Abstract

Background

Stable isotope techniques using 13C to assess vitamin A (VA) dietary sources, absorption, and total body VA stores (TBSs) require determination of baseline 13C abundance. 13C-natural abundance is approximately 1.1% total carbon, but varies with foods consumed, supplements taken, and food fortification with synthetic retinyl palmitate.

Objectives

We determined 13C variation from purified serum retinol and the resulting impact on TBSs using pooled data from preschool children in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zambia and Zambian women.

Methods

Seven studies included children (n = 639; 56 ± 25 mo; 48% female) and one in women (n = 138; 29 ± 8.5 y). Serum retinol 13C-natural abundance was determined using GC-C-IRMS. TBSs were available in 7 studies that employed retinol isotope dilution (RID). Serum CRP and α1-acid-glycoprotein (AGP) were available from 6 studies in children. Multivariate mixed models assessed the impact of covariates on retinol 13C. Spearman correlations and Bland–Altman analysis compared serum and milk retinol 13C and evaluated the impact of using study- or global-retinol 13C estimates on calculated TBSs.

Results

13C-natural abundance (%, median [Q1, Q3]) differed among countries (low: Zambia, 1.0744 [1.0736, 1.0753]; high: South Africa, 1.0773 [1.0769, 1.0779]) and was associated with TBSs, CRP, and AGP in children and with TBSs in women. 13C-enrichment from serum and milk retinol were correlated (r = 0.52; P = 0.0001). RID in children and women using study and global estimates had low mean bias (range, −3.7% to 2.2%), but larger 95% limits of agreement (range, −23% to 37%).

Conclusions

13C-natural abundance is different among human cohorts in Africa. Collecting this information in subgroups is recommended for surveys using RID. When TBSs are needed on individuals in clinical applications, baseline 13C measures are important and should be measured in all enrolled subjects.

Keywords: African countries, preschool children, retinol isotope dilution, stable isotope, vitamin A

Introduction

Objective biomarkers of dietary intake and accurate nutritional status assessment are 2 goals of the US NIH strategic plan for realizing the vision of precision nutrition [1,2]. Critically, these biomarkers need to be accurate and accessible at the individual level rather than accurate only at the population level. Stable isotope-based assessment methods can be used to estimate relative dietary contributions, particularly across trophic levels [3,4]. Stable isotope tracers can also be used to assess nutrient absorption [5], metabolism, and total body content using the principle of isotope dilution [6].

Ratios of stable isotopes of nitrogen (15N) and carbon (13C) can be used to assess differences in intake of meat, fish, and plant-based foods [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. 13C makes up approximately 1.1% of all natural carbon, but in humans, it is highly dependent on the foods and supplements consumed. 13C is fractionated (separated) from 12C during specific biological processes, resulting in reduced or increased 13C enrichment that is specific to certain organisms or metabolic processes [12]. For example, there is a large difference between C3 and C4 plants, whereby C4 plants (e.g., maize, rice, sugarcane, and sorghum) fractionate less 13C, resulting in a higher 13C-natural enrichment within the plant than C3 plants (most vegetables consumed by humans). This difference can be exploited to predict added sugar or sugar-sweetened beverage intakes and evaluate interventions to change intakes of these foods [13,14]. Furthermore, nutrient-specific intakes can be traced, such as the nonprovitamin A carotenoid lutein [15] and biofortified provitamin A maize as a contribution to total vitamin A (VA) intakes using retinol 13C enrichments [16, 17].

Provitamin A carotenoids synthesized by C4 plants will also have a higher 13C enrichment than C3 plants, which is measurable in animals and humans consuming them as an increase in circulating retinol 13C-natural abundance. Based on the amount of shift in baseline 13C enrichment, the relative contribution of C4 provitamin A sources (e.g., biofortified maize) to the total VA intake can be determined [16,17]. This could be used to assess coverage of provitamin A interventions or to determine the contribution of biofortified maize to VA stores relative to other sources in effectiveness studies. Applications to indicate metabolite dietary origins require enough sensitivity, accuracy, and precision for 13C/12C determination. Isotope ratio MS has the advantage of high sensitivity and is commonly used when working with enrichments close to natural abundance.

In the application of 13C-retinol to assess VA status using retinol isotope dilution (RID), a baseline blood sample is required to assess the natural abundance of 13C in serum retinol. Some studies have eliminated the need for this baseline blood sample by obtaining a group level estimate from separate participants [18,19]. To attempt to optimize study designs and reduce the number of required blood samples, we performed a pooled analysis of 8 studies with VA 13C-natural abundance data from 6 African countries to provide estimates of within- and between-country variation.

Our primary objectives were to: 1) describe reference ranges and covariates of retinol 13C-natural abundance so they could be used to assess changes in dietary contributions from foods and supplements over time, and 2) compare RID-derived VA status using individual or population retinol 13C-natural abundance to inform RID study designs and population evaluations seeking to minimize blood sampling requirements. We hypothesized that 13C-natural abundance would differ within and among countries because of the diversity in plant and animal foods consumed, supplementation usage, and country-level fortification mandates.

Methods

Data sources

We conducted an analysis of available baseline data from 8 studies (total n = 781). Four outliers were excluded based on a retinol 13C-natural abundance >3 SDs from the mean: 3 from women in Zambia and 1 from a child in Ethiopia. Five studies among preschool children (n = 467) were part of a regional Technical Cooperation project supported predominantly by the International Atomic Energy Agency. Studies were conducted in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, South Africa [20], and Tanzania [21]. Two studies in Zambia were part of biofortification feeding trials in preschool children (n = 172) [22,23], and one additional study assessed VA status in Zambian lactating and nonlactating women (n = 138) [24]. Consistent exclusion criteria for the children were active fever >38 °C, severe anemia cutoff of <70 g/L (except in South Africa, which used a moderate anemia cutoff of <90 g/L), or severe wasting (weight-for-height z-score <−3). Pregnant women were excluded in Zambia.

