCO, % predicted | 33.3 ± 9.6 | 49.6 ± 30.7 | 40.5 ± 15.0 | .469 |

| NYHA/WHO functional classification, % | ||||

| Class I | 0% | 9% | 0% | |

| Class II | 50% | 55% | 50% | |

| Class III | 50% | 27% | 50% | |

| Class IV | 0% | 9% | 0% | |

| Medications, % | ||||

| No medications | 0% | 9% | 0% | |

| Monotherapy | 25% | 27% | 40% | |

| Dual therapy | 75% | 9% | 30% | |

| Triple therapy | 0% | 45% | 30% | |

| Quadruple therapy | 0% | 9% | 0% | |

| Supplemental O2 | 75% | 64% | 50% | |

BMI = body mass index; mPAP = mean pulmonary arterial pressure; RAP = right atrial pressure; PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; FVC = forced vital capacity, FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1/FVC = forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity ratio; DLCO = diffusion capacity of the lungs Values are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified p-values are for ANOVA between group main effects.

Figure 1:

Changes in 6MWT after AET. Horizontal dashed line represents 6MWT MCID. NEG  , LI

, LI  , HI

, HI  . 6MWT = six-minute walk test; MCID = minimal clinically important difference.

. 6MWT = six-minute walk test; MCID = minimal clinically important difference.

Table 2.

Baseline Cardiopulmonary Functional Characteristics

| NEG (n = 4) | LI (n = 11) | HI (n = 10) | p - value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 6MWD, m | 425.5 ± 96.8 | 407.4 ± 86.6 | 373.1 ± 86.1 | .529 |

| Peak VO2, ml/kg/min | 14.2 ± 2.2 | 16.2 ± 6.2 | 15.0 ± 6.6 | .823 |

| Peak WR, watts | 86.7 ± 34.1 | 110.5 ± 46.5 | 85.7 ± 37.2 | .354 |

| Time to fatigue, sec | 617.0 ± 186.5 | 693.0 ± 215.5 | 564.5 ± 166.6 | .328 |

| HR at peak, bpm | 138.2 ± 14.8 | 141.7 ± 14.8 | 137.7 ± 12.9 | .790 |

| SV at peak, ml | 94.0 ± 21.0a | 103.0 ± 23.9 | 95.0 ± 24.5b | .723 |

| Qt at peak, L/min | 13.1 ± 1.9a | 14.8 ± 4.4 | 13.4 ± 3.6b | .693 |

| a-vO2 Diff at peak | 8.3 ± 0.2a | 9.8 ± 6.8 | 8.6 ± 3.1b | .864 |

| VE peak, L/min | 40.4 ± 3.04 | 40.3 ± 11.0 | 48.6 ± 14.2 | .249 |

| VCO2 peak, L/min | 1045.6 ± 196.6 | 1168.9 ± 310.3 | 1194.1 ± 281.8 | .667 |

| VE/Qt peak | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 1.0 | .242 |

| VE/VO2 at peak | 39.0 ± 4.4 | 37.8 ± 15.2 | 43.0 ± 16.9 | .725 |

| VE/VCO2 at peak | 39.3 ± 6.2 | 35.3 ± 8.1 | 40.0 ± 8.8 | .295 |

| PETO2 at peak, mmHg | 147.9 ± 62.3 | 154.7 ± 55.1 | 153.8 ± 55.1 | .975 |

| PETCO2 at peak, mmHg | 32.9 ± 4.3 | 38.0 ± 9.0 | 32.4 ± 6.7 | .221 |

| Tidal Volume, ml | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0,4 | .158 |

| Time at AT, sec | 262.8 ± 207.0 | 317.4 ± 144.7 | 204.1 ± 89.7 | .188 |

6MWD = six-minute walk distance; VO2 = oxygen consumption; WR = work rate; HR = heart rate; SV = stroke volume; Qt = cardiac output; QI = cardiac index; a-vO2 Diff = arteriovenous oxygen difference; VE = ventilation; VE/VO2 = ventilatory efficiency for O2; VE/VCO2 = ventilatory efficiency for CO2; PETO2 = expired end tidal O2; PETCO2 = expired end tidal CO2; AT = anaerobic threshold

p-values are for ANOVA between group main effects.

