Abstract

Aim

This case series elaborates on the importance, advantages, and clinical applications of removable partial dentures as prosthetic rehabilitation in pediatric dental patients.

Background

Tooth loss in children is a measure of dental disease with multiple determinants. There are several potential sequelae as a result of tooth loss. Early treatment and follow-up are the keys to the successful rehabilitation of young patients with missing teeth. It is critical that oral rehabilitation is started early to maintain and correct oral functions. Removable prostheses are the commonly selected treatment options for young patients because of the continuous growth and development of maxillary and mandibular bones. Dental prosthetic appliances in pediatrics must be planned with respect to the special conditions that lead to tooth loss or damage.

Case description

The present case series is a compilation of four cases describing the esthetic, functional, and psychological rehabilitation of children with missing teeth, either hereditary/genetic (ectodermal dysplasia) or due to premature tooth loss (trauma).

Conclusion

Prosthetic rehabilitation with a removable partial denture in children requires a specific management strategy. A multidisciplinary approach is needed under the constant supervision of pediatric dentists as well as regular check-ups with clinical and radiographical examinations.

How to cite this article

Goswami M, Chauhan N. Prosthetic Management with Removable Partial Dentures in Pediatric Dental Care: Case Series. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2023;16(3):534-540.

Keywords: Children, Prosthetic management, Removable partial denture, Tooth loss

Introduction

Missing teeth, either hereditary/genetically or due to premature tooth loss in children and adolescents, is probably one of the commonest problems encountered by pediatric dentists in their routine practice.1 The reasons for the absence of teeth in children include dental caries, trauma, several genetic and hereditary diseases such as cleft lip and palate deformities, amelogenesis and dentinogenesis imperfecta, ectodermal dysplasia, oral-facial-digital syndromes and syndromes with oral-facial cleftings such as Pierre-Robin sequence and Van der Woude syndrome, cysts and tumors of the jaw, periodontal diseases, etc. (Tables 1 and 2).2,3 Worldwide, in primary dentition, the prevalence of congenitally missing teeth ranges from 0.1 to 2.4%. Also, primary dental aplasia is usually followed by permanent tooth missing, the prevalence of which ranges between 0.15 and 16.2%.1 The prevalence of premature primary tooth loss reported in several studies ranges from 4.3 to 42.6%.4 Partial edentulousness is a dental arch in which one or more but not all natural teeth are missing. According to Zaigham et al. and Abdel Rahman et al., the major causes of partial loss of teeth were dental caries and periodontal diseases in early childhood and adolescence. The partial absence of teeth can lead to certain clinical challenges and lifestyle compromises. It can lead to supra eruption of opposing teeth, drifting of adjacent teeth, leading to malocclusion, alteration in speech, changes in the development of the successor permanent teeth, esthetic concerns in case of anterior teeth loss, development of oral habits, and can affect overall arch integrity.2,5 Complete loss of teeth usually occurs as part of a syndrome that includes other abnormalities. It can lead to masticatory problems, occlusal disharmony, continuing degradation of the alveolar bone, changes in facial appearance, lip support, and temporal-mandibular disorders. These, in turn, affect the child's overall well-being, self-esteem, and quality of life. All this necessitates the development of modern methods of pediatric prosthetic dentistry.

Table 1.

Causes of loss of teeth in primary dentition

| Early childhood caries and dental caries |

| Trauma |

| Due to congenital anomalies like cleft lip and palate deformities, amelogenesis imperfect, dentinogenesis imperfecta, dentin dysplasia, and congenital neutropenia |

| Periodontal cause—localized juvenile periodontitis, hereditary gingival fibromatosis (severe form) |

| Congenital hypodontia (syndromic and nonsyndromic)—ectodermal dysplasia, Apert syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome, Kabuki syndrome, Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome, Sjogren–Larsson syndrome, Rieger syndrome, Pierre–Robin sequence, Van der Woude syndrome, Goltz-Gorlin syndrome, Hanhart syndrome, KBG syndrome |

| Malignancies like Langerhans's cell histiocytosis, leukaemia |

| Metabolic diseases like acatalasia, hypophosphatasia, Gaucher's disease, juvenile diabetes, and scurvy |

Table 2.

