Abstract

In both correlational and experimental settings, studies on women’s vocal preferences have reported negative relationships between perceived attractiveness and men’s vocal pitch, emphasizing the idea of an adaptive preference. However, such consensus on vocal attractiveness has been mostly conducted with native English speakers, but a few evidence suggest that it may be culture-dependent. Moreover, other overlooked acoustic components of vocal quality, such as intonation, perceived breathiness and roughness, may influence vocal attractiveness. In this context, the present study aims to contribute to the literature by investigating vocal attractiveness in an underrepresented language (i.e., French) as well as shedding light on its relationship with understudied acoustic components of vocal quality. More specifically, we investigated the relationships between attractiveness ratings as assessed by female raters and male voice pitch, its variation, the formants’ dispersion and position, and the harmonics-to-noise and jitter ratios. Results show that women were significantly more attracted to lower vocal pitch and higher intonation patterns. However, they did not show any directional preferences for all the other acoustic features. We discuss our results in light of the adaptive functions of vocal preferences in a mate choice context.

Keywords: attractiveness, fundamental frequency, formants, intonation, breathiness, roughness, mate choice

Voice is one of the fundamental aspects of human communication. Indeed, research has reported that acoustic signals provide listeners with information on the quality or condition of the speaker such as sex (Bachorowski & Owren, 1999; Gelfer & Bennett, 2013; Gelfer & Mikos, 2005; Hillenbrand & Clark, 2009), age (Linville & Fisher, 1985; Ptacek & Sander, 1966; Shipp, Qi, Huntley, & Hollien, 1992), sexual orientation (Lyons, Lynch, Brewer, & Bruno, 2014; Munson, McDonald, DeBoe, & White, 2006), physical strength (Sell et al., 2010), sexual behavior and body configuration (Hughes, Dispenza, & Gallup, 2004). In this context, numerous studies have explored the relationships between acoustic features of speech and several auditory impressions, among which attractiveness as assessed by opposite-sex members. Focus has especially been given to sexually dimorphic acoustic traits such as the fundamental frequency (i.e., F0, the acoustic correlate of voice pitch) and the formant frequencies (i.e., the resonances of the vocal tract, the acoustic correlate of perceived timbre; Titze, 1989).

In both correlational and experimental settings, most studies have reported a consistent negative relationship between men’s F0 and attractiveness, that is, women are attracted to relatively low-pitched voices (Bruckert, Lienard, Lacroix, Kreutzer, & Leboucher, 2006; Collins, 2000; Feinberg, Jones, Little, Burt, & Perrett, 2005; Hodges-Simeon, Gaulin, & Puts, 2010; Hughes, Farley, & Rhodes, 2010; Jones, Feinberg, DeBruine, Little, & Vukovic, 2010; Pisanski & Rendall, 2011; Vukovic et al., 2008; Xu, Lee, Wu, Liu, & Birkholz, 2013). Relatively lower formants’ dispersion (i.e., Df, the relative distance between two consecutive formants, which is correlated to the vocal tract length) was also found to be more attractive in male voices (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010; Pisanski & Rendall, 2011). Although two studies have found nonsignificant relationships (Babel, McGuire, & King, 2014; Feinberg et al., 2005), the former reported that larger females tended to prefer increased apparent vocal tract size (which positively correlates with a larger body size), while the latter reported that lower first formants’ frequencies for the vowels /i/ and /u/ were judged as more attractive; still, both studies suggested that apparent vocal tract size influences vocal attractiveness. Additionally, although it has received little attention compared to the F0 and Df, one study has reported that lower F0-SD (i.e., the evolution of F0 through time, which acoustically correlates to micro-variations of intonation patterns in continuous speech) was more attractive in men (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010), although two other studies have reported the opposite relationship (Bruckert et al., 2006; Leongómez et al., 2014).

Under the scope of human sexual selection, three ultimate accounts can be invoked to explain the relationships between females’ preferences and men’s voices. Firstly, there is intersexual selection, which corresponds to the selection exerted by one sex over another. For instance, lower F0s were found to be positively associated to higher circulating testosterone levels in men (Dabbs & Mallinger, 1999; Evans, Neave, Wakelin, & Hamilton, 2008; Hodges-Simeon, Gurven, & Gaulin, 2015; Jost et al., 2018; although see Arnocky, Hodges-Simeon, Ouellette, & Albert, 2018; Bruckert et al., 2006; Puts, Apicella, & Cardenas, 2012), which is known to act as an immunosuppressant (Foo, Nakagawa, Rhodes, & Simmons, 2017). As men possessing high testosterone levels should have a better immune system to bear its costs, lower F0s may thus signal health status as a result of possessing “good genes” (Folstad & Karter, 1992). If so, females may then be attracted to such men as they represent higher genetic quality mates (Arnocky et al., 2018; Hodges-Simeon et al., 2015). Secondly, there is intrasexual selection, which corresponds to the competition among same-sex individuals. For instance, it has been regularly shown that lower F0s and Dfs were perceptually associated to larger, stronger, more masculine and more socially and physically dominant men (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010; Pisanski, Fraccaro, Tigue, O’Connor, & Feinberg, 2014a; Puts, Gaulin, & Verdolini, 2006; Puts, Hodges, Cárdenas, & Gaulin, 2007; Rendall, Vokey, & Nemeth, 2007; Sell et al., 2010), with F0 being recently argued to signal formidability (Puts & Aung, 2019; although see Feinberg, Jones, & Armstrong, 2019). Additionally, lower F0-SD (i.e., monotonous voices) has been hypothesized to be a marker of self-confidence and experience and is also associated to perceived dominance in men (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010). In this context, if women are attracted to more dominant and formidable men, then the formers might display a preference for lower F0s and Dfs. Lastly, a sensory bias may explain vocal attractiveness relationships. Humans possess a cognitive bias to associate deeper vocal frequencies to perceptually larger individuals (Pisanski & Rendall, 2011; Rendall et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2013), although the relationships between vocal pitch and resonant frequencies with height and weight are relatively weak (Pisanski, Fraccaro, Tigue, O’Connor, & Feinberg, 2014b). Nonetheless, if women actually prefer larger men as mates, then they might also prefer men with perceptually deeper vocal features.