Values are expressed as mean ± SD

Due to equipment malfunction, n = 3

Due to equipment malfunction, n = 7

No significant differences were observed between groups in the number of exercise sessions completed, total exercise time over the course of the training regimen (Table 3), or the intensity of exercise during the training sessions measured via heart rate during training. Supplemental oxygen was provided to 50% of participants in the NEG, 63% of participants in the LI group, and 50% of participants in the HI group. No difference in groups was observed for supplemental oxygen use.

Table 3.

Summary of Aerobic Exercise Training between Groups

| NEG (n = 4) | LI (n = 11) | HI (n = 10) | p - value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Sessions completed (#) | 26.0 ± 1.4 | 26.2 ± 1.7 | 27.8 ± 2.4 | .135 |

| Total time (min) | 1022.3 ± 64.3 | 1003.9 ± 108.7 | 1064.9 ± 131.1 | .508 |

Definitions of abbreviations: min = minute,

Values are expressed as mean ± SD

p-values are for ANOVA between group main effects

After AET, significant increases were observed in CPET duration and peak WR in HI and LI, whereas no increase was observed in WR or CPET duration in the NEG group (Figure 2). Significant changes in cardiorespiratory function as measured during the CPET were not observed after AET from baseline for any of the groups (Table 4). A significant decline in VE/VCO2 was observed in NEG (p = .004) whereas an observable improvement occurred in HI (p = .007) after training (Figure 3). PETCO2 increased significantly in HI (p= .011) and LI (p = .026) but a significant change in PETCO2 was not observed in NEG (Figure 3). Time at AT was significantly higher in the LI (p = .032) and HI (p = .013) groups following AET but not significantly different from baseline in the NEG group after AET (Figure 2). VO2 at AT was not significantly different in any group after AET (Figure 2). Figure 4 depicts significant correlations between the change scores of 6MWD and PETCO2 (p = .041), and 6MWD and time at AT (p = .046) with a trend towards significance between the change in 6MWD and VE/VCO2 (p = .059).

Figure 2:

Changes in CPET duration (A), peak WR (B), peak VO2 (C), time at AT (D) and VO2 at AT (E) for NEG, LI and HI before  and after AET

and after AET  . P-values represent significant differences within each of the groups post vs pre AET. CPET = cardiopulmonary exercise test; WR = work rate; VO2 = peak oxygen consumption; AT = anaerobic threshold; AET = aerobic exercise training.

. P-values represent significant differences within each of the groups post vs pre AET. CPET = cardiopulmonary exercise test; WR = work rate; VO2 = peak oxygen consumption; AT = anaerobic threshold; AET = aerobic exercise training.

Table 4.

Changes in Cardiorespiratory Function by Group

| NEG (n = 4) | LI (n = 11) | HI (n = 10) | p - value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Aerobic capacity | ||||

| ΔPeak VO2, ml/kg/min | −2.4 ± 1.9 | 0.6 ± 3.3 | 2.2 ± 6.3 | .261 |

| ΔTime at AT, sec | 14.0 ± 91.4 | 67.4 ± 89.5 | 118.6 ± 121.2 | .229 |

| Ventilatory capacity | ||||

| ΔVE at peak, L/min | 1.0 ± 14.2 | 0.9 ± 7.1 | 1.5 ± 9.5 | .990 |

| ΔPeak respiratory rate breaths/min | 3.3 ± 5.9 | 0.1 ± 7.2 | −0.7 ± 7.2 | .618 |

| ΔVE/VO2 at peak | 7.1 ± 6.0 | −0.1 ± 6.0 | −2.2 ± 6.5 | .058 |

| ΔEnd tidal O2, mmHg | 1.7 ± 3.9 | 2.2 ± 12.3 | −0.5 ± 5.3 | .788 |

| Cardiovascular capacity | ||||

| ΔPeak HR, bpm | −14.5 ± 11.8 | −5.0 ± 15.5 | −0.6 ± 12.0 | .253 |

| ΔPeak SV, ml | 2.7 ± 12.2a | −4.3 ±24.6 | 19.8 ± 60.4b | .435 |

| ΔPeak Qt, L | 0.7 ± 1.5a | −1.1 ± 3.7 | 3.04 ± 9.0b | .344 |

Definition of abbreviations: Δ denotes the change after AET from baseline measures during the cardiopulmonary exercise test; VO2 = oxygen consumption; AT = anaerobic threshold; VE = minute ventilation; VE/VCO2 = ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide, VE/VO2 = ventilatory equivalent for oxygen; O2 = oxygen; CO2 = carbon dioxide; HR = heart rate; SV = stroke volume; Qt = cardiac output; All values are change values after AET; p-values are for ANCOVA within group main effects Values are expressed as mean ± SD

Due to equipment malfunction, n = 3

Due to equipment malfunction, n = 7

Figure 3:

Changes in VE/VCO2 (A), PETCO2 (B), VE (C), VCO2 (D) and tidal volume (E) for NEG, LI and HI before AET  and after AET

and after AET  . P-values represent significant differences within each of the groups post vs pre AET.VE/VCO2 = ventilatory quotient for carbon dioxide; PETCO2 = end tidal partial carbon dioxide pressure; VE = expired minute ventilation, VCO2 = expired volume of carbon dioxide.