Causes of loss of teeth in permanent dentition

| Dental caries |

| Periodontal diseases |

| Acute orofacial infection |

| Severe erosion, abrasion, and attrition |

| Orthodontic extraction |

| Maxillofacial trauma |

| Congenital anomalies like amelogenesis imperfecta, dentinogenesis imperfecta, and dentin dysplasia |

| Impaction |

| Pericoronitis |

| Risk factors like tobacco use and alcohol |

There are several prosthetic considerations available such as removable complete or partial dentures, overdentures, fixed denture prostheses, and implants.5 However, adequate prosthetic restoration in children or adolescents must not in any way hinder the proper development of jawbones and permanent teeth. Removable partial and complete dentures with acrylic denture bases are the most generally perceived choice for restoring the oral structure in children because they can be easily modified as the child grows.6 The purpose of this case series is to present the necessity, advantages, clinical outcome, and importance of removable partial dentures as a prosthetic rehabilitation in children.

Case Descriptions with Methodology

Four cases are discussed in this case series with detailed case history, including demographic details, past medical, dental, and family history, along with the history of presenting illness. Extraoral and intraoral examinations and required radiographic investigations were done. Treatment planning includes preventive and rehabilitative management after informed consent. The removable partial dentures were considered a viable option for rehabilitation, considering the requirement and patient's age ranging from 4 to 13 years in the present case series.

Children's behavior was managed using various modalities throughout the procedure. They were gradually exposed to the procedure and explained using the tell-show-do technique. The children were rewarded with positive reinforcement, including praising the behavior using contingency management techniques.

The size of the stock tray was selected for impression-making based on the arch length and width for each case. First, the mandibular impression was made, followed by the maxillary impression to decrease anxiety and for better comfort in the child patient with a hydrocolloid impression material alginate, and then the casts were made in dental stone. Custom trays were prepared and final impressions were made with rubber base impression material. Shellac base plates were adapted on upper and lower casts, and wax occlusal rims were then fabricated for recording vertical dimensions. The interincisal position was recorded in accordance with the medial line of the face. The shape and height of the maxillary occlusion line were adjusted to provide the lip support needed for good esthetics. Maxillomandibular relation was recorded and a new vertical dimension was determined. It was followed by mounting working casts in a mean articulator to evaluate the dentition and occlusal relationship. The suitable shade of artificial teeth was selected in natural light and arranged in wax for trial evaluation. Tooth positions and occlusal relationships were recorded during the try-in procedure, followed by the curing of the denture. Finishing and polishing were done and all occlusal interferences were eliminated on insertion of the final denture. The patient and parents were instructed about the insertion and removal of the denture and for maintenance of the prosthesis during routine oral hygiene practice. Soft tissues were examined for any erythema, soreness, and injury after the denture insertion. Recall visits were scheduled 24 hours after insertion, 1 week, then every 3–6 months as per the need of the patient, which can be due to any type of erythema, problem in chewing, speech alteration, soreness, frequent breakage of the denture, etc.7

Case 1

Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia

A 4-year-old boy reported missing teeth as the chief complaint. The patient was prediagnosed with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Family history revealed that his brother is also afflicted with the same condition. Extraoral examination revealed a hypoplastic midface, prominent forehead, thin eyebrows, and sparse fine hair (Fig. 1A). The intraoral examination revealed partially edentulous jaws with 55, 65, 75, 85 teeth present and thin alveolar ridge with reduced vertical bone height (Figs 1B to D). The panoramic view revealed four unerupted permanent first molars in the upper and lower jaw, that is, 16, 26, 36, and 46 (Fig. 1E). In order to improve the mastication, speech and appearance, removable partial upper and lower dentures were planned, as, prosthesis adjustments or replacement is due to continuing growth and development of jaws if the present denture will not function satisfactorily or after the exfoliation of primary teeth and eruption of permanent teeth in the oral cavity until more definitive prostheses can be delivered (Figs 1F to K).

Figs 1A to K.