According to the source-filter theory of speech production (Taylor & Reby, 2010), the underlying mechanisms of phonation in humans rests on the larynx (the source) and the subsequent filtering of vocal signals by the supralaryngeal vocal tract (the filter). The airflow expelled from the lungs and forced out through the glottis causes mechanical oscillations of the vocal folds within the larynx (i.e., Bernoulli’s principle). The tension, length, and thickness of vocal folds determine the vocal height, which acoustically correlates to the fundamental frequency (i.e., F0). Namely, the sound waves produced by the vocal folds’ oscillations travel through the pharyngeal, the oral, and (possibly) the nasal cavities before being expelled. During this process, the vocal-tract configuration filters the laryngeal flow generated at the glottis by amplifying some frequencies to the detriment of others and, thereby, producing the formant frequencies that lead to the perception of vocal timbre. Moreover, the movements of the articulatory organs involved in speech production such as the tongue, the lips, and the palate modify the shape of the vocal tract, which determine the frequencies associated to the different speech sounds. In humans, both pitch and resonant frequencies display salient sex differences. Indeed, at puberty, males experience a significant influence of androgens, especially testosterone, which entails important consequences on larynx size and vocal folds’ thickness and length, which acoustically lower the voice pitch, deepen the resonant frequencies, and reduce their spacing. This proximate mechanism explains why before puberty, boys and girls exhibit similar vocal frequencies, until the former practically do not overlap with those of adults females (Titze, 1989). Additionally, in the adult life, interindividual variations in vocal features are influenced by age (Linville & Fisher, 1985; Shipp et al., 1992), circulating androgens level (Abitbol, Abitbol, & Abitbol, 1999; Akcam et al., 2004; Dabbs & Mallinger, 1999) and, possibly, to the exposure of testosterone in utero (Fouquet, Pisanski, Mathevon, & Reby, 2016).

Fundamental and formant frequencies aside, a few understudied vocal features also seem to contribute to vocal quality such as vocal breathiness and vocal roughness. Firstly, vocal breathiness can be captured by the harmonics-to-noise ratio (HNR), which corresponds to a ratio between periodic components (i.e., the harmonics, which are multiple integer of the F0) and a nonperiodic component (i.e., noise) comprising a segment of voiced speech (Teixeira, Oliveira, & Lopes, 2013). More specifically, this ratio reflects the efficiency of speech production. The greater the airflow expelled from the lungs into energy of vibration of the vocal folds, the higher the HNR, which is perceptually associated with a more sonorant and harmonic voice. Conversely, a lower HNR is generally associated with a perceptually asthenic, dysphonic, and breathier voice. Secondly, vocal roughness can be captured by the jitter, a measure of the F0 disturbance, which is defined as the parameter capturing the frequency variation at the glottis from cycle to cycle in the sound wave (Hillenbrand, 1988; Rabinov, Kreiman, Gerratt, & Bielamowicz, 1995; Wendahl, 1966). More specifically, the jitter measures the regularity of the vocal folds during successive periods of oscillations. The higher the jitter, the “rougher” sounds the voice. Although little is known about their physiological mechanisms, it has been suggested that both acoustic components may be sensitive to hormonal influx as they both relate to the oscillations of the vocal folds, which possess receptors to circulating androgens (Pisanski et al., 2016).

Vocal breathiness has been suggested to be an important component of vocal attractiveness in female voices (Babel et al., 2014; Van Borsel, Janssens, & De Bodt, 2009), but significant relationships have been reported in both sexes (Šebesta et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2013). Thus, lower HNR profiles (i.e., breathy voices) have been suggested to be more attractive. Additionally, it has been suggested to soften the aggressiveness of males with larger body size (Xu et al., 2013), which in turn could increase their overall attractiveness toward females. On the other hand, little evidence is actually known on whether vocal roughness (as measured with the jitter) significantly contributes to perceived vocal attractiveness as studies that have directly tackled the topic have led to mixed results (Babel et al., 2014; Hughes, Mogilski, & Harrison, 2014; Hughes, Pastizzo, & Gallup, 2008).

Interestingly, experimental consensus regarding the F0 strongly suggests that women’s vocal preferences are consistent independently of the culture under study. Negative relationships have been mostly reported in English-speaking populations such as Americans (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010), Canadians (Feinberg et al., 2005; Pisanski & Rendall, 2011), British (Jones et al., 2010; Vukovic et al., 2008), Scottish (Saxton, Debruine, Jones, Little, & Roberts, 2009), and Australians (Simmons, Peters, & Rhodes, 2011), but also in Dutch (Collins, 2000), German (Weiss & Burkhardt, 2010), Czech (Valentová, Roberts, & Havlíček, 2013), Latvians (Skrinda et al., 2014), and in a small sample of French speakers (Bruckert et al., 2006). Although evidence is scarce, a few findings challenges this view, suggesting that vocal attractiveness may rest on different acoustic cues depending on the culture under study. For instance, one study reported that in a Filipino-speaking group sample, both nulliparous and breastfeeding women showed a preference for feminized (i.e., higher F0) rather than masculinized voice pitch (i.e., lower F0; Shirazi, Puts, & Escasa-Dorne, 2018). In the Hadzas, it has also been reported that women who are breastfeeding prefer men with higher pitch voices as mates, those who are not breastfeeding preferring lower pitch male voices (Apicella & Feinberg, 2009). Interestingly, another study found that Namibian men’s vocal attractiveness could be predicted by their degree of vocal breathiness (measured through the HNR) and not by their voice pitch (Šebesta et al., 2017).

In this context, the aim of this replication study is to investigate culture dependency for vocal attractiveness in an underrepresented language (i.e., French) as well as investigating attractiveness relationships with understudied acoustic features of vocal quality.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in Montpellier, France. The French National Commission of Informatics and Liberty approved the experimental designs of the present study (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL) number 2-17029). Prior to the study, all participants provided the investigator with their written consent.

Stimuli

An aggregate of 58 male participants (mean age = 23, SD = 3.36), native speakers of French, produced the vocal stimuli. These participants were drawn from another study (Suire, Raymond, & Barkat-Defradas, 2018; two of which were not analyzed in that study). They were seated in a quiet, anechoic, soundproof room equipped with a Sennheiser™ BF 515 microphone connected to a PC located in another room. Vocal samples consisted in the recording of a short utterance “Dans la vie, je pense toujours prendre les bonnes decisions et c’est pour cela que je vais gagner” (i.e., “In life, I always think I’ll make the right decision and that is why I will win”). To control for intensity, participants were asked to speak at a constant distance of 15 cm from the microphone. All recordings were encoded using the Adobe© Audition CS6 at a sampling rate of 44 kHz—32 bit—mono then saved as .wav files.

Acoustic Analyses

All recordings were analyzed using the Praat© voice analysis software (Version 6.0.31; Boersma & Weenink, 2017). The mean fundamental frequency (F0) and its variation (F0-SD) were measured using the autocorrelation method with a pitch floor of 75 Hz and a ceiling of 300 Hz (Praat’s recommendation), with other settings kept as default. The HNR (dB) and the local jitter (%), which corresponds to the average absolute difference between consecutive periods, divided by the average period, and calculated in percentage, were measured across the entire utterance using the same settings as the F0. The local jitter corresponds to the jitter ratio, which is commonly used to describe vocal perturbations (Jones, Trabold, Plante, Cheetham, & Earis, 2001). Additionally, intensity (dB) was retrieved using Praat’s default settings. Formant frequencies (F1–F4) were measured at each glottal pulse, targeting voiced speech only, using a formant ceiling of 5,000 Hz (Praat’s recommendation), then averaged across the entire utterance. Then, the formants’ dispersion (Df) was calculated using the following formula (Fitch, 1997):

where Df is the formant dispersion (in Hz), N is the total number of formants measured, and Fi is the frequency (in Hz) of formant i. Lastly, we computed the formants’ position (Pf) using the method described in Puts, Apicella, and Cardenas (2012), which has been argued to be sexually more dimorphic than Df. To compute the formants’ position, we used female vocal stimuli that were drawn from the same study of the male vocal stimuli (nfemale = 68, Suire et al., 2018).

