Abstract

Rhinosinusitis is one of the most common inflammatory diseases. It has been recognized that intracranial vessels are involved and there might be an association with stroke occurrence. The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between rhinosinusitis and cardiovascular diseases, especially stroke, through a literature review. The review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. We performed on PubMed a literature search from February 2000 to February 2022, using the search terms ‘rhinosinusitis’ OR ‘chronic rhinosinusitis’ AND ‘stroke’ OR ‘ischemic stroke’. Fourteen studies were eligible and included in the analysis. Overall, the studies encompassed a total of 1,006,338 patients included in this review. All studies concluded that there is a statistically significant correlation between clinical or radiological sinus inflammation and the risk of stroke, which is independent of traditional stroke risk factors. In conclusion, rhinosinusitis is associated with an increased incidence of stroke.

Keywords: computed tomography, risk factor, sinusitis complication, magnetic resonance, atherosclerosis, ischemic stroke, chronic rhinosinusitis, acute rhinosinusitis

Introduction and background

Rhinosinusitis is a worldwide prevalent upper respiratory inflammation of the mucosa of the nose and paranasal sinuses and is classified into acute (<12 weeks) and chronic (>12 weeks) [1]. Left untreated or undertreated, it can lead to several serious infectious and vascular complications related to the central nervous system, such as meningitis, epidural, or subdural empyema, brain abscess, cranial nerve palsies, mycotic aneurysms, intracranial hypertension, and cavernous or sagittal sinus thrombophlebitis [1,2]. In addition, a close relationship between chronic inflammatory diseases and cardio-cerebrovascular disease has been noticed [3,4]. Interestingly, previous studies have revealed an association between chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and a higher risk for acute myocardial infarction and stroke [5]. Stroke is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The exact relation between stroke and rhinosinusitis is still not fully elucidated. The predominant theory suggests that the anatomic proximity of the paranasal sinuses and internal carotid artery or brain could lead to the expansion of the inflammation of the sinuses to the intracranial vasculature. Other theories include inflammation-mediated emboli or spasms of cerebral arteries, adverse reactions to medicine, or complications following sinus surgery [6,7].

In the present study, our objective was to evaluate the association between rhinosinusitis and cardiovascular diseases, especially stroke, through a literature review.

Review

Material and methods

This systematic review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. Eligible articles were identified by a search of the PubMed bibliographical database for the period from September 2001 up to February 2022. The study protocol was agreed upon by both co-authors. The search strategy included the following keywords (“rhinosinusitis” OR “chronic rhinosinusitis”) AND (“stroke” OR “ischemic stroke”). Language restrictions were applied (only articles in English were considered eligible); two investigators (AMP and AM), working independently, searched the literature and extracted data from each eligible study. Reviews were not eligible, while all prospective and retrospective studies, as well as case reports, were eligible for this systematic review. Manuscripts that did not state the names of the authors were excluded. In addition, we checked all the references of relevant reviews and eligible articles that our search retrieved, so as to identify potentially eligible conference abstracts. Titles of interest were further reviewed by abstract. Finally, reference lists of eligible studies were manually assessed in order to detect any potentially relevant article (“snowball" procedure).