(A) Extraoral view; (B, C, and D) Intraoral preoperative pictures depicting edentulous upper and lower jaws with all four first molars present; (E) OPG reveals erupting second molars; (F and G) Cast mounting and try-in procedure; (H, I, J, and K) Postoperative pictures depicting upper and lower RPDs

Case 2

Hidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia

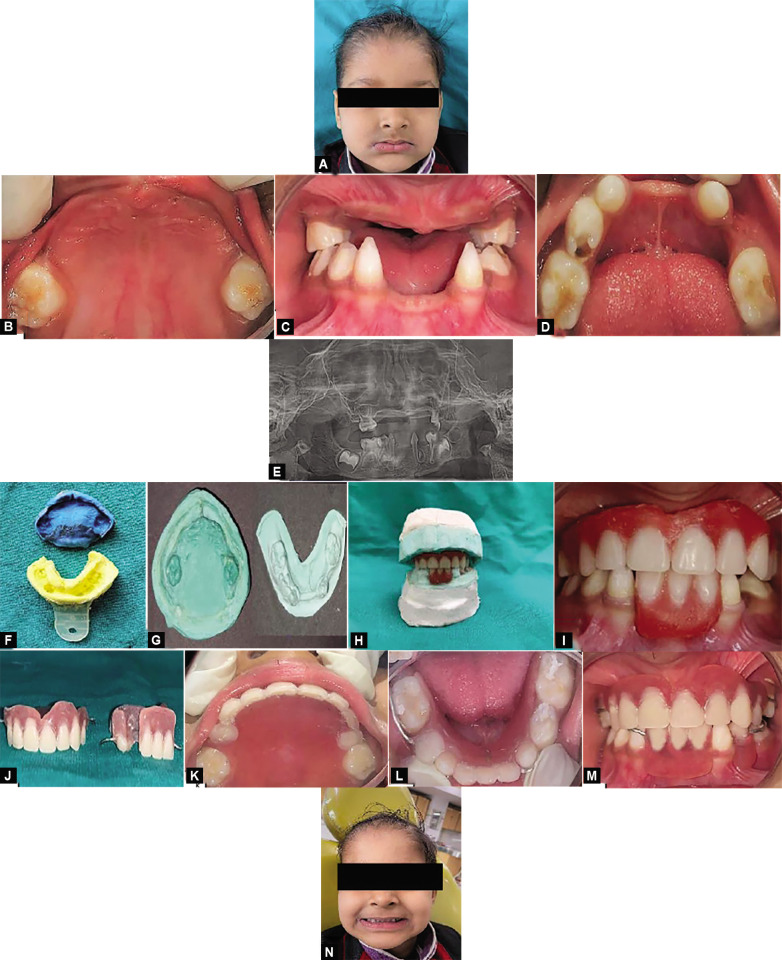

A 5-year-old boy reported a chief complaint of difficulty in speaking and eating due to the absence of multiple teeth. The patient was prediagnosed with hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. On extraoral examination, the patient presented with fine, sparse hair, scanty eyebrow and eyelashes, and full and everted lips (Fig. 2A). On intraoral examination, teeth present were 55, 65, 73, 74, 75, 83, and 85 of which carious teeth were 74, 75, and 85 (Figs 2B to I). Maxillary and mandibular removable partial dentures were planned and delivered to the patient with regular follow-ups in order to provide masticatory, speech, and esthetic results with the reestablishment of the occlusion by replacing missing teeth (Figs 2J to N).

Figs 2A to N.

(A) Extraoral view; (B, C, and D) Intraoral preoperative pictures depicting partially edentulous upper and lower jaws; (E) OPG reveals erupting mandibular molars; (F, G) Upper and lower impressions and casts; (H and I) Cast mounting and try-in procedure; (J, K, L, M, and N) Postoperative pictures depicting upper and lower RPDs

Case 3

Traumatic Dental Injury in Pediatric Case

An 11-year-old boy reported missing teeth with respect to 11 and 21 due to a fall while playing (Figs 3A to C). After model analysis for the available space, a removable partial denture with respect to right and left maxillary central incisors was fabricated as per the procedure described and delivered to the patient with regular follow-ups. (Figs 3D to F).

Figs 3A to F.

(A) Preoperative right side occlusal view; (B) Preoperative frontal view depicting missing teeth with respect to 11, 21; (C) Preoperative left side occlusal view; (D) Postoperative right side occlusal view; (E) Postoperative frontal view depicting RPD with respect to 11, 21; (F) Postoperative left side occlusal view

Case 4

Traumatic Dental Injury in Pediatric Case

A 13-years-old girl reported missing teeth with respect to 31 and 41 due to a fall from stairs (Figs 4A to C). Impressions were made for the upper and lower jaws, followed by model analysis for the available space. Fabrication of removable partial dentures was done with respect to the left and right mandibular central incisor following the described procedure and delivered to the patient with regular follow-ups (Figs 4D to F).