Descriptive statistics of the male vocal stimuli for each acoustic feature are reported in Table 1 and their zero-order correlations in Table 2. Mean F0 was positively correlated with F0-SD (r = .56, p < .001). Df was positively associated to Pf (r = .31, p = .019) and HNR (r = .35, p = .008). Lastly, HNR was negatively correlated with jitter (r = −.57, p < .001). All these correlations are consistent with those reported in the literature (for F0 and F0-SD, see Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010; for Df and Pf, see the open data of Han et al., 2018; and for jitter and HNR, see de Krom, 1993), except the correlation between Df and HNR, which to our knowledge was not reported elsewhere.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Acoustic Characteristics of the Vocal Stimuli.

| Acoustic characteristics | Mean | SD | Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean F0 (Hz) | 114.47 | 11.84 | 85.44 to 140.07 |

| F0-SD (Hz) | 15.16 | 5.06 | 6.97 to 28.31 |

| Df (Hz) | 1,086.78 | 36.60 | 1,005 to 1,181 |

| Pf (Hz) | −1.61 | 0.47 | −2.47 to −0.65 |

| Harmonics-to-noise ratio (dB) | 11.32 | 1.37 | 7.93 to 14.94 |

| Jitter (%) | 2.68 | 0.47 | 1.83 to 4.41 |

| Intensity (dB) | 64.73 | 3.61 | 53.96 to 76.93 |

Note. n = 58.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations Between Each Acoustic Feature for the Vocal Stimuli.

| Acoustic characteristics | Mean F0 (Hz) | F0-SD (Hz) | Df (Hz) | Pf (Hz) | HNR (dB) | Jitter (%) | Intensity (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean F0 (Hz) | 1 | ||||||

| F0-SD (Hz) | 0.56*** | 1 | |||||

| Df (Hz) | −0.16 | −0.13 | 1 | ||||

| Pf (Hz) | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.31* | 1 | |||

| HNR (dB) | 0.13 | −0.24 | 0.35** | −0.06 | 1 | ||

| Jitter (%) | −0.15 | 0.20 | 0.13 | −0.14 | −0.57*** | 1 | |

| Intensity (dB) | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.22 | −0.08 | 1 |

Note. HNR = harmonics-to-noise ratio.

Significance code: *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Experimental Procedure

The experimental procedure was automated on an online computer-interfaced program. Two hundred twenty-four French female raters participated in a perceptual study after they self-reported in a questionnaire their age, origins of parents and grandparents (to control for potential cultural preferences), sexual orientation (to control for sexual preferences), and whether they suffered from a hearing impairment (note that other information were reported but are not used in the present study). After filling out the questionnaire, female raters were presented with a series of 11 choices each including a pair of voices. For each pair, two stimuli were randomly selected from the whole pool of vocal stimuli. The two vocal stimuli were randomized in their position presented in each pair (left or right position) on the computer screen. Judges were asked to choose the most attractive vocal stimulus by clicking on it. Participants were allowed to listen to the stimuli as much as they wanted. However, when the female judge made her choice, she could not go back to the previous one anymore. To measure intra-rater reliability, the second and third pairs were the same as the 10th and 11th pairs.

Although a forced choice paradigm is usually implemented with experimentally manipulated vocal stimuli (e.g., Jones et al., 2010; Re, O’Connor, Bennett, & Feinberg, 2012), there is fundamentally no advantage or disadvantage between a forced-choice paradigm and a correlational rating study for either manipulated or nonmanipulated stimuli. Crucially, it does not yield different results (e.g., for experimental designs, see Jones et al., 2010; Re et al., 2012; Vukovic et al., 2008; and for correlational designs, see Feinberg et al., 2005; Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010; Pisanski & Rendall, 2011).

We stopped collecting data when each voice of the 58 voices was heard at least 40 times in order to obtain statistically relevant data. In the end, the mean number of times a voice has been heard is M ± SD = 54.14 ± 6.55, with 72 and 42 times, respectively, for the most and least heard voices.

Of the 225 female participants who completed the questionnaire, 137 participants completed all 11 decisions, 28 participants skipped some of the decisions (mean number of skipped decisions = 8.75), for a total of 1,570 decisions in our analyses. Description of the judges’ characteristics that completed at least one pair (n = 165, M ± SD = 28.95 ± 14.16) are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Number of Judges for Each of the Following Categories: Those Who Completed the Full Test (i.e., Heard All the Pairs), Grandparents’ Ancestry, Sexual Orientation, and Hearing Impairments.

| Judges’ Categories | n |

|---|---|

| Completed the full test | |

| No | 28 |

| Yes | 137 |

| Ancestry | |

| European | 135 |

| Non-European | 30 |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 142 |

| Homosexual | 4 |

| Bisexual | 11 |

| Not reported | 8 |

| Hearing impairment | |

| No | 161 |

| Yes | 3 |

| Not reported | 1 |

Data Analysis

To analyze women’s preferences for men’s voices, a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) was used with the response variable being if the female judge chose or not the voice presented to her on the left position. The GLMM was fitted with a binomial error structure since the response variable consisted in a discrete probability distribution of the number of successes in a sequence of several independent trials. In order to explore acoustics’ preferences, seven predictor variables were computed and corresponded to the differences observed in mean F0, F0-SD, Df, Pf, HNR, jitter, and intensity between the two vocal stimuli (numerical variables that were standardized). Judges’ age (standardized variable), ancestry (i.e., European or non-European grandparents’), and sexual orientation (i.e., heterosexual and nonheterosexual) were added as control variables and put in interaction with the differences in acoustics' characteristics to assess their influence on voice preferences. Judges’ identities and the vocal stimuli were added as random effects as intercepts only. A symbolic representation of the GLMM is given in the Supplementary Material.

GLMMs with and without the control variables were performed to explore any statistical differences. Moreover, we performed two additional GLMMs, one without individuals with hearing impairment and one without individuals who did not report sexual orientation (these individuals were treated as nonheterosexual in the main GLMM). The significance of each predictor in all GLMMs was assessed from the comparison of the model excluding the predictor with the model including all the other predictors (i.e., likelihood-ratio χ2 tests, analysis of variance type III). Additionally, since some acoustic variables are highly correlated (see Table 2), we conducted multicollinearity checks on the GLMMs using the variation inflation factors (VIFs).

All statistical analyses were performed under the R software (Version 3.4.0), using the following packages: “lme4” to build the generalized linear models with random effects (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2014), “car” to compute the statistical significance of each predictor and check potential multicollinearity problems for the GLMMs (Fox, Weisberg, & Fox, 2011), and “MuMIn” to compute the pseudo-R2 (Bartoń, 2018). In order to illustrate the results with figures, we used “boot” to transform the coefficients of the GLMMs back into probabilities (Canty & Ripley, 2012), “dplyr” to compute the predictions of the model (Wickham, François, Henry, & Müller, 2018), and “ggplot2” for the resulting figures (Wickham, 2009).

