ABSTRACT

YciF (STM14_2092) is a member of the domain of unknown function (DUF892) family. It is an uncharacterized protein involved in stress responses in Salmonella Typhimurium. In this study, we investigated the significance of YciF and its DUF892 domain during bile and oxidative stress responses of S. Typhimurium. Purified wild-type YciF forms higher order oligomers, binds to iron, and displays ferroxidase activity. Studies on the site-specific mutants revealed that the ferroxidase activity of YciF is dependent on the two metal binding sites present within the DUF892 domain. Transcriptional analysis displayed that the ΔcspE strain, which has compromised expression of YciF, encounters iron toxicity due to dysregulation of iron homeostasis in the presence of bile. Utilizing this observation, we demonstrate that the bile mediated iron toxicity in ΔcspE causes lethality, primarily through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Expression of wild-type YciF, but not the three mutants of the DUF892 domain, in ΔcspE alleviate ROS in the presence of bile. Our results establish the role of YciF as a ferroxidase that can sequester excess iron in the cellular milieu to counter ROS-associated cell death. This is the first report of biochemical and functional characterization of a member of the DUF892 family.

IMPORTANCE The DUF892 domain has a wide taxonomic distribution encompassing several bacterial pathogens. This domain belongs to the ferritin-like superfamily; however, it has not been biochemically and functionally characterized. This is the first report of characterization of a member of this family. In this study, we demonstrate that S. Typhimurium YciF is an iron binding protein with ferroxidase activity, which is dependent on the metal binding sites present within the DUF892 domain. YciF combats iron toxicity and oxidative damage caused due to exposure to bile. The functional characterization of YciF delineates the significance of the DUF892 domain in bacteria. In addition, our studies on S. Typhimurium bile stress response divulged the importance of comprehensive iron homeostasis and ROS in bacteria.

KEYWORDS: Salmonella, stress proteins, DUF892 member, bile, reactive oxygen species, YciF, biochemistry, metal binding, stress response

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is an enteric pathogen that causes non-typhoidal Salmonellosis or gastroenteritis. The global burden of gastroenteritis caused by non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) is substantial (1). S. Typhimurium can also be invasive to usually sterile sites such as blood, and cause bacteremia in immunocompromised individuals (2–4). The increasing antibiotic resistance in S. Typhimurium has resulted in formation of multiple drug-resistant strains and presents a significant global health challenge (5). Infection and survival within host is aided by myriad of stress response genes responsive to various environmental stressors. Bile is one such stressor with antibacterial activity. As a pathogen, Salmonella enterica manifests an extreme example of bile resistance because it can colonize the hepatobiliary tract during systemic infection and the gallbladder during chronic infection (6). Bile is a potent antimicrobial agent that causes cell membrane damage, protein denaturation, lipid peroxidation, secondary structure formation in RNA, and DNA damage. In addition, it can also chelate important minerals such as calcium and iron (6, 7). Studies have reported that bile can lead to oxidative stress within the cells (8, 9). Although the RpoS mediated general stress response pathway is critical to survival of S. Typhimurium in bile, an RpoS-independent pathway also exists which is mediated by CspE (6, 10). CspE belongs to the family of cold shock proteins and has significance in diverse stress response pathways as it is an RNA chaperone that stabilizes the transcripts of several stress response proteins (11). In S. Typhimurium 14028s, it is critical for tolerance to bile stress and deletion of this gene leads to hypersensitivity to bile (10).

Protein families are annotated as “domain of unknown function” (DUF) when they have no member with an experimentally determined function. DUF892 is functionally uncharacterized and belongs to the ferritin-like superfamily (12). Ferritins maintain the supply of iron to the cells. Besides iron storage, ferritins help in protection against free radicals generated due to Fenton reaction when there is iron excess (13, 14). For Salmonella, iron is a crucial resource; however, its bioavailability is a significant challenge and excess is hazardous (15). S. Typhimurium encounter an iron-restricted environment inside the host as a result of nutritional immunity utilized by the host (15, 16). In response, the bacteria also have evolved effective iron acquisition approaches such as production of siderophores to capture iron (16, 17). While the problem associated with ferric ion is that it has low solubility in physiological conditions, ferrous ions can cause cytotoxicity. Excess ferrous ions activate dioxygen, leading to formation of intermediate reactive species that results in generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and damage proteins and DNA (18–20). Therefore, it is important for cells to strictly regulate the intracellular iron content.

YciF is an all α-helical protein containing a single domain DUF892. As a member of domain of the unknown function (DUF892) family, YciF is functionally uncharacterized, as is the DUF892 domain. It contains two metal binding sites as revealed by the crystal structure (21, 22). In S. Typhimurium, there have been few studies that suggest YciF is a stress response protein. YciF has been found to be highly upregulated in osmotic shock and bile stress (10, 23, 24). In bile stress, it is shown to work downstream of CspE (10). Although YciF has been described as a bacterial stress response protein, the biochemical function as well as the intracellular mechanism of action is unknown.

Previously, our lab reported that overexpression of the uncharacterized protein YciF confers survival advantage to bile sensitive S. Typhimurium cspE deletion strain (ΔcspE) (10). We chose to investigate the significance of YciF and its DUF892 domain in the bile stress response of S. Typhimurium. In this study, YciF and mutants of the metal binding site present in DUF892 domain were purified, characterized biochemically and physiologically. We found that YciF has ferroxidase activity which is compromised when the metal binding site is mutated. To associate the biochemical activity of YciF with the in vivo phenotype, we determined the presence of iron toxicity in the bile treated ΔcspE strain. Furthermore, we show that the high intracellular ROS level in the ΔcspE strain, possibly resulting from bile mediated iron dysregulation, is lowered in the presence of YciF. YciF was also observed to directly rescue the peroxide sensitive phenotype of the ΔcspE strain, highlighting its role in mitigating deleterious effects of ROS.

RESULTS

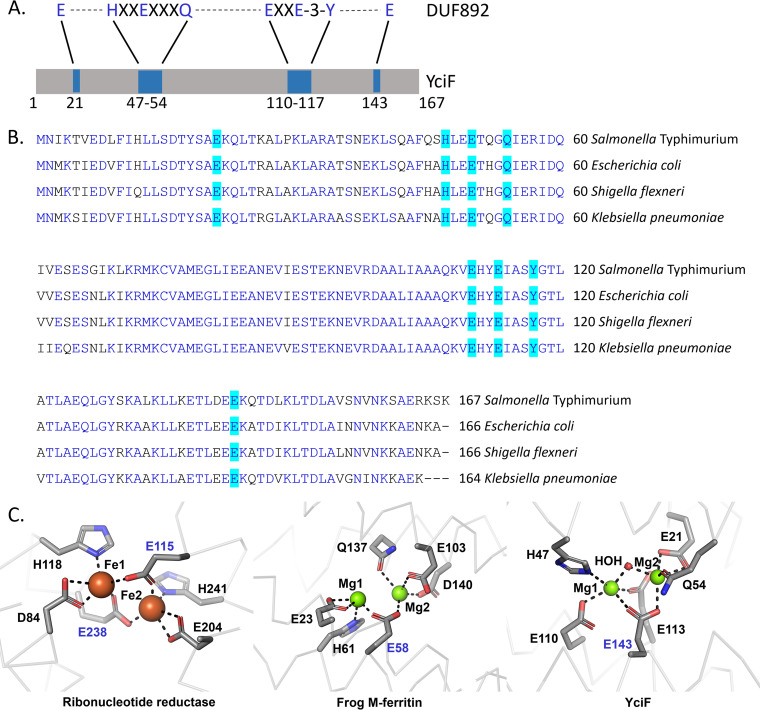

YciF contains diiron sites within the DUF892 domain.