Results

Article Selection and Study Demographics

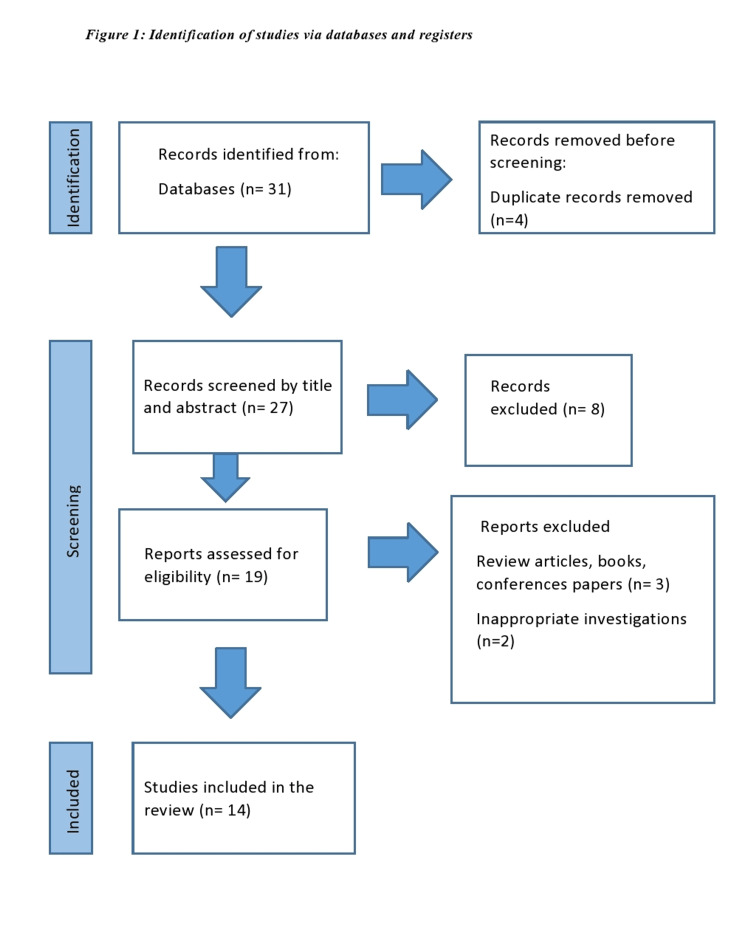

Following the screening of titles and abstracts, the search strategy retrieved 27 articles that were evaluated for full-text evaluation. Fourteen studies were deemed eligible and were included in the analytic cohort. Overall, these studies encompass a total of 1,006,338 patients that have been included in this systematic review. The search strategy is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the search strategy.

Main Findings

Table 1 summarizes findings from the articles reporting a correlation between rhinosinusitis and stroke.

Table 1. Correlation between rhinosinusitis and stroke.

CRS: chronic rhinosinusitis, HR: hazard ratio, L-M: Lund-Mackay

| Author | Year | Type of Study | n | Results |

| Wu et al [1] | 2012 | Prospective cohort study | 268277; Patients: 53656; Controls: 214624 | (1) Patients with rhinosinusitis were more likely to suffer strokes than controls (adjusted HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.28-1.50; (2) The HR of stroke was 1.39 (95% CI, 1.28-1.51) for ARS patients, and 1.34 (95% CI, 1.04-1,74) for CRS patients. |

| Kang et al. [2] | 2013 | Population-based cohort study | 63384; Patients: 15846; Controls: 47538 | subjects with CRS were more likely than comparison subjects to have a diagnosis of ischemic stroke during the 5-year follow-up period (HR 1⁄4 1.34, 95% CI 1⁄4 1.18–1.53) |

| Lee et al. [3] | 2018 | National cohort study | 114795; Patients: 22959; Controls: 91836 | Significantly increased HR for hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke in the CRS patients compared to controls (adjusted HR = 2.43, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.10– 2.80 for hemorrhagic stroke; adjusted HR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.61–1.92 for ischemic stroke) |

| Stryjewska‐Makuch et al. [4] | 2021 | Retrospective case-control study | 238 Patients: 163; Controls: 75 | Inflammatory sinus lesions of moderate or high severity were more often observed in patients with stroke than in the control group and they mainly involved the ethmoid sinuses. |

| Perez Barreto et al. [6] | 2000 | Case report | 4 | Large vessel stroke involving the internal carotid artery territory in patients with extensive disease of the sphenoid and other sinuses |

| Righini et al. [7] | 2009 | Case report | 1 | A 28-year-old woman with acute sphenoid sinusitis complicated by ischemic stroke in the left caudate nucleus, lentiform nucleus, and posterior part of the internal capsule. |

| Rochat et al. [8] | 2001 | Case report | 1 | A 10-year-old girl with severe acute pansinusitis and ischemic stroke in the right lentiform nucleus and the anterior part of the right internal capsule |

| Fabre et al. [9] | 2018 | Case report | 1 | middle cerebral artery ischemic stroke secondary to inflammatory arteritis of the left internal carotid artery in a context of bilateral acute maxillary sinusitis in a 6-year-old girl. |

| Davison et al. [10] | 2021 | Case report | 1 | acute stroke in the setting of severe acute pansinusitis in a 9-year-old male |

| Fu et al. [11] | 2015 | Case report | 1 | Basilar artery territory stroke secondary to invasive fungal sphenoid sinusitis in a 38-year-old man |

| Jeon et al. [12] | 2022 | Longitudinal follow-up study | 32760; Patients: 6552; Controls: 26208 | (1) Significantly increased risk for stroke in CRS patients compared to controls; (2) Significantly higher HR of stroke in the absence of nasal polyps than in the presence of nasal polyps |

| Kim et al. [13] | 2019 | Population-based, long-term longitudinal study | 44286; Patients: 14762; Controls: 29524 | HR of stroke in patients with CRS versus controls: 1.16 (95% CI, 1.08-1.24) |

| Rosenthal et al. [14] | 2016 | Retrospective study | 173 | Incidental paranasal sinusitis (MRI) was strongly associated with cerebrovascular disease (p<0,001) |

| Puz et al. [15] | 2021 | Retrospective study | 311 | Significant difference in the neurological status of stroke patients between mild and severe L-M score (p = 0.02) |