Results

Descriptive statistics of the mean difference in acoustic features are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics for the Unstandardized Mean Difference for Each Acoustic Feature Summarized Over the Total Number of Observations.

| Unstandardized Mean Difference | Mean | SD | Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in mean F0 | −0.38 | 16.70 | −53.28 to 49.84 |

| Difference in F0-SD | −0.066 | 6.89 | −20.79 to 20.43 |

| Difference in Df | 1.25 | 51.73 | −176.66 to 176.66 |

| Difference in Pf | 0.003 | 0.66 | −1.81 to 1.81 |

| Difference in harmonics-to-noise ratio | −0.0086 | 1.91 | −5.73 to 5.58 |

| Difference in jitter | 0.013 | 0.64 | −2.58 to 2.58 |

| Difference in intensity | 0.065 | 5.06 | −20.63 to 22.97 |

Note. n = 1,570.

We computed THE intra-rater reliability scores by calculating the proportion of identical chosen vocal stimuli between the second and third first pairs with the 10th and 11th pairs. Intra-rater reliability was high: M ± SD = 0.791 ± 0.257, that is, judges considered on average more than two third the same voices as attractive.

Results of the main GLMM are reported in Table 5. VIFs were all inferior to 4, indicating no problems of multicollinearity. When presented with two voices, women preferred lower F0 ( = 24.89, p < .001), higher F0-SD profiles ( = 34.00, p < .001), and louder stimuli ( = 7.52, p = .006).

Table 5.

Results of the Generalized Linear Mixed Model Predicting Women’s Preferences for Men’s Voices.

| Estimate | SE | χ2 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | .09 | .06 | / | / |

| Difference in mean F0 | −.49 | .10 | 24.89 | <.001 |

| Difference in F0-SD | .53 | .09 | 34.00 | <.001 |

| Difference in Df | .18 | .10 | 3.26 | .070 |

| Difference in Pf | −.06 | .08 | 0.56 | .452 |

| Difference in HNR | −.12 | .10 | 1.23 | .266 |

| Difference in jitter | −.04 | .09 | 0.27 | .602 |

| Difference in intensity | .18 | .06 | 7.52 | .006 |

| Interactions with age | ||||

| Difference in F0 | .16 | .09 | 2.86 | .090 |

| Difference in F0-SD | .04 | .09 | 0.25 | .616 |

| Difference in Df | .13 | .09 | 2.06 | .151 |

| Difference in Pf | −.06 | .07 | 0.70 | .399 |

| Difference in HNR | −.11 | .09 | 1.31 | .251 |

| Difference in jitter | .10 | .08 | 1.61 | .204 |

| Difference in intensity | .15 | .06 | 5.65 | .017 |

| Interactions with ancestry | ||||

| Difference in F0 | −.008 | .22 | 0.001 | .968 |

| Difference in F0-SD | −.41 | .20 | 3.97 | .046 |

| Difference in Df | .04 | .23 | 0.03 | .863 |

| Difference in Pf | −.17 | .18 | 0.82 | .364 |

| Difference in HNR | −.01 | .25 | 0.003 | .953 |

| Difference in jitter | .06 | .21 | 0.09 | .752 |

| Difference in intensity | −.10 | .17 | 0.37 | .539 |

| Interactions with sexual orientation | ||||

| Difference in F0 | .15 | .24 | 0.38 | .534 |

| Difference in F0-SD | −.54 | .23 | 5.49 | .019 |

| Difference in Df | −.14 | .23 | 0.36 | .544 |

| Difference in Pf | −.10 | .18 | 0.28 | .593 |

| Difference in HNR | −.11 | .28 | 0.15 | .691 |

| Difference in jitter | .18 | .24 | 0.60 | .436 |

| Difference in intensity | .27 | .18 | 2.29 | .130 |

Note. Nstimuli = 58, Njudges = 165, and Nobservations = 1,570. For each variable, the χ2 and the p values associated from the likelihood-ratio χ2 test of the comparison between the full model and the model without the predictors and the control variables are given (analysis of variance type III). For the categorical variables’ “ancestry” and “sexual orientation,” the estimates are given compared to the reference category (1 = European ancestry and 1 = heterosexual). p Values are considered significant at the .05 threshold (in boldface). The degrees of freedom is 1 for every test. SD = standard deviation; SE = standard error; HNR = harmonics-to-noise ratio.

For easier understanding of the model’s output, the predicted probabilities of considering a voice more attractive than the other within the same pair were plotted against the range of differences in mean F0, F0-SD, and intensity between the two voices (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Probabilities of being picked as more attractive plotted against the standardized differences between the two voices heard in (a) mean F0, (b) F0-SD, and (c) intensity. The black curves represent the model’s predictions associated with 95% confidence intervals (in gray).

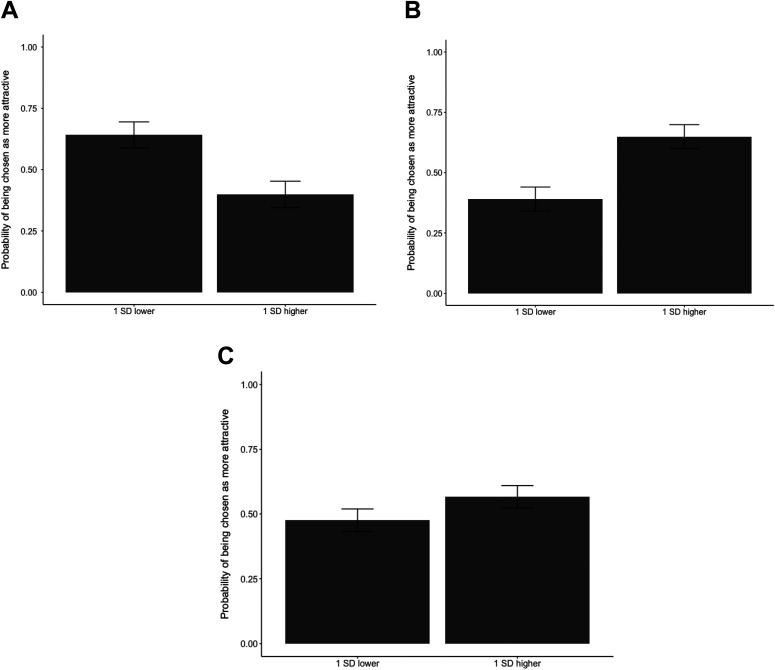

We also computed the predicted probability that a voice would be considered more attractive when it is 1 standard deviation lower and 1 standard deviation higher than the opposite one on the basis of their F0, F0-SD, and intensity (Figure 2). A voice with a mean F0 that is 1 standard deviation lower than the other in the same pair has a probability of being picked as more attractive up to ∼65%; likewise, a voice with a F0-SD which is 1 standard deviation higher has a probability of being picked as more attractive up to ∼65%.