Ethics

Each country was required to seek independent ethical approval and encouraged to register their trials. Individual study ethics committee approvals were reported in their respective publications [[21], [22], [23], [24]] and one combined analysis reporting on the remaining studies [25] (Supplementary Table 1). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all children enrolled or the women themselves.

Laboratory and biomarker analysis

HemoCue (Hb-301) was used to measure hemoglobin concentration using venous blood. CRP, α1-acid-glycoprotein (AGP), and RBP levels were analyzed using ELISA by either the VitMin Lab [26] or at the University of Wisconsin-Madison using commercially available kits (CRP: Cayman Chemical Company; AGP: Abcam; and RBP: Arbor Assays). Serum retinol was determined using HPLC and purified commercial standards (Sigma Aldrich). Serum retinol and milk VA 13C enrichment analysis was performed in the laboratory of SAT using GC-C-IRMS as published previously [23,25]. Total body VA stores (TBSs) and total liver VA reserves (TLRs) were determined using RID and the tracer-to-tracee ratio [23,27]. Assumptions used for calculating TBSs and TLRs are reported in their respective articles and include dose absorption, ratio between serum and liver enrichment, dose catabolism, liver to body weight ratio, and fraction of TBSs stored in liver.

Statistical methods

Data are reported as medians (Q1 and Q3) or as means ± SDs. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Nonnormal covariates (CRP and AGP) were natural log-transformed for analysis. Spearman correlations were determined among outcomes. Differences in 13C-natural enrichment among studies were determined with study as a fixed effect. Lactating and nonlactating women from the same study were treated as 2 separate groups. Multivariate models included age, sex, and other covariates as fixed effects and study as a random effect. Post hoc letter groupings among studies were determined using the macro PDMIXED with a Tukey adjustment [28]. TBSs and TLRs were calculated using the RID equation [29] with study-specific assumptions as reported by the authors. To evaluate the impact of using population estimates on 13C TBS calculations, each participant’s individual, within-study, and within-life stage (children and women) median retinol 13C-natural abundance was used to calculate separate TBS estimates, referred to as TBSindividual, TBSstudy, and TBSglobal, respectively. Resulting TLRs for 50% and 80% of TBSs in liver were calculated with the same RID assumptions (i.e., TLR_50sudy, TLR_50global, TLR_80study, and TLR_80global). Bland–Altman analysis was used for method comparisons: 1) serum compared with milk 13C-enrichment, and 2) TBSindividual and TLRindividual compared with their respective study and global estimates. Statistical significance was considered at P value of ≤0.05.

Results

Study inclusion and participant data

The 8 included studies contained 777 participants with data on serum retinol 13C-natural abundance. Of the 7 studies in children, 47.6% of participants were female and median ages ranged from 45.2 to 70.0 months (Table 1). Median VA TBSs ranged from 105 μmol in Ethiopia to 700 μmol in Zambia. From the study of women of reproductive age (range, 15–48 y), 54.4% were lactating at the time of sampling.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of children and women (n = 775) enrolled in studies in 6 countries1

| Burkina Faso | Cameroon | Ethiopia | South Africa | Tanzania | Zambia 2010 | Zambia 2012 | Zambia 2019 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlactating | Lactating | ||||||||

| n | 104 | 45 | 130 | 93 | 95 | 39 | 133 | 63 | 75 |

| Sex, female (%) | 46.2 | 53.3 | 44.6 | 54.8 | 47.4 | 46.2 | 45.1 | 100 | 100 |

| Age (mos) | 49.1 (42.8, 52.9) | 60.0 (48.0, 60.0) | 48.0 (41.0, 54.0) | 45.2 (39.2, 52.4) | 47.8 (41.2, 53.3) | 54.5 (46.0, 60.0) | 70.0 (66.0, 77.0) | 360 (276, 456) | 336 (270, 396) |

| Weight (kg) | 14.7 (13.6, 16.1) | 17.0 (15.0, 19.0) | 14.0 (12.7, 15.4) | 13.4 (12.2, 14.8) | 14.4 (13.4, 15.7) | 14.3 (13.3, 16.2) | 16.9 (15.8, 18.7) | 57.7 (51.1, 67.0) | 56.7 (52.0, 64.3) |

| Height (cm) | 98.1 (93.8, 102) | 107 (101, 111) | 96.5 (92, 103) | 94.9 (92.0, 98.2) | 96.3 (91.0, 100) | 98.8 (91.0, 103) | 107 (104, 112) | 157 (153, 161) | 157 (153, 164) |

| Retinol (μmol/L)2 | 0.833 (0.668, 0.959) | 0.787 (0.679, 0.932) | 0.778 (0.635, 0.941) | 1.07 (0.890, 1.29) | 1.04 (0.845, 1.22) | — | 0.959 (0.762, 1.17) | 1.64 (1.33, 2.09) | 1.55 (1.31, 1.94) |

| RBP (μmol/L)2 | 0.818 (0.675, 1.09) | 0.875 (0.665, 0.990) | 0.860 (0.685, 1.03) | 0.935 (0.745, 1.24) | 0.805 (0.667, 1.01) | — | 0.93 (0.697, 1.35) | — | — |

| CRP (mg/L)2 | 0.120 (0.010, 1.012) | 3.07 (0.535, 16.2) | 0.230 (0.010, 0.930) | 0.140 (0.010, 0.890) | 0.235 (0.010, 1.250) | 1.37 (0.773, 2.43) | 1.36 (0.433, 7.02) | — | — |