. P-values represent significant differences within each of the groups post vs pre AET.VE/VCO2 = ventilatory quotient for carbon dioxide; PETCO2 = end tidal partial carbon dioxide pressure; VE = expired minute ventilation, VCO2 = expired volume of carbon dioxide.

Figure 4:

Correlation between changes in 6MWD and VE/VCO2 (A), PETCO2 (B) and time at AT (C) for the NEG  , LI

, LI  and HI

and HI  groups. 6MWD = 6-minute walk distance; VCO2 = ventilatory quotient for carbon dioxide; PETCO2 = end tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure; AT = anaerobic threshold.

groups. 6MWD = 6-minute walk distance; VCO2 = ventilatory quotient for carbon dioxide; PETCO2 = end tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure; AT = anaerobic threshold.

Discussion

A significant improvement in exercise tolerance was observed after AET, as indicated by increases in CPET duration and peak WR, in both HI and LI. The improved exercise endurance was accompanied by training induced improvements in indices of respiratory buffering, including prolonged time to AT, decreased peak VE/VCO2 and increased PETCO2, in HI. A significant positive correlation between a change in 6MWD and time to AT suggesting a later onset of fatigue in those who improved their 6MWD. The higher VE/VCO2 in the small NEG subset suggested that buffering capacity may have declined after AET in this group. These changes occurred without changes in VE, VCO2, or other measures of pulmonary function during CPET, and without changes in central circulatory oxygen delivery at peak exercise.

The 6MWT is a widely accepted measure of functional capacity in patients with cardiopulmonary disease and has been associated with both VO2 peak and mortality.23–25 Exercise capacity measured by the 6MWT has been shown to be a predictor of longevity in patients with PH23,26–28 (6MWD ≤ 300 meters = poor survival; ≥ 600 meters = prolonged survival1). A study following patients receiving Bosentan therapy found an association between increased mortality and a 6WMD of <358 m 29 and Miyamoto et al,24 found that patients with PH who had a 6MWD < 332 m had a significantly lower survival rate than those who walked farther. An analysis of data from the REVEAL registry (2,716 patients) inferred an increase in the risk of mortality for patients who walked <165 m.26 In the current study, post-AET increases in indices of respiratory buffering were concomitant with increases in 6MWD, but not with peak VO2.

In healthy adults, peripheral fatigue, which leads to exercise and physical activity intolerance, is mechanized by inadequate maintenance of bioenergetics and waste removal needed to continue physical activity.30,31 During higher energy demands, reduction of NAD increases faster than oxidization of NADH leading to a dissociation of hydrogen ions (H+) in the muscle sarcoplasm.

During more intense muscular activity, H+ and pyruvate form lactic acid which is buffered by bicarbonate. When the production of lactate exceeds the bicarbonate buffering capacity, lactate and H+ accumulate resulting in diminished intracellular function.32 Lactate diffuses out of the cell and into the plasma where it is buffered to H2O and CO2 at the alveolar membrane.32 The majority of this excess or nonmetabolic CO2 is exhaled in addition to the metabolic CO2 produced as a by-product of Krebs cycle activity. Increased plasma CO2 and decreased plasma pH stimulate ventilation in an attempt to offset further decreases in pH. Disproportional increases in VE/VCO2 above those occurring linearly with the CPET power increments or VO2 progression, is taken to reflect the onset of exercise induced acidemia and increased respiratory buffering.17,33

In patients with PH, increased VE/VCO2 has been associated with ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch, representing an excess in physiological dead space (VD/VT).12 Reduced capillary reserve in the pulmonary microvascular bed may be responsible for V/Q mismatch. This may lead to an increase in ventilatory drive due to an increase in metabolic demand. Changes in ventilatory drive can contribute to reduced exercise tolerance and increased dyspnea. VE/VCO2 has also been associated with symptoms of reduced exercise capacity in patients with congestive heart failure.34,35 In the current study, VE/VCO2 was increased after AET in NEG and occurred with a reduction in exercise tolerance. Conversely, a slight decrease in VE/VCO2 accompanied by an improvement in exercise tolerance was observed in HI. There was a significant positive correlation between change in 6MWD and PETCO2 (Figure 4). The improvement in VE/VCO2 and exercise tolerance occurred concomitantly with an increase in PETCO2, implicating improved respiratory buffering capacity and ventilatory efficiency as mechanisms possibly contributing to improved exercise tolerance.