Figure 2.

Barplots of the predicted probabilities that a voice would be considered more attractive when it is 1 standard deviation lower and 1 standard deviation higher than the other voice, as a function of its (a) mean F0, (b) F0-SD, and (c) intensity. Bars are associated with 95% confidence intervals.

Additionally, female judges did not show directional preferences for Df, Pf, HNR, or jitter (all p values > .05). Judges’ age had a significant influence on their preferences for intensity ( = 7.52, p = .006), that is, relatively older women preferred louder vocal profiles. Women with non-European ancestry and nonheterosexual women showed a preference for lower F0-SD profiles (respectively, = 3.97, p = .046; = 5.49, p = .019). The model explained 12% of the variance in vocal preferences, including fixed and random effects. Lastly, the variance of the random intercept for judges was higher than the vocal stimuli (σjudges = 0.07, σstimuli = 0.01).

The model without ancestry and the one without sexual orientation were not statistically different from the full model (respectively, = 10.42, p = .165; = 9.96, p = .190). Removing age from the model was statistically different from the full model ( = 18.74, p = .009). The models without judges with hearing impairment and without judges who did not report sexual orientation did not qualitatively change the results. In all models, the main results remained the same: Female judges still considered voices with lower F0, higher F0-SD, and higher intensity as more attractive. All models without the control variables are given in the Supplementary Material.

Discussion

Women significantly preferred lower vocal pitch in men. This result is consistent with previous findings in English-speaking populations (Feinberg et al., 2005; Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2010; Pisanski & Rendall, 2011; Vukovic et al., 2008) and several other languages (Bruckert et al., 2006; Skrinda et al., 2014; Valentová et al., 2013; Weiss & Burkhardt, 2010). Moreover, this finding has been replicated with a similar or higher number of stimuli and judges than most of these studies (see Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010, for an example of a study with a higher number of stimuli). As vocal height correlates to several biological and social information about men, such as testosterone levels (Dabbs & Mallinger, 1999; Evans et al., 2008; Hodges-Simeon et al., 2015), sexually related behaviors (Hughes et al., 2004), body size assessments (Pisanski et al., 2014a), and signaling social dominance (Puts et al., 2007) and social rankings (Cheng, Tracy, Ho, & Henrich, 2016), women may rely on this salient acoustic cue as an assessment of sexual partner quality. Several studies have reported that men exhibiting relatively low-pitched voices reported a higher mating success in industrialized societies (Hodges-Simeon, Gaulin, & Puts, 2011; Puts, 2005; Puts et al., 2006; although see Suire et al., 2018) and a higher reproductive success in a hunter-gatherer society (Apicella, Feinberg, & Marlowe, 2007; although see Smith, Olkhov, Puts, & Apicella, 2017).

Moreover, French women also significantly preferred higher F0-SD profiles in men, that is, more expressive (or less monotonous) voices. Although our study had a higher number of judges and stimuli than the two others that reported the same relationship (Bruckert et al., 2006; Leongómez et al., 2014), another study had a higher number of stimuli but less judges (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010). Nonetheless, while self-confidence and experience can be expressed through monotonous voices, to which some women may be more attracted to (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010), our results do not follow the same tendency. A possible explanation may be that more marked intonation patterns might be perceived as more attractive as it is a marker of perceived state-dependent qualities such as positive emotions (e.g., joy and happiness; Banse & Scherer, 1996), conversational interest, and emotional activation (i.e., arousal) and intensity (Laukka, Juslin, & Bresin, 2005). Ultimately, expressive voices could reflect the speaker’s current mental-health state since it has been previously reported that clinically depressed patients show typically reduced F0-SD values (Ellgring & Scherer, 1996). Thus, higher F0 variability may be associated to more enthusiastic and extroverted individuals, to which women may be more attracted. In this sense, our result is consistent with previous findings in both men and women (Bruckert et al., 2006; Leongómez et al., 2014). Although it has been suggested to be a cue of femininity, as women display twice as much F0 variation, we suggest that irrespective of sex, higher F0-SD profiles should be perceived as more attractive.

No directional preferences were observed for the formants’ dispersion and position, which corroborates some previous findings (Babel et al., 2014; Feinberg et al., 2005), using a higher or similar number of stimuli and a higher number of judges. Several studies have suggested that Df may be a more important vocal cue to assess in human competitive settings. Indeed, it has been reported that lower Df patterns were associated to perceived dominance in men (Puts et al., 2007; Wolff & Puts, 2010). This can be explained by the fact that lower Df patterns are associated to larger body size (Pisanski et al., 2016) and to perceived larger individuals (Bruckert et al., 2006; Collins, 2000; Rendall et al., 2007). Interestingly, females were also found to be more sensitive to this vocal cue than men after hearing women’s voices (Puts, Barndt, Welling, Dawood, & Burriss, 2011). Such results emphasize the idea that same-sex individuals may use Df to track competitor’s masculinity and/or femininity. Similarly, some research suggest that the formants’ position may signal threat potential among men (Puts et al., 2012), although a recent study found no correlation to physical strength (Han et al., 2018).

Our results also indicated that vocal breathiness and roughness (assessed, respectively, through the HNR and the jitter ratio's) did not significantly contribute to men’s vocal attractiveness, using a higher number of stimuli and judges than previous studies (Babel et al., 2014; Hughes et al., 2008, 2014). Although one study reported that breathier voices were found to be more attractive in Namibian men, ours did not (Šebesta et al., 2017). Another study found that perceived “breathy” voices were significantly more attractive in both sexes (Xu et al., 2013), although the underlying acoustic component was not clearly identified in this study. Lack of significant findings for breathiness suggests that it is more associated with feminine vocal quality as previously suggested (Henton & Bladon, 1985; Van Borsel et al., 2009). It is also possible that when assessing attractiveness, women may be particularly attuned to the vocal features that are indicative of one’s heritable mate quality, such as the F0. In this context, breathiness and roughness may not reliably indicate mate or competitor quality for listeners, at least in men. Although they are correlated to other body features (see Pisanski et al., 2016, for an extensive study on that matter), further studies are needed to understand whether these two acoustic components of the human voice are perceptually salient in influencing vocal attractiveness. Otherwise, it has been suggested that HNR and jitter may be indicative of current hormonal profiles as both parameters relate to the oscillations of the vocal folds, which possess many cellular receptors to androgens (Pisanski et al., 2016).

An important limitation to the current study is that we did not investigate the effects of women’s menstrual cycle upon perceived vocal attractiveness. Indeed, there was more variations between females judges than between vocal stimuli (σjudges = 0.07, σstimuli = 0.01), suggesting, for example, that the timing of the ovulatory cycle may play a role. In fact, it has been long suggested that menstrual phase and mating contexts may influence women’s preferences for masculine vocal attributes (Feinberg et al., 2006; Pisanski et al., 2014c; Puts, 2005). Under the “good genes ovulatory shift hypothesis,” women in their fertile phase are predicted to shift their preferences toward mates indicating high genetic quality (i.e., more masculine men, to which women may be particularly attracted to for a short-term relationship, such as a one-night stand), as opposed to mates indicating high parental investment in their nonfertile phase (i.e., less masculine men, to which women may be particularly attracted to for a long-term, committed, and romantic relationship; Jünger, Kordsmeyer, Gerlach, & Penke, 2018). These shifting preferences have been suggested to be an adaptive strategy in order to maximize fitness benefits for women.