| AGP (g/L)2 | 0.705 (0.538, 1.12) | 1.12 (0.675, 1.48) | 0.705 (0.550, 1.19) | 0.630 (0.445, 0.915) | 0.645 (0.460, 0.915) | 1.12 (0.861, 1.64) | 2.39 (1.956, 2.88) | — | — |

| TBS (μmol) | 431 (290, 613) | 644 (519, 922) | 105 (60, 154) | 561 (418, 678) | 217 (147, 307) | — | 700 (536, 852) | 451 (319, 609) | 285 (209, 459) |

| TLR (50%)3 | 0.489 (0.339, 0.742) | 0.632 (0.538, 0.853) | 0.121 (0.072, 0.176) | 0.684 (0.548, 0.863) | 0.251 (0.182, 0.350) | — | 0.652 (0.528, 0.845) | 0.165 (0.111, 0.213) | 0.102 (0.076, 0.160) |

| TLR (80%)4 | 0.783 (0.542, 1.187) | 1.01 (0.861, 1.37) | 0.193 (0.115, 0.282) | 1.10 (0.877, 1.381) | 0.401 (0.291, 0.560) | — | 1.04 (0.845, 1.35) | 0.264 (0.178, 0.341) | 0.163 (0.121, 0.255) |

AGP, α-1-acid-glycoprotein; TLR, total liver vitamin A reserve; TBS, total body vitamin A store; —, not measured or data not available.

Data are % or median (Q1, Q3).

Analytes measured in serum.

Total liver reserves assuming 50% of total body vitamin A in liver.

Total liver reserves assuming 80% of total body vitamin A in liver.

Serum retinol 13C-natural abundance among countries

The serum and breastmilk VA 13C-natural isotopic abundance among studies is reported in Figure 1. The overall significance of differences in natural abundance by study was P < 0.0001. Although most studies did not differ from each other, Burkina Faso and South Africa had significantly higher enrichment than both studies of children in Zambia. The Zambian 2012 study had significantly lower enrichments than all other studies.

FIGURE 1.

Serum vitamin A 13C natural isotopic abundance in humans by study and lactation status from 6 African countries. 13C isotopic abundance is the fraction of 13C out of total carbon (%). Data are mean ± SD. Serum retinol and milk vitamin A 13C isotopic abundance means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

Correlates of VA 13C enrichment

Spearman correlations of serum and milk 13C enrichment with age and biomarkers for VA status (i.e., serum retinol, RBP, and TBSs) and inflammation (i.e., CRP and AGP) are shown in Table 2. Data from serum enrichment were analyzed separately between children and women. For children, age, TBSs, CRP, and AGP had significant inverse associations with retinol 13C enrichment. In a mixed model with age and sex as fixed effects and study as a random effect, neither age nor sex were significant.

TABLE 2.

Spearman correlations among serum and milk vitamin A 13C-natural abundance with age and serum nutritional and inflammatory biomarkers in children and women from 6 African countries

| Age | Retinol1 | RBP1 | CRP1 | AGP1 | TBSs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum retinol 13C-natural enrichment | ||||||

| Children | −0.35∗∗∗ | 0.049 | 0.031 | −0.16∗∗∗ | −0.34∗∗∗ | −0.096∗ |

| n | 632 | 574 | 534 | 615 | 618 | 570 |

| Women | −0.025 | 0.086 | — | — | — | 0.51∗∗∗ |

| n | 131 | 135 | — | — | — | 136 |

| Milk vitamin A 13C-natural enrichment | ||||||

| Women | 0.0096 | 0.21 | — | — | — | 0.28† |

| n | 47 | 46 | — | — | — | 47 |

Significant correlations are indicated by: ∗ P < 0.05, ∗∗∗ P < 0.001. † P = 0.06

AGP, α-1-acid-glycoprotein; TBS, total body vitamin A store.

Analytes measured in serum.

In women, correlates with serum retinol 13C enrichment had similar significance patterns between lactating and nonlactating women (data not shown); correlations reflected pooled data from all women. 13C enrichment was significantly and positively associated with TBSs. Milk VA 13C enrichment did not have any significant associations; the correlation estimate with TBSs was also positive with P = 0.06.