Six case reports which included nine patients were selected for this systematic review [6-11]. The majority of them presented cases of ischemic stroke as a complication of acute rhinosinusitis. Four cases (44%) concerned young children [6,8-10] and the rest five cases (56%) concerned adults, with patient ages ranging from 28 to 62 years [6,7,11]. Two patients (22%) suffered from diabetes, which is thought not only to predispose to paranasal sinus infection but also to be responsible for the asymptomatic nature of this infection and consequent late diagnosis [9,11]. The sphenoid sinus was involved in almost all patients (89%). One patient (11%) was diagnosed with acute pansinusitis [8], three patients (33%) had acute isolated sphenoid sinusitis [6,7,11], while Fabre et al. were the first to report a case of stroke secondary to acute maxillary sinusitis [9]. According to the magnetic resonance images, which confirmed the ischemic strokes, most of them were secondary to narrowing or occlusion of the internal carotid artery adjacent to involved paranasal sinuses, suggesting inflammatory arteritis [6,7,9]. Only Davison et al. described a case of acute sinusitis presenting as stroke with ischemic changes in MR imaging, however, without any evidence of thrombosis in the major vessels on MRI, MRA, or CT [10]. None of the patients demonstrated venous pathology. All patients were successfully treated by endoscopic surgery and broad-spectrum antibiotics, with the exception of a diabetic man with invasive mucormycosis that led to a basilar artery territory stroke and subsequent death [11].

The rest of the collected studies were cohort studies that investigated the association between rhinosinusitis and the incidence of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Although different methodological approaches were followed, all of them concluded that CRS can be considered a relevant risk factor for stroke. In greater detail, a recent longitudinal follow-up study proved that CRS patients had a significantly higher prevalence of stroke compared to controls, even after adjusting for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, which also is in agreement with the results of Lee et al [3,12]. Notably, the hazard ratio (HR) of stroke was significantly higher in patients without nasal polyps than in those with nasal polyps [12]. Wu et al. also compared the risk of stroke between CRS patients and controls and found that patients had a 1.39-fold increased risk during a three-year follow-up period [1]. The HR remained significantly higher after adjusting for demographic characteristics and medical comorbidities [1]. Significantly increased HR of stroke in the CRS group compared to controls, regardless of sociodemographic factors was also observed in two other studies (HR:1.16 and 1.33 respectively) [2,13]. These results are consistent with another large national cohort study with a 10-year follow-up period which, interestingly, highlights that the occurrence of stroke increased in the course of time following CRS, especially within one year [3]. Based on this finding, the authors pointed out the significance of early and aggressive CRS treatment in the prevention of stroke and its complications [3]. Moreover, the same study reported an increased risk of both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in CRS patients [3], whereas Kang et al. observed a statistically increased risk of ischemic stroke only in patients with CRS [2]. This disparity could be explained due to different follow-up periods, since the slow and gradual evolution of CRS may demand a longer time for intracranial complications to occur [3]. Furthermore, the number of intracranial hemorrhage cases is quite small, which could create an artifact of inadequate statistical power [2].

The remaining studies investigated the association between incidental paranasal sinusitis and cerebrovascular disease. For example, a strong association was proved by Rosenthal et al., who studied a random sample of magnetic resonance (MR) brain scans (p<0,001) [14]. Another case-control study demonstrated that patients with ischemic stroke who underwent thrombectomy presented chronic inflammation of the paranasal sinuses with the same rate as atrial fibrillation and more frequently than diabetes and smoking [4]. More specifically, lesions of moderate or high severity which mainly involved the ostiomeatal complex, ethmoid, frontal and maxillary sinuses, were more frequently encountered in stroke patients than in controls [4]. In addition, older patients with stroke had larger lesions. On the contrary, Lee et al. showed that CRS patients under 60 years of age were at greater risk of stroke [3]. Moreover, the impact of CRS on the short-term prognosis in stroke patients has also been confirmed [15]. The neurological status in patients with mild signs of CRS, as evaluated with CT scans, was significantly better than in those with moderate or severe lesions. As a result, the authors proposed the CT features of CRS as an early prognostic tool for patients with ischemic stroke. Notably, when moderate or severe CRS is diagnosed, intensive maximal medical therapy or interventional treatment should be started as early as possible, as this may improve the short-term efficacy of endovascular treatment of patients with stroke [15].