Figs 4A to F.

(A) Preoperative right side occlusal view; (B) Preoperative frontal view depicting missing teeth with respect to 31, 41; (C) Preoperative left side occlusal view; (D) Try-in procedure; (E and F) Postoperative picture depicting RPD with respect to 31, 41

Discussion

Prosthetic treatment plays an important role in providing functional and psychological integrity in children with the absence of teeth. This untimely tooth loss can be due to various reasons (Tables 1 and 2).2,3 Tooth loss due to caries or trauma is one of the most common reasons for the need for prosthetic rehabilitation in children. Reddy et al. and Ahamed et al. have reported high prevalence rates of 13.5 and 16.5% for premature loss of primary teeth in India, respectively.8,9 Another common reason for the need for prosthetic treatment in children includes the hereditary/genetic absence of teeth. Shetty et al.10 in Karnataka and Kathariya et al.11 in Maharashtra reported the prevalence rate of hypodontia as 0.32 and 4.8%, respectively. In both conditions, whether acquired or hereditary/genetic tooth loss, there comes the necessity for the development of pediatric prosthetic dentistry (Table 3).2,4

Table 3.

Necessity for pediatric prosthetic dentistry

| To restore masticatory function and efficacy |

| To prevent misarticulation of consonants in speech |

| For provision of space maintenance |

| To restore the esthetics of patient |

| To prevent the development of deleterious oral habits. |

| For proper development and eruption of succedaneous tooth |

| To meet the psychological need |

The absence of teeth in a child can affect the mastication, speech, esthetics, arch integrity, sagittal, and vertical skeletal relationship in the oral cavity. So, it is important to diagnose and plan the treatment accurately to rehabilitate the patient at an optimum level. Treatment should be planned by a multidisciplinary team involving a pediatric dentist, orthodontist, oral and maxillofacial surgeon, and prosthodontics.15 As per an individual needs, factors that govern the treatment planning include the number of teeth present, interarch spacing, alveolar bone height and width, mucosal attachment, age of the patient, facial and lip support, the thickness of mucosa, and cost-effectiveness of the treatment.

Treatment option includes rehabilitation with a removable partial denture, fixed denture, overlay dentures, or implants. However, the continuous growth of jawbones and other physical changes that occur in a child influences the planning of treatment. A complete or partial removable overlay denture is fabricated of over-retained deciduous teeth or roots that are not prepared to cope with interfacing with the denture. However, overlay dentures can hinder the exfoliation of remaining deciduous teeth and would require frequent adjustment according to the patient's dental age and therefore avoided till another prosthesis can achieve superior results.12 Fixed partial dentures in young patients could interfere with jaw growth, especially if the prosthesis crosses the midline.13 Implants, if placed in the growing alveolar ridge, can lead to failure in the development of the ridge and effects negatively on the craniofacial growth of the child.14

Considering the age and oral needs of the patient, the removable partial denture was considered the classic conventional solution in all four cases. Prosthetic rehabilitation with removable dentures in children gives the advantage of the possibility for easy modification during the time of growth and development of the jawbones. The use of a removable partial denture allows relining and rebasing in the future, given that the growth of the patient is continuous; also, relining the existing removable partial denture reduces the cost and frequency of remaking the prosthesis in children. Making another set of removable partial dentures for child patients will then be easier as the child gets used to the procedure and wearing the removable partial dentures.15 Rathee et al. reported masticatory, esthetic, and speech skills improvement along with the development of a good psychological self-image after the insertion of removable partial dentures in children.16 Ideal requirements of removable partial dentures include the following (Table 4).17

Table 4.