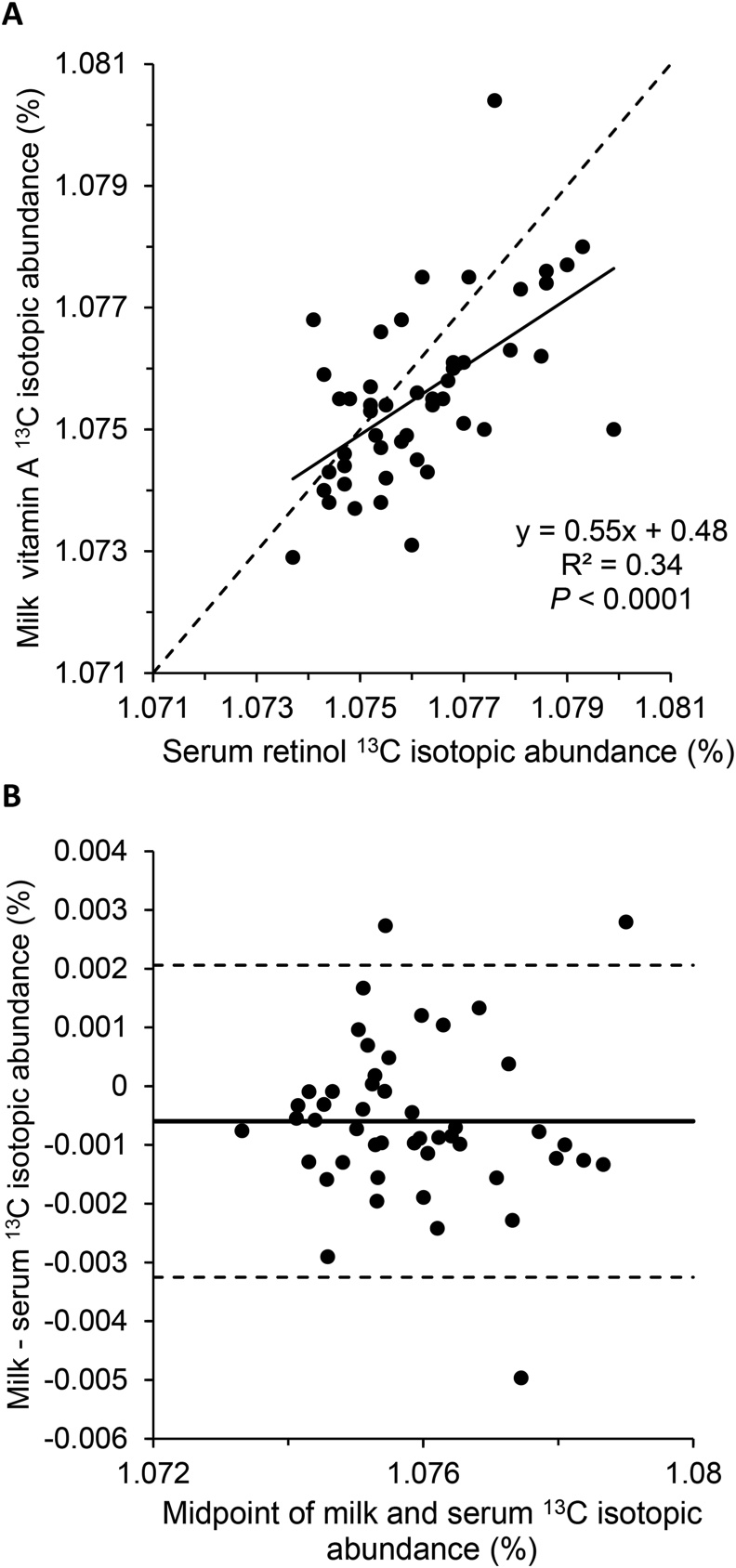

Comparison of VA 13C enrichment in paired serum and milk

In the subgroup of lactating women in Zambia, serum and milk VA 13C enrichment were compared. Overall, there was a statistically significant, moderate association between serum and milk enrichment (Figure 2A; Spearman correlation coefficient 0.52, P = 0.0001). Bland–Altman analysis revealed an isotopic abundance (%) mean bias of −0.00060 with 95% limits of agreement of −0.00325 and 0.00206 (Figure 2B). There was no notable pattern of bias related to 13C isotopic abundance.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of paired serum and milk vitamin A 13C natural abundance in lactating women in Zambia (n = 48). (A) Scatter plot with best fit line (solid) and line of identity (dashed). (B) Bland–Altman plot with mean bias (solid line) and upper and lower 95% limits of agreement (dashed lines).

Impact of individual vs. population natural abundance on RID

Mean bias, bias fraction of reference mean (%), and 95% limits of agreement for comparing TBS and TLR using individual compared with study or global population retinol 13C-natural abundance are presented in Table 3. In children, study-level 13C-natural abundance had a mean bias percentage range of −1.7% to −0.7%, whereas global-level outcomes had a mean bias percentage range of 1.4%–2.2% for RID outcomes. In women, study- and global-level 13C-natural abundance had a consistent direction of mean bias, which ranged from −3.7% to −1.6%. Limits of agreement were wider using global estimates compared with study estimates in children, whereas they were more comparable in women. Limits of agreement ranged from −23% to 37% in children and −21% to 14% in women.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of vitamin A total body stores and estimated liver concentrations using individual and population retinol 13C-natural abundance in children and women from 6 African countries

| TBS-study1 |

TBS-global1 |

TLR-study |

TLR-global |

TLR-study |

TLR-global |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μmol) | 50% of TBS in liver (μmol/g) | 80% of TBS in liver (μmol/g) | ||||

| Children | ||||||

| Mean bias | −17 | 14 | −0.018 | 0.011 | −0.029 | 0.017 |

| 95% LoA | (−318, 283) | (−370, 398) | (−0.343, 0.306) | (−0.390, 0.411) | (−0.549, 0.490) | (−0.623, 0.657) |

| Mean bias % of reference mean2 | −1.7 | 2.2 | −0.7 | 1.4 | −1.1 | 2.2 |

| 95% LoA | (−23, 20) | (−32, 37) | (−15, 13) | (−20, 23) | (−23, 21) | (−32, 37) |

| n | 570 | 568 | 568 | |||

| Women | ||||||

| Mean bias | −31 | −25 | −0.010 | −0.008 | −0.016 | −0.012 |

| 95% LoA | (−202, 139) | (−180, 130) | (−0.063, 0.043) | (−0.056, 0.041) | (−0.100, 0.069) | (−0.090, 0.066) |

| Mean bias % of reference mean2 | −3.7 | −2.5 | −2.3 | −1.6 | −3.7 | −2.5 |

| 95% LoA | (−21, 14) | (−20, 14) | (−13, 9) | (−12, 9) | (−21, 14) | (−20, 14) |

| n | 136 | 136 | 136 | |||

LoA, limits of agreement; TBS, total body vitamin A store; TLR, total liver vitamin A reserve.

Study and global refer to TBS or TLR outcomes calculated using study and global population-level retinol 13C-natural abundance values, respectively.

Mean bias, mean bias % of individual reference, and 95% limits of agreement were determined relative to vitamin A outcomes calculated using individual retinol 13C-natural abundance values within children or women subgroups.