Furthermore, it can be implied by the literature that there is an association between ARS and stroke based on the findings by Wu et al. [1] and the case reports reviewed in this article.

Finally, two studies demonstrated that CRS patients had a significantly higher prevalence of ischemic heart disease as well [12,13].

Discussion

Despite recent improvements in antibiotic therapies and surgical interventions, intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis can lead to disabilities in 25% of cases and even death in 10% [16,17]. All evidence supports that stroke may be considered a serious complication too, according to our literature review. The exact mechanism which explains the relation between rhinosinusitis and stroke is likely to be heterogeneous and has not been fully understood yet. Several possible explanations have been implicated to contribute to this association.

Firstly, some cases of sinusitis-related stroke were subsequent complications of intracranial infection, which can lead to cerebral vasculitis and brain blood flow disruption through direct spread into intracranial vessels [18]. Meningitis, for example, has been associated with cerebral ischemia, probably through vasospasm caused by inflammatory cytokines [19]. The association between acute infection and stroke is not dependent on particular microbial agents but it is a result of the inflammatory response to infection, which induces a procoagulant state [18].

Secondly, there is close anatomical proximity between the sinuses and the intracranial cavity, which are separated from each other by a thin bony wall [6,20]. In fact, the internal carotid artery lies immediately adjacent to the approximately 0.1-mm thin lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus [6,21]. Cases of sphenoid sinusitis complicated with carotid and basilar arteries occlusion have been described in the literature [1,6]. For example, Perez Barreto et al. presented a case of internal carotid artery stroke in a patient with extensive disease of the sphenoid sinus [6]. Bony dehiscence and true prolapse of the internal carotid artery into not only the sphenoid sinus but also into the posterior ethmoid cells are common, inducing direct contact of sinus mucosa with the artery [6]. Moreover, ethmoid cells, which are lined with a large mucosal surface relative to their volume, are often vascularized by anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries with the absence of bone canals, facilitating direct contact of the mucosa with the arteries [4]. Contiguous inflammation of the carotid artery canal through infratemporal (pericarotid) venous thrombosis extending to the cavernous sinus due to maxillary sinusitis has also been described [9].

The anatomical proximity and direct contact of the paranasal sinus mucosa with vessels can lead to perivascular inflammatory reactions [1], which can be of either infectious or non-infectious etiology [2]. For example, cases of septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein that lead to cerebral infarction in CRS patients have been reported (Lemierre’s syndrome) [22]. Intracranial hemorrhage or cerebral infarction can also be caused by infectious aneurysms [23]. On the other hand, high local concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines have been found in retained sinus fluids and sinus mucosa of patients with sinusitis [24,25]. Inflammation is thought to play a key role in atherosclerotic initiation, plaque rupture, thrombosis, and consequently stroke [1]. It has been demonstrated by many authors that inflammation adversely affects the integrity and function of endothelial cells [18]. Several inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1, interleukin-6, interleukin-17, or C-reactive protein are responsible for immune and subendothelial smooth muscle cell activation, accelerating atherogenesis [18], thereby, leading to premature atherosclerosis with reduced cerebral flow and nerve tissue perfusion [26]. These inflammatory cytokines may also cross-activate the coagulation pathway by triggering the thrombin coagulation system and upregulating the fibrinolytic inhibiting protein, which leads to a higher chance of thrombus formation and thromboembolic events. In particular, interleukin-1 may result in perivascular inflammation and progression of internal carotid artery thrombosis, while interleukin-17, particularly in combination with tumor necrosis factor α, is thought to have a proinflammatory, procoagulant, and prothrombotic effect on blood vessels [1,18]. Besides, bacterial antigens and activated leukocytes can directly activate platelets [27]. Lipopolysaccharides of Gram-negative bacteria, which are very common in older adults with sinusitis, have been reported to induce stroke in rats [28]. In addition, inflammation of vessel walls can result in aneurysms and wall rupture accompanied by local hemorrhage [28].