Ideal requirement of removable partial denture

| Biological | Should be nontoxic, nonirritant, and noncarcinogenic |

| Chemical | Should be insoluble in oral fluids or any other fluids being taken by patient |

| Mechanical | Modulus of elasticity should be high. |

| Enables denture base to be rigid against masticatory forces | |

| Resilience should be high to protect underlying soft tissues by absorbing masticatory forces | |

| Should have a high elastic limit and proportional limit to prevent permanent deformation when stressed | |

| Should have adequate mechanical strength to resist fracture under repeated masticatory forces | |

| Should be dimensionally stable | |

| Should have adequate abrasion resistance | |

| Thermal | Should be the good thermal conductor |

| Esthetic | Should exhibit sufficient translucency so that it can be made to match appearance of tissues |

| Others | Should maintain desirable properties for extended periods after manufacture |

| Should be inexpensive | |

| Should be easy to repair | |

| Should be easy to clean | |

| Should have longer shelf life |

An important feature of prosthetic treatment in children is the difficulty in motivating patients and their parents, as they may underestimate the needs and benefits of timely treatment. The implementation of special management and motivational techniques becomes essential to maintain a good level of cooperation from a child patient. Dalkiz et al. suggested the use of motivation techniques such as self-training for the insertion and removal of impression trays and bringing the trays back home between clinical visits. Children playfully get indulged in this dental equipment and materials and may start behaviorally enjoying future dental visits. They found that this greatly reduced the child's stress during the stage of impression-taking.18 Oishi et al. use color-changeable chewing gum to encourage the patient to use dentures while eating, and thus improve mastication because the gum's sensory characteristics and flavor released by every chewing would be fresh and motivating for them, thus contributing to better masticatory performance.19 Vasconcellos et al. used an incentive chart with the aim of establishing rules and limits inside and outside the dental office, which was particularly effective in the behavior and developing maturity of the patient over the course of treatment.20 Overall, counseling parent and child patients with pediatric dentists and their teams contribute to a positive dental attitude.

Parents should be guided about the prosthetic importance of prosthetics for their children and informed about the present and future available treatment options. Where necessary, prosthetic treatment should be performed at the earliest to avoid further complications due to tooth loss. Prosthetic rehabilitation is recommended from the age of 5 years but can be started as early as 3–4 years of age for cooperative children.21 Till and Marques recommended that an initial prosthesis should be delivered before the child begins school so that the child has a normal appearance and time to adapt to the prosthesis.21 At least three replacements are needed between the period of mixed and permanent dentition. When the patient's dentition is permanent, the removable partial denture may be replaced with a fixed denture or by osseointegrated implants.15 Guckes et al. recommended that this approach should be postponed till the age of 13 because of possible implant movement caused by jaw growth.15 There is still controversy about the age at which fixed dentures or implant prostheses can be given in child patients. Some recommendations say to replace removable partial dentures with fixed/ implants from age 13 onward, but others suggest that implants placed after age 15 for girls and age 18 for boys have the most predictable prognosis.15,22

Considering the age and oral needs of the patients in the present case series, removable partial dentures can be considered a successful treatment modality in children with missing teeth for maintenance of normal physical, mental, and social development and should be encouraged in pediatric dental practice (Table 5). Removable partial denture rehabilitation led to significant improvements in masticatory functions, appearance, and speech and met the psychological needs of children at a tender age. Also, it helps in the preservation of the remaining teeth and the supporting structure in the oral cavity. Regular follow-ups are required in pediatric prosthetic rehabilitation because of the intense growth and development of an orofacial system in children.

Table 5.

Clinical significance of case series

| Clinical significance of this case series |

|---|

| Tooth loss is highly prevalent in children and young adolescents. Despite this, it is a highly underrated problem, as perceived by the patient and their parents. Therefore, it requires special attention to provide knowledge and guidance regarding management strategies for missing teeth in children |

| Childhood and adolescence represent a period of intense growth and development of the orofacial system. In such a gentle period, the replacement of missing teeth is of vital clinical importance so as to ensure proper chewing, aesthetics and phonetics, development of jaw bones, dental arches and permanent teeth |

| Prosthodontics in children is more challenging because of the anatomy, erupting teeth, growth pattern, patient cooperation and understanding. Pediatric patients often require more follow-ups than adult patients, needing procedures like reliners or refits of removable prostheses because of the growth pattern |

| Apart from physically missing teeth, tooth loss leads to unpleasant esthetics, which can develop feelings of inadequacy in children regarding their personal appearance. Hence, the implication of appropriate management strategies can prevent and reduce this physical and psychological trauma to the child |

| This case series provides clinical implications of the removable partial dentures on the management of missing teeth in pediatric patients with further future considerations which are valuable for pediatric dentists as well as general dentists in rehabilitation |