S. Typhimurium encoded YciF has a single ferritin-like domain, DUF892 (Fig. 1A). However, the functional significance of this domain remains obscure as members of the DUF892 family are uncharacterized. The DUF892 domain homologs are found across members of Gammaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and even Archaeabacteria (Fig. S1). S. Typhimurium YciF shows high-sequence identity with other members of Enterobacteriaceae (>80%) (Fig. 1B). The DUF892 domain of YciF comprises two metal binding sites identical to diiron center. The putative metal binding sites are more conserved among members of Enterobacterales (Fig. S1). The diiron center containing proteins are of several types, characterized by the presence of glutamate and histidine as part of ExxH motif and two additional glutamates inside a four-helix bundle (12). Diiron proteins such as ribonucleotide reductases, bacterioferritin have two carboxylates as bridging ligand whereas ferritins have a single carboxylate ligand for the diiron sites (12, 25). Similar to ferritins, YciF has E143D as the single carboxylate bridging ligand (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

(A) YciF contains a single ferritin-like domain, DUF892, that spans almost the entire length of the protein. (B) Multiple sequence alignment using clustal omega shows that YciF is highly conserved across Enterobacteriaceae. The residues of DUF892 domain involved in metal ion-coordination are highlighted in turquoise. (C) Comparison of diiron centers of ribonucleotide reductase (PDB.id: 1PFR), frog M-ferritin (PDB. Id: 1MFR), and YciF (PDB.id: 4ERU). E143 and E58 are the single bidentate residues for YciF and frog M-ferritin, respectively, whereas ribonucleotide reductase has two carboxylate bridging residues (E115 and E238).

YciF and its metal binding sites mutants form higher order oligomeric complex.

S. Typhimurium YciF crystal structure has two metal binding sites (22). To understand the role of DUF892 domain that contains the expected diiron site, single point mutants Q54A and E113Q were generated targeting the two metal binding sites, M2 and M1, respectively. A third mutant E143D was made that would disrupt coordination of both the metal binding sites as E143 is the bridging ligand according to the YciF crystal structure (Fig. S2). YciF and the mutants (Q54A, E113Q, E143D) were purified using the streptactin affinity resin and subjected to SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). The stability of the mutants was determined using thermal shift assay. E113Q and Q54A had almost similar melting temperature as YciF whereas E143D had decreased melting temperature. However, E143D was stable enough as 53.5°C is still substantially higher than the physiological temperature of 37°C (Fig. S3). Members of the ferritin superfamily are known to form higher order oligomeric complexes (13, 26, 27). To investigate the possibility of YciF forming higher order oligomer, gradient Native PAGE was performed. YciF and the mutants had electrophoretic mobility corresponding to that of 150 kDa ϒ-globulin (Fig. 2B). YciF was subjected to SEC-MALS to determine the precise molecular weight of the oligomeric complex that assumes a 120 kDa complex under native conditions (Fig. S4). Using the SEC-MALS data as reference, analytical size exclusion chromatography was performed to compare the oligomeric status of YciF and its mutants. All three mutants formed oligomeric complexes that are comparable to the unmodified YciF (Fig. 2C). The approximate molecular weight of the proteins was calculated using protein with standard masses. The SEC data correlates with the SEC-MALS analyses wherein wild-type (WT) YciF oligomer had an estimated molecular mass of 109 kDa (±3 kDa). Q54A, E113Q and E143D substitutions in YciF form oligomers corresponding to 104, 100, and 103 kDa, respectively (Fig. 2D).

FIG 2.

S. Typhimurium YciF and its metal binding sites mutants form higher order oligomers. (A) 12.5% SDS-PAGE profile of Strep II tagged YciF, Q54A, E113Q, and E143D. Monomeric YciF and its mutants have a molecular weight of approximately 20 kDa. (B) 4% to15% gradient native PAGE profile of YciF, Q54A, E113Q, and E143D. (C, D) Analytical size exclusion chromatography to determine the apparent molecular weight of YciF and its mutants. Purified proteins were subjected to Superdex S-200 column. Molecular weight standard was run on the same column maintaining similar elution conditions. The table inside represents the molecular mass calculated from linear regression equation.

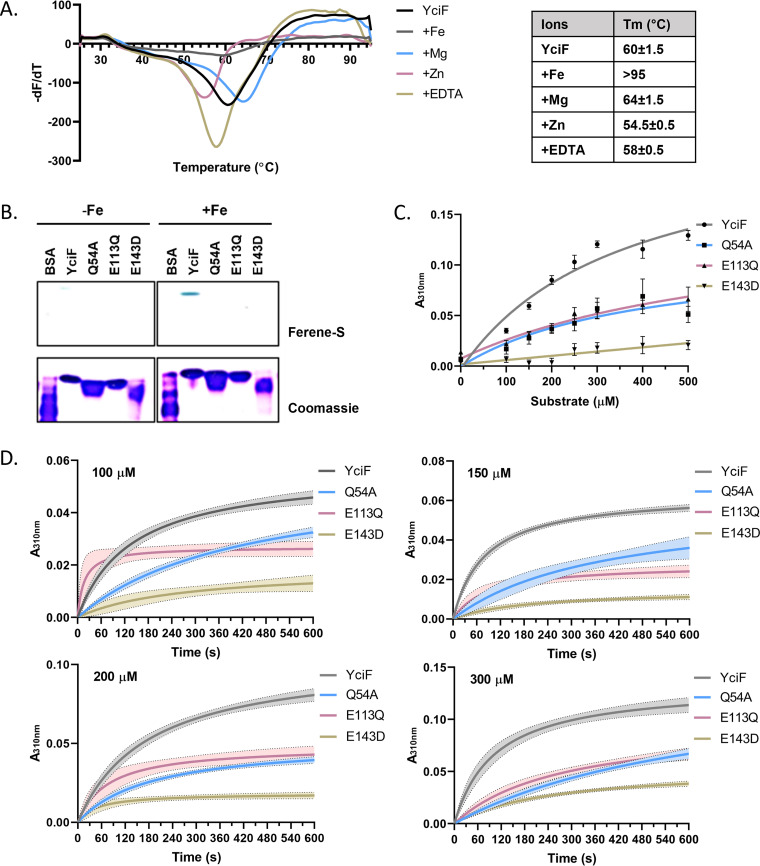

YciF interacts with iron and exhibits ferroxidase activity.

The domain architecture of YciF suggests that it could bind iron. However, in the crystal structure, magnesium ion occupies the metal binding sites (22). Therefore, thermal shift assay was performed to identify the native ligand of the protein. In the presence of Mg2+, there was a moderate increase in melting temperature by 4°C while addition of Zn2+ marginally destabilized the protein, resulting in lowered melting temperature by ~5°C (Fig. 3A). A distinctive melt curve was obtained in the presence of iron where no derivative peak was observed until 95°C suggesting that melting temperature could be higher than 95°C as has been observed in case of ferritin (28–31) or the protein was stable until aggregating temperature. No significant alteration was observed in melting temperature in the presence of metal chelator EDTA, indicating that metal ion is unlikely to be a cofactor for the protein (Fig. 3A). For comparison of iron incorporation into YciF, Q54A, E113Q, and E143D, protein samples were incubated with iron and subjected to Native PAGE. Gel was stained with Ferene-S staining solution to detect iron bound to protein. No bound iron was detected in protein in the absence of incubation with iron. At subsaturating concentration of iron, YciF was able to bind and retain the iron whereas the mutants did not (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

S. Typhimurium YciF binds to iron and displays ferroxidase activity. (A) Thermal shift assay was performed to determine the native ligand. 10 μg YciF was incubated with 200 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, MgSO4, ZnCl2, and EDTA. The table represents the melting temperature (Tm). (B) Comparison of iron binding of YciF and its metal binding sites mutants. Purified proteins were incubated with 200 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 and subjected to native PAGE followed by staining with Ferene-S and Coomassie brilliant blue. BSA was used as negative control. (C) Determination of ferroxidase activity of YciF and the mutants at different concentrations of (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2. Formation of ferric ion was measured at 310 nm. (D) Kinetic comparison of ferroxidase activity of YciF, Q54A, E113Q, E143D. (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 was added at different concentrations and absorbance at 310 nm was measured for 600 s at 30-s interval. Values were blanked against no protein control to correct for auto-oxidation of ferrous ion. Graphs were plotted using nonlinear regression. The data are representative of three independent protein preparations.