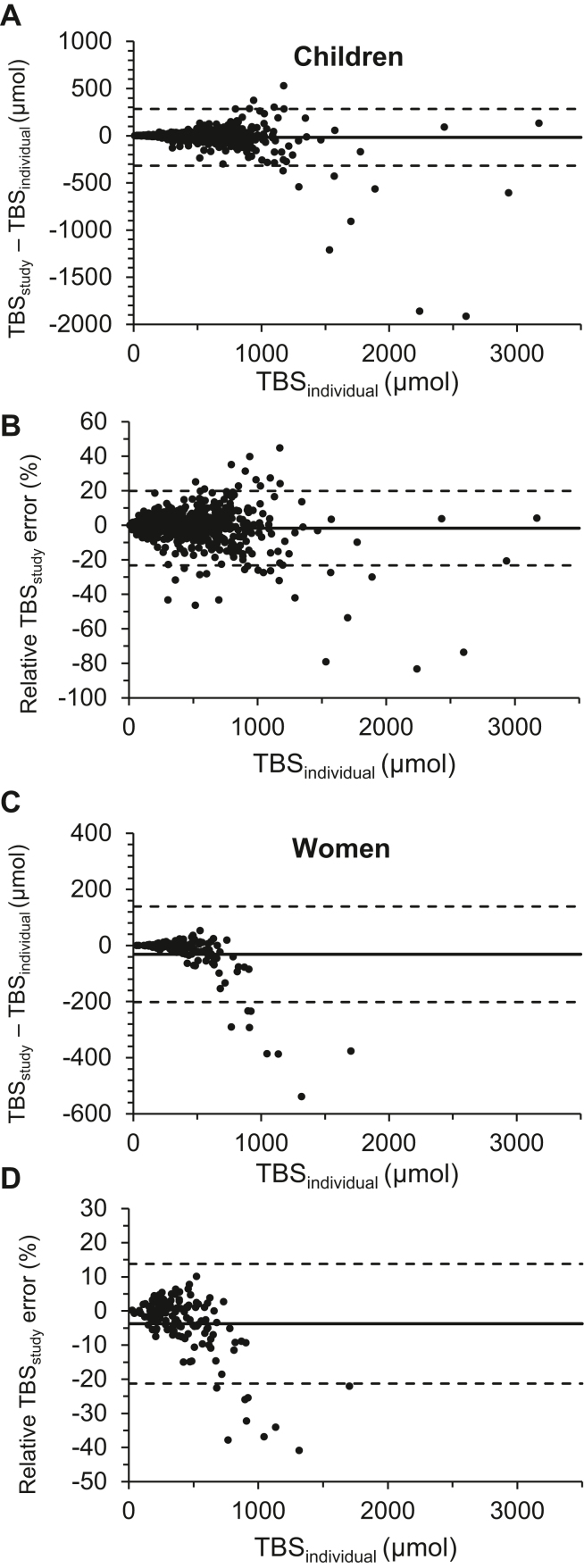

For children, covariates associated with error in TBSstudy and TBSglobal compared with TBSindividual (all μmol) were: TBSs (β = 70.8 and 85.9, respectively, both P < 0.001, Figure 3A, 3B) and a TBSs by retinol 13C-natural abundance percentage interaction (β = −65.9, −79.8, respectively, both P <0.001). The effect of retinol 13C-natural abundance was significant for TBSglobal only (β = 3481, P = 0.08; β = 6949, P = 0.021; respectively), as was ln CRP, but with a small impact on error (mg/L, β = −1.2, P = 0.30; β = −0.88, P = 0.012; respectively). Study effects with P value of <0.05 included Cameroon, South Africa, and Zambia 2012 (Z = 35.1, 43.6, and −57.5, respectively). Serum retinol, RBP, and AGP levels were not significantly associated with either TBSstudy or TBSglobal.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of vitamin A total body stores (TBSs) using individual and population retinol 13C natural abundance in children and women from 6 African countries. Bland–Altman analysis compared the difference in vitamin A TBSs calculated using individual (TBSindividual) and study population level (TBSstudy) retinol 13C natural abundance against TBSindividual as the reference. Relative TBSstudy error (%) was calculated as (TBSstudy – TBSindividual)/TBSindividual. (A) Children with available TBSindividual data (n = 570) and (B) relative TBSstudy error (%). (C) Lactating and nonlactating women with available TBSindividual (n = 136) and (D) relative TBSstudy error (%).

For women, error in TBSstudy and TBSglobal was associated with TBSs (β = 83.2, 83.9, Figure 3C, 3D), retinol 13C-natural abundance (β = 19,089, 17,250), and their interaction (β = −77.4, −78.0), all respectively and P < 0.001; serum retinol was not significantly associated with either TBSstudy or TBSglobal.

Discussion

This study demonstrated within- and between- country differences in VA 13C-natural enrichment, which had significant associations with age, inflammation, and TBSs. Comparing TBSs calculated using individual or population estimates of retinol 13C-natural abundance demonstrated low mean bias but wide 95% limits of agreement. We conclude that variation in retinol 13C-natural abundance should be expected in other populations or population subgroups. Using study-specific or population retinol 13C-natural abundance estimates would be expected to provide reasonably accurate estimates of continuous RID outcomes, but individual-level natural abundance measurements would be necessary for accurate determination of VA stores and resulting status (deficient, adequate, or excessive) at the individual level.

This analysis included a relatively large sample size by combining VA 13C-natural isotopic enrichment among 8 studies in 6 African countries. Analysis of 13C-natural abundance for all studies was conducted in the same laboratory. The use of GC-C-IRMS provides high sensitivity and precision for determining 13C abundance at natural enrichment levels [30], which is required for determining subtle differences in enrichments among populations, as shown in this study. Furthermore, we observed that age, TBSs, and inflammation were all inversely associated with retinol 13C abundance in children and positively associated with TBSs in women. The comparison between paired serum and breastmilk VA 13C-natural abundance demonstrated that these 2 sources provide comparable results, which is in agreement with a prior report [24].