The fact that sinusitis and cardiovascular diseases share some common predisposing factors could also explain their association. For instance, smoking is a risk factor for both conditions. It disturbs the mucociliary clearance of the sinuses but also contributes to a stroke mortality rate of approximately 15%, with a dose-response relationship [29]. Only three cohort studies adjusted their results for tobacco use [2,12,14]. There are other comorbidities of sinusitis that serve as nontraditional cardiovascular risk factors as well, such as allergy or asthma [2]. These conditions, except for being intimately associated with CRS, have been reported to increase the risk of stroke [2]. Other comorbidities that are suggested to be related to both CRS and stroke include gastroesophageal reflux and sleep difficulties [2]. Furthermore, sinusitis is thought to serve as a marker of dental and respiratory tract infections, which are frequently encountered in patients with acute ischemic stroke [6]. As a result, the association between sinusitis and stroke could be partly explained as a function of shared predisposing and confounding factors.

Finally, the treatment modalities of sinusitis may sometimes increase the hazard of stroke occurrence. Decongestant drugs, such as sympathomimetics, increase blood pressure and heart rate, which are predominant risk factors for ischemic stroke [30,31]. Decongestants have also been suggested to be related to intracranial hemorrhage [2]. Particularly, a study with a Korean population found that there was a 0.6% to 1.6% exposure rate of phenylpropanolamine which has been connected with hemorrhagic stroke [32]. Likewise, a case report described an arteriovenous malformation rupture that led to intracranial and subarachnoid hemorrhage in a decongestant user [33]. In addition, subarachnoid hemorrhage is a rare but disturbing sequela of endoscopic sinus surgery [2].

In nearly half of the collected cohort studies the CRS diagnosis was based on inflammatory lesions apparent on sinus imaging, either with CT or MRI scans [4,14,15]. The lack of data on the history of sinus complaints, severity, disease status, and possible treatment in accordance with the EPOS 2020 guidelines [34] limits these studies. Moreover, the accuracy of imaging modalities, especially MRI for sinonasal disease, is questionable. Lastly, most studies included in this review were case reports and retrospective cohorts. Therefore, the underlying mechanisms which can better explain the association between sinusitis and stroke could not be directly examined and analyzed.