For instance, Puts (2005) found that females judged lowered pitch voices more attractive than the same voices raised in pitch in their fertile phase of their ovulatory cycle with respect to a short-term context. Similarly, Feinberg et al. (2006) found that women’s masculinity preferences for low-pitched voices were stronger during the fertile phase. Although the effect was not significant, Pisanski et al. (2014c) also reported stronger preferences for masculinized voice pitch. Lastly, one study has reported that women in their fertile phase significantly preferred lowered Df when questioned for both short- and long-term relationships (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010). The authors also found that mean F0 and attractiveness was strongest for fertile-phase women rating short-term attractiveness, while F0-SD was more attractive for nonfertile phase female rating short-term attractiveness and fertile females rating long-term attractiveness. However, recent evidence has suggested that women menstrual cycle does not influence their preferences for masculinized bodies and faces (Jones et al., 2018; Marcinkowska, Galbarczyk, & Jasienska, 2018). Using a large sample size and a more methodologically grounded procedure, Jünger, Motta-Mena, et al. (2018) found no effect of the cycle phase, conception risk, and steroid hormone levels on women’s auditory preferences for men’s voices. Further research is thus needed to reliably investigate if the menstrual cycle has a significant effect over shifted preferences. In any case, not controlling for this factor will only provide conservative results, under the hypothesis that the time of the menstrual cycle is randomly distributed among the participating women.

Other limitations include the difference in age between men who provided the vocal stimuli and the female judges. However, in our sample, both the youngest individual who provided the vocal stimuli and the youngest female judge were aged 18, which is largely above the age where mate preferences develop and become relevant (age 13–15, Saxton, Caryl, & Craig Roberts, 2006; Saxton et al., 2009). Moreover, an interesting perspective for future research would be to investigate possible nonlinear effects of preferences as a function of vocal parameters. Indeed, extreme values for a particular vocal parameter may be perceived as pathological (as it is the case for high values of jitter and low values of HNR; Teixeira et al., 2013) or perceived as immature and/or too feminine (e.g., high F0). To our knowledge, only one study has tackled this topic in women’s preferences for men’s F0, and it was found that women did not prefer vocal pitches below the ∼96 Hz threshold. This suggests that preferences may contribute to stabilizing selection pressure for low pitch in men’s voices (Re et al., 2012). Interestingly, in men’s preferences for the F0 of women, one study reported a nonlinear relationship with attractiveness ratings starting to decrease when the F0 is higher than ∼260 Hz (Borkowska & Pawlowski, 2011), although two studies have reported that there was no upper limit (Feinberg, DeBruine, Jones, & Perrett, 2008; Re et al., 2012).

Conclusions

The current study adds to the body of literature on vocal attractiveness in an underrepresented language (i.e., French). Although voice pitch findings were replicated, confirming women’s preferences for low-pitched masculine voices, most of the other acoustic features investigated in this study did not yield to significant results, leading us to conclude that variations in resonant frequencies’ spacing, breathiness, and roughness do not seem to be important contributors of men’s vocal attractiveness, at least in a French-speaking sample. Further studies should explore these relationships in other cultures so as to reaffirm these findings.

Supplemental Material

Supplementary_Material for Male Vocal Quality and Its Relation to Females’ Preferences by Alexandre Suire, Michel Raymond and Melissa Barkat-Defradas in Evolutionary Psychology

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The data and the R code from this study can be found at https://figshare.com/s/cab62d1e411503982c91

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Alexandre Suire  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1852-3083

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1852-3083

Michel Raymond  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1714-6984

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1714-6984

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Abitbol J., Abitbol P., Abitbol B. (1999). Sex hormones and the female voice. Journal of Voice, 13, 424–446. doi:10.1016/S0892-1997(99)80048-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akcam T., Bolu E., Merati A. L., Durmus C., Gerek M., Ozkaptan Y. (2004). Voice changes after androgen therapy for hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism. The Laryngoscope, 114, 1587–1591. doi:10.1097/00005537-200409000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apicella C. L., Feinberg D. R. (2009). Voice pitch alters mate-choice-relevant perception in hunter-gatherers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 276, 1077–1082. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apicella C. L., Feinberg D. R., Marlowe F. W. (2007). Voice pitch predicts reproductive success in male hunter-gatherers. Biology Letters, 3, 682–684. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnocky S., Hodges-Simeon C. R., Ouellette D., Albert G. (2018). Do men with more masculine voices have better immunocompetence? Evolution and Human Behavior, 36, 602–610. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.06.003 [Google Scholar]

- Babel M., McGuire G., King J. (2014). Towards a more nuanced view of vocal attractiveness. PLoS One, 9, e88616. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachorowski J. A., Owren M. J. (1999). Acoustic correlates of talker sex and individual talker identity are present in a short vowel segment produced in running speech. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 106, 1054–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banse R., Scherer K. R. (1996). Acoustic profiles in vocal emotion expression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoń K. (2018). MuMIn : Multi-model inference. R package version 1.42.1. Retrieved fromhttps://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. (2014). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. ArXiv:1406.5823 [Stat]. Retrieved fromhttp://arxiv.org/abs/1406.5823

- Boersma P., Weenink D. (2017). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [Computer software]. Version 6.0.33. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckert L., Lienard J.-S., Lacroix A., Kreutzer M., Leboucher G. (2006). Women use voice parameters to assess men’s characteristics. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273, 83–89. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkowska B., Pawlowski B. (2011). Female voice frequency in the context of dominance and attractiveness perception. Animal Behaviour, 82, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Canty A., Ripley B. (2019). boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions. R package version 1.3-23. Retrieved fromhttps://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/boot/boot.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J. T., Tracy J. L., Ho S., Henrich J. (2016). Listen, follow me: Dynamic vocal signals of dominance predict emergent social rank in humans. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145, 536–547. doi:10.1037/xge0000166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. A. (2000). Men’s voices and women’s choices. Animal Behaviour, 60, 773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbs J. M., Mallinger A. (1999). High testosterone levels predict low voice pitch among men. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 801–804. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00272-4 [Google Scholar]

- de Krom G. D. (1993). A cepstrum-based technique for determining a harmonics-to-noise ratio in speech signals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 36, 254–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgring H., Scherer K. R. (1996). Vocal indicators of mood change in depression. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 20, 83–110. doi:10.1007/BF02253071 [Google Scholar]