The inverse association of retinol 13C enrichment with age is consistent with age-related changes in hair 13C enrichment following weaning in children [31] and in RBC 13C and 15N in adolescents compared with older adults [32]. Both instances are hypothesized to be because of life stage-associated dietary patterns; differences in subsistence-based compared with market-based diets [32], and the transition from breastfeeding through weaning [31,32]. These factors could explain the similar effect of age that we observed in this study and are reflected in the lack of significance of an age effect on retinol 13C enrichment when between-study variability was controlled.

Breastfeeding acts as an additional trophic level, resulting in enriched 13C in the child relative to the mother. This difference slowly equilibrates to others consuming similar diets by 4 y of age [31]. We noticed a similar decrease in enrichment in children spanning this age range, which would be consistent with weaning following breastfeeding. Children in these studies would have had access to both high-dose VA supplements before the age of 5 y and fortification of foods, such as sugar, which would decrease 13C in the retinol body pool. However, in our study, we observed that lactating women had very similar serum and milk VA 13C enrichments, indicating that this stage is not responsible for significant 13C fractionation for VA. It is possible that different dietary forms of VA (e.g., provitamin A carotenoids, preformed VA from animal source foods, or supplements) could undergo differential 13C fractionation during digestion, absorption, and metabolism because of the nutrient form and food matrix.

In women, TBSs were positively associated with retinol 13C enrichment. This could result from those with higher TBSs consuming VA-rich foods or supplements that have higher 13C enrichment. Additionally, it could be that through continued metabolism and recycling of VA in the body, the VA pool is slowly enriched over time. VA is fat-soluble and primarily stored in the liver; however, it recycles extensively between liver, blood, and extrahepatic target tissues. It has a relatively long system half-life of approximately140 d in humans with adequate to high VA stores, and a tracer dose was detectible for 5 y in a human female [33], providing ample time for fractionation to take place and accumulate during these metabolic processes in those with higher stores.

A limitation of this analysis is that we were not able to assess biomarkers of interest (e.g., CRP and AGP) in all studies. It remains to be answered if the same relationship between 13C enrichment and inflammation would hold in women. We cannot determine any causal directionality in this relationship; one explanation for the association observed could be that altered VA metabolism during inflammation could result in human metabolic isotopic fractionation. In rats, induced inflammation reduced hepatic VA mobilization, which resulted in a decoupling of VA tracer enrichment between liver VA stores and more recently ingested VA circulating in blood. A similar effect in humans could bias circulating retinol 13C enrichment toward the enrichment of recently consumed VA, which would then equilibrate toward enrichment of VA stores when inflammation resolves. This is consistent with the inverse association of CRP with retinol 13C-natural abundance and the hypothesis of gradual enrichment of the VA storage pool because of metabolic fractionation over time. If unaccounted for, this could produce errors in both retinol 13C-natural enrichment and RID outcomes. We note that the rat study induced significant inflammation, and these studies excluded participants with fever. We only noticed a minor significant effect of CRP on TBSglobal estimates in children but not on any study population-level estimates. It could also be that differences in VA enrichments are due to dietary pattern differences, which in turn alter immune function and inflammatory response. One analysis in children in Bangladesh revealed that hair 13C enrichment was lower in stunted children, hypothesized to be because of diets lower in animal-sourced foods [31].

Additionally, analysis of food samples for VA 13C enrichment would allow further explanation of differences among and between countries. Determining the 13C enrichment patterns of plant and animal source foods, fortificants, and supplements could help explain the natural variation observed between studies included in this analysis. Furthermore, this could allow estimation of relative contributions of each of these components to VA status, provided they had enough variation in natural enrichments. This has been demonstrated between a C3 plant (carrot), a C4 plant (maize), and a fortificant in a gerbil model [16] and evaluated in humans following a biofortified maize feeding trial [17]. Nonetheless, the difference between the South African and Zambian child cohorts is likely a direct result of the diets consumed. The children in the area studied in South Africa consumed sheep liver, which would have a higher enrichment due to the C4 grasses that the sheep consume [20]. This is in contrast to the Zambian children who consumed many orange fruits and vegetables, which are all C3 plants [23,34]. The synthetic retinyl palmitate from mandated fortified sugar and World Health Organization recommended high-dose supplements typically have a lower enrichment of 13C [35].

Future research directions include assessing inflammatory biomarkers in lactating and nonlactating women to see if the same relationship between 13C enrichment and inflammation observed in children is also observed in women. This could provide insights as to what physiologic states or metabolic processes impact VA 13C stable isotope ratios so these covariates can be accounted for in analysis of dietary intakes or tracer studies. Further modeling studies could assess the impact of RID calculation error from study- or population-level estimates on the diagnostic accuracy to categorize VA status as deficient, adequate, or excessive. This study shows that there are within- and between-population differences in VA 13C enrichment that should be considered for VA applications utilizing 13C stable isotope methodology. In the application of the RID test, clinical studies evaluating individual VA status should always measure the baseline 13C enrichments. Even individual differences are significant and dependent on foods consumed and supplement usage [17]. Restriction of foods and supplements high in VA during the RID mixing period is often used to eliminate influence on the serum to liver tracer ratio when individual VA status is important [36,37]. However, in population surveys, analysis of a subgroup or a nondosed group is recommended to reduce evaluation costs, and dietary restriction is usually not feasible.

Biomarkers of dietary intake are important to address compliance to interventions. Although the concept of precision or personalized nutrition is relatively new and has some strengths in regard to health benefits [38], more research is needed to ensure that methods to assess dietary intake and nutritional status are accurate and accessible at the individual level. Having biomarkers available to support survey tools such as dietary recalls and food frequency questionnaires will be essential for randomized controlled trials designed to evaluate individualized dietary recommendations.