As the diiron center of YciF is similar to ferritin, we decided to study the ferroxidase activity. The ferroxidase center catalyzes ferrous ions and releases the ferric products which can be measured at absorbance wavelength of 310 nm. Initial optimization of conditions for ferroxidase assay was performed at different pH, buffers, and protein concentrations (Fig. S5A to C). Oxidation of ferrous ion to ferric ion was faster in the presence of YciF than the auto-oxidation of ferrous ion. Oxidation of different concentrations of Mohr’s salt by YciF was monitored aerobically at 310 nm. Q54A and E113Q with mutations in the M2 and M1 sites, respectively, had compromised activity compared to YciF while E143D that had mutation in the bridging amino acid did not display any significant ferroxidase activity (Fig. 3C). Ferroxidase reaction progression was measured kinetically at 30-s intervals wherein the result corroborated with the substrate titration data (Fig. 3D). A colorimetric method that utilizes Ferene-S as a ferrous ion-specific chromogen was also used to determine the ferroxidase activity of YciF. Loss of ferrous ion due to catalytic activity of YciF led to decrease in absorbance at 590 nm. Notably, all the three mutants displayed reduced activity (Fig. S5D).

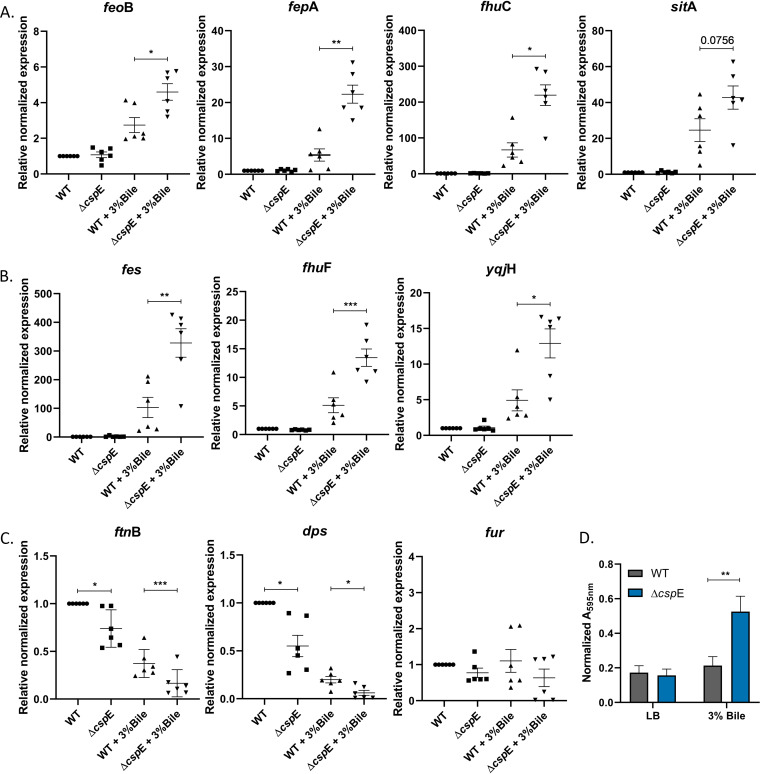

The ΔcspE strain shows dysregulation of iron homeostasis genes upon bile treatment.

Previously, our laboratory had reported that the bile sensitive phenotype of ΔcspE could be rescued by overexpressing YciF; however, the mechanisms were not studied (10). Therefore, we wanted to elucidate the underlying mechanism of function of the ferroxidase activity of YciF during bile stress response. As ferroxidase activity is known to be primarily associated with mitigating iron toxicity within bacterial cells, we investigated whether there was any iron imbalance in the ΔcspE strain possibly resulting from bile treatment. For this, transcript levels of three different categories of iron homeostasis genes involved in uptake of iron, intracellular release of iron, and iron storage were analyzed. fepA is required for uptake of ferri-enterobactin complex into the cell while ferrous ion can directly pass through feoB and sitA. fhuC is a ferri-hydroxamate transporter and its upregulation suggests that bile could lead to iron starvation or act as a cue for the pathogen of an iron-deprived environment such as host gut. S. Typhimurium is mainly known to produce enterobactin and salmochelin type of siderophores (32, 33) whereas hydroxamate siderophores are produced by other microbes in gut but can be utilized by Salmonella through its hydroxamate transporters (34, 35). All the genes involved in uptake of iron were upregulated in bile stress. However, the upregulation of fepA, fhuC, and feoB was significantly higher whereas sitA also showed increased level of transcripts in bile treated ΔcspE compared to the WT strain (Fig. 4A). To understand whether the iron is released from the ferri-siderophore complex into the cytoplasm, transcript levels of fes (ferri-enterobactin utilization), fhuF (ferrioxamine utilization), and yqjH (ferric reductase) were analyzed. Upregulation of these genes in S. Typhimurium WT upon bile treatment suggests that the iron acquired through siderophores is released into the cytoplasm. ΔcspE had higher expression of these genes than the WT strain which was significant (Fig. 4B). ftnB and dps encode proteins that are involved in storage of iron and provide protection against iron-dependent oxidative stress mediated killing (11). Downregulation of both the genes was observed in ΔcspE in untreated condition. A decrease in transcript levels of these genes was observed following bile treatment in WT which substantially reduced further in ΔcspE. Fur is a negative regulator of iron uptake in cells but no change was observed in its transcript levels (Fig. 4C). Next, to confirm iron toxicity in bile treated ΔcspE strain, we performed a Ferene-S dependent colorimetric assay. Bile treatment indeed caused significant increase in total intracellular iron in ΔcspE strain compared to WT (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that there is a considerable surge in intracellular iron content of ΔcspE compared to the WT strain during bile stress.

FIG 4.

qRT-PCR analysis of genes responsible for iron balance in S. Typhimurium and intracellular iron estimation reveal iron disbalance in ΔcspE in the presence of bile. (A) Genes encoding ferri-siderophore transporters: fepA, fhuC are responsible for uptake of Fe3+ while sitA and feoB are involved in Fe2+ uptake. (B) Genes encoding enzymes responsible for intracellular release of iron from siderophores. (C) Genes regulating intracellular iron level: ftnB and dps are iron storage proteins whereas fur is a negative regulator of iron uptake. Cq value of WT strain grown in LB was used to normalize Cq values of all the panels. Data shown as mean ± SEM and is representative of six independent experiments. (D) Quantitation of intracellular iron levels in WT and ΔcspE strains upon bile treatment. Data shown as mean ± SEM and is representative of four independent experiments. P values for qRT-PCR were measured by one-way ANOVA using Sidak's multiple-comparison test. For intracellular iron estimation, P value was calculated using two-way ANOVA using Sidak's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

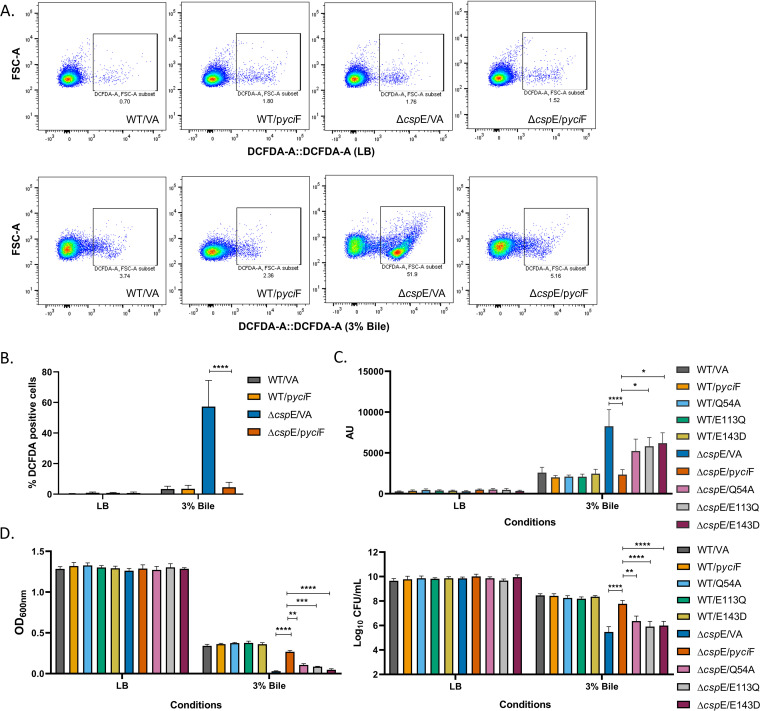

The ΔcspE strain has higher intracellular ROS compared to WT following bile treatment which reduces significantly upon YciF overexpression.