- Evans S., Neave N., Wakelin D., Hamilton C. (2008). The relationship between testosterone and vocal frequencies in human males. Physiology & Behavior, 93, 783–788. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg D. R., DeBruine L. M., Jones B. C., Perrett D. I. (2008). The role of femininity and averageness of voice pitch in aesthetic judgments of women’s voices. Perception, 37, 615–623. doi:10.1068/p5514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg D. R., Jones B. C., Armstrong M. M. (2019). No evidence that men’s voice pitch signals formidability. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 190–192. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg D. R., Jones B. C., Law Smith M. J., Moore F. R., DeBruine L. M., Cornwell R. E.…Perrett D. I. (2006). Menstrual cycle, trait estrogen level, and masculinity preferences in the human voice. Hormones and Behavior, 49, 215–222. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg D. R., Jones B. C., Little A. C., Burt D. M., Perrett D. I. (2005). Manipulations of fundamental and formant frequencies influence the attractiveness of human male voices. Animal Behaviour, 69, 561–568. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.06.012 [Google Scholar]

- Fitch W. T. (1997). Vocal tract length and formant frequency dispersion correlate with body size in rhesus macaques. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 102, 1213–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstad I., Karter A. J. (1992). Parasites, bright males, and the immunocompetence handicap. The America Naturalist, 139, 603–622. [Google Scholar]

- Foo Y. Z., Nakagawa S., Rhodes G., Simmons L. W. (2017). The effects of sex hormones on immune function: A meta-analysis: Sex hormones and immune function. Biological Reviews, 92, 551–571. doi:10.1111/brv.12243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet M., Pisanski K., Mathevon N., Reby D. (2016). Seven and up: Individual differences in male voice fundamental frequency emerge before puberty and remain stable throughout adulthood. Royal Society Open Science, 3, 160395. doi:10.1098/rsos.160395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Weisberg S., Fox J. (2011). An R companion to applied regression (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfer M. P., Bennett Q. E. (2013). Speaking fundamental frequency and vowel formant frequencies: Effects on perception of gender. Journal of Voice, 27, 556–566. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2012.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfer M. P., Mikos V. A. (2005). The relative contributions of speaking fundamental frequency and formant frequencies to gender identification based on isolated vowels. Journal of Voice, 19, 544–554. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Wang H., Fasolt V., Hahn A., Holzleitner I. J., Lao J.…Jones B. (2018). No clear evidence for correlations between handgrip strength and sexually dimorphic acoustic properties of voices. American Journal of Human Biology, 30, e23178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henton C. G., Bladon R. A. (1985). Breathiness in normal female speech: Inefficiency versus desirability. Language & Communication, 5, 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand J. M. (1988). Perception of aperiodicities in synthetically generated voices. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 83, 2361–2371. doi:10.1121/1.396367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand J. M., Clark M. J. (2009). The role of f0 and formant frequencies in distinguishing the voices of men and women. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 71, 1150–1166. doi:10.3758/APP.71.5.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges-Simeon C. R., Gaulin S. J. C., Puts D. A. (2010). Different vocal parameters predict perceptions of dominance and attractiveness. Human Nature, 21, 406–427. doi:10.1007/s12110-010-9101-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges-Simeon C. R., Gaulin S. J. C., Puts D. A. (2011). Voice correlates of mating success in men: Examining “contests” versus “mate choice” modes of sexual selection. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 551–557. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9625-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges-Simeon C. R., Gurven M., Gaulin S. J. C. (2015). The low male voice is a costly signal of phenotypic quality among Bolivian adolescents. Evolution and Human Behavior, 36, 294–302. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.01.002 [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S. M., Dispenza F., Gallup G. G. (2004). Ratings of voice attractiveness predict sexual behavior and body configuration. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25, 295–304. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.06.001 [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S. M., Farley S. D., Rhodes B. C. (2010). Vocal and physiological changes in response to the physical attractiveness of conversational partners. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 34, 155–167. doi:10.1007/s10919-010-0087-9 [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S. M., Mogilski J. K., Harrison M. A. (2014). The perception and parameters of intentional voice manipulation. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 38, 107–127. doi:10.1007/s10919-013-0163-z [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S. M., Pastizzo M. J., Gallup G. G. (2008). The sound of symmetry revisited: Subjective and objective analyses of voice. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 32, 93–108. doi:10.1007/s10919-007-0042-6 [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. C., Feinberg D. R., DeBruine L. M., Little A. C., Vukovic J. (2010). A domain-specific opposite-sex bias in human preferences for manipulated voice pitch. Animal Behaviour, 79, 57–62. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.10.003 [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. C., Hahn A. C., Fisher C. I., Wang H., Kandrik M., Han C.…O’Shea K. J. (2018). No compelling evidence that preferences for facial masculinity track changes in women’s hormonal status. Psychological science, 29, 996–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. M., Trabold M., Plante F., Cheetham B. M. G., Earis J. E. (2001). Objective assessment of hoarseness by measuring jitter. Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences, 26, 29–32. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2273.2001.00413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost L., Fuchs M., Loeffler M., Thiery J., Kratzsch J., Berger T., Engel C. (2018). Associations of sex hormones and anthropometry with the speaking voice profile in the adult general population. Journal of Voice, 32, 261–272. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jünger J., Kordsmeyer T. L., Gerlach T. M., Penke L. (2018). Fertile women evaluate male bodies as more attractive, regardless of masculinity. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39, 412–423. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.03.007 [Google Scholar]

- Jünger J., Motta-Mena N. V., Cardenas R., Bailey D., Rosenfield K. A., Schild C.…Puts D. A. (2018). Do women’s preferences for masculine voices shift across the ovulatory cycle? Hormones and Behavior, 106, 122–134. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukka P., Juslin P., Bresin R. (2005). A dimensional approach to vocal expression of emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 19, 633–653. doi:10.1080/02699930441000445 [Google Scholar]

- Leongómez J. D., Binter J., Kubicová L., Stolařová P., Klapilová K., Havlíček J., Roberts S. C. (2014). Vocal modulation during courtship increases proceptivity even in naive listeners. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35, 489–496. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.06.008 [Google Scholar]

- Linville S. E., Fisher H. B. (1985). Acoustic characteristics of perceived versus actual vocal age in controlled phonation by adult females. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 78, 40–48. doi:10.1121/1.392452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons M., Lynch A., Brewer G., Bruno D. (2014). Detection of sexual orientation (“Gaydar”) by homosexual and heterosexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 345–352. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0144-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkowska U. M., Galbarczyk A., Jasienska G. (2018). La donna è mobile? Lack of cyclical shifts in facial symmetry, and facial and body masculinity preferences—A hormone based study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 88, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson B., McDonald E. C., DeBoe N. L., White A. R. (2006). The acoustic and perceptual bases of judgments of women and men’s sexual orientation from read speech. Journal of Phonetics, 34, 202–240. doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2005.05.003 [Google Scholar]

- Pisanski K., Fraccaro P. J., Tigue C. C., O’Connor J. J. M., Feinberg D. R. (2014. a). Return to Oz: Voice pitch facilitates assessments of men’s body size. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 40, 1316–1331. doi:10.1037/a0036956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisanski K., Fraccaro P. J., Tigue C. C., O’Connor J. J. M., Röder S., Andrews P. W.…Feinberg D. R. (2014. b). Vocal indicators of body size in men and women: A meta-analysis. Animal Behaviour, 95, 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.06.011 [Google Scholar]