Acknowledgments

The authors‘ responsibilities were as follows – BMG: conceptualized and conducted data analysis and wrote the manuscript; OS: was involved in field coordination and sample collection in Burkina Faso; ANZ: was the principal scientist (PS) in Burkina Faso; GMN: was involved in sample collection and was the PS in Cameroon; MW: was involved in sample collection and was one of the PSs in Ethiopia; THB: was also the PS in Ethiopia; MEvS: was the PS in South Africa and was involved in sample collection; MAD: was the study pediatrician in South Africa and involved in sample collection; EU: was the PS in Tanzania and was involved in sample collection; CK: was the PS for the study in Zambian women; JC: was the local PS for the studies in Zambian children; NK: assisted in field operations in all Zambian studies; CRD: processed all data from the GC-C-IRMS, trained 3 PSs, and contributed to data analysis and interpretation; MG: trained representatives from all studies in Cameroon during a regional meeting and performed GC-C-IRMS analyses; SAT: conceptualized these analyses, critically revised the manuscript, was a consultant to all the countries involved in their individual studies, and was PS for the studies in Zambian children; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.02.002.

Contributor Information

Bryan M. Gannon, Email: bgannon@wisc.edu.

Sherry A. Tanumihardjo, Email: sherry@nutrisci.wisc.edu.

Funding

Manuscript preparation was supported by NIH-R01 DC019357 and Particles for Humanity. Sample collection was supported by the regional Technical Cooperation project RAF6047 from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the IAEA Coordinated Research Project E4.30.30, contract number 18842 (to MEvS and MAD); the Tanzania Food and Nutrition Center (EMU); and the Ethiopian Public Health Institute (to THB and MW). The study of Zambian women was funded in part by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Global Health Institute visiting scholar fellowship (to CK and SAT), an endowment entitled “Friday Chair for Vegetable Processing Research” (to SAT), and HarvestPlus. NIH grant T32-DK007665 (BMG) and HarvestPlus also supported the field expenses for the studies of Zambian children.