Disruption of intracellular iron homeostasis can lead to production of reactive oxygen species. Bile treatment is also known to cause oxidative stress inside bacterial cells. As ΔcspE showed iron dysregulation, we investigated whether ΔcspE has increased ROS levels, possibly resulting from bile treatment coupled with higher intracellular free iron content. Previously, we had shown that the ΔyciF strain grows similar to WT in the presence of bile; however, overexpression of yciF recues the bile sensitivity of the ΔcspE strain (10). As there is no difference in growth between the WT and ΔyciF in the absence or presence of bile (10), we have restricted to using WT and ΔcspE strain complemented with control vector or YciF (WT and mutants) as our model system of study. Here, we studied the effects of overexpression of YciF which shows ferroxidase activity, in changing intracellular ROS levels. Upon bile treatment, ΔcspE strain containing vector alone indeed showed enhanced ROS generation compared to WT strain containing vector alone. Overexpression of YciF led to decrease in intracellular ROS in ΔcspE and there was significant reduction in DCFDA positive cells compared to vector control. WT strain containing vector alone or pyciF had similar levels of ROS upon bile treatment (Fig. 5A and B). Total ROS levels were compared between bile treated cells overexpressing YciF and the mutants. Bile-treated WT strain showed modest increase in ROS amounts. The ΔcspE strain overexpressing Q54A, E113Q, and E143D showed reduction in ROS levels compared to vector control. Nevertheless, in these strains ROS was still higher compared to YciF overexpression condition (Fig. 5C). We observed that production of ROS was accompanied by cell lethality. Phenotypically, ΔcspE strain overexpressing Q54A, E113Q and E143D mutants were still susceptible to bile stress although YciF significantly rescued the bile sensitive ΔcspE strain.

FIG 5.

YciF combats bile mediated oxidative stress. (A) S. Typhimurium WT and ΔcspE strains overexpressing YciF were grown in absence or presence of 3% bile for 6 h. Cells were stained with DCFDA and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) The percentage DCFDA positive cells based on flow cytometry data. (C) Quantitation of intracellular ROS levels upon 3% bile treatment in strains overexpressing YciF and the metal binding sites mutants using DCFDA staining. Fluorescence was measured using excitation and emission wavelength of 485 nm and 535 nm, respectively. (D) Growth of strains overexpressing YciF and the mutants in absence or presence of 3% bile determined by measuring O.D. at 600 nm. Cells were plated on LB agar post bile treatment and colonies were counted. Data shown as mean ± SEM and is representative of four independent experiments. P values were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using Sidak's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Chelation of iron increases the survival of the ΔcspE strain upon bile treatment.

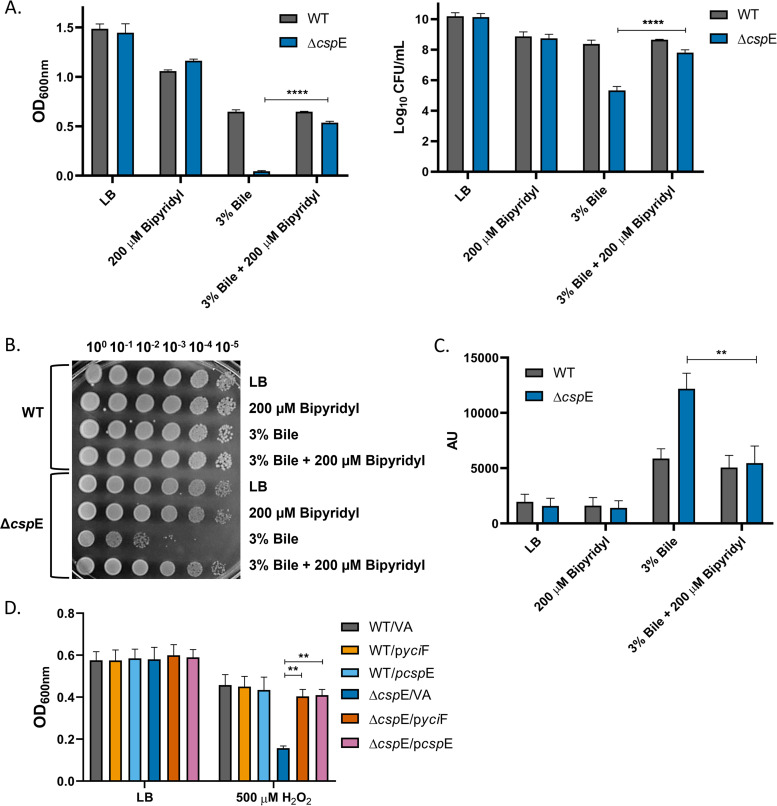

As ΔcspE showed imbalance of transcripts involved in iron homeostasis, we assessed any growth differences between S. Typhimurium WT and ΔcspE strains in the presence of the iron chelator 2,2-bipyridyl. Both the strains had similar growth across different doses of 2,2-bipyridyl (Fig. S6). High levels of intracellular iron and ROS content as a result of bile stress can lead to Fenton reaction and thereby production of hydroxyl radicals that is toxic to the cell (36). CspE is known to be critical for survival of S. Typhimurium 14028s strain in bile stress condition and the ΔcspE strain was highly susceptible to bile mediated killing compared to the WT strain, in agreement to the previous study (10). The WT strain had similar growth in bile irrespective of the absence or presence of 2,2-bipyridyl. However, the severe growth attenuation of ΔcspE observed upon bile treatment was rescued when media was supplemented with 2,2-bipyridyl (Fig. 6A and B). The increase in growth of ΔcspE in the presence of bile upon iron chelation was accompanied with reduction in ROS levels. Bile-treated WT strain showed increased production of ROS; however, no alteration was observed in the ROS amounts in the presence of 2,2-bipyridyl. (Fig. 6C). These results clearly demonstrate that the ΔcspE strain is susceptible to iron mediated killing in the presence of bile and can grow similar to WT strain if excess-free iron is sequestered away. Furthermore, the ΔcspE strain was found to be sensitive to H2O2 compared to the WT and the growth inhibition was overcome when YciF was overexpressed (Fig. 6D).

FIG 6.

Iron chelation reduces ROS and increases the growth of ΔcspE strain in the presence of bile. S. Typhimurium WT and ΔcspE were grown in LB alone and LB containing 200 μM bipyridyl/3% bile/3% bile + 200 μM bipyridyl for 6 h. For H2O2 treatment, the mentioned strains were grown for 3 h. (A) O.D. was measured at 600 nm and cells were plated on LB agar following 3% bile treatment and colonies were counted. (B) WT and ΔcspE strains were spotted onto LB agar plates after 6 h of 3% bile treatment. (C) Cellular ROS levels in absence or presence of 2,2-bipyridyl following 3% bile treatment was quantitated using DCFDA staining. Fluorescence was determined at excitation and emission wavelength of 485 nm and 535 nm, respectively. (D) O.D. was measured at 600 nm after H2O2 treatment. Data shown as mean ± SEM and is representative of four independent experiments. P values were measured by two-way ANOVA using Sidak's multiple-comparison test. **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that CspE is important for bile tolerance as well as biofilm formation in S. Typhimurium (10, 37). Physiologically, these two pathways overlap in gallbladder where formation of biofilm by S. Typhimurium on gallstones plays an important role in protection from bile (38, 39). YciF had been identified as one of the downstream targets of CspE-mediated bile stress response although the yciF deletion strain grows similar to WT in the presence of bile (10). For pathogenic organism such as S. Typhimurium it is advantageous to have several proteins with overlapping substrate specificity and similar function to combat host defense and survive in hostile environments. An example is the hpxF deletion mutant wherein simultaneous deletion of five genes made the strain highly susceptible to oxidative stress (40). The bile stress response mediated by YciF is specific as ΔcspE is compromised in biofilm formation but overexpression of YciF could not rescue this phenotype despite similar planktonic growth (Fig. S7A to C). YciF is highly conserved across Enterobacteriaceae and the DUF892 domain is similar to ferritin. Ferritin forms a 24-mer cage like structure that can store the excess iron channeled into the mineralization sites of protein following the ferroxidase activity (41, 42). The oligomeric structure of Ferritin is critical for the storage of iron (13, 43). In this study, we found that S. Typhimurium YciF is able to form higher order oligomeric complex which is of functional significance as it could allow the protein to store iron. YciF was found to efficiently bind and retain iron and the DUF892 domain was important for iron binding as it contains the putative metal binding sites. We also demonstrated that YciF has ferroxidase activity and, therefore, it possibly has ferritin-like function inside bacteria involving iron detoxification. Although YciF does not form cage like ferritin, its sequestration of excess iron within the helical backbone of oligomer may reduce accessibility of iron to dioxygen, hydrogen peroxide, and superoxide, resulting in a protective cellular function.