- Pisanski K., Hahn A. C., Fisher C. I., DeBruine L. M., Feinberg D. R., Jones B. C. (2014. c). Changes in salivary estradiol predict changes in women’s preferences for vocal masculinity. Hormones and Behavior, 66, 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisanski K., Jones B. C., Fink B., O’Connor J. J. M., DeBruine L. M., Röder S., Feinberg D. R. (2016). Voice parameters predict sex-specific body morphology in men and women. Animal Behaviour, 112, 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.11.008 [Google Scholar]

- Pisanski K., Rendall D. (2011). The prioritization of voice fundamental frequency or formants in listeners’ assessments of speaker size, masculinity, and attractiveness. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 129, 2201–2212. doi:10.1121/1.3552866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek P. H., Sander E. K. (1966). Age recognition from voice. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 9, 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A. (2005). Mating context and menstrual phase affect women’s preferences for male voice pitch. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 388–397. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.03.001 [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A., Apicella C. L., Cardenas R. A. (2012). Masculine voices signal men’s threat potential in forager and industrial societies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279, 601–609. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A., Aung T. (2019). Does men’s voice pitch signal formidability? A reply to Feinberg et al. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 189–190. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A., Barndt J. L., Welling L. L. M., Dawood K., Burriss R. P. (2011). Intrasexual competition among women: Vocal femininity affects perceptions of attractiveness and flirtatiousness. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 111–115. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.011 [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A., Gaulin S. J. C., Verdolini K. (2006). Dominance and the evolution of sexual dimorphism in human voice pitch. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 283–296. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.11.003 [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A., Hodges C. R., Cárdenas R. A., Gaulin S. J. C. (2007). Men’s voices as dominance signals: Vocal fundamental and formant frequencies influence dominance attributions among men. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 340–344. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.05.002 [Google Scholar]

- Rabinov C. R., Kreiman J., Gerratt B. R., Bielamowicz S. (1995). Comparing reliability of perceptual ratings of roughness and acoustic measures of jitter. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 38, 26. doi:10.1044/jshr.3801.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re D. E., O’Connor J. J. M., Bennett P. J., Feinberg D. R. (2012). Preferences for very low and very high voice pitch in humans. PLoS One, 7, e32719. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendall D., Vokey J. R., Nemeth C. (2007). Lifting the curtain on the Wizard of Oz: Biased voice-based impressions of speaker size. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 33, 1208–1219. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.33.5.1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton T. K., Caryl P. G., Craig Roberts S. (2006). Vocal and facial attractiveness judgments of children, adolescents and adults: The ontogeny of mate choice. Ethology, 112, 1179–1185. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01278.x [Google Scholar]

- Saxton T. K., Debruine L. M., Jones B. C., Little A. C., Roberts S. C. (2009). Face and voice attractiveness judgments change during adolescence. Evolution and Human Behavior, 30, 398–408. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.06.004 [Google Scholar]

- Šebesta P., Kleisner K., Tureček P., Kočnar T., Akoko R. M., Třebický V., Havlíček J. (2017). Voices of Africa: Acoustic predictors of human male vocal attractiveness. Animal Behaviour, 127, 205–211. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.03.014 [Google Scholar]

- Sell A., Bryant G. A., Cosmides L., Tooby J., Sznycer D., von Rueden C.…Gurven M. (2010). Adaptations in humans for assessing physical strength from the voice. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277, 3509–3518. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipp T., Qi Y., Huntley R., Hollien H. (1992). Acoustic and temporal correlates of perceived age. Journal of Voice, 6, 211–216. doi:10.1016/S0892-1997(05)80145-6 [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi T. N., Puts D. A., Escasa-Dorne M. J. (2018). Filipino women’s preferences for male voice pitch: Intra-individual, life history, and hormonal predictors. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 4, 188–206. doi:10.1007/s40750-018-0087-2 [Google Scholar]

- Simmons L. W., Peters M., Rhodes G. (2011). Low pitched voices are perceived as masculine and attractive but do they predict semen quality in men? PLoS One, 6, e29271. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrinda I., Krama T., Kecko S., Moore F. R., Kaasik A., Meija L.…Krams I. (2014). Body height, immunity, facial and vocal attractiveness in young men. Naturwissenschaften, 101, 1017–1025. doi:10.1007/s00114-014-1241-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. M., Olkhov Y. M., Puts D. A., Apicella C. L. (2017). Hadza men with lower voice pitch have a better hunting reputation. Evolutionary Psychology, 15. doi:10.1177/1474704917740466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suire A., Raymond M., Barkat-Defradas M. (2018). Human vocal behavior within competitive and courtship contexts and its relation to mating success. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39, 684–691. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.07.001 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. M., Reby D. (2010). The contribution of source-filter theory to mammal vocal communication research: Advances in vocal communication research. Journal of Zoology, 280, 221–236. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00661.x [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira J. P., Oliveira C., Lopes C. (2013). Vocal acoustic analysis—Jitter, Shimmer and HNR parameters. Procedia Technology, 9, 1112–1122. doi:10.1016/j.protcy.2013.12.124 [Google Scholar]

- Titze I. R. (1989). Physiologic and acoustic differences between male and female voices. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 85, 1699–1707. doi:10.1121/1.397959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentová J., Roberts S. C., Havlíček J. (2013). Preferences for facial and vocal masculinity in homosexual men: The role of relationship status, sexual restrictiveness, and self-perceived masculinity. Perception, 42, 187–197. doi:10.1068/p6909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Borsel J., Janssens J., De Bodt M. (2009). Breathiness as a feminine voice characteristic: A perceptual approach. Journal of Voice, 23, 291–294. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vukovic J., Feinberg D. R., Jones B. C., DeBruine L. M., Welling L. L. M., Little A. C., Smith F. G. (2008). Self-rated attractiveness predicts individual differences in women’s preferences for masculine men’s voices. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 451–456. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.05.013 [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B., Burkhardt F. (2010). Voice attributes affecting likability perception. Proceedings of the 11th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, INTERSPEECH 2010. 2014–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wendahl R. W. (1966). Some parameters of auditory roughness. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 18, 26–32. doi:10.1159/000263081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. (2009). Ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H., François R., Henry L., Müller K. (2018). Dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation (R package version 0.7.8). Retrieved fromhttps://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr

- Wolff S. E., Puts D. A. (2010). Vocal masculinity is a robust dominance signal in men. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 64, 1673–1683. doi:10.1007/s00265-010-0981-5 [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Lee A., Wu W.-L., Liu X., Birkholz P. (2013). Human vocal attractiveness as signaled by body size projection. PLoS One, 8, e62397. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary_Material for Male Vocal Quality and Its Relation to Females’ Preferences by Alexandre Suire, Michel Raymond and Melissa Barkat-Defradas in Evolutionary Psychology