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Rakhshan V. Congenitally missing teeth (hypodontia): a review of the literature concerning the etiology, prevalence, risk factors, patterns and treatment. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2015;12(1):1–13. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.150286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaigham AM, Muneer MU. Pattern of partial edentulism and its association with age and gender. Pakistan Oral and Dental Journal. 2010;30(1):260–263. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chhabra N, Goswami M, Chhabra A. Genetic basis of dental agenesis-molecular genetics patterning clinical dentistry. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19(2):e112–e119. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalcanti A, Alencar C, Bezerra P, et al. Prevalence of early loss of primary molars in school children in Campina Grande, Brazil, Pak. Oral Dent J. 2008;28(1):113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel-Rahman HK, Tahir CD, Saleh MM, et al. Incidence of Partial edentulism and its relation with age and gender. Zanco J Med Sci. 2013;17:463–470. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teixeira Marques, NC, Gurgel CV, Fernandes AP, et al. Prosthetic rehabilitation in children: an alternative clinical technique. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:512951. doi: 10.1155/2013/512951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarangi D, Das S, Mohapatra A. Recall scheduling in removable prostheses patients. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2018;9:1149. doi: 10.5958/0976-5506.2018.01611.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy, N V, Daneswari V, Shruti G, et al. Premature loss of primary teeth on arch dimensions in 6- to 10-year-old schoolchildren in Khammam town, Telangana state. Int J Pedod Rehabil. 2018;3:67–71. doi: 10.4103/ijpr.ijpr_28_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahamed SS, Reddy VN, Krishnakumar R, et al. Prevalence of early loss of primary teeth in 5-10-year-old school children in Chidambaram town. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:27–30. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.94542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shetty P, Adyanthaya A, Adyanthaya S, et al. The prevalence of hypodontia and supernumerary teeth in 2469 school children of the Indian population: an epidemiological study. Indian J Stomatol. 2012;3:150–152. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kathariya MD, Nikam AP, Chopra K, et al. Prevalance of dental anomalies among school going children in India. J Int Oral Health. 2013;5:10–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haseeb PPA, Thakur S, Chauhan D. Pediatric prosthodontics: a systematic review. Int J Res Health Allied Sci. 2019;5(3):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grover R, Manjul M. Prosthodontic management of children with ectodermal dysplasia: review of literature. Dentistry. 2015;5:11. doi: 10.4172/2161-1122.1000340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li S, Xiao X, Wu R, et al. Early prosthetic treatment of children with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: six case reports. Int J Oral Dent Health. 2017;3:039. doi: 10.23937/2469-5734/1510039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guckes AD, Brahim JS, McCarthy GR, et al. Using endosseous dental implants for patients with ectodermal dysplasia. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;122:59–62. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1991.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rathee M, Malik P, Dua M, et al. Early functional, esthetic, and psychological rehabilitation of preschool child with nonsyndromic oligodontia and anodontia in mixed dentition stage through conservative systematic approacha case report with 5-year follow-up:. Contemp Clin Dent. 2016;7(2):232–235. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.183051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell SD, Cooper L, Craddock H, et al. Removable partial dentures: The clinical need for innovation. J Prosthet Dent. 2017;118(3):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalkiz M, Beydemir B. Pedodontic complete dentures. Turk J Med Sci. 2002;32(3):277–281. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oishi A, Hama Y, Kanai E, et al. Color-changeable chewing gum to motivate chewing training with complete dentures for a male patient with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia and oligodontia. Pediatric Dental Journal. 2021;31(1):123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pdj.2021.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasconcellos C, Imparato JCP, Rezende KM. Motivation chart as a supporting tool in pediatric dentistry. Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia. 2017;65(3):276–281. doi: 10.1590/1981-863720170002000153353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhargava A, Sharma A, Popli S, et al. Prosthodontic management of a child with ectodermal dysplasia: a case report. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2010;10(2):137–140. doi: 10.1007/s13191-010-0026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah RA, Mitra DK, Rodrigues SV, et al. Implants in adolescents. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17(4):546–548. doi: 10.4103/0972-124x.118335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]