We also found that the S. Typhimurium ΔcspE strain displays disruption of expression of iron homeostasis genes when exposed to bile. This was confirmed by transcript level analysis of several genes required for uptake and utilization of iron. While the genes responsible for iron acquisition were significantly upregulated in ΔcspE compared to WT, expression of genes encoding proteins responsible for storage of excess iron such as ftnB and dps were downregulated. dps is a member of RpoS regulon, however, in S. Typhimurium SL1344, presence of cspC or cspE was shown to be required for optimal expression of dps (6, 11). Fluctuation in gene expression when encountering stress conditions is of adaptive importance to the pathogen (6). As bile can chelate iron (44) and act as a signal for iron restricted environment which the pathogen encounters inside host (45), activation of iron acquisition pathway along with repression of iron storage by S. Typhimurium WT is possibly a natural response to bile stress. However, the transcription profile of the ΔcspE strain indicates intracellular iron excess upon bile treatment, which can have deleterious effects by promoting ROS production.

Some studies suggest that there is an overlap between oxidative and bile stress response of S. Typhimurium. For example, the sitABCD and manganese transport system mntH is upregulated in both the stresses (24). In Escherichia coli, bile salts have been shown to activate micF and osmY promoters which are associated with oxidative stress response (8). H2O2 is also generated endogenously by aerobic metabolism (40). Such correlations extend to oxidative stress and iron metabolism as well. S. Typhimurium challenged with H2O2 stress shows significant induction of iron acquisition proteins (46, 47). This could be that several proteins required to mitigate oxidative stress and associated DNA damage such as SodB and DNA glycosylase MutY require iron as cofactor (48–51). In this study, we were able to observe that presence of bile can cause a concurrent generation of ROS in S. Typhimurium, especially in ΔcspE. Consequently, the upregulation of iron acquisition pathway detected in WT strain could also be a response to oxidative stress generated due to bile treatment. However, in the ΔcspE strain, comprised of a cellular milieu with a markedly elevated ROS, the excessive induction of iron acquisition genes can cause toxicity through the Fenton reaction.

Among different reactive oxygen species, the Fenton reaction is possibly the most significant contributor to cell death owing to production of hydroxyl radicals which is considered the most potent reactive oxygen species (52–54). Even among the antibiotics, at least three major classes of bactericidal antibiotics, irrespective of their conventional targets have been found to stimulate formation of hydroxyl radicals which, in turn, cause bacterial killing. On the contrary, bacteriostatic antibiotics did not lead to production of hydroxyl radicals (53, 55). Subsequently, it was found that ROS accumulation is self-amplifying and once a threshold level of ROS is exceeded, cell death is sustained even after removal of initial stressor (56). Bile is also a bactericidal agent and causes impairment of iron balance in the ΔcspE strain. Pretreatment with iron chelator, 2,2-bipyridyl significantly increased survival of ΔcspE during bile stress. This suggests that bile stress in ΔcspE strain causes cell lethality primarily through the Fenton reaction. Consequently, its inhibition by an iron chelator reduced the ROS generated in the presence of bile and restored the growth similar to that of WT strain. Reduction in levels of free iron can confer tolerance to various stress conditions that damage the cell through a common pathway of oxyradical generation. Similarly, the ferroxidase activity and subsequent chelation of iron by YciF overexpressed within the ΔcspE strain can contribute to its survival in the presence of bile or peroxide stress by reducing the Fenton reaction (Fig. 7). Unlike S. Typhimurium SL1344 where cspE and cspC are functionally redundant and the cspEcspC double deletion strain was susceptible to peroxide stress (11), we found that in S. Typhimurium 14028s, cspE deletion strain alone is sensitive to peroxide stress highlighting the strain-specific differences. Some of the previous studies have pointed out the differences between the two strains. For instance, SL1344 is a histidine auxotroph, whereas the 14028s strain has a functional histidine biosynthesis pathway (57). Also, the SL1344 strain has been shown to be more invasive to epithelial cells than the 14028s due to presence of SPI-1 effector SopE (58). Whether the functional redundancy of CspE and CspC in SL1344 and 14028s strains influence infectivity of these strains remains to be studied. In addition, overexpression of YciF significantly enhanced the survival of the cspE deletion strain in the presence of peroxide, supporting its role in combating oxidative damage. Ferritin and Dps proteins are the general defense mechanisms to counter iron toxicity. Although Dps has two biochemical activities, DNA binding and ferroxidase activity, through a separation of function study it was shown that ferroxidase activity is necessary for protection of DNA and survival during oxidative damage in the presence of excess iron (59). It will be interesting to study the role of Dps in bile sensitivity of the ΔcspE strain in future. As YciF could rescue the growth of cspE during bile as well as peroxide stresses, it appears that the ferroxidase activity is an important response to physiologically relevant stressors in Salmonella. Overall, these results underscore the critical role of iron regulation in tolerance to bile mediated oxidative stress and peroxide stress in S. Typhimurium.

FIG 7.

Schematic explaining the role of YciF during bile stress. Bile is known to cause an increase in oxidative stress. This, combined with H2O2 produced endogenously due to aerobic metabolism, will undergo Fenton reaction, upon iron excess causing further sustained increase in ROS. Thus, the ΔcspE strain that shows disruption of iron homeostasis upon bile treatment, is likely to be more susceptible to Fenton reaction compared to the wild-type strain. Higher ROS leads to cell death that can be mitigated by overexpression of YciF which binds to iron and has ferroxidase activity to help the ΔcspE strain detoxify the excess iron. Image was constructed using Biorender.com.

In this study, we report for the first time, the physiological function of previously uncharacterized protein, YciF, in bile stress response of enteric pathogen S. Typhimurium. YciF has ferroxidase activity that can prevent the damage to the cell caused by bile-mediated oxidative stress. The functional characterization of YciF can present a prototype for other homologous proteins of the DUF892 domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and growth conditions.

S. Typhimurium (ATCC 14028s) strain was used for in vivo studies (10). Cultures (Table S1) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C with aeration at 180 rpm. Overnight grown single colony culture was used as pre-inoculum for all experiments. When needed, ampicillin was added at the concentration of 100 μg/mL. pQE60ampR was used to overexpress yciF and its mutant forms.

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction.

Homologous sequences closely related to S. Typhimurium (strain 14028s) YciF (Uniprot ID A0A0F6B221) were identified through UniprotKB database. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal omega program (60). Amino acid residues involved in metal ion coordination in the DUF892 domain were identified based on the YciF crystal structure (PDB ID 4ERU). For analyzing wider taxonomic distribution, YciF sequence from S. Typhimurium (strain 14028s) was submitted to Jpred protein secondary structure prediction web server. Homologs of YciF from different genera were aligned to the input sequence and the results were shown using Jalview software (version 2.11.2.5). Phylogenetic tree was constructed using BLOSUM62 neighbor joining method.

Cloning yciF.

PCR amplification of yciF was done using WT 14028s genomic DNA as template. The strains are listed in Table S2 and the primers used for site directed mutagenesis are listed in Table S3. PCR amplified yciF (with Strep II tag on C-terminal) and pQE60 plasmid (containing an IPTG inducible T5 promoter) were digested with BamHI and EcoRI (New England Biolabs) and purified by gel extraction (MinElute gel extraction kit, Qiagen, Germany). The purified insert was ligated into the cut pQE60 using T4 DNA ligase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 16°C overnight. pyciF construct was transformed into Top10 competent cells. pyciF was purified (GeneJET plasmid miniprep kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lithuania) and confirmed by restriction digestion to visualize the insert release and Sanger sequencing (Aggrigenome, Kerala, India).