Conclusions

The present systematic review investigated the interesting and lesser-known association between sinusitis and stroke. Our results suggest that clinicians should be aware of the increased risk of stroke when dealing with patients with acute or chronic rhinosinusitis. Several potential explanations have been proposed for this relation, but larger prospective studies and trials are required to figure out further issues, such as whether this relationship is really causal, the pathomechanism of this association, how the severity of the disease contributes to the risk of stroke, which preventive strategies can be developed, and if there is an impact of sinusitis on the progression and therapy of the acute phase of stroke.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Risk of stroke among patients with rhinosinusitis: a population-based study in Taiwan. Wu CW, Chao PZ, Hao WR, Liou TH, Lin HW. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:278–282. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chronic rhinosinusitis increased the risk of stroke: a 5-year follow-up study. Kang JH, Wu CS, Keller JJ, Lin HC. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:835–840. doi: 10.1002/lary.23829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chronic rhinosinusitis increases the risk of hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke: A longitudinal follow-up study using a national sample cohort. Lee WH, Kim JW, Lim JS, Kong IG, Choi HG. PLoS One. 2018;13:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inflammatory lesions in the paranasal sinuses in patients with ischemic stroke who underwent mechanical thrombectomy. Stryjewska-Makuch G, Glück J, Niemiec-Urbańczyk M, Humeniuk-Arasiewicz M, Kolebacz B, Lasek-Bal A. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2021;131:326–331. doi: 10.20452/pamw.15848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sex differences in stroke incidence, prevalence, mortality and disability-adjusted life years: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Barker-Collo S, Bennett DA, Krishnamurthi RV, et al. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45:203–214. doi: 10.1159/000441103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinusitis and carotid artery stroke. Perez Barreto M, Sahai S, Ameriso S, Ahmadi J, Rice D, Fisher M. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:227–230. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An acute ischemic stroke secondary to sphenoid sinusitis. Righini CA, Bing F, Bessou P, Boubagra K, Reyt E. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19924653/ Ear Nose Throat J. 2009;88:0–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinusitis and ischemic stroke. Rochat P, von Buchwald C, Wagner A. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11721511/ Rhinology. 2001;39:173–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxillary sinusitis complicated by stroke. Fabre C, Atallah I, Wroblewski I, Righini CA. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018;135:449–451. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Complicated acute frontal sinusitis in a child presenting with acute ischemic stroke. Davison WL, Gudis DA. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;143:110631. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2021.110631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basilar artery territory stroke secondary to invasive fungal sphenoid sinusitis: a case report and review of the literature. Fu KA, Nguyen PL, Sanossian N. Case Rep Neurol. 2015;7:51–58. doi: 10.1159/000380761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Increased risk of cardiovascular diseases in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: a longitudinal follow-up study using a national health screening cohort. Jeon YJ, Lee TH, Joo YH, Cho HJ, Kim SW, Park B, Choi HG. Rhinology. 2022;60:29–38. doi: 10.4193/Rhin21-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Relationship of chronic rhinosinusitis with asthma, myocardial infarction, stroke, anxiety, and depression. Kim JY, Ko I, Kim MS, Kim DW, Cho BJ, Kim DK. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Incidental paranasal sinusitis on routine brain magnetic resonance scans: association with atherosclerosis. Rosenthal PA, Lundy KC, Massoglia DP, Payne EH, Gilbert G, Gebregziabher M. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:1253–1263. doi: 10.1002/alr.21824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prognostic role of chronic rhinosinusitis in acute ischemic stroke patients undergoing mechanical thrombectomy. Puz P, Stryjewska-Makuch G, Żak A, Rybicki W, Student S, Lasek-Bal A. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4446. doi: 10.3390/jcm10194446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Intracranial complications of sinusitis. Giannoni CM, Stewart MG, Alford EL. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:863–867. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199707000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Intracranial complications of sinusitis: a pediatric series. Giannoni C, Sulek M, Friedman EM. Am J Rhinol. 1998;12:173–178. doi: 10.2500/105065898781390127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Risk of stroke among patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Wattanachayakul P, Rujirachun P, Ungprasert P. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28:1185–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerebrovascular involvement in the acute phase of bacterial meningitis. Ries S, Schminke U, Fassbender K, Daffertshofer M, Steinke W, Hennerici M. J Neurol. 1997;244:51–55. doi: 10.1007/s004150050050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isolated sphenoid sinusitis complicated by meningitis and multiple cerebral infarctions in a renal transplant recipient. Steadman CD, Salmon AH, Tomson CR. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:242–244. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anatomical variations of the nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses: a systematic review. Papadopoulou AM, Chrysikos D, Samolis A, Tsakotos G, Troupis T. Cureus. 2021;13:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerebral infarct and meningitis secondary to Lemierre's syndrome. Bentham JR, Pollard AJ, Milford CA, Anslow P, Pike MG. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30:281–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mycotic aneurysm and cerebral infarction resulting from fungal sinusitis: imaging and pathologic correlation. Hurst RW, Judkins A, Bolger W, Chu A, Loevner LA. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11337328/ AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:858–863. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis: inflammation. Van Crombruggen K, Zhang N, Gevaert P, Tomassen P, Bachert C. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:728–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Localization of IL-1 beta mRNA and cell adhesion molecules in the maxillary sinus mucosa of patients with chronic sinusitis. Tokushige E, Itoh K, Ushikai M, Katahira S, Fukuda K. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1245–1250. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199410000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Katsiari CG, Bogdanos DP, Sakkas LI. World J Transl Med. 2019;8:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Common infections and the risk of stroke. Grau AJ, Urbanek C, Palm F. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:681–694. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroke risk factors prepare rat brainstem tissues for modified local Shwartzman reaction. Hallenbeck JM, Dutka AJ, Kochanek PM, Siren A, Pezeshkpour GH, Feuerstein G. Stroke. 1988;19:863–869. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.7.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dose-response relationship between cigarette smoking and risk of ischemic stroke in young women. Bhat VM, Cole JW, Sorkin JD, et al. Stroke. 2008;39:2439–2443. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hypertensive crisis and end-organ damage induced by over-the-counter nasal decongestant abuse. Buysschaert I, Van Dorpe J, Dujardin K. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:3114. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Effect of oral pseudoephedrine on blood pressure and heart rate: a meta-analysis. Salerno SM, Jackson JL, Berbano EP. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1686–1694. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phenylpropanolamine contained in cold remedies and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Yoon BW, Bae HJ, Hong KS, et al. Neurology. 2007;68:146–149. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000250351.38999.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pseudoephedrine-induced hemorrhage associated with a cerebral vascular malformation. Baker SK, Silva JE, Lam KK. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32:248–252. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100004066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Executive summary of EPOS 2020 including integrated care pathways. Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, et al. Rhinology. 2020;58:82–111. doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]