Central limitations appear to restrict exercise-induced improvements in VO2 peak following AET in participants with PH and may explain the lack of increase in peak cardiorespiratory capacity in the participants in the current study. These limitations are likely associated with reduced vascular compliance resulting from vascular remodeling and increases in right ventricular work requirements to overcome the pulmonary afterload.36 Higher afterload and encroachment on contractile capacity may diminish Qt, provoking chronotropic compensation during rest, which may become exacerbated during exercise. Higher heart rates tend to shorten ventricular filling time, potentiating the decline of Qt leading to RV dysfunction.37 Due to closed system hemodynamics, normal left ventricular function is dependent on adequate right heart filling and pulmonary vascular function. Studies have reported neither a significant decline in Qt, reduction in left ventricular filling conditions or decrease in myocardial inotropicity after AET in patients with PH.7,38

The sample recruited by convenience in the current study is likely not representative of the PH population at large. By chance, all of the participants were women, precluding generalizing across the PH gender distribution. Moreover, the size of the sample could have resulted in being under powering on some of the variables, particularly in the very small NEG group. While all etiologies of PH were included in this study, most of the participants were WHO Group 1 PH (88%). Indeed, the etiological distribution may influence findings from this study, biasing the results with respect to Group 1 specific AET adaptations. Moreover, the preponderance of participants in Group 1 prevented comparisons based on WHO Group comparisons across the HI, LI, and NEG subsets.

Conclusion

Increases in exercise tolerance, particularly in 6MWD, have been associated with increased longevity in those with PH, whereas declines have been associated with increased mortality. Findings of the current study suggest improved efficiency of CO2 expiration and respiratory buffering capacity as potentially plausible mediators of the increases in exercise tolerance in participants with PH following an aerobic exercise training program. These improvements may explain the attainment of higher workloads and delayed time to fatigue in these participants. The adaptations were observed in those who demonstrated clinically important increases in 6MWD (HI; above the MCID) and to a lesser extent in those who demonstrated more modest improvements in 6MWD (LI). A reduction in the efficiency of CO2 expiration and thus respiratory buffering was observed in those few participants whose 6MWD decreased after AET.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Credit Author Statement

All of the authors contributed to the manuscript. All, except Ms. Ahmad were members of Dr. Morris’ Dissertation Committee. The Manuscript represents in part Dr. Morris’ doctoral dissertation manuscript.

Zoe V. Morris, Ph.D. This manuscript represents in part the dissertation research of Dr. Morris. She identified the research question and proposed the hypothesis, designed the data analysis, prepared and processed the data, completed the analysis, interpreted the data and participated as the lead author.

Lisa M.K. Chin, Ph.D. Dr. Chin provided expertise and input on the research design, data interpretation, and writing and preparation of the original manuscript and the revised version.

Leighton Chan, M.D., MPH. Dr. Chan provided expertise and input on the research design, data interpretation, and writing and preparation of the original manuscript and the revised version. Dr. Chan also provided clinical trial expertise, medical oversight and clinical input for interpretation of the results.

Andrew A. Guccione, Ph.D., DPT. Dr. Guccione provided expertise and input on the research design, data interpretation, and writing and preparation of the original manuscript and the revised version. Dr. Guccione also provided specific input on the relevance of the manuscript to rehabilitation.

Anam Ahmad. Provided expertise in the preparation of the manuscript and provided statistical analyses and expertise in data interpretation.