Site directed mutagenesis.

Site directed mutagenesis was performed using overlapping primers with desired mutations (Q54A, E113Q, E143D). At total of 50 μL PCR mix was prepared using 100 ng template (pQE60 containing yciF), 250 nM forward and reverse primers, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1X Phusion DNA polymerase buffer, 5% DMSO, and 1 μL Phusion DNA polymerase. The negative control did not have DNA polymerase. Primer extension was done at 72°C for 6 min (18 cycles). 1X Cutsmart buffer and 1 μL of DpnI (New England Biolabs) was added to 25 μL of PCR product and incubated at 37°C for 4 h to remove template DNA, followed by inactivation of DpnI at 80°C for 20 min. DpnI digested product was used to transform Top10 competent cells by heat shock method. Plasmid was isolated from transformed cells and sequenced to confirm the mutation. S. Typhimurium WT and ΔcspE strains were transformed with pQE60 (vector alone), pyciF, and pyciF containing Q54A, E113Q, and E143D mutations by electroporation.

Protein purification.

Proteins were purified as described (61) with following modifications. E. coli BL21(DE3) containing either WT or mutant pyciF (Strep II tagged) was grown to OD600 of 0.5 at 37°C, 180 rpm in 1 L of LB supplemented with 100 μg/mL Ampicillin. The culture was induced with 1 mM IPTG (G biosciences, USA) followed by incubation at 20°C, 180 rpm for 12 h. The cells were centrifuged at 6,000 rpm, 4°C for 15 min. Cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (Buffer A) containing Tris-Cl pH 8, 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT and sonicated. Lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm, 4°C for 45 min. The supernatant was subjected to affinity chromatography using 1 mL buffer equilibrated Strep-Tactin XT 4Flow resin (IBA Lifesciences-GmbH) and flow through was collected. Wash was given using buffer B (Tris-Cl pH 8, 10% glycerol, 200 mM NaCl) and bound protein was eluted using buffer C (Tris-Cl pH 8.5, 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 40 mM Biotin). Protein purity was confirmed on 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel with Coomassie brilliant blue staining and concentration of purified YciF was determined by Bradford assay. Protein was dialyzes (in buffer containing Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl) and concentrated using Amicon ultra-15 centrifugal filter, 10 kDa cutoff (Merck-Millipore, Ireland) and stored at −80°C.

Native PAGE.

Purified proteins and native protein standard (Supelco-Merck) were loaded in 4% to 15% gradient mini protean precast native gel (Bio-Rad, USA). Electrophoresis was performed at 100 V, 4°C in 1X native running buffer. Gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue staining solution.

Size exclusion chromatography.

A total of 4 mg native protein standard was loaded to calibrate the gel filtration column (Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL column, GE Healthcare). Following this, 1 mg of purified protein (YciF, Q54A, E113Q, and E143D) was loaded onto column equilibrated with elution buffer (Tris-Cl pH 8, 5% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl). All the runs were performed at 4°C using an AKTA purifier. Flow rate was maintained at 0.3 mL/min. Fractions were subjected to 12.5% SDS-PAGE.

Thermal shift assay.

Thermal shift assay was performed as per Bio-Rad protocol with following modifications. A total of 10 μg YciF was incubated with 200 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, MgSO4, ZnCl2, and EDTA in a hard-shell PCR 96-well plate (Bio-Rad, USA). Then, 5X Sypro Orange dye (Supelco, Merck, USA) was added and change in fluorescence due to thermal denaturation was measured from 25°C to 95°C in a Bio-Rad CFX connect q-PCR instrument. To investigate thermal stability of WT and mutant proteins, Sypro Orange was added at 5X concentration to 10 μg of YciF, Q54A, E113Q and E143D and thermal denaturation was measured from 25°C to 95°C. Ramp rate was kept 0.5°C/10s. The first derivative of RFU was plotted against the temperature and the peak of first derivative was used to determine melting temperature.

Iron staining.

For 15 min on ice, 20 μM purified proteins and BSA were incubated in absence or presence of 200 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2. The samples were loaded on 8% native gel and electrophoresis was performed at 75V, 4°C for 6 h. Gel was stained with Ferene-S (Sigma-Aldrich, China) solution to detect bound iron (0.75 mM Ferene-S, 2% vol/vol acetic acid, 15 mM thioglycolic acid) in dark for 5 min (62). It was destained and stained again with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Ferroxidase activity.

Ferroxidase activity was determined as described previously (63–65) with following modifications: 10 mM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 stock solution was prepared in 0.1% (vol/vol) HCl; buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 5% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl) was prepared anaerobically; 1 μM protein was added to buffer and ferroxidase reaction was initiated by adding (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 at different final concentrations in a UVMax 96-well plate (SPL life Sciences, Korea) with a final reaction volume of 200 μL. The absorbance was recorded at 310 nm after 600 s or every 30 s until 600 s using Infinite 200-Pro instrument (Tecan, Austria GmbH). For ferrous loss assay, Ferene-S was added at a final concentration of 500 μM after 600 s to the solution containing protein and 200 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 and absorbance was measured at 590 nm.

RNA isolation.

Bacterial cultures were grown to OD600 of 0.3 and then for 90 min in presence or absence of 3% bile. Cells were resuspended in 1 mL TRIzol reagent (Ambion, Invitrogen) and allowed to lyse for 30 min at 1,500 rpm in a shaking drybath (DLAB). Next, 250 μL of chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added and mixed vigorously for 30 s. The sample was allowed to stand for 2 min and centrifuged at 12,000 × g, 4°C, 15 min. The aqueous phase was mixed with 200 μL of chloroform and phase separation was performed again as earlier. Then, 300 μL of aqueous phase was added to 500 μL of 2-propanol (Merck, Germany) and kept overnight at −20°C for RNA precipitation. The RNA was pelleted at 15,000 × g, 4°C, 30 min and washed with 75% ethanol twice. Pellet was kept for drying to remove residual ethanol and dissolved in nuclease-free water. RNA integrity was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel. Concentration was determined using Nano-Drop (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

qRT-PCR.

qRT-PCR was performed as described previously (10) with the following modifications. Genomic DNA was removed from the extracted RNA using DNase I (New England Biolabs) treatment and removal was confirmed by PCR of a reference gene. And, 2.5 μg of DNase I treated RNA was reverse transcribed using random hexamer and RevertAid cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lithuania). q-PCR was performed using 100 ng of cDNA sample, 250 nM gene specific primer, SYBR green master mix (Bio-Rad) in a Bio Rad CFX connect q-PCR instrument. The primers (Sigma-Aldrich, Bangalore) for q-PCR are listed in Table S4. The relative quantities of transcripts were estimated using ΔΔCq method normalized against two reference genes, gmk and gyrB. The WT strain grown in LB was used as control sample.

Intracellular iron estimation.

Intracellular iron was determined as described (66) with the following modifications: 5X working solution was prepared containing 1M L-ascorbic acid (Sigma, USA) in 2 M acetate buffer (pH 4 to 4.5). 0.5 mL of 0.5 M Ferene-S solution was added to 10 mL of 5X working buffer and deionized water was added to a final volume of 50 mL to prepare 1X working solution. The cells were centrifuged (5,000 rpm, 5 min) and washed with 1X PBS, twice. The pellet was resuspended in 1X PBS and O.D. was measured at 600 nm. Cells were sonicated and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Then, 50 μL of supernatant was incubated with 300 μL of 1X working solution for 20 h in dark. Next, 250 μL of sample was taken in a 96-well plate and absorbance was measured at 595 nm using Infinite 200-Pro instrument (Tecan, Austria GmbH). The absorbance value of each sample was normalized to OD at 600 nm.

Bacterial stress assays.

Experiments were done in 5 mL LB. Overnight grown cultures of indicated S. Typhimurium WT and ΔcspE strains were normalized to OD600 of 2, diluted 1:250 in LB and grown to OD600 of 0.2, followed by addition of stress inducing compounds. Bile was added in the beginning to the diluted WT and ΔyciF strains to a final volume of 3%. Cells were grown in 50 mL falcons for 6 h (3 h in H2O2), at 180 rpm, 37°C. A total of 200 μL culture from each growth condition was taken in clear flat bottom 96-well plate and OD600 was measured using Infinite 200-Pro instrument (Tecan, Austria GmbH).