Author disclosures

BMG, OOS, ANZ, GMN, THB, MW, MEvS, MAD, EMU, CK, JC, NK, CRD, MG, and SAT, no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rodgers G.P., Collins F.S. Precision nutrition-the answer to “what to eat to stay healthy”. JAMA. 2020;324(8):735–736. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institutes of Health. 2020–2030 Strategic plan for NIH nutrition research: a report of the NIH Nutrition Research Task Force. [Internet] 2020 https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/onr/strategic-plan Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reitsema L.J. Beyond diet reconstruction: stable isotope applications to human physiology, health, and nutrition. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2013;25(4):445–456. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien D.M. Stable isotope ratios as biomarkers of diet for health research. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2015;35:565–594. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071714-034511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao L., Liang Y., Trahanovsky W.S., Serfass R.E., White W.S. Use of a 13C tracer to quantify the plasma appearance of a physiological dose of lutein in humans. Lipids. 2000;35(3):339–348. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfe R.R., Chinkes D.L. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2004. Isotope tracers in metabolic research: principles and practice of kinetic analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien D.M., Kristal A.R., Jeannet M.A., Wilkinson M.J., Bersamin A., Luick B. Red blood cell delta15N: a novel biomarker of dietary eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid intake. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;89(3):913–919. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel P.S., Cooper A.J., O’Connell T.C., Kuhnle G.G., Kneale C.K., Mulligan A.M., et al. Serum carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes as potential biomarkers of dietary intake and their relation with incident type 2 diabetes: the EPIC-Norfolk study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;100(2):708–718. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.068577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yun H.Y., Lampe J.W., Tinker L.F., Neuhouser M.L., Beresford S.A.A., Niles K.R., et al. Serum nitrogen and carbon stable isotope ratios meet biomarker criteria for fish and animal protein intake in a controlled feeding study of a Women’s Health Initiative cohort. J. Nutr. 2018;148(12):1931–1937. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dierkes J., Dietrich S., Abraham K., Monien B.H., McCann A., Borgå K., et al. Stable isotope ratios of nitrogen and carbon as biomarkers of a vegan diet. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023;62(1):433–441. doi: 10.1007/s00394-022-02992-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien D.M., Sagi-Kiss V., Palma-Duran S.A., Cunningham C., Barrett B., Johnston C.S., et al. An evaluation of the serum carbon isotope ratio as a candidate predictive biomarker of the dietary animal protein ratio (animal protein/total protein) in a 15-day controlled feeding study of US adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022;115(4):1134–1143. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoeller D.A. Isotope fractionation: why aren’t we what we eat? J. Archaeol. Sci. 1999;26(6):667–673. doi: 10.1006/jasc.1998.0391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davy B.M., Jahren A.H., Hedrick V.E., You W., Zoellner J.M. Influence of an intervention targeting a reduction in sugary beverage intake on the δ13C sugar intake biomarker in a predominantly obese, health-disparate sample. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(1):25–29. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahren A.H., Saudek C., Yeung E.H., Kao W.H., Kraft R.A., Caballero B. An isotopic method for quantifying sweeteners derived from corn and sugar cane. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;84(6):1380–1384. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.6.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang Y., White W.S., Yao L., Serfass R.E. Use of high-precision gas isotope ratio mass spectrometry to determine natural abundance 13C in lutein isolated from C3 and C4 plant sources. J. Chromatogr. A. 1998;800(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)00897-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gannon B.M., Pungarcher I., Mourao L., Davis C.R., Simon P., Pixley K.V., et al. 13C natural abundance of serum retinol is a novel biomarker for evaluating provitamin A carotenoid-biofortified maize consumption in male Mongolian gerbils. J. Nutr. 2016;146(7):1290–1297. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.230300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Titcomb T.J., Sheftel J., Sowa M., Gannon B.M., Davis C.R., Palacios-Rojas N., et al. beta-Cryptoxanthin and zeaxanthin are highly bioavailable from whole-grain and refined biofortified orange maize in humans with optimal vitamin A status: a randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018;108(4):793–802. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newton S., Owusu-Agyei S., Asante K.P., Amoaful E., Mahama E., Tchum S.K., et al. Vitamin A status and body pool size of infants before and after consuming fortified home-based complementary foods. Arch. Public Health. 2016;74:10. doi: 10.1186/s13690-016-0121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinkaew S., Wegmuller R., Wasantwisut E., Winichagoon P., Hurrell R.F., Tanumihardjo S.A. Triple-fortified rice containing vitamin A reduced marginal vitamin A deficiency and increased vitamin A liver stores in school-aged Thai children. J Nutr. 2014;144(4):519–524. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.182998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Stuijvenberg M.E., Dhansay M.A., Nel J., Suri D., Grahn M., Davis C.R., et al. South African preschool children habitually consuming sheep liver and exposed to vitamin A supplementation and fortification have hypervitaminotic A liver stores: a cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019;110(1):91–101. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urio E.M., Tanumihardjo S.A., Fweja L.W., Ndossi G.D. Total liver vitamin A reserves, determined with 13C2-retinol isotope dilution, are similar among Tanzanian preschool children in areas with low and high vitamin A exposure. J. Nutr. 2023;152(12):2699–2707. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxac227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bresnahan K.A., Chileshe J., Arscott S., Nuss E., Surles R., Masi C., et al. The acute phase response affected traditional measures of micronutrient status in rural Zambian children during a randomized, controlled feeding trial. J. Nutr. 2014;144(6):972–978. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.192245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gannon B., Kaliwile C., Arscott S.A., Schmaelzle S., Chileshe J., Kalungwana N., et al. Biofortified orange maize is as efficacious as a vitamin A supplement in Zambian children even in the presence of high liver reserves of vitamin A: a community-based, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;100(6):1541–1550. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.087379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaliwile C., Michelo C., Sheftel J., Davis C.R., Grahn M., Bwembya P., et al. Breast milk-derived retinol is a potential surrogate for serum in the 13C-retinol isotope dilution test in Zambian lactating women with vitamin A deficient and adequate status. J. Nutr. 2021;151(1):255–263. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suri D.J., Sombier O., Zeba A.N., Nama G.M., Bekele T.H., Woldeyohannes M., et al. Association between biomarkers of inflammation and total liver vitamin A reserves estimated by 13C-retinol isotope dilution among preschool children in five African countries. J. Nutr. 2023;153(3):622–635. doi: 10.1016/j.tjnut.2022.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erhardt J.G., Estes J.E., Pfeiffer C.M., Biesalski H.K., Craft N.E. Combined measurement of ferritin, soluble transferrin receptor, retinol binding protein, and C-reactive protein by an inexpensive, sensitive, and simple sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique. J. Nutr. 2004;134(11):3127–3132. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coplen T.B. Guidelines and recommended terms for expression of stable-isotope-ratio and gas-ratio measurement results. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 2011;25(17):2538–2560. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saxton A. Proceedings of the 23rd SAS Users Group International. 1998. A macro for converting mean separation output to letter groupings in Proc Mixed; pp. 1243–1246. March 22-25, 1998, Nashville, TN. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gannon B.M., Tanumihardjo S.A. Comparisons among equations used for retinol isotope dilution in the assessment of total body stores and total liver reserves. J. Nutr. 2015;145(5):847–854. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.208132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preston T. Existing and emerging technologies for measuring stable isotope labelled retinol in biological samples: isotope dilution analysis of body retinol stores. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2014;84(Suppl 1):30–39. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dailey-Chwalibóg T., Huneau J.F., Mathé V., Kolsteren P., Mariotti F., Mostak M.R., et al. Weaning and stunting affect nitrogen and carbon stable isotope natural abundances in the hair of young children. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):2522. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59402-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkinson M.J., Yai Y., O’Brien D.M. Age-related variation in red blood cell stable isotope ratios (delta13C and delta15N) from two Yupik villages in southwest Alaska: a pilot study. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(1):31–41. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i1.18222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gannon B.M., Valentine A.R., Davis C.R., Howe J.A., Tanumihardjo S.A. Duration of retinol isotope dilution studies with compartmental modeling affects model complexity, kinetic parameters, and calculated vitamin A stores in US women. J. Nutr. 2018;148(8):1387–1396. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmaelzle S., Kaliwile C., Arscott S.A., Gannon B., Masi C., Tanumihardjo S.A. Nutrient and nontraditional food intakes by Zambian children in a controlled feeding trial. Food Nutr. Bull. 2014;35(1):60–67. doi: 10.1177/156482651403500108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howe J.A., Valentine A.R., Hull A.K., Tanumihardjo S.A. 13C natural abundance in serum retinol acts as a biomarker for increases in dietary provitamin A. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2009;234(2):140–147. doi: 10.3181/0806-RM-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green M.H., Ford J.L., Green J.B. Retinol isotope dilution is applied during restriction of vitamin A intake to predict individual subject total body vitamin A stores at isotopic equilibrium. J. Nutr. 2016;146(11):2407–2411. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.238899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheftel J., Smith J.B., Tanumihardjo S.A. Time since dose and dietary vitamin A intake affect tracer mixing in the 13C-retinol isotope dilution test in male rats. J. Nutr. 2022;152(6):1582–1591. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxac051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ordovas J.M., Ferguson L.R., Tai E.S., Mathers J.C. Personalised nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018;361:k2173. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.