Randall E. Keyser, Ph.D. Supervised the project and provided expertise in physiology related to the findings. Dr. Keyser was involved in all aspects of the project in his supervisory role and served as the dissertation mentor and Committee Chair for Dr. Morris. Dr. Keyser serves as corresponding author for this project.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2009;30:2493–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwaiblmair M, Faul C, von Scheidt W, Berghaus TMJBPM. Ventilatory efficiency testing as prognostic value in patients with pulmonary hypertension. 2012;12:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deano RC, Glassner-Kolmin C, Rubenfire M, et al. Referral of patients with pulmonary hypertension diagnoses to tertiary pulmonary hypertension centers: the multicenter RePHerral study. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:887–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sisniega C, Zayas N, Pulido T. Advances in medical therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol 2019;34:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker-Grunig T, Klose H, Ehlken N, et al. Efficacy of exercise training in pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:375–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox BD, Kassirer M, Weiss I, et al. Ambulatory rehabilitation improves exercise capacity in patients with pulmonary hypertension. J Card Fail 2011;17:196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan L, Chin LMK, Kennedy M, et al. Benefits of intensive treadmill exercise training on cardiorespiratory function and quality of life in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2013;143:333–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Respir J 2015;46:903–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chia KS, Wong PK, Faux SG, McLachlan CS, Kotlyar E. The benefit of exercise training in pulmonary hypertension: a clinical review. Intern Med J 2017;47:361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grunig E, Lichtblau M, Ehlken N, et al. Safety and efficacy of exercise training in various forms of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2012;40:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savarese G, Paolillo S, Costanzo P, et al. Do changes of 6-minute walk distance predict clinical events in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension? A meta-analysis of 22 randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weatherald J, Farina S, Bruno N, Laveneziana P. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Pulmonary Hypertension. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14:S84–S92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLaughlin VV, Badesch DB, Delcroix M, et al. End points and clinical trial design in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:S97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaughlin VV, Gaine SP, Howard LS, et al. Treatment goals of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:D73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasekaba T, Lee AL, Naughton MT, Williams TJ, Holland AE. The six-minute walk test: a useful metric for the cardiopulmonary patient. Intern Med J 2009;39:495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. ATS statement %J Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1986;60:2020–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert C, Brown MCJ, Cappelleri JC, Carlsson M, McKenna SP. Estimating a minimally important difference in pulmonary arterial hypertension following treatment with sildenafil. Chest 2009;135:137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathai SC, Puhan MA, Lam D, Wise RA. The minimal important difference in the 6-minute walk test for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:428–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1428–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider DA, Phillips SE, Stoffolano S. The simplified V-slope method of detecting the gas exchange threshold. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993;25:1180–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karvonen MJ, Kentala E, Mustala O. The effects of training on heart rate; a longitudinal study. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn 1957;35:307–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, et al. Survival in patients with idiopathic, familial, and anorexigen-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Circulation 2010;122:156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyamoto S, Nagaya N, Satoh TJA, J Respir Crit Care Med. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of six-minute walk test in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Comparison with cardiopulmonary exercise testing. 2000;161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paciocco G, Martinez FJ, Bossone E, Pielsticker E, Gillespie B, Rubenfire M. Oxygen desaturation on the six-minute walk test and mortality in untreated primary pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2001;17:647–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, et al. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation 2010;122:164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyamoto S, Nagaya N, Satoh T, et al. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of six-minute walk test in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Comparison with cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:487–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nickel N, Golpon H, Greer M, et al. The prognostic impact of follow-up assessments in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2012;39:589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLaughlin VV, Sitbon O, Badesch DB, et al. Survival with first-line bosentan in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2005;25:244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keyser RE. Peripheral fatigue: high-energy phosphates and hydrogen ions. PM R 2010;2:347–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks GA, Fahey TD, Baldwin KM. Exercise physiology : human bioenergetics and its applications. 4th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whipp BJ. Physiological mechanisms dissociating pulmonary CO2 and O2 exchange dynamics during exercise in humans. Exp Physiol 2007;92:347–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whipp BJ, Ward SA, Wasserman K. Respiratory markers of the anaerobic threshold. Adv Cardiol 1986;35:47–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robbins M, Francis G, Pashkow FJ, et al. Ventilatory and heart rate responses to exercise : better predictors of heart failure mortality than peak oxygen consumption. Circulation 1999;100:2411–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arena R, Myers J, Aslam S, Varughese E, Peberdy MJAHJ. Peak VO2 and VE/VCO2 slope in patients with heart failure: A prognostic comparison. 2004;147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun X, Hansen J, Oudiz R, Wasserman KJC. Exercise pathophysiology in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. 2001;104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waxman AB. Exercise physiology and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2012;55:172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woolstenhulme JG, Guccione AA, Herrick JE, et al. Left Ventricular Function Before and After Aerobic Exercise Training in Women With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2019;39:118–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]