ROS estimation.

ROS estimation was done as described previously (67). S. Typhimurium WT and ΔcspE strains were diluted 1:250 in LB and grown to OD600 of 0.3 and treated with 3% bile for 6 h. Cells were centrifuged and washed with 1X PBS. Cells were incubated with 20 μM 2’,7’-Dichlorofluorescin Diacetate (DCFDA) (Millipore, China) at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were washed twice with 1X PBS and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. A total of 20,000 cells were recorded per condition in a FACS Verse instrument (BD Biosciences, USA). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10). For quantitative estimation of ROS, 200 μL of cell suspension from each condition was taken in 96-well plate and fluorescence was measured at excitation of 485 nm and emission of 535 nm using Infinite 200-Pro instrument (Tecan, Austria GmbH). The values were normalized to OD600.

Bile tolerance assay in the presence of 2,2-bipyridyl.

S. Typhimurium WT and ΔcspE strains were diluted 1:250 in LB with or without 200 μM 2,2-bipyridyl (Sigma-Aldrich, China). Cultures were incubated at 37°C at 180 rpm, grown to OD600 of 0.2, and then treated with bile (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 3% for 6 h. OD600 was measured and cells were plated on LB agar at appropriate dilutions to count CFU. Qualitatively, viability postbile treatment was determined by spotting serial dilutions on LB agar. CFU plates were kept at 37°C while spotting plates were kept at 30°C overnight to prevent overgrowth.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad prism software. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze bacterial growth and ROS estimation with each strain and condition were compared using Sidak’s multiple-comparison test. One way ANOVA was used to analyze q-PCR data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the SEC-MALS facility at the Molecular Biophysics Unit, Indian Institute of Science, and FACS facility, Division of Biological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science. We appreciate the help of Smruti Nayak and Pragya Ahuja with the SEC, and Kshitiza Mohan Dhyani and Sirisha Jagdish with protein purification and Siddharth Jhunjhunwala for Biorender accession.

This work was supported by core grants from IISc and the DBT-IISc program. M.S. was supported by Council of Scientific and Industrial Research fellowship.

We declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Dipankar Nandi, Email: nandi@iisc.ac.in.

Julie A. Maupin-Furlow, University of Florida Department of Microbiology and Cell Science

REFERENCES

- 1.Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, Angulo FJ, Kirk M, O'Brien SJ, Jones TF, Fazil A, Hoekstra RM, International Collaboration on Enteric Disease 'Burden of Illness' Studies . 2010. The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin Infect Dis 50:882–889. doi: 10.1086/650733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hohmann EL. 2001. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Clin Infect Dis 32:263–269. doi: 10.1086/318457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon MA. 2008. Salmonella infections in immunocompromised adults. J Infect 56:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhanoa A, Fatt QK. 2009. Non-typhoidal Salmonella bacteraemia: epidemiology, clinical characteristics and its’ association with severe immunosuppression. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 8:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Biswas S, Paudyal N, Pan H, Li X, Fang W, Yue M. 2019. Antibiotic resistance in Salmonella typhimurium isolates recovered from the food chain through national antimicrobial resistance monitoring system between 1996 and 2016. Front Microbiol 10:985. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernández SB, Cota I, Ducret A, Aussel L, Casadesús J. 2012. Adaptation and preadaptation of Salmonella enterica to bile. PLoS Genet 8:e1002459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Begley M, Gahan CGM, Hill C. 2005. The interaction between bacteria and bile. FEMS Microbiol Rev 29:625–651. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein C, Bernstein H, Payne CM, Beard S, Schneider J. 1999. Bile salt activation of stress response promoters in Escherichia coli. Curr Microbiol 39:68–72. doi: 10.1007/s002849900420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristoffersen SM, Ravnum S, Tourasse NJ, Økstad OA, Kolstø AB, Davies W. 2007. Low concentrations of bile salts induce stress responses and reduce motility in Bacillus cereus ATCC 14570. J Bacteriol 189:5302–5313. doi: 10.1128/JB.00239-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray S, Da Costa R, Das M, Nandi D. 2019. Interplay of cold shock protein E with an uncharacterized protein, YciF, lowers porin expression and enhances bile resistance in Salmonella Typhimurium. J Biol Chem 294:9084–9099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.008209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michaux C, Holmqvist E, Vasicek E, Sharan M, Barquist L, Westermann AJ, Gunn JS, Vogel J. 2017. RNA target profiles direct the discovery of virulence functions for the cold-shock proteins CspC and CspE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:6824–6829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620772114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrews SC. 2010. The Ferritin-like superfamily: evolution of the biological iron storeman from a rubrerythrin-like ancestor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1800:691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrondo MA. 2003. Ferritins, iron uptake and storage from the bacterioferritin viewpoint. EMBO J 22:1959–1968. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Brun NE, Crow A, Murphy MEP, Mauk AG, Moore GR. 2010. Iron core mineralisation in prokaryotic ferritins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1800:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frawley ER, Crouch MLV, Bingham-Ramos LK, Robbins HF, Wang W, Wright GD, Fang FC. 2013. Iron and citrate export by a major facilitator superfamily pump regulates metabolism and stress resistance in Salmonella Typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:12054–12059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218274110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jia H, Song N, Ma Y, Zhang F, Yue Y, Wang W, Li C, Li H, Wang Q, Gu L, Li B. 2022. Salmonella facilitates iron acquisition through UMPylation of ferric uptake regulator. mBio 13:e0020722. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00207-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollack JR, Neilands JB. 1970. Enterobactin, an iron transport compound from Salmonella typhimurium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 38:989–992. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90819-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imlay JA, Linn S. 1988. DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science 240:1302–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.3287616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo Y, Han Z, Chin SM, Linn S. 1994. Three chemically distinct types of oxidants formed by iron-mediated Fenton reactions in the presence of DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:12438–12442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies MJ. 2016. Protein oxidation and peroxidation. Biochem J 473:805–825. doi: 10.1042/BJ20151227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hindupur A, Liu D, Zhao Y, Bellamy HD, White MA, Fox RO. 2006. The crystal structure of the E. coli stress protein YciF. Protein Sci 15:2605–2611. doi: 10.1110/ps.062307706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim Y, Wu R, Jedrzejczak R, Brown RN, Cort JR, Heffron F, Nakayasu ES, Adkins JN, Joachimiak A. 2012. Crystal structure of putative cytoplasmic protein, YciF bacterial stress response protein from Salmonella enterica. PDB. doi: 10.2210/pdb4ERU/pdb. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prouty AM, Brodsky IE, Manos J, Belas R, Falkow S, Gunn JS. 2004. Transcriptional regulation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium genes by bile. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 41:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kröger C, Colgan A, Srikumar S, Händler K, Sivasankaran SK, Hammarlöf DL, Canals R, Grissom JE, Conway T, Hokamp K, Hinton JCD. 2013. An infection-relevant transcriptomic compendium for Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Cell Host Microbe 14:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tosha T, Hasan MR, Theil EC. 2008. The ferritin Fe2 site at the diiron catalytic center controls the reaction with O2 in the rapid mineralization pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:18182–18187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805083105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Theil EC. 2005. Ferritins: dynamic management of biological iron and oxygen chemistry. Acc Chem Res 38:167–175. doi: 10.1021/ar0302336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebrahimi KH, Hagedoorn PL, Hagen WR. 2015. Self-assembly is prerequisite for catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation by catalytically active subunits of ferritin. J Biol Chem 290:26801–26810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.678375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Zang J, Chen H, Zhou K, Zhang T, Lv C, Zhao G. 2019. Thermostability of protein nanocages: the effect of natural extra peptide on the exterior surface. RSC Adv 9:24777–24782. doi: 10.1039/c9ra04785a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu Y, Wang L, Yin S, Zhang B, Jiao Y, Sun Y, Middelberg A, Bi J. 2021. Stability of engineered ferritin nanovaccines investigated by combined molecular simulation and experiments. J Phys Chem B. 125:3830–3842. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c00276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNally JR, Mehlenbacher MR, Luscieti S, Smith GL, Reutovich AA, Maura P, Arosio P, Bou-Abdallah F. 2019. Mutant L-chain ferritins that cause neuroferritinopathy alter ferritin functionality and iron permeability. Metallomics 11:1635–1647. doi: 10.1039/c9mt00154a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pulsipher KW, Villegas JA, Roose BW, Hicks TL, Yoon J, Saven JG, Dmochowski IJ. 2017. Thermophilic ferritin 24mer assembly and nanoparticle encapsulation modulated by interdimer electrostatic repulsion. Biochemistry 56:3596–3606. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hantke K, Nicholson G, Rabsch W, Winkelmann G. 2003. Salmochelins, siderophores of Salmonella enterica and uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains, are recognized by the outer membrane receptor IroN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:3677–3682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737682100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crouch MLV, Castor M, Karlinsey JE, Kalhorn T, Fang FC. 2008. Biosynthesis and IroC-dependent export of the siderophore salmochelin are essential for virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 67:971–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kingsley RA, Reissbrodt R, Rabsch W, Ketley JM, Tsolis RM, Everest P, Dougan G, Bäumler AJ, Roberts M, Williams PH. 1999. Ferrioxamine-mediated iron(III) utilization by Salmonella enterica. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:1610–1618. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.4.1610-1618.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sousa Gerós A, Simmons A, Drakesmith H, Aulicino A, Frost JN. 2020. The battle for iron in enteric infections. Immunology 161:186–199. doi: 10.1111/imm.13236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradley JM, Svistunenko DA, Wilson MT, Hemmings AM, Moore GR, Le Brun NE. 2020. Bacterial iron detoxification at the molecular level. J Biol Chem 295:17602–17623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV120.007746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ray S, Da Costa R, Thakur S, Nandi D. 2020. Salmonella typhimurium encoded cold shock protein e is essential for motility and biofilm formation. Microbiology (Reading) 166:460–473. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prouty AM, Schwesinger WH, Gunn JS. 2002. Biofilm formation and interaction with the surfaces of gallstones by Salmonella spp. Infect Immun 70:2640–2649. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2640-2649.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crawford RW, Rosales-Reyes R, Ramírez-Aguilar MdlL, Chapa-Azuela O, Alpuche-Aranda C, Gunn JS. 2010. Gallstones play a significant role in Salmonella spp. gallbladder colonization and carriage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:4353–4358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000862107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hébrard M, Viala JPM, Méresse S, Barras F, Aussel L. 2009. Redundant hydrogen peroxide scavengers contribute to Salmonella virulence and oxidative stress resistance. J Bacteriol 191:4605–4614. doi: 10.1128/JB.00144-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfaffen S, Bradley JM, Abdulqadir R, Firme MR, Moore GR, Brun NEL, Murphy MEP. 2015. A diatom ferritin optimized for iron oxidation but not iron storage. J Biol Chem 290:28416–28427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.669713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawson DM, Treffry A, Artymiuk PJ, Harrison PM, Yewdall SJ, Luzzago A, Cesareni G, Levi S, Arosio P. 1989. Identification of the ferroxidase centre in ferritin. FEBS Lett 254:207–210. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrews SC. 1998. Iron storage in bacteria. Adv MicrobPhysiol 40:281–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urdaneta V, Casadesús J. 2017. Interactions between bacteria and bile salts in the gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary tracts. Front Med (Lausanne) 4:163. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamner S, McInnerney K, Williamson K, Franklin MJ, Ford TE. 2013. Bile salts affect expression of Escherichia coli O157:H7 genes for virulence and iron acquisition, and promote growth under iron limiting conditions. PLoS One8 8:e74647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu J, Qi L, Hu M, Liu Y, Yu K, Liu Q, Liu X. 2017. Salmonella proteomics under oxidative stress reveals coordinated regulation of antioxidant defense with iron metabolism and bacterial virulence. J Proteomics 157:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu X, Omar M, Abrahante JE, Nagaraja KV, Vidovic S. 2020. Insights into the oxidative stress response of Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis revealed by the next generation sequencing approach. Antioxidants 9:849. doi: 10.3390/antiox9090849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hassett DJ, Schweizer HP, Ohman DE. 1995. Pseudomonas aeruginosa sodA and sodB mutants defective in manganese- and iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase activity demonstrate the importance of the iron-cofactored form in aerobic metabolism. J Bacteriol 177:6330–6337. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6330-6337.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cornelis P, Wei Q, Andrews SC, Vinckx T. 2011. Iron homeostasis and management of oxidative stress response in bacteria. Metallomics 3:540–549. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00022e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Michaels ML, Pham L, Nghiem Y, Cruz C, Miller JH. 1990. MutY, an adenine glycosylase active on G-A mispairs, has homology to endonuclease III. Nucleic Acids Res 18:3841–3845. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.13.3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gralnick J, Downs D. 2001. Protection from superoxide damage associated with an increased level of the YggX protein in Salmonella enterica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:8030–8035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151243198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park S, You X, Imlay JA. 2005. Substantial DNA damage from submicromolar intracellular hydrogen peroxide detected in Hpx- mutants of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:9317–9322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502051102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. 2007. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collin F. 2019. Chemical basis of reactive oxygen species reactivity and involvement in neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci 20:2407. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Acker H, Coenye T. 2017. The role of reactive oxygen species in antibiotic-mediated killing of bacteria. Trends Microbiol 25:456–466. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hong Y, Zeng J, Wang X, Drlica K, Zhao X. 2019. Post-stress bacterial cell death mediated by reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:10064–10071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901730116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Z, Liu Y, Fu J, Zhang B, Cheng S, Wu M, Wang Z, Jiang J, Chang C, Liu X. 2019. Salmonella proteomic profiling during infection distinguishes the intracellular environment of host cells. mSystems 4:e00314-18. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00314-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clark L, Perrett CA, Malt L, Harward C, Humphrey S, Jepson KA, Martinez-Argudo I, Carney LJ, La Ragione RM, Humphrey TJ, Jepson MA. 2011. Differences in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain invasiveness are associated with heterogeneity in SPI-1 gene expression. Microbiology (Reading) 157:2072–2083. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.048496-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karas VO, Westerlaken I, Meyer AS. 2015. The DNA-binding protein from starved cells (Dps) utilizes dual functions to defend cells against multiple stresses. J Bacteriol 197:3206–3215. doi: 10.1128/JB.00475-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidt TG, Skerra A. 2007. The Strep-tag system for one-step purification and high-affinity detection or capturing of proteins. Nat Protoc 2:1528–1535. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chung MCM. 1985. A specific iron stain for iron-binding proteins in polyacrylamide gels: application to transferrin and lactoferrin. Anal Biochem 148:498–502. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bonomi F, Kurtz DM, Cui X. 1996. Ferroxidase activity of recombinant Desulfovibrio vulgaris rubrerythrin. J Biol Inorg Chem 1:67–72. doi: 10.1007/s007750050024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.He D, Hughes S, Vanden-Hehir S, Georgiev A, Altenbach K, Tarrant E, Mackay CL, Waldron KJ, Clarke DJ, Marles-Wright J. 2016. Structural characterization of encapsulated ferritin provides insight into iron storage in bacterial nanocompartments. Elife 5:e18972. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uebe R, Ahrens F, Stang J, Jäger K, Böttger LH, Schmidt C, Matzanke BF, Schüler D. 2019. Bacterioferritin of magnetospirillumgryphiswaldense is a heterotetraeicosameric complex composed of functionally distinct subunits but is not involved in magnetite biomineralization. mBio 10:e02795-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02795-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hedayati M, Abubaker-Sharif B, Khattab M, Razavi A, Mohammed I, Nejad A, Wabler M, Zhou H, Mihalic J, Gruettner C, DeWeese T, Ivkov R. 2018. An optimised spectrophotometric assay for convenient and accurate quantitation of intracellular iron from iron oxide nanoparticles. Int J Hyperthermia 34:373–381. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2017.1354403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dewachter L, Herpels P, Verstraeten N, Fauvart M, Michiels J. 2016. Reactive oxygen species do not contribute to ObgE*-mediated programmed cell death. Sci Rep 6:33723. doi: 10.1038/srep33723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental materials and methods, Tables S1 to S3, and Fig. S1 to S7. Download jb.00059-23-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, pdf)